?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of the current paper is to provide a review of the researches on the most important typologies of entrepreneurial opportunities and to suggest an individual-based typology of entrepreneurial opportunities. Design/methodology/approach: The literature review method is used in the current paper to review the most important typologies of entrepreneurial opportunities and their contributions. Findings: Considering the three essential concepts of perceivability, exploitability, and desirability of entrepreneurial opportunities, this paper suggests an individual-based definition of the concept of entrepreneurial opportunity. In addition to the implications of the suggested framework for future studies and regarding its potential applications, the policies to move people from one domain of opportunity to another and also recommendations for entrepreneurs and investors are presented. Originality/value: This paper introduces the concept of opportunity domain, and suggests a three-level (domain) typology based on the role of individual(s) in identification and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Entrepreneurs are different in their talents and skills. Some succeed and some fail. The main question is why this is so. The answer is because they are different. Some cannot see the opportunity. Some cannot exploit it. And some, do not have desire to pursue it.

To exploit an opportunity, you should see it first, then make yourself qualified to exploit it, and there is no need to say that you should have passion about finding and exploiting that type of opportunity. The current paper discusses those factors which cause people to perceive the opportunities and exploit them. The people are different. The opportunities are different too. Consequently, entrepreneurship happens when the right person meets the right opportunity.

1. Introduction

Some scholars (e.g., Companys & McMullen, Citation2007) believe that the development of the construct of opportunity is critical to the study of entrepreneurship and this construct has the potential to drive the field of entrepreneurship to a unified conceptual framework (Rubleske & Berente, Citation2017). Others disagree with the opinion that opportunity can be the main phenomenon of interest in the field of entrepreneurship (Kitching & Rouse, Citation2017; Klein & Foss, Citation2008). Despite the so-called discussions, opportunity is increasingly becoming the most unique domain of entrepreneurship research and it helps reveal the fruitful avenues for future researches (Busenitz, Plummer, Klotz, Shahzad, & Rhoads, Citation2014). Therefore, entrepreneurial opportunity has become, if not the central concept, at least a very important one in the entrepreneurship field. Further, the opportunity-centered approach is in need of organizing frameworks. It seems that theorizing attempts should focus on the nature of opportunities and their characters, instead of addressing empirical aspects of the construct (Companys & McMullen, Citation2007).

The current typologies in the literature are targeted at different aspects of opportunities ranging from the typologies that stress the nature of opportunities such as discovered or created (Alvarez & Barney, Citation2007), Schumpeterian versus Kirznerian opportunities (De Jong & Marsili, Citation2011), the ones that emphasize the sources of opportunities (Companys & McMullen, Citation2007; Eckhardt & Shane, Citation2003; Fuduric, Citation2008; Holcombe, Citation2003; Shane, Citation2003), those that look into the uncertainty and the information about markets (Sarasvathy, Dew, Velamuri, & Venkataraman, Citation2003), to the typologies that are focused on tacitness or codification of opportunities (Smith, Matthews, & Schenkel, Citation2009) and so on.

Part of the gap in the literature concerns the lack of clarity in the construct of opportunity (Davidsson, Citation2015). Most of the existing literature is based on general definition(s) of entrepreneurial opportunity in which the essential role of the person who acts on opportunity remains underestimated. New insights in psychology indicate that people vary in terms of attention and ability to understand some phenomena. They are sometimes blind to some issues and sometimes are even blind to their blindness. These findings support the long-lasting belief about the difference between people. Therefore, it is not surprising that some people are not able to see a situation as an opportunity. They are not able to see some phenomena, understand their meanings or the possibility of gaining profit; therefore, these situations cannot be considered as opportunities for them. The literature on recognition of entrepreneurial opportunities shows that this research field is fragmented and underdeveloped (Mary George, Parida, Lahti, & Wincent, Citation2016).

This paper, reviewing the most important typologies of entrepreneurial opportunities and emphasizing the role of individuals in the identification and exploitation of opportunities, suggests a new typology, based on the concept of opportunity domain. The contributions of the current paper are as follows: First, reviewing the most important studies about the types of entrepreneurial opportunities and considering the essential concepts of perceivability, exploitability, and desirability of entrepreneurial opportunities, this paper suggests an individual-based definition of the concept of entrepreneurial opportunity and attempts to introduce the concept of opportunity domain. Second, it suggests a three-level (three domain) typology based on the individuals’ abilities to identify and exploit opportunities and thus it discusses the important implications of each domain of the suggested framework. Finally, the paper concludes with a discussion of the important factors which affect the exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities and proposes policies to move the individuals form one domain of opportunity to another.

The structure of the paper is as follows: the next section provides a review of the most important typologies of entrepreneurial opportunities. The third section addresses entrepreneurial ability and the role of individual-opportunity nexus in determining a situation as an entrepreneurial opportunity. The fourth section suggests a typology based on the role of individual and the attributes of the opportunity. Finally, the implications of the suggested framework for the researchers, entrepreneurs, investors and policy makers are presented in section five.

2. Current typologies

2.1. Discovery opportunities and create opportunities

Discovery theory is the dominant view in entrepreneurship field (Korsgaard, Citation2013). It is argued in previous researches that entrepreneurial opportunities exist primarily because different individuals have different beliefs about the values of resources (Kirzner, Citation1997). The roots of the discovery view are in Austrian economics (Kirzner, Citation1997). These opportunities have sources: technological changes, political and regulatory changes and social/demographic changes which disrupt the equilibrium of the market or industry, and thereby form the opportunities (Shane, Citation2003). Discovery theory is based on realistic assumptions in philosophy of science: the assumption that opportunities exist as real and as objective phenomena, independent of what the entrepreneurs do (McKelvey, Citation1999).

An important assumption in discovery view is the difference between entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs. Discovery view assumes that entrepreneurs are different from other people regarding the ability to discover and exploit opportunities (Shane, Citation2003). This different quality of entrepreneurs is known by Kirzner (Citation1973) as alertness, which reflects the entrepreneur’s prior knowledge (Kirzner, Citation1997). Prior knowledge heightens entrepreneur’s alertness to potential opportunities. According to Alvarez and Barney (Citation2007), the individual-opportunity nexus explains entrepreneurship by considering the nexus of special individuals and the opportunities that are objective. In this case, individuals discover opportunities and apply new means-ends frameworks for recombination of resources.

Another view with different assumptions about opportunities and entrepreneurs is the creation view. Sarasvathy (Citation2001) suggests that opportunities are created by entrepreneurs. Sarasvathy et al. (Citation2003) adopt purely subjective and purely objective ontological stances to define entrepreneurial opportunity. In this view, the opportunity has no meaning before the acts of the actors upon the real world. According to Buenstorf (Citation2007), entrepreneurial opportunities are created by the activities of human agents. Individuals may intentionally create these opportunities, but these opportunities are unintended effects of the activities people do by non-economic motivations. There is a difference between the higher order opportunity (an opportunity to create opportunity) and the opportunity itself. Higher order opportunities provide the basis for new opportunities.

2.2. Economic, cultural cognitive, and sociopolitical opportunities

Companys and McMullen (Citation2007) classify entrepreneurial opportunities as economic, cultural-cognitive, and sociopolitical opportunities. The economic school focuses on the objective dimensions of knowledge and information. Here, the existence of entrepreneurial opportunities depends on how the information is distributed in the society. In cultural cognitive school, opportunities are cultural innovations which are offered by producers or consumers into the marketplace. In sociopolitical school, opportunities are the results of features in the structure of social network and political opportunities relate to the changes in the structure of the governance in the network. Given that the exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities depends on the entrepreneur’s political skills and their ability to encourage other people to commercialize successfully, these opportunities are subjective social network structures. Consequently, entrepreneurial opportunity is a potential for profit which might arise from one of the three types of changes: (1) changes in data about material resources, (2) changes in interpretations (preferences), or (3) changes in interpreters (McMullen, Plummer, & Acs, Citation2007).

