?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the non-linear relationship between working capital management (WCM) and firm profitability (FP). As well as checking whether there is a financial leverage threshold in the decision on working capital, thereby assessing the change in the impact of working capital on corporate profits with a defined threshold. Through panel data of 405 enterprises listed on the Vietnam stock exchange in the period from 2010 to 2020, compiled by Thomson Reuters (2021), The study uses Hansen’s (1999) threshold estimate (fixed-effects panel threshold model) to determine the threshold and estimate the model’s parameters. Research results have been found: (i) there exists a non-linear relationship be tween working capital management and corporate profitability; and (ii) at a certain percentage of the debt coefficient (Impact Threshold), the variables representing working capital management all have a negative impact on the profitability of the firm. In this relationship, there are different effects of the proxies of Working Capital Management before and after the threshold, and specifically, the impact values of these proxies are higher after the threshold. This implies that tighter working capital management depends on the profitability of the business. This is the first study to clarify the effect of working capital in terms of the capital structure of enterprises. At a certain leverage threshold, the business will decide to optimize the appropriate working capital management to improve profitability.

1. Introduction

Working capital management is highly relevant to a firm’s success. There have been many studies to evaluate the effect of working capital on corporate profitability (Jose et al., Citation1996; H.-H. Shin & Soenen, Citation1998; Wang, Citation2000; Deloof, Citation2003; Lazaridis and Tryfonidis, Citation2006; Meyer and Ludtke, 2006; Garcia-Teruel & Martinez-Solano, Citation2007; Raheman and Nasr, Citation2007; Karadumen et al., Citation2010; Baños-Caballero et al., Citation2012; J. Enqvist et al., Citation2014). In addition to the relationship considered, the capital structure decision is crucial for any business organization. The decision is important because of the need to maximize returns to various organizational constituencies, and also because of the impact such a decision has on a firm’s ability to deal with its competitive environment. The capital structure of a firm is actually a mix of different securities. Generally, an enterprise may choose between many other capital structures. It can issue a large amount of debt or very little debt. It may organise leasing, use warrants, issue convertible bonds, sign forward contracts or exchange bonds. It can issue dozens of distinct securities in countless combinations. However, it attempts to find the particular combination that maximizes its overall corporate profit. The studies also show that financial leverage has an influence on firm profitability. This is also found in multiple existing studies (Mahmood et al., Citation2019; Fazzari & Petersen, Citation1993; Einarsson & Marquis, Citation2001; Hill et al., Citation2010; J. Enqvist et al., Citation2014; De Almeida & Eid, Citation2014; Pakistan Interest Rate, Citation2016; Alam, 2015; Khan, Citation2015; Zaidi, Citation2015; Baos-Caballero et al., Citation2014; Khan, Citation2015). What is primarily reported is that, depending on the operating characteristics of the business with specific financial structures, the enterprise will decide the appropriate source of working capital to improve its profits.

However, the empirical evidence on the relationship between working capital and business performance is quite mixed. On the other hand, investments in working capital are believed to have a positive effect on a company’s bottom line as they support growth in sales and earnings (Aktas et al., Citation2015; Sonia et al., Citation2020). Sales are positively influenced by trade credit, improving relationships with customers while holding more inventory to protect the business from price fluctuations. Furthermore, the short-term debt used to finance working capital has a low interest rate and is unaffected by inflation risk (Mahmood et al., Citation2019). On the other hand, overinvestment in working capital requires financial viability and will incur additional costs and can create adverse effects and financial losses for shareholders (Aktas et al., Citation2015; Chen & Kieschnick, Citation2018). As a result, the rapidly increasing cost of working capital investments relative to the benefits of holding larger inventories or allowing the use of trade credit to customers will reduce a firm’s profitability.

Several studies have suggested that there is a non-linear relationship between working capital investment and firm profitability (Mahmood et al., Citation2019; Tsuruta, Citation2018; Anton et al. Citation2021; Aktas et al., Citation2015; Mun & Jang, Citation2015; Baños-Caballero et al., Citation2014). The non-linear relationship assumes that working capital investments have a positive effect on a firm’s profitability up to a certain point in time, known as the working capital optimum (or break point). Above optimal, working capital can be a negative determinant of firm performance. The positive and negative association with the break-even point in this relationship forms an inverted U-shape (Baños-Caballero et al. Citation2012, Anton & Elena Afloarei Nucu, Citation2021; Mahmood et al., Citation2019).

Previous research on the non-linear relationship between WCM and FP, such as Anton and Elena Afloarei Nucu (Citation2021), Mahmood et al. (Citation2019) and Baños-Caballero et al. (Citation2012), only showed that there exists a quadratic nonlinear relationship between working capital and profitability. However, this approach has not clarified the effect of working capital in terms of the capital structure of enterprises. Specifically, at a certain leverage threshold, businesses will decide to optimize their appropriate working capital management to improve profits. Therefore, it is necessary to have a very clear and comprehensive study on the non-linear relationship between WCM and FP (Knauer & Wöhrmann, Citation2013).

Working capital can be used to estimate the future short-term solvency of firms (Petersen, Citation2009). A positive value of working capital means that current assets on the balance sheet are greater than amortized liabilities on the balance sheet, which can be partially financed over the long term. Conversely, negative working capital means that long-term assets are partially financed in the short term, which at first glance contradicts current funding rules. However, firms with competitive potential in a large market and fast turnover of goods can certainly have negative working capital. In this case, the company sells its goods faster than it has to pay the supplier’s bill (Ertl, Citation2004).

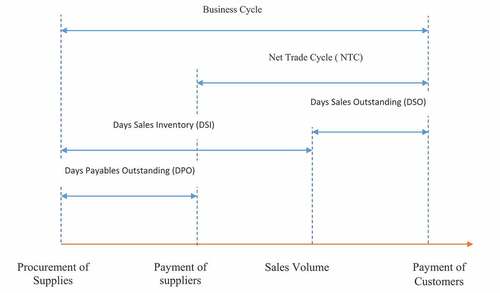

Working capital is an absolute number that is less relevant in the assessment between industry and business. For this reason, the concept of “cycle time” has been established in science and practice, measuring the length of time a company has to finance working capital. First, supplies are procured and stored (Meyer & Lüdtke, Citation2006). And this increases current assets and on the other hand leads to accounts payable. Depending on the agreed creditor objective, the goods are paid off after a period of time, for cash outflow. As a rule, the sale and finally the receipt of money from the customer through the sale of services takes place only later. As Figure shows, the inventory to be procured will be financed from the time the customer pays to the time the supplier pays. This period is also known as the Net Trading Cycle (NTC).

Figure 1. Net Trade Cycle (Source: Richards & J, Citation1980).

Furthermore, according to Arnt Wöhrmann et al. (Citation2012), working capital management, as measured by the key performance index NTC, working capital management intensity is higher when the net trade cycle is shorter. The results of the study clearly show that a shorter NTC and lower working capital investment go hand in hand with better corporate performance. Obviously, working capital management is an important factor in controlling profitability. There is a negative relationship between NTC and ROE. In this view, however, the question that needs to be answered is whether one, some, or all of the three components (DSO, DPO, and DIO) of working capital are responsible for the positive impact of capital management. And whether there is a difference between these three components in terms of the profitability of the business. This will be considered empirically in our study.

Through the threshold model of Hansen (Citation1999), this study was carried out to test whether there exists a threshold of financial leverage in the decision on working capital, thereby assessing the change in the impact of working capital on corporate profits for this defined threshold. Together with panel data of 405 companies listed on the Ho Chi Minh City Stock Exchange and the Hanoi Stock Exchange in the 2010–2020 period, compiled by Thomson Reuters (2021), the study estimates the models using separate WCM representative variables and, finally, the model with WCM including three component variables: DSO, DPO, and DIO. The results show that, firstly, there exists a non-linear relationship between working capital management and firm profitability. Second, at a certain ratio of debt coefficient, the variables representing working capital management all have a negative impact on firm profitability. In this relationship, there is a different impact of the representative variables of Working Capital Management before and after the threshold, and specifically, the impact values of these representative variables are higher after the threshold. Finally, for control variables such as cash ratio, sales growth, and log of total assets, there is a positive impact on FP, but nevertheless, the financial asset variable has a negative impact on FP.

