?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study is aimed to examine the impact of income diversification on bank risk in Vietnam before and during the COVID-19 pandemic by studying commercial banks over the period 2012–2020. By employing the fixed effects model (FEM) and general least squares model (FGLS), our main result shows that the higher the level of income diversification, the lower the risk of default. However, the diversification strategy should be conducted based on each source of non-interest income, in particular banks need to limit the increase in direct income from service activities, and reduce service fees to increase other indirect revenues, such as benefiting from transaction size and CASA value. This is different from previous studies. Besides, banks should improve the quality of foreign exchange business, securities investment and increase income from other non-interest activities. We also find that bank’s default risk tends to decrease when the COVID-19 pandemic breaks out. However, contrary to our hypothesis, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the relationship between income diversification and default risk of commercial banks in Vietnam has not been confirmed.

1. Introduction

The notion of diversification is a basic principle of modern finance theory. As a result of rising competitive pressures from both international and domestic rivals, regulatory reform, and technological improvement, increasing the number of financial institutions, banks must diversify by expanding beyond traditional lending activities into a variety of non-interest income activities (Allen & Santomero, Citation2001). Generally speaking, non-interest income is a mixture of heterogeneous components that generate income other than interest income. It comprises fee and commission income and trading, fiduciary activities, providing insurance, providing payment services, and other services.

A growing body of studies has examined the impact of diversifying banks’ revenue sources on their stability during the last fifteen to twenty years. According to Stiroh and Rumble (Citation2006), non-interest income amounted to 42 percent of all operational revenue for US banks in 2004, compared to only 20% in 1980. In the developed financial countries of the world, the proportion of non-interest income in the total income of banks is over 40% (according to the World Bank—Global Development Finance Database up to the end of 2017). In Vietnam, although the proportion of net income from service activities in total income tends to increase, the growth rate is slow and does not reach the headlines in the Vietnam Banking Development Strategy to 2025, with a vision to 2030 (only reached 10.4%, while the standard level is 12–13% by the end of 2020). Therefore, this issue has been studied by several authors both in the context of developed and emerging countries. However, the conclusions are inconsistent in different countries and regions. Doumpos et al. (Citation2016), C. Wang and Lin (Citation2021) showed that income diversification can be more beneficial for banks operating in developing countries, while it has no significant impact on bank risk in advanced and major advanced economics. Meanwhile, in Vietnam, some previous studies found that income diversification adds to risk (Batten & Vo, Citation2016; Vinh & Mai, Citation2015) due to alternate sources of funding hampered by undeveloped financial markets. On the other hand, Pham and Pham (Citation2020) argue that the diversification of commercial banks is not significantly related to bank risk, another finding of Pham et al. (Citation2021) supports the concept of economies of scope that claims diversified banks utilize redundant resources and customer base in a crisis period when banks’ lending activities were seriously affected and resulted in increased non-performing loans and liquidity risks.

In this paper, more updated data encompassing the years of the post-crisis period are analyzed to cover the long journey in the development of modern payment products and services based on information technology applications as well as vigorous growth of Vietnam’s stock market in recent years. The number of Vietnamese firms with market capitalizations of over USD 1 billion rose from 10 in 2015 to nearly 50 in 2021. In addition, COVID-19 pandemic requires banks to take various actions to cope with such as increasing provision for risks or restructuring their sources of income. The economic slump in the early months of the pandemic rivaled the initial declines of the Great Depression. Similarly, due to due to government-mandated forbearance rules, COVID-19 pandemic caused an economic downturn and put pressure on banks’ lending activities. Finally, we will analyze each type of non-interest income to default risk to propose the most effective business strategy of the bank. This is important, since different sources of income might have varied effects on risk. That is why our paper is aimed to fill in the gap by (i) measure the level of income diversification for commercial banks in Vietnam, an emerging market; (ii) evaluate the impact of diversification strategies on the risk of banks; and (iii) examine the relationship between income diversification and bank risk during COVID-19 with the empirical evidence from Vietnam.

2. Literature review

2.1. Default risk of commercial banks

A firm’s default happens when it is unable to meet its financial obligations. In a bank, default risk refers to the perceived likelihood that a bank will be unable to meet the required payments (principal or interest) on its debts. As banks are a financial intermediary—that is, an institution that allocates funds from savers to borrowers in an efficient manner, which makes them a key component of the financial system. The default of a single bank may cause a cascading failure, which does not only affect that single company but can spill over to other (i.e., financial and non-financial) institutions. In this situation, the failure of a bank can become a systemic risk (Bühler & Prokopczuk, Citation2010). Therefore, this issue deserves special attention and banks need to take action to lower default risk.

Default risk can be measured in various ways, depending on the aspects and focuses of different research. Saeed and Izzeldin (Citation2016) quantified a bank’s default by using a Merton type bank default measure. Bank default risk is calculated by means of the distance to default (D-to-D) approach using stock market prices and annual accounts. A restriction on the use of D-to-D is that it limits consideration to publicly listed banks. A bank’s exposure to systemic risk is measured by the Marginal Expected Shortfall (MES), as proposed by Acharya and Steffen (Citation2013). Another measure used by Doumpos et al. (Citation2016) is a novel overall financial strength indicator (OFSI) that takes simultaneously into account various elements of bank performance and risk. Some banking studies have partially improved upon this by relating diversification to risk using the Z-score index, an indicator of a bank’s probability of insolvency (e.g., Mercieca et al., Citation2007; Stiroh, Citation2004). This index considers not only the standard deviation of return on assets but also the average return on assets and the average equity to assets over a fixed time period. Risk is measured by the standard deviation of return on assets (SDROA) and of return on equity—SDROE (Lepetit et al., Citation2008) or RAROA and RAROE mean risk-adjusted ROA and risk-adjusted ROE (Batten & Vo, Citation2016).

2.2. Bank income diversification

2.2.1. Concept of bank income diversification

Diversification is the process by which a locality, a company, or an individual seeks to increase its field of activity or production to reduce the risks associated with over-specialization. It is an unsystematic risk reduction method that is frequently used in investment management

Diversification of bank income means that the bank supplements and enriches income sources by diversifying business activities, products, services, etc. within the framework permitted by law. Due to income diversification, commercial banks will have two income components, i.e. interest income and non-interest income.

Research by Mercieca et al. (Citation2007) identified three trends in income diversification in banks: diversification of financial services products, geographical diversity, and combination of geographical diversification management and business. According to Elsas et al. (Citation2010), commercial banks often diversify income by shifting traditional business activities to non-traditional activities to increase the proportion of non-interest income in total income.

