Abstract

This paper contributes to the smallholder agriculture commercialisation literature by applying the Theory of Planned Behaviour in an under-researched developing country context. The study examines the influence of attitude, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control on the Scaling-Up intent among smallholder village chicken (free-range or indigenous) farmers in North-western Zambia. Additionally, gender differences regarding commercialisation intent are examined. Based on a quantitative correlational design utilising 556 smallholder farmers’ primary data from a structured questionnaire, statistical correlation and student’s T-test models were employed. The findings indicate that attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control have unique positive significant effects on commercialisation practices intention (CPI) and CPI in turn positively influences commercialisation scaling-up intention (CSI). Additionally, the study found significant gender differences in all aspects of the model except for subjective norms. Despite the study being cross-sectional and based on one district in Zambia, the findings have important implications. For policymakers and enterprise support institutions, understanding the socio-psychological factors of smallholder farmers is important before introducing any interventions to promote the commercialisation of the village chicken. Additionally, there is a need to encourage farmers to adopt commercialisation practices in livestock management, investment and marketing. This would increase the chances of transitioning from subsistence to commercial farming. In terms of narrowing the gender gap in participation, there is a need for policymakers to tailor interventions that would help improve the attitude of women towards commercialisation and to reduce the perceived barriers. The study pioneers application of the TPB in this context.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Commercialisation is about increasing the scale in production and marketing to transition from subsistence to commercial status. The issues of smallholder agricultural commercialisation and gender-gap reduction have taken centre stage recently among policymakers in government and development agencies. On one hand, commercialisation is regarded as essential for reducing poverty in rural populations with value chains such as the village chicken recognised as having massive potential. This is because many villagers keep indigenous chickens while the market demand outstrips supply. This notwithstanding, several farmers have struggled to transition from subsistence to commercial scale. The issue of enhancing commercialisation behaviour has therefore become critical for policymakers. On the other hand, the gender disparities regarding access to resources is a concern as men tend to dominate commercialised value chains. Therefore, understanding gender disparities, commercialisation intent and antecedents thereof may be key in designing interventions to help enhance commercialisation.

1. Introduction

Commercialisation is about increasing the scale in production and marketing to transition from subsistence to commercial status. The discussions regarding smallholder farm commercialisation and gender disparities have taken centre stage in the smallholder agriculture and rural development discourse (Maumburudze et al., Citation2016; Quisumbing & Pandolfelli, Citation2010). A majority of studies have mostly focused on social-economic factors as drivers of village chicken (also known as free-range or indigenous chickens) commercialisation and have ignored the role of social-psychological factors (B.J. Siyaya & Luyengo, Citation2013; Maumburudze et al., Citation2016; Ochieng et al., Citation2013; B. Siyaya & Masuku, Citation2013a). Evidence from the extant literature suggests that there is an increasing call for a shift from applying economic models that have been applied to human decision making to using social psychological models (Hansson et al., Citation2012; Poole et al., Citation2013; St. John et al., Citation2010) (Hansson et al., Citation2012; Poole et al., Citation2013; St. John et al., Citation2010). Additionally, prior literature reveals that increased commercialisation of agriculture leads to increased disadvantaging of women because of persistent gender disparities in access to productive resources (Fischer & Qaim, Citation2012). While it is generally agreed that the male folk dominate most commercialised value chains, it is important to understand the gender differences in levels of commercialisation intent in value chains that are generally regarded as women dominated. The indigenous chicken’s value chain in particular is not only dominated by women but is also known to be a “woman’s” value chain (Dolberg, Citation2007; Mapiye et al., Citation2008). Most of the relevant studies have focused on the socio-economic drivers of indigenous chickens commercialisation (Aryemo et al., Citation2019; B.J.J. Siyaya & Masuku, Citation2013b; Maumburudze et al., Citation2016; Ochieng et al., Citation2013). There is a shortage of studies to ascertain the role of social psychological factors in smallholder farmer decision making to transition from subsistence to commercial farming of indigenous chickens. Borges et al. (Citation2014) noted that studies on the adoption of innovations usually ignore underlying psychological constructs that affect farmers’ decisions and behaviour, such as intention, perceptions, and beliefs. Additionally, hardly any study has considered gender differences regarding the intention of smallholder indigenous chicken farmers to transition from subsistence to commercial scale.

The indigenous chicken is essential because of the potential not only for commercialisation but also for helping with poverty reduction in Sub-Saharan Africa. Maumburudze et al., (Citation2016) argue that enhancing the production and productivity of village chickens can accelerate the development of the rural social economy as village chickens are not only a source of protein but also a viable income earner. What makes the commercialisation prospects of the village chicken even more attractive is that a majority (>80%) of households in rural Africa keep village chicken and the demand for village chicken is higher than the supply (Queenan et al., Citation2016). Despite the forgoing commercialisation potential, full commercial exploitation of this value chain by smallholder farmers is yet to become widespread (Bwalya & Kalinda, Citation2014; Maumburudze et al., ; Ochieng et al., Citation2013).

While it is essential to focus on the commercialisation potential and how socio-psychological factors affect farmer decision-making, it is equally vital to take into account gender differences in village chicken commercialisation. Understanding gender differences in commercialisation would help to inform policymakers and development organisations as they formulate policies and interventions meant to empower women. For example, Assan (Citation2014) emphasises that future rural sustainable livestock development programs and projects should take into account the gender dimension. This is because livestock production strategies which pay attention to gender differences, women’s rights and responsibilities are more likely to enhance food security (Assan, Citation2014). Buttressed by the underutilised theory of planned behaviour in smallholder commercialisation decisions, the focus of this study is twofold. Firstly, the study examines the role of social psychological factors as predictors of smallholder farmer commercialisation intentions. Secondly, the study explores gender differences in the levels of commercialisation intention among the smallholder farmers. In light of the foregoing, this paper is divided into five sections. Section 2 not only highlights literature reviewed on the relevant conceptual and empirical issues and develops the research hypotheses but also describes the methods of the study. Results of the study are reported in section 3 while discussion thereof is undertaken in section 4. Lastly, section 5 considers study conclusions, limitations and directions for future research.

2. Conceptualisation and methods

This section presents a review of the relevant literature, theoretical underpinnings and development of the study hypotheses. Additionally, the second part presents the methods used in the study.

