Abstract

This study explores the influence of situational and organizational factors on transparency regarding financial restatements. It is predicted that situational factors related to the severity of a restatement will influence transparency about the event and that an organization’s stakeholder orientation will moderate the relationship between the magnitude of the restatement and transparency. Consistent with predictions, results show a generally positive relationship between the severity of the restatement and transparency in the restatement announcement but also show that firm characteristics such as size, profitability, and stakeholder orientation can alter this relationship. Although transparency following restatements is generally viewed as desirable, we find that among smaller firms transparency is negatively related to the severity of the restatement, and we theorize that this is due to risk aversion triggered by fears that the firm may fail as a result of the restatement. We also find that companies with an individualistic identity orientation alter their transparency following a restatement depending on the severity of the restatement whereas firms which derive organizational identity from relationships with stakeholders or broader groups display a more consistent level of transparency across restatements of varying severity. Taken together, the results of this study provide increased understanding of factors which influence transparency following restatements and suggest that increased attention should be given to the role of organizational characteristics in shaping responses to such events.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Businesses frequently face events which lead to public concern and scrutiny and place managers in the difficult position of deciding how communicate with their constituents in order to ease stakeholders’ concerns and protect their business. There is increasing public advocacy for improved corporate transparency in the wake of negative events and scandals and some research indicates that transparency can sometimes reduce the fallout following a negative event. Nonetheless, there is also evidence that managers are often reluctant to be fully transparent about negative events and that in some cases this reluctance is justified. This research article explores how characteristics of a company and of the event it’s facing can influence the transparency of disclosures managers make regarding negative events. This study of transparency in announcements of financial restatements finds that characteristics of the event and the organization can influence transparency following a negative event.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, calls for increased corporate transparency have been vociferous, leading to regulations such as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and the Dodd Frank Act designed to promote transparency and accountability. Public and regulatory insistence on increased transparency is not surprising given that reliable information from firms allows stakeholders to accurately evaluate a firm’s financial status and make reasonable predictions about future prospects. This ability forms a critical foundation of efficiently functioning markets. In many cases, firms can also benefit from being transparent—or at least from being perceived as so—by avoiding litigation and activism and by gaining trust from stakeholders and reputational assets.

Despite having considerable knowledge about the value of transparency for organizations and their stakeholders, we know little about factors that predict how transparent companies will be when reporting negative accounting events. For stakeholders it is important that firms be transparent with both positive and negative information, yet managers may be more reluctrant to share negative information. In fact, past research has found that managers may actively suppress negative information until it reaches a critical mass or until a particularly inopportune time for bad news has passed (Healy & Palepu, Citation2001; Piotroski, Wong, & Zhang, Citation2015). Thus, while we have some indication that situational factors may influence corporate transparency regarding a restatement event, we do not know whether some firms may be predisposed to being more or less transparent or whether firm and situational characteristics might interact to predict transparency.

The purpose of the current study is to explore both situational and organizational characteristics that predict transparency in firms’ initial restatement announcements. A situation-organization interactionist framework is applied to make predictions. Pertinent characteristics of the situation include the size of the restatement and whether it was caused by an error (innocuous misapplication of GAAP) or an irregularity (intentional misreporting). Relevant firm characteristics include size, profitability, and indications of stakeholder orientation including corporate social performance and the extent to which interdependence with stakeholders is a part of the company’s organizational identity orientation (Brickson, Citation2005). Results of this study indicate that situational factors influence the transparency of restatement announcements such that firms tend to be more transparent when restatements are due to irregularities as opposed to errors and when the financial magnitude of the restatemnt is greater. We also find evidence that firm characteristics including size, profitability, and organizational identity orientation interact with situational factors to further influence transparency.

The following section provides a brief discussion of relevant literature integrating research related to corporate responses to negative events and stakeholder relations with research in accounting and financial reporting to develop predictions about situational and organizational factors which impact transparency in restatement announcements. This theoretical contribution provides new insights into the forces which drive organizations to be more or less transparent when faced with a restatement event. Next, the study’s context, design, analytical approach, and results are described. The paper closes with a discussion of the findings, consideration of limitations, and suggestions for future research.

2. Literature review

2.1. Responses to negative events

The literature regarding communicative responses to negative events spans a variety of domains including crisis communication (e.g., Coombs, Citation2007), impression management (e.g., McDonnell & King, Citation2013), and responses to ethical issues (e.g., Garrett, Bradford, Meyers, & Becker, Citation1989; Pfarrer, Decelles, Smith, & Taylor, Citation2008a). The majority of this research has focused on creating typologies of responses (e.g., Coombs, Citation2006; Garrett et al., Citation1989; Szwajkowski, Citation1992) or investigating which responses lead to the most favorable stakeholder reactions under various conditions (Coombs, Citation2007; Marcus & Goodman, Citation1991). Research suggests that organizations may use a variety of communicative responses following a negative event and that the impact of a given response on stakeholder perceptions depends on a variety of situational, organizational, and relational factors (Coombs, Citation2006). If handled properly, communicative responses can help the organization recover goodwill and financial performance (Coombs, Citation2007; Huang, Citation2006) while a poorly managed communicative response can compound undesirable consequences following a negative event (Grebe, Citation2013). Research in this area has not previously explored ways that situational and organizational characteristics may influence or predict firms’ actual responses to negative events.

The model of post-transgression organizational reintegration with stakeholders presented by Pfarrer and his colleagues (Pfarrer et al., Citation2008a) suggests that transparency in reporting about negative events may be particularly critical in the immediate aftermath. Specifically, the model suggests that the process by which organizations reintegrate with stakeholders and regain legitimacy cannot move forward until stakeholders are satisfied with their knowledge regarding what happened. Nonetheless, transparency—defined as the provision and accessibility of firm specific information to those outside of the organization—has been overlooked as a key feature of communicative responses to negative events. This study advances research related to responses to negative events by exploring factors that predict transparency following one type of negative event—financial restatements.

2.2. Stakeholder orientation

Because negative organizational events are typically defined by their deleterious impact on a firms’ stakeholder groups, it is likely that a firm’s concern for, and relationship with, various stakeholder groups, or stakeholder orientation, will play a key role in influencing firms’ transparency about negative events. While some researchers have taken a pragmatic view whereby stakeholder orientation in a function of external pressure exerted by powerful and legitimate stakeholders with urgent claims (Mitchell, Agle, & Wood, Citation1997), more recent work has focused on firms’ intrinsic concerns for stakeholders (Crilly, Citation2011). In this view, stakeholder orientation is largely dependent on managers’ beliefs about stakeholders and the relationship of the firm to various groups (Crilly, Citation2011). Regardless of whether the motivations are intrinsic or extrinsic, stakeholder orientation can be defined as attitudes toward and attention to stakeholders.

The construct which perhaps best captures the fact that beliefs about stakeholder relationships are central, defining characteristics of a firm is Brickson’s (Citation2005, Citation2007) organizational identity orientation. Organizational identity orientation (OIO) is defined as “the nature of assumed relationships between an organization and its stakeholders” (Brickson, Citation2005, p. 577) and can be individualistic, relational, collectivistic, or a hybrid of these types. As an aspect of organizational identity, OIO represents features of the firm that have been internalized as part of who the company is. OIO specifically represents internalized beliefs about stakeholder relationships and is not specific to certain industries or types of organizations. OIO has also been found to be an important link between organizational management and stakeholder engagement (Bartlett, McDonald, & Pini, Citation2015).

