Abstract

Bureaucratic organizational structure (OS) is perceived as an impediment to employees’ positive behavior including their knowledge-sharing behavior. This study investigates the role of formal, centralized and hierarchal OS in shaping the knowledge sharing behavior of public employees. It investigates the mediation role of social dilemma, i.e., a clash between self and collective interests. Cross-sectional data are collected from 309 executive employees of five federal ministries in Pakistan. The results confirm that formal and centralized OS receive significant positive association, whereas hierarchal OS receives a significant negative association with employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior. Partial negative mediation role of the social dilemma is also evident from the results. It implies that employees prefer to pursue self-interest when they find a clash between self and collective interests. Therefore, the study suggests concrete measures in human resource policies and practices that may improve the ethical environment of public sector institutions.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Knowledge sharing is an activity that transforms individuals’ knowledge into organizational learning. However, in bureaucratic organizations, it is difficult to ensure that employees share knowledge with colleagues. There are several organizational and behavioral factors that impede the free flow of knowledge among employees in an organization. Identification of these factors may assist policymakers to devise favorable policies that support employees in shaping their knowledge-sharing behavior. This study, therefore, has assessed the structural and behavioral impediments of knowledge sharing in the bureaucratic organizational structure. Bureaucratic organizational structure is perceived as a burden on employees and has a negative impact on their behavior. Long hierarchal organizational structure, power game and perceived cost of knowledge sharing in terms of loss of ones’ unique value are identified as the barriers for shaping employees' knowledge-sharing behavior.

1. Introduction

Like other managerial reforms in the public sector, knowledge-based reforms are also receiving importance in recent times (Choi, Citation2016; Zhang & Dawes, Citation2006). These reforms focus on knowledge creation, its accumulation, and diffusion (Choi, Citation2016). Knowledge management initiatives are mainly contingent on how organizational employees share knowledge with colleagues (Choi, Citation2016; Ipe, Citation2003). This acts as a critical element for overall organizational improvement by improving the productivity and efficiency in both the sectors, public and private (Amayah, Citation2013; Chong, Salleh, Ahmad, & Sharifuddin, Citation2011; Kim & Lee, Citation2006; Willem & Buelens, Citation2007; Wong, Tan, Lee, & Wong, Citation2013). However, unlike the private sector where productivity and efficiency are synonymous with profitability, the public sector, being essentially non-profit in nature, has not focused on knowledge-sharing initiatives (Amayah, Citation2013; Gorry, Citation2008; Vong, Zo, & Ciganek, Citation2016; Yusof, Ismail, Ahmad, & Yusof, Citation2012). Because of its importance and necessity, it has become a challenge in the public sector organizations to ensure that their employees are actively involved in sharing knowledge with colleagues (Kim & Lee, Citation2006; Sandhu, Jain, & Ahmad, Citation2011).

It is central to note that if employees do not share knowledge, its value as an organizational asset may depreciate (Choi, Citation2016). Employees hide or withhold knowledge intentionally, called “knowledge hiding” or unintentionally called “knowledge hoarding”. Intentional or unintentional, it has negative consequences on individual performance as well as organizational performance (Tangaraja, Mohd Rasdi, Ismail, & Abu Samah, Citation2015). Therefore, fostering a knowledge-sharing culture in organizations, whether public or private, becomes a challenge (Choi, Citation2016; Henttonen, Kianto, & Ritala, Citation2016). The issue assumes greater significance because tacit knowledge acquired by employees is inherently difficult to transfer and completely depends on their willingness to share (Amayah, Citation2013). Facilitating intra-organizational knowledge sharing in the public sector requires an in-depth understanding of the underlying causes of knowledge hoarding, knowledge hiding and knowledge sharing (Amayah, Citation2013; Zhu, Citation2016). Although some research is available on knowledge sharing in the public sector, it primarily focuses on organizational issues such as social capital (Choi, Citation2016), organizational context (Amayah, Citation2013; Trong Tuan, Citation2017; Willem & Buelens, Citation2007), cultural aspects (Amayah, Citation2013; Boateng & Agyemang, Citation2014; Choi, Citation2016; Trong Tuan, Citation2017), individual characteristics (Choi, Citation2016; Henttonen et al., Citation2016; Tangaraja et al., Citation2015), motivational factors (Amayah, Citation2013; Tangaraja et al., Citation2015), and management effectiveness (Moon & Lee, Citation2014). However, there is a lack of research focus to (1) confirm the existence of Bureaucratic Red Tape and its influence on employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior (Asrar-ul-Haq & Anwar, Citation2016; Vong et al., Citation2016; Willem & Buelens, Citation2007) and to (2) examine employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior from the perspective of social dilemma (Cabrera & Cabrera, Citation2002; Lam & Lambermont-Ford, Citation2010; Razmerita, Kirchner, & Nielsen, Citation2016). To fill these gaps, this study has made an effort to investigate the direct link of the factors of bureaucratic organizational structure (OS), i.e., formal, centralized and hierarchal, and employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior. It has also investigated the mediation role of social dilemma aspects, i.e., power game and perceived cost of knowledge sharing (PCKS), for the relationship between factors of OS and employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior. This study, therefore, has answered two research questions. Firstly, what are the bureaucratic organizational factors that can impede the sharing of knowledge among organizational members? Secondly, does social dilemma negatively mediate the relationship between factors of bureaucratic OS and employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior. This study, therefore, extends our knowledge through understanding the role of bureaucratic OS and social dilemma in shaping employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior. The results of this study would facilitate better policy formulation for intra-organizational and inter-organizational collaborations among employees in public sector organizations in Pakistan.

2. Theoretical development and hypotheses

This section explains the knowledge-sharing phenomena in the public sector organizations. It also provides arguments and illustrations for the hypothesized relationships.

2.1. Knowledge sharing in the public sector

Knowledge sharing is described as collaboration and to provide knowledge and work-related guidance that helps others in developing innovative ideas, solving problems, and policies and procedures implementation (Wang & Noe, Citation2010). According to Silvi and Cuganesan (Citation2006), there is a positive association between employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior and overall performance of the organization. Though the public sector organizations have been successful in retaining employees on a long-term basis, it should also strive to retain their knowledge (Trong Tuan, Citation2017). This could be possible by framing appropriate organizational policies that support knowledge sharing. Among the two basic types of knowledge, “tacit and explicit” (Nonaka & Takeuchi, Citation1995), tacit knowledge sharing is the focus of this research study.

