?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

In this article, we examine the possible effects of acquisition through a Purchase and assumption agreement (P&A) as a resolution approach by the central bank of Ghana on the performance of the acquiring bank post-acquisition. By assessing the execution of the first P&A agreement, we contribute to the dearth of literature on the impact of M&As on bank performance in a developing context. We use secondary data from the Ghana Stock Exchange and the acquirer’s financial reports from 2015 to 2019 to assess the likely performance changes. We employ event study methodology and ratio analysis to determine the impact. We observe that while depositor funds were saved and the acquirer succeeded in widening their asset base through the acquisition, their efficiency levels during the assessed period did not improve. Our findings help explain the effects of such M&As through P&As on bank performance to assist investors and management in decision-making. It further accentuates the importance of adequate preparations before embarking on any sort of P&A agreement.

1. Introduction

The banking sector in every economy cannot be disregarded, as bank roles are critical to developing any well-established financial system. Banks serve as mediums through which investments are made, businesses financed, and savings habits encouraged and maintained among persons in a state. Generally, countries strategize and implement mechanisms to ensure their banking sectors continually thrive, and Ghana has not been expunged from this initiative. Within the last five years, the Ghanaian banking sector experienced significant restructuring believed to shape the economy in the long run. First, these spanned from revoking banking licenses to increasing the minimum capital requirements for commercial banks to stabilize and prevent future jeopardy in the sector.

On the other hand, as a means for businesses to expand and engage in a strategic approach that could lead to enhanced bank performance because of technology, expertise and other significant resource transfer, some Mergers and Acquisitions (M&As) occurred during the period. These M&As were encouraged as part of the restructuring and strengthening process to support some indigenous banks to meet capital requirements. In contrast, the government bailed out a few others through inventions from the central bank of Ghana. For instance, five indigenous banks merged to form one commercial bank to provide citizens with financial services. Alternatively, the central bank-Bank of Ghana (BOG), bailed out two defunct banks (Capital Bank and UT bank) by supervising an acquisition via a Purchase and Assumption agreement in the last quarter of 2017.

Given the potential benefits of M&As, it is not startling that M&A activities have multiplied in the global banking industry in recent years (Aljadani & Toumi, Citation2019; Carletti et al., Citation2020; Du & Sim, Citation2016; Varmaz & Laibner, Citation2016). Amid the increments, evidence of its impact on bank performance is diverse and somewhat linked to different banking industry regulations in many countries. That notwithstanding, happenings unique to the Ghanaian setting were explored because they seem to be a crucial addition to the M&A literature by investigating its effects on the acquirer’s performance. It is noteworthy that in similar extant studies on bank bailouts, the BOG bailed out the defunct banks to prevent them from entirely collapsing aside from the anticipated risks that may have erupted. Previous studies deem bank bailouts a necessary mechanism for economies that have their banking sectors contributing significantly to their growth (Gerhardt & Vennet, Citation2017; Goldsmith-Pinkham & Yorulmazer, Citation2010; Grossman & Woll, Citation2014). Most importantly, bailouts lessen the plausible losses depositors bear during a crisis.

With the responsibility to supervise and ensure that financial matters are at bay and depositor funds are safely secured, BOG implemented an acquisition through a P&A agreement because they deemed it the most efficient and less costly mechanism that could save the banking industry from future backlashes. In essence, the performance of the two defunct banks before the intervention deteriorated amid poor corporate governance issues, and BOG’s approach sought to stabilize the industry and calm stakeholders. Consequently, the P&A agreement mandated the acquirer, Ghana Commercial Bank (the largest indigenous bank), to assume some assets and liabilities of the failing banks. At the same time, the receiver appointed as part of the process ensures that the liabilities recouped are paid to stakeholders based on priority claims.

Amid the happenings in the sector, the present study specifically aims to evaluate the impact of the M&A on the acquirers’ performance post-acquisition. By assessing the bailout by the resolution authority in Ghana (BOG) via a P&A agreement, we highlight the importance and uniqueness of the case and seek to contribute to the bank M&A literature, especially in the developing economy discourse by ascertaining the impact of such an agreement on the acquirer in the quest to savor a potential banking crisis. We contribute to the extant literature by being the first to consider the country’s engagement in a P&A agreement, analyzing its nitty-gritty and its associated requirements. Further, by employing event study methodology and other financial analysis, we report the findings and make needed recommendations. Generally, assessing the underlying assumptions of the acquisition and the impact on the acquirer’s performance would inform stakeholders and regulatory parties about the benefits of the acquisition through a P&A agreement to stakeholders and the banking sector.

