Abstract

This study analyzes the relationship between emotional competencies and entrepreneurial intention of students from public higher education institutions in Ecuador, supported by an extended model of Ajzen’s Theory of planned behavior. The results are derived from a questionnaire applied to students of last semester of careers with academic business training. To analyze the results, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used. The findings show that emotional competencies are significant factors in the configuration of entrepreneurial intentions and have a direct and positive relationship with the cognitive antecedents of entrepreneurial attitude and self-efficacy. It is suggested that students with a higher degree of emotional competencies cope in a better way with the cognitive bias that can make it difficult to recognize business opportunities. The main contribution of this study was to give generality to the results that have been obtained in the use of emotional competencies to promote the intentionality of entrepreneurship in the context of emerging economies.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Entrepreneurship intention, with an emphasis on emotional factors, is evidenced as a segment of relevance for the development and economic growth of countries around the world. This work proposes a framework based on the Theory of Planned Behavior to estimate the analytical thinking of emotional competencies and how they influence the creation of new companies by university students of careers with business and business academic training. This study reveals that entrepreneurial spirit is favored by the development of emotional competencies due to their direct influence on the configuration of entrepreneurial intention and suggests that students with a higher degree of emotional competencies will be more capable of becoming entrepreneurs. In addition, the study can be used as a parameter to improve business education programs by training emotionally competent students in universities mainly in emerging countries.

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurial intentions are studied as one of the most confident predictors of business behavior that results in the creation of new companies (Linan, Citation2004; Prodan & Drnovsek, Citation2010; Souitaris et al., Citation2007). Cognitive characteristics are valuable elements that allow studying entrepreneurial intention, but they are not always enough, because entrepreneurship implicitly contains an emotional component (Cardon et al., Citation2012). The influence of emotional processes on cognition has been observed in a wide range of business contexts, affecting people, processes and organizations (George & Brief, Citation1992; Weiss et al., Citation1999), including decision-making (Souitaris et al., Citation2007) Emotional processes can be related to judgment and behavior (Cohen, Citation2005) and are of great importance to help understand business opinions, decisions and actions when they occur under conditions of uncertainty (Baron, Citation2008). It has been shown that certain areas of the brain are adapted to cognitive and emotional mechanisms, that is, to the ability of an individual to make personal judgments to make decisions and also to express their feelings (Bechara et al., Citation2007). Baron (Citation2008) established the value of emotions as a variable of interest in the study of entrepreneurship, since this factor influences many aspects of cognition and behavior. Because the environments in which entrepreneurs operate are unpredictable emotional problems can have important effects on important aspects of business work. It is difficult to separate rational and emotional perspectives because emotions have an impact on cognitively processed information and subsequent behavioral inclinations (Welpe et al., Citation2012). The framework suggested by Hayton and Cholakova (Citation2012) obtained from Vroom’s expectation theory of motivation (Vroom, Citation1964) and the theory of planned behavior of Ajzen (Citation1991) will give a more complete understanding of how the emotional process can be related with entrepreneurial intentions and recognize that these can also significantly lower the uncertainty in the accuracy, convenience and feasibility at the time of start a business (Dimov, Citation2007).

According to Kamalian and Fazel (Citation2011) with greater emotional intelligence, individuals have a better behavior on environmental pressures, which in turn allows them to recognize feelings that may disappoint them but they have the ability to regulate them, increasing the level of their entrepreneurial behavior. Moreover, individuals with higher emotional intelligence have higher emotional feelings that allow them to develop their creativity and be proactive in getting out of adverse circumstances, as well as playing a relevant role in the creation of entrepreneurial behavior. In other words, the higher the emotional intelligence, the greater the probability of being an entrepreneur (Zampetakis et al., Citation2009).

Interest in the emergence of entrepreneurial intention has stimulated research in the area of entrepreneurship (Bird & Allen, Citation2006). The literature dedicated to examining the main factors related to entrepreneurial intention suggests that the personality traits of individuals determine their intentions to start a business (Pradhan & Nath, Citation2012) but little consideration is given to emotional factors in emerging countries since knowledge on this issue has only been generated in developed countries. In addition, research that examines the emotional factors in the creation of companies is quite limited (Fernández-Pérez et al., Citation2017; Padilla-Meléndez et al., Citation2014). The knowledge achieved by the relationships of emotional competencies in entrepreneurial intentions is partial because the population studied is only limited to populations from developed countries (Montes, Citation2018).

People with a high level of entrepreneurial intention could regulate their own emotions (George & Brief, Citation1992), showing emotional competencies that can foster an orientation towards the business environment (Padilla-Meléndez et al., Citation2014). This study focuses on emotional competencies and not on emotional intelligence because competences, unlike intelligence, show that people are capable of turning their potential into reality in a particular context (Boyatzis & Saatcioglu, Citation2008). So, emotional competencies become a practical application of emotional intelligence. Based on this, the present study aims to focus on emotional competencies and their relationship with entrepreneurial intention of students from public higher education institutions in Ecuador, supported by an extension of the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991; Fernández-Pérez et al., Citation2017; Padilla-Meléndez et al., Citation2014). An emotional-cognitive perspective reinforced by an extended model of Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991) was taken to study the relationship of emotional competencies and cognitive factors (self-efficacy, entrepreneurial attitude and subjective norms) with entrepreneurial intention.

The present study aims to cover the research gap detected in academic literature about the importance of emotional competencies to obtain a better explanation of the entrepreneurial intention (Fernández-Pérez et al., Citation2017; Padilla-Meléndez et al., Citation2014). The study will respond to the recommendation of other researchers who showed the need to cooperate with a better understanding of the relationship between cognitive factors (subjective norms, entrepreneurial attitude and self-efficacy) and emotional competences (Ajzen, Citation1991; Fernández-Pérez et al., Citation2017; Liñán, Citation2008; Padilla-Meléndez et al., Citation2014). For this reason, an extended model of Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior with the integration of emotional competencies will be important in order to achieve a greater understanding of entrepreneurial intention in students of higher education institutions.

