Abstract

Although social scientists have identified diverse behavioral patterns among children from dissimilarly structured families, scholars have progressed little in relating modern family processes to consumption-related decisions. Based on gaps and limitations identified in a review of the existing consumer decision-making literature, this study examines how children influence family consumption decision-making in single-mother families and posits a conceptual framework that integrates normative resource exchange theory with existing consumer decision-making model theory. The implications for a better understanding of processes rather than prevalent outcome-oriented focus for future research purposes are also discussed.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The scholarly and popular literature has established that (1) children influence family decision-making for both own-use and family-use products and services, (2) the influence mechanisms and dynamics differ markedly by family structure, and (3) single-mother families are proliferating in western societies. Nonetheless, social scientists often overlook decision-making processes in single-mother families. Each single-mother intra-family structure—such as unmarried partner, live-in grandparent(s), or stepparent with or without stepsibling(s)—warrants further scrutiny. During the last few decades, social scientists have applied various social science theories to understand children’s influence in family decision-making. By shifting from the prevalent outcome-oriented perspective to a process-oriented perspective and accounting for possible deviations from prevalent norms, these scientists may better capture the resources, interactions, and norms of single-mother families’ consumer decision-making processes. The proposed conceptual perspective and related propositions will facilitate this effort.

1. Introduction

The family is the locus of relationships, meanings, and values (Stacey, Citation1990), and consumption-related decision-making in the context of family life is a core consumer behavior process (Howard & Sheth, Citation1969; Scanzoni & Szinovacz, Citation1980). During the 1960s, consumer researchers began to study children’s role in family consumption decisions (Flurry, Citation2007; John, Citation1999). Although most researchers now concur that family, regardless of relationship structures, provide the best framework for understanding and predicting consumption-related behaviors (Ahuja, Capella, & Taylor, Citation1998; Epp & Price, Citation2008; Flurry, Citation2007; Palan & Wilkes, Citation1997; Thomson, Laing, & McKee, Citation2007; Waite, Citation2000), much of the evidence for this belief is dated, as most studies were conducted during the dual-parent-family-ubiquitous 1970s and 1980s (Flurry, Citation2007). In contrast to dual-parent families comprised of a married heterosexual couple, a single-parent is “a parent who is not currently living with a spouse; in other words, a single-parent may be married but not living with a spouse, divorced, widowed, or never married … . [I]f a second parent is present and not married to the first, then the child is identified as living with a single-parent” (U.S. Census, Citation2018; Winkler, Citation1993). In 2018, roughly 30% of U.S. households were headed by single females (U.S. Census, Citation2018), and more than half of U.S. children will become members of an alternatively structured family during the next decade (Amato & Keith, Citation1991; Rindfleisch, Burroughs, & Denton, Citation1997; U.S. Census, Citation2018).

Most research on single-parent families has focused on female-headed families because mothers typically rear children in cases of marital dissolutions, widowhood, or single-parenthood. Single-mother families are the second most common family type (after the traditional dual-parent households) in the U.S., and one out of every four children in the U.S. live in such families (U.S. Census, Citation2018). Given the trends in U.S. society, this already substantial group is more likely to expand than contract (Bumpass & Raley, Citation1995; Duncan & Rodgers, Citation1987; Edmondson, Citation1992; Norton & Glick, Citation1986); yet, little is known about children’s roles in these families’ consumption decisions. It is disconcerting to note interest in this important research topic has waned during the last decade despite sociodemographic trends indicating an ever-increasing number of single-mother families.

Several theoretical frameworks predominantly borrowed from economics and psychology—such as consumer socialization, the consumer decision-making model, resource exchange, and power theories—have grounded consumer research on children’s influence on consumption decision-making in families (see supplemental Table 2 for details). Generally, research on young consumers has followed one of two perspectives: (1) the cognitive development of children as consumers, which assumes children are rational and participate in decision-making for their own gain (John, Citation1999), and (2) the socio-cultural, which recognizes children as interactive participants in consumption decision-making outcomes (Cram & Ng, Citation1999; Flurry, Citation2007). Although each perspective evolved independently, the Caucasian nuclear family remains the common focus of most U.S.-based family research. As this family structure is considered the norm, the increasingly prominent single-mother family unit has often been neglected.

Two prominent gaps characterize academic knowledge about the influence of children on purchase decisions in single-mother families. First, most studies examine single member rather than multiple-member relational units (Epp & Price, Citation2008; Qualls, Citation1988; Thomson et al., Citation2007). As a result, the interpersonal dynamics of single-mother families—for example, a child assuming the role of an absent second adult—have been under-researched (Commuri & Gentry, Citation2000; Epp & Price, Citation2008). Second, outcome-oriented research on family and household decision processes, which has focused on understanding parents’ beliefs about their children’s involvement in decision-making and children’s point-of-purchase influence (Ahuja & Stinson, Citation1993; Ahuja & Walker, Citation1994) is the predominant form of inquiry (Qualls, Citation1988; Thomson et al., Citation2007). (See supplemental Table 2 for details on marketing-related research on children’s influence on family decision-making in single-parent families.)

To highlight these meaningful research gaps, first, the extant literature is distilled and limitations in existing theoretical frameworks used to study decision-making processes in single-mother families are identified. Next, a new process-oriented alternative to the prevalent outcome-oriented frameworks is posited, which may be more suitable for exploring children’s influence on decision-making processes in single-mother families. Finally, propositions for future research related to children’s vested interest in family purchases, consumption knowledge, parenting style, and gender-role orientation are examined. The focus on these four domains stems from their predominant coverage in the extant consumer research literature. Two caveats worth mentioning: (1) although the family unit is studied in disciplines such as social work, psychology, and economics, the primarily focus here is on the marketing literature as a representational choice based on emerging concepts (Spiggle, Citation1998), and (2) cross-cultural comparisons are beyond the scope of a literature review that focuses on U.S. family structures.

2. Gaps in the extant research on children’s influence on consumer decision making in single-mother families

Children’s behavior in families is a widely researched domain in various social sciences, including economics, social work, anthropology, and various psychology sub-fields. To ensure a manageable review of extant literature, only scholarly peer-reviewed journal articles in marketing, with a particular focus on consumer decision-making in families, is included. The reviewed literature was identified by conducting searches in the following journal aggregator databases: Business Source Premier, ABI/INFORM Complete, and Academic Search Premier. The search keywords were consumer decision making model, child/ren influence, and family decision making.

Publications since the early 1980s reveals a steady, albeit minimal, increase in the interest in single-mother families by consumer researchers (see John, Citation1999 for a review of pre-1999 studies). Of the roughly dozen published marketing studies since then, only four studies focused exclusively on single-mother families. Most studies have explored the beliefs of parents on their children’s influence on purchases in specific product categories within dual-parent families (Lee & Beatty, Citation2002; Palan & Wilkes, Citation1997). Despite the various findings of children’s roles in family decision-making, there is little information about consumption decisions in single-mother families (Flurry, Citation2007; Kourilsky & Murray, Citation1981; Qualls, Citation1988). Previous research on children’s influence in family decision-making outcome (see supplemental Table 1) can be organized into two broad categories: socioeconomic implications of children’s influence and consumer behavior implications of children’s influence.

Understanding consumption-related decision processes in single-mother families means understanding the social interactions between various relational units, such as between a child and its mother, a child and its mother’s cohabiting partner, and a child and its grandparent(s) (Fellerman & Debevec, Citation1993). As consumption experiences may occur outside the household (DeVault, Citation2003; Epp & Price, Citation2008), family is defined here as “networks of people who share their lives over long periods of time bound by ties of marriage, blood, or commitment, legal or otherwise, who consider themselves as family and who share a significant history and anticipated future of functioning in a family relationship” (Galvin & Brommel, Citation1999, p. 5). To help structure researcher comparisons across family structures, here “intra-family” refers to variations within single-mother and extended families—families with grandparents, a cohabiting unmarried partner, or step-parents living together—that are becoming increasingly common in Western societies (Bumpass & Lu, Citation2000; Bumpass & Raley, Citation1995; Kim & Lee, Citation1997; Mulkey, Crain, & Harrington, Citation1992; Swinyard & Sim, Citation1987; Tinson, Nancarrow, & Brace, Citation2008). These comparisons typical involve dual-parent versus single-parent families.

