?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The effectiveness of the company’s financial reporting system depends on the audit’s quality. In this context, the current study examines the role of accounting and financial expertise (AFE) auditors for financial reporting quality (FRQ). Since numerous components work together to determine financial reporting quality, measuring financial reporting quality is intrinsically complex. In this regard, the reporting quality (IFRQ) is measured by using a comprehensive Index of Financial Reporting Quality. Our study’s core and robust findings showed that the sample firms’ financial reporting quality was greatly improved by having AFE directors on the audit committee. Additionally, the current study has revealed that AFE auditors greatly cut real earnings management and improved accruals quality (alternative proxies of FRQ). By using the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) econometric technique, which controls endogeneity, simultaneity, and unobserved heterogeneity, our research has shown that the audit committee’s accounting and financial competence directors play a unique role. This study may be useful for organizational leaders and policymakers from a practical standpoint.

1 Introduction

A firm’s final product from an accounting system is its financial reports. Stakeholders are a diverse group of people who use the reported information for a variety of objectives. A clear, strong, and reliable financial reporting system required to make accounting information more reliable. High-quality information is crucial for better financial performance and company decisions (Mardessi, Citation2022). The audit process verifies the figures and explanations used in financial reporting and to reflect a firm’s true financial status (Alareeni, Citation2019). The responsibility of an audit committee is to ensure the preservation, release, and quality of financial information’s disclosures (Ha, Citation2022; Nawafly & Alarussi, Citation2019). In this regard, the audit committee’s position is extremely important because it is the accountable body that oversees the entire accounting and financial reporting process.

The effectiveness or caliber of audit services provided by the audit committee is one of the most important topics in discussions about corporate governance following some large accounting mistakes in the early 2000s (J. R. Endrawes et al., Citation2020; Oussii et al., Citation2019; Pennings et al., Citation2021; J. R. Cohen et al., Citation2014; Widyaningsih et al., Citation2019; Wu et al., Citation2018). The audit committee’s effectiveness affects the caliber of financial reporting (Bajra & Čadež, Citation2018). The governing bodies of the USA and the UK have introduced a crucial mechanism through which “audit committees should possess at least one member with recent and relevant financial experience” in an effort to improve a firm’s financial reporting quality (Sarbanes Oxley Act 2002: Section 407; UK Corporate Governance Code 2003–2016: C.3.1). Scholars are paying more attention to the audit committee’s membership of people with accounting or financial knowledge with the implementation of SOX-2002. They are attempting to investigate the actual contribution of expertise to the efficiency of the audit committee. Sultana (Citation2015) asserted that the audit committee’s effectiveness is increased by its expert members in this regard. According to accounting literature about improving the financial reporting system, 57% of academics have claimed that experienced directors increase the effectiveness of the audit committee, 10% have claimed that these directors decrease its effectiveness, and the remaining 33% have claimed that there is no significant relationship between the two (Bédard & Gendron, Citation2010). The sample size, study area (country), gender difference effect, specific time period, diverse statistical procedures, may be some of the few reasons for conflicting results. Similar to this, Bilal, Chen et al.’s (Citation2018) research has also produced conflicting results about the relationship between earning quality and financial expertise on audit committees (90 studies with 165,529 firm-year observations). The conflicting findings of earlier researchers suggest that there is still much to learn about how financial competence affects financial reporting quality.

This study’s objective is to investigate whether accountants with financial competence can improve the quality of financial reporting. Since numerous components work together to determine financial reporting quality, measuring financial reporting quality is intrinsically challenging. Therefore, in order to fully encompass everything, we will create a complete index of financial reporting quality (IFRQ). The independent variable, accounting financial expertise (AFE), measures the percentage of accounting-skilled directors on the audit committee.

The findings of this study make several contributions to the literature on accounting and auditing. The current study clearly analyzes the quality of financial reporting (i.e., index of overall financial reporting quality). The most recent academics should concentrate on several factors that affect the quality of financial reporting and audit quality, according to Gaynor et al. (Citation2016)’s suggestion. Additionally, they have suggested that it is currently necessary to investigate the connections between the qualities of financial reporting and auditing. The current study pinpoints the oversight and monitoring role of accounting financial expertise directors on the audit committee (audit quality) for the quality of financial reporting in accordance with their insightful recommendations. Second, the current study adds to the literature on accounting and auditing by including the definitions of J. R. Cohen et al. (Citation2014) and Krishnan and Lee (Citation2009) for the proxy of accounting financial expertise (AFE). Tanyi and Smith (Citation2015) stressed the busyness of expertise, Krishnan et al. (Citation2011) concentrated on legal expertise directors on the audit committee, Kusnadi et al. (Citation2016) focused on mixed expertise, Shepardson (Citation2019) studied the impact of individual task-experience on financial reporting outcomes, and Sultana et al. (Citation2019) examined the impact of audit committee member experience (i.e., multiple directorships, age, and tenure of the member). Accordingly, this study will add the effect of an accountant’s financial expertise on the accuracy of financial reporting. Thirdly, to the best of my knowledge, this study is the first to use a complete index of overall financial reporting quality to quantify organizational financial reporting quality. In this regard, the current study builds on recent research by Nawafly and Alarussi (Citation2019), who looked at the effects of the audit committee’s attributes (expertise, size, and independence) on disclosure quality. Oussii et al. (Citation2019) investigated the impact of particular audit committee qualities, such as expertise, authority, diligence, size, and independence, on audit delay (timeliness). Abad and Bravo (Citation2018) have considered the connection between accounting expertise auditors and forward-looking information, and Umobong and Ibanichuka (Citation2017) tested the relationship between audit committee characteristics (such as independence and financial expertise) and reporting quality (relevance and reliability). Fourthly, endogeneity concerns are not disregarded in our study. We used the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) method to obtain accurate and impartial coefficient values. It is a trustworthy econometric approach because it manages simultaneity, unobserved heterogeneity, and dynamic endogeneity (Ullah et al., Citation2018). It also transforms stochastic errors into white noise, eliminates endogeneity, cares for unobserved fixed effects, and performs better when there are more cross-sections or groups (N) than there is time spam (T) (Asongu & De Moor, Citation2017); and correct estimations without effecting from serial correlation in stochastic terms (Shahbaz et al., Citation2019).

Section 2 presents the details of hypothesis development; section 3 reports the procedure of sample selection and includes the research methodology; and section 4 covers to the variable’s description. Section 5, with the name of “data description and regression analysis” includes descriptive statistics, correlation matrix, VIFs, and outcomes of the main analysis. Section 6 contains the details of analyses with alternative proxies of financial reporting quality. Section 7 shows the outcomes of some additional tests. We have discussed the findings of the study in section 8.

2 Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1 Accounting expertise and audit quality

The audit committee’s primary responsibility is to oversee the financial reporting process and impose restrictions on the reporting in response to the manager’s opportunistic actions. Many recent researchers have asserted, under the rubric of agency theory, that an audit committee with accounting-savvy directors is a useful tool for efficient monitoring. Strong financial backgrounds (financial competence), according to Zalata et al. (Citation2018), help auditors recognize and appreciate the complexity of financial reporting and promote the resolution of auditor-management disputes. Additionally, financial expertise auditors quiz senior personnel on technical matters, which stiffens managers’ thinking. Members of the audit committee with experience in accounting and finance greatly reduce the chance of restatement (Carcello et al., Citation2011), alleviate internal control issues (Hoitash et al., Citation2009), reduce accruals earning management (Hossain et al., Citation2011), improve the audit committee’s monitoring capacity (Albring et al., Citation2014), and lessen the exploitation of qualitative data (Lee & Park, Citation2019). Fair disclosure of information is a requirement for a high degree of audit quality, according to Kılıç and Kuzey (Citation2018) and Hassanein and Hussainey (Citation2015). Financial expertise directors considerably improve audit services’ quality (Buallay & Al-Ajmi, Citation2019); expert members also strengthen auditors’ decision-making skills and risk-management framework (Sultana et al., Citation2015).