In the next section the theoretical foundation of the research is detailed together with the hypotheses, the research methodology, the findings and finally the conclusions, implications and future research.

2. Theoretical framework and hypotheses

Entrepreneurship includes an emotional component (Baron, Citation2008). Previous research has shown that personal antecedents and characteristics such as personality, motivation, values, skills and attitudes induce people to have an entrepreneurial behavior (Collins et al., Citation2004; Rauch & Hulsink, Citation2015; Stewart & Roth, Citation2015). Zampetakis et al. (Citation2009) found that workers with a more pronounced emotional intelligence, that is, those who are more capable of regulating, supervising and evaluating both their own emotions and emotions of others, have a better disposition to act in an entrepreneurial way and perceive higher levels of organizational support. However, emotional intelligence is defined as the capacity in which emotions are recognized, understood and used in oneself and that allows effective performance (Boyatzis & Saatcioglu, Citation2008); and for many researchers the term emotional competence is better since, unlike emotional intelligence, competencies can be taught and learned (Padilla-Meléndez et al., Citation2014). This term refers to how people identify, express, understand, regulate and use their emotions and those of others (Cherniss & Goleman, Citation2005; Goleman, Citation1998). For the purpose of this study, emotional competencies are defined as the interrelated set of behaviors that people use to identify and manipulate both their own emotions and emotions of others.

Emotional competencies can play a critical role in predicting entrepreneurship (Padilla-Meléndez et al., Citation2014). In this framework, the main emphasis is placed on the interactions of individuals with the business environment, as well as personal development and learning (Boyatzis & Saatcioglu, Citation2008). Goleman (Citation1998) pointed out “emotional competence” as the ability to learn which is based on emotional intelligence that results in exceptional performance in the workplace. Studies in graduate students have proposed that emotional competencies play a fundamental role in the decision to become an employer (Goleman, Citation1998; Padilla-Meléndez et al., Citation2014) and may be more effective predictors of performance than general personal identity traits (Finch et al., Citation2015; Guillén-Ramo et al., Citation2009).

Entrepreneurial intentions are defined as a conviction of an individual to create a new business and consciously plans to do so at some point in the future (Thompson et al., Citation2010). Students who exhibit greater entrepreneurial intentions will also present higher emotional competencies because these play a fundamental role in the prediction of entrepreneurship (Fernández-Pérez et al., Citation2017; Padilla-Meléndez et al., Citation2014; Souitaris et al., Citation2007). It is difficult to separate the emotional from the rational aspect because emotions are related to the impact of processed cognitive information on later behavioral tendencies (Welpe et al., Citation2012). According to Rausch et al. (Citation2011), the practical application of emotional competences becomes a strategy for the development of the individual’s and organization’s ability to assess the impact and consequences of decisions, while simultaneously improving the quality and effectiveness of the decision-making process. Based on this affirmation w could conclude that emotional competence strengthens business attitudes and increases the possibility that an individual starts a business career (Souitaris et al., Citation2007). As individuals with strong emotional competencies present stronger business attitudes towards entrepreneurship, they can be more productive and creative, less risk-averse and more likely to adopt positive business attitudes (Fernández-Pérez et al., Citation2017).

Based on these arguments, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Emotional competencies have a direct and positive influence on entrepreneurial intention.

On the other hand, according to Bandura (Citation1997), self-efficacy is the belief in the ability to reinforce motivation, to use the cognitive resources available and take the necessary actions to face the specific demands of each business reality. Self-efficacy is present in people with greater emotional intelligence, who have greater self-confidence and greater control of business demands (Wong & Law, Citation2002), do not give up when problems arise and do not delay challenges (Mikolajczak, Citation2009). Individuals who tend to expel the feelings that destroy them also have a high degree of self-confidence, are able to recognize their own feelings, and have a stronger entrepreneurial spirit (Welpe et al., Citation2012). In this context, emotional competencies act as the emotional motivator that activates business competencies such as the intention to take risks, open up to opportunities or have a more creative outlook and better plan the future of entrepreneurship. Individuals with positive emotional competencies will cope better with stress, will be more self-confident and will have more control over the creation of a company such as identifying opportunities and solving problems (Mikolajczak, Citation2009), factors related to self-efficacy. Individuals with strong emotional competencies experience greater self-satisfaction, are more confident and have a mental perspective that favors individual productivity (Padilla-Meléndez et al., Citation2014).

Emotions has a strong influence with the characteristics of achieving goals and objectives in organizations, and with the significant relationships in the performance measured towards the achievement of goals and effectiveness in tasks in the work environment. Some dimensions of emotional intelligence for example, are significantly related to the perception of entrepreneurial self-efficacy; individuals who have developed emotional competencies are more likely to generate successful ventures. It can then be concluded that people with high emotional intelligence believe in their entrepreneurial abilities, and perceive themselves with more and better opportunities in carrying out business activities, in regulating and applying emotions that are positively interrelated with entrepreneurial self-efficacy (Nabi et al., Citation2018). So:

H2: Emotional competencies have a direct and positive influence on self-efficacy.

Entrepreneurial attitude is identified as the degree to which an individual is predisposed or not to start entrepreneurial activities Regarding the entrepreneurial phenomenon, although some research has verified the influence of emotional competencies in shaping entrepreneurial intentions through its effect on entrepreneurial attitude (Krueger et al., Citation2000), little is known about the relationship of the emotional competencies in business attitude. However, individuals who act as entrepreneurs display entrepreneurial attitudes that are generally the result of their emotions and motivations (Gray et al., Citation2006). Indeed, it has been mentioned that emotional competence strengthens business attitudes and increases the possibility that an individual will subsequently start a business career (Souitaris et al., Citation2007). As individuals with strong emotional competencies present stronger business attitudes towards entrepreneurship, they can be more productive and creative, less risk-averse and more likely to adopt positive business attitudes (Fernández-Pérez et al., Citation2017). So:

H3: Emotional competencies have a direct and positive influence on business attitude.

