Abstract

Ethical lapses in major corporations continue to draw public attention to the specter of corporate misconduct. This paper presents a pedagogical approach that is designed to enhance student understanding and appreciation of the challenges that business leaders face when confronted with the conflict between the profit-maximizing demands of capitalism and the ethical expectations of society. This is an approach that fully acknowledges the seductive nature of unethical conduct in search of corporate rewards. This paper presents a method which can be applied both in undergraduate and graduate coursework, facilitates the examination of two corruption cases (Enron and WorldCom), and highlights short-term gain versus the eventual long-term pain of unethical behavior.

1. Introduction

In business, profit is king, and money can usurp morals. This is not a modern idea. While some evidence suggests that money is not always corrupting (Storr & Choi, Citation2019; Teague et al., Citation2020), we understand this is not always the case. Even the ancient Greeks warned of money’s corrupting effects, some going so far as to diminish and degrade market activity and trade as non-virtuous (Aristotle, Citation2006). More poignantly, in Plato’s Republic, Glaucon told us the tale of the Ring of Gyges, in which an ordinary man discovers a ring of invisibility and uses it to lie and deceive his way to prosperity (Plato et al., Citation2001).

How could anybody ever expect to do the right thing when faced with a low-risk solution to achieve happiness? Plato, after spending some time discussing justice, eventually answers that this type of happiness is short-lived. Someone that cheats their way to prosperity is not an individual free of the severities of life—instead, they become slaves to their own petty desires. This, perhaps, is not an effective deterrent for everyone. Indeed, in a vacuum, capitalism rewards profit-seeking, not decisions made by individuals to get there. Money is no judge. As such, it is not surprising that we can recall individuals in positions of power that cheated their way to the top or were afforded concessions to unethical behavior. And in many cases, we learn of these individuals because we learn of their consequences and repercussions: fines, jail time, unemployment, and new regulations.

Recent examples of unethical/fraudulent behavior include the Volkswagen emissions scandal wherein the company lost billions in shareholder value, incurred a $25 Billion fine, and had executives sentenced to prison terms (Parloff, Citation2018). Other examples are the Enron collapse and the WorldCom scandal, both of which are discussed in full detail in this paper.

The potentially corrupting influence of money underscores the importance of teaching ethics for business environments. When faced with the choice between money and doing what is right, educators must convince students that ethics wins out. Unfortunately, according to Huhn (Citation2014) subject matter taught in business schools may actually encourage mindsets that diminish the importance of ethical behavior. Further, Parks-Leduc et al. (Citation2021) notes that some research studies have found that business students cheat more often than other college students. Per Warren et al. (Citation2014), cynics assume ethics programs at the corporate level have merely been introduced to avoid prosecution and reduce fines, and thus have limited ability to affect real change. The stakes are high; the challenges, monumental.

2. Literature survey on teaching ethics

Ethics education continues to be a key element of business programs and is increasingly urgent (Raman et al., Citation2019). According to Brenkert (Citation2019) more emphasis is required in both academic and industrial settings. However, the issue of precisely how to introduce ethics to future business managers has been debated for some time with no apparent consensus (Zarzosa & Fischbach, Citation2017). The cases presented in this paper engage business students by focusing on the perceived short-term pleasure of unethical behavior contrasted with its “other” face—very real long-term pain.

The predominance of unethical business behavior emanates from the subconscious justification that “if it’s legal, it must be ethical.” However, there are many differences between ethics and the law. Laws change over time. For example, when Frank Lorenzo took Continental Airlines into bankruptcy to effectively void union contracts, society judged his actions as legal but unethical. By the time he attempted the Eastern Airlines take-over, the exact same bankruptcy tactics had become illegal. Also, laws vary from state to state. Frequently, political and economic interests determine which laws get passed. Ethical standards, however, transcend time, place and the whims of politics. Ethical decisions have multiple alternatives, extended consequences and personal implications. Callanan and Tomkowicz (Citation2011) deftly uses a case involving debit card overdraft fees to highlight the critical difference between purely legal and ethical behavior.

Traditional methods of teaching ethics include principles-based approaches with case studies (Cagle & Baucus, Citation2006; Falkenberg & Woiceshyn, Citation2008; Laditka & Houck, Citation2006), critiques of unethical behavior (Cagle et al., Citation2008), and the study of professional codes. Zych (Citation1999) suggests that the teaching of ethics needs realistic business problems where students apply ethical principles. In this approach, ethical dilemmas are presented as “business problems.” McWilliams and Nahavandi (Citation2006), for example, advocates the use of “live” cases involving currently unfolding business situations. Further, Kwak and Price (Citation2012) concludes that “peer-teaching” significantly enhances student understanding of ethical issues.

Approaches to teaching ethics that involve critical thinking vary widely. Hartman (Citation2006) espouses teaching character simply by using case studies and a process Aristotle called dialectic. Marquis (Citation2003) believes that analytical skills are the key to ethical decision-making and that the humanities faculty (especially the English faculty) is in a unique position to pass on skills of analysis. In this approach, an examination of literature is the key technique. Apostolou and Apostolou (Citation1997) requires each student to identify his or her personal hero where “hero” implies a person noted for nobility, courage, outstanding achievement, etc. The hero then serves as a personal model, or a proxy, for the individual’s personal value system, externalizing a moral code to be referenced during times of ethical struggle. This approach presumes that, in all likelihood, ethical standards (good or bad) are already in place by the time students enter college and that, per Cordtz (Citation1994), the real purpose of ethics education is to help already ethical people deal with moral problems that arise in business. Cuilla (Citation2011) discusses the importance of studying business history in understanding business ethics, noting that the same ethical problems in business have been around for a long time.

Elias and Farag (Citation2011) investigates the impact of personality variables on a student’s ability to perceive ethical breaches and concluded that Type A personalities and students who exhibited low opportunism were best able to detect fraudulent behavior. Gu and Neesham (Citation2014) describes a technique which appeals to a student’s “moral identity” versus reliance on rule-based ethics. O’Leary and Stewart (Citation2013) advocates matching learning styles and teaching methodology while Schmidt et al. (Citation2013) suggests “deliberate psychological education.”

Other approaches include the use of cinema to underscore ethical training (Biktimirov & Cyr, Citation2013; Cox et al., Citation2009; O’Boyle & Sandonà, Citation2014) and debate (Peace, Citation2011; Schumann et al., Citation2006). The debate technique is improved upon by Schrag (Citation2009) which features student role-playing within the context of an actual case. An intriguing approach is described in Singer (Citation2013) wherein students adopt two different perspectives—a business as usual view and an obviously more ethical point of view—and are challenged to craft a compromise. Mamgain (Citation2010) describes a process wherein students can cultivate a sense of ethical consciousness by using Buddhist practices to develop empathy and compassion. Collins et al. (Citation2014) provides a framework for teaching business ethics via an online course. Sexton and Garner (Citation2020) conducted a study of ethics training, soliciting student reactions to various methods. In that study, students were partial to group discussion and guest speakers.

