Abstract

The world has been facing unprecedented challenges with various ethical issues within organisations, which is related to ethical leadership and decision making amongst other things. Subsequently, this paper is focused on the interrelationships between organisational culture, ethical organisational climate, ethical leadership, decision making and workplace pressures. The effect of these ethical related constructs on organisational citizenship behaviour, employee ethical behaviour, conduct, and perceived employee performance is further studied, from a macro-meso-micro perspective. This quantitative study used a cross-sectional design and survey strategy. The sample consisted of 526 participants of varying backgrounds working in “large” enterprises across diverse industries in Mauritius. The results of this study show that organisational culture and ethical organisation climate (as macro independent variables) jointly influence the dependent variables (organisational citizenship behaviour, employee ethical behaviour and conduct, and perceived employee performance) both directly and indirectly to varying degrees. It was also found that ethical leadership and decision making, and internal and external workplace pressures (as meso variables) have statistically significant mediating effects on organisational citizenship behaviour and perceived employee performance. The model proved to have a good fit and can be adopted as a guiding model for the business and research communities in fostering organisational citizenship behaviour. Lastly, recommendations were made to enhance the ethical and organisational citizenship behaviour within the corporate environment of Mauritius.

1. Introduction

Over the past century and more so in the recent decades, organisations have been facing numerous kinds of socio-economic challenges. With the ever-growing pressures from shareholders to maximise profits and keep value-creation high on the agenda, business leaders have had to strike the right balance between attaining shareholder’s goals and fulfilling their deontological duties (Ford, Citation2006; Knights & O’Leary, Citation2006). Over time, this phenomenon has even led executives to relegate critical duties of leadership at the expense of financial rewards. In a study conducted by the Institute of Leadership and Management and Management Today, it was found that 50% of respondents believed their organisations prioritised financial goals over ethics (The Institute of Leadership and Management, Citation2011). In another survey undertaken by the National Business Ethics Survey of Fortune 500 Employees, it was noted that job security came out as the top source of internal pressure, and meeting targets as the top source of external pressure influencing employees to compromise ethical standards (Ethics Resource Centre, Citation2012a). This trend has even been exacerbated in recent years on the global front with employees experiencing an increased level of pressure to compromise standards as well as witnessing growing misconduct in the workplace, and facing increased retaliation when they report wrongdoings (Ethics & Compliance Initiative, Citation2018).

The financial crisis of 2008, which was to a large extent caused by unethical behaviour brought down the U.S economy and economies around the world (Ciro, Citation2012). This was not the first or last occurrence of unethical behaviour within the corporate environment. Well document instances of unethical behaviour and corporate scandals include the Citigroup’s role in the collapse of WorldCom in 2002 (Wilmarth, Citation2013), Alibaba.com’s fraud by sellers in 2011 (Lee & Chao, Citation2011), Toshiba’s accounting and FIFA scandals (Boudreaux et al., Citation2016; Caplan et al., Citation2019), and more recently ethical issues in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic (Ernst & Young, Citation2020; Gaspar et al., Citation2020). All of these have put the spotlight on organisational ethics, ethical organisational culture and behaviour, and ethical organisational climate.

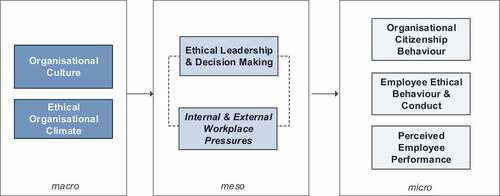

While researchers have established the linkages between ethics and leadership, there are nevertheless gaps that need to be bridged through further research (Black & Morrison, Citation2014; Toor & Ofori, Citation2009; Victor & Cullen, Citation1998). Examples would be exploring the dynamics of ethical climate in respect of various ethical climate types and possible influence in business (Sibiya et al., Citation2016). Further instances would include evaluating interrelationships and effects between ethics-related components within a conceptual macro-meso-micro framework (Li, Citation2012; Engelbrecht, Newman et al., Citation2017; Engelbrecht et al., Citation2017; Grobler & Joubert, Citation2020; Grobler & Grobler, Citation2021).

The purpose of this study was to determine the interrelationship and mediating effect of a set of organisational ethics variables, conceptualised in accordance with the macro-meso-micro framework, in a multi-cultural, multi-industry and “large” organisation context in Mauritius. The context is related to the unique economic, cultural, social and political characteristics which were not studied before. This paper aims to bridge the gap in assessing and presenting how ethical organisational culture and climate influence employees’ ethical behaviour and the mediating effects of ethical leadership and workplace pressure on organisational citizenship behaviour, using a macro-meso-micro framework within the corporate environment of Mauritius.

This research enabled to uncover key findings that will enlighten and empower organisations and practitioners in understanding the dynamics of ethical organisation climate and how the ethics-related variables within the model influence organisational citizenship behaviour, ethical behaviour and performance amongst employees.

2. Theoretical background

It is firstly important to provide a theoretical background of the constructs (variables) used in this study. The sequence of the discussion is in accordance with the macro-meso-micro framework to provide structure. A short discussion of organisational culture, ethical organisational climate, ethical leadership and decision making (macro variables), ethical leadership and decision making, internal and external workplace pressures (meso variables), organisational citizenship behaviour, ethical employee behaviour and conduct, and lastly perceived employee performance (macro variables) will follow.

Organisational Culture

Based on the philosophical work of Kant (Citation1790/1914), Harste (Citation1994, p. 5) provided the following definition of organisational culture: “Organisation culture is created when groups of human beings can, in spite of their differences, reflexively judge in a common, universalising way how the organisation can be differentiated from the demands of the environment”. The key contribution of the Kantian theory is that organisational culture is based on a trusted acceptance of differences, where employees share goals, self-organise and mobilise themselves as a collective unit intimately linked with the organisation to attain the set goals.

Robbins and Judge (Citation2013, p. 512) referred to organisational culture as a “system of shared meaning held by members that distinguishes the organisation from other organisations”. It can also be seen as a complex set of artefacts as a 3-tier structure (visible and tangible elements), adopted beliefs and values (values, ideologies, goals and aspirations) and basic underlying assumptions (subconscious or taken-for-granted beliefs and values; Schein & Schein, Citation2017). Furthermore, Schein and Schein (Citation2017) viewed organisational culture as a powerful but largely invisible social force.

Kotter and Heskett (Citation1992, p. 11) stated that their studies revealed that “corporate culture can have significant impact on the long term economic performance and will probably be an even more important factor in determining the success or failure of the firms in the next decade”. This confirms the critical role that organisational culture plays in the development and survival of enterprises and why it warrants further study in different contexts like in the multi-cultural context of Mauritius.

Ethical Organisational Climate

Research on organisational climate stems back to the days when Lewin et al. (Citation1939) studied different leadership styles to establish whether they are interrelated and whether specific leadership styles lead to distinct organisation climates (Lewin, Citation1951) . Initially Schneider and Reichers (Citation1983) presented these perceptions, as being rather descriptive (“the description of things that happen to employees in the organisation”). Subsequent studies however suggested both affective and evaluative perspectives (Patterson et al., Citation2004). Both the organisational culture and climate describe how employees experience their organisation. In other words, organisational climate can be conceptualised as the surface of the culture of the organisation (Schein, Citation1985; Schneider, Citation1990), comprising a character, personality and psychological atmosphere of an organisation’s internal work environment (Evan, Citation1968; Pritchard & Karasick, Citation1973).

