Abstract

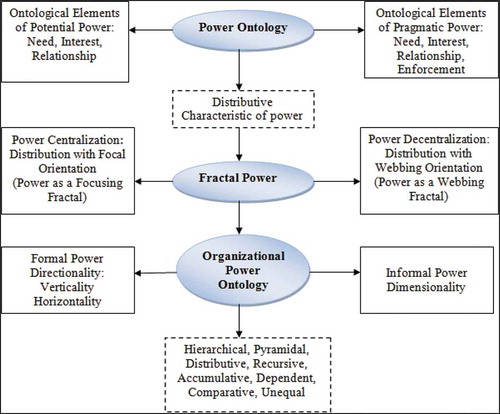

Fractal metaphor could be introduced to organization studies to elaborate on those organizational concepts that call for self-organization, self-similarity, similarity persistence in different organizational levels, symmetrical expansion, homogeneous discipline and quality, omnipresent controlling measures, and growth, as well as the organizational processes and procedures that require recursion. Organizational power is an abstract entity which could precisely be explained via a metaphorical fractal. Thus, Sierpinski Triangle, a familiar geometrical fractal has been applied in the paper with the purpose to unfold the fractal characteristics of the power within organizations. Such an approach presumes power characteristics as hierarchical, pyramidal, distributive, recursive, accumulative, dependent, comparative, and unequal. The discussions through the paper could contribute to future organization theorists to form an idea on two ubiquitous concepts of organizational power: directionality and dimensionality. Moreover, the paper theorizes the triangular combination of need, interest, and relationship as ontological elements of potential power and a fourth entity (enforcement) in combination with the three previous elements as the necessary elements of every pragmatic power.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Power is a ubiquitous social phenomenon but daily rush and obsessions do not let us be aware of this organizational concept. Reading this paper could partly explain the formation and distribution of power within organizations. The necessity for knowing the characteristics of organizational power for the public is its presence in all public organizations, which run their daily affairs.

1. Introduction

Never is human being surrounded by plethora of organizations in his social existence as our current epoch. An impartial beholder of the organizational power in our world could not neglect or justify the current organizational hegemony of our age. Human, now everywhere, is the subject of at least one or multiple powerful organizations. These organizational powers could manifest themselves through bureaucracies, governmental manipulations and surveillance of the lives of the citizens or the organizational dictatorships in some organizations. Thus, human consciously or unconsciously lives under the organizational hegemony with a superdominance unprecedented in human history. Power is the core entity for such historic dominance. Either it could be manipulated for the exploitation, influence, dependence, disempowerment, suppression, and in a word subjugation of the human factor in organizations or vice versa for nudging him toward public benediction. Therefore, we need to carry out a minutely and detailed study of power in the context of organizations with new approaches and concepts such as new organizational metaphors. However, power ontology as a simultaneously abstract concept with plethora of concrete manifestations has been the philosophical project of the great minds in the history of philosophy. The ontological contemplations of Hegel, Marx, Hobbes, Nietzsche, and numerous other philosophers on power as an existing undeniable phenomenon within the realm of human existence have illuminated the dark corners of thought and enlightened the subsequent philosophers to ponder deep down on the originating roots of economic, social, political, cultural, and organizational powers, among its other infinite emergences. Power is a core concept in political philosophy, which led to the evolution of the concepts of law, state, hegemony, legitimacy and illegitimacy, etc. Hobbes’ Leviathan, Marx’s power and the social classes, Hegel’s systemic history as a power, as a few examples, all dissected power’s gigantic body once it is fully grown; since the more grown is the power, the better is recognizable. Hence, the paper was written to shed light on the micro-building blocks of organizational power and their accumulation in forming a structure of power within organizations via the metaphorical application of the fractal philosophy. Thus, Whetten’s (Citation1989) fundamental questions have shaped the core elements of the paper for its theoretical development. According to Whetten (Citation1989, pp. 494–495) in a conceptual paper, the same as current philosophical project, we should be able to provide satisfactory responses to seven questions: “(a) What’s new? (b) So what? (c) Why so? (d) Well done? (e) Done well? (f) Why now? and (g) Who cares?”. The answers to the Whetten’s questions, presented in the following, clarify the principal justifications behind the conceptualization process through the paper:

What is new? Discussing the origin and formation of power as a fractal concept.

So what? It contributes to the understanding of the organizational power as a simultaneously accumulative and distributive entity, which should be studied and reformed from the base of the power pyramid not from the peak.

Why so? Since each hierarchy of power begets from the power hierarchy below.

Well done? To elaborate the organizational power genesis, formation, and metamorphosis a metaphorical approach has used.

Done well? To prevent any ambiguities, the paper has tried to show the emergence of the fractal organizational power by sufficient figures and their relevant illustrations.

Why now? There is a need to carefully scrutinize organizational power in the third millennium; since it is the era of organizational ubiquity, hegemony, and major dependency.

Who cares? The organizational and power researchers and the public who are under this hegemony.

2. Literature

2.1. The fractal metaphor

Metaphor has extensively used in organization studies (e.g. see Armenakis & Bedeian, Citation1992; Boxenbaum & Rouleau, Citation2011; Cafferata, Citation1982; Carr & Leivesley, Citation1995; Cassell & Lee, Citation2012; Cleary & Packard, Citation1992; Cornelissen, Citation2006; Cornelissen, Kafouros, & Lock, Citation2005; Daft & Weick, Citation1984; Faghih, Bavandpour, & Forouharfar, Citation2016; Inns, Citation2002; Kendall & Kendall, Citation1993; McCourt, Citation1997; Meyer, Citation1984; Örtenblad, Putnam, & Trehan, Citation2016; Palmer & Lundberg, Citation1995; Putnam, Phillips, & Chapman, Citation1999; Smith & Turner, Citation1995; Tohidian & Rahimian, Citation2019; Van Engen, Citation2008; Walsham, Citation1991). According to Faghih et al. (Citation2016, p. 3), “Metaphors efficiently simplify the most complex phenomena and issues by putting emphasis on their key qualities. So, they are beneficial tools for the understanding of the organization and its complexities.” Fractal is “any of various extremely irregular curves or shapes for which any suitably chosen part is similar in shape to a given larger or smaller part when magnified or reduced to the same size” (Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Citation2002, p. 462). Initially, it had been a mathematical and geometrical term proposed by the mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot to show “roughness” and “self-similarity” in nature (Gomory, Citation2010, p. 378). The term stands at the connecting border of natural mathematics and philosophy. Philosophically, natural mathematics is the recurring mathematical Geist, a term borrowed from German that simultaneously means mind and spirit, widespread in nature (e.g. fractal could be seen in leaves, snowflakes, shells, etc.) (Figure ).

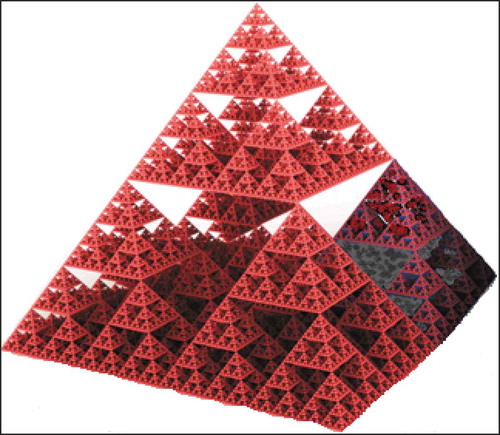

The Sierpinski Triangle is another familiar example of fractal. This fractal is a fixed set fractal with infinite subdivided micro-equilateral triangles which make an overall shape of a macro-equilateral triangle based on recursionFootnote1 (Figure ).

