?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Recent research has focused mainly on the impact of corporate social responsibility (CSR). However, few studies have examined the impact of CSR and corporate image on organic food consumption, particularly in developing nations. This study explores the effect of corporate social responsibility on consumers’ intention to purchase organic food in Thailand. This research paper conducts quantitative analysis using a questionnaire that sampled 523 Thai consumers. To examine the effects of the product image and corporate reputation for corporations that implement corporate social responsibility programs on consumer decision-making, a structural equation model is applied. The results supported that product image and corporate image/reputation were the crucial factors influencing Thai consumers’ perspectives and purchase intentions. This research contributes to guiding corporations in applying the findings to build their company image and corporate social responsibility (CSR) toward enterprises. The current study demonstrates how green knowledge and environmental concerns assist firms and contribute to achieving sustainable development goals, focusing on environmental elements. Data collection and generalization to other green consumers are limitations of this study.

Jel classifications:

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Consumption of green products has been rising in emerging countries. Thailand is one of them as a result of the influence of business communication through green marketing and their CSR program. This study attempts to highlight how business activities affect corporate reputation. This study advances academic knowledge in the field of green customers’ intentions to purchase organic food by examining the effects of the product image, corporate social responsibility, green marketing, and company reputation. Finally, green consumption can not only improve consumer health and farmer safety, but also help society achieve its goals for sustainable development.

1. Introduction

The world has experienced resource and environmental problems such as global warming, nonbiodegradable solid waste, and the harmful impacts of pollutants. Green marketing was initiated in the 1980s when the United Nations noticed the effects of global warming. Green marketing is a tool to protect the environment by producing and promoting products or services that are environmentally friendly or generate a positive effect on the environment (Rahbar & Wahid, Citation2011). The former definition of this strategy was recommending safe and eco-friendly products. Green marketing also refers to other marketing concepts, such as ecological marketing, environmental marketing, or sustainable marketing (Tapa & Verma, Citation2014). In recent years, green marketing has established entrepreneurial opportunities to encourage organizations and positively impact consumers in the aspects of quality, convenience, and price without affecting the environment (Poungchompu et al., Citation2012). Consumer demand for and acceptance of organic foods have increased worldwide (Willer et al., Citation2021). Due to customers’ choice of safer and healthier foods during the past few years, the market value of such foods tends to be rising (Jitrawang & Krairit, Citation2019). Organic food markets have been expanding in developed and developing countries. Organic foods are positioned as healthy, environmentally friendly products and have a low risk to farmers’ health, thus receiving a high selling price in return (Mohamad et al., Citation2014). In Thailand, which has a higher cost of organic food production, the agricultural industry cannot avoid using chemical substances, which can degrade natural resources and the environment (Poungchompu et al., Citation2012). Organic foods are considered healthful, the best option for the environment, and low risk to the health of farmers. This allows organic food markets to significantly expand in developed and developing agricultural economies worldwide, including Thailand, (JiumpanyaracJiumpanyarach, Citation2018). In Thailand’s northeastern region, which is the main area that produces organic foods that are sold in markets, an organic food standard network has been established to ensure the product’s safety and quality (Sitthisuntikul et al., Citation2018). Policies and regulations can establish a certified organic logo to prove quality and safety to farmers and consumers (Janssen, Citation2010). Previous research studied consumers in organic food markets. For example, Aungatichart et al., ((Citation2020) studied factors motivating customers’ purchase intention and actual behaviours of organic food in Thailand. The research results demonstrate the considerable influence of intention on real organic food buying behaviour and reveal that the actual purchase behaviour of Thai consumers of organic food is significantly influenced by purchase intention (Aungatichart et al., ((Citation2020). In 2006, Thailand enforced the organic agricultural rules, the objectives of which are to reduce farmers’ debt, increase production, mitigate health risks, improve the environment, and assist smallholder farmers in achieving sustainability. Thailand’s 10th, 11th, and 12th National Economic and Social Development Plan have attempted to implement organic strategies, including delivering organic knowledge and innovation, developing both traditional and commercial organic farming and enhancing management and coordination mainly for the countrys organic agriculture development (JiumpanyaracJiumpanyarach, Citation2018).

Currently, green marketing has been used as a unique selling proposition and emphasizes food for consumption. A trend of health and environmental awareness among consumers, especially the consumption of healthy foods, has grown. Consumers are aware of maintaining their health and consuming safe and beneficial food (Smith & Paladino, Citation2010). Moreover, consumers have become more attentive to social responsibility for natural resources and the environment by buying eco-labelled products, sorting waste, recycling, and saving energy. Various activities, including packaging changes, product adaptation, and adjustable advertising, respond to humans’ needs and expectations with a minor effect on the environment (Ko et al., Citation2013). Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is a central concept in the marketing industry (Akbari et al., Citation2019; Han & Lee, Citation2021). However, there have been few studies concerning consumer social responsibility, particularly in emerging economies (Christis & Wang, Citation2021; Munerah et al., Citation2021). The resource-based theory asserts that corporate social responsibility (CSR) is a desirable addition to a differentiation strategy because it raises the value of a companys reputation across a wide range of industries (Famiyeh, Citation2017; McWilliams et al., Citation2011) but, none of which has attained CSR in the organic food industry.

The recent increase in organic food consumption in Thailand can be linked to government legislation, an increase in consumer affluence, and a shift in food consumption habits (Yanakittkul & Aungvaravong, Citation2020). Thailand exports and sells organic products to well-known worldwide grocery chains and organic-focused stores. Exports of organic foods to the United States, the United Kingdom, Scandinavian countries, and Singapore experienced double-digit growth rates (Pracharuengwit & Chiaravutthi, Citation2015).

Thus, many factors, such as being environmental friendliness and environmental knowledge, affect consumers’ purchase intentions and perspectives on organic food products. Including a product image and promoting social responsibility could affect a companys reputation. The organic food concept of entrepreneurship starts with the desire to create beneficial advantages, which are helpful for Thai consumers and inspired by the sufficiency economy concept. Organic foods are the first choice for health lovers. They are also consumed by the concept of “save the world”. Green marketing is a business that does not cause any adverse effects on the global environment or the surrounding society. Green marketing may also include having a considerable impact on the economy. Thus, using green marketing is one method to create knowledge and understanding of the problems and obstacles and provide guidelines for success.

In developing a CSR system in the organic food industry, marketers should understand the relationship between CSR and consumers’ purchase intention; however, few studies in Thailand have studied or measured this particular component. Hence, the present research aims to (1) investigate the interrelationship among the factors influencing Thai consumers’ attention to purchase organic foods and (2) evaluate the influence of the green marketing reputation of organic food businesses on consumers.

2. Study references and hypothesis

2.1. Green marketing and the role of green marketing

There are various definitions of green marketing as forming essential business strategies in the future and increasing awareness of the environment (McDaniel & Rylander, Citation1993). Green marketing is one of the critical trends in modern business (Pujari & Wright, Citation1996) focusing on a customer who prefers eco-friendly goods and services (Y. K. Lee, Citation2020).

According to the American Marketing Association (AMA), green marketing was described as the activities conducted by companies related to requirements and recommendations for combining environmental issues with an organizations strategic marketing plan to establish consumers’ and societys satisfaction (Bennett, ; R & I, Citation2011). Moreover, green marketing is a strategy for manufacturing goods that can promote environmentally responsible behaviour and sustainable development of a society (Rajadurai et al., Citation2021; Tulsi & Ji, Citation2020).

The role of green marketing is marketing with environmental responsibility and providing an example of sustainable practices for consumers through marketing. The theory of green marketing is significant for marketing information regarding environmental responses. Few studies have examined the high degree of environmental knowledge; hence, there is a crucial positive impact on consumers’ green purchasing intention (Hossain & Marinova, Citation2013). Currently, companies and consumers pay attention to the effects of their acts on the environment and the environment they form (Domazet et al., Citation2016). A further integrative viewpoint defines “Green marketing” as the synthesis of consumer perspectives, the generation of profitability through purchasing and environmental responsibility (Sedky & AbdelRaheem, Citation2022).