According to the resource-dependent theory, businesses establish a line of communication with their external stakeholders in order to draw in resources. Organizations are better able to handle complicated problems due to the unique skills of experts. As a result, organizations use skilled directors as a valuable resource (Barroso et al., Citation2011). The audit committee’s top priority is to make sure that the information provided by managers is accurate and reliable. Effective auditing is a strategy used by organizations to reduce accounting information changes, which is particularly beneficial for establishing investor’s confidence and for addressing agency difficulties (Al-Matari et al., Citation2019). The audit committee’s proportion of independent members and the directors’ financial literacy both play a substantial role in limiting managers’ opportunistic behavior (Zaman Groff et al., Citation2015). Additionally, the board of directors consults with the audit committee members and regards their input as a reliable source of guidance in order to bring valuable resources into the firm (Zábojníková, Citation2016). The participation of financial knowledge on the audit committee is facilitated by resource dependency theory, according to Nawafly and Alarussi (Citation2019). According to this theory, organizations are able to preserve, utilize, and draw resources from their external environment (Ammer & Ahmad-Zaluki, Citation2017).

We have hypothesized that there may be a relationship between accounting financial knowledge and financial reporting quality, in line with accounting and auditing literature, agency and resource dependence theories, and empirical research. As a result, we have postulated that expert auditors have a considerable impact on financial reporting based on the discussion above.

H1: Accounting Financial Expertise (AFE) directors on the audit committee significantly influence the Financial Reporting Quality (FRQ) of the firm.

2.2 Audit quality and real earnings management

Accounting research on the relationship between audit quality and earnings management has shown how important a competent audit committee’s function is for improving the quality of earnings. According to the aforementioned considerations, both the provision of resources and monitoring functions (which integrate agency and resource-dependent perspectives) have a substantial impact on board capital and company strategy (Pugliese et al., Citation2009). In fact, to assure technical procedures and adhere to accounting standards during the financial reporting process, a high level of understanding is necessary (Hillman & Dalziel, Citation2003). Therefore, in order for the audit committee to perform its oversight duties more effectively, it must include some directors with a background in accounting or finance. As good monitoring raises the caliber of financial and strategic information and supports effective interaction between managers and external auditors (Abad & Bravo, Citation2018; Chang & Sun, Citation2010). Since it is required for public companies to have at least one financial expertise and declare it under sections 406 and 407 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX), many nations, including Mauritius, Slovakia, the Philippines, and India, have mandated that all members of the audit committee possess the necessary experience, education, or training in the fields of auditing, accounting, and finance in recognition of the significance of financial competence. Other nations, like Austria, China, and Russia, have mandated that the audit committee must have at least one member with knowledge of accounting and auditing (Al-Absy et al., Citation2018).

Previous research has suggested that audit committees improve financial reporting quality by lowering earnings management, delivering trustworthy financial information, and promoting voluntary disclosure of financial information (Endrawes et al., Citation2020). Through his empirical research, Alzoubi (Citation2016) has found that high audit quality considerably lowers earnings management. Additionally, he has revealed that Big-4 audit clients tend to have significantly less earnings management than other companies. We have therefore predicted the following relationship between professional auditors—whose presence improves the quality of audits—and real earnings management in light of the explanation above:

H2: Accounting Financial Expertise (AFE) directors on audit committee control real earnings management, which eventually improves the FRQ of the firm.

2.3 Audit quality and accruals based earnings management

Using total accruals and discretionary accruals, Lai et al. (Citation2018) examined the earnings quality. They have showed that by accepting more or multiple clients, auditors cast doubt on their competence. Firms with at least one expert director on the audit committee exhibit better earnings management (accrual-based), according to Be´dard et al. (Citation2004) and Hossain et al. (Citation2011). Eliwa et al. (Citation2019) used accruals quality as a proxy for earnings quality and documented that creditor’s charges rise when an organization’s earnings quality declines. The relationship between the audit fee, accrual quality, and the percentage of independent directors has been studied by Bryan and Mason (Citation2020). They stated that independent directors have a negative impact on accrual quality and a good impact on audit fee. Dhaliwal et al. (Citation2010) investigated the role of the accounting experts on the audit committee in terms of overseeing accrual quality and evaluated the personal traits of the accounting experts. Their empirical research has demonstrated that auditors with accounting expertise have a large beneficial impact on accrual quality, but auditors without accounting expertise have a negligible impact. The accruals quality is a significant predictor of earnings quality, according to Cerqueira and Pereira (Citation2017). They said that measuring earnings quality based on accruals quality is a noisy indicator and concentrated on stock market investors. Poor accruals quality, according to Cho et al. (Citation2017), increases the cash flow risk, and the auditor’s response differs depending on where the accruals quality comes from. So, on the basis of the above-mentioned discussion, we have hypothesized an association between expert auditors and accruals quality of the sample firms as follows:

H3: Accounting Financial Expertise (AFE) directors on the audit committee reduce earnings management (accruals based), which ultimately improves the FRQ of the firm.

3 Sample’s detail and research design

3.1 Sample selection

This study aims to determine the relationship between the financial reporting quality and the audit committee’s directors with accounting financial experience (AFE). Since numerous components work together to determine financial reporting quality, measuring financial reporting quality is intrinsically challenging. So, using four indicators—two forms of discretionary accruals and two types of actual earnings management—we have created a complete index of financial reporting quality (IFRQ). Our independent variable, accounting financial expertise (AFE) directors, is quantified as the share of accounting expertise directors on the audit committee (complete detail is provided in section 4; Description of Variables).

Our initial sample includes the annual data of US firms. Financial data obtained from the annual COMPUSTAT database by using Wharton Research Data Services (WRDS). Data related to audit services and accounting financial expertise downloaded from “Institutional Shareholder Services” (ISS) formerly known as RiskMetrics. After getting data, we merged data of all our concerning variables, which cover the period from 2003 to 2019. Our study did not consider many firm-year observations for final analysis due to the following several reasons. (1) we dropped all the firm-year observations of financial firms (SIC codes 6000–6999), due to different regulations and financial reporting environment from others, (2) we omitted firms with less than 10 firm-year observations, (3) we excluded all those firms which do not have sufficient data (or missing data of some variables) to run regression model, (4) while merging data obtained from two databases, we deleted firm-year observations from both sides which did not match each other. We have illustrated the full details of the number of observations included in the final analyses of the study in Table .

Table 1. Summary of Sample Derivation

3.2 Research methodology

Endogeneity bias in social science research is a significant issue that has recently come to light, according to the most recent experts. Endogeneity in regression models refers to the circumstance in which explanatory factors correlate with the error terms. When dealing with structural equation modeling, it is also practicable that the two error terms will correlate. Endogeneity prevents us from getting accurate inferences or reliable estimates. The researchers could arrive at unsuitable theoretical conclusions as a result of these erroneous inferences (Ullah et al., Citation2018). If researchers don’t account for endogeneity in their analysis, they may obtain the coefficients with the incorrect sign or even opposite indications (Ketokivi & McIntosh, Citation2017). More specifically, it is an unobservable bias that might manifest as a correlation between endogenous variables and error terms. It is challenging to ensure that the findings are entirely free from endogeneity bias because there is no statistical test that can measure it or control it directly (Roberts & Whited, Citation2013). The only possible way which scholars are using is that they try to control it or reduce its magnitude through indirect tests or by underlying precautionary measures.