Since major ethical failures and scandals, there has been a resurgence amongst scholars of studies of ethical organisational climate and leadership. For instance, the development of the Corporate Ethics Virtues Model by Kaptein (Citation2008a) and his subsequent studies brought further insights on how a set of eight ethics virtues is critical in shaping an ethical organisational climate. These strengthened the core base of ethical foundations, complementing the already established Victor and Cullen (Citation1988)’s Ethical Climate Model and Vidaver-Cohen (Citation1995)’s Moral Climate Continuum amongst others.

Ethical Leadership and Decision Making

Brown et al.’s (Citation2005, p. 120) defined ethical leadership as the “demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement and decision making”. Through this definition, which is also commonly referred amongst scholars and researchers, the importance of the leaders’ own conduct, how these are promoted within the organisation or society, and how people “read” and perceive their conduct are central to the understanding of ethical leadership. Constituents of ethical leadership consist of their role modelling in promoting ethical standards and practices. They reinforce this through their own stewardship, permeating the ethical culture through right actions, effective communication approaches, transparent decision making and inculcating these into others.

Lawton and Páez (Citation2015) presented virtues (the who), purposes (the why) and practices (the how) as three interlocking dimensions of ethical leadership. In other words, the interplay of these three dimensions can lead to different forms of ethical leadership. Ethical leaders are “individuals who are impartial and unbiased, exhibit ethical behaviours, take the wishes of people into notice and protect their employees’ rights fairly” (Zhu et al., Citation2004). Ethical outcomes often demand that the leader is virtuous (e.g., courageous, truthful, fair and honest), and engages others for a purpose (social or economic) through the execution of the right practices (e.g., ethical judgment and ethical decision making). The fundamental role that ethical leadership plays in the organisation and how it influences the behaviour of subordinates and employees in shaping the right ethical and organisation citizenship behaviour in the workplace becomes even more crucial in these challenging times characterised by the pandemic and socio-economic tensions. It is equally important to understand the dynamics of ethical leadership in a multi-cultural context such as Mauritius driven by its own unique socio-economic specificities with a view to get further insights on ethical practices at a leadership level across industries. It will also unveil commonalities and differences with other studies conducted in other parts of the world, enabling better understanding of the influence of ethical leadership on employee behaviour and performance in the local context.

Internal and External Workplace Pressures

Internal and external pressure factors are causing a shift in the way ethical behaviour evolves within organisations. Internal pressures would usually take the form of elements personal to the individual such as his own survival, job security, meeting his financial obligations and his career. External pressures usually come in the form of meeting business targets and goals, ensuring financial success of the organisation, value creation for the shareholders and the like. Business and competitive pressures, investors’ and shareholders’ demands, political pressure, authority supervision, social dynamics and pressures, scandals, globalisation and the pandemic are few examples of the external forces causing a radical change in behaviour thereby putting ethics at the centre of the debate. Similarly, forces such as work pressures towards meeting aggressive business targets and tight deadlines are also affecting the professional conduct of leaders. Kaptein (Citation2008a) calls this “The Virtue of Feasibility” whereby the setting of unrealisable targets tends to lead towards higher levels of unethical behaviour. Schweitzer et al. (Citation2004) discovered similar empirical findings.

Vidaver-Cohen (Citation1993) examined how anomie (lack of ethical standards) occurs in the workplace. One of the main causes of unethical behaviour in workplaces is the excessive pressure which management puts on goal attainment without a corresponding counterbalance for legitimate procedures. Vidaver-Cohen (Citation1993) backed his examination by Merton’s theory of social structure and anomie. Whilst the individual’s moral character was often considered as a key determinant of ethical conduct, it was found that the work environment plays an equally influential role on the behaviour of employees. Since its initial conceptualisation stages in 1938, Merton’s model gradually evolved to become one of the most important frameworks for explaining criminal conduct in societies (Merton, Citation1964). Merton identified and put forward some key issues worth considering for the understanding of organisational anomie:

High rates of unethical practices, anti-social behaviour and illegal conduct occur as a result of inordinately strong emphasis placed on achieving goals and targets without corresponding emphasis on adhering to legitimate procedures helping to attain such goals.

A discrepancy between the “means and ends” or a social disequilibrium characterised by non-adherence and ineffectiveness of conduct-governing rules causes anomie.

Do such workplace pressures as examined by Vidaver-Cohen (Citation1993) and Kaptein (Citation2008a) have similar counter effects in context such as Mauritius characterised by its diversities in culture and the general quests of businesses to outperform for the benefit of their stakeholders? Such questions call for empirical and critical evaluations to gauge the nature of such workplace pressures and their likely impact on employees’ behaviour and performance.

Organisational Citizenship Behaviour

In a context characterised by a relentless quest and pressure for economic survival and growth, the sustainability of organisational performance and value creation imperatives start dictating the agenda and priorities of business leaders. It further demands for a more conducive and engaging work environment that can stimulate employees’ commitment and delivery levels beyond their usual call of duty. Huhtala et al. (Citation2011) posit that employees’ emotional engagement and work commitment are higher in a work environment characterised by ethical standards, systems and practices. All this draws one’s attention on the inherent role and importance of organisational citizenship behaviour in the context of this study.

Smith et al. (Citation1983), Organ and Konovsky (Citation1989), and Alizadeh et al. (Citation2012) shed light on the concept of organisational citizenship behaviour with the aim of fostering a positive working environment that influences employees to surpass the minimum role requirements expected from the incumbents.

Organisational citizenship behaviour can be considered as a set of behaviours in which employees act and perform beyond their prescribed duties and engage in improving the individual’s or company behaviour (Bateman & Organ, Citation1983). The underlying philosophy of organisational citizenship behaviour is driven by the fact that employees’ delivery levels go beyond their official contractual requirements, job descriptions and their commitment to go the extra mile for the organisation’s welfare out of loyalty for their bosses and the company at large. This is often the result of voluntary compassion for and reciprocity towards their leaders in exchange for the fair treatment and welfare they obtain. As Konovsky and Pugh (Citation1994) highlighted, organisational citizenship behaviour occurs in an environment characterised by social exchange and quality of superior-subordinate relationships. Gouldner (Citation1960) referred to employees’ feelings of obligation to pay back what they benefited from their employers.

The findings confirmed a positive relationship between ethical leadership and organisational citizenship which is sequentially mediated by perceived procedural justice and employees’ organisational concerns (Mo & Shi, Citation2017). Employees generally feel indebted to their leaders if they are being looked after and treated well which results in the employees reciprocating accordingly in supporting their leaders to attain the bigger organisational objectives (Mayer et al., Citation2009; Rioux & Penner, Citation2001). It would be enlightening to determine whether such pattern manifests itself in the local business context of Mauritius where attainment of business goals and value creation are high on the agenda.

Ethical Employee Behaviour and Conduct

Central to the study of ethical organisational climate and culture lies the examination of employee moral behaviour and conduct. Ethical employee behaviour and conduct refers to such actions that most people would reasonably judge as being morally correct and expect to see them prevailing in an organisation. Maesschalck (Citation2004) explained it by taking examples of what would constitute “unethical behaviour” benchmarking them against the nine ethical standards framed by Victor and Cullen (Citation1988). According to Maesschalck (Citation2004), the unethical conduct would be characterised by a manifestation of selfishness (e.g., personal gain or corruption), organisational-fetishism (e.g., resorting to improper means to protect organisational interests at all costs such as window dressing of accounts), efficiency-fetishism (e.g., where one would bend the rules to maximise efficiency for profitability), nepotism (e.g., granting unlawful preferential treatment to relatives and friends), team-fetishism (e.g., hiding of improper practices by people in a group due to their loyalty), partiality (e.g., improper preferential treatment to stakeholders), anarchy, rule- and law-fetishism characterised by a complete non-compliance to rules, law and policies at a personal, organisational level and beyond. Given limited study in this area locally, determining the main motives for ethical deviations become imperative in the overall quest to address ethical issues within organisations. Gauging and understanding the effects of the macro and meso variables on this particular variable are thus vital in determining the type of leadership actions needed to transform and nurture the right ethical conduct, practices and culture in the organisation.