An organization with an individualistic OIO tends to define itself in terms of its own positively distinguishing characteristics (Brickson, Citation2005, Citation2007). Such firms tend to be relatively competitive and focused on objective performance metrics. Firms with relational OIOs derive a significant portion of their identities from their relationships with particular partners (Brickson, Citation2005, Citation2007). Such firms are likely to show concern for building and maintaining relationships with stakeholders such as suppliers, customers, or employees. Firms with collectivistic OIOs define themselves in terms of membership in particular groups or as part of a broader community (Brickson, Citation2005, Citation2007). In some cases these collectives are formal groups of organizations such as a local business association or the National Co+Op Grocers (an organization providing membership and services to cooperative natural grocery store throughout the US). In other cases these collectives may be informal such as social networks and comradery between craft brewers in Colorado. Organizations identifying with such collectives are likely to have shared values and similar stakeholder orientations as other group members. Organizations with relational or collectivistic OIOs are more likely than those with individualistic OIOs to evaluate themselves using subjective performance criteria which reflect their commitments to relationship partners or broader social groups. The firms also place a high value on being known as trusted partners.

While OIO best captures firms’ intrinsic stakeholder orientations, corporate social performance serves as a behavioral indicator of firms’ efforts to manage stakeholder relationships and likely captures a combination of intrinsically and extrinsically motivated orientations toward stakeholders. Corporate social performance (CSP) measures the extent to which the firm acts upon values which are consistent with prevailing, societal notions about what constitutes socially beneficial and ethical organizational goals and activities (Campbell, Eden, & Miller, Citation2012; Wood, Citation1991). Engagement is CSP signals concern for stakeholder relations and willingness to adhere to social and ethical standards such as transparency and accountability.

2.3. Financial restatements

Firms are required to issue restatements when it has been determined that a deviation from, or misapplication of, Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) has led to a material misstatement of previously disclosed financial reports (Levy, Citation2011). Financial restatements may be initiated by an internal audit, an external audit, or by recommendations from the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) (Alali & I-Ling Wang, Citation2017). Some restatements, referred to as errors, are due to unintentional mistakes or changes in interpretations of GAAP, while others, referred to as irregularities, involve deliberate manipulations such as fraud, intentional deviations from GAAP, inadequate internal controls, or earnings management.

While irregularities are far more likely than errors to lead to regulatory investigations, class-action lawsuits, and CEO/CFO turnover (Hennes, Leone, & Miller, Citation2008) both types of restatement can be considered negative events. First, effective capital markets hinge on the reliability of firms’ financial disclosures. Restatements are often perceived as a failure of one of, if not the most fundamental responsibilities of publicly traded corporations—the provision of clear and accurate financial reports (GAO, Citation2006; Chakravarthy, de Haan, & Rajgopal, Citation2014). Restatements have a material impact on assessments of firms’ current values as well as their future prospects. Thus, a high incidence of restatement activity among publicly traded firms may diminish the faith that investors place in financial reporting (GAO, Citation2006; Arthaud-Day, Certo, Dalton, & Dalton, Citation2006; Pfarrer, Smith, Bartol, Khanin, & Zhang, Citation2008b). Finally, restatements can lead to a variety of undesirable organizational outcomes including decreased market value, SEC investigations, increased costs associated with debt financing, class action lawsuits, and even firm failure (GAO, Citation2006; Akhigbe, Kudla, & Madura, Citation2005; Palmrose, Richardson, & Scholz, Citation2004; Park & Wu, Citation2009). Restatements also diminish a firm’s credibility and reputation in the eyes of various stakeholder groups (Chakravarthy et al., Citation2014).

The severity of a restatement depends on its size (generally measured as the monetary value of the adjustment relative to total firm revenue or net income), the number and types of accounts which are affected, the number of quarters or years for which the company must amend its financial reports (Palmrose et al., Citation2004), and whether the restatement was caused by intentional irregularities or inocuous errors (Hennes et al., Citation2008). Research has shown that market reactions are more negative when restatements decrease reported earnings, affect multiple accounts, or involve fraud (Palmrose et al., Citation2004).

2.4. Restatement announcements

For the purpose of this study, restatement announcements are examined in terms of transparency. Transparency is defined as the extent to which the organizational statement provides internal information to an external audience so that the audience can better understand the facts and consequences of the event in question. Despite regulations designed to encourage transparent reporting of restatements, (e.g., SEC, Citation2004; SOX, Citation2002), restatement announcements still vary considerably in the amount of information they provide (GAO, Citation2006; Gertsen, Riel, & Berens, Citation2006; Gordon, Henry, Peytcheva, & Sun, Citation2013). For example, restatement announcements may include information about which types of accounts will be affected, the direction of the change in earnings (positive or negative), the monetary amount of the change in earnings, how the misstatement was discovered, and changes in personnel or internal controls resulting from the investigation.

Previous research shows that managers exercise considerable discretion in determining what information is provided in a restatement announcement, and that the information provided can impact financial and legal consequences to the firm (Files, Swanson, & Tse, Citation2009; Gordon et al., Citation2013). For example, empirical research shows that providing information about the monetary amount of the restatement is especially important in attenuating negative market reactions (Gertsen et al., Citation2006; Palmrose et al., Citation2004; Swanson, Tse, & Wynalda, Citation2007). Market reactions to other types of information are less clearly understood. For example, one study finds that market reactions are more negative when restatements are initiated by managers or auditors rather than the SEC (Palmrose et al., Citation2004) while another study reports that market reactions are more negative when the restatement is forced by the auditor or SEC but less negative when it is initiated by management (Akhigbe et al., Citation2005).

What is less clear is whether or not there is a market penalty for simply excluding information about the source of the restatement. Similarly, there is evidence that investors react more negatively to restatements that affect revenue accounts and that affect a greater number of accounts (Akhigbe et al., Citation2005; Palmrose et al., Citation2004), but there is little evidence about whether firms are penalized for simply excluding this information from the restatement announcement. Based on past research, there appear to be instrumental reasons for firms to provide information about the amount of a restatement but less guidance about whether additional transparency will help or harm the firm’s market value. The following section provides predictions about the impact of situational characteristics (i.e., characteristics of the restatement) and organizational characteristics on transparency in restatement announcements.

3. Hypotheses

The benefits of corporate transparency are considerable and well-established, but the consequences of transparency related to negative events, such as financial restatements, are less clear. In general, more transparent firms benefit from improved long-term credit ratings, reduced cost of capital (DeBoskey & Gillett, Citation2013; Healy & Palepu, Citation2001), and more efficient and effective interactions with stakeholders stemming from reduced information costs and reduced transaction costs (Bushman, Piotroski, & Smith, Citation2004; DeBoskey & Gillett, Citation2013). In relation to financial restatements, theoretical and empirical research presents mixed, but potentially reconcilable, messages about the motivations for and consequences of transparency.

Theory suggests that transparency following any type of negative event is critical in reassuring stakeholders and protecting a firm’s financial and reputational value. For example, the post-transgression re-integration model suggests that firms must communicate information about negative events in order to begin to repair relationships with stakeholders and that greater transparency will help speed the re-integration of a transgressing firm with its stakeholders (Pfarrer et al., Citation2008a). Additionally, grounded theory developed specifically within the context of financial restatement announcements suggests that open communication and transparency regarding the nature of the problem plays an important role in protecting market value and minimizing reputational damage by reducing perceptions of the degree to which the firm distorted value-related information (Gertsen et al., Citation2006). In sum, there is a compelling case to be made for the benefits of transparency in restatement announcements.