2.3. Kirznerian and Schumpeterian opportunities

Many scholars in entrepreneurship together with the researchers in the Austrian economics literature, have extensively elaborated on the elements that distinguish Schumpeterian and Kirznerian views (De Jong & Marsili, Citation2011). For example, Shane (Citation2003) proposed a framework in summarizing these perspectives into a typology of entrepreneurial opportunities. De Jong and Marsili (Citation2011) assess Schumpeterian/Kirznerian opportunity types based on five bipolar dimensions previously proposed by Shane (Citation2003): disequilibrating-equilibrating, new information-no new information, very innovative-less innovative, rare-common, and creation-discovery.

The results of empirical studies show that Schumpeterian and Kirznerian opportunities coexist. These opportunities can be identified on the basis of distinct dimensions and are pursued by different individuals. Schumpeterian-Kirznerian typology can be a useful tool to illustrate the various aspects of the entrepreneurial process (De Jong & Marsili, Citation2011). The disequiliberating nature of Schumpeterian opportunities makes them more valuable than Kirznerian opportunities (Shane, Citation2003). Moreover, regarding the discovery, evaluation, and exploitation of opportunities Schumpeterian and Kirznerian opportunities are different. Schumpeterian opportunities are innovation-based and rooted in the existing knowledge, while Kirznerian opportunities are not very innovative and they replicate the existing organizational forms. As a consequence, the risks associated with Schumpeterian opportunities should be higher than the risks associated with Kirznerian opportunities.

2.4. Exploration-based and exploitation-based opportunities

Vives and Nedeva (Citation2007) suggested another typology of entrepreneurial opportunities. Opportunities can stem from exploration which is the effect of development of new knowledge or might be the result of exploitation, in which leverage is used to the existing knowledge. Exploration-based sources of entrepreneurial opportunities include opportunity discovery (identification of a demand side in need for supply, or vice-versa) and opportunity creation (some product or service offering is invented). In exploitation-based sources of entrepreneurial opportunities, the focus is on opportunity recognition (including the recognition of a demand which can be satisfied via the existing supply), opportunity replication (duplication of the existing means-ends relationship), and opportunity brokerage (bringing together two or more unconnected parties).

2.5. Imitation, allocation, discovery, and construction opportunities

Hunter (Citation2013) depicts entrepreneurial opportunity as a nexus of the ebb and flow of the environment and personal, family, and business dispositions of people, which are reflected in their personal knowledge. Entrepreneurial opportunity may exist within four types; imitation, allocation, discovery, and construction. Imitation opportunities are those known activities undertaken in a geographic or customer space, their focus is operational and are identified through observing other successful businesses or replication. To exploit these opportunities, the assumption of the entrepreneur is that the selected business model and type will work in the selected market-place and the uncertainty is managed through imitation. Allocation opportunity is the possibility of getting space in a market via finding mismatches of demand/supply and demographics, employing resources to exploit these mismatches. Opportunities are recognized through deductive reasoning. Entrepreneur believes in information/data and uncertainty is managed through product portfolio diversification. The third type addresses discovery opportunities which are the possibility of taking advantage of potentially identified market gaps due to technology, social issues, regulation, or economic situations. The focus of these opportunities is on potential market space and developing exploitive strategies. Opportunities are discovered through inductive reasoning. Entrepreneur’s assumption is that new market space exists from the incongruity or structural changes in industry. Uncertainty is often managed through the control of channels, networks, adequate resources, and experimentation. The desired outcome is the creation of new market space, being different from competitors and avoiding failure. The final type of opportunities is construction opportunities. These are possibilities of creating (new) ends through new means emerged through strategies and feedback. These opportunities are constructed through intuitive and abductive reasoning, trial & error and experimentation. The uncertainty is managed through effectuation using different cognitive styles and experimentation. The desired outcome is a viable new product, service or business model that is differentiated from competitors (Hunter, Citation2013).

2.6. Locus of the changes, the source, and the initiator of the change

According to Eckhardt and Shane (Citation2003), the previous studies have offered three ways for the categorization of opportunities: opportunities generated by the locus of the changes; by the source of the opportunities; and by the initiator of the change. Five different loci of changes are the creation of new products or services, discovery of new geographical markets, creation or discovery of new raw materials, new methods of production, and new ways of organizing. The previous researches also have suggested four important ways for the categorization of the opportunities regarding their sources. The first category relates to the differences between opportunities that are the results of asymmetries in the existing information between the participants in the market and opportunities that are the result of the exogenous shocks of new information. The second one relates to the supply and demand side. The third category differentiates between productivity-enhancing and rent-seeking opportunities. Finally, “the fourth category lies in identifying the catalysts of change that generate the opportunities” (Eckhardt & Shane, Citation2003, p. 341). Opportunities can also be classified based on whether the changes that generate them exist on the demand side or on the supply side. A final dimension is the initiator of the change. “Different types of entities initiate the changes that result in entrepreneurial opportunities, and the type of initiator is likely to influence the process of discovery as well as the value and duration of the opportunities” (Eckhardt & Shane, Citation2003, p. 344).

2.7. Codification and tacitness

Smith et al. (Citation2009), suggested another typology based on the codification or tacitness of opportunity. Codified opportunity is a well-documented, articulated, or communicated profit-seeking situation in which a person seeks to exploit market inefficiency in a less-than-saturated market. By comparison, a tacit opportunity is a profit-seeking situation that is difficult to codify, articulate, or communicate, in which a person seeks to exploit market inefficiency in a less than- saturated market.

2.8. Actual opportunities and perceived opportunities

Renko, Shrader, and Simon (Citation2012) presented a framework for opportunity perception. They distinguished between opportunity perception and opportunity identification and believe that opportunity perception is theoretically a more precise label, which can reconcile diverse, yet equally valid, theoretic perspectives. They distinguished between the actual opportunities and perceived opportunities. These opportunities may have overlaps or can be separated. The possible modes of the relation between the actual and the perceived opportunities are as follows:

Missed opportunity (opportunity exists but not perceived).

False perception (opportunity perceived but no actual opportunity exists).

Missed mark (perceived opportunity does not reflect actual opportunity).

Partially perceived opportunity.

Overestimated opportunity.

Underestimated opportunity.

Actually perceived opportunity.

2.9. Productive, unproductive, and destructive opportunities

Another typology of entrepreneurial opportunities belongs to Baumol (Citation1990). Using the historical approach, Baumol (Citation1990), intended to suggest a non-mathematical theory of entrepreneurship in general. To do so, he built upon the schumpeterian framework, using innovative activity as the main characteristic of entrepreneurship. In his framework, entrepreneurs are motivated by the pursuit of profit. Depending on the relative payoffs, entrepreneurial ability is distributed among the productive, unproductive, and destructive activities. Rent-seeking, organized-crimes, expansion of warfare, and bureaucracy are all instances of unproductive and destructive entrepreneurship forms. The main factor which determines the payoffs for the different forms of entrepreneurship is the institutional environment (rules of the game), which changes from one time and place to another. As was previously described, Eckhardt and Shane (Citation2003), also pointed to the productivity-enhancing versus rent-seeking opportunities. When we discuss entrepreneurship, we mean productive entrepreneurship, but there are opportunities that generate personal value, without social value. An example of this type of opportunities is merger. If a merger only reduces the competition and moves wealth from the consumers to the producers, this is an unproductive form of opportunity. Baumol did not point to the productive, unproductive and destructive entrepreneurship as types of opportunities. However, from his discussions, the situation in which an entrepreneur acts to pursuit profit (whether productive or un-productive) can be considered as an opportunity. Therefore, there are three types of entrepreneurial opportunities depending on the motivations of the entrepreneurs and the social payoffs of the entrepreneurship: productive entrepreneurial opportunities, un-productive entrepreneurial opportunities, and destructive entrepreneurial opportunities.

