Abstract

The primary aims of this research are to test (1) if the servant leadership style of managers reduces the turnover intention of employees directly and indirectly through psychological safety and (2) if regulatory focus of employees moderates the relationship between servant leadership and psychological safety. This research answers the call by the researchers to analyse servant leadership as a stand-alone style. This study has been carried out among the schoolteachers working in private and public schools in Pakistan, a developing country in Asia. A questionnaire-based survey was conducted, and responses were collected from 255 teachers. A co-variance-based structural equation modelling approach was used to analyse the data. The salient findings are as follows: (1) servant leadership has a negative relationship with turnover intention, (2) psychological safety mediates the relationship between servant leadership and psychological safety, and (3) regulatory focus moderates the relationship between servant leadership and psychological safety. The findings are significant in strengthening the literature on servant leadership. Furthermore, theoretical and practical implications have been discussed.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The major problem for organisations these days is retaining the best employees. The cost associated with the hiring and recruiting of employees is very high. To curb this problem, leadership plays an important role. The behaviour of leadership affects the overall performance of employees. Majority of the employees leave their supervisors, not their jobs. Therefore, it is important that leadership shows positive attitude towards employees.

1. Introduction

All great principals have many similarities of unique nature, irrespective of the changing aspects and size of the educational institutes (Lindahl & Folkesson, Citation2012; Whitaker, Citation2009). For instance, if the college is symbolised as an apple, then its principal’s worth is no less than the apple’s heart. As suggested by Whitaker (Citation2009) that whatever takes place in a college, it is the principal who filters everything to show good to all. The principal has a substantial influence on the environment of a college, which has remarkable effects on students’ attainment and staff’s holding (Collie, Shapka, & Perry, Citation2011; Lindahl, Citation2010).

The past studies have shown two distinct leadership styles, servant and transformational leadership, in the educational environment for so many years particular focus is paid on the unique method of producing people-oriented leadership (Greenleaf, Citation2002; Gregory Stone, Russell, & Patterson, Citation2004). In a study conducted on college and organisational leadership, Stone et al. (Citation2004) contended that both styles are mutually vibrant and active. The study proposes that the principals’ influence on students is secondary in comparison to teachers’ impact; recognising dynamic leadership style is considered as vital. .

In his early work on the servant leadership theory, Robert Greenleaf in 1977 propagated servant leadership theory, a leadership style that concentrates to serve, and to serve first. As Greenleaf describes it in his book of 2002 edition, Servant Leadership, the Style: “… begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve, to serve first. The conscious choice brings one to aspire to lead. That person is sharply different from one who is a leader first, perhaps because of the need to assuage an unusual power drive or to acquire material possessions” (p. 27).

Many studies have been done to investigate the diverse features of servant leadership in occupational and specifically in educational settings (Russell & Stone, Citation2002; Shaw & Newton, Citation2014; Spears, Citation2004). Outcomes demonstrate a substantial positive influence of principals who go through servant leadership on favourable college climate and teachers’ trust in leadership (Black, Citation2010).

More research is needed, particularly on servant leadership for at least two reasons: First, the previous literature on leadership styles that have received more attention in the educational settings consists mainly of transformational leadership. However, little is known about servant leadership in educational settings. Therefore, limited evidence found about the processes by which servant leadership affects the workplace outcomes. Second, the findings of a most recently published meta-analytic study of Hoch, Bommer, Dulebohn, and Wu (Citation2016) showed that servant leadership explained more variance in job attitudes and behaviours than other leadership types. Therefore, Hoch et al. (Citation2016) emphasised the need for more research on servant leadership “as a stand-alone leadership approach that is capable of helping leadership researchers and practitioners better explain a broad range of outcomes” (p. 2).

This study aimed to make threefold contributions to servant leadership and psychological safety literature. First, in a handful of studies on servant leadership and employees’ turnover intention, the majority of investigations have largely focused on only direct effect of servant leadership on employees’ turnover intention, and “little is known empirically about the underlying psychological processes that are activated to enhance individual performance at work” (Chiniara & Bentein, Citation2016, p. 1). An investigation of such underlying psychological processes is necessary to understand how servant leadership influences the employee’s turnover intention. To address this research gap, this study incorporates social exchange theory (Emerson, John, Harold, & Blau, Citation1976) to investigate psychological safety, referring to one’s belief that workplace is safe to take interpersonal risks, speak up the ideas, share opinions, and act independently on crucial decisions (Edmondson, Citation1999; Edmondson & Lei, Citation2014), as the mediator of this relationship. This study argues that supervisors’ servant leadership first develops the psychological safety of teachers, which in turn negatively influences their turnover intention.

Second, it is believed that the leader–follower relationship is a complex phenomenon that can be influenced by many individual and contextual factors (Northouse, Citation2017). Keeping in view the previous argument, we proposed that the direct and mediating effects of servant leadership on turnover intention can also be affected by dispositional factors, for example, personality and individual’s motive (Donia, Raja, Panaccio, & Wang, Citation2016; Liden, Wayne, Liao, & Meuser, Citation2014). Building upon this argument, this study investigates teachers’ regulatory focus as the moderator of the indirect effect of psychological safety between servant leadership and turnover intention relationship. Regulatory focus refers to the individual self-motivation to achieve goals and perform duties. According to Higgins (Citation1998); Higgins, Shah, and Friedman (Citation1997), regulatory focus refers to the people desire to gain pleasure and efforts to avoid pain. It further elaborates that there are two focus types, promotion focus (look for opportunities and pleasure) and prevention focus (perform duties and avoid pain). In doing so, this study addresses the research call of not only Chiniara and Bentein (Citation2016) to investigate the mediators (psychological safety) of servant leadership but also Liden et al. (Citation2014) to examine the dispositional factors (regulatory focus) that influence servant leadership and follower outcomes relationship, that is, turnover intention. Also, this study also addresses the research call of Edmondson and Lei (Citation2014) to examine the boundary conditions of psychological safety, under which conditions the leader behaviour influences psychological safety.

Finally, insufficient research has been done on the moderated mediation analysis in the relationship between servant leadership and follower outcomes (Arain, Citation2017; Newman, Schwarz, Cooper, & Sendjaya, Citation2017). This, therefore, raises a methodological gap in the servant leadership literature. Thus, by investigating the moderated (i.e., by teacher’s regulatory focus) mediating effect of psychological safety between servant leadership and turnover intention relationship in a developing country like Pakistan by using co-variance-based structural equation modelling (CB-SEM) approach, the current study broadens the horizon of the existing servant leadership and psychological safety literature and answers the gap in the literature.