2.2. Bureaucratic Red Tape and employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior

Bureaucratic Red Tape is explained as the compliance burden on employees due to formal rules, processes, procedures, regulations, and guidelines in public sector organizations (Kim & Lee, Citation2006). Red Tape, being an essential part of bureaucratic organization, has a negative effect on individuals’ behavior. It is considered as a barrier in intra-organizational information flow and communication (Pandey & Bretschneider, Citation1997, p. 117). Presence of Bureaucratic Red Tape may suppress the self-expression and responsible behavior of employees (Oliveira, Curado, Maçada, & Nodari, Citation2015). The general perception of red tape correlates with the formal OS. However, there are other bureaucratic organizational factors that entail a compliance burden on employees. Kaufmann, Borry, and DeHart‐Davis (Citation2019, p. 1) pointed out “ … [that] Bureaucratic Red Tape is based on multiple dimensions of overall organizational structure, not just formalization”. They state that formal, centralized and hierarchal OS are three bureaucratic characteristics that entail compliance burden on employees and come under the umbrella of Red Tape.

Centralized OS has been proved as a negative predictor of innovation, public service motivation and organizational effectiveness (Damanpour, Citation1991; Torfing, Citation2019; Zheng, Yang, & McLean, Citation2010). In terms of communication, centralized structures inhibit interaction among employees (Gold & Arvind Malhotra, Citation2001). On the other hand, decentralized authority facilitates internal communication (Zheng et al., Citation2010). Employees, in organizations where centralized authority is in practice, have limited autonomy to act. It reduces their interest to be innovative. When employees are not motivated for innovation, they also lose motivation for knowledge sharing and collaboration with colleagues (Kim & Lee, Citation2006). In contrast, deregulation and decentralization increase satisfaction levels among employees because they enjoy autonomy at the workplace (Yousaf, Zafar, & Abi Ellahi, Citation2014). This satisfaction motivates them to collaborate with colleagues. Furthermore, the success of public sector reform initiatives is also possible with decentralized OS (Sandhu et al., Citation2011). Knowledge sharing is part of knowledge-based reform initiatives in the public sector institutions. Knowledge-based reforms are the subset of public sector reforms. Therefore, at a broader level, centralized OS inhibits knowledge sharing and thus restricts the success of public sector reform efforts. Amayah (Citation2013) and Kim and Lee (Citation2006) posit that centralized OS in public sector organizations is a barrier for employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior. However, both of the studies have not received empirical evidence of the relationship between centralized OS and knowledge-sharing activities and knowledge-sharing capabilities of employees in public sector organizations in USA and South Korea, respectively. Sharratt and Usoro (Citation2003) have explained the difference between centralized and decentralized OS for shaping employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior. According to them, “organizations with centralized, bureaucratic management style can stifle the creation of new knowledge, whereas a flexible decentralized OS encourages knowledge sharing, particularly of knowledge that is more tacit in nature” (p. 189). It is, therefore, argued that the centralized OS does not facilitate social networking and knowledge sharing among colleagues in public sector organizations. This leads to the first hypothesis:

H1: Centralized OS negatively affects knowledge-sharing behavior of public sector employees.

Formal OS seems less effective due to rigid rules, policies, regulations, and procedures compared with informal ones in facilitating knowledge sharing in organizations (Willem & Buelens, Citation2007). Informal OS offers greater flexibility and openness to organizational members for coordinating, communicating and interacting with each other (Jarvenpaa & Staples, Citation2001; Tsai, Citation2002; Willem & Buelens, Citation2007). Individuals who deal with meaningless and burdensome rules are bound to “incur an inefficiency to [the] organization” (Lam, Citation2004, p. 33). This inefficiency is reflected in their behaviors including their knowledge-sharing behaviors. Perception of Bureaucratic Red Tape or the burdensome rules and procedures gives the feeling of alienation among employees (DeHart-Davis & Pandey, Citation2005). This feeling of alienation restricts them to involve in social activities such as networking with colleagues and knowledge sharing. Previous studies (Amayah, Citation2013; Kim & Lee, Citation2006; Willem & Buelens, Citation2007; Wong et al., Citation2013) have made the strong argument that formal and informal OS have negative and positive associations with public sector employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior, respectively. Willem and Buelens (Citation2007) have received empirical evidence of the negative relationship between formal OS and employees' knowledge-sharing behavior. Empirical evidence in other studies is lacking. Hatala and Lutta (Citation2009) have argued that organizations rely heavily on rules because they have pressure to process existing available information. The restrictions to rely on rules unintentionally put the employees under stress and they avoid indulging themselves in value-added activities like sharing their know-how with colleagues. Red Tape perception also restricts individuals’ creativity and innovation (DeHart-Davis, Citation2008). Knowledge sharing is an act of creativity and innovation. When employees are under stress, they are no more innovative and creative and they lack their interest to share knowledge with colleagues. Therefore, it is argued that the formal nature of the public sector hinders knowledge-sharing behavior.

H2: Formal OS negatively affects knowledge-sharing behavior of public sector employees.

It is a general perception that hierarchal layers in bureaucratic organizations are needed to have more managerial control which at times lead to over control and result in employee frustration (Bozeman & Feeney, Citation2011; Kaufmann, Taggart, & Bozeman, Citation2019). This frustration has a negative impact on employees’ behavior including their knowledge-sharing behavior. Employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior is promoted by collaboration among them. Hierarchical structures in bureaucracies restrict collaboration among employees and thus restrict their knowledge-sharing behavior (Torfing, Citation2019). Organizational processes become significantly slow when decisions and information have to flow up and down the hierarchy (Vuuren, Citation2011). Long hierarchy demotivates employees and promotes them for knowledge hoarding (Hatala & Lutta, Citation2009). Lam (Citation2004) posits that long hierarchal structure in bureaucracies restricts open communication among employees and hinders their adaptability to social evolution. Friesl, Sackmann, and Kremser (Citation2011) have conducted a qualitative study on German Armed forces and conclude that rank-based hierarchy influences knowledge sharing negatively. According to Taylor and Wright (Citation2004), hierarchal and top-down nature of the public sector creates problems for designing a supportive knowledge-sharing environment. In a long hierarchal structure, effective communication is difficult and it restricts knowledge-sharing behavior of employees. Hence, it is argued that

H3: Hierarchal OS negatively affects knowledge-sharing behavior of public sector employees.

