Abstract

The abuse of transfer pricing by multinational enterprises (MNEs) is a topical issue the world over. Abusive transfer pricing results in the erosion of tax bases and profit shifting from countries with high tax rates to those with lower tax rates, thus enabling tax avoidance and evasion. Developing countries are argued to suffer most under the negative impacts of transfer pricing manipulation. This study investigates the strategies employed by MNEs to minimise their tax burden in developing countries. An understanding of the motives and strategies is fundamental in tax policy crafting and improvements that effectively respond to transfer pricing. Adopting the interpretivist research philosophy with the use of in-depth interviews with tax officers, tax consultants and Ministry of Finance Officials, the study established that amongst the transfer pricing schemes used by MNEs in Zimbabwe, the predominant one was the use of service fees. The most notable being management fees, this was a contribution to knowledge as this strategy was found to be scarcely discussed in literature and there was very little empirical evidence to back its existence. The study recommended use of targeted approaches by the revenue authority to minimise revenue losses through intragroup services. The findings serve as vital information for policymakers, revenue authorities and tax auditors.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Harnessing of domestic revenues is an important task for the functionality and survival of any government. However, TP motives and strategies may obstruct such revenue mobilisation efforts. Tax base attrition through TP remains a formidable challenge particularly in developing countries. This study provides interesting insights regarding the dominant TP strategies implemented by MNEs and possible ways to ameliorate the unfavourable outcomes. The study, therefore, serves as an important contribution to both theory and practice as it provides insights for the formulation of targeted approaches as opposed to misdirected approaches by policy makers and tax authorities. This exposition helps them devise targeted ways of dealing with these strategies especially with regard to the “use of management fees” as the widely used TP strategy.

1. Introduction

Globalisation is one of the noteworthy features of modern-day businesses. To maintain a competitive and sustainable upper hand in the globalised village, companies have embarked on expansion and diversification endeavours that have taken their activities across borders; hence, the emergence and growth of MNEs. MNEs are important players on the global platform. Beebeejaun (Citation2019) state that MNEs and their associated enterprises were approximated to account for a tenth of the global GDP and their sales were estimated at half of the world GDP. Their growth was argued to be faster than the average growth of the world economy’s GDP. Sixty percent of trade by MNEs is contended to be transactions that occur within group setups. The prices of these transactions are always a subject of controversy, they cannot be verified in many instances and are mostly not at arm’s length or not even based on market transactions. “This is the greatest irony of free market economies: a substantial proportion of world trade (that occurring within MNCs) is not governed by prices set by the market” (Bhat, Citation2009, p. 1).

Gašić et al. (Citation2014, p. 38) advance that the dominance of intercompany commerce by MNEs in certain industries is subject to abuse of power. In exercising market power and dominance MNEs tend to structure the transactions and exchanges between their affiliates, parent and subsidiaries in such a way that tax liability is avoided or minimised by moving profits and incomes from jurisdictions with high tax rates to those with low tax rates. Governments need to understand the transfer pricing (TP) abuse strategies so that they can be fully equipped to curb them or mitigate their impact on the economy (Cooper et al., Citation2017). Harnessing of domestic revenues is an important task for the functionality and survival of any government and tax collection is fundamental to such revenue mobilisation attempts. Tax base attrition poses a formidable challenge to most nations irrespective of whether they are developing or developed nations. The consensus among development scholars is that developing countries suffer most from the losses and effects of base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) (Cooper et al., Citation2017; Mashiri, Citation2018; McNair et al., Citation2010; Oguttu, Citation2016, Citation2017). As posited by the UNCTAD (Citation2020), losses attributable to illicit flows due to transfer pricing abuses, mis-invoicing and mispricing of trade transactions, corruption and other activities towards tax avoidance and evasion are projected at nearly 3.7% of Africa’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and at around US$89 billion annually (US$30 billion to 52 billion attributed to trade mis-invoicing), a figure that constitutes almost the total of the development aid and foreign direct investment that the African continent receives to cover its needs. Reiterating the gravity of the problem, Kabala and n.d.ulo (Citation2018) posit that nearly 60% of trade transactions departing from the African continent are mispriced by approximately 11% on average, resulting in a forecasted capital flight of about 7% of African trade. In light of this, several questions arise such as, how does the continent lose so much money? What are the strategies employed by MNEs to move money from the developing countries through TP? What can be done by developing countries and especially the African countries to reduce the magnitude of transfer pricing exploitation and abuse?

Transfer pricing provides “a façade of legality for the shifting of profit from one jurisdiction to another, low-tax jurisdictions as a normal course of business events” (Bhat, Citation2009, p. 1). The importance of countries coming up with efforts or measures to curb tax driven TP in the globalised business world cannot be overemphasised. Developing countries need to augment their policy measures to protect tax bases and minimise tax revenue losses and leakages. This was reiterated by Beebeejaun (Citation2019) who points out that, it is crucial for developing countries to have some measure or way of balancing their desire for foreign direct investment and internal trade with regulations that effectively control these activities to address TP abuses and distortions. An understanding of the avenues and means used to manipulate TP is an important step in trying to address the challenges of BEPS. An appreciation of the strategies used to shift profits from one jurisdiction to another would inform policy prescriptions and decisions employed to address the growing challenges of TP abuse. Bhat (Citation2009, p. 20) acknowledges the need to closely pay attention to issues of TP by highlighting that “plugging holes caused by tax-related transfer pricing poses theoretical as well as practical problems”. The extant literature provides evidence of transfer pricing manipulation by MNEs (Beebeejaun, Citation2019; Asongu, Citation2016; Cooper & Nguyen, Citation2020; Reidel, Citation2018), but details of how it is exploited (strategies used to achieve this) remain unexplored (Abdul et al., Citation2016). Stressing the importance of understanding TP issues, Sundaram (Citation2012, p. 1) avers that TP is considered as a “Financing for Development” issue because in the absence of adequate tax revenues and failure to collect the rightfully deserved taxes, a country’s propensity to generate domestic funds for development is obstructed.

Transfer pricing is argued to have a detrimental impact for developing countries, not only does it lead to BEPS problems, but it aids tax avoidance, robbing these countries of entitled tax revenues to fund economic development, infrastructure, health, education and poverty alleviation efforts. This study was motivated by the need for equity and neutrality in pricing decisions so as to avoid distortions in income allocation and taxing rights. It is vital that taxing rights are rightful and fairly allocated because such decisions have impacts on multiple arenas. In addition, curbing Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs) is a component of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) target 16.4 for promoting peace and justice as well as building strong institutions. The need for fulfilment of this SDG by developing the heightened interest on TP by both developed and developing countries, the prominent featuring of the issue in development agendas and tax administration forms as well as the negative impact of tax evasion and avoidance on economies piqued the researchers’ curiosity and concern on the TP strategies and possible ways to ameliorate the unfavourable outcomes, thus this study aims to make a contribution to policy and practice. The study also adds to the paucity in knowledge in relation to TP manipulation strategies and TP in general as the area is still in its nascent stages of development and remains underexplored. This paper consists of five sections. The next section reviews literature on transfer pricing in order to give a contextual background to the study. Section 3 outlines the methodological journey for the study, while Section 4 presents the findings of the study and accompanying discussions. Section 5 is the penultimate section and it gives the conclusions, limitations and recommendations of the study as well as highlighting areas of further research.

2. Literature review

This section reviews relevant and related literature on transfer pricing. The idea is to give a picture of the research area on and show the current body of knowledge in the area as well to contextualise the study in light of identified research gaps. TP has been an issue of concern for policymakers, revenue authorities and academics over the years, with early works (Bhat, Citation2009; Cianca, Citation2001; McNair et al., Citation2010; Sikka & Willmott, Citation2010) and recent studies (Barrogard et al., Citation2018; Cooper et al., Citation2017; Kabala & n.d.ulo, Citation2018; Oguttu, Citation2016, Citation2017). Mashiri (Citation2018) avows that although the concept is not novel, currently researchers are still in the early stages of unpacking the specifics of the notion, such as schemes of TP, TP regulation enactment and the impact of TP in developing countries. In short, TP is still an emerging area that is worthy of research. Therefore, this research can contribute to addressing both policy and theoretical voids in the TP context. The section focuses on four aspects: the definition of TP (2.1), the motives for TP (2.2), the strategies used to manipulate TP (2.3).