2.1. Socioeconomic implications of children’s influence

Researchers have often focused on the disadvantages of children reared in single-mother families (Bumpass & Lu, Citation2000; Bumpass & Sweet, Citation1989; Graffe & Lichter, Citation1999; Hetherington, Stanley-Hagan, & Anderson, Citation1989; Wojtkiewicz, Citation1992), including emotional trauma induced by family disruption, reduced economic resources, work-home role conflicts, and ineffective time management (Duckett & Richards, Citation1995; Dunn, Davies, O’Connor, & Sturgess, Citation2001). In single-mother families with only one income, for example, the absence of a second parent may mean reduced economic resources, especially if the mother is un(der)employed (McLanahan & Percheski, Citation2008; Ram & Hou, Citation2003; Seltzer, Citation1994). Typically, purchasing power is less for single-mother families than dual-parent families at similar income levels due to less discretionary income with one less income source (Hernandez, Citation1986; Ram & Hou, Citation2003; Seltzer, Citation1994).

Family structure may also partly explain children’s behavioral differences (Amato, Citation1987; Amato & Keith, Citation1991; Hetherington et al., Citation1989; Wojtkiewicz, Citation1992). For example, children living in step-families have more emotional problems than children living with single parents (Amato & Keith, Citation1991; Amato & Sobolewski, Citation2001). Relative to divorced single-parent families and never-married single-parent families, co-habiting single-parent families spend meaningfully less money on their children (DeLeire & Kalil, Citation2005; Duncan & Rodgers, Citation1987). Teenagers have more influence over the purchase of household and own-use products if they live in single-parent families rather than dual- or step-parent families (Mangelburg, Grewal, & Bristol, Citation1999). Adolescents displayed more materialistic tendencies and consumed more compulsively if they lived in non-traditional rather than dual-parent families (Burroughs & Rindfleisch, Citation1997; Rindfleisch et al., Citation1997). Relative to dual-parent families, single-parent families spend more on children’s entertainment and apparel but less on children’s education and books (Omori, Citation2010).

In contrast, some research indicates that children from non-traditional families may not always be harmed by their socioeconomic disadvantages (Amato, Citation1993; DeLeire & Kalil, Citation2002; Lang & Zagorsky, Citation2000; Seltzer, Citation1994). Difficult experiences, for example, may cause single-mothers and their children to bond more tightly than other household types (Coleman, Fine, Ganong, Downs, & Pauk, Citation2001; Moriarty & Wagner, Citation2004). Grandparents may play the role of the second nurturing adult in single-mother families (Eggebeen, Citation2005; Lussier, Deater-Deckard, Dunn, & Davies, Citation2002). The lower grades of high school students from one-parent families may be more attributable to within-family dynamics than economic disadvantages (Mulkey et al., Citation1992).

2.2. Consumer behavior implications of children’s influence

Comparisons in family decision-making outcomes between inter-family structures have been the primary focus for research on the consumption behaviors of families. Several studies have shown that differences in food choices (Ahuja & Walker, Citation1994; Wilson & Wood, Citation2004; Zick, McCullough, & Smith, Citation1996; Ziol-Guest, DeLeire, & Kalil, Citation2006) and leisure activities (Darley & Lim, Citation1986) exist between dual-parent families and single-mother families. Some research has explored the conflicts that arise from family, work roles (Heslop, Madill, Duxbury, & Dowdles, Citation2007; Thiagarajan, Chakrabarty, Lueg, & Taylor, Citation2007), and time management issues (Zick et al., Citation1996) faced by single-mothers; other research has examined how mothers help children cope with the divorce process and transition to a single-parent family dynamic (Bates & Gentry, Citation1994).

Although Hamilton and Catterall (Citation2006) did not focus only on single-mother families, 24 of the 30 impoverished families they studied were single-mother families. Children from these families often influence own-use product decisions by inflicting extreme persuasion tactics (such as blackmail) on their parents, who typically acceded to their children’s wishes as an expression of love. Single-mothers were ashamed of their economic status, wanted to shield their children from the social stigma associated with poverty, and often satisfied their children’s purchase requests by reducing costs in other areas, such as food purchases (Hamilton, Citation2009).

In contrast, family decision-making processes often require connecting the goals of family members, yet some decisions, such as those related to collective consumption experiences, are co-creational and reinforce family bonds without creating a conflict-resolution agenda (Epp & Price, Citation2008; Lee & Collins, Citation2000; Thomson et al., Citation2007). As they often conduct more extensive information searches and thus attain meaningful consumption knowledge, children from single-parent families may participate more effectively and have more influence than children from dual-parent families in making family-level consumption decisions (Foxman, Tansuhaj, & Ekstrom, Citation1989; Kim & Lee, Citation1997; Swinyard & Sim, Citation1987). Given the lack of knowledge about their decision processes, the consumption behaviors of single-mother families warrant further research (Flurry, Citation2007; Thomson et al., Citation2007; Tinson et al., Citation2008).

3. Gaps in the previously applied theoretical frameworks

Most theoretical approaches consider children’s influence on family consumption decisions but do not offer nuanced insights into the ways their influence is exercised. This is particularly true for single-mother families with a dissimilar dynamic to dual-parent families. Consumer researchers have applied some theories, such as social exchange theory (which includes power and resource exchange theory), role theory, and reactance theory, to studies on adult roles in family decision-making. Role theory, which defines family work-role conflict as “a form of inter-role conflict in which the role pressures from the work and family domains are mutually incompatible in some respect” (Greenhaus & Beutell, Citation1985, p. 77), may explain how a single-mother’s resources—such as time, energy, and attention—are divided between work and family, and so explain some of the dynamics of consumer behavior in single-mother families (Thiagarajan et al., Citation2007). Reactance theory, which refers to the motivational state caused by threats to personal freedom, can explain how children react to parental disapproval through their product choices (Rummel, Howard, Swinton, & Seymour, Citation2001). Role theory and reactance theory have grounded research on the relationship between parental roles and reactions to children’s influence in family decision-making. Subsequently, these theories were extended to children’s roles in family decision-making (Flurry, Citation2007; Peyton, Pitts, & Kamery, Citation2004).

3.1. Consumer socialization

Consumer socialization theory is the most common theoretical framework used in studies on children’s influence on consumption-related decisions in families. With roots in socialization theory, consumer socialization is “the processes by which young people acquire skills, knowledge, and attitudes to function as consumers and to develop consumer-related self-concepts” (Ward, Citation1974, p. 2). It has inspired research on intergenerational influence, which is the “within-family transmission of information, beliefs, and resources from one generation to next, a fundamental mechanism by which culture is sustained over time” (Moore, Wilkie, & Lutz, Citation2002, p. 1). Studies in this vein have explored the role of parents’ instructions and supervision, gender orientation, education, occupation, and income on their children’s consumer skill development, (Beatty & Talpade, Citation1994; Foxman, Tansuhaj, & Ekstrom, Citation1988; Gregan-Paxton & Roedder John, Citation1995; Marquis, Citation2004). Indirect influences, such as children’s observation and imitation of a parent’s consumption activities, also have been analyzed (Gregan-Paxton & Roedder John, Citation1995).

Consumer socialization theory has prompted several useful findings. For example, parents in general and mothers in particular tend to co-shop and influence the learning of consumption behaviors of their daughters more than their sons (Moschis, Citation1985; Moschis & Churchill, Citation1978). In addition to parental approval, brand name associations and peer approval influence fashion-clothing-related purchase decisions of tween (9–12 years) girls (Grant & Stephen, Citation2005). Because children are now much more aware of brands (John, Citation1999), they may exert a greater influence at an earlier age than parents realize (Dotson & Hyatt, Citation2000; Harradine & Ross, Citation2007). However, the “outcomes rather than processes” focus of this framework ignores intra-family negotiations (John, Citation1999). For example, contrary to the received wisdom that intergenerational influence is transmitted uni-directionally from parent to child, daughters predict their mother’s brand preferences more accurately than mothers predict their daughter’s preferences (Mandrik, Fern, & Bao, Citation2005).