Endogeneity problems are not disregarded in the current work. For that, we used the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) method to obtain accurate and trustworthy coefficient values. GMM is a dynamic panel data estimator that was developed by Arellano and Bond (Citation1991), updated by Arellano and Bover (Citation1995), and then modified and improved by Blundell and Bond (Citation1998). It is a trustworthy econometric approach because it manages simultaneity, dynamic endogeneity, and unobserved heterogeneity (Ullah et al., Citation2018), converts stochastic errors to white noise, eliminates endogeneity, and cares for unobserved fixed effects (Halkos, Citation2003), works better when the number of cross-sections or groups (N) is greater than time spam (T) (Asongu & De Moor, Citation2017; Roodman, Citation2009), and provide robust and correct estimations without effecting from serial correlation in stochastic terms (Shahbaz et al., Citation2019).

3.3 Econometric model

In conjunction with Asongu and De Moor (Citation2017), Ullah et al. (Citation2018), and Bond et al. (Citation2001), we used system GMM because it is a dynamic panel data estimator that successfully addresses (i) endogeneity problems, (ii) bias of omitted variables, (iii) unobserved panel heterogeneity, and (iv) measurement errors. Regressor’s lag levels are utilized as instruments in the difference equation, while regressor’s lag differences are used as instruments in the level equation, which further solves the concerns with reverse causation. By doing so, all parallel or orthogonal circumstances between the error term and lagged endogenous variable can be taken advantage of. The process of system GMM estimation is leveled by the equation that follows.

where

= Financial Reporting Quality of firm i at time t. In dynamic models, lag of dependent (i.e.,

) use as an instrument to control possible endogeneity.

= Constant

= Coefficient of auto-regression which is one for the specification

AFE = The proportion of Accounting Financial Expertise Directors on Audit Committee

W = Vector of control variables

= Firm-specific effect

= Time specific constant

= Error term

To test the hypothesis H1, we can rewrite equation (1) as follows:

where

= Index of financial reporting quality of firm i at time t.

To test the hypothesis H2 and H3, we can rewrite equation (1) as follows:

where

= Real earnings management of firm i at time t.

= Accruals estimation errors of firm i at time t.

4 Description of variables

4.1 Dependent variable

Financial reporting quality has been defined as the extent to which the financial statements provide reliable and fair information about underlying economic performance and financial position (Tang et al., Citation2016). Financial reporting quality is inherently difficult to measure because many factors jointly determine its quality, including accounting standards, incentives for management, and the institutional environment of a country (i.e., legal enforcement, investor protection, capital market development, and the legal and judicial system, etc.). So, to cover maximal aspects concerning to financial reporting quality, we have constructed a comprehensive index of financial reporting quality (IFRQ). According to some of the latest scholars (i.e., Arthur et al. (Citation2019), Tang et al. (Citation2016), and Dou et al. (Citation2018), a considerable variation exists in variable measurement or estimation while measuring financial reporting quality through a traditional way. So, in order to reduce the possibility of variation, they created an index that captures the financial reporting quality jointly. The current study labels it the “index of financial reporting quality” (IFRQ). In this way, the present study measures the financial reporting quality through a comprehensive proxy (index) with the help of four indicators, i.e., two types of discretionary accruals and two types of real earning management. Therefore, higher values of the index will indicate low reporting quality. Table contains the summary of all the included variables.

Table 2. Summary of Variable Measurement

Calculation of financial reporting quality index (IFRQ)

The current study constructs an index and labels it the index of overall financial reporting quality (IFRQ). A comprehensive proxy is comprised of four indicators, i.e., two types of discretionary accruals and two types of real earning management, all of which are estimated within the industry. Full details of each indicator are provided below, one by one.

Proxy # 01: Discretionary Accruals (DA1) measured as the absolute values of residuals, which are calculated through the modified Jones model for each 2-digit SIC industry year, same as Kothari et al. (Citation2005) have calculated.

where,

is the total accruals which can be calculated as:

or

for firm i in year t;

represents to income before extraordinary items,

indicates the annual change in sale, and

denotes the property, plant, and equipment of firm i and year t, respectively.

Proxy # 02: The second proxy, Discretionary Accruals (DA2) measured as the absolute values of the residuals from the modified Dechow and Dichev (Citation2002) model for each 2-digit SIC industry year.

where,

“I” is an indicator variable (dummy) with the value of 1 if there is negative CFO (economic loss) and 0 otherwise. All the other indicators are the same as already defined above.

Proxy # 03: Real Earning Management (RM1) measured through abnormal discretionary expenses and abnormal production costs. Following Dou et al. (Citation2018), we treated the residuals of normal discretionary expenses as abnormal discretionary expenses. Normal discretionary expenses of each 2-digit SIC industry year are estimated as follows:

where

Discretionary expenses (DEXP) are the sum of advertising expenses, research and development expenses, and selling, general and administrative expenses. is the annual sale/revenues of firm i in year t.

Similarly, abnormal production costs are calculated from the residuals of normal production costs. The formula to calculate normal production costs is given below:

where

Production costs are the sum of the cost of goods sold (COGS) and change in inventory ( INV). SALE is the annual sales/revenues and all the other indicators are the same as those already defined above.

To compute real earning management (RM1), which is our required proxy, we summarized the abnormal discretionary expenses and abnormal production costs after multiplying the abnormal discretionary expenses by minus one.

Proxy # 04: Real Earning Management (RM2) measured through abnormal discretionary expenses and abnormal cash flows from operating activities. Following McGuire et al. (Citation2012), we summarized the abnormal discretionary expenses and abnormal cash flows and then multiplied it with minus one. Here, abnormal discretionary expenses have been calculated using equation 7 (same as computed in proxy # 03), while the values of abnormal cash flows are generated from the residuals of normal cash flows.

where

represents the cash flows from the operating activities (OANCF) of firm i and year t. All the other indicators have been well defined above.

To obtain our required index which measures the financial reporting quality jointly we took the average of the four indicators (DA1, DA2, RM1, RM2), but before it, we ranked the values of each indicator from 0 to 9 and then divided by 9 to keep the values between 0 and 1.

4.2 Independent variable

Accounting Financial Expertise (AFE) directors on audit committee

Under section 406 and 407 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act 2002 and the final rules adopted by security exchange commission for audit committees, a person can be declared as financial expertise if he/she has (i) “accounting expertise, from work experience as a certified public accountant, auditor, chief financial officer, financial comptroller, or accounting officer”; (ii) “finance expertise, from work experience as an investment banker, financial analyst, or any other financial management role”; (iii) “supervisory expertise, from supervising the preparation of financial statements” (Dhaliwal et al. (Citation2010), p. 7 & 8 footnotes of Bédard and Gendron (Citation2010)). The presence of some accounting and financial expertise directors on the audit committee can play a vital role in enhancing the audit services. DeFond et al. (Citation2005) propose that it will be more effective if we focus on the initial definition of financial expertise. In fact, the first proposal of SEC (SEC-2002) for the definition of financial expertise was based on accounting expertise only (Krishnan & Lee, Citation2009). But in the response of some rival comments, SEC amended the definition of financial expertise and included some non-accounting experts also into the definition of financial expertise (SEC-2003). Dhaliwal et al. (Citation2010) also believe that accounting expertise is very crucial for good financial reporting as compared to any other expertise.