2.10. Replication/reinterpretation opportunities and revelation/revolution opportunities

Based on different combinations of the old and new means/ends in exploiting entrepreneurial opportunities, Wood, Welter, Artz, and Bradley (Citation2014) suggested a typology of entrepreneurial opportunities. Each combination comprises an opportunity type. These types include replication, reinterpretation, revelation, and revolution. In replication, the existing means are applied to the existing ends. In this type of opportunities, the existing means/ends relationships are applied in a specific geographic location or to a new market. Replication opportunities are the least imaginative type. Franchising is an example of this type. In revelation type opportunities, new means are applied to the existing ends involving optimization with the existing ends frameworks. This type of opportunities are information-based that involves a discovery process. Reinterpretation opportunity types involove conceptualizing how the existing means can be applied to new ends. It needs an individual to think about how to use the existing means to produce new products or services. Therefore, it involves a creative and interpretive endeavor. The last type of opportunities are revolution opportunities in which the entrepreneur conceptualizes a new end whose production requires novel means. This type of opportunities is based on radical innovations which generally do not have clear markets. Therefore, the entrepreneur is a change agent and should create a new market for his/her new product or service. Regarding the degree of innovation, risk, and supply/demand side, this typology is very similar to that of Hunter (Citation2013) and Sarasvathy et al. (Citation2003). The most important point about the typology of Wood et al. (Citation2014) is that for the conceptualization of these combinations of means/ends, human agency is needed and this typology along with the other typologies mentioned above highlights the role of individuals in the entrepreneurial process.

As discussed above, the previous studies about the entrepreneurial opportunities addressed two main subjects: first, the nature and the characteristics of entrepreneurial opportunities and second, the characteristics of the individuals who perceive and exploit those opportunities. In the following sections, we will take a closer look at both themes.

3. Entrepreneurial ability and the role of individuals in the identification and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities

So far, the literature has proceeded with the enumeration of the differences between the entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs in some important ways (Busenitz & Barney, Citation1997; Hornaday & Aboud, Citation1971), and differences among entrepreneurs (Baron, Citation1998; Gaglio & Katz, Citation2001). The researchers tried to show that people think differently and the difference in thinking results in the differences between non-entrepreneurs and entrepreneurs. These differences are in fact the differences in the entrepreneurial ability.

“Entrepreneurial ability is a wide term and refers to the ability of individuals to perceive, and exploit business opportunities” (Burke, Fitzroy, & Nolan, Citation2002, p. 255). Two important elements of this definition are the ability to perceive entrepreneurial opportunities and the ability to exploit entrepreneurial opportunities. According to Burke et al. (Citation2002), entrepreneurial ability is a wide term, therefore a wide range of factors are mentioned in the literature as affecting these abilities. Trying to indicate the important role of individuals in pursuing entrepreneurial opportunities, we look at each separately.

3.1. Perception of opportunity

According to Shane (Citation2003), opportunities lack agency and entrepreneurship requires a decision by a person to act upon them. On the other hand, because the act of discovery is cognitive, the discovery of an opportunity is an act carried out by individuals and not by groups or firms. The factors which affect the opportunity discovery include access to information and opportunity recognition. Access to information is influenced by life experiences in the forms of job functions and variation in experiences, searching processes (for relevant information rather than random efforts), and social networks. Opportunity recognition is also influenced by absorptive capacity, intelligence, and cognitive properties.

People in different theories are treated as being different in their ability to perceive opportunities. Discovery entrepreneurs are different from non-entrepreneurs in some important ways; while entrepreneurs in creation theory may or may not be different from non-entrepreneurs. Furthermore, if opportunities exist as objective phenomena, then the task of the ambitious entrepreneur is to discover these opportunities and exploit them as quickly as possible, before other entrepreneurs can discover and exploit the opportunity. Assuming that opportunities are created rather than discovered has important implications for the entrepreneurial action. For instance, instead of searching for an opportunity to exploit, entrepreneurs who create opportunities might engage in a learning process. This process is iterative and this may lead to the formation of an opportunity (Alvarez & Barney, Citation2007). According to Shane and Venkataraman (Citation2000), opportunity recognition is influenced by an individual’s idiosyncratic prior knowledge. Information about the underutilized resources, new technology, unsated demand, and the political and regulatory shifts rather than being perfectly distributed has a dispersed distribution (Shane & Venkataraman, Citation2000). In addition to Shane (Citation2003), other researchers suggested prior knowledge as an influencing factor for opportunity identification. Smith et al. (Citation2009) suggested a continuum of entrepreneurial opportunities ranging from codified to tacit. They focus on the importance of differences in opportunities instead of individual differences for the recognition and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities. “Codified opportunity is well documented, articulated or communicated profit-seeking situation in which a person seeks to exploit market inefficiency in a less-than-saturated market. By comparison, a tacit opportunity is a profit-seeking situation that is difficult to codify, articulate or communicate … “ (Smith et al., Citation2009, p. 20). Having prior knowledge or lack of it influences opportunity identification. In case of tacit opportunities, having prior knowledge leads to the discovery of opportunity while lacking prior knowledge leads to overlooking it. Having prior knowledge in case of the codified opportunities causes the individual to do a focused search while lacking it leads to the systematic search. Hulbert, Gilmore, and Carson (Citation2013), acknowledged prior knowledge and alertness as influencing factors for opportunity identification. Corbett (Citation2007) suggests that learning processes in the form of how individuals acquire and transform information as well as experience influences opportunity identification. Habitual entrepreneurs identify more opportunities than novice entrepreneurs because of the higher information search. In addition to prior knowledge, entrepreneurial alertness has gained attention in the literature. Entrepreneurial alertness is defined as “The ability to notice without search opportunities that have hitherto been overlooked” (Kirzner, Citation1997, p. 48). Valliere (Citation2013) proceeded to the mechanism and antecedents of the concept of entrepreneurial alertness. He looked at entrepreneurial alertness as using schemata to make sense of the world. Schematic richness, schematic association, and schematic priming are the main antecedents of entrepreneurial alertness. Similarly, Baron and Ensley (Citation2006) state that what causes entrepreneurial alertness is the cognitive ability of the person to understand that a situation is similar to another situation and, in abstract level, both situations have the same pattern or cognitive framework. In conclusion, it can be said that people are different in their abilities to perceive entrepreneurial opportunities. Someone sees a situation as an opportunity and someone does not. So a situation might be an entrepreneurial opportunity for someone who sees it as an opportunity but certainly, it is not an opportunity for someone who cannot see it. In short, for those who do not see a situation as an opportunity (as was discussed above, it is impossible for him/her to perceive the situation as an opportunity), there is no opportunity subjectively or objectively.

