Abstract

Though Organizational Citizenship Behavior is unenforceable by the organization, it promotes the effective functioning of the organization through a discretionary individual behavior of employees. In this regard, Organizational Citizenship Behavior contributes to the organization in many ways. However, due to cultural differences, dimensions of Organizational Citizenship Behavior may differ from country to country. In line with that, this paper explores the creation of an instrument for assessing Organizational Citizenship Behavior based on a study done in a Hindi-English environment involving public and private companies in the banking, finance, and insurance industry in India. Taking into account the high turbulence and considerable staff attrition in the banking, finance, and insurance sector that additionally increases pressure on employees to be effective performers within a stressful environment, this study intended to examine dimensions of Organizational Citizenship Behavior in this industry in New Delhi and the National Capital Territory of India. The study has used a descriptive research design and the quantitative approach. Specific items for the Organizational Citizenship Behavior assessment were selected for their reliability and quality using exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis. The specific steps involved in these processes and resulting item inclusion are discussed in detail.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) is positive and constructive voluntary behavior which makes better work culture by creating healthy peer interactions and relationships. This article is aimed at improving an existing scale of OCB by testing it in an Indian workplace environment under the domain of Banking, Financial services and Insurance (BFSI) industry. Existing studies have been performed in Western environments but this is the first study (of its kind) to be performed in Indian organizations from the BFSI sector. A physical survey was administered on 432 employees, spread across six different organizations of both Public and Private BFSI companies. The results led to deletion of some of the items in the exiting tool and a new modified tool is proposed. The modified tool could be used by researchers and HR practitioners to study the concept of OCB in Indian environments and also exploratory research in industries other than BFSI.

1. Introduction

Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB), though unenforceable by the organization, promotes the effective functioning of the organization through a discretionary individual behavior of employees and contributes to the organization in many ways.

Individuals that display OCB are willing to cooperate and enlarge their engagement beyond the set duties and rewards provided by the organization with the intention of achieving more significant goals. Thus, any organization can aim to increase OCB of its employees. However, to be able to do that, it must be familiar with the dimensions of OCB that are influenced, among other factors, by national culture.

In this regard, the purpose of this study was to examine OCB dimensions in the Indian context in order to create an instrument for assessing OCB in a Hindi-English environment. The study was conducted in the banking, finance, and insurance industry in India.

2. Organizational citizenship behavior

2.1. The concept of organizational citizenship behavior

Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) implies that an employee’s behavior is compatible with an organization’s goals and policies. Although the concept has evolved over time and its definition has been varied, its essence, antecedents, and dimensions have remained relatively unchanged.

One of the earliest mentions of Organizational Citizenship Behavior is the work of Chester Barnard in the 1930s and Katz and Kahn in the 1960s who perceived that extra role behavior of employees is the display of their selfless and voluntary behaviors towards the achievement of organizational objectives (Katz & Kahn, Citation1966). Yet, the term “Organizational citizenship behavior” was first coined by Bateman and Organ (Citation1983) who defined it as a discretionary individual behavior that promotes the effective functioning of an organization, although it is not explicitly recognized by the formal reward system (Organ, Citation2005).

OCB has theoretical foundations in Social Exchange Theory that explains the work behavior of individuals based on trust. As a result of good will extended to the employees, workers develop positive relationships with each other and display a positive behavior within the company. Employees who benefit with such positive experiences in the organization generally tend to reciprocate this feeling or experiences by contributing towards the organizational objectives (Blau, Citation1964). In line with that, an individual is willing to cooperate and enlarge its engagement (Cinar, Karcioglu, & AlIogullari, Citation2013) beyond the set duties and rewards provided by the organization with the intention of achieving more significant goals (Veličkovska, Citation2017). OCB can be also reflected in an employee voluntarily assisting other employees in their work in order to promote the excellence of the employer without expecting a reward for that (Cem-Ersoy, Derous, Born, & Van Der Molen, Citation2015). OCB also reflects other work-related employee behaviors that are discretionary and supportive of the employee’s social and psychological environment (Zeinabadi & Salehi, Citation2011).