2. Theoretical framework and hypotheses development

As discussed in Section 1, despite early intuitive insights on ethical implications of servant leadership in the workplace, little attention has been given to servant leadership by organisational scholars. It was only in the last decade when a series of public corporate scandals (e.g., Tyco, WorldCom, and Enron, which were attributed to unethical senior leadership in organisations) underscored the importance of studying ethical/moral-values-based leadership types, such as servant leadership (Hoch et al., Citation2016). In the last decade, researchers came up with several measures of various characteristics of servant leadership (Barbuto & Wheeler, Citation2006; Liden, Wayne, Zhao, & Henderson, Citation2008; van Dierendonck & Nuijten, Citation2011). However, Liden et al. (Citation2008), measure of the seven characteristics of servant leadership (i.e., empowering supervisees, creating value for community, having conceptual skills, putting supervisees first, helping supervisees grow and succeed, behaving ethically, and emotional healing) has been the most popular measure of servant leadership (Chiniara & Bentein, Citation2016). However, recently, Liden et al.’s (Citation2015) call for validation of the short version of SL-28 stresses the need to validate the SL-7 version in a different context and with different organisational settings. Therefore, in this study Liden et al.’s (Citation2015) short version servant leadership scale has been used to investigate how principals’ servant leadership influences teachers’ turnover intention.

2.1. Servant leadership and turnover intention

In the current decade, turnover intention as a leading challenge for fortune 500 CEOs requires more examination to understand why people leave organisations (SHRM, Citation2016). Turnover intention is to refer to the individual’s approximation of the chance of quitting his job shortly (Porter, Steers, Mowday, & Boulian, Citation1974).

Many studies have determined the behavioural objectives of employees (such as their intention to search, intention to leave, or actual turnover) to know about employee turnover because the previous literature has shown that such type of turnover is dificult to be predicated rather than those determined by organisational variables (Akhtar, Salleh, Ghafar, Khurro, & Mehmood, Citation2018; Griffeth, Hom, & Gaertner, Citation2000; Steel & Ovalle, Citation1984). Furthermore, extensive literature review and meta-analysis conducted on employee’s turnover reveal that intention to leave is dependable components which are to be included in the turnover process model as indicated in the studies of Cotton and Tuttle (Citation1986). Therefore, based on the arguments developed above, this study evaluates employee intention to leave as a dependent variable with servant leadership, psychological safety and employee regulatory focus persuading it (intention to leave). Based on the intensive literature reviews and meta-analysis on intention to leave theory (Griffeth et al., Citation2000), we have informed that the employee’s choice of leaving a specific organisation is commenced by job dissatisfaction. In turn, this disappointment with the job convinces the employee to seek a new job, accepting offers from new organisations and at last quitting the organisation. The organisational displeasure process might cause the employee to become dissatisfied with his job (Miskel, Fevurly, & Stewart, Citation1979), further organisational policies (Kossek & Ozeki, Citation1998), leadership style (Fuller, Morrison, Jones, Bridger, & Brown, Citation1999), or job characteristics (Loher, Noe, Moeller, & Fitzgerald, Citation1985). Past studies (Hunter et al., Citation2013; Jaramillo, Grisaffe, Chonko, & Roberts, Citation2009b) specify that servant leadership style in certain conditions is a critical factor in inducing employee intention to leave. Based on the argument develop earlier that leadership style influences the employees job satisfaction and in turn, the level of job satisfaction influence employee turnover intention (Ahmed, Khuwaja, Brohi, Othman, & Bin, Citation2018; Cerit, Citation2009; Macintosh & Doherty, Citation2010; Shah, Ali, Dahri, Brohi, & Maher, Citation2018), as this relationship is already tested in earlier studies where leadership was positively related with job satisfaction which is an antecedent to employees turnover intention. In this study, the researchers developed the argument on previous studies and suggested that servant leadership induces positive behaviours among employees which affect employees’ negative behaviour such as leaving the organisation. Thus, we suggest that the principals servant leadership behavious decreases teachers’ turnover intention.

Therefore, the authors suggest the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Principals’ servant leadership style is negatively associated with teachers’ turnover intention.

Previous studies on the relationship of servant leadership and turnover intention have found that servant leadership is negatively related with employees’ turnover intention (Deconinck & Deconinck, Citation2017; Hunter et al., Citation2013; Kashyap & Rangnekar, Citation2016; Rodriguez, Citation2016). However, less is known about how this relationship works, whether this is a direct relationship or indirect relationship. If it is an indirect relationship, then what are the intervening psychological processes through which servant leadership leads to decreased turnover intention? Answering the research question, this study investigates psychological safety (Edmondson, Citation1999; Edmondson & Lei, Citation2014) as the intervening psychological mechanism through which servant leadership influences turnover intention.

2.2. Servant leadership and psychological safety

Psychological safety is explained as one’s belief about the workplace that it is safe to take the interpersonal risk, speak up the ideas, share opinions, and act independently on crucial decisions (Edmondson, Citation1999; Edmondson & Lei, Citation2014). Schein and Bennis (Citation1965) introduced psychological safety for the first time in the context of organisational sciences more than 50 years ago, but it is only in the later years that empirical studies have thrived. The previous research on psychological safety has generally confirmed that it allows employees “to feel safe at work to grow, learn, contribute, and perform effectively in a rapidly changing world” (Edmondson & Lei, Citation2014). Subsequently, by understanding the nature of psychological safety concept, Kahn (Citation1990), identified leadership behaviour as one of the antecedents of psychological safety.

Psychological safety gives sense to the idea that employees will not be humiliated, ignored, or punished for their suggestions or ideas on issues; instead, they will be given the sense of confidence. This confidence is a result of trust and mutual respect between supervisors and supervisees. Therefore, the way principals work and behave in the workplace is very likely to influence the teachers’ sense of confidence that is psychological safety. This argument is in line with the key tenet of servant leadership theory that through empowerment and behaving ethically, servant leaders help supervisees grow and succeed and increase trust in leaders among them (Brohi, Jantan, Sobia, & Pathan, Citation2018; Chan & Mak, Citation2014; Kashyap & Rangnekar, Citation2016; Krog & Govender, Citation2015; Reed, Vidaver-Cohen, & Colwell, Citation2011). Moreover, supervisors’ characteristics of emotional healing, putting subordinates first, and helping subordinates grow to enhance followers’ sense of confidence within the organisation that they will not be punished or rejected on sharing their views and making decisions. Thus, the way servant leaders treat followers act as an important function in enhancing the followers’ psychological safety.