Perceived Employee Performance

The interplay of the macro and meso variables under study and their resulting effects on perceived employee performance is another dimension needing study and diligent examination. Perceived employee performance refers to the way the employees perceive their organisation to be performing on various fronts, whether being the way it manages its corporate image, the competitiveness of its products and services, its ability to grow the client base, attract and retain top talents, the prevailing culture and ethical climate, and the conduct of their leaders in creating a fair, motivating, performing and rewarding work environment. These factors, including the progressive human resources practices, are regarded as key enablers in enhancing performance of employees in an organisation (Delaney & Huselid, Citation1996).

The Mauritian Context

As has been the case globally, Mauritius has also witnessed numerous cases of ethical issues whether on the business, social and political fronts. Whilst a series of legal, regulatory and governance framework and codes exist, the media has nevertheless reported several issues pertaining to influence of power, corruption, nepotism, frauds, corporate failures, pressures, lobbies and economic cartels. This has also been reported by some noteworthy empirical studies in Mauritius covering ethical decision making (Napal, Citation2005), ethics in journalism (Chan-Meetoo, Citation2013), ethical leadership (Ah-Kion & Bhowon, Citation2017; Ah-Teck & Hung, Citation2014) and assessment of corporate governance practices (Padachi et al., Citation2016).

Based on the studies conducted by Napal (Citation2003) on ethical decision making amongst a sample of business executives, it was noted that personal ethics predominate in the making of ethical choices, regardless of the presence of a company code of conduct. Furthermore, it was also found that the behaviour of management was a critical influential factor of ethical conduct. For example, Chan-Meetoo (Citation2013) uncovered several ethical issues facing the profession of journalism in Mauritius. The study highlighted the key issues facing the profession such as pressures to publish fast with the accompanying dangers of transgressing accuracy and veracity of information, inclination towards sensationalism to boost sales of newspapers and revenues and substantial pressure to refrain from publishing delicate news on powerful politicians amongst others. Ah-Kion and Bhowon (Citation2017) studied the leadership approaches and ethical decision making processes of 247 managers working in three higher education institutions. It was found that transformational leadership had a negative impact on ethical judgment and intention of the subordinates in respect of ethical issues thereby suggesting the possibility of pseudo-transformational leadership or the influence of cultural factors.

Despite the existence of comprehensive legislation and systems to combat crime at large, illegal actions are still occurring in large numbers and are reported across the globe (OECD, Citation2016). Similarly, despite the establishment of governance and control systems, codes of conduct, and policies and procedures, organisations are still faced with ethical issues (Ethics & Compliance Initiative, Citation2018; Ethics Resource Centre, Citation2012a; PwC., Citation2016)

Furthermore, the review of current literature on organisational culture, ethical climate, ethical leadership and decision making, pressure factors, behavioural dynamics, employee performance, and the interrelationship of these components highlights the following key research problems:

The relationship between ethics and leadership has been studied by scholars for quite some time (Burns, Citation1979; Deconinck et al., Citation2016), yet the world continues to face major socio-economic challenges due to ethical issues (Huang & Paterson, Citation2017).

Theoretical models have yet to determine whether mediation effects between organisational ethics components within a conceptual macro-meso-micro framework remain constant across different contexts, organisations and groups of individuals (Grobler & Grobler, Citation2018).

The need to determine the interrelationships between organisational culture, ethical organisational climate, ethical leadership and decision making, internal and external workplace pressures, and their effects on organisational citizenship behaviour, employee ethical behaviour and conduct, and perceived employee performance in a cross-industry multi-cultural context.

A necessity for the development of a new or improved framework or model that would enable enhanced organisational citizenship behaviour, ethical business practices and performance in a dynamic context largely influenced by internal and external pressures compromising ethical standards.

A need to put forward appropriate recommendations for the business community with a view to further equipping them against ever-mounting ethical challenges and addressing such dilemmas in a context largely characterised by a plurality of cultures and socio-economic diversities.

Research has been conducted in different countries relevant to the current areas of interest. However, a study specifically orientated towards the assessment of organisational culture, ethical organisation climate, ethical leadership and decision making, workplace pressures, organisational citizenship, employee behaviour and performance, as an interconnected and collective unit, has not been yet been done in the multi-cultural and cross-industry context of Mauritius. Given the economic, cultural, social and political specificities of Mauritius, the study helps in enlightening key stakeholders about the interrelationships and dynamics of these variables in such a context and how they can be dealt with.

With a view to bridge these research gaps, it was vital to assess the nature of the relationship between the macro, meso and micro components, and subsequently assess interrelationships between the ethical context independent variables and ethical mediating variables and their effects on organisational citizenship behaviour, employee ethical behaviour and conduct, and perceived employee performance.

The conceptual research model underpinning the study, as per Figure , is as follows:

The specific research questions being responded to in this paper are as follows:

What is the statistical relationship between organisational culture and ethical organisation climate?

What is the statistical relationship between the mediating variables of ethical leadership and decision making, and internal and external workplace pressures?

What is the nature of the theoretical and observed interrelationships between the independent variables (organisational culture and ethical organisational climate) and the mediating variables (ethical leadership and decision making, and internal and external workplace pressures), and their effects on the dependent variables (organisational citizenship behaviour, employee ethical behaviour and conduct, and perceived employee performance)?

Is there a good fit between the elements of the empirically manifested structural model and the theoretically hypothesised model?

3. Research design & methodology

Considering the underlying constructs to be measured in a complex multi-cultural cross-industry context, quantitative method was used.

A survey strategy was adopted and deployed with a view to collect relevant quantitative data from a devised sample of participants from Mauritian corporates operating across industries.

A comprehensive and structured questionnaire was constructed using eight underlying well-established, reliable and valid scales to measure the constructs being studied. Slight adaptation was done to supplement certain scales where required to suit the scope and objectives of the study without adversely affecting their validity and reliability.

The master instrument measured the macro-meso-micro constructs within the Conceptual Research Model through a total of 232 items, as shown in Table , using a 5-point Likert-type scale response anchors for the constructs being measured.

Table 1. Structure of Master Instrument Used

The aim was to study “large” establishments in the multi-cultural and cross-industry environment of Mauritius. The latest available 2013 census conducted by Statistics Mauritius (the official government statistics body) covered 127,000 establishments, referred to as “production units”. Of these, 2,200 (2%) were classified as “large” establishments across various industries and were considered as the largest contributors to economic development of the country (Statistics Mauritius, Citation2017). They engage at least 10 persons within the respective enterprises.

The 2013 census did not provide a complete view as it did not cover “large” establishments in certain specific industries such as agricultural, forestry, fishing and others. It was thus further supplemented by another government survey undertaken in 2016, which provided a complete and more appropriate view of the population of “large” establishments, reaching 2,534 units operating across 19 industries being targeted. A sample of 526 respondents was considered as shown below:

The research has received the ethical clearance from the Research Ethics Review Committee of the Graduate School of Business Leadership, University of South Africa, on 13 August 2019 (Reference no.: 2019_SBL_DBL_012_FA).

The instrument was administered electronically through digital tablets using the Computer Aided Personal Interview (CAPI) tool. With consent of the participants, the data were collected anonymously through the services of an independent research company, Kantar, according to established methodology and quality control mechanisms to test integrity of the survey and engagements of the participants.

