Abstract

Financial inclusion is an international policy agenda and can be achieved through financially literate people, who can make informed financial decisions and improve individuals’ well-being. The area of Financial Literacy and Financial Inclusion is fairly highlighted in the literature; however, the collective importance of how these two areas are researched together needs scholarly attention. This paper carries out a mapping, scientometric and content analysis by compiling studies at the intersection of financial literacy and financial inclusion from a sample of 10,091 studies spread over the last 45 years and conducted on a sample of more than 850,000 individuals worldwide. We find that the number of studies increases; by fields, Finance and Economics dominate the literature; by countries, most studies come from developed countries, in particular the US; by authors, citations are skewed and by measures; studies are moving from non-functional measures to functional measures. Overall, the interest in financial literacy in bringing financial inclusion and its multifaceted role is elaborated using conceptual framework following which future research is positioned. Thus, aiding policymakers, regulators, and academicians to know the distinction of Financial literacy in Financial inclusion and to identify the potential research areas.

Public interest statement

The answers to questions like will I be able to retire comfortably? Do I have enough money saved for my children? Can I afford emergency expenses? The answers to these lie in the importance of Knowledge about Finance, which is a requisite to effective money management for everyone. As this study combines multiple studies and highlights the multifaced importance of financial literacy and ownership of financial products, its usefulness is manifold. It gives a simplistic overview of what financial literacy is, why is it important and how it can be used to achieve financial inclusion and hence is beneficial for specialist and non-specialist readers.The importance of this work can be evidently established as in the series of projects under the theme of UNSDG, financial literacy and financial inclusion are specially highlighted as the major goals (8.10) out of 17 goals. Moreover, more than 1.7 billion adults are financially excluded globally, and lack of financial literacy is one of the main causes of it. As this study combines multiple studies and highlights the multifaced importance of financial literacy and ownership of financial products, the public must understand and comprehend its manifold usefulness in gaining better financial behaviours and wellbeing. Additionally, it gives a simplistic overview of what financial literacy is, why is it important and how it can be used to achieve financial inclusion and hence is beneficial for specialist and non-specialist readers.

1. Introduction

Financial inclusion, measured as access to and use of financial services; is a key enabler to eradicating poverty and enhancing prosperity (Demirgüç-Kunt & Klapper, Citation2012; D.-W. D.-W. Kim et al., Citation2018). It is also recognized as an important policy tool to achieve Universal Financial Access (UFA) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) by different developmental bodies (OECD, Citation2013; Robert et al., Citation2005). It hence is of high interest for policy makers in order to learn about drivers of financial inclusion and how these can be influenced by national-level policies.

Among the two parts of Financial inclusion; access and use, the “access” part deals with the supply side that addresses proximity of bank branches, financial depth, cost of financial services and the legal system, whereas; the “use” part entails to its demand side that discourses the use of financial services by customers. For effective functioning of financial institutions, both demand and supply sides play their due role; hence, knowledgeable customers who can make informed decisions are as much important as having a good financial infrastructure in place (Cole et al., Citation2011). Thus, the required financial knowledge stretched to financial literacy plays a significant role in the promotion of financial inclusion, creating an enhanced ability to plan, save and react to financial shocks (Atkinson & Messy, Citation2011; Klapper et al., Citation2013), and attempting to achieve poverty eradication and economic stability (Furtado, Citation2018; Honohan, Citation2004; Jayaratne & Strahan, Citation1996; Kar et al., Citation2011).

The increased emphasis in the area of financial literacy and financial inclusion (FL&FI) by developmental bodies, confirmed by the growing need faced by economies around the world, has made it a subject of sustained and rising interest in academia (M. M. Kim et al., Citation2018; Lusardi & Mitchell, Citation2011; Milian et al., Citation2019). Studies have explored the area of financial literacy broadly to advance measurement of individual literacy levels, in terms of financial stability and in the context of decisions and outcomes (Kezar & Yang, Citation2010; Lusardi & Mitchell, Citation2014; Mandell & Klein, Citation2007). The increasing developments in the literature and the depth of this field make it difficult for researchers to be updated and suitably aware of what different roles does financial literacy play to achieve financial inclusion. As a result, new researchers may face complexity to understand, access and examine the abstracts of this area.

To address this issue, shows various studies that have attempted to systematically collect and synthesize the body of literature in the area of financial literacy and financial inclusion through systematic literature reviews and meta-analysis (Brody et al., Citation2015; Duvendack et al., Citation2011; Fernandes et al., Citation2014; Goyal & Kumar, Citation2021; Kaiser & Menkhoff, Citation2017; M. Kim et al., Citation2018; Miller et al., Citation2014; O’Prey & Shephard, Citation2014; Pande et al., Citation2012). Although being thoroughly carried out, such traditional reviews do face some limitations such as; lack of combined focus on FL&FI, lack of objectivity, troubles in replicating, and researcher bias (Tranfield et al., Citation2003). Systematic mapping study, an alternate approach to give a preliminary sketch of the research area through mapping and scientometrics is used to reduce such limitations. Since this approach uses strong bibliographic software to analyze data, replication and transparency becomes obvious (Zupic & Čater, Citation2015). Further developments and advancements in these methods are under expansion in all the fields (Van Raan, Citation2014). Although bibliometric analysis is used in a recent study (Goyal & Kumar, Citation2021) but the sole focus of the review is on financial literacy and not financial inclusion.

Table 1. Previous reviews and their respective approaches

Keeping in view this omission in past reviews and the large body of available literature in FL&FI, it becomes increasingly important to provide a precise assessment of the academic achievements in the area. Another motivation behind conducting this study is that the target period of the UFA 2020 has come to an end, and any academic contributions made towards the UFA 2020 need to be assessed as a part of the monitoring phase. As per the World Bank, the goals of the UFA 2020 program are based on four drivers of financial inclusion and the combined efforts of all their critical enablers, one of which is financial literacy. A need for assessment of scholarly contribution towards the Global Goals (SDGs) drafted to eradicate poverty, protect the planet, and bring peace presents a third reason for a mapping study such as this one. A fourth reason is that the already existing published reviews on financial inclusion achieved through financial literacy are neither sufficient nor recent; and as far as could be gauged by the authors, no SMS exists in this area at all. Hence, the need to conduct such a review is clearly present.

With the need for this research clearly established, the current study formally attempts: 1) To combine the literature at the intersection of financial literacy and financial inclusion through a systematic mapping study and literature review; 2) To study the evolution of financial literacy, and financial inclusion in empirical literature; 3) To identify gaps and suggest untapped areas for further investigation; and 4) To frame a context of previously done scholarly work in order to position new research activities through a content analysis.

Given the vast area network of the field, this review will prove to be advantageous in identifying research trends over time and recognizing the main contributors and their specific domains, so that popular applications and practices can be highlighted. This mapping study and review can be potentially beneficial to varied groups. For research scholars with an interest in this area, the map can present a clear picture of existing work, thus enabling them to understand research trends and shape their own study to avoid the proverbial “reinvention of the wheel”. Additionally, as the map presents work done in the overlap of the two areas of FL & FI, future researchers can be guided in new directions within these interconnected fields. The highlighting of the most prominent connections between the two research areas can further indicate areas that require practical attention, as a guideline for practitioners and policymakers.

2. Background and related work

Global economies experienced huge drops in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) during the 2008 global financial crisis; the crisis affected not just the first world with productivity drops and shrinkage in exports, but the developing and underdeveloped countries were also hit hard. Countries like Brazil, China, India, USA, Russia, Germany, and the UK suffered decreases in their GDP in the last quarter of 2008; with central banks having to inject huge funds for the survival of the financial system worldwide (Birdsall & Fukuyama, Citation2011).

One of the leading causes of the financial crisis of 2008 was the evolution of complex financial products such as subprime mortgages, syndicated loans, and other securitized and collateralized debt instruments (Klapper et al., Citation2013). With such complexity, the need for a better understanding of these financial products and their associated risks increased manifold. As part of the efforts made to increase financial inclusion small investors were being reached out to, but greater efforts were needed now to educate these investors as well, to enable them to make better informed financial decisions. The lessons learned from the crisis motivated the developmental bodies to focus on taking corrective steps for the progression of financial institutions that form the backbone of an economy (Atkinson & Messy, Citation2011; Furtado, Citation2018).