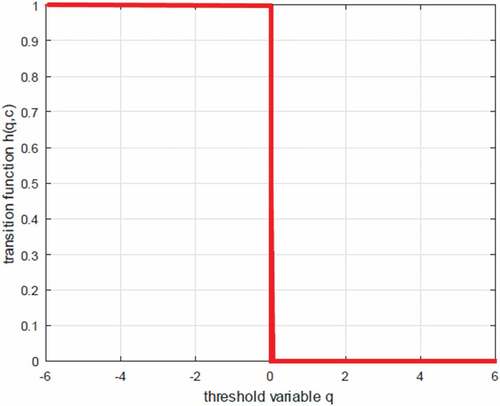

As such, our research makes new theoretical and practical contributions to the literature on the relationship between working capital management and corporate profitability. First, the study expands and complements the literature in this area by highlighting new evidence on the non-linear relationship between working capital management and firm performance in Vietnam. The results show that the relationship between working capital and profitability of the enterprise will have a breaking point at the threshold value of the debt ratio coefficient of the enterprise in the form of a binary transition function. The findings show that the debt ratio has a negative impact on the profitability of the business, and when this debt ratio reaches the threshold ratio (about 78.45%), the negative impact of the debt ratio on the profitability of the firms is higher than before the threshold. Second, at a certain debt structure (threshold), working capital that has a negative impact on profitability will continue to increase. Finally, the study concludes with the main implication that working capital will improve profitability in the framework of an emerging economy like Vietnam.

The rest of this article is structured as follows. Section 2 will provide a review of relevant literature, whereas Section 3 describes the methodology and data used for the empirical evidence. Next, Section 4 presents the results of the study, and Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Literature review

Working capital management is highly relevant to a firm’s success because of its impact on profitability and risk, and hence on its value (Smith, Citation1980). Fundamentally, there are three basic theories that highlight the relationship between debt and profitability, namely: the signalling theory, the agency cost theory, and the tax theory (Kebewar, Citation2012). According to the signaling theory, debt, in the presence of asymmetrical information, should be positively correlated with the profitability of the firm. According to the agency costs theory, there are two contradictory effects of debt on the profitability of companies: firstly, it is positive in the case of agency costs of equity shareholders and managers; secondly, it is negative, resulting from the agency costs of debt between shareholders and lenders. Finally, the tax theory shows its complexity in the sense that the ratio of debt to profitability depends on the tax treatment of interest and income.

The literature reviews proposed different views to explain the relationship between working capital and firm profit. On the one hand, most of the previous studies find a positive relationship between WCM and FP, based on firms from developed economies like the US (Lyngstadaas, Citation2020), the UK (Goncalves et al., Citation2018), Finland (Almeida et al., Citation2014), or from developing economies like Uganda (Kabuye et al., Citation2019), Egypt (Moussa, Citation2018), Vietnam (Nguyen & Van Nguyen, Citation2018), Ghana (Amponsah-Kwatiah & Asiamah, Citation2020). Kabuye et al. (Citation2019) analysed the impact of internal control systems and working capital management on the financial performance of 110 supermarkets in Uganda and found that working capital management is a significant predictor of financial performance. Moussa (Citation2018) examines the impact of working capital management on the performance of 68 industrial firms from Egypt for the period of 2000–2010 and documents a positive relationship between working capital management (measured by the cash conversion cycle) and firm profitability. The author points out that stock markets in less developed economies do not realize the optimum efficiency of their WCM.

Nguyen and Van Nguyen (Citation2018) analyse the relationship between working capital management and corporate profitability and document a positive nexus between working capital management and the performance of Vietnamese listed firms over the period of 2008–2014. As reported by Amponsah-Kwatiah and Asiamah (Citation2020), listed manufacturing firms in Ghana exhibit a positive relationship between different components of working capital and profitability. Moreover, Goncalves et al. (Citation2018) confirm that WCM efficiency increases profitability in the example of UK unlisted companies between 2006 and 2014. In the US, effective working capital management is found to be associated with the higher financial performance of listed manufacturing firms, as reported by Lyngstadaas (Citation2020). J. Enqvist et al. (Citation2014) examine the impact of working capital management on firm profitability in different business cycles, using the example of Finland between 1990 and 2008, and highlight that firms can enhance their profitability by improving working capital efficiency. This first point of view is explained by the fact that working capital offers firms the opportunity to grow by increasing sales and revenues. There are firms with large exposures to risk connected to small levels of inventory (Michalski, Citation2016). Therefore, in the case of those firms, holding a low level of inventory leads to negative modifications in sales levels and weaker profits (Michalski, Citation2016).

Regarding the regulatory role of financial leverage, according to Asad Khan et al. (Citation2018), through reducing the debt ratio (DR), the profitability of firms can also be increased. By increasing the Accounts Receivables Collection (RCP), Payable Payable Period (PPP), and reducing the Inventory Turnover (ITP) and Cash Cycle (CC), the management of the non-financial sector can increase profitability. The existence of an interaction between the debt ratio and working capital management preferences undermines the strength of the direct relationship between working capital management and profitability (Asad Khan et al., Citation2018). Therefore, working capital management policies are heavily influenced by the introduction of financial leverage in the capital structure (Einarsson & Marquis, Citation2001; Fazzari & Petersen, Citation1993; Hill et al., Citation2010). As such, managers should review the regulatory role of leverage in working capital management (J. Enqvist et al., Citation2014).

3. Empirical evidence on the linear relationship between WCM and FP

Conflicting theories to explain the relationship between working capital and business performance have been proposed in the academic literature. Nguyen and Van Nguyen (Citation2018) investigate the link between working capital management and corporate profitability, finding a favourable correlation between working capital management and the performance of Vietnamese publicly traded companies from 2008 to 2014. According to Amponsah-Kwatiah and Asiamah (Citation2020), listed manufacturing businesses in Ghana show a favourable link between several components of working capital and profitability. Furthermore, utilizing the case of UK unlisted firms between 2006 and 2014, Goncalves et al. (Citation2018) indicate that WCM efficiency boosts profitability.

According to Lyngstadaas (Citation2020), efficient working capital management is linked to superior financial performance of listed industrial businesses in the United States. J. Enqvist et al. (Citation2014) look at the influence of working capital management on company profitability during several business cycles, using Finland as an example, between 1990 and 2008, and find that enhancing working capital efficiency can help businesses increase their profitability. This first viewpoint is supported by the fact that working capital allows businesses to expand through boosting sales and revenues. As a result, in the case of those businesses, having a low inventory level causes unfavorable changes in sales levels and lower earnings (Michalski, Citation2016).

WCM and firm profitability were investigated by Jose, Lancaster, and Stevens (Citation1996). They used samples from 2,718 businesses between 1974 and 1993. According to the findings, the cash conversion cycle has a negative relationship with business profitability as measured by return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE) (ROE). It also implies that shortening the cash conversion cycle (CCC) may assist a company in becoming more profitable. As a result, the manager may be able to increase the firm’s profitability by properly managing working capital. H.-H. Shin and Soenen (Citation1998) look into the relationship between WCM and company profitability. The findings show a negative relationship between CCC and FP, implying that by lowering CCC to an appropriate minimum level, the firm’s management may produce valuable assets for its shareholders.

