Abstract

This study aims to analyse the diffusion level of non-financial reporting (sustainability reporting, corporate social responsibility, and integrated reporting) in companies listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange and analyse the quality of sustainable reporting standalone. Indonesia, which is one of the emerging market countries, has not yet established independent sustainable reporting regulations, but a small number of companies in Indonesia are committed to following global regulations to support sustainable development. The study was conducted on public companies listed on the Indonesian stock exchange and examined 240 sustainability reports from 2016 to 2019. For the quality of sustainable reporting standalone, we used the disclosure of triple bottom-line items (economic, environment, social) in accordance with GRI and content analysis to analyze the quality of sustainability reporting based on the GRI (Global Reporting Initiative) principles to measure quality: clarity and accuracy, timeliness, and engagement, stakeholders, comparability, and reliability. This analysis follows, whos argue that in Indonesia public companies, there do not yet require the preparation of a standalone sustainability report. This study shows that the diffusion of sustainability reports is still shallow compared to mandatory social responsibility reports. The quality of sustainability reports based on disclosure is also still low, but industry groups vary in quality. The quality of Sustainability Reporting is based on timeliness and stakeholder engagement, and comparability, satisfactory. However, for clarity and accuracy, the results are acceptable, while reliability is less acceptable.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This empirical study is being conducted to ascertain the quality of stand-alone sustainability reports on listed companies in Indonesia. Indonesia, one of the emerging economies, has not yet adopted an independent sustainability reporting rule. The lack of implementation of sustainability practices by public companies in Indonesia can be seen from the number of companies in Indonesia that operate without a commitment to environmental and social responsibility. In addition, there are still few public companies in Indonesia that disclose sustainability reports. Indonesia was not included in the survey conducted by KPMG on the 2020 sustainability report (KPMG Impact, Citation2020). It is related to this low non-financial reporting (CSR, sustainability reports, and integrated reports). A comprehensive research needs to be conducted to observe the phenomena, quality, determinants, and economic consequences to improve sustainable development in Indonesia.

1. Introduction

Sustainability is a popular topic in academic literature. The concept of sustainability is related to sustainable development, which is defined as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.“ Sustainable development can be summarised by including social and environmental aspects in business operations to satisfy various stakeholders (Van Marrewijk, Citation2003). From a business reporting point of view, this idea has led to the well-known approach of the ”Triple Bottom Line” (TBL), which considers non-financial aspects of company performance (Elkington, Citation1998).

Non-financial reporting helps promote engagement and transparency about how a company interacts with its external environment and creates long-term value for stakeholders. Non-financial reporting in this study is a social responsibility report, which is part of the annual report, a stand-alone sustainability report, and an integrated report). From an internal point of view, non-financial reporting can enhance a company’s ability to; 1) achieve long-term goals, 2) to enhance value creation (Caraiani, Citation2012), 3) to improve management information and decision making, 4) to assess risk, 5) to support benchmarking, 6) to facilitate access to financial capital, and 7) encourage dialogue within organisations (Vitolla & Raimo, Citation2018). From an external point of view, non-financial reporting increases the ability to build consensus, enhance reputation, meet the need for transparency, and develop trust around the company due to the inclusive sustainability growth logic (Chakrabarty, Citation2011; Steyn, Citation2014).

Various determinants are associated with non-financial reporting, and many theories are used to research it (based on literature studies), such as Legitimacy Theory (Brønn & Vidaver-Cohen, Citation2009) and Stakeholder theory (Roberts, Citation1992). These two theories are very widely applied in explaining the pattern and diffusion of non-financial reporting. Full attention to external factors and broad stakeholder expectations leads to the quality of non-financial reporting being neglected. In general, financial reporting research examines the determinants of non-financial statements (Geerts et al., Citation2021; Hamudiana & Achmad, Citation2017; Indyanti & Zulaikha, Citation2017; Rezaee et al., Citation2019; Rudyanto & Veronica, Citation2016; Wahid, Citation2019) and the economic consequences of non-financial statements (Aureli et al., Citation2020; Bachoo et al., Citation2013; Cooray et al., Citation2020; Farhana & Adelina, Citation2019; Halimah et al., Citation2020; Jadoon et al., Citation2021; Sutopo et al., Citation2018).

There are still few studies that focus on exploring the quality of non-financial reporting (Hahn & Kühnen, Citation2013). One of them, research conducted by (Michelon et al., Citation2015) on public companies listed on the London Stock Exchange, which examines the quality of non-financial reports in the UK. This study found that non-financial reporting practices may not provide high-quality continuous information and are only a symbolic act (Michelon et al., Citation2015). Thus the research gap of this study is that there is almost no or lack of references to scientific sources about this research that focuses on the quality of non-financial reporting in developing countries. In contrast, differences in institutional conditions between developed and developing countries are essential because they can provide results that can enrich existing scientific sources.

Furthermore, Our study examining the phenomenon of independent sustainability reports in Indonesia, which until now has not enforced mandatory regulations for the presentation of separate sustainability reports. The absence of firm regulations relating to sustainable reporting has caused only a few public companies in Indonesia to be committed to supporting massive sustainable reporting globally. This can also be seen from the absence of Indonesia in the survey conducted by KPMG regarding the 2020 sustainability report (KPMG Impact, Citation2020). The Asia Pacific countries, based on the KPMG survey, had a reporting rate of 84% in 2020. ASEAN countries were included in the survey, Malaysia (99%), Thailand (84%), Singapore (81%), but Indonesia was not included in the survey. For this reason, it is necessary to research the phenomenon of sustainable reporting and its quality in public companies in Indonesia. Research on sustainable reporting research in Indonesia generally examines the determinants that affect the quality of sustainable reports, but this research focuses on exploring the empirical phenomena of the quality of sustainability reports, both from the number of published sustainability reports and the quality of sustainability reports that have been published in Indonesia.

The existing research literature shows that non-financial reporting has been criticised for lacking relevance and credibility (Michelon et al., Citation2015; Stacchezzini et al., Citation2016). Some researchers suggest further research on the quality of non-financial reporting. Therefore, this study contributes to analysing the quality of non-financial reporting in publicly listed companies in Indonesia. The analysis was carried out with descriptive quantitative exploration. This study analyses: 1) the level of diffusion of non-financial reporting in public companies in Indonesia and 2) the quality of non-financial reporting, especially stand-alone sustainability reports. The criteria used in analysing the quality of sustainability reports is the GRI standard. Thus, the purpose of this study is to determine: 1) the level of diffusion of non-financial reporting (corporate social responsibility, sustainability reporting, and integrated reporting) on companies in Indonesia, 2) the quality of non-financial reporting, based on the area of triple-bottom-line disclosure (economics, environmental and social) on the sustainability reporting of companies in Indonesia, and 3) the quality of non-financial reporting, based on the principles of reporting quality (Clarity, Accuracy, Timeliness, Stakeholder Engagement, Comparability, and Reliability) GRI Standard on the report sustainable company in Indonesia.

2. Literature review

2.1. Non-financial reporting

The most commonly used theories to explain non-financial reporting are legitimacy theory and stakeholder theory. Legitimacy theory assumes that actions are acceptable if they respect some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions (Suchman, Citation1995). Legitimacy theory uses the overriding assumption that the maintenance of a successful organisation’s business requires managers to ensure that their organisation appears to operate according to societal expectations and is therefore associated with “legitimacy“ status. In legitimacy theory, organisations are seen as part of a broader social system and are not considered to have rights attached to resources. Instead, rights to help must be “earned“, and it is ”legitimate organisations” capable of maintaining their access (or ”rights”) to the required resources (Deegan, Citation2019).

