?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

As emotional consumer-brand relationships have a high impact on consumer behavior, brand managers tend to create passionate brands, e.g. by using emotional advertising messages. Although the role of emotions is frequently discussed in marketing literature, the causalities of brand passion are rudimentarily analyzed in empirical research. The aim of this study is investigating the antecedents (affective brand experience, brand prestige, brand identification and, brand trust) and consequences (positive word of mouth and willingness to pay price premium) passion to Smartphone brands among young consumers. The research model was tested using data convenient sampling collected from students of Azad University in Tehran City. The numbers of valid observations were 384. Structure equation modeling using Lisrel 8.80 software was used to verify and validate the research model. The results revealed that affective brand experience, brand identification, and brand trust (as important antecedents) has a positive and significant impact on brand passion. In addition, brand prestige has not a positive impact on brand passion. Finally, brand passion has a positive and significant impact on positive word of mouth and willingness to pay a higher price for the brand.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This study is an attempt to examine the antecedents and consequences of brand passion among young consumers of smartphones in Iran. Brand passion defined as a primarily affective, extremely positive attitude toward a specific brand that leads to emotional attachment and influences relevant behavioral factors. The proposed model is applied in between the young smartphone consumers in Iran and results show that brand trust and brand identification are the most important factors affecting brand passion, while positive word of mouth is the most important consequence of brand passion. The study also provides insights for companies active in the field of smartphones that they must pay intensive attention to improve their consumers’ passion to the brand through the creation of trust in consumers, consumers’ identification with the brand and affective experience using designing and innovation of products and services, in such a way as to meet the needs of the consumers.

1. Introduction

Brands help define consumers’ lives and play a vital role in people’s consumption behavior (Albert, Merunka, & Valette-Florence, Citation2013). For example, famous brands such as Apple, Zara, Nike, and Adidas played a vital role in people’s consumption behavior and had deep emotional bonds with them. For this reason, the consumer-brand relationship in the last decade has gained much attention from both practitioners and academics. Understanding the relationships between consumers and their brands has practical relevance to marketers due to the significant impact of this relationship on a company’s profitability (Rageh Ismail & Spinelli, Citation2012). Recent studies focused on understanding and explaining the variety of structures in relationships between consumer and brand. For example, relational constructs such as brand commitment (Fullerton, Citation2005; Hess & Story, Citation2005), brand trust (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, Citation2001; Hess & Story, Citation2005), and brand identification (Escalas & Bettman, Citation2003; Tuškej, Golob, & Podnar, Citation2013)that seem necessary to many branding studies. And affective constructs such as brand attachment (Thomson, MacInnis, & Park, Citation2005; Whan Park, MacInnis, Priester, Eisingerich, & Iacobucci, Citation2010), brand love (Albert & Merunka, Citation2013; Batra, Ahuvia, & Bagozzi, Citation2012; Carroll & Ahuvia, Citation2006; Sarkar, Citation2013) and, brand passion (Albert et al., Citation2013; Bauer, Heinrich, & Martin, Citation2007; Swimberghe, Astakhova, & Wooldridge, Citation2014)also influence consumer behavior.

The relationship between consumer and brand is important because previous studies have demonstrated that strong consumer-brand relationships enhance consumers’ brand loyalty(Hwang & Kandampully, Citation2012; Whan Park et al., Citation2010), positive word of mouth (Rageh Ismail & Spinelli, Citation2012), and consumers’ willingness to pay more (Thomson et al., Citation2005). Moreover, having strong consumer-brand relationships creates more sustainable brands, as envisioned through increased financial value of the company (Hwang & Kandampully, Citation2012; Park, MacInnis, & Priester, Citation2008). Therefore, the relationship between brand and consumer has become a significant topic in brand management. Nonetheless, it is still a challenging issue for many marketers how to deal with that task. Researchers emphasize the emotional aspects such as a brand passion to develop a strong relationship between consumers and brand (Albert et al., Citation2013; Bauer et al., Citation2007; Matzler, Pichler, & Hemetsberger, Citation2007). On the other hand, the increasing importance of passionate brands in marketing activities necessitates the analysis of the determinants and consequences of brand passion. Because create passion in consumers towards the brand can have a positive impact on consumer behavior such as willingness to pay more (Bauer et al., Citation2007; Swimberghe et al., Citation2014; Thomson et al., Citation2005) and spread positive word of mouth(Albert et al., Citation2013; Swimberghe et al., Citation2014).

Brand passion is a concept derived from the theory of Sternberg’s Triangular of Love (1986), where passion along with intimacy and commitment/decision constitutes the three domains of love. Among the three dimensions of love, passion is a more intense feeling for the object. It is so intense that it creates mental distress in case of any actual or anticipated separation from the brand(Sarkar, Citation2014).Also, Thomson et al. (Citation2005) show that passion leads to separation distress. Separation distress drives the person to maintain proximity to the brand. In a consumption context, Bauer et al. (Citation2007) brand passion defined as “a primarily affective, extremely positive attitude toward a specific brand that leads to emotional attachment and influences relevant behavioral factors.” However, only little empirical research has focused on the causalities of brand passion. Hence, the present study seeks to address this need by developing an antecedent and outcome model of brand passion on the basis of existing literature. The paper empirically examines the proposed brand passion model to test the hypothesized relationships. This study contributes to the existing body of literature by developing and testing a comprehensive brand passion model to determine the antecedents and consequences of brand passion; such an attempt has not been made before which emphasizes the originality value and significance of the present work. The rest of the paper is organized as follows: First, we provide a theoretical background of the brand passion concept. Second, the brand passion model explaining the relationship of brand passion with its antecedents and outcomes is presented. In the next section, the study reveals the research method adopted and describes the results obtained from the analysis. Finally, the study discusses the findings, implications, limitations and future research directions.

