Abstract

This paper aims to develop a natural-disaster theme museum visitor satisfaction model by integrating authenticity, involvement, and destination image by applying Arnolds’ theory of emotion. This study takes place at Aceh Tsunami Museum, Indonesia. An Importance-Performance Map Analysis is applied to identify the performance and the importance of the museum attributes in determining visitor satisfaction. Using an adapted questionnaire, 199 usable data gathered from the Aceh Tsunami Museum were analyzed using Partial Least-Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM). The result showed that authenticity, involvement, and destination image as the predictors of visitor satisfaction with image as the highest predictor of visitor satisfaction. This study also found that image plays as a mediator in the relationship between authenticity, involvement and satisfaction. Subsequently, this study identifies two paths to reach visitor satisfaction in the natural-disaster theme museum. They are authenticity-image-satisfaction and involvement-image-satisfaction with the latter path have higher contribution to the visitor satisfaction. From IPMA analysis, it is found that activities that adding knowledge to the visitors are deemed important to create visitors satisfaction.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

A tsunami museum is a natural disaster theme museum established for education centers on natural disasters like tsunami and earthquake. It is also a remembrance place for the victims of the disaster. Unlike an art museum, in a natural disaster theme museum, the visitors are stimulated emotionally with horrific pictures or dioramas of a once beautiful city. The museum shows the impact of natural disasters on human life through pictures, and activities aimed to stimulate their curiosity about the disaster and increase their interest to learn more. However, this study found that the visitors give more value to activities that add knowledge about the natural disaster than on pictures. Through this kind of activity, they can tell whether the museum has given them an authentic experience of a life after natural disaster and becomes the basis of their satisfaction with their experience in visiting the museum.

1. Introduction

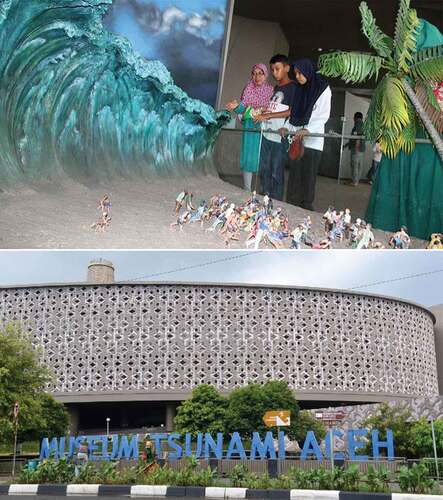

Under the umbrella of heritage tsunami and dark tourism, post-natural disaster tourism has recently become a tourism attraction (Buda, Citation2016). The tsunami museum is one of the tourism attractions built upon the natural disaster of the tsunami hitting countries such as Japan, Hawaii, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia. Although the museum’s primary goal is to be a place of remembrance and tsunami education center, it also plays an important role in supporting the country’s tourism industry. For example, the Aceh Tsunami Museum, which is in Aceh, Indonesia, has supported Aceh tourism branding as a tsunami tourism destination in Indonesia and has attracted millions of visitors since its establishment in 2009. This study is based on the Aceh Tsunami Museum, Indonesia, which is the first natural disaster theme museum built upon the tsunami disaster that hit Aceh, one of Indonesia’s provinces in December 2004.

As Aceh Tsunami Museum is marketed under a tsunami-disaster destination attraction, the core service of the museum is to deliver a tsunami tragedy experience to the visitors. The visitor journey to experience the tragedy is started as they enter the building where they will walk through a dark narrow corridor accompanied by water and rumbling sound. When they reach the exhibition room, they can learn about the city situation before the tsunami, during the tsunami and after the tsunami through the dioramas, remnants of the disaster, and pictures (Indonesia Travel, Citation2021). To further enhance the visitors experience, the museum also provides various activities related to the tsunami disaster such as tsunami education seminar (Museum Tsunami Aceh, Citation2021). However, there is no study that measure the performance of the museum in bringing a tsunami authentic experience to the visitors. According to Brida et al. (Citation2016) conducting a consumer survey is important in evaluating the value that an organization will offer to their customers to improve its service.

Satisfaction is a critical concept in marketing and tourism studies and holds an important role in an organization’s success. Some of the benefits of measuring satisfaction for organizations are understanding the organization’s performance and identifying attributes that could satisfy tourists (McDowall, Citation2010). Accordingly, a high level of satisfaction will lead to visitor loyalty, which later affects organization’s sustainability (Altunel & Erkut, Citation2015; Han & Hyun, Citation2018; J. H. Kim, Citation2018). This great benefit of satisfaction to the organization is why it is still a relevant factor to study. Likewise, in the formation of visitor satisfaction, the role of destination image cannot be ignored. Its impact on behavior, decision-making process, intention to visit, maintaining the market’s position, and competitiveness remains essential (Chiu et al., Citation2016; Lu et al., Citation2015; Slak Valek & Williams, Citation2018; Yilmaz & Yilmaz, Citation2020). Therefore, investigating the museum’s elements that affect the destination’s image and its role in affecting visitor satisfaction is imperative.

According to Antón, Camarero and Garrido (Citation2018) the sustainability of the museum relies heavily on providing a pleasing and rewarding experience to the visitor that influence the visitors’ intention to repeat the visit. As authenticity is the motivational factor of visitor to visit museum (Engeset & Elvekrok, Citation2015; Jiang et al., Citation2017; Loureiro, Citation2019) and determines the museum’s value (Thyne & Hede, Citation2016), museum experience must reflect the authenticity of the museum, in this context a tsunami authentic experience. Hume (Citation2015) stated that authentic experience can be generated from the objects displayed in the museum and visitor’s participation in the museum’s activity. As a result, the activities in the museum become an essential part in creating a museum experience and may influence visitors’ perceived authenticity (Zatori et al., Citation2018). Moreover, in this study, perceived authenticity is measured based on the constructive authenticity that defined authenticity as visitors’ interpretation on the object displayed (Wang, Citation1999). Involvement is used to measure visitors’ participation and responses to museum’s activity (Manfredo, Citation1989).

This study aims to investigate the effect of perceived authenticity and involvement on visitors’ satisfaction in the tsunami museum context. To understand how perceived authenticity and involvement affect visitors’ satisfaction, this study applies Arnold’s Theory of Emotion. According to S. N. Zhang et al. (Citation2019), the theory emphasizes the role of emotion in the process of evaluation that is stimulated by perceived situations. According to this theory, the process of the emotion formulation is stimulation-evaluation—emotion (S. N. Zhang et al. (Citation2019). This means in the tsunami museum, visitors are stimulated by the object displayed in the museum and the museum activity, then they will evaluate whether the object and activity reflect an authentic-tsunami disaster experience and museum’s image as a tsunami museum. Finally, they will conclude whether their experience is satisfactory or not.