Companies that behave differently or carry out operations contrary to society’s views will lose their legitimacy. Therefore, companies can adopt non-financial reporting to build a legitimate image. This idea of legitimacy is also reflected in the main reason for the increasing publication of non-financial reporting (Badia & Bracci, Citation2020). Another theory related to sustainable reporting is stakeholder theory. This theory assumes that the company must be managed in the interests of all its stakeholders, not only the interests of shareholders. Consequently, the company incorporates different perspectives and expectations of each stakeholder interested in the company’s activities. Non-financial reporting can be used to align stakeholder expectations, as it goes beyond the financial aspect to consider the environmental and social factors of a company’s performance. This non-financial reporting helps manage the relationship between the company and its stakeholders, who often have different and conflicting expectations (Brammer & Pavelin, Citation2004).

Non-financial reporting is a largely voluntary activity that has received significant compliance in the corporate world. This reporting is the result of the diffusion of sustainability in organisations (Jeanjean et al., Citation2010). In this case, non-financial reporting refers to sustainability reporting, social (corporate social responsibility), and integrated reporting. The concepts of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and corporate sustainability have developed clearly. Today, the terms are used interchangeably (Thijssens et al., Citation2016), although they are conceptually different (Van Marrewijk, Citation2003).

To distinguish CSR from sustainability reporting, the European Commission’s definition of CSR states, ”the responsibility of companies for their impact on society to integrate social, environmental, ethical, human rights and consumer concerns into their business operations and core strategies” (Confideration, Citation2012). Similarly, ISO 26000—the global Standard for social responsibility characterises social responsibility as ”an organisation’s responsibility for the impact of its decisions and activities on society and the environment, through transparent and ethical behaviour” (International Organization for Standardization 2010) while directly referring to maximising contributions to sustainable development as the ”overall goal for an organisation.” This characterisation provides direct links to sustainability thinking. Following the historical description of the World Commission on Environment and Development (the World Commission on Environment and Development) Development), which puts intra and intergenerational equity at the centre of thought, (Dyllick & Hockerts, Citation2002) define corporate sustainability as ”meeting the needs of a company’s direct and indirect stakeholders, without compromising its ability to meet the needs of future stakeholders as well. To achieve this goal, companies need to ”maintain their economic, social and environmental capital base” (Dyllick & Hockerts, Citation2002) which directly refers to (Elkington, Citation1998) triple-bottom-line (TBL) thinking.

The quality and reliability of non-financial reporting are still being questioned in much literature (Diouf & Boiral, Citation2017). Non-financial reporting practices may not provide a higher quality of information. Still, they can represent a symbolic act intended to show the company is truly engaged in social, environmental, and sustainability issues (Michelon et al., Citation2015). Companies present limited information about their initiatives to achieve sustainable performance, according to (Stacchezzini et al., Citation2016), and they tend not to publish information when their social and environmental commitments are scant. Several studies of non-financial financial reporting were criticised for their low relevance and credibility (Michelon et al., Citation2015; Stacchezzini et al., Citation2016), and several studies suggested the need for more intense research on the quality of non-financial reporting (Diouf & Boiral, Citation2017; Hahn & Kühnen, Citation2013).

This study combines two main theories, namely legitimacy theory and stakeholder theory, to explain non-financial reporting quality. Legitimacy theory assumes an action is acceptable if they respect some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions (Suchman, Citation1995). This theory assumes that business actions are the subject of corporate social acceptance to the broader community. Meanwhile, stakeholder theory assumes that companies must manage the interests of all stakeholders, not only the interests of shareholders (Laplume et al., Citation2008). Non-financial reporting will align stakeholder expectations because apart from the financial aspect, the company’s performance also considers environmental and social dimensions.

2.2. Quality of Non-Financial Reporting

The GRI framework is currently the most widely used reporting standard in sustainability reporting (Morhardt et al., Citation2002) and is considered the most detailed and comprehensive. Previous studies have shown that the standard GRI is the most commonly used environmental and social disclosure reporting source. Thus it is appropriate to use the GRI framework to measure the quality of non-financial reporting content (Romolini et al., Citation2015). Concerning sustainable content, GRI distinguishes four principles: namely materiality, stakeholder inclusiveness, sustainability context, and comprehensiveness. Materiality reflects that the information included in the report must describe the organisation’s economic, environmental, and social impact and be explicit in stakeholder assessments and decisions. Stakeholder inclusiveness, i.e., reports must consider and respond to stakeholder expectations and interests. The sustainability context is an organisation’s performance in the broader area of sustainability. The completeness of showing the analysed topics and the boundaries of the report should adequately describe the company’s significant involvement in social and sustainable issues and enable stakeholders to evaluate the achievement of the objectives set.

2.3. Principles of Sustainability Report Quality

The GRI (Global Reporting Initiative) framework is a reporting standard that is generally and widely used in sustainable reporting and is comprehensive and detailed (Hahn & Kühnen, Citation2013). The GRI Standards identify several principles in defining the quality of non-financial reporting: clarity, accuracy, timeliness, comparability, and reliability (Badia & Bracci, Citation2020; Farhana & Adelina, Citation2019).

Clarity indicates that information must be clear, understandable, and accessible to stakeholders. Reports must present understandable, accessible, and usable information by the organisation’s various stakeholders (in print or other channels). Stakeholders should be able to find the desired information quickly. In addition, the information must be presented in a manner that is understandable to stakeholders who have a reasonable understanding of the organisation and its activities. Graphs and tables of aggregated data can help make the information in reports accessible and understandable. The degree of incorporation of information can also affect the clarity of the report, whether or not the details of the report meet stakeholder expectations. Clarity, containing information at the level required by stakeholders, but avoiding excessive and unnecessary detail, stakeholders can easily find the information they want through a table of contents, maps, links, or other help.

Accuracy indicates that information must be accurate and detailed enough for stakeholders to evaluate the company’s performance. Responses to DMAs and economic, environmental, and social indicators can be conveyed in various ways, ranging from qualitative responses to detailed quantitative measurements. The characteristics that determine accuracy vary according to the nature of the information and the users. For example, the accuracy of qualitative information is primarily determined by the level of clarity, detail, and balance of presentation within the appropriate Aspect Boundary. The accuracy of quantitative information, on the other hand, depends on the particular method used to collect, compile and analyse the data. The accuracy of information is one of the main issues in sustainability reporting. According to GRI 2006, “the information reported must be sufficiently accurate and detailed for stakeholders to assess the performance of the reporting organisation“ (Global Reporting Initiative, Citation2016). The fundamental characteristic that determines the accuracy of a report is the nature of the information and its usefulness to stakeholders. Factual accuracy refers to the accuracy and margin of error. To consider these requirements, organisations must adequately describe their data measurement techniques, the basis for calculating and demonstrating that they can replicate them with similar results. In addition, the margin of error should not be so significant as to jeopardise the ability of readers or reviewers to make appropriate conclusions about the company’s sustainability performance. Finally, GRI 2006 that state organisations must ensure that ”qualitative statements in reports are valid based on other reported information and other available evidence” (Diouf & Boiral, Citation2017; Global Reporting Initiative, Citation2016).

Timeliness means that reporting must be processed regularly and made available on time for stakeholders to explain and share decisions. Therefore, in our analysis, we refer to “timeliness and stakeholder engagement” to emphasise the role of stakeholders. The usefulness of information is closely related to when the information is presented to stakeholders to integrate it effectively in decision making. Time of issue refers to the regularity of reporting and its proximity to the actual events described in the report. Although a constant flow of information is expected to meet specific objectives, organisations must commit to regularly providing consolidated disclosures about their economic, environmental and social performance at any given point in time.

Comparability, indicating that the information presented should enable stakeholders to see a picture of performance concerning the goals and results achieved in previous years over time, which supports comparisons with other organisations. Comparability is one of the principles of sustainability reporting by which organisations must select, collect and report information consistently. Reported information should be presented to allow stakeholders to analyse changes in the organisation’s performance over time, which can support the analysis relative to other organisations.

Comparability is an important criterion that allows users to evaluate organisational performance (Langer, Citation2006). However, difficulties in comparing sustainability reports can sometimes explain the reluctance of stakeholders—in this case, investors—to use disclosed information regarding a company’s sustainability performance (Friedman & Miles, Citation2001). GRI 2006 state that to overcome such difficulties, ”reported information” must be presented in a way that allows stakeholders to analyse changes in organisational performance over time, and can support analysis relative to other organisations” (Global Reporting Initiative, Citation2016).

