Abstract

Several data-driven investigations studies examined the association between cultural intelligence and job outcomes (intention to stay, Work performance and organisational citizenship behaviour). It is, however, surprising that the moderating role of psychological capital hasn’t been previously examined concerning cultural intelligence and job outcomes. This relationship is therefore currently under-researched due to sparse contributions. This research investigates psychological capital potential moderating role in the relationship between cultural intelligence and job outcomes to address this gap in the organisation’s literature. Due to this context, the study’s purpose is to support this hypothesis in the data collected from a sample of 246 self-initiated studies on expatriates in 20 Malaysian public universities. Relying on a quantitative method and using Partial Least Squares structural equation modelling to analyse the data, the results reveal that cultural intelligence predicted all three components of job outcomes. Additionally, psychological capital moderates the relationship between cultural intelligence and work performance so that when positive psychological capital is high, the association is more robust. The study has contributed by offering a context-bound approach to refine and integrate the social exchange theory with self-initiated academic expatriates’ cognitive, affective and behavioral processes in the Malaysian situation. Unlike previous studies of working abroad, this study indicates that cultural intelligence can be a salient personal resource for self-initiated expatriates’ academics working in a foreign environment. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed based on the findings of this research.

Public Interest Statement

The current research touched on some very pertinent issues in today’s increasingly global situation. This has resulted in more organizations sending employees to work outside their home countries as expatriates. Therefore, expatriates in this study focused on self-initiated academic expatriates because they travel abroad to work in foreign universities. The goal is to shed light by identifying factors influencing expatriates’ cross-cultural adjustment at work which has become an increasingly important issue for both researchers and players in the industry. This is because it is important to have an in-depth understanding of the individual-level factors that contribute to the formation of such intentions to seek overseas careers. To achieve this main goal, a study has been conducted involving expatriate’s university lecturers from Malaysia public universities in a way that’s adds fresh perspectives on the topic.

1. Introduction

Self-initiated expatriates (SIEs) refer to those individuals who initiate their international assignments and independently look for a job in a foreign country. They represent those talented people who look for opportunities for jobs throughout the world (Haldorai et al., Citation2021; Holtbrügge, Citation2021). Hence, they have no pre-departure training available to them (Space et al., Citation2020). Studies have shown that nearly 50–73% of the global expatriate population are SIEs (Pinto et al., Citation2020). It is documented that cross-cultural researchers have concentrated their workforce experiences in an increasingly global environment. This is because most expatriate and foreign study work tasks focused on individuals’ adaptation, history, and consequences (Kraimer & Wayne, Citation2004; Kraimer et al., Citation2001; Shaffer & Harrison, Citation1998; Wang & Takeuchi, Citation2007). There is evidence to suggest that from recognised multinationals to smaller companies and international joint ventures, many organisations strive to attract international experts in the context of globalisation (Collings et al., Citation2007). Currently, the process and management of expatriation have remained a key challenge in international human resource management (Al Bastaki et al., Citation2021). As a result, international human resource management literature has blurred the boundaries between self-initiated expatriates (SIEs), qualified immigrants, and skilled migrants (Weinar & Klekowski Von Koppenfels, Citation2020). In the past, research on expatriation has mainly focused on employees sent on international assignments by their companies. This is referred to as assigned expatriation. Indicatively, self-initiated expatriation has gained little attention. The term “self-initiated expatriation” gained prominence in recent years, although it relates to a widespread phenomenon (B. Myers et al., Citation2021).

In academics, SIEs have gained prominence through the internationalisation of higher education and strategic alliances between universities in other countries. Notably, the transmission of their skills between countries can only be limited to academics (Selmer & Lauring, Citation2012). Selmer and Lauring (Citation2012) examined why most British academic expatriates who moved to stay in New Zealand, Singapore, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirate (UAE) preferred to travel, sought adventure and private learning, even though more traditional career concerns were expressed. In a later study by the same group, they studied their organisational loyalty. They suggested that the management of academic SIEs concerning associations with home and host countries should be more nuanced, particularly given that these relations were considered to affect a desire to remain in or return home. (Richardson & McKenna, Citation2006).

Few studies have adopted an approach to job outcomes in comprehending the global working environment and personal experience (G. Chen et al., Citation2010). Much previous research has focused in particular on expatriate results such as Intention to Remain (ITR), Work Performance (WP) and Organisational Citizenship Behavior (OCB; Maiti & Bidinger, Citation1981; Wang & Takeuchi, Citation2007). Another research stream focused on individual results for inter-cultural experiences like cognitive complexity and creativity. (Tadmor et al., Citation2012; Tadmor & Tetlock, Citation2006). But results such as ITR, WP and OCB were not studied in cross-cultural literature as beneficial results. By using the psychological capital (Psycap), which is defined as “an individual’s positive psychological state of development” (F. Luthans et al., Citation2007, p. 3), this study introduces job outcomes as an important result of intercultural engagement. Persons moving abroad are inevitably learned to succeed and adjust; examining how psycap becomes pivotal in the motivational process connects with CQ for persons who acquire intercultural knowledge. This research proposes a context in which Psycap is identified as a critical component of related cultural information that accelerates job outcomes. Thus, the introduction of a model builds a cross-fertilization of personal understandings. This investigation proposes that ruminating across these constructs enhances CQ and job outcome variables (ITR, WP and (OCB). To brighten this framework, this study employs Blau’s (Citation1964) Social Exchange Theory (SET) which advocates that the basis of the relationship between employer and employees is underpinned by reciprocity in the workplace. According to Hofmann and Morgeson (1999), the nature of exchange relationships between the organisation and its members would have safety-related implications. Consistently, it has been debated that “relationships evolve into trusting, loyal, and mutual commitments” (Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005, p. 875).

There is sparseness in data-driven research investigating these constructs concerning the influence of multicultural experience relating to CQ on the job results. Previous studies have shown that intercultural perspectives when sojourning abroad give people admittance to new concepts and ideas, inspire them to tackle issues from different perspectives and enhance acceptable thinking and recruitment from unknown sources (Maddux & Galinsky, Citation2009). Through the prism of this framework, (CQ) characterises the extent and course of vigor engaged in learning about and the workings in cross-cultural settings (Ang, Van Dyne et al., Citation2006, Citation2007). Notably, numerous studies have investigated intercultural experiences and their influence which includes influences on constructs such as cognitive complexity, work performance and creativeness. It reflects that CQ underscores the need to further discussion in the current domain (Cheng et al., Citation2006; Leung et al., Citation2008; Maddux & Galinsky, Citation2009; Tadmor & Tetlock, Citation2006). This study considers a cross-cultural environment as a possible place to learn, just like a classroom. We therefore empirically evaluate the association between Psycap and CQ. Given this, we suggest that CQ is linked to intention to remain, which is conceptualised as the intention of a person to stay long-term with their current employer and the opposite of intention to leave.

Further, this study absorbs intention to remain a critical determinant of current turnover conduct (Meyer & Tett, Citation1993). Employees’ attitudes, judgments, and feelings about their readiness to stay in their current organisation are referred to as “intention to remain.” (Tourangeau et al., Citation2010). Previous research has shown that the intention to remain could reduce the amount of money spent on hiring new employees. It is stated that employees who demonstrate a strong want to stay are more successful. They are also more likely to advance their careers inside their existing organisation and, as a result, to contribute their whole efforts to their businesses (Harun, Asiah, Shahid, & Othman, Citation2016). It is impacted by various employee work attitudes, which comprised organisational commitment and job satisfaction, which have been connected to engagement and workplace spirituality (Saks & Gruman, Citation2011). Adding further to the gap in CQ and Psycap literature, existing studies examine job outcomes such as intention to remain need to close the research rank between CQ, Psycap and intention to remain in the context of academic self-initiated expatriates.