2. Theoretical background and literature review

2.1. Brand passion

Recently brand passion has been defined as “a psychological construct comprised of excitation, infatuation, and obsession for a brand” and “a feeling which few consumers embrace” (Albert et al., Citation2013, p. 2 and p. 5). In the marketing literature, the construct of passion has been mainly discussed within the framework of Sternberg’s triangular theory of love (Swimberghe et al., Citation2014). The triangular theory of love posits that love includes three components: intimacy, decision/commitment, and passion. Sternberg defines passion as “the drives that lead to romance, physical attraction, sexual consummation, and related phenomena in loving relationships” (Sternberg, Citation1997, p. 315). According to Sternberg (1997), the term passion circumscribes the sum of drives that lead to romantic feelings as well as physical attraction and desire. Furthermore, the strong wish and urge for union with the partner is one aspect of passion (Matzler et al., Citation2007).

In a consumption context, brand passion is “a primarily affective, extremely positive attitude toward a specific brand that leads to emotional attachment and influences relevant behavioral factors” (Bauer et al., Citation2007, p. 2190). This definition “describes the zeal and enthusiasm features of consumer–brand relationships” (Keh et al., Citation2007, p. 84) and “reflects intense and aroused positive feelings toward a brand” (Thomson et al., Citation2005, p. 80). A passionate consumer engages in an emotional relationship with the brand and misses the brand when unavailable (Matzler et al., Citation2007).

Fournier’s (Citation1998) concept of consumer-brand relationships contains passion as one relevant factor for determining the brand relationship quality. Accordingly, if a consumer is passionate about a brand, he/she will engage in a much more emotional relationship with the brand and even miss the brand or feel loss when the brand is unavailable (Matzler et al., Citation2007). According to interpersonal research on passion (Albert et al., Citation2013; Baumeister & Bratslavsky, Citation1999; Hatfield, Citation1988), we consider brand passion as the psychological construct and we define it as excitation, infatuation, and obsession for a brand (Albert et al., Citation2013; Hatfield, Citation1988).Though the growing literature on brand passion mainly concentrated on its conceptualization, the factors that drive brand passion and its outcomes have received relatively limited attention in the literature (Albert et al., Citation2013; Bauer et al., Citation2007; Sarkar, Ponnam, & Murthy, Citation2012; Swimberghe et al., Citation2014). A few studies examined factors driving brand passion such as Brand Self- Expression, Susceptibility to Influence, brand uniqueness, self-expressive brand, brand prestige, hedonic brand, consumers ‘extraversion, and so on (Albert et al., Citation2013; Bauer et al., Citation2007; Matzler et al., Citation2007; Sarkar et al., Citation2012; Swimberghe et al., Citation2014). The consequences of brand passion that have been examined in the literature are word of mouth, intention to purchase, willingness to pay a price premium and so on (Albert et al., Citation2013; Bauer et al., Citation2007; Matzler et al., Citation2007; Sarkar et al., Citation2012; Swimberghe et al., Citation2014). Hence, in this research, we review affective brand experience, brand prestige, brand identification, and brand trust as antecedents brand passion and word of mouth and willingness to pay more as consequences in between young consumers of famous Smartphone brands in Iran.

2.2. Antecedents of brand passion

2.2.1. Affective brand experience

Brakus, Schmitt, and Zarantonello (Citation2009) define brand experience as ‘subjective, internal consumer responses (sensations, feelings, and cognition) as well as behavioral responses evoked by brand-related stimuli that are part of a brand’s design and identity, packaging, communications, and environment.Brand experiences can be positive or negative, short-lived, or long-lasting (Brakus et al., Citation2009). Moreover, brand experience can positively affect consumer satisfaction and brand loyalty, as well as brand associations (in particular brand personality)(Zarantonello & Schmitt, Citation2010).

According to Lee, (Citation1977), love is an attitude. So, romantic brand love is also an attitude towards the brand. The proposed romantic brand love is emotion-laden, as it consists of emotion or intimacy and passion (Sarkar, Citation2011). Although there is no empirical evidence in the literature to explicate how each brand experience dimension leads to emotional brand attitude, it is plausible to argue that affective component of brand experience contributes to generating romantic brand love by inducing brand related arousal (Roy, Eshghi, & Sarkar, Citation2013).

Sarkar (Citation2013), in their research, found that affective brand experience has a positive effect on the two dimensions of romantic love (intimacy and passion for the brand). With respect to the above facts, the first hypothesis was formed.

Hypothesis 1: affective brand experience has a positive effect on brand passion.