Thus, based on the literature, it is expected that the principals with servant leadership characteristics would likely to be viewed as an indicator to increase teachers’ sense of confidence. These indicators then ease the development of teachers’ psychological safety around the servant leadership characteristics of the principals. Thus, the following is hypothesised:

H2: Servant Leadership and psychological safety are positively associated.

2.3. Psychological safety and turnover intention

Once teachers’ psychological safety is fostered by their principals’ servant leadership, teachers strive to be themselves, showing their true selves without even thinking of the negative consequences associated with their character or job. Thus, teachers display positive behaviours of behaving ethically, being engaged, being committed, and in turn, it increases performance which leads to job satisfaction and reduced intention to leave. Employee retention is becoming more important nowadays than ever before because of ever-changing trends, in particular, the paradigm shift of power relationship from employer to employees (Dries, Citation2013). The factors contributing to employee retention and reducing employee’s intention to leave are of utmost importance. Employees who are satisfied, committed, and feeling engaged at the workplace are most likely to stay with the organisation and thus results in increased overall organisational performance.

Thus, building upon the preceding arguments, the following is hypothesised:

H3: Psychological Safety is negatively related to turnover intention.

2.4. The mediating role of psychological safety between servant leadership and turnover intention

Following the relationships hypothesised in H1, H2, and H3, it is rational and timely to investigate psychological safety as the intervening psychological mechanism through which principals’ servant leadership influences teachers’ turnover intention. Building upon social exchange theory (Homans, Citation1958), it can be assumed that principals’ servant leadership enables the development of teachers’ psychological safety through behaving ethically, empowering, and putting subordinates first and in exchange teachers will reciprocate the servant leader behaviour by engaging in the activities which lead to job satisfaction, high performance, and ultimately in decreased turnover intention. Building upon the above arguments, the following is hypothesised:

H4: Teachers’ perception of psychological Safety mediates the relationship between principals’ servant leadership and teachers’ turnover intention.

A related question that arises is whether principals’ servant leadership always decreases teachers’ turnover intention? If not, what are the dispositional factors that influence this relationship? To address the issue discussed earlier, a dispositional factor (i.e., teachers’ regulatory focus) is investigated as the boundary condition of the indirect effect of psychological safety between servant leadership and turnover intention relationship.

2.5. The moderating role of promotion focus and prevention focus in the relationship between servant leadership and psychological safety

Developed from self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, Citation1987, Citation1989), the regulatory focus theory, as defined by Crowe and Higgins (Citation1997), consists of two orientations that employees can adapt to achieve their objectives or targets, i.e., promotion focus and prevention focus. The employees who adopt promotion focus tend to concentrate on fulfilling hopes and aspire for achievement rather than focusing on duties and obligations. The individuals with promotion focus orientation thrive for success, opportunities, and rewards rather than avoid criticism or punishment (Brockner and Higgins (Citation2001)). Promotion focus individuals primarily work toward advancement and progress instead of flourishing for safety or protection. Crowe and Higgins (Citation1997) contended that individuals with promotion focus orientation incline toward achieving such goals by directing their devotion to possible gains or benefits instead of looking for reasonable costs or losses associated with the activity, thus feeling a personal state of resemblance, or regulatory fit, when they believe that the objects or events will maximise the gains or benefits (Higgins, Citation2000). Subsequently, this sense of personal state or similarity nurtures perseverance, engagement, commitment, trust, and satisfaction (Freitas & Higgins, Citation2002; Tory Higgins, Idson, Freitas, Spiegel, & Molden, Citation2003).

Consequently, promotion-focus-oriented employees perform activities or select course of action which provide them benefits or gains, regardless of considering the losses, and thus show risk-taking behaviour rather than thoughtful propensities.

On the other hand, people with a prevention focus orientation make efforts to perform their duties and fulfil their responsibilities instead of pursuing hopes and ambitions (Higgins, Citation1998). Prevention focus orientation progressed as a means to prevent or redress instantaneous difficulties, such as punishment from higher authorities or immediate supervisor (Brockner & Higgins, Citation2001). Prevention focus orientated individual’s set targets related to safety or security issues, and their attention becomes biased toward potential losses associated with objectives set to achieve. Employees perceive regulatory fit when the objects or events that could minimise costs and losses are identified (Crowe & Higgins, Citation1997). Consequently, they consider possibilities that will prevent or mitigate deficits or losses instead of maximising gains or benefits (Higgins, Citation1998).

Employees’ regulatory focus is likely to influence the benefits of servant leadership in reducing employees’ turnover intention in educational settings. Moreover, leaders who show serving behaviour, behave ethically, help subordinates grow and succeed, and develop serving nature in followers foster greater work engagement, increase trust in leadership, and increase organisational commitment and job satisfaction among employees who adopt a promotion focus. Accordingly,

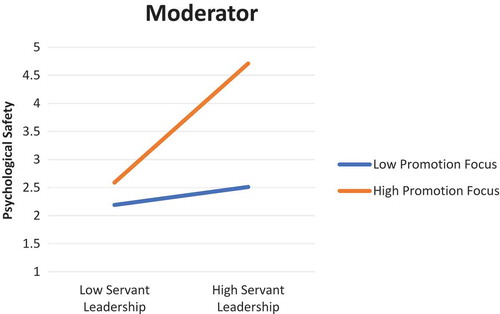

H5: The positive relationship between servant leadership and psychological safety becomes more pronounced as promotion focus increases.

Individuals with a prevention focus orientation are most likely to establish a diverse pattern of observations. They are more concerned about the sense of safety in the team as well as in the organisation to avoid any pain or loss they can face. In this regard, the emotional healing and people-centric approach of servant leaders could raise the values the followers try to reach and the responsibilities they pursue to accomplish, which decreases possible losses. As explained in the self-discrepancy theory, potential losses increase undesirable affect amongst employees who adopt a prevention focus orientation (Higgins, Citation1987; Semin, Higgins, de Montes, Estourget, & Valencia, Citation2005; Shah, Higgins, & Friedman, Citation1998), which results in low engagement (Baumann & Kuhl, Citation2005) and increased job dissatisfaction (e.g., Judge & Ilies, Citation2004) resulting in turnover intention. Thus,

H6: The positive relationship between servant leadership and psychological safety becomes more pronounced as prevention focus increases.

Considering the relationships predicted by H4 and H5, it is logical to argue that the indirect effect of psychological safety in the relationship of servant leadership on turnover intention is conditional on the moderating effects of promotion focus and prevention focus. For instance, as shown in Figure , the first path (servant leadership to psychological safety) of the hypothesised research model is moderated by promotion and prevention focus components of regulatory focus. In other words, the moderator (i.e., promotion and prevention focus) makes the mediating effect of psychological safety between servant leadership and turnover intention conditional on the values of the moderator. As such, the following are hypothesised:

H7: The indirect effect of psychological safety between servant leadership and turnover intention is conditional on the moderating effect of promotion focus, such that the indirect effect of psychological safety is stronger at high levels of promotion focus than at low levels of promotion focus.