Studies in developed countries, such as Taiwan (Wang, Citation2002), Belgium (Deloof, Citation2003), Japan (Nobanee, Abdullatif, and AlHajja, Citation2011), Spain (Juan Garcia-Teruel & Martinez-Solano, 2013), Singapore (Mansoori & Muhammad, Citation2012), and the United Kingdom (Tauringana & Adjapong Afrifa, Citation2013), show a negative relationship between CCC and other parts of CCC on the firm’s profit. As a result, by effectively regulating working capital management, the firm’s profit may increase. Several studies in poor countries, such as Greece (Lazaridis & Trifonidis, Citation2006), Kenya (Mathuva, Citation2010), Brazil (Ching, Novazzi & Gerab, 2011), and Pakistan (Afeef, 2011), have found that WCM has a detrimental impact on business profitability. For this reason, company executives should optimize CCC, average receivables (AR), and inventory (INV) as required. Chang (Citation2018) confirms that a conservative working capital management approach improves company performance, based on a sample of 31,612 enterprises from 46 countries from 1994 to 2011.

Similarly, another line of study claims that WCM has a negative impact on profitability, utilizing samples from established economies (Dalci et al., Citation2019; Fernandez-Lopez et al., Citation2020; Ren et al., Citation2019); the European Union (Akgun & Memis Karatas, Citation2020), or emerging countries (Akgun & Memis Karatas, Citation2020; Ben, Citation2019; Habib & Huang, Citation2016; Pham et al., Citation2020; Ukaegbu, Citation2014; Wang et al., Citation2020; Yusoff et al., Citation2018). For a sample of Spanish manufacturing businesses from 2010 to 2016, Fernandez-Lopez et al. (Citation2020) found a negative relationship between several components of working capital and firm performance. Dalci et al. (Citation2019) used various methodologies to examine the relationship between cash conversion cycle and profitability for 285 German non-financial firms from 2006 to 2013. They discovered that shortening the cash conversion cycle has a positive effect on the profitability of small and medium sized firms, based on pooled ordinary least squares (OLS), fixed effects, random effects, and generalized moment model (GMM). For a sample of European Union-28 listed businesses during the 2008 financial crisis, Akgun and Karatas (Citation2020) detected a negative connection between working capital and company performance. Ren et al. (Citation2019) also discovered an inverse relationship between the cash conversion cycle and the profitability of Chinese non-state-owned companies. According to Ben (Citation2019), working capital management has a negative influence on company value, profitability, and risk, for a sample of 497 Vietnamese enterprises from 2007 to 2016. For Vietnamese steel firms, Pham et al. (Citation2020) report the same negative connection.

Yusoff et al. (Citation2018) investigate the link between working capital management and company performance in Malaysia. The authors show that inventory conversion time, average collection time, and cash conversion cycle are all negatively correlated with profitability. Shrivastava et al. (Citation2017) used both traditional panel analysis and Bayesian approaches to show that a prolonged cash conversion period has a negative impact on profitability in India. Using panel least squares estimate, panel fixed effect, and panel generalized technique of movement, Habib and Huang (Citation2016) conclude that positive working capital hurts profitability while negative working capital helps profitability in the case of Pakistan. Wang et al. (Citation2020) also found a negative relationship between WCM and the performance of non-financial listed businesses in Pakistan. Furthermore, from 2005 to 2009, Ukaegbu (Citation2014) discovered that cash conversion cycles had a detrimental influence on company profitability, as measured by net operating profit, in a panel of manufacturing firms in Egypt, Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa. Businesses should strive for an ideal amount of working capital investment, according to the authors, in order to improve their overall performance.

4. Non-linear relationship between WCM and FP

Recently, a new point of view has emerged, focusing on the functional structure of working capital management and profitability. A few studies have found a concave relationship between the two measures, with the majority dissecting firms from developed economies (Mahmood et al., Citation2019; Tsuruta, Citation2018; Aktas et al., Citation2015; Baos-Caballero et al., 2014), followed by a sample of firms from emerging European countries (Bot et al., Citation2017) or firms from a specific industry (Mun & Jang, Citation2015). For a sample of Chinese firms from 2000 to 2017, Mahmood et al. (Citation2019) describe an inverted U-shaped working capital and profitability connection, using GMM as a fundamental technique. Using the same GMM approach, Laghari and Chengang (Citation2019), using the same GMM approach, provide empirical evidence of an inverted U-shaped relationship between working capital and profitability of Chinese listed businesses. For a sample of Chinese firms from 2000 to 2017, Mahmood et al. (Citation2019) highlight an inverted U-shaped working capital management and profitability relationship, also by using the GMM technique. With the same GMM approach, Laghari and Chengang (Citation2019) provide empirical evidence of an inverted U-shaped relationship between working capital and profitability of Chinese listed firms. For a sample of UK companies, Baos-Caballero et al. (2014) discover a non-linear relationship between working capital and company value, implying that there is an optimal amount of working capital that maximizes firm revenues.

The study of the relationship between WCM and FP for 1008 small and medium-sized businesses in Spain between 2002 and 2007 by Banos-Caballero, Garca-Teruel, and Martnez-Solano (Citation2012) followed the same pattern. In order to evaluate the profit-risk exchange in various working capital methods, the author investigated the non-linear link between WCM and FB. The findings revealed that the company’s optimal working capital level is one that balances benefits and expenses while also optimizing the company’s value. The results of the investigation were analyzed, and it was determined that exceeding the optimum amount of working capital resulted in a loss of profit.

Banos-Caballero et al (Citation2014) use the same technique to assess the company’s performance rather than the conventional accounting assessment. Research results show that there is an optimal level of exploitation equity that balances costs and benefits in WCM’s optimization of FB, demonstrating the non-linear relationship between WCM and FB. In a similar case, Banos-Caballero, Garcia-Teruel and Martinez-Solano (2012) expanded their investigations into the relationship between WCM and FP to 1008 small and medium-sized enterprises in Spain between 2002 and 2007. This paper examined the non-linear relationship between WCM and FB to assess the trade-off between profit and risk in various working capital methods. The findings revealed that the optimal amount of working capital for the business to balance benefit and expense exists, therefore optimizing the firm’s worth. The research concluded that when working capital exceeds the optimal level, profit would be reduced.

5. Effect of leverage on working capital management

Nadiri’s research gave credence to the idea of optimal working capital (1969). Since then, a number of researchers have presented their findings and proposed various financial indicators as well as the amount of working capital required for various types of businesses (Gupta, Citation1969; Gupta & Huefner, Citation1972). However, the risk-reward trade-off will be critical in determining whether to pursue an aggressive or conservative working capital management strategy at any given time (Gardner, Mills, & Pope, Citation1986; Weinraub & Visscher, Citation1998). According to another statement, a large investment in working capital reduces supply costs, provides a hedge against price fluctuations, and minimizes the loss of sales from potential stockists (Blinder & Maccini, Citation1991; Corsten & Gruen, Citation2004; Fazzari & Petersen, Citation1993). On the other hand, investments in the short-term assets of the company can lead to lower agency values and costs (Khan, Bibi et al., Citation2016). Increasing investment in operating capital will result in additional financing, interest expense, bankruptcy, and opportunity costs (Kieschnick et al., Citation2013). The associated benefits and costs of higher working capital present a classic case of the non-linear relationship between firm performance and the level of working capital. Over-investment in working capital will almost certainly result in the depreciation of the firm’s value, and vice versa.

Early studies like Fazzari and Petersen (Citation1993) have highlighted the importance of financial leverage and supported the fact that the financial constraints of the firms will indicate their ultimate investment in working capital. Similarly, Einarsson and Marquis (Citation2001) argue that one of the major factors associated with the relationship between a firm’s profitability and working capital management policy is the financial leverage of the firm. Specifically, Hill et al. (Citation2010) recommend that investment in working capital is highly sensitive to access to capital markets. In particular, firms’ high dependence on external finances makes them more prone to shifting economic conditions and their working capital management policy (J. Enqvist et al., Citation2014). The efficient management of operating capital by firms can significantly reduce their dependence on external finance, which will result in a reduction of financing costs (De Almeida & Eid, Citation2014), especially in high-cost developing countries like Pakistan (Pakistan Interest Rate, Citation2016; Alam, 2015; Khan, Citation2015; Zaidi, Citation2015).