3.2. Consumer decision-making model

The multi-stage consumer decision-making model is comprised of problem recognition, information search, alternative evaluation, final choice, and purchase decision (Davis, Citation1976; Sheth, Citation1974). Researchers have applied this model to studies on outcomes for specific stages in family decision-making (Corfman & Lehmann, Citation1987; Gotze, Prange, & Uhrovska, Citation2009; John, Citation2008; Qualls, Citation1988). For example, single-mother’s beliefs about their children’s influence at certain decision stages differ by children’s age and mother’s education (Ahuja & Stinson, Citation1993). Children in single-mother families may be more involved in the information search stage and more likely to prefer shopping online than children from dual-parent families (Tinson et al., Citation2008).

Researchers also have applied this model to studies on other moderating factors, such as the number of family members, number of children, age of parent(s), and household income. Although it yielded verifiable hypotheses, this model’s individual goal-oriented focus and limited demographic scope allow for few insights into decision processes, especially in single-mother families. For instance, researchers do not know why product decisions may be more influenced by teenagers in single-mother families than in step-families (Mangelburg et al., Citation1999).

3.3. Social exchange theory (power theory and resource exchange theory)

Social exchange theory is a major inter-disciplinary paradigm in the social sciences (Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005; Lawler & Thye, Citation1999). The common factor that binds all social exchanges is social interaction or exchange resulting in obligations (Emerson, Citation1976). The basic tenets of self-interest and interdependency in social exchange include the role of individual power (Power Theory) often asserted through one’s resources (Resource Theory; Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005). Consumer researchers have adapted and applied both power and resource exchange theories to studies on husband-wife decision-making processes (Peyton et al., Citation2004), which are explained in more detail below.

3.3.1. Power theory

Power is “the ability of an individual within a social relationship to carry out his or her will, even in the face of resistance by others” (McDonald, Citation1980, p. 842). Power alludes to conflicts in relationships and the power wielded by group members to achieve an individually preferred goal (Dunbar, Citation2004; French & Raven, Citation1959; McDonald, Citation1980). In an interdependent relationship, such as between parents and children, the former’s power often determines the latter’s ability to manage conflict and influence decision outcomes (Williams & Burns, Citation2000). To negotiate and maintain power over decision outcomes, members of multi-person families tend to form coalitions, with adult coalitions often dominating those formed by children (Grusky, Bonacich, & Webster, Citation1995).

Perceived parental power is parents’ believed ability to influence children to do or believe something (Bao, Fem, & Sheng, Citation2007; Flurry & Burns, Citation2005). For example, children who perceive greater parental power typically tend to use persuasive strategies to influence family decisions (Bao et al., Citation2007). Power theory generally assumes that consumers are rational; hence, non-rational factors in decision-making, such as emotions or norms, are ignored. Nonetheless, the power component in pester power (e.g., children’s point-of-purchase nagging of parents, who comply and purchase problematic goods to avoid embarrassment (McDermott, O’Sullivan, Stead, & Hastings, Citation2006)), would be difficult to interpret without considering norms violations (Williams & Burns, Citation2000). Generally, parents are more powerful than their children; hence, parents saying “because I say so” is an intractable dictum to trounce. However, if the need to exert control over another disappears for relationships without conflict (Dunbar, Citation2004), then power theory may not pertain to decision-making processes when parents and children are in accord. For instance, impoverished single-mothers may purchase unhealthy foods as acts of love or to abate feelings of guilt towards their children (Hamilton, Citation2009; Hamilton & Catterall, Citation2006). Also, power theory may not pertain to families with young children (i.e., families with members of vastly disparate power) (John, Citation1999). Thus, power theory may not fully explain the role played by children in decision-making processes within single-mother families.

3.3.2. Resource exchange theory

According to resource exchange theory, “resources are anything one partner may make available to the other partner, helping the latter satisfy his/her needs or attain his/her goals” (Blood & Wolfe, Citation1960, p. 12). Differences in socioeconomic resources, such as occupation, education, and income, induce people to negotiate their own goals in group decisions (Blood & Wolfe, Citation1960; Dunbar, Citation2004). Resource exchange theory and consumer research share an exchange foundation. The stages—resource context, resource exchange, and resource outcome (Lawler & Thye, Citation1999)—that organize how a person’s resources are manifest in social exchanges are similar to how consumer decision-making processes are initiated and concluded. Consumer researchers have considered the exchange of socioeconomic resources, such as love, personal services, goods, money, information, and status, in their studies on children’s influence in family decision processes (Carey, Shaw, & Shiu, Citation2008; Flurry, Citation2007; Park, Tanushaj, & Kolbe, Citation1991). However, a major limitation of social exchange theories is the purely economic nature of the exchange process, in which people attempt rationally to achieve their goals by maximizing their rewards while minimizing their costs (Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005; Lawler & Thye, Citation1999).

4. Towards a process-oriented approach

Although they have led to many useful findings, the aforementioned theories cannot fully explain the dissimilar consumption-related decision-making influences of children in traditional dual-parent versus single-mother families (Bao et al., Citation2007; Flurry, Citation2007; Flurry & Burns, Citation2005; Gronhoj, Citation2006; Tinson & Nancarrow, Citation2005). In addition, related studies grounded in power and resource theories typically focus on parents’ beliefs about outcomes rather than children’s influences on decision-making processes. As decision-making studies based on one spouse’s perspective cannot fully capture the other spouse’s perspective (Davis, Citation1976), studies limited to parents’ outcome-oriented perspectives cannot fully capture their children’s influences. “It seems likely that measures of decision outcome tap a very different aspect of decision-making than do measures of decision process” (Davis, Citation1976, p. 250). Thus, a shift from outcome orientation to process orientation may reveal previously unrecognized co-created family goals and decision processes in single-mother families (DeVault, Citation2003; Epp & Price, Citation2008). To pursue a process-oriented approach, normative resource exchange theory, which researchers can use to study family dynamics within single-mother intra-families that may not conform to dual-parent family norms, is recommended (Epp & Price, Citation2008; Tinson et al., Citation2008).

4.1. Normative resource exchange theory

Normative resource exchange theory, in addition to the classic social exchange concept of each person’s use of individual resources (such as money, knowledge, expertise, and love) to attain a group consumption goal favorable to that person (Blood & Wolfe, Citation1960), also accounts for the normative influences in collective social interactions (Crosbie-Burnett et al., Citation2005; Lawler & Thye, Citation1999). It offers a more in-depth perspective for studying children’s consumption-related influence because clearly defined decision-making norms for directing familial interactions (i.e., social exchange dynamics) in traditional dual-parent families may not pertain to single-mother and intra-family structures (Bianchi & Casper, Citation2005; Crosbie-Burnett & Giles-Sims, Citation1991; Giles-Sim & Crosbie-Burnett, Citation1989). Introducing norms into studies of exchange processes enables researchers to consider how socio-cultural aspects influence each person’s consumption behaviors. Although social scientists have yet to develop a consensus about norms, the two definitions of norms listed below, developed a half-century apart, best address norms within single-mother intra-family structures that typically lack the traditional dual-parent family’s normative behavioral expectations (Epp & Price, Citation2008; Flurry, Citation2007; Tinson et al., Citation2008):

A “rule or a standard that governs our conduct in the social situations in which we participate. It is a societal expectation. It is a standard to which we are expected to conform whether we actually do so or not” (Bierstedt, Citation1963, p. 222).

A “voluntary behavior that is prevalent within a reference group” (Interis, Citation2011, p. 1).

Both definitions concur that norms are expected behaviors established by a reference group. Consequently, norms serve as a “necessary condition” whereas resources are considered as the “sufficient condition” of power and exchange in family decision-making processes (McDonald, Citation1980). For example, in husband-wife dyads, especially in western societies with evolving gender roles, norms are crucial to understanding exchange processes (Peyton et al., Citation2004; Rodman, Citation1972). Most consumer research categorizes parenting styles based on dual-parent families. Similarly, applications of power and resource exchange theories in consumer behavior studies tend to assume a mother and father as the primary actors and the lesser-powerful children as attempting to influence decision outcomes.

Normative influences such as parenting style can explain a single-mother’s decision-making power. For instance, children in single-parent families tend to exert greater power and are generally unwilling to share this power with new step-parents (Crosbie-Burnett et al., Citation2005). These children may possess resources, such as an ability to earn extra income or extensive consumer knowledge that may tilt the negotiation balance in their favor. Similarly, a step-parent who provides financial support may exert equal or greater control on resource exchanges and consequent decision-making processes than a cohabiting but unmarried partner or single-mother living alone. Given the likely relative levels of commitment, step-parent’s preferences are likely to be weighted more heavily than a live-in partner’s preferences. For example, a daughter and her single-mother may agree to visit Disneyland for their annual vacation, yet the step-parent (and meaningfully older/younger step-siblings) may decide, and subsequently prevail, to a family tour of historical sites in Washington, DC.

