Abstract

Social media content can spread quickly, particularly that generated by users themselves. This is a problem for businesses as user-generated content (UGC) often portrays brands negatively and, when mishandled, may turn into a crisis. This paper presents a framework for crisis management that incorporates insights from research on social media users’ behaviour. It looks beyond specific platforms and tools, to develop general principles for communicating with social media users. The framework’s relevance is illustrated via a widely publicised case of detrimental UGC. The paper proposes that, today, businesses need to identify relevant social media platforms, to monitor sentiment variances, and to go beyond simplistic metrics with content analysis. They also need to engage with online communities and the new influencers, and to respond quickly in a manner that is congruent with said social media platforms and their users’ expectations. The paper extends the theoretical understanding of crisis management to consider the role of social media as both a cause and a solution to those crises. Moreover, it bridges information management theory and practice, providing practical managerial guidance on how to monitor and respond to social media content, particularly during fast-evolving crises.

Public Interest Statement

This paper highlights the importance of proactive rather than reactive approach to managing crises on social media. It provides insight into how monitoring and engaging in social media conversations benefit organisations in instances of crises.

1. Introduction

Social media have made it possible for one single Internet user to damage an organisation’s reputation with a simple tweet or video upload. Creating and sharing content online is not only increasingly easy, but also seen as a source of consumer empowerment (Christodoulides, Jevons, & Bonhomme, Citation2012). User-generated content (UGC) criticising brands can spread widely and quickly (Kietzmann & Canhoto, Citation2013), achieve viral status and threaten those brands (Vanden Bergh, Lee, Quilliam, & Hove, Citation2011). In turn, the organisation’s response can amplify the virality of the message (Kietzmann & Canhoto, Citation2013) and influence referrals and purchase intentions (Gelbrich & Roschk, Citation2011).

Despite social media’s popularity, organisations still struggle to handle two-way communication with customers, particularly during a crisis. Recent examples include problems faced by Findus in the UK in 2013 following the Horse Meat scandal; by HMV following the firing of 190 staff members; and by J.P. Morgan when they urged the public to tweet their questions using the hashtag #AskJPM. The communication dynamics between businesses and customers have changed, and practical guidance is urgently needed on how firms should react to social media conversations (Blackshaw, Citation2011).

The principles well established in the information management literature do not work well in the new socio-technical context (Sultan, Citation2013). There is empirical research on the behavioural drivers of social media participation and the impact of online conversations on brand perception (e.g. Vanden Bergh et al., Citation2011) as well as guidance on how to mine social media data (e.g. He, Zha, & Li, Citation2013). However, the research addressing the organisation’s response (e.g. Kietzmann & Canhoto, Citation2013; Kietzmann, Hermkens, McCarthy, & Silvestre, Citation2011) tends to be conceptual rather than empirical. Hence, there is a need for managerial guidance and further theoretical understanding of crisis management in the social media age. This paper addresses that gap.

This paper highlights shortcomings of the dominant literature, proposing a nuanced approach to understanding and responding to negative social media conversations. It presents a framework that incorporates the findings from research on social media users’ behaviour and updates the current theoretical understanding of crisis management. The framework is operationalised using a classic, well-known case of social media crisis: when employees of Domino’s Pizza posted a video showing unhygienic food preparation practices.

Domino’s is a pizza delivery company established in the US state of Michigan in 1960, which has since opened operations in more than 70 countries. On 13th April, 2009, two employees filmed and uploaded videos of themselves performing unsanitary and vulgar acts while preparing food in one of the fast food chain’s kitchens. A video entitled “Domino’s Pizzas Special Ingredients” shows footage of one of the employees, Michael Setzer, putting cheese up his nose, smearing nasal mucus on food and passing gas on salami; while the other employee, Kristy Hammonds, can be heard joking and laughing in the background throughout. Other videos entitled “Poopie Dishes”, “Sneeze Sticks” and “Dominos Pizza Buger” show Setzer in vivid detail wiping his behind with a sponge prior to cleaning pizza pans, sneezing on bread and engaging in additional acts of food contamination. Within hours of the news going public, it was a trending topic on various social media channels, influencing organic search results and consumers’ purchase intentions.

This case was chosen because food is the most widely discussed topic on social media (Forsyth, Citation2011), yet receives little attention in the information systems literature (He et al., Citation2013). Moreover, the negative UGC depicted deliberate product contamination; the biggest threat to a food and beverage company’s reputation (Nickson, Citation2000). Yet, it is widely acknowledged that Domino’s not only survived this crisis, but even managed to restore their brand reputation. Using the case of a company that faced its worst-case scenario and survived allows us to explore the long-term effects of a social media crisis.

The paper proceeds as follows. The next section reviews the dominant thinking in the field of crisis management and introduces the research questions. Then, findings from research on social media users and communication are used to develop the research framework. Subsequently, the application of the framework is demonstrated through analysis of the Domino’s case study. The purpose of the empirical study is not to develop generalisable findings about UGC-related crisis, but rather to bring to life what the proposed framework can offer to information management theory and practice. The case shows how consumers’ sentiment evolved over time and explores how communication initiatives influenced the brand’s reputation. The paper concludes with a discussion of the implications for companies’ use of social media in an era where firm-initiated communication is “rapidly losing ground” (Blackshaw, Citation2011, p. 109) to UGC.

2. Detecting and handling crises arising from UGC

It is well established in the crisis management literature (e.g. Ashcroft, Citation1997) that once a crisis occurs, rapid and effective communication is crucial to reduce uncertainty and insecurity of consumers. In the contemporary knowledge economy, crisis management is closely related to reputation risk and, as organisations are subject to higher levels of transparency, their reputation risk increases (Scott & Walsham, Citation2005). The management of reputation risks cannot be realised by one-off efforts or reactive solutions (Scott & Walsham, Citation2005). Rather, organisations need to proactively monitor the market environment (Ritchie, Citation2004), manage information flow (Day, Burnice McKay, Ishman, & Chung, Citation2004) and treat customers as key stakeholders (Elliott, Harris, & Baron, Citation2005).