Hence, OCB is based on the attitudes of an individual toward job requirements and shows an individual’s desire and enthusiasm to exceed the company’s expectations in a bid to enhance the output of the company outside the outlined duties (Cem-Ersoy et al., Citation2015; Owen, Pappalardo, & Sales, Citation2000). According to Organ (Citation1988), OCB is exhibited by employees who are highly committed to an organization and who are the exhibitors of the “good soldier syndrome.” Positive OCB is, thus, characterized by employees engaging in extra-role activities that are not necessarily stipulated in their job descriptions, but that are in favor of organizational interests and provide the individual’s concerned intrinsic motivation.

2.2. Antecedents of organizational citizenship behavior

Organizational Citizenship Behavior has been a subject of many studies that has resulted in more than 30 different forms of OCB related to individual and organizational levels’ outcomes (Podsakoff, Whiting, Podsakoff, & Blume, Citation2009).

The most significant antecedents of OCB on the individual level are job satisfaction and job embeddedness, employee engagement, organizational commitment, and self-efficacy, while antecedents of OCB related to the organizational level are human resource activities, reduced costs, increased productivity and efficiency, transformational leadership, culture, customer satisfaction, etc. Each of these antecedents increases OCB, which in return positively affects antecedents and has an additional positive impact on OCB.

The more employees are satisfied with their jobs, the more they are engaged and embedded to their organization and thus more willing to work beyond formal expectations (Cho & Ryu, Citation2009; Huang, You, & Tsai, Citation2012; Sridhar & Thiruvenkadam, Citation2014). Similarly, the high organizational commitment, especially affective commitment is positively related to OCB dimensions altruism and compliance (Zheng, Zhang, & Li, Citation2012). Also, individuals with the higher perception of their capabilities are more likely to be proactive and to engage in activities that go beyond their formal job specification, for example to engage in voluntary work (Brown, Hoye, & Nicholson, Citation2012).

Furthermore, perceptions of organizational justice and fairness of human resource activities, especially the evaluation and rewarding of job performance also positively influence OCB (Fu, Flood, Bosak, Morris, & O’Regan, Citation2013). In addition, transformational leadership, as well as organizational values that reflect employee inner needs, beliefs and aspirations additionally encourage employees to perform duties with the highest level of efficiency and righteousness (Jha, Citation2014) and find meaningfulness in their work (Milliman, Czaplewski, & Ferguson, Citation2003). An increased OCB reduces costs and increases productivity, efficiency and customer satisfaction (Ocampo et al., Citation2018), which in return further motivates employees to increase OCB and the organization to improve its HR practices.

Thus, as most studies have already confirmed, OCB has a positive impact on organizational results as these extra efforts of employees are neither formally required nor rewarded explicitly, but employees assume such responsibilities voluntarily as they feel as a part of the organization.

2.3. Dimensions of organizational citizenship behavior

What are considered as the dimensions of OCB vary among researchers. According to Smith, Organ, and Near (Citation1983), altruism and generalized compliance are two main dimensions of OCB, while Organ (Citation1988) identified five dimensions of OCB—altruism, conscientiousness, civic virtue, courtesy, and sportsmanship that later (Organ, Citation1990) expanded with peace keeping and cheer leading. Based on Organ’s five dimensions, Graham (Citation1989) put forward interpersonal helping, taking individual initiative, industriousness, and loyal boosterism as four dimensions of OCB. Later Graham (Citation1991) narrowed the dimensions to three—organizational obedience, organization commitment, and organization participation, while Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Paine, and Bachrach (Citation2000) identified helpful behavior, sportsmanship, loyalty to the organization and compliance, civic virtue, and taking individual initiative including self-development.

However, although studies have identified different dimensions of OCB, the most relevant dimensions of OCB are still those originally suggested by Organ (Citation1988)—altruism, civic virtue, conscientiousness, courtesy, and sportsmanship. Altruism refers to voluntary workers’ actions that help others to resolve work-related problems and increase their performance, thus showing selfless concern for the well-being of other workers (Organ, Citation1988). Civic virtue is related to employee interest and its voluntary participation in organizational social and political activities, such as attendance at meetings, staying abreast of organizational developments, and being good corporate citizens (Deluga, Citation1998; Organ, Citation1988).

Conscientiousness demonstrates a pattern of going well beyond minimally required role and task requirements. It refers to an employee’s genuine acceptance of and compliance with the organizational workplace rules, regulations, and procedures, which results in performance over and above the levels of required basic performance levels (Organ, Citation1988). Courtesy involves the discretionary enactment of thoughtful and considerate behaviors that prevent work-related problems for others. It means that employees have respect for their co-workers and engage in behavior meant to reduce interpersonal conflict (Organ, Citation1990).