Although the investment in operating capital will result, in higher sales and early payment by offering customer discounts and hence increase the firm value, the optimal level of working capital will increase interest expense and credit risk, which will negatively affect the firm’s value (Baños-Caballero et al., Citation2014). Due to capital market imperfection, the banking sector is the primary source of finance for the industry, and those advances are characterized by the unique set of requirements and covenants (Khan, Citation2015). Thus, to understand how the financial leverage of companies affects the relationship between working capital management policy and profitabilits, hypotheses have been developed using additional financial leverage as a moderating variable.

From the above reviews, it shows that there are many studies on the relationship between WCM and FP, with various types of research data samples, research models, and research methods. These studies have not evaluated the non-linear relationship between WCM and FP, according to the approach on clarifying the influence of working capital in the context of capital structure of enterprises. Specifically, with a certain leverage threshold, the enterprise will decide to optimize the appropriate working capital management to improve profits. Therefore, this study is carried out to test whether there exists a threshold of financial leverage in the decision on working capital, thereby assessing the change in the impact of working capital on corporate profits with the threshold established to determine this, based on the threshold model of Hansen (Citation1999) with the form of a binary transition function.

6. Data and methodology

On the basis of previous studies (Deloof, Citation2003; Erik Rehn, 2012; Knauer & Wöhrmann, Citation2013; Asad Khan et al., Citation2018; Nguyen and Dang, Citation2020; Anton and Afloarei Nucu, Citation2021), the study proposes the following analytical framework (Figure ):

6.1. Research data

Data for the research is aggregated, including 405 companies listed on the Ho Chi Minh City Stock Exchange and the Hanoi Stock Exchange in the 2010–2020 period, compiled by Thomson Reuters (2021) with 4,455 observations.

6.2. Methodology

Threshold models are widely used in economic and financial analysis. The threshold model allows for describing non-linear characteristics in the relationship between variables. According to Hansen (Citation1999), a panel threshold regression (PTR) model is defined as follows:

in which:

yit is the dependent variable

are fixed effects.

qit is the threshold determining variable

xit is vector k explanatory variables

is an indicator function.

γ is a threshold parameter

EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) can be rewritten as:

in which is a binary transition function ().

EquationEquation (2)(2)

(2) can be rewritten explicitly as follows:

7. Threshold effect test

Once a potential threshold value has been determined, it is important to check whether the threshold effect is statistically significant. Hansen (Citation1999) proved that is a statistically robust estimate of γ, and argues that the best way to test

is to determine the confidence interval, using the method (no-rejection region) the reasonable ratio test (Likelihood Ratio, LR).

Specifically, the threshold effect test (or the test for the existence of a threshold value) is equivalent to testing whether the coefficients β1 and β2 are the same in the groups. The hypotheses can be put forward as follows:

Hypothesis H0 or linear hypothesis : there is no threshold effect in the model; and hypothesis H1:

: there exists a threshold effect in the model.

Under the heteroscedasticity-robust assumption, the likelihood ratio statistic is calculated as follows:

in which, is variance estimated;

and

are the residual sum of squares, respectively, according to hypothesis H0:

and conjecture

.

7.1. Research models

From the review work of Knauer and Wöhrmann (Citation2013), it has been shown that there are many different proxies used to evaluate the impact of WCM on corporate profits, but most of the results show a negative effect of WCM indicators on profit. Knauer and Wöhrmann (Citation2013) also show three existing problems with the models: (i) separate use of WCM proxies; (ii) failure to take into account the nonlinearity of WCM and profitability; and (iii) little attention paid to causal inference in the relationship considered (Table ).

Table 1. Synthesized description of variables in the model

Table 2. Empirical studies on working capital management and firm profitability

The study has resolved the issue of non-linearity in research by means of threshold models based on the development of Knauer and Wöhrmann’s (2003) research model on the nonlinear link between WCM and profit. The non-linearity of WCM on the return on the threshold value of leveraged debt has the form:

in which:

Parameters µi and eit are the error components of the model.

ROE: Return on Equity is a variable that represents corporate profits.

DEBTR is the Debt ratio that is both a threshold determining variable (gamma, γ) and a variable with coefficients varying with the threshold.

X includes control variables with coefficients that do not change with threshold value, including CASHR (Cash ratio), SALESGR (Sales growth), FIXSS (Finance assets ratio), and SIZE (Firm size).

NTC is a composite index representing WCM. This is a variable whose coefficient varies with the threshold value.

In addition, the study develops four more specific assessment models to assess the importance of each component of WCM:

(In Model 5, the WCM variable consists of three component variables: DSO, DPO, and DIO).

And, one by one, the models from (1) to (5) are estimated and tested using the following procedure ():

Figure 4. Hansen’s (Citation1999) threshold model estimation process. Source: Description of the author’s research process.

The study uses Hansen’s (Citation1999) threshold estimation (fixed effect panel threshold model) to determine thresholds and estimate model parameters. Threshold models are estimated using the xthreg command in Stata 16 with the following options:

qx(DEBTR) declares the variable DEBTR as the variable that determines the threshold,

rx() declares variables whose coefficients change in the threshold regime (threshold regime), including DEBTR, DSO, DPO, DIO, and NTC.

bs(300) declares the number of replicates as 300 to calculate statistical values.

8. Research results

In the threshold estimate of Hansen (Citation1999), it is required that the panel be strongly balanced for the xthreg command. Therefore, for firms with insufficient year-to-year observation in the threshold estimate of Hansen (Citation1999), it is required that the panel be strongly balanced for the xthreg command. Therefore, firms with insufficient year-to-year observations or missing data should be removed from the sample. To some extent, this limits the expansion of the data sample to only 405 companies with full index data for the 10 years from 2010 to 2020, as shown in Table .

Table 3. Summary of statistics

The able 3 gives the descriptive statistics of the collected variables. The total number of observations sums up to n = 4,455. The average net return on equity (the average ROE of the companies during the survey period was 12.42%, along with an average leverage of 51.82% of total debt to total assets. The average revenue growth rate is relatively high, with an increase of nearly 50% over the entire period. Additionally, the average values of the variables “Days sales outstanding,” “Days purchase outstanding,” “Days inventory outstanding,” and “Net Trade Cycle” are 129.83, 63.83, 195.42, and 270.28 days, respectively.

The correlation coefficient between the variables in the research models is shown in Table . In particular, the correlation coefficient between ROE and DSO and DPO is higher than that of DIO, so the impact is overwhelming between the variables DSO, DPO, and DIO, which may happen. Table also shows that NTC is highly correlated with DIO. Nonetheless, these two variables appear in two separate models in Equationequations (3)(Model 3)

(Model 3) and (Equation4

(Model 4)

(Model 4) ), so they have no bearing on the multicollinearity problem with the models in question.

Table 4. Correlation matrix

In the study, the variables need to ensure stationary before the model is estimated. The Breitung test is used to test the stationarity of balanced panel data series. The Breitung test allows considering the cross-sectional correlation of the error terms, as well as the heterogeneous variance in the test equation (Breitung and Das, Citation2005). The results show that, except for the variable SIZE, all series are stationary at the original order (at 1% statistical significance level; Table ).

Table 5. Testing for stationarity of series

8.1. The effect of NTC on FP

There exists a non-linear effect of NTC on ROE at the threshold DEBT value of 78.45% (Table ). The NTC has been created as a supplementary technique, as a proxy for the management of working capital (e.g., Meyer and Lüdtke, Citation2006; H.-H. Shin & Soenen, Citation1998). Unlike the CCC, the sales of all three components are utilized for computing the NTC as the denominator. Although this technique has lower precision, its clear advantage is that it applies to companies that utilize full cost accounting as well. When complete cost accounting of the products sold is utilized, it is impossible to calculate DSI or DPO in the way stated in Table . The NTC avoids this difficulty instead.