As perceptions are affirmed over time, altering a negative reputation is more complex than building a new one (Mahon & Mitnick, Citation2010). Hence, it is very important to be able to detect the early warning signs of a crisis (Stephens Balakrishnan, Citation2011). The temporal element gains even more significance in the face of the current media landscape, as the Internet spreads news faster than ever (Vanden Bergh et al., Citation2011). Consequently, our first research question focuses on: How can social media help organisations detect early signs of a negative reputation shift?

There have been cases, such as the Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy crisis that caused about 200 human deaths globally, that escalated more due to ineffective communication than by the crisis itself (Ashcroft, Citation1997). Hence, it is essential that firms communicate in a way that restores confidence in the brand (Stephens Balakrishnan, Citation2011). Communication should be anchored in the historical context and instances that caused the reputation crisis, and take into account how the content relates to the brand’s reputation (Mahon & Mitnick, Citation2010). The response needs to address the negative perceptions of key stakeholders (Stephens Balakrishnan, Citation2011) and the public at large (Tew, Lu, Tolomiczenko, & Gellatly, Citation2008). Organisations should also seek enlarged media exposure, as research (e.g. Wartick, Citation1992) has demonstrated that increased media exposure with a positive tone stands in direct relation to enhanced corporate reputation. Furthermore, as Dijkmans, Kerkhof, and Beukeboom (Citation2015) note, engagement in social media is positively related to corporate reputation, especially among non-users. As such, the second research question is: What is the role of social media channels and users during crisis communication?

2.1. The role of social media in reputation monitoring

Organisations should implement scanning processes alerting them to important trends (Ritchie, Citation2004). Social media is a source of rich market insight (Christiansen, Citation2011) as users often discuss brands in those platforms (Bernoff & Li, Citation2008; Canhoto & Clark, Citation2013). Hence, organisations need to add social media channels to their market scanning efforts (He et al., Citation2013).

The large number and variety of social media platforms, volume of content available (Nunan & Di Domenico, Citation2013) and spreadability of social media content (Jenkins, Ford, & Green, Citation2013) impede the task of monitoring social media. However, Kietzmann et al. (Citation2011) note that users favour particular platforms for specific activities—for instance, users may prefer to share content on YouTube rather than LinkedIn. The preferred platform may also vary by industry and country (Canhoto, Clark, & Fennemore, Citation2013). Therefore, to effectively monitor UGC, firms must first recognise and understand the social media landscape (Kietzmann et al., Citation2011), both the technical aspects such as what type of content may be shared, and the sociological ones such as users preferences or the mechanics of content dispersion.

Proposition 1: Firms need to monitor UGC on the SM platforms that particularly reflect their core activities and their users’ preferences, and that are also relevant for their specific socio-technical ecosystem.

Reputation may vary independently of the firm’s actions and, therefore, it is necessary to monitor how it changes over time (Fombrun, Gardberg, & Sever, Citation2000). The focus on variance, rather than absolute measures, is particularly relevant for the social media context, as characterised by a wealth of information and a poverty of attention (Kietzmann & Canhoto, Citation2013). The temporal perspective enables managers to detect dramatic changes resulting from a social media crisis.

The volume of data available and pressure for timely analysis means that, increasingly, data collection and analysis occurs without human intervention (Nunan & Di Domenico, Citation2013). Specifically, various specialist software products are now available to mine documents, identifying words or phrases that denote sentiments (He et al., Citation2013; Sterne, Citation2010). The software generates a “sentiment score” reflecting the percentage of posts that express a “positive”, “negative” or “neutral” sentiment (Yi & Niblack, Citation2005), referred to as sentiment polarity (Thelwall, Buckley, & Paltoglou, Citation2011), which can be monitored over time.

Proposition 2: Firms need to monitor changes in consumer sentiment.

In addition to considering sentiment polarity and how it changes, it is important to analyse the values of the message (Stephens Balakrishnan, Citation2011). Messages triggering emotional responses to core reputation elements are particularly damaging for brands (Mahon & Mitnick, Citation2010). This is a concern for managers as negative UGC often uses parody, mockery or even offensiveness (Vanden Bergh et al., Citation2011), likely to trigger emotional reactions. Thus, managers need to go beyond measuring sentiment in UGC and also monitor the topics being discussed.

Despite their popularity, automated sentiment analysis tools have limited ability to capture the quality of the argument (Li & Zhan, Citation2011), detect irony (Canhoto & Clark, Citation2013), and cope with linguistic and cultural differences (Nasukawa & Yi, Citation2003). They also struggle with subtle elements such as the use of clauses (Kim & Hovy, Citation2006) or the choice of words and their placement (Davis & O’Flaherty, Citation2012). The analysis of SM data needs to take into account contextual information (Kozinets, Citation2002, Citation2010).

Proposition 3: Firms need to qualitatively analyse UGC, including the context in which it emerged.

2.2. The role of social media in crisis management

A firm failing to communicate during a crisis may be deemed struggling (Stephens Balakrishnan, Citation2011) or not to care about its customers (Kietzmann & Canhoto, Citation2013). The issue of when a firm should intervene in social media conversations is not an exact science (Kietzmann et al., Citation2011) and depends on issues such as spreadability (Jenkins et al., Citation2013), the degree of change in customer sentiment and the reputational elements attacked by the negative UGC, as discussed previously. In terms of how to intervene during a crisis, firms should communicate regularly through a variety of media (see Stephens Balakrishnan, Citation2011).

Some firms have created online communities to engage with consumers (see Gruner, Homburg, & Lukas, Citation2014), though these are ineffective if users are unaware of their existence (Kietzmann et al., Citation2011). To reach customers quickly, firms must use channels where UGC-related conversations are taking place.

Proposition 4: Respond quickly through the channels that social media users are aware of.