This study also investigates the role of image in mediating the relationship between the predictors and satisfaction. This study acknowledges the importance of attributes identification in improving visitor satisfaction as the reference for museum management to enhance their value creation process. In doing so, this study applies an Importance Performance Map Analysis (IPMA) to identify museum attributes that are performing well, underperforming, valuable, and invaluable in the creation of visitor satisfaction. According to Matzler et al. (Citation2004), IPMA outcomes contribute to the decision-making process on improvement priority attributes and putting investment in the right features that ensure visitor satisfaction.

The novelty of this study is analyzing the role of perceive authenticity as the antecedent in museum visiting experience and image as the mediator that have received little attention from scholars. As stated by Komarac et al. (Citation2020), works on the perceived authenticity in a museum is still limited and not fully understood. According to Lu et al. (Citation2015) the role of destination image as a mediator is still underexplored. Referring to prior studies (e.g Gao et al., Citation2020; Kim et al., Citation2020; Komarac et al., Citation2020; E. Park et al., Citation2019; S. Y. Park et al., Citation2018) authenticity and involvement have limited studies incorporating destination image as the mediator variable, especially in the relationship between authenticity and involvement with visitor satisfaction. Hence, this study contributes to enriching the understanding of authenticity and involvement in the museum context with destination image as a mediator. It also contributes to identifying the museum attributes that need improvement and narrowing the gap in the destination image study.

Accordingly, this paper proceeds with an introduction. It then continues with a brief literature review and hypotheses development related to involvement, perceived authenticity, destination image, and customer satisfaction based on the review of the current evidence of these relationships. Next, the paper describes the methodology used, followed by results of the analysis using Partial Least Square-Structural Equation Modelling IPMA. Finally, it discusses the results and highlights the implications of the study.

2. Literature review

2.1. Arnold’s theory of emotion

Theory of emotion is developed by Magda B. Arnold who was the first to propose that emotion is the outcome of evaluation process (Reisenzein, Citation2006). According to Arnold (Citation1960) perception leads to emotion and action. Arnold elaborated that to generate emotion, it is enough to know a basic knowledge about an object. It means that evaluating an object is authentic or not does not require a deep knowledge on what constitute an authentic object. However, it requires a factual belief of individuals that the object is authentic (Reisenzein, Citation2006). Accordingly, the theory described four stages of emotion process, namely (1) the presence of a belief of a state of affairs (2) evaluation (3) action (4) emotion. Following the Arnold’s theory of emotion, this study proposed the process of emotion/satisfaction generated in the museum context. First, the object displayed in the museum and the activities held in the museum act as a stimulant of visitors’ belief, second, the visitors will conduct an evaluation related to the object and activities followed by their action to approach (e.g. seeking for more information related to the object, involved in the activities) or avoid (e.g. losing interest to explore the museum). Finally, visitors develop a positive emotion (i.e. satisfaction) based on their level of importance of the visiting.

2.2. Visitor satisfaction

Generally, visitor satisfaction is defined as a positive result from favorable evaluations of consumption (Prayag et al., Citation2017). However, according to Domínguez-Quintero et al. (Citation2018) and Saayman et al. (Citation2018), visitor satisfaction has many definitions and measurements that have not yet been accepted unanimously. There are three common approaches used by many studies to conceptualize visitor satisfaction. They are cognitive, affective, and cognitive-affective. The cognitive approach conceptualized satisfaction as an appraisal of post-consumption in which satisfaction evoked when the post-consumption performance in the minimum meets or exceeds the expectations before consumption (Eusebio & Vieira, Citation2013; Yusra & Agus, Citation2020). However, this approach is criticized for using expectancy as the benchmark for evaluating satisfaction and dissatisfaction.

In contrast, the affective or emotional approach uses tourists’ emotions to determine satisfaction or dissatisfaction. As defined by Han and Hyun (Citation2015) and Huang et al. (Citation2015), tourist satisfaction is an emotional reaction that originated from the experience consumption of tourism products and services. This approach formulates satisfaction by comparing the feeling of before- and post-consumption (Oliver, Citation1980).

The novel approach to satisfaction combines the two previous techniques dubbed as a cognitive-affective approach. This approach stated that cognitive evaluation and emotions from consumption experience influence satisfaction (Del Bosque & San Martín, Citation2008). Further, they described that some scholars argued that it is insufficient to use only the cognitive approach in measuring satisfaction since emotions are important components of the destination experience. Therefore, this study applied the cognitive-affective approach to measuring satisfaction and defined visitor satisfaction as visitors’ positive outcome based on cognitive evaluation and emotion after experiencing a destination.

2.3. Destination image

Destination image is generally defined as the totality of the belief, ideas, and impressions a visitor hold about a destination (Crompton, Citation1979). H. Zhang et al. (Citation2014) elaborated the definition by explaining that those beliefs, ideas, and impressions derived from the processing of information of different sources exposed by a visitor generate “a mental representation of the attributes, benefits, and distinct influence sought of a destination.” The definition emphasizes the importance of information sources forming the destination image.

Based on the information sources, Phelps (Citation1986) identified two sources of image, primary and secondary image. Primary image is an image created from traveling to a destination, while secondary image is an image created before traveling to a destination. Further, Gartner (Citation1994) described that the sources of the secondary image are advertising, news, TV program and family as well as friend. Among these information sources, Kim (Citation2018) argued that the primary impression is the most important information source of image formation.

Regarding the measurement of destination image, most literature measures destination image formation based on three main components; cognitive, affective, and conative (H. Kim & Chen, Citation2016). Cognitive referred to “visitors’ perception towards destination attributes” (Gartner, Citation1994; Kim & Chen, Citation2016; Pike & Ryan, Citation2004; H. Zhang et al., Citation2014) such as service quality, attraction, environment, and infrastructure (Beerli & Martín, Citation2004). An affective component is defined as “visitors’ feeling or emotional response about a destination attributes” (H. Zhang et al., Citation2014); that is measured by the feeling of pleasure, displeasure, or neutral (Kim & Chen, Citation2016). While conative is “tourists’ behavioral intention” on visiting a destination stimulated from cognitive and affective image (Gartner, Citation1994; H. Kim & Chen, Citation2016). Among the three components, cognitive is considered an easier component to measure because it can be observed directly and provide more comprehensive and interpretive information about a destination’s distinctive element (Chen & Phou, Citation2013). Hence, this study focuses on measuring the post-visit destination image using the cognitive components. According to Fakeye and Crompton (Citation1991), the destination image derived from an actual visit has a higher accuracy of destination knowledge than secondary sources.