Despite these prescriptive arguments in favor of transparency, it is intuitive to expect managers to be reluctant to divulge and elaborate upon bad news. Indeed, managers are cognizant of the deleterious effect negative information can have on their firms, and research finds evidence that managers exert control over the timing and extent of releases of bad news (Healy & Palepu, Citation2001). For example, a study of Chinese firms found evidence that managers suppress bad news during highly visible political events which would likely draw additional attention to such events and increase negative impacts on the firms. This study also found an increase in the release of bad news once these political events ended (Piotroski et al., Citation2015), suggesting that managers had deliberately delayed the release of bad news.

Studies related to financial disclosure and earnings management have found evidence that managers stockpile negative accounting information until it reaches a tipping point at which it can no longer be reasonably contained. Once this point has been reached firms often take what has been referred to as a “big bath”—dumping all the bad news at once and in some cases even exaggerating bad news to create a buffer to allow them to further delay future announcements of bad news (Dechow, Ge, Larson, & Sloan, Citation2011; Hutton, Marcus, & Tehranian, Citation2009). Research on investor behavior suggests that this is a relatively savvy approach to releasing bad news because investors underreact to single news items and overreact to a series of good or bad news (Barberis, Shleifer, & Vishny, Citation1998).

3.1. Situational factors

Two key features which determine how damaging a restatement will be are whether it is caused by an irregularity or an error and its financial magnitude—measured here as the absolute value of the restatement divided by the absolute value of the firm’s net income/loss. Irregularities occur when firms must correct financial reports which were intentionally misstated. Such restatements can be particularly damaging to a firm’s reputation and relationships with stakeholders (Gertsen et al., Citation2006; Hennes et al., Citation2008), thus managers are likely to be particularly motivated to protect firm reputation and repair stakeholder relations. Prescriptive theories predict that greater transparency can facilitate these goals by reducing uncertainty, reasserting management’s commitment to integrity, and speeding reintegration with stakeholders (Gertsen et al., Citation2006; Pfarrer et al., Citation2008a). Additionally, irregularities often lead to SEC or Department of Justice (DoJ) investigations and class-action lawsuits on behalf of investors. Managers and accountants faced with announcing irregularities are likely to recognize that information about the restatement will come to light during any investigations or legal proceedings. Thus, they have little to gain by attempting to conceal information and are likely to believe that high transparency in the initial restatement announcement will be viewed favorably by stakeholders, investigators, and adjudicators. For these reasons we anticipate that transparency will be higher in the case of irregularities as opposed to errors.

Hypothesis 1:

Transparency will be greater in restatement announcements of irregularities than in those of errors.

Another key characteristic of a restatement is its financial magnitude which represents the monetary impact of the restatement on a firm’s financial results. The magnitude of a restatement is the overall change in financial position between the initially reported and restated financial reports of the company. Generally restatement magnitude is measured as the net change in profitability due to the restatement as a percentage of the firm’s revenue, net income, or change in earnings per share for that period (Palmrose et al., Citation2004; Wang & Chou, Citation2011). Restatements vary in size, and larger restatements tend to elicit more negative outcomes (including decreased market value, increased risk of litigation, executive turnover, and firm failure) than smaller ones (Hirschey, Palmrose, & Scholz, Citation2005; Palmrose et al., Citation2004; Wang & Chou, Citation2011). Despite observed correlations with restatement magnitude, it is important to note that litigation risk and executive turnover have been found to be primarily a function of irregularities rather than financial magnitude (Hennes et al., Citation2008). Thus, the primary risks associated directly with the financial magnitude of a restatement are decreased market value and firm failure.

Managers primarily concerned about negative market reactions will likely choose higher levels of transparency for a couple of reasons. Firstly, as in the case of irregularities, managers and accountants facing particularly large restatements are likely to be motivated to reduce uncertainty and reaffirm managers’ commitment to integrity by providing high transparency in the restatement announcement. Secondly, evidence suggests that investors underreact to single news items but overreact to a series of good or bad news (Barberis et al., Citation1998). This suggests that managers may be able to minimize negative market reactions by divulging all of the bad news at once rather than risking having it trickle out over time. Consistent with accounting’s “big-bath” hypothesis, these firms are likely to get all of the bad news out at once in order to avoid additional negative announcements.

Hypothesis 2: There will be a positive relationship between the financial magnitude of the restatement and the transparency of the restatement announcement.

3.2. Organizational factors

3.2.1. Firm size

For some managers, the risk of firm failure resulting from the restatement may be more salient than concerns about decreased share price. One study found that of a sample of 405 restatements between 1995 and 1999, 146 restating firms failed within 255 days of the restatement announcement (Hirschey et al., Citation2005). This study also found that smaller firms were particularly susceptible to post-restatement failure. Thus, firm size may serve as a proxy for perceived risk of failure following a restatement. Managers concerned with firm failure are likely to be reluctant to divulge bad news. These managers may believe that the firm will not survive the initial negative market reaction associated with transparently divulging details of the restatement. The fear of firm failure may trigger risk aversion amongst managers making them less likely to transparently report information about the restatement. Essentially, these firms cannot afford to take a “big bath”. Thus, for smaller firms, we anticipate a negative relationship between transparency and the magnitude of the restatement.

Hypothesis 3: Among relatively small firms, there will be a negative relationship between the financial magnitude of the restatement and the transparency of the restatement announcement.

3.2.2. Stakeholder orientation

It is likely that a stakeholder orientation—indicated by a relational or collectivistic identity orientation and a commitment to CSP—will moderate the relationship between restatement magnitude and the transparency of the restatement announcement. Previous research has shown that firms wishing to repair their reputations following a restatement may engage in a variety of reputation-building behaviors aimed at various stakeholder groups (Chakravarthy et al., Citation2014). Firms with strong stakeholder orientations are likely to perceive restatements as threats to valued relationships. This threat is present because a restatement suggests that the firm lacks the competence or integrity to provide reliable financial disclosures (Gomulya & Mishina, Citation2017). This threat is based on the principle that an integrity or competence-based trust violation has occurred, and the extent of this threat is not solely dependent on the financial magnitude of the restatement. In order to rebuild trust, firms with stakeholder orientations are likely to transparently disclose information in order to provide information about the trust-violation and to reassert their trustworthiness. Because firms with a stakeholder orientation are motivated to be transparent in order to move more quickly through the process of rebuilding relationships and regaining trust and because the extent of the threat is based on principle rather than the restatement’s magnitude, it is likely that the amount of information provided by firms with strong stakeholder orientations will be impacted less by the financial magnitude of the restatement, as compared to firms lacking a stakeholder orientation.

Firms that do not have a strong stakeholder orientation are more likely to view the restatement as a financial threat, and the extent of the perceived threat is likely to be highly related to the financial magnitude of the restatement. Thus, firms that lack a stakeholder orientation are likely to alter the transparency of their restatement announcements based on the financial magnitude of the restatement. When the magnitude of the restatement is comparatively smaller, managers of firms which lack a stakeholder orientation may perceive little need for transparency about the restatement. When the magnitude of restatement is greater, these firms are likely to recognize the threats posed by uncertainty following a large restatement and should be increasingly transparent in order to reduce uncertainty and minimize the inevitable, negative market reactions. In sum, the positive relationship between the magnitude of the restatement and the transparency of the restatement announcement is predicted to be weaker for firms that have strong stakeholder orientations than for firms which do not. In this study, stakeholder orientation is operationalized using indicators of a relational or collectivistic identity orientation and corporate social performance (CSP) leading to the following two-part hypothesis.