The present study extends the definitions of J. R. Cohen et al. (Citation2014) and Krishnan and Lee (Citation2009) for the proxy of accounting experts. In fact, our study focuses on the initial definition of the financial expertise, which is also in line with some recent scholars, i.e., Lisic et al. (Citation2019), Chychyla et al. (Citation2019), and Bravo and Alcaide-Ruiz (Citation2019). So, an individual will be considered as accounting financial expertise (AFE) if he/she fulfills the following requirements: (a) a certified public accountant or other similar qualification (b) he/she has experience as a treasurer, a controller, an auditor, chief financial officer, or a tax professional, etc. Hence, the final proxy of accounting financial expertise (AFE) is the proportion of accounting expertise directors on the audit committee.

4.3 Control variable

In this section, we have discussed briefly the other possible variables which may affect the financial reporting quality or audit quality. It is necessary to undertake all those variables also which influence the audit quality to get unbiased and true estimations (Hai et al., Citation2019). So, we have included a set of variables as exogenous variables in the regression model to control their direct/indirect impact on our variable of interests.

Large board and large size of the audit committee with diversified experience may affect the opportunistic practices of the managers (Rahman et al., Citation2006). So, we included the size of the board (SB) and the size of the audit committee (SAC) as control variables in the model. Prior auditing studies have exposed that those firms which audited by big audit firms have fewer earnings manipulations due to the high quality of audit services (Dzikrullah et al., Citation2020; Gavious et al., Citation2012). So, we added Big-4 (B4) as a dummy variable in the regression model. According to Shu et al. (Citation2015) and Francis and Wang (Citation2008), due to firm complexity, large firms show less accrual quality as compared to small firms. According to Garcia-Blandon et al. (Citation2021), large firms involve more in the activities of earnings management as compared to small firms. So, we controlled the influence of large firms by including Size of Firm (SF) as a control variable. Klein (Citation2002) has exposed that independent directors have more concerns about monitoring managerial activities as compared to other directors. The current study includes the proportion of independent directors (IND) in the model to control the influence of independent directors on earnings quality. According to Be´dard et al. (Citation2004), outside directors influence more actively with their extra knowledge and high governing skills, which they gain from additional (outside) directorship. So, this study controls their effect by including the proportion of non-executive directors (NED) as a control variable. Manager’s enthusiasm increases to engage in earnings manipulations when the firm will be in the situation of trouble (Ittonen et al., Citation2013), while managers are less likely to involve in earnings management, who are engaged with the firms with the high level of cash flows (Gul et al., Citation2009; Raweh et al., Citation2021). So, we included a dummy variable loss (LOSS), return on asset (ROA), and cash flow (CFO) to control the said situations. We included leverages (LEV) to control the impact of financial leverages. McVay (Citation2006) advocates that managers manipulate earnings to meet their own targets or to meet the analyst’s forecasts. So, market to book value (MBV) is the most suitable proxy to control it. With the high growth of sales, firms have account complications or somehow difficult audit procedures, which increase the opportunities for the manager to manipulate earrings (Srinidhi et al., Citation2011). The current study controls it by including a percentage change in the sale as a control variable. Similarly, according to Fan et al. (Citation2010) and Barton and Simko (Citation2002), habitual managers are normally involved in earnings manipulation again and again. So, the current study included net operating assets (NOA) as a control variable.

5. Data Description and regression analysis

5.1 Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics are presented in Table . The study’s final analysis spans the years 2003–2019 and includes 35,694 firm-year observations. Our dependent variable’s mean value is 0.42023 for the financial reporting index. According to statistics, audit committees often consist of 30% financial experts, ranging from 0.032077 to 0.66667. The statistical values of the corporate governance variables show that the sample firms’ boards have a maximum and minimum membership of 30 and 3, respectively. The average number of members on the boards of sample firms is 9, with around 71% of them being independent directors and approximately 58% holding additional directorships, according to the mean values of SB, IND, and NED. The average number of members on an audit committee, which can range from 4 to 26, is 7, according to the mean value of the committee’s size. The Big 4 audit firms were used by about 20% of sample companies, according to the mean value of B4, which is 0.19796. The average loss is 0.31493, indicating that 31.493% of the sample companies on average have negative income (economic loss). The average values of the other control variables, including SF, LEV, CFO, ROA, MBV, NOA, and SALE, are 4.89644, 0.61919, −0.00045, −0.01604, 2.00374, 5.62565, and 4.10048, respectively.

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics (2003–2019)

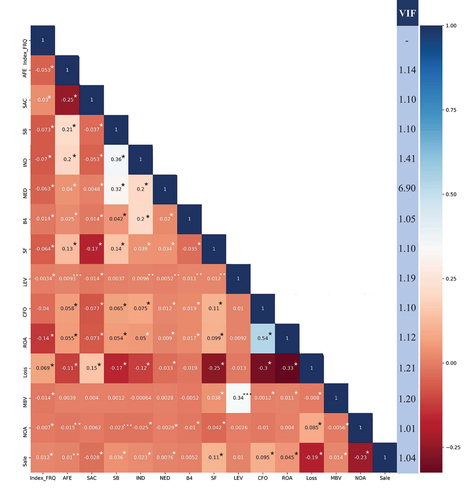

5.2 Pairwise correlation and variance inflation factor

Figure tabulates the pairwise correlation matrix and VIF values for the relevant variables. The correlation coefficients show a strong inverse relationship between the index values and accounting financial knowledge. In addition, all of the control variables—aside from SAC and NOA, which are positively connected—are strongly and adversely correlated with the index values. Even if there is a statistically significant association between accounting financial expertise and the index values, these are just initial findings. The final judgment will be made after controlling the potential impact of several factors that could affect the relationship between accounting financial knowledge and earnings quality.

Figure 1. Pairwise correlation matrix & Variance Inflation Factor (VIF).

The second-to-last column of Figure holds the values of variance inflation factor (VIF) for all the independent variables (i.e., AFE, SAC, SB, IND, NED, B4, SF, LEV, CFO, ROA, LOSS, MBV, NOA, and SALE). The VIFs of all the independent variables are less than 2, except for NED, which contains 6.90. In general, the numerical value of VIF is acceptable up to 10, because most commonly, practitioners follow the rule of 10. Overall, the VIFs of all the variables are less than the critical value of 10 (O’brien, Citation2007). So, we do not find any potential multicollinearity issues among variables. Hence, we can believe that our analysis results will be free from sway or bias, i.e., issues of strong multicollinearity. Subsequently, we can move forward with this set of variables because the VIFs and correlations among the variables are within the acceptable limit.

5.3 Outcomes of multivariate empirical analysis

The inclusion of audit committee directors with accounting and financial experience (AFE) has a considerable impact on the accuracy of the company’s financial reporting, as predicted in hypothesis H1. We used the system GMM approach to run the regression between AFE and IFRQ in order to test this prediction. The results of the connection between AFE and IFRQ are shown in Table . The coefficient value of AFE is −0.52754 and statistically significant (p < 5%), which reveals that a significant negative association exists between AFE and IFRQ (see column 2 of Table ). More specifically, these regression results imply that increasing the proportion of AFE on the audit committee will greatly improve the sample firms’ reporting quality. These findings support H1 by showing that the audit committee’s monitoring effectiveness is improved by the inclusion of AFE directors, which in turn improves the firm’s reporting quality.