In terms of the message itself, firms are advised to focus on symbolic brand components (Stephens Balakrishnan, Citation2011). The response needs to consider the drivers of UGC creation, involvement and consumer-based brand equity (Christodoulides et al., Citation2012). Social media users may have specific expectations about how and when firms should interact with them on a particular platform (Canhoto & Clark, Citation2013). So, it is important that the response is congruent with the functionalities of the social media platform (Kietzmann et al., Citation2011).

Proposition 5: The response needs to be congruent with the brand’s reputation, users’ motivations and the functionalities of the SM platform.

Finally, researchers agree that positive referrals from trusted parties are crucial in changing brand perception during a crisis. Barwise and Meehan (Citation2010) highlight the abundance of options offered by social media for engagement and collaboration, while Kietzmann et al. (Citation2011) suggest that firms engage credible social media influencers in their marketing communication strategies. Others showed the value of online communities for businesses (e.g. Gruner et al., Citation2014). However, little is known about motivations and impact of spontaneously produced UGC in response to an event outside of what could be conceptualised as an online community, as is likely to be the case with negative UGC. Here, we are referring to classical definitions of what constitutes an (online) community from the work of Muniz and O’Guinn (Citation2001), who defined brand communities as bounded “based on a structured set of social relations among admirers of a brand” (p. 142). Such communities can have clear community leaders, opinion leaders and so on, which can be identified by the brands and their opinions monitored.

Proposition 6: Engage influencers outside of the established brand community.

Figure brings together the propositions developed above in a framework that summarises how social media can assist in identifying and handling crisis arising from UGC.

3. Applying the framework

The framework in Figure will be operationalised through a well-known case study, where a crisis developed and was successfully handled on social media. The use of case studies is highly recommended in crisis management to obtain “a deeper understanding of the dynamics and nuances of communicating during a crisis” (Carroll, Citation2009, p. 67). Using a public case study of an organisation that faced a serious crisis and survived has two advantages. First, the public nature of the case helps with familiarity. Second, in this case, the organisation has clearly recovered from the crisis.

The disadvantage of using a case from 2009 is that technology, and social media in particular, has evolved since then. For instance, whereas YouTube was the main platform for sharing video content in 2009, many users now share short clips through Instagram. Hence, the illustration below also considers the impact of technical evolution on specific aspects of the framework, both between 2009 and now, and looking ahead.

Christodoulides et al. (Citation2012) advise that the study of UGC should analyse how social media users attempt to inform and influence others through shared online content. Accordingly, data collected and presented here captures online behaviour and communication before, during and after the crisis. In terms of what data should be used, this study followed Greyser’s (Citation2009) assessment that reputation studies should draw on multiple sources external to the organisation, rather than internal ones. Accordingly, this study mimics the actions of consumers engaging with the brand online, collecting publicly available online data using the search terms “Domino’s Pizza” and “Domino’s”, as well as the Twitter handle “@dominos”; the most mainstream references to the brand on social media (Li, Sun, Peng, & Li, Citation2012). The use of public online materials allows data to be available for collection and analysis over an extended period of time (O’Reilly, Rahinel, Foster, & Patterson, Citation2007), which facilitates future replication studies.

Rather than engaging in sampling, the researchers collated the entire data-set of social media mentions related to the incident. The goal was to produce an immersive and descriptive account (Kozinets, Citation2010) of evolving sentiment among social media users. The online search identified mentions to the incident on blogs and forums, as well as posts on Twitter and Facebook. The resulting data pool consisted of several thousands of entries. The extensive data collection, which will be discussed in the following sections, enabled us to assess the extent of discussion and dissemination of the crisis, and perform quantitative as well as qualitative analysis of sentiment towards the brand, as discussed next.

3.1. Monitoring sentiment

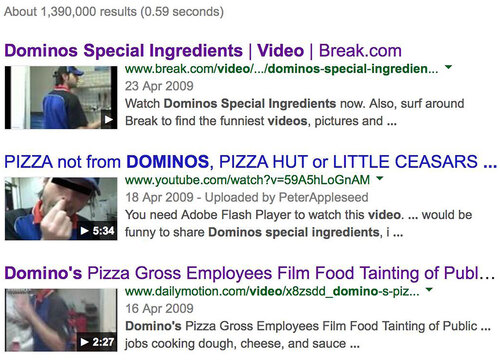

The offending videos appeared on YouTube on 13th April, 2009 and, within two days, had been viewed by over one million users. They have since been removed from YouTube, though the clips and references to them are still widely available on the Internet (Figure ).

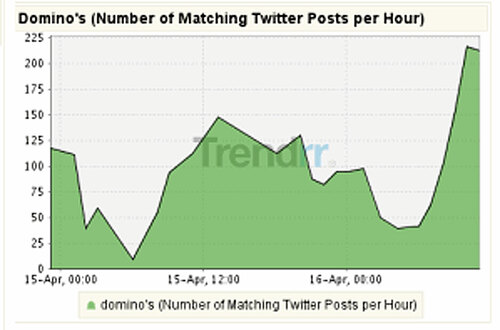

The distribution of these clips generated a “communication crisis” (Coombs, Citation2007), with large numbers of people sharing the videos, and criticising the quality of Domino’s food. On Twitter, for instance, the topic was trending within hours of the news going public (Clifford, Citation2009) (Figure ).

Figure 3. Number of tweets containing “Domino’s” in the days following the incident.

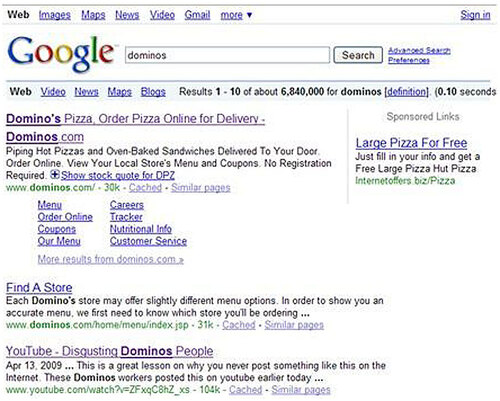

The incident was picked up by a blogs worldwide, including two very popular blogs at the time, www.GoodAsYou.org and The Consumerist. The volume of content associating the videos with the brands was such that three days after the clips were published the top search results for “Domino’s” on Google contained references to the incident (Figure ).