If we assume formal organizational power distribution in any organization through organizational chart as a pyramidal distribution of organizational power, then for a two-dimensional visualization of the concept we can use the Sierpinski power triangle metaphor. In this metaphor, minor triangular powers within the organization constitute major triangular and systemic body of organizational power. Later this metaphor will be used through the paper to clarify the fractal anatomy and ontology of organizational power.

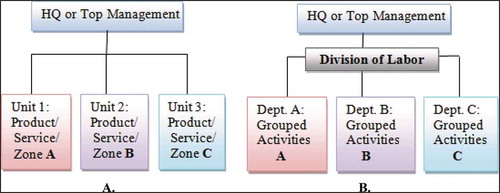

Metaphorically, self-organization (Baas, Citation2002), self-similarity (Mandelbrot, Citation1983), discipline and symmetry-making (Cattani, Citation2010), fractal growth (Sander, Citation1986), and evolution (Burlando, Citation1993) as fractals’ characteristics could be used in organization studies. As a fractal is a structural phenomenon in nature, analogously we can observe structurally organizational fractals (Figure ) via divisionalization, departmentalization, decentralization, de-bureaucratization, diversification, etc. The justification of such a proposition is the belief that they lead to the organization, dissemination, and expansion of one organizational structuralization philosophy in countless shapes and forms. Furthermore, each unit, division, department, etc., is the smallest constituting structural entity that reflects in a segmented wholeness, hence organizational fractal structure. In addition, work, authority, power, and responsibility distribution through and organization could potentially lead to organizational fractals for each entity.

2.2. Fractal organizations

Applying fractal concept for organizations is a recent academic tendency for illustrating organizational change management. For instance, Hoverstadt (Citation2011) tried to present effective tools for the analysis and development of sustainable organizations, which he entitled as “fractal organizations”. His fractal organization had a fractal structure efficient for managing complexity and dealing with differences and empowered managers at different organizational levels to be effective decision-makers; letting alone where, their position was placed in the organizational hierarchy. However, another author has applied the fractal concept differently. Raye (Citation2014) has used the fractal organizational concept to discuss connections and communications. He believes:

Fractal organisation theory recognises an emergent human operating system that mimics nature in its capacity for creativity, adaptation, vitality, and innovation. The qualities of a fractal organisation include shared purpose and values that create pattern integrity; universal participation in ideas and solutions for continuous improvement; decision making at functional levels; leadership devoted to universal leadership; and competition energy directed outwards instead of inwards. Relationship development enables the effective flow of information between individuals and among teams. At all levels of a fractal organisation, members share information iteratively and make decisions collectively in response to constantly changing conditions. (p. 50)

On the other hand, a group of authors have tried to present some models for designing fractal layouts in manufacturing organizations. According to Saad and Lassila (Citation2004, p. 3529) “In fractal organizations, system flexibility and responsiveness are achieved by allocating all manufacturing resources into multifunctional cells that are capable of processing a wide variety of products.” Venkatadri, Rardin, and Montreuil (Citation1997, p. 911) believed “fractal layout organization … has been introduced as an alternative to the more traditional function and product organizations.” Hence, Venkatadri et al. (Citation1997) have tried to introduce a fractal shop floor layout with fractal cells for product organizations. Montreuil (Citation1999, p. 501) has also proposed a layout for a manufacturing fractal organization, thus he developed a fractal alternative “for manufacturing job shops which allocates the total number of workstations for most processes equally across several fractal cells,” and believed “One result is enormous flexibility because each cell can produce nearly every product.”

2.3. What is power?

Nevertheless, the fractal concept has not been applied to organizational power so far. First, what is power? Power is a ubiquitous and multifaceted concept. However, it is a tangible cognitive entity (Dépret & Fiske, Citation1993; Dijk, Citation1988; Fleischmann, Lammers, Conway, & Galinsky, Citation2019; Guinote, Citation2007; Krackhardt, Citation1990) with usually countless origins. Thus, it is a “puzzling notion” (Uphoff, Citation1989, p. 295) that social sciences’ scientists and theoreticians analyzed it and its contexts to shed light on its definition, formation, preservation, classification, and other epistemological aspects of the phenomenon. Clegg (Citation2015, p. 1) believes “Despite its ubiquity, power is arguably one of the most difficult concepts to make sense of within the social sciences.” Therefore, “Power can be defined in multiple ways, depending on special epistemological and philosophical frameworks” (Ramos et al., Citation2019, p. 2). Furthermore, it is a context-related entity (Li, Citation2006), which takes different shades of meaning in various contexts. As a few examples, it has been studied by philosophers, sociologists, psychologists, political and organizational researchers within different contexts (e.g. institutional context (Fairclough, Citation2019; Qu, Citation2018); cultural context (Garbuzov, Ramazanov, Nikolaev, Makarov, & Kalashnikova, Citation2019); social context (Collins, Citation2019); sexual context (Gill & Orgad, Citation2018); organizational context (Park, Kim, Chang, Lee, & Sung, Citation2018); etc.). The contextuality of power broadens its realms of definition. Russell (Citation1938) defined power as the intended effects production; while Weber (Citation1947) saw power as the imposing of desired intentions against potential resistance. Further definitions view power as a latent force (Bierstedt, Citation1950), decision-making participation (Laswell & Kaplan, Citation1950), social class capacity in realizing its objective and specific interests (Poulantzas, Citation1975), preferred outcomes causation (Simon, Citation1957), etc. Hence, Perspectivism is the prevalent mode in power definitions. According to McNamee and Glasser (Citation1987, p. 80) “ … the bewildering variety of conceptualizations of power lies in what particular theorists and their theoretical backgrounds are willing to ‘allow’ into their analysis.” Theoreticians’ expertise inevitably drives them toward grasping a particular perspective on power and the result is a biased epistemology. In sum, power means different things to different people and hence there is not any universal and all-embracing definition. However, power encapsulates the following general concepts: (1) relations (McGuinness & Kelly, Citation2007); potentiality and influence (Meliá, Oliver, & Tomás, Citation1993), legitimacy (Scherz, Citation2019) and illegitimacy (Ratcliff & Vescio, Citation2018), status (Hasty & Maner, Citation2019); will (Nietzsche, Kaufmann, & Hollingdale, Citation1967), domain (Deng, Zheng, & Guinote, Citation2018), self-interests (Lukes, Citation2007), structure (Domhoff, Citation2017) struggle (Lind, Citation2018), distribution (Cepik & Möller, Citation2017), monopoly (Kopecký, Citation2017), control (Rhodes, Citation2018), hegemony (Connell, Citation2016), dominance (Aiello, Tesi, Pratto, & Pierro, Citation2018), inequalities (Avent‐Holt & Tomaskovic‐Devey, Citation2019), authority (Sledge, Citation2016) and so forth. Surprisingly all of the adjacent concepts to power are generally present in organizations.

2.4. Approaches to studying power

Furthermore, the approaches to studying power are one of the reasons of dissonance among the theorists. Wherever there are human and a framing structure of interrelations, the bedrock for the emergence of power is ready. Organizations have both of them. Therefore, they are the incubators and hives for power emergences, formations, and dynamism. McNamee and Glasser (Citation1987, p. 80) point out that, “some power theorists emphasize power resources, while others emphasize power processes, and still others emphasize power outcomes.” Nevertheless, power could be approached at least from two perspectives: a macrocosmic view with external and collective manifestations such as governmental power, state power, global power, etc., or from a microcosmic view, which embraces topics such as inequalities and gender relations, structure of power within family, etc. Organizational power, the subject matter of the present paper, falls within the former broad class. The unit of analysis in the first approach is the system, but in the second approach is the individual or the smallest constituting blocks in relation to the system(s).