Hypothesis 4: The positive relationship between the magnitude of the restatement and the transparency of the restatement announcement will be weaker for firms which have: a) strong relational/collectivistic identity orientations than for firms which do not and b) for firms which have strong records for corporate social performance than for firms with weak CSP records.

4. Method

The hypothesized relationships are studied using a sample of restatement events from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) dataset. This dataset includes accounting restatements from 1997 through 30 June 2006. The GAO identified these restatements by searching the Lexis Nexis database for press releases or other media coverage using search terms such as “restate” and “restatement.” Once a restatement was identified, additional information was collected so that the restatement could be classified into one of nine categories. The GAO specifically worked to exclude restatements that were caused by routine accounting issues and instead focused on “…restatements resulting from accounting irregularities, including so-called ‘aggressive’ accounting practices, intentional or unintentional misuse of facts applied to financial statements, oversight or misinterpretation of accounting rules, and fraud,” (GAO, Citation2003, p. 4).

The initial sample of restatements from the GAO dataset for which KLD data (used to measure CSP) is also available includes 300 restatements from 204 companies (some companies had more than one restatement in the dataset). Of these, 67 annual reports could not be coded either because the reports were not available because the company had delayed filing or because the narrative business descriptions did not include any indications of organizational identity orientation. Additional data needed for the study was not available for another 90 restatement events leaving a final sample of 123 restatements with all of the data necessary for inclusion in regression analyses. The companies excluded from the final sample were compared to the companies in the sample in terms of industry, revenue, net income, and number of outstanding shares, and no significant differences were discovered. The companies in the final sample spanned 31 different 2-digit SIC codes and 59 different 4-digit SIC codes providing broad representation of different industries. Additionally, because the GAO dataset spanned time periods before and after the passage and implementation of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, restatements from both time periods were compared. No systematic variations between time periods were present within this sample for any of the variables included in the study.

4.1. Measures

4.1.1. Irregularities and errors

Each restatement was classified as either an irregularity or an error using a dataset developed and validated by Hennes et al. (Citation2008). These authors classified the restatements in the GAO dataset as irregularities if they explicitly use variants of the words “irregularity” or “fraud”, involve related SEC or DoJ investigations, or if they involve related independent investigations. Irregularities received a dummy-code of 1 and errors 0.

4.1.2. Restatement magnitude and direction

The magnitude of the restatement represents the monetary impact on a firm’s financial results. The direction of the restatement indicates whether the impact on financial results was positive or negative. The magnitude of the restatement is measured by dividing the absolute value of the dollar amount of the restatement by the absolute value of the firm’s annual net income/loss. Absolute values were used so that negative restatements would not be treated analytically as smaller than positive restatements. For firms that were restating multiple periods, the cumulative impact of the restatement is used. Dividing the amount of the restatement by each firm’s net income/loss provides a measure of the magnitude of the restatement that is relative to the size and profitability of each firm. This is important because a restatement of $20 million, for example, would have a much greater impact on a company with a net income of $50 million than it would for a firm with net income of $5 billion. Additionally, it was important to measure the magnitude of the restatement in terms of net income rather than revenue for a couple of reasons. First, some restatements impact revenue reporting while others impact cost reporting or other items on a firm’s financial statements, but each of these types of restatements ultimately affects the firm’s bottom line. Second, it is this impact on net earnings (and in turn earnings per share) that is of most concern to investors. The absolute values of the restatements ranged from $0 to $3 billion. Magnitude of the restatement (as a proportion of net income/loss) ranged from 0 to 550 with a mean of 5.25 (SD = 49.598).

The direction of the restatement was dummy-coded with 0 representing a positive restatement and 1 representing a negative restatement. Net income and revenue (used to control for firm size) for each of the firm years in the sample was gathered from the Compustat dataset accessed through Wharton Research Database Services (WRDS).

4.1.3. Organizational identity orientation

Organizational identity orientation was coded by analyzing the annual (10K) reports of the firms in the sample using a technique developed for this study and based on the codebook Brickson developed in her initial study of OIO (Brickson, Citation2005). The coding involved evaluating the narrative portions of the 10K—including the Business Strategy or Overview section as well as the Risk Factors (when provided)—in order to discover company activities, values, and linguistic nuances which reveal the organization’s identity orientation. The coded portions of the annual reports in the sample ranged from 1–86 pages in length and took between 10 minutes and eight hours to code. The number of OIO codes in the useable sample of 10Ks ranged from 2 to 54. The primary researcher coded each annual report for statements indicating individualistic, relational, and collectivistic identity orientations. Codes were assigned whenever a company used rhetoric indicating one of the identity orientations or whenever the 10K described activities that would be indicative of any of the three identity orientations. Thus, each 10K could have multiple codes for one or more of the identity orientations. The aggregate number of codes for each identity orientation was used as the primary measure of identity orieity orientation. This measurement technique is based on the assumption that the more times a company expresses an identity orientation, the more central and important that identity orientation is. This coding yielded scores for individual, relational, and collectivistic identity orientations for each company. Because relational and collectivistic orientations can both be viewed as indications of a stakeholder orientation these categories were aggregated. Table provides a brief summary of some of the indicators used to code OIO in 10Ks.

Table 1. Conceptual Indications of Organizational Identity Orientation

The validity and the reliability of the coding technique were tested. In order to assess the reliability of the coding procedure a second rater, hired for this purpose, coded a sub-sample of 64 10Ks from the study. The rater was first trained using several annual reports that were not part of the sample used in the study. Training was an iterative process that first involved simultaneously coding two annual reports while discussing the reasons for the codes throughout the process. Next both raters (the researcher and the hired rater) coded two annual reports independently, and then compared and discussed the statements each had coded. This process was repeated a second time. Finally, the two raters coded three 10Ks independently, and the coding of the hired rater was compared to that of the researcher. After achieving a high level of agreement during the training process, the rater was given annual reports from the sample of restating firms to code independently. The correlations between the two raters were 0.689 (p < 0.01) and 0.623 (p < 0.01), respectively, for the individualistic and relational/collectivistic identity orientations based on number of codes for each orientation. Comparisons between the two were discussed in order to achieve agreement on final codes.

Prior to conducting the main study, a study was conducted to test the validity of the annual report-based measure of organizational identity orientation (OIO). For this study, Brickson’s (Citation2005) survey measure of organizational identity orientation was sent to 100 individuals working in 10 different companies. Thirty-three completed surveys were returned for a response rate of 33%. Of these, three responses from individuals in two different firms could not be used because a minimum of three responses per company was required. Thus, thirty responses (30% response rate) from individuals in seven different companies were retained for analysis. The firms included in this study include three food manufacturers, two trucking/logistics companies, one retailer, and one financial services company.

Survey responses were evaluated using Brickson’s coding scheme for OIO. Responses to each item were coded as individualistic, relational, or collectivistic when they used terms or expressed ideas consistent with those in Brickson’s coding scheme. In order to evaluate the agreement between the survey-based measure and the 10K measure of OIO, the total number of relational and collectivistic codes in each response were aggregated and then divided by the total number of OIO indicators. Next, the proportion of relational and collectivistic responses to total number of indicators was averaged across the survey respondents and this number was compared to the proportion of relational and collectivistic indicators to total indicators in the 10K.