Figure 4. Google search results for “Domino’s” shortly after the incident.

Because content may spread through formal and informal networks, over many platforms, firms should monitor both bottom-up and top-down communications (Jenkins et al., Citation2013). Domino’s was not doing so at the time of the crisis. So, even though the issue was widely discussed on social media, Domino’s did not directly notice it. According to Tim McIntyre, VP of Corporate Communications at Domino’s Pizza, it was the blog www.GoodAsYou.org that had alerted him to the offending videos (Solis, Citation2009). As a result of this crisis, currently Domino’s has a team of social media specialists monitoring and responding to UGC (He et al., Citation2013).

Sentiment analysis tools can measure sentiment towards a brand at a particular point in time, and how it changes over time. In this case, the UGC was analysed with the tool Sysomos; a popular software package used by many advertising and PR companies to measure and manage their clients’ online reputation. The software collects online content, and mines using keywords that denote sentiment. Furthermore, the content is analysed via language processing to produce a sentiment polarity score.

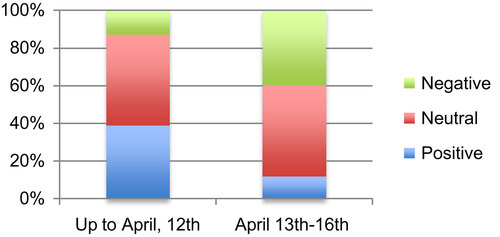

The analysis of social media content gathered for this case shows a dramatic change in consumer sentiment towards Domino’s (Figure ). Up until 12th April (one day before the incident), a relatively small proportion of social media content (13%) referred to Domino’s in a negative manner. Forty-eight per cent of mentions at this time were neutral, while 39% were positive. Once the videos were released, there was a striking shift in consumer sentiment towards Domino’s. Forty per cent of the posts referred to Domino’s Pizza in a negative manner, while only 12% remained positive.

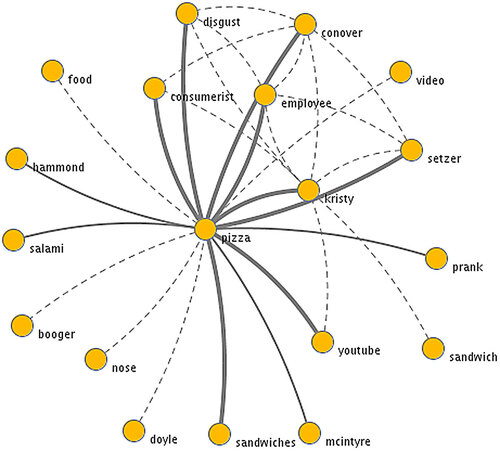

Whilst sentiment scores illustrate general trends, they cannot provide insight into the reasons beyond those scores. For that, it is necessary to qualitatively examine the blog posts, tweets and other social media content. Qualitative, ethnographic methods were used to study the context and the content of the social media data, as described in Kozinets (Citation2010). One type of qualitative analysis widely available to companies is the buzz graph which illustrates key terms appearing in social media mentions related to the topic and illustrates the link between them through the use of dashed lines, thin or thick lines denoting the strength of the association. The buzz graph (Figure ) captures the terms most commonly used in association with the brand once the video was released. These included “prank” and “YouTube”, which would have immediately directed the company to the origins of the change in sentiment. In turn, the terms “disgust” and “employee” indicate a case of tampering with food, particularly when associated with other terms captured by the tool, such as ““nose”, “booger” or “food”. Given that deliberate product contamination is the biggest reputation threat for a food brand (Nickson, Citation2000), this analysis would signal to Domino’s that it was facing a major crisis.

3.2. Reacting to social media users

Unfamiliar with communication on social media, Domino’s management first tried to brush the clips aside, then considered the publication of an official apology on their website, but McIntyre (VP Communications) argued that posting an official apology would draw even more attention to the incident: “We knew what was going to happen. As soon as we posted a statement on our website, we were essentially posting chapter two, and we knew people were [now] going to find chapter one” (Tan, Citation2010).

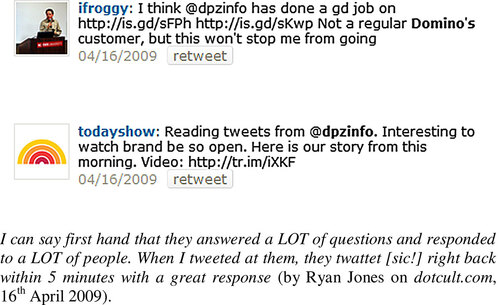

However, the corporation soon realised that they would have to break their silence. McIntyre understood the importance of actively using social media channels for crisis communication: “(M)any of the comments and questions on Twitter were ‘What is Domino’s doing about it?’ […] well, we were doing and saying things, but they weren’t being covered in Twitter” (Clifford, Citation2009). Domino’s established a Twitter account—@dpzinfo—on 15th April and used it to answer numerous questions and comments regarding the incident. As McIntyre explained, Domino’s had learned that “if something happens in this medium, it’s going to automatically jump to the next. So we might as well talk to everybody at the same time” (Sarno & Semuels, Citation2009). Domino’s shifted from a defensive to a proactive approach, having realised that:

(I)n the old days, […] you could handle a situation, put out a fire. […] Now […] if there’s a crisis happening in the social media realm, […] there’s a segment of the population that […] want you to describe how you’re putting out the fire. (Jacques, Citation2009)

Domino’s twitter activity was well received as exemplified by the comments in Figure .