Unless consumer researchers review processes involved in such instances, the nuances are lost in outcome-oriented approaches that only review the result—that is, the children influenced the decision. A co-habiting partner of a single-mother is an adult in a romantic relationship with a single-mother and living in the same household. This non-kin member may prompt resource exchange contexts and outcomes that differ markedly from dual-parent families. For example, a child may exert less influence on a purchase paid partly or fully by a cohabiting partner. Alternatively, a child may exert more influence if the mother feels guilty about a live-in partner who is not the child’s biological parent. Normative resource exchange theory can account for the influence of these norms, which are missing from the more rational economic exchange orientation of classic resource exchange theory (Lawler & Thye, Citation1999). Subsequently, augmenting normative resource exchange theory with the consumer decision-making model should provide a superior framework for explaining decision-making interactions between mother, child(ren), and other members of the family unit.

5. Process oriented approach as a new conceptual perspective

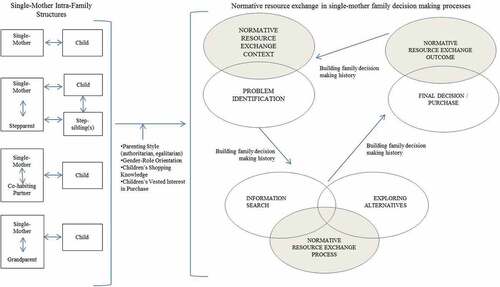

Recently, consumer researchers have suggested a shift in the consumer decision-making model from households to families to account for various relational units in single-mother families (DeVault, Citation2003; Epp & Price, Citation2008). Researchers could also adopt the proposed new process-oriented approach, depicted in Figure , for studying the influence of children in single-mother families on consumption-related decision processes. This new framework aligns the context, process, and outcome phases of normative resource exchange theory proposed by sociologists (Crosbie-Burnett et al., Citation2005; Lawler & Thye, Citation1999; Strauss, Citation1978) with the classic consumer decision-making model adapted by consumer researchers (Davis, Citation1976; Sheth, Citation1974). As the decision-making dynamic may differ between single-mother intra-family structures, this framework can account for these differences. For instance, when a grandparent(s) contributes financially or emotionally, the single-mother now plays the role of both child and parent in that family unit. In this case, highly involved grandparents may usurp a young child’s influence over decision-making processes. Alternatively, the grandparent(s) may spoil a child, thus tilting the decision-making in a child’s favor and testing a single-mother’s parental authority.

The lower left side of Figure illustrates the most commonly researched mediating normative variables in consumer decision-making, such as gender role orientation, parental authority styles (patriarchal, egalitarian), children’s shopping knowledge, and vested interest (Crosbie-Burnett et al., Citation2005). For example, consider a single-mother and a mother from a traditional dual-parent family of similar age, employed in white collar jobs with high incomes, and living in affluent neighborhoods. Their family decision-making dynamics may differ markedly if the single-mother adopts a laissez-faire parenting style and the dual-parent family abides by a conservative, patriarchal approach, leaving the decision-making to the father (see subsequent discussions about parenting styles under Research Propositions).

The right side of Figure shows the three phases in normative resource exchange that inform and shape family decision-making processes. The overlapping of normative resource exchange processes and decision-making stages helps to explain the intricate combination of various factors (individual resources and normative influences) that determine the outcome in family decision-making. The normative resource exchange context comprises the history between family members and their respective resource bases at the onset of a collective decision-making process (Crosbie-Burnett et al., Citation2005; Epp & Price, Citation2008). For example, if a family needs a new television, the financial contribution of a step-parent in a single-mother family may affect the child’s role in the decision-making process. Such processes are captured in the proposed conceptual framework via the normative resource exchange context between the step-parent and mother-child dyad (financial power) and family decision-making history between mother-child dyad (relational bond); in contrast, outcome-oriented research approaches may overlook such pre-existing factors.

For parsimony, the bottom right side of Figure combines the information search and exploring alternatives stages of the consumer decision-making model. These two stages were combined because family members can search for information and compare multiple products via basic internet searches. This framework considers how norms influence single-mother families, as they may deviate from dual-parent family norms. For example, how do the step-parent’s (adulthood, money), child’s (extensive product knowledge, kinship, love), and single-mother’s (money, parental authority, parenting style, romantic and parental love) resources inform and influence the collective nature of information search and alternative evaluation stages in family decision-making? To continue with the television example, the single-mother may impose a price ceiling—based on limited financial resources—before seeking product information. Although the child may suggest several alternatives based on extensive knowledge about televisions (shopping knowledge), he/she may try to persuade (vested interest) his/her mother to choose a personally preferred set. Most familial interactions occur during this decision-making stage, with each family member attempting to use their respective resources to influence the outcome in their favor.

In dual-parent families, the family history between spouses typically is more standardized than for intra-family structures in single-mother family units, which may vary considerably. For instance, adult relationship recency and step-sibling presence will affect the family decision-making experience. The proposed framework captures such contextual nuances to better portray how norms are formed and exercised around resource exchange within single-mother families. As shown in the upper right side of Figure , the normative resource exchange outcome overlaps the family’s final purchase decision. To continue the television purchase example, a single-mother may indulge her child and buy an expensive HDTV. Despite the mother’s initial advantage (parental authority), the child may influence the final decision due to normative factors such as parental love and kinship rights. Subsequently, she may disallow her child from participating extensively in the next major family purchase to assuage the step-parent whose preference was overruled in the HDTV purchase despite being the primary monetary contributor.

More generally, Figure illustrates that families can create procedural history at any decision-making stage (Epp & Price, Citation2008). With recurrent purchase decisions—such as where to dine, where to vacation, and what gifts to give on birthdays and other holidays—successive choices and related experiences may evolve into patterned collective consumption behaviors and the creation of little-understood alternate norms in single-mother family types. By treating family decision-making as a cyclical rather than a sequential process, researchers may ascertain if normative variables (e.g., parenting styles, children’s vested interest, and gender-role orientation) in single-mother families diverge from traditional norms (in dual-parent families) and how these may mediate decision-making where non-kin family members use their respective resources to produce collective decisions. This nonlinear approach considers the iterations between stages as new information and resources are acquired and applied to decision-making processes. The proposed perspective is meant to “sensitize and orient researchers to certain critical processes” (Turner, J, Citation1986, p. 11) in family decision-making. As processes differ between single-mother and dual-parent families, the perspective should spur inclusion of norms in studies of consumption-related decision-making processes within single-mother families. Like sensitizing theories that entice researchers to investigate relationships in novel ways (Baxter, Citation2004), this perspective stresses the importance of children’s influence on these processes.

6. Research propositions

Consumer researchers have focused on several aspects of children’s influence in family decision-making. For example, studies have shown that children have greater influence in purchasing own-use products than family-use products (Beatty & Talpade, Citation1994; Flurry & Burns, Citation2005; Foxman et al., Citation1988, Citation1989; Lee & Beatty, Citation2002). Children who have a vested interest in the purchase of a product may assert greater influence in family decision-making (Flurry & Burns, Citation2005; Tinson & Nancarrow, Citation2007), which in turn may be further enhanced if they have extensive product-related knowledge (Beatty & Talpade, Citation1994). Parenting style, ranging from traditional/authoritarian to modern/egalitarian, as well as the related notion of gender-role orientation, are other prime areas of interest for consumer behavior researchers (Bao et al., Citation2007; Lee & Beatty, Citation2002; Tinson & Nancarrow, Citation2005, Citation2007). Researchers have found differences in children’s influence on consumption behaviors for single-parent versus dual-parent families in four domains—children’s vested interest in purchases, children’s shopping knowledge, parenting style, and gender-role orientation. Propositions in these domains are identified below.