2.3. Mediating role of social dilemma on employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior

Social dilemma refers to a situation where short-term self-interests of an individual employee in terms of time, money and efforts are at variance with public, collective, or organizational interests (Van Lange, Joireman, Parks, & Van Dijk, Citation2013). Employees, especially in the public sector organizations, combine knowledge with promotional opportunities. They perceive that they will have more power if they are more knowledgeable. Therefore, promoting a knowledge-sharing culture in public sector organizations becomes difficult (Liebowitz & Yan, Citation2004). Among several aspects of social dilemma, this study has considered two dimensions, i.e., power game among employees and PCKS in terms of loss of ones’ unique value in the organization. Employees in the public sector are less inclined to switch jobs and are more likely to preserve and promote their status in the organization. This aspect compounds the effect multilayered bureaucracy or Bureaucratic Red Tape in the public sector plays in generating power game among employees. Hence, the magnitude of employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior is proportionate with the presence of power game and micro-politics in an organization and vice versa (Willem & Buelens, Citation2007). Therefore, it is vital to investigate the self-interested behavior of bureaucrats in shaping employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior (Kim, Lee, Paek, & Lee, Citation2013; Lam, Citation2004).

Concerning centralized OS, here are multiple empirical pieces of evidence on the notion that centralized decision-making system alienates employees (Aiken & Hage, Citation1966; DeHart-Davis & Pandey, Citation2005; Miller, Citation1967; Zeffane, Citation1993). The reason may lie in the fact that individuals want autonomy and discretion to perform in their organizations. When they do not experience autonomy, it likely alienates them from work and colleagues. This state of alienation promotes social dilemma among them and they lack focus from collective or organizational interests. However, when employees feel alienation from work, they may not alienate themselves from pursuing self-interests. Therefore, they start involving themselves in organizational politics and cost–benefit analysis of their behavior. When knowledge is shared, its “costs are likely to concentrate on the individual, but the benefits may extend to all the employees in an organization” (Kim, Citation2018, p. 113). When individuals are in social dilemma situation, they are interested to achieve power in their organization or to maintain a prominent position among their colleagues. Moreover, centralized OS suppresses employees’ “natural desire for self-expression, responsibility, growth, and achievement” (Baldwin, Citation1990). These outcomes are negative and promoting “powerlessness” and “meaninglessness” feelings among employees (DeHart-Davis & Pandey, Citation2005). These feelings demotivate employees to contribute their efforts for collective benefits. However, empirical evidence of the direct relationship between centralized OS with employees’ knowledge-sharing capabilities and knowledge-sharing activities is lacking (see Kim & Lee, Citation2006; Vong et al., Citation2016). This implies the need to investigate the mediated role of social dilemma for knowledge sharing. Therefore, it is argued that the centralized OS enforces employees to put more focus on their self-interests rather than collective interests. These social dilemma aspects prevent them to share their know-how willingly and openly with colleagues, which may reduce their chance of getting promotions or to keep themselves prominent in the eyes of the higher-ups. Hence, it posits that:

H4a & 4b: The relationship between centralized OS and employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior is mediated by the power game and PCKS.

Literature has supported a priori that formal OS or Bureaucratic Red Tape restricts employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior (Willem & Buelens, Citation2007; Yao, Kam, & Chan, Citation2007). However, there is a lack of empirical evidence about the direct negative association between formal OS and employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior in public institutions (see Amayah, Citation2013; Kim & Lee, Citation2006). It is argued that social dilemma has a negative effect on public sector employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior. The self-interested behavior of employees can malign a favorable organizational environment, and employees are no more interested to collaborate with colleagues (Clark & Ivankova, Citation2015; Foss & Mahoney, Citation2010). Furthermore, Bureaucratic Red Tape is empirically proved its negative effect on employees' public service motivation by negatively influences their perceptions about serving the public (Moynihan & Pandey, Citation2007b). They, therefore, get focused on self-interest rather to think about their role for collective interest. Hence, it is argued that the formal OS promotes self-interested behavior in public sector employees which in turn restricts them for effective knowledge sharing or motivates them to hoard what they know. It leads to the following hypotheses:

H5a & 5b:The relationship between formal OS and employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior is mediated by the power game and PCKS.

There is a strong relationship between hierarchal OS with information flow and communication among employees (Moynihan & Pandey, Citation2007b). However, moving upward in the ladder is a natural instinct in employees but when there is a long hierarchy and employees find it difficult to get promotions, their motivation for public or organizational interest becomes low. They may involve in organizational politics to get promotions by using different tactics such as getting prominent by maintaining their unique value. Small hierarchy, in contrast, promotes among employees the sense of cooperation which in turn motivates them for their collective or organizational contribution. This sense of cooperation facilitates knowledge sharing (Lam, Citation2004). But when the ladder of the hierarchy is long, it does not promote the sense of public good and cooperation among employees and thus their self-interest may get prominent. Friesl et al. (Citation2011), through qualitative analysis, observed micro-political behaviors of an employee when there are long hierarchies in organizations, which eventually restricts employees' knowledge-sharing behavior. Thus, in the light of social dilemma, hierarchal OS has an indirect relationship with employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior. Hence,

H6a & 6b: The relationship between long organizational hierarchal structure and knowledge sharing behavior is mediated by the power game and perceived cost of knowledge sharing.

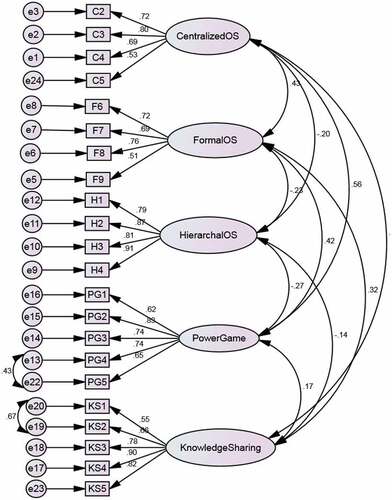

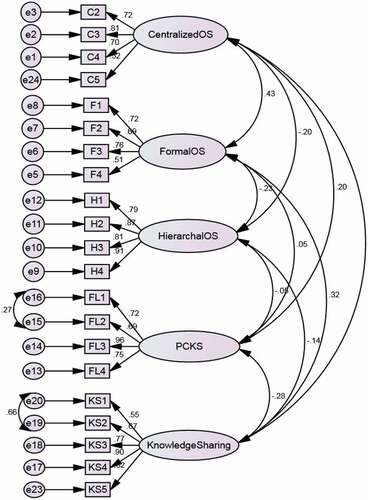

Figure illustrates the earlier discussion to demonstrate the direct and indirect relationship between factors of bureaucratic OS and employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior.