The theory of planned behavior has been one of the most widely used theories in terms of explaining and predicting the behavior of individuals. The theory of planned behavior has been cited more than 5000 times on the Web of Science since Icek Ajzen’s book was published in 1988 and his article in 1991 (Lortie & Castogiovanni, Citation2015). The theory of planned behavior is preceded by intentions to put behavior into operation and the perception of control over said behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991). In addition, the intentions of individuals are determined by components such as: business attitudes, subjective norms and self-efficacy. The subjective norms, in the context of this study, refer to the influence exerted on the entrepreneurial intention by the reference persons (Ajzen, Citation1991), family members, friends and colleagues, all of whom can play a decisive role in the determination of an individual to enter business activity (Chang et al., Citation2009). Entrepreneurship studies have shown the existence of a direct and positive influence between subjective norms and entrepreneurial intention (Carr & Sequeira, Citation2007; Engle et al., Citation2010; Karimi et al., Citation2016; Kolvereid & Isaksen, Citation2006; Usaci, Citation2015). So:

H4: Subjective norms have a direct and positive influence on entrepreneurial intention.

On the other hand, Bae et al. (Citation2014) pointed out that self-efficacy is one of the most powerful components in entrepreneurial intention. Similarly, Nowiński et al. (Citation2019) emphasized how self-efficacy is of utmost importance in the development of entrepreneurship among students of higher education institutions. Karimi et al. (Citation2016) similarly found that among university students the component of self-efficacy is the strongest predictor of entrepreneurial intention. García-Rodríguez et al. (Citation2015) reported that self-efficacy is one of the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention. Yurtkoru et al. (Citation2014) found that self-efficacy, among other components, predicts entrepreneurial intention. So:

H5: Self-efficacy has a direct and positive influence on entrepreneurial intention

The majority of entrepreneurship studies have affirmed that entrepreneurial attitude could predict entrepreneurial intention and subsequent entrepreneurial behavior, so that a direct and positive relationship is established between them (Iakovleva et al., Citation2011; Moriano et al., Citation2014; Usaci, Citation2015; Yurtkoru et al., Citation2014; Zhang et al., Citation2014). It is also mentioned that students with a higher grade in this area will feel more confident in their ability to recognize an opportunity to start a business at an early stage or to take risks in the business field (Kickul et al., Citation2009). The importance of the entrepreneurial attitude suggests that people will be more willing to dedicate resources and time in this field (Schwarz et al., Citation2009). Some authors have found that entrepreneurial attitude has little or no effect on entrepreneurship in specific contexts where individuals show lower levels of inclination to entrepreneurial activity and where labor dependency is emphasized especially in the female gender (Bagozzi, Citation1992; Krueger & Brazeal, Citation1994; Vamvaka et al., Citation2020). This study will examine the direct and positive effects of entrepreneurial attitude on entrepreneurial intention. So:

H6: The entrepreneurial attitude has a direct and positive influence on the entrepreneurial intention

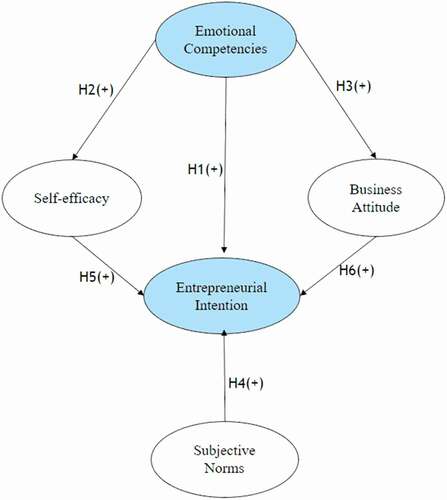

The model submitted for confirmation is shown in .

Exploring the academic literature provided the existence of a research gap related to the analysis of emotional competencies within the theory of planned behavior. Integrating the role of emotional competencies in the model that explains the entrepreneurial intention will contribute to broadening the current knowledge reported by the traditional Ajzen model. Therefore, this situation led to investigate the effect that emotional and cognitive components have on entrepreneurial intention in students of higher education institutions in Ecuador.

3. Method

The present research performs the analysis of data that comes from a simple and valid stratified sample of 693 students enrolled in the last two semesters of business careers. Students of these levels were chosen due to the proximity to obtain their academic degree and with the objective of evaluating the level of entrepreneurial intention that has been developed during their training process. The data was obtained from a survey application to students from public higher education institutions in Ecuador who gave the corresponding authorization. Business degree students were selected since, according to the educational model implemented in the country, the students of these careers have a training focused on entrepreneurship and generation of new businesses. The career coordinators and teachers provided the facilities and the time necessary to carry out the study. Regarding the characteristics of the sample, 31.7% are men and 68.3% are women. To verify the assumptions of multivariate analysis, a normality analysis was performed, obtaining a Mardia coefficient of 41.113 and, according to Bentler (Citation2005), a coefficient greater than 5 indicates that the data do not follow a normal distribution at the multivariate level. To verify the linearity, the Pearson correlation coefficients between the exogenous and endogenous variables added through an arithmetic average were used according to the process written by Hayes (Citation2017). All the correlations were positive and significant, thus demonstrating compliance with the linearity assumption. Also, homoscedasticity was verified, which according to Hair et al. (Citation2010) is performed through residual scatter graphs which must be normally distributed. shows that the standardized residuals are normally distributed in the dependent variable through all the independent variables.