6.1. Children’s vested interest in purchases

Preference intensity, a motivational construct conceptualized as “the extent to which a person desires to achieve a particular outcome or purchase” (Flurry & Burns, Citation2005, p. 595), may be the most significant predictor of a person’s influence in group decisions (Corfman & Lehmann, Citation1987). Also theorized as children’s vested interest in purchases, consumer research supports this observation (Ahuja & Walker, Citation1994; Beatty & Talpade, Citation1994). Although children tend to assert greater influence in product categories that are most relevant to them (Beatty & Talpade, Citation1994; John & Lakshmi-Ratan, Citation1992), children from single-mother families are believed to have greater influence than those from dual-parent families over both their own-use and family-related product purchases (Mangelburg et al., Citation1999). Relative to children in step-families and intact families, children in single-mother families are more involved in family-related-product purchases (Tinson et al., Citation2008). Such findings suggest the following:

P1: Relative to children in dual-parent families, children in single-mother families have a greater vested interest in all stages of the consumer decision-making process (i.e., problem recognition, information search, alternative evaluation, and final purchase) for (a) own-use products, and (b) family-use products.

P2: Relative to children in single-mother-only or live-in grandparent(s) families, children in single-mother-families with either a live-in partner or step-parent and/or step-sibling(s) have less vested interest in all stages of the consumer decision-making process (i.e., problem recognition, information search, alternative evaluation, and final purchase) for (a) own-use products, and (b) family-use products.

6.2. Children’s shopping knowledge

Consumer socialization theory asserts that parents are children’s most important socialization agents (John, Citation1999). Other than parents, peer groups, as well as popular culture, contribute extensively to children’s knowledge about products and services (Moschis, Citation1985). Children tend to make risk-prone choices if they are made aware of prior parental approval signals such as advisory labels on music (Christenson, Citation1992). In general, people with relatively more resources in a social unit have a greater influence over unit-related decision processes; hence, buying decisions are typically more influenced by parents than their children (Foxman et al., Citation1989).

Nonetheless, if information is power, then complex products (like consumer electronics) may be more influenced by tech-savvy children (Belch, Krentler, & Willis-Flurry, Citation2005; Thomson & Laing, Citation2003). Under this reverse socialization outlook, parents acquire consumer knowledge from their children (Ekstrom, Citation2007; Foxman, Tanushaj, & Ekstrom, Citation1987). Relative to children in dual-parent families, children in single-parent families may be more inclined to shop with parents online during the information search stage (Tinson et al., Citation2008). Due to outcome oriented approaches, researchers can only surmise about the cause. This greater influence by children from single-mother families (Ahuja & Stinson, Citation1993; Ahuja & Walker, Citation1994; Darley & Lim, Citation1986) suggests the following inter- and intra-family comparisons:

P3: Relative to children in dual-parent families, children in single-mother families (a) possess more shopping knowledge and expertise, (b) volunteer more shopping-related knowledge during the consumer decision-making processes of problem recognition, information search, and alternative evaluation stages, and (c) are more influential during the consumer decision-making processes of purchase stage.

P4: Relative to children in single-mother-only or live-in grandparent(s) families, children in single-mother families with either a live-in partner or step-parent and/or step-sibling(s) (a) possess less shopping knowledge, (b) contribute less shopping knowledge during the consumer decision-making processes of problem recognition, information search, and alternative evaluation stages, and (c) are less influential during consumer decision-making processes of purchase stage.

6.3. Parenting style

Parental authority and communication style affect children’s influence in family decision-making (Mangelburg et al., Citation1999). To socialize children, parents tend to rely on either socio-oriented or concept-oriented communications (Caruana & Vasallo, Citation2003). Socio-oriented parents monitor and control their children’s behavior in relation to societal norms. In contrast, concept-oriented parents allow children to explore phenomena and develop independent views based on experiences and observations.

Parents tend to adopt one of four parenting styles: authoritarian, authoritative, permissive, and disengaged (Baumrind, Citation1991; Maccoby & Martin, Citation1983; Pelaez, Field, Pickens, & Hart, Citation2008). Authoritarian parents require total control, with strict rules for maintaining order with little warmth or affection (Robinson, Mandelco, Olsen, & Hart, Citation1995). The authoritarian style typically entails rigid control, close supervision, and control by anxiety induction (Baumrind, Citation1991; Robinson et al., Citation1995). In contrast, authoritative parents generally establish rules and guidelines for children to follow, are more willing to listen to questions and understand children’s viewpoint, and are more forgiving and nurturing than authoritarian parents (Baumrind, Citation1991; Maccoby & Martin, Citation1983). Permissive parents make few rules and rarely implement them. When their children are incapable of informed decision-making, such parents suggest alternatives and are amenable to the outcome irrespective of behavioral concerns (Baumrind, Citation1991; Maccoby & Martin, Citation1983). Disengaged parents are uninvolved; they meet children’s needs but are generally detached from their children’s lives (Pelaez et al., Citation2008).

Due to guilt or the need to compensate for the missing second parent, single-mothers tend to adopt parenting styles based on personal preferences and family circumstances. In contrast, single-mothers with the support of intra-family structures (such as a step-parent or live-in partner) tend to mimic the egalitarian parenting styles found in some dual-parent families (Hertz, Citation2006). However, there is little research on parenting styles of single-mother families. Possible parenting style variations in single-mother intra-families suggest the following:

P5: Relative to dual-parent families, single-mother families adopt less authoritarian and more permissive parenting styles, which leads to greater involvement and influence of children in consumer decision-making processes.

P6: Relative to single-mother-alone or live-in grandparent(s) families, single-mother families with a step-parent or live-in partner adopt greater authoritarian and less permissive parenting styles, which leads to less involvement and influence of children in consumer decision-making processes.

6.4. The relevance of gender-role orientation

Gender-role orientation in families is “the extent to which children as well as adults display gender stereotypic behavior or state a preference for a particular type of gender role” (Tinson & Nancarrow, Citation2005, p. 7). Extensive research on gender roles has been conducted on husband-wife decision-making (Belch & Willis, Citation2002; Godwin & Scanzoni, Citation1989; Kaufman, Citation2000). Mother’s employment status and familial gender-role orientation may affect how children influence family decision-making (Lee & Beatty, Citation2002). For example, girls tend to negotiate more directly than boys negotiate; girls use more indirect approaches to secure other people’s cooperation and responsiveness (Cowan, Drinkard, & MacGavin, Citation1984). Girls may gather information extensively and may be confident in both their product-related knowledge and their ability to persuade and gain permission—especially from their mothers—to buy products of their choice (Grant & Stephen, Citation2005; Russell & Tyler, Citation2002). Conversely, adolescent girls who participated in stereotypical “girlie” activities, such as shopping for tea-party clothes in Girl Heaven stores, may resent conforming to these formulaic expectations (Russell & Tyler, Citation2002). As adults, people who experienced a secure and fulfilling childhood in single-mother families did not associate their parents with common gender stereotypes (Gerson, Citation2004).

Women who opt for motherhood by choice tend to oppose the normative prescription of traditional heterosexual family structure (Benjamin & Nilsen, Citation2009; Hertz, Citation2006). For example, in the absence of gender roles, biological mothers in black and lesbian step-families appropriate more power than non-biological mothers (Moore, Citation2008). Recent studies on gender-role orientation suggest looking beyond normative stereotypes and recognizing the importance of gender roles in families (Tinson et al., Citation2008). For example, children reared in gender-fair families tend to believe that boys and girls are opposite and unequal despite prevailing societal beliefs about gender equality (Risman, Citation1998). If stereotypical gender behavior is more common in dual-parent families than in single-mother families, and if such behavior is less common in single-mother families with a step-parent or live-in partner than in other single-mother family structures, then the following are suggested:

P7: Relative to boys (girls) in dual-parent families, boys (girls) in single-mother families are more informed consumers and participate more in consumer decision-making processes (i.e., adult-equivalent participation).

P8: Relative to boys (girls) from single-mother families with a step-parent or live-in partner, boys (girls) from other-structured single-mother families are more informed consumers and participate more in consumer decision-making processes (i.e., adult-equivalent participation).

7. Conclusion

Many factors affect consumer decision-making in single-mother families. Societal and marketplace pressures on never-married-single-mothers often induce negative work-family role strains (Bock, Citation2000; Thiagarajan et al., Citation2007). Cohabitation and re-marriage create family structures in which children contend with a step-parent (often of different race or ethnicity) and step-sibling(s) (often of meaningfully different age(s)) (Bumpass & Lu, Citation2000; Bumpass & Raley, Citation1995; Bumpass, Raley, & Sweet, Citation1995; Mulkey et al., Citation1992). Children may be less involved in step-families than in dual-parent or single-mother-alone families because step-parents often adopt a disengaged parenting style (Hetherington et al., Citation1989; Kurdek & Fine, Citation1993; Mangelburg et al., Citation1999).