The need to educate investors was recognized by OECD; the organization defines financial literacy as “a combination of awareness, knowledge, skill, attitude, and behavior, necessary to make sound financial decisions and ultimately achieve individual financial wellbeing”. In 2010, the organization conducted a survey to measure financial literacy levels of 14 countries (OECD, Citation2013). This survey was repeated in 2014 and according to the results that came in, more than 33% of adults worldwide were found to be uninformed about the concepts of interest, compounding, diversification, and inflation (Grohmann et al., Citation2018; Klapper & Lusardi, Citation2019).

The prevailing low levels of financial literacy and its increasingly clear and important link to financial inclusion became an international policy concern (Arun & Kamath, Citation2015; OECD, Citation2013). It was recognized that adults being deprived of access to basic financial services not only discourages formal savings but also plays a crucial role in the financial and economic development of a country (Demirguc-Kunt & Klapper, Citation2012; Honohan, Citation2004). This led the World Bank, in collaboration with 34 public and private sector partners, to devise an ambitious financial inclusion target plan, which became known as “Universal Financial Access 2020”(Bank, Citation2017) and United Nations to develop Sustainable Development Goal (UN SDG). According to UFA 2020 plan, The World bank envisaged increased financial access for individuals, to enable them to build their personal reserves, as well as to send and receive money for improved financial behaviors. The plan centers on creating a regulatory framework, increasing access to financial services, improving financial literacy, enhancing financial skills and attitudes, and channelizing digital payment. However, the mission of the UN SDG was to “Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all” to be achieved by 2030. There are 17 sub goals attached to UN SDG, where goal 8.10 is about financial institutional development and financial inclusion (GA, Citation2015).

Practitioners and academicians both turned their attention to this policy concern, prompting a vast literature in the field and hence focusing on both demand and supply side of financial inclusion. The supply side of financial inclusion research was tilted towards institutional factors like bank network, branches and the density of ATMs (N. Kumar, Citation2013; Sahay et al., Citation2015), access to savings and finance (Ardic et al., Citation2011; Dupas & Robinson, Citation2013) and their effect on macroeconomic variables is also established (Dabla-Norris et al., Citation2015).

Mainstream scholarship has also advanced the demand side of financial inclusion through establishing the multifaceted role of financial literacy and awareness of individuals in achieving financial inclusion goals (Morgan & Long, Citation2020). It is acknowledged that financially literate individuals are more likely to participate in financial markets and use services of financial institutions(De Bassa Scheresberg, Citation2013; Christelis et al., Citation2010; Van Rooij et al., Citation2011). For example, Lyons and Kass-Hanna (Citation2019) investigated the impact of financial literacy on financial inclusion using the data from Global Findex for MENA region and concluded that financial literacy effects financial inclusion depending upon the subjects under study, their economic and social vulnerability. It helps improve financial inclusion among poor and decreases the likelihood of informal borrowings for younger aged groups.

Where financial literacy impacts financial inclusion, it is also established as a moderator and a mediator too. Financial literacy acts as a moderator to financial behavior (Hayat & Anwar, Citation2016; Mutlu & Özer, Citation2021), firm growth in countries like Ghana (Adomako, Danso & Ofori Damoah, Citation2016) and Uganda (Bongomin, Ntayi et al., Citation2017). It also plays a mediating role, as shown by Xiao and Porto (Citation2017) who employed data from national financial capability study and exhibited that financial education and financial satisfaction are mediated by financial literacy, financial behavior, and financial capability. Financial behavior of children in Bangkok is mediated by financial literacy and numeracy (Grohmann et al., Citation2015).

A growing body of literature has also underlined the connection between other demand side factors and financial inclusion like socioeconomic and demographic factors in different regions of the world (Kanungo & Gupta, Citation2021; Wang & Guan, Citation2017). Among these, few studies have highlighted consumption, income, social capital, health, education and race (Mehari et al., Citation2021; Nandelenga & Oduor, Citation2020) whereas, others accentuate marital status, region and other socio-economic factors as contributors of financial inclusion (Davutyan & Öztürkkal, Citation2016). Demirgüç-Kunt and Klapper (Citation2013) used data of 143 countries and found that differences in income between countries and within countries influences financial inclusion, Allen et al. (Citation2016) used data of 123 countries to verify the role of income and education in account ownership and (Yan & Qi, Citation2021) found the additional role of family education in financial inclusion.

With income and education, gender also determines financial inclusion levels. As in many countries males are more likely to be financially included as compared to females. Morsy (Citation2020), from a data of 141 countries found that women are less financially included especially in the countries where presence of foreign banks is low and the educational gap between the genders is large. Materials and Methods

A Systematic Mapping Study is different from a systematic literature review in a few significant ways. There may be some commonalities between the two; however, an SMS emphasizes on the structuring of the evidence in the relevant research area, whereas the latter focuses on the synthesis of the evidence found (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Petersen et al., Citation2015). The two major types of literature review root back to medical sciences and have been replicated by other sciences based on the available methodologies and guidelines (Campbell et al., Citation2004). Both methods are used in this study first to map and then to synthesize the literature in the mentioned area.

Following the procedure established by Kitchenham (Kitchenham & Charters, Citation2007), this review comprises three phases: planning, conducting, and reporting. In the planning phase, the research question and detailed review protocol are developed. In the conducting phase, the review is executed and in the reporting phase, the review process, execution, and synthesis are documented.

2.1. Planning phase

In the planning phase, a review protocol was developed by carefully thinking about and documenting the following: (1) research question; (2) search strategy; (3) primary studies selection; (4) assessment of quality; (5) sketching data extraction strategy; and (6) designating synthesis methods. These activities as pertaining to the current study are explained in the following section

2.1.1. Research questions

With an aim to capture the efforts at the intersection of financial literacy and financial inclusion, following research questions have been drafted in researchers and practitioners’ interest. Based on the SMS and SLR guidelines (Paul & Criado, Citation2020; Petersen et al., Citation2015), the questions are also shown mapped to the research objectives in .

Table 2. Research questions and their mapping with objectives

It is important to note that the focus of this SMS & SLR is the published studies themselves, and not the analysis of the methodological approaches used by them. An analysis of the approaches used in the studies would certainly offer interesting insight, but would also be prone to mixed interpretations, and hence such ambiguity is avoided here.

2.1.2. Search strategy

To design a rigorous search strategy and predefine search strings in which maximum exposure of empirical literature in the subject area is ensured, the search strategy was divided into stages of pre-search, systematic search, and manual search. In the first phase, general keywords and their synonyms were searched to identify specific keywords repeatedly used in the retrieved articles. After that, a search based on the combination of all the identified keywords was carried out. After finding the relevant keywords, the second phase of a systematic search was carried out. The stepwise quasi-gold standard guidelines were adhered to as follows (Zhang et al., Citation2011): a) venues and databases identification, b) quasi-gold standard establishment, c) search strings elicitation, d) performance of automated search, and d) search results evaluation. In the third phase, a manual search was conducted to strengthen the search strategy and overcome the searching threat (Krüger et al., Citation2020) with the help of author search and snowballing (Streeton, Cooke, & Campbell, 2004). Snowballing is executed through scanning the references of the included publications—also known as backward snowballing; and scanning the citations of included publications—also known as forward snowballing. This study followed both standard snowballing procedures. The author search was also conducted by reviewing the publications of known authors in the specific research areas. The detailed quasi-gold standard establishment is given in the supplementary data.

The selected search repositories were Web of Science, Scopus, Database of Open Access Journals, Science Direct and Springer. Web of Science and Scopus were used as these are the databases that carry out a constant quality assessment for ranking, impact, influence, productivity, and prestige of journals and are common in social sciences. The other databases were used as they also show papers from prestigious journal.

2.1.3. Primary studies selection and review criteria

shows the review criteria followed for this SMS:

Table 3. Criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies

The inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied to all the retrieved primary studies and the decision was made accordingly for each outcome. The whole process was carried out by two independent reviewers. The title, abstract and keywords were screened during the first-level inclusion and potentially relevant studies were identified. The studies that did not match the objectives were excluded. Conflict resolution meetings were conducted for inter-reviewer disagreements, where a third independent reviewer acted as a scrum master if consensus between the two researchers was not achieved. The level 2 inclusion was carried out by the primary researcher, where studies were read in detail and validated by the second researcher. In case the article was found irrelevant at level 2, it was excluded, with the rationale for doing so being provided. Since a high inter-reviewer disagreement leads to a weak interpretation of results, the Kappa statistic, which is a quantitative measure of the degree of inter-reviewer agreement, was used to quantify inter-reviewer consensus. Two independent reviewers performed inclusion/exclusion at level 1. The criteria used for inclusion and exclusion is given in detail below:

2.1.4. Assessment of methodological quality

An independent quality assessment of all the studies was done by both reviewers according to the criteria identified for quantitative research, as per the principles of good practice and subject related guidelines (Luft & Shields, Citation2003). Most reviews do not perform a quality assessment of primary studies and hence do not provide quality assessment guidelines to professionals and do not carry much practical implications in the relevant area (Luft & Shields, Citation2003). The current study attempts to take care of these issues and uses a quality criterion that covers three core quality issues in evaluating the selected studies; these are rigor, credibility, and relevance.