H8: The indirect effect of psychological safety between servant leadership and turnover intention is conditional on the moderating effect of prevention focus, such that the indirect effect of psychological safety is stronger at low levels of prevention focus than at high levels of prevention focus.

3. Method

In this study, we used cluster sampling technique to collect data from target respondents. In the initial process, public and private schools operating in Pakistan were identified and divided into different clusters based on the regional locations which include the provinces, i.e., Sindh, Punjab, Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and Federal Territory Islamabad.

Further, to be more specific, from these clusters, sub-clusters are used for data collection which is the district headquarters. Sindh is selected as the main cluster from the five clusters. Furthermore, District Khaiprur Mirs is chosen as a sub-cluster because it hosts more than 10 universities. Researchers determined this sub-cluster as we believe that for higher education institutes, the quality education in secondary schools is essential. The quality of education is dependent on the performance of teachers. This study focused on the private schools. The reason to select private schools is that in private schools the workload is higher than public schools because of the organised structure and performance-based appraisal system, whereas in public schools, because of the job security (permanent job status) teachers do not intend to leave the school. However, in private schools, the workload, work stress, demanding job, and administration pressure cause challenging work environment which may lead to turnover intention. Considering the working conditions and challenges faced by private schoolteachers, this study is conducted in private schools to curb the issue of turnover intention among schoolteachers. In doing so, 10 Franchise schools were selected for data collection. The selection of franchise schools is based on the number of students in these schools. Because of maintaining the higher standards in providing quality education, these schools attract more students. As the target population is not more than 500 schoolteachers, all the teachers were selected for data collection and questionnaires were personally distributed among the teachers. Of the total questionnaires distributed, 255 responses were recorded. According to Krejcie and Morgan (Citation1970), the required sample size for a population of 500 respondents is 217 responses. The returned responses exceed the needed sample size because questionnaires were distributed personally and proper follow-up was done, which results in a 100% response rate.

3.1. Measures

Servant leadership was measured through a 7-item scale (Liden et al., Citation2015), a short form of servant leader scale (SL-28) developed by Liden et al. (Citation2008). A sample item is “My supervisor gives me the freedom to handle difficult situations in the way that I feel is best.” The reliability of this scale for this study was 0.95.

Psychological safety was measured by a 3-item scale adapted from Edmondson (Citation1999), on a response scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” (1) to “Strongly Agree” (2). A sample item is “It is safe for me to speak up around here.” The reliability of this scale is 0.97.

Employee regulatory focus was measured by using a 12-item scale (6 items for promotion focus and 6 items for prevention focus) developed by Higgins (Citation1998). A sample item from the promotion focus scale is “How often do you focus on your work accomplishments?”, and from prevention, the focus is “How often do you focus on completing work tasks correctly?”. The reliabilities for promotion focus and for prevention focus scale in this study were 0.91 and 0.90, respectively.

Intention to leave was measured by using a 4-item scale developed by Reilly, Charles, and David (Citation1991). A sample item is “I have thought seriously about changing organisations since beginning to work here.” The reliability of this scale for this study was 0.93.

Control variables: Teachers’ gender, age, experience, and education level were used as control variables to isolate their effects from the effects of the main variables of this study.

4. Data analysis and results

The hypothesised research model was tested using SPSS and AMOS version 23. To test for the factorial validity of all the measures used in this study, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted. The fit of indices used to measure the model adequacy included Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), standardised root mean square residual (SRMR), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). CFI and TLI values higher than 0.95 and SRMR and RMSEA values less than 0.055 represent an ideal model fit (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, Citation2010) presented in Table . As shown in Table , the baseline five-factor model, consisting of servant leadership, psychological safety, promotion focus, prevention focus, and turnover intention, indicated an excellent fit with the data (i.e., CFI = 0.974, TLI = 0.970, SRMR = 0.072, and RMSEA = 0.049). Further, the construct reliability and validity were tested by analysing the correlations and standard regression weights from AMOS output and calculated using stats tool package. The results as shown in Table show excellent reliability and validity.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations

Furthermore, the three alternative measurement models (Bentler & Bonett, Citation1980) were tested and compared with the baseline five-factor model. For the first alternative model, psychological safety was merged with turnover intention. For the second alternative model, promotion and prevention focus were combined in one construct. For the third alternative model, all measures were loaded on a single latent factor; however, the alternative models indicated poor fit indices with data. There, the baseline five-factor model was retained because of its superior fit indices over the three alternative models.

To confirm the direction and size of the relationships between all variables, correlation analysis was performed. Moreover, the moderated mediation model was analysed using the CB-SEM technique. After confirming for the data normality (Mardia’s coefficient = < 3), the maximum likelihood method of estimation and bootstrap method (5000 iterations) were employed. Moreover, user-defined sample estimands in AMOS v.23 were applied to compute the 95% confidence interval of the direct and indirect effects using a 5000 bias-corrected bootstrapping sample method.

4.1. Tests of direct and moderating effects

The maximum likelihood method of estimation was implied to test the moderating effects. We began the analysis by testing H1 regarding the direct and negative relationship of servant leadership on turnover intention. The results supported the hypothesised relationship (estimate = −0.687, Standard Error = 0.056, t-value = −12.256, p-value = 0.000) as shown in Table . The data also supported H2 regarding the direct and positive relationship between servant leadership and psychological safety; principal’s servant leadership was related significantly and positively with teacher’s psychological safety (estimate = 0.610, SE = 0.094, CR = 6.513, p-value = 0.000). Moreover, H3 was also supported by the data; teachers’ psychological safety had a significant negative relationship with teachers’ turnover intention (estimate = −0.180, SE = 0.041, t-value = −4.401, p-value = 0.000). After testing for the direct effects, the conditional effect of promotion and prevention focus on the direct relationship between servant leadership and psychological safety was examined. The results supported H5, that promotion focus moderates the direct effect of servant leadership on psychological safety. However, H6, the conditional effect of prevention focus between servant leadership and psychological safety, was not supported. There is no conditional effect of prevention focus on the direct effect of servant leadership and psychological safety.

Table 2. CFA models fit indices

Table 3. Direct and moderating effect

Table 4. Unconditional and conditional indirect effects

To further establish the direction of the conditional effect of promotion focus on servant leadership and psychological safety relationship, the significant interaction effect was probed in a graph (see Figure ). The graph showed that servant leadership’s positively significant relationship between servant leadership and psychological safety was stronger when the promotion focus was at a higher level than when at a lower level.