In the context of SRI, a comparative analysis is essential for evaluating firms’ progress and comparing their performance to related activities: for example, ratings in making investment decisions (Dragomir, Citation2012; Langer, Citation2006; Peck & Sinding, Citation2003). To do this, users of GRI reports must compare the information disclosed about a company’s social, environmental, and economic performance with information about the past performance of the same company. They should also be able to compare their performance with other companies. Therefore, quality reports should allow measurement of the organisation’s performance over time and compare its performance with the performance of other organisations in the same sector.

Reliability relates to how information and processes used to prepare reports are collected, recorded, compiled, analysed, and disclosed so that they can check them and the quality and materiality of information can be determined (Global Reporting Initiative, Citation2016). Stakeholders must have confidence that the report can be tested to establish the correctness of its contents and the extent to which the Reporting Principles have been appropriately applied. The information and data entered into the report must be supported by internal controls or documentation that can be reviewed by someone other than the person preparing the report. Disclosures about performance that are not supported by evidence should not be included in a sustainability report unless they represent material information. The report provides a clear explanation of any uncertainties associated with that information. In designing an information system, the organisation should anticipate examining the system as part of the external assurance process. In the report, the scope and scope of external assurance are identified, the organisation can locate the source of information in the report. In addition, reliable evidence to support complex assumptions or calculations can be identified by the organisation.

3. Research methods

3.1. Research Design and Data

This type of research is exploratory research with quantitative analysis to analyse the diffusion level of non-financial reporting (corporate social responsibility sustainability reporting, integrated reporting) and the quality of sustainable reporting (sustainability reporting) on companies listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange in 2016–2019. Sources of data come from secondary data, Annual Reports, and sustainability reports published on the websites of each company and the website of the National Center of Sustainability Reporting (www.ncsr-id.org).

In analysing the diffusion rate of non-financial reports using a total sampling with a population of 713 companies (the number of companies listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange as of October 2020). For analysis of the quality of sustainable reports by purposive sampling, namely companies that present sustainability reports from 2016 to 2019, so that the following samples can be obtained:

The above shows the development of companies that have published sustainability reports from 42 companies in 2016 to 83 companies that have published reports in 2019. So to conduct a content analysis on the quality of sustainable reporting carried out on 240 sustainability reports.

Table 1. Sample

3.2. Analysis Technique

This study uses an exploratory approach to analyse the content of non-financial reporting. The non-financial reports analysed are annual reports to see compliance with corporate social responsibility reporting, sustainability reporting, and integrated reporting.

Quality analysis was carried out using content analysis techniques with exploratory methods.

The stages of analysis are as follows:

Company website analysis, completed for collection of non-financial reporting documents (from April-May 2021);

The first data analysis, related to the use of non-financial reporting statistics (May-June 2021);

Research participants carry out research dissemination activities related to the first results; discussion on the development of quality factor analysis (June 2021);

Elaboration of the quality indicator measurement framework (clarity, accuracy, timeliness, comparability, and reliability) that will use for the analysis of the documents collected (June-July 2021);

Conduct content analysis on documents (non-financial reports) collected and the first scoring by each document, using a quality indicator measurement framework (July-August 2021);

Scoring analysis that has been carried out by researchers, comparison and analysis of differences and distribution of specific final scores for each company (August 2021);

Elaboration and group validation of final statistics, charts and tables (from September 2021).

Prepare research reports (September-November 2021)

3.3. Quality Factor Measurement Framework

In measuring the quality of sustainability reporting, it is based on the principles of sustainable reporting, as stipulated in GRI 101 (Badia & Bracci, Citation2020). The shows the framework of Quality Factors Measurement.

Table 2. A framework of Quality Factors Measurement

4. Empirical results

4.1. The Level of Diffusion of Non-Financial Statements

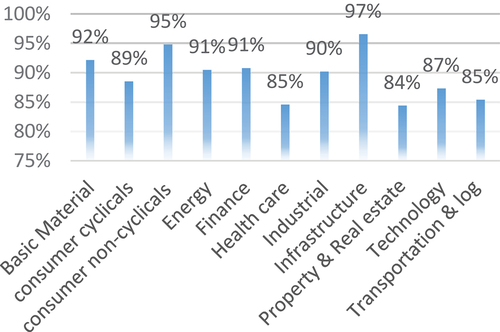

The Annual Report is the non-financial report required by OJK, and Corporate Social Responsibility is one of the chapters of the Annual Report. The Annual Report, one of which is related to corporate social responsibility, is a report that must be prepared and reported by public companies listed on the Indonesian stock exchange. For this reason, this report should have been 100% reported by the company. But, based on a search on the respective company’s website, there are still companies that have not uploaded it to their website. shows that, on average, 90.7 per cent of corporations have documented their CSR efforts on the website in the form of an Annual Report over the last five years, with this number increasing from 2015 to 2019.

When viewed from the compliance of each industry in reporting its CSR activities (in the Annual report), there are three industry groups that, on average, are quite high in publishing CSR reports on their website, namely the Infrastructure sector, non-primary consumer goods, and materials sector. In addition, the industries with an average publication level are still low, namely property and real estate and the health sector.

The following non-financial report needed is the sustainability report (SR), which presents the concept of the company’s contribution to sustainable development. The sustainability reporting report explains how the company prioritises short-term performance and long-term performance in balancing profit, people and planet (triple bottom line) for the company’s long-term performance. Sustainability reporting is a type of non-financial report that is still voluntary in Indonesia.

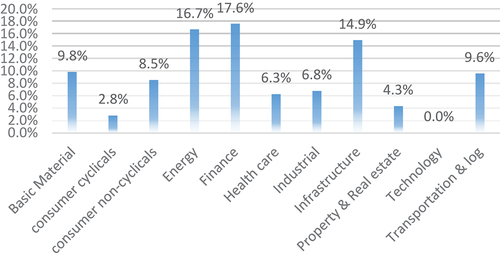

shows that, on average, only 9.8% of public companies have compiled a separate sustainability report in its development. In 2019, 13.1% of listed companies had collected and reported their sustainable performance. When compared between industry groups, the financial industry group is the industry group with the highest level of submission of sustainability reporting, 17.6%. This is due to OJK legislation in POJK no. 51/ POJK.03/2017 requiring financial service institutions, issuers, and public businesses to conduct sustainable finance. Furthermore, organisations in the energy and infrastructure sectors are a relatively high industry category in terms of reporting sustainable performance, averaging 16.7% and 14.9%, respectively.

Issues of sustainability and transparency have developed the nature of corporate reporting. On these issues, stakeholders are very interested in gaining access to financial and non-financial information about the company’s business activities and sustainable value creation. However, despite the availability of information, many stakeholders cannot correctly use the information disclosed due to separate reports. Thus, “Integrated Reporting“ brings together financial and non-financial measures in one report section. This report presents the relationship between economic and non-financial performance metrics. Integrated reporting is a holistic reporting approach for companies and addresses the potential of single pieces (Hoque & Chia, Citation2012). The core concept underlying ”integrated reporting” is to provide a single report that fully integrates a company’s financial and non-financial information (including environmental, social, governance and intangible). However, integrated reporting is more than simply combining financial and sustainability reports into one document (Krzus, Citation2011).

Over the past decade, several companies have begun to consider the idea of convergence between financial reporting and sustainability and have integrated social and environmental information into their annual reports (see, for example, companies participating in the IIRC pilot program and the list of companies on the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) homepage. who named their report “integrated”). Furthermore, some academics (Elkington, Citation1998) as well as institutions (such as the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC), GRI and King Committee) increasingly expressed the need for integration of financial and non-financial information. Into corporate processes, decisions and reporting, to take into account critical performance indicators (KPIs) and strategic factors driving firm value (this could be the reason why these institutions engage with IIRC; John, Citation1998).