Table 4. Association between AFE Auditors and IFRQ

The correlation of additional governance factors, such as the size of the audit committee, improves the sample firms’ reporting quality. These results imply that larger audit committees, as compared to smaller audit committees, effectively supervise the accounting process. According to descriptive statistics, sample firms’ audit committees typically contain seven members (including one with a 30% financial background). We therefore advise that the audit committee should have at least seven members in order for it to function properly based on our findings. The coefficient of independent directors on the board is negative and statistically highly significant

.

It reveals that having more independent directors raise the standard of the sample firms’ financial reporting. The association of the big-4 audit companies is unfavorable and statistically significant , indicating that the reporting quality of the organizations who use the big-4 audit firms has improved. Similar to this, the quality of the sample firms’ financial reporting is significantly impacted negatively by the firm’s size

, CFO

,and growth in sales

. NED

, LOSS

, and NOA

are the markers that significantly lower the sample firms’ financial reporting quality, according to the coefficients of NED, LOSS, and NOA. Moreover, the coefficients of the size of the board (SB), leverages (LEV), return on asset (ROA), and market to book value (MBV) do not show statistically significant association with financial reporting quality of the sample firms.

Table bottom section contains the model’s key diagnostics. It shows that there are fewer instruments than groups, which proves that the instruments are exogenous as a whole. The general guideline is that there must be fewer instruments than there are groups, or at least an equal number of instruments (O’brien, Citation2007). The null hypothesis for the Arellano-Bond (AR) test for autocorrelation is “no autocorrelation.” The first-order and second-order Arellano-Bond tests, respectively, are AR[1] and AR[2], where AR[2] is crucial (Mileva, Citation2007). Statistically speaking, the AR[2] p-value is not significant (p > 10%). As a result, we are unable to rule out the possibility of autocorrelation. The Wald test, or Wald Chi-Square test, is used to confirm that all the explanatory variables are jointly adding something to the model or not. It has a null hypothesis: “At least one regressor is zero.”Footnote1 Here, the value of the Wald test is highly statistically significant. So, we reject the null hypothesis or accept the alternative, which means that at least one regressor is not equal to zero. After the above discussion, we are able to say that all the coefficients are free of autocorrelation problems, the instruments are valid, and all the regressors are adding something jointly

6. Alternative proxies

We have employed two proxies (real earnings management and accruals estimation errors) to test the hypotheses H2 and H3. The details of each proxy and its regression outcomes are given in the following subsections.

6.1 Real earnings management

In some cases, individual indicators provide deeper information about real earning management than the index of particular variables (Chi et al., Citation2011). We used three proxies for actual earnings management, including abnormal discretionary expenses (ADE), abnormal cash flows from operating activities (ACFO), and abnormal production cost, in accordance with two well-known studies D. A. D. A. Cohen et al. (Citation2008) and Roychowdhury (Citation2006). Equations (7)—(10) have been used to calculate the residuals of ADE, ACFO, and APC, which correspond to their abnormal values (9).

We have predicted through hypothesis H2; AFE directors on the audit committee actively control real earnings management, which eventually improves the financial reporting quality of the firm. To test our prediction, we ran the regression between AFE and real earnings management by employing equation 3. Table illustrates the regression outcomes between real earnings management and AFE auditors. The coefficient of AFE reveals that AFE auditors have a significant negative impact on ADE (see columns 2 and 3 of Table ). It demonstrates that the presence of expertise auditors on the audit committee significantly reduces the real earnings management (i.e., managing discretionary expenses). The second proxy of real earnings management is ACFO (sell column 4 and 5 of Table ). Its association with AFE is also negative and highly significant

. Similarly, AFE directors have a significant and negative influence

on APC, which is the third proxy of real earnings management (see columns 6 and 7 of Table ). Overall, these regression outcomes suggest that a higher proportion of AFE on the audit committee will significantly enhance the reporting quality of the sample firms by controlling real earnings management. Consistent with H2, these results provide evidence that the presence of AFE directors on the audit committee improves its monitoring efficiency, which ultimately increases the firm’s reporting quality.

Table 5. Association between AFE Auditors and Real Earnings Management

The influence of other governance variables on real earnings management reveals that the size of the board, size of the audit committee, ROA, and MBV have a significant negative association with ADE, ACFO, and APC. The coefficients of NED, CFO, and NOA expose that these indicators have a positive (negative) relationship with ACFO and APC (ADE). Sales growth and B4 show the positive (negative) link with ADE and APC (ACFO). Moreover, SF and LEV with ADE, SB with ACFO, and LOSS and NOA with APC, do not show statistically significant affiliation.

6.2 Accruals estimation errors

The current study measures the earnings quality through Accruals Estimation Errors (AEE) by employing the proposed model of McNichols (Citation2002). The detail of the model is given below:

where

is representing working capital accruals which can be calculated with the following formula:

( Current Assets—

Cash)—(

Current Liabilities—

Current Long-term Debt)

,

,

and

denote to total assets, cash flow from operations, change in annual sales, and gross property, plant and equipment for the company i and year t, respectively.

The current study uses the absolute values of the residuals from the McNichols regression for each two-digit SIC industry to calculate the final values of Accruals Estimation Errors (AEE). In this case, greater absolute values of AEE will signify inadequate financial reporting quality and poor accruals quality.

Through hypothesis H3, we hypothesized that audit committee members with accounting financial expertise (AFE) would decrease accruals estimation errors (AEE), which would ultimately enhance the firm’s financial reporting quality. We used equation 4 to run the regression between AFE and AEE in order to test our prediction. There is a statistically significant negative correlation between AFE and AEE, as shown by the coefficient value of AFE, which is −19.7563 and p < 5% (see column 2 of Table ). More specifically, these regression results imply that a greater percentage of AFE on the audit committee will significantly lower the sample firms’ accrual estimation mistakes. In line with H3, it offers proof that the audit committee’s inclusion of AFE directors improves the firm’s reporting quality through high accrual quality. The association of other governance variables, i.e., the board size , size of the audit committee

, sale’s growth

, and the proportion of independent directors

with AEE, is positive and statistically significant. The coefficients of firm size

, CFO

, ROA

, and LOSS

are negative and statistically significant. Moreover, market to book value (MBV) and leverages (LEV) have no statistically significant association with AEE.

Table 6. Association between AFE Auditors and AEE

Overall, analysis of this study divulges that the presence of AFE directors on the audit committee significantly enhances the financial reporting quality of the sample firms. More precisely, from these findings we can say that AFE auditors actively control earnings management (accruals based) and real earnings management as well. Eventually, it enhances the reporting quality of the sample firms.

7. Robust analysis

To re-estimate the relationship between AFE auditors and the financial reporting quality of the sample firms, we will add some new analyses in this section. Table lists the results of regression using the fixed effect (FE) and random effect (RE) estimators as an alternate methodology. Even though endogeneity problems are not addressed by these econometric methodologies, the results pertaining to our key variables are reliable and support our earlier findings. The statistically significant coefficient value of AFE is −0.0248 (p < 10%), indicating that there is a significant inverse relationship between AFE and IFRQ (see column 2 of Table ). Similar evidence of the relationship between AFE and IFRQ can be seen in column 3 of table . These results support the prior findings using the GMM approach, which is in line with H1. According to the coefficients of AFE with regard to ADE, ACFO, and APC, AFE auditors significantly harm ADE, ACFO, and APC (see columns 3–8 of Table ). It reveals that the audit committee’s ability to manage real earnings is greatly reduced by the presence of experienced auditors, and these conclusions are nearly identical to earlier ones (support H2). Table final two columns present the results of a regression between AFE and AEE using FE and RE estimators. These regression results imply that a higher percentage of AFE on the audit committee would significantly lower the sample firms’ accrual estimation mistakes (support H3).