The study’s results showed that whereas depositors’ funds were saved and the sector stabilized, the acquirer and its shareholders have not entirely benefited from this acquisition based on the two-year post-acquisition analysis. Whereas future performance looks promising and shows that the acquirer may be able to withstand all the acquisition integrations and restructuring, the analyses of the study’s findings would aid in policy recommendations for banks that might have future strategic plans to undertake future P&A agreements. The subsequent sections of the study are as follows: a theoretical and an empirical literature review on bank M&As, bank bailouts, P&A agreements and the contest of the case. This is followed by the method and analysis employed for the study, the discussion of results and a conclusion.

2. Literature review

2.1. Theoretical review

M&As do not just take place because of their exquisiteness. Essentially, they are always geared toward anticipated business opportunities and benefits (Cheng & Yang, Citation2017). Whereas various theories underpin the rationale for M&As in the corporate setting (De Jong & Fliers, Citation2020; Leepsa & Mishra, Citation2016; Reddy, Citation2014; Weitzel & McCarthy, Citation2011), the efficiency theory is discussed as the theoretical underpinning of the study.

The efficiency theory views M&As as processes or events planned and completed to achieve synergies (Trautwein, Citation1990). Sharma & Ho (Citation2002) consider efficiency theory the same as synergy theory since they both argue that efficiency results from synergy creation. Similarly, Leepsa & Mishra (Citation2016) link efficiency theory to synergy creation, justifying that social and private gains are attained through efficient business operations between organizations involved. In order to better appreciate and establish the link between synergy and efficiency, synergy is defined as the increment in the value of a mutual entity likened to the worth of the autonomous organizations involved (Eschen & Bresser, Citation2005). Moreover, overall synergy is made up of financial synergy, operational synergy and management synergy (Bradley et al., Citation1983; Uddin & Boateng, Citation2009).

2.2. Empirical review

2.2.1. Bank M&As and bailouts

Bank M&As date far back to the nineteenth century, when most bank M&As were attributed to financial and technical non-intervention (Berger et al., Citation1999). Goddard et al. (Citation2012) posit that bank M&As are usually boosted by government policy initiatives and interventions to strengthen the banking industry in emerging markets. These policy initiatives result in a change in ownership, control of resources and the ideology that merged entities and acquirers of other entities can attain synergies in organizational operations that would, in the long run, contribute to economic growth.

In a Malaysian-based study by Sufian et al. (Citation2012) assessing the impact of forced M&As on banks’ efficiency, there were no significant improvements in the banks’ efficiency post-M&A. Du & Sim (Citation2016) similarly found no significant improvements in banks’ efficiency levels in the capacity as acquirers, although the efficiency levels of target banks seemed to have enhanced post-M&A. Rezitis (Citation2008) reported a negative relationship between bank M&As and total efficiency. Specifically, Rezitis (Citation2008) discovered that the banks’ technical efficiency decreased in the merging period due to the loss of economies of scale and other synergic motives the M&A sought to achieve. Jagtiani et al.’s (Citation2016) results differed as they indicated that M&As between large and small banks enrich the banking system’s general security and accuracy in a country. Shirasu (Citation2018) studied the long-term effects of bank M&As in the Asia-Pacific region. In contrast, they found that while there are contributions to growing banks’ loan capacity and ensuring capital adequacy, profits are not attained due to the high rate of non-performing loans in the long run.

Most bank M&A research has yielded mixed results in different jurisdictions with a large representation from more developed markets (Carletti et al., Citation2020; Nnadi & Tanna, Citation2014; Shetty et al., Citation2019; Varmaz & Laibner, Citation2016) and a few in the African region as a developing context (Liou & Rao-Nicholson, Citation2019; Wanke et al., Citation2017; Yeboah & Asirifi, Citation2016). Musah et al. (Citation2009) posit that since most Egyptian banks failed to show significant improvements in their performance post-M&A, M&As do not have a precise consequence on the profitability and efficiency of banks. Oduro & Agyei (Citation2013) discovered that M&As had a significant adverse effect on the profitability of most firms on the Ghana Stock Exchange. Liou & Rao-Nicholson (Citation2019) subsequently reported that South African multinational corporations that changed the corporate name of their acquired subsidiaries had lower post-acquisition returns on assets than South African MNCs that did not.

Amid the inconsistencies in previous studies, bank bailout interventions aided most commercial banks and prevented the collapse of banking sectors in countries, especially during the 2008 financial crisis (Carbó-Valverde et al., Citation2020; Grossman & Woll, Citation2014; King, Citation2015; Norden et al., Citation2020). Bailouts are a type of state mediation into an economy with significant redistributive impacts seeking to help weakened sectors prevent economic downturns. When enterprises and firms depend on the funds generated and provided by most banks in a country, the state or the government intervenes in restoring and creating a balance to keep their economies persistent (Grossman & Woll, Citation2014). Keister & Narasiman (Citation2016) opine that bailouts mitigate the plausible losses depositors must bear during a crisis. It helps smoothen out depositors’ consumption and prevents panic withdrawals by keeping their money in the financial system. King (Citation2015) finds that where states are utterly dependent on banks, bailouts are substantial but, at the same time, disciplinary in nature. Norden et al. (Citation2020) ascertain that bailouts readjust banking lending and trade credit provision to customers and aid in redistributing trade credit.