Univariate, bivariate and multivariate statistical analyses including other advanced techniques such as exploratory factor analysis (“EFA”), confirmatory factor analysis (“CFA”), path analysis and testing for mediation were considered using PROCESS, and the interpretation of results to better understand the underlying dynamics between the data and the model were effected.

Three responses were spotted as potential cases of unengaged responses given the very low variability in responses across all scale items (SD < 0.40) leading to a revised sample size from n = 526 to n = 523 for further analysis.

Considering the conceptual research model put forward and given that the adopted underlying instruments were already tested and validated by researchers on the global fronts, it was deemed appropriate to undertake CFA to confirm the model fit using the collected data as an initial step.

Each construct of the macro, meso and micro layers were subject to a model fit assessment through well-defined statistical procedures. Various model fit indices exist to evaluate a model, each having its own merits and limitations, however, researchers seem to agree that multiple criteria should be used to comprehensively test a model. This will enable one to confidently claim that the model represents the latent factor structure underlying the data (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). For assessment of model fit for this study, a consistent combination of indices were applied for all constructs as also posited by Matsunaga (Citation2011), including Chi-square/Degree of Freedom (CMIN/df), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR).

Where potential model fit manifested but lacked discriminant validity, it was deemed appropriate to conduct an EFA for such constructs so as to propose a new measurement model that can be defended on theoretical grounds. Factor models were identified and assessed on theoretical grounds. The model derived from the EFA was reassessed for model fit through CFA and the emerging factor model was retained where there was model fit, reliability and discriminant validity. A proxy measure was selected to measure certain constructs, more specifically for path analysis purposes, which still faced discriminant validity issues.

4. Research results

4.1. Descriptive statistics

The mean scores (with standard deviation) as well as the kurtosis values and Cronbach alpha coefficients are reported in .

Table 2. Target Population & Sampling

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics and Cronbach Alpha Coefficients

Table provides the descriptive statistics of each construct of the model. The respective means, standard deviations, kurtosis and Cronbach’s alphas have been computed and reported for each variable being studied in the model. There is a general tendency for most of the means (except for IEWP) to be closer to the “agree” response anchor in the scale, implying that they converge towards the items measuring the underlying characteristics of the respective constructs. The responses on the measurement of IEWP seem to be divided and relatively closer to the “neutral” response anchor. The Cronbach’s alphas indicate an acceptable to excellent level of internal consistencies amongst the group of items measuring the respective constructs. The correlations of all the constructs in terms of a matrix are reported in Table .

Table 4. Pearson Correlations of Seven Key Variables

Table provides the statistical correlations between the variables under study. The interrelationships were assessed and found to be statistically significant. All the variables are positively correlated with each other except for IEWP that has a negative relationship with the remaining variables. The strengths of the correlations are moderate to fairly strong between the variables, except for the correlation between IEWP and EEBC characterised by a weak insignificant negative association.

The model fit statistics for each of the instruments were computed, with specific reference to, minimum discrepancy per degree of freedom (CMIN/DF), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI) and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) are reported in Table . The model fit assessment was done in accordance with the values prescribed by from Hair et al. (Citation2014), Awang (Citation2012), Hu and Bentler (Citation1999), and Schumacker and Lomax (Citation2004).

Table 5. Model Fit Assessment of each of the instruments

Perceived Employee Performance—The results show that a single factor emerged with 15 items having high internal consistence reliability with a Cronbach alpha score (.94) for the perceived employee performance baseline model.

The results reported in Table are reasonable to excellent fit for all the instruments to be used in the analysis of the relationships between the constructs.

4.2. Mediating effects

To assess the overall Conceptual Research Model, there was a need to deconstruct the whole model into six sub-models for a granular evaluation. This approach enabled the measurement and evaluation of the mediating effects of ELDM and IEWP between the independent variables (OC and EOC) and the dependent ones (OCB, EEBC and PEP).

The Total Effect Model and the corresponding results for assessment of Total, Direct and Indirect Effects, were produced by the Hayes PROCESS Procedure for IBM SPSS Version 3.4.1 (Hayes, Citation2018). A 95% confidence level for all intervals was used in output. The number of bootstrap samples for percentile bootstrap confidence intervals was 5,000.

The output effect results from the Hayes PROCESS Procedure have been reported in standardised (β) formats. To assess the effect size between the predictor and outcome variables, Cohen (Citation1988, p. 83) reference guidelines were used. According to Cohen (Citation1988), the effect size is considered low if the value of r varies around .10, medium if r varies around .30, and large if r varies more than .50.

Table provides a summary of the statistical significance of the mediating effects by each sub model with its constituent constructs.

Table 6. Summary of Statistical Significance of Mediating Effects

Table summarises the direct and mediating effect sizes of the variables within each sub model under study.

Table 7. Summary Assessment of Effect Sizes of Sub Models

OC = Organisational Culture; EOC = Ethical Organisational Climate; ELDM = Ethical Leadership & Decision Making; IEWP = Internal & External Workplace Pressures; OCB = Organisational Citizenship Behaviour; EEBC = Employee Ethical Behaviour & Conduct; PEP = Perceived Employee Performance.

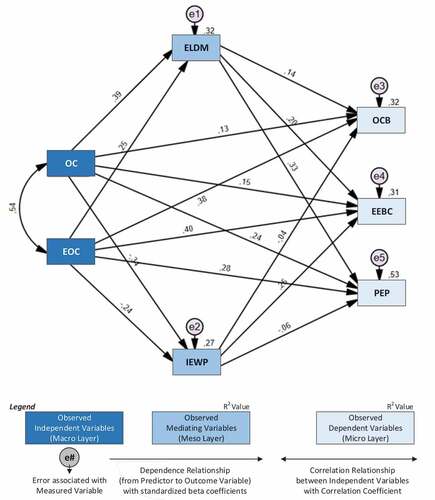

4.3. Holistic view & analysis of the path diagram

Figure shows a holistic representation of the path diagram supporting the Conceptual Research Model with corresponding interrelationships and effect sizes between the variables, as well as the culminating coefficients of determinations for the dependent variables.

Figure 2. The path diagram of the empirically studied model.

An examination of the resulting path diagram of the Conceptual Research Model shows the following key findings:

OC and EOC are independent variables that are positively interrelated (r = .54) and are jointly influencing the outcome variables by varying degrees.

Amongst the five outcome variables which OC is directly related to (i.e. ELDM, IEWP, OCB, EEBC and PEP), the

biggest effect is between OC and ELDM (β = .39) followed by IEWP (β = −.34), both of moderate sized effect.

This implies that OC considerably influences ELDM (positively) and IEWP (negatively) as compared to the other outcome variables. When assessing the effects on the dependent variables, it is noted that OC affects PEP to a higher degree (β = .24) as compared to OCB and EEBC.

As with the other macro level independent variable in the model, EOC impacts EEBC and OCB the most (β = .40 and β = .38 respectively) compared to the other outcome variables. EOC also affects IEWP negatively (β = −.24). The effect sizes of EOC on the dependent variables are relatively higher than OC’s effects.

As a predictor mediating variable, ELDM affects PEP the most with an effect size of .33 as compared to the other dependent variables of OCB and EEBC. ELDM nevertheless has a sizeable positive effect of .20 on EEBC. As regards IEWP, it influences EEBC (β = .25) more than the other two outcomes variables of OCB and PEP, where IEWP has a relatively small negative effect.

Analysing the coefficient of determination of ELDM indicates that 32% of the variation in ELDM is explained by the variation in OC and EOC as joint predictors in the regression model (R2 = .32). Likewise, 27% of the total variance in IEWP is shared between OC and EOC (R2 = .27).