Finally, sportsmanship is an employee’s willingness to tolerate expected inconvenience and getting work done without complaining (Organ, Citation1988). It leads to organizational improvement and maintaining a positive attitude in the face of problems (Castro, Armario, & Ruiz, Citation2004; Mohammad, Habib, & Mohammad, Citation2011).

2.4. Cultural context of organizational citizenship behavior

Researchers also noted that OCB conceptualization and dimensions may vary from culture to culture (Bakhshi, Kumar, & Kumari, Citation2009; Vaijayanthi, Shreenivasan, & Roy, Citation2014). While some OCB dimensions are similar across cultures, others are specific to a certain culture.

For example, while in Taiwan are relevant five dimensions of OCB—altruism, civic virtues and conscientiousness, protecting company resources and interpersonal harmony (Farh, Earley, & Lin, Citation1997), only three of them—altruism, civic virtues, and conscientiousness are applicable in western contexts. Similarly, sportsmanship and courtesy, identified as part of one’s job role by employees in Hong Kong and Japan, were not accorded the same status by employees in USA and Australia (Gelfand, Aycan, Erez, & Leung, Citation2017).

In line with context sensitivity of OCB dimensions, authors tried to identify dimensions that are similar in different cultural contexts. On the basis of nine dimensions of OCB identified in China, Farh, Zhong, and Organ (Citation2004) proposed a concentric model of dimensions of OCB with the innermost circle representing dimensions related to the self, the group, organization, and society respectively. The “self” in China includes self-learning, taking initiative, and keeping the workplace clean, while the group circle consists of interpersonal harmony and helping co-workers. The organization circle includes protecting and saving company resources, voice and participation in group activities, and the society circle consists of social welfare participation, compliance with social norms and promoting company image. However, in the Western-based studies, only a few dimensions are observed—taking initiative (resembling conscientiousness), helping co-workers (similar to altruism), voice and participation in the group activity (similar to civic virtue), and promoting a company’s image (similar to loyalty), while others dimensions of OCB are specific for the Chinese collectivistic culture (Farh et al., Citation2004).

Given that Indian culture is also collectivistic (Hofstede, Citation1984), it would be expected that conceptualization of OCB in the Indian cultural context extends beyond the “self” within the organization to the self in the community (Bakhshi et al., Citation2009). Some studies (Gupta, Kumar, & Singh, Citation2012) concluded that Organ’s five OCB dimensions are not applicable to Indian’s knowledge-based business context. Instead, they proposed three other dimensions for Indian culture—organization-orientation that includes helping, sportsmanship and civic virtue, punctuality that refers to adherence to the organization’s work schedules, and individual-orientation that refers to courtesy. On the other hand, some studies (Vaijayanthi et al., Citation2014) excluded sportsmanship as appropriate OCB dimension for Indian’s culture, while others (Shanker, Citation2016) observed all five dimensions of OCB in Indian organizations—sportsmanship, altruism, civic virtue, courtesy, and conscientiousness.

Taking into account all previously stated, this study has combined OCB dimensions found by Farh et al. (Citation2004), Gupta et al. (Citation2012), and Shanker (Citation2016) to identify whether altruism, civic virtue, sportsmanship, conscientiousness, and courtesy are applicable in Indian culture. The aim of the study has been to propose an instrument for assessing organizational citizenship behavior in a Hindi-English environment in six public and private companies in the banking, finance, and insurance industry (BFSI) in India.

Although this industry in India has experienced rapid growth in the last ten years (Shah & Tyagi, Citation2017), at the same time, it has become increasingly volatile due to rapid changes in the environment through technological advances. Even this is a global phenomenon, BFSI in India experiences large attrition in talent management due to the uncertainty of making decisions in a complex work environment (Uhl-Bien & Marion, Citation2009), which adversely affects employee retention and performance. Therefore, identifying OCB dimensions in the Indian cultural context should enable organizations in the BFSI sector in India to become competitive and to improve the selection and retention of talent management.

3. Method

3.1. Sample

The target population of the study was employees from public and private banks and insurance organizations located in New Delhi (the capital of India), India and the National Capital Territory that includes adjoining cities from the states of Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Haryana on the geographical border of New Delhi.