The phenomena of those willing to perform “over and above” or “go the extra kilometre” had a long history. Even though the word “OCB” was only coined in the 1980s. (Deniss Deniss Organ, Citation1997). Since then, OCB research has demonstrated significant rapid growth in the interest of researchers, and they have been applying it in different disciplines and, therefore, various types of organisations. (N. P. Podsakoff et al., Citation2009). This citizenship behavior is crucial because it positively influences the persons and the organisational level outcomes (MacKenzie et al., Citation2018). Therefore, it is not surprising that researchers aim to examine the association between CQ and job outcomes, including how moderating variables affect the association between CQ and job outcomes. Our study contributes in three ways to existing literature. First, we offer the study of independent academic expatriates who prefer to domicile abroad via a positive perspective and identify Psycap as a critical cultural intelligence associate. Secondly, we examine the link between CQ and job outcomes. Finally, we look at the role of Psycap as a moderator concerning CQ and job results. Whereas the influences of CQ on employment outcomes (ITR, WP and OCB) are widely documented (Afsar et al., Citation2020; Charoensukmongkol & Pandey, Citation2020; Haniefa & Riani, Citation2019; Nafei, Citation2012; Narayanan & Nirmala, Citation2000; Phenphimol et al., Citation2020; Ratasuk, Citation2020; Xu, Citation2017; Zhang et al., Citation2021), researches regarding the interactive effects of PsyCap (F. Cheung et al., Citation2011; Görgens-ekermans & Herbert, Citation2021; Steven M. Steven M. Norman et al., Citation2010; Roberts et al., Citation2011) as well as the moderating influence of Psycap on the association between CQ and job outcomes (ITR, WP and OCB) hasn’t been previously investigated.

The research problems raised here, therefore, constitutes an under-examined and disregarded problem. Moreover, another untapped research problem is the present state of the existing literature, particularly in the West, across various cultures and sectors. This research is therefore based on interrogating (a) the moderating role of Psycap in the relationship between the CQ and job outcomes (ITR, WP, & OCB) and (b) the cogency of the associations in a context that is socio-culturally diverse and in the academia among SIE. This study is therefore designed to bridge these literature gaps. The study will help determine and develop Psycap resources for SIE academics and show that the academic CQ of SIE can be enhanced by using higher levels of Psycap. This research will help to create the relevant literature. Furthermore, this study spreads the scope of Psycap studies by data-driven studies on academic SIE and the interactive effects of Psycap on CQ and job outcomes.

2. Literature review

2.1. Intention to remain (ITR)

Uraon (Citation2018) defined intention to remain as employees’ high enthusiasm to remain in their workplace based on their experience. This perception was developed through their positive or negative understanding of organisational situations and processes, influencing them to remain or quit the workplace (Bellamkonda et al., Citation2020). Numerous studies have attempted to explain that employees’ intention to remain has been a significant discussion in management. It involved the importance of talented employees to remain in an organisation. In a similar vein, Uraon (Citation2018) noted that intention to stay occurs when it reflects employees’ commitment to their job and organisation for a long-term basis. A literature trend over a decade focuses on staying and its associated factors instead of turnover (Holtom et al., Citation2008). Most research on intention was carried out by Robert et al. (Citation1992) and explained intention as a pre-determined motivation for the actual behaviour. Mustafa et al. (Citation2014) argued that intention itself is the primary determinant for the actual behaviour, such as quitting or staying, performing or not performing. This study defines intention to remain as the willingness of the SIE academics to stay longer in Malaysian. Thus, it would interest to explore intention to stay among lecturers in SIE academics among public universities in Malaysia. Research on employees’ intention to stay has been conducted by several researchers in different contexts, industries, cultures and countries using other variables. Therefore, the way CQ impacts expatriates’ work and career experiences must affect their intentions to remain in the host country (Bozionelos, Citation2020). Therefore, it is important for all stakeholders: SIEs themselves, their host country employers. Hence the need to further interrogate this stream of thought in the SIE context.

2.2. Work performance (WP)

WP is regarded as the skills that employees expect to perform within the workplace to measure the work performance of these skills. Concerning work performance, it is defined as “the extent to which a job is well done” (Campbell & Wiernik, Citation2015). Likewise, the extent to which workers perform work tasks assigned to their employers is often used interchangeably with employee performance or work performance. (Abogsesa & Kaushik, Citation2018; Kahya, Citation2007). In short, a company’s performance can be defined as the collective performance of individual workers. In contrast, individual worker achievement is defined as “an evaluation of an individual’s behavior results: a determination of how well or poorly a person has completed his or her job.” The failure to perform reasonably can lead to concerns about poor performance. WP is a major construct that has been under the scrutiny of scholars for long (Pandey, Citation2019). However, there is no evidence in the literature that CQ is always advantageous in academic SIE work performance. When an employee gets a high WP, it signifies that they have completed job-related activities satisfactorily. As a result, we pay attention to WP, which is defined as the outcome or result of a goal or set of goals for a job or role in an organisation (Campbell, Citation1990). Previous research has found a beneficial association between CQ and WP. However, the link is not as straightforward as it appears. Many pathways translate the impact of CQ on performance outcomes, and more research is needed (Boxall et al., Citation2016; Guest, Citation2011; Jiang et al., Citation2012).

2.3. Organizational citizenship behavior (OCB)

OCB is defined as “individual behavior that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognised by the formal reward system, and that in aggregate promotes the effective functioning of the organisation” (Deniss Deniss Organ, Citation1997). The general notion with OCBs is that if employees develop such extraordinary conduct and go beyond tasks by supporting their businesses, customer satisfaction and organisational performance will be improved. (Messersmith et al., Citation2011). OCB concept approaches from a socio-human perspective, the informal interpersonal relationships, relationships that have a high weight at the organisational level, and that may have a decisive influence on individual and organisational performance. OCB reflects a positive and voluntary individual behavior that is not directly and explicitly requested in an Organisation’s regulations. It contributes to its good functioning (D D. Organ, Citation1988) or in other words, OCB is that addition to the formal content of a contract to hire and create (Frenkel & Sanders, Citation2007). Despite what is known about OCBs, academics in SIE can still expand the current corpus of knowledge. While previous OCB research has made significant theoretical and practical advances, this line of inquiry aims to explain OCBs displayed by SIE academics. The study of OCBs among SIE academics is essential since their job status is sometimes constrained by government laws, resulting in unequal organisational standing and discriminatory labour market treatment (D. Myers & Cranford, Citation1998). Whether SIE academics perceive cultural intelligence due to their self-categorisation as outgroup members in the host country might reinforce their desire to maintain a positive impression by demonstrating and withholding certain work-related behaviours like ITR affiliation-oriented OCBs. However, a minimal scholarly effort has been dedicated to studying how SIE scholars respond to institutional obstacles in a foreign nation like Malaysia.

2.4. Cultural intelligence (CQ)

CQ refers to the ability of an individual to adapt effectively to culturally diverse situations (Earley & Ang, Citation2003). CQ has been categorised as a specific variation of astuteness (Shokef & Erez, Citation2006), showing whether individuals can handle several culturally diverse persons in environments successfully (Earley & Ang, Citation2003). CQ concerns the ability of an individual to adapt through cognitive, behavioral and motivational aspects to new cultural circumstances. (Christopher Earley, Citation2002). It consists of four dimensions, namely, cognitive, metacognitive, behavioral and motivational elements. The cognitive aspect of CQ concerns the explicit knowledge of the standards, values and practices of culture by an individual. This covers the economic, legal and social systems (Brislin et al., Citation2006). The component of motivation describes how an individual can focus his energy on the successful functioning of culturally diverse situations (Earley & Ang, Citation2003). The behavioural aspect is the person’s ability to show adequate verbal and nonverbal communication (Earley & Ang, Citation2003). The academic literature of recent years has mainly decided that CQ is a predictor of performance outcomes. For instance, it is expected that more culturally intelligent people will achieve better results than those not so culturally intelligent (Ang, Van Dyne et al., Citation2007). CQ was a crucial factor in the performance of expatriates (Lee & Sukoco, Citation2010). Even though lots of work is being done on CQ in several settings, its role concerning how it affects the results of multicultural creativity has been considerably less scrutinised (Hu et al., Citation2017). The importance of CQ in explaining successful expatriation cannot be overstated (Abdul Malek & Budhwar, Citation2013; Ott & Michailova, Citation2018). Prior research on CQ among expatriates, for example, has focused on positive outcomes such as adjustment (Lee & Sukoco, Citation2010; Wu & Ang, Citation2011), cross-cultural effectiveness (Lee & Sukoco, Citation2010), expatriates’ satisfaction with their job assignment and living in their current country and expatriate performance (Lee & Sukoco, Citation2010). Some researchers also claim that expatriates’ CQ benefits knowledge sharing, international opportunity, recognition and innovative behaviours (Lorenz et al., Citation2018). Despite past evidence of the impact of CQ on other aspects of expatriate performance, the research on the significance of expatriates’ CQ in supervisor-subordinate work interactions is scarce. According to a previous study, CQ is a critical competency that enables individuals to build strong relationships with culturally varied co-workers and lead individuals from many cultures to work effectively as a team (Presbitero & Toledano, Citation2018). Given these advantages, CQ could be critical in assisting expatriates in supervisory positions to develop favourable connections with local subordinates in the host country where they work.