Currently, consumers become more mindful of environmental preservation, ethical consideration, sustainable production, and responsible marketing practices (Khattak, Citation2019). Nevertheless, green marketing seems unlikely to fulfil the promise of the green world to improve customers’ quality of life or environmental benefit (Chung, Citation2020).

2.2. Sustainable development

Sustainable development has become a central issue in scientific research including agricultural areas. According to Singh (Citation2013), sustainability marketing involves the planning, organization, operation, and control of resources and marketing programs to meet consumers’ needs and demands. Social, economic and environmental attributes are considered to achieve organizational objectives. From this perspective, sustainable marketing is the concept of macro marketing at the beginning of the sustainable development concept that needs to change all participants’ behaviour, including the behaviour of manufacturers and consumers. Moreover, the macro market and sustainable marketing focus on the three basic ecological, social and economic principles and the processes that are integrated by aspiring to live and have a way of life in the community (Ruggerio, Citation2021).

Additionally, Tripathi (Citation2014) defined green marketing as a philosophy that primarily supports sustainable development. Furthermore, the author recognized the importance of peoples concerns for a healthy living environment and choosing eco-friendly products and consumer services (Tripathi, Citation2014). Today, marketers search for opportunities and threats in marketing and study the interference strategies of green marketing to determine whether they would help sustainable improvement (Hossain & Marinova, Citation2013).

2.3. Environmentally friendly products/product image

The United Nations developed 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for people, the planet and prosperity. The environmental subthemes include natural resources (water, energy, agriculture and biodiversity, change and corporate responsibility and accountability) (Johnston, Citation2016). People were more anxious about their daily behaviour and its effect on the environment (Gericke et al., Citation2019). The definition of eco-products is products and services that do not harm and affect the world, result in the loss of life or resources or require recycling. Eco-products are also known as environmentally friendly products or green products (Adrian, Citation1995).

Green products are meaningful in implementing environmental standard laws and policies while designing products to reduce the utilization of resources that could not be renewed and avoid toxic effects. Therefore, these laws and policies are the most productive strategy to achieve green product development. Most companies have also accepted the integration of environmental regulations and laws, such as the initiation of chemical limitations in the green product development process. These regulations and laws can minimize the risks that are harmful to the environment and manufacturers by responding to the expectations of consumers regarding green consumption (Xie et al., Citation2019)

The goal is to influence food safety, labels, and consumers’ perspectives on the consumption of organic foods. As most companies utilize green marketing to modify their business and sell environmentally friendly products, this could decrease production and operating costs to attain long-term profits and environmental sustainability (Ottman et al., Citation2006). Companies can also improve the development of green products to create standards for product alteration and use raw materials that are environmentally friendly, reducing the adverse effects on health and the environment (Tsai et al., Citation2012). Ultimately, companies’ most incredible opportunity to use green marketing is to obtain capital and government loans to develop technology (Ottman, Citation2011).

2.4. Corporate social responsibility (CSR)

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) originated in the 1950s. The definition of CSR is a business operating under the principles of ethics and proper management guided by social and environmental responsibility (Carroll, Citation2009). CSR is a sustainable concept and continues to have more impact and gain more importance (Babiak & Trendafilova, Citation2011). CSR in green marketing refers to producing products and services that are environmentally friendly and reducing environmental impurities to benefit the environment (Tapa & Verma, Citation2014). Peoples behaviour of overspending and irresponsibly using natural resources can impact the environment (Arıkan & Güner, Citation2013). In the concept of sustainable development, profits are no longer a priority. CER or corporate environmental responsibility focuses on daily operations and management for environmental protection, which can be a competitive advantage among firms in legal, social, environmental, low carbon technology, and green management that can increase firm value. (Li et al., Citation2020)

2.5. Hypothesis development

2.5.1. Green marketing and a companys image/reputation

Organic food has become more accessible to people worldwide (Yu et al., Citation2014). At present, consumers emphasize buying premium quality food for their daily lives (Tian & Yu, Citation2013). Fewer chemicals in food have resulted in the growing demand consumers for organic food (Liu et al., Citation2013). Thus, organic food includes safe products consumers are willing to purchase (Liu et al., Citation2013). Green marketing could be a valuable tool to strengthen a corporate image because it shows that a corporation responds to society’s desires. However, the importance of green marketing is to create an excellent corporate image defined by customers (Ko et al., Citation2013). Booms and Bitner (Citation1982) noted that green knowledge could effectively reinforce a brand image and enhance consumers’ satisfaction Nguyen and Leblanc (Citation2001) disclosed that green marketing could positively affect the corporate image. Thus, this current paper hypothesises that green marketing is considered a good ethical decision that could save the earth (N. Nguyen & Leblanc, Citation2001). Furthermore, consumers are increasingly selective and continually assess the prestige of corporations, mistrusting those who try to establish their reputation by “greenwashing”(T. T. H. Nguyen et al., Citation2019).

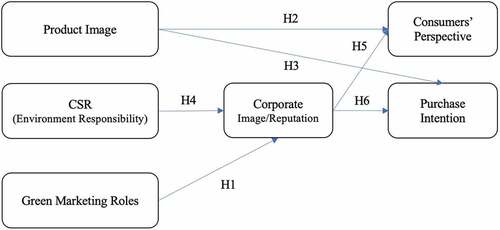

Hypothesis 1: Green marketing has a direct effect on a companys image/reputation.

2.5.2. Product image and the consumers’ perspective

Most people comprehend that organic food is ethical (Canavari et al., Citation2007). Consumers’ attitudes toward product quality depended on the brand image (Grewal et al., Citation1998). Consumers believe that corporate image consists of three factors: corporate image, social responsibility and product image, where product image is related to consumers’ satisfaction and product quality (Ko et al., Citation2013). Consumers’ perception of the country of origin of a product also positively and negatively impacts the perception of a product’s image. However, some consumers have negative opinions and acceptance of green products because consumers are not confident in claims of the safety of green products (European Commission, Citation2013).

Additionally, greenwashing refers to unreal facts and dishonesty and is a reason for consumers’ low confidence. Another reason for the decline in confidence may be the overpromotion of social responsibility (Polonsky, Citation2005). Thus, this misunderstanding has resulted in a lack of confidence in green products. Moreover, this has affected consumers’ purchasing decisions and behaviour towards organic foods (Chrysargyris et al., Citation2017). Given environmental protection and green marketing, eco-labelling could enhance the consumer perspective of a brand, enhance consumer preference, increase purchasing, and greater appreciation for products (Rihn et al., Citation2019; Song et al., Citation2019). Therefore, the critical function of the product image is to influence customers to purchase green products (Riskos et al., Citation2021).

Hypothesis 2: Product image has a direct effect on consumers’ perspectives.

2.5.3. Product image and purchase intention

Consumers are more enthusiastic about brands that are consumer-produced. Therefore, the more eager a customer is regarding a product’s image, the more positive the purchase intention will be (Keller, Citation1993). Cohen (Citation1966) supported that an optimistic consumer perspective towards a particular product would result in a high probability of a consumer purchase. In the case of a green product, word of mouth also has a valuable critical impact on the product’s and company’s image and whether customers buy a product or service (Zahid et al., Citation2018). Consumers preferred to buy organic products certified by agencies; furthermore, purchases would increase if consumers believed in the quality control and organic certification system (Chrysargyris et al., Citation2017). Purchase intention could be predicted by the product image and lead to the consumer avoiding the risk of purchasing (Ramasamy & Yeung, Citation2009).

Two main factors of Thai consumers purchasing organic food were the expected health and safety gain from organic food and the nutritional value of organic food (Goh & Balaji, Citation2016). To motivate purchase intention, companies need to produce high-quality products (Ko et al., Citation2013). However, consumers had an optimistic attitude towards organic food, but some consumers were willing to pay more with a positive attitude towards organic food. Thus, it can be concluded that these consumers are the target companies that should be the focus of marketing strategies (Radman, Citation2005). There are two broad factors for consumers’ purchasing decisions for green products. The first factor is the customer’s awareness of environmental responsibility, including searching for knowledge that can be obtained, self-interest, and the desire to improve the environment. The second factor is the product’s benefits, such as quality, safety, price, and efficiency (Essoussi & Linton, Citation2010).

