Abstract

This study aims to examine the determinants of performance-based budgeting (PBB) implementation in higher education institutions (HEIs) in Indonesia and also its impact on HEI quality. The research was conducted in Indonesian private HEIs. Utilising online and direct survey techniques, 153 sets of valid data were successfully collected as the samples. Variant-based partial least squares-structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was employed to assess the research hypotheses. The study reveals that management competence and reward systems have a positive impact on PBB implementation, and that PBB has a positive effect on HEI quality. The study also finds that PBB plays a role as an intervening variable in the relationship between management competence and reward systems in relation to HEI quality.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This study aims to address the phenomenon of the long-standing poor quality of most Indonesian higher education institutions (HEIs). According to various studies, the implementation of performance-based budgeting (PBB) is claimed to be able to enhance organisational performance. In light of this, we attempt to investigate the role of PBB implementation within HEIs. As performance is one of the quality elements of HEIs, we examine whether PBB implementation affects its quality. On the other hand, we also examine the determinants of PBB, i.e. management competence, organisational commitment, and reward systems. The study results reveal that management competence and reward systems have a positive influence on PBB implementation. Moreover, PBB implementation plays a significant role in HEI quality. It is therefore suggested that PBB should be appropriately implemented in HEIs to overcome the poor quality of most Indonesian institutions.

1. Introduction

Competition nowadays no longer only occurs in the business sector but is also experienced in the Higher Education Institution (HEI) sector. External pressures such as competition in labour and education markets have challenged higher education institutions to revisit their organisational structures and internal management approach in order to provide better quality education. Their aim is to sustain their positions within national and global market competition (Gulden et al., Citation2020; Mwiya et al., Citation2019). Currently, the competitive advantage of an HEI, both globally and nationally, is assessed based on its quality and is indicated by their accreditation predicate given by the Accreditation Assessment Institution (Chu & Westerheijden, Citation2018). To encourage HEI quality improvement, many countries have issued regulations relating to new public management (NPM) practices. One of its focuses is to encourage HEIs to apply good university governance (GUG) practices, one of whose elements is performance-based budgeting (PBB).

Previous studies have found that PBB implementation can help organisations to achieve better performance (Crain & O’Roark, Citation2004; Jongbloed & Vossensteyn, Citation2001; Lorenz, Citation2012). The advantage of PBB implementation is that the mechanism is oriented towards the results or outcomes accomplished (Andrews, Citation2002). PBB is able to concretely specify the relationship between organisational goals, targets, programs, activities, and key performance indicators (KPIs) (Rahman et al., Citation2019; Robinson & Last, Citation2009). As such, KPI achievement will lead to the realisation of the organisation’s goals. Since performance is one of the elements of HEI quality (Das & Mukherjee, Citation2017), by adopting PBB it is expected that this quality can be improved.

It is reported that Indonesia has a large number of HEIs, totalling 4,529 in 2019. However, the quality of these, in general, remains poor. Such poor quality indicates the low performance of HEIs. More specifically, the Ministry of Education reported that in 2018 out of the 4,529 Indonesian HEIs, only 1,223 (27.00%) had submitted accreditation assessment at the institutional level, with the following results: 59 (4.82%) were rated “A” (excellent), 441 (36.06%) “B” (good), and 723 (59.12%)Footnote1 “C” (poor) (banpt, 2019). Most of the HEIs that received a C accreditation predicate were private ones. This means that most private HEIs in Indonesia have a low-quality educational process. Quality is a pivotal aspect of HEIs since it is a major concern for HEI management to gain recognition and public trust (Sayidah & Ady, Citation2019). Poor HEI quality will trigger a decline in student numbers as a result of the falling trust amongst prospective students and eventually threaten HEI sustainability (Tsinidou et al., Citation2010). In addition, some academics argue that in the globalisation era, the economic future of all nations depends on their ability to produce a stock of human competence through the quality of their education (Dill, Citation2009; Vnoučková et al., Citation2018).

Considering the positive impact of PBB on performance, this policy is strongly recommended for implementation in order to solve the problems faced by Indonesian private HEIs. As HEI performance is one element of their quality assessment, this indicates that the higher the HEI performance, the higher its quality (Das & Mukherjee, Citation2017). However, until now, empirical studies pertaining to the influence of PBB on HEI quality have been scarce. Apart from the impact of PBB, research on PBB determinants in the HEI sector context have also received little attention. Given that PBB is a new regulation for Indonesian HEIs, in place since 2014, it is essential to investigate its success factors. According to Robbins and Judge (Citation2013) and other scholars (Arifin, Citation2015; Hashim & Wok, Citation2013; Ismail et al., Citation2014), the success of an organisation, especially in adopting new policies, depends on the competence of its human resources. Moreover, Julnes and Holzer (Citation2001) found that to support new regulations implemented by organisations, a reward system is needed for the new policy to run effectively (Libby & Thorne, Citation2009; Naranjo-Gil et al., Citation2012). In addition to these two determinants, to achieve success in budgeting implementation policy, organisational commitment from management members is also vital (Murwaningsari, Citation2008; Mustofa, Citation2015; Yılmaz et al., Citation2014). Developing these arguments, this study aims to examine three determinants of PBB implementation, namely management competence, organisational commitment, and reward systems, and also to examine the impact of PBB implementation on HEI quality.

The results of the study extend the body of knowledge, primarily that related to empirical studies of PBB issues in the HEI sector, particularly in the developing country context. Many PBB studies have indeed been conducted. However, most were undertaken in developed country contexts, such as the US (Lu et al., Citation2011); the UK (Noman, Citation2008); Australia and New Zealand (Martí, Citation2013); and western European countries (Jones et al., Citation2013; Kuhlmann, Citation2010; Lorenz, Citation2012). In addition, previous studies have also mostly focused on the for-profit organisation (FPO) and governmental organisation sectors, rather than not-for-profit organisations (NFPOs), such as HEIs.

2. Literature review

2.1. New public management in Indonesian HEIs

New Public Management (NPM) is a new pattern in the development of public sector management, which refers to the principles of good governance, with emphasis on strategic vision, democracy, fairness, transparency, responsiveness, the rule of law, participation, equality, and accountability (Osborne & Gaebler, Citation1993). One of the implementations of NPM in Indonesian HEIs has been by the adopting a new modern budgeting system, which introduces several methods, namely zero-based budgeting (ZBB), the planning programming budgeting system (PPBS), and performance-based budgeting (PBB) (Hager et al., Citation2001).