2.5. Extrapolations in social exchange theory

The SET theory is the lens under which this study will be investigated. According to social exchange theory, parties must abide by specific “rules” of exchange processes, better known as “reciprocity” or “repayment”, to ensure that their relationships evolve into remaining in the organization, increased OCB, and higher performance (Blau, Citation1964). Gouldner and Gouldner (Citation1960) posits that without formal obligations for reciprocity, involved parties are likely to rely on norms of reciprocity to manage interactions and ensure the success of their exchanges. Although norms of reciprocity may be universally accepted, evidence suggests that there are also cultural and individual differences in the extent to which people endorse and engage in acts of reciprocity (Emerson & Emerson, Citation1976; Hoppner et al., Citation2015). In other words, reciprocity involves the cultural norms and expectations that people will get what they deserve in a social exchange process and thus may differ from culture to culture. In our view, these theoretical arguments emphasize the validity of our model. The principle of reciprocity from the social exchange theory also explains the positive consequences of psychological capital. If employees feel supported, they are likely to return the appreciation by showing higher psychological capital, which raises the expectation to be rewarded for it (Kurtessis et al., Citation2017). The theory of reciprocity (SET) is a potent mechanism for explaining the relationship between favourable organisational inputs and employees’ reactions via attitudes and behaviours (Blau, Citation1964). Employers will reward employees with greater levels of Psycap since they will be perceived as more valued exchange partners as stipulated based on the social exchange theory (Blau, Citation1964). Employers will be more willing to form exchange relationships with high Psycap employees due to this value, resulting in more reciprocal positions for high Psycap individuals. As a result, high PsyCap persons who are more confident, optimistic, hopeful, and resilient than others would obtain higher performance assessments from employers.

To put it another way, reciprocity refers to the cultural norms and expectations that people will receive what they deserve in a social trade process, and it varies by culture. The concept of SIE academic employees’ CQ is founded on social exchange theory. Cropanzano and Mitchell (Citation2005) define rules and norms of exchange as a “cultural mandate” that requires individuals to adapt their cognitive processes, attitudes, and behaviours to the cultures of their partners. Adjusting in this way might make interaction partners feel appreciated and valued. Those with a high CQ, in particular, carefully apply cultural knowledge and show culturally acceptable attitudes and behaviours in social interactions with clients from many cultures. In reply, reciprocity norms predict that these academic expatriates will reciprocate by improving their work performance, displaying OCB, and showing ITR to maintain the social exchange (Blau, Citation1964; Chan et al., Citation2010). Those with a low CQ, on the other hand, are less worried about cultural commitments and are less likely to notice if cultural interactions are not returned. This leads to negative reciprocity, as academic expatriates are more likely to receive bad treatment in exchange for poor experiences (Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005).

2.6. Cultural intelligence (CQ) and the intention to remain (ITR)

Sojourning in an unaccustomed cultural environment is a major stress that must be adapted to unfamiliar physical and psychological experiences (Bochner, Citation2003). A higher level of CQ and adjustment is required for these uncertain circumstances. ; P. C. Earley & Peterson, Citation2004) as well as Templer et al. (Citation2006) demonstrate that CQ is a precondition for fruitful cross-cultural adjustment in new cultural environments for work, life and interactions. In addition, CQ is necessary to develop good working relations. (Triandis, Citation2006). Since people with higher CQ have more significant exchanges with individuals from diverse cultures and backgrounds, they most likely tend to be open-minded and curious about other cultures (Khodadady & Ghahari, Citation2011). Intercultural situations draw those with a high level of motivational CQ from their appreciation of the advantages of intercultural interactions. They also depend on their ability to address their challenges when they leave their homeland (Dyne et al., Citation2012). CQ deals with one’s strategic reflection on cultural differences. Demonstrating more excellent CQ makes it possible for persons to comprehend the significance of preparing or planning intercultural connections when they live and work abroad. Cross-cultural training programs or the exposition of culturally different standards and values before intercultural interactions are prepared and planned (Dyne et al., Citation2012). These preliminary phases can be an important predictor of working outside one’s own country while comprehending how different cultures are similar and reflect cognitive CQ. Given that the willingness to adjust to oral and non-oral behavior according to the cultural environment requires living and working in a new intercultural context, a high standard of compartmental CQ can have a significant impact on the intent to remain on the work.

Based on Proposition 1 and the known previous literature, coupled with this study’s new business and industry setting, the following hypothesis is posited:

H1: CQ will significantly affect ITR.

2.7. Cultural intelligence and work performance

An individual who is culturally adaptable recovers easily when situations go wrong. They enjoy being exposed to the different behavior of other cultures and maintain personal identity when exposed to different cultural values. Shaffer et al. (Citation2006) considered cultural adaptation an affective outcome because it represents subjective assessments with affective implications. Every individual differently perceives the foreign settings in terms of culture, language, and so on. If their judgment (which is subjective) about these is favourable, then the affective or emotional feelings will also be positive and vice versa. Earlier researchers have found that individuals with a high level of CQ are better able to adjust to the host culture environment (Chuah Ramalu & Rose, Citation2011; Earley & Ang, Citation2003; Kumar et al., Citation2008a).

Further, researchers have also found a positive relationship between CQ and job performance; that is, individuals who can adjust themselves in cross-cultural situations can perform the task assigned to them in a better way (Kumar et al., Citation2008a). A culturally intelligent person will be able to understand and interact with people of other cultures, and as a result, this will increase their performance. Intercultural competencies are also expected to reduce the misunderstandings in role expectations and eventually enhance performance. Though various researchers have revealed a direct impact of CQ on job performance the other hand, researchers (Kumar et al., Citation2008b; Sri Ramalu et al., Citation2012) have also explained that managers with higher CQ have failed in their out of home state assignments due to lack of adaptability. Even though the employees have high CQ, their performance is likely to suffer if they cannot adapt themselves to the new environment (Karaevli & Tim Hall, Citation2006). A successful adaptation in local culture reduces stress and strain, which may improve their performance (Kraimer et al., Citation2001). A multicultural study by researchers found a substantial correlation between CQ and an employee’s performance (Amiri, Jandghi et al., Citation2010).

Furthermore, a large sample of expats in Malaysia showed that the association between CQ and its contextual achievements was positive and significant (S. S. Ramalu & Rose, Citation2010). Another study conducted in India revealed that the relationship between CQ and task performance is mediated by cultural adjustment (Jyoti & Kour, Citation2017b). In addition, Wen (Citation2019) revealed findings that showed a connection between CQ and work performance. Although more data-driven evidence is still being churned out on the topic, literature on the relationship concerning the above studies supported the assumption that a positive and important link existed.

Based on Proposition 2 and the known previous literature, coupled with this study’s new business and industry setting, the following hypothesis is posited:

H2: CQ will significantly affect WP.

2.8. Cultural intelligence and OCB

A multidimensional structure that belongs to the casual elements of organisational behavior with a marked voluntary nature that extends beyond the demands of an organisation and does not have the objective to achieve an award by contributing directly or indirectly to the organisation’s increase may be defined as OCB (Ang, Van Dyne et al., Citation2006; Chiaburu et al., Citation2011). We expect positive and significant correlations between OCB and CQ because OCB is inherently a discretionary behavior determined mainly by individual will, and CQ relies heavily on intercultural openness. People with a high level of intellectual transparency, continuous learning, knowledge sharing, motivation to learn, social concern tend to be more proactive/dynamic (Fuller & Marler, Citation2009). We believe that by behaving in ways relevant to the setting in which they find themselves, culturally intelligent employees will be better able to improve their personal and their organization’s outcomes. For example, understanding role perceptions may lead to increased group or unit cohesiveness and, as a result, to more profitable outcomes, such as higher customer satisfaction.