2.2.2. Brand prestige

An important driver of brand passion is brand prestige, which is the status or esteem associated with a brand (Bauer et al., Citation2007). Ahearne et al., (Citation2005) and Ashforth and Mael, (Citation1989) stated that Individuals tend to maintain a positive social identity by affiliating with a prestigious company or brand as such affiliation provides social opportunities and social prestige (So, King, Hudson, & Meng, Citation2017). In the marketing literature, brand prestige is defined as the relatively high status of product positioning associated with a brand (Baek, Kim, & Yu, Citation2010; Erdoğmuş & Büdeyri-Turan, Citation2012). O’Cass and Frost, (Citation2002) and Baek et al. (Citation2010) asserted that Consumption of prestigious brands is a signal of social status, wealth or power since prestigious brands are infrequently purchased and are strongly linked to an individual’s self-concept and social image, creating value for the consumer through status and conspicuous consumption (Erdoğmuş & Büdeyri-Turan, Citation2012). On the other hand, the theory of self-esteem and social identity support the consideration that consumers tend to relate the prestige of a brand to their own identity in order to increase their self-esteem. Hence, according to Belk, (Citation2004), an extreme identification with a brand, caused by the prestige of this brand, can lead to enthusiastic and passionate feelings (Bauer et al., Citation2007).The idea of the research hypothesis was derived from Bauer et al. (Citation2007), who indicated that brand prestige has a positive effect on consumer passion.

Hypothesis 2: brand prestige has a positive effect on brand passion.

2.2.3. Brand identification

Consumers choose products and brands not only for their utilitarian values but also for their symbolic benefits. Brands possess deep meaning and serve to build consumers’ self-concept or identities (Albert & Merunka, Citation2013). Social identity is an interesting construct that can be used as an antecedent with a direct impact on brand passion. Bagozzi and Dholakia, (Citation2006) applied social identity in Brand Community, arguing that social identity must affect the brand identification because greater identification in the society leads to higher involvement with the brand, which in turn leads to merging brand identity with the identity of the person.Brand identification, defined as a consumer’s perceived state of oneness with a brand (Stokburger-Sauer, Ratneshwar, & Sen, Citation2012).Following the same idea, Sirgy et al., (Citation1997) considered the identification with the brand as the degree of congruence between consumer and brand image. The degree to which brands enable consumers to express their own identity is crucial to the level of identification with the brand(Rodrigues & Reis, Citation2013). Studies on brand identification thus identify two sources of congruency between the consumer and the brand: one that stems from the brand’s image, values or personality, referred to as “brand identification” (Escalas & Bettman, Citation2003; Fournier, Citation1998), and another that is external to the brand and is based instead on the typical consumer of the brand (Escalas & Bettman, Citation2003). Because this second source refers to the focal consumer’s identification with typical consumers of the brand, it is termed “customer identification”. Therefore, overall brand identification comprises both brand identification and customer identification (Albert & Merunka, Citation2013).Harrison-Walker, (Citation2001) asserted that when a consumer identifies with a brand, she or he develops positive feelings. Passion for a brand then should develop if the brand plays an important role in the consumers’ identity construction(Albert et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, recent studies have shown that a self-expressive brand encourages brand passion (Bauer et al., Citation2007) and brand identification positively affects brand love (Albert & Merunka, Citation2013) and brand passion (Albert et al., Citation2013). Hence we can say:

Hypothesis3: brand identification has a positive effect on brand passion.

2.2.4. Brand trust

A key construct in relational marketing (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994), brand trust offers an important component of successful marketing relationships (Albert & Merunka, Citation2013).The concept of brand trust shows that the relationship between a consumer and a brand could go beyond the satisfaction of functional performance (Belaid & Temessek Behi, Citation2011). Morgan and Hunt (Citation1994) definition of trust is widely accepted. According to them, trust is defined as “existing when one party has confidence in an exchange partner’s reliability and integrity”. Also, Morgan and Hunt (Citation1994) theorized that trust is one component of consumers’ relationships with brands, and trust, along with commitment, is a key characteristic required for relationship marketing success.

The conceptualization of brand trust in Belaid and Temessek Behi (Citation2011) study highlights the fact that it has both a cognitive and an affective nature. The cognitive componentof trust refers to credibility, which is related to the perceived reliability of the information on the brand, the performance of the brand, and its aptitude to satisfy consumer needs (Belaid & Temessek Behi, Citation2011; Delgado-Ballester & Luis Munuera-Alemán, Citation2001). The affective component of trust is integrity. The brand is considered honorable when it respects its promises and puts the consumer’s long-term interests foremost. In summary, brand credibility results from a rational and cognitive process based on the assessment of brand performance and reputation, whereas integrity is an affective and social trust outcome built on consumer perception of brand orientation and intentions towards the consumer(Tong, Su, & Xu, Citation2017).

In the interpersonal context, trust is closely related to affection. Since brand trust has a positive impact on affective constructs such as brand affect (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, Citation2001), brand love (Albert & Merunka, Citation2013), and brand passion (Albert et al., Citation2013).Hence:

Hypothesis 4: brand trust has a positive effect on brand passion.