On the other hand, according to (Peiró & Meliá, Citation2003) power is bifactorial: it is either formal or informal. The first is provided by the structure (hence, organization) and the second by the relationships (Ramos et al., Citation2019). Concerning the organizational relations, power could be discussed inward or intra-organizationally and outward or inter-organizationally. Formal organizational power manifests itself through power relations. So far formal “organizational power relations” have studied from different aspects, e.g. gender relations (Chernyak-Hai & Waismel-Manor, Citation2019; Hearn & Collinson, Citation2018), organizational interaction (Prabhakaran, Ganeshkumar, & Rambow, Citation2018), interpersonal influence (Lovrić, Lovrić, & Schraml, Citation2019), educational perspective (Horton, Citation2018), etc. On the contrary, informal power has usually hidden and invisible existence; e.g. Social networks’ power (Cross, Cross, & Parker, Citation2004; Ehin, Citation2004) and organizational politics (Guo, Kang, Shao, & Halvorsen, Citation2019; Russell, Citation2019). One of the influential researchers on power was Max Weber. To Weber (Citation1968, pp. 585, 637), a philosophical sociologist, the constituting fabric of organizational power, i.e. social relations within the context of interrelated organizational stakeholders, is basically impossible to be regulated benevolently since market-driven relations in Capitalism is absolutely impersonal in essence:

There is no possibility, in practice or even in principle, of any caritative [benevolent] regulation of relationships arising between the holder of a savings and loan bank mortgage and the mortgagee … or between a holder of a federal bond and a citizen taxpaper … stockholders and factory workers, or between industrialists and the miners who have dug from the earth raw materials used in the plants by the industrialists. The growing impersonality of the marketplace follows its own rules, disobedience to which entails economic failure and, in the long run, economic ruin…. Such absolute depersonalization is contrary to all the elementary forms of human relationship.

Thus, as power accumulates, within the organizational context and among the organizational stakeholders, it deprives of personalization and takes depersonalized attributes. In Mintzberg (Citation1984, p. 208), another influential researcher of organizational power, analysis of organizational power “coalition” is a focal point. He categorizes the organizational power configurations via the preliminary dichotomy of organizational coalitions as internal and external:

Influencers, or “stakeholders”-people who use “voice” to attain their needs through an organization … -may be divided into those with major time commitments to the organization (essentially the full-time employees or volunteers), who will be called internal, and the others, who will be called external. The former may be described as forming an internal coalition, the latter, an external coalition. (Mintzberg, Citation1984, p. 208)

According to Mintzberg (Citation1984) the relationship between the abovementioned internal (IC) and external coalitions (EC) defines the six following power configurations: (1) EC, dominated + IC, bureaucratic = Instrument; (2) EC, passive + IC, Bureaucratic = Closed System; (3) EC, passive + IC, personalized = Autocracy; (4) EC, passive + IC, ideologic = Missionary; (5) EC, passive + IC, professional = Meritocracy; (6) EC, divided + IC, politicized = Political Arena.

Moreover, large-scale organizations in relation to their external environment apply adaptation and/or domination strategies to expand their organizational powers (McNeil, Citation1978). Perrow (Citation1972, p. 199) believed, “The environment of most powerful organizations is well controlled by them, quite stable, and made up of other organizations, ones they control.” Inter-organizational power basically stems from the propensity for maintaining environmental hegemony. Thus, power is a core concept in studying inter-organizational relationships (Huo, Tian, Tian, & Zhang, Citation2019). It is noteworthy that such conceptualization of inter-organizational powers originates from presumption of organizations as open systems (Aldrich, Citation1971). However, inter-organizational relationship is a multifaceted phenomenon and it has recently studied from different perspectives; e.g. inter-organizational governance (Roehrich, Selviaridis, Kalra, Van der Valk, & Fang, Citation2019), inter-organizational communication networks (Pilny & Proulx, Citation2019), inter-organizational culture (Larentis, Antonello, & Slongo, Citation2019), etc. On the other hand, the adaptation strategy could be a legitimacy gaining maneuver, since, “Embedded in world society, organizations adapt to environmental expectations for the sake of increasing their legitimacy” (Franke, Citation2017, p. 6). Furthermore, organizational dependency is a pivotal factor in the inter-organizational power analysis. Dependency defines the external magnitude of organizational power. Dependency and exchange are two interrelated concepts. According to Emerson (Citation1962), exchange leads to dependency that embraces power implicitly. Thus, exchange relation is one of the factors of inter-organizational power and it grows by increasing the scope and number of exchanging resources (Cook, Citation1977). Hence, resource dependence is the underlying reason for the formation of power (Franke, Citation2017). Such an organizational power is a resource-dependent power and usually emerges between the organizations. In resource-dependent power, “power imbalance” and “mutual dependence” (Casciaro & Piskorski, Citation2005, p. 167) are two significant topics of scientific enquiry.

Foucault’s ideas have had great effect in organization studies (Burrell, Citation1988; Raffnsøe, Mennicken, & Miller, Citation2019). In contrary to the prevailing idea, power formation is a bottom-up process. The power of the entity on the top boils from deep structures of power formed beneath. That is the powers on the top necessarily must stand on the shoulders of the micro-powers beneath. Imagine a hierarchy of power and use a negation approach: i.e. by deleting some hierarchies of power on the top, power still resides but distributes among the remaining hierarchies and takes new forms. However, by deleting the powers beneath the foundation and the structure of power become shaky and poor. Thus, Foucault’s approach in analyzing social power is a “bottom-up” process; i.e. an ascending approach, therefore “One must rather conduct an ascending analysis of power starting, that is, from its infinitesimal mechanisms, which each have their own history, their own trajectory, their own tactics … ” (Foucault, Citation1980, p. 99). Power to him is “a cluster of relations” (Citation1980, p. 199); and power in essence is not a negative and repressive entity but a productive phenomenon; therefore he claims, “ … If power were never anything but repressive, if it never did anything but to say no, do you really think one would be brought to obey it? What makes power hold good … is simply the fact that … it traverses and produces things, it induces pleasure, forms of knowledge, produces discourse. It needs to be considered as a productive network which runs through the whole social body” (Foucault, Citation1980, p. 119). Furthermore, he believes power is not possessed but the individuals are embedded within a chain of power (Foucault, Citation1980, p. 98). Hence, formal power within an organization is not a personal possession brought to the organization from the outside but it is because of “organizational embeddedness” as, “the totality of forces (fit, links, and sacrifices) that keep people in their current organization” (Ng & Feldman, Citation2007, p. 336) and inevitable placement in organizational power network that organizational power emerges.

2.5. Power connectivity to politics

Finally, Pfeffer (Citation1992, p. 33), a scholar of organizational power studies, interrelated power to the organizational politics and defined organizational politics, “as the exercise or use of power, with power being defined as a potential force.” This approach to organizational power first defines it as a phenomenon political in essence and second as a potential entity. Moreover, to Pfeffer, organizational power was a necessary means of organizational decision-making (see, Pfeffer, Citation1981; Pfeffer, Salancik, & Leblebici, Citation1976; Salancik & Pfeffer, Citation1974; Salancik, Pfeffer, & Kelly, Citation1978). Such view of power originates from the organizational pragmatism. He asserts although power is connotatively a negative word, at least in American culture (Pfeffer, Citation1992, p. 33) and accentuates Kanter’s (Citation1979) quotation on power who wrote, “Power is America’s last dirty word. It is easier to talk about money- and much easier to talk about sex- than it is to talk about power,” we need to approach power pragmatically and cultivate “potential risks and advantages of power” instead of “ignoring the processes of power and influence.”