Furthermore, managers who are more culturally intelligent will be more successful in creating an environment (i.e., antecedents and consequences) that encourage citizenship behaviour (C. Earley & Calic, Citation2016). A manager who is familiar with the principles of justice in the host country, for example, is less likely to use noncontingent punishment and reward, which might harm subordinate citizenship behaviour and hence organisational performance. The ability of a culturally knowledgeable employee to practice proper citizenship behaviours is more likely to lead to better work performance. They are also less likely to misinterpret positive work performance evaluations because they are culturally intelligent, which can lead to the display of additional citizenship behaviours, such as offering the manager valuable suggestions that improve unit effectiveness, reduce costs, or free up the manager’s time to focus on more productive tasks (C. Earley & Calic, Citation2016). Much more, because intellectual openness has the highest correlation, all personality features, with general mental capacity among employees with high levels of intellectual openness, tend to understand better the task context that should lead to high OCB and CQ levels. Our study aims from these premises to verify the intuitive assumption that OCB is directly related to CQ and to highlight this relationship intensity.

H3: CQ will significantly affect OCB.

3. Theoretical framework

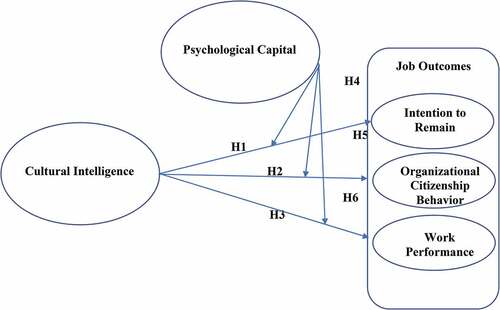

The model shows how CQs directly affect three outcomes’ variables for employees (see ). These are namely ITR WP and OCB. Next, through Psycap, we display a moderation association between CQ and the outcomes. While specific studies have been testing the associations between CQ and other results, there has been no research concerning CQ and ITR, WP and OCB in the realm of academic SIE. In CQ and Psycap research, testing these relationships is new. The literature has indirectly analysed other relationships in the model. The application of psycap can be measured, strengthened and managed because it is generally associated with the psychological aspect and its impact on performance and positive organisational results. (Fred Luthans, Citation2002; Fred; Luthans & Youssef, Citation2004; Fred; Luthans et al., Citation2006). Thus, Psycap components comprise self-efficacy, hope, optimism, and resilience. They institute positive PsyCap as a whole (Larson & Luthans, Citation2006; Fred; Luthans et al., Citation2008) PsyCap is also supported empirically in some studies second-order variable (sometimes referred to as the higher-order construct). (Avey et al., Citation2009, Citation2010; Görgens-ekermans & Herbert, Citation2021; Fred; Luthans et al., Citation2007; S. M. S. M. Norman et al., Citation2010; Steven M. Norman et al., Citation2010). CQ is considered the ability of a person to develop a synergy of associations that successfully manages cultures. Consequently, “The ability of a person to function and effectively manage in cultural contexts” is considered to be CQ (Earley & Ang, Citation2003, p. 336). Individuals who have high CQ will be seen as being capable of making accurate, complicated and confusing assessments of intercultural situations and adjustments in their understanding, relation and leadership” (Van Dyne, Citation2009 p. 4). CQ can take critical intentional actions in unfamiliar intercultural contexts in each of these situations to offer leaders and other personnel from an outside culture with the ability to interpret unfamiliar behaviors and situations as insiders in this culture.” Van Dyne, 2009 p. 4).

4. Psychological capital as a moderator

Psychological capital comes from positive psychology and underlines a sequence of gifts owned by a person (Fred Luthans & Youssef, Citation2004). Psycap means a “positive developmental psychological state” with four facets: (2) optimism, (3) hope, and (4) resilience; (Luthans et al., Citation2007). Self-efficacy means believing that our cognitive resources can be activated to achieve specific results. Self-efficacy reduces pressure and enhances active management and constructive thoughts (Shen, Y., & Hall, Citation2009). Secondly, optimism means that a positive event can be seen as an inner, lasting, prevalent and undesirable event. This dimension concerns a particular attributive style. Optimism enables individuals to acknowledge positive results rather than acknowledge positive events (Hayes & Loeb, Citation2007; Fred; Luthans et al., Citation2008). The third dimension, which is hope, is defined as the power and path to achieve one’s goals, is, therefore, willpower (the commitment to an objective) and elasticity (the power to create substitutes; Avey et al., Citation2009; Fred; Luthans & Youssef, Citation2004). Finally, the dimension of resilience is the ability to rebound from undesirable situations like hardship, struggle and disappointment. Resilience among every sub-part of stress management is perceived as the most vital constructive resource (Fred Luthans, Citation2002). Luthans et al. (Citation2006) revealed the Psycap as a higher-order construct comprising a common alteration between the four dimensions. In the same vein, Psycap is studied by showing that Psycap of a higher order has better explicative power than any subcomponent to predict job outcomes. The influence of Psycap on job outcomes does appear to be strong associations with Psycap in other attitude variables, even though few investigations have been carried out in that reality. A Meta-analyzes on the influence of Psycap on the attitude of 12, 567 employees shows that employees with improved Psycap are probable to be more pleased with their work and more dedicated to the organisation (Avey et al., Citation2011). As high-level employees expect great things on the job, they are expected to be excited about their job performance (Avey et al., Citation2011). It is not only a matter of exploring the impact of the positive qualities of people, but also of knowing the psychological resources needed to improve job outcomes (Alessandri et al., Citation2018; Bergheim et al., Citation2015; Yildiz, Citation2019). This postulation shows that Psycap reflects employees’ behaviour and therefore has a substantial influence on the consequences from organisations (Youssef & Luthans, Citation2009). In a similar study carried out by Fred Luthans et al. (Citation2008) on staff operating in several units, Psycap seemed to be connected with constructive emotions, attitudes (engagement and cynicism), OCB, and deviant behaviours employees. According to previously reported but consistent research, Psycap can increase employee performance, leading to positive attitudes, intentions (e.g., intention to stay), and “discretionary” behavior like the OCB, resulting in required results. Bitmiş and Ergeneli (Citation2013) revealed a positive correlation between Psycap and confidence in management and group trust. It is incredibly fascinating to examine whether Psycap will moderates the relationship between CQ and the job outcome of an employee. In other words, individuals with a high CQ and a high Psycap will be more likely than those who are low in one of these variables to show higher work performance. Given the previous literature supporting every association, it is possible that between these constructs, a collaborating consequence may have a different effect on the above-mentioned relationships.

Hypothesis 4: The relationship between CQ and ITR becomes stronger when employees have high psycap than when employees have low Psycap.

Hypothesis 5: The relationship between CQ and WP is higher when employees have high Psycap than when employees have low Psycap.

Hypothesis 6: The relationship between CQ and OCB is stronger when employees have high Psycap than when employees have low Psycap.

4.1. The malaysian context of self-initiated expatriates

Malaysia, for example, is described as a unique country that seeks to attract and retain globally talented individuals (Yeung et al., Citation2008). To make the current study more relevant, the focus is on academic SIEs in Malaysian public universities. Malaysia is a culturally varied country, with Malays as the dominant ethnic group and Chinese and Indians as the primary minority groups, all of whom have worked hard to preserve their cultural heritages in the six decades since the country gained independence from the British. As a result of this cultural diversity, there is no distinct “Malaysian” work ethic or management style (Sakikawa et al., Citation2017), which many expatriates have regarded as challenging and intriguing. Arokiasamy and Kim (Citation2020) Malaysians, for example, are said to be more open as a people as a result of their country’s diversity, at least when contrasted to more homogeneous societies like Japan.