The study has focused on Indian locations with diverse cultural backgrounds in order to increase the external validity of the study by including individuals whose views diverge based on different perspectives and cultural backgrounds. This study used purposive sampling, a non-probability sampling technique as the technique of selecting samples where each of the organization were approached through a higher level manager who distributed the questionnaire to her or his subordinates.

A total of 500 questionnaires were distributed across the different organizations and 470 filled questionnaires were returned. Among the ones returned, 37 were found redundant and were discarded. The final sample size was 433.

3.2. Participants

As presented in Table 1, the participants in the study were employees of two banks, one private (Bank Priv1) and one public (Bank Pub1), and four insurance companies, two public (IC Pub1, IC Pub2) and two private (IC Priv1, IC Priv2). In total, there were 48.3% of respondents from the private sector and 51.7% of respondents from the public sector (Table 2).

The employees selected as respondents have been those who are employed on a permanent and on-roll basis and have been in the firm for at least one year in order to ensure a higher level of accuracy in their responses. Those who participated in the research were employees at the executive level in private firms and Class III and above in the public-sector organizations.

Most of the participants were male (72.7%), married people (77.6%), aged between 25–35 years (30.9%), 35–45 years (29.3%) and 45–55 years (25.9%). They were mostly Post-Graduate (61.0%) or Graduate (31.6%), with total work experience of 1–5 years (16.9%), 6–10 years (27.0%), 11–15 years (13.4%), 16–20 years (13.9%), or more than 20 years (28.8%).

3.3. Measures

The questionnaire has been closed-ended to allow for efficiency and effectiveness in collecting responses from the sample population and provide ease of comparison between answers (Reja, Manfreda, Hlebec, & Vehovar, Citation2003). It has been used a Likert-type scale that requires that the respondents indicate the degree of agreement or disagreement with the items measuring the dimensions of OCB. Each item had five response categories: (1) strongly disagree (2) disagree (3) neither agree nor disagree (4) agree (5) strongly agree. The negative items were scored by reversing the scale.

The questionnaire included the demographic variables and five dimensions of OCB. The demographic variables in the study were gender (three options), marital status (three options), age (five ranges), educational qualification (four options), and total work experience (five ranges). Organizational Citizenship Behavior was measured with a 24-item scale, containing five factors—conscientiousness (five items), sportsmanship (five items), civic virtue (four items), courtesy (four items), and altruism (six items) (Organ, Citation1988; Podsakoff et al., Citation2009).

Conscientiousness was defined as a pattern of going well beyond minimally required role and task requirements. Sportsmanship was defined as a willingness of employees to tolerate expected inconvenience and getting work without complaining. Civic virtue was defined as voluntary participation in and support of organizational functions of both a professional and social nature, while courtesy was defined as the discretionary enactment of thoughtful and considerate behaviors that prevent work-related problems for others. Altruism was defined as voluntary actions that help a fellow employee in work-related problems.

3.4. Procedures

Primary data for the study was collected in 2018. The questionnaire was physically distributed to the respondents. All participants have needed to be willing to participate in the study and to complete the entire questionnaire. The questionnaires were distributed in their entirety and were collected later, as per the convenience of the respondents and to eliminate any issues from the management due to the hindrance of employees from carrying out their duties.

4. Results

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS 25.0 and IBM AMOS 25 statistics packages. Besides descriptive statistics, the study included comparative analysis of private and public companies with respect to constructs measured in the study and reliability analysis of internal consistency of the study variables. Explanatory and confirmatory factor analysis was finally performed, which confirmed the construct validity of components of the study.

The participants of the study reported moderately high levels of conscientiousness with a mean score of 4.24 and a standard deviation of .50 indicating that the participants of public and private company workers perform well beyond minimally required role and task requirements. The overall mean score of the participants’ sportsmanship was 4.38 with a standard deviation of .67, suggesting that participants of the study are willing to tolerate expected inconvenience and completing work without complaining. Also, the participants reported a slightly high score of civic virtue with the overall mean score of 3.99 and a standard deviation of .66, indicating that, in general, they perform voluntary tasks and participation in, and support of organizational functions of both a professional and social nature. The participants of the study also reported a moderately high score of courtesy (M = 4.25, SD = .48), indicating that exhibit discretionary enactment of thoughtful and considerate behaviors that prevent work-related problems for coworkers. They also had a high score of altruism (M = 4.14, SD = .48), thus showing their willingness to voluntary help their fellow employees in work-related problems.