2.1.5. Extraction phase

Studies retrieved from automated and manual searches were independently evaluated by the two researchers. Articles included at the first and the second levels, that is, the screening stage were considered for data extraction, using a data extraction form. Three studies were pilot tested by both reviewers for validation purposes, that is, identified from the one and validated by the other. This is a common practice in conducting systematic reviews. The detailed process of extraction was then conducted which included consideration of article characteristics such as title, year of publication, source, authors, co-authors, keywords, countries, references, citations, funding agencies and other details.

2.1.6. Data synthesis

The data synthesis was performed using two synthesis techniques: quantitative and qualitative. The quantitative synthesis comprises scoping and bubble plotting to combine the frequencies from the intersection of different sub-research questions and includes a detailed bibliometric analysis. Whereas the qualitative synthesis is based on the quality assessment of the evidence and summarizes the benefits and limitations of the classified publications.

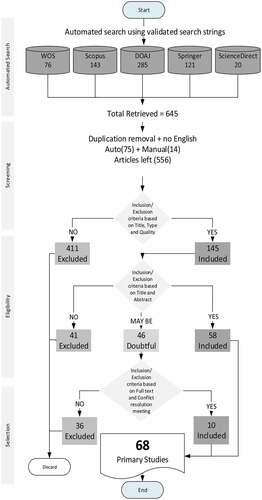

2.2. Conducting phase

The final search was conducted using the protocol articulated for the review. Six hundred and forty-five articles were retrieved from five databases. After removal of duplicate and non-English articles, 556 publications remained. The first-phase filter was applied on titles only, resulting in the inclusion of 145 articles. At phase 2, studies were classified into categories of “included”, “excluded”, and “doubtful” based on titles and abstracts and the resultant was 58, 46 and 41 respectively. For inter-reviewer agreement, the Kappa statistic (McHugh, Citation2012) was established. A third stage was executed for doubtful studies only, where consensus was achieved via discussion in a conflict resolution meeting and 10 studies were included. Hence, a total of 68 studies were identified in this way and form a part of this SMS.

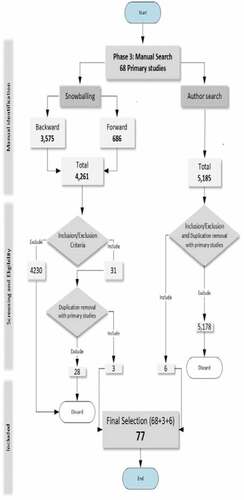

For manual search, the snowballing technique was used on the 68 primary studies. The process of backward snowballing yielded 3,575 studies whereas forward snowballing resulted in 686 studies. All of these were scanned and after duplication removal, 3 studies were finally added from the results of the snowballing. Author search was conducted for the authors and the co-authors of the primary studies and a total of 5,185 studies were reviewed. This yielded to an addition of 6 more studies to the final list. From manual search, a total of 9 publications were thus added to the list. Therefore, a final total of 77 primary studies forms a part of this SMS, after an overall 10,091 publications were reviewed at various stages during this SMS. Complete manual and automated flow process are given in , respectively.

2.3. Reporting phase

The list of primary studies selected for this SMS is also given in the supplementary material. Furthermore, the following section presents a detailed analysis to allow for convergence of the evidence found and to highlight the year-wise interest in FL&FI.

3. Mapping study results

The data for each of the RQs is presented in visual graphs and maps as per SMS recommendations and guidelines (Petersen et al., Citation2015).

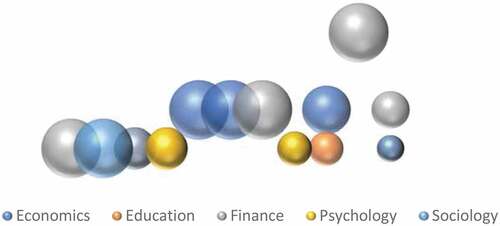

3.1. Areas covered

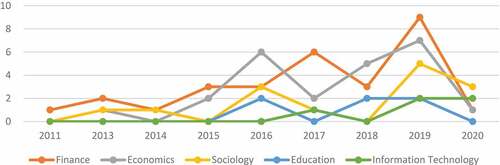

The breakdown of areas covered by the studies included in the SMS is given in , in response to RQ1(a). Due to the multidisciplinary interest of FL&FI, there is an overlapping of areas which is why more areas are covered by the primary studies. The major area that remains at the top is Finance, with Economics and Sociology following; all other areas are also shown through bubble chart in . The studies are also tagged with respect to sub-areas, which also tend to overlap, meaning that a study may simultaneously fall into two subcategories.

The answer to RQ1(b), showing the top five areas per year, is given in . The frequency shows that there is a mixture of evidence found each year. The number of primary studies published in the area of Finance is high in 2017 and 2019, whereas papers in areas of Economics and Sociology are mostly published in the year 2016 and 2019. Education and Information Technology areas also appear to increase after 2015. It is quite apparent from the low numbers seen in the figure, that the need for studies related to FL&FI in all other major areas is high; these include Psychology, Socioeconomics, Medical Sciences, Business Management, Environmental Science, Legal Studies, and Public Administration.

3.2. Methodological approaches & analysis

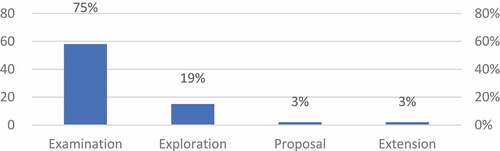

In response to RQ2(a), all reviewers classified the primary studies included in the SMS based on the type of papers by methodological approach. reports the four major approaches identified, and their count is presented in .

Table 4. Methodological approaches

Results show that more than 75% of the included studies examined the relation of FL& FI with other factors. About 19% of the studies focused on determining the factors that affect FL&FI; only about 3% of the studies proposed something new while around 3% extended previous work done in the subject area. Therefore, it can be inferred that more focus is on examining the relation of FL&FI with other factors, and less emphasis is placed on proposals and extensions in the area.

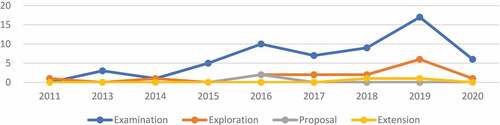

For further understanding, the year-wise trend analysis for RQ2(b) is also shown in . It clearly shows that examination prevails as the most frequently occurring approach through the span of years. We can see that although the use of the examination approach remains high throughout the time-period, the peak comes in 2019 when exploratory studies are also high in number. Overall, the trend increased significantly after 2017 for all types of methodologies.

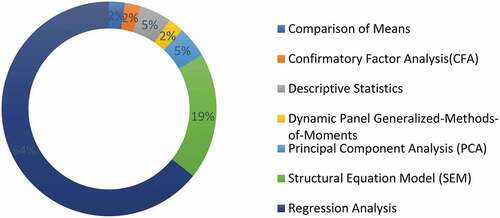

To answer RQ2(c) different quantitative methodological approaches used by the primary are identified in . It is observed that Regression Analysis is the most popular technique used in the FL&FI. The regression analysis is further divided into types of analysis and it is found that binomial, congressional, fixed effect, hierarchal, logit, multiple, ordinary least square and partial mediation.

In response to RQ2(d), presents the theories used in the area of FL&FI. The most used is lifecycle theory.

Table 5. Theories used in FL&FI literature

3.3. Methods

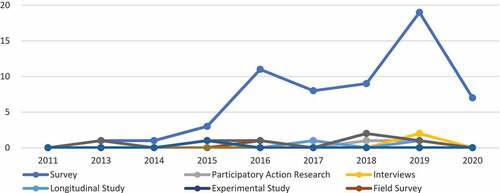

Almost all studies included in our SMS show some usage of evaluation methods, as can be seen from the response to RQ3(a). The major methods used in the area of FL&FI are surveys, longitudinal studies, field surveys, participatory action research, case studies, interviews, experimental studies, and post-experimental studies. With the survey type of evaluation dominating all other types, the other major evaluations uncovered include case studies, experimental studies, and longitudinal studies. Again, a rise in evaluations is seen after 2014, with 2019 showing the maximum usage of the survey type evaluation method. The number of studies with interviews as the major type of evaluation is also high in 2019 but tends to decrease in 2020.