2.1. TP definition and discussion

The definition of TP and its motives have been contested among researchers. Hirshleifer (Citation1956, p. 172) defines TP as the “pricing of goods and services that are exchanged (between autonomous profit-centre divisions) within the firm”. To shed more light on the applicability of TP to MNEs, Florence (Citation2016) describes the nature of MNEs by saying “The nature of MNEs is an integrated business group which consists of associated affiliates in other countries, under common control, with common goals and sharing a common pool of resources”. The affiliates are often run as profit centres, the group profit is an outcome of the profits from the different affiliates. The outcry on TP is not that they sell to each other but the fact that due to their related nature, their prices are not at arm’s length but determined by market forces, company politics, the need for goal congruence, negotiations and other issues such as to “optimize the tax arrangement and minimise tax paid” by the MNEs (Florence, Citation2016, p. 63). Sikka and Willmott (Citation2010) adduce that TP affects economic decisions of MNEs as they impact on earnings, dividends, share prices and investment returns such as return on investment and return on capital. Cooper (Citation2000) on the other hand describes TP as a strategic tool used by MNEs for goal congruence, decision-making and for moving profits from one company to another or from one tax jurisdiction to another in order to exploit the tax advantages. Despite considerable research being in existence on TP (Cugova & Cug, Citation2019), of late, TP has become a subject of intense debate and scrutiny among policy makers, tax authorities, MNEs and government authorities because of its role in capital flight, base erosion, tax evasion and unethical tax avoidance. This is affirmed by Klassen et al. (Citation2017, p. 456) who express that “However more recently within accounting, economics, and law literature interest in transfer prices has focused on them as a tool for multinational firms to reduce global taxes”. Boyce and n.d.ikumana (Citation2012) describe the extent of capital flight in Sub Saharan Africa and attribute part of it to tax evasion and avoidance by MNEs through TP.

Reiterating the renewed focus on tax-motivated TP, Hassett and Newmark (Citation2008, p. 208) allude to this tax-driven TP as “the practice of multinational corporations of arranging intra-firm sales such that most of the profit is made in a low tax country”. A similar definition is given by Beebeejaun (Citation2019, p. 208) who states that “the ability to relocate profits and expenses within enterprises comprised of a group is known as transfer pricing”. Uyar (Citation2014) argues that MNEs employ TP to meaningfully achieve maximisation of profits, but is quick to point out that TP might have detrimental outcomes for the nation that has lost its possible tax revenues to another during the process. Florence (Citation2016)) explicates the term in relation to the setting of prices for transactions occurring between affiliated companies for goods and services such assets (tangible and intangible) and technical services. The prices are often negotiated based on efficiency considerations, economies of scale and country by country tax rates and hence not at arm’s length (Cianca, Citation2001). OECD (Citation2012)) submits that TP by itself is not wrong or detrimental to economies but what becomes destructive is what they term “abusive TP”. Abusive transfer pricing is the unethical or wrong allocation of revenue and expenses with the main aim of lowering the taxable income and this often results in BEPS (OECD, Citation2012). The OECD (Citation2013) describes BEPS as “tax planning strategies that exploit gaps and mismatches in tax rules to make profits ‘disappear’ for tax purposes or to shift profits to locations where there is little or no real activity but taxes are low, resulting in little or no overall tax being paid”. According to Asongu (Citation2016:4), TP is part of rational asymmetric development and this is tantamount to “unfair practices of globalisation adopted by advanced nations to the detriment and impoverishment of less developed ones”. In agreement, Asongu (Citation2016) states that MNEs use TP in a “process of wealth retentiveness which enables corporations to avoid taxes and ease capital flight”. The researcher further explains the negative effects of such TP in Sub-Sahara Africa.

TP has far-reaching impacts for developing countries as compared to developed countries. Illicit financials flows from corruption, transfer mispricing and mis-invoicing, money laundering and organised crime in Africa were estimated at US$40 billion in 2014, US$60 billion in 2015 (Donnelly, Citation2015) and US$89 billion in 2020 (UNCTAD, Citation2020). The pattern shows a substantial increase in revenues losses. Donnelly (Citation2015) further alludes to the fact that 65% of IFFs can be attributable to commercial transactions including those from MNEs, 30% to crime and 5% to corruption. Trade mis-invoicing and TP are argued to be the biggest contributors to the 65% linked to commercial activities, contributing 67,4% of the portion of IFFs during the period 2003 to 2012. If the funds lost through IFFs were retained, the GDP of the continent would have grown by 15%. Commenting on the negative impact that manipulative transfer pricing has on domestic revenue mobilisation, economic development and infrastructural development, Stiglitz (Citation2008) described the way in which MNEs are levied tax as “repulsive, inequitable and inefficient”. The researcher further argues that TP robs developing countries of funds for health, education and development. Walsh (Citation2015) suggests that the globalised nature of MNEs accords them with a “free rein to move their money around the low cost-jurisdictions”. Asongu (Citation2016) allude to the fact that from year 2000 if transfer pricing abuses were curbed and all the saved revenues invested in the health sector more than 350,000 children’s lives could have been saved. This is worsened by the vulnerability of developing countries due to taxpayer knowledge deficiencies (Sebele-Mpofu & Chinoda, Citation2019), information asymmetry, inadequate expertise and experience to deal with TP issues (Beebeejaun, Citation2018; Mashiri, Citation2018). Reiterating the magnitude of the losses through IFFs, Fofack and n.d.ikumana (Citation2010) submit that if only a quarter of the IFFs lost in SSA were repatriated back, domestic investment would be enhanced by 19% to 35%. Asongu and Kodila‐Tedika (Citation2017) attribute the extreme poverty and the failure to achieve the Millennium Development goals of minimising poverty to inadequate revenue mobilisation that is compounded by abusive TP which leads to massive IFFs robbing the country of developmental funds. Offering a compatible opinion, Nkurunziza (Citation2012) declares that TP contributes to social impoverishment through tax evasion and avoidance as well as income shifting. Summing up the impact of abusive TP on developing countries, Stiglitz adduces that abusive TP undermines the social and economic fibre of a country”.

The UNCTAD (Citation2020) highlights the extensiveness of the revenue losses in the African continent specifically due to transfer mispricing as well as due to illicit financial flows in general. Oguttu (Citation2016, Citation2017) re-affirms the problem of BEPS in African countries and highlights the necessity for African countries to pay a close attention to the issue of TP, have an appreciation of the strategies and assess the applicability of the OCED transfer pricing guidelines the African context and to contextualise them to national contexts. An analogous recommendation was submitted by Kabala and n.d.ulo (Citation2018) for African tax authorities, governments and policymakers to use platforms like the African Tax Administration forum (ATAF) and other regional blocks to share notes and experiences on the challenges of TP and to work towards establishing African TP guidelines. The researchers also advocated for more research on TP issues and the progress in the application as well the effectiveness of TP rules in the African context on national levels.

Florence (Citation2016) also sheds more light on the tax-motivated TP explaining that “transfer pricing concealed in the form of cross-border transactions: including but not limited to acquisitions, joint ventures, supply chains-impedes the movement of trade and capital, even catalyses a tax distortion”. Due to significant tax revenue losses, TP has become a topical issue for tax authorities across the globe (Cooper et al., Citation2017; Klassen et al., Citation2017; Walton, Citation2019). Enhancement of domestic revenue mobilisation and consolidation of tax bases in developing countries and African countries in particular cannot be overemphasised (Asongu, Citation2016), the question is how to do so without dis-incentivising foreign investors leading to a decline in foreign direct investment (FDI), developmental assistance and international trade. An understanding of TP strategies is imperative for developing countries’ policymakers to achieve this fundamental objective. It is upon this realisation, that this research sought to explore the tax motivated transfer pricing strategies and ways of mitigating their unfavourable impacts.