Aside from visitor satisfaction, the destination image is another important component in tourist destination success. Most studies show that the destination image determined the level of satisfaction. For example, Lu et al. (Citation2015), who studied the effect of destination image on satisfaction in heritage tourism, found that destination image positively impacts satisfaction. A similar result was also found in the wellness (yoga) tourism context conducted by Sharma and Nayak (Citation2018). Using a cognitive component as destination image measurement, the finding of Kim (Citation2018) is consistent with the finding of Lu et al. (Citation2015). Other studies from Chiu et al. (Citation2016) found that both cognitive and affective images directly link to tourist satisfaction. They all asserted that a destination with a positive image in the visitor’s mind results in a high level of satisfaction. In other words, when Tsunami museum visitors have a positive impression of the museum as part of a tsunami tourism destination, they will be satisfied with their overall experience in visiting the museum. Therefore, this study proposed the following hypothesis:

H1: Destination image has a positive influence on visitor satisfaction

2.4. Authenticity and image

The study of authenticity originated in the study of the museum (Trilling, Citation1972) but has extended to marketing (Brida et al., Citation2014; Gilmore & Pine, Citation2007) and sociology (Gilmore & Pine, Citation2007). According to Rickly-Boyd (Citation2012), authenticity is associated with “tourism objects, tourism sites, tourist attractions, and tourist experiences”. Museum is a place of tourist attraction, therefore, authenticity is an important attribute that may influence tourists’ choice of a tourism destination.

Scholars have defined authenticity in different ways (Domínguez-Quintero et al., Citation2018). For example, Cohen and Cohen (Citation2012) described authentication as a process of evaluating a product, site, object, or event intended to confirm it as “original”, “genuine”, “real”, or “trustworthy”. Other scholars such as Chhabra (Citation2005) and Frisvoll (Citation2013) defined authenticity as the quality of being “authentic” and “real” or “real and genuine”. Hence, this study defined museum authenticity as a process of evaluating the quality of object and event in a museum as original, genuine, real, or trustworthy.

Studies have shown that authenticity is an important component for a museum functioning in motivating visitors to visit a destination (Engeset & Elvekrok, Citation2015; Jiang et al., Citation2017; Lee et al., Citation2016; Loureiro, Citation2019; Lu et al., Citation2015; Nguyen & Cheung, Citation2016). Yilmaz and Yilmaz (Citation2020) indicated that motivation to visit a destination is an influential element in the process of image formation for a non-visitor. However, when they visit the destination, the image is formed based on the evaluation of the destination quality reflected through the destination’s authenticity (i.e., object, events, or building). The authors further describe that the quality of visitor experience is one of the antecedents of the post-trip destination image. Thus, it infers that authenticity is the primary information source for creating a destination image after visiting a destination. Subsequently, when visitors’ experience during the visit meets their expectations before the visit, a strong destination image is resulted (Yilmaz & Yilmaz, Citation2020). A previous study by Lu et al. (Citation2015) found that authenticity positively influences destination image, indicating the important role of destination authenticity in the destination image formation. Kim et al. (Citation2020), who investigated the antecedents of restaurant image, found that perceived authenticity positively influences restaurant image. Hence, this study proposes the following hypothesis

H2: Authenticity has a positive effect on the destination image of a museum

2.5. Authenticity and satisfaction

According to Lee et al. (Citation2016), authenticity can be conceptualized using three approaches: objective, constructive, and existential authenticity. However, Kolar and Zabkar (Citation2010) grouped objective and constructive authenticity under one umbrella: object-based authenticity. Objective authenticity can be seen through the expert certified objects displayed in the museum (Leigh et al., Citation2006; MacCannell, Citation2017; Wang, Citation1999). Accordingly, the visitors perceive the authenticity based on the objects displayed in the museum. Contrary to objective authenticity, constructive authenticity is based on the result of visitors’ self-interpretation process (Wang, Citation1999). Thus, the meaning of authenticity lies in the individual interpretation after observing an object. It also indicates that one individual may perceive it as authentic, while others may see it differently (Lee et al., Citation2016). Finally, existential authenticity, or experience-oriented authenticity, describes authenticity as the result of touristic activity participation that builds an intimate connection between visitors and destinations (Steiner & Reisinger, Citation2006; Wang, Citation1999).

In line with the above argument, perceived authenticity is an important component in the formation of visitors’ satisfaction. The latest studies in tourism found that perceived authenticity is one of the components that can influence tourists/visitors’ satisfaction. For example, S. Y. Park et al. (Citation2018) investigated the determinants of visitors’ positive behavior towards Jidong Mural alley in South Korea indicated that when a visitor has a high level of authenticity, she or he has a high probability of feeling satisfied with the experience of visiting the destination. Later, Domínguez-Quintero et al. (Citation2018) stipulated that visitors who perceive a destination’s authenticity positively developed a feeling of satisfaction with the destination. Similarly, in AirBnB (Lalicic & Weismayer, Citation2017) and heritage destination (Nguyen & Cheung, Citation2016), authenticity was a significant performance indicator for tourist satisfaction. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: Authenticity has a positive influence on visitor satisfaction

2.6. Involvement and image

In consumer behavior, involvement is a significant component in understanding how the consumer behaves to activity and makes a decision (Altunel & Erkut, Citation2015; Lu et al., Citation2015). Consequently, other studies such as tourism, leisure, and recreation have applied it to understand the level of tourists’ involvement towards a destination (Han & Hyun, Citation2017, Citation2018). These studies described involvement differently. Specifically, the scholars have not yet met an agreement on the description of the term (Zatori et al., Citation2018), and thus the definition is contextual (Altunel & Erkut, Citation2015). In tourism research, involvement is defined as the degree of the tourists’ interest to involve in an activity and their affective response to the activity (Manfredo, Citation1989). According to Campos et al. (Citation2017), involvement is considered a significant component of the tourism experience and affects its product, activity/experience, and destinations. Some scholars argued that involvement is personal and should be measured in real-time or on the site (Beaton et al., Citation2009; Zatori et al., Citation2018). Therefore, this study defines involvement as visitors’/tourists’ perceptions of the experience/activity they participate in during their visit to the destination.

According to Altunel and Erkut (Citation2015), there are a variety of involvement measurements. In the tourism setting, involvement can be measured, for instance, using the scale developed by Kyle and Chick (Citation2004) as well as Gursoy and Gavcar (Citation2003). Kyle and Chick (Citation2004) identify four dimensions in leisure involvement: centrality, social bond, identity affirmation, and self-expression. In comparison, Gursoy and Gavcar (Citation2003) measured tourists’ involvement based on their pleasure/interest and the risk associated with the activity or experience (i.e., risk probability and importance). Furthermore, Zatori et al. (Citation2018) introduced the experience-involvement measurement based on emotional, mental, flow-like, and social. However, some studies also measure involvement using one-dimensional rather than multi-dimensional construct (Gao et al., Citation2020).