In answering RQ3(c), it becomes apparent from that survey-type evaluations are more common in FL&FI; this is because of the high worldwide availability of survey data, which are collected by developmental bodies in collaboration with cooperation agencies like Global Findex. However, whether this trend continues in the future remains to be explored.

3.4. Venues

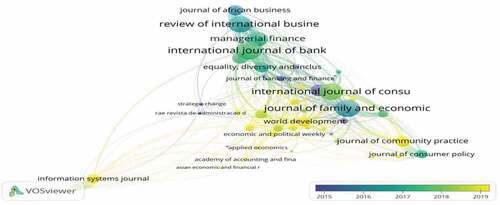

The possibility of two different subject areas showing work in similar studies was investigated through citations analysis, and a bibliographic coupling was done using the VOSviewer to answer RQ4(a). In general, venues are bibliographically coupled if their respective citations are common. shows the strength of the coupling that can be seen by the thickness of the lines connecting them. The total strength of the sources through bibliographically coupled links are visualized with fractional counting method. The sources are normalized based on modularity, with links selected based on higher weights. The layout starts from 1 and goes to a maximum of 1,000 iterations with 1.0 initial step size, 0.75 step size reductions, 0.001 convergence, and 10 iterations in the clustering of sources. Journal abbreviations are used in the VOS viewer.

From the year-wise trend between the venues, it can be clearly observed that the most common journals in all the bibliographies are the Journal of Family and Economic Issues, International Journal of Consumer Studies, International Journal of Scientific and Technology Research, and World Development. All others, however, do show some relation, as can be seen from the faint yet present connecting lines.

3.5. Countries

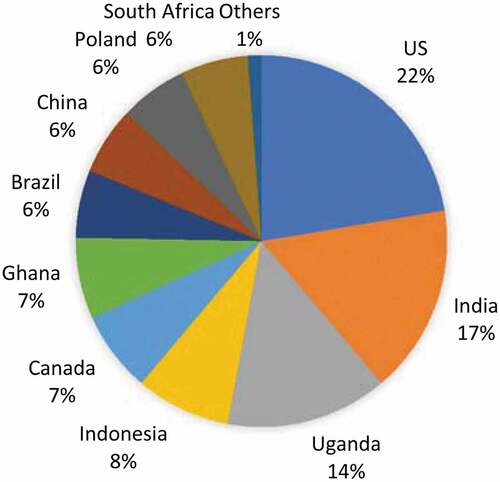

FL&FI research has taken place all over the world, with a few countries producing more concentrated research in the area. The highest research took place in the United States, with India a close second, to be followed by Uganda, Canada, Ghana, Brazil, China, Poland and South Africa, respectively. shows the break-down of countries producing FL&FI research using a pie chart.

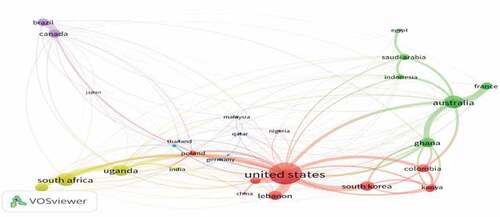

The bibliographic coupling of documents by countries, in response to RQ5(b), is done with the fractionalization method, using the modularity normalization method and with weights calculated based on total link strength. The network visualization shows the results. The country with the highest strength is the United States, showing high bibliographic coupling with Lebanon, South Korea, Kenya, and China, among others. All other coupled countries are also shown in the image in different colored links. The Global Findex databases, being the most comprehensive data set in this area, have been used in multiple countries.

3.6. Studies

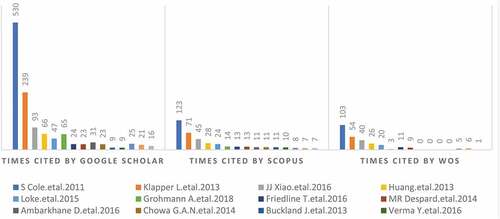

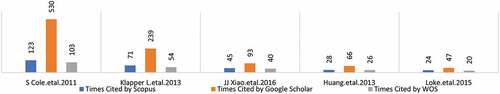

In response to RQ6(a), the top 15 most cited papers according to Scopus are shown in . For the purpose of a more comprehensive perspective, three major databases are considered as data points with a special focus on Scopus, since it is one of the major sources of primary studies that are included in this SMS. Cole et al. (Citation2011) is the most dominant paper in all three databases; however, a difference in the number of citations is quite apparent which is due to the different algorithms used by the databases to count citations. The second most cited paper as per all three databases is Klapper et al. (Citation2013).

The most dominant papers in the areas of interest are given in the to answer RQ6(c). Although varying with respect to citations, the sequence from all the data point remains the same, with S. Cole.et al.2011 appearing as the most cited paper in the area of Economics and Finance (). The papers are tagged in more than one area, due to which a paper can be dominant in multiple fields. The dominant papers in the area of Sociology are given in .

To answer RQ6(d), a semantic analysis has been performed in to see the frequency of two venues co-cited by a third venue. The semantic relation and the respective strength of each citation are evaluated through the number of co-citations.

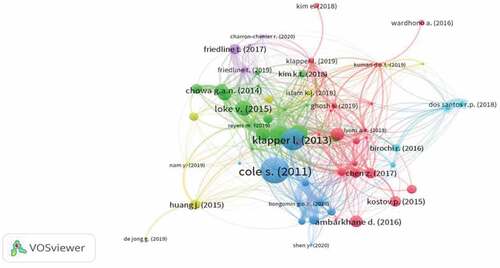

A similar pattern can be witnessed from the bibliographic coupling network based on citations, presented in in response to RQ6(e), where the most bibliographically coupled documents are S Cole.et al.2011 and Klapper L.et al.2013. The figure shows the bibliographic coupling network for other documents as well.

3.7. Authors

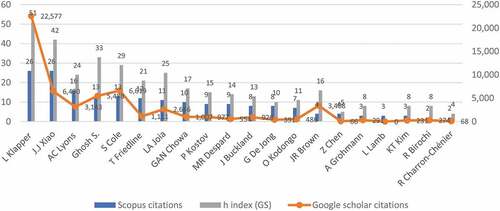

The main contributors in the area of FL&FI, as per RQ7(a) are identified through citation counts based on three criteria i.e. the Scopus provided h-index, the Google Scholar h-index, and total citations by Google Scholar. shows the most cited authors, where the dramatic drop in cited authors after the first four authors can be observed from the graph. This is not surprising as, in almost every area of research, a few more active members are the torchbearers. L Klapper is by far the most cited author in the area, which is undoubtedly due to many publications by L Klapper in the area of FL&FI, numbering more than 250. L Klapper is a Global Findex database founder and lead economist in the World Bank development research group. J J Xiao, AC Lynons, S Ghosh, and S Cole are also among the dominant contributors in the area of FL&FI.

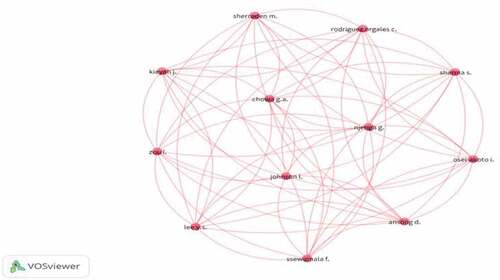

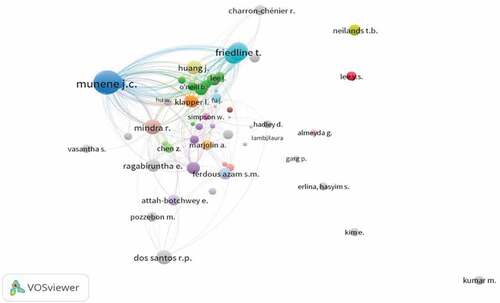

presents the network of co-authorship of authors in response to RQ7(b). The co-citations of cited authors are shown in (RQ7(c)), whereas the bibliographic coupling of authors in response to RQ7(d) is presented in .

3.8. Keywords

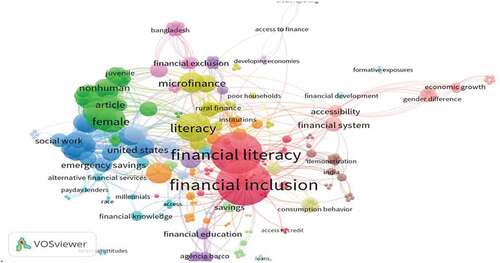

in response to RQ8(a), presents the co-occurrence of all keywords, showing the most used words are financial literacy and financial inclusion, in line with our objectives; other major keywords were financial education, literacy, microfinance, and emergency savings.