2.2. The motives for TP

The heightening of corporate power and increased international trade has opened numerous loopholes for tax avoidance TP schemes, leaving developing countries vulnerable to the effects of TP abuses. Several researchers have bemoaned the single-minded focus on TP as an apparatus for tax minimisation, tax evasion and avoidance while blatantly disregarding its other uses (J. Blouin et al., Citation2011; J. L. Blouin et al., Citation2018; Scholes et al., Citation2014). TP can be used for several reasons, such as: as a tool for decentralisation and coordination, business decisions and goal congruence attainment (J. Blouin et al., Citation2011; Padhi, Citation2019; Walton, Citation2019). Acknowledging the diversity in the motives of TP among MNEs, Beebeejaun (Citation2018) points out that MNEs diversify and expand globally in order to repeat benefits of economies of scale, efficiency as well as to take advantage of the tax rates differences. Profits and expenses can be relocated from one jurisdiction to the other so as to lower the overall tax liability. From this submission three tax motives become evident, the managerial motive or the efficiency motive, government policy induced motive and tax planning and avoidance motive. The first two would be briefly described but not discussed. The interest of this paper focuses on the tax-motivated TP that leads to tax revenue leakages and deprivation. The tax planning and avoidance motive is the bone of contention among researchers, policy makers, revenue authorities, governments and tax experts and tax lawyers, hence it is the one that is extensively discussed in this study.

2.2.1. The efficiency and the government induced motives

As highlighted, it would be an unfair or unbalanced discussion to solely attribute TP manipulation to the tax minimisation motives and totally ignore the other possible motives. The internal efficiency motive could be anchored on the desire to balance the incentives, reporting and keep track of activities within the group in order to achieve goal congruence (Bhat, Citation2009; Reuter, Citation2012). Practical matters under consideration could include performance evaluation of profit centres, avoidance or minimisation of disputes due to transfers among affiliated companies as well as rewarding managers of foreign affiliates in ways that motivate them as well as achieving a common goal of group profit maximisation. The government policy induced on the other hand could be linked to risk assessment (for example policy, political, exchange and currency risk) or taking advantage or responding to government regulations such as repatriation laws, tax holidays and incentives (Reuter, Citation2012). Tax holidays are argued to be a motivation for TP manipulation especially if they are such that for a given period the company can only pay tax if it makes a certain profit. Companies can ensure that through manipulating expenses and incomes through selling of goods and services between them and their other MNE affiliates the company incurs losses or does not reach the taxable threshold until the tax holiday is over. TP can also be a reaction to currency risk, forced joint ventures, policy risk such as unstable and constant changes in regulations, laws and contracts. For example, where the currency is weak under invoice inbound transfers and over invoice outbound transfers. For political risk over-invoice inbound and under-invoice outbound transfers (Reuter, Citation2012).

2.2.2. Tax motivated TP

Globalisation has resulted in contemporary angles in the TP activities (Sikka & Willmott, Citation2010). Global production has equally availed novel and expansive routes of TP schemes to aid in tax avoidance, minimisation of tax obligations and outright profit shifting (Asongu, Citation2016). The global tax environment brings so many uncertainties, different tax incentives, deductions and exemptions, various tax legislations and their varied interpretations as well as differences in tax rates across different jurisdictions. These variations leave scope for MNEs to exploit the ambiguities and differentials that arise from the tax systems of different countries through TP (Beebeejaun, Citation2018, Citation2019; Mashiri, Citation2018), hence the term tax-motivated TP. Corporate power, complexity of MNEs transactions and the extent of globalisation has worsened the problem of TP in recent years. Production and exchange networks have become more intricate (Asongu, Citation2016). Firstly, domestic companies have now both multinational and transnational predispositions. Secondly, foreign companies partner with domestic corporates through joint ventures, new companies, associates and at times fictitious companies (Asongu, Citation2016). This has made tax-driven TP strategies more sophisticated and complex.

Tax motivated TP decisions tend to border on whether to produce and where to export and/or import (Can we produce in the MNE’s home country or where the subsidiary is based?). Conditions that prevail in the home and foreign nations where the parent or subsidiary are sited, are used to inform these decision (McNair et al., Citation2010). TP is often at the core of this decision with the aim to maximise profits and minimise tax liability. Bhat (Citation2009) tabulates in , the decisions that can be taken based on the fact that, tax differentials are assumed between the countries where the parent is located and where the subsidiary is based. For example, in this case, the foreign nation where the latter is located has higher tax rates than where the former is situated. The decisions for profit maximisation would crystallise themselves as shown in .

Table 1. TP decisions when a parent company is located in a lower tax jurisdiction and subsidiary in a higher tax one

As displayed in , various transactions can be subjected to TP. According to Merle et al. (Citation2019), TP relates to the monetary value linked to cross-border transactions between affiliated enterprises. Exchanges involved could be transfers of tangible and intangible assets, services such as research and development, human resources and accounting services, and financial transaction (loans issued to related parties of which interest is charged and paid by another affiliate). These could be manipulated as presented in , making sure the lower tax jurisdiction situated companies charge those in higher tax jurisdictions for goods and services and possibly inflate the prices (overprice or over-invoice). Due to different or similar tax regulations some countries enter into double taxation agreements (DTAs) to cater for incomes that are taxed twice, once in the home country and once in the host country. Other DTA’s give tax credits for the foreign tax paid or the lower of the two taxes as is the case in Zimbabwe on withholding taxes on income (Income Tax Act, 23:06, Section 98), when computing the tax liability. Therefore, TP can be used to minimise both the corporate tax and customs duty paid. For example, understating the value of imports to a subsidiary in a high import duty jurisdiction will lower the value of the imported goods and ultimately the customs duty paid. This has a beneficial after affect also on the cost of sales or inputs, thus increasing the profits of the subsidiary of the subsidiary. How capital and profits are repatriated is also influenced by policies prevailing in each nation and TP manipulations are often set in response to these policies to either circumvent or take advantage of them. Such restrictions on profits or dividends repatriations as well as re-investment conditions might lead to tax motivated TP (Bhat, Citation2009). For example, TP might be used in two ways. Firstly, as highlighted in , where the parent is in a low tax jurisdiction, efforts can be made to ensure that profits or taxable income is moved from the high tax jurisdiction country of the subsidiary. Secondly, a challenge may emerge as to how to repatriate larger cash reserves created from the TP activities, where the low tax jurisdiction now has cash if the repatriation costs are high or the repatriation laws are not favourable (Walton, Citation2019). In response to the repatriation hurdles, the MNEs may seek to move the profits through TP, maybe in the form of goods and services being sold to other low tax jurisdictions. In some cases, management fees might be under-priced or overpriced depending on which one is beneficial as highlighted in .

2.3. Strategies used to manipulate TP

Several benefits accrue to MNEs due to international trade, such business growth and expansion, increased job opportunities, technological transfers amongst jurisdictions, research and development, information exchanges, economic growth and enhanced tax revenues (Cooper et al., Citation2017; Silberztein, Citation2009). MNEs seek to maximise on these benefits and their group profits, ensuring that they minimise their tax obligations as much as possible (Walton, Citation2019). To achieve these conflicting objectives of maximisation of global profits and global tax minimisation, MNEs engage in several tax evasion and avoidance strategies that rob developing countries largely of their envisaged and rightful tax revenues. The level at which MNEs manipulate TP to minimise tax liability cannot be estimated with certainty, but several strategies have been used to employ TP as a tool for tax reduction (Klassen et al., Citation2017). The researchers further point out that notwithstanding the fact that TP is linked to aggressive tax avoidance and profit shifting, there is a paucity in direct empirical evidence for tax-induced transfer pricing and the role of TP in global tax minimisation continues to be “elusive” (Klassen et al., Citation2017, p. 459). The resultant effect is to reduce the tax paid by moving income or profit from higher tax jurisdiction to lower tax jurisdiction. Therefore, such TP results in BEPS as the profit allocation and tax liability of the company is distorted. The company in the high tax jurisdiction has lost part of its profits and consequent tax revenues to the lower tax jurisdiction. Tax authorities view TP with negativity due to income and tax distortions as at times the taxable income is disproportionately moved to the lower tax jurisdictions or tax havens. TP is not illegal but becomes unethical when it aids tax avoidance. Due to TP mispricing, tax evasion and avoidance as well as profit shifting may be enabled. Practical and policy challenges confront tax administrators and authorities. The former hurdle emerges when tax administrators try to correctly or definitively gather enough, detailed and relevant data from MNEs’ transactions occurring outside their territory due to information asymmetry and lack of cooperation. The latter arises when government seeks to draft policies that ensure their countries rightly tax income generated, received or accrued within their jurisdiction. TP affects the tax base by shifting deductible expenses to high tax jurisdictions to lower the taxable profits or move revenues to lower tax jurisdictions to lower the tax liability (Beebeejaun, Citation2018; Bhat, Citation2009). It is therefore imperative to understand the strategies employed by MNEs to engage in TP manipulation, over or under-pricing of intra-firm or intragroup transactions and how these aid tax evasion or circumvention of government regulations. Researchers have pointed to strategies that include, thin capitalisation, TP manipulation, tax haven utilisation, payment for intangibles and technical expertise, income shifting and the used of debt to finance subsidiaries and affiliates. Transfer misinvoicing is considered the main method used to achieve the seemingly conflicting objectives of profit maximisation and minimisation of the tax paid. Depending on the motive to be achieved, TP manipulation can be either through overpricing or under-pricing as displayed in .