Mother’s role within the family affects children’s influence and behaviors related to consumer decision-making. As parents, mothers tend to be the primary adult involved in gift purchase decisions for children across family structures (Clarke, Citation2008). Similarly, children attribute their consumer decision-making styles to their mother’s influence (Kim, Lee, & Tomiuk, Citation2009). The unmarried single woman who delays motherhood for career development and a larger disposable income may allow her children greater influence over consumption decisions (Bock, Citation2000). Single-parents generally believe their adolescent children have a greater influence over consumption choices (Mangelburg et al., Citation1999). To compensate for their parent’s time-strapped life, children in single-parent families must often perform household-related duties and shop alone (Caruana & Vasallo, Citation2003), thus playing adult-equivalent roles atypical in dual-parent families.

It is well established that (1) children influence family decision-making for both own-use and family-use products, (2) the influence mechanisms and dynamics differ markedly by family structure, and (3) single-mother families are proliferating in western societies. Nonetheless, social scientists often overlook decision-making processes in single-mother families. Each single-mother intra-family structure—such as live-in grandparent(s), unmarried partner, and step-father with or without step-sibling(s)—warrants closer scrutiny.

During the last few decades, social scientists have applied various social science theories to understand children’s influence in family decision-making. By shifting from the prevalent outcome-oriented perspective to a process-oriented perspective and accounting for possible deviations from prevalent norms, these scientists may better capture the resources, interactions, and norms of single-mother families’ consumer decision-making processes. The proposed conceptual perspective and related propositions will facilitate this effort.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (23.5 KB)Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sarita Ray Chaudhury

Sarita Ray Chaudhury is an Associate Professor of Marketing at Humboldt State University, a California State University campus located in Arcata, California, USA. Sarita’s research involves understanding the cultural meanings of consumer behaviour, with multiple journal and book chapter publications on these topics.

Michael Hyman

Michael Hyman is Distinguished Achievement Professor of Marketing at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces, New Mexico. His more than 95 academic journal articles, 60 conference papers, 4 co-authored/co-edited books, attest to his writing compulsion. He has served on 16 editorial review boards and as a journal co-editor. Currently, he is a Journal of Business Ethicssection editor and a Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice associate editor. His research interests include marketing theory, marketing ethics, consumer response to advertising, survey research methods, and philosophical analyses in marketing.

References

- Ahuja, R., Capella, L. M., & Taylor, R. D. (1998). Child influences, attitudinal and behavioral comparisons between single-parent and dual parent households in grocery shopping decisions. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 6(1), 48–18. doi:10.1080/10696679.1998.11501788

- Ahuja, R., & Stinson, K. (1993). Female-headed single-parent families: An exploratory study of children’s influence in family decision-making. Advances in Consumer Research, 20, 469–474.

- Ahuja, R., & Walker, M. (1994). Female-headed single-parent families’ comparisons with dual parent households on restaurant and convenience food usage. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 11(4), 41–54. doi:10.1108/EUM0000000003990

- Amato, P. R. (1987). Family processes in one-parent, stepparent, and intact families: The child’s point of view. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 49(2), 327–337. doi:10.2307/352303

- Amato, P. R. (1993). Children’s adjustment to divorce: Theories, hypotheses, and empirical support. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 55(1), 23–38. doi:10.2307/352954

- Amato, P. R., & Keith, B. (1991). Parental divorce and the well-being of children: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 110(1), 26–46. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.26

- Amato, P. R., & Sobolewski, J. M. (2001). The effects of divorce and marital discord on adult children’s psychological well-being. American Sociological Review, 66(6), 900–921. doi:10.2307/3088878

- Bao, Y., Fem, E. F., & Sheng, S. (2007). Parental style and adolescent influence in family consumption decisions: An integrative approach. Journal of Business Research, 60(7), 672–680. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.01.027

- Bates, M. J., & Gentry, J. W. (1994). Keeping the family together: How we survived the divorce. Advances in Consumer Research, 21, 30–34.

- Baumrind, D. (1991). The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. Journal of Early Adolescence, 11(1), 56–95. doi:10.1177/0272431691111004

- Baxter, L. A. (2004). Relationships as dialogues. Personal Relationships, 11(1), 1–22. doi:10.1111/pere.2004.11.issue-1

- Beatty, S. E., & Talpade, S. (1994). Adolescent influence in family decision-making: A replication with extension. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(2), 332–341. doi:10.1086/jcr.1994.21.issue-2

- Belch, M. A., Krentler, K. A., & Willis-Flurry, L. A. (2005). Teen internet mavens: Influence on family decision-making. Journal of Business Research, 58(5), 569–575. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2003.08.005

- Belch, M. A., & Willis, L. A. (2002). Family decision at the turn of the century: Has the changing structure of households impacted the family decision-making process? Journal of Consumer Behavior, 2(2), 111–124. doi:10.1002/cb.94

- Benjamin, O., & Nilsen, A. (2009). Two perspectives on ‘single by chance, mothers by choice (2006)’ by Rosanna Hertz. Community, Work & Family, 12(1), 135–140. doi:10.1080/13668800802627942

- Bianchi, S., & Casper, L. (2005). Explanations of family change, a family demographic perspective. In V. Bengtson, Alan C. Acock, Katherine R. Allen, Peggye Dilworth-Anderson, & David M. Klein (Eds.), Sourcebook of family theory and research (pp. 93–118). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Bierstedt, R. (1963). The social order. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Blood, R. C., & Wolfe, D. M. (1960). Husbands and wives: The dynamics of married living. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

- Bock, J. D. (2000). Doing the right thing? Single-mothers by choice and the struggle for legitimacy. Gender & Society, 14(1), 62–86. doi:10.1177/089124300014001005

- Bumpass, L., & Lu, -H.-H. (2000). Trends in cohabitation and implications for children’s family contexts in the United States. Population Studies, 54(1), 29–41. doi:10.1080/713779060

- Bumpass, L., & Raley, K. R. (1995). Redefining single-parent families: Cohabitation and changing family reality. Demography, 32(1), 97–109. doi:10.2307/2061899

- Bumpass, L., Raley, K. R., & Sweet, J. A. (1995). The changing character of stepfamilies: Implications of cohabitation and nonmarital childbearing. Demography, 32(3), 425–436. doi:10.2307/2061689

- Bumpass, L., & Sweet, J. A. (1989). Children’s experience in single-parent families: Implications of cohabitation and marital transitions. Family Planning Perspectives, 21(6), 256–260. doi:10.2307/2135378

- Burroughs, J. E., & Rindfleisch, E. (1997). Materialism as a coping mechanism: An inquiry into family disruption. Advances in Consumer Research, 24, 89–97.

- Carey, L., Shaw, D., & Shiu, E. (2008). The impact of ethical concerns on family consumer decision-making. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 32(5), 553–560. doi:10.1111/ijc.2008.32.issue-5

- Caruana, A., & Vasallo, R. (2003). Children’s perception of their influence over purchases: The role of parental communication patterns. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 20(1), 55–66. doi:10.1108/07363760310456955

- Christenson, P. (1992). The effects of parental advisory labels on adolescent music preferences. Journal of Communications, 42(1), 106–113. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1992.tb00772.x

- Churchill, G. A., & Moschis, G. P. (1979). Television and interpersonal influences on adolescent consumer learning. Journal of Consumer Research, 6(1), 23–35. doi:10.1086/208745.

- Clarke, P. (2008). Parental communication patterns and children’s christmas requests. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 25(6), 350–360. doi:10.1108/07363760810902486

- Coleman, M., Fine, M. A., Ganong, L. H., Downs, K. J. M., & Pauk, N. (2001). When you’re not the brady bunch: Identifying perceived conflicts and resolution strategies in stepfamilies. Personal Relationships, 8(1), 55–73. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2001.tb00028.x

- Commuri, S., & Gentry, J. W. (2000). Opportunities for family research in marketing. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 4(5), 285–303.