3. Materials and methods

Adopting the census approach, data for this study have been collected from all executive employees from five federal ministries in Pakistan. The ministries selected for this study are Ministry of Planning, Development and Reforms, Ministry of Information Technology and Telecom, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of National Health Services, Regulation and Coordination, and Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training. These ministries have been selected because health, education, finance, information technology, telecommunication, and planning and development are important public policy formulation and decision-making organizations, and hence, knowledge-sharing practices in these organizations are important to indicate the quality of public policy and decision-making. As part of a broader study, the data for this study have been collected from January to June in 2017. The response rate is 64.24% that is justified in the literature (Mellahi & Harris, Citation2016). A questionnaire has been developed to obtain data from respondents. The questionnaire has three parts: first is the information sheet that explains the focus and scope of this study, ensures confidentiality and provides researchers’ contact information; the second part asks about demographic information about the respondents, while the third part includes statements related to the constructs. The questionnaire has been self-administered to get responses from respondents. They have been given instructions to respond to the statements on a given 5-point Likert scale of agreement. The instrument was pilot-tested in one organization before it is launched for final data collection. After data cleaning, it is initially analyzed for common method bias. A structured equation modeling approach has been used to study the hypothesized relationships by measurement model and structural model analyses (Fuller, Simmering, Atinc, Atinc, & Babin, Citation2016).

3.1. Research instruments

The scale to measure study constructs is adopted from previous researches. The measure assessing respondents’ perception about the centralized OS is adopted from Kim and Lee (Citation2006) based on five items. The sample statement is “Even small matters have to be referred to someone higher up for a final answer”. Five-item scale assessing respondents’ perceptions about the formal OS is adopted from Moynihan, Wright, and Pandey (Citation2012). The scale assesses respondents’ agreement with statements such as “Personnel rules make it hard to remove poor performers from the organization”. Respondents' perception about hierarchal OS is assessed using four items adopted from Lee and Yang (Citation2011). The scale measures respondents’ agreement with statements such as “There are relatively few layers in my organizational hierarchy” (R). Two aspects of social dilemma are included in this study. First is the power game among employees and second is the PCKS in terms of loss of ones’ unique value. The scale with five items to measure employees' perception of power game is adopted from Willem and Buelens (Citation2007). The sample statement is “In our organization, favoritism is an important way to achieve something”. The scale to measure PCKS is adopted from Renzl (Citation2008). The scale has four items and the sample statement is “If I provide everybody with my entire know-how I am afraid of being replaceable”. The scale to measure employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior is adopted from van Den Hooff and De Ridder (Citation2004). Casimir, Lee, and Loon (Citation2012) have validated the scale with five items. The sample statement is “I voluntarily share my skills with colleagues within my department”.

3.2. Common method bias

Multiple statistical remedies have been used in this study to check for the existence of common method bias (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, & Podsakoff, Citation2012). The variance explains by a single factor is 15.90% which is less than 50%. It concludes that the dataset does not suffer by common method bias (Fuller et al., Citation2016). Moreover, study constructs have no multicollinearity issue, i.e., r is less than 0.9 (Kanwal, Chong, & Pitafi, Citation2019; Pavlou & El Sawy, Citation2006). Confirmatory factor analysis has also been conducted to validate the model and to check for common method bias. All the model fit indices are in acceptable range (see Table ). The measurement models are illustrated in Figures and . Based on these statistical remedies, it is concluded that common method bias does not influence the results of this study.

Table 1. Fit indices of study model

4. Results

Convergent validity or the construct validity refers to that all items supposed to measure a single construct (Pavlou & El Sawy, Citation2006). Convergent validity has been tested by assessing factor loadings of the items that should exceed 0.5 (Straub, Citation1989), composite reliabilities should exceed 0.6 (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation1988), and the average variance extracted (AVE) should exceed 0.5 (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Items’ factor loadings are significant and ranged between 0.526 and 0.918. The first item of centralized OS has been loaded less than 0.5 and thus it is excluded. The variable initially has five items and after removing the first item it is left with four items. The items of all other variables have loadings in an acceptable range. Item loadings and descriptive statistics are reported in Table . Cronbach’s alpha value and composite reliabilities of the construct are also in acceptable ranges that exceed 0.7. The AVE values are above 0.5 and the square root of the AVE values are greater than correlation scores of the constructs (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981) (see Table ). Thus, the results have confirmed the reliability and validity of the model.

Table 2. Item loadings and descriptive statistics

Table 3. Construct validity and inter-correlation

A total of 309 responses have been collected. Of these, the average of males and females is 73.8 and 26.2, respectively. The number of male subjects is considerably greater, as more men were appointed in the public sector in Pakistan. This situation is improving because the government of Pakistan is now focusing on gender equality in the public sector appointments. Respondents reported an average age of 41 years and an average tenure of 14 years in the public sector.

Model estimation results are presented in Table . The direct relationship of three factors of OS, i.e., centralized, formal, and hierarchal, and employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior, is examined. The relationships of the centralized and formal OS with employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior are positively significant. Thus, hypotheses 1 and 2 are rejected. However, a negative relationship is evident in support of hypothesis 3 that confirms the reverse relationship between hierarchal OS and employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior.

Table 4. Model estimation results

For the indirect effect of social dilemma, partial support is evident in results. Social dilemma, in terms of power game and PCKS, mediates the relationship between centralized OS and employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior. Thus, hypotheses 4a and 4b are supported. Social dilemma, in terms of power game, has been proved as a mediator for the association between centralized OS and employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior.

However, PCKS does not mediate this relationship. Thus, hypothesis 5a is accepted, whereas hypothesis 5b is rejected. Social dilemma, in terms of power game, mediates the relationship between formal OS and knowledge-sharing behavior of employees. However, PCKS does not mediate this relationship. Thus, hypothesis 6a is accepted, whereas hypothesis 6b is rejected.