4. Instruments

Each variable was measured through instruments previously validated in other contexts. To measure entrepreneurial intention, the instrument proposed by Liñán and Chen (Citation2009) was used in its version adapted and validated into Spanish by Rueda et al. (Citation2015), with four items. This instrument allows predicting whether university students will consider starting their own business through three components: subjective norms with three items that evaluate how external people would support their business career options; the entrepreneurial attitude with three items that measures the positive or negative entrepreneurial attitudes of university students and the self-efficacy with five items that measures elementary aspects for people’s belief in the ability to create an enterprise. All the items of the instrument used a Likert scale with seven levels of measurement.

On the other hand, emotional competencies were evaluated with the instrument proposed by Cherniss and Goleman (Citation2005) validated by Fernández-Pérez et al. (Citation2017). This instrument distinguishes five groups of emotional competencies: self-awareness with three items, self-regulation with three items, motivation with five items, empathy with five items, and social skills with five items. All the items of the instrument used a Likert scale with seven levels of measurement.

Prior to the application of the measurement instruments, a content validation was carried out through a panel of five experts: 3 academic experts and 2 professional experts with experience in the area. These people evaluated both the writing, the relevance and the meaning of each of the items of the measurement instrument. Afterwards, a pilot test was carried out on a sample of undergraduate students who were not considered in the study sample. This process allowed to identify possible problems in the interpretation or inconsistency in it. Finally, the internal consistency analysis was carried out by calculating the composite reliability index for each construct proposed by Chión and Vincent (Citation2016), obtaining values greater than 0.7.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Measurement Model

Within this analysis, in the first instance, the reliability analysis was carried out through the composite reliability index that analyzes the consistency of the scales in the items, taking into consideration the factor loadings of the observable variables on the underlying constructs. shows the composite reliability index for each latent variables. All the constructs have a value greater than 0.70, which allows to conclude that the scales have a high level of reliability and consistency

Table 1. Reliability of the scales of each construct

The model fit was evaluated through the CFI, RMSEA, Chi-Square test, and CMIN-DF index, which according to Kline (Citation2016) should be reported. In addition, the GFI, NFI, TLI and AGFI index proposed by Chión and Vincent (Citation2016) are also reported. Given that in evaluation of normality it was possible to verify that the model follows a non-normal distribution, the bootstrapping technique proposed by Byrne (Citation2009) and included in the AMOS Software was used, together with the Bollen–Stine test to verify the fit. When running the model in the first instance, it did not present a good fit, so according to the procedure described by Byrne (Citation2009) the modification indices were verified. The results obtained led to correlate the error variances of some constructs respecting the coherence and relevance of each of them with its underlying latent variable, doing a prior verification of the text of the related questions. shows the goodness-of-fit indices of the structural model.

Table 2. Goodness-of-fit indices of the structural model

Subsequently, the analysis of the convergent and discriminant validity of measurement model was carried out. This model includes correlations between all the constructs. To assess convergent validity, the procedure established by Chión and Vincent (Citation2016) was used. shows that some factor loadings are lower than the established minimum of 0.75; however, when reviewing the reliability indices, it is observed that in all cases is greater than 0.75, so these measurements are marginally acceptable in each one of the constructs.

Table 3. Convergent validity of the sub-constructs and items

The evaluation of discriminant validity was made according to the procedure established by Chión and Vincent (Citation2016) through a statistical t-student test, stablishing as a null hypothesis that correlation between each of the constructs is equal to 1. Each t student test was compared with the critical value equal to 1.964 or −1.964 by symmetry of the t-student distribution, at a significance level of 0.05 with 567 degrees of freedom. According to , all the test statistics were lower than the critical value, leading to rejecting the null hypothesis that the correlations are equal to 1, fulfilling the discriminant validity criterion.

Table 4. Discriminant validity

5. Structural model

This section shows the results of structural model analysis. Chión and Vincent (Citation2016) pointed out that these models focus their interest on estimation and statistical validation of the relationship between latent variables. Emotional competencies were specified as a Second-Order Model with five Subconstructs: (a) self-awareness, (b) motivation, (c) empathy, (d) social skills, and (e) self-regulation. It impacts on the first-order construct entrepreneurial intention. All other variables were specified as first-order models. SPSS version 25 and AMOS version 24 software were used for all data analysis.

Model fit was evaluated through the CFI, RMSEA, Chi-Square test, and CMIN-DF index, which according to Kline (Citation2016) should be reported. In addition, the GFI, NFI, TLI and AGFI index proposed by Chión and Vincent (Citation2016) are also reported. Given that the evaluation of normality improved that the model follows a non-normal distribution, the bootstrapping technique proposed by Byrne (Citation2009) was used together with the Bollen–Stine test to verify the fit. Collier (Citation2020) specified that 5000 bootstrap samples must be specified with 95% confidence intervals. When running the model in the first instance, it did not present a good fit, so according to the procedure described by Byrne (Citation2009) the modification indices were verified. The results obtained led to correlate error variances of some constructs respecting the coherence and relevance of each of them with its underlying latent variable doing a prior verification of the text of the related questions. shows the goodness-of-fit indices of the structural model.

