Abstract

Aim of the study is to examine the impact of employee empowerment and ICT support on the employees’ work life quality with the mediating effect of the hospitality firms’ trust climate. Operational employees (n = 123) of the three star hotels of Bangladesh participated in the study. A partial least squares structural equation model (PLSSEM) was utilized in order to test a hypothesized model. Data were validated by a measurement model and hypotheses were tested by a structural equation model using the SmartPLS 3.0 software. Results indicate that climate of trust partially mediates the relationship between employee empowerment and quality of work life, and ICT support and quality of work life. The study also found that employee empowerment (β = 0.299), ICT support (β = 0.326), and climate of trust (β = 0.192) have strong effects (p < .05) on employees’ quality of work life with a variance (R2) of 42.1%, while employee empowerment (β = 0.358) and ICT support (β = 0.393) have significant influences (p < .05) on firm’s climate of trust with a variance (R2) of 38.1%. These findings may be utilized cautiously since the study was undertaken on the operational employees of the three star hotels in Bangladesh. This study provides new insights by defining the role of the hospitality firms in enriching the operators’ life at work and the strategies that the hospitality managers can formulate to empower their staff, allow them effective technological support, and build an atmosphere with mutual trust for attaining positive employee focused outcomes.

1. Introduction

Human resources are directly responsible for the production and delivery of services in the majority of service industries, and human actions are linked to consumer consumption experiences. For improving the service quality, employees spend a great deal of time (Lee et al., Citation2016), accordingly, they devote a significant portion of their lives to their jobs (Akman & Akman, Citation2017). Besides, they plan their personal/family time based on their job demands. These phenomena influence the early practitioners to make the work settings more humane and importantly, to enrich the operators’ work life. Because a healthy work life stimulates employee attitude and performance, which also have an enormous contribution to corporate success (Adisa & Gbadamosi, Citation2018; Sari et al., Citation2019). Therefore, scholars talk about the “quality of work life” of people to benefit their overall life through fulfilling their needs and enriching their working conditions (Sirgy et al., Citation2001).

It has been reported that service operators in the hospitality industry do not enjoy their work life (Akter et al., Citation2021; Gordon et al., Citation2019). In recent years, the industry has become one of the world’s largest and most rapidly expanding industries (Alshaabani et al., Citation2020). It contributes to the development of many economies, and in some nations, it acts as a major source of foreign currency earnings (Matthew et al., Citation2021; Sheehan et al., Citation2018). In Bangladesh, it acts as one of the major economic drivers (GOB, Citation2019) and is one of the nine largest employment-generating sectors (GOB, Citation2021). Due to the expansion of international business, tourism, and the hosting of international sports and events, the inflow of foreign visitors has also increased significantly. However, the hospitality industry of Bangladesh encounters human resource-related problems, e.g., employee unhappiness with their work and working life (Akter et al., Citation2021; Alshaabani et al., Citation2020; Rahman et al., Citation2019).

One of the most difficult challenges for hospitality employees is providing prompt responses to customers/guests due to poor organizational arrangements, like a lack of authority to make work-related decisions, limited access to information, a lack of control on the job, and vague and meaningless responsibility (Alhozi et al., Citation2021, Citation2021; Rubel et al., Citation2021). If they are given adequate power and authority, resources, and liberty, they can solve the job-related issues by investing their creative ideas and insights for business development (Abuhashesh et al., Citation2019). Scholars claimed that for the accomplishment of a hospitality firm’s objectives (guest satisfaction, sustainability, and profitability), empowering its employees is a basic and essential organizational function (Saban et al., Citation2020; Simsek, Citation2020). When a firm empowers its employees, it needs to provide technological support for accessing (job-related) information (Peterson & Zimmerman, Citation2004). From this perspective, Bangladesh is still in the early stages of adopting the revolutionary benefits of modern ICTs in the hospitality industry, despite many other developing economies already having done so (Avi & Sardar, Citation2021; Rahman & Hassan, Citation2021; Tripura & Avi, Citation2021). The hospitality firms are not yet technologically equipped to cope with the changes in hospitality operations globally. By applying modern ICTs, they can improve their performance in marketing products and services, assessing customer demands, monitoring customers/tourists/guests, disseminating data and information, building employee capacity, and so on (Avi & Sardar, Citation2021; Rahman & Hassan, Citation2021).

Researchers accentuated empowerment to understand an individual’s satisfaction with his/her work life (Nayak et al., Citation2018; Nursalam et al., Citation2018). Empowered employees are better prepared to meet challenges, as they have control over their jobs, get support from the team members, and are recognized for their accomplishments. It is one of the organizational approaches by which a firm can contribute to increasing the professional role development of the individuals. In addition, empowerment plays a crucial role in the organization for enriching the qualities of people’s work lives (Nayak et al., Citation2018; Nursalam et al., Citation2018). Further, a firm can support its workforce by providing the appropriate technologies to communicate knowledge and information inside and/or outside the team on time. This support is necessary for making an individual’s (work and social) life happy and peaceful as well as for improving his/her well-being (Demerouti et al., Citation2001). Thus, a firm’s ICT support benefits the working procedures that ultimately impact quality of employees’ work life (Hannif et al., Citation2014).

Further, numerous local and international studies found organizational trust, mutual trust, trust in leaders, and climate of trust as the mediating variables between organizational factors and employee-related outcomes in the hospitality industry (Akter et al., Citation2021; Oh, Citation2022; Ozturk & Karatepe, Citation2019; Qiu et al., Citation2019). In this industry, the absence of trust among organizational members restricts mutual respect, knowledge sharing, open communication, collaboration, and creative performance. Instead, a high level of shared and mutual trust can help both managers and employees achieve firms’ success in a shorter time and more effectively. Besides, during times of uncertainty, natural disasters, pandemics (e.g., COVID-19), and any other national or global economic and/or political unrest, shared trust would even help all the stakeholders of the hotels (Guzzo et al., Citation2021). Considering the nature of hospitality jobs, researchers claimed that no variable can affect an individual’s attitude and behavior as much as trust does (Tan & Tan, Citation2000). Undoubtedly, if mutual and shared trust does not exist, organizational practices will fail to influence hospitality employee perceptions, i.e., employees will not be properly empowered, and ICT will not assist the people.