According to Lipczynski (Citation2005), income diversification strategies include income diversification by expanding types of products and services, increasing markets, and growing markets through drug diversification. This finding is consistent with a number of the level of financial market development (e.g., Vithessonthi (Citation2014); Vithessonthi and Kumarasinghe (Citation2016).

2.2.2. Measurements of income diversification

The AHHI factor considers the proportional significance of each component of net operating income (interest and non-interest) as well as the “non-linear connection of non-interest income” (Stiroh & Rumble, Citation2006). Following Sanya and Wolfe (Citation2011), we calculate the AHHI as follows:

Where:

FEE = Fees and commission income

NON = Non-interest income for conventional banks

TRD = Trading income from foreign exchange transactions and trading securities

OTR = Other non-interest income.

In addition, measuring income diversification through the Herfindahl—Hirschman Index (HHI). HHI is measured by dividing total income into interest income and non-interest income.

Where:

NOI = Net operating income

NII = Net interest income for conventional banks

Along with the division of income into two sources, to explain the characteristics of income sources that may be negative and to facilitate interpretation of the meaning of the index, the studies of Stiroh and Rumble (Citation2006), Chiorazzo et al. (Citation2008) used the DIV index to measure the income diversification variable as follows:

DIV has a value of 0 to 0.5. A bank with a rating of zero has only one source of income (specialized), whereas a bank with a value of 0.5 has a balanced income.

2.3. Impact of diversification on the default risk of commercial banks

Under the pressure of competition, financial agents are more inclined to provide comprehensive services, increasing income diversification among commercial banks. The financial community is now arguing for a serious reassessment of the advantages and disadvantages of bank diversification on bank risk.

Academic research reflects these changes from a market perspective. Earlier studies predominantly claim that bank diversification provides economic benefits. Firstly, Markowitz (Citation1952) introduced portfolio theory which is also called mean-variance portfolio theory. It suggests that efficient diversification of investments could reduce the unsystematic risk. When a bank diversifies its investments or activities, the risks faced by banks will be reduced. The second point is the synergy effect’s scope economies. Banks can get low-risk revenue when they go into new operations because of the better information provided by their existing activities.

In empirical studies, scholars provide evidence that supports the common-sense assumption of banks reducing risk through diversifying their activities. Starting with Templeton and Severiens (Citation1992), who highlighted banks may reduce market risk by diversifying their operations by studying the effect of the diversification of non-bank activities on the risk of the 100 largest U.S. BHCs for the period from 1979 to 1986. Cornett et al. (Citation2002) argue that commercial banks can decrease risk through diversification because of the low correlation of returns among securities and bank subsidiaries. In Europe, Chiorazzo et al. (Citation2008) discovered a positive relationship between revenue diversification and risk-adjusted return in a sample of 85 Italian banks between 1993 and 2003. DeYoung and Torna (Citation2013) use data from commercial banks in the United States during the financial crisis to imply that banks’ risk of bankruptcy may reduce because of fee-based non-interest operations, whereas asset-based non-interest activities may increase the risk of bankruptcy. Kohler (Citation2014) discovered that non-interest income reduces the risk of banks with a retail-oriented business plan using data of German banks, whereas it increases the risk with an investment-oriented business strategy. In addition, Abedifar et al. (Citation2018) argue that banks with assets between $100 million and $1 billion that have a greater share of fiduciary income have lower credit. In Asian economies, Pennathur et al. (Citation2012) found that commission and handling fee income significantly reduced the risks faced by public sector banks in India, however, the results for private banks are the inverse. Conducting research on Chinese commercial banks from 2004 to 2018, Zhang et al. (Citation2020) suggest that income diversification has a double-edged sword effect on bank risk in China. Specifically, diversification reduces pre-loan risk but increases the post-loan risk of banks. However, in the state-owned commercial banks where government function is primary, diversification reduces both pre-and post-loan risk.

Cross-economy studies provide further supporting evidence. Examining the link between activity diversification and the interest margin of 262 Asian banks from 1997 to 2005, Lin et al. (Citation2012) claimed that diversifying banks’ income sources diversifying lowers the sensitivity of net interest margins to risk fluctuations. Similarly, Edirisuriya et al. (Citation2015) also find that diversification could increase bank solvency in South Asia Bank. According to Doumpos et al. (Citation2016), income diversification could improve banks’ financial strength, especially in less developed countries. Using a dataset including the banking markets of all 34 OECD countries, Kim et al. (Citation2020) claim a nonlinear relationship between diversification and stability across periods before, during, and after the crisis. They suggest that a moderate degree of bank diversification increases bank stability, but excessive diversification has an adverse effect and during the crisis, banks need to focus on traditional intermediation functions rather than diversifying their activity. C. Wang and Lin (Citation2021) collect a large sample of commercial banks in the Asia Pacific from 2011 to 2016 and indicate that banks with higher levels of income diversification face less risk.

On the flip side, scholars suggest that there are also implicit costs that are associated with diversification. DeYoung and Roland (Citation2001) attribute it to increasing non-interest revenue volatility, more fixed costs for banks entering new lines of business, and lower regulatory capital reserve for non-credit businesses. Lack of management skills and information in the new product market, and more agency problems owing to a more complicated organization and product structure are some of the other reasons for the increased risk (Acharya et al., Citation2006; Baele et al., Citation2007). In addition, diversification aggravates information asymmetry. Managers, for example, may withhold privileged information and exaggerate their department’s resource requirements to convert these resources to their own profit (Harris et al., Citation1992). These points are supported further by Stiroh’s (Citation2004) findings, which show that non-interest income is substantially more variable than interest income and fee-based activities are more volatile than interest-based activities. Trading operations are also noted to raise bank risk since they rely substantially on volatile market conditions. Greater trading revenue is related to greater risk (Lepetit et al., Citation2008). Fee-based and commission revenue also have a positive and large impact on bank risk in small banks. Similarly, Grassa (Citation2016), and Elyasiani and Wang (Citation2012) admit that, while commercial banks’ non-traditional revenue is increasing, the risks associated with these operations are increasing. Supporting evidence also comes from Australia (Williams, Citation2016; Williams & Prather, Citation2010), China (Calmès & Théoret, Citation2010; C. Y. Wang & Lin, Citation2018; Zhou, Citation2014) and Indonesia (Hafidiyah & Trinugroho, Citation2016).