2.3. Consequences of brand passion

2.3.1. Positive word of mouth

Harrison-Walker (2001) defined WOM as “informal, person-to-person communication between a perceived non-commercial communicator and a receiver regarding a brand, a product, an organization or a service”. The rationale of WOM is that information on products, services, and others can spread from one consumer to another either in person or through communication media(Lien & Cao, Citation2014). While WOM can be positive or negative, marketers are naturally interested in promoting PWOM, such as recommendations to others, and our research focuses on PWOM because the PWOM helps to promote products or services without incurring additional promotion or advertisement costs(Brown, Broderick, & Lee, Citation2007; Lien & Cao, Citation2014; Ghorbanzadeh and Saeednia, Citation2018; Abedi et al., Citation2019).Reviewing the previous studies indicates that brand passion positively influences positive word of mouth (Albert et al., Citation2013; Bauer et al., Citation2007; Sarkar et al., Citation2012). For example, Albert et al. (Citation2013) find that brand passion has a significant and direct positive influence on spreading positive Word-of-Mouth about the passionate brand.Furthermore, consumers appear more likely to engage in positive word-of-mouth behavior when they experience notable emotional relationships(Bauer et al., Citation2007; Matzler et al., Citation2007).As a result of these considerations, the following assumption can be made:

Hypothesis 5: positive word of mouthhas a positive effect on brand passion.

2.3.2. Willingness to pay a price premium

A brand obtains a price premium when the sum that customers are willing to pay for products from the brand is higher than the sum they are willing to pay for similar products from other relevant brands (Aaker, Citation1996). Thomson et al. (Citation2005) suggested that if an individual is emotionally attached to a brand, then he/she will be willing to pay a premium price for purchasing the brand. Emotional attachment with a brand is positively associated with maintaining proximity to the brand and mental distress created due to actual or anticipated separation from the brand (Sarkar, Citation2011). Therefore, a consumer should accept a price increase, because there are no other alternatives, and he or she wants to continue to benefit from the positive emotions linked to the passionate brand (Albert & Merunka, Citation2013). Previous research has shown that brand passion has a direct and indirect effect on Willingness to pay a price premium (Albert et al., Citation2013; Bauer et al., Citation2007). Thus:

Hypothesis 6: Willingness to pay a price premium has a positive effect on brand passion.

3. Conceptual model

Based on the hypotheses presented in theTheoretical background of the study, the conceptual model is developed in Figure . The factors of affective brand experience, brand prestige, brand identification, brand trust, brand passion, positive word of mouth, and Willingness to pay a price premium are used to test in this model.

4. Research methodology

4.1. Participants

The data was derived from a sample of Islamic Azad University Graduate students in Tehran. Reasons Tehran students’ selection as the sample:

The relative homogeneity of students in terms of their age, intelligence and income(Esmaeilpour, Citation2015).

The Islamic Azad University has the most share of student than other universities in Iran.

Tehran is the largest commercial city and financial center in Iran, thus many people use Smartphone.

The infrastructure of mobile connection in Tehran is much better than in other cities in Iran.

In this research, Cochran formula is used to determine sample size. Cochran formula for unlimited society:

For the unlimited population, the sample size required was estimated to be 384. Also, convenience sampling method was used to attract respondents. In terms of gender, the distribution of the sample was 58.3% for male and 41.6% for female. According to the Government’s latest census report, by end of 2016, the Iran population’s male and female ratio is 50.66% and 49.34%; thus the sample appears to be representative in terms of gender. Having analyzed the demographic characteristics of students (Table ), most of them were figured out to be in the age between 22 and 25(41.92%), followed by those in the range between 18 and 21 (32.04%), and lastly those in the age between 26 and 31(26.04%); when compared with the Iran population, the spread of age group sampled is comparable with the population profile.

Table 1. Demographic profile of respondents

4.2. Measurement

A research questionnaire was developed in two sections. The first section includes the 6 constructs, affective brand experience, brand prestige, brand identification, brand trust, brand passion, positive word of mouth, and Willingness to pay a price premium in this study. The second section contains respondents’ demographics (gender, age, education, and brand’s name Smartphone). The developed questionnaire was pre-tested on 40 students and the result showed the instructions and questions were well understood.

A 26-item scale measuring was adopted from previous studies. All English items were translated into Persian, and then back-translated by a second bilingual person to ensure meaning consistency. Respondents rated all measures on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Completely Disagree) to 5 (Completely Agree). The reason for choosing the 5-point Likert scale is because of most studies conducted on research variables used 5-scale Likert format (Albert et al., Citation2013; Bauer et al., Citation2007), hence, the instrument of the present study was also designed in 5-scale Likert format.

For affective brand experience, two items were adapted from Sarkar et al. (Citation2012). Brand prestige was measured with three items based on Stokburger-Sauer et al. (Citation2012). Brand identification was measured with five items based on So et al., (Citation2013). brand trust was measured using five items based on Delgado-Ballester and Luis Munuera-Alemán (Citation2001). While brand passion was operationalized using the four items proposed by Sarkar et al. (Citation2012). Lastly, the researchers adapted four and three items respectively for positive word of mouth and Willingness to pay a price premium from Carroll and Ahuvia (Citation2006) and Anselmsson et al., (Citation2014).