Table 7. The Regression Outcomes of Fixed Effect (FE) and Random Effect (RE)

8. Discussion of results and recommendations of the study

Although there are many different FRQ measures described in the literature, the most recent academics recommend creating an index as the best. It reduces the potential volatility of the variable measurement and incorporates a variety of widely used proxies for financial reporting quality. Recent researchers have used an index to measure financial reporting quality. For instance, Dou et al. (Citation2018) looked at the relationship between block-holder exit threats and the index of financial reporting quality; Tang et al. (Citation2016) used an index to measure financial reporting quality at the national level; and Arthur et al. (Citation2019) looked at the effect of ownership concentration on the index of financial reporting quality. As a result, the current study also used a thorough index of FRQ to quantify financial reporting quality.

The findings of the current study have shown that the sample firms’ financial reporting quality is greatly improved by the inclusion of AFE directors on the audit committee. AFE auditors greatly improve the accruals quality of the sample firms and significantly reduce real earnings management, according to assessments using other proxies of FRQ. Overall, this study’s findings are consistent with hypotheses H1, H2, and H3. Our results are consistent with earlier studies that showed governance expertise on audit committees (Yang & Krishnan, Citation2005), diversity management development (Labelle et al., Citation2010), and legal expertise on audit committees (Krishnan et al., Citation2011) all significantly reduced the management of the firm’s earnings. Hence, the important implications of the study concerning audit quality are:

The nomination of the audit committee’s members should be based on the necessary personal traits (i.e., competencies, education, experience, skills, etc.) to efficiently oversee or monitor the accounting and financial processes instead of their appointment through a traditional process.

There must be at least two members with accounting and financial expertise on the audit committee because they can handle complex financial entities more effectively than others.

Only an effective audit committee can prevent managers from manipulating accounts and make financial information more transparent. Transparency is necessary not only for the organization’s own sake but also for all other stakeholders.

9 Conclusion

The aim of the study is to determine the relationship between the caliber of financial reporting and accounting financial expertise (AFE) auditors. Since several factors work together to determine financial reporting quality, it is inherently challenging to measure. As a result, we have used an index to quantify reporting quality in order to account for all relevant components of financial reporting quality (i.e., IFRQ). Endogeneity bias in the study of social sciences is a significant new problem that the most recent scholars have emphasized. The Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) technique, a dependable econometric method that manages dynamic endogeneity, simultaneity, and unobserved heterogeneity, was used to regulate it.

Our study’s findings demonstrated that the presence of AFE directors on the audit committee significantly improves the sample firms’ financial reporting quality. Moreover, analyses with alternative proxies of FRQ have exposed that AFE auditors significantly reduce the real earnings management and enhance the accrual quality of the sample firms. Overall, our findings have revealed that the role of accounting and financial expertise on the audit committee is exclusive. So, our research is valuable to the existing literature of corporate governance and auditing by revealing the role of AFE auditors in providing good audit services. In a practical aspect, this research is also valuable for policymakers and organizational leaders because it reveals the association between AFE auditors and reporting quality. They should keep in mind this association with AFE if they want to prompt revolutions in legislative regulations and management mechanisms concerning financial reporting quality.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Because all the regressors jointly add something to the predictor, if anyone will be zero then they cannot add something.

References

- Abad, C., & Bravo, F. (2018). Audit committee accounting expertise and forward-looking disclosures. Management Research Review, 41(2), 166–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-02-2017-0046

- Al-Absy, M. S. M., Isamil, K. N. I. K., & Chandren, S. (2018). Accounting expertise in the audit committee and earnings management. Business and Economic Horizons, 14(3), 451–476. https://doi.org/10.15208/beh.2018.33

- Alareeni, B. A. (2019). The associations between audit firm attributes and audit quality-specific indicators. Managerial Auditing Journal, 34(1), 6–43. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-05-2017-1559

- Albring, S., Robinson, D., & Robinson, M. (2014). Audit committee financial expertise, corporate governance, and the voluntary switch from auditor-provided to non-auditor-provided tax services. Advances in Accounting, 30(1), 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adiac.2013.12.007

- Al-Matari, E. M., Al-Dhaafri, H. S., & Al-Swidi, A. K. (2019). The effect of government ownership, foreign ownership, institutional ownership, and audit quality on firm performance of listed companies in Oman: A conceptual framework. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Future of ASEAN (ICoFA) 2017 - Volume 1 (Vol. 1, pp. 585–595). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-8730-1_59

- Alzoubi, E. S. S. (2016). Audit quality and earnings management: Evidence from Jordan. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 17(2), 170–189. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAAR-09-2014-0089

- Ammer, M. A., & Ahmad-Zaluki, N. A. (2017). The role of the gender diversity of audit committees in modelling the quality of management earnings forecasts of initial public offers in Malaysia. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 32(6), 420–440. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-09-2016-0157

- Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297. https://academic.oup.com/restud/article-abstract/58/2/277/1563354

- Arellano, M., & Bover, O. (1995). Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics, 68(1), 29–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(94)01642-D

- Arthur, N., Chen, H., & Tang, Q. (2019). Corporate ownership concentration and financial reporting quality. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 17(1), 104–132. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRA-07-2017-0051

- Asongu, S. A., & De Moor, L. (2017). Financial globalisation dynamic thresholds for financial development: Evidence from Africa. The European Journal of Development Research, 29(1), 192–212. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2016.10

- Bajra, U., & Čadež, S. (2018). Audit committees and financial reporting quality: The 8th EU Company Law Directive perspective. Economic Systems, 42(1), 151–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecosys.2017.03.002

- Barroso, C., Villegas, M. M., & Pérez-Calero, L. (2011). Board Influence on a Firm’s Internationalization. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 19(4), 351–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2011.00859.x

- Barton, J., & Simko, P. J. (2002). The balance sheet as an earnings management constraint. The Accounting Review, 77(s–1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2002.77.s-1.1

- Be´dard, J., Chtourou, S. M., & Courteau, L. (2004). The effect of audit committee expertise, independence, and activity on aggressive earnings management. AUDITING: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 23(2), 13–35. https://doi.org/10.2308/aud.2004.23.2.13

- Bédard, J., & Gendron, Y. (2010). Strengthening the financial reporting system: Can audit committees deliver? International Journal of Auditing, 210, 174–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-1123.2009.00413.x

- Bilal, Chen, S., Komal, B., & Komal, B. (2018). Audit committee financial expertise and earnings quality: A meta-analysis. Journal of Business Research, 84(November 2016), 253–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.11.048

- Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(2), 1115–1143. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(98)00009-8

- Bond, S. S., Hoeffler, A., & Temple, J. (2001). GMM estimation of empirical growth models. Economics Papers, 01, 33. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?Abstract_id=290522

- Bravo, F., & Alcaide-Ruiz, M. D. (2019). The disclosure of financial forward-looking information. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 34(2), 140–156. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-09-2018-0120

- Bryan, D. B., & Mason, T. W. (2020). Independent director reputation incentives, accruals quality and audit fees. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, jbfa.12435. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbfa.12435

- Buallay, A., & Al-Ajmi, J. (2019). The role of audit committee attributes in corporate sustainability reporting. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 21(2), 249–264. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAAR-06-2018-0085

- Carcello, J. V., Hermanson, D. R., & Ye, Z. (2011). Corporate governance research in accounting and auditing: Insights, practice implications, and future research directions. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 30(3), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-10112