In addition to employees’ QWL, empowerment and ICT support have implications for building shared and mutual trust within the organization. Empowerment, generally, takes place only when managers can trust the employees. On the other hand, in the participative decision-making process, employees get more knowledge about other people (including managers) and the organization as a whole, which generates their trust in others (Haq et al., Citation2018; Laschinger et al., Citation2012). Similarly, a trust climate is created within an organization, when appropriate technologies are utilized for sharing the knowledge and information transparently, accurately, and timely (Bondarouk et al., Citation2017). These corporate actions, therefore, can cause greater interpersonal contacts, which reintroduces the concept of mutual trust (Gill & Sypher, Citation2010). Afterward, trust between employees and managers results in the improvement of employee happiness with their work life (Cascio, Citation1992; Shaw, Citation2005). Besides, mutual and shared trust has been observed as an important outcome in the empowered (Laschinger et al., Citation2012; Vanhala & Ahteela, Citation2011) and ICT-enabled work environment (Bala & Bhagwatwar, Citation2017; Bissola et al., Citation2014), while it also has been identified as a predictor of quality of work life (Akter et al., Citation2021; Al-Shalabi, Citation2019; L. Jiang & Probst, Citation2015). Therefore, this study proposes that the impact of firms’ empowerment practices and ICT supports on staffs’ work life can be mediated by the shared trust among the organizational members.

The corporate roles in empowering employees and applying ICT were emphasized separately in different studies. However, enough idea of how empowerment and ICT-enabled practices could jointly impact employees’ work life is not found yet. Besides, the knowledge is still lacking about the joint effects of empowerment and ICT to enhance people’s work life quality through building a trust climate of a team. These multiple organizational factors may have different (direct and indirect) effects on employees’ work life if they are taken together. Moreover, hospitality people’s work life issues are studied only by a few research, while the issue in the developing and under-developed country context is not much explored. In light of this, the goal of this study is to investigate the effect of empowerment and ICT support on an individual’s work life quality with the mediating effect of trust climate.

By addressing the identified research gaps and the corresponding goal, this study will explain how firms can utilize their technological and human efforts and contribute to the interests of the working people. Moreover, it can broaden the existing knowledge by elucidating the role of trust climate as an intermediate variable in the facilitation of QWL outcomes of employees. Therefore, this study offers an opportunity to find the paths for enhancing employees’ work life quality in the presence of the firm’s initiatives of empowerment and ICT facilities. For this, the study proposes a conceptual model that will contribute to the development of the theoretical and the practical framework of QWL.

2. Literature review

2.1. Quality of work life

Walton (Citation1973) for the first time pointed out the concept of “quality of work life” as the quality of human experience at the workplace. At that time, producers emphasized employer-employee relations as well as product quality, which were dependent on the organizational work environment for achieving a competitive position. Considering both the requirements, Walton (Citation1975) defined quality of work life as an organizational process of employing mechanisms, which allow employee participation in the organizational decisions relating to their work lives. Thus, the QWL program was primarily implemented to improve the work environment. Since then, it has garnered much attention in business society as well as in academia. Later, based on the empirical investigation, Sirgy et al. (Citation2001) defined QWL as “employee satisfaction with a variety of needs through resources, activities, and outcomes stemming from participation in the workplace”. They considered the impact of the workplace on employee satisfaction in their professional life, personal life, and overall life. Remarkably, both Walton (Citation1975) and Sirgy et al. (Citation2001) concentrated on the satisfaction of employee needs because an improved work life enriches an individual’s quality of overall life and a satisfied person can better contribute to organizational success.

However, Yousuf (Citation1996) referred to QWL as employee perceptions about every dimension of work, including economic rewards, benefits, security, working conditions, organizational and interpersonal relations, and their intrinsic measurement taken by the organization in order to humanize the work environment. Kwahar and Iyortsuun (Citation2018) defined QWL as a humanizing approach to a workplace in terms of job nature, physical work environment, social connections, compensation and benefits, managerial approaches, and employee relations. These researchers stressed the QWL for addressing the issues relating to organizational working conditions. Thus, researchers explained quality of work life from different perspectives, although industrial psychologists and management experts commonly explained QWL as “all about employee wellbeing”.

2.2. Employee empowerment

It is an organizational practice of building employee perceptions of having greater authority to influence a firm’s decisions (Peterson & Zimmerman, Citation2004; Zimmerman, Citation2000). Empowerment broadly embraces some matters, like an individual’s freedom to make decisions and take actions, a sense of control over a job, accountability in terms of work done, and responsibility for performance outcomes (Greasley et al., Citation2008). Consequently, s/he has control over the organizational success through his/her job (B.E. Hayes, Citation1994). Scholars categorized employee empowerment, as psychological empowerment: employee feelings of self-efficacy and experience of autonomy at the workplace; and structural empowerment: the delegation of authority along with the responsibility to the employees. A firm generates psychological empowerment in individuals through organizational initiatives, which is called structural empowerment (Zimmerman, Citation2000). When empowerment is fully deployed, greater possibilities are created for achieving corporate goals, since it facilitates organizational decisions by involving both employees and managers (Ardahaey & Nabilou, Citation2012).

2.3. ICT support

ICT produces interlinks between societies by supporting the entities through the access to knowledge and information. Information technology fundamentally facilitates organizational communication in the decision-making process (Majchrzak et al., Citation2005). The deployment of information technologies has consequences for the creation of the “global virtual team”, where people work together toward common goals, even though they live in different locations (Adamovic, Citation2017). Application of appropriate technologies ensures the promptness of the dissemination of information and removes the barriers posed by the users’ location. Thus, ICT has contributed to the quality and quantity of organizational performance (Arbabisarjou & Allameh, Citation2012), which aligns with the quality of life of people in general (Bonomi et al., Citation2019). Therefore, ICT support can be defined as the technological support in the organizational information and communication systems for transmitting knowledge and information accurately and timely and allowing individuals access to information so that they can use the information at anytime from anywhere to solve (job-related) problems (Drent & Meelissen, Citation2008; Majchrzak et al., Citation2005; Saleem et al., Citation2017). ICT-enabled working environments cause employee satisfaction, work-life balance, and employee wellbeing by enabling flexible working arrangements (Adisa & Gbadamosi, Citation2018; Demerouti et al., Citation2014; Heischman et al., Citation2019; Korunka & Hoonakker, Citation2014).