Even Mark Twain (Mark Twain’s Speeches, Citation1910) weighed in with a technique to find the path to righteousness. He said: “By commission of crime you learn real morals. Commit all the crimes, familiarize yourself with all sins, take them in rotation (there are only two or three thousand of them), stick to it, commit two or three every day, and by-and-by you will be proof against them.”

3. Why is unethical behavior so intractable?

Business ethics training is considered helpful in minimizing the risk of employees becoming involved in corrupt behavior (Kaptein, Citation2015). However, corruption and unethical behavior are quite widespread and are often viewed as an unavoidable consequence of business pressure (Becker et al., Citation2013; Hauser, Citation2017; Transparency International, Citation2016). Given the expectation of society and pervasive ethics training, how can “better angels” not prevail? An examination of Neutralization Theory and the “Fraud Triangle” provides powerful clues as to why this condition persists.

Any successful method of teaching business ethics which seeks to act a barrier against unethical behavior must overcome the internal messages that perpetrators use to justify their behavior. Fittingly, the study of this human tendency is referred to as Neutralization Theory and is a generally accepted framework for explaining how “bad actors” justify their actions by reducing the negative emotion associated with bad behavior (Fritsche, Citation2005). Neutralization Theory holds (falsely) that there is a just and good reason for unethical/corrupt behavior because:

The overall good of the company is served (Rabl & Kuhlmann, Citation2009).

Using utilitarian principles, the greater good is served such as perpetrating accounting fraud to save employee jobs (Murphy & Dacin, Citation2011).

There is no obvious harm. The victim is unknown to the perpetrators or intellectually abstract (Healy & Palepu, Citation2003).

The survival of the perpetrator is at stake. Corruption is therefore necessary and justified (Smallridge & Roberts, Citation2013).

Everyone else is doing the same thing so it is necessary to maintain a level playing field (McKinney & Moore, Citation2008).

The legitimacy of anti-corruption practices is challenged on cultural grounds (Rabl, Citation2012).

The prevailing bureaucratic environment is an obstacle and must be circumvented (Rabl & Kuhlmann, Citation2009).

These linguistic devices, held in the mind of the perpetrator, enable them to engage in unethical/corrupt behavior without damaging their positive self-image and without violating social norms.

All auditors are familiar with the “fraud triangle” which is credited to Donald Cressey (Wells, Citation2008). The triangle describes three stimuli for an employee or employees (line or executive) to commit fraud: Motivation, Perceived Opportunity and Rationalization:

Motivation is the financial or emotional push toward illegal or unethical behavior. For line employees, financial pressure might include greed, addiction, poor credit rating, or poor cash management; work pressures might be dissatisfaction with pay or overlooked for promotion. At the executive level, the motivation escalates and might include: I want and deserve more money, better title, higher position, more authority or perks. Executives may feel I am better, smarter, more skilled, or superior.

Perceived Opportunity describes the ability to execute the malfeasance without being caught. Examples might be weak internal controls, assets susceptible to fraud, ignorance, apathy, no ability to detect fraud. At the executive level, “I control the books. I will not be questioned.”

Rationalization is the personal justification for dishonest behavior such as: I’ll pay it back. I deserve the money or promotion or recognition anyway. It’s good for the company; the employees; the customers; the stock holders. Everyone does it. Nobody will get hurt.

However, the Perceived Opportunity has an uncomfortable side—one which is rarely considered. Individual dishonesty can frequently be concealed by the individual acting alone. Illegal or unethical behavior involving many (more than one) will inevitably be uncovered. Further the damage will fan out to envelop many employees, the corporation, additional affiliated corporations and all the stakeholders. The cases described in this paper will illustrate this point.

4. Description of the approach

Because corporations can, in the short-term, benefit by responding to the siren-song of unethical behavior, and because there is an apparent breakdown in personal standards of behavior which might halt incorrect choices, the approach detailed below presents the short-term benefits versus the long-term distress of following the wrong path.

With regard to teaching approach design, Medeiros (Citation2017) determined that guided training is more effective than self-directed training and case-based training is more effective than lecture-based training. And so, this paper describes an instructor-guided, case-oriented teaching approach that focuses on the relationships among business, society, and government. The approach utilizes well known business scandals. Specifically, we will address the legal and ethical issues contained within the Enron and WorldCom scandals.

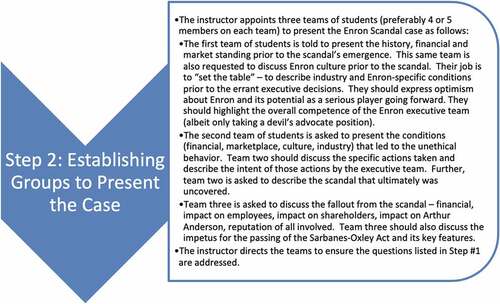

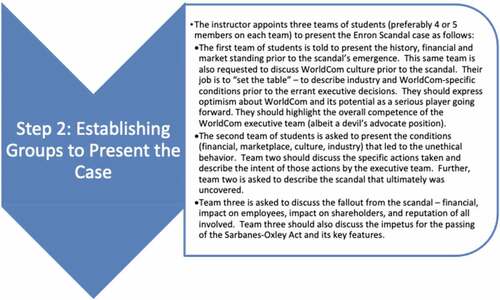

The teaching approach, which can be applied both in undergraduate and graduate coursework, facilitates the examination of two cases (Enron and WorldCom) in a required Management course (e.g., Business and Society). The approach features a discussion among three student groups. The first group presents the industry and corporation-specific conditions, including financial success to date; that is, the benefits of bad behavior. The second group describes the conditions (culture, external influences, bad judgment) leading to the unethical behavior. The third group assesses the damage measured in profit and reputation. The approach’s success is based upon creating a memorable event highlighting the short-term gain versus the eventual long-term pain of unethical decision-making. The best sessions feature student groups presenting their piece of the story with a healthy dose of melodrama (as encouraged by the instructor).

The cases are thorough and are designed for immediate use by instructors with all essential elements:

Self-Contained preparatory reading assignment ready for distribution to students.

Teaching objectives.

Structure and timing of the session with all roles described.

Probing discussion questions with suggested answers.

Session conclusion points with suggested key take-aways.

Summary of learnings with suggested points.