Hypothesis 3: Product image has a direct effect on purchase intention.

2.5.4. CSR environmental responsibility and corporate image/reputation

CSR is described as a business that has to respond to society, the ecology, consumers, and employees regarding health, product safety and environmental protection (Caruana & Chatzidakis, Citation2014). CSR is also the primary strategy for a business and can motivate consumers to engage in social responsibility (Green & Peloza, Citation2011). Consumers’ attitudes towards green marketing show their awareness of protecting the environment and realizing that to improve their quality of life, they prefer to buy products from socially responsible companies. Consumers thought it was essential for them to protect the environment and buy products from socially responsible companies that could improve the quality of people’s social lives (Čerkasov et al., Citation2017). Environmental responsibility has more importance in business in terms of corporate image/reputation through actions with a strategy that is positively correlated with corporate performance (Famiyeh, Citation2017; Finisterra Do Paço et al., Citation2009; Kardos et al., Citation2019; Ko et al., Citation2013). A corporation with a higher reputation is accepted in business competition (N. Nguyen & Leblanc, Citation2001). Green marketing is an effective strategy that can result in a positive corporate image/reputation and respond to social needs. Consequently, having a good reputation can increase sales from consumers who are sensitive to environmental issues, which would result in increased profits for the firm (Albino et al., Citation2009; Ko et al., Citation2013). However, the impact of CSR initiatives on purchasing would only be theoretical if consumers’ perceptions were low (Khojastehpour & Johns, Citation2014; Ueasangkomsate & Santiteerakul, Citation2016). Hence, in globalization, business firms enter markets with optimal competition, where high-profile companies have embraced corporate social responsibility as a competitive strategy to satisfy the demands of stakeholders (Lii & Lee, Citation2012). Moreover, the company’s reputation improves when they employ social standards to enhance sustainability in their focus community (Islam et al., Citation2021). According to Pino et al. (Citation2016), when realizing a high level of awareness of green marketing efforts as well as CSR of a firm, customers adopt positive attitude toward that company, which in turn generates a more positive image for that brand. A study also indicates that perception of a company’s CSR actions influences consumers’ attitudes and intentions to purchase its goods. The investigation of Tariq et al. (Citation2022) suggests the importance of the total influence of green marketing, CSR policy, and digital marketing on brand development. Moreover, Vu et al. (Citation2021) indicate a positive correlation between environmental CSR programs, attitudes regarding green products, subjective norms, perceived behavioural norms, and green purchase intentions.

Hypothesis 4: Corporate social responsibility (CSR) has a direct effect on corporate image/reputation.

2.5.5. Corporate image/reputation and consumers’ perspective

A corporate image is defined as the information, beliefs, ideas, and perception of an organization (Furman, Citation2010). Besides, a desirable company reputation improves the commitment of customers to a firm. Moreover, the idea of corporate image could represent the identity of a person, goods and a firm, including a service (Balmer et al., Citation2006; Loring, Citation2007). The corporate image is the essential element towards developing and maintaining loyalty (Ishaq et al., Citation2014). It is critical to companies’ success, to maintain their market shares and acquire high benefits to keep clients who support and purchase products due to an excellent company image (Balla & Ibrahim, Citation2014; Ryu et al., Citation2012). Nevertheless, corporate image is formed by utilized experiences with a spiritual, usable product. Evaluating a company’s overall performance would give valued outcomes to stakeholders (Fombrun et al., Citation2000). Customers who support an excellent corporate image would most likely be psychologically pleased because they perceived that such a company gave value for the money. Therefore, customers want to be involved with a company with an excellent corporate image (Tarus et al., Citation2013). Creating an excellent corporate image is the first step to achieving corporate success to attract more consumers. Additionally, an organic brand was the best standard criterion in environmental engagement. A brand’s reputation can be professionally managed and the brand of green products can be well accepted when addressing environmental concerns (Doszhanov et al., Citation2015).

Hypothesis 5: A good corporate image/reputation has a direct effect on consumers’ perspectives.

2.5.6. Corporate Image/reputation and the purchase intention

Purchase intention is the probability of a consumer choosing to purchase green products (Chen, Citation2013). The growth of consumers’ interest in health, nutrition and environmental protection is increasing (Brčić-Stipčević et al., Citation2013).

Corporate image can be improved to be the right image for consumers according to the brand selection probability (Keller, Citation1993). Moreover, many studies have examined the relationship between the images of a company’s services and products and the consumer’s purchase intention (Pomering et al., Citation2009). Developing a company’s image can influence customers’ trust and the consumers’ intention to purchase products (T. S. Lee et al., Citation2016). The corporate image affects customers’ purchase intention; and discovering various elements, such as corporate image, can improve consumers’ purchase intention (Ronaldo et al., Citation2018).

Nevertheless, the confidence of consumers affects the purchase intention in industries. A proper corporate image would increase customers’ loyalty (Herington et al., Citation2006). Moreover, consumers seemed to focus on the quality of products and the environment more than the price. Most consumers believe that companies should reduce pollution rather than increase their profitability (D’Souza et al., Citation2007). Consumers with a firm trust in a company could understand the effectiveness of green marketing. Additionally, a company’s image directly affects a product’s image, which increases purchase intention (Ko et al., Citation2013). A good reputation is a source for the business to survive in a current competitive environment based on a set of beliefs about the ability and willingness to respond to different stakeholders’ interests (Fatima & Ali, Citation2011). Hence, corporate reputation also plays a key role as a mediator between CSR and purchase intention (Tiep et al., Citation2021).

Hypothesis 6: Corporate image/reputation has a direct effect on consumers’ purchase intention.

Figure demonstrates the research model as the hypotheses explained in the literature review.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Sampling and data collection

To test the proposed conceptual framework and hypotheses, the survey questionnaire was used to collect data from customers residing in large cities in five major geographic regions of Thailand, including the north, northeast, south, east and central regions (Vu et al., Citation2021). This research collected primary data by employing a questionnaire. The questions were developed to collect nominal, ordinal and scale data. To test the hypotheses, researchers created an online self-administered survey. The data were collected using a self-reported online survey to reduce the geographic obstacles to reaching respondents. The data were collected from 523 respondents using the purposive convenience sampling method because of the large population but intentionally focusing on green consumers (Burns et al., Citation2019). Green consumers were recruited via social media, including Facebook and email and informed that their information was treated as confidential and that there would be no repeated contact made by the researcher under no circumstances. The self-report survey was used to reduce respondents’ bias caused by the presence of the researcher during the survey, which causes misreporting (Cerri et al., Citation2019). Participation was on a voluntary and confidential basis. All study participants provided their informed consent via survey instructions. Participants were clearly informed that their participation was voluntary, that they could discontinue the survey participation at will, and that their responses were kept confidential and used merely for research purposes. Only completed surveys were used for the analysis process.

The suggested sample size for the structural equation model was determined in several ways. Previous guidelines indicated that the number of respondents per parameter increased from 10 to 15 (Bentler & Bonett, Citation1980; Bentler & Chou, Citation1987; Hair et al., Citation2016) and a sufficient respondent is 10–20 per parameter with a minimum sample size of 200 (Kline, Citation2015). Thus, the appropriate sample size for this research was 360 respondents since the researcher calculated the minimum number based on 18 parameters.

The researcher conducted a pilot test to ensure that the respondents understood the questions in the same way. A pilot test sample has to be 10% of the study’s expected number of samples (Connelly, Citation2008). The researcher intended to collect 500 respondents. Thus, the researcher collected 50 samples for the pilot test in order to reduce data errors. From the results of the 50 respondents, the Cronbach’s alpha, which represents the reliability of the scale, for all constructs in the questionnaire had a score rating between 0.8–0.9 as follows: consumers’ perspective = 0.806, product image = 0.804, the corporate image/reputation = 0.943, purchase intention = 0.920, green marketing = 0.894, and CSR = 0.951. Thus, for the perception measurement part, there were 18 questions, which had an overall Cronbach’s alpha of 0.975. Hence, the researchers concluded that this questionnaire could be used on a full-scale basis.