Table 5. Goodness-of-fit indices of structural model

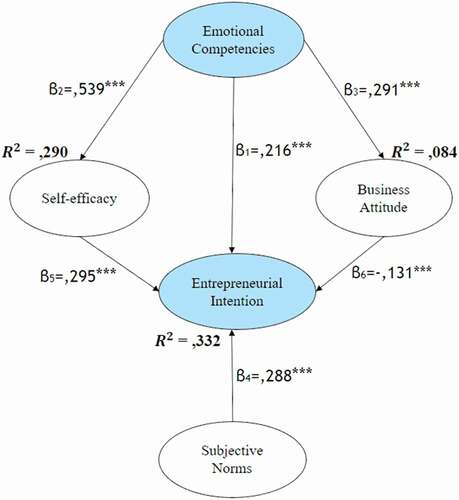

The chi-square test indicator (ᵪ ^ 2) was equal to 1554.416 with p value of 0.002, a value lower than the 0.02 cut-off point, so the model would not be accepted if it were verified only with this test. However, according to Byrne (Citation2009), it is necessary to evaluate the fit with other indicators. Therefore, a GFI goodness-of-fit indicator is shown, in which a value of 0.888 was obtained, which is very close to the 0.9 cut-off point, and the RMSEA, which has a value of 0.049, which is within the acceptance range of the model. The indices CFI, TLI and NFI present values within accepted levels. The CFI obtained was 0.932, a value within the acceptance range required by the model. The TLI is 0.927, which is also within the acceptance range required by the model. The NFI is 0.897 and is slightly below the 0.9 cut-off point, meaning an important percentage of adjustment of the model. Finally, the AGFI and CMIN/DF indicators also comply with the model’s acceptance rules. The AGFI has a value of 0.871 higher than the 0.8 cut-off point. The CMIN/DF has a value of 2,685 which is within the acceptance range of the model. According to the fit indices obtained, most are within the required range, except for the GFI and NFI index, which are very close to the values required by the model, so it can be concluded that the model shows an acceptable adjustment since there is no solid evidence to reject the model. Most of the dependent variables of the model show multiple R ^ 2 greater than 0.1, such as self-efficacy with 0.290 and entrepreneurial intention with 0.332, that is, the model explains more than 10% of the variances of each of the factors. As can be seen, the only variable that does not satisfy the Falk and Miller (Citation1992) criterion is the entrepreneurial attitude that shows a variance of 0.084 less than 0.1, the minimum required criterion. The standardized loads of the structural model are shown in .

With regard to the regression parameters estimated between the latent variables, shows that emotional competencies positively and significantly influence entrepreneurial intention (0.216, p-value <0.05), that is, students who develop emotional competencies are more capable of creating new businesses. This finding supports hypothesis 1. Emotional competencies show a significant effect with self-efficacy (0.539, p-value <0.05), that is, students’ self-confidence can be strengthened if they develop emotional competencies. This finding supports hypothesis 2. Similarly, emotional competencies show a significant effect with entrepreneurial attitude (0.291, p-value <0.05), that is, students who perceive stronger emotional competencies will have an entrepreneurial attitude towards the most effective entrepreneurship, therefore, this finding supports hypothesis 3. The subjective norms show a direct and positive relationship with the entrepreneurial intention (0.288, p-value <0.05), that is, the reference persons such as family members and friends of the students influence their entrepreneurial behavior, supporting hypothesis 4. In the same way, self-efficacy shows a direct and positive relationship with entrepreneurial intention (0.295, p-value <0.05), that is, students who believe in their cognitive abilities and resources will be more likely to face the business environment. This finding supports the Hypothesis 5. On the other hand, entrepreneurial attitude has a non-significant effect with entrepreneurial intention (−0.131, p-value <0.05) that is, entrepreneurial attitude is absent or is the weakest predictor among students from institutions of public higher education in Ecuador. This finding allows us to reject hypothesis 6. Given a non-significant direct effect between two latent or unobservable variables, it necessarily entails the absence of influence (Hair et al., Citation2010), so an analysis of the effect was carried out direct, indirect and total between the emotional competences and the entrepreneurial intention. shows the result of this test, which reveals that the direct effect 0.216 is greater than the indirect effect 0.121 and the total effect of emotional competencies on entrepreneurial intention is 0.337.

Table 6. Regression between constructs of the structural model

Table 7. Standardized direct and indirect effects of the structural model

6. Discussion and conclusions

The results confirm that emotional competencies are significant factors in the configuration of entrepreneurial intentions in students of business careers. Consequently, governments, university authorities and teachers should consider these competencies as the main factor in the development of study programs in public higher education institutions in Ecuador, which will lead to better fulfill the objectives in the area of entrepreneurship. This study provided an interesting framework to understand the entrepreneurial intentions of students and the effectiveness of careers with business academic training in public higher education institutions, focusing on cognitive and emotional factors and their relationships, taking into account that it would be important to obtain an emotional–rational balance in the decision-making process in the business area. The extended model of the theory of planned behavior in students of public higher education institutions in Ecuador indicates that the development of emotional competencies could promote their entrepreneurial intentions as a result of the positive relationship of emotional competencies in self-efficacy and attitude. business. Therefore, it is suggested that greater the emotional competencies, the more likely students are to have the intention to start a business because their cognitive antecedents such as subjective norms and self-efficacy are directly related to entrepreneurial intentions. Emotional competencies provide highly valued attributes helping students to face the cognitive bias that can make it difficult to recognize business opportunities, overconfidence, and false control (Padilla-Meléndez et al., Citation2014). So the presence of emotional competencies facilitates business intention. It was attractive to contrast emotion versus cognition in Ecuador, so this study shows a new vision about the duality of the decision-making process in the business environment.