Contained in Appendix A are the case teaching notes and case analysis questions that can be utilized when presenting the Enron Scandal case within a Business and Society management course (or a related management course). From the business and society perspective, as reflected in Appendix A, the case can be used to reinforce a number of learning outcomes, including the need for organizations to be socially responsible and ethical, the reputational and financial risk that can result from unethical practices that might generate financial success in the short run but be financially damaging in the long run, and finally, and the role that government plays in dictating corporate policy in the aftermath of such scandals. Appendix B contains background information on the Enron Scandal to be used by the instructor as a preparatory reading assignment for the class.

Appendix C contains the case teaching notes and case analysis questions analogous to Appendix A, but dedicated to the WorldCom case. Although the Enron Scandal is perfectly suited to this approach for teaching ethical behavior, the case is well known. The instructor may wish to alternate between the well-known Enron Scandal and the lesser known, yet equally instructive, WorldCom case. Also, the WorldCom case is particularly useful when the management course is an International Business course. The WorldCom case features a major global player, international law, and both U.S. and European corporations. Appendix D contains background information on the WorldCom case to be used by the instructor as a preparatory reading assignment for the class.

Independent of which case is selected, the core message for the instructor to communicate to business students remains the same: Although there are highly ethical business leaders whose behavior is ideal in any condition, they are rare (Callanan et al., Citation2010). Students need to be aware that unethical behavior (illegal or not), such as hiding financial liabilities, improperly accelerating revenue, capitalizing operating expense, lying to customers, manipulating suppliers, deceiving auditors, or abusing employees, may, in the short term, generate financial rewards. However, there will be a price (a steep one) to pay. There are simply too many stakeholders. The truth cannot be hidden forever.

5. Conclusion

Ethics training for business students is critical. Indeed, the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB), the most prestigious accrediting body for colleges of business, requires in Standard 9 that colleges incorporate business ethics into the curriculum (AACSB, Citation2018). Unfortunately, unethical decisions have been made by business leaders for as long as the free market has existed. The desire and the pressure to maximize profits is compelling and at times overwhelming to the leaders of capitalistic businesses. Indeed, the pressures to meet certain performance goals can, in a sense, blind organizational leaders from fully considering the ethical implications of their actions and policies. Recall, money is no judge.

Many methods of teaching business ethics have been attempted. Long-term positive impact has been elusive. An exploration of Neutralization theory and the Fraud Triangle has clarified the scale of the challenge. The pedagogical approach described in this paper goes right to the point: the pleasure of unethical behavior is temporary; the pain is severe and long-lasting.

The cases described in this paper gives students the chance to gain a better understanding and awareness of the decision-making pressures that challenge leaders of capitalist organizations on a daily basis. By raising this awareness, it is hoped current and future business leaders, when presented with a ring of invisibility, will eschew it; that is, they will make ethical and socially responsible decisions that are balanced, reasonable, and defensible, in both the short and long terms.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- AACSB International. (2018). Eligibility procedures and accreditation standards for business accreditaion. AACSB (Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business).

- AccountancyAge. (August112005). Sullivan gets five years for WorldCom fraud, http://accountancyage.com/aa/news/1770276/sullivan-workdcom-fraud, accessed July 1, 2014

- AccountancyAge. (July312006). WorldCom Boss Loses Appeal, http://accountancyage.com/aa/news/1788137/worldcom-boss-loses-appeal, accessed July 1, 2014

- Apostolou, B., & Apostolou, N. (1997). Heroes as a context for teaching ethics. Journal of Education for Business, 73(2), 121–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/08832329709601628

- Aristotle, U. (2006). Politics. ReadHowYouWant. Com.

- Becker, K., Hauser, C., & Kronthaler, F. (2013). Fostering management education to deter corruption: what do students know about corruption and its legal consequences? Crime, Law, and Social Change, 60(2), 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-013-9448-8

- Bennet, J. (August2005). Third Ex WorldCom Exec Jailed, AccountancyAge, http://www.accountancyage.com/aa/news/1753576/third-worldcom-exec-jailed, accessed July 1, 2014

- Biktimirov, E., & Cyr, D. (2013). Using inside job to teach business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(1), 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1516-y

- Brenkert, G. (2019). Mind the Gap! The challenges and limits of (global) business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 155(4), 917–930.

- Cagle, J. B., & Baucus, M. S. (2006). Case studies of ethics scandals: Effects on ethical perceptions of finance Students. Journal of Business Ethics, 64(3), 213–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-005-8503-5

- Cagle, J., Glasgo, P., & Holmes, V. (2008). Using Ethics Vignettes in Introductory Finance Classes: Impact on Ethical Perceptions of Undergraduate Business Students. Journal of Education for Business, 84(2), 76–83. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.84.2.76-83

- Callanan, G., Rotenberry, P., Perri, D., & Oehlers, P. (2010). Examining the Influence of Contextual Factors on the Relationship Between Ethical Ideology and Decision-Making. International Journal of Management, 27(1), 52–75.

- Callanan, G., & Tomkowicz, S. 2011. Legal Yes, Ethical No: Using the Case of Debit Card Overdraft Fees as a Business Ethics Teaching Tool. Journal of the Academy of Business Education 2011, Fall 85–100

- Carozza, D. ( March 2008). Extraordinary Circumstances: An Interview with Cynthia Cooper, Fraud Magazine. The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners. http://www.fraud-magazine.com/article.aspx?id=210 accessed July 1, 2014.

- Clarke, T. (2013). International Corporate Governance. Routledge.

- Collins, D., Weber, J., & Zambrano, R. (2014). Teaching business ethics online: Perspectives on course design, delivery, student engagement, and assessment. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(3), 513–529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1932-7

- Cooper, C. (2008). Extraordinary Circumstances: The Journey of a Corporate Whistleblower. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Cordtz, D. 1994. Ethicsplosion! Financial World Fall 58–60

- Cox, P., Friedman, B., & Edwards, A. (2009). Enron: The smartest guys in the room – using the Enron film to examine student attitudes towards business ethics. Journal of Behavior & Applied Management, 10(2), 263–290.

- Cuilla, J. (2011). Is business ethics getting better? A historical perspective. Business Ethics Quarterly, 21(2), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.5840/beq201121219

- Department of Justice. (1998). http://www.justice.gov/atr/public/press_releases/1998/1829.htm, accessed July 19, 2014

- Eichenwald, K. (2002). For WorldCom, acquisitions were behind its rise and fall, http://pythonkit.com/For-WorldCom,Acquisitions-Were-Behind-Its-Rise-and-Fall-download-w18533.pdf accessed July 1, 2014

- Elias, R., & Farag, M. 2011. The impact of accounting students’ type a personality and cheating opportunity on their ethical perception. Journal of the Academy of Business Education, 12, Fall, 71–84.