In brief, based on the above reviews on power, power in organization is a ubiquitous context-related and multifaceted concept with necessary complicated relation network for its emergence, which forms and accumulates in a “bottom-up” process and should be also analyzed and studied through the same “bottom-up” process.

3. Research design

The paper is a conceptual endeavor to theorize the characteristics of organizational power through a fractal metaphor: the Sierpinski Triangle. The justifications behind using a fractal are the distributive and recursive characteristics of power. In other words, power as an abstract entity could not be explained without considering its distribution in the form of micro-powers among the receivers of power. Moreover, it is recursive since power is inherently involved with repeated accumulation of itself to emerge. This accumulative process proceeds on with making self-affinity and self-similarity. Thus, power could not be explained, formed, and expanded unless by itself (recursion).

On the other hand, conceptual visualization of organizational power in this research is triangular since the organizational chart usually takes the form of a triangle. Additionally, the triangular form can also reflect the hierarchical, pyramidal, distributive, recursive, accumulative, dependent, comparative, and unequal properties of power. Therefore, in the discussion section, the author first discusses the undergirding bedrock of power ontology in terms of its constituting elements for power not only in its potential emergence but also in its pragmatic manifestation. Next, the fractal nature of power in respect to its distribution either as a focusing fractal or as the opposite a webbing fractal was discussed. Then, the ontology of organizational power in its formal and informal manifestations with the characteristics of directionality in the formal and dimensionality in the informal emergences was conceptualized. Finally, the fractal characteristics of the organizational power were concluded. Figure has schematically summarized the paper’s design for the conceptualization of the fractal power.

4. Discussions

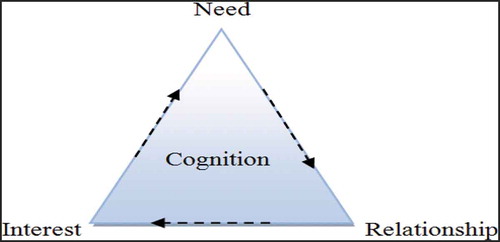

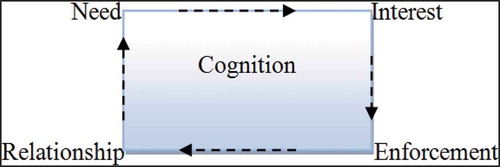

“Power” is an abstract concept with concrete tangible manifestations. Usually in interpretation and definition, researchers are busy with the outcomes generated by power not the essence and nature of power as a phenomenon. Hence, in this paper, the ontological concept of power is built upon a triangular necessity that embraces the three fundamental constructing components of power: (1) interest, (2) need, (3) relationship (Figure ). Initially, power shapes in a cognitive context. In other words, power is among animate creatures with the faculty of cognition, otherwise it is a force, which is a subject in physics. That is without the cognitive element (human) or its omission there is no such a power. Moreover, an isolated and separate entity does not form power. There must be at least a “relationship”. Power is a structure-bound phenomenon, i.e. it emerges within specific relationship structures. These structures could be economic, political, social, cultural, professional, etc. The structurality of power is deeply rooted in the prerequisite of a fundamental constituting component of any power, which is relationship or interdependence. The relationships within any framing structure superimpose special characteristics on the essence of power. In other words, power metaphorically is a liquid in a structural container; it takes the shape of the structure (container). Moreover, relationship has a tendency toward directionality. What determines the dimensionality of this relationship is the existence of “need”. Without “need” there will be no “interest”. Furthermore, the two elements of “need” and “interest” do not show inferiority or superiority, i.e. “need” is not only in the inferior but also in the superior. For example, if an inferior finds his interest in subjectivity to fulfill his social needs such as welfare, security, etc., the superior finds his interest in supremacy on the subjects to fulfill his need for the expansion and maintenance of his power.

The dynamism of the three components shapes power in potential. To acquire outward manifestation a fourth indispensable element must be added to the previous triple dynamism: enforcement. Enforcement is the necessary factor that leads to influence. By enforcing, power shows its concrete manifestation. Such a power is hence de facto (Figure ).

Moreover, power has a distributive characteristic, i.e. no matter how much centralized or decentralized, power always distributes among numerous organizational entities, departments, people, etc., but with centralism or decentralism in orientation and the philosophy and intension behind the distribution. In other words, centralized unaccountable distribution of power could be for dictatorial intensions and a decentralized accountable and participative power distribution for the fulfillment of democratic motives.

Schematically, in centralized power, the distributed power among the entities has the focal orientation and in the decentralized power, the distributed power usually makes a network of coexisting micro-powers (Figure ).

Figure 7. Visualized philosophic concepts of A. power centralization (focusing): Distribution with focal orientation vs. B. power decentralization (webbing): Distribution with webbing orientation (power decentralization) with major powers in the center, and minor powers around

By decentralization of power, there is more possibility of power fractals emergence (Figure , B).

Finally, Power always has two sides the holder and the receiver. The holder of power has the power exertion potentiality and the power consequences’ receiver could be either an active or a passive receiver. The number of power consequences’ receivers defines the span of power realm. If they accept the power exertion passively without any resistance, it leads to organizational dictatorship; and in contrary by playing an active role, they can affect the structure and formation of organizational power and collectively lead it to organizational democracy.

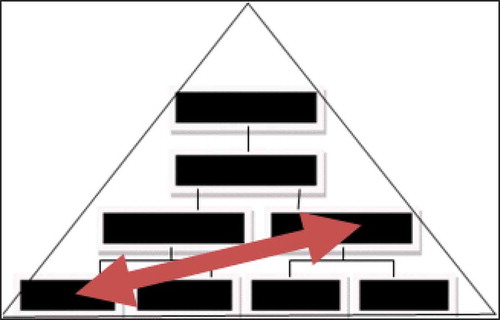

Organizational power’s configuration could be assumed at least in two general manifestations: (1) micro-powers, and (2) macro-powers. The fractal concept of organizational power embraces the two philosophical assumptions of power configuration formation within organizations. That is, micro-organizational powers deep down the organizational hierarchy through an upward intermingling and fabrication join together to make the larger powers and the large powers incessantly lead the same process to end up with the largest and the most dominant organizational power(s) high on the hierarchy (Figure ).

Figure 8. The schematic assumption of organizational power formation and dissolution as a fractal concept envisaged via Sierpinski Power Triangle metaphor.

Metaphorical assumption of organizational power through Sierpinsk Triangle reflects a coalescent and unified integrity (i.e. organization power) which is made up of numerous interrelated coexisting coalitional micro-entities with upward orientation (i.e. micro-organizational powers) to reach the top. Such an upward propensity of power within organizations leads to organization power formation as a recognizable social entity. Furthermore, Sierpinski Power Triangle metaphor reflects the following characteristics for power within organization:

(1) Incremental formation: Organizational power formation is a gradual but continuous process, which incrementally forms in an upward trend. Therefore, in order to study powers and coalitions within any organization we need to bear in mind, first the upward fabricating structures of organizational needs, interests, and relationships; in other words, we should identify the needs and their sources, which make specific organizational inclinations inter-personally, between groups, networks, and coalitions. Such inclinations define the organizational interests and specify the necessary relationships to fulfill the interests. The expansion of interest groups within the organizations and their connection, coalescence and relationship with other interest groups leads to power networks, which their symbiotic relationships and coalitions make larger fractal powers and so forth to the peak. The power accumulates at the top, i.e. the peak is the summation of the formal organizational powers beneath. Second, the distribution of power entities through the triangle metaphor conveys the convergent power distribution tendency at the top and the divergent distributive propensity toward the base. As we approach the top, the degree of power convergence adds up and conversely in the opposite direction as we approach the base of the power triangle/pyramid divergence becomes dominant. In other words, the nature of power necessitates such a pyramidal distribution of power, which incrementally accumulates and intensifies upward and abates downward.