Modern budgeting has replaced traditional budgeting, which had several weaknesses. Hager et al. (Citation2001, p. 62) define performance-based budgeting as a “budgeting method that links appropriation ultimately to the outcome of the program.” Hence, PBB is more focused on achieving the results or performance of the planned activity costs (Hager et al., Citation2001). It is important to note that the performance of HEIs must reflect the efficiency and effectiveness of public services, which means they must be oriented to society’s interests (Berry & Flowers, Citation1999; Sofyani, Citation2018). As the main objective of HEIs is to provide good quality education, PBB should be directed to meet these expectations, which are related to the improvement of HEI quality (Dicker et al., Citation2019; Jongbloed & Vossensteyn, Citation2001; Mourad, Citation2017; Pham & Starkey, Citation2016). Although studies related to university governance have been undertaken using various approaches and backgrounds, most have centred their discussion more on the historical, political, and principle aspects, rather than on how the governance changes in HEIs are related to quality improvement (Kretek et al., Citation2013; Trakman, Citation2008; Wardhani et al., Citation2019). Therefore, this research attempts to fill this gap by combining the two issues in one study. Specifically, it examines the influence of PBB implementation as HEI governance changes towards HEI quality.

2.2. Theoretical underpinning

The study employs goal-setting theory to explain the relationship between PBB implementation and HEI quality. Locke (Citation1975) contends that goals which are clearly defined and realised by individuals or groups within the organisation, will result in higher levels of achievement if they are accompanied by general acceptance (Basri, Citation2013). Locke details that there are five principles in goal-setting: (1) the goals must be clear; (2) they must have a medium to a high level of difficulty; (3) organisation members must accept the goals; (4) members must receive feedback regarding their progress in attempting to achieve the goals; and (5) objectives that are determined in a participatory manner are better than goals that are set by only one party. Locke and Latham (Citation2013) suggest that the existence of clear goals and objectives can mitigate confusion, ambiguity, and a lack of direction amongst subordinates.

Every goal set by organisations is formulated in their budget plan in order to make it easier for teams to achieve their performance targets, which are in accordance with their organisation’s vision and mission. A budget does not only contain plans and nominal amounts needed to conduct activities or programs, but it also comprises the goals to be achieved (Jones & Pendlebury, Citation2010). In practice, PBB results detail the target outputs and outcomes of planned activities and budgets, execution terms, and evaluation schedules. These activities are closely related, as explained by the goal-setting concept. This is consistent with the premise of goal-setting theory, which claims that difficult goals, but with specific targets, will result in high performance (Robbins & Judge, Citation2008). As such, PBB implementation is believed to be able to help management to achieve the performance targets that have been set (Locke & Latham, Citation2013).

Furthermore, this study also employs a new institutional theory to explain the PBB implementation determinants, namely management competence and organisational commitment. Notably, the study espouses the viewpoint of the institutional isomorphism mechanism proposed by DiMaggio and Powell (Citation2000). They argue that when reaching an established level, organisations tend to move towards uniformity; in this case, the adoption of PBB within HEI (Kristiantoro et al., Citation2017). Many scholars use “isomorphism” as the best term to describe the process of such “uniformity.” Moreover, DiMaggio and Powell (Citation2000) suggest three different mechanisms of institutional isomorphism: coercive, mimetic, and normative. Coercive isomorphism occurs as a result of pressures exerted by either external or higher internal parties on an organisation. Meanwhile, mimetic isomorphism takes place when organisations imitate other organisations that are perceived as having a successful track record after adopting a specific policy or mechanism. Finally, normative isomorphism describes organisations that naturally conform to the context of their industry through regular business practice. One of the prominent sources of normative isomorphism is formal education in the cognitive skills of the professionals produced by university (DiMaggio and Powell, Citation2000). Additionally, normative isomorphism also originates from strong organisational commitment by it members (Sofyani & Akbar, Citation2013).

In addition to both theories above, goal-setting and new institutional, this study also applies expectancy theory to elucidate the relationship between reward, and the implementation of PBB and HEI quality. Based on expectancy theory promoted by Vroom (Citation1964), management behaviour is related to the implementation of policy in the organisation, and also to the effort to achieve performance, which depends on the expectations of each member in the organisation. Vroom states that individuals work to meet the expectations of their job. In actual practice, expectancy theory is manifested in the form of reward systems that are linked to specific policies to achieve organisational performance targets, in this case PBB. Therefore, managers will expend a certain level of effort if they feel that there is a strong relationship between the effort they make and the reward that will be received. This argument is in line with Lunenburg (Citation2011), who claims that there is a close relationship between the effort made and the performance realised if an organisation operates a specific reward policy.

2.3. Management competence and PBB implementation

Competence includes the knowledge, skills, action or behaviour, and mindset that reliably distinguishes between individuals, especially in relation to job performance (Hashim & Wok, Citation2013; Meister, Citation1998). The success of policy implementation within an organisation is determined by the competence of its members, especially managements (Noe et al., Citation2017). The competence gained from formal education and long experience is one of the crucial sources of policy institutionalisation, in this case PBB (Ahyaruddin & Akbar, Citation2018; Akbar et al., Citation2015; Beckert, Citation2010). The knowledge and skills of competent management will enable them to work effectively and minimize. Various studies explain that management competence is an essential component in budget preparation and implementation, because management is always involved in goal setting and evaluation (Pratolo & Jatmiko, Citation2017). Based on the points made above, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H1: Management competence has a positive influence on PBB implementation.

2.4. Organisational commitment and PBB implementation

Bansal et al. (Citation2004) define commitment as a force that binds the individual to actions that have relevance to the goals of the organisation. In particular, organisational commitment from management is a pivotal aspect in the process of designing, implementing, and using PBB. Management who have a strong sense of responsibility towards their organisation will tend to apply PBB well and firmly in a goal-oriented way. Sofyani and Akbar (Citation2013) argue that commitment can be reflected in activities such as allocating resources; goals; strategies for various plans that are considered valuable; rejecting resources that impede innovation; and providing the political support needed to motivate individuals to achieve their goals. Therefore, strong commitment will greatly affect organisations in terms of the implementation of policies related to performance improvement (Tahar & Sofyani, Citation2020). Cavalluzzo and Ittner (Citation2004) found that organisational commitment from management played a vital role in developing organisational policies related to efforts to achieve performance. Based on the points made above, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H2: Organisational commitment has a positive influence on PBB implementation.

2.5. Reward system and PBB implementation

Julnes and Holzer (Citation2001) suggest that organisational responses to change are also related to the existence of incentives as a form of compensation for accepting innovation. Such compensation exists as a prerequisite for the implementation of new policies because the members of the organisation may judge that innovation does not always have a positive impact, instead having a negative effect if the new concepts introduced into the organisation fail to be adequately implemented. Simons (Citation2000) contends that, in general, there are two ways to encourage employees to work in accordance with organisational goals: first, by ensuring that they believe that the goals are legitimate, so they make an effort to achieve them; and second, by directing employees’ attention to the goals to be achieved through formal incentives in the form of rewards or payments, with the expectation of motivating performance. In addition, according to expectancy theory, Lunenburg (Citation2011) argues that organisation members will try to achieve a specific target if they expect a reward for doing so. Kadarisman (Citation2012) details that rewards benefit organisations by (1) attracting employees with a high level of ability to work in the organisation; (2) providing stimulation so that employees work towards making high accomplishments; and (3) binding employees into remaining with the organisation. Therefore, the presence of PBB as a part of the NPM adopted by HEIs will operate effectively if its implementation is accompanied by a reward system. Based on the points made above, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H3: Reward systems have a positive influence on PBB implementation.