5. Data analyses

5.1. Measurement model evaluation

The research model was tested using Lisrel 8.80, a structural modeling technique which is well suited for predictive models (Bentler & Chou, Citation1987). Before testing the hypothesized relationships, we analyzed the reliability and validity of the scales. Convergent validity, which was examined by using the composite reliability (CR) and the average variance extracted (AVE), demonstrates how the items are related to each other; and, simply, whether they can be in the same measurement or not. The lower acceptable value is 0.70 for CR and 0.50 for AVE (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981).

As presented in Table , CR of each variable is more than 0.7 and AVE of each variable is more than 0.5 which means the convergent validity is achieved. The recommended level for the factor loadings is 0.5 and all the factor loadings of this study are greater than 0.5 expect second’s item from brand identification (See Table ).

Table 2. Factor loadings, CR and AVE values

Additionally, discriminant validity was analyzed in order to examine whether a measurement is not a reflection of any other measurement or not. In this analysis, each of the square roots of AVE should be higher than the other correlation coefficients for adequate discriminant(Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981).As presented in Table , the square root of AVE for each variable is greater than the other correlation coefficients which indicate the discriminant validity is achieved.

Table 3. Discriminant validity

5.2. Structural model evaluation

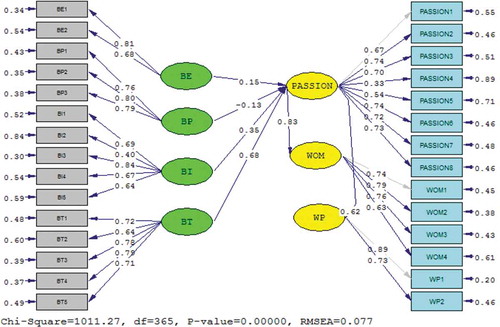

The results of tested structural model are presented in Figure and Table . Five hypothesized relationships between variables were found statistically significant while one hypothesis was not significant. More specifically, affective brand experience, brand identification and brand trust appeared to have a significant, positive impact on brand passion; (respectively) H1 (β = 0.15, p < 0.001), H3 (β = 0.35, p < 0.01), H4 (β = 0.68, p < 0.001). Furthermore, brand prestige was not found to have a positive influence on brand passion; H2 was rejected (β = −0.13). Further, brand passion have a significant, positive impact on positive word of mouth, H5 was supported (β = 0.83, p < 0.01). Finally, H7, which predicts the positive influence of brand passion on Willingness to pay a price premium, was supported (β = 0.62, p < 0.01).

Table 4. Hypothesis testing

Additionally, the goodness-of-fit indices indicates the model did fit the data very well; = 2.77; p < 0.001; NFI = 0.93; IFI = 0.96; NNFI = 0/95; CFI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.77 (See Table ).

Table 5. Goodness-of-fit indices

6. Discussionand conclusion

The relationship between the brand and the consumer is one of the most important factors that play a vital role in the profitability of the companies and the competitive advantage. This has attracted a great deal of attention from marketing researchers (Valta, Citation2013). Thepresent study examinedtheserelationshipsinterms of the variable ofbrand passion andfollowingthe discovery ofantecedents and itsconsequencesonsmartphones.

The first hypothesis suggested that affective consumer experience of brand affects bran passion. According to the results in Table , it is evident that the path coefficient of the affective experience on brand passion has a path coefficient of 0.15 and t-statistic calculated to be 2.25, which is greater than 1.96. Hence, the null hypothesis is rejected, i.e. affective brand experience has a positive effect on brand passion with 95% confidence. The result of this hypothesis is in accordance with the study of Sarkar (Citation2013).

The second hypothesis states that brand prestige has a positive effect on brand passion. According to the results in Table , it is evident that the path coefficient of brand prestige on passion has a path coefficient of −0.13 and a t-statistic of −1.76, which is lower than 1.96. Although the effect of brand prestige on brand passion is relatively significant, the t-statistic is not sufficient. Hence, the null hypothesis is proven, i.e. brand prestige has not an effect on passion at 95% confidence. It is expected that brand prestige and passion are indirectly linked with each other.The result of this hypothesis is contrary to the study of Bauer et al. (Citation2007).

The third hypothesis suggested that consumer brand identification affects brand passion. According to the results in Table , it is evident that the path coefficient of the brand identification on brand passion has a path coefficient of 0.35 and t-statistic calculated to be 5.32, which is greater than 1.96. Hence, the null hypothesis is rejected, i.e. brand identification has a positive effect on brand passion with 95% confidence. The result of this hypothesis is in line with the results of the study by Albert et al. (Citation2013).

The fourth hypothesis suggested that consumer brand trust affects brand passion. According to the results in Table , it is evident that the path coefficient of trust on brand passion has a path coefficient of 0.68 and t-statistic calculated to be 7.58, which is greater than 1.96. Hence, the null hypothesis is rejected, i.e. brand trust has a positive effect on brand passion with 95% confidence.The result of this hypothesis is supported by previous research (Albert & Merunka, Citation2013; Albert et al., Citation2013).