(2) Mutual inferiority and superiority: Always the micro-powers at the base of the pyramid are inferior to the ones higher in the organizational hierarchy or macro-powers. However, the power inferiority and superiority is a comparative concept; i.e. a power superior to a below inferior ranked micro-power, is itself inferior to a power above in the organizational chart/hierarchy.

(3) Power on the basis of power: Every larger power consists of multiple micro-powers; i.e. power begets power. It shows the recursive characteristic of organizational power (“Informally, recursion involves having an entity or action that refers to, acts on or is based on a copy or type of itself. Like … self-reflecting mirrors” (Mutalik, Citation2019). Therefore, the smallest entity of the most supreme organizational power could be decomposed to countless minor powers.

(4) The whole could not be separated from the pieces: The supreme organizational power and its constituting macro-powers, which are the result of plethora of micro-powers, could not exist in solitary. That is, the foundation of the upper powers is based on the powers below. By omitting the micro-foundations there would be not macro-foundations to place upon them and hence no ground for organizational power formation. Therefore, the whole finds its existence and ontology by the integrity of the pieces.

(5) Reflectivity: The same characteristics within the minor organizational powers could be found (reflected) in the macro-power and hence forward to the whole hierarchy of organizational power.

(6) The power dynamism of the whole originates from the minor constituting powers’ dynamism. Such dynamism has a domino effect, which starts from the bottom to reach the peak.

Therefore, by considering the abovementioned discussions and power characteristics the following proposition could be proposed:

If we assume each organizational chart/coalition (Figure ) as the equilateral triangles constituting the Sierpinski Triangle, then the fractal formation of formal organizational power in an organization or a governmental body should be the result of innumerable simultaneously major-minor organizational charts/coalitions (hence, micro-triangles and macro-constituted triangles, Figures & 1).

Figure 10. A hypothetical manifestation of a micro organizational power fractal (hence, triangle) based on Sierpinski Power Triangle metaphor developed in the paper

Figure 11. The process of formal organizational power formation within an organization/bureaucracy/governmental body based on Sierpinski Power Triangle metaphor developed in the paper

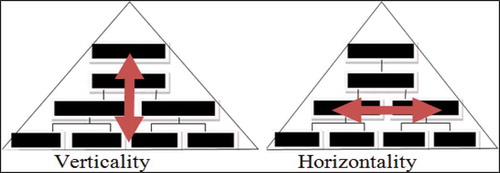

Organizational chart itself is a solidification of the formal relationships and specification of their domains of power within an organization. Since it takes relationship to build power structure, organizational power takes directionality. The relationship could be equal (horizontal), superior, or inferior (vertical). The horizontal direction is among the workers within the same unit, department or organizational level, but the vertical power direction is either from top to bottom (line to staff) or vice versa, bottom to the top (staff to line). Greiner and Schein (Citation1989) call the vertical powers “upwards” or “downwards” but they do not assume a horizontal power. The horizontal power is the state of power neutrality; that is the state when there is no power exertion. Although there is interdependency (relationship), there is no superiority or inferiority and hence it is neutral.

Furthermore, power is simultaneously a collective and accumulative concept. Collective, since it lies in the network and coalition of people although in totalitarian or dictatorial systems one person or a group of elites (oligarchy) would have superdominance. Accumulative, since it starts from the minor powers of the base of the pyramid/hierarchy and by passing each hierarchical level, the minor powers below accumulate in the next level and so forth to the top. Hence, two ontological concepts of power emerge: (1) legitimacy and (2) enforcement. Both of these two coexisting entities of power are directional; that is, the legitimacy of power is always a bottom-up process; i.e. the subjects in general and hence the employees in organizations from the very base of the power pyramid should feel the power to be legitimate; otherwise, the power always lacks one of its fundamental aspects to be agreeable on the public/employees eyes. Additionally, power enforcement in its formal manifestation is always a top-down process; i.e. the organizational entity(ies) on the upper level could enforce power and dominance on the lower level(s). The Sierpinski Power Triangle metaphor presented by the paper not only could reflect both of the abovementioned entities’ directionality in a formal power manifestation (Figure ) but also dimensionality of power in its informal organizational formation (Figure ).

Informal organizational power mostly takes dimensional deviation since it usually violates the top-down vertical direction of power exertions in organizations as well as the axiomatic exertion of organizational power from the upper hierarchy/level to the lower entities, since the opposite could also take place in the informal exertion of power, i.e. from an inferior entity to a superior one.

On the other hand, power magnitude is a result of two simultaneous abstract entities that are always present in organizations: (1) comparison, and (2) dependency. The dependency of organizational units, department, divisions, labors, human resources, etc., for the accomplishment of the organizational tasks in a minor scale and the organizational objectives in a macro scale result bring about a human state of mind: comparison. Power magnitude evaluation and assessment is always the result of dependency and comparison. The macro-powers on the upper levels of Sierpinski Power Triangle axiomatically bear more formal power on the eye of the organizational beholders at the bottom who are dependent to the upper level powers and compare their positions and situation in respect to them to have an evaluation for the definition of their own and the other entities’ of the organizations.

Moreover, the fractal metaphor of power within organizations via the Sierpinski Power Triangle can show that power is basically a manifestation of inequality; otherwise, it was not possible to be formed. Let us assume a condition in an organization where there is not any condition of superiority or inferiority and the organizational chart share the same equal power to all of the organizational entities, then could we have any organizational power? Does equality lead to power? The answer is obvious. Such an assumption is not a violation and refutation of democratic organizational power. Since even in the democratic manifestation of power there are still some man-made institutions such as laws, regulations, bureaucracy, etc., that are larger and non-equal entities in comparison to the power of people in a democratic organization. In the Sierpinski Power Triangle, the formal power of each upper organizational level is more than the levels below. Thus, it is possible to propose the concept of Power Gap as the undergirding phenomenon, which accumulates and forms the hierarchy of organizational power.

Finally, borrowing Marx’s class struggle concept and the introduced power gap, any organization could be also a manifestation of power struggle. Accordingly, the paper’s author believes in any organization there are at least three power classes (Figures and 1):

Organizational Aristocratic Power, on the peak of the power pyramid

Organizational Bourgeoisie Power, in the middle of the power pyramid

Organizational Proletariat Power, at the base of the organizational power pyramid

The Organizational Aristocratic Power is the dominant organizational power. This typology of power rests in the line managers and top white-collar workers. The board of directors and the CEOs are making this class of organizational power. Dominancy is the prevailing characteristic of the Aristocratic Power in organizations. The second power manifestation in organizations is Organizational Bourgeoisie Power. The middle managers constitute this organizational class. They have an intermediary function in the organizational power; i.e. they are the Aristocratic Power’s medium to convey, justify, and explain the decisions, policies, and strategies that are made by the organizational aristocrats. Moreover, they are usually technical or operational experts in the organizations. Finally, the base of the pyramid is populated by a great bulk of the organizational employees. They potentially have Organizational Proletariat Power. Their exertion of power to the peak always rests in their degree of efficiency in union or association making. Since organizations are mainly populated by the organizational proletariats, their powers are always under the careful scrutiny and channeling by the organizational aristocrats. Organizational formality and rule of law (RoL) besides organizational goal setting are some of the implicit channeling and controlling techniques by the aristocrats. These three classes of power are usually in potential rivalry and struggle. They make the impetus behind the organizational power dynamism. However, there are also subtle structures of power fractals, coalitions, and rivalries even among the members of each class.