2.1. Agricultural commercialisation and commercialisation behaviour

There are various definitions and perspectives of what agricultural commercialisation is really about. Leavy and Poulton (Citation2007) argued that a lack of clarity about what agriculture commercialisations mean may give rise to misconceptions and evoke fears that may obstruct policy formulation and practice. Some view commercialisation as managing or exploiting resources in a way to make a profit (Maumburudze et al.). Rukuni et al. (Citation2006) define commercialization as a transition from mostly subsistence agriculture (based on production for own consumption) to production for the market, i.e. both local and export markets. There is also a view that commercialisation processes can occur either on the output side of production requiring marketing of the surplus or on the input side requiring increased use of purchased inputs (von Braun and Kennedy, 1994). Others argue that commercialisation focuses on profit maximisation by adjusting either the production or output side. For example, some scholars (Pingali et al., Citation1995, p. 171) point out that:

“Agricultural commercialization means more than the marketing of agricultural output. It means that the product choice and input use decisions are based on the principles of profit maximisation. Commercial reorientation of agriculture occurs for the primary staple cereals as well as for the so-called high-value cash crops. On the input side, commercialization implies that both traded and non-traded inputs are valued in terms of their market value.”

As a consequence of the foregoing perspectives, it is important to embrace a broader view of commercialisation; this entails not only focusing on the marketing of agricultural output but also product choice, input decisions and profit maximisation. This is the view that has been adopted in the study. Agricultural commercialisation has gained prominence in the smallholder agriculture and rural development discourse (Maumburudze et al.).

2.1.1. Benefits of adopting indigenous chicken commercialisation behaviour

The prospect of tangible benefits that may be the outcomes of a particular agricultural technology or practice can facilitate adoption. Maumburudze et al. (Citation2016) suggest that market and price disincentives may be a hindrance to the commercialisation of indigenous chicken. Adoption of commercialisation in the indigenous chicken value chain by smallholder farmers can benefit the rural households economically thereby contributing to poverty reduction (B.J.J. Siyaya & Masuku, Citation2013b; Bwalya & Kalinda, Citation2014; Maumburudze et al., Citation2016; Ochieng et al., Citation2013). Extant literature also reveals that the other benefit presented by the indigenous chicken value chain is the continued increased demand due to its tastiness and low-fat content (B.J.J. Siyaya & Masuku, Citation2013b; Bwalya & Kalinda, Citation2014; Maumburudze et al., Citation2016; Queenan et al.). Farmers also stand to benefit from good margins as the indigenous chickens fetch a premium price even though they are from a low-input and low-cost food production system (Bwalya & Kalinda, Citation2014).

It must be highlighted though, that for the farmers to enjoy the benefits of commercialisation, there is a need for certain factors to be in place both at the farmer and institutional levels. The indigenous chicken enterprise continues to be a low-input low output system because of, inter alia, failure by farmers to adopt appropriate management intervention best practices (Ochieng et al., Citation2013). Lack of access to institutional support is also another factor that may prevent the farmers from actualising the benefits of producing indigenous chickens on a commercial scale. Indigenous chickens, which are a form of small livestock, continue to suffer neglect from governments and other agencies supporting agriculture by directing most institutional support to traditional crops and large livestock (Bwalya & Kalinda, Citation2014; Dolberg, Citation2007).

2.1.2. Barriers to indigenous chicken commercialisation

The presence of barriers or constraints has the potential to affect the adoption of agricultural technologies and practices. Van der Pligt and Vries (1992) observed that the relationship between intentions and behaviour can be complicated by barriers to the expression of the behaviour or by a lack of skills as depicted in .

Equally, Constance and Choi (Citation2010) observed that constraints in the adoption of organics by farmers in the USA played a role in the limited adoption of organics. Barriers preventing the full commercialisation of the indigenous chicken value chain are several, starting from a lack of infrastructural and institution support to factors at the farmer level such as a lack of business orientation and failure to adequately apply appropriate management practices. Extant literature notes that inadequate infrastructure and institutional support limit the adoption of technologies and agricultural practices (Hailemichael et al., Citation2017; Khapayi & Celliers, Citation2016; Niles et al., Citation2015; Yaseen et al., Citation2018). For example, the study by Khapayi and Celliers (Citation2016) found that one of the limiting factors against progress to commercial agriculture was poor physical infrastructure such as inaccessible roads and lack of transportation to the markets from the farms. Similarly, the study by Hailemichael et al. (Citation2017, p. 37) reports the following about village poultry farmers in Ethiopia:

“Infrastructural factors influenced households whether or not to own or keep poultry. The further a household from an all-weather road, the less likely it would be engaged in poultry keeping. This shows that low access to markets limits the drive of the households to keep poultry.”

The foregoing examples demonstrate the extent to which inadequacies in infrastructure play a limiting role in the adoption of technologies or agricultural practices. Firstly, infrastructure such as roads, storage facilities and access to functional markets continues to be a major challenge for the farmers as some of them are situated in very remote areas. Inadequate infrastructure contributes towards the transactional costs of the farmers and is one of the reasons that demotivates farmers to undertake farming at a commercial scale. Aryemo et al. () pointed out that institutional factors such as availability of markets, access to extension services, belonging to a group, road infrastructure; and market-related factors such as access to markets affect a farmer’s decision on whether to commercialise or not.

Secondly, a lack of institutional support such as the provision of extension services, farmer training, and credit facilities continue to limit the potential of farmers to rear village chickens at a much larger scale. For example, a study conducted in Zambia by Bwalya and Kalinda (Citation2014), observed that there were only a few pieces of training received by the households on techniques of indigenous chicken production and this was attributed to the low emphasis that small-livestock had received from policy-makers and other agencies supporting agriculture. These barriers have the potential to dissuade farmers from transitioning to commercial farming as their attitudes are negatively affected.

Thirdly, a lack of a business orientation among smallholder Zambian farmers may be considered as one of the major constraints towards agriculture commercialisation. Siegel (Citation2008) noted that the greatest constraint facing many Smallholder Zambian farmers is the lack of a more business-oriented approach and that most of them view farming as a way of life and not as a business. This is an attitude problem and contributes greatly to the farmers’ failure to transition from subsistence farming to commercial farming.

Fourth, the literature is replete with cases citing inadequate management practices as one of the causes for low productivity and commercialisation levels of the indigenous chicken (Maumburudze et al., Citation2016; Ochieng et al., Citation2012, p. 2013). Inadequate management in areas such as disease and health management, feeding, marketing practices and investment practices are often mentioned.