Yilmaz and Yilmaz (Citation2020) stated that involvement is part of the post-visit personal antecedent of the destination image, which is based on tourists’ experience with the destination. Further, they argued that this type of antecedent has the primary role in creating a favorable destination image. Previous studies have shown supportive shreds of evidence on a positive relationship between involvement and destination image. For example, Lu et al. (Citation2015) surveyed the role of involvement in forming heritage tourism’s destination image and found that involvement influences destination image positively. Similarly, in the study of Couchsurfing involvement, Kuhzady et al. (Citation2020) found that it positively affects the destination image. Therefore, this study argues that favorable tourists’ involvement perception of their experience/activity in the museum will result in a sympathetic destination image. The following hypothesis is proposed:

H4: Involvement has a positive influence on destination image

2.7. Involvement and satisfaction

According to Antón, Camarero and Garrido (Citation2018), the museum experience should be a rewarding and pleasing one characterized by symbolic meaning, hedonic pleasure, and subconscious responses. Further, they asserted that the museum might offer experience ranging from the four experience categories developed by Pine and Gilmore (Citation1998), such as entertainment, education, escapism, and aesthetic. It infers that enjoyment and education are important aspects of the museum experience/activity. As a result, visitors will use those aspects to determine their satisfaction with the overall museum experience after their involvement in the museum activity. As noted by Han and Hyun (Citation2018), when visitors have high involvement in an activity, they would have a high probability of being satisfied with their experience visiting the museum. The relationship between involvement and satisfaction has been established in previous studies such as Lu et al. (Citation2015), Gao et al. (Citation2020), Altunel and Erkut (Citation2015), and Forgas-coll et al. (Citation2017). Given the importance of involvement in the creation of museum experience, thus, we hypothesize:

H5: Involvement has a positive effect on visitors’ satisfaction

2.8. Involvement and authenticity

Authenticity is an important element in evaluating destination experience quality (Domínguez-Quintero et al., Citation2018; Lee et al., Citation2016), affecting the perceived value of the destination (Kolar & Zabkar, Citation2010; Lee et al., Citation2016). As noted before, authenticity can be achieved through objects displayed in the museum and activity. According to Wang (Citation1999) and Steiner and Reisinger (Citation2006), participation in activities creates existential authenticity. Thus, it is considered as an experienced-oriented element (Zatori et al. (Citation2018). Since this study treated involvement as an experiential component, the relationship between involvement and authenticity can be explained through the concept of existential authenticity.

In this regard, evidence suggests that visitors can achieve an authentic experience through actively participate in museum activity (Hede et al., Citation2014). Later, Zatori et al. (Citation2018) postulated that authenticity is one of the consequence variables of involvement. Specifically, their study on a sightseeing tour found that interaction with the tour guide, local people, and other visitors contributes to an authentic experience. Hence, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H6: Involvement has a positive influence on authenticity

2.9. Destination image as a mediator variable

Although destination image is a prominent construct in tourism study, a mediator role of destination image in tourism study model is under review (Lu et al., Citation2015; Pereira et al., Citation2019). According to Pereira et al. (Citation2019), a positive attitude toward a destination is derived from tourists’ motivation to visit a destination and the perceived image resulted from the visit. Also, Gannon et al. (Citation2017) exerted that destination image guides the visitor’s behavior before, during, and after travel.

A previous study in heritage tourism study shows that destination image plays a mediating role in the relationship between authenticity and involvement towards satisfaction (Lu et al., Citation2015). In other words, a favorable impression resulted from the positive perception of two antecedents (i.e., authenticity and involvement) on experience in the destination leads to visitors’ satisfaction. Hence, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H7: Destination image mediates the relationship between authenticity and satisfaction

H8: Destination image mediates the relationship between involvement and satisfaction

3. Method

3.1. Sample and data collection

Data were obtained from a convenience sample of Aceh Tsunami Museum visitors. The sample size determination follows Hair et al.’s (Citation2019) suggestion, which is multiplying the number of indicators with a number ranging from 5 to 10. Since this study has 19 indicators, thus the study must collect at least 95 respondents. Moreover, the study has succeeded in collecting 199 respondents that are deemed sufficient for data analysis using the technique of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM).

Self-administered questionnaires were distributed to the museum’s visitors as soon as they complete their visit. The questionnaire is divided into 2 (two) parts; part 1 focuses on asking the respondent’s personal information and visiting frequency to the museum. Part 2 focuses on variable measurement using a Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Perceived authenticity was measured using five items adapted from previous studies, such as Lu et al. (Citation2015) and Ram et al. (Citation2016). Involvement measurement was measured using five items adapted from the Zatori et al. (Citation2018). Satisfaction measurement has four items adapted from Gursoy and Gavcar (Citation2003). Destination Image was measured using five items adapted from Beerli and Martín (Citation2004) as well as Fotiadis and Vassiliadis (Citation2016). In total, this study has 19 items to measure the study variables.

3.2. Data analysis

Partial least squares structural equation modeling, or PLS-SEM, were used in this study to analyze the proposed model. Results were generated using the SmartPLS 3.0 to answer the stipulated hypotheses and develop the importance-performance map. By using the map, the museum authority can identify which aspects they should focus on to improve visitor satisfaction.

4. Result

4.1. Respondent characteristics

The demographic of museum visitors who participated in this study is depicted in . Among 199 respondents, more than half of them are female visitors, with 64.8%, while the rest are male (35.2%). The age of respondents is dominated from 15 to 31 years old respondents (65. 9%), while respondents with an age range from 26 to more than 43 years old are 34.1%. This result is aligned with the respondents’ occupation, where respondents who are college students and employed taking 70.9% of the total occupation group. Most of the respondents are from Indonesia (75.9%), while only 13.6% are from Malaysia. The respondents’ country of origin is in line with the Aceh Museum Tsunami visitors’ profile. According to museum management (Dwinanda, Citation2019), most visitors come from Aceh, Indonesia, while foreign visitors mostly come from Malaysia, Japan, China, and France. Moreover, most of the respondents have visited the museum more than once (50.9%).

Table 1. Demographic profile

4.2. Measurement model

The constructs in the model were measured reflectively. Following Hair et al., (Citation2019), four criteria were used to evaluate the reflective measurement model: indicator loading and reliability, internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Results for the first three assessment criteria are shown in , and results for discriminant validity are shown in .

Table 2. Reflective measurement model assessment

As shown in , all indicator loadings, except INV3, INV5, AUT4, AUT5, and IMG4, were above the threshold value of 0.708. This result, thus, indicates good reliability among the indicators of the reflective measurement model. As measured by Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability, internal consistency shows that all values were above 0.70. It indicates that the reflective measurement model has good internal consistency reliability. Based on this result, all indicators with lower loadings than the threshold value were retained because its elimination would not increase the composite reliability values above 0.50 (Hair et al., Citation2019). Assessment of the average variance extracted indicates that all latent variables have good convergent validity exceeding 0.50. It means that the latent variables explain more than 50% of the variance of its indicators.

As shown in , discriminant validity results indicate that there was no issue with this validity. As shown in , the HTMT values were all below 0.90, and the confidence interval values did not contain the value one; hence, supporting the presence of discriminant validity.

Table 3. Heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT)

Following a reliable and valid measurement model, the structural model was assessed as shown in . Hair et al., (Citation2019) identify four criteria to be assessed on a structural model. First is the coefficient of determination, R2. The R2 values range from 0.405 (destination image) to 0.645 (visitor satisfaction). Although the model’s explanatory power is moderate, it is still above 0.10, the recommended value (Altunel & Erkut, Citation2015; Falk & Miller, Citation1992). The second is the effect size, which measures a predictor’s impact on an endogenous latent variable (Hair et al., Citation2017). Involvement has the largest effect size on perceived authenticity (f2 = 0.761), followed by destination image on visitor satisfaction (f2 = 0.227) and involvement on destination image (f2 = 0.169). The smallest size was found for the effect of perceived authenticity on destination image (f2 = 0.072). It implies that the predictors’ effect sizes on the endogenous latent variables in this model range from medium to large. Third, the model’s predictive accuracy was assessed. The blindfolding procedure and PLS predict procedure was used to generate the Q2 values. shows that both Q2 values were above zero; hence, indicating that the model’s predictive accuracy was established. Although Hair et al., (Citation2019) recommended assessing the model’s predictive power, the purpose of this study did not call for such an assessment.