Table 2. Actions taken by MNEs to achieve various objectives of TP through mispricing

In addition to transfer mispricing discussed above, the TP strategies are discussed in detail in the subsections that follow.

2.3.1. Income shifting through under or over-invoicing

Income shifting basically explains what is illustrated in . The concept involves a reduction in the selling price or circumstances whereby the price is inflated to give an advantage to MNEs, thus shifting the profits from one jurisdiction to another (Uyanik, Citation2010). Mashiri (Citation2018) alludes to income shifting as the manipulation of prices by related companies to exploit tax differentials, hence moving profits from where they could be taxed highly to where they cannot be taxed or taxed less. Reiterating the issue of mispricing transfers by MNEs to avoid tax by shifting the tax base to where it is exposed to less tax. Merle et al. (Citation2019) advances that MNEs tend to manipulate the values of TP by overvaluing payments to higher tax jurisdictions and under valuing those to tax friendly environments (for example, charge higher interest rates on loans advanced to companies in higher tax jurisdictions and lower interest to those operating in tax havens or lower tax environments. In acknowledgement, Reuter (Citation2012, p. 212) expresses that MNEs tend to “over-invoice tax deductible inbound transfers to high-tax countries and under-invoice them to low tax-countries”. While studying TP mispricing in the mining industry in Zimbabwe, Kwaramba et al. (Citation2016) alluded to the fact that substantial profits were shifted through under-invoicing of exports and over-invoicing of imports leading to significant tax revenue losses. Various researchers have attributed the bulkiness of manipulative TP activities to take place through income shifting through mis-invoicing (Asongu, Citation2016; Kabala & n.d.ulo, Citation2018; McNair et al., Citation2010; UNCTAD, Citation2020). Reuter (Citation2012) argues that when it comes to intra-firm TP MNEs’ affiliates tend to intra-corporate, that is cooperation driven by the need to maximise the overall MNE profit. The affiliates tend to collude instead of competing in their profit generation endeavours as well as in their pricing decisions, thereby over or under-invoicing to reduce the tax burden or avoid it in some countries through “profit maximising transfer pricing” (Reuter, Citation2012, p. 213). Melnychenko, Pugachevska and Kasianok (Citation2017) while focusing on TP in Ukraine, concluded that TP was not merely exploited through tax planning to achieve tax avoidance, but it can be used for outright tax evasion. The researchers highlighted three scenarios of outright tax evasion: (1) the use of fictitious or “pseudo imports” and these imports are at higher prices and exports at lower prices (2) the generation of baseless value added tax (VAT) credits and illegal VAT offset and evasion using “pseudo or non-typical exports” and pricing them highly (3) the use of fictitious companies.

2.3.2. Debt shifting

This practice involves having related enterprises in high tax jurisdiction overly financed through debt to enjoy the after-tax saving since interest is an allowable deduction, thus reducing the taxable income. For example, the interest rates are inflated in a high tax region so that taxable income is reduced and relatively lower tax is accounted for. The interest becomes income in the low tax jurisdiction and subjected to less tax or no tax depending on the tax legislation (Bhat, Citation2009; Oguttu, Citation2017). Anouar and Houria (Citation2017) found that high financial gearing (use of debt) is positively associated with high tax avoidance, yet the majority of MNEs tend to finance their enterprises with more debt than equity in tax jurisdictions. Oguttu (Citation2017) recommends the use of withholding taxes to reduce the exploitative use of debt through thin capitalisation. This would ensure that those that still try to go past the thin capitalisation ratios by getting banks to give loans to subsidiaries on their behalf or through other means that make companies appear independent and unrelated. Before interest is remitted to the payee the payer has to withhold tax and remit to the tax authority. Van Der Zwan (Citation2017) raises a concern that TP adjustments on the disproportionate interest can lead to an overly burdensome tax liability. Reuter (Citation2012) on the other hand tables that in response to withholding taxes MNEs can decide not to remit the funds as cash but reinvest them and TP them through exports in future or they can assess withholding taxes for dividends, technical fees, training, and management fees and structure their payments in such a way that they pay that which attracts the lowest tax if these tax rates are different. Mashiri (Citation2018) tables that despite countries like Zimbabwe having debt to equity restrictions or thin capitalisation ratios after which excessive interest is prohibited as an allowable deduction, these were exploited by MNEs by overstating equity figures.

2.3.3. Tax havens

Tax havens have been extensively discussed by several researchers in relation to tax avoidance evasion schemes as well as the negative impact they have on economies as they aid in income shifting, money laundering and concealing of monetary transactions and evidence (Christensen, Citation2009; Hearson, Citation2018; Mitchell et al., Citation2002). A tax haven is defined as an autonomous or semi-autonomous state or dominion where regulations are lax, taxes on incomes or assets are low or not there, banking facilities are secretive and there is little cooperation or exchange of information with regulatory authorities of third-party nations (Brown et al., Citation2011). In affirmation, Hearson and Brooks (Citation2010) describe them as dominions that design attractive laws, masks of secrecy in order to draw non-residents and foreign companies to invest or saving their incomes and profits, benefiting from the veils of protection and low taxes. These tax havens have become topical in contemporary discussion and research as part of TP manipulation (Asongu, Citation2016; Cooper et al., Citation2017; Kabala & n.d.ulo, Citation2018; Mashiri, Citation2018). Murphy (Citation2012) argues that nearly 60% of global trade goes through tax havens. Davies et al. (Citation2014) attributes the greater portion of tax avoidance occurring through TP of exports going to tax havens. The researchers estimate that about 1% of total tax collected in France is lost through tax avoidance and the bigger portion of this being through exports to tax havens as they are often under-priced. Taylor et al. (Citation2015) through regression analysis based on 286 publicly listed United States multinational companies conclude that multinationality, tax haven utilisation and intangible assets are significantly positively related with TP aggressiveness. The regression results indicate evidence that shows that firms intensify their vigorous manipulative TP through employing a combination of multinationality, pricing of intangibles and the use of tax havens. The researchers further highlight that the use of tax havens and exploitation of the intangibles are the most economically exploited through TP to perpetuate tax base shifting and tax avoidance. Dyreng et al. (Citation2019) as well as Merle et al. (Citation2019) acknowledge that tax havens offer MNEs with leverage to intensify tax motivated TP and tax avoidance.