2.2. The role of social psychological factors in adoption decisions, commercialisation and gender

The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) has been used in several studies about farmer decision making such as the adoption of agricultural practices and technologies (Borges et al., Citation2014; Hansson et al., Citation2012; Hattam, Citation2006; Wang et al., Citation2018). Borges et al. (Citation2014) found the TPB to be a pertinent model to analyse farmers’ decisions and behavioural intentions. However, the TPB has not been used in prior studies to examine behavioural intentions concerning commercialisation. This study, therefore, seeks to fill this gap by adapting this model to help analyse smallholder farmer commercialisation intention of the indigenous chicken and also the gender differences. The TPB model consists of three independent latent constructs namely attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control. Hattam () posits that the TPB states that to sufficiently predict behaviour, the combined role of attitude, social pressures and the perceived difficulty in carrying out the actions are important. The different definitions of the components of the TPB by Azjen (1991) and the proposed hypotheses follow below:

Attitude toward a particular behaviour refers to the degree to which a person has a favourable or unfavourable evaluation or appraisal of the behaviour in question. If an individual perceives that the performance of a certain behaviour is likely to lead to an unfavourable outcome, likely, they will not perform that behaviour (Mwiya et al., Citation2019).

It is evident in the literature that men tend to be more motivated than women when it comes to matters of commercialised value chains. Men tend to also have a higher risk appetite than women (Ayub et al., Citation2013; Powell & Ansic, Citation1997).

2.2.1. Social norms

Refer to the perceived social pressure to perform or not to perform the behaviour. This means that the influences of other people on an individual farmer (such as friends, family and fellow farmers etc.) may have a bearing on adopting or not adopting the innovation. The role of important others in the non-adoption of a particular innovation could be because innovation may be against a cultural norm or has a negative externality to neighbours. For example, most village chickens are grown using the free-range system where the chickens are left to scavenge for food without control and this might lead to the destruction of garden crops belonging to a farmer’s neighbour. Rearing indigenous chickens on a commercial basis can lead to gender stereotypes and bias where the important others are likely to back men to succeed than women because of the pre-determined gender roles ascribed by society. The societal role for women in most African traditional communities may be perceived to be limited to taking care of the household and chores whilst men’s role may focus on bringing income into the household.

2.2.2. Perceived behavioural control (PBC)

Refers to people’s perception of the ease or difficulty of performing the behaviour of interest. Azjen (1991) clarifies that PBC is dependent on the resources and opportunities (e.g., time, money, skills, and cooperation from others) available to a person to achieve a certain behavioural undertaking. Furthermore, PBC is assumed to reflect experience as well as anticipated impediments and obstacles that an individual is likely to face when performing a certain behaviour (Azjen, 1991). Evidence in the literature suggests that male farmers are more likely to have control over the commercialisation process than women because of resource access bias. Fischer and Qaim (Citation2012, p. 441,) noted that:

“With the commercialization of agriculture, women are increasingly disadvantaged because of persistent gender disparities in access to productive resources.”

2.2.3. Behavioural intentions

Refer to the perceived likelihood of performing the behaviour. Ajzen (1991) elaborates that intentions are indications of how hard people are willing to try, of how much of an effort they are planning to exert to perform the behaviour. It follows therefore that the stronger the intention to engage in a behaviour, the higher the likelihood that it will be performed.

Commercialisation is synonymous with “profitability” and there is a general belief that men tend to take over value chains that are commercialised and profitable by displacing women (Fischer & Qaim, Citation2012; Sørensen, Citation1996; Tsusaka et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, Aryemo et al. () indicate that although women are usually involved in the production, it is predominantly the role of men to decide on sales and other marketing decisions regarding indigenous chickens, an indication that men are more commercially oriented.

2.2.4. Commercialisation practices intention

This study has adapted the TPB model by adding a lower level intention (commercialisation practices intention (CPI), which is a composite of Management Practices Intent, Investment Practices Intent and Marketing Practices Intent), and is believed to influence commercialisation scaling-up Intention (CSI). The addition of this construct to the model is in line with the observation by Gasson (1973) that behaviour can respond to a single intention or several interlinked intentions (Bergevoet & Woerkum, Citation2006; Gasson, 1973).

For village chicken farmers to commercialise, certain commercialisation practices may have to be adopted first. Commercialisation practices intention, therefore, proposes that farmers are willing to adopt commercialisation practices for them to transition from subsistence to commercial farming. The practices that farmers adopt or do not adopt have an implication in terms of the productivity and marketing of village chickens at the commercial level. For example, Maumburudze et al., (Citation2016) observed that farmers need to strengthen animal husbandry practices to reduce mortality and enhance productivity and that commercialisation can be promoted by feed supplementation and medicines.

The commercialisation practices intention construct in our model is a composite of three practices namely:

2.2.5. Management practices intent

—refers to the intention to adopt management practices such as better and improved feeding, health and housing of the village chickens. Failure to embrace improved management practices is a recipe for low village chicken productivity and therefore hampers any commercialisation prospects. Zewdu et al., (Citation2013) indicate that poor management practices on feeding, housing and disease control for village chickens represent one of the constraints to increased productivity.

2.2.6. Investment practices intent

—refers to the intention to adopt practices to do with investing resources and time in the village chicken venture for improved production and marketing purposes. A common description in the literature that characterises village chicken production is that it is a low-input and low output system. Some of the areas where it is essential to invest include feeding, housing, health and marketing of village chickens. Alders and Pym, (Citation2009) noted that the conditions for the successful commercial sector in poor countries are missing and these include the ability to purchase quality feed, vaccines, drugs and equipment. In their study, (Hailemichael et al., Citation2017) in an attempt to signify the importance of investment, posited that lack of use of external or purchased inputs is another barrier that limits village poultry production. The point noted above is in line with Pingali et al. (Citation1995) who characterise or emphasise the need to use traded input for commercially oriented farmers.

2.2.7. Marketing practices intent

refers to the intention to adopt practices such as sales record keeping, proactively searching for customers, use of collective marketing techniques and use of weighing scale. Poor marketing management practice was identified as one of the constraints of village poultry production by Mapiye and Sibanda (Citation2005). It has also been noted that the well-organized marketing of indigenous chickens is difficult due to the small flock sizes reared by farmers (Chandraschka, 1998).

2.2.8. Commercialisation scaling up intention

The theory of planned behaviour posits that intention is the best predictor of behaviour and the focus of this study is how commercialisation scaling up intention influences indigenous chicken commercialisation behaviour. Aryemo et al. () argue that commercialization entails both market orientation (production decisions are based on market signals and entail the degree of resource allocation to produce agricultural products meant for sale) and market participation i.e. the proportion of products offered for sale (Gebremedhin and Jaleta Citation2010)). Decisions to increase productivity take place at the production level of the value chain while those to do with increased sales/market participation take place at the marketing level. Furthermore, Justus et al., (Citation2013) observed that low productivity when rearing indigenous chickens would limit the potential for commercialisation. We can therefore say that one of the pre-requisites for successful commercialisation of indigenous chickens is high productivity in terms of both quantity and quality of the birds. The second prerequisite for commercialisation is the ability of farmers to sell more of the indigenous chickens. It is, therefore, appropriate to say that the farmers need to have developed commercialisation scaling intention (intention to increase both productivity and sales/market participation).