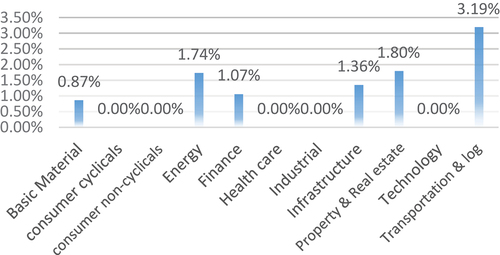

The shows that integrated reporting has not spread enough to companies listed on the IDX, which is only an average of 0.8%. In 2019, only seven companies submitted integrated reporting. When we looked at each subsector individually, transportation and logistics companies had the most significant percentage of integrated report presentation (3.19%), followed by the property and real estate and energy subsectors (1.8%) and 1.74%), respectively. This fact demonstrates that the company’s willingness to compile integrated reporting in Indonesia is still minimal.

4.2. Quality of Sustainability Reporting

This study combines different dimensions to measure the quality of CSR disclosure: 1) the content (content) of information disclosed (what and how much is disclosed) per triple-bottom-line dimension, and 2) the quality of SR disclosure based on the principles of sustainable reporting, namely clarity and accuracy, timeliness and stakeholder engagement, comparability and reliability.

4.2.1. Economic Performance

Investor confidence in the capital market is the primary driver of economic growth, prosperity and financial stability. Information on the creation and distribution of economic value provides a preliminary indication of how an organisation has created wealth for its stakeholders. Several components of generated and distributed economic value (EVG&D) also give an organisation’s economic profile, which can help normalise other performance figures.

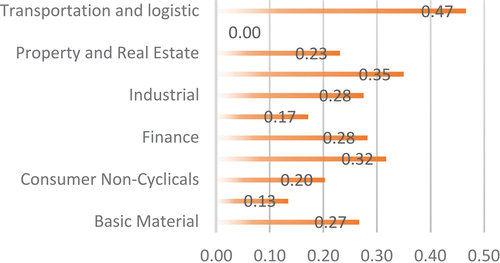

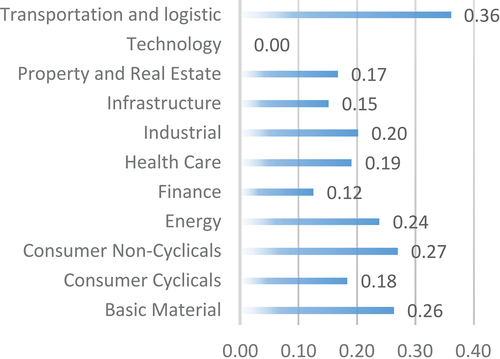

Based on the , of the 85 companies observed over the last four years presenting sustainability reports, the activity disclosure index on the economic dimension shows an average per industry of 0.25. The contribution of the highest economic index in the sustainability report is in the Transportation and logistics group, but in that group, only one company has compiled a sustainability report. The largest industry group that compiles sustainability reports is the Finance sector, with 20 companies. As for the Technology group, there is not a single company that has compiled a sustainability report .

Table 3. Index of Disclosure of Economic Dimensions per Industry, 2016–2019

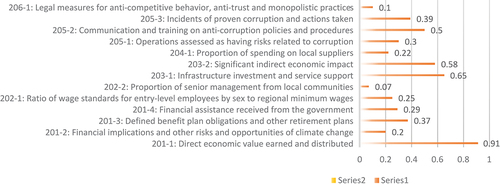

Sustainable disclosure regulates six groups of disclosures on economic performance, namely Economic Performance, Market Existence, Indirect Economic Impact, Procurement Practices, Anti-Corruption and Anti-Competitive Behavior. shows the Economic Dimension Criteria-Based Disclosure Index.

If observed following the disclosure indicators of economic aspects, using GRI standards, the highest disclosure is on aspects of economic performance (see ), especially on the direct economic value items obtained and distributed, 91% of the sustainability report. In addition to these aspects, other items that are quite high disclosed are Infrastructure investment and service support, the item Significant indirect economic impact, and the item Communication and training on anti-corruption policies and procedures.

Furthermore, it should note that several disclosure items must be explained in sustainable reporting, which is still minimal, with the lowest proportion of senior management coming from local communities, this item has only been disclosed in 14 sustainability reports, or 7% of the total number of sustainability reports observed. Including local community members in the organisation’s senior management demonstrates the organisation’s positive market presence. Involving local community members in the management team can improve human resources. It can also increase the economic benefits for local communities and grow the organisation’s ability to understand local needs.

4.2.2. Environmental Performance

The organisation shall establish an environmental policy framework to address environmental concerns and promote policy measures. This means that enterprises must produce value for stakeholders by effectively and efficiently utilising scarce resources, hence reducing negative environmental impacts. Conserving environmental quality through time and having a better environment for future generations is characterised as ecological sustainability.

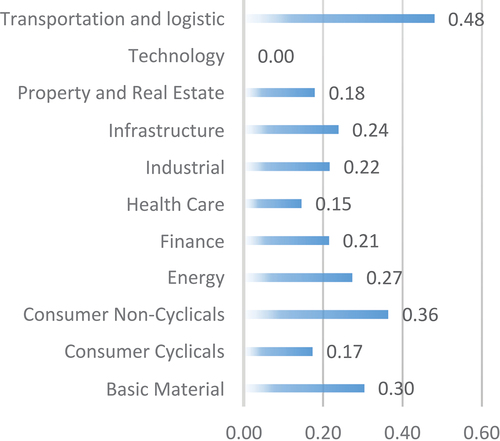

shows that, there is the highest index of disclosure for the second triple bottom-line item, namely the environmental element, which has increased considerably over the last four years, particularly the final in 2019 with an index of 0.31 from an index of 0.12 in 2016. Acording to . transportation and logistics (but only one firm) have the highest average transparency, followed by a category of consumer non-cyclicals with an environmental disclosure score of 0.27. Finance is one of the lowest environmental dimensions, revealing only the social component in the study with an average of 0.12. The Technology group has not yet compiled a sustainability report.

Table 4. Index of Disclosure of Environment Dimensions per Industry, 2016–2019

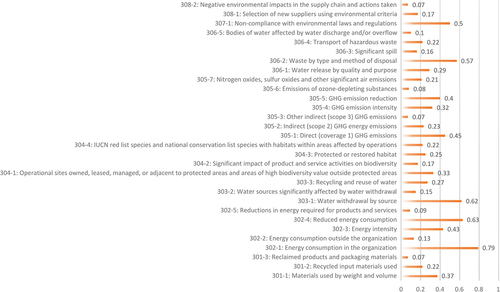

shows that, disclosure of “Energy consumption in the organisation” is the highest disclosed item with an index of 0.79. In addition, the aspect of reducing energy consumption is also a disclosure item that is widely publicised, with an index of 0.63. An organisation can consume energy in many forms, such as fuel, electricity, heating, cooling or steam. Energy can be self-generated or purchased from external sources and can come from renewable sources (such as wind, water, or solar) or non-renewable sources (such as coal, petroleum, or natural gas).

Using energy more efficiently and choosing renewable energy sources is critical to combating climate change and lowering an organisation’s overall environmental footprint. The disclosures in this Standard can provide information about an organisation’s energy-related impacts and how the organisation manages them. However, several items are presented with a minimum standard, accounting for only 7% of all observed sustainability reports, such as reclaimed products and their packaging materials, other indirect (coverage 3) GHG emissions, and Negative environmental impacts in the supply chain, as well as actions already taken. These aspects are generally related to suppliers’ material aspects, emission aspects, and environmental evaluation aspects.

However, of the 30 items that must be disclosed on environmental aspects, only five elements have an average disclosure of 50% of the observed sustainability reports. The rest (25 items) are disclosed below 50% of the empirical sustainability reports from 2016–2019. As a result, the average environmental disclosure is 0.29 per cent of all observed sustainability reports. The average index of the disclosure of environmental elements (0.29) is relatively lower than the economic aspect, which is 0.39 (39%).