- Cerqueira, A., & Pereira, C. (2017). Accruals quality, managers’ incentives and stock market reaction: Evidence from Europe. Applied Economics, 49(16), 1606–1626. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2016.1221047

- Chang, J., & Sun, H. (2010). Does the disclosure of corporate governance structures affect firms’ earnings quality? Review of Accounting and Finance, 9(3), 212–243. https://doi.org/10.1108/14757701011068048

- Chen, S., Chen, X., Cheng, Q., & Shevlin, T. (2010). Are family firms more tax aggressive than non-family firms?. Journal of Financial Economics, 95(1), 41–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2009.02.003

- Chi, W., Lisic, L. L., & Pevzner, M. (2011). Is enhanced audit quality associated with greater real earnings management? Accounting Horizons, 25(2), 315–335. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch-10025

- Cho, M., Ki, E., & Kwon, S. Y. (2017). The effects of accruals quality on audit hours and audit fees. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 32(3), 372–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148558X15611323

- Chychyla, R., Leone, A. J., & Minutti-Meza, M. (2019). Complexity of financial reporting standards and accounting expertise. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 67(1), 226–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2018.09.005

- Cohen, D. A., Dey, A., & Lys, T. Z. (2008). Real and accrual-based earnings management in the pre- and post-sarbanes-oxley periods. The Accounting Review, 83(3), 757–787. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2008.83.3.757

- Cohen, J. R., Hoitash, U., Krishnamoorthy, G., & Wright, A. M. (2014). The effect of audit committee industry expertise on monitoring the financial reporting process. The Accounting Review, 89(1), 243–273. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-50585

- Dechow, P. M., & Dichev, I. D. (2002). The quality of accruals and earnings: The role of accrual estimation errors. The Accounting Review, 77(SUPPL), 35–59. https://dx.doi.org/10.2308/accr.2002.77.s-1.35

- DeFond, M. L., Hann, R. N., & Hu, X. (2005). Does the market value financial expertise on audit committees of boards of directors? Journal of Accounting Research, 43(2), 153–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679x.2005.00166.x

- Dhaliwal, D., Naiker, V., & Navissi, F. (2010). The association between accruals quality and the characteristics of accounting experts and mix of expertise on audit committees*. Contemporary Accounting Research, 27(3), 787–827. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.2010.01027.x

- Dou, Y., Hope, O. K., Thomas, W. B., & Zou, Y. (2018). Blockholder exit threats and financial reporting quality. Contemporary Accounting Research, 35(2), 1004–1028. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12404

- Dzikrullah, A. D., Harymawan, I., Ratri, M. C., & Ntim, C. G. (2020). Internal audit functions and audit outcomes: Evidence from Indonesia. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1750331. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1750331

- Eliwa, Y., Gregoriou, A., & Paterson, A. (2019). Accruals quality and the cost of debt: The European evidence. International Journal of Accounting & Information Management, 27(2), 333–351. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJAIM-01-2018-0008

- Endrawes, M., Feng, Z., Lu, M., & Shan, Y. (2020). Audit committee characteristics and financial statement comparability. Accounting & Finance, 60(3), 2361–2395. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12354

- Fan, Y., Barua, A., Cready, W. M., & Thomas, W. B. (2010). Managing earnings using classification shifting: evidence from quarterly special items. The Accounting Review, 85(4), 1303–1323. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2010.85.4.1303

- Francis, J. R., & Wang, D. (2008). The joint effect of investor protection and big 4 audits on earnings quality around the world. Contemporary Accounting Research, 25(1), 157–191. https://doi.org/10.1506/car.25.1.6

- Garcia-Blandon, J., Castillo-Merino, D., Argilés-Bosch, J. M., & Ravenda, D. (2021). Mandatory joint audit and audit quality in the context of the European blue chips. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 22(5), 1378–1395. https://doi.org/10.3846/jbem.2021.14959

- Gavious, I., Segev, E., & Yosef, R. (2012). Female directors and earnings management in high‐technology firms. Pacific Accounting Review, 24(1), 4–32. https://doi.org/10.1108/01140581211221533

- Gaynor, L. M., Kelton, A. S., Mercer, M., & Yohn, T. L. (2016). Understanding the relation between financial reporting quality and audit quality. AUDITING: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 35(4), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-51453

- Gul, F. A., Fung, S. Y. K., & Jaggi, B. (2009). Earnings quality: Some evidence on the role of auditor tenure and auditors’ industry expertise. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 47(3), 265–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2009.03.001

- Ha, H. H. (2022). Audit committee characteristics and corporate governance disclosure: Evidence from Vietnam listed companies. Cogent Business and Management, 9(1). 2119827. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2119827

- Hai, P. T., Tu, C. A., & Toan, L. D. (2019). Research on factors affecting organizational structure, operating mechanism and audit quality: An empirical study in Vietnam. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 20(3), 526–545. https://doi.org/10.3846/jbem.2019.9791

- Halkos, G. E. (2003). Environmental Kuznets curve for sulfur: Evidence using GMM estimation and random coefficient panel data models. Environment and Development Economics, 8(4), 581–601. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X0300317

- Hassanein, A., & Hussainey, K. (2015). Is forward-looking financial disclosure really informative? Evidence from UK narrative statements. International Review of Financial Analysis, 41, 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2015.05.025

- Hillman, A. J., & Dalziel, T. (2003). Boards of directors and firm performance: Integrating agency and resource dependence perspectives. Academy of Management Review, 28(3), 383–396. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2003.10196729

- Hoitash, U., Hoitash, R., & Bedard, J. C. (2009). Corporate governance and internal control over financial reporting: A comparison of regulatory regimes. The Accounting Review, 84(3), 839–867. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2009.84.3.839

- Hossain, M., Mitra, S., Rezaee, Z., & Sarath, B. (2011). Corporate governance and earnings management in the pre– and post–Sarbanes-oxley act regimes. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 26(2), 279–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148558X11401218

- Ittonen, K., Vähämaa, E., & Vähämaa, S. (2013). Female auditors and accruals quality. Accounting Horizons, 27(2), 205–228. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch-50400

- Ketokivi, M., & McIntosh, C. N. (2017). Addressing the endogeneity dilemma in operations management research: Theoretical, empirical, and pragmatic considerations. Journal of Operations Management, 52(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2017.05.001

- Kılıç, M., & Kuzey, C. (2018). Determinants of forward-looking disclosures in integrated reporting. Managerial Auditing Journal, 33(1), 115–144. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-12-2016-1498

- Klein, A. (2002). Audit committee, board of director characteristics, and earnings management. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 33(3), 375–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-4101(02)00059-9

- Kothari, S. P., Leone, A. J., & Wasley, C. E. (2005). Performance matched discretionary accrual measures. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39(1), 163–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2004.11.002

- Krishnan, J., & Lee, J. E. (2009). Audit committee financial expertise, litigation risk, and corporate governance. AUDITING: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 28(1), 241–261. https://doi.org/10.2308/aud.2009.28.1.241

- Krishnan, J., Wen, Y., & Zhao, W. (2011). Legal expertise on corporate audit committees and financial reporting quality. The Accounting Review, 86(6), 2099–2130. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-10135

- Kusnadi, Y., Leong, K. S., Suwardy, T., & Wang, J. (2016). Audit committees and financial reporting quality in Singapore. Journal of Business Ethics, 139(1), 197–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2679-0

- Labelle, R., Gargouri, R. M., & Francoeur, C. (2010). Erratum to: Ethics, diversity management, and financial reporting quality. Journal of Business Ethics, 93(2), 355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0456-7