5. Discussion

Inconsistent with the review of the literature and generally perceived expectation, this study has found a positive association between centralized and formal OS with employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior. In contrast, Willem and Buelens (Citation2007) have received a significant negative association of formal OS with employees’ knowledge-sharing intensity. Whereas, Amayah (Citation2013), Vong et al. (Citation2016) and Kim and Lee (Citation2006) have supported the notion that factors of the bureaucratic OS have a negative influence on employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior. However, in all three studies, the authors have not empirically proven a significant negative or positive association between the two in public sector organizations in USA, Cambodia and South Korea, respectively. Therefore, further empirical investigations of the phenomena are needed. Furthermore, it is argued in the literature that not all formal rules and regulations are bad or create frustration. Some rules are good and effective and influence employees positively (Moynihan & Pandey, Citation2007a). These are termed as green tape (DeHart-Davis, Citation2008). Therefore, it implies that, in Pakistan, the formal structure of public institutions practices good rules, policies, procedures, and regulations that promote the perception of green tape rather than to foster red tape. Moreover, Moynihan and Pandey (Citation2007b, p. 47) while citing Wolf (Citation1997) argues that criticism on formal OS in terms it is associated with compliance burden is “a mistaken belief”. They posit that “most modern agencies are formalized to a degree appropriate with their mission”. It implies that formal and centralized OS in public sector organizations in Pakistan are appropriate with their mission and do not entail compliance burden on employees. Furthermore, Pakistan is a high context culture where “[i]nformation is sought and spread through discussion with friends, coworkers, relatives and rumors” (Malik & Malik, Citation2008, p. 46). Therefore, strong informal networking, also present in public sector organizations, may provide a strong argument why red tape, in terms of the formal and centralized OS, does not negatively influence the knowledge-sharing behaviors of public sector employees. Willem and Buelens (Citation2007) have acknowledged a priori that red tape exists in the public sector organizations but it is not always true. Moreover, Asian culture promotes the sharing of knowledge with natural relations rather than to rely on the documents or the databases (Lin & Dalkir, Citation2010; Yao et al., Citation2007). Yiu and Lin (Citation2002) demonstrate that knowledge sharing mainly depends on the natural relationships rather than the information retrieved from other sources. Furthermore, in Asian culture, informal knowledge sharing is considered as part of organizational life.

However, the study has found a negative association between hierarchal OS and employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior. The result is in line with the a priori established in the theoretical framework of this study that is based on the previous researches (see Friesl et al., Citation2011; Hatala & Lutta, Citation2009; Lam, Citation2004; Seba, Rowley, & Delbridge, Citation2012; Taylor & Wright, Citation2004; Vuuren, Citation2011; Willem & Buelens, Citation2007). Employees feel demotivated to informally share their experiences and know-how when the hierarchal structure in their organization is not favorable (Hatala & Lutta, Citation2009). The study confirms that long hierarchal structure in bureaucracies entails compliance burden on employees and it restricts open communication among them (Kaufmann et al., Citation2019; Lam, Citation2004).

The indirect effect of power game and PCKS is evident in centralized OS and employees’ knowledge-sharing relationship. When the structure is centralized, it is important to be in the good book of the higher-ups and to gain power. Furthermore, the positive association between centralized OS and employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior provides strong evidence that centralized OS in Pakistani culture does not serve as a negative bureaucratic factor. It, rather, facilitates employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior. However, the positive association of centralized OS with employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior becomes negative by adding PCKS and power game as a mediator. The partial negative indirect mediating effect of the PCKS in terms of fear of loss of ones’ unique value provides evidence of the fact that the centralized OS is not basically the culprit. It is social dilemma, the self-interested behavior of public sector employees that makes this relationship negative. The employees’ perception of centralized OS facilitates them for sharing their know-how with others. However, when they evaluate the sharing cost vis-à-vis the loss of their unique value, they tend to hide or withhold knowledge. Renzl (Citation2008) and Amayah (Citation2013) also demonstrate that when employees have a fear of loss of ones’ unique value in their organizations, they avoid sharing their knowledge with colleagues.

The indirect effect of social dilemma in terms of power game is evident in formal OS and employees’ knowledge-sharing relationships. It indicates that formal OS in the public sector organizations in Pakistan promotes power game among employees, which in turn demotivates them for their knowledge-sharing behavior. The result receives partial support in the previous empirical research (see Willem & Buelens, Citation2007). However, the indirect effect of PCKS is not evident in formal OS and employees’ knowledge-sharing relationships. When everything is documented and practiced according to the rules, policies, and procedures, the employees may not feel any fear of losing their value or position. The results are in line with the cultural values of Pakistan that people feel comfortable with the written rules and policies. It is evident in the earlier results of this study that Bureaucratic Red Tape, in terms of formal OS, does not negatively influence employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior in public sector organizations in Pakistan.

The social dilemma also indirectly affects the association between hierarchal OS and employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior. In organizations with long hierarchal structure, the existence of power game is not a surprise and this can negatively affect the behavior of employees at workplace including their knowledge-sharing behavior. Individuals, in public sector organizations in Pakistan, have to put a lot of effort to move one step up in the hierarchy. It leads them to involve in the power game which in turn forces them to hide their knowledge from colleagues. Furthermore, the need for power and position motivates employees to withhold knowledge and they share it when they see it could benefit them to maintain their value in the eyes of higher-ups and facilitate them to gain power. In such a situation, employees hide their knowledge with colleagues but they share it with their bosses (Amber, Khan, & Ahmad, Citation2018). Moynihan and Pandey (Citation2007b) posit that hierarchal structure in public organizations negatively affects employees’ public service motivation. When employees are demotivated to serve the public, their knowledge-sharing behavior becomes negative. In contrast, the mediation effect of the PCKS in terms of loss of ones’ unique value is not evident. It explains that hierarchal OS does not promote public sector employees to indulge themselves in cost-benefit analysis of knowledge sharing.

6. Theoretical and practical implications

Previous studies have discussed the negative role of bureaucratic OS for employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior. However, empirical evidence is lacking in literature. This study provides empirical evidence for the a priori. It implies that bureaucratic characteristics entail compliance burden on employees but it affects employees’ behaviors differently. Formal and centralized OS do entail compliance burden on employees but this burden facilitates them to have more knowledge sharing with colleagues. However, hierarchal OS restricts employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior. Furthermore, this study has accepted the long-awaited call for empirical assessment of social dilemma role on employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior. This study has proved that when an employee faces a clash between self-interest and collective interest, the pursuance of self-interest is preferred and it has a negative impact on employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior.

This study also provides suggestions to public sector managers and policymakers. To promote effective knowledge-sharing environment in public sector organizations in Pakistan, it is essential to introduce human resource practices that reduce social dilemma and stimulate public interest among employees (Wang & Noe, Citation2010). Along with the supportive OS, social environment that inculcates strong ethical values is essential for mitigating the negative influence of social dilemma. An environment that fosters open and knowledge friendly culture, an increase in commitment level, trust in management, rewarding individual participation, and communicating benefits of knowledge sharing, may convert employees’ focus from self-interest to public interest. These policy initiatives not only encourage but enforce knowledge sharing among public sector employees (Wang & Noe, Citation2010). Second, this research suggests that ethical leadership is critical for establishing knowledge-sharing behaviors among public sector employees. Ethical leadership is linked with transparency about knowledge sharing (Kalshoven, Den Hartog, & De Hoogh, Citation2011). Therefore, public sector organizations are required with leadership that encourages knowledge sharing among employees by shaping the supportive organizational environment. A serious lack of guidance and advice due to a lack of trust between a boss and his subordinate is also evident in a federal level public sector organization in Pakistan (Amber et al., Citation2018). Therefore, ethical leaders, who become the role model for subordinates by sharing their experiences, competence, and knowledge, may fill the gap created by social dilemma. Additionally, leaders must be empowered because only empowered leaders can foster knowledge sharing among employees (Wang & Noe, Citation2010).