- Corfman, K. P., & Lehmann, D. R. (1987). Models of cooperative group decision-making and relative influence: An experimental investigation of family purchase decisions. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(1), 1–13. doi:10.1086/jcr.1987.14.issue-1

- Cowan, G., Drinkard, J., & MacGavin, L. (1984). The effects of target, age, and gender on use of power strategies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(6), 1391–1398. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.47.6.1391

- Cram, F., & Ng, S. H. (1999). Consumer socialization. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 48(3), 297–312. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.1999.tb00003.x

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. doi:10.1177/0149206305279602

- Crosbie-Burnett, M., Lewis, E. A., Sullivan, S., Podolsky, J., de Souza, R. M., & Mitrani, V. (2005). Advancing theory through research: The case of extrusion in stepfamilies. In V. Bengtson, et al. (Ed.), Sourcebook of family theory and research (pp. 213-238). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Crosbie-Burnett, M., & Giles-Sims, J. (1991). Marital power in stepfamilies: A test of normative-resource theory. Journal of Family Psychology, 4(4), 484–496. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.4.4.484

- Darley, W. F., & Lim, J. (1986). Family decision-making in leisure-time activities: An exploratory analysis of the impact of locus of control, child age influence factor and parental type on perceived child influence. Advances in Consumer Research, 13, 370–374.

- Davis, H. L. (1976). Decision making within the household. Journal of Consumer Research, 2(4), 241–260. doi:10.1086/jcr.1976.2.issue-4

- DeLeire, T., & Kalil, A. (2002). Good things come in threes: Single-parent multigenerational family structure and adolescent adjustment. Demography, 39(2), 393–413. doi:10.1353/dem.2002.0016

- DeLeire, T., & Kalil, A. (2005). How do cohabiting couples with children spend their money? Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(2), 286–295. doi:10.1111/jomf.2005.67.issue-2

- DeVault, M. L. (2003). Families and children. American Behavioral Scientist, 46(10), 1296–1305. doi:10.1177/0002764203046010002

- Dotson, M. J., & Hyatt, E. M. (2000). A comparison of parents’ and children’s knowledge of brands and advertising slogans in the United States: Implications for consumer socialization. Journal of Marketing Communications, 6(4), 219–230. doi:10.1080/135272600750036346

- Duckett, E., & Richards, M. H. (1995). Maternal employment and the quality of daily experience for young adolescents of single-mothers. Journal of Family Psychology, 9(4), 418–432. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.9.4.418

- Dunbar, N. E. (2004). Dyadic power theory: Constructing a communication-based theory of relational power. Journal of Family Communication, 4(1), 235–248. doi:10.1080/15267431.2004.9670133

- Duncan, G. J., & Rodgers, W. (1987). Single-parent families: Are their economic problems transitory or persistent? Family Planning Perspectives, 19(4), 171–178. doi:10.2307/2135169

- Dunn, J., Davies, L. C., O’Connor, T. G., & Sturgess, W. (2001). Family lives and friendships: The perspectives of children in step-, single-parent and non-step families. Journal of Family Psychology, 15(2), 272–287. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.15.2.272

- Edmondson, B. (1992). The changing American household. American Demographics: Desk Reference Series, 3(July), 2–3.

- Eggebeen, D. J. (2005). Cohabitation and exchanges of support. Social Forces, 83(3), 1097–1110. doi:10.1353/sof.2005.0027

- Ekstrom, K. M. (2007). Parental consumer learning or ‘keeping up with the children’. Journal of Consumer Behavior, 6(2–3), 203–217. doi:10.1002/cb.215

- Ekstrom, K. M., Tansuhaj, P. S., & Foxman, E. R. (1987). Children's influence in family decisions and consumer socialization: A reciprocal view. Advances in Consumer Research, 14, 283-287.

- Emerson, R. M. (1976). Social exchange theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 2, 335–362. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.02.080176.002003

- Epp, A. M., & Price, L. L. (2008). Family identity: A framework of identity interplay in consumption practices. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(1), 50–70. doi:10.1086/529535

- Fellerman, R., & Debevec, K. (1993). Kinship exchange networks and family consumption. Advances in Consumer Research, 20, 458–462.

- Flurry, L. A. (2007). Children’s influence in family decision-making: Examining the impact of the changing American family. Journal of Business Research, 60(4), 322–330. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.09.029

- Flurry, L. A., & Burns, A. C. (2005). Children’s influence in purchase decisions: A social power theory approach. Journal of Business Research, 58(5), 593–601. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2003.08.007

- Foxman, E. R., Tansuhaj, P. S., & Ekstrom, K. M. (1988). Adolescents and mothers perceptions of relative influence in family purchase decisions: Patterns of agreement and disagreement. Advances in Consumer Research, 15, 449–453.

- Foxman, E. R., Tansuhaj, P. S., & Ekstrom, K. M. (1989). Family members’ perceptions of adolescents’ influence in family decision-making. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(4), 482–491. doi:10.1086/jcr.1989.15.issue-4

- French, J. R. P., & Raven, B. (1959). The bases of social power. D. Cartwright (Ed.), Studies in social power (150–167). Ann Arbor, MI:Institute of Social Research.

- Galvin, K. M., & Brommel, B. J. (1999). Family communication: Cohesion and change (5th ed.). New York, NY: Addison-Wesley-Longman.

- Gerson, K. (2004). Understanding work and family through a gender lens. Community, Work & Family, 7(2), 163–178. doi:10.1080/1366880042000245452

- Giles-Sim, J., & Crosbie-Burnett, M. (1989). Adolescent power in step-father families: A test of normative-resource theory. Journal of Marriage and Family, 51(4), 1065–1078. doi:10.2307/353217

- Godwin, D. D., & Scanzoni, J. (1989). Couple decision making: Commonalities and differences across issues and spouses. Journal of Family Issues, 10(3), 291–310. doi:10.1177/019251389010003001

- Gotze, E., Prange, C., & Uhrovska, I. (2009). Children’s impact on innovation decision-making: A diary study. European Journal of Marketing, 43(1/2), 264–295. doi:10.1108/03090560910923328

- Graffe, D. R., & Lichter, D. T. (1999). Life course transitions of American children: Parental cohabitation, marriage and single-motherhood. Demography, 36(2), 205–217. doi:10.2307/2648109

- Grant, I. J., & Stephen, G. R. (2005). Communication culture: An examination of the buying behaviour of ‘tweenage’ girls and the key societal communicating factors influencing the buying process of fashion clothing. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 14(2), 101–114. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jt.5740173

- Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76–88. doi:10.5465/amr.1985.4277352

- Gregan-Paxton, J., & Roedder John, D. (1995). Are young children adaptive decision makers? A study of age differences in information search behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(4), 567–580. doi:10.1086/jcr.1995.21.issue-4

- Gronhoj, A. (2006). Communication about consumption: A family process perspective on ‘green’ consumer practices. Journal of Consumer Behavior, 5(6), 491–503. doi:10.1002/cb.198

- Grusky, O., Bonacich, P., & Webster, C. (1995). The coalition structure of the four-person family. Current Research in Social Psychology, 1(3), 16–29.

- Hamilton, K. (2009). Consumer decision-making in low-income families: The case of conflict avoidance. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 8(5), 252–267. doi:10.1002/cb.v8:5

- Hamilton, K., & Catterall, M. (2006). Consuming love in poor families: Children’s influence on consumption decisions. Journal of Marketing Management, 22(9–10), 1031–1052. doi:10.1362/026725706778935655

- Harradine, R., & Ross, J. (2007). Branding: A generation gap? Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 11(2), 189–200. doi:10.1108/13612020710751374

- Hernandez, D. J. (1986). Childhood in sociodemographic perspective. Annual Review of Sociology, 12, 159–180. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.12.080186.001111

- Hertz, R. (2006). Single by chance, mothers by choice: How women are choosing parenthood without marriage and creating the new American family. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Heslop, L. A., Madill, J., Duxbury, L., & Dowdles, M. (2007). Doing what has to be done: Strategies and orientations of married and single working mothers for food tasks. Journal of Consumer Behavior, 6(2–3), 75–93. doi:10.1002/cb.209

- Hetherington, M. E., Stanley-Hagan, M., & Anderson, E. R. (1989). Marital transitions: A child’s perspective. American Psychologist, 44(2), 303–312.