2.3.4. Use of intangibles

The use of tangibles in TP has been alluded to by a number of TP researchers, arguing that is because it is difficult to prove that the price at which these intangibles have been transferred are at arm’s length or not. This because in some cases these intangibles will be peculiar to that group as there are no comparable prices or comparable databases available to benchmark (Bhat, Citation2009; Cooper et al., Citation2017; Kabala & n.d.ulo, Citation2018). Revenue authorities in both developing and developed countries battle with proving their cases against MNEs in this area and this leads to it being exploited by MNEs. Reuter (Citation2012) submits that some intra-firm transactions are more “fungible” than others hence they are prone to TP manipulation. For example, the use of cost allocation agreements to share the risks and costs associated with joint developments, designs or production of assets as well as the associated research and development costs. In addition to the challenging nature of establishing the arm’s length cost for intangibles and finding comparable prices hence making them top on the most abused items through TP, Reuter (Citation2012) considers management fees as “particularly notorious” when it comes to being manipulated through TP. Abdul et al., (Citation2016) allude to transparency and lack of cooperation by taxpayers in relationship to information on intangibles as some of the hurdles faced by TP auditors. In Indonesia, Dyreng et al. (Citation2019) found that MNEs enjoyed excessive tax advantages through the exploitation of intangibles.

2.4. Theoretical and conceptual framework

Yin (Citation2011) defines a theory as comprehensive assumptions created to unpack and comprehend phenomena as well as to test and widen available knowledge in the area. For this research, TP was explored from the angle of the rationality or practice theory (Brunsson, Citation1982; Levin & Milgrom, Citation2004; Rouse, Citation2007; Weber, Citation1968). The rationality theory is constructed upon the interactions of social groups with divergent motivations and objectives. In order to achieve their varied intentions, they take advantage of their social standing in relation to social phenomena (Rouse, Citation2007). In this case, taxpayers (MNEs) and revenue authorities (ZIMRA). As postulated by Weber (Citation1968), the rationality theory is anchored on economic actors or stakeholders making decisions that are guided by laws and regulations but without consideration of human standards. The decisions are influenced by bureaucratic settings and capitalist ideologies, whereby profits are the most pivotal objective. Brunsson (Citation1982) posits that rationality is manipulating regulation in order to attain the most advantageous opportunity or results. The actions of taxpayers (tax planning, avoidance and evasion) and revenue officers (tax administration, coercive and persuasive measures) are rational decisions. A rational decision is based on evaluation of possibilities and settling for the one that is more beneficial to the stakeholder (Allingham & Sandmo, Citation1972; Levin & Milgrom, Citation2004). For policy makers decisions have to do with what is best for the government and economy at large (for example, TP legislation, tax legislation, incentives and exemptions, punitive and persuasive measures) and the taxpayers (tax compliance or non-tax compliance as well as tax obligation minimisation decisions).

2.4.1. Conceptual framework

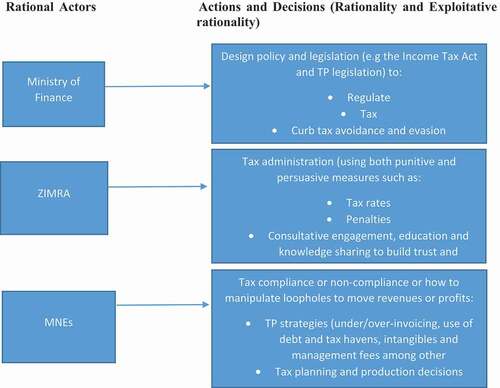

foregrounds the conceptual framework for this study.

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework Rational Actors Actions and Decisions (Rationality and Exploitative rationality)

In this study, the behaviour of taxpayer as individuals or as companies in this case MNEs (the company as a legal persona) are rational economic actions taken after weighing the options, through a cost and benefit analysis. Decisions are taken in the form of TP strategies such as debt issuance, profit shifting and violation of thin capitalisation rules through manipulation, misinvoicing, mispricing and production decisions. The actions are aimed at maximising profits and minimising taxes at the expenses of the disadvantaged nations and their citizens, from whom tax bases and profits are eroded and shifted respectively (Asongu, Citation2016). This reflects the capitalist ideologies and rational economic actor decisions as alluded to by Weber (Citation1968), Brunsson (Citation1982), and Rouse (Citation2007). Tax authorities and the policy makers (Ministry of Finance) on the other hand take rational choices on how to curb TP tax avoidance and evasion strategies that lead to BEPS through tax administration (coercive and synergistic strategies as highlighted by Kirchler et al. (Citation2008)) and through tax policy crafting respectively. The decisions are influenced by the costs (administration and implementation), rewards (incentives and exemptions and their impact to the economy) and punishments (penalties) (Scott, Citation2000). So in arriving at the decisions all the three stakeholders, just like rational economic actors, prioritise their own agendas and interests ahead of others, MNEs (as taxpayers) and ZIMRA and MOF (as regulators). Likewise, tax consultants give precedence to their own good by putting first the needs of their clients (MNEs) ahead of those of the nation or government when giving advice on tax planning and crafting complex TP strategies to the detriment of tax administration. They further pursue their rational actions when dealing with court cases and dispute resolution putting the needs of MNEs ahead of public interest. This was emphasised by researchers who explored the role of accountants in tax avoidance (Jones et al., Citation2018; Mashiri et al., Citation2021; Sikka & Willmott, Citation2013). Rational decisions are built upon three things: the ability to use resources to achieve set targets, allocate resources in an optimal manner that allows the maximisation of their use and lastly self-serving behaviour (Jonge, Citation2012).

3. Research methodology

This research employed the interpretivism research paradigm. This research philosophy is considered relevant for research that addresses new or under-investigated areas as it enables researchers to have deeper knowledge of phenomena being investigated. This philosophical framework views the world as subjective and built socially through the relationships, interactions and actions between various stakeholders (Creswell & Clark, Citation2017; McKerchar, Citation2008; Onwuegbuzie et al., Citation2009). The researcher combined literature review that led to the development of a conceptual framework and qualitative methods of enquiry as tools for secondary and primary data collection. TP is a highly debated current issue among various stakeholders and the attention, understanding of TP strategies and their impact on the economies as well as the application of TP legislation is still in its infancy in developing countries. Research on TP in African countries (Kabala & n.d.ulo, Citation2018) and Zimbabwe in particular is at its nascent stages (Mashiri, Citation2018). Getting an in-depth insight into the TP dilemma through the perspectives of different stakeholders with knowledge on TP was very important for this research; thus, the target population was made up of tax consultants that dealt with MNEs, ZIMRA officers and Ministry of Finance officials in Zimbabwe. The stakeholders were found to be ideal for this research, because owing to the sensitive nature of tax-related information, MNEs could not disclose such information, hence, the reliance on these three groups for their intimate, knowledge, exposure and experience. These are key qualities to consider when sampling to achieve saturation in qualitative research that employs purposive sampling (Sebele-Mpofu, Citation2020b). This study adopted an exploratory research design, which is a design recommended to carry out research in new or under-investigated areas (McKerchar, Citation2008). TP regulation is a new, maiden and fertile area for research. The study adopted a purely qualitative approach to both data gathering and analysis. Qualitative approaches are characterised by small samples especially where purposive and snowballing sampling techniques are used to determine samples. This is because the sufficiency of the sample size is driven by the information richness of participants, hence leading to the saturation point being attained quickly than where the samples is not informational strong and is not homogeneous (Malterud et al., Citation2016; Sebele-Mpofu, Citation2020b). Thus for this study the sample ranged between 3 and 10 participants per stakeholder group (3 for Ministry of Finance Officials, 10 ZIMRA officers and Tax Consultants). The sample enabled in-depth exploration and analysis of data, their intense knowledge helped in reaching the saturation point and their diversity brought a fair and unbiased assessment of TP (Ryan et al., Citation2007; Sebele-Mpofu, Citation2020a). This research collected data through the use of in-depth interviews with the sampled stakeholders from the three groups and complemented it with document a review and analysis of court cases and judgements, TP legislation, previous research, media articles and TP guidelines from the OECD and United Nations. Data were analysed using Atlas ti, employing thematic analysis.

