Abstract

This research used the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) theoretical framework to extend and contribute to prior research on halal purchase behaviour. The main purpose of this study is to contribute to the literature by focusing on the relationship between religiosity and physical well-being and identifying the mediating halal-food consumption that affects on physical well-being. We applied non-probability convenience sampling to administer questionnaires among 315 Pakistani Muslim and Non-Muslim respondents currently living in Pakistan, the USA, Canada, Australia, and Germany, during the winter of 2019–2020. The study used a partial-least-squares structural-equation-modeling (PLS-SEM) technique to investigate the data, which provides evidence of reliability and validity. Further, we used the PLS-SEM technique in investigating the relationship among religiosity, halal-food consumption, and physical well-being. The results show that the behavioural intention to buy halal food mediated the relationship between religiosity and physical well-being. Halal-food consumption mediated the relationship between subjective norms and physical well-being. However, it did not mediate the relationship between attitude and physical well-being, perceived behavioural control, and physical well-being. Further, this study also found that behavioural intention to buy halal food has a significant direct positive relationship with religiosity, attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control. The findings have important implications for food manufacturers and marketers in devising a policy on marketing campaigns to attract very health-conscious customers.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

There are many religions with dietary restrictions and food traditions. Therefore, religion can influence the individual choice. The main purpose of this study is to investigate the relationship between religiosity and physical well-being and identifying the mediating halal-food consumption that impacts physical well-being. This research used the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) theoretical framework to extend and contribute to prior research on halal purchase behaviour. The results show that the behavioural intention to buy halal food mediated the relationship between religiosity and physical well-being. Further, this study also found that behavioural intention to purchase halal food has a significant direct positive relationship with religiosity, attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control. This study also offers insightful, practical implications. First, both regulatory bodies and halal-food manufacturers should create social expectations for behavioural intention to buy halal food. Second, this research can be useful for food manufacturers and marketers devising a policy on marketing campaigns to attract the health conscious customers.

1. Introduction

The term “Halal” is an Arabic term derived from the Arabic language, meaning “permitted or legitimate.” Muslims have significant awareness regarding necessities for devouring only Halal food (Ali et al., Citation2017). All religion restricts food choices in some way. For example, all major religions, including Islam, Hinduism, Judaism, Jewish, Buddhism, and Christianity, create influential and effective roles for prohibiting specific foods (Sack, Citation2001). For a Muslim community, Halal food and its consumption pattern have become significant (Bonne et al., Citation2009). Religious perception is an essential fact that influences consumption (Essoo & Dibb, Citation2004). In numerous communities, religion plays a significant role in molding food choices (Dindyal, Citation2003; Musaiger, Citation1993). Food consumption and religion’s impact depends on the individual and on how many individuals interpret, practice, and comply with or follow the teaching of their faith (belief) (Sack, Citation2001).

Previous studies suggest that individuals consume healthy food to support their physical well-being (Dixey et al., Citation1999; Zulkiple & Nur Salimah, Citation2006). There is a strong relationship between religion and halal food (Ahmed et al., Citation2014; Bonne et al., Citation2007). Ahasanul et al. (Citation2015) suggest a strong correlation of perceived behavioural control and subjective norms with halal-food consumption. Sawari et al. (Citation2020) indicated that halal-food consumption could influence spiritual and physical well-being. The above discussion suggests the need to link all these variables in such a way as to examine the relationship between the religionist, halal-food consumption, and physical well-being.

Our study incorporates three TPB elements: subjective norm, attitude, and perceived behavioural control, and one aspect of religiosity. We treat them independently to examine their effects on halal-food consumption and physical well-being. Overall, this study thereby contributes to the literature by focusing on the relationship between religiosity and physical well-being and identifying the mediation by halal-food consumption that impacts physical well-being.

2. Research hypothesis and theory

The theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1985, Citation1991) is set by attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control. Attitude is a psychological drift shown by assessing specific entities’ point of likes and dislikes (Eagly & Chaiken, Citation1995). Subjective norm is social pressure on people to execute or not execute bound behaviour. Perceived behavioural control delineates perception to the extent that the behaviour is considered controllable (Liou & Contento, Citation2001). This study predicted that the longing to consume halal food and stay healthy could influence individual perception and belief (Honkanen et al., Citation2005; Verbeke et al., Citation2004).

2.1. Religiosity and behavioural intention to buy halal food

Consumers with religious perceptions will prefer and buy more halal food, and they will resist getting involved in those activities against their religion’s teaching and guidelines (Masnono, Citation2005; Schneider et al., Citation2011). Many researchers suggest that it is a religious duty to consume goods under Islamic jurisdiction and only permissible by God (Borzooei & Asgari, Citation2013; Hanzaee & Ramezani, Citation2011; Wilson et al., Citation2013). As a religion, Islam teaches its devotees to consume only halal foods (Riaz & Chaudry, Citation2004; Tieman & Hassan, Citation2015). The above discussion suggests that religiosity influences the behavioural intention to buy halal food (Essoo & Dibb, Citation2004; Mukhtar & Butt, Citation2012). In this regard, the following hypothesis about behavioural intention to purchase halal food is proposed:

H1: Religiosity is positively related to behavioural intention to buy halal food.