Regarding the low disclosure of environmental aspects, it can be seen from various assumptions, including, firstly, this can occur because there is no or unavailability of an information system at the company to manage information or manage environmental sustainability, or secondly, it could be that the information does not intersect with the environment. The company’s business activities so that nothing will be disclosed or because, thirdly, the company’s lack of commitment in protecting environmental aspects to combat climate change and to reduce the organisation’s overall ecological footprint. For this reason, further exploration is needed to find out the determining factors, the extent of disclosure in the sustainability report.

4.2.3. Social Performance

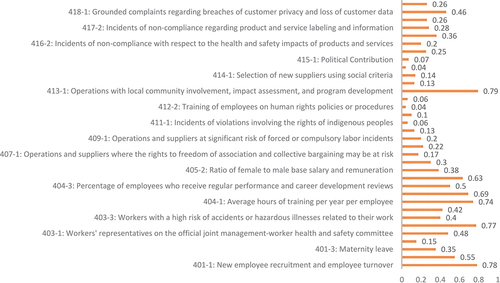

Acording to , the average social standard disclosure index is 0.24 or 24% disclosed. This index had increased from 0.16 in 2016 to 0.32 in 2019. This increase indicates an increase in the number of disclosure items in the last four years. Also, The average disclosure index of social dimension per industry shows in .

Table 5. Index of Disclosure of Social Dimensions per Industry, 2016–2019

Components of Supplier Social Assessment, particularly negative social implications in the supply chain and actions taken, and aspects of sustainability reports that are rarely highlighted. This feature was only detected in eight sustainability reports, or 4% of the total number of sustainability reports examined. The disclosures in this Standard can reveal a company’s strategy for preventing and managing negative social consequences in its supply chain. Suppliers may be assessed for a variety of social criteria, including human rights (such as child labour and forced or compulsory labour); employment practices; health and safety practices; Industrial relations; incidents (such as harassment, coercion or harassment); wages and compensation; and working hours. This disclosure informs stakeholders of the organisation’s awareness of significant actual and potential negative social impacts in the supply chain.

However, the disclosures presented do not explicitly explain the negative social impacts in the supply chain and the actions that have been taken that have occurred to the company. It could be that the company has not yet discovered the negative social impact of the supply chain or its actions or that the company does not yet have a motive to disclose this so that the reason this could happen requires further research. When viewed from the average disclosure of social standards, it is 0.24 or 24% of the observed sustainability reports reporting social standards, which is higher than environmental disclosure with an average of 20% and slightly lower than the disclosure of economic standards, which is 25%.

4.3. Quality of Sustainability Report based on Quality Principles

shows disclosure index according to social dimension criteria. To prepare sustainability reports following the GRI Standards, organisations apply the Reporting Principles to determine GRI 101: Foundations report content to identify their material economic, environmental, and social topics. These material topics determine which topic-specific Standards an organisation uses to prepare its sustainability report (Global Reporting Initiative, Citation2016). Indeed, the essence of preparing a sustainability report is to focus on the process of identifying material aspects. According to the principle of materiality, material aspects are those that reflect the significant economic, environmental and social impacts of the organisation or substantively influence stakeholder judgments and decisions. Sustainability report prepared by the company. One benefit of using concepts such as materiality in the context of financial, social and environmental issues is that it helps emphasise a business-centred view and narrow broad social and environmental information into items that help inform investors and other stakeholders about a business’ ability to create and sustain value.

Clarity indicates that information must be clear, understandable, and accessible to stakeholders. Accuracy indicates that information must be accurate and detailed enough for stakeholders to evaluate the company’s performance. “Clarity“ and ”accuracy” refer to the type of information that should be provided to stakeholders. This study combined two dimensions in one measure (Badia & Bracci, Citation2020) and was developed using a Likert-5 scale. According to the principle of clarity, the information disclosed in a sustainability report must be presented in a manner that is understandable, accessible and usable by all stakeholders. The clarity of the sustainability report should allow readers and users to find and understand specific information without much effort (Global Reporting Initiative, Citation2016). For this to happen, sustainability reports must contain the level of information required by stakeholders by avoiding excessive and unnecessary detail, technical terms, jargon and acronyms, and other content that has the potential to limit understanding (Global Reporting Initiative, Citation2016). To this end, GRI recommends the use of indexes, maps, links, tables, graphs, and other potentially helpful content.

From the overall research process on 83 reports that were observed for the 2019 sustainability report, 61 reports for 2018, 54 reports for 2017 and 42 reports for 2016, it is seen that the average index quality of reports has increased from the Clarity and Accuracy aspects, from year to year. The sustainability report quality index in 2019, which is 2.88, is always an increase from 2016, with an index of 2.36. Quality of clarity and accuracy at level 5 in the 2019 sustainability report, accounting for 18.1 per cent (15 sustainability reports) of the total sustainability report. This number increased significantly from the previous year’s report, with quality at this level of only 8.2% (5 reports). The quality criteria for Clarity and Accuracy at level 5, the information is very clear and accurate: includes all data that is considered important for external communication, uses a well-structured and easy-to-read presentation framework for each category of stakeholders; all of this information is developed in a context that respects and is consistent with the triple bottom line approach.

However, the highest quality of reports from the Clarity and Accuracy aspects for the 2019 sustainability report was level 2, which was 22.9% (19 sustainability reports). Although the highest percentage was at level 2 in 2019, on average from the previous year, this level decreased, from 35% in 2016, 25.9% in 2017 and 24.6% in 2018. This shows that there is an increase in the quality of continuous reports. From the aspect of clarity and accuracy, because the proportion of level 5 has increased. Clarity and accuracy at level 2 are based on criteria. The information is partly clear and accurate: some quantitative data appear, and the presentation is not very accurate; however, the triple bottom line approach has been described satisfactorily. In general, many reports present their achievements, but some of them do not clearly present quantitative data in the sense that they do not present the basis for measuring data. For more details can be seen in the Table .

The second principle of report quality is timeliness, which is how the company provides sustainability information at the right time to stakeholders. Consistency in reporting frequency and length of the reporting period is also needed to ensure comparability of information over time and accessibility of reports to stakeholders. If the timetables for sustainability and financial reporting are matched, this can be beneficial to stakeholders. Organisations must balance the need to provide information promptly to ensure that the information is reliable. The timeliness of reporting aligns with stakeholder involvement in the company’s sustainability process during the operating period.

The company will report how it interacts with various stakeholders at the local, regional, national and global levels. External stakeholders at the local level play an important role in granting social licenses, involvement in business operations, and management. Stakeholders include employees, suppliers and customers, shareholders, governments and regulators, local communities, community-based organisations, non-governmental organisations, business partners, colleagues and industry associations, and the media. Internally, the stakeholder list is mapped, then reviewed and updated by ongoing communication with all stakeholders identified.

Based on Table above shows that the stakeholder engagement index had increased from year to year from 2.83 in 2016 to 3.37 in 2019. This indicates that stakeholder engagement is addressed, focusing on communication initiatives and those related to the document drafting process., however, there are still many who have not shown references to the involvement of stakeholders in the outcome measurement process. In general, the quality of stakeholder involvement is at a satisfactory level.

Table 6. Quality Clarity and Accuracy in Sustainability Reporting

Comparability or comparability is one of the principles of sustainability reporting in which organisations must select, collect and report information consistently. Reported information should be presented to allow stakeholders to analyse changes in the organisation’s performance over time, supporting the analysis relative to other organisations. Comparability is needed to evaluate performance. Stakeholders using the report should be able to compare the reported information on economic, environmental and social performance against the organisation’s past performance, against the organisation’s objectives, and, to the extent possible, against the performance of other organisations.