Table 6. Threshold effect of NTC on ROE

From the results of Table , corresponding to the debt ratio of 78.45%, the negative impact of the DEBTR and NTC on ROE tends to increase between before and after the threshold (Before: −0.0539, After: −0.0700; Before: −0.0018, After: −0.0051) with high statistical significance. Thus, with a shorter NTC, lower working capital goes hand in hand with better corporate performance. As such, working capital management is an important factor in controlling profitability. In addition, the net trade cycle is also a very important metric as it can add value to shareholders if managed properly (Arnt Wöhrmann et al., Citation2012). By shortening the net trade cycle, the present value of net cash flows will be higher, creating value for homeowners (H. Shin & Soenen, Citation2000). The shortening of the net trade cycle also contributes to working capital management as it reduces the need for external financing and lowers borrowing costs, improving the financial performance of the company. The highlight of this result is that, depending on the debt ratio of each enterprise, there will be different negative effects from the NTC and the debt ratio in the period before and after the threshold. Since then, firms have adopted appropriate policies for NTC and debt ratios.

However, this aggregate view leaves the question unanswered as to whether one, several, or all three working capital components are responsible for the positive effect on profitability and whether there are differences between these three components during and after the crisis. This will be examined in more detail in the next step.

8.2. The Effect component variables of WCM on FP

The results of the threshold estimation of Models (2), (3), (4), and (5) are summarized in Table below. Accordingly, there are different effects of WCM variables in the period before and after the threshold value of DEBTR (except for model 4, where there is no threshold value). The results of the threshold effect test through the Bootstrap technique show that, except for the DIO model, which has no threshold effect, the remaining three models all have the threshold effect in the relationship under consideration (i.e. at a 5% statistical significance level). In addition, in these models, the results of determining the maximum number of thresholds indicate that only one threshold effect exists.

Table 7. Threshold effects of WCM’s components on ROE

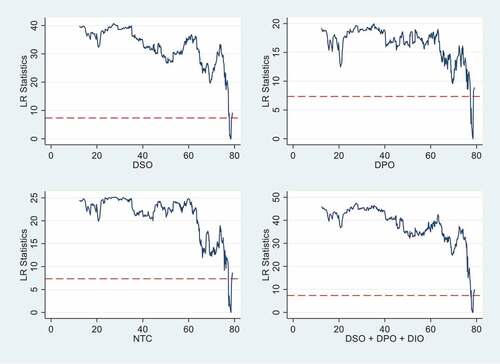

For Models (2), (3), and (5), there is a non-linear relationship between debt coefficient and ROE, with threshold values (gamma, γ) of 78.45%, 78.45%, and 78.21%, respectively. At these threshold values, DEBTR has a negative impact on ROE. These negative impact values change in an increasing direction in the periods before and after the threshold (Before: −0.0619, After:-0.0651; Before:-0.0450, After:-0.0617; Before:-0.0432, After:-1.0651). The results of this study are consistent with previous studies such as Anton and Nucu (2020), Bana Abuzayed (Citation2012), and DEBTR, which found a negative impact on the profitability of the business. Despite the difference between this study and previous studies, DEBTR’s negative impact on ROE tends to increase over the period before and after the threshold. A negative value before the threshold is greater than a negative value after the threshold. This is also explained in a similar way for the DSO and DPO variables in Model 2 and Model 3. And this is a novel finding in the study: debt ratio is both a threshold-determining variable (gamma, γ) and a variable with a coefficient that varies with the threshold. And the variation of variables in the models is shown in Figure .

Figure 5. Confidence interval construction for the first threshold value, Source: Stata program.

In models (2), (3), and (5), corresponding threshold values (Gamma, γ) of 78.45%, 78.45%, and 78.21% are also shown in Table . The results show that all the component variables of WCM (DSO, DPO, and DIO) have a negative impact and have a higher post-threshold impact value on ROE. It means that the tighter the profitability of the working capital management company, the higher the profitability of the working capital management company. The results are generally consistent with previous studies such as Ali Ihsan Akgun et al. (Citation2020) and Meyer and Lüdtke (Citation2006). Net trading cycle is also a very important metric as it can add value to shareholders if managed properly. By shortening the net trade cycle, the present value of net cash flows will be higher, thus creating value for owners (H. Shin & Soenen, Citation2000). The shortening of the net trade cycle also contributes to working capital management as it reduces the need for external financing and lowers borrowing costs, improving the financial performance of the company. However, the results of this study are in contrast to those of Aton (Citation2021) at an early stage. In fact, the research results of Anton (2020) show that NTC has a positive impact on corporate profitability and, related to this positive effect, to some extent, it will have a negative impact. The relationship is an inverted U-shape.

With the general model (Model 5), the variables debt ratio, DSO, and DPO all have a negative impact on firm profitability, and the impact of DSO is significantly more potent than that of the DPO. The DSO has a significant negative correlation with profitability. This means that by reducing the amount of day credit granted to customers, a company can increase its profitability. And we can see the effect of DIO on profitability. It is very interesting to note that current inventory levels appear to have a significant positive effect on business profitability. This might be attributed to the fact that the sample consists of several different industries, and several of those industries do not invest heavily in inventory, which indicates that stockpiling inventory will typically increase a company’s profitability. This finding contradicts several previous studies, including Deloof (Citation2003), Garcia-Teruel and Martinez-Solano (Citation2007), and Julius Enqvist et al. (Citation2014). But it is coherent with those of others, like Lazaridis and Tryfonidis (Citation2006) and Bana Abuzayed (Citation2012).

Finally, the estimated results for control variables in all models show that cash ratio, sales growth, and log of total assets have a positive influence on the profitability of the business. Sales growth can be an indicator of a company’s commercial viability, and the cash ratio is an essential factor that enables companies to achieve better profitability, as the ratio’s Positive sign effects are strongly influenced (Bot et al., Citation2017; Garcia-Teruel & Martinez-Solano, Citation2007). Firm size measures a company’s transparency, availability, and credibility (Tsuruta, Citation2018). Due to the imbalance of information between lenders and borrowers, financial constraints can lead to financial constraints for small businesses. As the banking sector makes up the bulk of the financial system in Vietnam, it can be difficult for businesses to have enough cash to invest in working capital. Therefore, firm size is predicted to be a positive predictor of profitability. According to Garcia-Teruel and Martinez-Solano (Citation2007) for SMEs in Anton and Elena Afloarei Nucu (Citation2021) for Polish listed enterprises, the positive SIZE sign indicates that large size seems to promote profitable production. In addition, Simon et al. (2017b) identify a negative and significant relationship between a firm’s size and ROE, while Sharma and Kumar (Citation2011) suggest that firm size is positively related to profitability. Pervan et al. (2012) show that firm size has a positive and significant effect on firm profitability. Regarding control variables, Lyngstadaas and Berg (Citation2016) found that SIZE and CR are significantly and positively related to business performance. In addition to the statements about the positive impact of firm size on ROE, research by Ali Ihsan Akgun (2020) shows that firm size (SIZE) has a significant and negative impact on business performance, such as ROE at 10% for performers. In particular, variable financial assets have an adverse effect on a company’s profitability. According to the Capital Structure Order Theory (Aktas et al., Citation2015; J. Enqvist et al., Citation2014), firm profitability is negatively correlated with debt. In terms of Pecking Order Theory, firms prioritize different sources of funding, from internal funding to equity, based on the cost of the resources.

Thus, from the theoretical review, it is shown that previous empirical studies only stopped the linear relationship between WCM on FP. Our research results have strong evidence for the existence of a non-linear relationship between WCM and FP. Empirical evidence also shows that for a given firm’s debt ratio, the aggregate or individual variables representing WCM will have different effects on FP at this defined threshold. The same holds true for the effect of the debt ratio on FP. And this is also a new point in our research results.

9. Conclusion

In this research, we provide a new novel approach for the working capital- profitability relationship with a data sample of 4455 observations, synthesized from 405 companies listed on the Ho Chi Minh City Stock Exchange and the Hanoi Stock Exchange during the period 2010–2020, compiled by Thomson Reuters (2021).