2.2.2. Purchase and Assumption agreements (P&A)

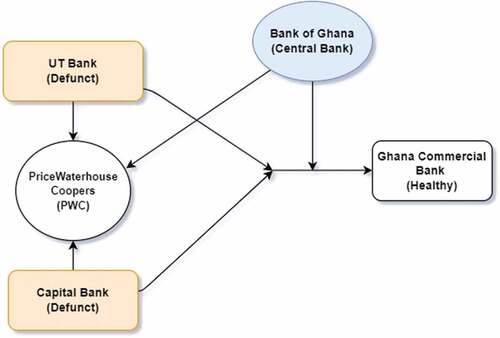

One of the most effective methods for finding solutions to troubled banks’ issues is P&A agreements (McGuire, Citation2012). A purchase and assumption agreement is a resolution tool that consents to transfer a distressed bank’s operations to another considered healthy. This procedure encompasses the cancellation or withdrawal of the defunct bank’s license, the termination of the owner’s rights in the bank, the supposition of the defunct bank’s deposits and good assets, and the takeover or acquisition of the bank’s defaulting assets by the resolution authority. The process prevents regulators from going through the complex administrative process of closing a bank and paying out all depositors’ deposits. Instead, all depositor funds are duly transferred to the healthy bank and depositors are granted access to their funds with no delay. GCB’s acquisition of the defunct banks relates more to the Loss Share P&A agreement.Footnote1 The Loss Share P&A agreement is when the acquirer and the resolution authority agree to share the future losses that accrue on a defined set of assets. This aids in limiting the risk involved in the acquisition and helps attract bidders to purchase the bank’s failed assets. Figure illustrates the parties that were involved in the P&A agreement.

3. Contest of case

Ghana is a developing country in West Africa, where business expansions and an improved financial system play a massive role in enhancing national development. The financial sector experienced major setbacks from a banking crisis that resulted in the closure of seven licensed banks between 2017 and 2018. Amid the pitfalls in the banking system, the central bank implemented several measures, including supervising M&As to restore and strengthen the system. Upon reviewing UT and Capital bank’s situation, BOG approved a purchase and assumption agreement that allowed Ghana Commercial Bank to acquire the two banks. The acquirer is a public bank (GCB) that the Government of Ghana significantly owns; the targets comprise a publicly listed bank on the GSE before the acquisition (UT Bank) and a private bank (Capital Bank).

The M&A between GCB and two defunct banks: UT Bank and Capital Bank, was an exception since the seizure circumstances mandated the central bank to intervene to prevent potential destabilization of the banking industry. Before the P&A agreement, there were interventions and liquidity support from BOG. Nevertheless, Capital and UT banks’ performance kept deteriorating, calling for a much more effective strategic approach from the BOG since the going concern concept could no longer hold for the banks. Tables show the downward trend in UT Bank and Capital Bank’s performance before the agreement.

Table 1. Ratio analysis of UT bank

Table 2. Ratio analysis of capital bank

On August 14th, 2017, BOG announced that the two defunct banks’ licenses had been revoked and to save depositors’ funds, GCB won the P&A agreement. In an attempt to clarify what BOG meant by the takeover of UT and Capital bank by GCB, BOG published a document answering all frequently asked questions from the public. The document stated that:

“The licenses of UT Bank and Capital Bank have been revoked, while the Bank of Ghana has approved a Purchase and Assumption agreement, allowing GCB Bank to take over all deposit liabilities and selected assets of both UT Bank and Capital Bank. These actions are in line with the provisions of section 123 of the Banks and Specialized Deposit-Taking Institutions (SDIs) Act, 2016 (Act 930)” (FAQ, Bank of Ghana, Citation2017)

4. Research methodology

Quantitative analyses using event study methodology and ratio analyses were employed to ascertain this case study’s objectives. Secondary data was gathered from the banks’ website, the GSE and other stakeholder engagements to determine the acquisition’s influence on GCB’s performance post-acquisition.

4.1. Event study and event analysis procedure

An event study is adapted to assess an event’s impact on a company’s operations or performance, such as the stock returns. As Gyamfi (Citation2018) concludes, the GSE is not predictable, and assessments based on the market indexes prove that the market passes the hurdle of efficiency in the weak form, event study methodology was employed. This is because the event will likely impact the market as it was unanticipated and provided the market with new information since the P&A agreement was the first of its kind in Ghana. The daily market trends of GCB’s shares from 2016 to 2017 and the market summary data were used. The daily shares and Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) provided the share price of GCB’s stocks, while the market summary included data on the financial sector’s market index, the Ghana Stock Market Financial Sector Index (GSE-FSI). This index has its constituents as listed stocks from the financial industry, including banking and insurance sector stocks.