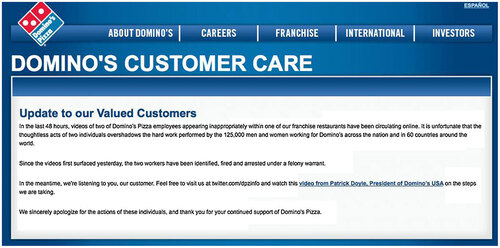

Domino’s also issued an official apology on their website (Figure ), directing visitors to a YouTube video. The company used the same title for the video and the same tags that Hammonds and Setzer had used for the offending clip. This allowed Domino’s to effectively target viewers of the original video, thereby driving traffic to the apology video. In the video, the President of Domino’s USA, Patrick Doyle, sought to reassure customers of the quality, cleanliness and safety of Domino’s Pizza products:

We sincerely apologise for this incident. […] We are taking this incredibly seriously. This was an isolated incident in Conover, North Carolina. The two team members have been dismissed, and there are felony warrants out for their arrests. […] There is nothing more important or sacred to us than our customers trust. […] We have auditors across the country in our stores every day of the week, making sure our stores are as clean as they can possibly be and that we are delivering high-quality food to our customers day in and day out.

Last but not least, McIntyre engaged in an email exchange with the bloggers that had dedicated prominent posts to the incident—GoodAsYou and The Consumerist. For instance, in response to The Consumerist’s post about the incident, McIntyre wrote:

I don’t have the words to say how repulsed I am by this (…) The “challenge” that comes with the freedom of the Internet is that any idiot with a camera and an Internet link can do stuff like this—and ruin the reputation of a brand that’s nearly 50 years old, and the reputation of 125,000 hard-working men and women across the nation and in 60 countries around the world. (Hames, Citation2009)

In turn, The Consumerist replied: “[Our readers] may seem harsh at times, but they can be equally impressive when a corporation appears to be doing the right thing. It’s a relatively popular site, so that may count for something”. And, indeed, readers of The Consumerist identified the franchise where the videos had been filmed. A reader with the username whyerhead commented on The Consumerist’s original post about the incident:

I FOUND IT! Dominos Pizza, Conover NC. How did I find it? I used part of your intel. Googled for lilangel6979, found the myYearbook for that email, looked at the city … There’s a Jack in the box across from this Dominos. Searched yellowpages.com for it, found it at 509 10th St NW, Conover NC. […] I’m not sure how to get in contact with the folks at dominos corporate … but, I’m sure they’re reading our blog by now.

Through engagement of users of The Consumerist’s community, the perpetrators, Setzer and Hammonds, were identified and charged with delivering prohibited foods (Clifford, Citation2009). Hammonds apologised to McIntyre saying:

It was all a prank and me nor Michael expected to have this much attention from the videos that were uploaded! No food was ever sent out to any customer. […] Michael never would do that to any customer, EVER!! I AM SO SORRY!

Most importantly, the quick response, use of relevant social media channels, the clever use of tags and titles for search engine optimisation, the nature of the communications, and the engagement with the blogger community helped save the brand. By April 16th, Domino’s began to recover consumer confidence (Table ). While participants’ positive responses after having viewed the apology video were not quite as high as before they had been aware of the scandal, the results do show an upwards tendency following Doyle’s apology.

Table 1. Responses at three points in time

Domino’s approach also impressed the community that had initially mobilised against the brand:

It clearly wasn’t the fault of Domino’s as a whole, [and] it sends a good image that they came forward and made it clear that they’re just as disgusted as everyone else is. (comment by tlsgirl on yumsugar.com)

It was important for management to respond. Would have been better to speak off the cuff […] but kudos to Domino’s for communicating via the same social channel its wayward employees used. (comment by starbux347 on CNET News)

Financially, too, the company has recovered. Following the incident, Domino’s share price suffered (arrow in Figure ); but just a few months later, it had recovered.

Figure 9. Domino’s share price between 29th December 2008 and 10th March 2014.

4. Discussion

The first research question asked how monitoring UGC could help organisations identify sentiment change. It was argued that organisations needed to monitor a range of relevant social media channels. However, it is not possible to be prescriptive regarding specific platforms as the most popular channels vary by intended function, industry and geography, as discussed previously. Moreover, the technology landscape is constantly evolving (Sultan, Citation2013), requiring organisations to adjust their monitoring focus. Also, monitoring sentiment requires the analysis of content over various platforms, which presents technical challenges. Specifically, while some platforms are open, others, like individual Facebook accounts, are closed, meaning that it is difficult to automatically extract data. More challenging than the technology, however, is the changing relationship between humans and technology (Martini, Massa, & Testa, Citation2013) and, with it, the changing communication dynamics. For instance, consumer conversations occur in channels not traditionally associated with corporate communications. Moreover, users may expect conversations held in such closed platforms to be private, and oppose their messages being mined.

In terms of identifying sentiment polarity, there are semantic challenges hindering automated analysis (e.g. colloquial language, abbreviations and emoticons), as well as those associated with irony and sarcasm (Canhoto & Padmanabhan, Citation2015; Vanden Bergh et al., Citation2011). Likewise, while much content is shared in text format, it is increasingly common for users to publish images (He et al., Citation2013), which are difficult to monitor automatically. As exemplified with the Domino’s case study, complementing sentiment measurement with analysis of the topics discussed and the context surrounding the publication of the content helps overcome those limitations. For instance, the themes identified in the buzz graph would not only direct the management’s attention to YouTube, but also give an idea of the video’s topic and the source of customer disgust.

In summary, if the Internet has emerged as a platform for electronic word of mouth with consumers now basing perceptions and decisions on the opinions of others that they may never have met, and whose reputation is determined by factors not yet thoroughly understood (Marwick, Citation2013), it is also true that technology allows firms to detect those changes and their causes.