Furthermore, the relatively modern infrastructure and recreational amenities, particularly in large cities, have been demonstrated to facilitate expatriate transition (Arokiasamy & Kim, Citation2020; Richardson et al., Citation2018). Given the lack of studies on expatriates in Malaysia (Arokiasamy & Kim, Citation2020), these new extrapolations in literature are conceivably comprehensible. Halim et al. (Citation2020) justified that the rapid growth and increasing tendency in the number of expats in Malaysia has increased the need for research and understanding of how these expatriates adjust to a developing country like Malaysia their missions. Despite the availability of research on expatriation, particularly on expatriate adjustment, evaluations indicate that empirical studies on expatriate adjustment in a developing, multiracial society are still limited (Halim et al., Citation2020). Asides Hafitah Mohd Tahir (Citation2007) who examined cross-cultural impediments; Sri Ramalu et al. (Citation2010) on individuals and cross-cultural issues; (Halim, Citation2016) on the mediating effects of communication and interaction; and Elahi et al. (Citation2019) on identifying the challenges faced by expatriates during knowledge transfer, it can be said that very limited research on academic SIE in Malaysian public universities focusing on the job outcomes constructs.

5. Methods

5.1. Measures

Intent to remain is measured by McCain’s Intent to Stay scale. The scale is a four-item subscale from the McCains Behavioral Commitment Scale. It is rated on a five-point Likert scale with 1 indicating strongly disagree and 5 indicating strongly agree. The overall alpha was reported as 0.88 (Mccloskey & Mccain, Citation1987). The alpha coefficient of the scale in the present study was 0.75.

Work performance was measured by six self-report items based on prior measures(Brockner et al., Citation1992). Example items are “I intentionally expend a great deal of effort in carrying out my job” and “The quality of my work is top-notch”. It is rated on a five-point Likert scale with 1 indicating strongly disagree and 5 indicating strongly agree.

OCB measurement was adopted from William and Anderson (Citation1991) consist of 14 items measured using a five-point type Likert Scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). In previous studies, the instrument was reported to have Cronbach’s alpha of .702 and .80 (Singh & Koleker, Citation2015).

CQ was measured with a motivational cultural intelligence instrument by Ang et al. (Citation2007). A seven-point Likert scale with values from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7(strongly agree) has been used to measure CQ. One example includes “I love to live in cultures unknown to me.” It has a Cronbach Alpha of 0.83.

Psycap- Psychological capital is measured using the scales made by F. Luthans et al. (Citation2007), which consists of twelve items: For each sub-scale, the sample items contain: for hope: “I always look on the bright side of things concerning the things I experience in other cultures” efficacy: “I feel confident that I can analyse an unfamiliar culture to understand how I should behave,” and resilience: “I usually handle difficulties in any way when travelling abroad.” “I believe in achieving goals that are important to me.” and optimism (two items; e.g., “I always look on the bright side of things regarding my job”). Respondents rated all items on a five-point Likert scale (1 = SD 5 = SA). The 0.74, 0.74, 0.85, 0.75 and 0.75 respectively.

5.2. Data collection and sample

Data was collected using a questionnaire among self-initiated academic expatriates in 20 Malaysian public universities to test our hypotheses. Two mediums were adopted for the data collection procedure; personally, administered questionnaires and sent via email. Public universities are the focus of this research due to budget reductions suffered by Malaysian public universities. These universities need to rely more on foreign lecturers than private universities with sufficient budgets to pay for domestic academic staff (Hoque et al., Citation2010). The data was sourced from the Department of Human Resource and registrar offices of each respective university. Two hundred forty-six valid surveys were obtained out of 1,595 self-initiated academic expatriates considered from the total population. Personally, the administered questionnaire has some advantages, which includes guaranteeing a high response rate, reduction in interview biased and it also leads to the benefit of mutual personal contact (Dovjak & Kukec, Citation2019). Data were screened for missing data, multivariate outliers, linearity, normality, and homoscedasticity using procedures suggested by (Mertler & Vannatta, Citation2005). All variables used in the research models have fewer than 5% of missing cases. After 27 cases were identified as multivariate outliers, they were deleted, resulting in a final sample size. The computed sample size of 246 is based on the Dillman et al. (Citation2008) mathematical illustration, compatible with the Krejcie et al. (Citation1970) sample size determination table. In this study, non-probability purposive sampling (quota sampling) was employed to determine the sample size for each stratum. Thus, unequal variability was observed among stratum (university). Their assessment, on average, participants worked as expatriates for 5.5 years, and 63 per cent said they had advanced CQ abilities. The average working years were 40.4 years and the average working years were 16.6 years.

6. Results

6.1. Descriptive statistics

We conducted descriptive statistics and correlations among the study variables using SPSS version 20 (Morgan et al., Citation2012). The exogenous latent constructs were significantly and positively correlated with each other (see, ; Piedmont Citation2014). Based on the above descriptive statistics (), the mean value for work performance is 6.033, which is relatively higher than the remaining dependent variables. The descriptive analysis also shows that intention to remain has the lowest mean value of 2.660. The mean score for organisational trust of 5.104 is relatively lower than the mean score for CQ of 5.417 but moderately higher than for psychological capital of 4.689. The mean value for OCB is 3.649.

Table 1. Correlation matrix of the exogenous latent constructs

Table 2. Results of descriptive statistics of the study variables

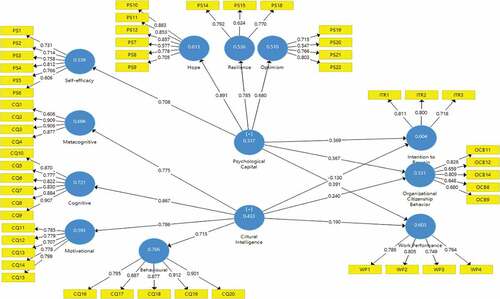

6.2. Measurement model

Consistent with the outer loading rule of thumb claimed by Vinzi et al. (2010), the outer loading must be 0.50 and above. Therefore, the average variance extracted must be more than 0.50. Hair et al. (Citation2014) recommended that the values that factor loading below 0.50 will be deleted beginning from the lowest value. By deleting those, it will improve the quality of comprehensive data. The reliability and validity of the measuring model have been tested in the first stage of the analysis. Internal coherence was assessed by the internal reliability of the measurements (composite reliability, CR). The CRs were between 0.774 and .942, which was above the frequently accepted 0.70 thresholds.(Hair et al., Citation2014). Besides, convergent validity (average variance extracted, AVE) and discriminant validity Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) were examined to evaluate the construct validity of the measurements (Bagozzi, Citation1992; G. W. Cheung & Wang, Citation2017; Hair et al., Citation2014; Refer ). The AVEs were between 0.513 and .766 and confirmed the convergent validity described by Cheung and Wang (Citation2017). They maintained that AVE is considered adequate if the AVE is not substantially less than 0.5 and all items’ standardised factor loads are not significantly less than 0.5. Furthermore, the square root of the AVE of each building was calculated to establish DV (Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981). The square root of each AVE (on the diagonal) is greater than the correlations between it and all the other model buildings, as shown in .

Table 3. Result of convergent validity

6.3. Common Method Bias

Because all of the answers came from the same place, the CMB is known to exaggerate the importance of the relationships between the variables in the model. Harman’s Single Factor (P. M. Podsakoff et al., Citation2003) and 2) full collinearity evaluation may be used to uncover this possible bias (Kock and Lynn Citation2012). Bagozzi (Citation1992) advised that a Harman single-factor test was conducted to establish that data is free from common method bias/variance. The test revealed that no one factor accounted for more than 50% of the variance since the first factor accounted for only 29.22%.

In addition, the results of the highly recommended technique for diagnosing DV of the Heterotrait monotrait ratio (HTMT) were below the commonly accepted limit of 0.85. Kline (Citation2015) confirmed that the measurement was DV (see, ). Taken together, these findings show that in the present study, common method bias is not a threat. shows all build loading factors, t-value, CR, and AVE. In deciding the conditions for discriminant validity, it was stated by Henseler et al. (Citation2014) that the discriminant validity benchmark of every variables’ AVE should be higher than the construct’s uppermost squared correlation with another latent construct, and the indicators loadings should be higher than all its cross-loadings. Hence, in this research (), the DV of the measures was evaluated through the criterion and the HTMT Ratio.