The estimation window was from T-240 days to T-41 days before the event window, where the normal returns on GCB’s shares were calculated. This results in the observation of 200 days to ensure that the coefficient estimates remain unbiased. Mackinlay (Citation1997) postulates that the main event’s time should be excluded from the estimation window. The main event is set at time T, and the event window is between T-10 and T +10 to help determine the effects of the event on returns. McWilliams & Siegel (Citation1997) assert that in the circumstances like acquisitions, information about its nature and the evaluation of targets usually gets revealed after a long period. With the uncertainties surrounding what a P&A agreement constitutes and what investors stand to gain or lose, investors could reevaluate their initial assumptions about any future earnings the announcement could yield on the market. Thus, the event period adequately depicted future trends in investor expectations while the event remained free from any confounding events on the GSE.

The market model, which leads to enhanced detection of events’ effect in assessing abnormal returns, was adapted in the study. The estimation of the market model is, therefore, stated as follows:

Where is the expected return of the stock i on a given day t,

and

are the model’s intercept and slope, respectively,

is the return of the market of the GSE-FSI on the same given day,

is the error term with the zero mean disturbance term and a constant variance

= σ2. The model’s parameters are estimated using the ordinary least squares (OLS) method over 240 days as the estimation window and the event window starting 40 days before the announcement date. After which, the abnormal returns of the market were calculated. This was achieved by deducting the expected return from the stock’s actual return in consideration during the event window. Abnormal returns were calculated using the formula below:

Where is the abnormal return,

represents the actual returns of stock i in time t,

is the expected return of stock i within a period t. The Cumulative Abnormal Returns (CAR) was hereafter calculated by summing the abnormal returns for the stock i over a period. The alpha and Beta values were calculated using the returns on GCB’s shares and the market index returns (GSE-FSI) within the estimation window. T-statistics were also calculated to ascertain the significance of the abnormal returns and the CAR. Table presents the computation of GCB’s Expected Returns (ER), Normal returns (NR), Abnormal Returns (AR), t-statistic, CAR and the alpha and beta values.

Table 3. Results of GCB’s main event

5. Empirical results and discussion

In Table , GCB’s alpha, which is the intercept, was very close to zero. This signified that firms could not earn a significant alpha in any given period in equilibrium, which in this analysis spans 200 days before the event window. The beta depicted the sensitivity of GCB’s returns to overall stock market trends. The beta of 0.4029 showed low responsiveness and sensitivity to general price and market movements on the GSE. The abnormal returns represented the market returns within the estimated duration above the market index (GSE-FSI) returns. AR and CAR were used to evaluate the performance of GCB’s stocks against GSE’s market performance.

Within the Event window, GCB experienced a positive abnormal return in t-5 and negative abnormal returns from t-4 to t-2 until there was a relatively small positive return in T-1 and T +1 the day after the acquisition announcement. The t-statistics of AR in the event window from t-10 to t +10 in Table show that the returns were insignificant; thus, the acquisition announcement did not significantly affect the AR on GCB’s stock. CAR is subsequently determined by summing the abnormal returns of the periods surrounding the event. Cumulatively, it shows whether market participants enjoyed any excess returns or unanticipated profits within a period. The CAR for the period was negative for the entire event window of T-10 to T +10, as seen in Figure .

The t-statistic for the CAR within some event windows was further calculated. As shown in Table , whereas CAR for pre-event and post-event in the assessed windows were all negative, among the eight (8) event windows, t-tests were significant at a 1% significant level for three of event windows that is, windows [(−5,20), (−10,20), (−20,20)].

Table 4. Mean equality for CAR in event windows

5.1. Assessing CAR results

As illustrated in Figure , CAR was negative over the entire event and post-event window period (−10, +10). Findings in Table also depict that CAR became significant in an extended window beyond twenty-six days in the post-event window. GCB recorded a 22.17% share price loss by the end of the post-event window of T +40 days. While this signified that investors did not benefit from the acquisition announcement of UT and Capital bank, the study results suggest that the GSE did not respond well to the acquisition of the defunct banks by UT bank. The following reasons may have explained the negative trend in CAR after the acquisition announcement.

The nature of the acquisition and the P&A agreement contributed immensely to investors’ negative response and the resulting decline in share value. The acquisition through a P&A agreement happened to be the first in Ghana. Investors were oblivious to any positive outcomes that could arise amid the chaos it had created in the country post-announcement date. Investors were initially slow to react, considering the acquired banks’ poor performance, low returns on assets and equity and other performance measurements from their financial statements shown in Tables . When investors eventually reacted, their response was weak and negative. With the central bank significantly involved in the process, there were impending concerns about the whole process, irrespective of its role as the central bank.