The fifth hypothesis suggested that consumers’ passion for brand affects positive word of mouth. According to the results in Table , it is evident that the path coefficient of passion on word of mouth has a path coefficient of 0.83 and t-statistic calculated to be 10.02, which is greater than 1.96. Hence, the null hypothesis is rejected, i.e. brand passion has a positive effect on positive word of mouth with 95% confidence. The result of this hypothesis is supported by previous research (Albert et al., Citation2013; Bauer et al., Citation2007; Sarkar et al., Citation2012).

The sixth hypothesis suggested that consumer brand passion affects willingness to pay more. According to the results in Table , it is evident that the path coefficient of willingness to pay more has a path coefficient of 0.62 and t-statistic calculated to be 8.85, which is greater than 1.96. Hence, the null hypothesis is rejected, i.e. brand trust has a positive effect on willingness to pay more with 95% confidence.The result of this hypothesis is in accordance with the study of Albert et al. (Citation2013) and Bauer et al. (Citation2007).

7. Theoretical implications

From a theoretical perspective, the current study to develop a conceptual model that examines the antecedents and consequences of brand passion within the smartphone sector. To our knowledge, this research is the first to develop the concept of brand passion in the context of the smartphone. Indeed, the good qualities of relationships and brand passion can be considered as a “form of insurance” in order to maintain a relationship with smartphone brands.

8. Managerial implications

In this study, the passion of consumers to a brand was explored as part of a deep emotional bond (brand love) which is built between consumers and brand in the long term. This study focused on some of the factors affecting consumers’ passion for brand and the consequences through structural equation modeling. According to the results, the following suggestions are made to expand this area of research.

Given the result of the first hypothesis about the effect of consumer emotional experience on brand passion, producers can establish positive experiences where consumers are in contact with the products. For example, a good treatment when a product is purchased at the store, high quality while using the product, reasonable price, service that consumers expect after buying the brand and ultimately establishing long-term relationships management systems for customer retention can have positive effect on consumer mindset and establish an emotional relationship with the company’s brand.

According to the third hypothesis, it can be argued that values and characters to a brand can offer the consumer benefits that affect the sense of brand identification. This identification can be achieved in several ways (e.g., packaging, brand name, and retail outlets), which in turn can provide ideal conditions for the consumer passion for the brand.

Since trust has positive and significant effect on the brand passion, it is crucial to enhance brand trust among consumers. Brand trust is derived from the popularity of brand and customer perceptions of product quality. Brand trust is the most important characteristic of a brand. Any investment on brands should concentrate on ads or supporting the social and cultural activities. Furthermore, a foundation for brand trust is the companies encouraged to be honest in their claims about a product. In addition, it is crucial to take measures for the product quality such as after-sales service, training and reassuring the customer about the product, which can lead to trust and eventually a passion for the brand.

According to the results of the fifth and sixth hypotheses, which show the effect of consumers’ passion on word of mouth and willingness to pay more, the following suggestions are made: Consumers’ brand passion is associated with warm and pleasant feelings about the brand, emotions and branding excellence is in the consumer’s mind. It is also stated that relate a brand to their personality when purchasing it. Therefore, the branded product should be advertised to desirably distinguish special customers from the normal customers of other bands. For example, buyers of Apple are usually people who are emotionally great and are financially more confident than the middle class. Companies can influence the society of their consumers through appropriate publicity and brand association. It is also recommended that producers identify factors contributing to the formation of such relationships. For example, product design, attractive packaging, good quality of product and ingredients can be improved. As in the case of some famous brands such as Samsung Mobile Phones, offering low prices at market introduction can provide a trigger to establish long-term emotional attachment to new products, thus leading to greater consumer enthusiasm towards the brand.

9. Limitations and suggestions for future research

Like other research, this study was not an exception to limitations. The first limitation of this study was the multitude factors contributing to brand (i.e. precedents and consequences). In other words, different variables were raised as contributing factors and the results of brand passion. This study only explored a few factors, since it was outside the scope to cover the rest of factors.

Another limitation of this study was its population because it was conducted only on students. Hence, it is essential to generalize the results to other consumer groups in the society more carefully.

Adding variables such as brand self-expression, brand uniqueness and consumer personality traits (e.g. extroversion and introversion) as antecedents and purchase intention and brand loyalty as consequences of brand passion to the research model and testing them in a broader population and on the other brands for which consumers have passion.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Davood Ghorbanzadeh

Davood Ghorbanzadeh is a Ph.D. Candidates Of Business Management-Marketing Management and graduated of MSc in Business Management-Marketing from the Facultyof Management and Social science, Islamic Azad University Of Tehran North Branch, Iran. Her research interests include consumer behavior, tourism marketing, social media, and Branding. He is an author or co-author of some research papers which have been accepted and presented at conferences or published in national and international journals.

Hamidreza Saeednia

Hamidreza Saeednia is an Associate Professorin Marketing from the Department of Management, Islamic Azad University of North Tehran. His research interests include brand management, consumer behavior and social media marketing. He is an author or co-author of more 30 papers, which have been presented at conferences or published in national and international journals.

Atena Rahehagh

Atena Rahehagh is a Ph.D. Candidates Of Business Management-Marketing Management and graduated of MSc in Business Management-Marketing from the department of Management and Social science, Islamic Azad University Of Tehran North Branch, Iran. Her research interests include corporate social Responsibility, Cause related Marketing and Branding.