2.6. PBB implementation and HEI quality

A well-prepared budget plays a role in planning execution guidance and in directing performance. In addition, it can be is employed as a control system for measuring managerial performance (Jones et al., Citation2013; Jones & Pendlebury, Citation2010). Based on the standpoint of goal-setting theory, the existence of clear outcome targets resulting from PBB implementation is expected to help organisations to achieve better work performance as employees will be aware of performance targets (Locke, Citation1975). HEI employees will be better able to work according to plan if the targets to be achieved have been formulated clearly and structured. Kaplan et al. (Citation2010) claim that clear targets within an organisation, such as KPIs, which result from PBB implementation, allow leaders to align the actions of their organisation’s members in achieving shared organisational goals. With clear performance targets, subordinates (employees) will understand their roles and responsibilities and know what needs to be accomplished according to the plans and strategies that have been set (Kimunguyi et al., Citation2015; Lorenz, Citation2012). Because HEI performance is an element of HEI quality itself, the implementation of PBB is assumed to have a positive impact on achieving such quality (Crain & O’Roark, Citation2004; Jongbloed & Vossensteyn, Citation2001; Lorenz, Citation2012). Based on the points made above, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H4: PBB implementation has a positive influence on HEI quality.

2.7. Management competence, PBB, and HEI quality

The success of an organisation in reaching its goals is largely determined by the quality and capabilities of its human resources (employees). However, organisational employee behaviour can be motivated by budgeting systems so that goal congruence within an organisation can be realised (Cugueró-Escofet & Rosanas, Citation2013). The budget system is more than just an instrument that assists management in planning and control (Joshi et al., Citation2003). It has a very wide scope, with extensive research still being devoted to understanding how it works (Hansen & Van der Stede, Citation2004). Budgets constitute a mechanism that can be utilised to coordinate the various parts of an organisation, to control and measure employee performance, to motivate personnel, and to improve communication (Fisher et al., Citation2002).

HEIs are organisations that consist of academics, human resources, assets, and financial systems. Part of the financial system are budgeting systems which, although a small part of the sub-systems in HEIs, play a prominent role in supporting their quality. Since the success of budgeting system implementation is dependent on management competence, there is a sequence that a process through which the quality of human resources will influence HEI performance through PBB, which plays a role as control mechanism. This indicates that there is an indirect relationship between management competence and HEI quality through PBB implementation. Based on the points made above, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H5: PBB mediates the influence of management competence on HEI quality.

2.8. Organisational commitment, PBB, and HEI quality

Many previous studies have found that organisational commitment is one of the vital aspects of achieving better performance (Balfour & Wechsler, Citation1991; Shaw et al., Citation2003; Suliman & Al Kathairi, Citation2013). However, employee commitment alone is not sufficient as a determinant of organisational performance if the system that runs in the organisation itself is poorly structured and lacks specific supporting policies. As PBB implementation plays a role as control mechanism within the organisation, individual and organisational goals can run in harmony (Joshi et al., Citation2003; Kimunguyi et al., Citation2015). PBB implementation also acts as a guide to the performance targets that must be attained (Lee & Wang, Citation2009). This mechanism will clarify organisational goals, helping members to achieve them (Locke & Latham, Citation2013; Locke et al., Citation1981). From this argument, it can be concluded that organisational commitment will have an effect on HEI performance, which in turn will improve HEI quality if accompanied by the implementation of PBB within them. Based on the points made above, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H6: PBB mediates the influence of organisational commitment on HEI quality.

2.9. Reward systems, PBB, and HEI quality

Essentially, reward systems are needed to encourage employees to improve the quality and performance of their work (Carrigan, Citation2011). As HEI quality is defined by employee performance, such systems influence this quality. However, referring to expectancy theory, the presence of rewards must be linked to the clarity of the goals and objectives of the organisation (Vroom, Citation1964). Accordingly, this concept is related to the implementation of PBB, which provides details of the priority scale of the objectives and outcomes to be achieved, the targets to be met, programs, and activities that must be performed (Locke & Latham, Citation2013; Robinson & Last, Citation2009). When all these details are associated with a reward system, calculation can be made of the possibility of meeting performance targets in relation to the rewards expected by employees (Lunenburg, Citation2011). This calculation will motivation employees to strive to achieve the set performance targets, because as rational human beings, they will make an effort to meet their expectations based on the rewards provided. This therefore indicates that reward systems will affect HEI quality through PBB implementation. Based on the points made above, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H7: PBB mediates the influence of reward systems on HEI quality.

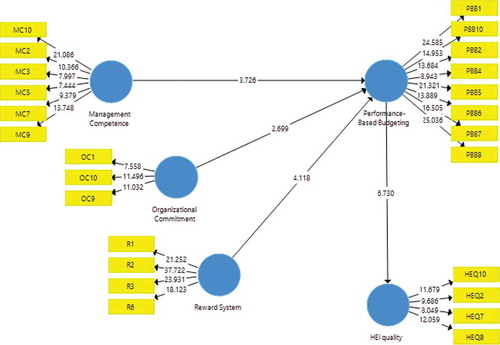

The study research model is shown in Figure .

3. Research methodology

3.1. Population, unit of analysis and sample

The research employed a positivist paradigm and was conducted with the survey method approach. It used an explanatory research model that proposed investigation of how one variable influences the other variables (Cooper & Schindler, Citation2001; Creswell, Citation2012; Hartono, Citation2013). We chose private HEIs as the research subject because most of them had received a “C” (poor) accreditation predicate, which indicates that the quality of their education process was poor. However, they have started to implement PBB to improve their quality. Hence, this research aims to investigate whether such a policy is relevant to resolve the poor quality problem experienced by private HEIs in Indonesia. The unit of analysis of the study is the organisation. The sample was selected randomly, since all private HEIs had the same possibility to be involved. However, we excluded vocational HEIs, as their quality assessment is different. The number of samples was determined by referring to the sample size table formulated by Krejcie and Morgan (Citation1970). As the population of Indonesian non-vocational private HEIs is 2,056, the minimum sample size should be 322.