Regarding the relationship between emotional and cognitive factors in entrepreneurial intention, the results of the present study are consistent with those found in previous studies and reflect the positive influence of emotional competencies on entrepreneurial intention (Cardon et al., Citation2012; Fernández-Pérez et al., Citation2017; Malebana, Citation2014; Montes, Citation2018; Padilla-Meléndez et al., Citation2014); emotional competencies on self-efficacy (Goleman, Citation1998; Mikolajczak, Citation2009; Padilla-Meléndez et al., Citation2014); emotional competencies on business attitude (Gray et al., Citation2006; Souitaris et al., Citation2007; Welpe et al., Citation2012); subjective norms on entrepreneurial intention (Ajzen, Citation1991; Carr & Sequeira, Citation2007; Engle et al., Citation2010; Karimi et al., Citation2016; Kolvereid & Isaksen, Citation2006; Usaci, Citation2015); self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intention (Ajzen, Citation1991; Karimi et al., Citation2016; Krueger et al., Citation2000; Liñán, Citation2008; ; Yurtkoru et al., Citation2014). An important finding was that entrepreneurial attitude does not have a significant influence on entrepreneurial intention, confirming the findings reported in studies by Bagozzi (Citation1992); Krueger and Brazeal (Citation1994), so that entrepreneurial attitude is the weakest predictor of entrepreneurial intentions among students of public higher education institutions in Ecuador, which contrasts with findings in other countries (Engle et al., Citation2010; Kolvereid & Isaksen, Citation2006; Moriano et al., Citation2014; Yurtkoru et al., Citation2014; Zhang et al., Citation2014). In emerging countries such as Ecuador, cultural influences are primary factors and according to the attitude-belief theory, cultural values are probably influenced by business attitudes (Iakovleva et al., Citation2011). The Ecuadorian students surveyed may think that an entrepreneur can generate favorable income and that it is a good profession, they may feel that they are limited in terms of future personal growth (Luiz, Citation2011). Vamvaka et al. (Citation2020) mentions that gender is an important moderator of entrepreneurial intention and that men are stronger when conceiving nascent entrepreneurship as business behavior and it should be noted that this study has a valid sample of 693 Ecuadorian university students in careers of business academic training where 31.7% are men while 68.3% are women. Therefore, the entrepreneurial attitude should be encouraged by university teachers through teaching-learning methodologies that improve their emotional competencies motivating the entrepreneurial attitude. Therefore, it is important that public higher education institutions in Ecuador not simply disseminate entrepreneurial skills, but also encourage emotional competencies in each of their students so that they can accept moderate risks, undertake economic and social plans that facilitate change and improve the benefit of the Ecuadorian community in general.

7. Implications

Several authors have studied the consequences of emotions in the area of entrepreneurship such as Cardon et al. (Citation2012), but few have investigated the effect of emotional competencies, a concept that encompasses the ability to admit, control emotions and make functional use of them in different environments. In this research, the importance of the integration of emotional competencies in the model that describes entrepreneurial intentions in the Ecuadorian context prevailed, noting that it is important to estimate that for individuals to have entrepreneurial intentions they must realize that they have emotional aspects to do so. In this way, these individuals will have positive intentions to become entrepreneurs. An implication of this finding is the fact of not separating emotional competencies in the study of entrepreneurship since this makes it possible to distinguish the degree of control that individuals have of their emotions in relation to the result that is expected to be obtained from the activities that are demolished from entrepreneurship in Ecuadorian students. The study shows findings that highlight the value of emotional competencies in entrepreneurial attitude and self-efficacy and not focus only on knowledge and resources for the creation of new businesses. This successful ingredient promotes intentions to increase the interest of the students of Ecuador’s public higher education institutions in the entrepreneurial alternative. Likewise, work must be done in a better way to develop entrepreneurial enthusiasm by fostering the connection between emotional competencies and entrepreneurship. Another interesting implication lies in understanding the effect generated by the entrepreneurial attitude as an assessment that favors or not the behavior in the model that explains entrepreneurial intentions. Precisely, the findings allow to conclude that the entrepreneurial attitude or the degree to which an individual is inclined or not to start a business activity, does not positively influence the entrepreneurial intentions of the students of public higher education institutions in Ecuador. Such connection is obviously weakly developed or absent; in this regard, the development of a collaborative framework between academia and the business world could lead to the conduction of motivational strategies that allow them to develop their emotions and better promote their business attitudes. Finally, another implication is the methodological contribution that was established when addressing the case of Ecuador in order to apply an extension of the model of the theory of planned behavior of Ajzen (Citation1991) including emotional competences in contexts of emerging countries taking into account that studies have only been carried out in developed countries, so this research allows us to generalize the understanding of how emotional competencies influence entrepreneurial intentions in students of public higher education institutions in Ecuador. This study collaborates with appropriate information for people who develop, implement and evaluate educational schemes in Ecuador aimed at strengthening the entrepreneurial intentions of students, apart from training in business areas, pay close attention to their emotional factors.

8. Future research

A line of research that could spread would be to investigate how the individual emotional factors of competencies are related to entrepreneurial intentions and their precedents in the context of emerging countries. At present, the study schemes of the careers with business and business academic training of the higher education institutions in Ecuador tend to be reinforced towards operational skills rather than entrepreneurial motivation tasks. On the other hand, given that the present research did not show a significant effect of the entrepreneurial attitude on the entrepreneurial intentions of Ecuadorian university students in careers with business and business academic training, it is recommended as a future line of research to evaluate the role that exerted by university teachers and people who are representatives of successful entrepreneurship cases in university students with the aim of contributing models of influence that facilitate a culture around entrepreneurship.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Oswaldo Verdesoto Velástegui

Oswaldo Verdesoto completed his Bachelor in Administrative Sciences. Has an Engineering in Banking and Finance; a Master Degree in Strategic Business Management from the Technical University of Ambato (UTA) in Ecuador and his Doctoral Candidacy in Strategic Business Administration at CENTRUM Catholic Graduate Business School - Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Lima. He was Director of the XIV Engineering Graduation Seminar “Productivity and Quality” for 4 years. In addition, he has been a Professor in Undergraduate and Graduate programs at the Faculty of Administrative Sciences of the UTA for the last 19 years. Also, he had worked as General Administrator, Graduate Coordinator, Dean and Interim Vice-Dean at the Faculty of Business Sciences of the UTA. He has published ten articles in national and international magazines. Now he is Professor and Academic and Administrative Director of Postgraduate Programs at the Faculty of Administrative Sciences at UTA (Ecuador).

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 25(2), 179–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Bae, T. J., Qian, S., Miao, C., & Fiet, J. O. (2014). The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta-analytic review. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 38(2), 217–254. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12095

- Bagozzi, R. (1992). The self-regulation of attitudes, intentions and behavior. Social Psychology Quarterly, 55(2), 178–204. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2786945

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freemann & Co.