References

- Aaker, D. A. (1996). Measuring brand equity across products and markets. California Management Review, 38(3), 102. doi:10.2307/41165845

- Abedi, E., Ghorbanzadeh, D., & Rahehagh, A. (2019). Influence of eWOM information on consumers' behavioral intentions in mobile social networks. Journal of Advances in Management Research. doi:10.1108/JAMR-04-2019-0058

- Ahearne, M., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Gruen, T. (2005). Antecedents and consequences of customer-company identification: Expanding the role of relationship marketing. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(3), 574–585.

- Albert, N., & Merunka, D. (2013). The role of brand love in consumer-brand relationships. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 30(3), 258–17. doi:10.1108/07363761311328928

- Albert, N., Merunka, D., & Valette-Florence, P. (2013). Brand passion: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Business Research, 66(7), 904–909. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.12.009

- Anselmsson, J., Vestman Bobdesson, N., & Johansson, U. (2014). Brand image and customers' willingness to pay a price premium for food brands. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 23(2), 90–102.

- Ashforth, B. E., & Meal, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39.

- Baek, T. H., Kim, J., & Yu, J. H. (2010). The differential roles of brand credibility and brand prestige in consumer brand choice. Psychology & Marketing, 27(7), 662–678. doi:10.1002/mar.v27:7

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Dholakia, U. M. (2006). Antecedents and purchase consequences of customer participation in small group brand communities. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 23(1), 45–61.

- Batra, R., Ahuvia, A., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2012). Brand love. Journal of Marketing, 76(2), 1–16. doi:10.1509/jm.09.0339

- Bauer, H. H., Heinrich, D., & Martin, I. 2007. How to create high emotional consumer-brand relationships? The causalities of brand passion. Paper presented at the 2007 Australian & New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference Proceedings, University of Otago, 2189–2198. doi:10.1094/PDIS-91-4-0467B

- Baumeister, R. F., & Bratslavsky, E. (1999). Passion, intimacy, and time: Passionate love as a function of change in intimacy. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(1), 49–67. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0301_3

- Belaid, S., & Temessek Behi, A. (2011). The role of attachment in building consumer-brand relationships: An empirical investigation in the utilitarian consumption context. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 20(1), 37–47. doi:10.1108/10610421111108003

- Belk, R. W. (2004). Men and thier machines. ACR North American Advances, 31(1), 273-278.

- Bentler, P. M., & Chou, C.-P. (1987). Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological Methods & Research, 16(1), 78–117. doi:10.1177/0049124187016001004

- Brakus, J. J., Schmitt, B. H., & Zarantonello, L. (2009). Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 73(3), 52–68. doi:10.1509/jmkg.73.3.052

- Brown, J., Broderick, A. J., & Lee, N. (2007). Word of mouth communication within online communities: Conceptualizing the online social network. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 21(3), 2–20. doi:10.1002/dir.20082

- Carroll, B. A., & Ahuvia, A. C. (2006). Some antecedents and outcomes of brand love. Marketing Letters, 17(2), 79–89. doi:10.1007/s11002-006-4219-2

- Chaudhuri, A., & Holbrook, M. B. (2001). The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing, 65(2), 81–93. doi:10.1509/jmkg.65.2.81.18255

- Delgado-Ballester, E., & Luis Munuera-Alemán, J. (2001). Brand trust in the context of consumer loyalty. European Journal of Marketing, 35(11/12), 1238–1258. doi:10.1108/EUM0000000006475

- Erdoğmuş, İ., & Büdeyri-Turan, I. (2012). The role of personality congruence, perceived quality and prestige on ready-to-wear brand loyalty. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: an International Journal, 16(4), 399–417. doi:10.1108/13612021211265818

- Escalas, J. E., & Bettman, J. R. (2003). You are what they eat: The influence of reference groups on consumers’ connections to brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13(3), 339–348. doi:10.1207/S15327663JCP1303_14

- Esmaeilpour, F. (2015). The role of functional and symbolic brand associations on brand loyalty: A study on luxury brands. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 19(4), 467–484. doi:10.1108/JFMM-02-2015-0011

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50. doi:10.1177/002224378101800104

- Fournier, S. (1998). Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(4), 343–373. doi:10.1086/jcr.1998.24.issue-4

- Fullerton, G. (2005). How commitment both enables and undermines marketing relationships. European Journal of Marketing, 39(11/12), 1372–1388. doi:10.1108/03090560510623307

- Ghorbanzadeh, D., & Saeednia, H. R. (2018). Examining telegram users' motivations, technical characteristics, trust, attitudes, and positive word of mouth: Evidence from iran. Intenational Journal of Electronic Marketing and Relaiting, 9(4), 344–365.

- Harrison- Walker, L. J. (2001). The measurement of word of mouth communication and an investigation of service quality and customer commitment as potential antecedents. Journal of Service Research, 4(1), 60–75.