3.9. Interest

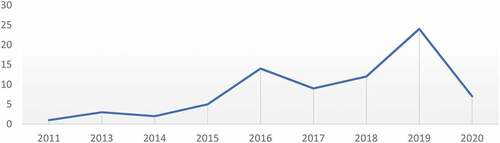

The overall interest, as measured by the frequency of publications in this area is seen in . The number of published papers per year shows an increase, which highlights the interest in FL&FI. A comparison of pre- and post-2014 can be made in the figure, to investigate the extent of the impact made by the introduction of the UFA2020 program on the increasing interest seen in academic research. The graph shows a marked increase after 2014, which was the year the UFA2020 was introduced. A drop in 2017 can be seen, after which the graph started to move upwards, continuing in 2018 and peaking in 2019. The overall graph shows a sudden decline in the year 2020. Possible reasons for this can either be the completion of UFA2020 or the fact that this is the cutoff year for our SMS.

4. SLR results

To answer RQ (10(a,b&c)), themes were formed using NVIVO SQL software. The emerged themes were 1) FL as a determinant, 2) FL as a moderator, 3) FL as a mediator and, 4) FL as a resultant. Along with these main themes formed, other factors highlighted in the literature are also made a part of the thematic analysis given in with their references numbers (the list is available in the supplementary data) and conceptual framework in .

Table 6. Themes and sub-themes formed for content analysis

4.1. Determinants

4.1.1. FL levels

Literature repeatedly finds financial literacy to be an important determinant of financial inclusion (Ambarkhane et al., Citation2016; Bongomin et al., Citation2018a; Ghosh, Citation2019; J, Citation2016; Poliakh, Citation2018; Potocki, Citation2019; Rastogi & Ragabiruntha, Citation2018). The impact of financial literacy on financial inclusion is a proportional one, whereby low literacy levels are seen to be linked with low financial inclusiveness (Deb, Citation2016; Friedline & West, Citation2016; Fu, Citation2020; Gill & Bhattacharya, Citation2017; M. Kumar et al., Citation2019; Mindra & Moya, Citation2017; Rizliyanto et al., Citation2017; Sayed & Shusha, Citation2019; Verma & Garg, Citation2016; Xiao & O’Neill, Citation2016).

As financial literacy increases, the ability to compare various competitive products offered in the financial markets is better developed, leading to improved financial decisions (Klapper & Lusardi, Citation2020), increased monetary benefits (Tony & Kavitha, Citation2020) and better financial access and inclusion (Kodongo, Citation2018; Kostov et al., Citation2015). This increase in financial literacy levels is also linked to increase in demand for both formal financial products (Chen & Jin, Citation2017) even in times of financial crisis (Klapper et al., Citation2013); such as debit cards (Grohmann et al., Citation2018) as well as informal financial products (Adetunji & David‐West, Citation2019; Gill & Bhattacharya, Citation2017). However few informal financial products like payday loan, which is typically a high-cost, short term loan till paycheck day, is observed to decrease with increase in financial literacy, indicating a fall in use of informal sources to cover cash shortages and other economic hardships (K. T. Kim & Lee, Citation2018).

Though economic hardships can certainly not solely be responsible for financial literacy or its lack thereof; however they do play a role in the state of an individual’s financial access and financial planning (Huang et al., Citation2015). It is seen that affordability plays a role in adoption of complex financial products; meaning that even highly financially literate individuals in the low-income bracket do not use these complex products due to the high cost associated with them (Friedline & Kepple, Citation2017). In a similar manner, the demand for complex financial services does also appear to rise with increased financial literacy in Indonesia and India, where financially educated customers make better financial decisions. In a study where individuals were asked to participate in financial education programs, more than 69% chose to attend, though once again, affordability seemed to affect continued demand. It was seen that financial incentives offered were more effective in the success of such financial inclusion initiatives, than merely an inclination in people towards gaining financial knowledge (Cole et al., Citation2011; Salignac et al., Citation2019).

4.1.2. FL Trainings and programs

Financial literacy can be increased through trainings and interventions, which can in turn help achieve better financial inclusion. Schools can also play an important role in increasing financial education and encouraging good financial practices too (Johnson et al., Citation2018). It is observed that children learn not only from the saving behaviors of their parents, but also from their discussions about saving or funds accumulation. This learning acts as early informal financial education for children, who get exposed to the ideas of saving and future financial planning at an early age (Arcos-Medina et al., Citation2016). Linked to this, mothers with high financial literacy scores are seen to be more financially included as well (Huang et al., Citation2013). The effects of different FL training programs are explored in two ways: pre and post-intervention analysis and post-intervention analysis.

4.2. Pre-post interventions

Studies are carried out to see the impact of financial literacy programs on financial behavior of individuals and their financial inclusiveness both before and after these programs were conducted. Their impact is observed to positively influence financial inclusion (Koomson et al., Citation2020; Tripathi et al., Citation2016) and saving behavior (Loke et al., Citation2015), with the probability of men getting financially included increasing by 8% and women by 7%, with this result more commonly seen in younger people rather than older ones (Koomson et al., Citation2020). These training programs interestingly help the trainers too, who end up increasing their own financial literacy levels while imparting trainings, which can benefit them in achieving improved financial wellbeing (De Jong et al., Citation2019).

4.3. Post interventions

In a similar manner, it is claimed that conducting financial literacy programs does positively affect financial inclusion of individuals (Deb, Citation2016; Joia & Dos Santos, Citation2019) and in entrepreneurs as they tend to increase dialogue and debate, critical thinking and meaningful learning, leading to social behavior that improves financial inclusion (Birochi & Pozzebon, Citation2016; Despard & Chowa, Citation2014). In India, a significant increase in account opening was witnessed after initiation of Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana (PMDY), a program aimed at increasing financial literacy of individuals and achieving financial access as a result (Verma & Garg, Citation2016). Likewise, in Boston, it is observed that financial coaching programs initiated by not-for-profit firms proved to be very meaningful in enhancing financial inclusion (Loomis, Citation2018).The interventions show their effect on the savings behaviors of orphans and people living with extended families and thus directly relate to financial inclusion (Sun et al., Citation2020).

However, studies show that the desire to be financially included is strongly influenced by the provision of financial incentives, such as subsidies; individuals offered financial incentives to open bank accounts and invest in other financial products. Hence, un-incentivized financial literacy programs prove to have lesser impact on financial inclusion (Cole et al., Citation2011) than those that are designed to work on removing financial access barriers (McGarity et al., Citation2020). In a similar manner, the effectiveness of the training programs increase when employees are better trained to explain complex products to customers that forges financial inclusion (Dos Santos & Antonio Joia, Citation2018).

4.3.1. Socio-economic and demographics

Demographics: A few dominant socio-economic and demographic factors link up with financial literacy levels to play a role in the financial inclusion and financial capacity of individuals, notably leading to improved financial decision-making (Danila et al., Citation2019a; Grohmann et al., Citation2018). A few of these dominant ones, such as age, gender, income, race, region, education, and family size, are discussed:

4.4. Age

Amongst the age groups studied, the middle age group is found to be more financially literate as compared to either of the extremes of the older or younger group of individuals (Klapper & Lusardi, Citation2020; Wardhono et al., Citation2016). However, the older age group is more likely to seek financial help to compensate for the lower financial literacy levels. Acceptance of expert financial advice, leading to investment in financial products is seen in this age group as well (M. Kumar et al., Citation2019; Wardhono et al., Citation2016). A u-shaped relationship between borrowing levels and age is seen, signifying high levels of debt in both the younger and the older age groups, as supported by the life cycle theory (Islam & Simpson, Citation2018; Klapper & Lusardi, Citation2020). The financial inclusion of individuals also differs based on the minimum age requirement for eligibility for opening bank accounts; in different countries, the range is wide, with as low as 7 years in Columbia,16 years in Nepal and 18 years in Kenya and Ghana (Johnson et al., Citation2018).

4.5. Gender

Gender is identified as another major determinant of financial inclusion. In low-income countries where women have limited financial access, men are found to be more financially literate and hence are more financially included as compared to women (Chowa & Despard, Citation2014; Klapper & Lusardi, Citation2020). However, this is not true in some countries, like Vietnam, where no significant difference between males or females is observed (Morgan & Trinh, Citation2019). It is also noted that in some regions like South Korea, gender, coupled with income status, has an impact on financial education levels. Low-income males are be less financially educated and unaware of the availability of varying interest rates in financial markets, hence end up paying higher interest rates (E. E. Kim et al., Citation2018).