4.2. Tests of unconditional and conditional mediating effects

The mediating and conditional mediation effects of psychological safety in the relationship between servant leadership and turnover intention were tested using CB-SEM with 5000 bootstrap resampling. For the unconditional mediating effect, a two-step approach of Preacher et al. (Citation2007) was followed. This approach involved, first, testing for a significant relationship between the independent and mediating variable and then testing for a significant relationship between the mediating and dependent variable. Since both conditions were supported in H2 and H3, the moderated mediation effect of psychological safety between servant leadership and turnover intention was calculated. The unstandardised beta values indicated that the mediating effect (effect = −0.095, SE = 0.038, LLCI = −0.188, ULCI = −0.034, p-value = 0.002) was significant, that is, the LLCI or the ULCI did not contain zero values (Hayes, Citation2015), the results are presented in Table . Thus, H4 was also supported by the data.

Finally, H7 and H8 regarding the conditional indirect effect of psychological safety on servant leadership and turnover intention relationship were tested in the moderated mediation analysis. The bootstrapped results, established at the three selected levels of promotion focus (i.e., 1 SD, M SD, and + SD), supported the conditional mediating effect of psychological safety between servant leadership and turnover intention that increased with the increased levels of the moderator. More specifically, the mediating effect was significant at both the mean levels (effect = −0.110, SE = 0.051, LLCI = −0.240, ULCI = −0.035, p-value = 0.001) and above mean level (effect = −0.205, SE = 0.096, LLCI = −0.447, ULCI = −0.063, p-value = 0.001) but not at the below mean level (estimate = −0.015, SE = 0.021, LLCI = −0.071, ULCI = 0.018, p-value = 0.300) of promotion focus that contained zero in LLCI. Thus, these results fully supported H7. However, we did not find any support for H8, that is, the indirect effect of psychological safety on servant leadership and turnover intention will be stronger among employees with lower levels of prevention focus. Thus, the hypothesis was not supported by the data.

5. Discussion

Building on the social exchange theory, in this study, we tested the moderated mediation model of servant leadership, psychological safety, employees’ regulatory focus, and turnover intention. This study supported the model that promotion focus moderated the mediating effect of psychological safety on servant leadership and turnover intention relationships. However, prevention focus had no significant impact on servant leadership and turnover intention relationship. Consistent with earlier research, the results of the CB-SEM analysis revealed that employees’ perception of servant leadership behaviour and psychological safety could significantly reduce the turnover intention and also servant leadership can enhance employees’ perceptions of psychological safety (H1, H2, and H3).

Furthermore, the current study investigated the specific mechanism through which servant leadership envisages turnover intention through the excessive expression of psychological safety (H4). In addition, based on past reviews, the current research proposed that psychological safety alone may not predict the turnover intention, the dispositional factors also impact the perception of employees; thus, in this study, we investigated the conditional role of regulatory focus (i.e., promotion and prevention) between servant leadership and psychological safety (H5 and H6). Furthermore, based on the arguments developed from previous studies, we expanded by hypothesising that the indirect path was conditional to employees regulatory focus (promotion and prevention), and subsequently, a moderated mediation model was proposed (H7 and H8).

Explicitly, the partial indirect effect of psychological safety on servant leadership and turnover intention showed that servant leadership could directly and indirectly, via psychological safety, affect turnover intention. This finding supported the basic tenets of the social exchange theory that servant leader behaviour, a positive and follower development centric leader behaviour, has motivational potential, healing power, and altruistic love, thus leading to high psychological safety as a reciprocal outcome, ultimately affecting follower outcomes, i.e., turnover intention of schoolteachers (Dutta & Khatri, Citation2017; Kashyap & Rangnekar, Citation2016). While past studies show an association between servant leadership and turnover intention, but limited studies have been found on the psychological mechanism underlying this relationship; therefore, the present study is the first to explore its internal psychological mechanism in the Pakistani context. Moreover, by unravelling the indirect relationship, psychological safety could be a target for intervention. Indeed, many empirical studies in organisational research have shown that various organisational and individual level antecedents enhance employees’ psychological safety (Chughtai, Citation2016; Edmondson & Lei, Citation2014; Frazier, Fainshmidt, Klinger, Pezeshkan, & Vracheva, Citation2017). Therefore, this study embodies an imperative progression of our understanding of the role of servant leadership and psychological safety in the organisational context. It is noteworthy that social exchange theory emphasises a reciprocal relationship between leader and follower, employer, and employee; for example, the followers reciprocate the supportive and positive behaviour of their leaders positively by showing work engagement and exhibiting job commitment and increased performance. On the other hand, the follower with negative perception of their immediate leaders exhibit negative behaviours of deviance, absenteeism, decreased performance, and eventually voluntary turnover as an exchange relationship of perceived behaviours (Jaramillo, Grisaffe, Chonko, & Roberts, Citation2009a; Jaramillo et al., Citation2009b; Rodriguez, Citation2016; Sun & Wang, Citation2016). Thus, the supported H1 regarding the significant and negative relationship of servant leadership on turnover intention is in line with the theory and previous studies.

Furthermore, the finding of this study regarding H2, Chughtai (Citation2016) reported a positive relationship between servant leadership and psychological safety as well. Thus, the supported H2 regarding the significant and positive relationship between servant leadership and psychological safety is consistent with previous studies. Moreover, to the best knowledge of the researchers, no any traceable research has been found on the direct and indirect effect of psychological safety on turnover intention and so any direct comparison cannot be made. However, an indirect comparison of the findings of this study with previous studies that investigated the role of psychological safety with other follower outcomes can be made. For instance, Chughtai (Citation2016) also reported a significant indirect effect of psychological safety on servant leadership and employee voice behaviour and negative feedback seeking behaviour relationship. While investigating the leadership behaviour and employee voice, Detert and Burris (Citation2007) reported that psychological safety had a mediating effect between employees’ perception of leadership behaviour and voice behaviour. Thus, the supported H3 and H4 regarding the direct negative relationship of psychological safety with turnover intention and mediating effect between servant leadership and turnover intention are consistent with previous leadership studies.