Table 4. Coefficient of determination, cross-validated redundancy, PLS predict and effect size of the structural model

The last assessment criteria for a structural model are the statistical significance and relevance of the path coefficients, which answer the proposed hypotheses. As collinearity may bias the results, the variance inflation factor (VIF) values were first checked. The VIF values range from 1.000 (involvement → perceived authenticity) to 2.059 (involvement → visitor satisfaction); hence, indicating there was no issue on collinearity.

shows the path coefficients and their statistical significance on the hypothesized relationships. All direct relationships were significant. Of the six direct relationship hypotheses, the largest coefficient was between involvement and perceived authenticity (β = 0.657, p < 0.000). The smallest coefficient was between perceived authenticity and destination image (β = 0.275, p < 0.01). The two indirect relationships were also significant. Therefore, all hypotheses were supported. shows the model’s path coefficients and their significance.

Table 5. Path coefficients and significance

4.3. Importance Performance Map Analysis (IPMA)

An advantage of analyzing data using PLS-SEM is its latent variable scores can be used for further analysis. Through using the latent variable scores, an importance-performance map was created, as shown in . A cross-hair line was drawn to split into four quadrants for an easier interpretation of the indicator’s performance relative to its importance (Hsu, Citation2008; Martilla & James, Citation1977; Rosenbusch et al., Citation2018). The quadrant is divided according to the indicators’ importance and performance, namely education, keep up, no change, and do better.

The first quadrant is education. The indicators in this quadrant have high performance but lower importance in determining visitor satisfaction. It consists of historical tsunami stimulant of emotion (AUT 5), well presentation of tsunami historical (AUT 3), interesting and authentic impression (AUT 6), scenery and natural attraction (IMG 5), cultural presentation (AUT 4), and historical objects preservation (AUT 1). Second, keep up quadrant indicates the indicators that the museum has executed well and has a high impact on visitor satisfaction. In this quadrant, there is one indicator only, namely a knowledge-added activity (INV 3). While the third quadrant, no change shows museum indicators that have low importance and low performance. Therefore, the museum management can ignore these indicators in developing a marketing strategy. The indicators are Acehnese cultural representation (IMG 3) and cultural attraction (IMG 2), entertainment facility (IMG 4), authentic picture of life before tsunami (AUT 2), and service quality (IMG 1). Finally, the last quadrant, do better, is the quadrant that needs special attention due to its low performance but high importance. It includes inspirational activity (INV4), attractive activity (INV 2), fun activity (INV1), and escapism activity (INV 5).

Moreover, the indicator with the highest mean performance is AUT 5 (83.08), and the lowest mean performance is INV 5 (71.8). While for the mean importance, the highest mean is INV 1 (0.17), and the lowest mean is AUT 2 (0.06).

5. Discussion and conclusion

This study aims to build a natural-disaster theme museum visitor satisfaction model by examining the influence of authenticity and involvement on visitor satisfaction and destination image. It also aims to investigate the role of image in mediation of the relationship between predictors (e.i authenticity and involvement) and satisfaction as well as to investigate the performance and importance of tsunami museum attributes that determine visitor satisfaction.

The first finding of this study highlighted the importance of creating a favorable image to visitors’ satisfaction. This study found a direct relationship between destination image and visitors’ satisfaction, which is in line with the previous studies, such as Lu et al. (Citation2015) in heritage tourism and Sharma and Nayak (Citation2018) in wellness tourism. The finding shows that the study setting (e.g., museum and yoga tourism) and measurement (e.g., cognitive and affective) do not influence the relationship between destination image and satisfaction. The relationship is also unaffected when the image is measured after the visitor visiting the destination.

The rest of this study’s finding focuses on the variable that affects destination image and visitors’ satisfaction. The result shows that the positive authenticity perception of visitors to the museum leads to satisfaction. Previous studies such as S. Y. Park et al. (Citation2018), Domínguez-Quintero et al. (Citation2018), and Lalicic and Weismayer () supported the finding and confirming the significant role of authenticity on visitor satisfaction. Thus, this study’s finding shows that visitors use authenticity to evaluate their experience in visiting the museum by comparing their expectations and feelings before and after consumption. Another finding of this study indicated that a positive perception of authenticity leads to a favorable destination image. This finding is consistent with a previous study by Lu et al. (Citation2015), where they found the connection between authenticity and image in heritage tourism. This notion supported the argument that visitors view authenticity as the reflection of destination quality that later becomes their primary image source in formulating destination image.

Further, it was found that involvement significantly affecting visitor satisfaction and destination image. This finding is consistent with previous studies on involvement. For example, in a study about the reuse of urban heritage sites, Gao et al. (Citation2020) found involvement as the strongest predictor of visitor satisfaction. Another study by Forgas-coll et al. (Citation2017) also found that involvement leads to visitor satisfaction in the art-related museum. The study of Lu et al. (Citation2015) and Kuhzady et al. (Citation2020) found the relationship between involvement and destination image. This finding indicated that visitors who perceive the museum’s activity positively would feel satisfied with their museum experience and have a favorable museum image.

Other than affecting visitor satisfaction and museum image, this study identified involvement as the predictor of perceived authenticity. The result showed that visitors’ involvement in museum activity is a significant factor in creating visitors’ perception of the museum’s authenticity. This finding is consistent with the study of Zatori et al. (Citation2018) in the sightseeing tour context. The results also showed that authenticity is reflected in the objects displayed in the museum and the museum’s events that visitors participated in. Hence, the findings highlight the importance of activity in creating visitor satisfaction, favorable authenticity perception, and destination image.

The final finding of this study shows a pathway of authenticity and involvement in creating visitors’ satisfaction. It found that by creating a positive perception of those antecedents, the museum can form a favorable image and later form visitor satisfaction. This finding is consistent with the conclusion of Lu et al. (Citation2015), who found that the destination image has a mediation effect on the relationship between those two variables with visitors’ satisfaction. The study implies that museums can influence the perceived authenticity and involvement of the visitors by improving the image of a destination, which later leads to visitor satisfaction. The museum may jointly increase the destination image with the related parties such as government, media, and visitors to improve the persona of the museum.