As shown in Table , the research has found a statistically significant difference at the p < .05 level in sportsmanship [F(1, 431) = 16.46, p = .00], civic virtue [F(1, 431) = 17.14, p = .00], altruism [F(1, 431) = 18.17, p = .00], and organizational citizenship behavior [F(1, 431) = 22.57, p = .00] scores for both groups of companies—private and public. However, despite reaching statistical significance, the actual difference in the mean scores between the groups, calculated by eta squared Cohen’s (Citation1988), was just .04 for sportsmanship, civic virtue and altruism, and .05 for organizational citizenship behavior. The mean score for private companies (M = 4.28, SD = .31) was significantly different from public companies (M = 4.12, SD = .41), implying that private company employees go above and beyond the call of duty to aid fellow workers in order to achieve organizational goals more than public company workers.

Table 1. The sample across the different companies

Table 2. Type of organizations

Table 3. ANOVA results of organizational citizenship behavior and its components with respect to company type

Since the results of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (0.86) and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (Sig<0.5) have shown that the data is suitable for factor analysis, Kaiser’s criterion was used to determine the number of components. As shown in Table , there were 6 components that have recorded eigenvalues above 1.

Table 4. Total variance explained of organizational citizenship behavior components—first trial

However, the analysis of the rotated component matrix (Table ) revealed that all the items, except OCB_Altruism20 item, load strongly, above 0.4. Also, the reliability analysis has shown that OCB_Courtesy15 needs to be eliminated from further analysis. Hence, when these two items were omitted, components 6 remained only two items. Thus, it was decided to eliminate OCB_Cons1 and OCB_Cons2 items. However, unexpectedly, OCB_Altruism19 was loaded to component 4 instead of component 3. In line with that, it was decided to run the second explanatory factor analysis (Table ) without component 6 and OCB_Altruism19 item.

Table 5. Rotated component matrixa of organizational citizenship behavior components—first trial

Table 6. Total variance explained of organizational citizenship behavior components—second trial

As shown in Table , the second explanatory factor analysis trial revealed the presence of five components with eigenvalues exceeding 1, explaining 16.46%, 12.96%, 10.81%, 10.37% and 9.54% of the variance respectively, adding up 60.14% of the variance in total.

Also, the rotated component matrix analysis suggested to omit 5 items—OCB_Altruism19, OCB_Altruism20, OCB_Courtesy15, OCB_Cons1, and OCB_Cons2 (Appendix 2). Thus, 19 OCB items remained (Appendix 1) for the second trial of the Principal Component Analysis with a varimax rotation, where all the item loadings were quite strong, above 0.40 (Table ). Hence, it was decided to retain all the five components.

Table 7. Rotated component matrixa of organizational citizenship behavior components—second trial

However, the results of the confirmatory factor analysis of OCB indicated that there was not a good fit between the CFA model and the data, suggesting that the specified CFA model is not acceptable (Jöreskog & Sörbom, Citation1993). Although most of the organizational citizenship behavior items had high estimate values, which indicates a high correlation with corresponding latent variable, there were several items with low values—OCB_Altruism19, OCB_Altruism20, OCB_Courtesy15, OCB_Cons1, and OCB_Cons2.

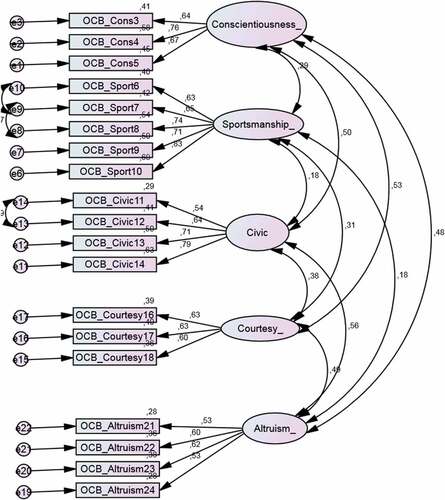

Thus, taking into account reliability analysis and explanatory factor analysis, together with the suggestions of applied researchers (Cliff & Hamburger, Citation1967; Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, Citation2009; Stevens, Citation2002), these items are eliminated (Appendix 2), while the remaining 19 items are retained (Appendix 1), which has ensured a very good fit to the data in the second confirmatory factor analysis presented in Table .