Secondly, the adverse reaction could be attributed to the speculations surrounding the revocation of UT and Capital Bank licenses and the attribution of the abrupt revocation to the central bank’s negligence in performing its responsibilities. It may be argued that investors had slightly lost faith in the central bank’s capabilities during those times. Many stakeholders complained about how an asset quality review in 2015 showed the probability of such happenings, but issues were overlooked and not stringently handled until it almost jeopardized the banking industry in 2017. Additionally, during and after the event window, the market activity shows several block trades of GCB shares on the GSE that propelled high market activity. Subsequently, amid investors’ speculations and the market’s negative response, GCB’s share price began to retreat because its share supply was relatively higher than its demand. More investors were willing to sell their shares in GCB while demand for those shares was still low.

5.2. Robustness analyses

5.2.1. Ratio analyses

Table presents ratio computations in 2015 and 2016, representing the pre-acquisition period, while 2018 and 2019 represent the post-acquisition period. T-tests were conducted to determine the significance of ratio changes over the analysis period to establish a causal link between the acquisition impact and performance changes. In conducting a paired sample one-tailed t-test premised on the significant impact the acquisition had on their expenditure and system rationalization, the differences were assessed based on the assumption that post-acquisition performance is significantly lower than pre-acquisition performance.

Table 5. Ratio analyses of GCB

The debt-to-equity ratio determines a bank’s level of leverage to finance its operations through debt against equity. It shows the level of contribution in the bank’s operations between debtholders and equity holders. GCB’s trend from 2015 to 2019 depicts an increment in the debt-to-equity ratio, with a heightened focus in 2017 resulting from the P&A agreement. GCB’s debt-to-equity ratio increased in the post-assumption period, and these changes were significant as p-value<0.10 highlighting the impacts of the P&A agreement on the bank’s performance. While resorting to more debt financing can indicate enhanced growth strategies, it also means that future profits would be made with an increased risk of loss. Ideally, more debt financing results in higher ROEs if the extra debt introduced is less costly than the interest accruing. In GCB’s case, ROEs were significantly affected by the assumption of assets, and the additional debt burden also reduced the company’s profitability.

The leverage ratio assesses the bank’s core capital against its total assets. This was computed by dividing Tier I capital, made up of disclosed reserves and ordinary paid-up capital, by the total asset base. A higher ratio shows that the bank can withstand any financial shocks in business. Here, GCB’s leverage ratio was reduced by about 3.5% in 2017 because of the disproportionate increase in Tier 1 capital and total assets. While this raises concerns about GCB’s ability to withstand financial shocks, the post-assumption reduction was significant (P <0.10), asserting that the P&A agreement negatively affected the bank. Arguably, GCB’s ability to withstand future market shocks decreased.

The efficiency ratio examines profitability levels after generating enough revenue to cater for expenses. A higher efficiency ratio signifies that the bank spends more on average to generate income. In 2017, GCB recorded the highest efficiency ratio, vastly attributable to the acquisition, integration, and operational costs the bank bore to absorb the defunct banks’ assets and liabilities. Furthermore, while the reports in 2018 and 2019 showed an improvement in the bank’s efficiency ratio from 65% to 62%, this difference was not much. Table nonetheless depicts from the t-test p-value>0.10 that although the ratios illustrate the impact of the acquisition, the difference between pre and post-acquisition efficiency is not significant enough to opine that the bank was immensely affected by the assumption of assets and liabilities from the defunct banks.

With the added operating assets from the assumed banks and ROA of 3.39% in 2019, lower than ROA values in the pre-assumption period, the acquisition did not benefit the bank during the two-year post-acquisition period. As shown in Table , a p-value <0.10 depicts a significant reduction in these profitability values. ROE trends were similar to the ROA as 2015 recorded the highest ROE and 2017, the least because of the increase in shareholders’ equity and income reduction. Additionally, with a p-value<0.10, GCB’s ROE post-assumption had not improved much. It can be argued that shareholders’ capital had not been efficiently and effectively used post-assumption. Although post-acquisition saw growth in ROE, presupposing that the bank stands a chance of improving ROE and growing shareholder wealth in the future, the transition resulted in operating under capacity.

GCB’s cost-to-income ratio followed an increasing and decreasing pattern, especially in 2018 and 2019. This ratio heightened in the assumption year because of the increased operating costs from system rationalization, staffing etc. However, there were improvements in the subsequent years. Amid the increment and reductions in the ratio, p-value>0.10 suggests that the impact of the assumption that caused the increments was not too significant to pose a great effect on the bank’s performance.

On the other hand, while efficiency and cost-to-income ratio are marginally decreasing, GCB’s operational costs against operating income did not significantly reduce. The cost-to-income ratio of 59% was above the banking industry average of 51%. The board’s interventions to manage these costs may not have effectively yielded the most desired outcome or reduction. It could be accurate to predict that GCB could have performed much better than it did two years post-acquisition had it not acquired defunct UT and Capital Banks. This shows the challenge GCB had to deal with to maintain low operational costs after the increment in 2017.