- Elkind, P., & McLean, B. (July22004). Ken lay flunks ignorance test. Fortune.

- Falkenberg, L., & Woiceshyn, J. (2008). Enhancing business ethics: Using cases to teach moral reasoning. Journal of Business Ethics, 79(3), 213–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9381-9

- Fowler, T. (October2002). The Pride and the Fall of Enron. Houston Chronicle.

- Fritsche, I. (2005). Predicting Deviant Behavior by Neutralization: Myths and Findings. Deviant Behavior, 26(5), 483–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/016396290968489

- Gu, J., & Neesham, C. (2014). Moral identity as leverage point in teaching business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 124(3), 527–536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-2028-0

- Harmantzis, F. C. (2004) Inside the telecom crash: bankruptcies, fallacies and scandals – a closer look at the WorldCom case. Social Science Research Network. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=575881, accessed July 1, 2014.

- Hartman, E. (2006). Can we teach Character? Academy of Management Learning & Education, 5(1), 68–81. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2006.20388386

- Hauser, C. (2017). Fighting against corruption: Does anti-corruption training make any difference. Journal of Business Ethics, 159, 281–299.

- Healy, P. M., & Palepu, K. G. (2003). The Fall of Enron. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(2), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1257/089533003765888403

- Huhn, M. P. (2014). You Reap What You Sow: How MBA Programs Undermine Ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 121, 527–541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1733-z

- Kaptein, M. (2015). The Effectiveness of Ethics Programs: The Role of Scope, Composition, and Sequence. Journal of Business Ethics, 132(2), 415–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2296-3

- Kwak, L., & Price, M. 2012. Project-Based Peer Teaching on Socially Responsible Business. Journal of the Academy of Business Education, 13, Fall, 55–70.

- Laditka, S., & Houck, M. (2006). Student-Developed Case Studies: An Experiential Approach for Teaching Ethics in Management. Journal of Business Ethics, 64(2), 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-005-0276-3

- Mamgain, V. (2010). ethical consciousness in the classroom: How Buddhist practices can help develop empathy and compassion. Journal of Transformative Education, 8(1), 22–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344611403004

- Mark Twain’s Speeches. 1910. Mark Twain Speeches. Harper & Brothers

- Marquis, M. (2003). Using literature to teach ethics. Kentucky Journal of Economics & Business, 22, 53–60.

- McClam, E. (February112009). Former WorldCom Exec Gets Prison, http://www.cbsnews.com/2100-201_162-770079.htm?pageNum=1&tag=page, accessed July 1, 2014

- McKinney, J. A., & Moore, C. W. (2008). International bribery: Does a written code of ethics make a difference in perceptions of business professionals. Journal of Business Ethics, 79(1–2), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9395-3

- McLean, B. (December9, 2001). Why Enron went bust. Fortune.

- McLean, B., & Elkind, P. 2003. The smartest guys in the room. The Amazing Rise and Scandalous Fall of Enron, Portfolio Trade (reprinted 2004).

- McLean, B., & Elkind, P. (October132003). Partners in Crime. Fortune.

- McLean, B., & Elkind, P. (October22003). Excerpt from the smartest guys in the room. Fortune.

- McWilliams, V., & Nahavandi, A. (2006). Using live cases to teach ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 67(4), 421–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9035-3

- Medeiros, K. E., Watts, L. L., Mulhearn, T. J., Steele, L. M., Mumford, M. D., & Connelly, S. (2017). What is working, what is not, and what we need to know: A meta-analytic review of business ethics instruction. Journal of Academic Ethics, 15(3), 245–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-017-9281–2

- Murphy, P. R., & Dacin, M. T. (2011). Psychological pathways to fraud: Understanding and preventing fraud in organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 101(4), 601–618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0741-0

- O’Boyle, E., & Sandonà, L. (2014). Teaching business ethics through popular feature films: An experiential approach. Journal of Business Ethics, 121(3), 329–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1724-0

- O’Leary, C., & Stewart, J. (2013). The Interaction of Learning Styles and Teaching Methodologies in Accounting Ethical Instruction. Journal of Business Ethics, 113(2), 225–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1291-9

- Parks-Leduc, L., Mulligan, L., & Rutherford, M. A. (2021). Can ethics be taught? Examining the impact of distributed ethical training and individual characteristics on ethical decision-making. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 20(1), 30–49. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2018.0157

- Parloff, R. (2018February6). How VW Paid $25Billion for “Dieselgate” – And Got Off Easy, Fortune, https://fortune.com/2018/02/06/volkswagen-vw-emissions-scandal-penalties/

- Peace, A. G. (2011). Using Debates to Teach Information Ethics. Journal of Information Systems Education, 22(3), 223–237.

- Plato, F., R, G., & Griffith, T. (2001). The Republic. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Rabl, T. (2012). Do Contextual Factors Matter. Zeitschrift fur Betriebswirtschaft, 82(S6), 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-012-0629-1

- Rabl, T., & Kuhlmann, T. M. (2009). Why or Why Not? Rationalizing Corruption in Organizations. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 16(3), 268–286. https://doi.org/10.1108/13527600910977355

- Raman, G. V., Garg, S., & Thapliyal, S. (2019). Integrative live case: A contemporary business ethics pedagogy. Journal of Business Ethics, 155(4), 1009–1032. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3514-6

- Schmidt, C. D., Davidson, K. M., & Adkins, C. (2013). Applying what works: A case for deliberate psychological education in undergraduate business ethics. Journal of Education for Business, 88(3), 127–135.

- Schrag, P. G. (2009). Teaching Legal Ethics through Role Playing. Legal Ethics, 12(1), 35–57.

- Schumann, P. L., Scott, T. W., & Anderson, P. H. (2006). Designing and introducing ethical dilemmas into computer-based business simulations. Journal of Management Education, 30(1), 195–219.

- Sexton, R., & Garner, B. (2020). Student perspectives of effective pedagogical strategies for teaching ethics. Marketing Education Review, 30(2), 132–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/10528008.2020.1756339

- Singer, A. E. (2013). Teaching ethics cases: A pragmatic approach, Business Ethics: A European Review. 22(1), 16–31.

- Smallridge, J. L., & Roberts, J. R. (2013). Crime Specific Neutralization: An Empirical Examination of Four Types of Digital Privacy. International Journal of Cyber Criminology, 7(2), 125–140.

- Storr, V. H., & Choi, G. S. (2019). Do markets corrupt our morals? Palgrave Macmillan.