Table 8. Model fit indices of the second CFA for organizational citizenship behavior

Based on all analyses conducted in the study, the proposed modified model presented in Figure is highly supported by the sample data, and thus suitable for the Indian context.

5. Discussion

Considering that the BFSI sector in India faces high turbulence and considerable staff attrition that additionally increases pressure on employees to be effective performers within a stressful environment, this study intended to examine and explain dimensions of OCB in the BFSI sector in New Delhi and NCT, India with the aim to propose the instrument for the assessment of OCB in the Hindi-English environment. The study has used a descriptive research design and a quantitative approach.

As results have shown, public and private company participants displayed moderately high scores of conscientiousness (4.24), sportsmanship (4.38), and courtesy (4.25), a slightly high score of civic virtue (3.99), and a high score of altruism (4.14). However, attendance at work above the norm is higher for private company participants (M = 4.27 SD = .69) than for public company participants (M = 4.04 SD = .99). Also, private company participants take fewer breaks (M = 4.34 SD = .53) than public company workers (M = 4.01 SD = .84), but both obey the rules and regulations of the organization even when no one is watching them. Furthermore, private company participants (M = 4.51 SD = .59) have higher sportsmanship behaviors than public company participants (M = 4.25 SD = .72).

Also, although, in general, participants perform voluntary tasks and support organizational functions, private company workers (M = 4.12 SD = .67) are more involved in the events of the organization than public company workers (M = 3.87 SD = .62). They also attend non-mandatory meetings that are considered important (M = 4.04, SD = 0.90), pay more attention to announcements and memos of the organization, and dedicate more energy and time to their companies than public company participants. However, although both private (M = 4.27 SD = .41) and public (M = 4.23 SD = .54) company participants behave in a way that prevents work-related problems, private company workers (M = 4.24 SD = .43) displayed the higher level of altruistic behavior than public company workers (M = 4.05 SD = .49).

Hence, although all the participants, in general, perform well beyond minimally required role and task requirements, tolerate expected inconvenience, prevent work-related problems for coworkers, support organizational functions, and voluntary help coworkers in work-related problems, private company employees have shown greater OCB than public company workers.

Therefore, this study not only confirmed previous research that depicts OCB as a five-factor model (Jepsen & Rodwell, Citation2006), but also extended the research in this area by testing the model in a non-western context. In line with the findings of the research, the modified model is proposed for the assessment of OCB dimensions in a Hindi-English environment that can help companies to apply the proper HR policies that will positively influence OCB and thus increase work effort, performance, and commitment of the employees. Concerning that all OCB components used in the instrument are derived from the existing literature specific to the western context and all of them, except one, have been retained, this instrument can also be used in other contexts, besides Indian, but they should have a similar culture to India due to excluded items. Also, the instrument would probably be applicable to other industries due to similar cultural features, but due to different personal characteristics of employees and various industry-specific external environments, further analysis should be performed.

5.1. Limitations, future research directions, and implications

Although the study has used a large sample size (n = 433) and ensured the high replicability of the research due to the quantitative design of this study, it also has a few limitations.

Despite the fact that all responses were anonymous, there is still a possibility that some of the respondents gave socially desirable responses (Furnham, Citation1986) or responded in a neutral way even if they had negative feelings about their employers. In addition, although the study has ensured the anonymity of respondents, employees might have feared that their employers will dismiss them if they discover their responses to the questions, particularly in the private sector of the BFSI industry. Furthermore, the study was conducted at one particular moment in time due to its cross-sectional nature, which means that these results might not be the same if the study was repeated at a different time.

Hence, more research is needed to confirm the temporal continuity of the study’s results. Future research may use a longitudinal approach to determine whether the dimensions of OCB are stable over time. Future studies can also examine the impact of OCB on individual work performance or which HR policies have the greatest impact on OCB. Therefore, this study helps researchers to further examine this area, but also enables companies to identify OCB dimensions in the Indian context and thus, through different HR policies, to direct employee behavior towards achieving the long-term goals of the organization.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Shaad Habeeb

Shaad Habeeb The author is a PhD in the area of Organizational Behavior and is currently working as Assistant Professor in the field of HR and OB at School of Management & Business Studies, Jamia Hamdard (University), New Delhi, India. His prime area of interests are Spirituality, Workplace Spirituality, Organizational Behavior and the behavioral aspects of employee performance. The present article links the author’s interest to provide management consultancy to interested organizations to improve the performance oriented behavior of the employees.