- Howard, J., & Sheth, J. N. (1969). The theory of buyer behavior. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

- Interis, M. (2011). On norms: A typology with discussion. Journal of Economics and Sociology, 70(2), 424–438. doi:10.1111/j.1536-7150.2011.00778.x

- John, D. R. (1999). Consumer socialization of children: A retrospective look at twenty-five years of research. Journal of Consumer Research, 26(3), 183–213. doi:10.1086/jcr.1999.26.issue-3

- John, D. R. (2008). Stages of consumer socialization: The development of consumer knowledge, skills, and values from childhood to adolescence. In C. P. Haugtvedt, P. M. Here, & F. Kardes (Eds.), The handbook of consumer psychology (pp. 221–246). London, UK: Taylor & Francis, Inc.

- John, D. R., & Lakshmi-Ratan, R. (1992). Age differences in children’s choice behavior: The impact of available alternatives. Journal of Marketing Research, 29(2), 216–226. doi:10.1177/002224379202900206

- Kaufman, G. (2000). Do gender role attitudes matter? Family formation and dissolution among traditional and egalitarian men and women. Journal of Family Issues, 21(1), 128–144. doi:10.1177/019251300021001006

- Kim, C., & Lee, H. (1997). Development of family triadic measures for children’s purchase influence. Journal of Marketing Research, 34(3), 307–321. doi:10.1177/002224379703400301

- Kim, C., Lee, H., & Tomiuk, M. A. (2009). Adolescent perceptions of family communication patterns and some aspects of their consumer socialization. Psychology & Marketing, 26(10), 888–907. doi:10.1002/mar.20304

- Kourilsky, M., & Murray, T. (1981). The use of economic reasoning to increase satisfaction with family decision-making. Journal of Consumer Research, 8(2), 183–188. doi:10.1086/jcr.1981.8.issue-2

- Kurdek, L. A., & Fine, M. A. (1993). Parent and nonparent residential family members as providers of warmth and supervision to young adolescents. Journal of Family Psychology, 7(2), 245–249. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.7.2.245

- Lang, K., & Zagorsky, J. L. (2000). Does growing up with a parent absent really hurt? Journal of Human Resources, 36(2), 253–273. doi:10.2307/3069659

- Lawler, E. J., & Thye, S. R. (1999). Bringing emotions into social exchange theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 2, 217–244. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.25.1.217

- Lee, C. K. C., & Beatty, S. E. (2002). Family structure and influence in family decision-making. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 19(1), 24–41. doi:10.1108/07363760210414934

- Lee, C. K. C., & Collins, B. A. (2000). Family decision-making and coalition patterns. European Journal of Marketing, 34(9/10), 1181–1198. doi:10.1108/03090560010342584

- Lussier, G., Deater-Deckard, K., Dunn, J., & Davies, L. (2002). Support across two generations: Children’s closeness to grandparents following parental divorce and remarriage. Journal of Family Psychology, 16(3), 363–376. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.16.3.363

- Maccoby, E. E., & Martin, J. A. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In P. H. Mussen & M. E. Hetherington (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Socialization, personality, and social development (pp. 1–101). New York, NY: Wiley.

- Mandrik, C. A., Fern, E. F., & Bao, Y. (2005). Intergenerational influence: Roles of conformity to peers and communication effectiveness. Psychology & Marketing, 22(10), 813–832. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1520-6793

- Mangelburg, T. F., Grewal, D., & Bristol, T. (1999). Family type, family authority relations, and adolescents’ purchase influence. Advances in Consumer Research, 26, 379–384.

- Marquis, M. (2004). Strategies for influencing parental decisions on food purchasing. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 21(2), 134–143. doi:10.1108/07363760410525696

- McDermott, L., O’Sullivan, T., Stead, M., & Hastings, G. (2006). International food advertising, pester power and its effects. International Journal of Advertising, 25(4), 513–540. doi:10.1080/02650487.2006.11072986

- McDonald, G. W. (1980). Family power: The assessment of a decade of theory and research, 1970–79. Journal of Marriage and Family, 42(4), 841–854. doi:10.2307/351828

- McLanahan, S., & Percheski, C. (2008). Family structure and the reproduction of inequalities. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 257–276. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134549

- Moore, E. S., Wilkie, W. L., & Lutz, R. J. (2002). Passing the torch: Intergenerational influences as a source of brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 66(2), 17–37. doi:10.1509/jmkg.66.2.17.18480

- Moore, M. R. (2008). Gendered power relations among women: A study of household decision-making in black, lesbian stepfamilies. American Sociological Review, 73(2), 335–356. doi:10.1177/000312240807300208

- Moriarty, P. H., & Wagner, L. D. (2004). Family rituals that provide meaning for single-parent families. Journal of Family Nursing, 10(2), 190–210. doi:10.1177/1074840704263985

- Moschis, G. P. (1985). The role of family communication in consumer socialization of children and adolescents. Journal of Consumer Research, 11(4), 898–913. doi:10.1086/jcr.1985.11.issue-4

- Moschis, G. P., & Churchill, G. A., Jr. (1978). Consumer socialization: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 15(4), 599–609. doi:10.1177/002224377801500409

- Mulkey, L. M., Crain, R. L., & Harrington, A. J. (1992). One-parent households and achievement: Economic and behavioral explanations of a small effect. Sociology of Education, 65(1), 48–65. doi:10.2307/2112692

- Norton, A. J., & Glick, P. C. (1986). One parent families: A social and economic profile. Family Relations, 35(1), 9–17. doi:10.2307/584277

- Omori, M. (2010). Household expenditures on children, 2007–08. Monthly Labor Review, 133(9), 3–16.

- Palan, K. M., & Wilkes, R. E. (1997). Adolescent-parent interaction in family decision-making. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(2), 159–169. doi:10.1086/jcr.1997.24.issue-2

- Park, J., Tanushaj, P. S., & Kolbe, R. H. (1991). The role of love, affection, and intimacy in family decision research. Advances in Consumer Research, 18, 651–656.

- Pelaez, M., Field, T., Pickens, J. N., & Hart, S. (2008). Disengaged and authoritarian parenting behavior in depressed mothers with toddlers. Infant Behavior and Development, 31, 145–148. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2007.06.002

- Peyton, R. M., Pitts, S. T., & Kamery, R. H. (2004). The family decision-making process: A review of significant consumer satisfaction/dissatisfaction models. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 8(1), 75–88.

- Qualls, W. J. (1988). Toward understanding the dynamics of household decision conflict behavior. Advances in Consumer Research, 15, 442–448.

- Ram, B., & Hou, F. (2003). Changes in family structure and child outcomes: Roles of economic and familial resources. Policy Studies Journal, 31(3), 309–330. doi:10.1111/psj.2003.31.issue-3

- Rindfleisch, E., Burroughs, J. E., & Denton, F. (1997). Family structure, materialism, and compulsive consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 23(4), 312–325. doi:10.1086/209486

- Risman, B. J. (1998). Gender vertigo: American families in transition. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Robinson, C., Mandelco, B., Olsen, S. F., & Hart, C. H. (1995). Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting practices: Development of a new measure. Psychological Reports, 77, 819–830. doi:10.2466/pr0.1995.77.3.819

- Rodman, H. (1972). Marital power and the theory of resources in cultural context. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 3, 50–69.

- Rummel, A., Howard, J., Swinton, J. M., & Seymour, B. D. (2001). You can’t have that! A study of reactance effects and children’s consumer behavior. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 8(1), 38–45. doi:10.1080/10696679.2000.11501859

- Russell, R., & Tyler, M. (2002). Thank heaven for little girls: ‘girl heaven’ and the commercial context of feminine childhood. Sociology, 3, 619–637. doi:10.1177/0038038502036003007

- Scanzoni, J. H., & Szinovacz, M. E. (1980). Family decision-making: A developmental sex-role model. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

- Seltzer, J. A. (1994). Consequences of marital dissolution for children. Annual Review of Sociology, 20, 235–266. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.20.080194.001315

- Sheth, J. N. (1974). A theory of family buying decisions. In J. Sheth (Ed.), Models of buyer behavior: Conceptual, quantitative, and empirical (pp. 17–33). New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- Spiggle, S. (1998). Creating the frame and the narrative representing consumers voices views and visions. (B. Stern, Ed.). London: New York Routledge.