- Baron, R. A. (2008). The role of affect in the entrepreneurial process. Academy of Management Review, 33(2), 328–340. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2008.31193166

- Bechara, A., Damasio, A., & Bar-On, R. (2007). The anatomy of emotional intelligence and implications for educating people to be emotionally intelligent. Educating People to Be Emotionally Intelligent, 273–290. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5772/32468

- Bentler, P. M. (2005). EQS 6 structural equations program manual (C. M. S. Encino, ed.). http://www.econ.upf.edu/~satorra/CourseSEMVienna2010/EQSManual.pdf

- Bird, B. J., & Allen, D. N. (2006). Faculty entrepreneurship in research university environments. The Journal of Higher Education, 60(5), 583. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1982268

- Boyatzis, R. E., & Saatcioglu, A. (2008). A 20-year view of trying to develop emotional, social and cognitive intelligence competencies in graduate management education. Journal of Management Development, 27(1), 92–108. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710810840785

- Byrne, B. (2009). Structural equation modeling with AMOS (2nd ed.). Taylor and Francis Group.

- Cardon, M. S., Der Foo, M., Shepherd, D., & Wiklund, J. (2012). Exploring the heart: Entrepreneurial emotion is a hot topic. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 36(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00501.x

- Carr, J. C., & Sequeira, J. M. (2007). Prior family business exposure as intergenerational influence and entrepreneurial intent: A theory of planned behavior approach. Journal of Business Research, 60(10), 1090–1098. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.12.016

- Chang, E. P. C., Memili, E., Chrisman, J. J., Kellermanns, F. W., & Chua, J. H. (2009). Family social capital, venture preparedness, and start-up decisions. Family Business Review, 22(3), 279–292. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486509332327

- Cherniss, C., & Goleman, D. (2005). Inteligencia emocional en el trabajo. In Barcelona: Kairós.

- Chión, S., & Vincent, C. (2016). Analitica de Datos para la Modelación Estructural. Pearson.

- Cohen, J. D. (2005). The vulcanization of the human brain: A neural perspective on interactions between cognition and emotion. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(4), 3–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1257/089533005775196750

- Collier, J. E. (2020). Applied structural equation modeling using AMOS: Basic to advanced techniques. Routledge.

- Collins, C., Hanges, P., & Locke, E. (2004). The relationship of achievement motivation to entrepreneurial behavior: A meta-analysis. Human Performance, 17(1), 95–117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327043HUP1701_5

- Dimov, D. (2007). Beyond single-person, single-insight attribution in understanding entrepreneurial opportunities. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(5), 713–731. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2007.00196.x

- Engle, R. L., Dimitriadi, N., Gavidia, J. V., Schlaegel, C., Delanoe, S., Alvarado, I., He, X., Buame, S., & Wolff, B. (2010). Entrepreneurial intent. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 16(1), 35–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/13552551011020063

- Falk, R. F., & Miller, N. B. (1992). A primer for soft modeling. In University of Akron Press. Elsevier.

- Fernández-Pérez, V., Montes-Merino, A., Rodríguez-Ariza, L., & Galicia, P. E. A. (2017). Emotional competencies and cognitive antecedents in shaping student’s entrepreneurial intention: The moderating role of entrepreneurship education. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 15(10), 1–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-017-0438-7

- Finch, D., Peacock, M., Lazdowski, D., & Hwang, M. (2015). Managing emotions: A case study exploring the relationship between experiential learning, emotions, and student performance. International Journal of Management Education, 13(1), 23–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2014.12.001

- García-Rodríguez, F. J., Gil-Soto, E., Ruiz-Rosa, I., & Sene, P. M. (2015). Entrepreneurial intentions in diverse development contexts: A cross-cultural comparison between Senegal and Spain. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(3), 511–527. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-013-0291-2

- George, J. M., & Brief, A. P. (1992). Feeling good-doing good: a conceptual analysis of the mood at work-organizational spontaneity relationship. Psychological Bulletin, 112(2), 310–329. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.2.310

- Goleman, D. (1998). Working with emotional intelligence. Bantam Books.

- Gray, K. R., Foster, H., & Howard, M. (2006). Motivations of moroccans to be entrepreneurs. Journal of Developmrntal Entrepreneurship, 11(4), 297–318. http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/S1084946706000507

- Guillén-Ramo, L., Saris, W. E., & Boyatzis, R. (2009). The impact of social and emotional competencies on effectiveness of Spanish executives. Journal of Management Development, 28(9), 771–793. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710910987656

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson.

- Hayes, A. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications.

- Hayton, J. C., & Cholakova, M. (2012). The role of affect in the creation and intentional pursuit of entrepreneurial ideas. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 36(1), 41–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00458.x

- Iakovleva, T., Kolvereid, L., & Stephan, U. (2011). Entrepreneurial intentions in developing and developed countries. Education and Training, 53(5), 353–370. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911111147686

- Kamalian, A., & Fazel, A. (2011). Discussing the relationship between IE and students entrepreneurship. Entrepr. Dev, 3(11), 127–146.

- Karimi, S., Biemans, H. J. A., Lans, T., Chizari, M., & Mulder, M. (2016). The impact of entrepreneurship education: A study of iranian students’ entrepreneurial intentions and opportunity identification. Journal of Small Business Management, 54(1), 187–209. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12137

- Kickul, J., Gundry, L. K., Barbosa, S. D., & Whitcanack, L. (2009). Intuition versus analysis? Testing differential models of cognitive style on entrepreneurial self-efficacy and the new venture creation process. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 33(2), 439–453.

- Kline, R. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Kolvereid, L., & Isaksen, E. (2006). New business start-up and subsequent entry into self-employment. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(6), 866–885. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.06.008

- Krueger, N., & Brazeal, D. (1994). Entrepreneurial Potential and Potential Entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(3), 91–104. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879401800307

- Krueger, N., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5–6), 411–432. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(98)00033-0

- Linan, F. (2004). Intention-based models of entrepreneurship education. Piccola Impresa/Small Business, 3, 11–35.