References

- Bakhshi, A., Kumar, K., & Kumari, A. (2009). National culture and organizational citizenship behavior: Development of a scale. In Singh, S. (Eds.), Organisation behaviour (pp. 209-226). New Delhi: Global Publishing House.

- Bateman, T. S., & Organ, D. W. (1983). Job satisfaction and the good soldier: The relationship between affect and employee citizenship. Academy of Management Journal, 26(4), 587–20.

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York: J. Wiley.

- Brown, K. M., Hoye, R., & Nicholson, M. (2012). Self-esteem, self-efficacy, and social connectedness as mediators of the relationship between volunteering and well-being. Journal of Social Service Research, 38(4), 468–483. doi:10.1080/01488376.2012.687706

- Castro, C., Armario, E. M., & Ruiz, D. M. (2004). The influence of employee organizational citizenship behavior customer loyalty. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 15(1), 27–53. doi:10.1108/09564230410523321

- Cem-Ersoy, N., Derous, E., Born, M., & Van Der Molen, H. (2015). Antecedents of organizational citizenship behavior among Turkish white-collar employees in the Netherlands and Turkey. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 49(1), 68–79. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.06.010

- Cho, Y. B., & Ryu, J. R. (2009). Organizational citizenship behaviors in relation to job embeddedness, organizational identification, job performance, voluntary turnover intention in Korea. International Business & Economics Research Journal, 8(7), 51–68.

- Cinar, O., Karcioglu, F., & AlIogullari, Z. D. (2013). The relationship between organizational silence and organizational citizenship behavior: A survey study in the province of Erzurum, Turkey. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 99(1), 314–321. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.499

- Cliff, N., & Hamburger, C. D. (1967). The study of sampling errors in factor analysis by means of artificial experiments. Psychological Bulletin, 68, 430–445.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Deluga, R. J. (1998). Leader-member exchange quality and effectiveness ratings: The role of subordinate-supervisor conscientiousness similarity. Group & Organization Management, 23(2), 189–216. doi:10.1177/1059601198232006

- Farh, J. L., Earley, P. C., & Lin, S. C. (1997). Impetus for action: A cultural analysis of justice and organizational citizenship behavior in Chinese society. Administrative Science Quarterly, 421–444. doi:10.2307/2393733

- Farh, J. L., Zhong, C. B., & Organ, D. W. (2004). Organizational citizenship behavior in the People’s Republic of China. Organization Science, 15(2), 241–253. doi:10.1287/orsc.1030.0051

- Fu, N., Flood, P. C., Bosak, J., Morris, T., & O’Regan, P. (2013). Exploring the performance effect of HPWS on professional service supply chain management. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 18(3), 292–307. doi:10.1108/SCM-04-2012-0118

- Furnham, A. (1986). Response bias, social desirability and dissimulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 7(3), 385–400. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(86)90014-0

- Gelfand, M. J., Aycan, Z., Erez, M., & Leung, K. (2017). Cross-cultural industrial organizational psychology and organizational behavior: A hundred-year journey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 514. doi:10.1037/apl0000186

- Graham, J. W. (1989). Organizational citizenship behavior: Construct redefinition, operationalization, and validation, unpublished working paper. Chicago, IL: Loyola University of Chicago.

- Graham, J. W. (1991). An essay on organizational citizenship behavior. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 4(4), 249–270. doi:10.1007/BF01385031

- Gupta, M., Kumar, V., & Singh, M. (2012). Creating satisfied employees through workplace spirituality: a study of the private insurance sector in Punjab (India). Journal of Business Ethics, 122(1), 79–88. doi:10.1007/s10551-013-1756-5

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate data analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Hofstede, G. (1984). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values (Vol. 5). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Huang, C. C., You, C. S., & Tsai, M. T. (2012). A multidimensional analysis of ethical climate, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Nursing Ethics, 19(4), 513–529. doi:10.1177/0969733011433923

- Jepsen, D., & Rodwell, J. (2006). A side by side comparison of two organizational citizenship behavior models and their measures: Expanding the construct domain’s scope. Proceedings of the 11Th Annual Conference of Asia-Pacific Decision Sciences Institute Conference (pp. 381–384). Kowloon, Hong Kong: Asia-Pacific Decision Sciences Institute. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.12.005

- Jha, S. (2014). Transformational leadership and psychological empowerment: Determinants of organizational citizenship behavior. South Asian Journal of Global Business Research, 3(1), 18–35. doi:10.1108/SAJGBR-04-2012-0036

- Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1993). LISREL 8: Structural equation modeling with the SIMPLIS command language (pp. 296–298). Chicago: Scientific Software International. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 16 (Series B).