4.6. Income

Like other demographic factors, mixed evidence is found regarding income being an important determinant of financial inclusion. Many studies point towards higher incomes leading to better financial inclusion, indicating some role played by income as a determinant of financial inclusion (Bongomin, Munene et al., Citation2017; Islam & Simpson, Citation2018; M. Kumar et al., Citation2019; Morgan & Trinh, Citation2019; Ofosu‐Mensah Ababio et al., Citation2020; Okello Candiya Okello Candiya Bongomin et al., Citation2016). In an interaction of demographic variables, high-income individuals in the older age bracket, are observed to be less financially literate; yet they tend to seek financial help to be able to plan for their financial wellbeing and become more financially included (Friedline et al., Citation2019; Gill & Bhattacharya, Citation2017). However, lower income individuals are more financially vulnerable (Buckland et al., Citation2013), less financially literate hence less financially included (Nam et al., Citation2019). In India and Burma, the link between low-income levels and low financial inclusion can be partly explained by the poor availability of financial services, especially the inconvenient day-time bank working hours. Daily wage earners are unwilling to miss out on a day’s earnings just to visit a financial institution for their financial needs (Shankar, Citation2015; Tambunlertchai, Citation2018; Verma & Garg, Citation2016).

A contrary finding is seen as well in literature, where income is realized to have no impact on financial inclusion (Wardhono et al., Citation2016), such as in Nigeria, where low-income families, with low financial literacy levels, tend to save at home rather than access financial institutions (Adetunji & David‐West, Citation2019).

Together with the levels of financial literacy (Klapper & Lusardi, Citation2020; Matchaba-Hove et al., Citation2019; McGarity et al., Citation2020; West & Friedline, Citation2016), the effects of income levels on financial inclusion have been found to vary, when seen in combination with the dynamics of social capital (Bongomin et al., Citation2016). Though it is observed that high-income individuals are more financially literate as compared to low-income individuals worldwide, an inequality exists between individuals living in rich countries and those living in poorer countries, in terms of GDP. The population below the poverty line in high-income nations are found to be 50% more literate as compared to their counterparts in lower income nations, whose financial inclusion is thus also adversely affected (Klapper & Lusardi, Citation2020). These low-income individuals have low financial literacy scores, showing a lack of awareness and inability to take advantage of any financial products available in the market, and hence make ill-informed financial decisions (Matchaba-Hove et al., Citation2019). In another study, age interacting with income levels shows that lower income millennials tend to have better financial literacy levels and hence depict better savings behavior (West & Friedline, Citation2016).

4.7. Race

Studies show that race as a demographic factor does play a role in levels of financial inclusion (K. T. K. T. Kim et al., Citation2019). It is observed that black people have less access to financial products, so that even with the same level of financial literacy as whites, the extent of accessibility and usage of financial products is different simply due to race. Blacks have reported resorting to informal means of credit due to this restriction in accessibility (Charron-Chénier & Seamster, Citation2020).

4.8. Region

Several variations have been seen in regional levels of financial inclusion (Bongomin et al., Citation2018a; Lyons & Kass-Hanna, Citation2019); even the basic practice of opening bank accounts varies for different parts of the world. In Kenya and Nepal, 60% males and 40% females have bank accounts; In Ghana and Columbia, the occurrence is 54% for both genders (Johnson et al., Citation2018). Nigerians on the other hand, altogether forego opening accounts, preferring to save at home (Adetunji & David‐West, Citation2019). The Chinese, tend to score low on financial literacy scores, with more frequent usage of informal sources of credit (Chen & Jin, Citation2017; Lyons & Kass-Hanna, Citation2019)

4.9. Education

Education is another important determinant of financial inclusion (Islam & Simpson, Citation2018; Wardhono et al., Citation2016)

4.10. Size of family

With large family sizes people tend to borrow payday loans and microcredit borrowing in Canada and Bangladesh to fulfil expenditures of the family, hence remain financially excluded (Islam & Simpson, Citation2018).

4.10.1. Personal factors

4.11. Attitude

Financial attitude and resilience towards distress and how individuals cope up in difficult times is an important determinant of financial inclusion (Bongomin, Munene et al., Citation2017; Buckland et al., Citation2013).

4.12. Self-efficacy

Self-accessed financial ability also termed as Financial self-efficacy contributes to financial inclusion more than objectively determined financial literacy (Mindra et al., Citation2017; Reyers, Citation2019)

4.12.1. Structural factors

Technological Infrastructure and Economic Stability

Technological infrastructure and economic stability result in more inclusive behaviors (Lyons & Kass-Hanna, Citation2019)

4.13. Moderators/ interacting factors

4.13.1. FL

Where FL is an important determinant of FI, its role as a moderator is also very much highlighted in the literature. It is established to moderate between the attitude of individuals and their intention to use financial services hence suggesting that through financial literacy individuals can be made financially included (Rahmawati et al., Citation2019). Financial literacy is also seen to moderate the relationship between financial access and SME growth (Bongomin, Ntayi et al., Citation2017).

4.13.2. Cognition

The mental process through which knowledge is acquired and comprehended is referred to as cognition. Where cognition plays a direct role in financial inclusion of poor people, it also tends to moderate the relationship between financial literacy and financial inclusion (Bongomin et al., Citation2018b)

4.13.3. Institutional factors

Institutional factors like information, financial access and incentives are highlighted in literature to play a role in achieving financial inclusion (Bongomin et al., Citation2018b), through a cross-sectional research using a data of 169 SMEs, Bongomin, Ntayi et al. (Citation2017) postulated that access to finance also positively effects SMEs growth in developing countries.

4.14. Mediators

4.14.1. FL

Financial literacy also tends to act as a mediator in achieving financial inclusion. Financial literacy partially mediates between institutional framing and financial inclusion, where institutional framing refers to how poor household structures, evaluate, interpret, and make financial decisions that are enhanced through financial literacy (Bhuvana & Vasantha, Citation2019; Bongomin, Ntayi et al., Citation2017). Institutional framing exhibits a direct relationship with financial inclusion; however, when financial literacy is introduced as a mediator it indirectly affects financial inclusion.

Studies have also found that financial literacy as an interacting variable enhances financial inclusion levels, in an otherwise weakly significant relationship between financial attitude and financial inclusion (Gill & Bhattacharya, Citation2017).

4.14.2. Social capital

When social capital is tested as a mediator between financial literacy and financial inclusion, it is noticed that financial literacy does not have a direct effect on financial inclusion (Reyers, Citation2019); thus also suggesting the important role of social capital(Mindra & Moya, Citation2017).

4.14.3. Financial self-efficacy

Self-efficacy, which is a measure of the confidence an individual has in his ability to assess financial products and make sound financial decisions, mediates the relationship between financial capability and financial inclusion (Reyers, Citation2019). Self-efficacy is found to be an important mediator between financial attitude, financial literacy and financial inclusion in urban and rural parts of Uganda (Mindra & Moya, Citation2017).

4.14.4. Information technology

The intensity of internet usage was found to work as a mediator between financial literacy and financial inclusion; emphasizing the importance of digital finance, especially for less financially included individuals (Shen et al., Citation2020).

4.15. Resultants

4.15.1. FL

Literature emphasizes the two-way role of financial literacy as a resultant too, when individuals are financial included and they are given financial literacy trainings it acts like a learning by doing process, they acquire more knowledge about the products offered in the market and hence it results in further increase in financial literacy of the masses (Lyons & Kass-Hanna, Citation2019).

4.15.2. Economic empowerment

Financial literacy leads to financial inclusion which as a result impacts women economic empowerment (Kumari & Ferdous Azam, Citation2019).

4.15.3. Financial stability and economic development

Financial literacy along with online banking and understanding it’s services are considered to drive financial inclusion, leading in turn to financial stability and economic development (Rastogi & Ragabiruntha, Citation2018).

4.15.4. Financial behavior and financial wellbeing

With financial inclusion, financial behavior improves (Brown et al., Citation2019; Friedline et al., Citation2019; Potocki, Citation2019); financially capable individuals are found more likely to depict positive financial behaviors as compared to financially included or educated ones (West & Friedline, Citation2016) and hence improve their financial well-being (McGarity et al., Citation2020).