The results of Importance Performance Map Analysis (IPMA) guide museum management in improving the museum attributes that lead to a higher level of visitor satisfaction. The finding shows that the museum has demonstrated outstanding performance in providing authentic experience through objects and cultural presentation. The museum has also successfully stimulated the visitors’ emotions and left a favorable impression on the visitors. However, the visitors perceive these constructs as unimportant for the creation of satisfaction in visiting the museum. Instead, they view the museum as a remarkable performance in offering educative activity and putting this attribute as necessary in determining their satisfaction with the museum. This finding is in line with the literature that describes the visitor as an active observer who demands a more engaging experience in the museum (Hume, Citation2015; Komarac et al., Citation2020). Therefore, it is suggested that the museum management needs to put an effort in maintaining the performance of this attribute because its underperformance will have a negative impact on visitors’ satisfaction.

The finding also identified four museum attributes related to the involvement construct that require more attention from the museum management due to low performance but high importance in determining visitor satisfaction. The attributes reflected that the visitors perceived the museum activity as uninspiring, unattractive, boring, and lacking escapism. One of the tsunami museum’s purposes is to educate the visitor about the tsunami and the disaster that hit the region. However, educative activity should be packaged attractively. For example, the disaster story should be told breathtakingly, offering a simulation of tsunami evacuation to educate the visitors about tsunami evacuation and making a short drama to show the impact of the disaster on the victims’ lives in pictures or an exhibition. The museum could also design a museum game to educate the visitor about the tsunami where the visitors look for the answer while visiting the museum. The museum will then reward the visitors with a museum souvenir for every correct answer.

Moreover, regarding the magnitude of the predictor influences on visitors satisfaction, the findings show that amongst the determinants of visitors satisfaction (e.i image, authenticity and involvement), image has a greater influence than the other predictors. It has 36,8% influence to visitor satisfaction, while involvement and authenticity have 29% and 27.9%, respectively. Between authenticity and involvement in the influence of image creation, this study found that involvement has higher effect on image creation (42%) than authenticity (27.5%). Subsequently, image as the mediator has greater role in mediating the relationship between involvement and satisfaction (15%) than in the relationship between authenticity and satisfaction (10%).

6. Implication

This study has identified a natural-disaster theme attributes that have an influence on visitors satisfaction, namely image, involvement and authenticity. The museum image is found to be a dominant attribute in creating visitors satisfaction. Therefore, the museum management should focus on improving the image of the museum as a tsunami museum when develop museum marketing strategies. It can be conducted by using advertising as a pre-visit information to create a destination image before visitation. Then, during the visitation, the management should focus more on creating activity that is highly related to tsunami such as tsunami education seminar, tsunami simulation and a pictorial drama of life after the tsunami. Although tsunami-related object displayed such as photography, diorama, miniature of the tsunami when hitting the city is found to have little significant in visitors satisfaction, it acts as a supporting role in enhancing the museum image as a tsunami museum. Therefore, it is advised to increase the number of the tsunami-related object display.

This study also has identified two paths to reach visitors satisfaction, namely involvement-image-satisfaction and authenticity-image-satisfaction. However, this study recommended the path of involvement-image-satisfaction for the museum since it has a greater contribution than the authenticity path. In addition, this identification show that image have a mediating role in the process of satisfaction creation. It also identified from Importance Performance Analysis (IPMA) result that a knowledge-added activity is the kind of activity perceived by the visitors as highly important to their satisfaction. Therefore, the museum management should increase the numbers of activity that add knowledge.

7. Limitation and future study

This study is not without limitation. Since the study was conducted in Aceh, the data were collected from Tsunami Museum visitors in Aceh, Indonesia. Thus, the results may not be generalized to other Tsunami museums such as Sri Lanka, Hawaii, and Japan. Future investigation should reach larger samples from those destinations. As a result, they will represent and generalize the visitors’ perception regarding dark tourism even more accurately. Secondly, we disregard the variety of respondents’ backgrounds, such as the country of origin and age group. Respectively, it is likely that the perception of authenticity and involvement toward visitor satisfaction could be varied. Thus, it would be noteworthy to compare individuals’ perception between, for example, local people (e.g., Indonesian) versus foreigners, and millennials versus non-millennials.

Thirdly, maintaining the museum’s originality, genuineness, realness, and trustworthiness will be challenging. Even with technological advancement, the effort required to preserve the tsunami artifacts and high operational costs will threaten the tsunami museum’s originality. Considerably, an investigation on how visitors perceive authenticity (e.g., product and brand authenticity) is a fruitful area for future research. Furthermore, our research attends to the significance of visitor satisfaction in a tourist destination. To sustain in the tourism market, visitor revisits behavior is a notable element in tourism marketing investigation (Wu et al., Citation2015). Therefore, future studies should examine the range of how and why satisfied visitors revisit and say positive words about the destination and museum.

Appendix Measurement Items

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).3

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Cut Aprilia

Cut Aprilia is a lecturer at the Management Department, Economics and Business Faculty, Universitas Syiah Kuala. She has published four research papers in the area of tourism and marketing. However, this is her first paper on museum and the start of her interest to study about this cultural organization. As a part of tourism attraction, museum study in the context of natural disaster theme museum receives little attention from the scholars, while it has an important role in educating people about natural disaster. This research paper is a call for further investigation on how to improve visitors experience in a natural disaster theme museum.

References

- Altunel, M. C., & Erkut, B. (2015). Cultural tourism in Istanbul: The mediation effect of tourist experience and satisfaction on the relationship between involvement and recommendation intention. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 4(4), 213–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.06.003

- Antón, C., Camarero, C., & Garrido, M. J. (2018). Exploring the experience value of museum visitors as a co-creation process. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(12), 1406–1425. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1373753

- Arnold, M. B. (1960). Emotion and personality. American Journal of Psychology, 76(3), 4662–4671.

- Beaton, A. A., Funk, D. C., & Alexandras, K. (2009). Operationalizing a theory of participation in physically active leisure. Journal of Leisure Research, 41(2), 177–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2009.11950165

- Beerli, A., & Martín, J. D. (2004). Factors influencing destination image. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3), 657–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.01.010

- Brida, J. G., Disegna, M., & Scuderi, R. (2014). The visitors’ perception of authenticity at the museums: Archaeology versus modern art. Current Issues in Tourism, 17(6), 518–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2012.742042

- Brida, J. G., Meleddu, M., & Pulina, M. (2016). Understanding museum visitors’ experience: A comparative study. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, 6(1), 47–71. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-07-2015-0025

- Buda, D. M. (2016). Tourism in Conflict Areas: Complex Entanglements in Jordan. Journal of Travel Research, 55(7), 835–846. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287515601253

- Campos, A. C., Mendes, J., Do Valle, P. O., & Scott, N. (2017). Co-creating animal-based tourist experiences: Attention, involvement and memorability. Tourism Management, 63(December), 100–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.06.001

- Chen, C. F., & Phou, S. (2013). A closer look at destination: Image, personality, relationship and loyalty. Tourism Management, 36(June), 269–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.11.015

- Chhabra, D. (2005). Defining authenticity and its determinants: Toward an authenticity flow model. Journal of Travel Research, 44(1), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287505276592

- Chiu, W., Zeng, S., & Cheng, P. S. T. (2016). The influence of destination image and tourist satisfaction on tourist loyalty: A case study of Chinese tourists in Korea. International Journal of Culture, Tourism, and Hospitality Research, 10(2), 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-07-2015-0080