We observe the level of report comparability, which is then quantified to classify the comparability quality. If there is no comparative reference between the results obtained in the past and previous years, we will give a score of one (1). If there is a comparison of data and results, without an explicit reference to the relationship of these results to the stated objectives previously, it will be scored. Two (2), and if there is a comparison of data and results, it is also related to the objectives stated previously. Based on the latest developments, namely in 2019, 83.2% (44.6% and 38.6%) have presented comparatively sustainable data (triple bottom line). The remaining 17.8% is a sustainability report that is still very concise, offered only as a description of the company’s sustainable activities. However, the quantitative performance table is still minimal.

shows the average of comparability quality in 2019 was 2.22 (or equivalent to 3.70), which shows the comparability quality is higher than the clarity and accuracy quality (2.88), and timeliness and stakeholder engagement (3.37). Comparability of sustainability reports so far has only been at the inter-period level at the same company. Due to the significant variability in how data is presented, it is still unclear that comparisons between organisations can be made. As it is known that sustainability reports are still voluntary, even though the presentation guidelines have been regulated in the GRI standard, in its realisation, each company has various creativity and innovations in preparing sustainability reports.

Table 7. Quality of Timeliness and Stakeholder Engagement in Sustainability Reporting

The reporting organisation shall collect, record, compile, analyse and report on the information and processes used in the preparation of the report so that it can be examined and which establishes the quality and materiality of the information. Stakeholders need to ensure that the message can be examined to establish the correctness of its content and the extent to which the Reporting Principles have been applied. To test the reliability of the sustainability report, identified the scope and level of external assurance (Al-Shaer & Zaman, Citation2016; Global Reporting Initiative, Citation2016).

The lack of external assurance on the presented sustainability report was used to assess reliability in this study. It is divided into five categories, with a score of 1 for companies that do not publish a sustainability report, a score of 2 for companies that publish sustainability reports and have a sustainability committee affiliated with the board of directors, a score of 3 for companies that publish sustainability reports and have a sustainability committee affiliated with the board of directors, a score of 4 for companies that present a sustainability report and assurance is provided by a non-audit company, and a score of 5 for companies that present a sustainability report.

Based on the analysis conducted on companies registered in Indonesia, the following Table presents the quality of the reliability (reliability) of the report.

Table 8. Comparability Quality in Sustainability Reporting

Based on the table above, it can be seen that the level of reliability (reliability) of sustainable reports is at an index of 2.54 in 2019. This quality is lower than other report quality criteria (clarity and accuracy (2.88), and timeliness and stakeholder engagement, (3.37) and comparability (3.7). On average, 65.8% of report reliability is at the level of having prepared a sustainability report, 15.70% of companies already have a sustainability commission in their organisational structure (this indicates that the company is committed to compiling reports with a high level of reliability) and 18.50% of sustainability reporting has received external assurance from a non-audit company. Companies are expected to disclose their external assurance policies and practices, including explaining how external assurance is provided, the scope and results of assurance services and the relationship between the organisation and its assurance providers (Prinsloo & Maroun, Citation2021) .

(Prinsloo & Maroun, Citation2021) found that in most cases, companies included a firm statement of their directors’ responsibilities concerning integrated and sustainability reporting and a clear indication that the report was subject to, at least, some form of assurance. (Prinsloo & Maroun, Citation2021) show that external guarantees combined with internal guarantees are essential to determine the level of reliability of sustainability reports. There are still few sustainability reports on public companies in Indonesia, namely 18.50%, which adds external guarantees to their non-financial reports. (Hassan et al., Citation2020) stated that organisations based in weaker legal environments are more likely to obtain assurances because this adds to the credibility and reliability of sustainability reports.

5. Discussion

This research contributes to sustainable reporting research in Indonesia to analyse the quality of this non-financial reporting. This study investigates the level of diffusion (spread) of non-financial reports in Indonesia. It explores the quality of disclosure in sustainability reports to explain the involvement of companies in sustainable development. This study examines the level of diffusion of non-financial reports in Indonesia in the last five years, which shows a relatively high level of diffusion in presenting corporate social responsibility reports on each company’s website. The presentation of social responsibility information on public companies in Indonesia is shown in the annual report as stipulated in PJOK No. 29/PJOK.04/2016 concerning the Annual Report of Issuers or Public Companies. In article 4, point h., the company must present the social and environmental responsibility of the Issuer or public company no later than the end of the fourth month after the end of the financial year.

In general, companies use annual reports to convey corporate social and environmental information, in addition to financial information. Because of this mandatory nature, in general, companies must present an annual report. Sustainability reporting is a report that demonstrates how the business run by the company considers the balance of the triple bottom line (economic, social and environmental) in a stay alone reporting format. The practice of voluntary sustainability reporting has evolved over the last decade (Adaui, Citation2020). Likewise, the results of the KMPG survey in 2020 showed an increase in continuous reporting (KPMG Impact, Citation2020). However, the 2020 KMPG survey did not include Indonesia as a sample. For this reason, it is necessary to analyse the rate of diffusion/spread of SR stand-alone reporting.

The level of diffusion of sustainable reports has increased in the last five years (2015–2019), from 7.2% of public companies in 2015 to 13.1% of public companies in 2019. Although it has increased, this number is still minimal, or the diffusion of sustainable reports is still deficient. The highest level of diffusion occurs in the energy, finance and infrastructure sub-sectors. Energy, finance, and infrastructure companies are closely related to the environment and social, so preparing a stand-alone sustainable report is a means to indicate that they have carried out operations following social systems, norms, values, beliefs, and definitions that are built socially (Suchman, Citation1995) and shows its legitimacy, however, this amount is still very tiny from all current public companies. However, a sector that has developed quite a bit in the last decade, namely the technology sector, has not presented a sustainable report during the previous five years. The integrated report for the following non-financial report has a shallow diffusion rate of 0.8% on average over the last five years. The low motivation of public companies to present non-financial reports other than CSR shows their intense concern for considering all stakeholders in its business. The absence of an obligation (still voluntary) to compile a sustainability report is one of the causes of the low rate of diffusion. Regulations made by the government to invest in companies that report on sustainable development will be able to encourage sustainable reporting (Adaui, Citation2020; Mion & Adaui, Citation2019).

Analysis of the quality of the report is carried out based on the GRI (Global Reporting Initiative) Standard. The content analysis of sustainable information is focused on the triple-bottom-line, namely the economic, environmental and social dimensions. In the disclosure of the economic dimension, the average is still at the index of 0.33 or 33% of the total items that must be disclosed in 2019. The highest disclosure item is the direct economic value obtained and distributed. 91% of the sustainability reports present this item. Although this aspect is reported maximally by publicly listed companies, most of the others are presented with a lower level of presentation, below 50%. Items that need to be observed are the inadequate disclosure of the company’s economic impact on local communities, which is minimal. The environmental dimension, presented with a lower index than the economic dimension, was 0.31 (or 31%) in 2019, and this index increased quite significantly from the previous year, which was 0.21. The aspect of energy consumption in the organisation is the aspect that is most often disclosed in the sustainability report. 79% of the reports present this aspect. However, information on emissions, wastewater and waste is an aspect that is still minimally disclosed on average.

The social dimension in the average index range of 0.32 in 2019 increased from the previous year. Social activities involving local communities are relatively high aspects presented in the sustainability report. Followed by the process of recruiting and changing employees, the accident rate, training and skills carried out on employees are aspects that are often revealed from year to year and do not vary. This demonstrates that the company’s commitment to meeting all social sustainability standards is still inadequate. Tend to be comfortable with programs that are relatively repeated from year to year. This fact contradicts (Petrescu et al., Citation2020), which states that the company’s mission and goals must be sustainable by including social and environmental targets in the sustainability strategy and the views of specific groups such as Customers/Consumers, Employees, Local Communities, Directors, Regulators and Sustainability Organizations. Press and Media, Public, Investors and NGOs must become increasingly important for companies that wish to remain competitive in the future market.