5. Discussion

Financial literacy is a multi-faceted construct and its role in achieving financial inclusion is evident (Bongomin et al., Citation2018a; Klapper & Lusardi, Citation2020; Potocki, Citation2019; Rastogi & Ragabiruntha, Citation2018). This systematic review along with scientometric analysis, is an effort to deliver the most thorough presentation on the dynamic distinctions of the role of financial literacy in achieving financial inclusion. The findings of this study facilitate the policymakers, developmental bodies and academic scholars in knowing the diverse leads of financial literacy in achieving financial inclusion and hence identifying the relevant areas captivating investigation.

Several trends can be observed from the analysis, particularly a rise in the concentration of Finance and Economic based studies in the research area. The dramatic increase in FL&FI research after 2014 is also noticeable, as emphasized by government bodies and policymakers. Areas like Environmental Sciences, Medical Sciences, Legal Studies, and Public Administration have also been investigated within this subject matter which shoes that financial literacy is moving from non-functional measures to functional measures, though these areas have received much less attention, which highlights the potential for more research in these subject areas.

In terms of methodological approaches, examinations are by far the most adopted approach in FL&FI. Most studies have incorporated these methodologies, specifically OECD surveys that have been designed to be used globally. Exploratory studies carried out to identify the factors affecting FL&FI also make up a significant portion of the research done, with this number being proportional to the number of citations. Analysis of literature highlights that very few studies have used proposals and extensions as a methodological approach in the past; however, this trend is now changing in recent years, revealing prospective additions to methodological approaches and emphasizing room for development in the area.

A comparison with similar existing research would have served to add value to this study; however, no such SMS is published in FL&FI. An existing review in financial inclusion and mobile financial services is carried out by Kim et al., which is used as a comparison with the results of the SMS conducted. The results of the existing review show an overall increase in quantitative studies and highlight that demand side studies focus more on survey methods, where data is gathered from customers. Similar results can also be reported from another review (Goyal & Kumar, Citation2021) and our current SMS, which also identifies the survey method as being widely used in FL&FI with a growing trend observed after 2014. Most of the research in the area is done using data from surveys designed by developmental bodies such as the OECD or from already available global surveys.

The publication sites that have covered studies in the area of FL&FI are proportional to the bibliographic coupling between them. The results highlight that journals related to Finance, Development Economics, and Sociology publish the bulk of the research in the area of FL&FI.

In addition to examining publication sites, this SMS has also highlighted countries with the most concentrated research in the subject area under study. It has been observed that more than 70 percent of the research is conducted in developed countries with the highest publications in the United States. There are a few studies that have included more than one country in their sample but overall, there is a dearth of research conducted in developing countries in FL&FI.

Interestingly, analysis shows that the document citation number does not match with the author citation number, where an author from a comparatively low cited document is found to be the most cited author in the research area. Similarly, the author of the most cited document is not the most cited author in the studied research area. In contrast, an exploration into the co-citations and bibliographic coupling between the authors’ community both show a similar trend, with a select few authors considered to be torchbearers in the research area, which is a commonly occurring phenomenon.

In examining the network of co-authors, a higher level of isolation and divergence can be observed in the coupling as compared to the authors’ network; suggesting the possibility that authors may be more comfortable collaborating with a few familiar authors rather than with the authors they cite. This isolation makes it more difficult for new potential entrants to penetrate the area of FL&FI. This could also be a probable reason why the popular choice of methods used by new researchers is that of conducting readily available surveys. This tendency to form a close knit clique of researchers in this field opens a potential gap that can be filled in the future by bringing about more convergence in the methods, methodologies, and authors community.

The co-occurrence network of keywords and the tree-map are aligned to show the same keywords being used by many studies; these include financial inclusion, financial literacy, financial capability, financial education, and financial knowledge. However, it has additionally been observed that a few unrelated keywords have also been used, which can potentially lead to misdirected searches for future researchers in the process of looking up relevant literature. Important evidence can be potentially missed, or irrelevant studies picked up during the search phase, leading to an inflated number of studies in the inclusion/exclusion phase.

Findings of the content analysis suggest that financial literacy can play a determining, moderating, mediating, and leading role in financial inclusion. Interestingly, financial literacy helps understand complex financial products, people tend to buy them and then acquire more knowledge and as a result further increase in financial literacy is achieved. With increase in financial literacy levels, demand for formal and informal financial products rises and financial inclusion enhances. Financial training programs also influence the financial behaviors of individuals but incentives like affordability and financial access help achieve better financial inclusion. Along with financial literacy socio-demographic factors like age, education, gender, family size, race region and income; personal factors like attitude, self-efficacy; and structural factors like technology and economic stability contribute to financial inclusion. Financial literacy also acts as a moderator with other factors like cognition and institutional factors impacting financial inclusion. With FL being a multi-dimensional construct, it is also used as a mediator with social capital, financial self-efficacy, and IT to impact FI; and as a resultant of FI.

6. Limitations and threats

We also identify some limitations and threats which this study may suffer from and the measures taken to minimize those threats are also described below:

Descriptive validity is the degree to which the description of observations is objective and accurate and is measuring the theoretical constructs; theoretical validity refers to the theoretical explanations that fit the data; interpretive validity is the degree to which researchers are understood; researcher bias is introduced by the main researcher, who carries out the selection and data extraction and hence may allow personal views and perspectives; internal validity refers to how well the structure of the study is developed, and external validity is the degree of generalizability of the research outcomes, these threats are controlled by. The following section describes the steps taken by the authors to minimize the occurrence of any of the above-described threats.

All the constructs, that is, search strategy, inclusion/exclusion criteria, data extraction and quality assessment forms are designed carefully to achieve the research objectives. A quasi-gold standard for string elicitation and objectifying a detailed data extraction form and allowing room for revision. The data extraction form and quality assessment form are also validated from experts and piloted to ensure accurate data extraction. The data extraction forms are carefully designed according to the research questions and scope of the study.

Random data extraction and quality assessment on a sample are also performed in this SMS by a second and third reviewer to ensure that correct data is saved in the designated places.

A total of five important databases are searched to avoid the threat of missing any important evidence. Automated searching is also complemented by snowballing and the author search again to reduce the threat of missing important evidence. Most of the studies shortlisted from the references from snowballing have already been included/ excluded as primary studies, thereby proving that the conclusion of this review would not change.

Since this review compiles studies at the intersection of financial literacy and financial inclusion, the resultant primary studies are relatively low in numbers. If this condition is removed, the resultant studies with the term “Financial Inclusion” only from two databases Scopus and WOS results in a total of 753 studies. As this request goes too far and may result in a lot of noise and may lead to a new paper. The authors decided to stick to the objectives.

The time frame has been increased to ensure maximum coverage of evidence found in the literature which is from 1975 to 2020. As the initial selection process was conducted in 2019 and the report is written in mid-2020, so there can be a possibility of overlooking some studies that are published in early 2020. The authors decided to update the process of article selection by repeating the search steps in March 2020; hence ensuring that accepted articles of 2020 and 2021 are also a part of the screening process. However, the studies that are available after March 2020 date are not a part of this review.

It is expected that researcher bias remains at some level, as the conclusion is drawn by the researcher from the given data. Additionally, the gaps and future research identified are purely based on the authors’ views, which cannot be validated.

7. Conclusion and future work

Our study presents the first preliminary systematic assessment in FL&FI. It is formulated as a systematic mapping study and literature review to give an overview of 77 publications in the research area. It also allows for objective mapping in this knowledge area using descriptive graphs and scientometrics; and in-depth assessment using content analyses. We have concentrated our investigations on devising research questions in consideration of the UFA 2020 program and have attempted to generalize our recommendations based on our results. To enhance knowledge of the field and encourage transparency and repeatability of this SMS process, the data is made publicly available. Further investigations, extensions, and expansions in our data are encouraged.