Organizational identity orientation categories were defined using 0.33 and 0.66 cut-offs with values less than 0.33 indicating an individualistic OIO, values between 0.33 and 0.66 indicating a hybrid OIO, and values greater than 0.66 indicating a relational/collectivistic OIO. Based on these cut-offs, five of the seven firms (71.4%) showed agreement between the survey measure of OIO and the 10K measure. Of the two firms that did not show categorical agreement between the survey measure and the 10K measure, one also showed very poor agreement between the 4 survey respondents. For this company, the respondents’ values for the proportion of relational/collectivistic indicators to total OIO indicators were 0.00 (purely individualistic), 0.44 (hybrid), 0.67 (borderline hybrid & relational/collectivistic), and 0.75 (relational/collectivistic). Thus, the survey measure of OIO is inconclusive for this firm. Overall, results of this study provide positive indications for the validity of the 10K measure of OIO.

4.1.4. Corporate social performance

Corporate social performance was measured using data from the Environment, Social, & Governance (ESG) dataset of Corporate Social Performance (historically and commonly referred to as the Kinder, Lydenberg, & Domini (KLD) dataset) by MSCI—a large provider of analytic data and investment decision support tools—retrieved through WRDS. The KLD ratings are based on the observable outcomes (performance) that reflect the company’s commitment to social responsibility as embodied in the processes, policies, and programs of the firm. Although there has been some discussion in the literature about the best way to employ the KLD data (e.g., Mattingly & Berman, Citation2006; Slater & Dixon-Fowler, Citation2009), the ratings themselves are generally considered to be among the most comprehensive, objective, and valid measures available for studying CSP (Mattingly & Berman, Citation2006). For this study, CSP was measured as Net CSP (CSP Strengths—CSP Weaknesses). For this sample, CSP Strengths ranged from 0 to 9 with a mean of 1.69 (SD 1.91); CSP Weaknesses ranged from 0 to 8 with a mean of 2.22 (SD 2.01); Net CSP ranged from −7 to 7 with a mean of −0.53 (SD 2.46).

4.1.5. Transparency of restatement announcement

The transparency of the restatement announcements was measured by counting the number of pieces of information related to the restatement which were included in the press release in which the restatement was first mentioned. Press releases were pulled from the Lexis Nexis database. The GAO also used Lexis Nexis to compile the restatement dataset, and the dates of the restatement announcements are included in the GAO data. These dates were used to ensure that the initial press release relating to the restatement was used in this analysis. Preliminary analysis found there were ten possible types of information about the restatement that might be included. The possible pieces of information were: 1) the amount of the restatement, 2) the impact on earnings per share, 3) the direction (±) of the restatement, 4) the initiating party, 5) the type(s) of account(s) affected by the restatement, 6) information about remediation efforts by the company, 7) a quote from a board member or top manager related to the restatement, 8) the periods being restated, 9) the impact on debt covenants, and 10) other information related to the restatement. The number of pieces of information provided in the observed data ranged from zero to ten with a mean of 5.16 (SD = 1.74) and was normally distributed (skewness = 0.047; kurtosis = 0.366).

5. Analysis and results

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for the variables included in this study are presented in Table . Consistent with hypotheses 1 and 2, irregularities and restatement magnitude are both significantly and positively correlated with transparency. It is also worth noting that there is a significant, positive correlation between the two indicators of stakeholder orientation—a relational/collectivistic OIO and CSP. There is also a significant, positive relationship between individualistic and relational/collectivistic OIO indicating the presence of firms with hybrid identity orientations in the sample.

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations

Hypotheses were tested using hierarchical linear regression is SPSS. Results of the analysis are presented in Table . In the first step of the analysis, transparency is regressed on irregularity and restatement magnitude while controlling for revenue (an indicator of firm size), net income, and restatement direction (±). The R2 for this model is significant (R2 = 0.112, p < 0.05). The second stage includes individualistic OIO, relational/collectivistic OIO, and CSP in the model. Although main effects were not predicted for these variables it is important to control for them prior to entering the interaction variables in the third stage. The change in R2 for model 2 is not significant, but the change in R2 for model 3 is (ΔR2 = 0.066, p < 0.05).

Table 3. Regression Results for transparency of restatement announcement

Hypothesis 1 predicted that restatement announcements related to irregularities would be more transparent than those related to errors. The significant, positive relationship observed between irregularities and transparency (β = 0.848, p < 0.05)Footnote1 provides support for this hypothesis. Hypothesis 2 predicted that, in general, transparency would be positively related to the magnitude of the restatement. The positive relationship between magnitude and transparency observed in model 1 (β = 0.008, p < 0.05) provides support for hypothesis 2.

Post-hoc analyses were conducted to explore differences in transparency following errors versus irregularities. The sample was split so that errors (n = 76) and irregularities (n = 47) could be analyzed separately. In these analyses, only Model 1 (including Revenue, Net Income, Restatement Direction, and Restatement Magnitude) was significant in the sample of errors (R2 = 0.131, F = 2.677, p < 0.05) and approached significance in the sample of irregularities (R2 = 0.184, F = 2.372, p = 0.068). The results of these analyses are presented in Table .

Table 4. Regression results for transparency among errors and irregularities

Contrary to what we find for the full sample, within the sample of errors, magnitude of the restatement is negatively related to transparency. This provides evidence that when facing an error-based restatement, managers are most likely to be concerned about negative market reactions as opposed to the concerns about investigations and litigation expected for irregularities. Thus, as the magnitude of an error-based restatement becomes larger, managers may believe that increased transparency about the event will lead investors and others to perceive the restatement as a bigger problem than it really is. Within the sample of errors, we also observe a positive relationship between profitability and transparency. This suggests that firms which are on more solid financial footing are more willing to risk the initial negative market reaction that may follow transparent disclosure of details about the restatement. This finding is in line with the rationale for hypothesis 3 which suggests that the perceived risk of firm failure will lead to decreased transparency. Because the model for the sample of irregularities did not reach significance, relationships within the model must be viewed with caution, but it is worth noting that among irregularities we do observe a positive significant relationship between transparency and restatement magnitude very similar to what was observed in the full sample.

Hypothesis 3 predicted that for relatively small firms the relationship between transparency and restatement magnitude would be negative due to increased concerns about the firm’s post-restatement survival. In order to test this hypothesis, a second regression was run after selecting only those firms with revenue below the median ($3,148,340,500) for the sample. Results of this analysis are presented in Table . For these smaller firms (n = 65) the relationship between transparency and restatement magnitude is negative and significant (β = −0.158, p < 0.05) providing support for hypothesis 3. Additionally, within this subsample, the bivariate correlation between transparency and restatement magnitude is −0.267 (p < 0.05). In order to test the robustness of this result, additional tests were run using cutoffs of $1, 2, 3, and 4 billion in revenue. The relationship between transparency and magnitude remained negative and significant for all subsamples using a cut-off below the median revenue. At the $4 billion revenue cutoff, the relationship between transparency and magnitude became positive and significant (β = 0.008, p < 0.05) providing further evidence that the relationship between transparency and restatement magnitude is different for smaller firms than for larger firms.