Based on the analysis of the content of the sustainability report, in general, there is no significant increase in the amount disclosed from year to year. Furthermore, based on the items revealed, companies tend to present a report format that is repeated from year to year, without any variation in increasing the content and items presented. The results of this study are in line with (Astuti & Putri, Citation2019), which states that there is no difference in the quality of economic, environmental and social disclosure in construction services, and with low quality, where companies rely heavily on a compliance approach in implementing sustainability, and only symbolic (Michelon et al., Citation2015). The company appears to be providing more information, but this information is diluted with other irrelevant pieces of information. This dilution of relevant information can be construed as a way to hide the triple-bottom-line information, simply portraying the corporation as a committed part and obscuring essential disclosure items. These results are relevant to (Michelon et al., Citation2015). In general, the number of companies that issue stand-alone sustainability reports does not yet support the legitimacy argument, although the content of the triple bottom line demonstrates that companies are merely at the limit of formality. This indicates that sustainable reporting practices may not provide high-quality sustainable information and may be merely symbolic (Michelon et al., Citation2015).

This raises the question of whether the company’s commitment to contribute to sustainable development is integrated into the company’s vision and mission, which needs to be investigated further (Gallego-Álvarez et al., Citation2010). At the same time, the presentation of multidimensional information involving social, environmental and economic information will improve the company’s sustainable performance. This is in line with the increasing need for stakeholders to provide more extensive knowledge to improve sustainable performance (Caraiani, Citation2012).

In addition to the limited number of companies compiling sustainability reports, they are still struggling to meet the expectations in terms of the content and quality of application of the sustainability reporting standards. Based on the items presented, there are still items that have not seen a significant revolution to ensure that the operations being carried out already integrate social and environmental considerations, as well as their duties to stakeholders. For example, an explanation of “Operations with significant actual and potential negative impacts on local communities,” disclosures related to such topics have only been made by 13% of observations. Although operational actions have no negative consequences, they must be disclosed as they are as a form of accountability to stakeholders. These finding give the implication that the regulators or governing authorities must urge businesses to incorporate economic, social, and environmental issues into their operations, and then encourage businesses to report these non-financial instruments to their stakeholders.

According to the quality principle, the quality of the sustainability report shows mixed results, which are concluded in the Table On timeliness and stakeholder engagement, and comparability, it is satisfactory. As for clarity and accuracy, it is lower than acceptable, while reliability shows less acceptable quality.

Table 9. Reliability Quality in the Sustainability Report

Concerning timeliness and stakeholder engagement, it shows that the company explains the process of involving stakeholders in the business processes that the company runs. The sustainability report shows the company presents stakeholder involvement quite clearly and thoroughly. However, the participation of stakeholders in the measurement of results is still minimal. Comparability shows how the company can compare better or worse than the previous period. It is also crucial for stakeholders to obtain information on achieving sustainability goals, but in the description, this is still limited. These results support (Badia & Bracci, Citation2020), although timeliness, stakeholder engagement, and comparability show satisfactory quality, it is still not sufficient. The triple-bottom-line information disclosed in most sustainability reports is still on a low index.

shows the Synthesis of Results Obtained. The clarity and accuracy of the sustainability report show that it is acceptable; this indicates that the report, in general, has presented a reasonably clear portion and the triple-bottom-line approach is clear and explicit. This shows the company’s commitment to sustainability policy. However, the quality of reliability shows concerning results because the lack of reliability, as measured by external assurance, can affect the credibility and perceived quality of the sustainability reports provided (Badia & Bracci, Citation2020; (Stacchezzini et al., Citation2016). Thus, non-financial reporting can be used primarily to enhance an organisation’s reputation and legitimacy, not as a means to assess ongoing performance and to communicate with stakeholders (Stacchezzini et al., Citation2016).

Table 10. Synthesis of Results Obtained (The year 2019)

6. Conclusions and suggestions

This exploratory research related to the quality of non-financial reporting shows that the diffusion of stand-alone sustainability reports and integrated reports is still low. This is because there is no mandatory regulation for these two types of reports. Further research on the quality of sustainability reports shows that the disclosure of economic, environmental and social dimensions (triple-bottom-line) based on the standard GRI criteria is still low. The phenomenon of sustainable reporting in Indonesia which is still voluntary does not support the legitimacy theory which states that successful organizational business management requires managers to ensure that their organizations appear to operate in accordance with community expectations and are therefore associated with “legitimized” status. This means that the company does not use sustainability reports to build its image.

When compared to quality based on industry, the quality of the non-cyclical consumer group is relatively higher than other industry groups. However, economic disclosure is somewhat higher than the two dimensions, and the environmental dimension is the lowest. From the economic dimension, the item with the most increased disclosure is the economic distribution shared. Then from the ecological dimension, the highest disclosure of internal energy sources is consumed, and from the social dimension, the most increased disclosure is operations involving local communities. Also, reports between companies tend to vary between periods in the same company to show the same presentation and not show variations in the implementation of sustainable business operations. This study also found that applying the GRI guidelines in sustainability reports was fragmentary, and the reports varied (Gamage & Sciulli, Citation2016).

Report quality based on timeliness and stakeholder engagement, and comparatively, satisfactory. However, the results are acceptable for clarity and accuracy, while reliability shows the quality is not acceptable. Satisfactory qualifications on stakeholder engagement support the stakeholder theory, where this theory assumes that the company must be managed for the benefit of all its stakeholders, not only the interests of shareholders. Non-financial reporting can be used to align stakeholder expectations, as it goes beyond the financial aspect to consider environmental and social factors of the company’s performance. This non-financial reporting helps manage the relationship between a company and its stakeholders, who often have different and conflicting expectations (Brammer & Pavelin, Citation2004). However, with regard to the reliability indicator of the sustainability report at the level of no acceptable, it shows the low level of report reliability, this can be seen from the existence of external guarantees in the sustainability report. No competent third party is involved in ensuring the quality of the report, relevant to conclusions related to clarity and accuracy analysis which are only at the acceptable level. This phenomenon is consistent with a study by Michelon et al. (Citation2015) found that non-financial reporting practices may not provide high-quality continuous information and are only a symbolic act (Michelon et al., Citation2015). The research results related to the diffusion of non-financial reporting in public companies in Indonesia shows that the diffusion of mandatory social responsibility reports is very different from sustainable and integrated reports, which are still voluntary. So that regulation for the presentation of sustainable reports are required, they will help improve the quality of the company’s sustainable performance and support sustainable development. This research is limited to content analysis of sustainability reports; for further investigation, it is necessary to develop qualitative research, with dept-interviews, to produce a better picture of the quality of the report. Henceforth, further analysis can be carried out to identify variables that can explain the quality of the company’s sustainable performance.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nurzi Sebrina

Nurzi Sebrina is an Assistant Professor and researcher in the Department of Accounting, Universitas Negeri Padang, Indonesia. Her research interests included accounting and auditing.

Salma Taqwa

Salma Taqwa is an Assistant Professor and researcher in the Department of Accounting, Universitas Negeri Padang, Indonesia. Her research interests is financial accounting.

Mayar Afriyenti

Mayar Afriyenti is an Assistant Professor and researcher in the Department of Accounting, Universitas Negeri Padang, Indonesia. Her research interests are accounting, taxation, ethics and behaviour accounting.

Dovi Septiari

Dovi Septiari is lecturer and researcher in the Department of Accounting, Universitas Negeri Padang, Indonesia. His research interests includes Auditing, Behavioral Accounting and Business Ethics.

References

- Adaui, C. R. L. (2020) Sustainability reporting quality of Peruvian listed companies and the impact of regulatory requirements of sustainability disclosures. Sustainability. Switzerland), 12(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031135.