7. Conclusion

Knowledge sharing is a force for organizational learning by improving the performance of individuals and organizations. This study confirms the positive association of formal and centralized OS and negative association of hierarchal OS with knowledge-sharing behavior of public employees in Pakistan. It also provides insight into social dilemma for these associations. Power game negatively mediates the association of centralized, formal and hierarchal OS with knowledge-sharing behavior of employees. However, PCKS mediates the association between centralized OS and knowledge-sharing behavior of employees. The empirical results of 309 survey participants indicate that improvement in the social environment through human resource policies and practices is inevitable to transcend the self-interests of employees. It necessitates inculcating strong ethical values that shift the focus of employees from self-interest to collective interest.

8. Limitations and future directions

There are limitations to this study. These limitations must be considered when interpreting results. The public sector has different organizational forms and levels (Amayah, Citation2013; Wettenhall, Citation2003; Willem & Buelens, Citation2007). This research study has included pure public organizations and executive-level employees for the collection of data. The findings, therefore, may not be generalized to the employees of autonomous public sector organizations and street-level bureaucracy. Moreover, employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior may vary in the sub-cultures of a country as well as in different national cultures (Michailova & Hutchings, Citation2006). Future research should consider changes in cultural patterns and norms of different countries. Furthermore, the findings of this study suggest additional research to confirm the role bureaucratic OS and social dilemma has for shaping employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior in public sector organizations. This study has assessed two social dilemma aspects, i.e., power game and PCKS, in terms of loss of ones’ unique value. Other aspects of social dilemma, such as PCKS in terms of time, money and efforts, also need scholars’ attention. Furthermore, this study has collected cross-sectional data from individual employees working in public organizations. Knowledge-sharing behavior of employees working in projects or teams and inter-organizational knowledge-sharing mechanism with the lens of social dilemma is needed to investigate in future (see Qian et al., Citation2019; Zhang, Lin, Chung, Tsai, & Wu, Citation2019).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Quratulain Amber

Quratulain Amber is a Doctoral student at COMSATS University, Islamabad. Her research interests are public policy, knowledge sharing, public service motivation, public management reforms. She has seven years teaching and administrative. She has published her research work in international journals.

Mansoor Ahmad

Dr. Mansoor Ahmed is the Assistant Professor at COMSATS University, Islamabad. His research interests are high performance HRM, convergence/divergence debate and institutional theory. He has more than 12 years teaching and administrative experience. He has published his research in prominent international journals.

Iram A. Khan

Dr. Iram A. Khan is the Senior Joint Secretary at Auditor General Pakistan. His research interests are knowledge groups, public policy and knowledge management. He has a vast experience of teaching in several universities in Pakistan. He has published his research in prominent international journals.

Fakhar Abbas Hashmi

Mr. Fakhar Abbas Hashmi is the research scholar and Librarian at Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. He has published his work in international journals.

References

- Aiken, M., & Hage, J. (1966). Organizational alienation: A comparative analysis. American sociological review (pp. 497–18).

- Amayah, A. T. (2013). Determinants of knowledge sharing in a public sector organization. Journal of Knowledge Management, 17(3), 454–471. doi:10.1108/jkm-11-2012-0369

- Amber, Q., Khan, I. A., & Ahmad, M. (2018). Assessment of KM processes in a public sector organisation in Pakistan: Bridging the gap. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 16(1), 13–20. doi:10.1080/14778238.2017.1392409

- Asrar-ul-Haq, M., & Anwar, S. (2016). A systematic review of knowledge management and knowledge sharing: Trends, issues, and challenges. Cogent Business & Management, 3(1), 1127744. doi:10.1080/23311975.2015.1127744

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. doi:10.1007/BF02723327

- Baldwin, J. N. (1990). Perceptions of public versus private sector personnel and informal red tape: Their impact on motivation. The American Review of Public Administration, 20(1), 7–28. doi:10.1177/027507409002000102

- Boateng, H., & Agyemang, F. G. (2014). A qualitative insight into key determinants of knowledge sharing in a public sector institution in Ghana. Information Development. doi:10.1177/0266666914525650

- Bozeman, B., & Feeney, M. K. (2011). Rules and red tape: A prism for public administration theory and research. New York, NY: ME Sharpe.

- Cabrera, A., & Cabrera, E. F. (2002). Knowledge-sharing dilemmas. Organization Studies, 23(5), 687–710. doi:10.1177/0170840602235001

- Casimir, G., Lee, K., & Loon, M. (2012). Knowledge sharing: Influences of trust, commitment and cost. Journal of Knowledge Management, 16(5), 740–753. doi:10.1108/13673271211262781

- Choi, Y. (2016). The impact of social capital on employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior: An empirical analysis of US federal agencies. Public Performance & Management Review, 39(2), 381–405. doi:10.1080/15309576.2015.1108795

- Chong, S. C., Salleh, K., Ahmad, S. N. S., & Sharifuddin, S.-I. S. O. (2011). KM implementation in a public sector accounting organization: An empirical investigation. Journal of Knowledge Management, 15(3), 497–512. doi:10.1108/13673271111137457

- Clark, V., & Ivankova, N. V. (2015). Mixed methods research: A guide to the field (Vol. 3). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Damanpour, F. (1991). Organizational innovation: A meta-analysis of effects of determinants and moderators. Academy of Management Journal, 34(3), 555–590.