The study has systematized the theoretical overview and proposed research models for the non-linear relationship between WCM and FP comprehensively.Through the threshold model of Hansen (Citation1999), together with a rigorous research process, the research results with strong evidence for this relationship are as follows: There exists a non-linear relationship between WCM and FP; and at the same time, there exists a nonlinear effect of DEBTR on ROE, with a coefficient. The negative effect of DEBTR on ROE before and after the threshold is different from a small value. All of the component variables of WCM have a negative effect on ROE. That is, the tighter the working capital management firm profit, the higher the working capital management firm profit. As far as the level of impact is concerned, all the variables have a much larger impact after the threshold than before.

In terms of magnitude, the impact of the composite index (NTC) on profitability is smaller than that of the individual WCMs. In the general model, the impact of the DSO is significantly stronger than that of the DPO. The study’s highlight is that Debtr is both a threshold-determining variable (gamma, γ) and a variable with coefficients that vary with the threshold. There are different negative effects from WCM and DEBTR in the pre-threshold period and post-threshold period. Depending on the debt ratio of the firm, the firm has policies that are in accordance with the WCM and the debt ratio.

Regarding the contribution of the research, this study offers both theoretical and practical implications. For researchers, our results suggest that the threshold model with a binary transition function should be tested for any sample of firms. Regarding the practical implications for Vietnamese companies, specifically, with a certain threshold of leverage (debt ratio), enterprises will decide to optimize their appropriate working capital management to improve profits for their own careers. For this to take effect, it is necessary to: (i) reduce the debt ratio of the enterprise through capital sources other than debt instruments; and (ii) have a tighter (lower) working capital management policy such as on NTC, DSO, and DPO. Importantly, the more efficient the working capital management, the more profitable the firm’s operation will be, especially for firms whose debt ratio exceeds the threshold.

Besides the practical contributions of this research, its limitations are certainly unavoidable. First, the empirical findings are limited to listed firms from an emerging country (Vietnam). Furthermore, from an endogenous point of view, most corporate-level financial variables are defined in a network of relationships. Future research that expands the sample of countries and controls for macroeconomic factors and endogenous issues could provide valuable contributions to the field as well as open new research directions on the relationship between WCM and firm profits. For example, causal analysis may be required to consider this relationship, specifically whether WCM affects ROE or vice versa, or whether it acts in both directions, as suggested by Knauer and Wöhrmann (Citation2013).

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nguyen Thanh Hung

Mr. Nguyen Thanh Hung is a lecturer at School of Public Finance, University of Economics Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 59C Nguyen Dinh Chieu, Ward 6, District 3, Ho Chi Minh City 70000, Vietnam, also a lecturer at Binh Duong University, Thu Dau Mot city, Binh Duong Province, Vietnam. He specializes in finance, accounting and taxing. Mr Hung published 20 internaltional articles and 10 Vietnam articles. Email: [email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9928-0329.

Thanh Su Dinh

Prof. Su Dinh Thanh is a lecturer at School of Public Finance, University of Economics, 59C Nguyen Dinh Chieu, Ward 6, District 3, Ho Chi Minh City 70000, Vietnam. He specializes in finance, accounting and taxing. Email: [email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2344-6315.

References

- Abuzayed, B. (2012). Working capital management and firm’s performance in emerging markets: The case of Jordan. International Journal of Managerial Finance, 8(2), 155–24.

- Afrifa, G. A., & Padachi, K. (2016). Working capital level influence on SME profitability. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 23(1), 44–63. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-01-2014-0014

- Akgun, A. I., & Memis Karatas, A. (2020). Investigating the relationship between working capital management and business performance: Evidence from the 2008 financial crisis of EU-28. International Journal of Managerial Finance.

- Aktas, N., Croci, E., & Petmezas, D. (2015). Is working capital management value-enhancing? Evidence from firm performance and investments. Journal of Corporate Finance, 30, 98–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2014.12.008

- Allini, A., Rakha, S., McMillan, D., & Caldarelli, A. (2018). Pecking order and market timing theory in emerging markets: The case of Egyptian firms. Research in International Business and Finance, 44, 297–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2017.07.098

- Almeida, D., Ribeiro, J., & Eid, W., Jr. (2014). Access to finance, working capital management and company value: Evidences from Brazilian companies listed on BM&FBOVESPA. Journal of Business Research, 67(5), 924–934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.07.012

- Altaf, N., & Ahmad Shah, F. (2018). How does working capital management affect the profitability of Indian companies? Journal of Advances in Management Research, 15(3), 347–366. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAMR-06-2017-0076

- Amponsah-Kwatiah, K., & Asiamah, M. (2020). Working capital management and profitability of listed manufacturing firms in Ghana. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management.

- Anton, S. G., & Afloarei Nucu, A. E. (2021). The Impact of Working Capital Management on Firm Profitability: Empirical Evidence from the Polish Listed Firms. J. Risk Financial Manag, 14, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14010009

- Anton, S. G., & Elena Afloarei Nucu, A. (2021). The Impact of Working Capital Management on Firm Profitability: Empirical Evidence from the Polish.

- Baños-Caballero, S., & García-Teruel, P.J.M.T.S. (2014). Working Capital Man- agement, Corporate Performance, and Financial Constraints. Journal of Business Research, 67, 332–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.01.016

- Baños-Caballero, S., García-Teruel, P. J., & Martínez-Solano, P. (2012). How Does Working Capital Management Affect the Profitability of Spanish SMEs? Small Business Economics, 39, 517–529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9317-8

- Baños-Caballero, S., García-Teruel, P., & Martínez-Solano, P. (2014). Working capital management, corporate performance, and financial constraints. Journal of Business Research, 67(3), 332–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.01.016

- Beck, N., & Katz, J. (1995). What to do (and not to do) with Time-Series Cross-Section Data. The American Political Science Review, 89(3), 634–647. https://doi.org/10.2307/2082979

- Ben, L. (2019). Working capital management and firm’s valuation, profitability and risk Evidence from a developing market. International Journal of Managerial Finance, 15(2), 191–204. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMF-01-2018-0012

- Blinder, A. S., & Maccini, L. J. (1991). The resurgence of inventory research: What have we learned? Journal of Economic Surveys, 5(4), 291–328. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6419.1991.tb00138.x

- Bot, O., Claudiu, & Gabriel Anton, S. (2017). Is profitability driven by working capital management? Evidence for high-growth firms from emerging Europe. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 18, 1135–1155.

- Breitung, J., & Das, S. (2005). Panel Unit Root Tests under Cross-Sectional Dependence. Statistica Neerlandica, 59, 414–433.

- Brennan, M. J., Maksimovics, V. O., & Zechner, J. (1988). Vendor financing. The Journal of Finance, 43(5), 1127–1141. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1988.tb03960.x

- Chang, C.-C. (2018). Cash conversion cycle and corporate performance: Global evidence. International Review of Economics and Finance, 56, 568–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2017.12.014

- Chen, C., & Kieschnick, R. (2018). Bank credit and corporate working capital management. Journal of Corporate Finance, 48, 579–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2017.12.013

- Coles, J. L., & Zhichuan, L. 2019. An Empirical Assessment of Empirical Corporate Finance. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1787143 (accessed on 13 December 2020)

- Coles, J. L., & Zhichuan, L. (2020). Managerial Attributes, Incentives, and Performance. The Review of Corporate Finance Studies, 9, 256–301.

- Corsten, D., & Gruen, T. W. (2004). Stock-outs cause walkouts. Harvard Business Review, 82(5), 26–28.