3.2. Data analysis

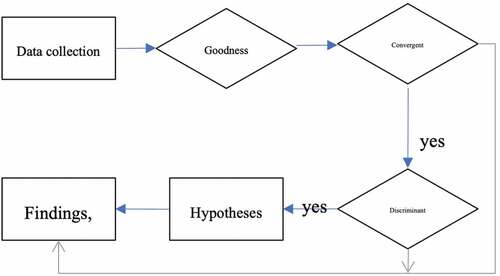

The purpose of this study is to examine predictors of consumers’ attitudes and intentions to purchase green food items. Statistical programs SPSS and AMOS were used to analyse the collected data using two-step methods as shown in and . Firstly, the factors were confirmed using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA); secondly, a structural equation model (SEM) was designed and estimated to test hypotheses regarding the links among the proposed constructs. To analyse the data of this research, the researchers applied structural equation modelling (SEM), which is widely used in consumer research (Ketkaew et al., Citation2021), to perform factor analysis and investigate the interrelationships among variables (Clark, Citation1945; Kahn, Citation2006). The module was designed to analyse the covariance structure, conduct a path analysis and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), test and estimate the causal relationships, and confirm and explore the theory testing and theory building. The software used to analyse the equation model and measure the questions’ reliability, which was an essential element for the survey’s quality, was IBM SPSS (H, Citation2018). IBM Amos 26 was used to conduct the descriptive analysis and analyse the latent variances and the relationships by the SEM to avoid any measurement errors. These software packages were applied to conduct the overall statistical analysis of the research model (Nachtigall et al., Citation2003). The SEM framework was improved to the most recent step to manage any missing data (R. E. R. E. Schumacker & Marcoulides, Citation2009).

3.3. Ethical review

This research paper’s protocol was reviewed and approved to be exempted from full board review by the Ethics Committee for Human Research of Khon Kaen University, No. HE623128.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Demographic information

The respondents were 523 Thai consumers, including 404 females (77.2%) and 119 males (22.8%). Most of the respondents were aged 20–30 years old (60.8%), followed by those aged 31–40 years old (15.7%), 41–50 years old (15.5%), and above 50 years old (8.0%). Most respondents resided in northeastern Thailand (57.4%), followed by central Thailand (19.5%), northern Thailand (9.0%), eastern Thailand (8.0%), and southern Thailand (6.1%). This study indicated that 82.2% of respondents had experience purchasing organic food while 18.3% of respondents had never purchased organic food.

4.2. Confirmatory factor analysis

Table illustrates the goodness of fit indices for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), which is a statistical technique used to test the underlying latent construct and observed variables (Civelek, Citation2018). The criterion indicates that CMIN/DF = 2.858, which should be smaller than 3.0 (Hair et al., Citation2010). The Comparative Fit Index (CFI = 0.976) should be 0.90 or higher for the model to be acceptable model (Bentler, Citation1995; Suhr, Citation2006). Goodness of Fit Index (GFI = 0.931) values should be 0.90 or higher (Biricik Gulseren & Kelloway, Citation2019; Gerbing & Anderson, Citation1988). The Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI = 0.968) and incremental fit index (IFI = 0.975) are good when the values are 0.95 or above (R. R. Schumacker & Lomax, Citation2016; Shi et al., Citation2019). Moreover, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA = 0.060) should be less than 0.08 (MacCallum et al., Citation1996; R. R. Schumacker & Lomax, Citation2016). Therefore, this measurement model passed the criteria.

Table 1. The CFA goodness of fit indices

4.3. Convergent validity

When examining the internal consistency and construct reliability, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) should be higher than 0.5, and the Composite Reliability (C.R.) and Cronbach’s alpha ) should be above 0.7 (Brown, Citation2002; Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Hair et al., Citation2016). Table shows that all indicators’ p-values are less than 0.001; thus, the variables are aligned to their constructs. Additionally, from calculation found that the AVE, C.R. and Cronbach’s alpha

) exceeded the threshold. These results implied that all variables belonged to their latent constructs.

Table 2. Construct validity and reliability

4.4. Discriminant validity

Table presents the discriminant validity matrix between each construct. When the square root of the AVE of those constructs was greater than the squared correlations between the constructs, it could explain the relationship between variables (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). The results demonstrate that all constructs do not overlap, and this measurement model is acceptable.

Table 3. Discriminant validity matrix

4.5. The structural equation model

After certifying that the overall model was agreeable and reasonable, structural equation modelling (SEM) was validated, as shown in Table . The model fit indices for the SEM were acceptable as the chi-squared/degrees of freedom value (CMIN/df) was 2.704, the goodness of fit index (GFI) = 0.939, the comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.977, the parsimony Goodness-of Fit Index (PGFI) = 0.664, the Parsimony Normed Fit Index (PNFI) = 0.762, the incremental fit index (IFI) = 0.977, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.057 (Biricik Gulseren & Kelloway, Citation2019; Hair et al., Citation2016; R. R. Schumacker & Lomax, Citation2016).

Table 4. The SEM goodness of fit indices

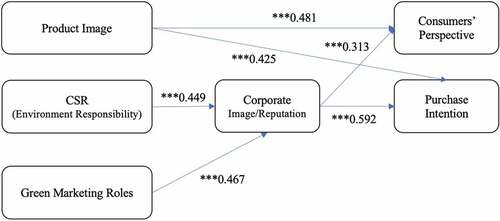

According to the research framework, presents the hypothesis testing results. The regression paths are indicated in Table . It was used to measure the influential relationships between the constructs. The results of the relationship in each hypothesis, the path regression coefficients, the standard path, the critical ratio (t-value), and the probability level (p) are as follows. Hypothesis 1 investigated the green marketing role (GMR), and the results showed that it had a direct effect on corporate image/reputation (CIR) (β = 0.414, t-value = 9.437, p < 0.001). Next, Hypothesis 2 was that the product image (PI) had a direct effect on consumers’ perspective (PER), and the results showed that the hypothesis was supported (β = 0.557, t-value = 8.877, p < 0.001). Additionally, the inspection of Hypothesis 3 indicated that PI had a direct effect on purchase intention (PIN) (β = 0.414, t-value = 9.977, p < 0.001). Then, Hypothesis 4 inquired whether corporate image/reputation (CIR) had a significant influence on consumers’ perspective (ATT), and the results showed that the hypothesis was supported (β = 0.375, t-value = 5.725, p < 0.001). Hypothesis 5 inspected whether corporate image/reputation (CIR) had a positive and significant effect on purchase intention (PIN) (β = 0.597, t-value = 11.857, p < 0.001), and the results showed that H5 was also supported. Finally, Hypothesis 6 investigated the direct effects of corporate social responsibility (CSR) on corporate image/reputation (CIR), and the results showed that the hypothesis was supported (β = 0.404, t-value = 9.041, p < 0.001). Hence, all proposed hypotheses were supported.

Table 5. Regression paths

5. Conclusions and implications

Organic food markets over the world, including Thailand, have been expanding. Green marketing is currently employed as a distinctive selling concept, particularly in food consumption. Customers become more concerned about their health and raised environmental consciousness, thus increasing the consumption of healthy foods. In order to establish a CSR system for the organic food sector, marketers should possess an adequate understanding of the relationship between CSR and consumers’ purchasing intention. Consequently, the purpose of this study is to analyse the interplay between the elements that encourage Thai consumers to purchase organic foods and to evaluate how the green marketing reputation of organic food enterprises affects customers. The results of this research were associated with many previous studies and were contradictory. The results may also support a different perspective and attitude toward organic products in different cultural dimensions.