2.2.9. Commercialisation and gender

In addition to using the theory of planned behaviour in this study, feminist theories have also been adopted. Acker (Citation1987, p. 421) considers feminist theories as theoretical frameworks that address, “the question of women’s subordination to men: how this arose, how and why it is perpetuated, how it might be changed and (sometimes) what life would be like without it.” Acker further goes on to say that feminist theories play a dual role in society namely, i) as guides to understand gender inequality and ii) as guides to action. There are different feminist theories and below we capture what the different theories entail:

Liberal feminist theory

The social feminist theory

Radical feminism

To understand gender differences, it is imperative to consider both gender bias and gender gaps. Extant literature suggests that gender biases, as well as gender gaps, are very prominent in agricultural commercialisation. According to Dugan (Citation2008), gender bias refers to the socially constructed preference for one sex/gender over the other. Gender bias disproportionately affects women, mainly because of the patriarchal system embedded within the social structure. In simple terms, gender bias represents the culturally formed predispositions that individuals, groups, organisations and societal institutions place upon women and men (Dugan, Citation2008). The extent of gender bias has consequences for agricultural development. To this effect, the World Bank (Citation2009) noted that gender differences, arising from the socially constructed relationship between men and women, affect the distribution of resources between them and cause many disparities in development outcomes. Assan (Citation2014) further noted that despite their considerable involvement and contribution, women’s role in livestock production has often been underestimated or, worse, ignored. In the agricultural context, for example, cash cropping is generally known to be a man’s domain and subsistence cropping as a woman’s domain. Similarly, in livestock, large animals that are considered highly valuable are considered to be a man’s domain and small livestock like indigenous chickens are considered to be a woman’s domain. Furthermore, men are known to takeover value chains that seem lucrative and profitable at the expense of women. Gender gap, on the other hand, means a systematic difference or disparity between women and men which is a result of structural forces and cultural influences in society (Gerstel and Clawson, Citation2014).

Agricultural commercialisation has not been spared from the socially constructed phenomenon of gender bias and gender gap as men more than women are seen to have more access to productive resources and capacity building opportunities that are essential to actualising commercialisation. Occurrences of gender bias and the gender gap in agriculture have the potential to encourage or discourage the adoption of commercialisation behaviour in agriculture. These occurrences, not only affect the attitude that smallholder farmers have towards adopting the commercialisation behaviour but also their perceptions in terms of the feasibility of pursuing commercialisation on account of resource availability or unavailability.

2.3. Study hypotheses summary

In light of the foregoing discourse on attitudinal antecedents of commercialisation intentions and the possible gender bias, a total of five (5) hypotheses have been suggested as reflect in our conceptual model in :

H1—Attitude towards commercialisation positively influences the intention to engage in practices that enhance the commercialisation of the village chicken.

H2—There is a positive relationship between subjective norms and intention to engage in commercialisation practices for the village chicken.

H3—There is a positive relationship between perceived behavioural control and intention to engage in practices that enhance village chicken commercialisation.

H4—The intention to engage in commercialisation practices is positively associated with the scaling up intention.

Male farmers are generally considered to be more commercially motivated and capacitated than female farmers when it comes to the adoption of commercialisation behaviour (Ochieng et al., Citation2013).

H5—Male village chicken farmers have higher scaling up intention and its antecedents than female farmers.

2.4. Methods

2.4.1. Study area

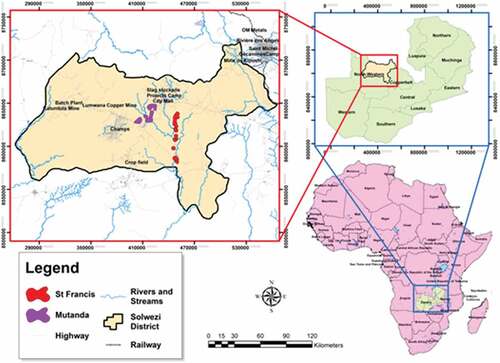

The empirical study was conducted in Solwezi district of North-Western Zambia. Solwezi district was selected because it is the new mining hub in Zambia which is situated in a province that is referred to as the “new Copperbelt” because of the booming mining activities. Two farming blocks namely St Francis Farming Block and Mutanda Farming Block were selected from the district as study sites. The two farming blocks were selected due to their proximity to the new mining hub in North-western province and the market opportunities for agri-produce presented by the mining activities. In addition, the two study areas were chosen because households in these areas are known to keep village chickens as part of their traditions in a largely subsistent manner.

Each farming block is made up of camps and each camp is made of farming zones. shows the area map of the two Farming Blocks which were the focus of this study.

2.4.2. Study design

A quantitative cross-sectional design was employed in the study. This is because it allows for a reasonably large sample to help generalise the research conclusions when testing hypotheses in a quantitative study.

2.4.3. Sampling

A multi-stage stratified sampling technique was employed. In the first stage, clusters of 20 village chicken farmers were purposively identified using the agricultural extension staff as there were no official registers that captured the names of farmers engaged in village chicken production. Prior scholars observed the non-existence of official records for the village chicken in Zambia (Queenan et al., Citation2016) as follows

“In Zambia, no national livestock census has been conducted for almost 20 years. Estimates from the National Livestock Epidemiology and Information Centre (NALEIC) either do not include poultry at all, or do not disaggregate figures into poultry groups, or chicken types (i.e. indigenous or commercial).”

Further, other scholars observed that for the poultry sub-sector, there are no comprehensive or validated lists of individuals (farmers or labourers in agriculture/agribusiness) across the country (Krishnan & Peterburs, Citation2017).

When collecting the data, based on the database of a 5-year projectFootnote1 in the study area, 20 indigenous chicken farmers were selected from each farming zone in the two farming blocks. Thus, the survey questionnaire was administered to 960 village chicken farmers from 48 zones.

2.4.4. Data collection

Ultimately, a total of 556 survey questionnaires were completed by farmers coming from 46 farming zones of two farming blocks (Mutanda farming block and St Francis farming block) between 25 June 2019 and 15 July 2019. Data were collected using SurveyCTO collect. In recruiting enumerators, only those who understand the local language (Kii Kaonde) were recruited and trained before the data were collected. Furthermore, the instrument was translated into Ki Kaonde to ensure consistency and reduce the chances of losing meaning. Before final data collection, the questionnaire was piloted among village chicken farmers in another zone that was not part of the study to check if the questions were clear.