- Teague, M. V., Storr, V. H., & Fike, R. (2020). Economic freedom and materialism: An empirical analysis. Constitutional Political Economy, 31(1), 1–44.

- Time Magazine. (2002). Chronology of a Collapse, http://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,2021097_2021123_2021121,00.html, accessed June 28, 2014.

- Transparency International. (2016). Corruption Perceptions Index 2015. Springer.

- Warren, D. E., Gaspar, J. P., & Laufer, W. S. (2014). Is Formal Ethics Training Merely Cosmetic? A Study of Ethics Training and Ethical Organization Culture. Business Ethics Quarterly, 24(1). https://doi.org/10.5840/beq2014233

- Wells, J. (2008). Principles of Fraud Examination. Wiley.

- Zarzosa, J., & Fischbach, S. (2017). Native advertising: Trickery or technique? an ethics project and debate. Marketing Education Review, 27(2), 104–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/10528008.2017.1304161

- Zych, J. (1999). Integrating Ethical Issues with managerial decision making in the classroom: Product support program decisions. Journal of Business Ethics, 18(3), 255–266.

Appendix A:

Using the Enron Scandal Case as a Discussion Tool in a Business and Society Session

Overview

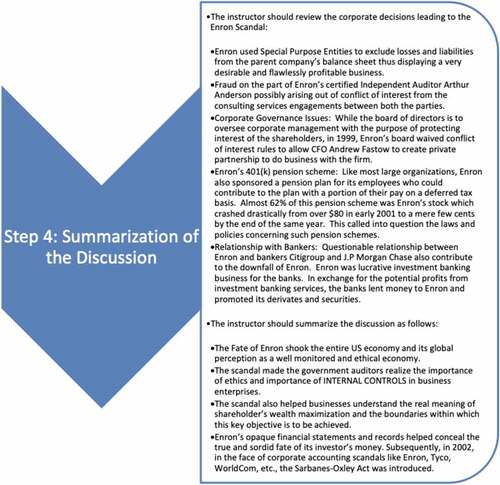

The genesis the Enron scandal, and the issues surrounding it, can reinforce a variety of learning outcomes in management courses such as Business and Society. First, discussion can focus on how companies must guard against unethical behavior in the face of both internally and externally-generated financial pressures. As the facts of the Enron Scandal demonstrate, Enron executives fell woefully short in this regard despite a sound corporate code of ethics. The case can highlight how long-term reputational and financial risk will result from unethical behaviors that might generate financial gain in the short-term. Finally, the Enron Scandal presents a crystal-clear example of how the actions (or inactions) of business can lead to changes in the laws regarding financial oversight.

Course Usage

The primary audience is business students, either at the undergraduate or graduate levels, who are taking a business and society or related course. This pedagogical approach is recommended to be used while students are engaged in coursework or instruction in corporate social responsibility or business ethics. In general, the professor can use the Enron Scandal case and the in-class discussion to enhance student understanding of corporate social responsibility, business ethics, and the consequences of managerial decision-making.

Teaching Objectives

The teaching objectives of this session are as follows:

To have students understand how companies can and should engage in socially responsible and ethical corporate decision-making by ensuring adherence to the law and generally-accepted accounting principles as well as a well-defined code of conduct.

To have students understand that businesses must balance short-term profit motives with long-term viability and societal acceptance.

To have students understand the consequence of government-imposed regulation (in this case, Sarbanes-Oxley) as a response to corporate misbehavior.

To have students recognize that government (lawmakers and/or industry regulators) and societal mores both serve as the ultimate arbiters in the relationship between business and society.

Description of the Approach

This session (within a Business and Society course) involves a series of steps that facilitate a focused in-class discussion highlighting how the paradox between the profit-maximizing demands of capitalism can be reconciled with the ethical expectations of society. In terms of expected outcomes, participants in the teaching session should gain a better understanding of the day-to-day challenges faced by business leaders as they attempt to satisfy the dual demands of shareholders and customers in an increasingly competitive global marketplace. The teaching session will sensitize students to business strategies that might prompt accusations of unethical behavior. Further, the session will highlight the fact that short-term corporate gain due to unethical behavior is commonly followed by long-term financial decline and loss of reputation.

This framework can be used either prior to or after the students have been exposed to actual coursework or instruction in ethics and ethical decision making. If it is used prior to the coursework, then the students’ reactions to the case would likely be more visceral since they would not be influenced by formal instruction in ethics. If it is used after the coursework in ethics is completed, then the students should show a greater appreciation of the competing forces that frame an ethical challenge. Either way, the instructor can use the case and the ensuing debate to enhance student understanding of ethical decision making and leadership.

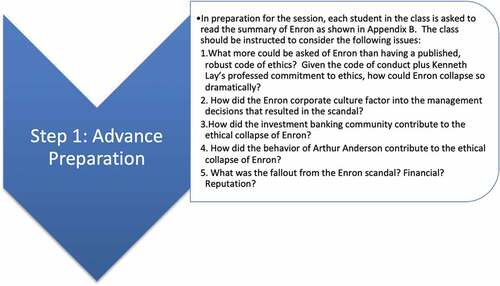

The specific steps in the teaching session are described below.

Questions and sample responses are as follows:

What were the tenets of the Enron code of ethics?

Enron’s ethics code was based on respect, integrity, communication, and excellence. These values were described as follows:

• Respect. We treat others as we would like to be treated ourselves. We do not tolerate abusive or disrespectful treatment. Ruthlessness, callousness and arrogance don’t belong here.

• Integrity. We work with customers and prospects openly, honestly and sincerely. When we say we will do something, we will do it; when we say we cannot or will not do something, then we won’t do it.

• Communication. We have an obligation to communicate. Here we take the time to talk with one another … and to listen. We believe that information is meant to move and that information moves people.

• Excellence. We are satisfied with nothing less than the very best in everything we do. We will continue to raise the bar for everyone. The great fun here will be for all of us to discover just how good we can really be.

(2)What more could be asked of Enron than having a published, robust code of ethics?

Given the code of conduct plus Kenneth Lay’s professed commitment to ethics, how could Enron collapse so dramatically?

The activities of Skilling, Fastow, and Lay raise questions about how closely they adhered to the values of respect, integrity, communication, and excellence articulated in the Enron Code of Ethics. Before the collapse, when Bethany McLean, an investigative reporter for Fortune magazine, was preparing an article on how Enron made its money, she called Enron’s then-CEO, Jeff Skilling, to seek clarification of its “nearly incomprehensible financial statements.” Skilling became agitated with McLean’s inquiry, told her that the line of questioning was unethical, and hung up (McLean, CitationDecember9, 2001).