The study also addressed the issues of research quality, validity (often problematic in qualitative research (Sebele-Mpofu, Citation2020b) and ethical consideration. The research addressed the fundamental qualities of qualitative research: credibility, transferability, dependability and trustworthiness (Rosenthal, Citation2016; Vasileiou et al., Citation2018) through seeking opinions of experts on the research instruments, pretesting of interview guides and member checking to gain feedback from participants as suggested by (Ryan et al., Citation2007) and (McKerchar, Citation2008). Ethical considerations were also upheld throughout by getting informed consent after appraising participants of the possible benefits of the study and that no risks or possible harm was anticipated from their participation, that their privacy was going to be respected, confidentiality protected through data coding and that the results were going to be reported as a pool. Additionally, for ZIMRA officers, proof of permission granted to carry out the interviews was availed before each interview in view of the fact that they are bound by an oath of confidentiality and such proof is mandatory for their cooperation.

4. Presentation and discussion of findings

The findings of this research which centred on the participant’s understanding of TP, motives of TP (4.1), strategies used for TP (4.2), proposed solutions (4.3) discussion and implications of results (4.4). The participants were coded for ZIMRA officers as ZIMRA, Tax Consultants as TC and Ministry of Finance Officials as MOF for data analysis and presentation of results. This was also aimed at preserving their anonymity.

4.1. Motives of TP in Zimbabwe

The majority of participants referred to TP as a way used to allocate prices to goods that are sold or exchanged between companies belonging to the same group. The participants were quick to link TP with the loss of tax revenues in Zimbabwe. TC1 described TP as a tool used by MNEs for tax planning in order to minimise the tax paid in Zimbabwe since the country’s corporate tax rate is considered to be high. ZIMRA1 referred to TP as a mechanism employed by MNEs to avoid paying tax by moving profits and incomes from one country to another. MOF1, sharing the same perspective as ZIMRA1, explicated abusive TP as “the purposeful manipulation of the prices at which goods and services are sold between companies under common control or have relationships in such a way that tax payments are avoided or reduced”. What is evident from the discussions is that participants are aware of the concept of TP and their definitions of it reflect their epistemological orientations shaped by their experiences and occupational inclinations. TCs define TP from the tax planning angle while MOFs and ZIMRA officers define it from the tax avoidance and evasion angle, but one commonality is the acceptance by all participants that the objective is tax-motivated (ZIMRA and MOFs 100% pointed to tax motivation while 80% of experts concurred). It was also apparent during the discussions that tax-driven TP was the dominating motive for TP. The results of the TP motives among MNEs in Zimbabwe are presented in .

Table 3. Motives for TP among MNEs in Zimbabwe

It is apparent from the table that the tax-related motive is considered the main motive for TP in Zimbabwe. Despite tax minimisation being prominent motive, participants also agreed on the existence of other motives such as managerial efficiency and decisions aimed at goal congruence especially towards profit maximisation and the influence of government policies on MNEs’ decisions. The influence of government policy was the second most emphasised region with 70% of ZIMRA officials and TCs referring to it, while 60% of the MOF officials also concurred. During the discussion on the three motives, there were topical points under each motive: tax-related motive (profit shifting, reduction of tax obligations, tax planning and sharing of tax obligation, deferment of tax liability tax avoidance and tax evasion) and for efficiency and goal congruence (managerial efficiency, resource allocation and investment decisions versus the returns from the investment as well the need to achieve goal congruence). On government policy the discussion centred on profit repatriation regulations, the payments of dividends, withholding taxes on the repatriated incomes and on policies governing incentives and tax exemptions given to the different sectors of the economy. The majority of participants felt that the mining sector was the most abused through porous government policies and weak commodity pricing. The concerns for the inefficient taxation of the mining sector and significant revenue leakages have been emphasised by researchers in developing countries (Kabala & n.d.ulo, Citation2018; Oguttu, Citation2016; UNCTAD, Citation2020) and in Zimbabwe (Kwaramba et al., Citation2016; Mashiri, Citation2018). Irrespective of the fact that participants alluded to the other two motives, during the discussions it was evident that all the responses to all two motives culminated into tax-driven motivation standing out as the major reason for transfer pricing, with one fundamental goal of profit maximisation and tax payment reduction. For example ZIMRA6 highlighted that “if you look at it lets say, for interest’s sake if a company decides on what to produce and where, it can be a government policy influenced decision or an economic efficiency driven one but there is a tax element that can’t be ignored. When you consider the exchange of goods which are raw materials to another related party, it might be an economic decision to attain goal congruence but elements of mispricing for tax purposes cannot be divorced from the transaction”.

4.2. The strategies employed by MNEs in Zimbabwe

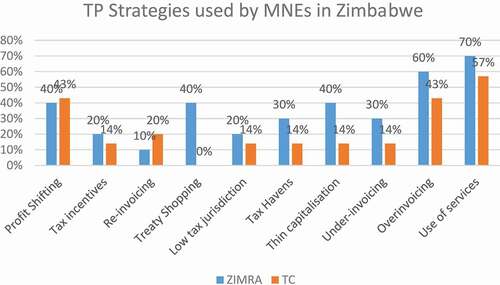

This section summarises the TP strategies that were found to be used by MNEs. These were tabled by participants during the interview discussions and accordingly presents these, in relation to the percentage of participants who believed the strategy was applied in Zimbabwe. The different responses could possibly reflect the different experiences of the tax consultants (during their interaction with MNEs as advisors on tax planning and sometimes on what strategies to apply and when) and the ZIMRA officers in dealing with the issue of TP in Zimbabwe (where the application of the OECD TP guidelines is at is nascent stage as alluded to by Mashiri, Citation2018). Sikka and Willmott (Citation2013) adduce that tax consultants usually know a great deal about the MNEs as they normally advise them and give the expertise on how to engineer the TP schemes in the name of tax planning. Ten TP approaches became evident from the study and these are presented in . The MOF are not included in because they referred the researchers to get more information from ZIMRA as the authority was in a better position to appraise them on the strategies deriving from their tax administration experiences. The officials further highlighted that ZIMRA had a great input in tax legislation crafting as advisors of government regarding tax administration issues.

The TP schemes presented above resonate well with the list of TP approaches put forward by Ruiz and Romero (Citation2011). The researchers allude to such TP tactics to include misclassification of goods and services, mis-invoicing both over and under, thin capitalisation rules exploitation as well the movement of profits and taxable revenues to tax havens. From , it is apparent that most participants from the two stakeholder groups (TCs and ZIMRA officials) pointed to the use of services as the one they believed to be the most prevalent strategy use by MNEs in Zimbabwe (ZIMRA 70% and TCs 57%). This was followed by over-invoicing (ZIMRA 60% and TCs 43%). Thin capitalisation, profit shifting and treaty shopping were the other notable strategies highlighted by 40% of ZIMRA interviewees. For TCs profit shifting was another strategy they believed was fairly used and being pointed by 43% of the interviewees. The strategies would be individually discussed below in order of significance as gleaned from , starting with the use of services followed by mis-invoicing.

4.2.1. Use of services

During the coding process, services were used to refer to issues such as administrative, technical and managerial fees. This would therefore entail that situations where there are transaction between related parties (intra-group transactions) that have to do with management fees, technical fees and administrative fees, these were considered the use of services. These services were argued to leave room for so much TP manipulation as suggested by the majority of respondents in both groups as portrayed in . The respondents referred the fact that the abuse occurred mostly with management services such as technical assistance, consultancy, marketing services and the provision of information technology and systems expertise among related affiliates from MNEs groups. ZIMRA interviewees (ZIMRA, 5, 6, 7 and 8) contended that the management fees were highly distorted in order to ensure that they are inflated in Zimbabwe so that the affiliates operating in Zimbabwe pay more to their parents or sister subsidiaries outside Zimbabwe in order to lower the taxable income in Zimbabwe as the country is argued to have a high corporate tax rate at 24% plus 3% Aids levy (ITA, Zimbabwe, Chapter 23:06). ZIMRA 6 asseverated that “most of the management fees paid by Zimbabwean subsidiaries are not proportionate to the work that would have been rendered, but it is one area where it is difficult for us tax officers to query, how do you prove that these are not commensurated to the services offered”. The finding resonates well with Reuter (Citation2012) who considered management fees to be notoriously open to manipulation. The ZIMRA officers pointed out that the consolation they had was that the management fees are subject to a 15% withholding tax (WHT) and further subjected to remittance fees by the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe as governed by the Banking Act. Even if that does very little to recover the losses suffered through inflated fees, not all is lost. TC 7 expressed that the motivation to manipulate TP through management could stem from the fact that management fees are levied WHT at 15% which is lower than the 24% plus 3% Aids levy charged as corporate tax. Building from Reuter (Citation2012) who expressed that withholding taxes on management fees are normally pegged high at around 30–35%, it can be in order to say the WHT on management fees at 15% charged in Zimbabwe is relatively low and thus perhaps the reason why it is highly exploited in the country. Re-affirming the abuse of management fees, ZIMRA 7 expressed that in some cases the subsidiary operating in Zimbabwe would record technical or training fees payments in their books, yet they cannot show travelling and accommodation expenses for the trainers who came into the country to conduct such training. The ZIMRA officer highlighted that “management would say the training was offered online, it becomes an uphill if not undoable task to prove otherwise that in line with Section 15 (2) of the ITA, Zimbabwe the expense has not been incurred, hence disallow it in terms of Section 16 or even to dispute the reasonableness of the figure due non-availability of comparative figures.” The view on management fees was shared TCs who expressed concern on the prevalence of TP abuse of management fees in the mining sector, questioning rationality of some of the management fees as they will be illogically high leaving one to wonder on the kind of services that would have been rendered to match the fees charged.