A five (5) point Likert scale was used for respondents to indicate the extent to which they agreed with the proposed statements. The use of the 5 points Likert scale is similar to prior studies in agriculture as they are arguably short enough to allow respondents to distinguish meaningfully between the response options (Bergevoet et al, 2004; Hansson et al., Citation2012; Wang et al., Citation2018). The use of the five (5) points Likert scale is also ideal in situations where the farmers have not attained advanced education and therefore may only handle fewer response options. The respondents‘ profile table () for this study shows that the majority of the respondents did not attain advanced education as 87% fell in the bracket between zero (none) attainment of education and Junior secondary school. The use of the five (5) points Likert scale is therefore justified given the low education attainment of the respondents.

Table 1. Respondent Profile Table

2.4.5. Data analyses

SPSS version 25 was used to analyse the data for the study. The software is particularly useful for survey questionnaire data requiring descriptive and inference data analyses techniques for hypotheses testing (Pallant, Citation2016).

2.4.6. Reliability test

A reliability test was executed to assess the internal consistency of the questionnaire items for internal validity purposes. The questions in the instrument were largely adapted from prior studies; there were no studies found specifically on commercialisation intention and behaviour in the indigenous chicken value chain. All Cronbach’s Alpha values (see ) were above the minimum threshold of 0.70 (Pallant, Citation2016).

Table 2. Internal consistency test of the instrument

In addition to reliability tests, checks for missing data, outliers and normality were performed on the scale data. The descriptive statistics revealed that there was no missing data on all the variables from all the respondents. Concerning outliers, an inspection of boxplots and comparison of actual means with the 5% trimmed means for the variables revealed no extreme scores with a strong influence on the means (Pallant, Citation2016). Lastly, in terms of normality, most of the constructs hard a kurtosis and skewness within the range of +2 to −2. Additionally, Hair et al. (Citation2014) suggest that larger sample sizes (i.e. sample sizes greater than 200) are robust enough to take into account any adverse effects of non-normality. Thus, the sample size of 556 is more than adequate for such requirements.

3. Results

3.1. Correlation analyses

An assessment of the strength and direction of the relationships among the different variables was performed using Pearson correlation analyses. Pallant (Citation2016) guides that the use of correlation analyses is appropriate for exploring the strength and direction of the relationships between two continuous variables. shows the correlations, means and standard deviations of the dependent variables (Commercialisation practices intention, scaling up intention) and independent variables (Commercialisation Attitude, Subjective Norms and Perceived Behavioural Control). The table also includes results for control variables namely, Age Groups, Marital Status, Education Level, Household Type and Gender.

Table 3. Correlations Matrix

The correlation matrix was also used to assess multi-collinearity among the independent variables. Pallant (Citation2016) indicates that multi-collinearity exists when the independent variables are highly correlated (r = .9 and above), such that some of them may be deemed to be practically measuring the same thing. From the correlation matrix (), none of the correlations among the independent variables (Commercialisation Attitude, Subjective Norms and Perceived Behavioural Control) is 0.9 and above.

Table 4. Independent Samples t-Test

The correlation matrix shows that commercialisation practices intent is significantly (all sig. ≤ 0.01 level, 2-tailed) and positively related with commercialisation attitude (r = 0.631), subjective norms (r = 0.276) and perceived behavioural control (r = 0.652). The effect sizes range between small and large as recommended by Cohen’s criteria (i.e. small = 0.10 to 0.29, medium = 0.3 to 0.49 and large = 0.50 to 1.00). Hypotheses 1, 2 and 3 are also supported as the signs are positive for the correlation coefficients. This means that farmers who have a higher attitude towards village chicken commercialisation, are also influenced by the important others to engage in the commercialisation of village chickens and perceive that they have the resources, knowledge and skills to engage in village chicken commercialisation, are more likely to adopt the necessary commercialisation practices (management practices, marketing practices and investment practices). Additionally, the results imply that the stronger the commercialisation practices intention by the farmers, the higher the intention to scale up (r = 0.729), with a large effect size. This supports Hypothesis 4. Overall scaling up intention has positives relationships with commercialisation practices intent (r = 0.729) and its antecedents (commercialisation attitude: r = 0.418; Subjective norms, r = 0.226 and Perceived behavioural control, r = 0.449). This means that the higher the commercialisation practices intent, the higher the likelihood that the farmers can scale up. In essence, the farmers may not scale up if they do not adopt commercialisation practices that are necessary to increase their village chicken productivity and marketing.

3.2. Independent samples t-test

To examine the gender differences in the intention for indigenous chicken farmer commercialisation, independent samples t-tests were carried out. The independent samples t-test is used to compare the mean scores of two different groups of people or conditions (Pallant, Citation2016). To ensure that the assumption of the equality of variance was not violated, Levene’s test for equality of variance was checked and in instances where the p-value was less than or equal to 0.05 (unequal variances), results for Equal variances not assumed were used (Pallant, Citation2016). shows the results of the independent samples t-tests.

First, the results show that there was a significant difference in scores for Scaling Up Intent, Males (mean = 4.628, SD = 0.656, p-value = 0.002), Females (mean = 4.432, SD = 0.808, p-value = 0.002). The males had a higher mean score and the effect size for the differences in the mean (mean difference = 0.196) was small (eta squared = 0.018).

The second significant difference was observed in scores for Commercialisation practices intent, males (mean = 4.292, SD = 0.604, p-value = 0.000), females (mean = 4.040, SD = 0.731, p-value = 0.000). The male farmers had higher mean scores than the women farmers and the magnitude of the difference was small (eta squared = 0.034).

Third, the results show that the gender differences with regard to antecedents of commercialisation practices intention were all significant with the exception of subjective norms. The subjective norms scores, males (mean = 3.802, SD = 1.039, p-value = 0.530), females (mean = 3.747, SD = 1.038, p-value = 0.530). The males had a higher mean score and the magnitude of the differences in the mean (mean difference = 0.055) was very small (eta squared = 0.001). The commercialisation attitude scores, males (mean = 4.343, SD = 0.673, p-value = 0.022), females scored (mean = 4.204, SD = 0.747, p-value = 0.022). The males had a higher mean score and the magnitude of the differences in the mean (mean difference = 0.139) was very small (eta squared = 0.007). The perceived behavioural control scores were; males (mean = 4.055, SD = 0.748, p-value = 0.002), females (mean = 3.856, SD = 0.790, p-value = 0.002). The males had a higher mean score and the magnitude of the differences in the mean (mean difference = 0.199) was small (eta squared = 0.016).

Based on the correlation matrix () and Independent Samples T-test (), a summary of the study findings is encapsulated in .