From the above studies, it is clear that most of the studies on the relationship between income diversification and bank default risk are analyzed in the context of developed economies (United States, Germany, EU, Italy) or in the large-scale developing economies (China and India). Various studies consider the effect of diversification on bank risk in Vietnam and the results are different. Income diversification adds to risk (Batten & Vo, Citation2016; Vinh & Mai, Citation2015) due to alternate sources of funding hampered by undeveloped financial markets. On the other hand, Pham and Pham (Citation2020) argue that the diversification of commercial banks is not significantly related to bank risk, another finding of Pham et al. (Citation2021) supports the concept of economies of scope that claims diversified banks utilize redundant resources and customer base in a crisis period when banks’ lending activities were seriously affected and resulted in increased non-performing loans and liquidity risks. With the panel data sample from 29 Vietnamese banks in period 2005–2019, we emphasized that diversifying income is the most effective strategy during the crisis as the profit-saving solution without any potential risk. Conducting this theme in the context of Vietnam during a breakthroug of COVID-19 and any banks and financial institutions are influenced is very important.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Sample and data

We study the impact of income diversity on bank default risk in 29 Vietnamese commercial banks using a dynamic panel data model throughout 2012–2020. Negative-equity banks should be removed since they make calculating the Z-score harder. Consequently, this study obtained a sample of 29 banks from 2012 to 2020 resulting in 261 observations.

Data on bank-level variables are collected directly by the research team from financial statements of commercial banks. The macro data are collected from the official reports on General Statistical Office and State Bank of Vietnam’s official websites in period 2012–2020.

3.2. Research model and hypotheses

3.2.1. Model and variables

This paper employs popular estimate methods in panel data regression, such as OLS, FEM, and REM. Using several estimation techniques for panel data allows us to improve the certainty of the results.

The multivariate econometric model used in this paper considers the risk and risk-adjusted return variables as a function of the revenue diversification variables (Lepetit et al., Citation2008; Stiroh & Rumble, Citation2006). Estimates were calculated using Stata 14.0 software, and the econometric model is as follows:

Where i denotes banks and, t denotes time, εit denotes the remainder disturbance i = 1, 2, 3 … n; t = 1,2, …, T

3.2.2. Income diversification measure

According to Stiroh and Rumble (Citation2006), we consider the diversification index as follows:

NII is Net Interest Income; NOI is Net Operating Income; NON is Non-Interest Income.

Going deeper, we divide the non-interest revenues further to determine which source of non-interest income affects performance and risk.

Fee income includes items such as payment fees, bancassurance services, guarantee services, etc. Regarding activities in the financial market, income from the trading of foreign currencies and securities is also a non-interest source of income. The remaining includes income from capital contribution, share purchase, liquidation of fixed assets, or recoveries of bad debts previously written off.

NON1 is the rate of entry from foreign exchange trading and securities purchases, calculated as the ratio of Trading income (TRD) to Net Operating Income (NOI).

Similarly, NON2 is the proportion of income from fees and commissions, measured by Fee income (FEE) and Net Operating Income (NOI).

Finally, the Other Income Ratio is the meaning of NON3.

3.2.3. Measuring bank risk

According to previous studies, typically the research of Stiroh and Rumble (Citation2006) and Bharath and Shumway (Citation2008); the following formula is used to determine the Z-Score:

ROA is the return on assets, equity/asset is the shareholders’ equity divided by total assets and SDROA is the standard deviation of the return on assets, Following Chiorazzo et al. (Citation2008), we define it as the ratio of ROA for a given year to the standard deviation of ROA throughout the study, 2012–2020.

Because the Z-Score is often considered to be extremely biased in literature (Laeven & Levine, Citation2009) so we applied its natural logarithm transformation in all empirical calculations.

In addition, according to the research of Lepetit et al. (Citation2008); Fu et al. (Citation2014); two risk measures are calculated as follows:

RAROA and RAROE mean risk-adjusted ROA and risk-adjusted ROE, respectively; In these two ratios, the higher the value, the lower the levels of bank risk.

3.2.4. Control variables (bank characteristics, macroeconomic conditions)

Furthermore, we incorporate a set of factors in regression to account for characteristics that potentially affect bank risk-taking and performance. We select these variables based on existing literature on bank diversification (DeYoung & Rice, Citation2004; DeYoung & Roland, Citation2001; Edirisuriya et al., Citation2015; Laeven & Levine, Citation2007; Lee et al., Citation2014; Meslier et al., Citation2014; Sanya & Wolfe, Citation2011; Sissy et al., Citation2017; Stiroh & Rumble, Citation2006) the ratio of equity to total assets (ETA) control for bank capitalization; the natural logarithm of bank total assets (SIZE), Bank Growth is the growth rate of total assets (GROWTH), the ratio of the bank’s net interest income to its interest-bearing assets (NIM) measures the profitability in lending and investing activities of a commercial bank and finally the ratio of deposits to total assets (DA).

Meanwhile, macroeconomic conditions include the rate of real GDP growth (GDP) measures the developing level of an economy, which will lead banks to generate more profit, and this is also likely to reduce stability risks.

3.2.5. COVID variables

Our research adds variables relevant to the COVID-19 epidemic’s impact. In which the CVD dummy variable was used to distinguish the year COVID-19 happened throughout the research period. Furthermore, we use the CVD *DIV variable to see if the influence of diversification on bank risk has altered since before the pandemic.

3.2.6. Hypotheses

We estimate models to investigate how income diversity affects a bank’s default risk. Specifically, we test the following hypotheses:

H1: Income diversification reduces default risk and increases risk-adjusted earnings of banks

H2: The COVID-19 epidemic influences the relationship between income diversification and bank default risk

The features of explanatory factors, as well as the predicted sign of each variable for the risk indexes, are listed below.

To measure the relationship between the bank’s default risk and the above with the independent variables, we use panel data analysis with different estimation models such as the pooled estimation model (Pooled OLS), fixed effects model (FEM), and random effects model (REM). Next, tests in turn are carried out to select the appropriate estimation model. After that, the author tests the defects of the selected model and uses the FGLS estimation model to overcome the phenomenon of heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation. The tests are done in the article: F-test allows us to choose between a fixed-effects model and Pooled OLS model; Hausman test allows us to choose between the model according to FEM and REM; Breusch—Pagan Lagrangian test and Wald test used to test the heteroskedasticity phenomenon; Wooldridge test used to test the autocorrelation phenomenon.