Fastow engaged in several activities that challenge the foundational values of the company’s ethics code. Fastow setup and operated partnerships (named after family members) called “related party transactions” to do business with Enron. In the process of allowing Fastow to set and run these very lucrative private partnerships, Enron’s board and top management gave Fastow an exemption from the company’s ethics code.

Contrary to the federal prosecutor’s indictment of Lay, which describes him as one of the key leaders and organizers of the criminal activity and massive fraud that led to Enron’s bankruptcy, Lay maintained his innocence and lack of knowledge of what was happening. He blamed virtually all of the criminal activities on Fastow (McLean & Elkind, Citation2003). However, Sherron Watkins, the key Enron whistleblower, provided examples of Lay’s questionable decisions and actions. Ultimately, the actions of Enron’s leadership did not match the company’s expressed vision and values.

With the guidance of the professor, students can draw conclusions on the actions of Enron and whether these actions were within the spirit of the code of ethics and were socially responsible and ethical. Here a general discussion of hypocrisy will naturally arise. Examples drawn from politicians, disgraced televangelists, and other persons in the public eye are numerous and illustrative.

(3)How did the Enron corporate culture factor into the management decisions that resulted in the scandal?

Enron has been described as having a culture of arrogance that led people to believe that they could handle increasingly greater risk without encountering any danger. According to Sherron Watkins, Enron’s unspoken message was, “Make the numbers, make the numbers, make the numbers—if you steal, if you cheat, just don’t get caught.” Enron’s corporate culture did little to promote the values of respect and integrity (Fowler, CitationOctober, 2002).

Skilling implemented a very rigorous and threatening performance evaluation process for all Enron employees. Known as “rank and yank,” the annual process utilized peer evaluations, and each of the company’s divisions was arbitrarily forced to fire the lowest ranking one-fifth of its employees. Employees frequently ranked their peers lower in order to enhance their own positions in the company (McLean, CitationDecember9, 2001).

Enron’s compensation plan “seemed oriented toward enriching executives rather than generating profits for shareholders” and encouraged people to break rules and inflate the value of contracts even though no actual cash was generated. Enron’s bonus program encouraged the use of non-standard accounting practices and the inflated valuation of deals on the company’s books (McLean & Elkind, Citation2003).

(4)How did the investment banking community contribute to the ethical collapse of Enron?

According to investigative reporters (McLean & Elkind, Citation2003), one of the most sordid aspects of the Enron scandal is the complicity of so many highly regarded Wall Street firms in enabling Enron’s fraud as well as being partners to it. This complicity occurred through the use of “prepays” which were basically loans that Enron booked as operating cash flow. Enron secured new prepays to pay off existing ones.

One of the related party transactions created by Andrew Fastow, known as LJM2, used a tactic whereby it would take an asset off Enron’s hands—usually a poor performing asset, usually at the end of a quarter—and then sell it back to the company at a profit once the quarter was over and the “earnings” had been booked. Such transactions were basically smoke and mirrors, reflecting a relationship between LJM2 and the banks wherein “Enron could practically pluck earnings out of thin air.”

(5)How did the behavior of Arthur Anderson contribute to the ethical collapse of Enron?

The consulting arm of Arthur Anderson was performing lucrative consulting engagements at the direction of the Enron executive team. When the audit side of the Arthur Anderson house identified concerning transactions, they were prevailed upon to sweep it under the carpet to avoid annoying the Enron executives, to ensure the Enron – Arthur Anderson business relationship stayed solid, and, mostly, to ensure future consulting engagements. This exposed a major conflict of interest in the business model of many public accounting firms.

(6)What was the fallout from the Enron scandal? Financial? Reputation?

The Enron Code of Ethics and its foundational values of respect, integrity, communication, and excellence obviously did little to help create an ethical environment at the company. In the aftermath of Enron’s bankruptcy filing, numerous Enron executives were charged with criminal acts, including fraud, money laundering, and insider trading.

Andrew Fastow, Jeffery Skilling, and Kenneth Lay are among the most notable top-level executives implicated in the collapse of Enron’s “house of cards.” Andrew Fastow, former Enron chief financial officer (CFO), faced 98 counts of money laundering, fraud, and conspiracy in connection with the improper partnerships he ran. Fastow pled guilty to one charge of conspiracy to commit wire fraud and one charge of conspiracy to commit wire and securities fraud. He agreed to a prison term of 10 years and the forfeiture of $29.8 million. Skilling was indicted on 35 counts of wire fraud, securities fraud, conspiracy, making false statements on financial reports, and insider trading. Kenneth Lay was indicted on 11 criminal counts of fraud and making misleading statements (McLean & Elkind, Citation2003).

Juries have convicted five individuals of fraud, as well as Arthur Andersen, the accounting firm hired by Enron that shared responsibility for the company’s fraudulent accounting statements.

In summary, both Enron and Arthur Anderson – reputations in tatters – were ruined financially due to unethical behavior in the face of codes of conduct and, the then in place, industry oversight – short term gain, long term pain.

Time Requirement

The total time needed for the session as described above is somewhat flexible depending on the timing of general coursework dealing with ethics and the amount of time allotted for the team presentations and the full class discussion. Experience indicates that this teaching session will take from 60 to 90 minutes to complete but could be expanded depending on the nature of the course. Of course, this approach should be used in conjunction with a full lecture or discourse on business ethics and ethical decision making.

Optional Extension of the Session

The instructor can ask students to investigate and report on other high-profile cases of failure in corporate social responsibility and business ethics. (Students may be asked to identify cases as a homework assignment.) In the selected cases, the breach and subsequent government/societal response can be identified. Some candidate cases are as follows:

American Airlines: Deferred maintenance of aircraft.

Firestone Tire and Rubber Company: Use of child labor.

Lockheed: Bribery in Germany, Japan and the Netherlands.

HealthSouth: Misrepresented earnings.

Deutsche Bank: Spying

Halliburton: Overcharging on government contracts

Wal-Mart: Payoff scandal in Mexico

HSBC Holdings: Money laundering scheme

Appendix B:

Background on the Enron Scandal

Enron Corporation was an American energy, commodities, and services company based in Houston, Texas. At its peak, Enron employed approximately 20,000 people and was one of the world’s largest electricity, natural gas, communications, and pulp and paper companies. With revenues of approximately $100 billion, Enron was named “America’s Most Innovative Company” for six consecutive years by Fortune magazine.

Enron’s line of business originally involved transmitting and distributing electricity and natural gas throughout the United States. The company developed, built, and operated power plants and pipelines while dealing with rules of law and other infrastructures worldwide. Enron owned a large network of natural gas pipelines, which stretched ocean to ocean and border to border. Enron traded in more than 30 different products, including petrochemicals, power, pulp and paper, steel, weather risk management, and oil and natural gas transportation.