- Cohen, E., & Cohen, S. A. (2012). Authentication: Hot and cool. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(3), 1295–1314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.03.004

- Crompton, J. L. (1979). An assessment of the image of Mexico as a vacation destination and the influence of geographical location upon that image. Journal of Travel Research, 1(Spring), 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728757901700404

- Del Bosque, I. R., & San Martín, H. (2008). Tourist satisfaction a cognitive-affective model. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(2), 551–573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2008.02.006

- Domínguez-Quintero, A. M., González-Rodríguez, M. R., & Paddison, B. (2018). The mediating role of experience quality on authenticity and satisfaction in the context of cultural-heritage tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(2), 248–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1502261

- Dwinanda, R. (2019). Hingga Juli, 350 Ribu Wisatawan Kunjungi Museum Tsunami. Republika id. Retrieved August 25, 2020, from https://www.republika.co.id/berita/nasional/daerah/19/08/21/pwl8lq414-hingga-juli-350-ribu-wisatawan-kunjungi-museum-tsunami

- Engeset, M. G., & Elvekrok, I. (2015). Authentic concepts: Effects on tourist satisfaction. Journal of Travel Research, 54(4), 456–466. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514522876

- Eusebio, C., & Vieira, A. L. (2013). Destination attributes’ evaluation, satisfaction and behavioural intentions: A structural modelling approach. International Journal of Tourism Research, 15(1), 66–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr

- Fakeye, P. C., & Crompton, J. L. (1991). Image differences between prospective, first-time, and repeat visitors to the lower Rio Grande Valley. Journal of Travel Research, 30(2), 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759103000202

- Falk, F. R., & Miller, N. B. (1992). (PDF) A primer for soft modeling. University of Akron Press. University of Akron Press. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232590534_A_Primer_for_Soft_Modeling

- Forgas-coll, S., Palau-Saumell, R., Matute, J., & Tarrega, S. (2017). How do service quality, experiences and enduring involvement influence tourists’ behavior? An empirical study in the Picasso and Miró Museums in Barcelona. International Journal of Tourism Research, 19(2), 246–256. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2107

- Fotiadis, A. K., & Vassiliadis, C. A. (2016). Service quality at theme parks. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality and Tourism, 17(2), 178–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2015.1115247

- Frisvoll, S. (2013). Conceptualising authentication of ruralness. Annals of Tourism Research, 43(7491), 272–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2013.07.006

- Gannon, M. J., Baxter, I. W. F., Collinson, E., Curran, R., Farrington, T., Glasgow, S., Godsman, E. M., Gori, K., Jack, G. R., Lochrie, S., Maxwell-Stuart, R., MacLaren, A. C., MacIntosh, R., O’Gorman, K., Ottaway, L., Perez-Vega, R., Taheri, B., Thompson, J., & Yalinay, O. (2017). Travelling for Umrah: Destination attributes, destination image, and post-travel intentions. Service Industries Journal, 37(7–8), 448–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2017.1333601

- Gao, J., Lin, S., (Sonia), & Zhang, C. (2020). Authenticity, involvement, and nostalgia: Understanding visitor satisfaction with an adaptive reuse heritage site in urban China. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 15(April 2019), 100404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2019.100404

- Gartner, W. C. (1994). Image formation process. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 2(2–3), 191–216. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v02n02_12

- Gilmore, J. H., & Pine, J. B. (2007). Authenticity: What consumers really want. Harvard Business School Press.

- Gursoy, D., & Gavcar, E. (2003). Profil de la participation des touristes internationaux de loisirs. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(4), 906–926. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(03)00059-8

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., Black, W. C., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage Learning. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119409137.ch4

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hair, Jr, Joseph F., Hult, G. Tomas M., Ringle, Christian M., & Sarstedt, Marko. (2017). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). United States of America: Sage Publications, Inc. 9781483377445

- Han, H., & Hyun, S. S. (2015). Customer retention in the medical tourism industry: Impact of quality, satisfaction, trust, and price reasonableness. Tourism Management, 46(February), 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.06.003

- Han, H., & Hyun, S. S. (2017). Key factors maximizing art museum visitors’ satisfaction, commitment, and post-purchase intentions. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 22(8), 834–849. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2017.1345771

- Han, H., & Hyun, S. S. (2018). Role of motivations for luxury cruise traveling, satisfaction, and involvement in building traveler loyalty. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 70(November 2017), 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.10.024

- Hede, A. M., Garma, R., Josiassen, A., & Thyne, M. (2014). Perceived authenticity of the visitor experience in museums: Conceptualization and initial empirical findings. European Journal of Marketing, 48(7–8), 1395–1412. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-12-2011-0771

- Hsu, S. H. (2008). Developing an index for online customer satisfaction: Adaptation of American customer satisfaction index. Expert Systems with Applications, 34(4), 3033–3042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2007.06.036

- Huang, S., (Sam), Weiler, B., & Assaker, G. (2015). Effects of interpretive guiding outcomes on tourist satisfaction and behavioral intention. Journal of Travel Research, 54(3), 344–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513517426

- Hume, M. (2015). To technovate or not to technovate? Examining the inter-relationship of consumer technology, museum service quality, museum value, and repurchase intent. Journal of Nonprofit and Public Sector Marketing, 27(2), 155–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2014.965081

- Indonesia Travel. (2021). The Aceh Tsunami Museum - Indonesia Travel. Retrieved November 15, 2021, from https://www.indonesia.travel/gb/en/destinations/sumatra/banda-aceh/the-aceh-tsunami-museum

- Jiang, Y., Ramkissoon, H., Mavondo, F. T., & Feng, S. (2017). Authenticity: The link between destination image and place attachment. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 26(2), 105–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2016.1185988

- Kim, H., & Chen, J. S. (2016). Destination image formation process: A holistic model. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 22(2), 154–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766715591870

- Kim, J. H., Song, H., & Youn, H. (2020). The chain of effects from authenticity cues to purchase intention: The role of emotions and restaurant image. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 85(July), 102354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102354

- Kim, J. H. (2018). The impact of memorable tourism experiences on loyalty behaviors: The mediating effects of destination image and satisfaction. Journal of Travel Research, 57(7), 856–870. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517721369

- Kolar, T., & Zabkar, V. (2010). A consumer-based model of authenticity: An oxymoron or the foundation of cultural heritage marketing? Tourism Management, 31(5), 652–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.07.010

- Komarac, T., Ozretic-Dosen, D., & Skare, V. (2020). Managing edutainment and perceived authenticity of museum visitor experience: Insights from qualitative study. Museum Management and Curatorship, 35(2), 160–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2019.1630850

- Kuhzady, S., Çakici, C., Olya, H., Mohajer, B., & Han, H. (2020). Couchsurfing involvement in non-profit peer-to-peer accommodations and its impact on destination image, familiarity, and behavioral intentions. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 44(May), 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.05.002