4. Overview of Vietnamese bank’s income diversification and default risk

In the period from 2009 to 2020, the Vietnamese commercial banks have experienced various fluctuations. Along with the implementation of business activities, in this period, Vietnamese commercial banks also face many potential risks (see , below).

From 2009 to 2020, the bad debt ratio was relatively volatile. Since 2009, the bad debt ratio has tended to increase, and especially, the period 2011–2014 has witnessed an explosion of bad debt and bad debt ratio at Vietnamese commercial banks. During this period, the bad debt ratio increased above the minimum level recommended by the State Bank of 3%, specifically 3.30% in 2011, and peaked in 2012 at 4.02%. This is a threat to the operation of the banking system. The high rate of bad debt led to a sharp increase in the cost of credit risk handling. The high provisioning cost also reflects the increased level of credit risk during this period. This resulted in a sharp decline in the profitability and business performance of commercial banks.

From 2014–2015, with the strong efforts of the Government and the State Bank of Vietnam, many measures to deal with bad debts were implemented such as the establishment of Asset Management Company (VAMC) according to Decree No. 53/2013/NĐ-CP, limiting credit growth, restructuring debts, the bad debt ratio in Vietnam has improved significantly, falling below the threshold of 3% since the end of 2014 and continuously decreasing. Phong and Duyen (Citation2020) also confirmed that Vietnamese commercial banks face with several challenges for improving its efficiency and effectiveness, such as increasing bank size, enhancing labor productivity, reducing non-performing loans, control of competition and inflation.

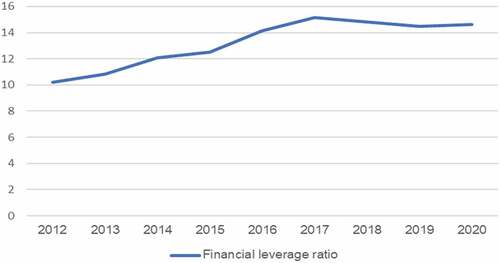

shows that the financial leverage of Vietnamese commercial banks is all at a high threshold, around 14, meaning that 1 currency is financed by 14 debt currencies while this threshold is at commercial banks in the world usually between 8 and 10 (Adrian & Brunnermeier, Citation2016). Maintaining a high debt-to-equity ratio shows the vulnerability of Vietnam’s financial system. This leads to possible financial risks of the system.

According to Pham (Citation2020), higher bank income without correspondingly higher soundness of stability can harm growth in the short term and more in the long run due to the potential for suspicious loans. Therefore, diversifying the bank’s income sources to minimize risks for the bank is an essential issue. In the Decision No. 986/QD-TTG in 2018 on development strategies of the banking industry, there are some points relating to income diversification, i.e., gradual transformation of banks’ business models in the direction of reducing dependence on credit activities and increasing income from non-credit services. The commercial banking system in Vietnam is increasingly developing, so it is expected that in the current context, the strategy of diversifying revenue sources can reduce risks for banks.

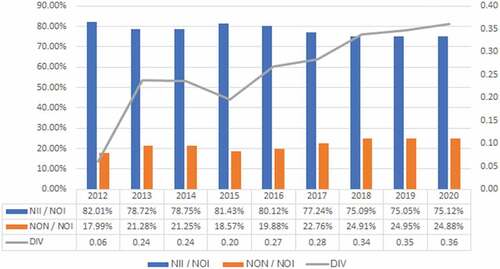

During the 9 years, Interest income still accounted for 75%—82% of total income, reflecting that commercial banks’ profits are still heavily dependent on interest income sources. Non-interest income only accounts for a low percentage, does not exceed 25%, and fluctuates unstable over the years. In general, non-interest income trends to increase in the period from 2012 to 2020 and trends to decrease in 2014–2015.

shows the level of diversification of commercial banks through the DIV index. The diversification index of banks has many fluctuations and does not follow certain trends, however, over the whole 9 years, this index in 29 banks tends to increase.

Most banks currently have strategies to diversify their income from services, reduce the burden of credit collection, and create a reasonable ratio between credit and non-credit. In the context of banks failing to satisfy Basel II standards (Basel II is the second edition of the Basel Accords, which sets forth broad principles and banking rules of the Basel Committee on banking supervision), increasing revenue from non-traditional operations is the right trend.

The Basel II Capital Accord is portrayed as a set of planned requirements that may provide a variety of compliance issues for banks all around the world. Because banks must compute the increase in equity to receive interest on lending activities, they must calculate the rise in equity. Furthermore, this strategy helps to reduce risks, laying the groundwork for long-term profit development.

Despite the effect of the COVID-19 outbreak, Vietnam’s banking system has lately witnessed tremendous development. Banks have diversified their sources of income to reach growth numbers during the pandemic, reducing reliance on the interest income from lending activities, increasing non-interest income through cards, insurance, bond issuance, or any other financial services.

5. Results and discussion

5.1. Descriptive statistics

Some general information and how to measure variables are presented in and , below:

Table 1. Some characteristics of determinants of income diversification and bank risk

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of variables

presents the mean, median, maximum and minimum values for each of the 15 variables: the bank’s risk measures, income diversification, and the proportion of non-interest income components to total operating income variables, and control variables.

The average risk of defaulting on the Z-score variable is 3.38 (minimum 1.37 and maximum 6.64) with a standard deviation of about 0.92. This index represents the differentiation of stability of different banks. RAROA is the risk of the return on assets that had an average value of approximately 2.00; RAROE is the risk of the return on equity, which had an average value of 2.05. The range of these two variables is similar, from −2.61 to 6.81. Their standard deviation is also quite large, 1.47 and 1.43 respectively. Therefore, the banks in our sample have the values of the risk-adjusted return variables quite dispersed while low standard deviation among the Z-score variable indicates it is not significantly varied.

The diversification variable is in the range of—3.72 to 0.50, with a standard deviation of 0.31. This suggests that income diversification varies significantly amongst banks. In addition, its average value is 0.26, which is consistent with the current situation, in which banks are increasingly paying more attention to diversifying their revenue sources. The lowest level is—3.72 because interest income or non-interest income is negative, which makes the NON/NOI or NII/NOI ratio greater than 1.

In general, interest income remains to be the bank’s main source of revenue. On average, the ratio of fees, trading, and other income to total operating income is about 20%, in which income from services has minor variation. In addition, income from other activities accounts for the largest proportion of non-interest income sources, however, there are substantial differences amongst banks.