The second research question asked how social media might assist with crisis management. Domino’s initially attempted to control the situation, and its initial response to customers’ concerns was more detrimental to the company’s reputation than helpful (Clifford, Citation2009). However, at the time of the crisis (April 2009), sentiment analysis was not widely adopted, and only a handful of companies had teams in place to monitor social media conversations. Today, the role of social media in company reputation management in general, and crisis communication in particular, is more widely acknowledged (Dijkmans et al., Citation2015; Jones, Temperley, & Lima, Citation2009).

Analysis of cases of such social media crisis confirms the need for information management methods and techniques that differ from PR activities in the broadcast media world (Jenkins et al., Citation2013). Our case study data confirms Mahon and Mitnick’s (Citation2010) call for an audience-focused approach when communicating during a crisis and begins to unpack this approach. Specifically, the Domino’s case shows that an audience-focused approach requires detailed knowledge, about where the conversation is taking place, and identifying the key themes and language used, and who the audience is.

This study highlighted the role of bottom-up influencers in amplifying UGC reach. Detecting sentiment changes towards a brand requires firms to identify the relevant influencers. While the concept of “influencers” is not new to marketing, social media led to the emergence of a new class of users with heightened power to shape brand perception in the market, different from those with influence in the offline environment (Kim, Choi, Qualls, & Han, Citation2010). In this particular case, the two blogs mentioned had not previously captured the company’s attention. They were a new type of influencer, and it is argued that Domino’s underestimated the influencing power of such blogs on their customers. The fact that such influencers can change rapidly requires nuanced and adaptable methods of interpretation, such as those afforded by qualitative approaches.

This paper presents and applies a framework that updates the conceptual understanding of crisis management as a form of reputation risk management in the contemporary knowledge economy (Scott & Walsham, Citation2005), through uniting classical crisis management literature and recent social media research. The paper illustrated the application of the framework in practice via the social media crisis faced by Domino’s. Unlike previous research on social media conversations (e.g. He et al., Citation2013), the choice of social media platforms for analysis was not dictated by the researchers. Instead, it followed the conversations, therefore revealing where social media discussions actually occur, and how they spread over more than one platform.

The first insight derived from this paper concerns the power of social media as a source of information and communication among, about and with individuals. Domino’s initially underestimated the power, reach and speed of social media conversations. By ignoring online discussions, management allowed the crisis to grow. Conversely, when they used the same channels through which the crisis had spread, it caught consumers’ attention. One way of energising fans’ and followers’ interest in a brand is by posting video clips on social networking sites like YouTube. Video clips may be shared between networks of fans and friends of fans, leading to large number of views. Furthermore, viewers can comment on the clips, and organisations can capture and analyse these comments with social media monitoring tools. What we can understand is the desire for some very active consumers to act as co-creators with brands, conscious of their social media profile (measured by tools such as Klout scores), and being recognised by brands as part of the meaning-making involved in corporate identity. With a focus on producing what Jenkins et al. (Citation2013) referred to as “spreadable” messages, these consumers or community members increase their social media presence.

The second insight concerns the content of the communications. As previously discussed, analysis of buzz data reveals specific issues damaging a company’s reputation. This insight can be used to tailor a company’s messages and improve the effectiveness of its crisis communication. By communicating with those spreading negative messages as “insiders” in the crisis rather than external threats, organisations can turn a negative relationship positive.

The third insight concerns the role of social media users themselves in crisis recovery. In the case of Domino’s, social media users accepted and amplified the company’s apologies. They empathised with the company’s problem and set out to identify and shame the employees who had caused the crisis. Thus, UGC should not be seen as a matter of a firm’s communications versus consumers’ conversations, but rather as ongoing dialogue about the brand’s actions, with all the customer insight and the engagement opportunities that this offers. UGC also has the added benefit of higher credibility than organisation-generated messages (Blackshaw, Citation2011). Influencers can help in recovery efforts.

Additionally, our study highlights a number of managerial implications. Firstly, companies’ reputations are subject to the content of online conversations about their products and services. Management can influence conversations by taking the participants’ concerns seriously and responding convincingly. Secondly, in order to appropriately respond to people’s concerns and criticisms, it is necessary to examine in detail the content of online conversations. Thirdly, managers should use social media networks where bad sentiment has occurred, to disseminate their response to the UGC. In doing so, they should avoid blaming employees or users for negative sentiment; rather, they should include a call to action, which treats consumers as allies in co-creating a solution.

Like any new framework, however, this one needs refinement. Application to a variety of research settings will provide evidence of its generalisability, while confirming its key contributions and clarifying its limitations.

One limitation arises from the specific case analysed. It may be argued that the nature of the videos posted by Domino’s employees was so outrageous (tampering with food) that they caused an extreme reaction unlikely to be faced by others and, therefore, that the lessons from this case have limited relevance for other situations. While food hygiene may be a particularly sensitive topic, the lessons regarding the mechanics by which the crisis spread and was later contained are applicable and relevant regardless of the scale of the crisis.

Another limitation, relates to the type of crisis considered. A crisis may arise because of spill-over effects from issues with a competitor or about the industry in general, as it happened with the horse meat scandal in the UK. Further studies should attempt to conceptualise the approach to crisis management in the case of spill-over effects. Moreover, as the concept of organisational reputation reflects the organisation’s standing among its counterparts (Deephouse & Carter, Citation2005), in addition to the temporal perspective, organisations should develop regular comparisons with other companies in the industry (Fombrun et al., Citation2000; He et al., Citation2013).

A further issue arises from the use of Sysomos for data analysis. As with many other software packages (see Canhoto & Padmanabhan, Citation2015), Sysomos does not reveal the algorithm that informs the analysis of online data. Therefore, researchers cannot assess how the analysis was performed. Further research could model the same social media data-set through alternative software packages and, possibly, manually. While time-consuming, such research would help to identify discrepancies between the various platforms and, eventually, biases.