Table 5. Results of Hypothesis Testing

4. Discussion

The findings in this study suggest that subjective norms, attitude towards commercialisation and perceived behavioural control significantly influence commercialisation practices intention. Commercialisation practices intention in turn is positively associated with overall scaling up intention for indigenous chickens among the smallholder farmers. This means therefore that hypotheses 1 to 4 are supported with small to large effect sizes. In terms of gender differences, the findings supported all the hypotheses except for subjective norms. This means that there were significant gender differences observed on two (2) of the antecedents of commercialisation practices intention (attitude towards commercialisation and perceived behavioural control) and no significant differences were observed on subjective norms. Further, there were significant gender differences as regards commercialisation practices intention and scaling up intention.

The results on the relationships between intention and its antecedents are consistent with the results of agriculture-related studies. Firstly, as can be seen from , H1 which states that attitude towards commercialisation positively influences commercialisation practices intention is fully supported. This conclusion is in line with the conceptual model (). This finding is consistent with prior studies linking attitude with intention in Mexico (Martínez-García, Dorward and Rehman, Citation2013), Brazil (Borges et al., Citation2014) and the Netherlands (Bruijnis, Citation2013). The second hypothesis, H2, is also supported as subjective norms do significantly influence commercialisation practices intention positively as can be seen in the correlation matrix (). Thirdly, hypothesis 3 suggested that there is a positive relationship between perceived behavioural control and intention to engage in commercialisation practices that enhance village chicken commercialisation. This hypothesis is also supported as per the conceptual model and results in . These results are consistent with prior studies by Borges et al., (Citation2014). Borges et al., (Citation2014) posited that the higher the perceived capability to adopt a practice, the greater the intention of farmers to use this practice.

The fourth hypothesis suggesting that commercialisation practices intention (CPI) positively influences commercialisation scaling up intention (CSI) is also supported as per the results in . This means that the farmers with higher intentions to adopt the appropriate commercialisation practices (i.e. management practices, investment practices and marketing practices) in their indigenous chicken enterprises, are the ones whose commercialisation scaling up intention will be higher or stronger. These results are in line with an observation made by Justus et al. (Citation2013, pp.52);

“To achieve increased productivity, extension service has continuously disseminated management interventions to smallholders for mitigating these challenges. However, majority of smallholder farmers with smaller flock size hardly realize improved productivity, which could be explained by how they selectively adopt or refuse to adopt disseminated management interventions package, production practices and … .”

From the above statement, we can fairly say that farmers fail to transition from subsistence systems to commercial systems of agriculture partly because of failure on their part to adopt the necessary practices.

Lastly, the study found significant gender differences in all aspects of the model except for subjective norms. On the significant gender differences, the male farmers exhibited higher means than the female farmers on attitude towards commercialisation and perceived behavioural control. The findings for men having a more favourable attitude towards commercialisation of the indigenous chickens than females are consistent with prior studies which show that agricultural commercialization is often associated with a decline in women’s control because cash crops usually fall into the male domain (Fischer & Qaim, Citation2012). The perceived behavioural control for male farmers was higher than female farmers and this could be attributed to the gender bias where men have an advantage when it comes to access to productive resources as evidenced in the literature (Fischer & Qaim, Citation2012). The findings on subjective norms which found a slight difference with men still higher than women on approval from important others are interesting. This means that the approval to engage in commercialisation behaviour of the important others to both male and female farmers is almost the same with little, albeit, insignificant gender bias. These findings contradict the gender bias stereotype where women are in most cases expected to perform household chores and focus on subsistence farming.

The gender differences in commercialisation practices intention and scaling up intention were significant with male farmers recording higher means than female farmers. This finding is consistent with findings on gender and agriculture commercialisation that men are more likely to take advantage of commercialised value chains than women.

5. Conclusions

Buttressed by the underutilised theory of planned behaviour in smallholder commercialisation decisions, the focus of this study was twofold. Firstly, the study sought to examine the role of socio-psychological factors in indigenous chicken smallholder farmer commercialisation intentions. Secondly, the study explored gender differences concerning the levels of commercialisation intention among the smallholder farmers. From the findings, it is clear that there is a positive relationship between the attitudinal antecedents and commercialisation practices intention. The hypotheses on gender differences were partially supported as the male farmers exhibited higher means than the female farmers on attitude towards commercialisation and perceived behavioural control; men were still higher on subjective norms, albeit, statistically insignificantly.

5.1. Contributions to knowledge and practical implications

The study was the first one to apply the theory of planned behaviour in the indigenous chicken value chain as well as in the Zambian context. Secondly, the study filled the knowledge gap regarding understanding gender differences among smallholder farmers in the indigenous chicken value chain.

Women, without doubt, dominate the number of participants in the production of indigenous chickens and the need for them to transition from subsistence to commercial production of indigenous chickens cannot be overemphasised. The study implications for policymakers and developmental organisations is that there is a need for interventions that will emphasise more support for women as it is them that dominate the indigenous chicken value chain. Mapiye et al. (Citation2008) suggest that the essence of carrying out a gender analysis is to ensure that appropriate constraints and opportunities are identified to prevent misdirecting of technologies and services to the wrong gender group. Additionally, Assan (Citation2014) observes that the declining livestock productivity in rural areas is due to a large extent the relegation to the background of the contributions of women on the issues of livestock production. Interventions should target enhancing the attitude towards commercialising by promoting the potential benefits of commercialising the indigenous chickens. Interventions to improve the perceived behavioural control of women farmers such as the provision of training, extension services and other business development services should be sustained so that adopting commercialisation behaviour should be seemingly achievable for them. Improving the attitudinal antecedents of commercialisation for women will increase the chances of making their commercialisation intent even stronger and a stronger commercialisation intention is likely to result in actual commercialisation behaviour.

5.2. Limitations of the study and directions for future research

Like any other study, this research has limitations. Firstly, the empirical study was cross-sectional meaning that the results are correlational and do not infer causality. Thus, there is a need for longitudinal studies that would incorporate the effects of interventions to enhance the adoption of commercialisation behaviour by women farmers. Secondly, future studies using panel data may also include the actual commercialisation behaviour to assess the relationships among commercialisation practices intention, intention to scale up and actual commercialisation behaviour.

Thirdly, commercialisation practices intention was conceptualised as a unidimensional (composite) construct. This conceptualisation may not allow the scholars to see the independent relationships between the individual commercialisation practices intention dimensions and scaling-up intention. Future studies may consider examining the commercialisation practices intention as a multi-dimensional construct. Fourth, the context of the study is one district in north-western Zambia and this limits generalisability in other contexts; future studies may consider increasing the geographical scope.

Lastly, only bivariate relationships using correlations analyses were ascertained but there’s a need for future studies to consider using structural equation modelling, a multivariate technique to ascertain the complex relationships as well as the possible mediated effects of commercialisation practices intention.