The1990ʹs corporate self-regulation in the United States of America had been widely thought to have reached a high plateau of evolutionary success due to sophisticated institutional monitoring. However, the bankruptcy of Enron shook the entire system. Many of Enron’s recorded assets and profits were inflated and/or fraudulent or nonexistent. Debts and losses were put into entities formed “offshore” that were not included in the company’s financial statements. Other sophisticated and arcane financial transactions between Enron and related companies were used to eliminate unprofitable entities from the company’s books. Some figures brought to light when the scandal was exposed included $30 million of self-enrichment by the chief financial officer, $700 million of net earnings disappearing, $4 billion in liabilities hidden from view, and $1.2 billion in shareholders equity evaporating. In the end, both Enron and its auditor Arthur Anderson were financially destroyed and/or completely discredited (excerpted from: Healy & Marquis, Citation2003; McLean & Elkind, Citation2003).

Key Players in the Enron Scandal are described in :

Table B1. The below table presents the key players and facts regarding their role in the Enron Scandal

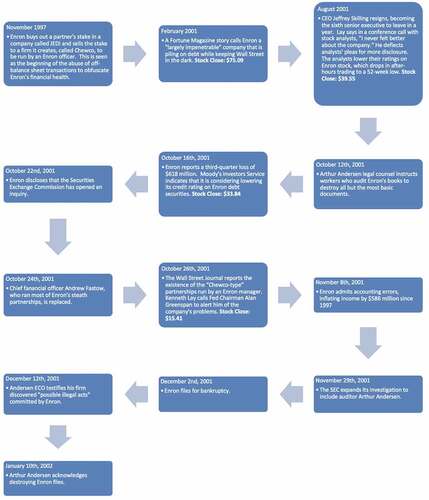

Key Dates of the Enron Scandal (Time Magazine, Citation2002):

The below figure B2 shows the timeline of events which occurred during the Enron Scandal (Time Magazine, Citation2002).

Appendix C:

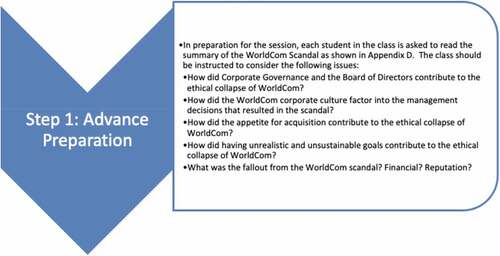

Using the WorldCom Scandal Case as a Discussion Tool in a Business and Society Session

Overview

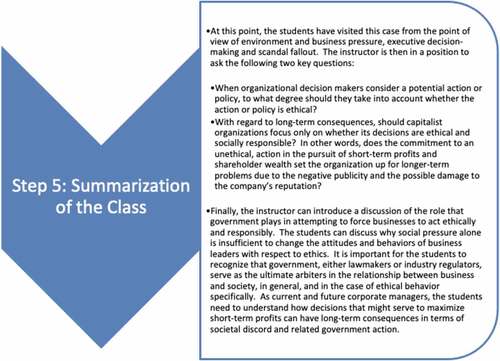

The genesis and the issues surrounding the WorldCom scandal can reinforce a variety of learning outcomes in management courses such as Business and Society. First, discussion can focus on how companies must guard against unethical behavior in the face of both internally and externally-generated financial pressures. As the facts of the WorldCom Scandal demonstrate, WorldCom executives fell woefully short in this regard despite a sound corporate code of ethics. The case can highlight how long-term reputational and financial risk will result from unethical behaviors that might generate financial gain in the short-term. Finally, the WorldCom Scandal presents a crystal-clear example of how the actions (or inactions) of business can lead to changes in the laws regarding financial oversight.

Course Usag

The primary audience is business students, either at the undergraduate or graduate levels, who are taking a business and society or related course. This pedagogical approach is recommended to be used while students are engaged in coursework or instruction in corporate social responsibility or business ethics. In general, the professor can use the WorldCom Scandal case and the in-class discussion to enhance student understanding of corporate social responsibility, business ethics, and the consequences of managerial decision-making.

Teaching Objective

The teaching objectives of this session are as follows:

To have students understand how companies can and should engage in socially responsible and ethical corporate decision-making by ensuring adherence to the law and generally-accepted accounting principles as well as a well-defined code of conduct.

To have students understand that businesses must balance short-term profit motives with long-term viability and societal acceptance.

To have students understand the consequence of government-imposed regulation (in this case, Sarbanes-Oxley) as a response to corporate misbehavior.

To have students recognize that government ((lawmakers and/or industry regulators) and societal mores both serve as the ultimate arbiters in the relationship between business and society.

Description of the Approach

This session (within a Business and Society course) involves a series of steps that facilitate a focused in-class discussion highlighting how the paradox between the profit-maximizing demands of capitalism can be reconciled with the ethical expectations of society. In terms of expected outcomes, participants in the teaching session should gain a better understanding of the day-to-day challenges faced by business leaders as they attempt satisfy the dual demands of shareholders and customers in an increasingly competitive global marketplace. The teaching session will sensitize students to business strategies that might prompt accusations of unethical behavior. Further, the session will highlight the fact that short-term corporate gain due to unethical behavior is commonly followed by long-term financial decline and loss of reputation.

This framework can be used either prior to or after the students have been exposed to actual coursework or instruction in ethics and ethical decision making. If it is used prior to the coursework, then the students’ reactions to the case would likely be more visceral since they would not be influenced by formal instruction in ethics. If it is used after the coursework in ethics is completed, then the students should show a greater appreciation of the competing forces that frame an ethical challenge. Either way, the instructor can use the case and the ensuing debate to enhance student understanding of ethical decision making and leadership.

The specific steps in the teaching session are described below.

Questions and sample responses are as follows:

How did Corporate Governance and the Board of Directors contribute to the ethical collapse of WorldCom?

The company’s board of directors was not paying attention to how the company was managing its finances. WorldCom amassed $30 billion dollars in debt, weighing down its sagging cash flow with massive debt-service obligations. Starting in late 2000 and continuing throughout 2001, the board made a series of loans to Bernard Ebbers to induce him to not sell his WorldCom stock to meet margin calls (Harmantzis, Citation2004). The Board of directors had a habit of “rubber stamping” senior management decisions without scrutiny (Clarke, Citation2013).

(2)How did the WorldCom corporate culture factor into the management decisions that resulted in the scandal?