As shown in the correlation matrix for the variables in , almost no combination of variables showed a correlation above 0.80, which indicates that there is no collinearity problem in this sample, except for the variable CVD*DIV, which shows a significant correlation with the variables GDP and CVD. However, when we test VIF, the result is mean VIF of 5.53, therefore we infer that multicollinearity does not occur.

Table 3. Correlation matrix

5.2. Discussions

Among three methods for panel data Pooled OLS, FEM, REM, the choice of most relevant method for this study is carried by F-test and Hausman test results.

Firstly, F-test tests 2 models Pool OLS and FEM. Pooled OLS estimates may not reflect the differential impact of each bank. That impact can be governance capacity, banking technology, human resources, risk management system, branch network, financial capacity, etc. So, we test for the existence of a fixed effect. The F-test is used to check for the presence of a fixed effect in each bank. The results show that the FEM model is more appropriate (Prob>F = 0.0000)

The second test reflects which should be chosen between FEM and REM.

Hausman’s test shows that the FEM is more suitable than the REMin studying the impact of income diversification on the Z-score and risk-adjusted ROA, while the REM is more suitable for the risk-adjusted ROE (see ).

Table 4. The result of Hausman test

However, the findings demonstrate that the model with variables RAROA and RAROE exhibits autocorrelation and heteroskedasticity errors when we re-test the model’s faults. Our Wooldridge test (Wooldridge, Citation2002) suggests that autocorrelation occurs (see ).

Table 5. The result of the Wooldridge test—dependent variables of RAROA, RAROE

We also use the Wald test and the Breusch and Pagan Lagrangian test to check the heteroskedasticity. The results suggest that the error exists in these two models (see ).

Table 6. The result of wald test—dependent variable of RAROA

The R-squared of model (1) showed that the regression model is acceptable in explaining the impact of income diversification on bank risk. Model (1) has the greatest number of significant variables (10 out of 12). There are 7 significant variables in model (2) and the least number of significant variables is 5, illustrated in model (3). Diversification index, another income rate, bank size, and net interest margin are significant among 3 models. The rest variable can explain at least in a model. The SIZE variable has a negative sign in model (1), which means Z-score will decline as the bank’s size increases, indicating a higher risk level. However, the relationships between SIZE and risk-adjusted return in models (2) and (3) positive are positive (see and ).

Table 7. The result of breusch and pagan Lagrangian test—the dependent variable is RAROE

Table 8. Regression results

Table 9. Regression results after removing variables

Variables NON1 and CVD*DIV are not statistically significant in all 3 models. Although NON1 has a positive effect on Z-score, it has not reached statistical significance, which means that the impact of the proportion of income from foreign exchange and gold and securities trading activities on bank risk cannot be confirmed. One reason given is that the impact on the risk of variable NON1 depends on the safety and liquidity of foreign exchange or securities held by the bank. Besides, the variable CVD * DIV is not statistically significant, which means that there is no evidence to evaluate the effect of income diversification on bank risk in the context of COVID-19. As a result, our hypothesis 2 remains unconfirmed. We believe that more observations are needed during and after the pandemic to have more reliable conclusions for this hypothesis.

CVD variable is only statistically significant in model (1). It can be concluded that COVID-19 reduces bank risk because the variable CVD positively affects the variable Z-score with a significance level of 10%, while its effect on the risk-adjusted return of banks has not been confirmed. This may be because the number of COVID years we can observe at this time is not enough to consider the change in indicators related to bank profitability.

DA variable is significant in 2 asterisks level in the model (1), whereas its impact on risk-adjusted returns in modes (2) and (3) is insignificant. The GDP growth rate variable was statistically significant at 5% in the model with the dependent variable Z-score and the risk-adjusted return on equity, however, there was no significant impact on the return on risk-adjustment return on asset.

In addition, in model (3), which has the fewest statistically significant variables, the variables fee income, equity on assets, and asset growth rate do not affect risk-adjusted return on equity.In , we continue to estimate the same models with dependent variables Z-score, RAROA, and RAROE after eliminating non-significant independent factors.

Therefore, we use the Feasible Generalized Least Square (FGLS) to reduce these phenomena.

The diversity index is positively connected with Z-Score and RAROA and RAROE, which means that income diversification leads banks to be more stable. Surprisingly, this result is inconsistent with some earlier findings in Vietnam (Vo, 2015; Batten & Vo, Citation2016) while agreeing with other research in Italy (Chiorazzo et al., Citation2008), US (DeYoung & Torna, Citation2013), India (Pennathur et al., Citation2012), and emerging Asia Pacific economies (C. Wang & Lin, Citation2021). The coefficients of DIV in 3 models (4) (5) and (6) all have statistical significance at 1%, equivalent to 99% confidence. Therefore, we can conclude hypothesis H1: when banks increase income diversification, bankruptcy risk will be reduced. In Vietnam, the current competition comes not only from domestic banks but also from foreign banks, forcing them to actively shift from focusing on traditional activities to diversifying to expand the market. Furthermore, credit activities come with many risks that can affect a company’s performance. In the financial market and economy’s current state of development, businesses increasingly have more channels to mobilize capital than bank credit. Therefore, besides improving credit quality, banks need to make effective use of portfolio diversification.

Fee-based income impacts negatively on bank risk with statistical significance at 1% in models (4) and (5). This result is contrary to our initial expectation that as the service business of banks grows, the risk of bankruptcy will gradually decrease. Because the basis of this revenue is fees and commissions, the bank’s service activities should be less risky and contribute to the bank’s revenue stability. One reason for this is that clients tend to choose banks that do not charge transaction fees. For banks, low transaction costs will be accompanied by a high CASA ratio, allowing them to deploy capital at a cheap cost, boost NIM (net interest margin), and decrease bank risk. On the other hand, insurance is one of the businesses that bring in fee income for banks. However, there is still a possibility that the second-year cancellation rate will be significant. Furthermore, the high amount of revenue allocated to banks puts pressure on insurance businesses, perhaps resulting in a reduction in the charge that the insurance company shares with the banks. It is increasingly promoted because of large profits, but it is not steady, which might lead to increased risk when banks raise fee income. However, this result is consistent with Kohler (Citation2014). He explained that while a higher share of fee income allows retail-oriented banks to improve risk diversification and become more stable (in the sense of having a higher Z-score), investment-oriented banks will become riskier. In contrast to retail-oriented banks, they are already heavily dependent on fee income and might over diversify if they increase their fee income share further.