Acknowledgements

Authors are grateful for the financial support rendered in the Value-Chain Innovation Platforms for Food Security in Eastern and Southern Africa (VIP4FS) project funded by the Australian Centre for International Agriculture Research (ACIAR) and led by the World Agroforestry Centre ((ICRAF) in Kenya, the Copperbelt University and Zambia Agricultural Research Institute (ZARI) in Zambia

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Bruce Mwiya

The authors belong to the Copperbelt University School of Graduate Studies, P.O. Box 21692, Kitwe, Zambia. This article is one of the many outcomes of the village chicken commercialisation project.

Notes

1. Value-Chain Innovation Platforms for Food Security in Eastern and Southern Africa (VIP4FS) funded by Australian Centre for International Agriculture Research (ACIAR) and led by World Agro forestry Centre ((ICRAF) in Kenya, the Copperbelt University and Zambia Agricultural Research Institute (ZARI) in Zambia

2. ** statistically significant at 1%

References

- Acker, S. (1987). Feminist theory and the study of gender and education. International Review of Education, 33(4), 419–21. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00615157

- Alders, R. G., & Pym, R. A. E. (2009). Village poultry: still important to millions, eight thousand years after domestication. World's Poultry Science Journal, 65(2), 181–190, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043933909000117

- Arslan, A., Adeel, R., Muhammad, A., & Hanan, I., et al. (2013). Gender Effects On Entrepreneurial Orientation And Value Innovation: Evidence From Pakistan. European Journal of Business and Social Sciences, 2(1), 82–90 http://www.ejbss.com/recent.aspx.

- Aryemo, I. P., Akite, I., Kule, E. K., Kugonza, D. R., Okot, M. W., & Mugonola, B. (2019). Drivers of commercialization: A case of indigenous chicken production in northern Uganda. African journal of science, technology, innovation and development, 11(6), 739–748, https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-18bf76b906

- Assan, N. (2014). Gender disparities in livestock production and their implication for livestock productivity in Africa. Scientific Journal of Animal Science, 3(5), 126–138 https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20143216865.

- Bergevoet, R. H. M., & Woerkum, C. V. (2006). Improving the entrepreneurial competencies of dutch dairy farmers through the use of study groups. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 12 (1) 25–39 . https://doi.org/10.1080/13892240600740852

- Bergevoet, R. H. M., & Woerkum, C. V. (2007). Improving the entrepreneurial competencies of dutch dairy farmers through the use of study groups. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13892240600740852

- Borges, J. A. R., Lansink, A. G. O., Ribeiro, C. M., & Lutke, V. (2014). Understanding farmers’ intention to adopt improved natural grassland using the theory of planned behavior. Livestock Science, 169, 163–174, 10.1016/j.livsci.2014.09.014

- Borges, J. A. R., Oude Lansink, A. G. J. M., Marques Ribeiro, C., & Lutke, V., et al. (2014). Understanding farmers’ intention to adopt improved natural grassland using the theory of planned behaviour. Livestock Science, 169(C), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2014.09.014

- Bruijnis, M., Hogeveen, H., Garforth, C., & Stassen, E. (2013). Dairy farmers' attitudes and intentions towards improving dairy cow foot health. Livestock Science, 155(1), 103–113, 10.1016/j.livsci.2013.04.005

- Bwalya, R., & Kalinda, T. (2014). An analysis of the value chain for indigenous chickens in Zambia’s Lusaka and Central Provinces. Journal of Agricultural Studies, 2(2), 32. https://doi.org/10.5296/jas.v2i2.5918

- Constance, D. H., & Choi, J. Y. (2010). Overcoming the barriers to organic adoption in the United States: A look at pragmatic conventional producers in Texas. Sustainability, 2(1), 163–188. https://doi.org/10.3390/su2010163

- Dolberg, F. (2007). “Poultry production for livelihood improvement and poverty alleviation.” Poultry in the 21st century: Avian Influenza and beyond. Proceedings of the international poultry conference, held. 2007, 1–26. 2005.

- Dugan, R. E. (2008). Gender Bias. Vincent, PN: Encyclopedia of social problems. Sage Publications, 390–392. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/encyclopedia-of-social-problems/book229800#description

- Fischer, E., & Qaim, M. (2012). Gender, agricultural commercialization, and collective action in Kenya (pp. 441–453).

- Gebremedhin, B., & Jaleta, M. (2010). Commercialization of smallholders: Is market participation enough? ( No. 308-2016-5004). https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.96159

- Gerstel, N., & Clawson, D. (2014). Class advantage and the gender divide: Flexibility on the job and at home. American Journal of Sociology, 120(2), 395–431. https://doi.org/10.1086/678270

- Hailemichael, A., Gebremedhin, B., & Tegegne, A., et al. (2017). Status and drivers of village poultry production and its efficiency in Ethiopia. NJAS - Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 83(July), 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2017.09.003

- Hair, J. J., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E., et al. (2014). Multivariate Data Analysis (7th ed). Pearson Education Limited.

- Hansson, H., Ferguson, R., & Olofsson, C., et al. (2012). Psychological constructs underlying farmers’ decisions to diversify or specialise their businesses - an application of theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 63(2), 465–482. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-9552.2012.00344.x

- Hattam, C. (2006). Adopting organic agriculture: An investigation using the Theory of Planned Behaviour (No. 1004–2016–78538).Queensland, Australia from International Association of Agricultural Economists Conference, August 12-18, 2006, I–16, DOI: 10.22004/ag.econ.25269

- Justus, O., Owuor, G., & Bebe, B. O. (2013). Management practices and challenges in smallholder indigenous chicken production in Western Kenya. Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in the Tropics and Subtropics (JARTS), 114(1), 51–58, urn:nbn:de:hebis:51–58

- Justus, O., Owuor, G., & Bebe, B. O. (2013). Management practices and challenges in smallholder indigenous chicken production in Western Kenya. Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in the Tropics and Subtropics (JARTS), 114(1), 51–58, urn:nbn:de:hebis:51–58

- Khapayi, M., & Celliers, P. R. (2016). Factors limiting and preventing emerging farmers to progress to commercial agricultural farming in the King William’s Town Ares of the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. South African Journal of Agriculture Extension, 44(1), 31–48 .

- Krishnan, S. B., & Peterburs, T. (2017). “Jobs in Value Chains - Zambia”, World Bank Jobs Series Issue No. 6. Opportunities in Agribusiness, No. 6 https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/27007.