Table 4. Result of discriminant validity (HTMT)

6.4. Demographic profile of the respondents

As revealed in , the respondents’ profile showed that 85.4 percent of the survey was dominated by males, while the survey respondents replied to only 14.6 per cent (36 females). The majority of respondents are between the ages of 40–49 (41.9%), about 37.4% between the ages of 30 and 39 years and 7.7% between 50–59 years. The age of those over 59 is 11%, and the remaining 2% are under 30. Almost 90.5% of those surveyed were Ph.D.’s/DBA holders concerning education. 8.5% are graduates of master’s degree, and 0.8% are graduates. One (1) interviewee stated that they had further qualifications. Moreover, 90.2% of expatriates were married, compared to 9.3% of the individual. Just one of them is split (0.4 per cent). 64.6% of expatriates come from Asia on the continents of origin, and 31.3% come from Africa. The remaining figures are in Europe (3.3%) and Australia (0.8%). 69.1% of expatriates are professors, 18.7% are associate professors, 4.1% is professors, and assistant professors only left (0.4 per cent). There are, however, also some who have a different responsibility, which is 7.7 per cent. Many expatriates have no previous experience in foreign countries (26%). The majority of expatriates (74%) have worked abroad for years. Those with 1–5 years’ abroad experience ranges from 6–10 years to 25.2 per cent (34.6 per cent). 12.6% have over 10 years of experience, whereas 7.7% have over 30 years of extensive experience. As far as spouse/family is concerned, 75.2% have their wife/family, whereas 24.8% are not. These expatriates also live in Malaysia, where only 2% of them began their lives. They have been living there for less than a year. 32,9% stayed in Malaysia for 1–3 years, 4–6 years (35%), 7–9 years (8,9%), while 21,1% settled in Malaysia for more than 9 years. The majority of expatriates (53.7%) speak the local language poorly. In the local language, 24.8 per cent are rated as fair. However, some have placed the Malay language as excellent and summarised it at 21.6 per cent.

Table 5. Result of the hypothesis assessment

6.5. Assessment of the formative hierarchical component model

Becker et al. (Citation2012) suggested using reflective-reflective second order to assess the dependent variables (ITR, OCB and WP) see, . Therefore, we checked for collinearity of the first order construct and the significance of each reflective construct’s weight (Halim, Citation2016). As presented in , constructs were checked for collinearity in the model, i.e., CQ and Psycap as predictors of ITR, OCB and WP. The variance inflation factor (VIF) values of all the constructs are < 5 (Halim, Citation2016), indicating that they are distinct and measuring different aspects of ITR, OCB and WP. Further, the table shows the first-order constructs are significantly related to ITR, OCB and WP (Significant at 0.01).

Table 5. Demographic profile of respondents

Table 6. Result of assessment of higher-order construct

6.6. Structural model and moderating mechanism hypothesis test

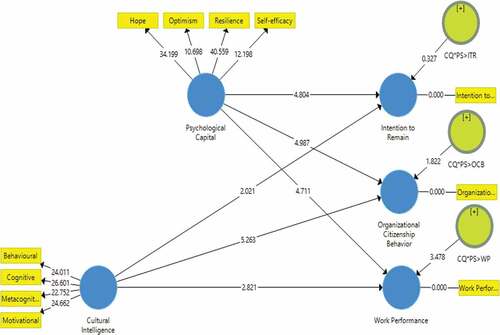

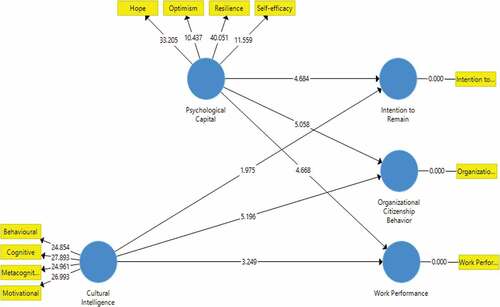

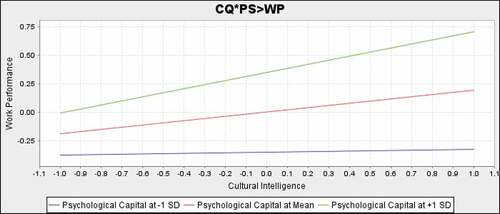

The results of the four PsyCap-based interaction analyses were shown separately in and . The PLS was used directly and indirectly to moderated regression analysis for the direct relationship and moderating analysis. Rasoolimanesh and Ali (Citation2018) indicated the increased use of PLS in SIE academic research; the models were examined. Details show the positive and significant effect of CQ for ITR (β = −0.141; p < 1.0 024), CQ for OCB (β = 0.291; p < .0 00) and CQ for WP (β = 0.215; p < 1.0 001). The following hypothesis: H1, H2, H3 and H6 were all supported. Details are available from the results of the direct analysis. The indirect moderated regression analysis results also show positive and significant effects on SIE academic Psycap work performance. For instance, CQ *PS> ITR (β = 0.023; p < 0.372), CQ *PS> OCB (β = −0.112; p < 0.034), CQ *PS> WP (β = .165; p < .0.000). graphically shows the results of moderation analysis and result.

6.7. Interaction plot

The significant interaction (H6) is plotted in the interaction plot () as recommended by Dawson (Citation2014). reveal that when Psycap is high, the positive relationship of CQ and Job outcomes (WP) becomes stronger. show that when psychological capital is high. The positive relationships for cultural intelligence and work performance of academic SIE become stronger

7. Discussion/interpretation

This study examines how CQ can influence job outcomes. This study established CQ as a significant construct for work outcomes using a broad sample. While studies have looked at the impact of CQ on a variety of psychological and performance outcomes, such as decision making (Ang van Dyne et al., Citation2007), cultural adjustment (Moon & Jung, Citation2012), task performance (Jyoti & Kour, Citation2015) and leadership effectiveness (Rockstuhl et al., Citation2011), Its role as a predictor of metacognitive outcomes has received scant attention. Our findings complement prior findings that CQ can improve job outcomes by increasing employees’ participation in a beneficial process to the organization’s general well-being (B. Chen et al., Citation2015; Kanwar et al., Citation2012). Second, in the context of academic SIE, this study recognises CQ as a valuable resource. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first studies in Malaysia to look at these variables together in public universities. Although many studies have looked into the role of CQ in multicultural interactions, the majority of them have focused on short-term business travellers or international assignees, ignoring the impact of this resource on employees who deal with cultural diversity on a daily basis, such as academic SIE (Kim, Citation2009; Rüth & Netzer, Citation2020; Soon & Van, Citation2008). The findings indicate that CQ directly and significantly affects job outcomes (intention to remain, organisational cultural behavior, and work performance). The results confirm the original framework of CQ that expatriates capable of interacting in different cultures will have a higher level of adjustment, especially in terms of work-related performance (Earley & Ang, Citation2003). The study confirms the proposition that CQ has a significant effect on job outcomes (intention to remain, organisational cultural behavior, and work performance). These results are congruent with previous findings of (Lie et al., Citation2016; Popescu et al., Citation2018a; Setti et al., Citation2020; Stefan et al., Citation2013; Tanova & Ajayi, Citation2016). These findings are a very important part of the contribution of this study and further validate the findings of (Jun, Citation2017) on the relationship between CQ and intention to remain (H1). The results are also congruent with revelations by Popescu, Fistung, Popescu et al. (Citation2018a) and (Narayanan & Nirmala, Citation2000; Shafieihassanabadi & Pourrashidi, Citation2019) supporting the positive relationship between CQ and OCB (H2). Specifically, the research located support for the hypothesized between CQ and WP (H3; Amiri, Moghimi et al., Citation2010; Jyoti & Kour, Citation2017a). As a result, scholars and practitioners have adopted the concept of adjustment proposed by Black in 1988 and have thus supported the idea that expatriate adjustment can determine the level of performance. In addition, there is evidence for conceptual studies implying that high Psycap is related to job performance (Fredrickson, Citation1998, Citation2001, Citation2003; Görgens-Ekermans & Herbert, Citation2013; Avey et al., Citation2010; Luthans, Citation2002, Citation2002; Luthans et al., Citation2006). Regarding the moderating hypotheisis, Psycap didn’t moderate the relationship between CQ and ITR (H4). The finding is supported by previous empirical positions from the works of (Avey et al., Citation2011; Setar et al., Citation2015; Tüzün et al., Citation2014. This may be related to the different emphases of Psycap and intention to remain. Concerning (H5), this assumption is not supported in this study based on the Psycap’s moderating effect on the relationship between CQ and OCB. Empirically studies have revealed as much (Avey et al., Citation2010; Luthans et al., Citation2005; Peterson et al., 2011; Youssef & Luthans, Citation2009). Thus, in this case, SIE academic’s Psycap didn’t go beyond enhanced in-role performance that could lead to “contextual” behaviors (discretionary behaviors) OCB. SIE academics couldn’t perform their job works beyond the standard working hours or attend meetings not mandatory. They are considered important as they didn’t consider those choices applicable to the organisation of the behavior. From this practical point of view, this result emphasises that psychological resources and CQ couldn’t activate the attitudes of the SIE academics workforce toward OCBs. Concerning the moderating result and in this respect, positive Psycap alters the strength of the causal relationship between CQ and WP (H6), and therefore provided support for hypothesis This finings is similar to that of (Darvishmotevali & Ali, Citation2020) validating the fact that employees with high positive psychology capital feel positive towards issues around them. Precisely, Psycap may pay more attention to work difficulties and help people deal with or overcome them. In comparison, the intention to remain may pay more attention to the positive sides of work. We consider this a fascinating finding and encourage future studies that examine the relationships between Psycap and intention to remain and the influence of Psycap intervention on this variable and some other work-related outcomes. The result also revealed that psycap moderated the relationship between CQ and work performance was supported.