2.2. Attitude and behavioural intention to buy halal food

A study by Golnaz et al. (Citation2010) found that consumer attitudes towards halal food are the most important, compelling predictor of intention. Khan and Azam (Citation2016) reported that the attitude used to be the most significant factor in predicting the choice of purchasing halal food. Many previous studies suggest or conclude that halal food attitude affects consuming halal food (Afendi et al., Citation2014; Lada et al., Citation2009; Mukhtar & Butt, Citation2012). Choo et al. (Citation2004) also found a positive relationship between the innovation-oriented consumer and purchase intention. In this regard, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Customer attitude is positively related to behavioural intention to buy halal food.

2.3. Subjective norm and behavioural intention to buy halal food

Subjective norms and intention to choose halal products have a positive relationship (Lada et al., Citation2009; Shepherd & O’keefe, Citation1984; Shimp & Kavas, Citation1984; Tarkiainen & Sundqvist, Citation2005; Vallerand et al., Citation1992). A study by Karijin et al. (Citation2007) found that regarding attitude towards halal-meat purchasing in France, social norms, perceived behavioural control, and attitude have a significant relationship to consume halal meat. Alam and Sayuti (Citation2011) argue that subjective norms significantly impact Malaysian consumers’ halal-food-buying behaviour. Bonne et al. (Citation2007) also found and confirmed that social norms, attitude, and perceived behaviour have significance for consuming halal meat. In this regard, the following hypothesis is proposed from the perspective of subjective norm and halal-food-purchase intention.

H3: Subjective norm is positively related to behavioural intention to buy halal food.

2.4. Perceived behavioural control and behavioural intention to buy halal food

Kim and Chung (Citation2011) found that perceived behavioural control is an essential predictor with a significant impact on intention. Perceived behavioural control is the degree to which individuals perceive engaging behaviour (Liou & Contento, Citation2001). It has two discrete parts: how much jurisdiction an individual has over behaviour and how confident individuals feel about acting or not acting out particular behaviours. If an individual feels more likely to control behaviour about the decision to buy halal food, the more likely it is that the individual will do so (Ajzen, Citation1991). Many scholarly circles also confirm this relationship (Karijin et al., Citation2007; Liou & Contento, Citation2001; Yang et al., Citation2012). As discussed, we thus propose the following hypothesis:

H4: Perceived behavioural control is positively related to behavioural intention to buy halal food.

2.5. Halal-food consumption and physical well-being

Many researchers suggest that healthy food improves physical well-being (Dixey et al., Citation2006; Zulkiple & Nur Salimah, Citation2006). Ghazali and Sawari (Citation2015) explain that halal-food consumption relates to spiritual and physical well-being at various places in his manuscript. Moreover, Boyle, Whitted & College (Citation2009) found that human body energy, esteem level, and negative mood variation occur because they take unhealthy food. Halal food has quality, safety, and hygiene, so consumers buy and consume halal food (Vogt et al., Citation2012). There is a strong relationship between religion and halal meat, making this decision more important for Muslim consumers and leading to a different decision-making process (Ahmed et al., Citation2014; Bonne et al., Citation2007). The above discussion suggests a need to link all these variables in such a way as to examine the relationship between halal-food consumption and physical well-being. In this regard, the following hypothesis about physical well-being is proposed.

H5: Halal-food consumption is positively related to physical well-being.

2.6. Mediating effect of behavioural intention to buy halal food

The intention is a manifestation of an individual’s inclination to act out specific behaviour. Several studies have examined intent as a robust estimator of behaviour (Taylor & Todd, Citation1995). The intention is the dependent variable predicted by an independent variable, such as attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control (Jahya, Citation2004). Ali et al. (Citation2017) investigate the determinant of halal-meat consumption within the international Muslim student population in China by using planned behaviour theory. Bonne et al. (Citation2007) suggest that the halal-food-purchase intention mediates the relationship of religiosity, attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control to physical well-being. As discussed above, we thus propose the following hypotheses:

H6-a: Halal-food consumption will mediate the relationship between religiosity and physical well-being.

H6-b: Halal-food consumption will mediate the relationship between attitude and physical well-being.

H6-c: Halal-food consumption will mediate the relationship between subjective norm and physical well-being.

H6-d: Halal-food consumption will mediate the relationship between perceived behavioural control and physical well-being.

3. Conceptual framework

A theory of planned behaviour (TPB) (Ajzen, Citation1985, Citation1991) was used to propose a research model. The present study explains how people’s desire to perform their buying behaviour determines their perception. Ahasanul et al. (Citation2015) report a strong correlation of perceived behavioural control and subjective norms towards halal-food consumption.

Religion can also influence food-buying behaviour and attitude (Delener, Citation1994; Pettinger et al., Citation2004). Our study incorporated three TPB elements: subjective norm, attitude, and perceived behavioural control, and one aspect of religiosity.