Figure 15. Organizational power classes symmetrical expansion

5. Research recommendations

Building upon Friedrich Nietzsche’s idea (Citation1967), quoted below, and the distributive nature of power, discussed above, power distribution may potentially lead to division of responsibility via the inevitable division of labor in the organizations and could be resulted in the expansion of organizational unaccountability:

This is achieved through division of labor (so that no one any longer possesses the full responsibility): the lawgiver- and he who enacts the law; the teacher of discipline- and those who have grown hard and severe under discipline. (p. 383)

Therefore, there should be always a Hegelian antithesis shaped as organizational counter-power embedded in the organizations to be able to moderate and balance the potential severity and dictatorial deviations of power. The paper’s author believes such counterbalancing measures are fundamentally necessary; especially in public and governmental organizations in order to prevent their bureaucracies to transform to a crushing force over the citizens. Some of the counterbalancing recommendations are the empowerment and effectuation of check and control mechanisms, promotion of organizational democracy and the culture of organizational accountability, implementation of efficient suggestion systems, etc.

6. Future research considerations

The fractal concept could be also pragmatically applied in future researches on tourism, e.g. on the fractal techniques to evenly distribute the tourist attractions and facilities through a region or a country to ensure sustainable and symmetrical benefit and development for all region. Additionally, the concept could be used in quality management. That is to devise production or service plans, or to set production or service strategies and techniques which guarantee the superb similarity of high quality in all the manufacturing outlets or service providing branches.

7. Conclusion

Management deals with a group of organized humans with different degrees of a “will to interest” in a social institution. Organizations are a colony of power. However, organizational power could not be detached from its social, economic, political and cultural ecosystems/contexts. Metaphorically, organization is an animate being that nourishes and feeds within its ecological habitat. Applying the philosophy of fractals to the organizations is applying natural philosophy to the realm of organization studies. Such a view looks at organizations as living organisms, i.e. open systems that could have symmetrical evolution for dissemination and sharing of knowledge, information, communication, technique, quality, power, etc. Organizational power, discussed through the paper, formally distributes within hierarchical levels, which implies a pyramidal structure of power. The formal triangular structure of power, reflected by the organizational charts, also induces such mental image of power distribution within the organizations. The axiom: “power begets power” is obviously traceable from the base to the peak of the pyramid. The axiom inherently defines the recursion in organizational power formation. Each level fabricates the foundation for the next upper level and so on up to the peak. The peak finds its superpower from the numerous fabricated micro-fractal and lower level powers, which are so densely intermingled by the individual and groups’ “will to interest” which find their fulfillment of the interest in conserving the power structure; i.e. they act as the pillars of the power structure. Hence, it calls for relationship as a fundamental entity for the formation of power within organizations. These relationship fractals put up the fractal structure of the organizational power and their accumulation lead to the macro-organizational power formation. Furthermore, the perception of an organizational power magnitude is a cognitive action that relies on dependency and comparison. That is the inferior levels of fractal power and those who occupy the inferior level positions depend on the superior levels of power high on the organizational hierarchy to estimate and shape their own perception of power magnitude. The individual cognition of organizational power magnitude for any entity within the organization is the result of the comparison between his own power and the other entities’ powers. Finally, the paper concludes that organizational power is ontologically hierarchical, pyramidal, distributive, recursive, accumulative, dependent, and comparative, which are the results of unequal distribution of power within organizations.

Competing interests

The author claims that he has no conflict of interest to be cited here.

Acknowledgements

To Prof. Nezameddin Faghih, a kind heart and a brilliant mind who introduced me with the fractal concept.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Amir Forouharfar

Amir’s research focuses on four core arenas. First, philosophy and its application in shedding light on fundamental managerial and organizational concepts such as power in organization. Second, entrepreneurship and its contribution to states’ political stability and economic development. Third, strategic management and its application in states’ large-scale social and economic improvement. Fourth, public administration and its scientific study in the areas of bureaucracy, good governance, and public mind. Currently he is seeking a postdoctoral opportunity in any of the abovementioned arenas.

Notes

1. “The determination of a succession of elements (such as numbers or functions) by operation on one or more preceding elements according to a rule or formula involving a finite number of steps” (Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Citation2002, p. 978).

References

- Aiello, A., Tesi, A., Pratto, F., & Pierro, A. (2018). Social dominance and interpersonal power: Asymmetrical relationships within hierarchy‐enhancing and hierarchy‐attenuating work environments. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 48(1), 35–20. doi:10.1111/jasp.2018.48.issue-1

- Aldrich, H. (1971). Organizational boundaries and inter-organizational conflict. Human Relations, 24(4), 279–293. doi:10.1177/001872677102400401

- Armenakis, A. A., & Bedeian, A. G. (1992). The role of metaphors in organizational change: Change agent and change target perspectives. Group & Organization Management, 17(3), 242–248. doi:10.1177/1059601192173003

- Avent‐Holt, D., & Tomaskovic‐Devey, D. (2019). Organizations as the building blocks of social inequalities. Sociology Compass, 13(2), e12655. doi:10.1111/soc4.12655

- Baas, A. C. (2002). Chaos, fractals and self-organization in coastal geomorphology: Simulating dune landscapes in vegetated environments. Geomorphology, 48(1–3), 309–328. doi:10.1016/S0169-555X(02)00187-3

- Bierstedt, R. (1950). An analysis of social power. American Sociological Review, 15, 730–736. doi:10.2307/2086605

- Boxenbaum, E., & Rouleau, L. (2011). New knowledge products as bricolage: Metaphors and scripts in organizational theory. Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 272–296.

- Burlando, B. (1993). The fractal geometry of evolution. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 163(2), 161–172. doi:10.1006/jtbi.1993.1114

- Burrell, G. (1988). Modernism, post modernism and organizational analysis 2: The contribution of Michel Foucault. Organization Studies, 9(2), 221–235. doi:10.1177/017084068800900205

- Cafferata, G. L. (1982). The building of democratic organizations: An embryological metaphor. Administrative Science Quarterly, 27, 280–303. doi:10.2307/2392304

- Carr, A., & Leivesley, R. (1995). Metaphors in organisation studies: A retreat to obscurantism or ideology in” drag”? Administrative Theory & Praxis, 17(1), 55–66.

- Casciaro, T., & Piskorski, M. J. (2005). Power imbalance, mutual dependence, and constraint absorption: A closer look at resource dependence theory. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(2), 167–199. doi:10.2189/asqu.2005.50.2.167

- Cassell, C., & Lee, B. (2012). Driving, steering, leading, and defending: Journey and warfare metaphors of change agency in trade union learning initiatives. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 48(2), 248–271. doi:10.1177/0021886312438861

- Cattani, C. (2010). Fractals and hidden symmetries in DNA. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2010, 1–31. doi:10.1155/2010/507056

- Cepik, M., & Möller, G. (2017). National intelligence systems as networks: Power distribution and organizational risk in Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. Brazilian Political Science Review, 11(1). doi:10.1590/1981-3821201700010001

- Chernyak-Hai, L., & Waismel-Manor, R. (2019). Gendered help at the workplace: Implications for organizational power relations. Psychological Reports, 122(3), 1087–1116. doi:10.1177/0033294118773483

- Cleary, C., & Packard, T. (1992). The use of metaphors in organizational assessment and change. Group & Organization Management, 17(3), 229–241. doi:10.1177/1059601192173002

- Clegg, S. (2015) Power. Oxford Bibliographies Website, DOI: 10.1093/OBO/9780199756384-0068 https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199756384/obo-9780199756384-0068.xml

- Collins, P. H. (2019). The difference that power makes: Intersectionality and participatory democracy. In O. Hankivsky & J. Jordan-Zachery (Eds.), The palgrave handbook of intersectionality in public policy (pp. 167–192). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Connell, R. (2016). Masculinities in global perspective: Hegemony, contestation, and changing structures of power. Theory and Society, 45(4), 303–318. doi:10.1007/s11186-016-9275-x

- Cook, K. S. (1977). Exchange and power in networks of interorganizational relations. Sociological Quarterly, 18(1), 62–82. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.1977.tb02162.x

- Cornelissen, J. (2006). Metaphor in organization theory: Progress and the past. Academy of Management Review, 31(2), 485–488. doi:10.5465/amr.2006.20208700

- Cornelissen, J. P., Kafouros, M., & Lock, A. R. (2005). Metaphorical images of organization: How organizational researchers develop and select organizational metaphors. Human Relations, 58(12), 1545–1578. doi:10.1177/0018726705061317

- Cross, R. L., Cross, R. L., & Parker, A. (2004). The hidden power of social networks: Understanding how work really gets done in organizations. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Press.