3.2. Exploitation of opportunity

After someone perceives a situation as an entrepreneurial opportunity he/she must decide about the exploitation of that opportunity. Like the perception of opportunity, the exploitation also depends on individual differences. As was discussed in the previous section, the factors which affect the perception of entrepreneurial opportunities include alertness (Kirzner, Citation1973; Shackle, Citation1979), knowledge of the markets (e.g., Shane, Citation2003) greater access to information together with the ability to analyze information (McGuire, Citation1976) and education (e.g., Schultz, Citation1980). The factors which affect exploitation of the opportunities are the same factors. In addition, factors like greater business contacts, work experience, motivation (McClelland, Citation1965), and non-pecuniary motivation (Burke et al., Citation2002) also affects the exploitation of an entrepreneurial opportunity. People are different in their ability to exploit opportunities. (Shane, Citation2003, p. 61) defines individual differences as “any type of variation among people, whether in their demographic characteristics such as age or education or in their psychological make-up, such as motivation, personalities, core self-evaluation or cognitive processing”. He divides these factors into two groups: non-psychological factors and psychological factors. Non-psychological factors are individual-level attributes like education, career experiences, age, social position, and opportunity cost which are related to the exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities. For an entrepreneur to exploit entrepreneurial opportunity, his/her expected utility of exploiting opportunity must be greater than the opportunity cost of other activities. The level of opportunity cost is influenced by income and unemployment. Being married and having a working spouse also affects the decision to exploit an entrepreneurial opportunity. As in the case of opportunity perception, education influences the exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities. Career experiences in the forms of general business experiences, functional experiences, industry experiences, start-up experiences, and vicarious experiences affect the exploit decision via the development of information and skills that facilitate resource acquisition, strategy formulation, and organizing process. According to (Shane, Citation2003), psychological characteristics causes people with the same information and skills to make different decisions about exploiting the entrepreneurial opportunities. These factors can be organized into three groups: aspects of personality and motives, core self-evaluation, and cognitive characteristics. Personality and motives include extraversion, agreeableness, need for achievement, risk-taking, and the desire for independence. Core self-evaluation includes the two factors of locus of control, and self-efficacy. Cognitive characteristics also include overconfidence, representativeness, and intuition. There are many other factors in the literature, which are mentioned as the influencing factors of the decision to exploit entrepreneurial opportunities.

3.3. Desirability of opportunity

In addition to two elements of entrepreneurial ability, there is another element which affects both the perception and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities. Shane, Locke, and Collins (Citation2003) believe that to develop entrepreneurship theory, the motivations of entrepreneurial decision-making should be considered. Entrepreneurial motivation has been ignored for almost two decades (Carsrud & Brännback, Citation2011). Entrepreneurial motivation includes both the recognition and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities (Locke & Baum, Citation2007). Knowledge without motivation leads to nowhere and motivation without knowledge results in nonproductive action. According to Locke and Baum (Citation2007), researches in entrepreneurship involve studying both cognition and motivation. In normal human action, motivation (desire) and cognition (knowledge, belief) operate together. One of the concepts which is related to motivational factors in entrepreneurship literature is desirability. According to Krueger, Reilly, and Carsrud (Citation2000), economic development in the form of new businesses needs to increase the perceptions of desirability and feasibility. The concept of desirability is the personal attractiveness of starting a business (Shapero & Sokol, Citation1982) or the degree of attractiveness of behavior (to become entrepreneur) for a person (Liñán, Citation2004). Desirability concept is used in the literature in association with a particular behavior (the desirability of starting a business). Considering the widely accepted definition of entrepreneurship which implies that entrepreneurship is an activity that involves the discovery, evaluation, and exploitation of opportunities (Shane & Venkataraman, Citation2000), the desirability of starting an entrepreneurial business is oriented toward the opportunity. The concept of desirability has been used in entrepreneurial intention models (e.g., Shapero & Sokol, Citation1982) and it is correspondent to the concepts of “attitude toward behavior” and “subjective norms” (Krueger et al., Citation2000). So, the desirability of entrepreneurial action is the product of two types of attitudes (or attraction of the action for two sides): first, it should be attractive for a person who intends to act on opportunity (entrepreneur), second, for those people (reference people including colleagues, instant family members, and friends) whose attitudes toward the exploitation of opportunity is important for that person. Many factors influence desirability and the role of some of these factors on the desirability of entrepreneurial choice have been discussed in the literature. For instance, prior entrepreneurial exposure as well as education (Liñán, Citation2004) affects the perceived desirability of the new venture (Krueger, Citation1993). In the literature, profit is one of the main elements of opportunity. It seems that the motivation of all human actions is profit (Homans, Citation1974). Entrepreneurs and their search for opportunities are driven by a profit motive. So, the existence of profit opportunities is the main motivation behind the entrepreneurial activity (Sautet, Citation2002). As was discussed earlier, in addition to the two essential elements of entrepreneurial ability (the concepts of perception and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunity), because of the important influence of desirability on exploiting entrepreneurial opportunity, this concept is also used in the suggested framework.

3.4. Cultural factors

Cultural factors have a strong influence on entrepreneurial activities. However, in case of entrepreneurial ability, we might consider those factors which affect recognizing, evaluating, and exploiting entrepreneurial opportunities at individual level. At this level, cultural factors influence the elements of entrepreneurial ability (Al-Shammari & Al-Shammari, Citation2018b; Hamid, Everett, & O’Kane, Citation2018).

The most important investigations of cultural factors which influence entrepreneurial ability have been conducted in studies on immigrant entrepreneurs (e.g., Al-Shammari & Al-Shammari, Citation2018a; Alvarado, Citation2018; Bolívar-Cruz, Batista-Canino, & Hormiga, Citation2014; Smans, Freeman, & Thomas, Citation2014; Vinogradov & Jørgensen, Citation2017).

Regarding cultural factors, there are two types of entrepreneurs: mono-cultural entrepreneurs and bicultural entrepreneurs (Al-Shammari & Al-Shammari, Citation2018b; Luna, Ringberg, & Peracchio, Citation2008). Bicultural entrepreneurs have multiple cognitive abilities and skills and different perspectives and experiences of two different cultures which place them in a better position to recognize, evaluate, and sometimes to exploit entrepreneurial opportunities (Al-Shammari & Al-Shammari, Citation2018b). Biculturalism affects three main phases of entrepreneurship (Shane & Venkataraman, Citation2000): recognition, evaluation, and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities. Bicultural entrepreneurs identify entrepreneurial opportunities better than mono-cultural entrepreneurs and are more likely to evaluate opportunities positively (Al-Shammari & Al-Shammari, Citation2018b). Al-Shammari and Al-Shammari (Citation2018b) proposed general culture awareness, acceptance, bicultural efficacy, dual fluency, broad role repertoire, and groundedness as bicultural competencies which influence entrepreneurial thoughts and orientation. It can be concluded that creating these competencies in mono-cultural entrepreneurs is a good way to increase the likelihood of entrepreneurship among this type of entrepreneurs. However, these competencies are not obtainable through short-term cross-cultural training or exposure to a different culture.

In summary, the definition of entrepreneurship involves the concept of opportunity as the main element (e.g. Aldrich & Cliff, Citation2003; Companys & McMullen, Citation2007; Shane & Venkataraman, Citation2000). To date, different definitions of entrepreneurship have been suggested in the literature. However, it seems that the field of entrepreneurship has adopted the definition of entrepreneurship which is suggested by Shane and Venkataraman (Citation2000, p. 218), “the study of sources of opportunities; the processes of discovery, evaluation, and exploitation of opportunities; and the set of individuals who discover, evaluate, and exploit them” as the conceptual definition (Shane, Citation2012). There are also many different definitions of entrepreneurial opportunity. Casson (Citation1982, p. 220), defines entrepreneurial opportunity as ” those situations in which, new goods, services, raw materials, and organizing methods can be introduced and sold at greater than their cost of production”. Shane (Citation2003, p. 18), defines entrepreneurial opportunity as “ a situation in which a person can create a new means-ends frameworks for recombining resources that entrepreneurs believes will yield a profit”. There are common threads among the different definitions of entrepreneurial opportunity. Among the common elements are: entrepreneur, situation, and profit (Hansen, Shrader, & Monllor, Citation2011). Individuals (entrepreneurs) are the most used element in definitions of entrepreneurial opportunity (Hansen et al., Citation2011). For this reason, the suggested definition of entrepreneurial opportunity (and typology) in the current paper is based on individuals.