Table 5. Regression results for transparency of restatement announcement among small firms

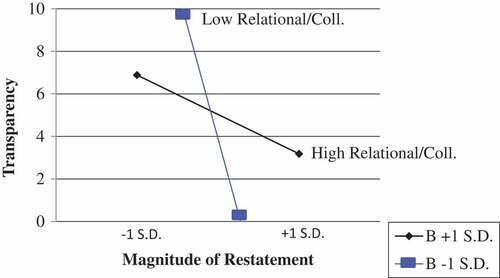

Hypothesis 4a predicted that the relationship between transparency and restatement magnitude would be weaker for firms with strong relational or collectivistic identity orientations than for firms without such orientations. Results from model 3 of the full sample regression (Table ) indicate a significant positive interaction between restatement magnitude and relational/collectivistic OIO (β = 0.018, p < 0.01). A plot of this interaction is presented in Figure . As predicted, the relationship between transparency and restatement magnitude is weaker for firms with high (+1 SD) relational/collectivistic OIOs than for firms with weak (−1 SD) relational/collectivistic orientations. Hypothesis 4b predicted that the relationship between transparency and restatement magnitude would be weaker for firms with strong CSP records than for those with weak CSP records. Results of the analysis do not support this hypothesis.

6. Discussion

This study was designed to explore the relationships between situational and organizational characteristics and transparency regarding financial restatements. Analyzing a sample of restatement events, we find that the severity of the restatement influences transparency such that, in general, transparency increases as the severity increases. We also find that organizational characteristics moderate the relationship between situational factors and transparency. Specifically, we find that among smaller firms transparency actually decreases as the financial magnitude of a restatement increases. We theorize that this is a result of smaller firms’ increased risk of failure following large restatements. Finally, we find that the link between restatement magnitude and transparency is weaker for firms with a strong relational or collectivistic identity orientation than for firms without such an identity orientation. Interestingly, this interaction was not observed among firms with high corporate social performance although both relational/collectivistic identity orientation and CSP are viewed as indicators of a firm’s stakeholder orientation.

The positive relationships observed between restatement severity (irregularities and magnitude) are in line with theories (e.g., Gertsen et al., Citation2006; Pfarrer et al., Citation2008a) which suggest that the provision of information following an organizational transgression is an important step in protecting reputational assets and repairing relationships and reintegrating with stakeholders. Based on this rationale, one would expect transparency about a negative event to scale according to the size of the threat posed by the event. In general, larger restatements and those based on accounting irregularities represent greater threats than smaller restatements and those caused by errors, and the results of this study indicate that transparency is indeed positively related to these situational characteristics.

Organizational characteristics, including firm size and stakeholder orientation, are predicted to influence the manner in which the threat posed by a restatement is interpreted within a firm and that this will influence transparency regarding the restatement. Managers of smaller firms are expected to be more likely to perceive a restatement as a threat to their companies’ survival, and the fear of a drastic initial market reaction and firm failure will lead to a negative relationship between restatement magnitude and transparency among small firms. Results confirm this prediction. Additional evidence of the impact of fear of firm failure on transparency may be inferred from the positive relationship between profitability and transparency observed in the subsample of error-based restatements. Because errors are unlikely to lead to investigations and litigation, managers are likely to perceive a negative market reaction as the primary threat posed by such an event. The positive relationship observed between net income and transparency within the sample of errors suggests that firms which are less financially stable are less willing to disclose information about an error-based restatement.

Firms which have stronger stakeholder orientations—indicated by relational/collectivistic identity orientation and corporate social performance—are predicted to view the threat posed by a restatement as a threat to valued relationships with stakeholders whereas firms without a stakeholder orientation will view the restatement solely as a financial threat. Thus, the relationship between restatement magnitude and transparency is expected to be weaker for firms with relational or collectivistic identity orientations and for firms with strong social performance. Results show evidence of this interactive relationship for organizational identity orientation but not for corporate social performance. It is possible that OIO is a better indicator of stakeholder orientation than CSP. Organizational identity orientation is explicitly defined as “the nature of assumed relationships between an organization and its stakeholders” (Brickson, Citation2005, p. 577) whereas CSP can be the result of instrumental motives, genuine concern for stakeholders, or some combination of the two. Overall, the variance in transparency as a function of restatement magnitude is smaller among firms with a strong relational or collectivistic identity orientation than among those lacking such an orientation.

6.1. Managerial implications

Both research and anecdotal evidence suggest that financial restatements can have an important impact on managers’ reputations and careers (e.g., Gangloff, Connelly, & Shook, Citation2016). Thus, managers have an important stake in understanding factors that influence responses to restatements. Although many firms facing restatements replace top executives—particularly the CEO or CFO—as a means of signaling a desire to improve reporting quality (Gangloff et al., Citation2016), research shows that restating firms can also rebuild trust and improve market reactions by other means. Lungeanu and colleagues (Citation2018) found that top executives of restating firms can improve their own reputations and that of their firms by joining boards of trustees of nonprofit foundations. Overall, previous research suggests that restating firms can repair reputational damage through transparent interactions and by building or strengthening relationships with various stakeholder groups (Chakravarthy et al., Citation2014; Lungeanu et al., Citation2018).

Results of this study provide evidence that managers facing particularly serious restatement events—large restatements and those caused by irregularities—generally seem to heed the prescriptions of theories which suggest that reputational damage can be minimized, and reintegration with stakeholders hastened, by providing thorough and transparent information about a negative event. Increased transparency following severe restatements likely allows firms to more quickly rebuild relationships and regain market value following the restatement. Additionally, increased transparency in the case of irregularities reduces the likelihood that additional negative information will be revealed during investigations and litigation, and may even encourage regulators and adjudicators to take a less punitive stance.

While the generally positive relationship between restatement severity and transparency observed in this study is encouraging, the evidence that among those firms which are potentially vulnerable to failure, transparency diminishes as the magnitude of the restatement increases is concerning. Among small firms, the relationship between irregularities and transparency is positive and significant, but the relationship between restatement magnitude and transparency is negative and significant. This suggests that these managers may feel compelled to be more transparent when facing irregularities as opposed to errors, but that they also become less willing to share information as the financial magnitude of the restatement increases. The positive relationship between profitability and transparency when restatements are due to errors further suggests that discretionary transparency decreases when firms are more vulnerable to failure. If managers perceive a restatement and anticipated negative market reactions as threats to firm survival, they are likely to be more concerned with minimizing the initial negative reaction than with hastening the restoration of relationships and market value following that reaction. After all, if the firm does not survive the initial fallout from the restatement, there will be no reason to worry about the recovery period.

While the perceived risk of firm failure seems to lead to decreased transparency, it is not clear whether decreased transparency helps or harms a firm’s survival odds. Previous research has observed that small firms are more likely to fail following a restatement than large firms, and we observe that the transparency of small firms’ restatement announcement decreases as the magnitude increases. We theorize that the fear of firm failure is the cause for decreased transparency, but it is also possible that reduced transparency actually increases the risk of failure. This possibility is suggested by theories which suggest that transparency not only speeds recovery after a transgression, but also helps minimize the initial loss of reputation and value. Managers who are worried about the risk of firm failure following a restatement may need to make special efforts to ensure transparency and should also prioritize building and strengthening stakeholder relationships in order to increase the odds of firm survival.