It can be inferred from the findings of this review that FL literacy is a backbone of FI. The UFA program from an academic perspective seems to be achieved partially with regards to one of the pillars; awareness and financial literacy. Though financial literacy programs are conducted globally in both developing and developed countries, a large number of individuals are still financially illiterate, thus, leaving 1.7 billion adults without financial access (Demirguc-Kunt et al., Citation2018). Based on the analysis conducted in the study, the following recommendations are formed: (1) Due to the in-depth existing research on FL&FI, a comprehensive literature review is required to understand, modify, develop, and propose new methods of analysis so that replication of the exhaustively used survey method can be avoided. As stated earlier, most studies have opted for this approach, and if newer approaches are not introduced and experimented with, future studies may have a higher chance of overlap, and a lesser chance of contributing value. (2) An excellent opportunity exists in the shape of a shortage of work done in developing countries; hence focus of future research could be directed here. Additionally, the fields of study other than the usual areas of Finance, Economics, and Sociology need to be investigated, to highlight how FL&FI pertains to them. (3) Authors should intend to collaborate and converge between distinct groups, to bring to the fore diverse views, approaches, and angles of thought. (4) Precision and clarity in the title and abstract, plus the use of common keywords are very essential for an effective search phase, and for the inclusion of current and future review studies in the search phase. Future work can be carried out to answer the research Questions like 1) How is FL different from Financial Knowledge and which affects more in FI? 2) How is the relationship between FL and FI affects cultural factors across various groups of population? 3) Is financial literacy in developing countries improved overtime? 4) Are all FL interventions equally effective across various cohorts of populations worldwide? 5)Is digital FL different from FL? How? 6)What is the role of the remaining three pillars of product design, payment streams, and access points in achieving financial access? Answers to these questions would serve to give a comprehensive and overall picture of work in this research area and the way forward. The targeted studies would aim to not only map out existing work but also to bring forth unaddressed research questions that can very well form the basis of future studies.

Author statement

Falak khan (the main author) is a PhD scholar at FAST School of Management (FSM), National University of Computer and Emerging Sciences (NUCES), Islamabad, Pakistan. With over a decade of experience in the field of finance, she specializes in financial literacy and financial inclusion. Dr. Muhammad Ayub Siddqui is a Professor and Dean at FSM, NUCES, Islamabad, Pakistan. His interests are financial modelling and quantitative methods related to Economics and Finance. With over 28 years of teaching and research experience in this area, he has published in well-reputed journals and has presented his work in multiple conferences. Dr. Salma Imtiaz holds a PhD in Computing, she is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Computer Science and Software Engineering (DCSSE), International Islamic University, Islamabad (IIUI). Her interests are Global Software Development, Systematic Mapping, Literature reviews and Scientometrics. She heads the Software Engineering Research Group at IIUI. She has presented at national and international conferences and serves as a reviewer to many journals.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Falak Khan

Falak Khan(the main author) is a PhD scholar at FAST School of Management, National University of Computer and Emerging Sciences, Islamabad, Pakistan. With over a decade of experience in the field of finance, she specializes in financial literacy and financial inclusion.

Muhammad Ayub Siddiqui

Dr. Muhammad Ayub Siddiqui is a professor and dean at FAST School of Management, National University of Computer and Emerging Sciences, Islamabad, Pakistan. His interests are financial modelling and quantitative methods related to Economics and sub-disciplines of Management Sciences. With over 28 years of teaching and research experience in this area, he has published more than 40 articles in well-reputed journals and has presented his work in multiple local and international conferences.

Salma Imtiaz

Dr.Salma Imtiaz is an assistant professor at Department of Computer Sciences and Software Engineering, International Islamic University, Islamabad, Pakistan. Her interests are Global software, requirement engineering and mapping and scientometrics.

References

- Adetunji, O. M., & David‐West, O. (2019). The relative impact of income and financial literacy on financial inclusion in Nigeria. Journal of International Development, 31(4), 312–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3407

- Adomako, S., Danso, A., & Ofori Damoah, J. (2016). The moderating influence of financial literacy on the relationship between access to finance and firm growth in ghana. Venture Capital, 18(1), 43–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2015.1079952

- Allen, C. R., Angeler, D. G., Cumming, G. S., Folke, C., Twidwell, D., & Uden, D. R. (2016). Quantifying spatial resilience. Journal of Applied Ecology, 53(3), 625–635. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12634

- Ambarkhane, D., Singh, A. S., & Venkataramani, B. (2016). Measuring financial inclusion of indian states. International Journal of Rural Management, 12(1), 72–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973005216633940

- Arcos-Medina, G., Hernández-Romero, O., & Zapata-Martelo, E. (2016). Ahorro infantil, un acercamiento a la inclusión financiera. chispitas de la fundacion ayú, oaxaca, México. Agricultura, Sociedad Y Desarrollo, 13(3), 473–492. https://doi.org/10.22231/asyd.v13i3.407

- Ardic, O. P., Heimann, M., & Mylenko, N. (2011). Access to financial services and the financial inclusion agenda around the world: A cross-country analysis with a new data set. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper(5537).

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Arun, T., & Kamath, R. (2015). Financial inclusion: Policies and practices. IIMB Management Review, 27(4), 267–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iimb.2015.09.004

- Atkinson, A., & Messy, F.-A. (2011). Assessing financial literacy in 12 countries: An OECD/INFE international pilot exercise. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10(4), 657–665. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474747211000539

- Bank, W. (2017). UFA2020 overview: Universal financial access by 2020.

- Bhuvana, M., & Vasantha, D. S. (2019). Ascertaining the mediating effect of financial literacy for accessing mobile banking services to achieve financial inclusion. International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering (IJRTE), , 2277–3878.

- Birdsall, N., & Fukuyama, F. (2011). New ideas on development after the financial crisis. JHU Press.

- Birochi, R., & Pozzebon, M. (2016). Improving financial inclusion: Towards a critical financial education framework. Revista de Administração de Empresas, 56(3), 266–287. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-759020160302

- Bongomin, G. O. C., Munene, J. C., Ntayi, J. M., & Malinga, C. A. (2017). Financial literacy in emerging economies: Do all components matter for financial inclusion of poor households in rural uganda? Managerial Finance, 43(12), 1310–1331. https://doi.org/10.1108/MF-04-2017-0117

- Bongomin, G. O. C., Munene, J. C., Ntayi, J. M., & Malinga, C. A. (2018a). Nexus between financial literacy and financial inclusion. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 36(7), 1190–1212. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-08-2017-0175

- Bongomin, G. O. C., Munene, J. C., Ntayi, J. M., & Malinga, C. A. (2018b). Nexus between financial literacy and financial inclusion:: Examining the moderating role of cognition from a developing country perspective. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 36(7), 1190–1212.

- Bongomin, G. O. C., Ntayi, J. M., & Munene, J. C. (2017). Institutional framing and financial inclusion: Testing the mediating effect of financial literacy using SEM bootstrap approach. International Journal of Social Economics, 44(12), 1727–1744. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-02-2015-0032

- Bongomin, G. O. C., Ntayi, J. M., Munene, J. C., & Malinga, C. A. (2017). The relationship between access to finance and growth of SMEs in developing economies: Financial literacy as a moderator. Review of International Business and Strategy.

- Bongomin, G. O. C., Ntayi, J. M., Munene, J. C., & Nabeta, I. N. (2016). Social capital: Mediator of financial literacy and financial inclusion in rural Uganda. Review of International Business and Strategy.

- Brody, C., De Hoop, T., Vojtkova, M., Warnock, R., Dunbar, M., Murthy, P., & Dworkin, S. L. (2015). Economic self‐help group programs for improving women’s empowerment: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 11(1), 1–182. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2015.19

- Brown, J. R., Cookson, J. A., & Heimer, R. Z. (2019). Growing up without finance. Journal of Financial Economics, 134(3), 591–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2019.05.006

- Buckland, J., Fikkert, A., & Gonske, J. (2013). Struggling to make ends meet: Using financial diaries to examine financial literacy among low-income canadians. Journal of Poverty, 17(3), 331–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875549.2013.804480

- Campbell, S. E., Seymour, D. G., & Primrose, W. R. (2004). A systematic literature review of factors affecting outcome in older medical patients admitted to hospital. Age and Ageing, 33(2), 110–115. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afh036

- Charron-Chénier, R., & Seamster, L. (2020). Racialized debts: Racial exclusion from credit tools and information networks. Critical Sociology, 0896920519894635.

- Chen, Z., & Jin, M. (2017). Financial inclusion in China: Use of credit. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 38(4), 528–540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-017-9531-x

- Chowa, G. A., & Despard, M. R. (2014). The influence of parental financial socialization on youth’s financial behavior: Evidence from ghana. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 35(3), 376–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-013-9377-9

- Christelis, D., Jappelli, T., & Padula, M. (2010). Cognitive abilities and portfolio choice. European Economic Review, 54(1), 18–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2009.04.001

- Cole, S., Sampson, T., & Zia, B. (2011). Prices or knowledge? What drives demand for financial services in emerging markets? The Journal of Finance, 66(6), 1933–1967. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2011.01696.x

- Dabla-Norris, M. E., Ji, Y., Townsend, R., & Unsal, M. F. (2015). Identifying constraints to financial inclusion and their impact on GDP and inequality: A structural framework for policy. International Monetary Fund.