Situation is the second most used element in the definition of entrepreneurial opportunity (Hansen et al., Citation2011). Researchers usually point to “a situation” in the definitions of entrepreneurial opportunity and then attribute some features to the so-called situation. These situations might exist but their existence and number are different for different people. One of the almost common features of “situation(s)” in the definitions of entrepreneurial opportunity is profit and most of the definitions of entrepreneurial opportunity in the literature point to opportunities as profit opportunities (e.g., Kirzner, Citation1973, Citation1997; Sautet, Citation2002). Researchers occasionally mention profit as one of the central elements of opportunity. For instance, according to (Baron, Citation2006), the three central characteristics of an opportunity are profit, newness, and perceived desirability. Some authors explicitly contrast entrepreneurial opportunity with other forms of opportunities for profit (Eckhardt & Shane, Citation2003). Regarding the difference between the entrepreneurial opportunity and other forms of opportunities for profit (Eckhardt & Shane, Citation2003), the question arises that whether entrepreneurial opportunities are a sub-set of all opportunities for profit (Plummer, Haynie, & Godesiabois, Citation2007). Opportunities are aspects of the environment that represent potentialities for profit making (Shane et al., Citation2003) and all human actions are motivated by profit (Homans, Citation1974). Entrepreneurs and their search for opportunities are driven by a profit motive. So, the existence of profit is the main motivation behind the entrepreneurial activity (Sautet, Citation2002). In summary, individual, situation, and profit are the main elements of the current definitions of entrepreneurial opportunity, but it seems that a clearer definition of what makes an opportunity entrepreneurial is needed (De Jong & Marsili, Citation2011; Plummer et al., Citation2007)

This paper intends to highlight the point that entrepreneurial opportunity must be defined in terms of the individual who perceives the opportunity and has the ability and motivation to exploit it. A situation which is a valuable opportunity for a person might not be perceivable, exploitable, or desirable for someone else. Therefore, the role of the individual is essential not only in the perception/exploitation of an entrepreneurial opportunity but in determining it as an opportunity for that person. This paper suggests that the definition of entrepreneurial opportunity be revised with regard to the role of a person who acts on it. The definition of entrepreneurial opportunity can include the perceivability, exploitabitabilty, and desirability to reflect the features of an entrepreneur who acts on opportunity. Therefore, we suggest that the term “ a situation” in the previous definitions might be revised in the form of “a situation which is perceivable, desirable and exploitable for a person”. We will use these concepts in the next section to suggest a tentative framework in which each concept is used as the basis for each opportunity domain.

4. Suggested framework

This paper suggests a framework to classify entrepreneurial opportunities based on differences among individuals. These differences form a set of opportunities for an individual or a set of individuals, out of which, it is almost impossible for him/her to identify or exploit an opportunity. We call these set of opportunities an opportunity domain. Considering the prior studies including the typologies of entrepreneurial opportunities, the nature of entrepreneurial opportunities and the nexus of individual-opportunity, the suggested framework classifies entrepreneurial opportunities into three types (three levels).

Regarding the characteristics of the individuals, these opportunity types can be considered as a set of opportunities which have attributes that make them perceivable, exploitable or desirable for a particular person or a group of people. Each set of opportunities (each type/level) can be considered as a domain which involves different opportunities. These types/levels include 1- opportunities-for-all domain (all opportunities for all people), 2- opportunities-for-some-people domain (i.e., all the opportunities for a group of people with particular abilities), 3- opportunities-for-a-particular-individual domain (opportunities for a particular individual that is perceivable/exploitable/desirable for him or her). The third domain/level has three subtypes that is called perceivable-opportunities-for-a-particular-individual domain, exploitable-opportunities-for a-particular-individual domain, and, desirable-opportunities-for-a-particular-individual domain. An important point here is that these levels/domains are not stable, but they change over time and each domain is sometimes extended (or limited) depending on the development or decline in abilities or the motivations of the person.

4.1. Opportunities-for-all domain

According to Kirzner (Citation1973), we can imagine a fixed stock of profit opportunities that get used up as entrepreneurs discover them. We can imagine a pool of opportunities of which entrepreneurs draw, but as entrepreneurs act, economy approaches equilibrium and the remaining number of entrepreneurial opportunities is reduced. It seems that the more entrepreneurial activities there is, the few entrepreneurial opportunities will be available. However, this is not correct and each entrepreneurial action creates more entrepreneurial opportunities, and as entrepreneurship takes place, the pool of entrepreneurial opportunities increases (Holcombe, Citation2003).

The most important factor for the creation of entrepreneurial opportunities is entrepreneurial action. The exploitation of a new entrepreneurial opportunity by an entrepreneur creates new market possibilities. Creation of a new product makes possible complementary products. Then, the demand for inputs for the new product increases. Finding a better process for the production of existing product results in the creation of opportunities for potential input suppliers. Thus, the entrepreneurial opportunities are not used up as entrepreneurs exploit them. By exploiting an opportunity, additional entrepreneurial opportunities are created. Therefore, the existence of more entrepreneurial actions in economy will result in more entrepreneurial opportunities for other entrepreneurs (Holcombe, Citation2003).

Both discovery and creation theories assume that the goal of entrepreneurs is to form and exploit opportunities (Shane, Citation2003; Shane & Venkataraman, Citation2000). Opportunities-for-all domain can be defined as the set of all opportunities or the total sum of all opportunities which are the results of imperfections in all markets/industries and are available for and can be exploited by all people, regardless of their abilities and characteristics which enable them to identify, evaluate, and exploit opportunities. In other words, opportunities at this level are all the potential opportunities for all the people.

Entrepreneurial opportunities “are those situations in which new goods, raw materials, and organizing methods can be introduced and sold at greater than their cost of production” (Shane & Venkataraman, Citation2000, p. 220). In opportunities-for-all domain, opportunities can be classified according to attributes such as industry or market in which the opportunity lies in. An important point here is that Schumpeterian opportunities and Kirznerian opportunities coexist. Schumpeterian opportunities are innovation-based and have roots in existing knowledge while Kirznerian opportunities are not very innovative and replicate the existing organizational forms. The qualities that determine which group of people identify, evaluate, and exploit opportunities make the next type of opportunities.

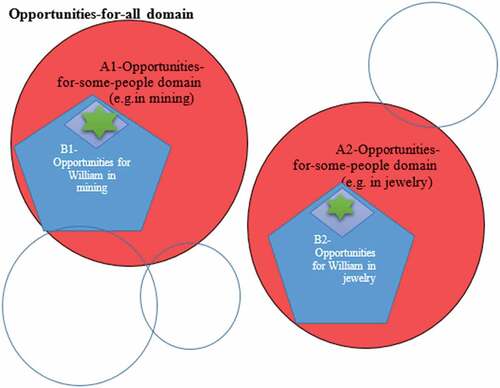

As depicted in Figure , the rectangle indicates opportunities-for-all domain. The circles are opportunities-for-some-people domain and the pentagons named B1 and B2, and many other pentagons that are not depicted, are opportunities-for-a-particular individual. The rectangle is the union of circles A1 and A2, and many other circles which are not depicted. In the real world, there are lots of these circles which comprise the opportunities-for-all domain. Each circle which corresponds to opportunities-for-some-people domain (for instance circle A1 or A2) can be considered as an industry or a market in the real world.

4.2. Opportunities-for-some-people domain

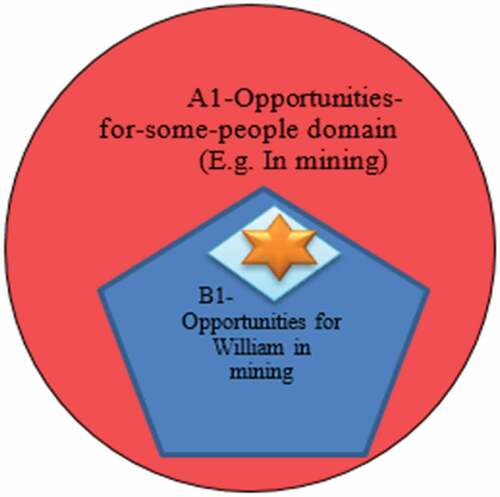

The opportunities inside this domain are only perceivable and exploitable for some people with certain qualities, regardless of having a desire to select a certain kind of opportunity, willingness, or motivation to discover and exploit opportunities or even to become entrepreneur. This domain is simply a domain that instead of being distinguished by the types of opportunities included, can be better distinguished by the types of opportunities that it does not include. But, what determines that if an opportunity lies within the boundaries of a certain domain? The answer is the abilities. These abilities mainly include abilities for the perception and abilities for exploitation of a certain kind of entrepreneurial opportunities. The opportunities in these domains are groups of special opportunities for special groups of people. As depicted in Figure , each circle inside the rectangle (for instance, circle A1 and A2 (and many other circles that are not depicted)) represents the opportunities-for-some-people domains.