The proportion of non-interest income comes from other sources, such as income from other derivatives, recoveries of bad debts previously written off or income from capital contribution, share purchase, has a significant impact on risk reduction with 1% significance level in 3 models (4) (5) and (6). Other income mainly consists of income from bad debts which have been dealt with by provision. Therefore, this rise in income shows that banks recover bad debts so as not to reduce profits, improve credit quality and reduce default risk. Research by Hafidiyah and Trinugroho (Citation2016) also agrees with this result.

The COVID-19 epidemic reduces the risk of default for banks. This is shown in model (4) at the 1% significance level. Besides certain problems during the COVID-19 pandemic, it has brought many new opportunities for the banking system. For example, banks may see this as an opportunity to accelerate their digital transformation, restructure their organization, and diversify their commercial operations to enhance revenues. In general, credit activity grew slowly due to prudence when lending due to the high risks in the current economy. Interest income may be affected, but this is unlikely to be a major issue given the growth in non-interest income and lower operational expenses. Therefore, the COVID-19 outbreak did not enhance the probability of bank default but rather showed signals of reduced risk during this time. However, hypothesis 2 has not been confirmed because we have omitted the CVD*DIV variable in the models with all 3 dependent variables. After all, this variable has not achieved the required reliability. This is a suggestion for future research that more time is needed to analyze the impact of income diversification on banking risk during the COVID period.

The Equity-to-asset ratio has the opposite and greatest impact on bank risk in model (1), with a coefficient of 8,836 at 1% significance level. The positive effect of this variable on risk-adjusted ROA is also significant. This effect means that if the equity in the total assets structure is high, banks can avoid the risk of bankruptcy. This is consistent with the Basel Committee’s studies and recommendations. Basel’s capital adequacy standards suggest that banks should focus on improving the ratio of equity to total assets. This issue is also regulated by the State Bank of Vietnam in legal documents to avoid risks to the banking system. This effect is in line with the result of Batten and Vo (Citation2016). They support the view that bank capital adequacy is an important element of prudential analysis, and a higher capital requirement will result in a more stable financial system. More importantly, maintaining a higher level of equity will act as a buffer to prevent banks from falling back on the government to mitigate their losses and discourage banks from taking irresponsible risks.

The larger the bank size, the higher the risk-adjusted return of the bank. A regression model with dependent variable Z-score (1) shows that bank size has a positive effect on risk with 90% confidence. However, after removing a few variables, bank size has no significant effect on the Z-score. Therefore, banks with small asset sizes may not necessarily have greater risks than large banks, because this depends on many factors such as governance capacity, credit quality, or strategy diversification of each bank. Large bank size will only reduce the risk of ROA and ROE fluctuations.

The ratio of deposits to total assets is negatively related to the bank’s risk, as shown in model (4). This is contrary to our initial expectations. This may be because banks are competing to mobilize deposits from the public with many preferential policies in search of cheap and low-cost capital. At the same time, credit and other business activities experienced many fluctuations, requiring a large provision for risks that caused a decrease in assets on the bank’s balance sheet.

The results of our other control variables all have a positive effect on the dependent variables. The asset growth rate has a positive effect on bank risk reduction. However, this contribution is quite small (the coefficients in the model (4), (5) are 0.126 and 0.826 respectively). Banks that maintain good asset growth annually contribute to reducing default risk. Net interest margin has a negative effect on risk and significantly changes the bank’s risk in all 3 models. The more the bank increases interest revenue while minimizing interest expenses, the more stable and efficient its operations will be. GDP growth rate has a positive effect on the bank’s stability index in the model (4). The developed economy, along with the growth of the financial market and the policies of the Government and the State Bank of Vietnam has created opportunities for banks to operate effectively and minimize macro risks.

In addition, in this study what appears more important for bank risk is the equity to asset ratio and net interest margin. Meanwhile, the risk reduction impact of income diversification strategy and bank size is quite small. This is because the relationship between bank size and risk depends on many internal factors of the bank and income restructuring strategies cannot be effective significantly in a short period; rather, they will gradually reveal their function in preserving bank stability.

6. Conclusions and suggestions

In this paper, we aim to assess the impact of non-interest income and the proportion of non-interest income components in total operating income on risk in 29 banks in Vietnam for the period between 2012 and 2020. The findings provide an updated analysis of the recent financial activities of Vietnamese commercial banks, which advocate for the positive effects of income diversification on bank risk. When implementing the income diversification strategy, the bank will limit the risks from credit activities. Furthermore, banks can achieve lower risk returns because they can gather more valuable information and save costs thanks to existing traditional operations thereby taking advantage of economies of scale.

In addition, the impact of a variety of other factors on bank risk was investigated, including equity-to-asset ratio, bank size, asset growth rate, deposit-to-asset ratio, net interest margin, GDP growth rate, and effect of COVID-19 epidemic. Accordingly, banking risk decreased during the epidemic period due to the appropriate policies of the State and the operation strategy of the banking industry to adapt to the new circumstances.

Based on the findings, some recommendations are proposed as below:

6.1. Recommendation for banks

The positive relationship between income diversification and the level of default risk implies that banks need to pursue diversification strategies. Commercial banks need to analyze the market, capture and call for market demand to expand appropriate products and services.

For fee-based activities and services, especially payment activities, it is vital to maintain a stable income ratio and to retain and increase customers using traditional and other non-traditional services.

The results reveal that the coefficients for securities trading and exchange activities variables are positive. It suggests that banks should be involved in those activities but to a limited extent, which is highly dependent on market fluctuation and government policies.

Enhance the efficiency of bank subsidiaries: establish a separate department at commercial banks with the necessary expertise and functions for investment; build an effective investment portfolio; risk management in investment; comply with the law on investment activities at the bank.

Digital transformation: building a modern banking service that is responsive to this consumer demand, one that is accessible, relevant, and valuable to customers.

Besides, other determinants such as the ratio of equity to total assets, the growth rate of total assets, net interest margin also affect the bank’s default risk. Therefore, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, to reduce risks, banks also need to identify leverage to reduce capital waste without having to change their business models.

6.1.1. Recommendation for policymakers

Policymakers are important parts to support diversification and lower bank risk at either the national or international level. All statistically significant independent variables in the models are all from macro levels, which are strongly influenced by policymakers.