2.4. Climate of trust

Trust facilitates open communication and cooperation among people that improves work satisfaction and the values of life at work. Individuals believe that other organizational members will act positively (based on their roles, relationships, experiences, and interdependencies), and these beliefs create the significance of a trusting climate. This climate can be identified by the trustworthiness of people, where they want to depend on others (Akter et al., Citation2021; Alshaabani et al., Citation2020; Lin et al., Citation2016). When team members demonstrate reliability and behave consistently, a trust climate is developed (Alshaabani et al., Citation2020; L. Jiang & Probst, Citation2015). It comprises belief in others’ honesty and sincerity, mutual understanding, loyalty, information sharing, and open communication (Buvik & Rolfsen, Citation2015). In this climate, employees are found to be more knowledgeable, dynamic, and constructive (Blömeke et al., Citation2015). Thus, a trust climate strengthens cooperation among team members (Jiang et al., Citation2015), provides them with a feeling of security (Schulte et al., Citation2012), and makes people comfortable with their jobs (Ozturk & Karatepe, Citation2019). Besides, open communication and cooperation among the working people can cause the effective functioning of the organization (Farndale et al., Citation2011; Moye & Henkin, Citation2006).

2.5. Employee empowerment and quality of work life

Empowerment is a vital corporate practice to enrich the employee experience at work (Ardahaey & Nabilou, Citation2012) by humanizing the working environment and removing the barriers between employees and managers (Badawy et al., Citation2018; Nursalam et al., Citation2018). It builds self-efficacy in employees and decreases their emotional strain and occupational stress (Greasley et al., Citation2005). Researchers indicated empowerment as a predictor of employees’ QWL. For example, Nursalam et al. (Citation2018) demonstrated that empowered nurses more highly perceive the quality of their work life than others. Similarly, Badawy et al. (Citation2018) found psychological empowerment as a stimulus for employees’ QWL. Empowerment also causes employee satisfaction with their work and work life (Howe, Citation2014; Laschinger & Read, Citation2017). Even though the significance of empowerment for employees’ work life is evident, the implications are still lacking in the case of employees in the hospitality industry, especially in developing and underdeveloped countries. Therefore, the present study attempted to extend the earlier research by incorporating both structural and psychological empowerment to examine the effect of empowerment on hospitality staff’s QWL. Therefore, the following hypothesis was developed:

H1: Employee empowerment has a positive influence on quality of work life.

2.6. ICT support and quality of work life

Firm performance and employee efficiency are mostly dependent on the exchange of knowledge and information (Morelos-Gómez & Posso-Martínez, Citation2018). Technological support also makes individuals’ social life happy and peaceful (Nevado-Peña et al., Citation2019), since they can easily balance their work life and non-work life, which accordingly impacts their well-being too (Adisa & Gbadamosi, Citation2018; Demerouti et al., Citation2014). From another perspective, by disseminating new knowledge and information, ICT humanizes the workplace as well as enriches employees’ working life (Kotze, Citation2005). Empirical evidence shows that when jobs are designed by aligning ICT, employees can share information effortlessly with their team members (Hannif et al., Citation2014). These working people can get the benefits of schedule and place flexibility (Adisa & Gbadamosi, Citation2018; Demerouti et al., Citation2014), and accordingly, they highly perceive the quality of their work life (Hannif et al., Citation2014). However, no research has been found that investigates the impact of a firm’s ICT facilities on employee-focused outcomes, especially their work life in the hospitality industry context. Thus, this study intended to explore the aforesaid effect and developed the following hypothesis:

H2: ICT support has a positive influence on quality of work life.

2.7. Employee empowerment and climate of trust

Trust is widely regarded, at the workplace, as a significant phenomenon, since trust promotes attitudes, behavior, and mutual understanding of organizational members (Buvik & Rolfsen, Citation2015; Hughes et al., Citation2018; Krog & Govender, Citation2015). Research has indicated that trust can be nurtured by the participative decision-making process (Gilbert & Tang, Citation1998; Krog & Govender, Citation2015). Managers distribute authority only when they can trust their employees. Afterward, when employees perceive that managers respect their trustworthiness, they consequently trust their managers and co-workers (Laschinger et al., Citation2005; Moye & Henkin, Citation2006). Thus, empowerment develops mutual trust (Vanhala & Ahteela, Citation2011). Research has exposed that employee empowerment facilitates trust development in the organization (Buvik & Rolfsen, Citation2015; Laschinger et al., Citation2012). However, these pieces of literature offer an inadequate explanation of the influence of a firm’s empowerment practices on its trust climate. This gap influences the present study, which empirically investigates the association between employee empowerment and climate of trust. Therefore, a hypothesis can be developed as:

H3: Employee empowerment has a positive influence on climate of trust.

2.8. ICT support and climate of trust

Technological support helps an organization remove the boundaries between employers and employees (Bissola et al., Citation2014). Effective technologies ensure the authenticity and reliability of the information, which thereby helps build trust between the parties involved (Bissola et al., Citation2014; Bondarouk et al., Citation2017). When corporate information is communicated transparently and timely, a high level of trust is generated in individuals (H. Jiang & Luo, Citation2018). Thus, the deployment of appropriate and updated technologies results in the development of a trusting climate in the establishment (Bala & Bhagwatwar, Citation2017). Moreover, an updated communication system helps in trust-building throughout the organization (Buvik & Rolfsen, Citation2015; Khan et al., Citation2018). These pieces of evidence indicate that technological support for communicating knowledge and information can generate mutual trust between the parties involved, although the effect of ICT support on the climate of trust has not been investigated yet. Therefore, the current study aimed to explore the aforementioned impact and hypothesized as follows:

H4: ICT support has a positive influence on climate of trust.