People possess different stocks of information and these different stocks of information influence their abilities to recognize particular opportunities. The stocks of information create mental schemas which provide a framework for recognizing new information. At any time, only a subset of the population will be able to discover a given opportunity (Kirzner, Citation1973). Although an opportunity for entrepreneurial profit might exist, a person will earn this profit only if he or she recognizes that the opportunity exists and has value (Hayek, Citation1945). As was discussed in the previous sections, differences between people influence the opportunities that they discover and how their entrepreneurial efforts are organized. People will discover different opportunities in a given change, because they possess different prior knowledge (Venkataraman, Citation1997). They must be able to identify new means-ends relationships that are generated by a given change in order to discover opportunities. Even if a person possesses the prior information necessary to discover an opportunity, he or she may fail to do so because of inability to see new means-ends relationships (Shane, Citation2000). In addition, the abilities required to exploit an entrepreneurial opportunity in a given sector are very different from other sectors. The type and amount of skills, investment and many other requirements of each industry, market or sector are different. Consequently, the set of entrepreneurial opportunities in a special sector (circles) is only perceivable and exploitable for a special group of people.

Assume circle A1 to be the mining sector/market. As can be seen, all the opportunities related to the mining sector are inside this circle. Therefore, the opportunities inside this circle (mining sector/market) are those opportunities whose perception and exploitation need abilities to perceive and exploit the mining opportunities. All the people who have these capabilities (access to information, experience, prior knowledge, education, and other factors which influence the perception of opportunities in the mining sector) have the potential (and only potential) ability to perceive opportunities inside this domain. This circle depicts an area which encompasses entrepreneurial opportunities for a group of people whose perception (and exploitation) abilities are centered on mining. It is clear that for the people who lack the necessary conditions for having the perception ability of entrepreneurial opportunities in the mining sector, it is almost impossible to see those opportunities. In other words, they are blind to the opportunities which are outside this area. The same is true about circle A2 for jewelry. Entrepreneurial opportunities inside circle A2 in Figure , are potentially available for all the people who have access to the information, knowledge, or experience in jewelry. All the factors which influence the perception and exploitation aspects of the entrepreneurial ability determines the perception/blindness or ability/inability to exploit a set of opportunities.

As depicted in Figure , it is clear that:

Each circle indicating an opportunities-for-some-people domain is a subset of the opportunities-for-all domain.

The area of the opportunities-for-all-people domain (rectangle) will be the total sum of the areas of opportunities-for-some-people domains (circles).

Let “S” be the number of opportunities-for-all domain (rectangle) then, the relationship between the number of opportunities-for-all domain (rectangle) and the number of opportunities-for-some-people domains (circles) is as follows:

4.3. Opportunities-for-a-particular-individual domain

Circles in Figure indicate the opportunities-for-some-people domains, and pentagons indicate opportunities-for-a-particular-individual domains. The qualities which distinguish the opportunities of this domain from opportunities-for-some-people domain, are the qualities that distinguishes a particular individual from all the individuals who can identify and exploit opportunities of an upper level (opportunity-for-some-people domain/level). This area is the exclusive domain for one person. No two individuals do share exactly the same information at the same time; neither have they the same opportunities-for-a-particular-individual domain. As was discussed in the previous section, a situation should be perceivable, exploitable and desirable for someone to be considered as a potential opportunity for him/her. Therefore, opportunity-for—some-people domain includes a set of opportunities (generally, in a specific area), which regarding the specific abilities to perceive them is only perceivable for a special group of people (for example, in mining sector) and other people who lack these type of abilities are blind to this type of opportunities. Therefore, the next level/domain, includes a set of opportunities for (only) a person regarding his/her unique set of abilities to perceive/exploit the entrepreneurial opportunities or desirability preferences. An opportunity should have three conditions to be included inside the opportunities-for-a-particular-individual domain of a particular entrepreneur. These conditions are:

The opportunity should be perceivable for him/her

The opportunity should be exploitable for him/her

The opportunity should be desirable for him/her

We will discuss each condition, respectively.

As is depicted in Figure , the third domain/level has three subtypes that is called perceivable-opportunities-for-a-particular-individual domain, exploitable-opportunities-for-a-particular-individual domain, and, desirable-opportunities-for-a-particular-individual domain.

4.3.1. Perceivable opportunities-for-a-particular-individual

Information about underutilized resources, new technologies, unstated demand, and political and regulatory shifts is distributed in the population according to the idiosyncratic life circumstances of each person (Venkataraman, Citation1997). Shane and Venkataraman (Citation2000) suggest that two broad categories of factors influence the probability that particular people will perceive particular opportunities: the possession of the prior information necessary to identify an opportunity and the cognitive properties necessary to evaluate it. In sum, people are able to identify some opportunities better than others if they can more easily recognize opportunities given the same amount of information. As was discussed earlier, life experiences (in forms of job functions and different experiences), searching processes and social networks influence access to information. Opportunity recognition (prior information in the form of knowledge about markets and knowledge of how to serve the markets and the prior knowledge of customer problems) influenced by absorptive capacity, intelligence, and cognitive properties also affects the perception of the entrepreneurial opportunities (Shane, Citation2003). Factors which affect access to information or how to interpret it as an opportunity determine the perceivable opportunities of a particular individual. The pentagons in Figures and depict the perceivable opportunities-for-a-particular-individual domain. It is important to note that a particular individual (for example, William in Figure ) might have more than one perceivable opportunities-for-a-particular-individual domain which could be inside different circles. For example, as can be seen in Figure , William has a set of abilities (abilities to perceive and exploit) in both jewelry and mining. Therefore, the total number of the perceivable opportunities for him is the union of pentagons in circles B1 and B2. In other words, if W is the total number of opportunities for William, then:

And

4.3.2. Exploitable opportunities-for-a-particular- individual

The diamonds in Figures and indicate the exploitable opportunities-for-a-particular-individual domains. The set of opportunities in this domain is a subset of the upper level of perceivable-opportunities-for-a-particular-individual. This means that before an opportunity is exploitable for someone, it should be perceivable for him/her. Furthermore, the number of opportunities which are exploitable for someone are less than the opportunities he/she can identify. In the case of William’s perceivable opportunities, the total number of exploitable opportunities for William is the number of exploitable opportunities for him in the mining sector (circleA1) plus the number of exploitable opportunities for him in the jewelry sector (circle A2).

Experiences like general business experiences, functional experiences, industry experiences, start-up experiences, and vicarious experiences influence the decision to exploit. These experiences act through the development of information and skills that facilitate resource acquisition, strategy formulation, and organizing process. Shane (Citation2003) divided the individual attributes that influence the decision to exploit into psychological factors and non-psychological factors. Furthermore, entrepreneurs compare the value of their utility from engaging in entrepreneurial activities with their opportunity cost of engaging in other activities. Even though a person may have relevant skills, such skills depend on the person’s thoughts, that is, different people with similar skills or the same person on different occasions, may perform differently. There are other factors which influence the exploitation of an entrepreneurial opportunity, for example, household income (e.g., Lim, Oh, & De Clercq, Citation2016; Shane, Citation2003), external knowledge sources (e.g., Foss, Lyngsie, & Zahra, Citation2013), cultural factors (e.g., Hamid et al., Citation2018) and so on. As a result, the unique set of exploitation part of entrepreneurial ability of a person forms the unique set of exploitable entrepreneurial opportunities for him.