Additionally, significant contributions to literature are being made in the current research. It shows the link between CQ and job outcomes variables for academic SIE expatriates (ITR, OCB, and WP). There are numerous empirical and theoretical studies supporting CQ and job outcomes in SIE literature (Afsar et al., Citation2020; Charoensukmongkol & Pandey, Citation2020; Haniefa & Riani, Citation2019; Nafei, Citation2012; Narayanan & Nirmala, Citation2000; Phenphimol et al., Citation2020; Ratasuk, Citation2020; Xu, Citation2017; Zhang et al., Citation2021). Indeed, over the last 20 years and more, the association between CQ and job results has been extensively studied. The connection has therefore attained some vitality. It raises favorable conditions and answers pertinent questions regarding why the CQ increases among SIE academic expatriates, reflected by their strong resolve and intention to remain at work. The significant result regarding the influence of Psycap on OCB shows that SIE academic expatriates have a significant effect on their lives, which generally leads to a higher degree of OCB determination in their work (Hackman & Oldman, Citation1976). First, the researchers discovered that CQ is related to the performance of SIE academics positively. The findings show a propensity for better understanding among SIE academic expatriates with higher CQ in a culturally different work environment. It also means that SIE academics with a higher CQ blend more culturally at work. This meant more opportunities for academics SIE to connect with the local people, eat food, understand various religious and social customs, enjoy different kinds of entertainment for as long as they were willing to adapt to a new culture on the job. This meant that this result corresponded to numerous preceding researches (Bhaskar-Shrinivas et al., Citation2005; Caligiuri, Citation1997; Selmer, Citation1999; Shaffera et al., Citation2001; Tompson & Tompson, Citation1993). Findings further revealed that CQ played a vital role in comprehending job outcomes in these studies.

Consequently, with higher CQ, people move to better results. Although theoretically, the social exchange between employers and workers becomes more positive (Blau, Citation1964) as CQ surges, employees tend to extend gratitude to the establishment where they work, which helps to increase their OCB and performance on the job (Morrison, Citation1994) and thus exhibit extra-role behaviors. Similarly, it contributes empirically to a theory that clarifies how the positive Psycap of employees influences how their CQ benefits the management of their institution. The results, which reveal a significant moderation result of psycap between CQ and WP, show that the followers’ positive Psycap has some importance in terms of work result. These types of employees tend to be very high in Psycap with resulting higher performance. The connection between these two variables (Avey et al., Citation2011) represents the principal advancement in this research. Therefore, people with higher PsyCap levels are expected to realise constructive and higher work performance in an organisation (Bitmiş & Ergeneli, Citation2013; Luthans et al., Citation2008).

7.1. Implication

From this perspective, this research contributes theoretically and practically and future research suggestions in the Psycap literature. In theory, this research is the first to study the influence of CQ in expatriate academics on the Psycap and work results (ITR, OCB, and OCB). It has validated the psycap theory by broadening its applicability (Luthans & Youssef, Citation2004) to the academic setting, largely ignored in the existing literature. PsyCap is a crucial antecedent of adaptive academic outcomes (autonomous motivation, academic achievement, and academic engagement), emphasising its significant’s findings. The research provided tentative evidence about the moderating effects of a PsyCap on job-specific outcomes, which is consistent with the proposed directions of Dawkins et al. (Citation2013) about the need to investigate particular psychological processes that may explain why Psycap catalyses positive outcomes. The study also shows that the results from the workplaces received considerable domestic research attention. Job outcomes (ITR, OCB, and OCB), in particular, is a significant outcome that is relevant in both local and international audiences due to its ever-increasing relevance to 21st-century educational quest. Another pertinent theoretical impact of this study is the predictive ability of CQ on Psycap. It is worth noting that lack of satisfaction with basic Psycap requirements weakens motivation and diminishes individual capability to conform to local and international exigencies (Deci et al., Citation2001; Montag et al., Citation2015). This research supports CQ’s harmonised work to impact expatriate academics’ psychological capacity through hope, optimism, self-efficacy, and stability. When you work and live overseas. Another major theoretical contribution to this study is the moderating role of Psycap. This is compatible with Malaysia’s domestic research findings Citation2013; Van den Broeck et al., Citation2008). Psycap is an important underlying mechanism to explain individual attitudes in an intercultural environment’s quest for better welfare. In addition to other researched variables such as cross-cultural adjustment, Psycap is absorbed as a dependable construct in the context of cross-cultural settings that can be considered as a mediator in upcoming studies. In practical terms, it is essential to note that CQ has the leverage to support expatriate academics Psycap abilities. Specifically, CQ shows greater variance than Psycap in job outcomes variables. Firstly, this investigation proposes that if higher institutions of learning want to improve the results of their expatriates, the institutions must demonstrate a greater comprehension of expected behaviours from among SIE academics. The performance assessments of expatriate academics should include OCB and WP. The development of CQ capacities could be seen as an effective intervention in support of OCB and WP. In addition, the evaluation of SIE academic’s CQ and Psycap potentials is put into perspective during pre-selection and recruitment of academic expatriates. The CQ feedback established by Ang, Van, Koh et al. (Citation2007) for self-assessment can be operationalised for this purpose. Third, schools, colleges, and similar institutions could support expatriates to meet their basic psychological requirements of perceived expertise, relationship, and independence. Higher learning institutions should consider introducing new faculty orientation programs into university communities and providing appropriate data, wherewithal and sustenance for coaching, investigations, publishing, and new entrants, including foreign faculty. Finally, before the job offers are accepted, potential candidates on their own should be able to carry out a job fitness mental assessment in order to adapt to the new environment.

7.2. Limitation

Naturally, there are certain limitations to this research. The first constraint is that respondents utilised the same source to collect data on both the predictor and criteria variables simultaneously (common rater effect) (same measurement time effect). Thus, our findings could be influenced by common rater bias because all of the data was collected in the same measuring setting (P. M. Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). As a result of this common source bias, associations may be overstated. As a result, we implemented a few procedural steps, such as using available scales and protecting anonymity, as Elci and Alpkan (Citation2009) advised to minimise the common rater impact.

Furthermore, the correlations between CQ, Psycap, ITR, WP, and OCB range from.33 to.47, implying a low common rater effect. To be honest, this approach can only help to reduce rather than eliminate this constraint. The common method bias (CMB) problem was tested using Harman’s one-factor test (P. M. Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). Although all items on the scale were included in the exploratory component analysis, the test result revealed that they were separated into multiple factors. A single factor did not cover the bulk of covariance between measurements. However, when the scale’s items are loaded on a single factor, the total variation explained is 17 per cent (test <.50). These findings suggest that the CMB does not significantly alter research findings. As a result, we recommend that future studies employ longitudinal study designs and collect data on research variables from various sources (e.g., colleagues and subordinates). As a result, it is now clearer how differences in cultural intelligence may affect job outcomes. The second constraint is the scope (only SIE academics in Malaysian public universities) and the content of our study (only CQ, Psycap, ITR, WP, and OCB). To get around this limitation, the sample might be expanded to include more sectors (e.g., telecommunication, tourism, military). Other attitudinal, cognitive, and behavioural characteristics such as emotional behaviour, organisational trust, or moderating or mediating variables such as work engagement, turnover intentions, or cultural shock should be investigated in future studies.