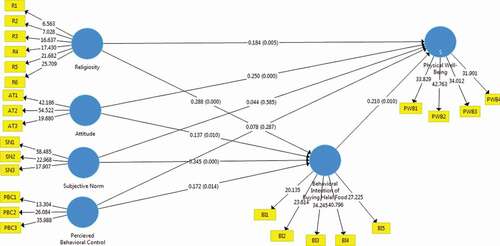

shows the proposed structural model, comprising three types of variables, including four predictors (i.e., religiosity, attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control), one mediator variable (behavioural intention to buy halal food), and one dependent variable (physical well-being). Each component of the model was based on the literature review. Overall, this study thereby contributes to the literature by focusing on the relationship between religiosity and physical well-being and identifying the mediating halal-food consumption that impacts physical well-being.

4. Data and methodology

The present research applied a convenience sampling technique to administer the questionnaires among 315 Pakistani Muslims and Non-Muslims respondents currently living in Pakistan, the USA, Canada, Australia, and Germany during the winter of 2019–2020 self-administered method. Tabachnick and Fidell (Citation1996) suggested that the sample size, N, should equal or exceed 50 + 8p, where p equals the number of predictor variables. The present study applied a partial-least-squares structural-equation-modeling (PLS-SEM) technique to investigate the data, which provides evidence of reliability and validity. According to Henseler et al. (Citation2009), Smart PLS is a statistical tool with the competence to achieve an elevated level of statistical power, even in the study of a small sample. Further, the PLS-SEM technique was used to investigate the relationship between religiosity and physical well-being and identify the mediating halal-food consumption that affects physical well-being.

4.1. Measurement (Questionnaire and scaling)

A five-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” (1) to “Strongly Agree” (5) was adopted for this study. An English-language survey questionnaire was prepared. The first part of the questionnaire briefly explains the research purpose and guidelines for filling out the questionnaire and relation to socio-demographic information. Questions included the respondent’s age, marital status, gender, region, occupation, and education. The second part, for the development of the model structure, consisted of multiple-choice-item scales.

4.1.1. Attitude

Based on previous studies, the attitude was measured through the statement, “Halal meat is important to me” (Bissonnette et al., Citation2001; Magnusson et al., Citation2001). Four items were measured (see Appendix A) by using a five-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” (1) to “Strongly Agree” (5).

4.1.2. Subjective norm

Subjective norm consisted of multiple items to assess the motivation to abide by how much you take encouragement to consume halal meat from the following institution and people into consideration (Conner & Sparks, Citation1996)? Choices were ranked on a five-point scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” (1) to “Strongly Agree” (5) for religious authority, friends, family, partners, children, and the Islamic community in general.

4.1.3. Perceived behavioural control

This study adopted perceived behavioural control from a previous study (Conner & Sparks, Citation1996). It measured how much control individuals have overeating halal meat, using a seven-point scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” (1) to “Strongly Agree” (5).

4.1.4. Religiosity

This study adopted religiosity from previous work by Salman and Siddiqui (Citation2011). Six measurement items were used to measure religiosity by employing related questions, using a five-point Likert scale.

4.1.5. Behavioural intention to consume halal food

According to Ajzen (Citation1991), intention is a motivating factor that influences behaviour. This shows how firmly the individual is willing to make an effort and how much endeavour they plan to practice to act out the behaviour. This study focuses on the actual behaviour of halal-food consumption. Behavioural intention to consume halal food was measured by using a five-point Likert scale.

4.1.6. Physical well-being

Physical well-being relates to psychological function, which relates to positive social engagement, feelings, thoughts, competence, and purpose of life (Lucas & Diener, Citation2009). Utz (Citation2011) briefly describes human psychology as consisting of the study of “soul (ruh) physical body, behaviour emotion, and thought.” This study measured physical well-being by employing related questions, measuring six-item scales using a five-point Likert scale.

5. Results and discussion

5.1. Characteristics of the respondents

represents demographic information, including gender, age, education level, marital status, and occupation. The respondents are largely female (63.8 percent), with the overall dominance of private-sector employees (52.7 percent) and non-married respondents (64.4 percent). Respondents with the highest education level hold a master’s degree (46.3 percent). Regarding age, our respondents are mainly in the “18–25” category (45.1 percent) and the “26–35” category (39.7 percent).

Table 1. Demographic profile of the respondents

6. Analysis and results

For examination of validity and reliability, the PLS-SEM statistical technique was used to measure the model. The data were analysed using smart PLS 3.0 (Ringle et al., Citation2015). As suggested by Anderson and Gerbing (Citation1988) and Henseler et al. (Citation2009), a two-stage analytical procedure was adopted. Internal consistency, reliability, discriminant, and convergent validity were tested in the first stage. The second stage involved estimating the mediation model and testing the hypotheses.

6.1. Measurement model assessment

For the assessment of the measurement model, factor loading, Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability, and average variance extracted (AVE), and discriminant validity were estimated. The measurement model has been analysed based on partial-least-squares structural-equation-modeling, with the help of smart PLS 3.0 (Ringle et al., Citation2015). and show the results of the assessed measurement model.