Similarly, the supported H5 regarding the conditional effect of promotion focus on the relationship between servant leadership and turnover intention is consistent with previous studies. For instance, Kark and Van. Dijk (Citation2007) found that charismatic leadership is more motivating and transformational for their subordinates in boosting them toward focusing on promotion. Brockner and Higgins (Citation2001) reported that leadership gives the meanings or forms the purposes by using types of symbols or language to influence the regulatory focus of employees. The more the words of the leader focus on the ideal, the more likely they are to stimulate the subordinates’ promotion focus, and the more the leader focuses on responsibility, obligation, and accuracy, the more likely they are to motivate subordinates’ prevention focus and to encourage subordinates to pursue more ought selves which refers to the self-guide attached to ideas about who persons feel they should be or should become. These selves are typically concerned with safety and responsibility. However, for H6, no support has been found regarding the moderating role of prevention focus between servant leadership and psychological safety. Taken together, the supported H1, H2, H3, H4, and H5 are consistent with both previous leadership studies and social exchange theory, which suggests that employees reciprocate the behaviour of their servant leaders and then they become servant leaders.

Finally, the supported H7, that is, the moderated mediation effect is also consistent with previous studies. For instance, Liden et al. (Citation2014) suggested that servant leadership might not be appropriate for all kinds of employees; rather, some other dispositional, cultural, and contextual factors could be the boundary conditions for the direct and indirect effects of servant leadership on employee behaviours (e.g., turnover intention). However, no support has been found for the prevention focus (i.e., H8) on the conditional indirect effect of psychological safety between servant leadership and turnover intention. Consistent with past studies, Brockner and Higgins (Citation2001), also reported that promotion focus and prevention focus could not go hand in hand, the existence of the other will suppress either of them, and the stimulation of promotion focus will suppress the prevention focus and vice versa.

5.1. Contributions

5.1.1. Theoretical implications

This study’s contributions to expanding the servant leadership literature is threefold. Firstly, as stated before, the research work carried on servant leadership is still in its infancy and consequently very little has been done to unveil its effects on the follower and organisational outcomes (Avolio, Reichard, Hannah, Walumbwa, & Chan, Citation2009).

Consequently, by relating servant leadership in the context of turnover intention in Pakistan, for the first time, this research work not only helps in contributing a novel viewpoint on the said concept, but it also delivers suggestion that this leadership style will be proven beneficial for organisations. Secondly, it is also viewed that limited studies have found out the impacts of servant leadership on expected outcomes. Therefore, it is not clear about its intervening mechanism through which it will influence those outcomes. Hence, by going through the observations made regarding the intermediating role of the psychological safety, this study is useful in comprehending that servant leadership role will advance the attitudes and behaviours of the followers. Furthermore, outcomes which are discovered through this study have shown that psychological safety has mediated the impact of servant leadership on turnover intention. These results have also recommended that there may be some other mediating tool other than psychological safety.

Furthermore, as discussed before, the research on servant leadership is in its initial stage; apart from looking at the underlying mechanisms in understanding the consequences of servant leadership, very few studies have been done to understand the dispositional factors which impact the employees’ perception of their servant leaders. Thus, this study examines the moderating role of regulatory focus (promotion focus and prevention focus) between servant leadership and psychological safety relationship. Moreover, the employees’ regulatory focus had been tested for the conditional mediating effect of psychological safety between servant leadership and turnover intention.

5.1.2. Practical implications

Based on the finding of this study, we provided the practical implications. Explicitly, results illustrate that servant leaders can motivate personnel to stay in the organisation, suggest useful insights for change, and raise apprehensions about job-related concerns by developing a sense of psychological safety in the organisation. Consequently, these behaviours will influence and enhance team and organisational performance (Edmondson, Citation1999; LePine & Van Dyne, Citation2001). How could organisations develop the servant leaders? It could be through two strategies by the firms in gaining this objective. In previous research, it was shown that individuals having the ability of agreeableness hold firm possession of serving others and they possess high moral and ethical values, and they become servant leaders by imitating helping nature of their leaders (Hunter et al., Citation2013; van Dierendonck, Citation2011). Therefore, by adopting the personality and integrated tests, organisations can try to recognise and hire leaders of such qualities. Moreover, by following appropriate training programmes, organisations could help their managers in the acquisition of servant leadership behaviours. Such programmes try to focus on encouraging their employees in fulfilling their desired needs of empowerment, growth, and rewarded with dignity.

5.1.3. Limitations and future research directions

This study has certain limitations. For example, the data was collected from a single source that is from teachers working in the public and private schools in Pakistan that could not reduce the response bias because of the elements of the social desirability. Thus, future research should replicate and extend the findings of this moderated mediation model by collecting data from leader-follower dyads to reduce the response bias. Secondly, the results were generated using cross-sectional data that could not establish causality within the hypothesised research model. Thus, future research should replicate and extend the findings through a longitudinal research design.

6. Conclusion

This research on the state of the servant leadership research has revealed some significant theoretical implications and answered the call of numerous researchers on understanding and carrying out more research in servant leadership literature. The present study supported the results and exhibits that follower outcomes can be increased by the excessive expression of servant leadership with the mediating role of employees’ perception of psychological safety under the conditions of employees’ promotion focus.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Noor Ahmed Brohi

Noor Ahmed Brohi is pursuing his Ph.D. in Management from Putra Business School, University Putra Malaysia. His areas of interest are human resource management, leadership, human resource development, and organisational behaviour.

References

- Ahmed, A., Khuwaja, F. M., Brohi, N. A., Othman, I., & Bin, L. (2018). Organizational factors and organizational performance: A resource-based view and social exchange theory viewpoint. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(3), 579–599. doi:10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i3/3951

- Akhtar, M. S., Salleh, L. M., Ghafar, N. H., Khurro, M. A., & Mehmood, S. A. (2018). Conceptualizing the impact of perceived organizational support and psychological contract fulfillment on employees’ paradoxi- cal intentions of stay and leave. International Journal of Engineering and Technology(UAE), 7(5), 9–14. doi:10.14419/ijet.v7i2.5.10045

- Arain, G. A. (2017). The impact of leadership style on moral identity and subsequent in-role performance: A moderated mediation analysis. Ethics & Behavior, 1–15. doi:10.1080/10508422.2017.1336622

- Avolio, B. J., Reichard, R. J., Hannah, S. T., Walumbwa, F. O., & Chan, A. (2009). A meta-analytic review of leadership impact research: Experimental and quasi-experimental studies. Leadership Quarterly, 20(5), 764–784. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.06.006

- Barbuto, J. E., & Wheeler, D. W. (2006). Scale development and construct clarification of servant leadership. Group & Organization Management, 31(3), 300–326. doi:10.1177/1059601106287091

- Baumann, N., & Kuhl, J. (2005). How to resist temptation: The effects of external control versus autonomy support on self-regulatory dynamics. Journal of Personality, 73(2), 443–470. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00315.x

- Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588–606. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588

- Black, G. L. (2010). Correlational analysis of servant leadership and school climate. Servant Leadership and School Climate, 13(4), 437–466. doi:10.1080/13632430220143024

- Brockner, J., & Higgins, E. T. (2001). Regulatory focus theory: Implications for the study of emotions at work. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86(1), 35–66. doi:10.1006/obhd.2001.2972

- Brohi, N. A., Jantan, A. H., Sobia, A. M. S., & Pathan, T. G. (2018). Does servant leadership style induce positive organisational behaviors? A conceptual study of servant leadership, psychological capital, and intention to quit relationship. Journal of International Business and Management, 1(1), 1–11.