5.2.2. Performance evaluation using industry averages

With initial findings showing that post-acquisition performance is significantly lower than pre-acquisition performance based on ratio analyses in Table , Industrial averages of profitability indicators were also used to analyze GCB’s performance. As of the 2019 year-end, the banks operating or issued with universal banking licenses were twenty-four, and these industrial averages include the performance assessments of these banks. This performance analysis based on industrial averages is premised on the fact that some competing banks tend to perform above the industry averages. Table shows the industry and GCB’s cost-to-income ratio, ROE and ROA, and the differences between the profitability indicators.

Table 6. Industry-level analysis

It is evident from Table that GCB’s performance deteriorated in 2018 after the P&A agreement in 2017. Firm year differences between 2018 and 2016 depict that ROE and ROA levels dropped while the cost-to-income ratio increased by 5.75%. ROE and ROA for 2018 and 2016 also show that GCB shareholder value after the P&A agreement decreased compared to pre-acquisition. Industry and firm differences also demonstrate that GCB’s cost-to-income ratio is above the industry average, signifying that their operational costs have widened.

Table 7. Tobin’s Q ratio of GCB from 2015 to 2019

5.2.3. Tobins’Q

Fundamentally, Tobin’s Q is a performance measure that reflects a company’s value to shareholders (Aksoy et al., Citation2020. In line with Amit et al. (Citation1989), Tobin’s Q for GCB in Table was measured by the market value of Equity (stock price multiplied by the total number of shares outstanding) plus the book value of debt divided by the book value of total assets for the period. Tobin’s q from 2015 to 2019 shows that GCB was undervalued, with a ratio of 0.98 in 2019. The bank was initially overvalued in 2015, signifying that although its asset base had not yet grown as it has now, it was worth more than its assets’ replacement cost.

Tobin’s q’s surge in 2017 can be backed by the defunct state of two banks, reflecting possible growth in GCB’s worth during the acquisition. Though the assumption of assets and liabilities improved the bank’s worth, because of operational challenges that arose from the integration, there was a reduction in Tobin’s Q in 2018 and 2019. This resulted from the reduced market value of their shares and the negative response after the P&A agreement.

6. Conclusion, recommendations and limitations

Underpinned by the efficiency theory, the study sought to assess the impact of an acquisition that resulted in Ghana’s first P&A agreement on the performance of GCB, the acquirer. For performance assessments, event study methodology and ratio analysis were employed to determine the acquisition’s effect on GCB’s operations. From the analyses, it is derivative that this acquisition phenomenon through a P&A agreement did not provide sufficient benefits to the shareholders of GCB based on the two-year pre and post-acquisition performance assessments.

Apart from the weak reactions from market participants, the ratio analyses also depicted that post-acquisition performance was significantly lower than pre-acquisition performance. Additionally, with the added asset base, GCB seemed to be operating under capacity judging from its ROE and ROA growth. Operational expenses absorbed had also not been reduced as their cost-to-income ratio was above the industrial average in the banking industry. Reductions in performance were supported by the market value analysis showing a decreasing value in the bank’s worth. Overall, it can be contended that while there were expansions in branch coverage and increment in asset base, there was less improvement in efficiency levels.

The turnout from this P&A agreement implies that several approaches and strategies must be implemented, and strict adherence must be ensured by the controlling entities of financial matters, such as the central bank in countries that seek to employ such a bailout strategy. This is crucial and necessary so that effects are not shifted to the acquirer at the expense of the industry, as this may still harm the industry if the acquirer is incapable of bearing future associated risks, irrespective of their pre-acquisition condition.

As GCB’s post-acquisition performance depicted that the acquisition challenges had not been completely wiped out, it is plausible that they could have performed better without the acquisition. We recommend that when risk assessments are conducted, findings are acted upon with immediate effects so failing banks are identified early enough. In order to ensure the events surrounding the withdrawal of UT and Capital bank licenses do not repeat themselves in Ghana and countries beyond, good corporate governance practices must be strictly adhered to by the board of directors of banks. Strict adherence extends to complying with all regulations by the industry’s governing bodies since the revocation of licenses and the P&A agreement were attributed to poor corporate governance practices. Most importantly, with the finding that the acquisition even impacted the largest indigenous bank in the country, it could be a signal to the other banks that only healthy banks with the capacity to strategically recover from the impact of acquisitions of such nature should partake in P&A agreements. While the opportunities it might create for an acquiring bank seem high, banks equally have a role in ensuring that they do not end up being acquired through another P&A agreement by another bank because of operational mismanagement from the added banks. For GCB, they achieved its motives for assuming the banks through internal expansions and growth. Presently, it has the largest branch coverage in the country and leads with the largest operating assets among the banks, with a majority of local ownership.