- Hatfield, E. 1988. Passionate and companionate love. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(88)79586-7

- Hess, J., & Story, J. (2005). Trust-based commitment: Multidimensional consumer-brand relationships. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 22(6), 313–322. doi:10.1108/07363760510623902

- Hwang, J., & Kandampully, J. (2012). The role of emotional aspects in younger consumer-brand relationships. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 21(2), 98–108. doi:10.1108/10610421211215517

- Keh, H. T., Pang, J., & Peng, S. (2007, June). Understanding and measuring brand love. In Society for Consumer Psychology Conference Proceedings, Santa Monica (pp. 84–88).

- Lee, J. A. (1977). A typology of styles of loving. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 3(2), 173–182.

- Lien, C. H., & Cao, Y. (2014). Examining WeChat users’ motivations, trust, attitudes, and positive word-of-mouth: Evidence from China. Computers in Human Behavior, 41, 104–111. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.08.013

- Matzler, K., Pichler, E. A., & Hemetsberger, A. (2007). Who is spreading the word? The positive influence of extraversion on consumer passion and brand evangelism. Marketing Theory and Applications, 18, 25–32.

- Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. The Journal of Marketing, 20–38. doi:10.1177/002224299405800302

- O'cass, A., & Frost, H. (2002). Status brand: Examining the effects of non-product-related brand association on status and conspicuous consumption. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 11(2),67–88.

- Park, C. W., MacInnis, D. J., & Priester, J. (2008). Brand attachment: Constructs, consequences, and causes. Foundations and Trends® in Marketing, 1(3), 191–230. doi:10.1561/1700000006

- Rageh Ismail, A., & Spinelli, G. (2012). Effects of brand love, personality and image on word of mouth: The case of fashion brands among young consumers. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: an International Journal, 16(4), 386–398. doi:10.1108/13612021211265791

- Rodrigues, P., & Reis, R. 2013. The Influence of “Brand Love” In Consumer Behavior–The Case of Zara and Modalfa brands. Paper presented at the 22nd International Business Research Conference, Madrid, 1–9.

- Roy, S. K., Eshghi, A., & Sarkar, A. (2013). Antecedents and consequences of brand love. Journal of Brand Management, 20(4), 325–332. doi:10.1057/bm.2012.24

- Sarkar, A. (2011). Romancing with a brand: A conceptual analysis of romantic consumer-brand relationship. Management & Marketing, 6(1), 79.

- Sarkar, A. (2013). Romantic brand love: A conceptual analysis. The Marketing Review, 13(1), 23–37. doi:10.1362/146934713X13590250137709

- Sarkar, A. (2014). Brand love in emerging market: A qualitative investigation. Qualitative Market Research: an International Journal, 17(4), 481–494. doi:10.1108/QMR-03-2013-0015

- Sarkar, A., Ponnam, A., & Murthy, B. K. (2012). Understanding and measuring romantic brand love. Journal of Customer Behaviour, 11(4), 324–347. doi:10.1362/147539212X13546197909985

- Sirgy, M. J., Grewal, D., Mangleburg, T. F., Park, J. O., Chon, K. S., & Claiborne, C. B., ... & Berkman, H. (1997). Assessing the predictive validity of two methods of measuring self-image congruence. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 25(3), 229–241.

- So, K. K. F., King, C., Hudson, S., & Meng, F. (2017). The missing link in building customer brand identification: The role of brand attractiveness. Tourism Management, 59, 640–651. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2016.09.013

- So, K. K. F., King, C., Sparks, B. A., & Wang, Y. (2013). The influence of customer brand identification on hotel brand evaluation and loyalty development. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 34(1), 31–41.

- Sternberg, R. J. (1997). Construct validation of a traingular love scale. European Journal of Social Psychology, 27(3), 313–335.

- Stokburger-Sauer, N., Ratneshwar, S., & Sen, S. (2012). Drivers of consumer–Brand identification. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 29(4), 406–418. doi:10.1016/j.ijresmar.2012.06.001

- Swimberghe, K. R., Astakhova, M., & Wooldridge, B. R. (2014). A new dualistic approach to brand passion: Harmonious and obsessive. Journal of Business Research, 67(12), 2657–2665. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.04.003

- Thomson, M., MacInnis, D. J., & Park, C. W. (2005). The ties that bind: Measuring the strength of consumers’ emotional attachments to brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 15(1), 77–91. doi:10.1207/s15327663jcp1501_10

- Tong, X., Su, J., & Xu, Y. (2017). Brand personality and its impact on brand trust and brand commitment: An empirical study of luxury fashion brands. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 11(2), 196–209..

- Tuškej, U., Golob, U., & Podnar, K. (2013). The role of consumer–Brand identification in building brand relationships. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 53–59. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.022

- Valta, K. S. (2013). Do relational norms matter in consumer-brand relationships?. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 98–104.

- Whan Park, C., MacInnis, D. J., Priester, J., Eisingerich, A. B., & Iacobucci, D. (2010). Brand attachment and brand attitude strength: Conceptual and empirical differentiation of two critical brand equity drivers. Journal of Marketing, 74(6), 1–17. doi:10.1509/jmkg.74.6.1

- Zarantonello, L., & Schmitt, B. H. (2010). Using the brand experience scale to profile consumers and predict consumer behaviour. Journal of Brand Management, 17(7), 532–540. doi:10.1057/bm.2010.4