- Daft, R. L., & Weick, K. E. (1984). Toward a model of organizations as interpretation systems. Academy of Management Review, 9(2), 284–295. doi:10.5465/amr.1984.4277657

- Deng, M., Zheng, M., & Guinote, A. (2018). When does power trigger approach motivation? Threats and the role of perceived control in the power domain. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 12(5), e12390. doi:10.1111/spc3.v12.5

- Dépret, E., & Fiske, S. T. (1993). Social cognition and power: Some cognitive consequences of social structure as a source of control deprivation. In G. Weary, F. Gleicher, & K. L. Marsh (Eds.), Control motivation and social cognition (pp. 176–202). New York, NY: Springer.

- Dijk, T. A. (1988). Social cognition, social power and social discourse. Text-Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of Discourse, 8(1–2), 129–157. doi:10.1515/text.1.1988.8.1-2.129

- Domhoff, G. W. (2017). The power elite and the state. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Ehin, C. (2004). Hidden assets: Harnessing the power of informal networks. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Emerson, R. M. (1962). Power-dependence relations. American Sociological Review, 27(1), 31–41. doi:10.2307/2089716

- Faghih, N., Bavandpour, M., & Forouharfar, A. (2016). Biological metaphor and analogy upon organizational management research within the development of clinical organizational pathology. QScience Connect, 2016(2), 4. doi:10.5339/connect.2016.4

- Fairclough, I. (2019). Deontic power and institutional contexts. Journal of Argumentation in Context, 8(1), 136–171. doi:10.1075/jaic

- Fleischmann, A., Lammers, J., Conway, P., & Galinsky, A. D. (2019). Paradoxical effects of power on moral thinking: Why power both increases and decreases deontological and utilitarian moral decisions. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 10(1), 110–120. doi:10.1177/1948550617744022

- Foucault, M. (1980). Truth and power. In C. Gordon (Ed.), Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings 1972-1977 by Michel Foucault. Brighton: Harvester.

- Franke, U. (2017). Inter-Organizational relations: Five theoretical approaches. International Studies. DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.99. https://www.oxfordre.com/internationalstudies/oso/viewentry/10.1093$002facrefore$002f9780190846626.001.0001$002facrefore-9780190846626-e-99#acrefore-9780190846626-e-99-bibItem-0002

- Garbuzov, D., Ramazanov, S., Nikolaev, N., Makarov, A., & Kalashnikova, N. (2019, July). Metaphysics of power and current geopolitics in social and cultural contexts. In 1st International Scientific Practical Conference” The Individual and Society in the Modern Geopolitical Environment”(ISMGE 2019). Atlantis Press.

- Gill, R., & Orgad, S. (2018). The shifting terrain of sex and power: From the ‘sexualization of culture’to# MeToo. Sexualities, 21(8), 1313–1324. doi:10.1177/1363460718794647

- Gomory, R. (2010). Benoît Mandelbrot (1924–2010). Nature, 468(7322), 378. doi:10.1038/468378a

- Greiner, L., & Schein, V. (1989). Power and organization development: Mobilizing power to implement change. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley.

- Guinote, A. (2007). Power affects basic cognition: Increased attentional inhibition and flexibility. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(5), 685–697. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2006.06.008

- Guo, Y., Kang, H., Shao, B., & Halvorsen, B. (2019). Organizational politics as a blindfold. Personnel Review, 48(3), 784–798. doi:10.1108/PR-07-2017-0205

- Hasty, C., & Maner, J. K. (2019). Power, status, and social judgment. Current Opinion in Psychology.

- Hearn, J., & Collinson, D. (2018). Men, masculinities, and gender relations. In R. Aldag (Ed.), Oxford research encyclopedia of business and management (pp. 1–35). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Horton, P. (2018). Towards a critical educational perspective on school bullying. Nordic Studies in Education, 38(04), 302–318. doi:10.18261/issn.1891-5949

- Hoverstadt, P. (2011). The fractal organization: Creating sustainable organizations with the viable system model. UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Huo, B., Tian, M., Tian, Y., & Zhang, Q. (2019). The dilemma of inter-organizational relationships: Dependence, use of power and their impacts on opportunism. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 39(1), 2–23. doi:10.1108/IJOPM-07-2017-0383

- Inns, D. (2002). Metaphor in the literature of organizational analysis: A preliminary taxonomy and a glimpse at a humanities-based perspective. Organization, 9(2), 305–330. doi:10.1177/1350508402009002908

- Kanter, R. M. (1979). Power failure in management circuits, harvard business review (july). Retrieved from https://hbr.org/1979/07/power-failure-in-management-circuits

- Kendall, J. E., & Kendall, K. E. (1993). Metaphors and methodologies: Living beyond the systems machine. MIS Quarterly, 17, 149–171. doi:10.2307/249799

- Kopecký, P. (2017). The rise of the power monopoly: Political parties in the Czech Republic. In Post-communist EU member states (pp. 139–160). Routledge.

- Krackhardt, D. (1990). Assessing the political landscape: Structure, cognition, and power in organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35, 342–369. doi:10.2307/2393394

- Larentis, F., Antonello, C. S., & Slongo, L. A. (2019). Inter-organizational culture and the cultural perspectives. In Inter-organizational culture (pp. 13–26). Cham: Palgrave Pivot.

- Laswell, H., & Kaplan, A. (1950). Power and society: A framework for political inquiry. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

- Li, X. (2006). Supportive leadership, learning capability, IT support capability, power and value appropriation in IOS supply chain network context. The University of Toledo.

- Lind, A. C. (2018). Power, gender, and development: Popular women’s organizations and the politics of needs in Ecuador. In The making of social movements in Latin America (pp. 134–149). Routledge.

- Lovrić, M., Lovrić, N., & Schraml, U. (2019). Modeling policy networks: The case of Natura 2000 in Croatian forestry. Forest Policy and Economics, 103, 90–102. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2018.03.002

- Lukes, S. (2007). El poder: Un enfoque radical. Siglo XXI de España Editores.

- Mandelbrot, B. B. (1983). The fractal geometry of nature (Vol. 173, pp. 51). New York: WH freeman.

- McCourt, W. (1997). Discussion note: Using metaphors to understand and to change organizations: A critique of gareth morgan’s approach. Organization Studies, 18(3), 511–522. doi:10.1177/017084069701800307

- McGuinness, R., & Kelly, C. (2007, March). Managing the relationship between knowledge and power in organisations. In Aslib Proceedings. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- McNamee, S., & Glasser, M. (1987). The power concept in sociology: A theoretical assessment. Humboldt Journal of Social Relations, 15(1), 79–104.