- Al-Shaer, H., & Zaman, M. (2016). Board gender diversity and sustainability reporting quality. Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics, 12(3), 210–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcae.2016.09.001

- Astuti, F., & Putri, W. H. (2019). Studi komparasi kualitas pengungkapan laporan keberlanjutan perusahaan konstruksi dalam dan luar negeri. Proceeding of National Conference on Accounting & Finance, 1(40), 34–46. https://doi.org/10.20885/ncaf.vol1.art4

- Aureli, S., Gigli, S., Medei, R., & Supino, E. (2020). The value relevance of environmental, social, and governance disclosure: Evidence from Dow Jones Sustainability World Index listed companies. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1772

- Bachoo, K., Tan, R., & Wilson, M. (2013). Firm value and the quality of sustainability reporting in Australia. Australian Accounting Review, 23(1), 67–87. https://doi.org/j.1835-2561.2012.00187.x

- Badia, F., & Bracci, E. (2020). Quality and Di ff usion of social and sustainability reporting in Italian public utility companies. Sustainability, 12(11), 4525. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114525

- Brammer, S., & Pavelin, S. (2004). Building a good reputation. European Management Journal, 22(6), 704–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2004.09.033

- Brønn, P. S., & Vidaver-Cohen, D. (2009). Corporate motives for social initiative: Legitimacy, sustainability, or the bottom line? Journal of Business Ethics, 87(SUPPL. 1), 91–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9795-z

- Caraiani, C. A. (2012). Social and environmental performance indicators: Dimensions of integrated reporting and benefits for responsible management and sustainability. African Journal of Business Management, 6. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM11.2347

- Chakrabarty, K. C. (2011). Non-financial reporting – what, why and how – Indian perspective. https://ideas.repec.org/p/ess/wpaper/id4175.html

- Confideration, S. E. T. U. (2012). Renewed EU strategy 2011-14 for Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). European Trade Union Confrderation. https://www.etuc.org/en/document/renewed-eu-strategy-2011-14-corporate-social-responsibility-csr

- Cooray, T., Senaratne, S., Gunarathne, A. D. N., Herath, R., & Samudrage, D. (2020). Does integrated reporting enhance the value relevance of information? Evidence from Sri Lanka. Sustainability, 12(19), 8183. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198183

- Deegan, C. M. (2019). Legitimacy theory: Despite its enduring popularity and contribution, time is right for a necessary makeover. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 32(8), 2307–2329. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-08-2018-3638

- Diouf, D., & Boiral, O. (2017). The quality of sustainability reports and impression management: A stakeholder perspective. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 30(3), 643–667. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-04-2015-2044

- Dragomir, V. D. (2012). The disclosure of industrial greenhouse gas emissions: A critical assessment of corporate sustainability reports. Journal of Cleaner Production, 29(30), 222–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.01.024

- Dyllick, T., & Hockerts, K. (2002). Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment, 11(2), 130–141. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.323

- Elkington, J. (1998). Partnerships from cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st-century business. Environmental Quality Management, 8(1), 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/tqem.3310080106

- Elkington, J. (1998). Accounting for the Triple Bottom Line. Measuring Business Excellence, 2(3), 18–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb025539

- Farhana, S., & Adelina, Y. E. (2019). Relevansi Nilai Laporan Keberlanjutan Di Indonesia. Jurnal Akuntansi Multiparadigma, 10(3), 615–628. https://dx.doi.org/10.21776/ub.jamal.2019.10.3.36

- Friedman, A. L., & Miles, S. (2001). Socially responsible investment and corporate social and environmental reporting in the UK: An explaratory study. British Accounting Review, 33(4), 523–548. https://doi.org/10.1006/bare.2001.0172

- Gallego-Álvarez, I., Prado-Lorenzo, J. M., Rodríguez-Domínguez, L., García-Sánchez, I. M., & Lamond, D. (2010). Are social and environmental practices a marketing tool?: Empirical evidence for the biggest European companies. Management Decision, 48(10), 1440–1455. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251741011090261

- Gamage, P., & Sciulli, N. (2016). Sustainability Reporting by Australian Universities. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12215

- Geerts, M., Dooms, M., & Stas, L. (2021). Determinants of sustainability reporting in the present institutional context: The case of port managing bodies. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063148

- Global Reporting Initiative. (2016). Gri 101: Foundation 2016 101. Gssb file:///D:/B Penelitian/A Penelitian Tahun 2021/GRI standard/gri-101-foundation-2016.pdf

- Hahn, R., & Kühnen, M. (2013). Determinants of sustainability reporting: A review of results, trends, theory, and opportunities in an expanding field of research. Journal of Cleaner Production, 59, 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.07.005

- Halimah, N. P., Irsyanti, A., & Aini, L. R. (2020). The value relevance of sustainability reporting: Comparison between Malaysia and Indonesia stock market. The Indonesian Journal of Accounting Research, 23(3), 447–466. https://doi.org/10.33312/ijar.502

- Hamudiana, A., & Achmad, T. (2017). Pengaruh Tekanan Stakeholder Terhadap Transparansi Laporan Keberlanjutan Perusahaan-Perusahaan Di Indonesia. Diponegoro Journal of Accounting, 6(4), 226–236. https://ejournal3.undip.ac.id/index.php/accounting/article/view/18676

- Hassan, A., Elamer, A. A., Fletcher, M., & Sobhan, N. (2020). Voluntary assurance of sustainability reporting: Evidence from an emerging economy. Accounting Research Journal, 33(2), 391–410. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARJ-10-2018-0169

- Hoque, Z., & Chia, M. (2012). Competitive forces and the levers of control framework in a manufacturing setting: A tale of a multinational subsidiary. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 9(2), 123–145. https://doi.org/10.1108/11766091211240351

- Indyanti, J. A.; Zulaikha. (2017). Assurance Laporan Keberlanjutan: Determinan Dan Konsekuensinya Terhadap Nilai Perusahaan. Diponegoro Journal of Accounting, 6(2), 103–116. https://ejournal3.undip.ac.id/index.php/accounting/article/view/18246

- Jadoon, I. A., Ali, A., Ayub, U., Tahir, M., & Mumtaz, R. (2021). The impact of sustainability reporting quality on the value relevance of corporate sustainability performance. Sustainable Development, 29(1), 155–175. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2138

- Jeanjean, T., Lesage, C., & Stolowy, H. (2010). Why do you speak English (in your annual report)? The International Journal of Accounting, 45(2), 200–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intacc.2010.04.003

- KPMG Impact. (2020). The time has come. KPMG, (December), 0–62. https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/be/pdf/2020/12/The_Time_Has_Come_KPMG_Survey_of_Sustainability_Reporting_2020.pdf

- Krzus, M. P. (2011). Integrated reporting: If not now, when? 271–276. https://www.mikekrzus.com/downloads/files/IRZ-Integrated-reporting.pdf

- Langer, M. (2006). Comparability of sustainability reports: A Comparative content analysis of Austrian sustainability reports. Sustainability Accounting and Reporting, August 2004 (pp. 581–602). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-4974-3_26

- Laplume, A. O., Sonpar, K., & Litz, R. A. (2008). Stakeholder theory: Reviewing a theory that moves us. Journal of Management, 34(6), 1152–1189. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308324322

- Michelon, G., Pilonato, S., & Ricceri, F. (2015). CSR reporting practices and the quality of disclosure: An empirical analysis. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 33, 59–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2014.10.003

- Mion, G., & Adaui, C. R. L. (2019). Mandatory nonfinancial disclosure and its consequences on the sustainability reporting quality of Italian and German companies. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(17), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174612

- Morhardt, J. E., Baird, S., & Freeman, K. (2002). Scoring corporate environmental and sustainability reports using GRI 2000, ISO 14031 and other criteria. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 9(4), 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.26

- Peck, P., & Sinding, K. (2003). Environmental and social disclosure and data richness in the mining industry. Business Strategy and the Environment, 12(3), 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.358

- Petrescu, A. G., Bîlcan, F. R., Petrescu, M., Oncioiu, I. H., Türkes, M. C., & Căpuşneanu, S. (2020). Assessing the benefits of the sustainability reporting practices in the top Romanian companies. Sustainability, 12(8), 3470. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083470

- Prinsloo, A., & Maroun, W. (2021). An exploratory study on the components and quality of combined assurance in an integrated or a sustainability reporting setting. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 12(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-05-2019-0205

- Rezaee, Z., Tsui, J., Cheng, P., & Zhou, G. (2019). Governance dimension of sustainability. Business Sustainability in Asia, 163–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119502302.ch6

- Roberts, R. W. (1992). Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure: An application of stakeholder theory. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 17(6), 595–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(92)90015-K