To reduce the level of bank risk effectively, policymakers should create an enabling environment to promote the development and dynamism of a healthy financial market with the active participation of domestic and international investors; control inflation stably; stabilize and develop the financial system.

Improve institutions and laws to facilitate banking business with the issuance of specific regulations and guidelines on new banking services such as financial advisory services, management assets, products and services of the bank on the derivatives market, stock market, etc.

The State Bank of Vietnam innovate and improve efficiency in the control and inspection of banks, give early warning to potential systemic risks and prevent the risk of violating banking laws, detect and handle strictly violations and risks causing instability.

However, due to limited data sources, this study only focuses on 29 commercial banks but cannot cover the entire system of commercial banks in Vietnam. Joint-venture banks and foreign bank branches were not included in the study, and banks that did not have sufficient data when sampling were also excluded.

The study removes the factors related to the specific information of the bank’s management that affect the bank’s risk to determine the optimal model, such as experience, management skills, or independence in banking operations and management. For several reasons we think that our results are not severely biased by endogeneity. However, future research on this issue may consider using the GMM model to effectively overcome the endogeneity problem.

The relatively short duration of this study may be a limitation as it is not sufficient to accurately reflect the duration of the COVID-19 epidemic. We suggest that future research could explore the effect of bank diversification on risk over a longer period, including more pandemic and post-pandemic time periods to get a deeper insight. Besides, future studies should consider investigating more evidence on this research direction in other contexts for a novel approach on diversification policies in the banking sector.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Thanh Tam Le

Thanh Tam Le is the banking and finance lecturer and researcher. Her research interests include commercial banking, risk management in banking, financial inclusion, fintech, microfinance.

Quynh Anh Nguyen

Quynh Anh Nguyen is the banking and finance researcher. Her research interests covers banking management and operation, corporate financial management, risk management.

Thi Minh Ngoc Vu

Thi Minh Ngoc Vu is the banking and finance researcher. She is interested in topics of banking management and operation, corporate financial management, risk management.

Minh Phuong Do

Minh Phuong Do is the banking and finance researcher. Her research interests cover specific topics in commercial and development banking, corporate financial management, risk management.

Manh Dung Tran

Manh Dung Tran is a senior lecturer and researcher in the fields of finance and accounting. His research interests consist of fintech, financial inclusion, commercial banks, financial performance, and impairment.

References

- Abedifar, P., Molyneux, P., & Tarazi, A. (2018). Non-interest income and bank lending. Journal of Banking & Finance, 87, 411–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2017.11.003

- Acharya, V. V., Hasan, I., & Saunders, A. (2006). Should banks be diversified? Evidence from individual bank loan portfolios. Journal of Business, 79(3), 1355–1412. https://doi.org/10.1086/500679

- Acharya, V. V., & Steffen, S. (2013). Analyzing systemic risk of the European banking sector. Book chapter in Handbook on Systemic Risk. Cambridge University Press., 247–282.

- Adrian, T., & Brunnermeier, M. K. (2016). CoVaR. American Economic Review, 106(7), 1705–1741. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20120555

- Allen, F., & Santomero, A. (2001). What do financial intermediaries do? Journal of Banking and Finance, 25(2), 271–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4266(99)00129-6

- Baele, L., De Jonghe, O., & Vennet, R. V. (2007). Does the stock market value bank diversification? Journal of Banking and Finance, 31(7), 1999–2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2006.08.003

- Batten, J. A., & Vo, X. V. (2016). Bank risk shifting and diversification in an emerging market. Risk Management, 18(4), 217–235. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41283-016-0008-2

- Bharath, S., & Shumway, T. (2008). Forecasting Default with the Merton Distance to Default Model. Review of Financial Studies, 21(3), 1339–1369. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhn044

- Bühler, W., & Prokopczuk, M. (2010). Systemic risk: Is the banking sector special? SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1612683

- Calmès, C., & Liu, Y. (2009). Financial structure change and banking income: A Canada – U.S. comparison. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 19(1), 128–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2007.09.003

- Calmès, C., & Théoret, R. (2010). The impact of off-balance-sheet activities on banks returns: An application of the ARCH-M to Canadian data. Journal of Banking & Finance, Elsevier, 34(7), 1719–1728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2010.03.017

- Chiorazzo, V., Milani, C., & Salvini, F. (2008). Income diversification and bank performance: Evidence from Italian banks. Journal of Financial Services Research, 33(3), 181–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-008-0029-4

- Cornett, M. M., Ors, E., & Tehranian, H. (2002). Bank performance around the introduction of a section 20 subsidiary. Journal of Finance, 57(1), 501–521. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6261.00430

- Curi, C., Lozano-Vivas, A., & Zelenyuk, V. (2015). Foreign bank diversification and efficiency prior to and during the financial crisis: Does one business model fit all? Journal of Banking & Finance, 61(1), 22–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2015.04.019

- DeYoung, R., & Rice, T. (2004). Noninterest income performance at U.S. banks. The Financial Review, 39(1), 101–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0732-8516.2004.00069.x

- DeYoung, R., & Roland, K. P. (2001). Product mix and earnings volatility at commercial banks: Evidence from a degree of total leverage model. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 10(1), 54–84. https://doi.org/10.1006/jfin.2000.0305

- DeYoung, R., & Torna, G. (2013). Nontraditional banking activities and bank failures during the financial crisis. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 22(3), 397–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2013.01.001

- Doumpos, M., Gaganis, C., & Pasiouras, F. (2016). Bank diversification and overall financial strength: International evidence. Financial Markets, Institutions & Instruments, 25(3), 169–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/fmii.12069

- Edirisuriya, P., Gunasekarage, A., & Dempsey, M. (2015). Bank diversification, performance and stock market response: Evidence from listed public banks in South Asian countries. Journal of Asian Economics, 41, 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2015.09.003

- Elsas, R., Hackethal, A., & Holzha¨ User, M. (2010). The anatomy of bank diversification. Journal of Banking & Finance, 34(6), 1274–1287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2009.11.024

- Elyasiani, E., & Wang, Y. (2012). Bank holding company diversification and production efficiency. Applied Financial Economics, 22(17), 1409–1428. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603107.2012.657351

- Fu, X. Q., Lin, Y. J., & Molyneux, P. (2014). Bank competition and financial stability in Asia Pacific. Journal of Banking and Finance, 38, 64–77 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.09.012.