3.2. Type, source, and data collection technique

Primary data were used in the study, obtained directly from the respondents using a questionnaire. We distributed 500 questionnaires; 60% online (email) and 40% by direct distribution. However, out of these 500, only 153, or 30.6%, were returned completely filled in. Most of the questionnaires that were not completed were ones sent online. Although the collected sample size did not reach ideal number (322), the percentage was considered acceptable when compared to similar survey research with the organisation as the unit of analysis. Generally, survey research only has a response rate in the range of 10–20% of the minimum required sample (Fowler, Citation2013). The rate was higher than that achieved by Alach (Citation2017), who had a 12% response rate in his study of the performance measurement system in New Zealand universities. Bobe and Kober (Citation2018) had a 28.3% response rate, with only 56 usable questionnaires, in their study of management control systems in Australian universities. Compared to these studies highlighted, the response rate of our study was acceptable. The research respondents were the parties involved in the implementation of PBB within HEIs, including rectors, vice-rectors, deans, heads of department, and HEI financial staff.

3.3. Variables and measurements

The study utilised three exogenous variables, namely management competence, reward systems, and organisational commitment, and one endogenous variable, HEI quality. PBB was applied as an endogenous and exogenous variable because of its role, which was also as an intervening variable. To measure the responses, a 1–5 Likert scale was employed, on which 1 indicated “strongly disagree” and 5 “strongly agree.” In this research, management competence refers to the ability to perform its tasks. This variable was measured based on educational background, training, task understanding, readiness to commit to achieving performance, and coordination ability. The construct development referred to Sandberg (Citation1996) and Liu et al. (Citation2005). The reward system variable was gauged based on the existence of the following policies: promotion, awards, financial incentives, praise, and warnings (negative reward). The measure was developed with reference to Agwu (Citation2013), Chenhall and Langfield-Smith (Citation2003), and Coates et al. (Citation1995).

Furthermore, the organisational commitment variable was determined based on three indicators: continuous commitment, normative commitment, and affective commitment. The instrument was adapted from Camilleri and Van Der Heijden (Citation2007). Moreover, the PBB implementation variable referred to one of the modern budgeting approaches, which are systematic approaches to budgeting in public sector organisations, formulated on specific performance and outcome targets and which aim to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of public spending. This variable was evaluated using a questionnaire adapted from Sofyani (Citation2018). The PBB construct consisted five indicators, namely the determination of the strategic plan; the strategic plan in the work plan; the setting of performance indicators; the use of standard cost analysis in budgeting; and performance evaluation. Finally, HEI quality was calculated based on accreditation indicators regulated by the Indonesian government. Before the questionnaire was employed to collect the data, we involved two experts from the accounting discipline to validate it. They were asked whether the questionnaire was easy to read and understand, and whether it was demanding or confusing. Once the feedback was obtained, minor revisions were made for improvement.

3.4. Data analysis method

In the study, the variant-based partial least squares-structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) method was used to analyse the data and examine the hypotheses. This method is able to simultaneously perform measurement model tests while testing structural models (Chin et al., Citation2003; Hair et al., Citation2014). Two reasons for utilising PLS were the non-parametric nature of the Likert scale and the magnitude of the possible elements of multicollinearity. Moreover, following various scholars (Akbar et al., Citation2012; Sofyani et al., Citation2020), PLS was deemed suitable for this research as it allows for minimal data assumptions and requires a relatively small sample size (Chin et al., Citation2003). According to Hair et al. (Citation2010), the minimum sample size for PLS analysis is the “10 times rule”, meaning that it should be greater than 10 times the maximum number of inner or outer model links pointing to any latent variable in the model. As higher education quality is a latent variable with a maximum number of indicators pointing to it of 11, the minimum sample size according to Hair et al. (Citation2010) should be 110 (10 x 11). Given that the sample collected for the study is 152, then this assumption has been fulfilled.

3.5. Results

3.5.1. Construct validity test results

The construct validity test aims to evaluate how well the results obtained from the use of the measure fit the theories around which the test is designed (Sekaran & Bougie, Citation2010). In conducting the test, we referred to loading and cross-loading values to evaluate whether or not there was any problem. As recommended by Hair et al. (Citation2010), we employed 0.5 as a rule of thumb. In the first evaluation, we found that several construct scores did not meet the rule of thumb required. We therefore dropped them, namely MC1, 4, 6 and 8; OC2, 3, 5, 6, 7 and 8; MC11; PBB3; and HEQ1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9 and 11. We also dropped R4 and 5 and PBB 9 due to multi-collinearity problems, which were indicated by VIF scores higher than 0.10. Having dropped them, we re-tested the data and found that all the items measuring a particular construct loaded highly on that construct and but lower on the other constructs, thus confirming construct validity (See Table ) (Hair et al., Citation2010).

Table 1. Loadings and cross-loadings

3.5.2. Convergent validity test results

In the next step, we evaluated the convergent validity, which is the degree to which multiple items measuring the same concept are in agreement. Referring to Hair et al. (Citation2010), we used factor loading and average variance extracted (AVE) to test for this. In Table , it can be seen that the loading values for all items were higher than the recommended score of 0.5 (Hair et al., Citation2010). It also can be seen that all items showed AVE values that met the rule of thumb required, being higher than 0.5 (Barclay et al., Citation1995; Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981).

Table 2. Results of the measurement model

3.5.3. Discriminant validity test results

The discriminant validity of the measures indicates the degree to which items are differentiated among the constructs or measure distinct concepts. We assessed this by observing the correlations between the measures of potentially overlapping constructs. Items should load more strongly on their constructs in the model, the average variance should be shared between each construct, and their measures should be higher than the variance shared between the construct and other constructs (Compeau et al., Citation1999). From Table , it can be seen that the correlation score of the construct to the construct itself is higher than to other constructs. These results conclude that discriminant validity was met (Gefen & Straub, Citation2005).

Table 3. Discriminant validity scores

3.5.4. Reliability test results

To assess the inter-item consistency of our measurement items, Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability were employed. From Table , it can be seen that all the alpha values are higher than the required 0.6 (Chin et al., Citation2003), and the composite reliability values range from 0.647 to 0.892. Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) argue that a composite reliability value of 0.50 or higher is considered acceptable. Hence, it can be concluded that the measurements in this research were reliable.

Table 4. Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability scores

On the other hand, due to self-reported nature of the research data, there was a potential for common method variance (CMV). For this reason, the Harman one-factor test was conducted to determine the extent of this. According to Podsakoff and Organ (Citation1986), common method bias is problematic if a single latent factor would account for the majority of any explained variance that is more than 50%. On the other hand, Fuller et al. (Citation2016) suggest that the score should not exceed 40%. Based on the CMV test results, the unrotated factor analysis showed that the first factor accounted for only 17.61% of the variance (see also Doty & Glick, Citation1998; Tehseen et al., Citation2017).