- Lai, K. M. Y., Sasmita, A., Gul, F. A., Foo, Y. B., & Hutchinson, M. (2018). Busy auditors, ethical behavior, and discretionary accruals quality in Malaysia. Journal of Business Ethics, 150(4), 1187–1198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3152-4

- Lee, J., & Park, J. (2019). The impact of audit committee financial expertise on management discussion and analysis (MD&A) Tone. European Accounting Review, 28(1), 129–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2018.1447387

- Lisic, L. L., Myers, L. A., Seidel, T. A., & Zhou, J. (2019). Does audit committee accounting expertise help to promote audit quality? Evidence from auditor reporting of internal control weaknesses. Contemporary Accounting Research, 36(4), 2521–2553. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12517

- Mardessi, S. (2022). Audit committee and financial reporting quality: The moderating effect of audit quality. Journal of Financial Crime, 29(1), 368–388. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-01-2021-0010

- McGuire, S. T., Omer, T. C., & Sharp, N. Y. (2012). The impact of religion on financial reporting irregularities. The Accounting Review, 87(2), 645–673. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-10206

- McNichols, M. F. (2002). Discussion of the quality of accruals and earnings: The role of accrual estimation errors. The Accounting Review, 77(s–1), 61–69. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2002.77.s-1.61

- McVay, S. E. (2006). Earnings management using classification shifting: An examination of core earnings and special items. The Accounting Review, 81(3), 501–531. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2006.81.3.501

- Mileva, E. (2007). Using Arellano-Bond dynamic panel GMM estimators in Stata. Economic Department Fordham Universiyt, 64(1), 1–10.

- Nawafly, A. T., & Alarussi, A. S. (2019). Impact of board characteristics, audit committee characteristics and external auditor on disclosure quality of financial reporting. Journal of Management and Economic Studies, 1(1), 48–65. https://doi.org/10.26677/TR1010.2019.60

- O’brien, R. M. (2007). A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Quality & Quantity, 41(5), 673–690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-006-9018-6

- Oussii, A. A., Klibi, M. F., & Ouertani, I. (2019). Audit committee role: Formal rituals or effective oversight process? Managerial Auditing Journal, 34(6), 673–695. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-11-2017-1708

- Pennings, E., Georgakopoulos, G., Sikalidis, A., & Grose, C. (2021). ABNORMAL AUDIT FEES AND AUDIT QUALITY: THE INFLUENCE OF FINANCIAL EXPERTISE IN THE AUDIT COMMITTEE. Intellectual Economics, 15(2). https://ojs.mruni.eu/ojs/intellectual-economics/article/view/6981

- Pugliese, A., Bezemer, P.-J., Zattoni, A., Huse, M., Van den Bosch, F. A. J., & Volberda, H. W. (2009). Boards of directors’ contribution to strategy: a literature review and research Agenda. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 17(3), 292–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2009.00740.x

- Rahman, R. A., Ali, F. H. M., & Haniffa, R. (2006). Board, audit committee, culture and earnings management: Malaysian evidence. Managerial Auditing Journal, 21(7), 783–804. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686900610680549

- Raweh, N. A. M., Abdullah, A. A. H., Kamardin, H., & Malek, M. (2021). Industry expertise on audit committee and audit report timeliness. Cogent Business and Management, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1920113

- Roberts, M. R., & Whited, T. M. (2013). Endogeneity in Empirical Corporate Finance. Handbook of the Economics of Finance, 2(PA), 493–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-44-453594-8.00007-0

- Roodman, D. (2009). How to do xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. Stata Journal, 9(1), 86–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867x0900900106

- Roychowdhury, S. (2006). Earnings management through real activities manipulation. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 42(3), 335–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2006.01.002

- Shahbaz, M., Balsalobre-Lorente, D., & Sinha, A. (2019). Foreign direct Investment–CO2 emissions nexus in Middle East and North African countries: Importance of biomass energy consumption. Journal of Cleaner Production, 217, 603–614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.282

- Shepardson, M. L. (2019). Effects of individual task-specific experience in audit committee oversight of financial reporting outcomes. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 74, 56–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2018.07.002

- Shu, P.-G., Yeh, Y.-H., Chiu, S.-B., & Yang, Y.-W. (2015). Board external connectedness and earnings management. Asia Pacific Management Review, 20(4), 265–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2015.03.003

- Srinidhi, B., Gul, F. A., & Tsui, J. (2011). Female Directors and Earnings Quality*. Contemporary Accounting Research, 28(5), 1610–1644. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.2011.01071.x

- Sultana, N. (2015). Audit committee characteristics and accounting conservatism. International Journal of Auditing, 19(2), 88–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijau.12034

- Sultana, N., Singh, H., & Rahman, A. (2019). Experience of audit committee members and audit quality. European Accounting Review, 28(5), 947–975. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2019.1569543

- Sultana, N., Singh, H., & Van der Zahn, J. L. W. M. (2015). Audit committee characteristics and audit report lag. International Journal of Auditing, 19(2), 72–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijau.12033

- Tang, Q., Chen, H., & Lin, Z. (2016). How to measure country-level financial reporting quality? Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 14(2), 230–265. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRA-09-2014-0073

- Tanyi, P. N., & Smith, D. B. (2015). Busyness, expertise, and financial reporting quality of audit committee chairs and financial experts. AUDITING: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 34(2), 59–89. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-50929

- Ullah, S., Akhtar, P., & Zaefarian, G. (2018). Dealing with endogeneity bias: The generalized method of moments (GMM) for panel data. Industrial Marketing Management, 71(November), 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.11.010

- Umobong, A. A., & Ibanichuka, E. A. L. (2017). Audit committee attributes and financial reporting quality of food and beverage firms in Nigeria. International Journal of Innovative Social Sciences & Humanities Research, 5(2), 1–13. https://www.seahipaj.org/journals-ci/june-2017/IJISSHR/full/IJISSHR-J-1-2017.pdf

- Vasilescu, C., & Millo, Y. (2016). Do industrial and geographic diversifications have different effects on earnings management? Evidence from UK mergers and acquisitions. International Review of Financial Analysis, 46, 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2016.04.009

- Widyaningsih, I. A., Harymawan, I., Mardijuwono, A. W., Ayuningtyas, E. S., Larasati, D. A., & Ntim, C. G. (2019). Audit firm rotation and audit quality: Comparison before vs after the elimination of audit firm rotation regulations in Indonesia. Cogent Business and Management, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2019.1695403

- Wu, J., Habib, A., Weil, S., & Wild, S. (2018). Exploring the identity of audit committee members of New Zealand listed companies. International Journal of Auditing, 22(2), 164–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijau.12111

- Yang, J. S., & Krishnan, J. (2005). Audit committees and quarterly earnings management. Audit Committees and Quarterly Earnings Management. International Journal of Auditing, 219(3), 201–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-1123.2005.00278.x

- Zábojníková, G. (2016). The audit committee characteristics and firm performance: Evidence from the UK dissertation master in finance. 1–52. https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/bitstream/10216/84439/2/138239.pdf

- Zalata, A. M., Tauringana, V., & Tingbani, I. (2018). Audit committee financial expertise, gender, and earnings management: Does gender of the financial expert matter? International Review of Financial Analysis, 55, 170–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2017.11.002

- Zaman Groff, M., Slapničar, S., & Štumberger, N. (2015). The influence of professional qualification on customer perceptions of accounting services quality and retention decisions. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 16(4), 753–768. https://doi.org/10.3846/16111699.2013.858076