Figure 2. A two—step partial least squares assessment process (Henseler et al., Citation2009)

Table 2. Internal Consistency, Convergent Validity, Composite Reliability, and AVE

manifests the composite reliability (CR) exceeded the recommended value of 0.7 (Hair et al., Citation2012). The results show that the average variance extracted (AVE) is higher than the recommended value of 0.5 by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981). Overall, these results provide adequate support for the soundness of scale structures.

shows that AVE’s value for each latent construct is more than 0.50, resulting in good convergent validity (Hair et al., Citation2010). According to Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) criterion, AVE’s square root is greater than each construct’s inter-construct correlation. As shown in boldfaced items in diagonal in , the AVE’s square root for all variables exceeded the intercorrelation, indicating sufficient discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Hair et al., Citation2010).

Table 3. Discriminant Validity

7. Structural model assessment

With the help of Smart PLS 3, a structural model was applied to assess the measurement model. The direct and indirect effects were examined for this purpose (see ). This study has five direct hypotheses, as shown in and . All direct hypotheses (H1, H2, H3, H4, and H5) were accepted, as the p-value was less than 0.05. Moreover, PLS-SEM bootstrapping was applied to examine the mediation effect (Hair et al., Citation2014). According to (Ringle et al., Citation2015), assessing the t value with the bootstrapping technique’s help could occur by re-sampling five hundred samples. Rigdon (Citation2016) also confirmed the use of small sample sizes in applying PLS-SEM latent variable scores in subsequent analysis and endeavouring to overcome factor based SEM’s limitation.

Table 4. Structural Model Assessment (Direct Effect Result and Decision)

shows the results of the mediation analysis. Two mediating effects (H6-a and H6-c) were accepted, as their significance values were less than 0.05. Hence, halal-food consumption mediates the relationship. The remaining two (H6-b and H6-d) were insignificant .

Figure 3. Direct Effect, Structural Model Assessment. It mainly demonstrates the t value and the path coefficient to accept or reject the hypothesis. This Figure shows the direct and indirect relationship

Table 5. Structural Model Assessment (Indirect effect results and decisions)

As stated by Chin et al. (Citation2003), PLS can give more accurate estimates of mediating effects by accounting for the error that attenuates the estimated relationships and improves the validation of theories (Helm et al., Citation2010; Henseler & Chin, Citation2010).

revealed the value of R^2. It stipulates placing all control constructed injunctions that demonstrate a propensity for influencing and variation on the dependent variable given in . In addition, revealed that the output of f^2 shows the effect size off

Table 6. R square Value (R2)

Table 7. Effect Size of (f^2)

the square. According to Cohen (Citation1988), the value of f^2 reflects strong when the value of f square 0.35 strong, moderate 0.15, and value of 0.02 reflects is small. In this study, the value of f square for variables such as Religiosity, Attitude, Perceived Behavioural Control, and Subjective Norm is little and f square for variables Behavioural Intention of Buying Halal Food and Religiosity are strong, more than 0.35, as stated by Cohen (Citation1988).

8. Research findings and discussion

The direct effect of religiosity, attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control on behavioural intention to buy halal food shows t-values of 2.536, 4.022, 4.954, 2.420, and 2.488 with β-values 0.288, 0.137, 0.345, 0.172, and 0.210, respectively. These values prove that religiosity, attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control have a significant positive relationship with behavioural intention to buy halal food. These results support H1, H2, H3, H4, and H5. Therefore, increasing the level of religiosity, attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control will enhance the purchase intention of buying halal food. These findings are in line with prior studies by Shaari and Mohd Arifin (Citation2009), Essoo and Dibb (Citation2004), Mukhtar and Butt (Citation2012), and Bashir (Citation2019).

Furthermore, it was found that religiosity has a significant and positive impact on behavioural intention to buy halal food. By analysing data, it was shown that the t-value was 2.536, and the β value was 2.088. This demonstrates that religiosity has a significant and positive relationship with behavioural intention to buy halal food. It means that religiosity shapes specific human attitudes and behaviour, to prompt the choice to buy halal food. This finding is consistent with the prior study by Shaari and Mohd Arifin (Citation2009).

Moreover, regarding the relationship between subjective norms and halal-food-buying behaviour, both have a significant positive relationship with each other, with t-value 4.954 and β value 0.345. This result indicates that subjective norm is the most important predictor in identifying the behavioural intention. It means that people give great importance to social pressure to perform a specific type of behaviour. This implies that friends, family members, and colleagues can influence behavioural intention to buy halal food. This finding is in line with the prior studies by Ahmed et al. (Citation2014), Ali et al. (Citation2017), and Bonne et al. (Citation2007).

Nevertheless, while examining the mediation role of behavioural intention to buy halal food, t-values of 2.457, 1.656, 2.070 and 1.679 and β-values 0.061, 0.029, 0.073, and 0.036, respectively, were found for religiosity and physical well-being, attitude and physical well-being, subjective norm and physical well-being and perceived behavioural control and physical well-being, respectively. The mediating effect was found to be significant, demonstrating that halal-food consumption mediates the relationship between religiosity and physical well-being. Also, halal consumption mediated the relationship between subjective norm and physical well-being. These results support H6-a and H6-c. However, halal-food consumption did not mediate attitude and physical well-being, and perceived behavioural control and physical well-being. These findings did not support H6-b and H6-d, consistent with prior studies by Han et al. (Citation2010) and Omar et al. (Citation2013).