- Liñán, F. (2008). Skill and value perceptions: How do they affect entrepreneurial intentions?. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 4(3), 257–272. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-008-0093-0

- Liñán, F., & Chen, Y. (2009). Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00318.x

- Lortie, J., & Castogiovanni, G. (2015). The theory of planned behavior in entrepreneurship research: What we know and future directions. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(4), 935–957. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-015-0358-3

- Luiz, J. (2011). Entrepreneurship in an emerging and culturally diverse economy : A South African survey of perceptions. SAJEMS NS, 14(1), 47–65. DOI:https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v14i1.30

- Malebana, M. (2014). Entrepreneurial intentions of South African rural university students : A test of the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Economics and Behavioural Studies, 6(2), 130–143. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.22610/jebs.v6i2.476

- Mikolajczak, M. (2009). Going beyond the ability-trait debate : The three-level model of emotional intelligence an unifying view : The three-level model of EI. Electronic Journal of Applied Psychology, 5(2), 25–31. DOI:https://doi.org/10.7790/ejap.v5i2.175

- Montes, A. (2018). Competencias emocionales en el analisis de la intención emprendedora del Alumnado Universitario: Implicaciones para la educacion en emprendimiento. Universidad de Granada.

- Moriano, J. A., Molero, F., Topa, G., & Lévy Mangin, J. P. (2014). The influence of transformational leadership and organizational identification on intrapreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 10(1), 103–119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-011-0196-x

- Nabi, G., Walmsley, A., Liñán, F., Akhtar, I., & Neame, C. (2018). Does entrepreneurship education in the first year of higher education develop entrepreneurial intentions? The role of learning and inspiration. Studies in Higher Education, 43(3), 452–467. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1177716

- Nowiński, W., Haddoud, M. Y., Lančarič, D., Egerová, D., & Czeglédi, C. (2019). The impact of entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and gender on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in the Visegrad countries. Studies in Higher Education, 44(2), 361–379. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1365359

- Padilla-Meléndez, A., Fernández-Gámez, M. A., & Molina-Gómez, J. (2014). Feeling the risks: Effects of the development of emotional competences with outdoor training on the entrepreneurial intent of university students. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 10(4), 861–884. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-014-0310-y

- Pradhan, R. K., & Nath, P. (2012). Perception of entrepreneurial orientation and emotional intelligence: A study on India’s future techno-managers. Global Business Review, 13(1), 89–108. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/097215091101300106

- Prodan, I., & Drnovsek, M. (2010). Conceptualizing academic-entrepreneurial intentions: An empirical test. Technovation, 30(5–6), 332–347. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2010.02.002

- Rauch, A., & Hulsink, W. (2015). Putting entrepreneurship Education where the intention to Act lies: An investigation into the impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial behavior. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 14(2), 187–204. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2012.0293

- Rausch, E., Hess, J. D., & Bacigalupo, A. C. (2011). Enhancing decisions and decision‐making processes through the application of emotional intelligence skills. Management Decision, 49(5), 710-721.

- Rueda, S., Moriano, J., & Liñan, F. (2015). Validating a theory of planned behavior questionnaire to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Developing, Shaping and Growing Entrepreneurship, (February), 60–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784713584.00010

- Schwarz, E. J., Wdowiak, M. A., Almer-Jarz, D. A., & Breitenecker, R. J. (2009). The effects of attitudes and perceived environment conditions on students’ entrepreneurial intent: An Austrian perspective. Education and Training, 51(4), 272–291. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910910964566

- Souitaris, V., Zerbinati, S., & Al-Laham, A. (2007). Do entrepreneurship programmes raise entrepreneurial intention of science and engineering students? The effect of learning, inspiration and resources. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(4), 566–591. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.05.002

- Stewart, W. H., & Roth, P. L. (2015). A meta-analysis of achievement motivation differences between entrepreneurs and managers. Journal of Small Business Management, 45(4), 401–421. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2007.00220.x

- Thompson, P., Jones-Evans, D., & Kwong, C. C. Y. (2010). Education and entrepreneurial activity: A comparison of white and South Asian men. International Small Business Journal, 28(2), 147–162. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242609355858

- Usaci, D. (2015). Predictors of professional entrepreneurial intention and behavior in the educational field. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 187, 178–183. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.03.034

- Vamvaka, V., Stoforos, C., Palaskas, T., & Botsaris, C. (2020). Attitude toward entrepreneurship, perceived behavioral control, and entrepreneurial intention : Dimensionality, structural relationships, and gender differences. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 9(1), 2-26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-020-0112-0

- Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation. Wiley & Sons.

- Weiss, H. M., Nicholas, J. P., & Daus, C. S. (1999). An examination of the joint effects of affective experiences and job beliefs on job satisfaction and variations in affective experiences over time. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 78(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1999.2824

- Welpe, I. M., Spörrle, M., Grichnik, D., Michl, T., & Audretsch, D. B. (2012). Emotions and opportunities: The interplay of opportunity evaluation, fear, joy, and anger as antecedent of entrepreneurial exploitation. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 36(1), 69–96. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00481.x

- Wong, C., & Law, K. S. (2002). The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: An exploratory study. The Leadership Quarterly, 13(3), 243–274. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00099-1

- Yurtkoru, E. S., Kuşcu, Z. K., & Doğanay, A. (2014). Exploring the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention on Turkish university students. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 150, 841–850. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.09.093

- Zampetakis, L. A., Kafetsios, K., Bouranta, N., Dewett, T., & Moustakis, V. S. (2009). On the relationship between emotional intelligence and entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 15(6), 1355–2554. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/13552550910995452

- Zhang, Y., Duysters, G., & Cloodt, M. (2014). The role of entrepreneurship education as a predictor of university students’ entrepreneurial intention. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 10(3), 623–641. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-012-0246-z