3.5.5. Hypothesis testing results

The results of the hypothesis testing are shown in Figure and Table . The hypothesis is supported if its t-value is higher than 1.96 or significant at a p-value of 0.05. Based on the path analysis test, it was found that all the hypotheses proposed were supported at the level of significance of 0.01 (Table ). In addition, Table shows the R-squared, f-squared and Q-squared values. According to Chin (Citation1998), the value of R-squared is said to be strong if its value is higher than 0.67, moderate if it is higher than 0.33, and weak if the value is lower than 0.19. Hence, the R-squared of HEQ was weak, whilst that of PBB was moderate. However, the f-squared score indicates that the effect of the latent variable predictor (the exogenous latent variable) at the structural level is strong, namely above 0.35. Moreover, the Q-squared values obtained are 0.316 (HEQ) and 0.361 (PBB) (above 0), meaning the structural model obtained has a prediction of relevance prediction.

Table 5. Hypothesis test results summary

Table 6. R-squared, f-squared and Q-squared value

3.5.6. Additional analysis

We conducted a G*power test to ascertain whether the study sample was sufficient to provide strong generalisation results. This was done to justify the minimum number of samples from a statistical point of view, in addition to the methodological point of view presented in the methodology section above. This calculation is based on a significance of at least 0.05 and a minimum power of 0.80 (Faul et al., Citation2009).

G*power testing was performed by calculating the effect size of PBB and HEQ seen from the R-squared data of 0.361 and 0.316, respectively. The results of the G*power calculations show that the sample size for PBB as an independent variable requires a minimum of 43 samples, while HEQ as an independent variable requires a minimum of 58 samples. Because our sample size was 153, it can be concluded that the minimum size required has been met (Faul et al., Citation2007).

4. Discussion

The study confirms goal-setting theory, as can be seen from the acceptance of H4. PBB implementation, which could provide clear information about HEI targets, positively influences HEI quality. This is in line with the findings of Jongbloed and Vossensteyn (Citation2001). As stated in the hypothesis development section, PBB implementation is not only a tool for planning annual organisational activities. It is also a modern budgeting method, acting as a strategic tool that is useful for controlling the ultimate goals of the activities undertaken in accordance with the HEI’s vision, mission, and objectives. Moreover, PBB is also a strategic tool that can align individual goals with the goals of the organisation (Jones et al., Citation2013; Jones & Pendlebury, Citation2010). This indicates that it can be directed as a medium to create conformity of goals within HEIs (Cugueró-Escofet & Rosanas, Citation2013). This is supported by the research findings, which show that reward systems, which act as a policy to encourage employees’ work motivation, can affect HEI quality when combined with PBB implementation. Although it only serves as a quasi-intervening, the role of PBB implementation remains important to consider, given its relative influence on HEI quality. This research also discovered that PBB implementation acted as a quasi-intervening in the relationship between management competence and HEI quality. Management competence in running HEIs is needed so that the organisation’s journey is in accordance with its vision, mission, and goals, as well as in managing quality. However, when this is coupled with PBB implementation, it will add value because PBB can direct management competencies according to work priorities.

The study also found that management competence, organisational commitment, and reward systems were vital factors that influenced PBB implementation. The research confirms the “new” institutional theory, primarily the point of view of the normative mechanism of institutional isomorphism. According to DiMaggio and Powell (Citation2000), one of the patterns of institutionalisation within an organisation is a normative isomorphism, in which the organisation seeks to implement a certain organisational structure or specific policy mechanisms with a foundation of professionalism for a substantial orientation, namely optimal achievement of goals (Ahyaruddin & Akbar, Citation2018; Akbar et al., Citation2015; Frumkin & Galaskiewicz, Citation2004; Meyer & Rowan, Citation1977; Sofyani et al., Citation2018). One of the key factors in attaining optimal goals is the competence and commitment of management within the organisation. However, it is a fact that PBB implementation remains uneven in all Indonesian HEIs, particularly private ones. This could be due to the lack of competence amongst HEI management, so the intention to implement the NPM concept is not strong. This is in line with the fact that in most Indonesian HEIs, public and private, management positions are political. Accordingly, the efforts to gain power predominate over management professionalism in guiding organisational improvement (Cahyono et al., Citation2001). This situation results in the fact that HEI management members do not necessarily have adequate competence to manage their institutions. However, they still clearly have a strong support, enabling them reach strategic positions in HEI management. Therefore, this finding indicates the practical implication that it is vital for HEIs to employ people as managers with sufficient competence.

Furthermore, the research also confirms expectancy theory (Vroom, Citation1964) and supports the notion that the reward mechanism is also one of the prominent determinants of PBB implementation. This finding is in accordance with Julnes and Holzer (Citation2001), who argue that the application of innovation in organisations, in this case PBB adoption, needs to be accompanied by incentives as a trade-off, so that organisation members will be willing to undertake the innovation appropriately. This is because innovation can frustrate employees, who may have lost the rhythm of the status quo in which they felt comfortable (Akbar et al., Citation2012). This is supported by the fact that in the field many academics, mainly those who are not from the disciplines of accounting, finance or management, perceive that the focus of HEIs should be on providing quality education, not improving financial performance (Finkelstein et al., Citation1996; Naranjo-Gil & Hartmann, Citation2006, Citation2007). This assumption is reasonable because of their limited understanding, so they only view PBB implementation as a process of planning and determining budgets, rather than as a strategic tool to enhance HEI performance and eventually HEI quality. Therefore, when rewards are formulated and linked to performance targets, employees will strive to achieve these targets, which are inherently embedded in PBB.

5. Conclusion and practical implications

The study has aimed to examine the determinants of PBB, namely management competence, organisational commitment, and reward systems, and also the impact of PBB implementation on HEI quality. In total, 153 private HEIs were involved in the research as samples. The respondents were represented by HEI management members, such as rectors, vice-rectors, deans, heads of department, and HEI financial staff. The study found that the three determinants positively influenced PBB implementation. Moreover, PBB implementation had a positive impact on HEI quality. It was also found that PBB played an intervening role in the relationship between management competence, organisational commitment and reward systems, and HEI quality.

The study makes essential practical and theoretical contributions to the field of knowledge. Practically, it is vital to implement PBB in HEIs, since it is one of the potential factors able to improve HEI quality, hence helping to alleviate the problem of poor HEI quality in Indonesia. In addition, for successful PBB implementation, HEIs need to consider the competence and organisational commitment of management at all levels. Because the application of PBB requires specific knowledge, especially related to financial management and accounting, managers must be trained to improve their related competencies. Likewise, reward systems should be a fundamental part of PBB policy for them to run effectively. Moreover, in terms of theory, the study results provide insights to now lacking into the determinants and consequences of PBB implementation in the HEI sector. Finally, the study confirms goal setting, new institutional, and expectancy theories, in particular related to PBB implementation in the HEI sector study context, which have also had limited coverage in the literature.