Firstly, the green marketing role (GMR) had a direct effect on corporate image/reputation (CIR). This empirical research assesses the argument that Thai consumers’ perspective directly affects corporate image/reputation (N. Nguyen & Leblanc, Citation2001b). However, the results concurred with the evidence that corporate image/reputation directly affected Thai consumers’ perspective (Karaosmanoglu & Melewar, Citation2006; Keller, Citation1993; N. Nguyen & Leblanc, Citation1998; Wallin Andreassen & Lindestad, Citation1998). Therefore, Thai consumers perceived how a company acted. If the company acted positively, consumers would admire the company and have an attitude as intended (Booms & Bitner, Citation1982; Ko et al., Citation2013; N. Nguyen & Leblanc, Citation2001). Also, PI had a direct effect on consumers’ perspective (PER), and purchase intention (PIN). The research suggests that a product with a certificate that is well-defined as safe and environmentally friendly can ensure that consumers will be more confident with the product (Chrysargyris et al., Citation2017; Zahid et al., Citation2018).

Moreover, this research found that corporate image/reputation (CIR) had a significant influence on consumers’ perspective (ATT) and purchase intention (PIN). According to previous research, greenwashing leads to consumer distrust as the corporate overly promotes itself to bear social responsibilities (Polonsky, Citation2005b). CSR becomes theoretically effective only if customers possess limited understanding (Khojastehpour & Johns, Citation2014; Ueasangkomsate & Santiteerakul, Citation2016). Based on the interpretation of the findings of Thai consumers’ purchase intention towards organic foods, the study found that the most significant factor is a corporate image, which leads to purchase intention and can be boosted by green marketing and corporate social responsibility (CSR) as the primary strategy (Green & Peloza, Citation2011) including raising social consciousness and increasing the quality of social life of people (Čerkasov et al., Citation2017). Nevertheless, the product image is another factor that concerns consumers when making a purchase decision (Essoussi & Linton, Citation2010; Goh & Balaji, Citation2016).

The factors affecting Thai consumers’ perspective and purchase intention toward organic food included green marketing, product image, corporate image/reputation, and corporate social responsibility. Consumer interest in well-being, diet and conservation of the environment is growing (Brčić-Stipčević et al., Citation2013). The best quality environmental participation criteria was an ecological brand. The credibility of a company can be handled properly and renewable goods can be embraced when dealing with environmental issues (Doszhanov et al., Citation2015).

Our findings are consistent with the literature which asserts that the green marketing role (GMR) is a crucial factor in business image/reputation (CIR). In addition, the empirical findings imply that product image (PI) may have a significant effect on customers’ perceptions (PER) and purchase intentions (PIN). The current findings suggested that corporate image/reputation (CIR) play an influential cause in consumers’ perspective (ATT) and purchase intention (PIN). Lastly, corporate social responsibility (CSR) has a cumulative impact on corporate image and reputation (CIR). Consistent with prior research, this study found that organizations should consider green marketing role (GMR), corporate image/reputation (CIR), and corporate social responsibility (CSR) in order to increase customer intention to purchase green products. Therefore, the future study may combine green marketing role (GMR), corporate image/reputation (CIR), and corporate social responsibility (CSR) in conjunction with other marketing and product components to increase understanding of green business.

The findings of this study would be beneficial for green businesses interested in pursuing sustainability and growth. Due to environmental problems, such as global warming, nonbiodegradable solid waste, and the harmful impacts of pollutants, green marketing was initiated by the U.N. to protect the environment. Green marketing can benefit green businesses that would need to pursue sustainability and growth by giving green knowledge to consumers directly or establishing corporate social responsibility (CSR) towards sustainable development goals. In addition, buyers seemed to rely on product content and climate rather than products (D’Souza et al., Citation2007). Hence, the study could be utilized to improve strategic marketing efficiency by considering purchase intention.

In addition, the present study enhances our understanding of the green marketing role (GMR), corporate image/reputation (CIR), and corporate social responsibility (CSR) on social and environmental performance. The current study also provides evidence of more efficient use of energy and natural resources to increase productivity and profitability. CSR may foster an innovation culture that contributes to new business models, products, services, and processes through the use of social, environmental, and sustainability controllers. Indeed, CSR can increase firm-level and supply-chain productivity, and eventually, the benefits may trickle down into the host community.

In the future, the certificate of a green company or product should be made available to ensure its reliability. One of the potential barriers to consumers purchasing organic products is a lack of consumer confidence in the statement that products are free from chemical synthesis. Indeed, recently there have been reports of chemical use (e.g., pesticide, insecticide) among Thai farmers

Using chemicals in agricultural production may pose a considerable risk to not only consumers but farmers themselves; furthermore, when left, the chemical composition is found to harm the environment. It is, therefore, necessary that Thai people be provided with essential knowledge and accurate perceptions about organic food so as to encourage the consumption of organic food, support green marketing and eventually preserve the environment.

6. Limitations and recommendation for future research

The current study is limited by the data collection and generalization to other green consumers. However, it could be argued from the study that the subject sampling method by online tools could facilitate researchers to recruit target groups.

This study has focused on CSR practices in Thailand’s organic food industry. Further research could investigate the causal linkages between CSR, green marketing, and a company’s image/reputation in the context of other industries. This study introduced a theoretical approach by examining the impact of business image/reputation on consumers’ purchasing intention in developing economies.

The findings suggest that in general customers believe that organic foods contain less chemical compositions in relation to other kinds of food, suggesting that they remain uncertain whether to consume or to spend higher prices on organic food. Thus, future research is needed to study the feasibility of certifying a company or products green as well as investigate factors influencing Thai consumers’ purchase intention. In particular, future research is needed to better understand environmentally conscious consumers in relation to their lifestyles and specific demographics (Famiyeh, Citation2017; Finisterra Do Paço et al., Citation2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate Khon Kaen University International College, to sponsor and provide research facilities. The author also would like to thank Punika Wisetkeaw, Phattharanit Rotamorncharoen and Natticha Pholrom as their tole of research assistant. The authors declare no potential conflict of interest related to this work

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lakkana Hengboriboon

Lakkana Hengboriboon is a lecturer in the Business Division at Khon Kaen University International College. Her teaching areas are Organization Behavior, Consumer Behavior and Business Ethics and Customer Relationship Management. She is a first author of this study.

Phaninee Naruetharadol

Phaninee Naruetharadol is an assistant professor in Management at Khon Kaen University International College. She also specializes in Finance and Organization Behavior by her teaching areas. Her research interests are Organizational Behavior, Innovation Management, and Financial Planning shown at her ongoing research.

Chavis Ketkeaw

Chavis Ketkeaw is an assistant professor of management at the International College, Khon Kaen University, Thailand. His research interests include business management, behavioral economics, consumer research, market research, and business models.

Nathatenee Gebsombut

Nathathenee Gebsombat is a lecturer in International College, Khon Kaen University (KKUIC). Her current research interests include customer relationship management, e-business management and technology adoption. She is a corresponding author of this research project.

References

- Adrian, M., Richard, M. D. (1995). An examination of purchase behavior versus purchase attitudes for environmentally friendly and recycled consumer goods.Southern Business Review, 21(1), 1–20.

- Akbari, M., Ardekani, Z. F., Pino, G., & Maleksaeidi, H. (2019). An extended model of theory of planned behavior to investigate highly-educated Iranian consumers’ intentions towards consuming genetically modified foods. Journal of Cleaner Production, 227, 784–793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.246

- Albino, V., Balice, A., & Dangelico, R. M. (2009). Environmental strategies and green product development: An overview on sustainability-driven companies. Business Strategy and the Environment, 18(2), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.638

- Ali, I, & Ali, J. F. (2011). Corporate social responsibility, corporate reputation and employee engagement,MPRA Paper 33891. University Library of Munich, Germany.