- McNeil, K. (1978). Understanding organizational power: Building on the Weberian legacy. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23, 65–90. doi:10.2307/2392434

- Meliá, J. L., Oliver, A., & Tomás, J. M. (1993). El poder en las organizaciones y su medición. El cuestionario de poder formal e informal. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 25(2), 139–155.

- Merriam-Webster’s collegiate dictionary. (2002). (10th). Massachusetts, USA: Springfield.

- Meyer, A. D. (1984). Mingling decision making metaphors. Academy of Management Review, 9(1), 6–17. doi:10.5465/amr.1984.4277746

- Mintzberg, H. (1984). Power and organization life cycles. Academy of Management Review, 9(2), 207–224. doi:10.5465/amr.1984.4277632

- Montreuil, B. (1999). Fractal layout organization for job shop environments. International Journal of Production Research, 37(3), 501–521. doi:10.1080/002075499191643

- Mutalik, P. (2019). The bulldogs that bulldogs fight. Quanta Magazine, April 17. https://www.quantamagazine.org/logic-puzzle-the-joy-of-recursion-20190417/

- Ng, T. W., & Feldman, D. C. (2007). Organizational embeddedness and occupational embeddedness across career stages. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 70(2), 336–351. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2006.10.002

- Nietzsche, F. W., Kaufmann, W., & Hollingdale, R. J. (1967). The will to power. New York: Vintage Books.

- Örtenblad, A., Putnam, L. L., & Trehan, K. (2016). Beyond Morgan’s eight metaphors: Adding to and developing organization theory. Human Relations, 69(4), 875–889. doi:10.1177/0018726715623999

- Palmer, I., & Lundberg, C. C. (1995). Metaphors of hospitality organizations: An exploratory study. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 36(3), 80–85.

- Park, J. H., Kim, C., Chang, Y. K., Lee, D. H., & Sung, Y. D. (2018). CEO hubris and firm performance: Exploring the moderating roles of CEO power and board vigilance. Journal of Business Ethics, 147(4), 919–933. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2997-2

- Peiró, J. M., & Meliá, J. L. (2003). Formal and informal interpersonal power in organisations: Testing a bifactorial model of power in role‐sets. Applied Psychology, 52(1), 14–35. doi:10.1111/apps.2003.52.issue-1

- Perrow, C. (1972). Complex organizations: A critical essay. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman.

- Pfeffer, J. (1981). Understanding the role of power in decision making. In Jay M. Shafritz y, & J. Steven Ott (Eds.), Classics of organization theory, Wadsworth (pp. 137–154).

- Pfeffer, J. (1992). Understanding power in organizations. California Management Review, 34(2), 29–50. doi:10.2307/41166692

- Pfeffer, J., Salancik, G. A., & Leblebici, H. (1976). The effect of uncertainty on the use of social influence in organizational decision making. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21, 2. doi:10.2307/2392044

- Pilny, A., & Proulx, J. D. (2019). Using interorganizational communication networks to predict terrorist attacks. Communication Research, 0093650219848271.

- Poulantzas, N. (1975). Political power and social class. translated by Timothy O’ Hagan. London: Humanities Press.

- Prabhakaran, V., Ganeshkumar, P., & Rambow, O. (2018). Author commitment and social power: Automatic belief tagging to infer the social context of interactions. arXiv preprint arXiv:1805.06016.

- Putnam, L. L., Phillips, N., & Chapman, P. (1999). Metaphors of communication and organization. Managing Organizations: Current Issues, 125–158.

- Qu, H. M. (2018, July). Institutional contexts and contingency effects of power. In Academy of management proceedings (Vol. 2018, no. 1, pp. 12280). Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management.

- Raffnsøe, S., Mennicken, A., & Miller, P. (2019). The foucault effect in organization studies. Organization Studies, 40(2), 155–182. doi:10.1177/0170840617745110

- Ramos, V., Franco-Crespo, A., González-Pérez, L., Guerra, Y., Ramos-Galarza, C., Pazmiño, P., & Tejera, E. (2019). Analysis of organizational power networks through a holistic approach using consensus strategies. Heliyon, 5(2), e01172. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01172

- Ratcliff, N. J., & Vescio, T. K. (2018). The effects of leader illegitimacy on leaders’ and subordinates’ responses to relinquishing power decisions. European Journal of Social Psychology, 48(3), 365–379. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2018.48.issue-3

- Raye, J. (2014). Fractal organisation theory. Journal of Organisational Transformation & Social Change, 11(1), 50–68. doi:10.1179/1477963313Z.00000000025

- Rhodes, R. A. W. (2018). Control and power in central-local government relations. Routledge.

- Roehrich, J. K., Selviaridis, K., Kalra, J., Van der Valk, W., & Fang, F. (2019). Inter-organizational governance: A review, conceptualisation and extension. Production Planning & Control, (pp.1–17). doi:10.1080/09537287.2019.1647364

- Russell, B. (1938). Power: A new social analysis. 1st ed. UK: Allen & Unwin.

- Russell, S. (2019). The Role of Upward Influence in Organizational Politics: A Discussion on the Effectiveness of Single and Combined Influence Tactics in an Upward Direction.

- Saad, S. M., & Lassila, A. M. (2004). Layout design in fractal organizations. International Journal of Production Research, 42(17), 3529–3550. doi:10.1080/00207540410001721790

- Salancik, G. R., & Pfeffer, J. (1974). The bases and use of power in organizational decision making: The case of a university. Administrative Science Quarterly, 19, 453–473. doi:10.2307/2391803

- Salancik, G. R., Pfeffer, J., & Kelly, J. P. (1978). A contingency model of influence in organizational decision-making. Pacific Sociological Review, 21(2), 239–256. doi:10.2307/1388862

- Sander, L. M. (1986). Fractal growth processes. Nature, 322(6082), 789. doi:10.1038/322789a0

- Scherz, A. (2019). Tying legitimacy to political power: Graded legitimacy standards for international institutions. European Journal of Political Theory, 1474885119838137.

- Simon, H. A. (1957). Models of man. New York: Wiley.

- Sledge, C. L. (2016). Influence, power, and authority: Using millennials’ views to shape leadership practices. Air War College, Air University Maxwell AFB United States.

- Smith, R. C., & Turner, P. K. (1995). A social constructionist reconfiguration of metaphor analysis: An application of “SCMA” to organizational socialization theorizing. Communications Monographs, 62(2), 152–181. doi:10.1080/03637759509376354

- Tohidian, I., & Rahimian, H. (2019). Bringing Morgan’s metaphors in organization contexts: An essay review. Cogent Business & Management, 6(1), 1587808. doi:10.1080/23311975.2019.1587808

- Uphoff, N. (1989). Distinguishing power, authority & legitimacy: Taking Max Weber at his word by using resources-exchange analysis. Polity, 22(2), 295–322. doi:10.2307/3234836

- Van Engen, R. B. (2008). Metaphor: A multifaceted literary device used by Morgan and Weick to describe organizations. Emerging Leadership Journeys, 1(1), 39–51.

- Venkatadri, U., Rardin, R. L., & Montreuil, B. (1997). A design methodology for fractal layout organization. IIE transactions, 29(10), 911–924. doi:10.1080/07408179708966411

- Walsham, G. (1991). Organizational metaphors and information systems research. European Journal of Information Systems, 1(2), 83–94. doi:10.1057/ejis.1991.16

- Weber, M. (1947). The Theory of Social and Economic Organization, trans. A. M. Henderson and T. Parsons. New York: Free Press of Glencoe.

- Weber, M. (1968). Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. New York: Bedminister Press.

- Whetten, D. (1989). What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 490–495. doi:10.5465/amr.1989.4308371

- Wikimedia (2005). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sierpinski_pyramid.png