OC and EOC as direct predictors, and ELDM & IEWP as mediating variables account for 53% of the total variance in PEP (R2 = .53). This indicates that they collectively explain a relatively high degree of variance in PEP compared to the other outcome variables of EEBC (R2 = .31) and OCB (R2 = .32).

OC and EOC as direct predictors, and ELDM & IEWP as mediating variables, account for 32% of the total variance in OCB (R2 = .32).

When assessing the variance in EEBC, it must be noted that ELDM and IEWP have a statistically insignificant mediating effect on EEBC (as evidenced in Model 4.4 in Table ). This implies that 31% of the variance in EEBC is explained by the collective effect of OC, EOC and the mediating effect of ELDM and IEWP when using OC as the only independent variable.

5. Discussions

The research question put forward called for an empirical examination of the direct and indirect effects that organisational culture and ethical organisational climate (as macro level independent variables) have on organisational citizenship behaviour, ethical employee behaviour and conduct, and perceived employee behaviour (as dependent variables). The main empirical aim was to also establish whether the mediating variables (ethical leadership and decision making, and internal and external workplace pressures) have a bigger influence on the dependent variables when they intervene as mediators in the business context of Mauritius.

5.1. What is the statistical relationship between organisational culture and ethical organisation climate?

The result indicate that there is a moderate positive relationship between organisational culture and ethical organisational climate, r(521) = .54, p < .001.

5.2. What is the statistical relationship between the mediating variables of ethical leadership and decision making, and internal and external workplace pressures?

Ethical leadership and decision making has a moderate negative relationship with internal and external workplace pressure, r(521) = −.34, p < .001.

As also evidenced through the regression and path analysis, the two main independent variables predict the mediating and observed dependent variables in the model.

The correlations suggest that a stronger organisational culture tends to be associated with a stronger ethical organisational climate. On the other hand, an increased prevalence of ethical leadership and decision making in the organisation tend to be associated with lower degrees of workplace pressures. Likewise, a deficiency in ethical leadership fuels adverse workplace pressures often resulting in employees transgressing ethical norms and practices. This is also supported by the findings of Vaughan (Citation1983) and Passas (Citation1990).

5.3. What is the nature of the theoretical and observed interrelationships between the independent variables (organisational culture and ethical organisational climate) and the mediating variables (ethical leadership and decision making, and internal and external workplace pressures), and their effects on the dependent variables (organisational citizenship behaviour, employee ethical behaviour and conduct, and perceived employee performance)?

An overarching effect—As independent variables, organisation culture and ethical organisational climate jointly influence the observed variables at the meso and micro levels at varying degrees.

The effects of organisational culture—Organisational culture, as characterised by three factors of achieving business goals, people consideration and work ethics in the local context, has a bigger effect on ethical leadership and decision making (β = .39, p < .001) as compared to the other variables. It positively influences ethical leadership and decision-making behaviours in the business context of Mauritius. A common pattern was found in previous studies where organisational culture is also linked with personal values of leaders (Douglas et al., Citation2001; Schein, Citation2010; Schein & Schein, Citation2017; Schwartz, Citation1992). The organisation culture components play an important predictor role, not only on ethical leadership and decision making but also on internal and external workplace pressure. The result indicates that organisational culture has a moderate negative influence on workplace pressures. For instance, promoting care for people in the work environment where their concerns are heard, they are kept informed on a timely basis, and team spirit and support are permeating will reduce situational stress in both the enterprise and on the individual. In such conditions, people in the organisation will be under less pressure to violate ethical guidelines. Furthermore, the study also shows that organisational culture influences organisational citizenship behaviour (β = .13, p < .001), employee ethical behaviour and conduct (β = .15, p < .001) and perceived employee performance (β = .24, p < .001) in the business context of Mauritius. For instance, the prevalence of people consideration and team spirit in the organisation will positively influence employees to perform beyond what is expected, respect and support others, make an extra effort to help co-workers even if it is not mandatory. All this characterises organisational citizenship behaviour.

The effects of ethical organisational climate—In the context of this study, ethical organisational climate has emerged, with characteristics of principle-orientation, benevolence and altruism prevailing to varying degrees in the Mauritian workplace. The study confirms that ethical organisation climates predict ethical leadership and decision making (β = .25, p < .001). For instance, a climate of consideration for others (co-workers, people, organisation and society) and for compliance (laws, rules, principles and procedures) influences people’s ethical orientation and decision making. The study further confirms that ethical organisational climate influences organisation citizenship behaviour and employee ethical behaviour and conduct to a considerable extent as compared to other variables (β = .38, p < .001 and β = .40, p < .001 respectively), with the effects found to be statistically significant.

These results build on existing evidences of Huhtala et al. (Citation2011) and Mitonga-Monga and Cilliers (Citation2015), who advocated that workplace ethics predicts work engagement behaviour and commitment to the organisation. Mitonga-Monga and Cilliers (Citation2015) found that workplace ethics culture and climate had the most impactful contribution on work engagement. A positive inclination towards an ethical climate is characterised by concerns of what is best for employees, clients, public and a general tendency towards adhering to organisational rules and policies. This has a corresponding impact on fostering civic virtues, altruism and an attitude to do beyond what is expected in the best interests of the co-workers, teams and the organisation at large. On the other hand, a climate where ethical deviances prevail in the organisation has a counterproductive effect on the employees with increasing stress and pressures to compromise their ethical stances. The results show that the prevalence of ethical organisational climate has a reverse and attenuating effect on workplace pressures (β = −.24, p < .001). The results on the effects of ethical climate in organisations in Mauritius are also consistent to the findings of Huhtala et al. (Citation2011), who advocated that a work environment characterised by ethical standards, systems and practices fosters the emotional engagement and work commitment levels of employees. This is consistent to the findings of Mohanty and Rath Citation2012 whereby if organisational culture is nurtured, it can inculcate citizenship behaviour in employees within the organisation.

The combined effects of organisational culture and ethical organisational climate—The study reveals that these two independent macro level variables have a combined moderate sized effect (statistically significant) on ethical leadership and decision making (R2 = .32, p < .001) and on internal and external workplace pressures (R2 = .27, p < .001). The results suggest that the two independent variables jointly predict the ethical leadership behaviours, ethical orientation in decision making and workplace pressures to a considerable extent.

The meso variables and their mediating effects—The results show that, as a predictor mediating variable, ethical leadership and decision making influences perceived employee performance the most (β = .33, p < .001), compared to the other two variables of organisational citizenship behaviour (β = .14, p < .001) and employee ethical behaviour and conduct (β = .20, p < .001). The study also indicates that when fairness, sharing of power, concerns for work ethics and environment, integrity, people consideration prevail in an organisation, it positively influences the way employees perform and their perception on their work environment. The more ethical leadership behaviours and ethical-oriented decision making are manifested, the more employees would perceive their work environment as motivating, performing and conducive to support team collaboration, productivity and ethical conduct. These results build on the existing evidence of Mo et al. (Citation2012), where ethical leadership was established as a key predictor influencing employees’ moral attitude and behaviour. On the other hand, an increase in internal and external workplace pressures adversely impacts employees’ performance and citizenship behaviour. Vidaver-Cohen. (Citation1993) suggests that such pressures also lead towards behavioural challenges and moral regression amongst employees.