4.3.3. Desirable opportunities-for-a-particular-individual

In addition to perceivability and exploitability, for an opportunity to be included in the opportunities-for-a-particular-individual domain, it must be desirable. Opportunities-for-a-particular-individual domain includes opportunities that are completely dependent on the desires and motivations of a person. Opportunities in this domain are restricted to a particular entrepreneur.

In past researches, judgments about the opportunity have been generally framed in terms of desirability and feasibility. These two dimensions are key factors in extant models of intention (Wood, Williams, & Grégoire, Citation2012). Desirability and feasibility have important roles in individual differences. Many theoretical explanations about choosing a possible opportunity to be pursued by someone can be classified into two simple conceptualizations: the amount of uncertainty perceived and the willingness to bear uncertainty (McMullen & Shepherd, Citation2006).

The concept of desirability corresponds to two concepts: attitude toward behavior and subjective norms (Krueger et al., Citation2000). So, the exploitation of opportunity should be attractive for a person himself/herself and then, for those people whose attitudes toward the exploitation of opportunity is important. In the literature, many factors like prior entrepreneurial exposure (Krueger, Citation1993), as well as education (Liñán, Citation2004) affect the perceived desirability of new venture.

In Figure , the stars inside the diamonds indicate the desirable opportunities for a particular individual domain. The set of opportunities in this domain is a subset of the upper level set of exploitable-opportunities-for-a-particular-individual. As in the case of William’s perceivable/exploitable opportunities, the total number of desirable opportunities for William is the number of desirable opportunities for him in the mining sector (star in circle A1) plus the number of desirable opportunities in the jewelry sector (star in circle A2).

A person (for example, William), has the set of entrepreneurial opportunities out of which he can choose an opportunity to pursue. The opportunities in circle A1 and A2 are potentially perceivable for all those who have the ability to perceive opportunities in mining or jewelry sectors. However, for William, regarding his unique set of abilities, this area is somewhat limited and his potential opportunities in mining and jewelry (circle A1 and A2) are restricted to opportunities inside pentagons B1 and B2 which are perceivable for him. Some of the opportunities, although perceivable, are not exploitable for him (inside the pentagons but outside the diamonds). Then, his potential opportunities are limited to the diamonds area. In the next step, he has to choose one of the opportunities inside the diamonds. As was discussed above, the desirability (or the degree of attractiveness of opportunity) determines which opportunity will be chosen. This attractiveness as was stated above, depends on the attitudes of the individual plus the attitudes of the reference people for him/her.

Two important points seem necessary here. First, the levels/domains in this framework indicate the potential types of opportunities for a typical entrepreneur. Renko et al. (Citation2012) distinguished between identifying an opportunity and perception of an opportunity. They believe that there are possible modes of relation between the actual and perceived opportunities. Considering the framework suggested by Renko et al. (Citation2012), it can be concluded that the total area of the diamonds (perceivable and exploitable opportunities) in Figure corresponds to the actual opportunities in the framework suggested by Renko et al. (Citation2012). As was stated earlier, our framework proposes a typical typology of potential opportunities for entrepreneurs and in the real world entrepreneurs might not follow this process exactly. Second, there should be an acceptable amount of match between opportunity and entrepreneur. Perception, exploitation, and desirability are like angles of a triangle which show the match between the opportunity and the entrepreneur. Lack of each angle leads to failure or imperfect exploitation.

5. Implications of the suggested framework

The framework suggested in the current paper has some implications for policy-makers, entrepreneurs, investors, and researchers.

The implications of the first domain/level of framework mostly concern the policy-makers. In opportunities-for-all domain, we explicitly assumed the existence of a definite number of entrepreneurial opportunities (stock/pool of entrepreneurial opportunities). Each entrepreneurial action creates more entrepreneurial opportunities, and as entrepreneurship takes place, the pool of entrepreneurial opportunities increases. When entrepreneurs act on an opportunity, they create additional entrepreneurial opportunities, so the more entrepreneurship there is in an economy, the more entrepreneurial opportunities will be available for others (Holcombe, Citation2003). An important point here is that all the entrepreneurial opportunities lie inside the opportunities-for-all domain. The quality and quantity of the opportunities here determine the abilities of the entrepreneurs who want to exploit these opportunities and their actions (on Schumpeterian opportunities or higher order opportunities), in turn lead to the creation of new opportunities. As was discussed above, regarding the higher risk involved in Schumpeterian opportunities, being more innovative, and the need for new information, there might be a lower desire in entrepreneurs to seek this type of opportunities. Schumpeterian opportunities are frequently pursued by larger ventures, with a strategic focus on future needs. In contrast, Kirznerian opportunities are pursued by less innovative small ventures, with a strategic focus on present needs (De Jong & Marsili, Citation2015). If the governments want to increase the quality and quantity of the entrepreneurial opportunities in an economy, they must follow policies to encourage entrepreneurs whose actions result in market disequilibrium and set the stage for the creation of a new series of opportunities.

Level 2 (opportunities-for-some-people) is a domain, of which some people with certain qualities are able to draw opportunities regardless of having desire to select a certain kind of opportunity, willingness, or motivation to discover and exploit opportunities or even to become entrepreneurs. For those who lack the necessary conditions to perceive and exploit entrepreneurial opportunities, it is almost impossible to see the opportunities in the opportunity-for-some-people domain. In other words, they are blind to the opportunities which are outside their opportunity-for-some-people-domain. For example, for those who possess the ability to perceive entrepreneurial opportunities in the mining sector, it is almost impossible to perceive opportunities in food industry. Regarding that, some opportunities need information, knowledge, and experience in more than one market/industry, general trainings and special educations for entrepreneurs can help them extend their ability to perceive opportunities and put them in a position where they can perceive more than one domain of opportunities. Improving the entrepreneurial abilities of the entrepreneurs and giving them enough motivation to perceive and exploit opportunities inside a particular sector increases the possibility of exploitation of those opportunities in that sector. For example, if the government is to support the mining sector, policies which enforce abilities to perceive and exploit opportunities in the mining sector might be a good option. On the other hand, as the possibility of finding a suitable case increases by searching inside the origin, for investors who want to find and invest in promising businesses (and entrepreneurs), considering the opportunities-for-some-people-domain will be a proper choice.

In level 3 (opportunities for a particular individual), the qualities which distinguish the opportunities of this domain from level 2 opportunities are the qualities that distinguishes a particular individual from all the individuals who can identify and exploit level 2 opportunities. Here is the exclusive domain for a person. The opportunities in this domain are divided into three subtypes. Each subtype indicates a feature that is needed by an opportunity to be counted as one of the potential opportunities for a particular person. The ideal state happens when the areas of perceivable, exploitable, and desirable opportunities for a person are equal (the areas of stars and diamonds, and pentagons are equal). This means that all the entrepreneurial opportunities which are perceivable for a particular individual, are exploitable and desirable for him/her. In this case, the entrepreneur has many choices among the entrepreneurial opportunities. Here again, the correct policy may be the improvement of the motivations of entrepreneurs and their exploitation ability.

The third level/domain part of the framework has an important implication for entrepreneurs and those who want to invest in ventures of entrepreneurs. For an entrepreneur who wants to find a promising opportunity, his/her perceivable-opportunities-for-a-particular individual domain(s) is the right place. To exploit an opportunity, one must first see it. The chance of seeing an opportunity in a domain in which opportunities are visible is higher than that of the one outside that area. Another important factor which determines the success or failure of a new entrepreneurial venture is the simultaneous existence of three angles of perceive, exploit and desire. The possibility of success of an entrepreneurial venture increases when the entrepreneur chooses an opportunity for which he/she has the necessary abilities to exploit and has the desire to pursue. Possibly, without each of the three angles of perceiving ability, exploiting ability or desire, the business (or the investment) will fail.