Amid the outlined contributions, the study’s main limitation centered on the period of assessment and the sample size employed in performance assessments. The date of the acquisition restricted the timespan for analyzing its impact on performance. As the acquisition occurred in 2017, the only available years for review were two years pre-and post-acquisition at the time of this study. Although this might not suffice as a generalized basis to assess the performance trend, this has been adopted in several extant studies. Furthermore, since the study analyzed one case, it may not be sufficient to opine that acquisitions positively or negatively impact banks’ organizational performance in Ghana though their two-year pre-acquisition performance was higher than their post-acquisition performance. Nonetheless, because acquisitions involve complex integration mechanisms and transaction costs, future studies over a long period could present a broader performance trend post-acquisition.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nana Adwoa Anokye Effah

Nana Adwoa Anokye Effah is a student at the School of Accounting, Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, Wuhan, China. Her research interests include behavioral issues in accounting, bibliometric analysis, corporate governance, CSR and sustainability reporting.

Notes

1. See, McGuire (Citation2012) for notes on the types of P&A agreements.

2. The Resolution authority overseas the entire agreement process and ensures that assets and liabilities assumed are transferred to the Healthy bank. The Receiver, who is appointed by the resolution authority is responsible for managing the assets of the two banks not taken over by GCB Bank. They are also in charge of distributing proceeds to creditors according to the priority of claims in accordance with the Banks and SDIs Act, 2016 (Act 930).

References

- Aksoy, M., Yilmaz, M. K., Tatoglu, E., & Basar, M. (2020). Antecedents of corporate sustainability performance in Turkey: The effects of ownership structure and board attributes on non-financial companies. Journal of Cleaner Production, 276, 124284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124284

- Aljadani, A., & Toumi, H. (2019). Causal effect of mergers and acquisitions on EU bank productivity. Journal of Economic Structures, 8(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40008-019-0176-9

- Amit, R., Livnat, J., & Zarowin, P. (1989). A classification of mergers and acquisitions by motives: Analysis of market responses. Contemporary Accounting Research, 6(1), 143–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.1989.tb00750.x

- Bank of Ghana. (2017). GCB takes over UT bank and capital bank- frequently askedquestions (Issue August).

- Berger, A. N., Demsetz, R. S., & Strahan, P. E. (1999). The consolidation of the financial services industry: Causes, consequences, and implications for the future. Journal of Banking and Finance, 23(2–4), 135–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4266(98)00125-3

- Bradley, M., Desai, A., & Kim, E. H. (1983). The rationale behind interfirm tender offers. Information or synergy? Journal of Financial Economics, 11(1–4), 183–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(83)90010-7

- Carbó-Valverde, S., Cuadros-Solas, P. J., & Rodríguez-Fernández, F. (2020). Do bank bailouts have an impact on the underwriting business? Journal of Financial Stability, 49, 100756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2020.100756

- Carletti, E., Ongena, S., Siedlarek, J. P., & Spagnolo, G. (2020). The impacts of stricter merger legislation on bank mergers and acquisitions: Too-big-to-fail and competition. Journal of Financial Intermediation, February, 100859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2020.100859

- Cheng, C., & Yang, M. (2017). Enhancing performance of cross-border mergers and acquisitions in developed markets: The role of business ties and technological innovation capability. Journal of Business Research, 81(January), 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.08.019

- De Jong, A., & Fliers, P. T. (2020). Predicting takeover targets: Long-run evidence from the Netherlands. De Economist, 168(3), 343–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-020-09364-z

- Du, K., & Sim, N. (2016). Mergers, acquisitions, and bank efficiency: Cross-country evidence from emerging markets. Research in International Business and Finance, 36, 499–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2015.10.005

- Eschen, E., & Bresser, R. K. F. (2005). Closing resource gaps: Toward a resource-based theory of advantageous mergers and acquisitions. European Management Review, 2(3), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.emr.1500039

- Gerhardt, M., & Vennet, R. V. (2017). Bank bailouts in Europe and bank performance. Finance Research Letters, 22, 74–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2016.12.028

- Goddard, J., Molyneu, P., & Zhou, T. (2012). Bank mergers and acquisitions in emerging markets: Evidence from Asia and Latin America. European Journal of Finance, 18(5), 419–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/1351847X.2011.601668

- Goldsmith-Pinkham, P., & Yorulmazer, T. (2010). Liquidity, bank runs, and bailouts: Spillover effects during the Northern Rock episode. Journal of Financial Services Research, 37(2–3), 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-009-0079-2

- Grossman, E., & Woll, C. (2014). Saving the Banks: The political economy of bailouts. Comparative Political Studies, 47(4), 574–600. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013488540

- Gyamfi, E. N. (2018). Adaptive market hypothesis: Evidence from the Ghanaian stock market adaptive market hypothesis: Evidence from the Ghanaian. Journal of African Business, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2018.1392838