While this research focuses on transparency following a restatement, it is clearly ideal for firms to avoid damaging misstatements in the first place. In this regard it is worth noting that previous research has shown that managerial choices can impact financial reporting quality and the likelihood of restatements (Dechow et al., Citation2011). Managers often use a variety of earnings management and discretionary accounting tactics to hide diminishing returns. While hiding poor performance may be tempting in the short run, these practices increase the likelihood of a future restatement (Dechow et al., Citation2011). Research has also found that human resource management policies and employee relations can impact financial reporting quality, the quality of internal accounting controls, and the likelihood of restatements (Garrett, Hoitash, & Prawitt, Citation2014; Guo, Huang, Zhang, & Zhou, Citation2016). Thus, managers should resist the temptation to engage in accounting tactics designed to hide diminishing performance and should work to develop and maintain positive employee relations in order to reduce the likelihood of financial restatements. If a restatement does occur, managers should report it transparently and work to improve relationships with both internal and external stakeholders.

6.2. Stakeholder implications

While this study provides some insight and guidance for managers, the implications for investors and other stakeholders are also important. When a restatement occurs, managers are likely to have access to inside information about the situation, while investors’ and other external stakeholders’ access to information is largely at the mercy of managers. Thus, investors, analysts, regulators, and other stakeholders are likely to be quite interested in understanding factors which predict a firm’s transparency regarding a restatement. This study also demonstrates that archival data can be used to gain insight into some of the characteristics which may influence a company’s transparency following a restatement. This means that external parties, such as regulators and analysts, can use publicly available documents to gain insight into factors which may indicate which companies will be more or less transparent.

Firms with strong relational and collectivistic identity orientations appear to be motivated by a principled recognition of the value of transparency and a desire to repair trust and restore relationships following a restatement. For these firms, the threat a restatement poses to valued relationships may be as important as the financial threat. Thus, these firms exhibit less variation in transparency across levels of restatement magnitude than firms without a relational or collectivistic orientation. Additionally, when responding to high magnitude restatements, firms with relational and collectivistic orientations are more transparent than their counterparts. It is likely that these firms are especially motivated to repair relationships with stakeholders and recognize that transparent disclosure about the restatement is a critical step in rebuilding trust.

The more transparent a firm is about a restatement, the better able analysts and investors will be at determining the appropriate response to the news. Additionally, firms which provide more information immediately following a restatement may be able to limit reputational damage and reduce the overall negative impact of the restatement (Akhigbe et al., Citation2005; Chakravarthy et al., Citation2014; Gertsen et al., Citation2006). By understanding which firms may be predisposed to be more or less transparent under various circumstances, regulators, analysts, and investors may be better able to direct their monitoring efforts and energy toward those firms which are less likely to be transparent following a restatement. In particular, these stakeholders may wish to invest more energy in monitoring the activities and financial statements of companies which do not show evidence of a relational or collectivistic organizational identity orientation. Research has shown that evidence of earnings manipulation can often be discovered long before companies announce a formal restatement (Ettredge, Scholz, Smith, & Sun, Citation2010) and that employee relations can be important predictors of financial reporting quality and restatements (Garrett et al., Citation2014; Guo et al., Citation2016). Thus, monitoring may expose problems well before a company announces a restatement.

6.3. Theoretical implications

This study provides initial evidence that organizational characteristics can indeed influence transparency regarding restatements. Previous research has focused primarily on trends relating to financial restatements (e.g., Alali & I-Ling Wang, Citation2017), predictors of restatements (e.g., Dechow et al., Citation2011; Guo et al., Citation2016) and market and stakeholder reactions to restatements (e.g., Palmrose et al., Citation2004; Ye & Yu, Citation2017). The research presented here provides valuable insights into ways situational and organizational characteristics influence firms’ responses following a restatement. The results of this study suggest that some organizations may be predisposed to being more or less transparent following a restatement. This is a valuable insight for researchers because it suggests that it might be possible to develop theoretically based predictive models of firm transparency in restatements. The current study draws on theories of stakeholder orientation and risk aversion to predict transparency following restatements, but it is possible that additional factors may also play a role. These findings suggest that future research into which organizational characteristics relate to transparency in restatements could further aid our understanding of why organizations respond the way they do following a restatement and allow us to predict how transparent a particular organization will be when facing a restatement. Such research will may also allow managers to understand the predispositions their organizations have in responding to restatements and to design processes which will help their company avoid responses which could further damage the company’s credibility, reputation, or performance.

While the current study focuses on transparency following restatements, it is possible that stakeholder orientation or other organizational factors may also predict transparency following other types of negative events. Restatements are certainly not the only type of event that can damage a firm’s reputation and market value. Firms can face product safety issues and recalls, allegations of discrimination, links to environmental harm, and many other types of negative events, and firms’ reactions to these events may also be related to stakeholder orientation or other organizational characteristics. Theory suggests that firms facing various types of negative events can speed reintegration with stakeholders and reputation repair by openly disclosing information about these events sooner rather than later (Pfarrer et al., Citation2008a), but previous research has not explored whether certain organizations may be predisposed to be more or less forthcoming following such events. Nonetheless, it is possible that firms with a relational or collectivistic OIO may be more motivated to work to maintain and repair relationships following transgressions than their more individualistic counterparts.

This study also extends the literature regarding organizational identity orientation by developing a measure of OIO which can be applied to a wide variety of firms and by providing evidence that OIO can, in fact, impact organizational responses to ethical issues. Previous research has suggested that aspects of organizational identity will impact many facets of organizational activity but few studies have been able to test these assertions. The measure of OIO developed for this study applies qualitative textual analysis to archival documents and may open the door to a variety of research treating OIO as an outcome, an antecedent, or even a moderating variable. The ability to measure organizational identity orientation through archival documents is particularly useful because it is an aspect of organizational identity which can be compared across firms of various sizes and structures from a variety of industries.

6.4. Limitations and directions for future research

This study makes important contributions to our understanding of factors which impact transparency in financial restatements. Both the findings of this study and its inherent limitations offer fruitful avenues for future research in this area. First, the theory and predictions developed in this study are largely based on the assumption that managers are aware of the potential outcomes associated with financial restatements and that they are motivated to protect their firms from the most severe negative outcomes—including loss of market value, legal and regulatory sanctions, and firm failure. While existing research suggests that this is a reasonable assumption, future qualitative research could further investigate the motivations and decision processes of managers faced with announcing restatements.

The measure of OIO developed for this study provides a valuable tool for studying a key aspect of organizational identity using archival records, nonetheless, the use of hand-coding is time consuming. While this method was appropriate given the importance of contextual nuance in this measure, this measure could be made more efficient through future work designed to apply increasingly sophisticated computer assisted textual analysis techniques based on the coding system used here. A more efficient means of coding annual reports and other statements from a firm for OIO would make it easier for researchers and analysts to measure this aspect of firms’ organizational identities and could lead to additional research related to the antecedents and consequences associated with OIO. One interesting avenue for future research would be to explore whether firms with a relational or collectivistic OIO are less likely to face restatements than their individualistic counterparts. Some existing research suggests this might be the case. Specifically, research has found a positive relationship between country-level individualism and stock price crash risk (An, Chen, Li, & Xing, Citation2018). Coupled with research suggesting that better employee relationships lead to higher quality financial reporting and reduced restatement risk (Garrett et al., Citation2014) a case might be built suggesting that a relational or collectivistic OIO could be associated with a reduced likelihood of financial restatements.

This study was based on a sample of firms who mentioned restatements in a press release, but previous research has found that some firms restate under the radar—mentioning the restatement only in a future financial disclosure or an amended filing not accompanied by a press release. While studying press releases provided a variable measure of how much information managers shared about the restatement, the range of transparency in this study did not capture those firms who are the very least transparent regarding restatements. Future research should test whether the predictions here continue to apply when the range of transparency is expanded to include these most secretive of restating firms.