- DeHart-Davis, L. (2008). Green tape: A theory of effective organizational rules. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 19(2), 361–384. doi:10.1093/jopart/mun004

- DeHart-Davis, L., & Pandey, S. K. (2005). Red tape and public employees: Does perceived rule dysfunction alienate managers? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 15(1), 133–148. doi:10.1093/jopart/mui007

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 39–50. doi:10.1177/002224378101800104

- Foss, N. J., & Mahoney, J. T. (2010). Exploring knowledge governance. International Journal of Strategic Change Management, 2(2–3), 93–101. doi:10.1504/IJSCM.2010.034409

- Friesl, M., Sackmann, S. A., & Kremser, S. (2011). Knowledge sharing in new organizational entities: The impact of hierarchy, organizational context, micro-politics and suspicion. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 18(1), 71–86. doi:10.1108/13527601111104304

- Fuller, C. M., Simmering, M. J., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y., & Babin, B. J. (2016). Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3192–3198. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.008

- Gold, A. H., & Arvind Malhotra, A. H. S. (2001). Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 185–214. doi:10.1080/07421222.2001.11045669

- Gorry, G. A. (2008). Sharing knowledge in the public sector: Two case studies. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 6(2), 105–111. doi:10.1057/palgrave.kmrp.8500172

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (Vol. 6). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Hatala, J. P., & Lutta, J. G. (2009). Managing information sharing within an organizational setting: A social network perspective. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 21(4), 5–33. doi:10.1002/piq.20036

- Henttonen, K., Kianto, A., & Ritala, P. (2016). Knowledge sharing and individual work performance: An empirical study of a public sector organisation. Journal of Knowledge Management, 20(4), 749–768. doi:10.1108/JKM-10-2015-0414

- Ho, R. (2006). Handbook of univariate and multivariate data analysis and interpretation with SPSS. New York, NY: Chapman and Hall/CRC.

- Ho, R. (2013). Handbook of univariate and multivariate data analysis with IBM SPSS. New York, NY: Chapman and Hall/CRC.

- Ipe, M. (2003). Knowledge sharing in organizations: A conceptual framework. Human Resource Development Review, 2(4), 337–359. doi:10.1177/1534484303257985

- Jarvenpaa, S. L., & Staples, D. S. (2001). Exploring perceptions of organizational ownership of information and expertise. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 151–184. doi:10.1080/07421222.2001.11045673

- Kalshoven, K., Den Hartog, D. N., & De Hoogh, A. H. (2011). Ethical leadership at work questionnaire (ELW): Development and validation of a multidimensional measure. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(1), 51–69. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.12.007

- Kanwal, S., Chong, R., & Pitafi, A. H. (2019). China–Pakistan economic corridor projects development in Pakistan: Local citizens benefits perspective. Journal of Public Affairs, 19(1), e1888. doi:10.1002/pa.v19.1

- Kaufmann, W, Borry, E. L, & DeHart‐Davis, L. (2019). More than pathological formalization: understanding organizational structure and red tape. Public Administration Review, 79(2), 236-245.

- Kaufmann, W, Taggart, G, & Bozeman, B. (2019). Administrative delay, red tape, and organizational performance. Public Performance & Management Review, 42(3), 529-553.

- Kim, S. (2018). Public service motivation, organizational social capital, and knowledge sharing in the Korean public sector. Public Performance & Management Review, 41(1), 130–151. doi:10.1080/15309576.2017.1358188

- Kim, S., & Lee, H. (2006). The impact of organizational context and information technology on employee knowledge‐sharing capabilities. Public Administration Review, 66(3), 370–385. doi:10.1111/puar.2006.66.issue-3

- Kim, T., Lee, G., Paek, S., & Lee, S. (2013). Social capital, knowledge sharing and organizational performance: What structural relationship do they have in hotels? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 25(5), 683–704. doi:10.1108/IJCHM-Jan-2012-0010

- Lam, A., & Lambermont-Ford, J.-P. (2010). Knowledge sharing in organisational contexts: A motivation-based perspective. Journal of Knowledge Management, 14(1), 51–66. doi:10.1108/13673271011015561

- Lam, B. C. (2004). Bureaucracy and red tape: A comparision between public and private construction project organizations in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong.

- Lee, C.-L., & Yang, H.-J. (2011). Organization structure, competition and performance measurement systems and their joint effects on performance. Management Accounting Research, 22(2), 84–104. doi:10.1016/j.mar.2010.10.003

- Liebowitz, J., & Yan, C. (2004). Knowledge sharing proficiencies: The key to knowledge management handbook on knowledge management 1 (pp. 409–424). Berlin: Springer.

- Lin, Y., & Dalkir, K. (2010). Factors affecting KM implementation in the Chinese community. International Journal of Knowledge Management (IJKM), 6(1), 1–22. doi:10.4018/IJKM

- Malik, K. P., & Malik, S. (2008). Value creation role of knowledge management: A developing country perspective. The Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 6(1), 41–48.

- Mellahi, K., & Harris, L. C. (2016). Response rates in business and management research: An overview of current practice and suggestions for future direction. British Journal of Management, 27(2), 426–437. doi:10.1111/1467-8551.12154

- Michailova, S., & Hutchings, K. (2006). National cultural influences on knowledge sharing: A comparison of China and Russia. Journal of Management Studies, 43(3), 383–405. doi:10.1111/joms.2006.43.issue-3

- Miller, G. A. (1967). Professionals in bureaucracy: Alienation among industrial scientists and engineers. American Sociological Review, 755–768. doi:10.2307/2092023

- Moon, H., & Lee, C. (2014). The mediating effect of knowledge‐sharing processes on organizational cultural factors and knowledge management effectiveness. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 26(4), 25–52. doi:10.1002/piq.v26.4

- Moynihan, D. P., & Pandey, S. K. (2007a). Finding workable levers over work motivation: Comparing job satisfaction, job involvement, and organizational commitment. Administration & Society, 39(7), 803–832. doi:10.1177/0095399707305546

- Moynihan, D. P., & Pandey, S. K. (2007b). The role of organizations in fostering public service motivation. Public Administration Review, 67(1), 40–53. doi:10.1111/puar.2007.67.issue-1

- Moynihan, D. P., Wright, B. E., & Pandey, S. K. (2012). Working within constraints: Can transformational leaders alter the experience of red tape? International Public Management Journal, 15(3), 315–336. doi:10.1080/10967494.2012.725318

- Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, K. (1995). The knowledge creating company: How Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Oliveira, M., Curado, C. M., Maçada, A. C., & Nodari, F. (2015). Using alternative scales to measure knowledge sharing behavior: Are there any differences? Computers in Human Behavior, 44, 132–140. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.042

- Pandey, S. K., & Bretschneider, S. I. (1997). The impact of red tape’s administrative delay on public organizations’ interest in new information technologies. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 7(1), 113–130. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024335

- Pavlou, P. A., & El Sawy, O. A. (2006). From IT leveraging competence to competitive advantage in turbulent environments: The case of new product development. Information Systems Research, 17(3), 198–227. doi:10.1287/isre.1060.0094