6. Limitations and recommendations

Apart from its positive implications, the study does of course have some limitations. First, it was only conducted in private HEIs in Indonesia, with most of the samples from Java and Sumatra. However, Indonesia is a big country with many other regions and islands. Hence, readers should take care when drawing conclusions from the research results, especially for generalisation purposes. Given this point, future research should be undertaken in other regions and involving public HEIs. It is also suggested that all the islands in Indonesia should if possible be covered to acquire better study results. Second, the research only tested three determinants of PBB implementation. Further research could involve the political element, pressure from the ministry of Higher Education, and the aspect of legitimacy as additional determinants of PBB implementation. Third, the research only links the impact of PBB implementation on HEI quality, whereas there is the possibility that PBB could also contribute to the sustainability of HEIs in other ways. Finally, other theoretical points of view, such as managerial hegemony, agency, and stewardship, could be considered in subsequent investigations regarding PBB implementation in HEIs.

correction

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Suryo Pratolo

Suryo Pratolo is an Associate Professor and researcher in the Department of Accounting, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Indonesia. He is also Vice-Rector for Financial and Asset Management. His research interests include public sector accounting.

Hafiez Sofyani

Hafiez Sofyani is a lecturer and researcher in the Department of Accounting, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Indonesia. He is Editor in Chief of the Journal of Accounting and Investment. His research interests encompass public sector accounting, e-government, e-governance, and good governance.

Misbahul Anwar

Misbahul Anwar is a lecturer in the Department of Management, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Indonesia. He is Head of UMY Islamic Microfinance Institutions (BMT UMY), and his research interests include marketing strategy and consumer behavior.

Notes

1. The percentages are calculated based on all the HEIs that submitted accreditation assessment.

References

- Agwu, M. (2013). Impact of fair reward system on employees job performance in Nigerian agip oil company limited port-harcourt. Journal of Education, Society and Behavioural Science, 3(1), 47–22. https://doi.org/10.9734/bjesbs/2013/2529

- Ahyaruddin, M., & Akbar, R. (2018). Indonesian local government’s accountability and performance: The isomorphism institutional perspective. Journal of Accounting and Investment, 19(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.18196/jai.190187

- Akbar, R., Pilcher, R., & Perrin, B. (2012). Performance measurement in Indonesia: The case of local government. Pacific Accounting Review, 24(3), 262–291. https://doi.org/10.1108/01140581211283878

- Akbar, R., Pilcher, R. A., & Perrin, B. (2015). Implementing performance measurement systems: Indonesian local government under pressure. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 12(1), 3–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRAM-03-2013-0013

- Alach, Z. (2017). The use of performance measurement in universities. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 30(2), 102–117. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-05-2016-0089

- Andrews, M. (2002). Performance-based budgeting reform: Progress problems and pointers (Vol. 1) Handbook on Public Sector Performance Reviews. Washington D.C.: The World Bank.

- Arifin, H. M. (2015). The influence of competence, motivation, and organisational culture to high school teacher job satisfaction and performance. International Education Studies, 8(1), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v8n1p38

- Balfour, D. L., & Wechsler, B. (1991). Commitment, performance, and productivity in public organizations. Public Productivity & Management Review, 14(4), 355–367. https://doi.org/10.2307/3380952

- Bansal, H. S., Irving, P. G., & Taylor, S. F. (2004). A three-component model of customer to service providers. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(3), 234–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070304263332

- Barclay, D., Higgins, C. A., & Thompson, R. (1995). The partial least squares approach to causal modeling: Personal computer adoption and use as an illustration. Technology Studies: Special Issue on Research Methodology, 2(2), 284–324. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?cluster=10934427946688273356&hl=en&oi=scholarr

- Basri, Y. M. (2013). Mediasi Konflik Peran dan Keadilan Prosedural dalam Hubungan Pengukuran Kinerja Dengan Kinerja Manajerial. Jurnal Akuntansi Dan Keuangan Indonesia, 10(2), 225–242. https://doi.org/10.21002/jaki.2013.12

- Beckert, J. (2010). Institutional isomorphism revisited: Convergence and divergence in institutional change. Sociological Theory, 28(2), 150–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9558.2010.01369.x

- Berry, F. S., & Flowers, G. (1999). Public entrepreneurs in the policy process: Performance-based budgeting reform in Florida. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 11(4), 578–617. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBAFM-11-04-1999-B005

- Bobe, B. J., & Kober, R. (2018). University dean personal characteristics and use of management control systems and performance measures. Studies in Higher Education, 45(2), 235–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1504911

- Cahyono, D., Mulyono, A., & Lesmana, S. (2001). Pengaruh Politik dan Gaya Kepemimpinan terhadap Keefektifan Anggaran Partisipatif dalam Peningkatan Kinerja Manajerial (Studi Empiris di Perguruan Tinggi Swasta). Jurnal Bisnis Dan Akuntansi, 3(3), 543–564. http://jurnaltsm.id/index.php/JBA/article/view/531

- Camilleri, E., & Van Der Heijden, B. I. (2007). Organizational commitment, public service motivation, and performance within the public sector. Public Performance & Management Review, 31(2), 241–274. https://doi.org/10.2753/PMR1530-9576310205

- Carrigan, M. D. (2011). Motivation in public sector unionized organizations. Journal of Business & Economics Research (JBER), 9(1), 55–62. https://doi.org/10.19030/jber.v9i1.940

- Cavalluzzo, K. S., & Ittner, C. D. (2004). Implementing performance measurement innovations: Evidence from government. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29(3), 243–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-3682(03)00013-8

- Chenhall, R. H., & Langfield-Smith, K. (2003). Performance measurement and reward systems, trust, and strategic change. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 15(1), 117–143. https://doi.org/10.2308/jmar.2003.15.1.117

- Chin, W. W. (1998). Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Quarterly, 22(1), 7-16. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/249674.pdf?casa_token=Rh4Jb88a5W4AAAAA:8OHyWBJMvfILXCey5ISpqWFyCq6qk-A9howwXQPHSunvOBtrh4NlA4KldXz_189klTS8yYBuyu3IR05jQT2nXxLmkdh2dZ5lnRvx4S6jDPwI0jaJ3vX_

- Chin, W. W., Marcolin, B. L., & Newsted, P. R. (2003). A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Information Systems Research, 14(2), 189–217. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.14.2.189.16018

- Chu, A., & Westerheijden, D. F. (2018). Between quality and control: What can we learn from higher education quality assurance policy in the Netherlands. Quality in Higher Education, 24(3), 260–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2018.1559513

- Coates, J., Davis, T., & Stacey, R. (1995). Performance measurement systems, incentive reward schemes and short-termism in multinational companies: A note. Management Accounting Research, 6(2), 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1006/mare.1995.1007

- Compeau, D., Higgins, C. A., & Huff, S. (1999). Social cognitive theory and individual reactions to computing technology: A longitudinal study. MIS Quarterly, 23(2), 145–158. https://doi.org/10.2307/249749

- Cooper, D., & Schindler, P. (2001). Business research method. McGraw Hill International Edition.

- Crain, W. M., & O’Roark, J. B. (2004). The impact of performance-based budgeting on state fiscal performance. Economics of Governance, 5(2), 167–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-003-0062-6

- Creswell, J. W. (2012). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. Sage Publication.