To assess the mediating effect and establish whether the meso-level variables indirectly contribute to the overall model, the direct and indirect effects were evaluated in the study and used as comparatives to determine on whether ELDM and IEWP play an important role in the total effect equation. The direct effect sizes of EOC on OCB, EOC on EEBC, EOC on PEP and OC on PEP are of moderate to high effect (β between .30 and .50, p < .001), with these effects being statistically significant. Furthermore, the contribution of the indirect effects of ELDM and IEWP, as mediating variables, between OC and OCB, EOC and PEP, and OC and PEP represent between 40 to 44% of the total effects, thereby indicating relatively sizeable mediating effects on the dependent variables. These results show that ethical leadership and decision making, and workplace pressures play a crucial mediating role and considerably influence organisational citizenship behaviour and perceived employee performance in the business environment of Mauritius. The findings of Vaughan (Citation1983) and Passas (Citation1990) on the study of anomie and corporate deviances indicate that workplace pressure for meeting organisational objectives compelled employees to leave their ethical paths. A similar pattern seems to appear in the current context, where shareholders tend to be interested in profits, not necessarily in the way they are realised.

The overall effect—The present study provides new insights in respect of the dynamics of the multi-layered interconnected variables within the Conceptual Research Model. OC and EOC (as direct independent variables) and ELDM and IEWP (as mediating variables) account for 53% of the total variance in perceived employee performance (R2 = .53, p < .001). This indicates that they collectively explain a relatively high degree of variance in perceived employee performance compared to the other outcome variables of OCB (R2 = .32, p < .001) and EEBC (R2 = .31, p < .001). Furthermore, the study also shows that direct predictors (OC and EOC) and mediating variables (ELDM and IEWP) account for 32% of the total variance in OCB (R2 = .32, p < .001). The reported variances were found to be statistically significant. When assessing the variance in EEBC, it must be noted that ELDM and IEWP jointly have a statistically insignificant mediating effect exceptionally between EOC and EEBC. This implies that 31% of the variance in EEBC is explained by the combined effect of OC, EOC and the mediating effects of ELDM and IEWP when OC is the main predictor.

5.4. Is there a good fit between the elements of the empirically manifested structural model and the theoretically hypothesised model?

A step by step approach was adopted to test each component of the Conceptual Research Model. As advocated by Matsunaga (Citation2011) and to avoid any biasness in model fit assessment, the same set of model fit indices (CMIN/df, RMSEA, CFI and SRMR) were consistently used and evaluated throughout the hypothesised model.

On the basis of the theoretical foundation and empirical evidence, the study enabled the development of a sound multi-factor ethical climate model that fosters organisational citizenship behaviour. The model, which is henceforth referred to as the “Ethical Climate Model for Organisational Citizenship Behaviour”, aims to support business enterprises in setting the right foundation that will primarily promote organisational citizenship behaviour as well as employee ethical behaviour, conduct and performance in the workplace.

The model, which has successfully been tested empirically and demonstrates a good fit, confirms the interrelationships and effects that the macro level variables have on the observed micro variables both directly and through the meso layer variables. In other words, having the right ethical culture and climate within the enterprise leads to employees demonstrating civic virtue, sportsmanship, altruism, ethical conduct, compliance to norms and performance at work.

The model also confirms that ethical leadership and decision making as well as workplace pressures have a considerable mediating effect on organisational citizenship behaviour and perceived employee performance within enterprises. This therefore necessitates proper attention when shaping the right ethical culture and climate.

6. Conclusion

The paper aimed at evaluating, using a macro-meso-micro model, the dynamics of ethical climate and the effects that the independent variables (Organisational Culture and Ethical Organisational Climate) have on the dependent variables (Organisational Citizenship Behaviour, Employee Ethical Behaviour and Conduct, and Perceived Employee Performance) both directly and more importantly through the mediating variables (Ethical Leadership and Decision Making, and Internal and External Workplace Pressure).

The results confirm that all the variables in the model are positively correlated with each other except for Internal and External Workplace Pressure that has a negative relationship with the remaining variables.

The results further indicate that Organisational Culture and Ethical Organisational Climate jointly influence Organisational Citizenship Behaviour, Employee Ethical Behaviour and Conduct, and Perceived Employee Performance both directly and indirectly at varying degrees. Furthermore, the two independent variables jointly influence ethical leadership behaviours, ethical orientation in decision making and workplace pressures to a considerable extent.

The findings also show that Ethical Leadership and Decision Making, and Internal and External Workplace Pressure play a crucial mediating role and considerably influence Organisational Citizenship Behaviour and Perceived Employee Performance in the corporate context of Mauritius.

The overall results indicate that the independent and mediating variables in the model collectively explain a relatively high degree of variance in all the three dependent variables (R2 ranging between 0.31 and 0.53, statistically significant). Based on the model fit assessment, the model put forward demonstrates a good fit.

On the basis of the empirical findings, the following four recommendations are made to the business and research communities for consideration in a quest to transform and strengthen the ethical culture and organisational citizenship behaviour in business enterprises:

Firstly, nurture the right organisational culture as a baseline empowering enabler, as it has an important influence in the way employees across hierarchies shape their perception and behaviour. Business leaders should therefore ensure that they lay the right foundation in setting clear business goals and priorities. They should provide the required support to solve business problems, striking the right balance between achieving business goals, people’s consideration, work ethics and promoting transparency.

Secondly, Foster ethics principles and fair practices as part of an overarching work climate. Business enterprises should sense, regulate, and promote the right climate, orientated towards compliance to principles, rules and standards whilst demonstrating concerns for others (people, organisation and society). Such attributes directly influence people’s willingness to deliver beyond their normal prescribed duties whilst also promoting ethical behaviour on their part in the best interests of the organisation. Organisational climate characterised by ethical standards and ethical considerations would ultimately foster the emotional engagement and work commitments of the employees.

Thirdly, demonstrate ethical leadership qualities to stimulate positive behaviour, engagement and performance, as business leaders have a duty to create the right work environment for their stakeholders. They must demonstrate ethical leadership behaviours (fairness, integrity, people consideration, role clarification, power sharing, respect for deontological duties, and concerns for sustainability) and also show that decisions are made on the basis of ethical consideration and fairness. This will create an environment that will stimulate employee motivation, engagement, citizenship behaviour, ethical conduct and performance. People should see fairness in treatment, high standards of ethical decisions and actions prevailing in the organisation and demonstration of ethical traits and stewardship of their leaders.

Lastly, regulate workplace pressures to restrict anomie and unhealthy climate, as improper workplace pressures has been found to adversely impact the employees’ morale and supress their abilities and motivation to excel. To avoid adverse behavioural challenges, moral regression and an unhealthy work climate amongst employees, businesses have to review their approaches in achieving business goals. They must regulate the nature and intensity of workplace pressures for the welfare of their employees and success of the organisation. Striking the right balance between achieving business targets and the means of achieving such goals are fundamental in creating a healthy and ethical work environment.

As supported empirically through the model (coined as Ethical Climate Model for Organisational Citizenship Behaviour), the implementation of the above four recommendations will considerably influence organisational citizenship behaviour, employee ethical behaviour and conduct, and perceived employee performance to manifest within enterprises. Efforts should therefore be made by the business community in adopting such recommendations for the welfare of the organisations.

This study brings vital contributions to the field of social science from a theoretical, empirical, business and country perspective. On a theoretical level, the study builds on previous research of Jeurissen (Citation1997), Dopfer et al. (Citation2004), Li (Citation2012) and Engelbrecht et al. (Citation2017) and responds to their calls for the adoption of a new direction in social science research through a macro-meso-micro framework. The present study of ethics in the workplace was therefore structured on such a framework which provided precise understanding and new insights as to how ethical and behavioural context variables are interrelated and influence the dependent variables. The study, in particular, also demonstrates how the complexities of ethical climate can be broken down and their dynamics be studied through macro-meso-micro lenses.