9. Conclusion and managerial implications

The main objective of this research was to contribute to the literature by focusing on the relationship between religiosity and physical well-being, as well as identifying the mediating halal-food consumption that impacts physical well-being. Cross-sectional data were collected through an online survey with 315 Pakistani Muslims and Non-Muslims currently living in Pakistan, the USA, Canada, Australia, and Germany, from which we got 201 women and 114 men respondent responses, as a result proved that in study women respondent are 63.8% and men respondent are 32.2%, it implies that female respondent greater than male. The study used a partial-least-squares structural-equation-modeling (PLS-SEM) technique to analyse the data, providing evidence of reliability and validity. Further, the PLS-SEM technique was used to investigate the relationship among religiosity, halal-food consumption, and physical well-being.

We can conclude that religiosity, attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control have a significant and positive impact on behavioural intention to buy halal food. This shows that religiosity has a significant influence on shaping consumer attitude and behaviour towards buying halal food (Borzooei & Asgari, Citation2013; Wilson et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, attitude is an important factor in influencing intention to purchase halal-food products (Golnaz et al., Citation2010; Khan & Azam, Citation2016). Moreover, social pressure may play an important role in building an intention to buy halal food. In collectivistic cultures, such as the Muslim culture, people tend to strive for their group rather than for personal goals. This finding is in line with the prior studies by Karijin et al. (Citation2007) and Kamariah and Muslim (Citation2007).

The present study found that halal-food consumption mediated the relationship between religiosity and physical well-being. This study also confirmed that behavioural intention to buy halal food mediated the relationship between subjective norm and physical well-being. This finding is consistent with previous studies (Zulkiple & Nur Salimah, Citation2006), in which the researchers indicate that healthy food can support physical well-being. Moreover, the previous studies found a significant and positive association between religiosity, subjective norm, and halal food (Ahmed et al., Citation2014; Bonne et al., Citation2007). Previous studies by Rezai et al. (Citation2012, Citation2015) indicate that consumers prefer halal food because quality and hygiene help their physical growth.

This study also offers insightful, practical implications. First, both regulatory bodies and halal-food manufacturers should create social expectations for behavioural intention to buy halal food. Second, halal-food manufacturers and marketers can devise policy for marketing campaigns to influence consumers’ social and religious perceptions regarding purchasing halal food. Third, this research can be useful for food manufacturers and marketers devising a policy on marketing campaigns to attract those customers who are very health conscious.

9.1. Limitations and future research directions

This study is not without limitations. This study is conducted in the food sector, considered less informative than other halal businesses across the globe. Furthermore, the respondents were consumers of halal food; it would be interesting to acquire data from other stakeholders, such as halal-food manufacturers, marketers, and retailers. Future studies could also add more demographic characteristics to see halal-food consumption’s effect on consumers’ behavioural intention.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Shahida Suleman

Shahida Suleman is currently pursuing a Ph.D. degree in Economics and Finance from the Department of Management, Sunway University Business School, Malaysia. She worked as a lecturer at Ilma University Management Sciences Department located in Karachi, Pakistan. Her research interest area is Economics and Finance, Corporate Accounting, Marketing, and Supply Chain Management. She has attended a professional and research training session at the domestic and international levels.

References

- Afendi, N. A., Azizan, F. L., & Darami, A. I. (2014). Determinants of halal purchase intention case in Perlis. International Journal of Business and Social Research, 4(5), 118–17.

- Ahasanul, H., Abdullah, S., Farzana, Y., Run, K. T., & Mirza, A. H. (2015). Non-Muslim consumer’perception toward purchasing halal food products in Malaysia. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 6(1), 133–147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-04-2014-0033

- Ahmed, Z. U., Al-Kwifi, O. S., Saiti, B., & Othman, N. B. (2014). Consumer behavior dynamics of Chinese minorities. Journal of Technology Management in China, 9(1), 6–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JTMC-10-2013-0038

- Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Kuhl, Julius, Beckmann, Jürgen. Action control (pp. 11–39). Springer.

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Alam, S. S., & Sayuti, N. M. (2011). Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) in halal food Purchasing. International Journal of Commerce and Management, 21(1), 8–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/10569211111111676

- Ali, A., Xiaoling, G., Sherwani, M., & Ali, A. (2017). Factors affecting Halal meat purchase intention. British Food Journal, 119(3), 527–541. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-10-2016-0455

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Awan, H. M., Siddiquei, A. N., & Haider, Z. (2015). Factors affecting Halal purchase intention–evidence from Pakistan’s Halal food sector. Management Research Review, 38(6), 640–660. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-01-2014-0022

- Ayyub, R. M. (2015). “An empirical investigation of ethnic food consumption,”. British Food Journal, 117(4), 1239–1255. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-12-2013-0373