Finally, while this study provides some information about which companies are more or less likely to be transparent when announcing a restatement, it does not address what types of measures might encourage managers to be more transparent. Future research should further examine whether greater transparency increases or decreases the risk of firm failure following a restatement and explore the viability of various interventions designed to increase transparency.

7. Conclusion

In conclusion, this research provides valuable new insights into the situational and organizational influences on transparency about restatements. We find a generally positive relationship between restatement severity and transparency suggesting that firms facing particularly damaging restatements demonstrate a desire to quickly resolve the situation and rebuild their firms’ reputations and market value. Interestingly, we find that this relationship does not hold amongst smaller firms who may worry that their firm will not survive following the restatement. We also find that companies with an individualistic identity orientation tend to scale their transparency according to the financial magnitude of the restatement while firms with relational or collectivistic orientations exhibit similar levels of transparency regardless of a restatements magnitude. We hope that this study will stimulate additional research into predictors of transparency regarding restatements as well as transparency regarding negative events more generally.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

A. J. Guerber

A. J. Guerber received a Ph.D in Business Administration – Management from the University of Arkansas. Her research interests include organizational ethics, corporate communications, and stakeholder management. A.J. teaches Business Ethics and Strategy at the undergraduate and graduate levels at West Texas A & M University in 2016 and has served as an organizer of the Sustainability, Ethics & Entrepreneurship (SEE) conference since 2012. She has published research in the Journal of Managerial Issues and Crime and Corruption in Organizations.

Vikas Anand

Vikas Anand earned a Ph.D. from Arizona State University, an MBA in International Business from the Indian Institute of Foreign Trade, and a Bachelor’s in Engineering and Master’s in Physics from Birla Institute of Technology. His research explores organizational corruption, organizational identity, and knowledge and information management. He has published in several outlets such as the Academy of Management Review, Research in Organizational Behavior, Organization Science, and Academy of Management Executive.

Notes

1. All coefficients reported are unstandardized.

References

- Akhigbe, A., Kudla, R. J., & Madura, J. (2005). Why are some corporate earnings restatements more damaging? Applied Financial Economics, 15, 327–22. doi:10.1080/0960310042000338722

- Alali, F., & I-Ling Wang, S. (2017). Characteristics of financial restatements and frauds: An analysis of corporate reporting quality from 2000–2014. CPA Journal, 87(11), 32–41.

- An, Z., Chen, Z., Li, D., & Xing, L. (2018). Individualism and stock price crash risk. Journal of International Business Studies, 49(9), 1208–1236. doi:10.1057/s41267-018-0150-z

- Arthaud-Day, M. L., Certo, S. T., Dalton, C. M. D., & Dalton, D. R. (2006). A changing of the gaurd: Executive and director turnover following corporate financial restatements. Academy of Management Journal, 49(6), 1119–1136. doi:10.5465/amj.2006.23478165

- Barberis, N., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1998). A model of investor sentiment. Journal of Financial Economics, 49, 307–343. doi:10.1016/S0304-405X(98)00027-0

- Bartlett, J., McDonald, P., & Pini, B. (2015). Identity orientation and stakeholder engagement-the corporatisation of elite schools. Journal of Public Affairs (14723891), 15(2), 201–209. doi:10.1002/pa.1510

- Brickson, S. L. (2005). Organizational identity orientation: Forging a link between organizational identity and organizations‘ relations with stakeholders. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(4), 576–609. doi:10.2189/asqu.50.4.576

- Brickson, S. L. (2007). Organizational identity orientation: The genesis of the role of the firm and distinct forms of social value. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 864–888. doi:10.5465/amr.2007.25275679

- Bushman, R. M., Piotroski, J. D., & Smith, A. J. (2004). What determines corporate transparency? Journal of Accounting Research, 42(2), 207–251. doi:10.1111/j.1475-679X.2004.00136.x

- Campbell, J. T., Eden, L., & Miller, S. R. (2012). Multinationals and corporate social resposnibility in host countries: Does distance matter? Journal of International Business Studies, 43(1), 84–106. doi:10.1057/jibs.2011.45

- Chakravarthy, J., de Haan, E., & Rajgopal, S. (2014). Reputation repair after a serious restatement. Accounting Review, 89(4), 1329–1363. doi:10.2308/accr-50716

- Coombs, W. T. (2006). The protective powers of crisis response strategies: Managing reputational assets during a crisis. Journal of Promotion Management, 12, 241–260. doi:10.1300/J057v12n03_13

- Coombs, W. T. (2007). Protecting organization reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corporate Reputation Review, 10(3), 163–176. doi:10.1057/palgrave.crr.1550049

- Crilly, D. (2011). Cognitive scope of the firm: Explaining stakeholder orientation from the inside-out. Business & Society, 50(3), 518–530. doi:10.1177/0007650311405950

- DeBoskey, D. G., & Gillett, P. R. (2013). The impact of multi-dimensional corporate transparency on US firms’ credit ratings and cost of capital. Review of Quantitative Finance & Accounting, 40, 101–134. doi:10.1007/s11156-011-0266-8

- Dechow, P. M., Ge, W., Larson, C. R., & Sloan, R. G. (2011). Predicting material accounting misstatements. Contemporary Accounting Research, 28(1), 17–82. doi:10.1111/j.1911-3846.2010.01041.x

- Ettredge, M., Scholz, S., Smith, K. R., & Sun, L. (2010). How do restatements begin? Evidence of earnings management preceding restated financial reports. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 37(3/4), 332–355. doi: 10.1111/jbfa.2010.37.issue-3-4

- Files, R., Swanson, E. P., & Tse, S. (2009). Stealth disclosure of accounting restatements. The Accounting Review, 84(5), 1495–1520. doi:10.2308/accr.2009.84.5.1495

- Gangloff, K. A., Connelly, B. L., & Shook, C. L. (2016). Of Scapegoats and Signals. Journal of Management, 42(6), 1614–1634. doi:10.1177/0149206313515521

- GAO. (2003). Financial Statement Restatement Database. Report to the Ranking Minority Member, Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, US Senate GAO-03-395R.

- GAO. (2006). Financial Restatements: Update pf Public Company Trends, Market Impacts, and Regulatory Enforcement Activities. report to the Ranking Minority Member, Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, US Senate GAO-06-678.

- Garrett, D. E., Bradford, J. L., Meyers, R. A., & Becker, J. (1989). Issues management and organizational accounts: An analysis of corporate responses to accusations of unethical business practices. Journal of Business Ethics, 8, 507–520. doi:10.1007/BF00382927

- Garrett, J., Hoitash, R., & Prawitt, D. F. (2014). Trust and financial reporting quality. Journal of Accounting Research, 52(5), 1087–1125. doi:10.1111/1475-679X.12063

- Gertsen, F. H. M., Riel, C. B. M., & Berens, G. (2006). Avoiding repuation damage in financial restatements. Long Range Planning, 39, 429–456. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2006.09.002

- Gomulya, D., & Mishina, Y. (2017). Signaler credibility, signal susceptibility, and relative reliance on signals: How stakeholders change their evaluative processes after violation of expectations and rehabilitative efforts. Academy of Management Journal, 60(2), 554–583. doi:10.5465/amj.2014.1041

- Gordon, E. A., Henry, E., Peytcheva, M., & Sun, L. (2013). Discretionary disclosure and the market reaction to restatements. Review of Quantitative Finance & Accounting, 41, 75–110. doi:10.1007/s11156-012-0301-4