- Dalci, I., Hasan, O., Cem, T., & Bein, M. (2019). The Moderating Impact of Firm Size on the Relationship between Working Capital Management and Profitability. Prague Economic Papers, 28(3), 296–312. https://doi.org/10.18267/j.pep.681

- De Almeida, J. R., & Eid, W. (2014). Access to finance, working capital management and company value: Evidences from Brazilian companies listed on BM & FBOVESPA. Journal of Business Research, 67(5), 924–934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.07.012

- Deloof, M. (2003). Does working capital management affect profitability of Belgian firms? Journal of Business Finance <html_ent Glyph=“@amp;” Ascii=“&”/> Accounting, 30(3–4), 573–587. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5957.00008

- Einarsson, T., & Marquis, M. H. (2001). Bank intermediation over the business cycle. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 33(4), 876–899. https://doi.org/10.2307/2673927

- Enqvist, J., Graham, M., & Nikkinen, J. (2014). The impact of working capital management on firm profitability in different business cycles: Evidence from Finland. Research in International Business and Finance, 32, 36–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2014.03.005

- Enqvist, J., Graham, M., & Nikkinen, J. (2014). The impact of working capital management on firm profitability in different business cycles: Evidence from Finland. Research in International Business and Finance, 32, 36–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2014.03.005

- Ertl, M. (2004). Aktives Cashflow-Management: Liquiditätssicherung durch wertorientierte Unternehmensführung und effiziente Innenfinanzierung. Vahlen, 2004

- Fazzari, S. M., & Petersen, B. (1993). Working capital and fixed investment: New evidence on financing constraints. The Rand Journal of Economics, 24(3), 328–342. https://doi.org/10.2307/2555961

- Fernandez-Lopez, S., Rodeiro-Pazos, D., & Rey-Ares, L. (2020). Effects of working capital management on firms’ profitability: Evidence from cheese-producing companies. Agribusiness, 36(4), 770–791. https://doi.org/10.1002/agr.21666

- Frank, L. (2016). Endogeneity in CEO power: A survey and experiment. Investment Analysts Journal, 45(3), 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/10293523.2016.1151985

- Garcia-Teruel, P. J., & Martinez-Solano, P. (2007). Effects of working capital management on SME profitability. International Journal of Managerial Finance, 3(2), 164–177. https://doi.org/10.1108/17439130710738718

- Gardner, M. J., Mills, D. L., & Pope, R. A. (1986). Working capital policy and operating risk: An empirical analysis. The Financial Review, 21(3), 31–31.

- Golas, Z. (2020). Impact of working capital management on business profitability: Evidence from the Polish dairy industry. Agricultural Economics-Zemedelska Ekonomika, 66, 278–285.

- Goncalves, T. C., Gaio, C., & Robles, F. (2018). The impact of Working Capital Management on firm profitability in different economic cycles: Evidence from the United Kingdom. Economics and Business Letters, 7(2), 70–75. https://doi.org/10.17811/ebl.7.2.2018.70-75

- Gupta, M. C. (1969). The effect of size, growth, and industry on the financial structure of manufacturing companies. The Journal of Finance, 24(3), 517–529.

- Gupta, M. C., & Huefner, R. J. (1972). A cluster analysis study of financial ratios and industry characteristics. Journal of Accounting Research, 10(1), 77–95. https://doi.org/10.2307/2490219

- Habib, A., & Huang, X. (2016). Determining the optimal working capital to enhance firms’ profitability. Human Systems Management, 35(4), 279–289. https://doi.org/10.3233/HSM-160875

- Hansen, B. E. (1999). Threshold effects in non-dynamic panels: Estimation, testing, and inference. Journal of Econometrics, 93(2), 345–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(99)00025-1

- Hill, M. D., Kelly, G. W., & Hightfield, M. J. (2010). Net operating working capital behavior: A first look. Financial Management, 39(2), 783–805. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-053X.2010.01092.x

- Jong, D., Abe, M. V., & Verwijmeren, P. (2011). Firms’ debt–equity decisions when the static tradeoff theory and the pecking order theory disagree. Journal of Banking and Finance, 35(5), 1303–1314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2010.10.006

- Jose, M. L., Lancaster, C., & Stevens, J. L. (1996). Corporate returns and cash conversion cycles”. Journal of Economics and Finance, 20(1), 33–46.

- Kabuye, F., Kato, J., Akugizibwe, I., Bugambiro, N., & Ntim, C. G. (2019). Internal control systems, working capital management and financial performance of supermarkets. Cogent Business and Management, 6(1), 1573524. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2019.1573524

- Karaduman, H. A., Akbas, H. E., Caliskan, A. O., & Durer, S. (2010). Effects of working capital management on profitability: The case for selected companies in the Istanbul stock exchange (2005-2008). International Journal of Economics and Finance Studies, 2(2), 47–54.

- Kayani, U. N., De Silva, T.-A., & Gan, C. (2019). Working capital management and corporate governance: A new pathway for assessing firm performance. Applied Economics Letters, 26(11), 938–942. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2018.1524123

- Kebewar, M., The Effect of Debt on Corporate Profitability: Evidence from French Service Sector (December 18, 2012). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2191075

- Khan, S. (2015). Impact of sources of finance on the growth of SMEs: Evidence from Pakistan.Decision. 42(1), 3–10.

- Khan, A., Bibi, M., & Tanveer, S. (2016). The impact of corporate governance on cash holdings: A comparative study of the manufacturing and service industry. Financial Studies, 20(3), 40–79.

- Khan, A., Sohail, M., & Ali, M. (2016). Role of firm specific factors affecting capital structure decisions: Evidence from cement sector of Pakistan. Journal of Social and Organizational Analysis, 2(2), 112–127.

- Khan, A., Sohail, M., & Rehman, Z. (2018). Financial Leverage, Working Capital Management and Firm Profitability: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan Stock Exchange. Sarhad Journal of Management Sciences, 4(1), 97–110. https://dx.doi.org/10.31529/sjms.2018.4.1.8

- Kieschnick, R., Laplante, M., & Moussawi, R. (2013). Working capital management and shareholders’ wealth. Review of Finance, 17(5), 1827–1852. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfs043

- Knauer, T., & Wöhrmann, A. (2013). Working capital management and firm rofitability. Jmanag Control, 24(2013), 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00187-013-0173-3

- Laghari, F., & Chengang, Y. (2019). Investment in working capital and financial constraints: Empirical evidence on corporate performance. International Journal of Managerial Finance, 15(2), 164–190. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMF-10-2017-0236

- Lazaridis, I., & Tryfonidis, D. (2006). Relationship Between Working Capital Management and Profitability of Listed Companies in the Athens Stock Exchange. Journal of Financial Manage- Ment and Analysis, 19, 26–35.

- Listed Firms. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 14. 9. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14010009

- Lyngstadaas, H. (2020). Packages or systems? Working capital management and financial performance among listed U.S. manufacturing firms. Journal of Management Control, 31(4), 403–450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00187-020-00306-z

- Lyngstadaas, H., & Berg, T. (2016). Working Capital Management: Evidence from Norway. International Journal of Managerial Finance, 12, 295–313. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMF-01-2016-0012

- Mahmood, F., Han, D., Ali, N., Mubeen, R., & Shahzad, U. (2019). Moderating Effects of Firm Size and Leverage on the Working Capital Finance–Profitability Relationship: Evidence from China. Sustainability, 11(7), 2029. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072029

- Mansoori, D. E., & Muhammad, D. J. (2012). The effect of working capital management on firm’s profitability: Evidence from Singapore. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, 4(5), 472–486.

- Mathuva, D. (2010). The influence of working capital management components on corporate profitability: A survey on Kenyan listed firms”. Research Journal of Business Management, 4(1), 1–11.

- Meyer, S., & Lüdtke, J. P. (2006). Der Einfluss von Working Capital auf die Profitabilität und Kreditwürdigkeit von Unternehmen. Finanz Betrieb, 8, 609–614.

- Michalski, G. (2014). Value-Based Working Capital Management: Determining Liquid Asset Levels in Entrepreneurial Environments (pp. 1–179). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Michalski, G. (2016). Risk pressure and inventories levels. Influence of risk sensitivity on working capital levels. Economic Computation and Economic Cybernetics Studies and Research, 50, 189–196.