- Jagtiani, J., Kotliar, I., & Maingi, R. Q. (2016). Community bank mergers and their impact on small business lending. Journal of Financial Stability, 27, 106–121. Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2016.10.005

- Keister, T., & Narasiman, V. (2016). Expectations vs. fundamentals-driven bank runs: When should bailouts be permitted? Review of Economic Dynamics, 21(2008), 89–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.red.2015.03.004

- King, M. R. (2015). Political bargaining and multinational bank bailouts. Journal of International Business Studies, 46(2), 206–222. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2014.47

- Leepsa, N. M., & Mishra, C. S. (2016). Theory and practice of mergers and acquisitions: Empirical evidence from Indian cases. IIMS Journal of Management Science, 7(2), 179. https://doi.org/10.5958/0976-173x.2016.00016.6

- Liou, R. S., & Rao-Nicholson, R. (2019). Corporate name change: Investigating South African multinational corporations’ postacquisition performance. Thunderbird International Business Review, 61(6), 929–941. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.22086

- Mackinlay, A. C. (1997). Event studies in economics and finance. Source Journal of Economic Literature Journal of Economic Literature, 35(1), 13–39. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2729691%5Cnhttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp%5Cnhttp://www.jstor.org

- McGuire, C. L. (2012). Simple tools to assist in the resolution of troubled banks. The World Bank, 1, 1–135. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/12342

- McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (1997). Event studies in management research: Theoretical and empirical issues. The Academy of Management Journal, 40(3), 626–657. https://doi.org/10.5465/257056

- Musah, A., Abdulai, M., & Baffour, H. (2009). The effect of mergers and acquisitions on bank performance in Egypt. Journal of Management Technology, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.20448/journal.501.2020.71.36.45

- Nnadi, M. A., & Tanna, S. (2014). Post-acquisition profitability of banks: A comparison of domestic and cross-border acquisitions in the European Union. Global Business and Economics Review, 16(3), 310–331. https://doi.org/10.1504/GBER.2014.063075

- Norden, L., Udell, G. F., & Wang, T. (2020). Do bank bailouts affect the provision of trade credit? Journal of Corporate Finance, 60, 101522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2019.101522

- Oduro, M. I., & Agyei, S. K. (2013). Mergers & acquisition and firm performance: Evidence from the Ghana stock exchange. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 4(7), 99–108. https://doi.org/10.7176/RJFA

- Reddy, K. S. (2014). Extant reviews on entry-mode/internationalization, mergers & acquisitions, and diversification: Understanding theories and establishing interdisciplinary research. Pacific Science Review, 16(4), 250–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscr.2015.04.003

- Rezitis, A. N. (2008). Efficiency and productivity effects of bank mergers: Evidence from the Greek banking industry. Economic Modelling, 25(2), 236–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2007.04.013

- Sharma, D. S., & Ho, J. (2002). The impact of acquisitions on operating performance: Some Australian evidence. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 29(1–2), 155–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5957.00428

- Shetty, A., Manley, J., & Kyaw, N. (2019). The impact of exchange rate movements on mergers and acquisitions FDI. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 52–53(100594). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mulfin.2019.100594

- Shirasu, Y. (2018). Long-term strategic effects of mergers and acquisitions in Asia-Pacific banks. Finance Research Letters, 24, 199–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2017.07.003

- Sufian, F., Muhamad, J., Bany-Ariffin, A. N., Yahya, M. H., & Kamarudin, F. (2012). Assessing the effect of mergers and acquisitions on revenue efficiency: Evidence from Malaysian banking sector. Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective, 16(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/097226291201600101

- Trautwein, F. (1990). Merger motives and merger prescriptions. Strategic Management Journal, 11(4), 283–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250110404

- Uddin, M., & Boateng, A. (2009). An analysis of short-run performance of cross-border mergers and acquisitions: Evidence from the UK acquiring firms. Review of Accounting and Finance, 8(4), 431–453. https://doi.org/10.1108/14757700911006967

- Varmaz, A., & Laibner, J. (2016). Announced versus canceled bank mergers and acquisitions: Evidence from the European banking industry. The Journal of Risk Finance, 17(5), 510–544. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRF-05-2016-0069

- Wanke, P., Maredza, A., & Gupta, R. (2017). Merger and acquisitions in South African banking: A network DEA model. Research in International Business and Finance, 41, 362–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2017.04.055

- Weitzel, U., & McCarthy, K. J. (2011). Theory and evidence on mergers and acquisitions by small and medium enterprises. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 14(2–3), 248–275. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEIM.2011.041734

- Yeboah, J., & Asirifi, K. E. (2016). Mergers and acquisitions on operational cost efficiency of banks in Ghana: A case of ecobank and access bank. International Journal of Business and Management, 11(6), 241. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v11n6p241