The findings of the study contributed to the development of an empirically tested Ethical Climate Model for Organisational Citizenship Behaviour encapsulating the direct effects of organisational culture and ethical organisational climate, and the mediating effects of ethical leadership and workplace pressures on organisational citizenship behaviour. The extensive scope and depth of the present research and its valuable outcomes add a new dimension to the ethical and behavioural knowledge base for Mauritius and the larger research community, as it demonstrates how organisational citizenship behaviour could be nurtured through the dynamics, interplay and effects of organisational culture, ethical climate and ethical leadership whilst regulating workplace pressures. A collective consciousness, mobilisation and action by all stakeholders will shift corporate ethical climate and culture to the next level of maturity and create a platform that will foster organisational citizenship behaviour and employee ethical conduct nationwide.

The limitations of this study are mostly related to the methodology used. Firstly, self-reporting questionnaires were used which might lead to method bias, even after the necessary precautionary measures were taken during the briefing that results will be treated anonymously and confidentially. Social desirability and subsequent response bias remain a concern and a limitation in studies such as this, while self-reporting instruments may be a one-sided report from respondents.

Secondly, the cross-sectional design used in this study might have increased the relationship between the components artificially.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

O Sookdawoor

O Sookdawoor Doctor of Business Leadership., Graduate School of Business Leadership, University of South Africa, [email protected]

A Grobler

Grobler, A PhD (Industrial and Organisational Psychology), Graduate School of Business Leadership, University of South Africa, [email protected]

References

- Ah-Kion, J., & Bhowon, U. (2017). Leadership and Ethical Decision Making among Mauritian Managers. Elecronic Journal of Business Ethics and Organzational Studies, 22(1), 1239–25.

- Ah-Teck, J. C., & Hung, D. (2014). Standing on the shoulders of giants: An ethical Leadership agenda for educational reform in Mauritius. International Journal of Arts & Sciences, 07(3), 355–375.

- Alizadeh, Z., Darvishi, S., Nazri, K., & Emami, M. (2012). Antecedents and Consequences of Organisational Citizenship Behaviour. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, 3 (9), 1–12. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/251842155_Antecedents_and_Consequences_of_Organisational_Citizenship_Behaviour_OCB

- Awang, Z. (2012). Research Methodology and Data Analysis. Penerbit Universiti Teknologi MARA Press.

- Bateman, T. S., & Organ, D. W. (1983). Job satisfaction and the good soldier: The relationship between affect and employee citizenship. Academy of Management Journal, 26(4), 587–595. https://doi.org/10.2307/255908

- Black, S. J., & Morrison, A. J. (2014). The Global Leadership Challenge (2nd ed., pp. 46–48). Routledge.

- Boudreaux, C. J., Karahan, G., & Coats, M. (2016). Bend it like FIFA in and off the pitch. Managerial Finance, 42(9), 866–878. https://doi.org/10.1108/MF-01-2016-0012

- Brown, M. E., Trevino, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct develop- ment and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.002

- Burns, J. M. (1979). Leadership. Harper & Row.

- Caplan, D. H., Dutta, S. K., & Marcinko, D. J. (2019). Unmasking the fraud at Toshiba. Issues in Accounting Education, 34(3), 41–57. https://doi.org/10.2308/iace-52429

- Chan-Meetoo, C. (2013). A UNESCO/UOM initiative. Ethical Journalism & Gender-Sensitive Reporting (March). UOMPRESS, University of Mauritius.

- Ciro, T. (2012). The Global Financial Crisis: Triggers, Responses and Aftermath. Routledge.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Science ((Routledge ed); 2nd ed. ed.). Erlbaum.

- Cohen, D. V., & Vidaver-Cohen. (1993). Creating and Maitaining Ethical Work Climates: Anomie in the Workplace and Implications for Managing Change. Business Ethics QuarterlyEthics, 3(4), 343–359. https://doi.org/10.2307/3857283

- Deconinck, J. B., Deconinck, M. B., & Moss, H. K. (2016). The Relationship Among Ethical Leadership, Ethical Climate, Supervisory Trust, and Moral Judgment. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 20(3), 89–100.

- Delaney, J. T., & Huselid, M. A. (1996). The Impact of human resource management practices on perceptions of organizational performance. The Academy of Management Journal, 39(4), 949–969. https://doi.org/10.5465/256718

- Dopfer, K., Foster, J., & Potts, J. (2004). Micro-Meso-Macro. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 14, 263–279.

- Douglas, P. C., Davidson, R. A., & Schwartz, B. N. (2001). The effect of organizational culture and ethical orientation on accountants’ ethical judgments. Journal of Business Ethics, 34(2), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012261900281

- Engelbrecht, A. S., Wolmarans, J., & Mahembe, B. (2017). Effect of Ethical Leadership and Climate on Effectiveness. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 15(March), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v15i0.781

- Ernst & Young. (2020). COVID-19: Unravelling fraud and corruption risks in the new normal.

- Ethics & Compliance Initiative. (2018). The state of ethics & compliance in the workplace - global business ethics survey. Ethics & Compliance Initiative (ECI).

- Ethics Resource Center. (2012a). National business ethics survey ® of fortune 500 ® employees: An Investigation into the State of Ethics at America’s Most Powerful Companies. Ethics Resource Center.

- Evan, W. M. (1968). . Organisational Climate: Explorations of a Concept (pp. 105–124). Harvard University.

- Ford, J. (2006). Discourses of Leadership: Gender, identity and contradiction in a UK public sector organisation. Leadership, 2(1), 77–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715006060654

- Gaspar, V., Martin Mühleisen, M., & Weeks-Brown, R. (2020). Corruption and COVID-19. International Monetary Fund (IMFBlog). https://blogs.imf.org/2020/07/28/corruption-and-covid-19/

- Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25(2), 161–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092623

- Grobler, A., & Grobler, S. (2018). Conceptualisation of organisational ethics: A multilevel meso approach. Ethical Perspectives, 25(4), 715–751. https://doi.org/10.2143/EP.25.4.3285712

- Grobler, S., & Grobler, A. (2021). Ethical leadership, person-organizational fit, and productive energy: A South African sectoral comparative study. Ethics & Behavior, 31(1), 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2019.1699412

- Grobler, A., & Joubert, Y. T. (2020). The relationship between hope and optimism, ethical leadership and person-organisation fit. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 23(1), a2872. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v23i1.2872

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate Data Analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Education Limited.

- Harste, G. (1994). The definition of organisational culture and its historical origins, history of European Ideas. Elesevier Science Ltd, 19(1–3), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-6599(94)90191-0

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). PROCESS Procedure for SPSS (3.4.1). www.afhayes.com

- Huang, L., & Paterson, T. A. (2017). Group Ethical Voice. Journal of Management, 43(4), 1157–1184. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314546195

- Hu, T. L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indices for covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modelling. Structural Equation Modelling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Huhtala, M., Feldt, T., Lamsa, A. M., Muano, S., & Kinnunen, V. (2011). Does ethical culture of organisations promote managers’ occupational well-being? Investigation indirect links via ethics strain. Journal of Business Ethics, 101(2), 231–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0719-3

- The Institute of Leadership and Management. (2011). ILM and Management Today. The Institute of Leadership and Management.