- Mielcarz, P., Osiichuk, D., & Wnuczak, P. (2018). Working capital management through the business cycle: Evidence from the corporate sector in Poland. Contemporary Economics, 12, 223–236.

- Moussa, A. A. (2018). The impact of working capital management on firms’ performance and value: Evidence from Egypt. Journal of Asset Management, 19(4), 259–273. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41260-018-0081-z

- Mun, S. G., & Jang, S. (2015). Working capital, cash holding, and profitability of restaurant firms. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 48, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.04.003

- Nadiri, M. I. (1969). The determinants of real cash balances in the US total manufacturing sector. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 83(2), 173–196. https://doi.org/10.2307/1883079

- Nguyen Thi Thanh Phuong and Dang Ngoc Hung. (2020). Impact of working capital management on firm profitability. Empirical Study in Vietnam. Accounting, 6, 259–266.

- Nguyen, A. T. H., & Van Nguyen, T. (2018). Working capital management and corporate profitability: Empirical evidence from Vietnam. Foundations of Management, 10(1), 195–206. https://doi.org/10.2478/fman-2018-0015

- Nobanee, H., Modar, A, and Maryam Al Hajjar. (2011). Cash Conversion Cycle and Firm’ s Performance of Japanese Firms. www.ssrn.com

- Pakistan Interest Rate. (2016) Trading Economics, http://www.tradingeconomics.com/pakistan/interest-rate

- Peng, J., & Zhou, Z. (2019). Working capital optimization in a supply chain perspective. European Journal of Operational Research, 277(3), 846–856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2019.03.022

- Petersen, M. (2009). Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: Comparing approaches. Review of Financial Studies, 22(1), 435–480. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhn053

- Pham, K. X., Ngoc Nguyen, Q., & Van Nguyen, C. (2020). Effect of Working Capital Management on the Profitability of Steel Companies on Vietnam Stock Exchanges. Journal of Asian Finance Economics and Business, 7(10), 741–750. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.n10.741

- Polak, P., Masquelier, F., & Michalski, G. (2018). Towards Treasury 4.0/The evolving role of corporate treasury management for 2020. Management-Journal of Contemporary Management Issues, 23, 189–197.

- Prasad, P., Narayanasamy, S., Paul, S., Chattopadhyay, S., & Saravanan, P. (2019). Review of literature on working capital management and future research agenda. Journal of Economic Surveys, 33(3), 827–861. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12299

- PWC Annual Report. 2019. Navigating Uncertainty: PwC’s Annual Global Working Capital Study 2018/19 Unlocking Cash to Shore Up Your Business. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/working-capital-management-services/assets/pwc-working-capital-survey-2018-2019.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2020)

- Raheman, A., & Nasr, M. (2007). Working Capital Management and Profitability: Case of Pakistani Firms. International Review of Business Re- Search Papers, 3, 279–300.

- Ren, T., Liu, N., Yang, H., Xiao, Y., & Yijun, H. (2019). Working capital management and firm performance in China. Asian Review of Accounting, 27(4), 546–562. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARA-04-2018-0099

- Richards, V. D. L., & J, E. (1980). A Cash Conversion Cycle Approach to Liquidity Analysis, in. Financial Management, 9(1), S. 32–38. https://doi.org/10.2307/3665310

- Seth, H., Chadha, S., Kumar Sharma, S., & Ruparel, N. (2020). Exploring predictors of working capital management efficiency and their influence on firm performance: An integrated DEA-SEM approach. Benchmarking-An International Journal.

- Sharma, A. K., & Kumar, S. (2011). Effect of Working Capital Management on Firm Profitability: Empirical Evidence from India. Global Business Review, 12, 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/097215091001200110

- Shin, -H.-H., & Soenen, L. (1998). Efficiency of Working Capital Management and Corporate Profitability. Financial Planning and Education, 8(2), 37–45.

- Shin, H., & Soenen, L. (2000). Liquidity Management or Profitability - Is there Room for Both? AFP Exchange, 20(2), 46–49.

- Shrivastava, A., Kumar, N., & Kumar, P. (2017). Bayesian analysis of working capital management on corporate profitability: Evidence from India. Journal of Economic Studies, 44(4), 568–584. https://doi.org/10.1108/JES-11-2015-0207

- Sin Huei, N., Chen, Y., San Ong, T., & Heng Teh, B. (2017). The Impact of Working Capital Management on Firm’s Profitability: Evidence from Malaysian Listed Manufacturing Firms. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 7(3), 662–670.

- Smith, K. V. (1979). Guide to working capital manage- ment.

- Smith, K. (1980). Profitability versus liquidity tradeoffs in working capital management. In Readings on the Management of Working Capital. St. Paul, New York: West Publishing Company.

- Soenen, L. (1993). Cash conversion cycle and corporate profitability. AFP Exchange, 13(4), 53.

- Sonia, B.-C., García-Teruel, P. J., & Martínez-Solano, P. (2020). Net operating working capital and firm value: A cross-country analysis. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 23(3), 234–251. https://doi.org/10.1177/2340944420941464

- Staniewski, M., & Awruk, K. (2019). Entrepreneurial success and achievement motivation—A preliminary report on a validation study of the questionnaire of entrepreneurial success. Journal of Business Research, 101, 433–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.01.073

- Strischek, D. (2001). A Banker’s Perspective on Working Capital and Cash Flow Management. Strategic Finance, 83(4), 38–45.

- Tauringana, V., & Adjapong Afrifa, G. (2013). The relative importance of working capital management and its components to SMEs' profitability. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 20(3), 453–469.

- Tsuruta, D. (2018). Do Working Capital Strategies Matter? Evidence from Small Business Data in Japan. Asia-Pacific Journal of Financial Studies, 47, 824–857.

- Tsuruta, D. (2019). Working capital management during the global financial crisis: Evidence from Japan. Japan and the World Economy, 49, 206–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japwor.2019.01.002

- Ukaegbu, B. (2014). The significance of working capital management in determining firm profitability: Evidence from developing economies in Africa. Research in International Business and Finance, 31, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2013.11.005

- Wang, Y. J. (2002). Liquidity Management, Oper- ating Performance, and Corporate V alue: Evi- dence from Japan and Taiwan. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 12, 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1042-444X(01)00047-0

- Wang, Z., Akbar, M., & Akbar, A. (2020). The Interplay between Working Capital Management and a Firm’s Financial Performance across the Corporate Life Cycle. Sustainability, 12(4), 1661. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041661

- Weinraub, H. J., & Visscher, S. (1998). Industry practice relating to aggressive conservative working capital policies. Journal of Financial and Strategic Decision, 11(2), 11–18.

- Wilson, N., & Summers, B. (2002). Trade credit terms offered by small firms: Survey evidence and empirical analysis. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 29(3‐4), 317–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5957.00434

- Wöhrmann, A., Knauer, T., & Gefken, J. (2012). Kostenmanagement in Krisenzeiten: Rentabilitätssteigerung durch Working Capital Management?. Zeitschrift für Controlling und Management (Sonderheft, 3), 56, 80–85.

- Xavier, G., & Mueller, H. M. (2011). Corporate Governance, Product Market Competition, and Equity Prices. Journal of Finance, 66(2), 563–600. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2010.01642.x

- Yusoff, H., Ahmad, K., Yi Qing, O., & Mohamed Zabri, S. (2018). The relationship between working capital management and firm performance. Advanced Science Letters, 24(5), 3244–3248. https://doi.org/10.1166/asl.2018.11351

- Zaidi, E. (2015). Govt banks’ borrowing surges 30pc till November-end. The News, pp. 1. Retrieved from, December 27 http://www.thenews.com.pk/print/84366-Govt-banks-borrowing-surges-30pc-till-November-end

- Zakaria Soda, M., Hassan Makhlouf, M., Oroud, Y., Al Omari, R., & McMillan, D. (2022). Is firms’ profitability affected by working capital management? A novel market-based evidence in Jordan. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2049671. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2049671