- Bashir, A. M. (2019). Effect of halal awareness, halal logo and attitude on foreign consumers’ purchase intention. British Food Journal, 121(9), 1998–2015. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-01-2019-0011

- Bissonnette, M., Contento, M., & Isobel, R. (2001). Adolescents’ perspectives and food choice behaviours in terms of the environmental impacts of food. Journal of Nutrition Education, 33(2), 72–83. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1499-4046(06)60170-X

- Bonne, K., Verbeke, W., & Vermeir, I. (2009). Impact of religion on halal meat consumption decision making in Belgium. Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing, 21(1), 5–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08974430802480628

- Bonne, K., Vermeir, I., Blackler, B. F., & Verbeke, W. (2007). Determinants of halal meat consumption in France. British Food Journal, 109(5), 367–386. Retrieved July 8, 2010, from http://www.emeraldinsight.com

- Borzooei, M., & Asgari, M. (2013). Establishing a Global Halal Hub: In-Depth Interviews. Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 3(10), 169–181. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v3-i10/288

- Boyle, Whitted & College. (2009). The psychological effects of food. Retrieved April, 22, 2015 from http://vault.hanover.edu/~altermattw/methods/assets/posterpics/Fall2009/Whitted%20&%20Boyle.pptx

- Chin, W. W., Marcolin, B. L., & Newsted, P. R. (2003). A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Information Systems Research, 14(2), 189–217. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.14.2.189.16018

- Choo, H., Chung, J. E., & Pysarchik, D. T. (2004). Antecedents to new food product purchasing behavior among innovator groups in India. European Journal of Marketing, 38(5/6), 608–625. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560410529240

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

- Conner, M. T., & Sparks, P. (1996). The theory of planned behaviour and health behaviours. Predicting Health Behaviour, 2(1), 121–161.

- Delener, N. (1994). Religious contrast in consumer decision behavior patterns: Their dimensions and marketing implications. European Journal of Marketing, 28(5), 36–53. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/03090569410062023

- Dindyal, S. (2003). How personal factors, including culture and ethnicity, affect the choices and selection of food we make. Internet Journal of Third World Medicine, 1(2), 27–33. https://print.ispub.com/api/0/ispub-article/11779

- Dixey, R., Heindl, I., Loureiro, I., Pérez-Rodrigo, C., Snel, J., & Warnking, J. (2006). Healthy Eating For Young People In Europe. International Planning Committee (IPC)

- Dixey, R., Heindl, I., Loureiro, I., Pérez-Rodrigo, C., Snel, J., & Warnking, P. (1999). Healthy eating for young people in Europe. In Vivian Barnekow Rasmussen. Nutrition education in Health Promoting Schools. European Network of Health Promoting Schools.

- Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1995). Attitude strength, attitude structure, and resistance to change. Attitude Strength: Antecedents and Consequences, 4, 413–432. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1995-98997-016

- Essoo, N., & Dibb, S. (2004). Religious influences on shopping behaviour: An exploratory study. Journal of Marketing Management, 20(7–8), 683–712. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1362/0267257041838728

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Ghazali, M. A. I., & Sawari, S. S. M. (2015). Mengglobalisasikan Sistem Piawaian Standard Halal Malaysia di Peringkat Dunia. Sains Humanika, (3), 15–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.11113/SH.V5N3.662

- Golnaz, R., Zainulabidin, M., Mad Nasir, S., & Eddie Chiew, F. C. (2010). Non-Muslim perception awareness of halal principle and related food products in Malaysia. InternationalFoodResearch Journal, 17(3), 667–674. https://www.academia.edu/965378/Non_Muslims_awareness_of_Halal_principles_and_related_food_products_in_Malaysia

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2010). SEM: An Introduction. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 5(6), 629–686. https://www.worldcat.org/title/multivariate-data-analysis-a-global-perspective/oclc/317669474

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sartedt, M. (2014). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling. Sage.

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012). An assessment of the use of Partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 414–433. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6

- Han, H., Hsu, L. T., & Sheu, C. (2010). Application of the theory of planned behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tourism Management, 31(3), 325–334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.03.013

- Hanzaee, K. H., & Ramezani, M. R. (2011). Intention to Halal Products In THe World Markets. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research in Business, 1(5), 1–7. http://journaldatabase.info/articles/intention_halal_products_world_markets.html

- Helm, S., Eggert, A., & Garnefeld, I. (2010). Modeling the impact of corporate reputation on customer satisfaction and loyalty using partial least squares. In Vincenzo Esposito VinziWynne W. ChinJörg HenselerHuiwen Wang. eds. Handbook of partial least squares (pp. 515–534). Springer.

- Henseler, J., & Chin, W. W. (2010). A Comparison of Approaches for the Analysis of Interaction Effects Between Latent Variables Using Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. Structural Equatio Modeling-a Multidisciplinary Journal, 17(1), 82–109. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510903439003

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in International marketing. New Challenges to International Marketing, 20, 277–319. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/S1474-7979(2009)0000020014

- Honkanen, P., Olsen, S. O., & Verplanken, B. (2005). Intention to consume seafood- the importance of habit. Appetite, 45(2), 161–168. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2005.04.005

- http://cits.tamiu.edu/kock/pubs/journals/2018/Kock_Hadaya_2018_ISJ_SampleSizePLS.pdf

- Jahya, N. B. (2004). Factors that influence muslim consumers preference towards Islamic banking products or facilities. Theory of reasoned action [Dissertation].