- Kyle, G., & Chick, G. (2004). Enduring leisure involvement: The importance of personal relationships. Leisure Studies, 23(3), 243–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/0261436042000251996

- Lalicic, L., & Weismayer, C. (2017). The Role of Authenticity in Airbnb Experiences. In Schegg , Schegg, & Stangl, Brigitte (Eds.), Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism, (pp. 781–794). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51168-9

- Lee, S., Phau, I., Hughes, M., Li, Y. F., & Quintal, V. (2016). Heritage tourism in Singapore Chinatown: A perceived value approach to authenticity and satisfaction. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 33(7), 981–998. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2015.1075459

- Leigh, T. W., Peters, C., & Shelton, J. (2006). The consumer quest for authenticity: The multiplicity of meanings within the MG subculture of consumption. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(4), 481–493. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070306288403

- Loureiro, S. M. C. (2019). Exploring the role of atmospheric cues and authentic pride on perceived authenticity assessment of museum visitors. International Journal of Tourism Research, 21(4), 413–426. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2265

- Lu, L., Chi, C. G., & Liu, Y. (2015). Authenticity, involvement, and image: Evaluating tourist experiences at historic districts. Tourism Management, 50(October), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.01.026

- MacCannell, D. (2017). Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. The Political Nature of Cultural Heritage and Tourism: Critical Essays, Volume Three, 79(3), 289–303. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315237749-16

- Manfredo, M. J. (1989). An investigation of the basis for external information search in recreation and tourism. Leisure Sciences, 11(1), 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490408909512203

- Martilla, J. A., & James, J. C. (1977). Importance-Performance analysis. Journal of Marketing, 41(1), 77–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224297704100112

- Matzler, K., Bailom, F., Hinterhuber, H. H., Renzl, B., & Pichler, J. (2004). The asymmetric relationship between attribute-level performance and overall customer satisfaction: A reconsideration of the importance-performance analysis. Industrial Marketing Management, 33(4), 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0019-8501(03)00055-5

- McDowall, S. (2010). International tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: Bangkok, Thailand. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 15(1), 21–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941660903510040

- Museum Tsunami Aceh. (2021). Museum Tsunami Aceh. Retrieved October 21, 2021, from https://museumtsunami.id

- Nguyen, T. H. H., & Cheung, C. (2016). Chinese heritage tourists to heritage sites: What are the effects of heritage motivation and perceived authenticity on satisfaction? Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 21(11), 1155–1168. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2015.1125377

- Oliver, R. L. (1980). A Cognitive Model of the Antecedents and Consequences of Satisfaction Decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17(4), 460. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378001700405

- Park, E., Choi, B. K., & Lee, T. J. (2019). The role and dimensions of authenticity in heritage tourism. Tourism Management, 74(February), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.03.001

- Park, S. Y., Hwang, D., Lee, W. S., & Heo, J. (2018). Influence of nostalgia on authenticity, satisfaction, and revisit intention: The case of Jidong mural alley in Korea. International Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Administration, 21(4), 440–455. https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2018.1511497

- Pereira, V., Gupta, J. J., & Hussain, S. (2019). Impact of travel motivation on tourist’s attitude toward destination: Evidence of mediating effect of destination image. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348019887528

- Phelps, A. (1986). Holiday destination image - the problem of assessment. An example developed in Menorca. Tourism Management, 7(3), 168–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(86)90003-8

- Pike, S., & Ryan, C. (2004). Destination positioning analysis through a comparison of cognitive, affective, and conative perceptions. Journal of Travel Research, 42(4), 333–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287504263029

- Pine, J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1998). Welcome to the experience economy. Harvard Business Review, 76(4), 97–105.

- Prayag, G., Hosany, S., Muskat, B., & Del Chiappa, G. (2017). Understanding the relationships between tourists’ emotional experiences, perceived overall image, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. Journal of Travel Research, 56(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287515620567

- Ram, Y., Björk, P., & Weidenfeld, A. (2016). Authenticity and place attachment of major visitor attractions. Tourism Management, 52(February), 110–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.06.010

- Reisenzein, R. (2006). Arnold’s theory of emotion in historical perspective. Cognition and Emotion, 20(7), 920–951. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930600616445

- Rickly-Boyd, Jillian M. (2012). Through-the magic of authentic reproduction: tourists' perceptions of authenticity in a pioneer village. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 7(2), 127–144. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2011.636448

- Rosenbusch, J., Ismail, I. R., & Ringle, C. M. (2018). The agony of choice for medical tourists: A patient satisfaction index model. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 9(3), 267–279. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-10-2017-0107

- Saayman, M., Li, G., Uysal, M., & song, H. (2018). Tourist satisfaction and subjective well-being: An index approach. International Journal of Tourism Research, 20(3), 388–399. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2190

- Sharma, P., & Nayak, J. K. (2018). Testing the role of tourists’ emotional experiences in predicting destination image, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions: A case of wellness tourism. Tourism Management Perspectives, 28(December 2017), 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2018.07.004

- Slak Valek, N., & Williams, R. B. (2018). One place, two perspectives: Destination image for tourists and nationals in Abu Dhabi. Tourism Management Perspectives, 27(February), 152–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2018.06.004

- Steiner, C. J., & Reisinger, Y. (2006). Understanding existential authenticity. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(2), 299–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2005.08.002

- Thyne, M., & Hede, A. M. (2016). Approaches to managing co-production for the co-creation of value in a museum setting: When authenticity matters. Journal of Marketing Management, 32(15–16), 1478–1493. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2016.1198824

- Trilling, L. (1972). Sincerity and authenticity. Harvard University Press.

- Wang, N. (1999). Rethinking authenticity. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(2), 349–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00103-0

- Wu, H. C., Ai, C. H., Yang, L. J., & Li, T. (2015). A study of revisit intentions, customer satisfaction, corporate image, emotions and service quality in the hot spring industry. Journal of China Tourism Research, 11(4), 371–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388160.2015.1110545

- Yilmaz, Y., & Yilmaz, Y. (2020). Pre- and post-trip antecedents of destination image for non-visitors and visitors: A literature review. International Journal of Tourism Research, 22(4), 518–535. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2353

- Yusra Y, Eko C, Agus A, Azmi M, Ugiana G, Ching C and Lee Y. (2020). An investigation of online food aggregator (OFA) service: Do online and offline service quality distinct? Serb J Management, 15(2), 277–294. https://doi.org/10.5937/sjm15-24761

- Zatori, A., Smith, M. K., & Puczko, L. (2018). Experience-involvement, memorability and authenticity: The service provider’s effect on tourist experience. Tourism Management, 67(August), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.12.013

- Zhang, H., Fu, X., Cai, L. A., & Lu, L. (2014). Destination image and tourist loyalty: A meta-analysis. Tourism Management, 40(February), 213–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.06.006

- Zhang, S. N., Li, Y. Q., Liu, C. H., & Ruan, W. Q. (2019). How does authenticity enhance flow experience through perceived value and involvement: The moderating roles of innovation and cultural identity. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 36(6), 710–728. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2019.1625846