2.9. Climate of trust and quality of work life

Satisfaction in an individual’s working life is stimulated by the mutual trust among the working people and managers in the organization (Al-Shalabi, Citation2019). Research argues that trust climate and employees’ work life may have a possible link (Akter et al., Citation2021; Blömeke et al., Citation2015; L. Jiang & Probst, Citation2015). The early scholars explained the significance of an atmosphere of shared and mutual trust in the organization; e.g., Cascio (Citation1992) explained how the successful implementation of QWL practices mostly depends on trust between employees and managers. In addition, Shaw (Citation2005) indicated that the success of QWL programs is determined by the organization’s ability to reinforce high levels of trust. Besides, empirical evidence demonstrated that a trust climate acts as a crucial factor in improving the level of employee satisfaction (Blömeke et al., Citation2015; L. Jiang & Probst, Citation2015) and enriching happiness with their work lives (Akter et al., Citation2021). Hence, researchers suggest building a trust climate in the firm to enhance the quality of employees’ work life (Akter et al., Citation2021; Al-Shalabi, Citation2019; L. Jiang & Probst, Citation2015). Furthermore, an atmosphere of mutual trust encourages people to take risks and accept responsibility for mistakes or errors that arise in the team (Langfred, Citation2004; Mayer et al., Citation1995). This study hypothesizes as follows:

H5: Climate of trust has a positive influence on quality of work life.

2.10. Mediation effect of climate of trust

Trust is found, in the above discussions, as a key outcome of empowerment and ICT application of a firm, and as an antecedent of people’s peaceful work life. Individuals cannot enjoy their work life unless they are provided with coordination and cooperation in the team, which is caused by a climate of shared and mutual trust (Braun et al., Citation2013; Dirks & Skarlicki, Citation2009). A team climate based on mutual trust stimulates social connections, maximizes resource utilization, and synthesizes multiple views that facilitate converting the managers’ considerations into improved firm outcomes (Carmeli et al., Citation2012; Shih et al., Citation2012). Moreover, a trust climate fosters cognitive exchanges that encourage social persuasion (Shih et al., Citation2012), and thus it impacts employee-focused outcomes (Blömeke et al., Citation2015; L. Jiang & Probst, Citation2015).

Indeed, prior research has exposed that a climate of trust mediates the relationship between leadership and firm performance (Lin et al., Citation2016), organizational justice, conflict management, and employee relations (Sahoo & Sahoo, Citation2019), and transformational leadership and quality of work life (Akter et al., Citation2021). Therefore, this study proposes that a climate of trust can be instituted as a mediating variable in the association between empowerment and QWL and between ICT support and QWL. The following hypotheses are proposed:

H6: Climate of trust mediates the relationship between employee empowerment and quality of work life.

H7: Climate of trust mediates the relationship between ICT support and quality of work life.

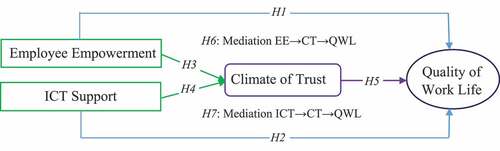

3. Development of theoretical framework and research model

Based on the concept of the socio-technical systems (STS) theory, the study proposed a theoretical framework that would illustrate the influence of employee empowerment, ICT support, and climate of trust on the quality of work life. The STS theory, advocated by Trist and Bamforth (Citation1951), aims to optimize both the social and technical aspects of an organization to ensure its smooth operations. An organization comprises human beings (social systems) who require tools, techniques, and knowledge (technical systems), while both systems are interdependent (Pasmore, Citation1988). When an organization utilizes these systems effectively, the work life of employees are enhanced, as is organizational efficiency (Cherns, Citation1976; Pasmore, Citation1988). Socio-technical systems emphasize employee involvement in the work design that stimulates employee fulfillment and their wellbeing (Brooks et al., Citation2007). In the STS theory, researchers advocate employee empowerment in respect of their job satisfaction (Persico & McLean, Citation1994). Furthermore, the technical aspect of the STS theory indicates having an information system in an organization that includes effective communication channels to share knowledge and information (Cherns, Citation1976). The STS theory argues that an expected type of climate can be developed within an organization when both social and technical aspects are utilized (Persico & McLean, Citation1994). The theoretical framework is presented through a model (Figure ), including the hypotheses of the study, which will be tested through empirical analysis.

4. Methods

4.1. Data collection

The study carried out a questionnaire survey for data collection. The full-time operational employees of the three-star hotels in Bangladesh were the target population of the study. There are 20 three-star hotels in Bangladesh, according to the Ministry of Civil Aviation and Tourism of Bangladesh. 13 hotels consented to participate in this study, constituting the target population (N) of 437. The Krejcie and Morgan’s (Citation1970) Table shows that the sample size is 201–205, when the population size is 420–440. Therefore, this study randomly selected 205 respondents from the population and distributed a self-administered questionnaire to the target respondents during March-April, 2021. A total of 147 filled questionnaires were returned, which led to a response rate of 71.7 percent. Due to the existence of missing and outliers values, 24 responses were removed. Finally, 123 completed responses were accepted for analysis. N. Hayes (Citation2000) suggested that a typical questionnaire response rate between 20 percent and 30 percent may be considerable. Sekaran (Citation2003) also approved a 30 percent response rate as an acceptable rate for data analysis. As a result, an overall response rate of 70.7 percent is considered satisfactory for further analysis.

4.2. Measures

Employee empowerment was measured by seven items of B.E. Hayes (Citation1994). A sample item of this construct was: “I am allowed to do almost anything to perform a high-quality job”. ICT support was measured by five items: two items of Saleem et al. (Citation2017), two items of Majchrzak et al. (Citation2005), and one item of Drent and Meelissen (Citation2008). A sample item of ICT support was: “I can access the information system at any time from anywhere”. Further, climate of trust was measured by four items of Huff and Kelley (Citation2003). A sample item of trust climate was: “Managers in this company trust their subordinates to make good decisions”. In terms of QWL, these thirty-four items of Kwahar and Iyortsuun (Citation2018). A sample item of quality of work life was: “Fair and unbiased promotion system”. Responses of all the measurement items were collected on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

4.3. Control variables

Prior studies exposed the influence of employees’ demographic characteristics, e.g., gender (Ganesh & Ganesh, Citation2014; Mosadeghrad et al., Citation2011; Vanhala & Ahteela, Citation2011), age (Gupta & Hyde, Citation2013; Vanhala & Ahteela, Citation2011), work experience (Dhamija et al., Citation2019; Gupta & Hyde, Citation2013; Vanhala & Ahteela, Citation2011), marital status (Vanhala & Ahteela, Citation2011), and education (Mosadeghrad et al., Citation2011) on their quality of work life. Therefore, this study considers five demographic characteristics (age, gender, work experience, marital status, and education) of the respondents as control variables.