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

- Qian, Y., Wang, M., Zou, Y., Jin, R., Yuan, R., & Wang, Q. (2019). Understanding the double-level influence of Guanxi on construction innovation in China: The mediating role of interpersonal knowledge sharing and the cross-level moderating role of inter-organizational relationships. Sustainability, 11(6), 1657. doi:10.3390/su11061657

- Razmerita, L., Kirchner, K., & Nielsen, P. (2016). What factors influence knowledge sharing in organizations? A social dilemma perspective of social media communication. Journal of Knowledge Management, 20(6), 1225–1246. doi:10.1108/JKM-03-2016-0112

- Renzl, B. (2008). Trust in management and knowledge sharing: The mediating effects of fear and knowledge documentation. Omega, 36(2), 206–220. doi:10.1016/j.omega.2006.06.005

- Sandhu, M. S., Jain, K. K., & Ahmad, I. U. K. B. (2011). Knowledge sharing among public sector employees: Evidence from Malaysia. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 24(3), 206–226. doi:10.1108/09513551111121347

- Seba, I., Rowley, J., & Delbridge, R. (2012). Knowledge sharing in the Dubai police force. Journal of Knowledge Management, 16(1), 114–128. doi:10.1108/13673271211198972

- Sharratt, M., & Usoro, A. (2003). Understanding knowledge-sharing in online communities of practice. Electronic Journal on Knowledge Management, 1(2), 187–196.

- Silvi, R., & Cuganesan, S. (2006). Investigating the management of knowledge for competitive advantage: A strategic cost management perspective. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 7(3), 309–323. doi:10.1108/14691930610681429

- Straub, D. W. (1989). Validating instruments in MIS research. MIS Quarterly, 147–169. doi:10.2307/248922

- Tangaraja, G., Mohd Rasdi, R., Ismail, M., & Abu Samah, B. (2015). Fostering knowledge sharing behaviour among public sector managers: A proposed model for the Malaysian public service. Journal of Knowledge Management, 19(1), 121–140. doi:10.1108/JKM-11-2014-0449

- Taylor, W. A., & Wright, G. H. (2004). Organizational readiness for successful knowledge sharing: Challenges for public sector managers. Information Resources Management Journal, 17(2), 22. doi:10.4018/IRMJ

- Tohidinia, Z., & Mosakhani, M. (2010). Knowledge sharing behaviour and its predictors. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 110(4), 611–631. doi:10.1108/02635571011039052

- Torfing, J. (2019). Collaborative innovation in the public sector: The argument. Public Management Review, 21(1), 1–11. doi:10.1080/14719037.2018.1430248

- Trong Tuan, L. (2017). Knowledge sharing in public organizations: The roles of servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior. International Journal of Public Administration, 40(4), 361–373. doi:10.1080/01900692.2015.1113550

- Tsai, W. (2002). Social structure of “coopetition” within a multiunit organization: Coordination, competition, and intraorganizational knowledge sharing. Organization Science, 13(2), 179–190. doi:10.1287/orsc.13.2.179.536

- van Den Hooff, B., & De Ridder, J. A. (2004). Knowledge sharing in context: The influence of organizational commitment, communication climate and CMC use on knowledge sharing. Journal of Knowledge Management, 8(6), 117–130. doi:10.1108/13673270410567675

- Van Lange, P. A., Joireman, J., Parks, C. D., & Van Dijk, E. (2013). The psychology of social dilemmas: A review. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 120(2), 125–141. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2012.11.003

- Vong, S., Zo, H., & Ciganek, A. P. (2016). Knowledge sharing in the public sector: Empirical evidence from Cambodia. Information Development, 32(3), 409–423. doi:10.1177/0266666914553604

- Vuuren, S. J. V. (2011). Inter-organisational knowledge sharing in the public sector: The role of social capital and information and communication technology (PhD). Victoria University of Wellington.

- Wang, S., & Noe, R. A. (2010). Knowledge sharing: A review and directions for future research. Human Resource Management Review, 20(2), 115–131. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.10.001

- Wettenhall, R. (2003). Exploring types of public sector organizations: Past exercises and current issues. Public Organization Review, 3(3), 219–245. doi:10.1023/A:1025333414971

- Willem, A., & Buelens, M. (2007). Knowledge sharing in public sector organizations: The effect of organizational characteristics on interdepartmental knowledge sharing. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 17(4), 581–606. doi:10.1093/jopart/mul021

- Wolf, P. J. (1997). Why must we reinvent the federal government? Putting historical developmental claims to the test. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 7(3), 353–388. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024354

- Wong, K. Y., Tan, L. P., Lee, C. S., & Wong, W. P. (2013). Knowledge management performance measurement: Measures, approaches, trends and future directions. Information Development. doi:10.1177/0266666913513278

- Yao, L., Kam, T., & Chan, S. H. (2007). Knowledge sharing in Asian public administration sector: The case of Hong Kong. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 20(1), 51–69. doi:10.1108/17410390710717138

- Yiu, D., & Lin, J. (2002). Sharing tacit knowledge in Asia. Knowledge Management Review, 5, 10–11.

- Yousaf, M., Zafar, S., & Abi Ellahi, A. (2014). Do public service motivation, red tape and resigned work satisfaction triangulate together? International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 63(7), 923–945. doi:10.1108/IJPPM-06-2013-0123

- Yusof, Z. M., Ismail, M. B., Ahmad, K., & Yusof, M. M. (2012). Knowledge sharing in the public sector in Malaysia a proposed holistic model. Information Development, 28(1), 43–54. doi:10.1177/0266666911431475

- Zeffane, R. (1993). Uncertainty, participation and alienation: Lessons for workplace restructuring. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 13(5/6), 22–52. doi:10.1108/eb013174

- Zhang, J., & Dawes, S. S. (2006). Expectations and perceptions of benefits, barriers, and success in public sector knowledge networks. Public Performance & Management Review, 29(4), 433–466.

- Zhang, X., Lin, C.-H., Chung, K.-C., Tsai, F.-S., & Wu, R.-T. (2019). Knowledge sharing and co-opetition: Turning absorptive capacity into effectiveness in consumer electronics industries. Sustainability, 11(17), 4694. doi:10.3390/su11174694

- Zheng, W., Yang, B., & McLean, G. N. (2010). Linking organizational culture, structure, strategy, and organizational effectiveness: Mediating role of knowledge management. Journal of Business Research, 63(7), 763–771. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.06.005

- Zhu, Y.-Q. (2016). Solving knowledge sharing disparity: The role of team identification, organizational identification, and in-group bias. International Journal of Information Management, 36(6), 1174–1183. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2016.08.003