- Cugueró-Escofet, N., & Rosanas, J. M. (2013). The just design and use of management control systems as requirements for goal congruence. Management Accounting Research, 24(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2012.11.001

- Das, P., & Mukherjee, S. (2017). Improvement in higher education quality of the North-East University of India. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 28(7–8), 765–781. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2015.1123614

- Dicker, R., Garcia, M., Kelly, A., & Mulrooney, H. (2019). What does ‘quality’in higher education mean? Perceptions of staff, students and employers. Studies in Higher Education, 44(8), 1425–1441. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1445987

- Dill, D. D. (2009). Convergence and diversity: The role and influence of university rankings University rankings, diversity, and the new landscape of higher education. Brill Sense.

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (2000). The iron cage revisited institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields Economics meets sociology in strategic management. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Doty, D. H., & Glick, W. H. (1998). Common methods bias: Does common methods variance really bias results? Organizational Research Methods, 1(4), 374–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442819814002

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

- Finkelstein, S., Hambrick, D., & Cannella, A. A. (1996). Strategic leadership. West Educational Publishing.

- Fisher, J. G., Maines, L. A., Peffer, S. A., & Sprinkle, G. B. (2002). Using budgets for performance evaluation: Effects of resource allocation and horizontal information asymmetry on budget proposals, budget slack, and performance. The Accounting Review, 77(4), 847–865. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2002.77.4.847

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Fowler, F. J., Jr. (2013). Survey research methods. Sage publications.

- Frumkin, P., & Galaskiewicz, J. (2004). Institutional isomorphism and public sector organizations. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 14(3), 283–307. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muh028

- Fuller, C. M., Simmering, M. J., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y., & Babin, B. J. (2016). Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3192–3198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.008

- Gefen, D., & Straub, D. (2005). A practical guide to factorial validity using PLS-Graph: Tutorial and annotated example. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 16(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.01605

- Gulden, M., Saltanat, K., Raigul, D., Dauren, T., & Assel, A. (2020). Quality management of higher education: Innovation approach from perspectives of institutionalism. An exploratory literature review. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1749217. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1749217

- Hager, G., Hobson, A., & Wilson, G. (2001). Performance-based budgeting: Concepts and examples. Legislative Research Commission, Committee for Pram Review and Investigations.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2010). Multivariate data analysis. Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) an emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

- Hansen, S. C., & Van der Stede, W. A. (2004). Multiple facets of budgeting: An exploratory analysis. Management Accounting Research, 15(4), 415–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2004.08.001

- Hartono, J. (2013). Guidance for survey study with questionnaire. BPFE Yogyakar.

- Hashim, J., & Wok, S. (2013). Competence, performance and trainability of older workers of higher educational institutions in Malaysia. Employee Relations, 36(1), 82–106. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-04-2012-0031

- Ismail, M. D., Domil, A. K. A., & Isa, A. M. (2014). Managerial competence, relationship quality and competitive advantage among SME exporters. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 115(1), 138–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.02.422

- Jones, R., Lande, E., Lüder, K., & Portal, M. (2013). A comparison of budgeting and accounting reforms in the national governments of France, Germany, the UK and the US. Financial Accountability & Management, 29(4), 419–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12022

- Jones, R., & Pendlebury, M. (2010). Public sector accounting. Prentice Hall.

- Jongbloed, B., & Vossensteyn, H. (2001). Keeping up performances: An international survey of performance-based funding in higher education. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 23(2), 127–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600800120088625

- Joshi, P., Al‐Mudhaki, J., & Bremser, W. G. (2003). Corporate budget planning, control and performance evaluation in Bahrain. Managerial Auditing Journal, 18(9), 737–750. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686900310500505

- Julnes, P. D. L., & Holzer, M. (2001). Promoting the utilization of performance measures in public organizations: An empirical study of factors affecting adoption and implementation. Public Administration Review, 61(6), 693–708. https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-3352.00140

- Kadarisman, M. (2012). Manajemen Pengembangan Sumber Daya Manusia (Human resource development management). Raja Grafondo Persada.

- Kaplan, R. S., Norton, D. P., & Rugelsjoen, B. (2010). Managing alliances with the balanced scorecard. Harvard Business Review, 88(1), 114–120. https://uwosh.edu/chancellor/wp-content/uploads/sites/69/2017/01/FBP-Web-Article-4.pdf

- Kimunguyi, S., Memba, F., & Njeru, A. (2015). Effect of budgetary process on financial performance of Ngos in heath sector in Kenya. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 6(12), 163–172. http://www.ijbssnet.com/journals/Vol_6_No_12_December_2015/16.pdf

- Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447003000308

- Kretek, P. M., Dragšić, Ž., & Kehm, B. M. (2013). Transformation of university governance: On the role of university board members. Higher Education, 65(1), 39–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-012-9580-x

- Kristiantoro, H., Basuki, B., & Fanani, Z. (2017). The institutionalization of spending review in budgeting system in Indonesia. Journal of Accounting and Investment, 1(2), 36–53. https://doi.org/10.18196/jai.190190

- Kuhlmann, S. (2010). New public management for the ‘classical continental European administration’: Modernization at the local level in Germany, France and Italy. Public Administration, 88(4), 1116–1130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01869.x

- Lee, J. Y. J., & Wang, X. (2009). Assessing the impact of performance‐based budgeting: A comparative analysis across the United States, Taiwan, and China. Public Administration Review, 69, S60–S66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2009.02090.x

- Libby, T., & Thorne, L. (2009). The influence of incentive structure on group performance in assembly lines and teams. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 21(2), 57–72. https://doi.org/10.2308/bria.2009.21.2.57

- Liu, X., Ruan, D., & Xu, Y. (2005). A study of enterprise human resource competence appraisement. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 18(3), 289–315. https://doi.org/10.1108/17410390510591987

- Locke, E. A. (1975). Personnel attitudes and motivation. Annual Review of Psychology, 26(1), 457–480. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.26.020175.002325

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2013). New developments in goal setting and task performance. Routledge.

- Locke, E. A., Shaw, K. N., Saari, L. M., & Latham, G. P. (1981). Goal setting and task performance: 1969–1980. Psychological Bulletin, 90(1), 125. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.90.1.125

- Lorenz, C. (2012). Impact of performance budgeting on public spending in the German Laender the impact of performance budgeting on public spending in Germany’s Laender. Springer.

- Lu, Y., Willoughby, K., & Arnett, S. (2011). Performance budgeting in the American States: What’s law got to do with it? State and Local Government Review, 43(2), 79–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160323X11407523

- Lunenburg, F. C. (2011). Expectancy theory of motivation. International Journal of MBA, 15(1), 43–48. https://www.goalhub.com/s/Lunenburg-Fred-C-Goal-Setting-Theoryof-Motivation-IJMBA-V15-N1-2011.pdf

- Martí, C. (2013). Performance budgeting and accrual budgeting: A study of the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand. Public Performance & Management Review, 37(1), 33–58. https://doi.org/10.2753/PMR1530-9576370102

- Meister, J. C. (1998). Corporate universities: Lessons in building a world-class work force. McGraw-Hill New York, NY.

- Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340–363. https://doi.org/10.1086/226550

- Mourad, M. (2017). Quality assurance as a driver of information management strategy: Stakeholders’ perspectives in higher education. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 30(5), 779–794. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-06-2016-0104

- Murwaningsari, E. (2008). The role of organizational commitment and procedural justice in moderating the relationship between budgetary participation and managerial performance. Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business, 10(2), 185–210. https://doi.org/10.22146/gamaijb.5572

- Mustofa, A. (2015). The successful implementation of e-budgeting in public university: A study at individual level. Journal of Advances in Information Technology, 6(3), 135–139. https://doi.org/10.12720/jait.6.3.135-139

- Mwiya, B., Siachinji, B., Bwalya, J., Sikombe, S., Chawala, M., Chanda, H., Sakala, E., Muyenga, A., Kaulungombe, B., & Kayekesi, M. (2019). Are there study mode differences in perceptions of university education service quality? Evidence from Zambia. Cogent Business & Management, 6(1), 1579414. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2019.1579414

- Naranjo-Gil, D., Cuevas-Rodríguez, G., López-Cabrales, Á., & Sánchez, J. M. (2012). The effects of incentive system and cognitive orientation on teams’ performance. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 24(2), 177–191. https://doi.org/10.2308/bria-50098

- Naranjo-Gil, D., & Hartmann, F. (2006). How top management teams use management accounting systems to implement strategy. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 18(1), 21–53. https://doi.org/10.2308/jmar.2006.18.1.21

- Naranjo-Gil, D., & Hartmann, F. (2007). How CEOs use management information systems for strategy implementation in hospitals. Health Policy, 81(1), 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.05.009

- Noe, R. A., Hollenbeck, J. R., Gerhart, B., & Wright, P. M. (2017). Human resource management: Gaining a competitive advantage. McGraw-Hill Education New York, NY.

- Noman, Z. (2008). Performance budgeting in the United Kingdom. OECD Journal on Budgeting, 8(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1787/budget-v8-art4-en

- Osborne, D., & Gaebler, T. (1993). Reinventing government: How the entrepreneurial spirit is transforming the public sector. PLUME, Penguin Books USA Inc.

- Pham, H. T., & Starkey, L. (2016). Perceptions of higher education quality at three universities in Vietnam. Quality Assurance in Education, 24(3), 369–393. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAE-07-2014-0037

- Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638601200408

- Pratolo, S., & Jatmiko, B. (2017). Management accounting in Indonesian local government. LP3M UMY.

- Rahman, R. A. T., Irianto, G., & Rosidi, R. (2019). Evaluation of E-budgeting implementation in provincial government of DKI jakarta using CIPP model approach. Journal of Accounting and Investment, 20(1), 94–114. https://doi.org/10.18196/jai.2001110

- Robbins, S. P., & Judge, T. A. (2008). Organizational behavior 15th edition. Prentice Hall.

- Robbins, S. P., & Judge, T. A. (2013). Organizational behavior. Pearson education limited.

- Robinson, M., & Last, M. D. (2009). A basic model of performance-based budgeting. International Monetary Fund.

- Sandberg, J. (1996). Human competence at work: An interpretative approach. Academy of management journal, 43(1), 9-25. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556383

- Sayidah, N., & Ady, S. U. (2019). Quality and university governance in Indonesia. International Journal of Higher Education, 8(4), 10–17. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v8n4p10

- Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2010). Theoretical framework in theoretical framework and hypothesis development. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach, 80, 13–25.

- Shaw, J. D., Delery, J. E., & Abdulla, M. H. (2003). Organizational commitment and performance among guest workers and citizens of an Arab country. Journal of Business Research, 56(12), 1021–1030. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(01)00316-2

- Simons, R. (2000). Performance measurement & Control System for implementing strategy: Text & Cases. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- Sofyani, H. (2018). Does performance-based budgeting have a correlation with performance measurement system? Evidence from local government in Indonesia. Foundations of Management, 10(1), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.2478/fman-2018-0013

- Sofyani, H., & Akbar, R. (2013). Hubungan faktor internal institusi dan implementasi sistem akuntabilitas kinerja instansi pemerintah (SAKIP) di Pemerintah Daerah. Jurnal Akuntansi Dan Keuangan Indonesia, 10(2), 207–235. https://doi.org/10.21002/jaki.2013.10

- Sofyani, H., Akbar, R., & Ferrer, R. C. (2018). 20 years of performance measurement system (PMS) implementation in Indonesian local governments: Why is their performance still poor? Asian Journal of Business and Accounting, 11(1), 151–227. https://doi.org/10.22452/ajba.vol11no1.6

- Sofyani, H., Riyadh, H. A., & Fahlevi, H. (2020). Improving service quality, accountability and transparency of local government: The intervening role of information technology governance. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1735690. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1735690

- Suliman, A., & Al Kathairi, M. (2013). Organizational justice, commitment and performance in developing countries: The case of the UAE. Employee Relations, 35(1), 98–115. https://doi.org/10.1108/01425451311279438

- Tahar, A., & Sofyani, H. (2020). Budgetary participation, compensation, and performance of local government working unit: The intervening role of organizational commitment. Journal of Accounting and Investment, 1(1), 145–161. https://doi.org/10.18196/jai.2101142

- Tehseen, S., Ramayah, T., & Sajilan, S. (2017). Testing and controlling for common method variance: A review of available methods. Journal of Management Sciences, 4(2), 142–168. https://doi.org/10.20547/jms.2014.1704202

- Trakman, L. (2008). Modelling university governance. Higher Education Quarterly, 62(1‐2), 63–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.2008.00384.x

- Tsinidou, M., Gerogiannis, V., & Fitsilis, P. (2010). Evaluation of the factors that determine quality in higher education: An empirical study. Quality Assurance in Education, 18(3), 227–244. https://doi.org/10.1108/09684881011058669

- Vnoučková, L., Urbancová, H., & Smolová, H. (2018). Internal quality process management evaluation in higher education by students. DANUBE: Law, Economics and Social Issues Review, 9(2), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.2478/danb-2018-0005

- Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation. Wiley.

- Wardhani, R. S., Marwa, T., Fuadah, L., Siddik, S., & Awaluddin, M. (2019). Good university governance: Budgeting participation and internal control. Asia-Pacific Management Accounting Journal, 14(1), 1–18. http://dx.doi.org/10.24191/apmaj.v14i1.808

- Yılmaz, E., Özer, G., & Günlük, M. (2014). Do organizational politics and organizational commitment affect budgetary slack creation in public organizations. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 150, 241–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.09.047