4.4. Data analysis

For analyzing the proposed research model, a partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was used. Data were processed and analyzed by SPSS 21 and SmartPLS 3.0 software. Respondents’ information and the variables’ descriptive statistics were examined by SPSS 21. After that, this study assessed the validity and reliability of the measures by analyzing a reflective measurement model. Further, the hypothesized relationships were tested by analyzing a structural model using PLS-SEM procedures. For testing the hypotheses and examining the mediation effect, a bootstrapping function (5000 resamples) was generated in SmartPLS 3.0.

5. Results

5.1. Respondent characteristics

The sample of this study consisted of about 65.9 percent male respondents and 34.1 percent female respondents. Most of the respondents were from the 35 to 44 age group (39.03 percent), followed by the 25 to 34 age group (36.59 percent), less than 25 years age group (14.63 percent), 45 to 54 age group (8.94 percent), and 55 to 65 age group (0.81 percent). In terms of marital status, the majority of the respondents were married (65.04 percent), whereas 25.2 percent were unmarried, 4.07 percent were separated, 4.07 percent were widowed and 1.62 percent were divorced. For education, respondents mostly had post-graduation (58.53 percent), while 37.4 percent had graduation, and 4.07 percent had a higher secondary certificate. The respondents were serving in different operational divisions, e.g., housekeeping (28.46 percent), food and beverage production (17.88 percent), food and beverage service (29.27 percent), leisure and lifestyle (13.82 percent), and the front office (10.57 percent). Out of all the respondents, 39.84 percent had 6 to 10 years of professional experience, while 30.89 percent had 1 to 5 years experience, 20.33 percent had 11 to 15 years experience, and 8.94 percent had more than 15 years experience.

5.2. Common method variance

This study undertook the Harman’s single-factor test, to assess the common method variance. By an unrotated factor analysis on all measurement items, eight (8) factors were extracted with an eigenvalue greater than 1 (Appendix A). These eight (8) factors accounted for 72.6 percent of the total variance. Factor one accounted for only 40.23 percent of the variance. The value is considered good since it is not higher than 50 percent of the covariance (Kumar, Citation2012). In this study, the common method variance was not a major concern, since a single factor did not emerge and the first factor did not account for most of the variance (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003).

5.3. Descriptive statistics and correlations

The study conducted a descriptive analysis and correlation analysis of the constructs (employee empowerment, ICT support, climate of trust, and quality of work life). Table demonstrates the scores of mean, standard deviation (SD) of the variables, and the correlation coefficients among the variables. Correlation coefficients confirmed that the variables have positive and significant correlations with each other.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients

5.4. Measurement model analysis

This study carried out a confirmatory factor analysis for assessing the reliability and validity of the measurement scales of the constructs. To examine the reliability and validity, the values of the measurement model are reported in Table , Table and Table .

Table 2. Results of reliability and convergent validity

Table 3. Results of Fornell-Larcker Criterion

Table 4. Results of Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT)

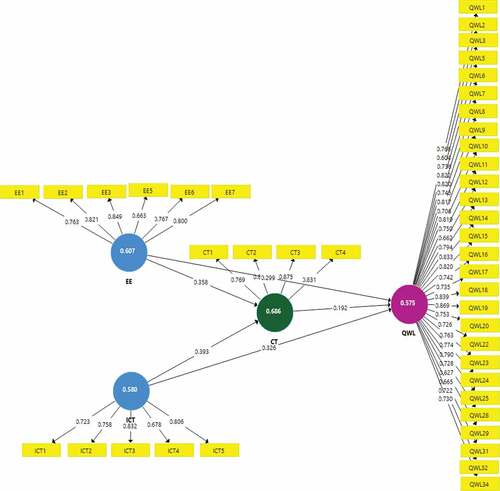

5.4.1. Convergent validity

This study assessed the convergent validity using the factor loadings, composite reliability, Cronbach’s alpha, and average variance extracted (Chin, Citation1998). The scores are exhibited construct-wise in Table (Figure ). The loadings greater than 0.6 were retained (Chin, Citation1998). Seven items (EE4, QWL4, QWL21, QWL26, QWL27, QWL30, QWL33) were removed from the model due to their lower loadings (Appendix B). Further, composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha met the minimum cut-off values (0.7), and the average variance extracted was higher than 0.5 for all the constructs. Therefore, the results confirmed the reliability and convergent validity of the constructs (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981).

5.4.2. Discriminant validity

This study assessed the model’s discriminant validity using the cross-loadings of the indicators, the Fornell–Larcker criterion, and the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT; Hair et al., Citation2017). The cross-loading results indicated that indicators’ outer loadings with the corresponding constructs were higher than the cross-loadings with other constructs (Appendix B). Therefore, the measurement model is considered satisfactory (Hair et al., Citation2017).

In terms of Fornell and Larcker’s (Citation1981) criterion, the correlations between the constructs and the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) of each construct were compared (Table ). As seen in the results, the square root of AVE (diagonals) was greater than the correlation (off-diagonal) of each construct indicating the required discriminant validity of the constructs (Hair et al., Citation2017).

Further, this study examined the HTMT outcomes that are presented in Table . The result of HTMT inference shows that the confidence interval does not show a value of one (1) on any of the constructs (Henseler et al., Citation2015), thus, all the values fulfill the criterion of HTMT. This result confirms the discriminant validity of the measurement model of this study.

5.5. Structural equation model analysis

5.5.1. Collinearity statistics (VIF) testing

To assess the collinearity issue of the structural model of this study, the Inner VIF values were checked. Table shows all the Inner VIF values for the independent variables (Employee empowerment, ICT Support, and climate of trust). All the values were less than 5 thus indicating collinearity was not a concern in this study (Hair et al., Citation2017).