6. Conclusion

The current paper provided a review of research on the most important typologies of entrepreneurial opportunities. Addressing the role of individual-opportunity nexus in the classification of entrepreneurial opportunities, a new typology was suggested based on the role of individual and the attributes of the opportunity. To do so, we considered the revision of the definition of entrepreneurial opportunity and suggested that the word situation in the definition of entrepreneurial opportunity must include perceivability, exploitabitabilty and desirability to reflect the necessary features of an entrepreneur who acts on the opportunity.

Regarding the previous studies, including the typologies of entrepreneurial opportunities, the nature of the entrepreneurial opportunities, and the nexus of individual-opportunity, this paper suggested a framework which classified entrepreneurial opportunities into three types (three levels) based on the individual differences among people in their entrepreneurial abilities (to perceive and exploit entrepreneurial opportunities) and their differences in the desirability of seeking entrepreneurial opportunities.

Given the characteristics of the individuals, these opportunity types are considered as a set of opportunities whose attributes make them perceivable, exploitable, or desirable for a particular individual. These types/levels include 1- opportunities-for-all domain (level 1opportunities or opportunities-for-all-people), 2- opportunities-for-some-people domain (level 2 opportunities or all the opportunities for a group of people with particular capabilities), 3- opportunities-for-a-particular-individual domain (level 3 opportunities or opportunities for a particular individual that is desired, perceivable and exploitable for him/her). As was disused above, the opportunities in the third domain/level are divided into three subtypes.

The framework suggested here is considered to be an applicable typology of entrepreneurial opportunities. One of the implications of the suggested typology is directed toward policy-making. Before making efficient policies about individual entrepreneurs, determining the position of each entrepreneur against the opportunities and then directing them toward the domains and into the circles of opportunities that are suitable for them (feasible and desirable), causes them (and the economy) to use the resources more efficiently.

Our purpose in the current paper was to suggest a new typology of entrepreneurial opportunities based on the concepts of perceivability, exploitability, and desirability. As was stated earlier, our framework proposed a typology of potential opportunities for entrepreneurs. However, in the real world entrepreneurs may not exactly follow this process. More studies are needed to indicate the applications of the suggested framework in the real world conditions. In addition, as Shane (Citation2012) stated, few authors have pursued the categorization of strong and weak forms of opportunities, representing the Schumpeterian and Kirznerian types. We believe that the studies which proceed to these types of entrepreneurial opportunities will be useful. Furthermore, the factors that move the entrepreneurs from one domain to another and the intersection of two or more sets of entrepreneurial opportunities also need more research.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jahangir Yadollahi Farsi

Jahangir Yadollahi Farsi is an Associate Professor in Faculty of Entrepreneurship, University of Tehran, Iran. His main research interests are entrepreneurial opportunities, entrepreneurial universities, academic entrepreneurship and the discovery, evaluation and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities. He has PhD in systems management from university of Tehran, Iran.

Mahmood Moradi

Mahmood Moradi is a PhD candidate in Faculty of Entrepreneurship, University of Tehran, Iran. His main research interests are entrepreneurial cognition, corporate entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial universities and entrepreneurial opportunities. He received his MA in entrepreneurship from Faculty of Entrepreneurship, University of Tehran.

Mohammad Reza Zali

Mohammad Reza Zali is an Associate Professor in Faculty of Entrepreneurship, university of Tehran, Iran. He received his PhD in systems management from university of Tehran, Iran. His main research interests are corporate entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial leadership, and entrepreneurial universities.

References

- Aldrich, H. E., & Cliff, J. E. (2003). The pervasive effects of family on entrepreneurship: Toward a family embeddedness perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(5), 573–21. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00011-9

- Al-Shammari, M., & Al-Shammari, H. (2018a). Biculturalism and entrepreneurship: An introductory research note (A). International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 22(1), 1–11.

- Al-Shammari, M., & Al-Shammari, H. (2018b). The impact of bicultural knowledge, skills, abilities and other experiences (ksaos) on individual entrepreneurial behavior: The context of entrepreneurial discovery, evaluation and implementation. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 22(2), 1–18.

- Alvarado, J. F. (2018). Ideas, context and connections: Conceptual framing of the opportunity to innovate for migrant entrepreneurs. Sociologica, 12(2), 87–102. doi:10.6092/issn.1971-8853/8624

- Alvarez, S. A., & Barney, J. B. (2007). Discovery and creation: Alternative theories of entrepreneurial action. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 1(1‐2), 11–26. doi:10.1002/sej.4

- Baron, R. A. (1998). Cognitive mechanisms in entrepreneurship: Why and when entrepreneurs think differently than other people. Journal of Business Venturing, 13(4), 275–294. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(97)00031-1

- Baron, R. A. (2006). Opportunity recognition as pattern recognition: How entrepreneurs “connect the dots” to identify new business opportunities. Academy of Management Perspectives, 20(1), 104–119. doi:10.5465/amp.2006.19873412

- Baron, R. A., & Ensley, M. D. (2006). Opportunity recognition as the detection of meaningful patterns: Evidence from comparisons of novice and experienced entrepreneurs. Management Science, 52(9), 1331–1344. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1060.0538

- Baumol, W. J. (1990). Entrepreneurship: Productive, unproductive, and destructive. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5, Part 1), 893–921. doi:10.1086/261712

- Bolívar-Cruz, A., Batista-Canino, R. M., & Hormiga, E. (2014). Differences in the perception and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities by immigrants. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 1(1–2), 31–36. doi:10.1016/j.jbvi.2014.09.005

- Buenstorf, G. (2007). Creation and pursuit of entrepreneurial opportunities: An evolutionary economics perspective. Small Business Economics, 28(4), 323–337. doi:10.1007/s11187-006-9039-5

- Burke, A. E., Fitzroy, F. R., & Nolan, M. A. (2002). Self-employment wealth and job creation: The roles of gender, non-pecuniary motivation and entrepreneurial ability. Small Business Economics, 19(3), 255–270. doi:10.1023/A:1019698607772

- Busenitz, L. W., & Barney, J. B. (1997). Differences between entrepreneurs and managers in large organizations: Biases and heuristics in strategic decision-making. Journal of Business Venturing, 12(1), 9–30. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(96)00003-1

- Busenitz, L. W., Plummer, L. A., Klotz, A. C., Shahzad, A., & Rhoads, K. (2014). Entrepreneurship research (1985–2009) and the emergence of opportunities. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(5), 981–1000. doi:10.1111/etap.2014.38.issue-5

- Carsrud, A., & Brännback, M. (2011). Entrepreneurial motivations: What do we still need to know? Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 9–26. doi:10.1111/jsbm.2011.49.issue-1

- Casson, M. (1982). The entrepreneur: An economic theory. Totowa, NJ: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Companys, Y. E., & McMullen, J. S. (2007). Strategic entrepreneurs at work: The nature, discovery, and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities. Small Business Economics, 28(4), 301–322. doi:10.1007/s11187-006-9034-x

- Corbett, A. C. (2007). Learning asymmetries and the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(1), 97–118. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.10.001

- Davidsson, P. (2015). Entrepreneurial opportunities and the entrepreneurship nexus: A re-conceptualization. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(5), 674–695. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2015.01.002

- De Jong, D. J., & Marsili, O. (2011). Schumpeter versus Kirzner: Comparing two types of opportunity (summary). Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 31(15), 6.

- De Jong, J. P. J., & Marsili, O. (2015). The distribution of Schumpeterian and Kirznerian opportunities. Small Business Economics, 44(1), 19–35. doi:10.1007/s11187-014-9585-1