- Arıkan, E., & Güner, S. (2013). The impact of corporate social responsibility, service quality and customer-company identification on customers. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 99, 304–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.498

- Aungatichart, N., Fukushige, A., & Aryupong, M. ((2020). Mediating role of consumer identity between factors influencing purchase intention and actual behavior in organic food consumption in Thailand. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences, 2020(2). http://hdl.handle.net/10419/222909

- Babiak, K., & Trendafilova, S. (2011). CSR and environmental responsibility: Motives and pressures to adopt green management practices. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 18(1), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.229

- Balla, B. E., & Ibrahim, S. B. (2014). Impact of Corporate Brand on Customer ’ s Attitude towards Repurchase Intention. International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR), 3(11), 2384–2388. https://www.ijsr.net/archive/v3i11/T0NUMTQxNTU3.pdf

- Balmer, J. M. T., Greyser, S. A., & Balmer, J. M. T. (2006). Corporate marketing: Integrating corporate identity, corporate branding, corporate communications, corporate image and corporate reputation. European Journal of Marketing, 40(7–8), 730–741. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560610669964

- Bennett, P.D. (1995). AMA Dictionary of Marketing Terms (Vol. 2) (pp. 336). McGraw-Hill.

- Bentler, P. M. (1995). EQS 6 structural equations program manual. In Los angeles: BMDP statistic software (pp. 86–102). Multivariate Software, Inc.

- Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588–606. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588

- Bentler, P. M., & Chou, C. P. (1987). Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological Methods & Research, 16(1), 78–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124187016001004

- Biricik Gulseren, D., & Kelloway, K. (2019). Structural equation modelling Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T.K.Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences. Springer.

- Booms, B. H., & Bitner, M. J. (1982). marketing services by managing the environment. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 23(1), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/001088048202300107

- Brčić-Stipčević, V., Petljak, K., & Guszak, I. (2013). Organic food consumers purchase patterns - Insights from Croatian market. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 4(11), 472–480. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2013.v4n11p472

- Brown, J. D. (2002). The Cronbach alpha reliability estimate. Shiken: JALT Testing & Evaluation SIG Newsletter, 6(1), 17–18. https://hosted.jalt.org/test/bro_13.htm

- Burns, A. C., Bush, R. F., & Veeck, A. (2019). Marketing Research. Pearson Education.

- Canavari, M., Centonze, R., & Nigro, G. (2007). Organic food marketing and distribution in the European Union. Agribusiness, 3(July). https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.9077

- Carroll, A. B. (2009). A History of corporate social responsibility: Concepts and practices. In Andrew C., Abigail, M., Dirk, M., Jeremy, M. & Donald, S. (eds.) The oxford handbook of corporate social responsibility (pp. 19-46).Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199211593.003.0002

- Caruana, R., & Chatzidakis, A. (2014). Consumer social responsibility (CnSR): Toward a multi-level, multi-agent conceptualization of the “Other CSR.”. Journal of Business Ethics, 121(4), 577–592. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1739-6

- Čerkasov, J., Huml, J., Vokačova, L., & Margarisova, K. (2017). Consumer’s attitudes to corporate social responsibility and green marketing. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis, 65(6), 1865–1872. https://doi.org/10.11118/actaun201765061865

- Cerri, J., Testa, F., Rizzi, F., & Frey, M. (2019). Factorial surveys reveal social desirability bias over self-reported organic fruit consumption. British Food Journal, 121(4), 897–909. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-04-2018-0238

- Chen, L. (2013). A study of green purchase intention comparing with collectivistic (Chinese) and individualistic (American) consumers in Shanghai, China. Information Management and Business Review, 5(7), 342–346. https://doi.org/10.22610/imbr.v5i7.1061

- Christis, J., & Wang, Y. (2021). Communicating environmental CSR towards consumers: The impact of message content, message style and praise tactics. Sustainability, 13(7), 3981. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073981

- Chrysargyris, A., Xylia, P., Kontos, Y., Ntoulaptsi, M., & Tzortzakis, N. (2017). Consumer behavior and knowledge on organic vegetables in Cyprus. Food Research, 1(2), 57–65. https://doi.org/10.26656/fr.2017.2.009

- Chung, K. C. (2020). Green marketing orientation: Achieving sustainable development in green hotel management. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 29(6), 722–738. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2020.1693471

- Civelek, M. E. (2018). Essentials of structural equation modeling. Zea Books. https://doi.org/10.13014/k2sj1hr5

- Clark, J. T. (1945). Methodology of the social sciences. Thought, 20(1), 185–188. https://doi.org/10.5840/thought194520147

- Cohen, L. (1966). The level of consciousness: A dynamic approach to the recall technique. Journal of Marketing Research, 3(2), 142. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150202

- Connelly, L. M. (2008). Research roundtable: Pilot studies. Medsurg Nursing, 17(6), 411–412. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/pilot-studies/docview/230525260/se-2

- Domazet, I., Stošić, I., & Hanić, A. (2016). New technologies aimed at improving the competitiveness of companies in the services sector. Europe and Asia: economic integration prospects (pp. 363–377). CEMAFI International. 979-10-96557-02-8. https://ebooks.ien.bg.ac.rs/1036/

- Doszhanov, A., Ahmad, Z. A., Rainis, R., Bin Abu Bakar, M. N., & Ezuer Shafii, J. (2015). Customers’ intention to use green products: The impact of green brand dimensions and green perceived value. SHS Web of Conferences, 18(2012), 01008. https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20151801008

- D’Souza, C., Taghian, M., & Khosla, R. (2007). Examination of environmental beliefs and its impact on the influence of price, quality and demographic characteristics with respect to green purchase intention. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 15(2), 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jt.5750039

- Essoussi, L. H., & Linton, J. D. (2010). New or recycled products: How much are consumers willing to pay? Journal of Consumer Marketing, 27(5), 458–468. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761011063358

- European Commission. (2013). Attitudes of Europeans towards building the single market for green products. Flash Eurobarometer, 367, 1–13. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/1048

- Famiyeh, S. (2017). Corporate social responsibility and firm’s performance: Empirical evidence. Social Responsibility Journal, 13(2), 390–406. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-04-2016-0049

- Fombrun, C. J., Gardberg, N. A., & Sever, J. M. (2000). The reputation QuotientSM: A multi-stakeholder measure of corporate reputation. Journal of Brand Management, 7(4), 241–255. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2000.10

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

- Furman, D. M. (2010). The development of corporate image: A historiographic approach to a marketing concept. Corporate Reputation Review, 13(1), 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1057/crr.2010.3

- Gerbing, D. W., & Anderson, J. C. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Gericke, N., Boeve-de Pauw, J., Berglund, T., & Olsson, D. (2019). The sustainability consciousness questionnaire: The theoretical development and empirical validation of an evaluation instrument for stakeholders working with sustainable development. Sustainable Development, 27(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1859

- Goh, S. K., & Balaji, M. S. (2016). Linking green skepticism to green purchase behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production, 131(June), 629–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.04.122

- Green, T., & Peloza, J. (2011). How does corporate social responsibility create value for consumers? Journal of Consumer Marketing, 28(1), 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761111101949

- Grewal, D., Krishnan, R., Baker, J., & Borin, N. (1998). The effect of store name, brand name and price discounts on consumers’ evaluations and purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing, 74(3), 331–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(99)80099-2

- H, T. (2018). Validity and reliability of the research instrument; how to test the validation of a questionnaire/survey in a research. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3205040

- Hair, J., Anderson, R., Black, B., & Babin, B. (2016). Multivariate data analysis. Pearson Education.

- Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (pp. 800). Pearson Education.