Table 5. Results of Inner VIF values

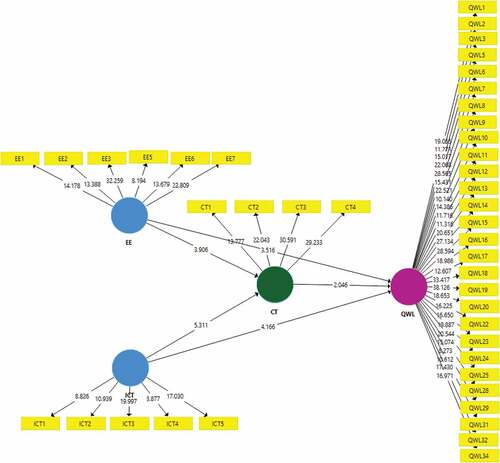

5.5.2. Hypotheses testing for direct relationship

The study tested the hypotheses using the bootstrapping function and the results are presented in Table (Figure and Figure ). Five hypothesized relationships H1 (t = 3.516), H2 (t = 4.166), H3 (t = 3.906), H4 (t = 5.311) and H5 (t = 2.046) were found significant (p < 0.05) with a t-value higher than 1.645 (one-tailed; Hair et al., Citation2017). Hypothesis 1 (β = 0.299) indicated that employee empowerment has a strong influence on quality of work life. The result of hypothesis 2 (β = 0.326) also showed that ICT support has a significant impact on quality of work life. Therefore, H1 and H2 were accepted suggesting that employee empowerment and ICT support have significant impacts on quality of work life.

Table 6. Results of hypothesis testing

Furthermore, the result in support of hypothesis 5, exposed that climate of trust (β = 0.192) has a considerable influence on quality of work life. So, H5 was accepted. Similarly, the result of hypothesis 3 (β = 0.358) indicated the significant influence of employee empowerment on climate of trust. Finally, as of the result of hypothesis 4 (β = 0.393), ICT support has a strong influence on climate of trust. So, H3 and H4 were also accepted. The outcomes suggested that both employee empowerment and ICT support have significant direct effects on trust climate.

5.5.3. Coefficient of determination (R2), effect size (f2), and predictive relevance (Q2) analysis

The study evaluated the predictive accuracy of the model through the coefficient of determination (R2) value (Table and Figure ). All the exogenous constructs (employee empowerment, ICT support, and climate of trust) explained 42.1% of the variance in quality of work life. Further, the exogenous constructs (employee empowerment and ICT support) were explaining 38.1% of the variance in climate of trust. Both the R2 values (QWL = 0.421 and CT = 0.381) were higher than 0.26 that indicates a substantial model (Cohen, Citation1988).

Table 7. Results of coefficient of determination (R2), effect size (f2), and predictive relevance (Q2) testing

Next, the impacts of the predictor constructs on the endogenous construct were evaluated using Cohen’s (Citation1988) f2. The value of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 represent small, medium, and large effects respectively (Cohen, Citation1988). Results (Table and Figure ) indicated that employee empowerment (0.115), and ICT support (0.132) had close to medium effect in producing the R2 for quality of work life, while climate of trust (0.039) had a small effect in producing the R2 for quality of work life. Furthermore, employee empowerment (0.182), and ICT support (0.220) have a medium effect in producing the R2 for climate of trust.

In addition, the study examined the predictive relevance (Q2) of the model using the blindfolding procedure. As presented in Table , the Q2 values for quality of work life (0.209) and climate of trust (0.235) are more than zero (0), which indicated the sufficient predictive relevance of the model (Hair et al., Citation2017).

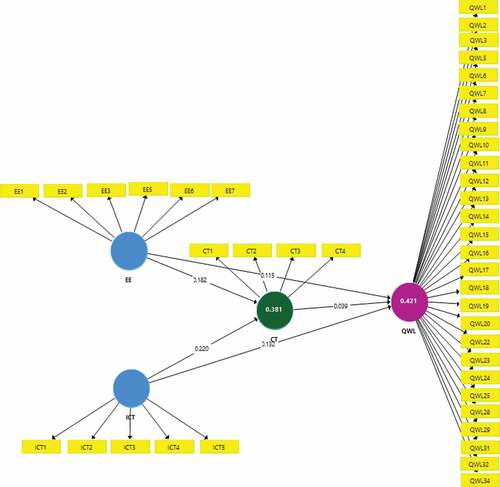

5.5.4. Hypotheses testing for mediating effect analysis

The study assessed the mediation effect of trust climate between employee empowerment and quality of work life, and ICT support and quality of work life. As reported in Table , the indirect effect of employee empowerment on quality of work life (EE→CT→QWL) with β = 0.069 was found significant (t = 1.726, p < 0.05). Similarly, a significant (t = 1.865, p < 0.05) indirect effect of ICT support on quality of work life (ICT→CT→QWL) with β = 0.075 was found. Therefore, H6 and H7 were accepted.

Table 8. Results of mediation effect testing

Besides, the confidence intervals of the indirect paths were observed (Table ), as of Hair et al.’s (Citation2017) recommendation. In terms of both the relations, no zero (0) was observed between the confidence intervals based on the t-value. Moreover, all the effects of employee empowerment and ICT support on quality of work life were significant, which indicated the partial mediation effect of trust climate on both the relations (Badawy et al., Citation2018).

5.5.5. Control variable analysis

This study controls some factors (gender, age, marital status, education, division/department, and experience) which were identified as important on employees’ QWL in the Bangladeshi hospitality industry. The results indicated that education (t = 2.378) was only found to have a significant influence on employees’ QWL, whereas the other four control variables were found as insignificant (Table ).