- Grassa, R. (2016). Ownership structure, deposits structure, income structure and insolvency risk in GCC Islamic banks. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, 7(2), 93–111. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIABR-11-2013-0041

- Hafidiyah, M. N., & Trinugroho, I. (2016). Revenue diversification, performance and bank risk: Evidence from Indonesia. Jurnal Dinamika Manajemen, 7(2), 139–148. https://doi.org/10.15294/jdm.v7i2.8198

- Harris, M., Kriebel, C., & Raviv, A. (1992). Asymmetric information, incentives, and intrafirm resource allocation. Management Science, 28(6), 604–620. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.28.6.604

- Kim, H., Batten, J. A., & Ryu, D. (2020). Financial crisis, bank diversification, and financial stability: OECD countries. International Review of Economics & Finance, 65, 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2019.08.009

- Kohler, M. (2014). Does non-interest income make banks more risky? Retail- versus investment- oriented banks. Review of Financial Economics, 23(4), 182–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rfe.2014.08.001

- Laeven, L., & Levine, R. (2007). Is there a diversification discount in financial conglomerates? Journal of Financial Economics, 85(2), 331–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2005.06.001

- Laeven, L., & Levine, R. (2009). Bank governance, regulation and risk taking. Journal of Financial Economics, 93(2), 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.09.003

- Lee, C. C., Yang, S. J., & Chang, C. H. (2014). Non-interest income, profitability, and risk in banking industry: A cross-country analysis. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 27(C), 48–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.najef.2013.11.002

- Lepetit, L., Nys, E., Rous, P., & Tarazi, A. (2008). Bank income structure and risk: An empirical analysis of European banks. Journal of Banking and Finance, 32(8), 1452–1467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2007.12.002

- Lin, J. R., Chung, H., Hsieh, M. H., & Wu, S. (2012). The determinants of interest margins and their effect on bank diversification: Evidence from Asian banks. Journal of Financial Stability, 8(2), 96–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2011.08.001

- Lipczynski, J. (2005). Industrial Organization, second edition. Pearson Education. www.pearsoned.co.uk/lipczynski

- Markowitz, H. M. (1952). Portfolio selection. The Journal of Finance, 7(1), 77–91 https://doi.org/10.2307/2975974.

- Mercieca, S., Schaeck, K., & Wolfe, S. (2007). Small banks: Benefits from diversification? Journal of Banking & Finance, 31(7), 1975–1998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2007.01.004

- Meslier, C., Tacneng, R., & Tarazi, A. (2014). Is bank income diversification beneficial? Evidence from an emerging economy. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 31, 97–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2014.03.007

- Pennathur, A. K., Subrahmanyam, V., & Vishwasrao, S. (2012). Income diversification and risk: Does ownership matter? An empirical examination of Indian banks. Journal of Banking and Finance, 36(8), 2203–2215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2012.03.021

- Pham, M. P. (2020). Interdependence between banking earnings, banking security and growth achievement: Case study in the ASEAN community. Journal of Economics and Development, 22(2), 249–264. https://doi.org/10.1108/JED-01-2020-0003

- Pham, D. K., Ngo, V. M., Nguyen, H. H., & Le, T. L. V. (2021). Financial crisis and diversification strategies: The impact on bank risk and performance. Economics and Business Letters, 10(3), 249–261. https://doi.org/10.17811/ebl.10.3.2021.249-261

- Pham, Q. V., & Pham, T. Q. P. (2020). Diversification, market concentration and default risks of Vietnamese commercial banks. Journal of Finance, 1(5), 10–23.

- Phong, N. H., & Duyen, T. B. P. (2020). The cost efficiency of Vietnamese banks – The difference between DEA and SFA. Journal of Economics and Development, 22(2), 209–227. https://doi.org/10.1108/JED-12-2019-0075

- Saeed, M., & Izzeldin, M. (2016). Examining the relationship between default risk and efficiency in Islamic and conventional banks. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 132, 127–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2014.02.014

- Sanya, S., & Wolfe, S. (2011). Can banks in emerging economies benefit from revenue diversification? Journal of Financial Services Research, 40(1), 79–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-010-0098-z

- Sissy, A. M., Amidu, M., & Abor, J. Y. (2017). The effects of revenue diversification and banking on risk and return of banks in Africa. Research in International Business and Finance, 40, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2016.09.017

- Stiroh, K. J. (2004). Do community banks benefit from diversification? Journal of Financial Services Research, 25(2), 135–160. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:FINA.0000020657.59334.76

- Stiroh, K. J., & Rumble, A. (2006). The dark side of diversification: The case of US financial holding companies. Journal of Banking and Finance, 30(8), 2131–2161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2005.04.030

- Templeton, W. K., & Severiens, J. T. (1992). The effect of nonbank diversification on bank holding company risk. Quarterly Journal of Business and Economics, 31(4), 3–17.

- Vinh, V. X., & Mai, T. T. P. (2015). Profit and risks from income diversification of Vietnamese commercial banks. Journal of Economic Development, 26(8), 54–70.

- Vithessonthi, C. (2014). The effect of financial market development on bank risk: Evidence from Southeast Asian countries. International Review of Financial Analysis, 35, 249–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2014.10.005

- Vithessonthi, C., & Kumarasinghe, S. (2016). Financial development, international trade integration, and stock market integration: Evidence from Asia. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 35, 79–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mulfin.2016.03.001

- Wang, C. Y., & Lin, Y. J. (2018). The influence of income diversification on operating stability of the Chinese commercial banking industry. Journal of Economic Forecasting, 21(3), 29–41.

- Wang, C., & Lin, Y. (2021). Income diversification and bank risk in Asia Pacific. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 57, 101448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.najef.2021.101448

- Williams, B. (2016). The impact of non-interest income on bank risk in Australia. Journal of Banking and Finance, 73, 16–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2016.07.019

- Williams, B., & Prather, L. (2010). Bank risk and return: The impact of bank non-interest income. International Journal of Managerial Finance, 6(3), 220–244. https://doi.org/10.1108/17439131011056233

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. The MIT Press.

- Zhang, A. L., Wang, S. Y., Liu, B., & Fu, J. Y. (2020). The double-edged sword effect of diversified operation on pre-and post-loan risk in the government-led Chinese commercial banks. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 54, 101246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.najef.2020.101246

- Zhou, K. G. (2014). The effect of income diversification on bank risk: Evidence from China. Emerging Markets Finance Trade, 50(3), 201–213. https://doi.org/10.2753/REE1540-496X5003S312