This paper has repeatedly noted the role of influencers in amplifying and reversing the crisis. It was noted that social media influencers are not necessarily the same as those with influence in the offline environment, and that the factors affecting the reputation of this new breed of influencers are not yet fully understood. Further research should investigate how and why particular individuals and organisations emerge as influencers in the social media environment.

UGC is a growing phenomenon, which will be further amplified by the continuous popularisation of technology and software that enables the production and sharing of content by anyone with an Internet connection. There is an urgent need for the advancement of guidance to support practitioners increasingly requiring information about ongoing online conversations about their brands. This paper contributes to that discussion, highlighting the value of engaging in a combination of activities to measure sentiment and the impact of social media conversations on corporate reputation.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ana Isabel Canhoto

The activities of the authors centre on both research and practice. Their research activity focuses on the various forms of relationships between brands and consumers and social media. This collaboration merges the academic and the practical aspects of managing social media crises.

Ana Isabel Canhoto researches, writes and advises organisations on how to identify and manage difficult customers, and terminate bad commercial relationships.

Dirk vom Lehn

Dirk vom Lehn’s research is concerned with social interaction and the experience of public places, such as museums and street markets.

Finola Kerrigan

Finola Kerrigan researches a range of issues in marketing, with specific interest in marketing and consumption of arts and culture, branding and social media.

Cagri Yalkin

Cagri Yalkin researches consumer socialisation, online and offline consumer resistance, and the export and consumption of soap operas.

Marc Braun

Marc Braun is Brand Services Manager at GlossyBox.

Nicola Steinmetz

Nicola Steinmetz works at Nestle Germany in Frankfurt.

References

- Ashcroft, L. S. (1997). Crisis management—Public relations. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 12, 325–332.10.1108/02683949710183522

- Barwise, P., & Meehan, S. (2010). The one thing you must get right when building a brand. Harvard Business Review, 88, 80–84.

- Bernoff, J., & Li, C. (2008). Harnessing the power of the oh-so-social web. MIT Sloan Review, 49, 35–42.

- Blackshaw, P. (2011). User-generated content in context. Journal of Advertising Research, 51, 108–111.

- Canhoto, A. I., & Clark, M. (2013). Customer service 140 characters at a time: The users’ perspective. Journal of Marketing Management, 29, 522–544. doi:10.1080/0267257X.2013.777355

- Canhoto, A. I., Clark, M., & Fennemore, P. (2013). Emerging segmentation practices in the age of the social customer. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 21, 413–428.10.1080/0965254X.2013.801609

- Canhoto, A. I., & Padmanabhan, Y. (2015). “We (don’t) know how you feel”—A comparative study of automated vs. manual analysis of social media conversations. Journal of Marketing Management, 31, 1141–1157.10.1080/0267257X.2015.1047466

- Carroll, C. (2009). Defying a reputational crisis—Cadbury’s salmonella scare: Why are customers willing to forgive and forget? Corporate Reputation Review, 12, 64–82.10.1057/crr.2008.34

- Christiansen, L. (2011). Personal privacy and Internet marketing: An impossible conflict or a marriage made in heaven? Business Horizons, 54, 509–514.10.1016/j.bushor.2011.06.002

- Christodoulides, G., Jevons, C., & Bonhomme, J. (2012). Memo to marketers: Quantitative evidence for change: How user-generated content really affects brands. Journal of Advertising Research, 52, 53–64.10.2501/JAR-52-1-053-064

- Clifford, S. (2009, April 14). A video prank at Domino’s damages its brand. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/16/business/media/16dominos.html?_r=0

- Coombs, W. T. (2007). Protecting organization reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corporate Reputation Review, 10, 163–176.10.1057/palgrave.crr.1550049

- Davis, J. J., & O’Flaherty, S. (2012). Assessing the accuracy of automated Twitter sentiment coding. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 16, 35–50.

- Day, B., Burnice McKay, R., Ishman, M., & Chung, E. (2004). It will happen again. Management Decision, 42, 822–836.10.1108/00251740410550907

- Deephouse, D. L., & Carter, S. M. (2005). An examination of differences between organizational legitimacy and organizational reputation. Journal of Management Studies, 42, 3–23.

- Dijkmans, C., Kerkhof, P., & Beukeboom, C. J. (2015). A stage to engage: Social media use and corporate reputation. Tourism Management, 47, 58–67. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2014.09.005

- Elliott, D., Harris, K., & Baron, S. (2005). Crisis management and services marketing. Journal of Services Marketing, 19, 336–345.

- Fombrun, C. J., Gardberg, N. A., & Sever, J. M. (2000). The reputation quotientsm: A multi-stakeholder measure of corporate reputation. Journal of Brand Management, 7, 241–255.10.1057/bm.2000.10

- Forsyth, J. (2011). Coffee—UK (p. 169). London: Mintel.

- Gelbrich, K., & Roschk, H. (2011). A meta-analysis of organizational complaint handling and customer responses. Journal of Service Research, 14, 24–43.10.1177/1094670510387914

- Greyser, S. A. (2009). Corporate brand reputation and brand crisis management. Management Decision, 47, 590–602.

- Gruner, R. L., Homburg, C., & Lukas, B. A. (2014). Firm-hosted online brand communities and new product success. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 42, 29–48.10.1007/s11747-013-0334-9

- Hames, M. (2009). What will Domino’s do? Retrieved from http://sharemarketing.wordpress.com/2009/04/14/what-will-dominos-do/

- He, W., Zha, S., & Li, L. (2013). Social media competitive analysis and text mining: A case study in the pizza industry. International Journal of Information Management, 33, 464–472.10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2013.01.001

- Jacques, A. (2009). Domino’s delivers during crisis: The company’s step-by-step response after a vulgar video goes viral. Retrieved from http://www.prsa.org/Intelligence/TheStrategist/Articles/view/8226/102/Domino_s_delivers_during_crisis_The_company_s_step-.UzHWe9yG7fM

- Jenkins, H., Ford, S., & Green, J. (2013). Spreadable media—Creating value and meaning in a networked culture. New York: New York University Press.