Table 9. Summary of the results of control variables

6. Discussion

This study surveyed the hospitality employees and revealed seven major findings aligning with the hypotheses of the study. First, the result confirmed that employee empowerment has a strong influence on employees’ quality of work life. This finding is in line with the results of prior research that exhibited the positive association between empowerment and employees’ work life quality (Howe, Citation2014; Nayak et al., Citation2018; Nursalam et al., Citation2018). These aforementioned studies exhibited how the empowerment practices of an organization stimulate employees’ peaceful life at work. Second, ICT support was revealed as an influential factor of quality of work life. Previously it was found that when an organization utilizes appropriate technologies for transmitting knowledge and information in the work teams, it eases employees’ assigned duties and enhances their happiness of work life (Bonomi et al., Citation2019; Demerouti et al., Citation2014; Hannif et al., Citation2014). Third, a significant effect of employee empowerment on trust climate was found. The finding matches with the earlier studies, which demonstrated that empowerment is a consequence of managers’ trust in employees as well as a cause of employees’ trust in the managers/corporation, thus empowerment predicts mutual trust at the workplace (Buvik & Rolfsen, Citation2015; Mone et al., Citation2011). Fourth, it was observed that ICT support has a significant influence on the climate of trust. Prior research exposed that institutional support in utilizing and accessing the appropriate technologies for communicating information among the team members consequences an atmosphere where people trust others (Bala & Bhagwatwar, Citation2017; Bissola et al., Citation2014). Fifth, this study found a significant impact of climate of trust on work life quality of people. This finding corroborates the results of prior studies revealing that a workplace with an atmosphere of shared and/or mutual trust can improve the peace and happiness of people’s work lives (Akter et al., Citation2021; Blömeke et al., Citation2015; L. Jiang & Probst, Citation2015).

Sixth, the results demonstrated the mediation effect of trust climate between employee empowerment and quality of work life. The results confirmed that both direct and indirect effects of employee empowerment on quality of work life were significant. It indicates the partial absorption of the direct effects of employee empowerment by the trust climate, consequently, the mediation is partial (Badawy et al., Citation2018). Finally, the results demonstrated the mediation effect of trust climate between ICT support and quality of work life. Both the effects of ICT support on the quality of work life were found significant, which indicates the partial absorption of the direct effects of ICT support by the climate of trust (Badawy et al., Citation2018). Thus, it can be confirmed that a hospitality firm’s trust climate partially mediates the relationship between employee empowerment and quality of work life, and between ICT support and quality of work life. These findings are consistent with the results of some prior studies that investigated the mediation effect of trust climate. For example, Akter et al. (Citation2021) revealed the mediation effect of trust climate in the relationship between transformational leadership and quality of work life. Similarly, Lin et al. (Citation2016) showed trust climate as a mediating factor between leadership and corporate success. Furthermore, Sahoo and Sahoo (Citation2019) exposed the mediating effect of climate of trust in the relationship between organizational justice, conflict management, and employee relations.

7. Implications

The findings of this study have several implications for managers. First, since employee empowerment influences an organizational climate of trust that further affects employees’ work life quality, managers need to formulate effective empowerment strategies which will improve employee perception of life at work. And since, service-providing companies require independently responsive personnel in the frontline of the customer service operation, firms need to allow them greater freedom for decision-making. Second, the findings demonstrate that providing appropriate ICT support to the working people has a significant effect on their quality of work life. Thus, hospitality firms need to provide updated and appropriate technological support to the operators so that they can have access to the information whenever they need it for being independently responsive to their job. Third, the significant influence of climate of trust on employees’ quality of work life suggests that managers of hospitality firms should formulate strategies to enrich employees’ work life. Fourth, while establishing programs for employee empowerment and ICT support, hospitality managers in developing and under-developed countries could prioritize those measures that have the most potentials to positively affect employees’ work life quality. This is especially essential because hospitality companies and systems in under-developed nations have fewer resources. Therefore, it may be useful for these firms to begin with the most critical areas of empowerment and ICT support, then adopt additional measures depending on the performance results. This strategy would assist the managers in striking a balance between the firm’s success and the employee-focused results.

The findings of the study are consistent with the fundamental principle of socio-technical systems theory, which emphasizes employees’ work life, strongly promotes employee empowerment for their job satisfaction, and argues for the adoption of a technical system in the organization that maintains its information flow. The study also contributes to the literature on hospitality personnel management. Firstly, the study findings suggest that hospitality firms’ practices toward empowering and providing ICT facilities to employees have positive and different effects on their work life. In light of this finding, it can be acknowledged that the impacts are particularly substantial for the essentials of the firm’s organizational practices. Thus, the study detects the dominating areas of these organizational practices (empowerment and ICT support), which can contribute to people’s work life and corporate climate of trust. In accordance with the tenets of hospitality firms, this study affirms that hospitality individuals are independently responsive staff when they are allowed to participate in the firm’s decisions and access information technology. Additionally, the elements of empowerment and ICT support contribute to the people’s work and non-work life quality. Secondly, this study suggests that a trust climate can consequence the enhancement of employees’ quality of work life particularly in the presence of organizational empowerment and ICT support as antecedents. It can be argued that a shared trust climate of a hospitality firm plays a significant role in enriching happiness in their work life. Third, the positive influence of employee empowerment and organizational ICT support on QWL suggests that the happiness of employees’ work life is not just dependent on organizational success. It is also dependent on corporate endeavors and intentions for taking care of employee satisfaction and their well-being. Therefore, this study identifies several key aspects of firm-initiated antecedents for diversified outcomes of employee satisfaction in hospitality firms.

8. Limitations and future research directions

There are some limitations to this study. First, this research was carried out at three-star hotels, so, future research may incorporate the diversified hospitality firms. Second, the study only looked at one country (Bangladesh). Thus, future research may look at the multi-country context for validating the proposed research model, because management styles and approaches in human resource issues greatly differ from country to country. Third, further studies may also explore the firms’ working conditions that support or oppose the enrichment of an individual’s work life. Finally, future research may observe the moderation effect of staff’s socio-economic condition and job nature in the aforementioned relationships that will provide new insights regarding the QWL outcomes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kaniz Marium Akter

Kaniz Marium Akter has 15 years of teaching experience and has published several articles in Indexed and Peer-reviewed journals. Presently, she is pursuing her PhD in the School of Business Management, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Malaysia.

Swee Mei Tang

Swee Mei Tang is a faculty member of School of Business Management, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Malaysia. Her area of interest is Human Resource Management with special focus on human resource planning, recruitment and selection, and performance management. She supervises PhD students too.

Zurina Adnan

Zurina Adnan is a faculty member of School of Business Management, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Malaysia. Her area of interest is Business Management and Human Resources Management with special focus on employee well-being, firm performance, employee commitment, and organizational communication. She supervises PhD students too.