- Leavy, J., & Poulton, C. (2007). Commercialisations in agriculture. Ethiopian Journal of Economics, 16 (1), 1–37 https://www.ajol.info/index.php/eje/article/view/39822. Ethiopian Economic Association (EEA), 1997.

- Mapiye, C., Mwale, M., Mupangwa, J. F., Chimonyo, M., Foti, R., & Mutenje, M. J., et al. (2008). A research review of village chicken production constraints and opportunities in Zimbabwe. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences, 21(11), 1680–1688. https://doi.org/10.5713/ajas.2008.r.07

- Mapiye, C., & Sibanda, S. (2005). Constraints and opportunities of village chicken production systems in the smallholder sector of Rushinga district of Zimbabwe. Livestock Research for Rural Development, 17(10), 2005, https://www.lrrd.cipav.org.co/lrrd17/10/mapi17115.htm

- Martínez-García, C. G., Dorward, P., & Rehman, T. (2013). Factors influencing adoption of improved grassland management by small-scale dairy farmers in central Mexico and the implications for future research on smallholder adoption in developing countries. Livestock Science, 152(2–3), 228–238, 10.1016/j.livsci.2012.10.007

- Maumburudze, D., Mutambara, J., Mugabe, P., & Manyumwa, H., et al. (2016). Prospects for commercialization of indigenous chickens in Makoni District, Zimbabwe. Livestock Research for Rural Development, 28(4), 1–13.

- Mwiya, B. M. K., Wang, Y., Kaulungombe, B., & Kayekesi, M., et al. (2019). Exploring entrepreneurial intention’s mediating role in the relationship between self-efficacy and nascent behaviour: evidence from Zambia, Africa. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 26(4), 466–485. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-03-2017-0083

- Niles, M. T., Lubell, M., & Brown, M., et al. (2015). “How limiting factors drive agricultural adaptation to climate change.” Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 200, 178–185. Elsevier B.V. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2014.11.010

- Ochieng, J., Owuor, G., & Bebe, B. O., et al. (2013). Management practices and challenges in smallholder indigenous chicken production in western Kenya. Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in the Tropics and Subtropics, 114(1), 51–58.

- Ochieng, J., Owuor, G., & Omedo Bebe, B., et al. (2012). “Determinants of adoption of management interventions in indigenous chicken production in Kenya.” AfJARE, Vol. 7 No. 1, Accessed 20 August 2017. Available at: http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/156977/2/Ochieng_07_01.pdf

- Pallant, J. (2016). SPSS Survival Manual - A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using IBM SPSS (6th ed). Open University Press.

- Pingali, P. L., Rosegrant, M. W., Schleyer, R. G., Yadav, S. N., & Delgado, C. L., et al. (1995). Agricultural commercialization and diversification: processes and policies water policy for efficient agricultural diversification: market-based approaches agricultural diversification and export-promotion in Sub-Saharan Africa agricultural commercialization. Food Po/Icy, 20(203), 171–185 doi:10.1016/0306-9192(95)00012-4.

- Poole, N. D., Chitundu, M., & Msoni, R., et al. (2013). Commercialisation: A meta-approach for agricultural development among smallholder farmers in Africa? Food Policy, 41(September 2007), 155–165. Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2013.05.010

- Powell, M., & Ansic, D. (1997). Gender differences in risk behaviour in financial decision-making: an experimental analysis. Journal of Economic Psychology, 18(6), 605–628. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-4870(97)00026-3

- Queenan, K., Alders, R., Maulaga, W., Lumbwe, H., & Rukambile, E., et al. 2016. An appraisal of the indigenous chicken market in Tanzania and Zambia. Are the markets ready for improved outputs from village production systems? Livestock Research for Rural Development, 28(10), https://www.lrrd.cipav.org.co/lrrd28/10/quee28185.html

- Quisumbing, A. R., & Pandolfelli, L. (2010). Promising approaches to address the needs of poor female farmers: resources, constraints, and interventions. World Development, 38(4), 581–592. Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.10.006

- Rukuni, M., Tawonezvi, P., Eicher, C., Munyuki-Hungwe, M., & Matondi, P., et al. (2006). Zimbabwe’s agricultural revolution revisited (pp. 119–140). University of Zimbabwe Publications.

- Siegel, B. P. (2008). “Profile of Zambia ’ s smallholders : where and who are the potential beneficiaries of agricultural commercialization ?” Africa Region Working Paper Series, No. 113, p. 63.

- Siyaya, B. J. J., & Masuku, M. B. (2013b). Factors affecting commercialisation of indigenous chickens in Swaziland. Journal of Agricultural Studies, 1(2), 86. https://doi.org/10.5296/jas.v1i2.4016

- Siyaya, B. J., & Luyengo, P. O. (2013). “Factors affecting commercialisation of indigenous chickens in Swaziland.” 1(2). https://doi.org/10.5296/jas.v1i2.4016

- Siyaya, B., & Masuku, M. (2013a). “Determinants of profitability of indigenous chickens in Swaziland.” Business and Economic Research, Accessed 20 August 2017. Available at: http://search.proquest.com/openview/830099682bf15f477fe1d375d9e9c90c/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=1306346

- Sørensen, P. (1996). Commercialization of food crops in Busoga, Uganda, and the renegotiation of gender. Gender and Society, 10(5), 608–628. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124396010005007

- St. John, F. A. V., Edwards-Jones, G., & Jones, J. P. G., et al. (2010). Conservation and human behaviour: lessons from social psychology. Wildlife Research, 37(8), 658–667. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR10032

- Tsusaka, T. W., Orr, A., Msere, H. W., Homann-keetui, S., & Association, E., et al. (2016). Do Commercialization and Mechanization of a “ Women ’ s Crop ” Disempower Women Farmers? Evidence from Zambia and Malawi.

- Wang, J., Chu, M., Deng, Y. Y., Lam, H., & Tang, J., et al. (2018). Determinants of pesticide application: An empirical analysis with theory of planned behaviour. China Agricultural Economic Review, 10(4), 608–625. https://doi.org/10.1108/CAER-02-2017-0030

- World Bank (2009) Gender Equality, Poverty Reduction, and Inclusive Growth, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/820851467992505410/pdf/102114-REVISED-PUBLIC-WBG-Gender-Strategy.pdf

- Yaseen, A., Bryceson, K., & Mungai, A. N., et al. (2018). Commercialization behaviour in production agriculture: the overlooked role of market orientation. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 8(3), 579–602. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-07-2017-0072

- Zewdu, S., Kassa, B., Agza, B., & Alemu, F. (2013). Village chicken production systems in Metekel zone, Northwest Ethiopia. Wudpecker Journal of Agricultural Research, 2(9), 256–262, https://www.academia.edu/download/56916866/Village_chicken.pdf