The majority of TCs also alluded to the use of procurement services fees as the most exploited avenue to distort management fees and to use them to reduce taxable income in Zimbabwe. They highlighted that due to the economic challenges and collapse of most companies in Zimbabwe, now most products, inputs and raw materials for Zimbabwean affiliates or subsidiaries of MNEs are being sourced by sister subsidiaries or parents in foreign countries. The Zimbabwean companies are often paying management fees of around 5% of turnover, which according to TCs and ZIMRA officers is rather exorbitant and violates the Cost-plus method advocated by the OECD guidelines that guide TP in Zimbabwe. Mashiri (Citation2018) submits that there is a tendency to shift expenses such as the payment of royalties for the use of patents, trademarks and franchises to Zimbabwean companies by leasing them these assets to use in order to move profits through the payment for these and hence reduce the taxable income in Zimbabwe. TCs also alluded to the use of auditing fees allocating more to the Zimbabwean affiliates. MNEs would continuously look for tactics to help them maximise shareholder value and profits and the same time lowering their overall tax obligations; thus, revenue authorities and government must also regularly review their TP policies for relevance and effectiveness (Oguttu, Citation2016).

4.2.2. Mis-invoicing (under or over-invoicing)

Kabala and n.d.ulo (Citation2018) refer to trade mispricing as the biggest contributor to revenue leakages in Africa and point to under-pricing of exports especially mining commodities. Analogous findings were arrived at in this study, with TCs (4, 7, 8) pointing out that TP understatement was largely used in the mining sector where most of the companies in Zimbabwe just extract the mineral ores and the processing is done by the holding company in foreign countries. The processing charges are normally highly overstated to show minimal revenues in Zimbabwe. Kwaramba et al. (Citation2016) also brought to light the TP understatement in the mining sector in Zimbabwe when they chronicled the extent of trade mispricing and the magnitude of capital flight in Zimbabwe. The researchers further allude to massive capital flight and profit shifting through trade misinvoicing of minerals with Zimbabwe’s major trading partners such as China, United Kingdom, United States of America and South Africa. The minerals include copper, nickel and gold among others (Kwaramba et al., Citation2016). ZIMRA officers concurred with the argument, adding that it is impossible to verify the charges or to get comparable figures. There was indeed an outcry among interviewees that the government is losing a lot of revenues in the mining sector. This was also in line with submissions by the UNCTAD (Citation2020) that the total under-invoicing in the extractive commodities or mineral exports in Africa is distributed as follows: Gold (77%), Diamonds (12%), Platinum (6%) and other commodities (5%).

TC8 stressed the need for the Ministry of Finance in conjunction with tax experts, ZIMRA and other legal experts to revisit and tweak the provisions of the ITA in relation to taxation of miners, especially the issues to do with the capital redemption allowance (CRA) and prospecting and exploratory expenses incurred prior to production as these are abused by mining companies as “some of them have be prospecting forever without producing, are they really not producing?” This was expressed by TC2. The African Development Bank (ADB) (Citation2011) connects the substantial losses of national revenues in African countries to inefficient taxation of the extractive industry and failure to curb abusive TP by MNEs. As highlighted in, the distortion of invoice prices through either understatement or overstatement depending on the angle that is beneficial was stressed by interviewees. Overpricing of imported raw materials and inputs that are supplied by parent companies outside Zimbabwe to their counterparts in Zimbabwe was underscored by interviewees as well as the over-pricing of management fees as discussed in section 4.1. Overpricing of transferred goods was notably the second most pointed to factor by the majority of participants in the two stakeholder groups (TCs and ZIMRA officers). The motivation for either under-pricing or over-invoicing is influenced by the motivations behind the transaction, whether the objective is to understate the profits or the expenses or to understate the profits and overstate the expenses. It can also depend on several other factors other than the consideration of corporate tax alone but other issues such as import duty rates, WHT rates and repatriation costs among other aspects (Bhat, Citation2009; Cooper et al., Citation2017; Silberztein, Citation2009)

4.2.3. Thin capitalisation

To exploit thin capitalisation, companies excessively finance through debt as opposed to equity in order to exploit the debt-tax saving as interest is tax allowable deduction. Taking into consideration that debt is a risk source of financing, there are situations where you find that the debt financing component is riskily excessive which raise ethical questions on the motivation of using debt. Where the debt has been supplied by related companies or a foreign parent or connected party or affiliate, the TP motivated TP manipulation. ZIMRA officers (3, 6 and 9) were quick to point out that such was a reality with most Zimbabwean companies where officers often find them to be overly debt financed and with this financing coming from related foreign companies. The interest component of servicing this debt will be huge and significantly reducing the taxable profits. This resonates with the submission by the OECD (Citation2015) that thin capitalisation or debt shifting was one of the least difficult ways to avoid tax used by MNEs. Despite the ITA in Zimbabwe making provision to curb debt financing manipulation through setting the thin capitalisation rules and disallowing excesses in terms of Section 16 (1)(q) on prohibition of excessive interest, companies were still finding ways of circumventing the tax legislations and the prohibited deductions limits. ZIMRA 6 gave an example of situations where foreign parents would come to an agreement with their bankers to loan money to Zimbabwe company on their behalf (the bank merely acting as a conduit or pipe for the funds to pass through to the Zimbabwean subsidiary). In the eyes of the tax authorities the company is having a loan from the foreign bank and accordingly pays interest to that bank yet in actual fact the parent company is the owner of the funds and the true receiver of the interest. “It happens, but hard to prove” expressed ZIMRA 6. TCs also reiterated that normally MNEs affiliates offer each other loans that are in actual fact interest free or are charged at very low interests, but for shifting profits and tax planning they would charge these interests. It is evident that despite the use of thin capitalisation ratios being advocated for by the OECD (Citation2015) and provisions for them being made in some developing countries’ tax legislations, they are still open to abuse by MNEs. The challenge is still formidable to deal with for tax authorities and policy makers as schemes to circumvent regulations by MNEs evolve. A combination of these thin capitalisation rules, WHT and other measures such fees charged on remittances remain important measures to address the issue (Oguttu, Citation2017).