- Jones, B., Temperley, J., & Lima, A. (2009). Corporate reputation in the era of Web 2.0: The case of Primark. Journal of Marketing Management, 25, 927–939.10.1362/026725709X479309

- Kietzmann, J. H., & Canhoto, A. I. (2013). Bitter–sweet! Understanding and managing electronic word of mouth. Journal of Public Affairs, 13, 149–159. doi:10.1002/pa.1470

- Kietzmann, J. H., Hermkens, K., McCarthy, I. P., & Silvestre, B. S. (2011). Social media? Get serious! Understanding the functional building blocks of social media. Business Horizons, 54, 241–251.10.1016/j.bushor.2011.01.005

- Kim, J. W., Choi, J., Qualls, W., & Han, K. (2010). It takes a marketplace community to raise brand commitment: The role of online communities. Journal of Marketing Management, 24, 409–431.

- Kim, S.-M., & Hovy, E. (2006, July). Automatic identification of pro and con reasons in online reviews. Paper presented at the COLING/ACL, Sydney.

- Kozinets, R. V. (2002). The field behind the screen: Using netnography for marketing research in online communities. Journal of Marketing Research, 39, 61–72.10.1509/jmkr.39.1.61.18935

- Kozinets, R. V. (2010). Netnography: Doing ethnographic research online. London: Sage.

- Lardinois, F. (2009). Domino’s: How one YouTube video can ruin a brand. Retrieved from http://readwrite.com/2009/04/16/dominos_youtube_video-awesm=~ozqkffks819yQ6

- Li, J., & Zhan, L. (2011). Online persuasion: How the written word drives WOM—Evidence from consumer-generated product reviews. Journal of Advertising Research, 51, 239–257.10.2501/JAR-51-1-239-257

- Li, L., Sun, T., Peng, W., & Li, T. (2012, February 21). Measuring engagement effectiveness in social media. Paper presented at the SPIE 8302, Imaging and Printing in a Web 2.0 World III, Burlingame, CA.

- Mahon, J. F., & Mitnick, B. M. (2010). Reputation shifting. Journal of Public Affairs, 10, 280–299.10.1002/pa.v10.4

- Martini, A., Massa, S., & Testa, S. (2013). The firm, the platform and the customer: A “double mangle” interpretation of social media for innovation. Information and Organization, 23, 198–213.10.1016/j.infoandorg.2013.07.001

- Marwick, A. (2013). Status update: Celebrity, publicity, and branding in the social media age. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Muniz, A. M. J., & O’Guinn, T. C. (2001). Brand community. Journal of Consumer Research, 27, 412–432.10.1086/319618

- Nasukawa, T., & Yi, J. (2003). Sentiment analysis: Capturing favorability using natural language processing. Paper presented at the 2nd International Conference on Knowledge Capture, Sanibel, FL.

- Nickson, S. (2000). Protecting your good name. Risk Management, 47, 9.

- Nunan, D., & Di Domenico, M. (2013). Market research and the ethics of big data. International Journal of Market Research, 55, 505–520.10.2501/IJMR-2013-015

- O’Reilly, N., Rahinel, R., Foster, M., & Patterson, M. (2007). Connecting in megaclasses: The netnographic advantage. Journal of Marketing Education, 29, 69–84.10.1177/0273475307299583

- Ritchie, B. W. (2004). Chaos, crises and disasters: A strategic approach to crisis management in the tourism industry. Tourism Management, 25, 669–683.10.1016/j.tourman.2003.09.004

- Sarno, D., & Semuels, A. (2009, April 20). Ignore the Twittersphere? Major brands learn that they had better respond – and quick. LA Times. Retrieved from http://articles.latimes.com/2009/apr/20/business/fi-twitter20

- Scott, S. V., & Walsham, G. (2005). Reconceptualizing and managing reputation risk in the knowledge economy: Toward reputable action. Organization Science, 16, 308–322.10.1287/orsc.1050.0127

- Sietsema, C. (2009). Real-time reputation management: Assessing the Domino’s debacle. Retrieved from http://edison.offmadisonave.com/blog/2009/04/17/real-time-reputation-management-assessing-the-dominos-debacle

- Solis, B. (2009). The Domino’s effect. Retrieved from http://bub.blicio.us/the-dominos-effect/

- Stephens Balakrishnan, M. (2011). Protecting from brand burn during times of crisis. Management Research Review, 34, 1309–1334.10.1108/01409171111186423

- Sterne, J. (2010). Social media analytics: Effective tools for building, interpreting, and using metrics. London: Wiley.

- Sultan, N. (2013). Knowledge management in the age of cloud computing and Web 2.0: Experiencing the power of disruptive innovations. International Journal of Information Management, 33, 160–165.10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2012.08.006

- Tan, R. v. (2010). A crisis management plan is critical for quick serves. QSR Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.qsrmagazine.com/food-safety/brand-we-have-problem?page=2µsite=6004118

- Tew, P. J., Lu, Z., Tolomiczenko, G., & Gellatly, J. (2008). SARS: Lessons in strategic planning for hoteliers and destination marketers. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 20, 332–346.

- Thelwall, M., Buckley, K., & Paltoglou, G. (2011). Sentiment in Twitter events. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62, 406–418.10.1002/asi.21462

- Vanden Bergh, B. G., Lee, M., Quilliam, E. T., & Hove, T. (2011). The multidimensional nature and brand impact of user-generated ad parodies in social media. International Journal of Advertising, 30, 103–131.10.2501/IJA-30-1-103-131

- Wartick, S. L. (1992). The relationship between intense media exposure and change in corporate reputation. Business and Society, 31, 33–49.10.1177/000765039203100104

- Yi, J., & Niblack, W. (2005, April). Sentiment mining in WebFountain. Paper presented at the 21st International Conference on Data Engineering, Tokyo.