- Katz, D. & Kahn, R. L. (1966). The social psychology of organizations. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- Milliman, J., Czaplewski, A. J., & Ferguson, J. (2003). Workplace spirituality and employee work attitudes: An exploratory empirical assessment. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 16(4), 426–447. doi:10.1108/09534810310484172

- Mohammad, J., Habib, F. Q., & Mohammad, M. A. (2011). Job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior: An empirical study at higher learning institutions. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 16(2), 149–165.

- Ocampo, L., Acedillo, V., Bacunador, A. M., Balo, C. C., Lagdameo, Y. J., & Tupa, N. S. (2018). A historical review of the development of organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) and its implications for the twenty-first century. Personnel Review, 47(4), 821–862. doi:10.1108/PR-04-2017-0136

- Organ, D. (2005). Organizational citizenship behavior: recent trends and developments. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4(1), 295–306. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104536

- Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: the good soldier syndrome. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

- Organ, D. W. (1990). The motivational bases of organizational citizenship behavior. In L. L. Cummings & B. M. Staw (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior (Vol. 12, pp. 43–72). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Owen, F. A., Pappalardo, S. J., & Sales, C. A. (2000). Organizational citizenship behaviour: Proposal for a new dimension in counsellor education. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 34(2), 98–110.

- Podsakoff, N. P., Whiting, S. W., Podsakoff, P. M., & Blume, B. D. (2009). Individual-and organizational-level consequences of organizational citizenship behaviors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(1), 122. doi:10.1037/a0013079

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Paine, J. B., & Bachrach, D. G. (2000). Organizational citizenship behaviors: A critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research. Journal of Management, 26(3), 513–563. doi:10.1177/014920630002600307

- Reja, U., Manfreda, K., Hlebec, V., & Vehovar, V. (2003). Open-ended vs. close-ended questions in web questionnaires. Developments in Applied Statistics, 19(1), 159-177.

- Shah, S., & Tyagi, A. (2017). HR challenges and opportunities in banking sector. International Journal of Engineering Technology Science and Research, 4(7), 928–933.

- Shanker, M. (2016). Organizational citizenship behavior and organizational commitment in Indian Workforce. Journal of Psychosocial Research, 11(2), 397.

- Smith, C. A., Organ, D. W., & Near, J. P. (1983). Organizational citizenship behavior: Its nature and antecedents. Journal of Applied Psychology, 68(4), 653–663. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.68.4.653

- Sridhar, A., & Thiruvenkadam, T. (2014). Impact of employee engagement on organization citizenship behaviour. BVIMSRs Journal of Management Research, 6(2), 147–155.

- Stevens, J. (2002). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Uhl-Bien, M., & Marion, R. (2009). Complexity leadership in bureaucratic forms of organizing: A meso model. The Leadership Quarterly, 20, 631–650. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.04.007

- Vaijayanthi, P., Shreenivasan, K. A., & Roy, R. (2014). Deducting the organizational citizenship behavior dimensions and its antecedent (job satisfaction) in the Indian context. Research Journal of Applied Sciences, Engineering and Technology, 7(10), 1953–1960. doi:10.19026/rjaset.7.487

- Veličkovska, I. (2017). Organizational citizenship behavior- definition, determinants and effects. Engineering Management, 3(1), 40–51.

- Zeinabadi, H., & Salehi, K. (2011). Role of procedural justice, trust, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment in organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) of teachers: Proposing a modified social exchange model. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 29(1), 1472–1481. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.387

- Zheng, W., Zhang, M., & Li, H. (2012). Performance appraisal process and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 27(7), 732–752. doi:10.1108/02683941211259548

Appendix 1.

The Proposed Instrument

Organisational Citizenship Behavior/संघठनात्मक नागरिक व्यवहार

(Tick one box for each question/प्रत्येक प्रश्न के लिए किसी एक खाने पर सही का निशान लगायें)