- Kamariah, N., & Muslim, N. (2007). The application of the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) in internet purchasing: Using SEM. In International Conference on Marketing and Retailing, Petaling Jaya (pp. 196–205).

- Karijin, B., Iris, V., Florence, B. B., & Wim, V. (2007). Determinants of halal meat consumption in France. British Food Journal, 109(5), 367–386. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/0070700710746786

- Khan, A., & Azam, M. K. (2016). Factors influencing halal products purchase intention in India: Preliminary Investigation. IUP Journal of Marketing Management, 15(1), 20. https://search.proquest.com/openview/4abc530cf30f44fe29b405efe559c968/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=54464

- Kim, H. Y., & Chung, J. E. (2011). Consumer purchase intention for organic personal care products. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 28(1), 40–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761111101930

- Lada, S., Harvey Tanakinjal, G., & Amin, H. (2009). Predicting intention to choose halal products using Theory of reasoned action. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management, 2(1), 66–76. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/17538390910946276

- Liou, D., & Contento, I. R. (2001). Usefulness of psychosocial theory variables in explaining fat-related Dietary behavior in Chinese Americans: Association with degree of acculturation. Journal of Nutrition Education, 33(6), 322–331. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1499-4046(06)60354-0

- Lucas, R. E., & Diener, E. (2009). Personality and subjective well-being. The Science of Well- Being, 37, 75–102. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2009-09426-004

- Magnusson, M. K., Arvola, H. U.-K.-K., & Sjo ¨den, P.-O. (2001). Attitudes towards organic foods among Swedish consumers. British Food Journal, 103(3), 209–227. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/00070700110386755

- Masnono, A. (2005). Factors influencing the Muslim consumer’s level of confidence on halal logo issued by Jakim: An empirical study [Unpublished master’s thesis]. University Saints Malaysia.

- Mukhtar, A., & Butt, M. (2012). Intention to choose Halal products: The role of religiosity. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 3(2), 108–120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/17590831211232519

- Musaiger, A. O. (1993). Socio-cultural and economic factors affecting food consumption patterns in the Arab countries. Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health, 113(2), 68–74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/146642409311300205

- Omar, E. N., Jaafar, H. S., & Osman, M. R. (2013). Halalan toyyiban supply chain of the food industry. Journal of Emerging Economies and Islamic Research, 1(3), 1–2. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.24191/jeeir.v1i3.9127

- Pettinger, C., Holdsworth, M., & Gerber, M. (2004). Psycho-social influences on food choice in Southern France and Central England. Appetite, 42(3), 307–316. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2004.01.004

- Rezai, G., Mohamed, Z., & Shamsudin, M. N. (2012). Non-Muslim consumers’ understanding of Halal principles in Malaysia. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 3(1), 35–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/17590831211206572

- Rezai, G., Mohamed, Z., & Shamsudin, M. N. (2015). Can halal be sustainable? Study on Malaysian consumers’ perspective. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 21(6), 654–666. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10454446.2014.883583

- Riaz, M. N., & Chaudry, M. M. (2004). The value of halal food production-Mian N. Riaz and Muhammad M. Chaudry define what halal and kosher foods are, describe why they are not the same thing, and what is required of processors. Inform-International News on Fats Oils and Related Materials, 15(11), 698–701. https://www.al-rida.net/attachments/040_halal.pdf

- Rigdon, E. E. (2016). Choosing PLS path modeling as analytical method in European management research: A realist perspective. European Management Journal, 34(6), 598–605. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2016.05.006

- Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J. M. (2015). Smart PLS 3. Boenningstedt: Smart PLS GmbH. http://www.smartpls.com

- Sack, D. (2001). Whitebread protestants: Food and religion in american culture. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Salman, F., & Siddiqui, K. (2011). An exploratory study for measuring consumers awareness and perceptions towards halal food in Pakistan. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, 3(2), 639–651. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2449144

- Sawari, M., & Salwa, S. (2017). The Relationship of Halal Food Consumptions And Psychological Features Of Muslim Students In Malaysian Universities [Doctoral dissertation, Thesis Doctor o Philosophy]. University Technology Malaysia.

- Sawari, S. S. M., Ghazali, M. A. I., & Jumahat, T. (2020). Determinants of consumer demeanors with regard to halal food. International Journal of Information, Business and Management, 12(2), 179–184. https://core.ac.uk/reader/300478230

- Schneider, H., Krieger, J., & Bayraktar, A. (2011). The impact of intrinsic religiosity on consumers’ ethical beliefs: Does it depend on the type of religion? A comparison of Christian and Moslem consumers in Germany and Turkey. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(2), 319–322. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0816-y

- Shaari, J. A. N., & Mohd Arifin, N. S. (2009). Dimension of halal purchase intention: A preliminary study. https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/50714441/dimension-of-halal-purchase-intention-international-review-of

- Shepherd, G. J., & O’keefe, D. J. (1984). Separability of attitudinal and normative influences on behavioral intentions in the Fishbein-Ajzen model. The Journal of Social Psychology, 122(2), 287–288. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1984.9713496

- Shimp, T. A., & Kavas, A. (1984). The theory of reasoned action applied to coupon Usage. Journal of Consumer Research, 11(3), 795–809. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/209015

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (1996). Using multivariate statistics (3rd ed.). HarperCollins.