- Cerit, Y. (2009). The effects of servant leadership behaviours of school principals on teachers’ job satisfaction. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 37(5), 600–623. doi:10.1177/1741143209339650

- Chan, S. C. H., & Mak, W. (2014). The impact of servant leadership and subordinates’ organizational tenure on trust in leader and attitudes. Personnel Review, 43(2), 272–287. doi:10.1108/PR-08-2011-0125

- Chiniara, M., & Bentein, K. (2016). Linking servant leadership to individual performance: Differentiating the mediating role of autonomy, competence and relatedness need satisfaction. The Leadership Quarterly, 27(1), 124–141. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.08.004

- Chughtai, A. A. (2016). Servant leadership and follower outcomes: Mediating effects of organizational identification and psychological safety. The Journal of Psychology, 150(7), 866–880. doi:10.1080/00223980.2016.1170657

- Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., & Perry, N. E. (2011). PREDICTING TEACHER COMMITMENT: THE IMPACT OF SCHOOL CLIMATE AND SOCIAL–EMOTIONAL LEARNING. Psychology in the Schools, 48(10), 1034–1048. doi:10.1002/pits

- Cotton, J. L., & Tuttle, J. M. (1986). Employee turnover: A meta-analysis and review with implications for research. The Academy of Management Review, 11(1), 55. doi:10.2307/258331

- Crowe, E., & Higgins, E. T. (1997). Regulatory focus and strategic inclinations: Promotion and prevention in decision-making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 69(2), 117–132. doi:10.1006/obhd.1996.2675

- Deconinck, J. B., & Deconinck, M. B. (2017). The relationship between servant leadership, perceived organizational support, performance, and turnover among business to business salespeople. Archives of Business Research, 5(10), 57–71. doi:10.14738/abr

- Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 869–884. doi:10.5465/AMJ.2007.26279183

- Donia, M. B. L., Raja, U., Panaccio, A., & Wang, Z. (2016). Servant leadership and employee outcomes: The moderating role of subordinates’ motives. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25(5), 1–13. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2016.1149471

- Dries, N. (2013). The psychology of talent management: A review and research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 23(4), 272–285. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2013.05.001

- Dutta, S., & Khatri, P. (2017). Servant leadership and positive organizational behaviour: The road ahead to reduce employees’ turnover intentions. On the Horizon, 25(1), 60–82. doi:10.1108/OTH-06-2016-0029

- Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–352. doi:10.2307/2666999

- Edmondson, A. C., & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 23–43. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091305

- Emerson, R. M., John, H., Harold, T., & Blau, P. (1976). Social exchange theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 2, 335–362. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.02.080176.002003

- Frazier, M. L., Fainshmidt, S., Klinger, R. L., Pezeshkan, A., & Vracheva, V. (2017). Psychological safety: A meta-analytic review and extension. Personnel Psychology, 70(1), 113–165. doi:10.1111/peps.12183

- Freitas, A. L., & Higgins, E. T. (2002). Enjoying goal-directed action: The role of regulatory fit. Psychological Science, 13(1), 1–6. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00401

- Fuller, J. B., Morrison, R., Jones, L., Bridger, D., & Brown, V. (1999). The effects of psychological empowerment on transformational leadership and job satisfaction. Journal of Social Psychology, 139(3), 389–391. doi:10.1080/00224549909598396

- Greenleaf, R. K. (2002). Servant leadership: A journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness (25th-anniversary ed.) (L. C. Spears, Ed.). Mahwah, NJ, US: Paulist Press.

- Gregory Stone, A., Russell, R. F., & Patterson, K. (2004). Transformational versus servant leadership: A difference in leader focus. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 25(4), 349–361. doi:10.1108/01437730410538671

- Griffeth, R. W., Hom, P. W., & Gaertner, S. (2000). A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. Journal of Management, 26(3), 463–488. Retrieved from http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-0000203435&partnerID=tZOtx3y1

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2010). Multivariate data analysis. Prentice Hall.

- Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(1), 37–41. doi:10.1080/00273171.2014.962683

- Higgins, E. T. (1987). Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94(3), 319–340. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.319

- Higgins, E. T. (1989). Self-discrepancy theory: What patterns of self-beliefs cause people to suffer? Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 22(C), 93–136. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60306-8

- Higgins, E. T. (1998). Promotion and prevention. Regulatory focus as a motivational principle.pdf. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 30, 1–46.

- Higgins, E. T. (2000). Making A good decision: Value from fit. American Psychologist, 30(November), 1217–1230.

- Higgins, E. T., Shah, J., & Friedman, R. (1997). Emotional responses to goal attainment: Strength of regulatory focus as moderator. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(3), 515–525. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.72.3.515

- Hoch, J. E., Bommer, W. H., Dulebohn, J. H., & Wu, D. (2016). Do ethical, authentic, and servant leadership explain variance above and beyond transformational leadership? A meta-analysis. Journal of Management, XX(X), 014920631666546. doi:10.1177/0149206316665461

- Homans, G. (1958). Social Behavior as Exchange. American Journal of Sociology, 63(6), 597–606. doi:10.1086/222355

- Hunter, E. M., Neubert, M. J., Perry, S. J., Witt, L. A., Penney, L. M., & Weinberger, E. (2013). Servant leaders inspire servant followers: Antecedents and outcomes for employees and the organization. Leadership Quarterly, 24(2), 316–331. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.12.001

- Jaramillo, F., Grisaffe, D. B., Chonko, L. B., & Roberts, J. A. (2009a). Examining the impact of servant leadership on sales force perforamance. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 29(3), 257–276. doi:10.2753/PSS0885-3134290304

- Jaramillo, F., Grisaffe, D. B., Chonko, L. B., & Roberts, J. A. (2009b). Examining the impact of servant leadership on salesperson’s turnover intention. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 29(4), 351–366. doi:10.2753/PSS0885-3134290404

- Judge, T. A., & Ilies, R. (2004). Affect and job satisfaction: A study of their relationship at work and at home. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(4), 661–673. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.89.4.661