- Han, S.-L., & Lee, J. W. (2021). Does corporate social responsibility matter even in the B2B market?: Effect of B2B CSR on customer trust. Industrial Marketing Management, 93, 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.12.008

- Herington, C., Johnson, L. W., & Scott, D. (2006). Internal relationships: Linking practitioner literature and relationship marketing theory. European Business Review, 18(5), 364–381. https://doi.org/10.1108/09555340610686958

- Hossain, A., & Marinova, D. (2013). Transformational marketing: Linking marketing and sustainability. World Journal of Social Sciences, 3(3), 189–196. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11937/36397

- Ishaq, M. I., Bhutta, M. H., Hamayun, A. A., Danish, R. Q., & Hussain, N. M. (2014). Role of corporate image, product quality and customer value in customer loyalty: Intervening effect of customer satisfaction. Journal of Basic and Applied Scientific Research, 4(4), 89–97. https://www.textroad.com/pdf/JBASR/J.%20Basic.%20Appl.%20Sci.%20Res.,%204(4)89-97,%202014.pdf

- Islam, T., Islam, R., Pitafi, A. H., Xiaobei, L., Rehmani, M., Irfan, M., & Mubarak, M. S. (2021). The impact of corporate social responsibility on customer loyalty: The mediating role of corporate reputation, customer satisfaction, and trust. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 25, 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2020.07.019

- Janssen, B. (2010). Local food, local engagement: Community-supported agriculture in eastern Iowa. Culture & Agriculture, 32(1), 4–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-486x.2010.01031.x

- Jitrawang, P., & Krairit, D. (2019). Factors influencing purchase intention of organic rice in Thailand. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 25(8), 805–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/10454446.2019.1679690

- Jiumpanyarach, W. (2018). The impact of social trends: Teenagers’ attitudes for organic food market in Thailand. International Journal of Social Economics, 45(4), 682–699. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijse-01-2017-0004

- Johnston, R. B. (2016). Arsenic and the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development. Arsenic Research and Global Sustainability - Proceedings of the 6th International Congress on Arsenic in the Environment, AS 2016. June 19-23, 2016. 12–14. Stockholm, Sweden. https://www.routledge.com/Arsenic-Research-and-Global-Sustainability-Proceedings-of-the-Sixth-International/Bhattacharya-Vahter-Jarsjo-Kumpiene-Ahmad-Sparrenbom-Jacks-Donselaar-Bundschuh-Naidu/p/book/9780367737054

- Kahn, J. H. (2006). Factor analysis in counseling psychology research, training, and practice: Principles, advances, and applications. The Counseling Psychologist, 34(5), 684–718. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006286347

- Karaosmanoglu, E., & Melewar, T. C. (2006). Corporate communications, identity and image: A research agenda. Journal of Brand Management, 14(1–2), 196–206. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2550060

- Kardos, M., Gabor, M. R., & Cristache, N. (2019). Green marketing’s roles in sustainability and ecopreneurship. case study: Green packaging’s impact on Romanian young consumers’ environmental responsibility. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030873

- Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299305700101

- Ketkaew, C., Wongthahan, P., & Sae-Eaw, A. (2021). How sauce color affects consumer emotional response and purchase intention: A structural equation modeling approach for sensory analysis. British Food Journal, 123(6), 2152–2169. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-07-2020-0578

- Khattak, A. (2019). Green innovation in south Asia’s clothing industry: Issues and challenges. In Paladini, S. & George, S. (Eds.), Sustainable economy and emerging markets (pp. 172–183). https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10 .4324/9780429325144-11/green-innovation-south-asia-clothing-industry-amira-khattak

- Khojastehpour, M., & Johns, R. (2014). The effect of environmental CSR issues on corporate/brand reputation and corporate profitability. European Business Review, 26(4), 330–339. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-03-2014-0029

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications.

- Ko, E., Hwang, Y. K., & Kim, E. Y. (2013). Green marketing’ functions in building corporate image in the retail setting. Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 1709–1715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.11.007

- Lee, Y. K. (2020). The relationship between green country image, green trust, and purchase intention of Korean products: Focusing on Vietnamese Gen Z consumers. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125098

- Lee, T. S., Ariff, M. S., Zakuan, N., & Sulaiman, Z. (2016). Assessing website quality affecting online purchase intention of Malaysia ’ s young consumers. Advanced Science, Engineering and Medicine, 8(10), 836–840. https://doi.org/10.1166/asem.2016.1937

- Lii, Y. S., & Lee, M. (2012). Doing right leads to doing well: When the type of CSR and reputation interact to affect consumer evaluations of the firm. Journal of Business Ethics, 105(1), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0948-0

- Li, Z., Liao, G., & Albitar, K. (2020). Does corporate environmental responsibility engagement affect firm value? The mediating role of corporate innovation. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(3), 1045–1055. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2416

- Liu, R., Pieniak, Z., & Verbeke, W. (2013). Consumers’ attitudes and behaviour towards safe food in China: A review. Food Control, 33(1), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.01.051

- Loring, J. (2007). Variations on a green. Architectural Digest, 64(6), 100–113. https://archive.architecturaldigest.com/article/2007/6/variations-on-a-green

- MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130

- McDaniel, S. W., & Rylander, D. H. (1993). Strategic green marketing. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 10(3), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363769310041929

- McWilliams, A., Siegel, D. S., Barney, J. B., Ketchen, D. J., & Wright, M. (2011). Creating and capturing value: Strategic corporate social responsibility, resource-based theory, and sustainable competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 37(5), 1480–1495. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310385696

- Mohamad, S. S., Rusdi, S. D., & Hashim, N. H. (2014). Organic food consumption among Urban consumers: Preliminary results. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 130, 509–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.04.059

- Munerah, S., Koay, K. Y., & Thambiah, S. (2021). Factors influencing non-green consumers’ purchase intention: A partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 280, 124192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124192

- Nachtigall, C., Kroehne, U., Funke, F., & Steyer, R. (2003). (Why) should we use SEM? Pros and cons of structural equation modeling. Methods of Psychological Research, 8(2), 1–22. http://www.dgps.de/fachgruppen/methoden/mpr-online/issue20/art1/mpr127_11.pdf

- Nguyen, N., & Leblanc, G. (1998). The mediating role of corporate image on customers’ retention decisions: An investigation in financial services. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 16(2), 52–65. https://doi.org/10.1108/02652329810206707

- Nguyen, N., & Leblanc, G. (2001). Corporate image and corporate reputation in customers’ retention decisions in services. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 8(4), 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0969-6989(00)00029-1

- Nguyen, T. T. H., Yang, Z., Nguyen, N., Johnson, L. W., & Cao, T. K. (2019). Greenwash and green purchase intention: The mediating role of green skepticism. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/su11092653

- Ottman, J. A. (2011). Green is now mainstream. In The new rules of green marketing: Strategies, tools, and inspiration for sustainable branding (pp. 1–21). Greenleaf Publishing. https://www.routledge.com/The-New-Rules-of-Green-Marketing-Strategies-Tools-and-Inspiration-for/Ottman/p/book/9781906093440

- Ottman, J. A., Stafford, E. R., & Hartman, C. L. (2006). Avoiding green marketing myopia: Ways to improve consumer appeal for environmentally preferable products. Environment, 48(5), 22–36. https://doi.org/10.3200/ENVT.48.5.22-36

- Paço, F. D., Barata Raposo, A. M., L, M., & Filho, W. L. (2009). Identifying the green consumer: A segmentation study. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 17(1), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1057/jt.2008.28

- Pino, G., Amatulli, C., de Angelis, M., & Peluso, A. M. (2016). The influence of corporate social responsibility on consumers’ attitudes and intentions toward genetically modified foods: Evidence from Italy. Journal of Cleaner Production, 112, 2861–2869. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2015.10.008

- Polonsky, M. J. (2005). Building A corporate socially responsible brand: An investigation of issue complexity Michael Jay Polonsky, Victoria university Colin Jevons, Monash university.