- Tarkiainen, A., & Sundqvist, S. (2005). Subjective norms, attitudes and intentions of Finnish consumers in buying organic food. British Food Journal, 107(11), 808–822. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/00070700510629760

- Taylor, S., & Todd, P. (1995). Decomposition and crossover effects in the theory of planned behavior: A study of consumer adoption intentions. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 12, 137–156. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0167–8116(94)00019-K

- Tieman, M., & Hassan, F. H. (2015). Convergence of food systems: Kosher, Christian and Halal. British Food Journal, 117(9), 2313–2327. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-02-2015-0058

- Utz, A. (2011). Psychology from the Islamic perspective. International Islamic Publishing House.

- Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., Blais, M. R., Brière, N. M., Senécal, C., & Vallières, E. F. (1992). The academic motivation scale: A measure of intrinsic, extrinsic, and a motivation in education. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 52(4), 1003–1017. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164492052004025

- Verbeke, W., Vermeir, I., & Vackier, I. (2004) in J. De Tavernier & S. Aerts. (Eds), “Impact of values, involvement and perceptions on consumer attitudes and intentions towards sustainable food consumption. In Proceedings of the EURSAFE 2004 - Science, Ethics and Society, Centre for Agricultural, Bio- and Environmental Ethics (pp. 81–85).

- Vogt, R., Bennett, D., Cassady, D., Frost, J., Ritz, B., & Hertz-Picciotto, I. (2012). Cancer and non-cancer health effects from food contaminant exposures for children and adults in California: A risk assessment. Environmental Health, 11(1), 2–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-11-83

- Wilson, J. A., Belk, R. W., Bamossy, G. J., Sandikci, Ö., Kartajaya, H., Sobh, R., Liu, J., & Scott, L. (2013). Crescent marketing, Muslim geographies and brand Islam: Reflections from the JIMA Senior Advisory Board. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 4(1), 22–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/17590831311306336

- Yang, H., Liu, H., & Zhou, L. (2012). Predicting young Chinese consumers’ mobile viral attitudes, intents and behavior. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 24(1), 59–77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/13555851211192704

- Zulkiple, A. G., & Nur Salimah, M. (2006). Penghayatan Agama Sebagai Asas Pembanguna Pelajar: AnalisisTerhadap Beberapa Pandangan Al-Imam Al-Ghazali. Retrieved February, 27, 2015 from http://eprints.utm.my/375/1/ZULKIPLEABDGHANI2006_PenghayatanaGamasebagaiasaspembangunan.pdf

Appendix: Questionnaire

Attitude

(Afendi et al., Citation2014; Karijin et al., Citation2007)

Eating halal food is important to me. (A1)

Halal food is healthy. (A2)

Halal food is safe to eat. (A3)

Halal food is clean. (A4)

Subjective norm

(Karijin et al., Citation2007)

Most people who are important to me choose halal food. (SN1)

People can influence me to eat halal food. (SN2)

My family members prefer halal food. (SN3)

My friends think that I should choose halal food. (SN4)

Perceived Behavioral Control

(Karijin et al., Citation2007)

It is easy to find halal food in Pakistan. (PBC1)

There are many choices of halal food at my University. (PBC2)

I always have a chance to eat halal food. (PBC3)

The price of halal food is reasonable. (PBC4)

Religiosity

(Salman & Siddiqui, Citation2011)

I believe that there is no God except Allah (SWT). (R1)

I pray regularly five times a day. (R3)

I pay zakat fitrah every year if I fulfill the prescribed criteria. (R4)

I fast regularly in the month of Ramadan. (R5)

I perform/will perform haj when I can afford to do so. (R6)

I try to follow Islam in all matters of my life. (R7)

Behavioral intention to buy halal food

(Sawari & Salwa, Citation2017)

I will eat halal food only. (BIHF1)

I will eat in halal food outlets only. (BHIF2)

I will make sure that the food is halal before I purchase it. (BHIF3)

I will make sure that the food is halal before I consume it. (BHIF4)

I will consume the food if it is prepared using halal ingredients only. (BHIF5)

My behavior relies on my past experiences in the market for my future investment. (BHIF6)

Physical Well-Being

(Sawari & Salwa, Citation2017)

I have the energy and vitality to do everyday tasks with ease. (PWB1)

I am getting good sleep. (PWB2)

A healthy diet can improve energy, brain, and sleep. (PWB3)

Halal food promises good health and will keep you protected from diseases. (PWB4)

Halal food can develop a stronger immune system. (PWB4)

I am maintaining a healthy weight. (PWB5)

I am having a healthy lifestyle such as healthy eating. (PWB6)