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724. doi:10.2307/256287

- Kark, R., & Van. Dijk, D. (2007). Motivation to lead, motivation to follow: The role of the self-regulatory focus in leadership processes. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 500–528. doi:10.5465/amr.2007.24351846

- Kashyap, V., & Rangnekar, S. (2016). Servant leadership, employer brand perception, trust in leaders and turnover intentions: A sequential mediation model. Review of Managerial Science, 10(3), 437–461. doi:10.1007/s11846-014-0152-6

- Kossek, E., & Ozeki, C. (1998). Work-family conflict, policies, and the job-life satisfaction relationship: A review and directions for organizational behavior-human resources research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(2), 139–149. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.83.2.139

- Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 38, 607–610. doi:10.1177/001316447003000308

- Krog, C. L., & Govender, K. (2015). The relationship between servant leadership and employee empowerment, commitment, trust and innovative behaviour: A project management perspective. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 13(1), 1–12. doi:10.4102/sajhrm.v13i1.712

- LePine, J. A., & Van Dyne, L. (2001). Voice and cooperative behavior as contrasting forms of contextual performance: Evidence of differential relationships with big five personality characteristics and cognitive ability. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(2), 326–336. doi:10.1037//0021-9010.86.2.326

- Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Liao, C., & Meuser, J. D. (2014). Servant leadership and serving culture: Influence on individual and unit performance. Academy of Management Journal, 57(5), 1434–1452. doi:10.5465/amj.2013.0034

- Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Meuser, J. D., Hu, J., Wu, J., & Liao, C. (2015). Servant leadership: Validation of a short form of the SL-28. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(2), 254–269. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.12.002

- Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Zhao, H., & Henderson, D. (2008). Servant leadership: Development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. Leadership Quarterly, 19(2), 161–177. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.01.006

- Lindahl, M. G., & Folkesson, A. M. (2012). ICT in preschool: Friend or foe? The significance of norms in a changing practice. International Journal of Early Years Education, 20(4), 422–436. doi:10.1080/09669760.2012.743876

- Lindahl, R. A. (2010). Be a better leader, have a richer life. Journal of Leadership Studies, 3(4), 34–45. doi:10.1002/jls

- Loher, B. T., Noe, R. A., Moeller, N. L., & Fitzgerald, M. E. (1985). A meta-analysis of the relation of job characteristics to job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 70(2), 280–289. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.70.2.280

- Macintosh, E. W., & Doherty, A. (2010). The influence of organizational culture on job satisfaction and intention to leave. Sport Management Review, 13(2), 106–117. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2009.04.006

- Miskel, C. G., Fevurly, R., & Stewart, J. (1979). Organizational structures and processes, perceived school effectiveness, loyalty, and job satisfaction. Educational Administration Quarterly, 15(3), 97–118. doi:10.1177/0013131X7901500308

- Newman, A., Schwarz, G., Cooper, B., & Sendjaya, S. (2017). How servant leadership influences organizational citizenship behavior: The roles of LMX, empowerment, and proactive personality. Journal of Business Ethics, 145(1), 49–62. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2827-6

- Northouse, P.G (2017). Leadership : theory and practice / P.G. Northouse

- Porter, L. W., Steers, R. M., Mowday, R. T., & Boulian, P. V. (1974). Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59(5), 603–609. doi:10.1037/h0037335

- Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227. doi:10.1080/00273170701341316

- Reed, L. L., Vidaver-Cohen, D., & Colwell, S. R. (2011). A new scale to measure executive servant leadership: Development, analysis, and implications for research. Journal of Business Ethics, 101(3), 415–434. doi:10.1007/s10551-010-0729-1

- Reilly, O., Charles, A., & David, F. (1991). People and organizational culture : A profile comparison approach to assessing. Academy of Management, 34(3), 487–516.

- Rodriguez, B. (2016). Reducing employee turnover in retail environments: An analysis of servant leadership variables. Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies. Retrieved from http://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations/2758

- Russell, R. F., & Stone, A. G. (2002). A review of servant leadership attributes: Developing practical model. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 23(3), 145–157. doi:10.1108/01437730210424084

- Schein, E. H., & Bennis, W. G. (1965). Personal and organizational change through group methods: The laboratory approach. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 17(1), 105–106.

- Semin, G. R., Higgins, T., de Montes, L. G., Estourget, Y., & Valencia, J. F. (2005). Linguistic signatures of regulatory focus: How abstraction fits promotion more than prevention. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(1), 36–45. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.89.1.36

- Shah, J., Higgins, T., & Friedman, R. S. (1998). Performance incentives and means: How regulatory focus influences goal attainment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(2), 285–293. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.74.2.285

- Shah, S. M. M., Ali, R., Dahri, A. S., Brohi, N. A., & Maher, Z. A. (2018). Determinants of job satisfaction among nurses: Evidence from South Asian perspective. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(5), 19–26. doi:10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i5/4082

- Shaw, J., & Newton, J. (2014). Teacher retention and satisfaction with a servant leader as principal. Education, 135(1), 101–106.

- SHRM. (2016). Survey findings: Influencing workplace culture through employee recognition and other efforts. (Globoforce. Retrieved from https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/trends-and-forecasting/research-and-surveys/Documents/Employee-Recognition-2016.pdf

- Spears, L. (2004). The understanding and practice of servant leadership. Practicing Servant Leadership: Succeeding through Trust, (August), 9–24. Retrieved from http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&btnG=Search&q=intitle:The+understanding+and+practice+of+servant+leadership#0

- Steel, R. P., & Ovalle, N. K. (1984). A review and meta-analysis of research on the relationship between behavioral intentions and employee turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69(4), 673–686. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.69.4.673

- Sun, R., & Wang, W. (2016). Transformational leadership, employee turnover intention, and actual voluntary turnover in public organizations. Public Management Review, 1–18. doi:10.1080/14719037.2016.1257063

- Tory Higgins, E., Idson, L. C., Freitas, A. L., Spiegel, S., & Molden, D. C. (2003). Transfer of value from fit. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(6), 1140–1153. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.6.1140

- van Dierendonck, D. (2011). Servant leadership: A review and synthesis. Journal of Management, 37(4), 1228–1261. doi:10.1177/0149206310380462

- van Dierendonck, D., & Nuijten, I. (2011). The servant leadership survey: Development and validation of a multidimensional measure. Journal of Business and Psychology, 26(3), 249–267. doi:10.1007/s10869-010-9194-1

- Whitaker, T. (2009). What Great Principals Do Differently. Education World, 1(812). Retrieved from http://www.educationworld.com/a_admin/admin/admin410.shtml