8. Conclusion

Even though the current cross-sectional study relied only on self-report measures, it was conducted on the relatively underinvestigated population of expatriates working within the Malaysian educational sector and specifically among public universities. It addressed some gaps in the literature by disentangling the complex relationship between CQ, Psycap ITR.WP and OCB. To this end, the research investigated the moderating mechanisms which explain how Psycap moderates the relationship between CQ and the job outcomes varibles. Findings indicated that CQ was positively related to all the three job outcomes constructs (ITR.WP and OCB). Psycap moderated the interaction between Psycap and WP, as expected. psycap, on the other hand, had no moderating effect on the link between CQ and ITR as well as between CQ and OCB. We conclude with the expectation that our theoretical contributions may drive additional cross-cultural research in the context of self-initiated academic expatriates, allowing public universities in Malaysia to get a better understanding of cross-cultural management.

Disclosure statement

We wish to categorically state and declare that all the authors contributed to the research in this article. According to Taylor & Francis policy and our ethical obligation, the researcher reports that we do not have any competing interests, whether financial or otherwise.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Abdulrasheed Abdullah Aminullah

Abdulrasheed Aminullah Abdullah is a lecturer in the Department of Cooperative Economics and Management at the Federal Polytechnic Mubi, Adamawa State of Nigeria. He obtained his M.Sc. in Management from University Utara Malaysia (UUM) in 2018. Presently, he is a Ph.D. candidate at the eminent Universiti Utara Malaysia majoring in human resources management. His focus of research is the effectiveness among academics. His major interests include business management, international business and HRM.

References

- Abdul Malek, M., & Budhwar, P. (2013). Cultural intelligence as a predictor of expatriate adjustment and performance in Malaysia. Journal of World Business, 48(2), 222–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2012.07.006

- Abogsesa, A. S., & Kaushik, G. (2018). Impact of training and development on employee performance. International Journal of Civic Engagement and Social Change, 4(3), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJCESC.2017070104

- Afsar, B., Al-Ghazali, B. M., Cheema, S., & Javed, F. (2020). Cultural intelligence and innovative work behavior: The role of work engagement and interpersonal trust. European Journal of Innovation Management, 12(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-01-2020-0008

- Al Bastaki, S., Haak-Saheem, W., & Darwish, T. K. (2021). Perceived training opportunities and knowledge sharing: The case of the United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Manpower, 42(1), 113–130. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-10-2019-0457

- Alessandri, G., Consiglio, C., Luthans, F., & Borgogni, L. (2018). Testing a dynamic model of the impact of psychological capital on work engagement and job performance. Career Development International, 23(1), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-11-2016-0210

- Amiri, A. N., Jandghi, G., Alvani, S. M., Hosnavi, R., & Ramezan, M. (2010). Increasing the intellectual capital in organization: Examining the role of organizational learning. European Journal of Social Sciences, 14(1), 98–108 .

- Amiri, A. N., Moghimi, S. M., & Kazemi, M. (2010). Studying the relationship between cultural intelligence and employees’ performance. European Journal of Scientific Research, 42(3), 432–441. ISSN 1450-216X.

- Ang, S., Van Dyne, L., Koh, C., Ng, K. Y., Templer, K. J., Tay, C., & Chandrasekar, N. A. (2007). Cultural intelligence: Its measurement and effects on cultural judgment and decision making, cultural adaptation and task performance. Management and Organization Review, 3(3), 335–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8784.2007.00082.x

- Ang, S., Van Dyne, L., & Koh, C. (2006). Personality correlates of the four-factor model of cultural intelligence. Group and Organization Management, 31(1), 100–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601105275267

- Arokiasamy, J. M., & Kim, S. (2020). When does emotional intelligence function better in enhancing expatriates’ cross-cultural adjustment? A study of Japanese PCNs in Malaysia. Journal of Global Mobility, 8(1), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGM-05-2019-0027

- Avey, J. B., Luthans, F., & Jensen, S. M. (2009). Psychological capital: A positive resource for combating employee stress and turnover. Human Resource Management, 48(5), 677–693. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20294

- Avey, J. B., Luthans, F., Smith, R. M., & Palmer, N. F. (2010). Impact of positive psychological capital on employee well-being over time. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016998

- Avey, J. B., Reichard, R. J., Luthans, F., & Mhatre, K. H. (2011). Meta-analysis of the impact of positive psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 22(2), 127–152. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.20070

- Bagozzi, R. P. (1992). The self regulation of attitudes intention and behaviour. Social Psychology Quarterly, 55(2), 178–204. https://doi.org/10.2307/2786945

- Becker, J. M., Klein, K., & Wetzels, M. (2012). Hierarchical latent variable models in PLS-SEM: guidelines for using reflective-formative type models. Long range planning, 45(5–6), 359–394.

- Bellamkonda, N., Santhanam, N., & Pattusamy, M. (2020). Goal clarity, trust in management and intention to stay: The mediating role of work engagement. South Asian Journal of Human Resources Management, 2(3), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/2322093720965322

- Bergheim, K., Nielsen, M. B., Mearns, K., & Eid, J. (2015). The relationship between psychological capital, job satisfaction, and safety perceptions in the maritime industry. Safety Science, 74(2), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2014.11.024

- Bhaskar-Shrinivas, P., Harrison, D. A., Shaffer, M. A., & Luk, D. M. (2005). Input-based and time-based models of international adjustment: Meta-analytic evidence and theoretical extensions. Academy of Management Journal, 48(2), 257–281. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.16928400

- Bitmiş, M. G., & Ergeneli, A. (2013). The role of psychological capital and trust in individual performance and job satisfaction relationship: A test of multiple mediation model. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 99(3), 173–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.483

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Justice in social exchange. Sociological Inquiry, 34(2), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1964.tb00583.x

- Bochner, S. (2003). Culture shock due to contact with unfamiliar cultures. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 8(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1073

- Boxall, P., Guthrie, J. P., & Paauwe, J. (2016). Progressing our understanding of the mediating variables linking HRM, employee well-being and organisational performance. Human Resource Management Journal, 26(2), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12104

- Bozionelos, N. (2020). Career barriers of Chinese self-expatriate women: neither double jeopardy nor ethnic prominence. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(January), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03024

- Brislin, R., Worthley, R., & Macnab, B. (2006). Cultural intelligence: Understanding behaviors that serve people’s goals. Group and Organization Management, 31(1), 40–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601105275262

- Brockner, J., Tyler, T. R., & Cooper-Schneider, R. (1992). The influence of prior commitment to an institution on reactions to perceived unfairness: The higher they are, the harder they fall. Administrative Science Quarterly, 37(2), 241. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393223

- Caligiuri, P. M. (1997). Assessing expatriate success: Beyond just “beingthere.”. New Approaches to Employee Management, 4(2), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.05.001

- Campbell, J. P., & Wiernik, B. M. (2015). The modeling and assessment of work performance. In Annual review of organanizational psychology and organanizational behaviour, 1 (2), 47–74. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032414-111427

- Campbell. (1990). Modeling the performance prediction problem in industrial and organizational psychology. Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1(2), 687–732.

- Chan, K. W., Yim, C. K., & Lam, S. S. K. (2010). Is customer participation in value creation a double-edged sword? evidence from professional financial services across cultures. Journal of Marketing, 74(3), 48–64. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.74.3.048

- Charoensukmongkol, P., & Pandey, A. (2020). The influence of cultural intelligence on sales self-efficacy and cross-cultural sales presentations: Does it matter for highly challenge-oriented salespeople? Management Research Review, 43(12), 1533–1556. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-02-2020-0060

- Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E. L., Van der Kaap-deeder, J., Duriez, B., Lens, W., Matos, L., Mouratidis, A., Ryan, R. M., Sheldon, K. M., Soenens, B., Van Petegem, S., & Verstuyf, J. (2015). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and Emotion, 39(2), 216–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-014-9450-1

- Chen, G., Kirkman, B., Kim, K., Farh, C., & Tangirala, S. (2010). When does cross-cultural motivation enhance expatriate effectiveness? A multilevel investigation of the moderating roles of subsidiary support and cultural distance. Academy of Management Journal, 53(5), 1110–1130. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.54533217