The Senior Management Team believed that their actions were not “really” illegal. They were simply struggling to meet financial targets. To achieve the targets, WorldCom postponed expenses by capitalizing its operating line costs. In 2000 and 2001, WorldCom claimed pre-tax revenue of $7.6 and $2.4 billion respectively, as opposed to the truth which was, later determined to be a loss of $49.9 and $14.5 billion respectively. Reserve accounts were manipulated to increase claimed revenue. The Senior Management Team also maintained two versions of accounts – the actual version and the “cooked” version for investors.

(3)How did the appetite for acquisition contribute to the ethical collapse of WorldCom?

The 1996 Telecommunications Act opened up new markets for WorldCom by allowing long-distance providers and local telephone companies to compete in other territories. The Act spurred WorldCom into a frenzy of deal making. Among the biggest acquisitions were MFS Communications (which had previously acquired UUNET, an Internet backbone company). The deal made WorldCom a major Internet player. The next merger was with MCI, the second largest telecommunications company in the U.S. after AT&T. At the time, the MCI merger was the largest in history (Harmantzis, Citation2004). The deals created mounting debt which outstripped its cash flow.

(4)How did having unrealistic and unsustainable goals contribute to the ethical collapse of WorldCom?

To attain unrealistic growth goals, WorldCom raced to make more than 70 acquisitions in two decades. The acquisitions were never consolidated into a single, seamless enterprise. Hence, the company was incapable of functioning properly. Moreover, because of accounting maneuvers, each new acquisition allowed the company to report higher per-share profits, even though its core business was barely growing, or losing ground (Eichenwald, Citation2002). The unrealistic growth target via massive acquisition introduced significant operational problem such as many small customers, multiple accounting systems, and diverse telecommunication infrastructures (Clarke, Citation2013).

(5)What was the fallout from the WorldCom scandal? Financial? Reputation?

CFO Scott Sullivan and Controller David Myers were arrested. Myers pleads guilty to three counts of conspiracy. Buford Yates Jr. pleads guilty to two counts of securities fraud and conspiracy. At his peak in early 1999, Ebbers was worth an estimated $1.4 billion and listed at number 174 on the Forbes 400. After the scandal broke, CNBC named Ebbers as the fifth-worst CEO in American history; Time Magazine named him the tenth most corrupt CEO of all time.

WorldCom stock fell from a high of $64.50 a share in mid-1999 to less than $2 a share. The price fell below $1 a share immediately and then to pennies a share upon news that there might be further accounting irregularities.

On 21 July 2002, WorldCom Filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection which was the largest such filing in the United States History at the time ($4.58 billion in liabilities). The WorldCom event was the largest corporate accounting scandal in the United States, estimated at $11 billion as of March 2004. Approximately 20,000 employees lost their jobs. Investors lost more than $180 billion (Harmantzis, Citation2004).

WorldCom employees who held the company’s stock in their retirement plans suffered losses. At the end of 2000, about 32%, or $642.3 million, of WorldCom retirement funds were in company stock which became worthless.

Sarbanes-Oxley Act was precipitated by a combination of Enron, Arthur Anderson, Tyco, Global Crossing and WorldCom which was seen as the last straw in driving through legislation.

In summary, WorldCom, with reputation in tatters, was ruined financially due to unethical behavior in the face of codes of conduct and, the then in place, industry oversight – short term gain, long term pain.

Time Requirement

The total time needed for the session as described above is somewhat flexible depending on the timing of general coursework dealing with ethics and the amount of time allotted for the team presentations and the full class discussion. Experience indicates that this teaching session will take from 60 to 90 minutes to complete but could be expanded depending on the nature of the course. Of course, this approach should be used in conjunction with a full lecture or discourse on business ethics and ethical decision making.

Optional Extension of the Session

The instructor can ask students to investigate and report on other high-profile cases of failure in corporate social responsibility and business ethics. (Students may be asked to identify cases as a homework assignment.) In the selected cases, the breach and subsequent government/societal response can be identified. Some candidate cases are as follows:

American Airlines: Deferred maintenance of aircraft.

Firestone Tire and Rubber Company: Use of child labor.

Lockheed: Bribery in Germany, Japan and the Netherlands.

HealthSouth: Misrepresented earnings.

Deutsche Bank: Spying

Halliburton: Overcharging on government contracts

Wal-Mart: Payoff scandal in Mexico

HSBC Holdings: Money laundering scheme

Appendix D:

Background on the WorldCom Scandal

From 1995 until 2000, WorldCom purchased over sixty other telecom firms. In 1997 it bought MCI for $37 billion which was the largest corporate merger in US history. In the mid-1990s, WorldCom changed from long distance discount voice carrier to an Internet and data communications carrier. It was handling 50 percent of all United States Internet traffic and 50 percent of all emails worldwide. By 2001, WorldCom owned one-third of all data cables in the United States. Its Market Value was $125 billion and its stock price was $63.50 per share. On 5 October 1999, Sprint Corp and MCI WorldCom announced a $129 billion merger agreement. It would have been the largest corporate merger in history; however, the deal was not finalized because of objections of by the US Department of Justice and the European Union (Department of Justice, Citation1998).

Beginning modestly during mid-year 1999 and continuing at an accelerated pace through May 2002, the company used fraudulent accounting methods to disguise its decreasing earnings to maintain the price of WorldCom’s stock. The fraud was accomplished primarily in two ways:

• Booking “line costs” (interconnection expenses with other telecommunication companies) as capital expenditure on the balance sheet instead of operating expenses.

• Inflating revenues with bogus accounting entries from “corporate unallocated revenue accounts” (Cooper, Citation2008).

The stock price fell from around $60 in 1999 to $1 in 2002.

Key Players in the WorldCom Scandal are described in :

Table D2. The below table presents key players and facts in the WorldCom Scandal

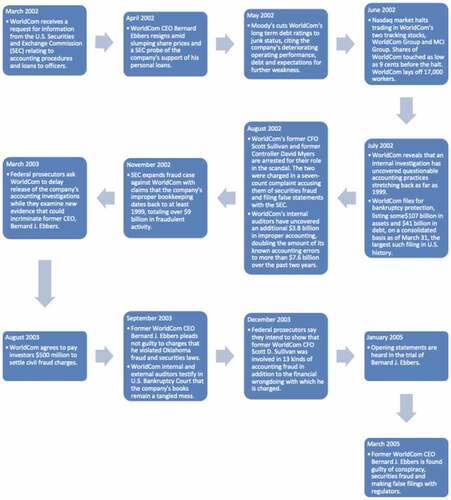

Key Dates of the WorldCom Scandal (Washington Post, 2005):

The below shows the timeline of events which occurred during the WorldCom Scandal (Washington Post, 2005).