4.2.4. Tax havens

Tax havens as described by Mashiri (Citation2018) are “jurisdictions with relatively favourable tax rates, zero tax and/or weak tax administration systems”. ZIMRA officers referred to places such as Barbados and Jersey as tax havens that are used by MNEs in Zimbabwe to move profits as well as potentially taxable revenues and shield them from the supposedly high tax rates in the country. The movement of income to the havens is usually through the manipulation of service fees (management, technical, administrative, procurement and marketing fees) highlighted in Section 4.1. ZIMRA 8 described the exploitation of these tax havens through countries such as Malaysia with lower tax rates where subsidiary companies are created there in paper or just have an office only so as to facilitate income shifting from the sister company based in Zimbabwe that does the manufacturing. The fictitious subsidiary in Malaysia is merely there for re-invoicing the goods from Zimbabwe and sell them at a higher price and make more profits as revenue authorities have no ways of establishing how much the goods are eventually sold for in Namibia. A problem highlighted by Kabala and n.d.ulo (Citation2018) and Jaffer (Citation2019) on the TP regulation implementation challenges and the applicability as well as enforcement of the arm’s length principle. TCs acknowledged that the tax haven use for TP manipulation was a reality in Zimbabwean MNEs some of them who have assets and subsidiaries in foreign nations to exploit the tax rate differences in terms of corporate tax, customs duty and capital gains tax in the disposal of assets. MNEs find ways to shift income from Zimbabwe, a high tax jurisdiction to lower tax jurisdiction eroding the tax base.

4.2.5. Tax incentives

The tax incentives were found to be associated with the exploitation of government policy by the MNEs. In Zimbabwe it was found to be more prevalent in the mining sector, with TCs (3, 6, 9 and 10) pointing out that this was the most abused sector in relation to incentives, exemptions and deductions. TC 2 pointed to export processing zones as another area of incentive abuse. The MOFs as well as ZIMRA officials reiterated the same problems, arguing that in the mining sector MNEs prospect forever without starting production. They will pretend to be prospecting yet in actual fact they are mining because the prospecting costs and pre-production expenses are an allowable deduction. In addition to the abuse of tax incentives, TCs alluded to the losses that are carried forward indefinitely for mining companies, subject to the ring fencing provisions to be a catalyst for abusive TP so as to continuously make losses and avoid tax.

4.2.6. Profit shifting/(low tax jurisdictions)

This strategy has dominated TP literature for years (Oguttu, Citation2017; Marques & Pinho, Citation2016). It basically encompasses most of the above-mentioned strategies as the MNEs transfer profits from one tax jurisdiction to another. Usually profits or income is shifted from a high tax region to a lower tax region in order to derive a group advantage.

NB* Despite treaty shopping being mentioned by participants, literature suggests that it has to do with BEPS and not directly with TP, hence it was not discussed here.

4.3. Proposed solutions

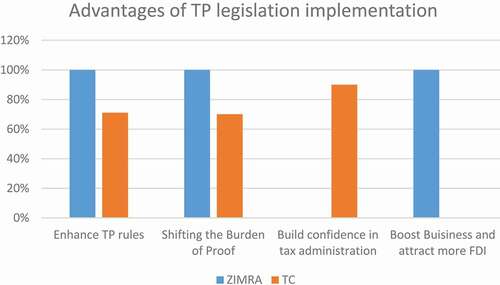

Participants were asked to suggest possible ways of addressing the TP abuse challenges in light of the TP strategies they highlighted earlier. All participants from the three groups highlighted the adoption of TP regulations as very vital in dealing with TP dilemma of curbing revenue losses and still remaining attractive to FDI. TC1expressed that “the adoption of TP rules is key to dealing with the transfer pricing ways that are used by MNEs, it is important to ensure the principle of pricing at arm’s length is upheld”. In concurrence ZIMRA6 also advanced that putting in place TP regulations and improving them as we go is important. They might not be 100% effective as of now, but it is important to start somewhere. We consider the current transfer legislation a learning curve and a foundation to build on. TC6 on the other hand agreed that implementing TP legislation was important, but emphasised that challenges on their effectiveness have to be addressed. The consultant stated that “challenges such as lack of skills, expertise and financial resources, unavailability of comparable data and databases, corruption and many other issues need to be dealt with urgently to make the current legislation more fruitful”. Further discussion revealed four reasons why the participants felt so strongly about the adoption of the TP legislation. These were the enhancing of TP rules and standardising the treatment of TP transactions, the passing of the burden of proof to the taxpayer, building confidence in tax administration and boosting business and attracting more FDI. The results on these are presented in .

The recommendations are consistent with findings in the literature. Cooper et al. (Citation2017) underscored the need for developing countries to have in place TP legislation that will assist and guide them in dealing with the problem of transfer mispricing and its detrimental effects on the economies. The authors conclude effective implementation of TP regulations is advantageous in a number of ways: help fight against tax evasion; minimise the impact of illicit flows as increased scrutiny of transactions could dissuade those abusing TP to minimise such activities due to fear of detection, audit and penalties; bring clarity and certainty on how related party transactions are regulated and dealt with for tax purposes; bring equity in the treatment of both local and foreign investors, hence showing stability and consistency in the investment climate and finally to preserve and protect the competitiveness of local industries from TP (Cooper et al., Citation2017; Mashiri, Citation2018). Analogous views were shared by various researchers on the benefits of adopting TP regulations on protecting the tax base, stabilising the investment climate and attracting foreign direct investment (Barrogard et al., Citation2018; Burgers & Mosquera, Citation2017; Mashiri, Citation2018). The other suggestions were to use withholding taxes in order to collect on any remittance that go out of the country. Zimbabwe tax legislation was recommended for its withholding taxes on dividends, royalties, director’s fees and other remittances. Participants also highlighted that the country should re-evaluate its investment laws, pricing of mineral commodities and tax legislation as it affects the extractive industry.

4.4. Discussions and implications

In line with the conceptual framework presented in , the study established the cogency of the theoretical framework and the conceptual framework. MNEs are indeed rational actors that weigh the cost and benefits and make decisions that optimise their profits and reduce their tax liability despite the costs that are suffered by developing countries through their actions. The rational choices crystallise themselves in strategies they employ to manipulate TP. Consistent with the narrative, “the use of service” topped the charts as tax avoidance strategies through TP. This finding has not been documented in antecedent literature. This study provides robust evidence of a salient strategy, “use of service” as a high-risk area in the realm of transfer pricing, a concept which Oguttu (Citation2018) attests as difficult to verify or apply the ALP in source-based jurisdictions. Przysuski et al. (Citation2004) describe intragroup services as a controversial subject in the TP discourse. The findings of the study extend the propositions of the rationality theory discussed in Section 2.4 (theoretical and conceptual framework). The decision to manipulate transfer pricing through the “use of services” and management fees in particular is a rational one for MNEs. The MNEs take advantage of the subjectivity of establishing the prices of these services and lack of comparable information to exploit the pricing to minimise their tax obligations in high tax jurisdictions such as Zimbabwe. Weighing the cost and benefits, the benefits outweigh the costs since the likelihood of revenue authorities proving that indeed there is mispricing, is minimal. Thus, rationality theory is at play as expostulated by Brunsson (Citation1982), Weber (Citation1968), and Rouse (Citation2007) as well the rational economic actor explained by Allingham and Sandmo (Citation1972). The study, therefore, serves as an important contribution to both theory and practice as it provides insights for the formulation of targeted approaches as opposed to misdirected approaches by policy makers and tax authorities. This was then followed by mis-invoicing, thin capitalisation and tax havens. These TP schemes employed by MNEs, while aimed at maximising shareholder value and lowering tax obligation, often have detrimental effects to developing countries. These unfavourable effects include erosion of the tax base, failure by government to mobilise enough revenue for economic development and poverty alleviation endeavours among many other social, economic and psychological impacts. In defence of MNEs Asongu et al. (Citation2019) suggest that the MNEs compensate for their TP abuses through their corporate social responsibility activities, this is debatable and a gap for further research. As highlighted earlier, that it was imperative that developing countries understand TP strategies adopted by MNEs so that they will be able to balance the desire to promote international trade, attract FDI and at the same time maintain effectiveness in crafting of policies and legislation to regulate, monitor and minimise the abuse of TP. Getting an insight into the TP strategies used by MNEs in Zimbabwe was fundamental to contribute to the development and improvement of TP policies and to enhance their effectiveness. This exposition provides important information to policymakers and revenue authorities, which helps them devise targeted ways of dealing with these strategies especially with regard to the “use of management fees” as the widely used strategy in the country-. The solutions suggested by the participants in Section 4.3 also helped inform the recommendations made by the study.

5. Conclusions, limitation, recommendations and areas of further research