- Jeurissen, R. (1997). Integrating micro, meso and macro levels in business ethics. Ethical Perspectives, 4(2), 246–254. https://doi.org/10.2143/EP.4.4.562986

- Kalshoven, K., Den Hartog, D. N., & De Hoogh, A. H. B. (2011). Ethical leadership at work questionnaire (ELW): Development and validation of a multidimensional measure. The Leadership Quarterly, 22, 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.12.007

- Kant, I. (1790). The Critique of Judgement J. (Macmillan) Bernard (ed.). Liberty Fund Inc. The Online

- Kaptein, M. (2008a). Developing and testing a measure for the ethical culture of organizations: The corporate ethical virtues model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29(7), 923–947. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.520

- Knights, D., & O’Leary, M. (2006). Leadership, ethics and responsibility to the other. Journal of Business Ethics, 67(2), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9008-6

- Konovsky, M. A., & Pugh, S. D. (1994). Citizenship behavior and social exchange. Academy of Management Journal, 37(3), 656–669. https://doi.org/10.5465/256704

- Kotter, J. P., & Heskett, J. L. (1992). Corporate culture and performance. Free Press.

- Lasakova, A., & Remisova, A. (2017). On Organisational Factors that Elicit Managerial Unethical Decision-Making. Ekonomicky Casopis, 65(4), 334–354.

- Lawton, A., & Páez, I. (2015). Developing a framework for ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(3), 639–649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2244-2

- Lee, Y., & Chao, L. (2011). Alibaba.com CEO resigns in wake of fraud by sellers. Wall Street Journal. Online Edition. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748704476604576157771196658468

- Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science. Harper and Row.

- Lewin, K., Lippitt, R., & White, R. K. (1939). Patterns of aggressive behaviour in experimentally created social climates. Journal of Social Psychology, 10(2), 271–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1939.9713366

- Li, B. (2012). From a micro-macro framework to a micro-meso-macro framework (S. H. Christensen, C. Mitcham, B. Li, & Y. An, eds.). Springer, Philosophy of Engineering and Technology Series. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5282-5_2

- Maesschalck, J. (2004). Measuring ethics in the public sector: An assessment of the impact of ethical climate on ethical decision making and unethical behaviour. In EGPA Annual Conference (Issue September).

- Matsunaga, M. (2011). How to Factor-Analyze Your Data Right : Do ’ s, Don ’ ts, and How To ’s. International Journal of Psychological Research, 3(1), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.21500/20112084.854

- Mayer, D. M., Kuenzi, M., Greenbaum, R., Bardes, M., & Salvador, R. B. (2009). How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2008.04.002

- Merton, R. K. (1964). Anomie, Anomia and Social Interaction. Context of Deviant Behaviour.

- Mitonga-Monga, J., & Cilliers, F. (2015). Ethics culture and ethics climate in relation to employee engagement in a developing country setting. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 25(3), 242–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2015.1065059

- Mohanty, J., & Rath, B. P. (2012). Influence of Organisational Culture on Organisational Citizenship Behaviour: A Three-Sector Study. Global Journal of Business Research, 6(1). https://ssrn.com/abstract=1946000

- Mo, S., & Shi, J. (2017). Linking ethical leadership to employees ’ organizational citizenship behavior : Testing the multilevel mediation role of organizational concern. 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2734-x

- Mo, S., & Shi, J. (2017). Linking Ethical Leadership to Employees ’ Organizational Citizenship Behavior : Testing the Multilevel Mediation Role of Organizational Concern. Journal of Business Ethics, 141, 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2734-x

- Napal, G. (2003). Ethical decision making in business: Focus on Mauritius. Business Ethics: A European Review, 12(1), 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8608.00305

- Napal, G. (2005). Is bribery a culturally acceptable practice in Mauritius?”. Business Ethics: A European Review, 14(3), 231–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8608.2005.00406.x

- Newman, A., Round, H., Bhattacharya, S., & Roy, A. (2017). Ethical climates in organizations: A review and research agenda. Business Ethics Quarterly, 4(October), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2017.23

- OECD. (2016). Society at a Glance 2016. https://doi.org/10.1787/soc_glance-2014-en

- Organ, D. W., & Konovsky, M. (1989). Cognitive versus affective determinants of organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(1), 157–164. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.74.1.157

- Padachi, K., Urdhin, H. R., & Ramen, M. (2016). Assessing corporate governance practices of mauritian companies. International Journal of Accounting and Financial Reporting, 6(1), 38–71. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijafr.v6i1.9281

- Passas, N. (1990). Anomie and Corporate Deviance. Contemporary Crises, 14(2), 157–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00728269

- Patterson, M. G., Warr, P. B., & West, M. A. (2004). Organizational climate and company performance: The role of employee affect and employee level. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77(2), 193–216. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317904774202144

- Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., Moorman, R. H., & Fetter, R. (1990). Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior. The Leadership Quarterly, 1(2), 107–142.

- Pritchard, R. D., & Karasick, B. W. (1973). The effects of organizational climate on managerial job performance and satisfaction. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 9(1), 126–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(73)90042-1

- PwC. (2016). Global Economic Crime Survey 2016. 1–31.

- Rioux, S. M., & Penner, L. A. (2001). The cause of organizational citizenship behavior: A motivational analysis. Journal OfApplied Psychology, 86(6), 1306–1314. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.86.6.1306

- Robbins, S., & Judge, T. A. (2013). Organisational Behaviour. Pearson Education Inc Ed. 15th ed. Organisational Behaviour. 512. Prentice Hall.

- Sashkin, M., & Rosenbach, W. E. (2013). Organizational Culture Assessment Questionnaire. 1–12. http://cimail15.efop.org/documents/OCAQParticipantManual.pdf

- Schein, E. H. (1985). Organizational culture and leadership: A dynamic view. Jossey-Bass.

- Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership (6th ed. ed.). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Schein, E. H., & Schein, P. (2017). Organisational culture and leadership (5th ed. ed.). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Schneider, B. (1990). The climate for service: An application of the climate construct. In B. Schneider (Ed.), Organizational climate and culture (pp. 383—412). San Francisco: Jossey- Bass.

- Schneider, B., & Reichers, A. E. (1983). On the etiology of climates. Personnel Psychology, 36(1), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1983.tb00500.x

- Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (2004). A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 1–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60281-6

- Schweitzer, M. E., Ordonez, L., & Douma, B. (2004). Goal setting as a motivator of unethical behaviour. Academy of Management Journal, 47(3), 422–432. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159591

- Sibiya, L., Makoni, T., & Van Wyk, R. (2016). Investigating the relationship between ethical climate and psychological capital. Proceedings of 28th Conference of The Southern African Institute of Management Sciences (SAIMS), September, 57–71.

- Smith, C. A., Organ, D. W., & Near, J. P. (1983). Organizational citizenship behavior: Its nature and antecedents. Journal of Applied Psychology, 68(4), 653–663. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.68.4.653

- Statistics Mauritius. (2017). Republic of Mauritius 2013 Census of Economic Activities (Issue May). http://statsmauritius.govmu.org

- Toor, S. R., & Ofori, G. (2009). Ethical leadership: Examining the relationships with full range leadership model, employee outcomes, and organisational culture. Journal of Business Ethics, 90(4), 533–546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0059-3

- Vaughan, D. (1983). Controlling unlawful organizational behavior: Social structure and corporate misconduct. University of Chicago Press.

- Victor, B., & Cullen, J. B. (1988). The organizational bases of ethical work climates. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33(1), 101. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392857

- Victor, B., & Cullen, J. B. (1998). The organisational bases of ethical work climates. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33(1),101–125. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392857

- Vidaver-Cohen, D. (1995). Creating ethical work climates, A socioeconomic perspective. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 24(2), 317–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/1053-5357(95)90024-1

- Wilmarth, A. (2013). Citigroup: A case study in managerial and regulatory failures. Indiana Law Review, 47(1), 69–137. https://doi.org/10.18060/18342

- Zhu, W., May, D. R., & Avolio, B. J. (2004). The impact of ethical leadership behavior on employee outcomes: The roles of psychological empowerment and authenticity. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 11(1), 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/107179190401100104