- Pomering, A., Johnson, L. W., & Balmer, J. M. T. (2009). Advertising corporate social responsibility initiatives to communicate corporate image: Inhibiting scepticism to enhance persuasion. Corporate Communications, 14(4), 420–439. https://doi.org/10.1108/13563280910998763

- Poungchompu, S., Tsuneo, K., & Pungchumpu, P. (2012). Aspects of the aging farming population and food security in agriculture for Thailand and Japan. International Journal of Environmental and Rural Development, 3(1), 102–107. http://iserd.net/ijerd31/31102.pdf

- Pracharuengwit, P., & Chiaravutthi, Y. (2015). Consumer willingness to pay for organic food in Thailand: Evidence from the random nth-price auction experiment. Bus Adm J, 146, 52–70. http://www.jba.tbs.tu.ac.th/files/Jba146/Article/JBA146PeeYing.pdf

- Pujari, D., & Wright, G. (1996). Developing environmentally conscious product strategies: A qualitative study of selected companies in Germany and Britain. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 14(1), 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634509610106205

- Radman, M. (2005). Consumer consumption and perception of organic products in Croatia. British Food Journal, 107(4), 263–273. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070700510589530

- Rahbar, E., & Wahid, N. A. (2011). Investigation of green marketing tools‘ effect on consumers‘ purchase behavior. Business Strategy Series, 12(2), 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1108/17515631111114877

- Rajadurai, J., Zahari, A. R., Esa, E., Bathmanathan, V., & Ishak, N. A. M. (2021). Investigating green marketing orientation practices among green small and medium enterprises. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 8(1), 407–417. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2021.vol8.no1.407

- Ramasamy, B., & Yeung, M. (2009). Chinese consumers’ perception of corporate social responsibility (CSR). Journal of Business Ethics, 88(SUPPL. 1), 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9825-x

- Rihn, A., Wei, X., & Khachatryan, H. (2019). Text vs. logo: Does eco-label format influence consumers’ visual attention and willingness-to-pay for fruit plants? An experimental auction approach. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 82, 101452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2019.101452

- Riskos, K., Dekoulou, P., Mylonas, N., & Tsourvakas, G. (2021). Ecolabels and the attitude–behavior relationship towards green product purchase: A multiple mediation model. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126867

- Ronaldo, R., Maulina, E., Alexandri, M. B., Purnomo, M., Fadoli, & Yulmaulini. (2018). Corporate image on purchase intention, mediated by trust and commitment on the loss insurance industry in Indonesia. International Journal of Management and Business Research, 8(3), 142–153. http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-85060762818&partnerID=MN8TOARS

- Ruggerio, C. A. (2021). Sustainability and sustainable development: A review of principles and definitions. In Science of the total environment (Vol. 786) (pp. 147481). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147481

- Ryu, K., Lee, H. R., & Kim, W. G. (2012). The influence of the quality of the physical environment, food, and service on restaurant image, customer perceived value, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intentions. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 24(2), 200–223. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596111211206141

- Schumacker, R., & Lomax, R. (2016). . In A Beginner's Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, 4th Ed (pp. 394). Routledge. 9781138811935. https://www.routledge.com/A-Beginners-Guide-to-Structural-Equation-Modeling-Fourth-Edition/Schumacker-Lomax/p/book/9781138811935

- Schumacker, R. E., & Marcoulides, G. A. (2009). Structural equation modeling : A multidisciplinary journal book review of interaction and nonlinear effects in structural equation. Online, 773566367, 37–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0803

- Sedky, D., & AbdelRaheem, M. A. (2022). Studying green marketing in emerging economies. Business Strategy & Development, 5(1), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsd2.183

- Shi, D., Lee, T., & Maydeu-Olivares, A. (2019). Understanding the model size effect on SEM Fit Indices. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 79(2), 310–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164418783530

- Singh, G. (2013). Green: The new colour of marketing in India. ASCI Journal of Management, 42(2), 52–72. https://fdocuments.us/document/green-the-new-colour-of-marketing-in-india.html?page=1

- Sitthisuntikul, K., Yossuck, P., & Limnirankul, B. (2018). How does organic agriculture contribute to food security of small land holders ?: A case study in the north of Thailand how does organic agriculture contribute to food security of small land holders ?: A case study in the North of Thailand. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 28(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2018.1429698

- Smith, S., & Paladino, A. (2010). Eating clean and green? Investigating consumer motivations towards the purchase of organic food. Australasian Marketing Journal, 18(2), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2010.01.001

- Song, Y., Qin, Z., & Yuan, Q. (2019). The impact of eco-label on the young Chinese generation: The mediation role of environmental awareness and product attributes in green purchase. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/su11040973

- Suhr, D. D. (2006). Exploratory or confirmatory factor analysis? SUGI 31, March 26-29, 2006, San Francisco, California, 200–31. https://support.sas.com/resources/papers/proceedings/proceedings/sugi31/200-31.pdf

- Tariq, E., Alshurideh, M., Akour, I., Al-Hawary, S., & Kurdi, B. (2022). The role of digital marketing, CSR policy and green marketing in brand development. International Journal of Data and Network Science, 6(3), 995–1004. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.ijdns.2022.1.012

- Tarus, D. K., Rabach, N., & Muturi and Jackline Sagwe, D. (2013). Determinants of customer loyalty in Kenya: Does corporate image play a moderating role? The TQM Journal, 25(5), 473–491. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-11-2012-0102

- Thapa, S., & Verma, S. (2014). Analysis of green marketing as environment protection tool: A study of consumer of Dehradun. International Journal of Research in Commerce and Management, 5(9), 78–84. https://ijrcm.org.in/article_info.php?article_id=4795&fbclid=IwAR34M94okpd5b8t0Z9yUqzzqslLYtiM7yhox5MK7tGO4ojUeX9ODWiD51XQ

- Tian, X., & Yu, X. (2013). The demand for nutrients in China. Frontiers of Economics in China, 8(2), 186–206. https://doi.org/10.3868/s060-002-013-0009-9

- Tiep, L. T., Huan, N. Q., & Hong, T. T. T. (2021). Effects of corporate social responsibility on SMEs’ performance in emerging market. Cogent Business and Management, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1878978

- Tripathi, N. K. (2014). Improving sustainability through green marketing. International Research Journal of Management Science & Technology, 5(12), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.32804/IRJMST

- Tsai, M. T., Chuang, L. M., Chao, S. T., & Chang, H. P. (2012). The effects assessment of firm environmental strategy and customer environmental conscious on green product development. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 184(7), 4435–4447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-011-2275-4

- Tulsi, P., & Ji, Y. (2020). A conceptual approach to green human resource management and corporate environmental responsibility in the hospitality industry. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7(1), 195–203. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no1.195

- Ueasangkomsate, P., & Santiteerakul, S. (2016). A study of consumers’ attitudes and intention to buy organic foods for sustainability. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 34, 423–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2016.04.037

- Vu, D. M., Ha, N. T., Ngo, T. V. N., Pham, H. T., & Duong, C. D. (2021). Environmental corporate social responsibility initiatives and green purchase intention: An application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Social Responsibility Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-06-2021-0220

- Wallin Andreassen, T., & Lindestad, B. (1998). Customer loyalty and complex services. The impact of corporate image on quality, customer satisfaction and loyalty for customers with varying degrees of service expertise. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 9(1), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564239810199923

- Willer, H., Trávníček, J., Meier, C., & Schlatter, B. (2021). The world of organic agriculture 2021-statistics and emerging trends. Research Institute of Organic Agriculture FiBL and IFOAM. 978-3-03736-393-5. https://www.organic-world.net/yearbook/yearbook-2021.html

- Xie, X., Huo, J., & Zou, H. (2019). Green process innovation, green product innovation, and corporate financial performance: A content analysis method. Journal of Business Research, 101(January), 697–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.01.010

- Yanakittkul, P., & Aungvaravong, C. (2020). A model of farmers intentions towards organic farming: A case study on rice farming in Thailand. Heliyon, 6(1), e03039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e03039

- Yazdanifard, Rashad, & Mercy, Igbazua Erdoo (2011). The impact of green marketing on customer satisfaction and Envi- ronmental safety. International Conference on Computer Communication and Management, May 2-3 2011, 5, 637–641. Sydney, Australia.

- Yu, X., Gao, Z., & Zeng, Y. (2014). Willingness to pay for the “Green Food” in China. Food Policy, 45, 80–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.01.003

- Zahid, M. M., Ali, B., Ahmad, M. S., Thurasamy, R., & Amin, N. (2018). Factors affecting purchase intention and social media publicity of green products: The mediating role of concern for consequences. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 25(3), 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1450