References

- Abuhashesh, M., Al-Dmour, R., & Masa’deh, R. (2019). Factors that affect employees’ job satisfaction and performance to increase customers’ satisfactions. Journal of Human Resources Management Research, 4, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.5171/2019.354277

- Adamovic, M. (2017). An employee-focused human resource management perspective for the management of global virtual teams. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(14), 2159–2187. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1323227

- Adisa, T. A., & Gbadamosi, G. (2018). Regional crises and corruption: The eclipse of the quality of working life in Nigeria. Employee Relations, 41(3), 571–591. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-02-2018-0043

- Akman, Y., & Akman, G. İ. (2017). The effect of the perception of primary school teachers’quality of work life on work engagement. Elementary Education Online, 16(4), 1491–1504. https://doi.org/10.17051/ilkonline.2017.342971

- Akter, K. M., Tang, S. M., & Adnan, Z. (2021). Transformational leadership and quality of work life: A mediation model of trust climate. [Cdata[problems and Perspectives in Management], 19(4), 161–174. https://doi.org/10.21511/ppm.19(4).2021.14

- Alhozi, N., Hawamdeh, N. A., & Al-Edenat, M. (2021). The impact of employee empowerment on job engagement: Evidence from Jordan. International Business Research, 14(2), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v14n2p90

- Alshaabani, A., Oláh, J., Popp, J., & Zaien, S. (2020). Impact of distributive justice on the trust climate among Middle Eastern employees. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 21(1), 34–47. https://doi.org/10.17512/pjms.2020.21.1.03

- Al-Shalabi, F. S. (2019). The relationship between organisational trust and organisational identification and its effect on organisational loyalty. International Journal of Economics and Business Research, 18(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEBR.2019.100646

- Arbabisarjou, A., & Allameh, S. M. (2012). Relationship between information & communication technology and quality of work-life; a study of faculty members of Zahedan University. Life Science Journal, 9(4), 3322–3331.

- Ardahaey, F. T., & Nabilou, H. (2012). Human resources empowerment and its role in the sustainable tourism. Asian Social Science, 8(1), 33–38. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v8n1p33

- Avi, M. A. R., & Sardar, S. (2021). Application of innovative technologies in the tourism and hospitality industry of Bangladesh: Challenges and suggestions. In A. Hassan (Ed.), Technology Application in the Tourism and Hospitality Industry of Bangladesh (pp. 369–379). Springer.

- Badawy, T. A. E., Srivastava, S., & Magdy, M. M. (2018). Psychological empowerment as a stimulus of organisational commitment and quality of work-life: A comparative study between Egypt and India. International Journal of Economics and Business Research, 16(2), 232–249. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEBR.2018.094015

- Bala, H., & Bhagwatwar, A. (2017). Employee dispositions to job and organization as antecedents and consequences of information systems use. Information Systems Journal, 28(4), 650–683. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12152

- Bissola, R., Imperatori, B., & Emma Parry and Professor Stefan Strohmeier, D. (2014). The unexpected side of relational e-HRM: Developing trust in the HR department. Employee Relations, 36(4), 376–397. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-07-2013-0078

- Blömeke, S., Hoth, J., Döhrmann, M., Busse, A., Kaiser, G., & König, J. (2015). Teacher change during induction: Development of beginning primary teachers’ knowledge, beliefs and performance. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 13(2), 287–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-015-9619-4

- Bondarouk, T., Harms, R., & Lepak, D. (2017). Does e-HRM lead to better HRM service? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(9), 1332–1362. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1118139

- Bonomi, S., Ricciardi, F., & Rossignoli, C. (2019). ICT in a collaborative network to improve quality of life: A case of fruit and vegetables re-use. In Y. Baghdadi & A. Harfouche (Eds.), ICT for a Better Life and a Better World, Lecture Notes in Information Systems and Organisation (Vol. 30, pp. 51–67). Springer, Cham.

- Braun, S., Peus, C., Weisweiler, S., & Frey, D. (2013). Transformational leadership, job satisfaction, and team performance: A multilevel mediation model of trust. Leadership Quarterly, 24(1), 270–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.11.006

- Brooks, B. A., Storfjell, J., Omoike, O., Ohlson, S., Stemler, I., Shaver, J., & Brown, A. (2007). Assessing the quality of nursing work life. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 31(2), 152–157. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAQ.0000264864.94958.8e

- Buvik, M. P., & Rolfsen, M. (2015). Prior ties and trust development in project teams–A case study from the construction industry. International Journal of Project Management, 33(7), 1484–1494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.06.002

- Carmeli, A., Tishler, A., & Edmondson, A. C. (2012). CEO relational leadership and strategic decision quality in top management teams: The role of team trust and learning from failure. Strategic Organization, 10(1), 31–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127011434797

- Cascio, W. F. (1992). Managing Human resources: Productivity, quality of worklife, profit (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Cherns, A. (1976). The principles of sociotechnical design. Human Relations, 29(8), 783–792. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872677602900806

- Chin, W. (1998). Issues and opinion on structural equation modelling. MIS Quarterly, 22(1), 7–16. https://www.jstor.org/stable/249674

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd) Erlbaum.

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

- Demerouti, E., Derks, D., Lieke, L., & Bakker, A. B. (2014). New ways of working: Impact on working conditions, work–family balance, and well-being. In Korunka, C., & Hoonakker, P. eds. The impact of ICT on quality of working life (pp. 123–141).

- Dhamija, P., Gupta, S., & Bag, S. (2019). Measuring of job satisfaction: The use of quality of work life factors. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 26(3), 871–892. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-06-2018-0155

- Dirks, K. T., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2009). The relationship between being perceived as trustworthy by coworkers and individual performance. Journal of Management, 35(1), 136–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308321545

- Drent, M., & Meelissen, M. (2008). Which factors obstruct or stimulate teacher educators to use ICT innovatively? Computers & Education, 51(1), 187–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2007.05.001

- Farndale, E., Van Ruiten, J., Kelliher, C., & Hope-Hailey, V. (2011). The influence of perceived employee voice on organizational commitment: An exchange perspective. Human Resource Management, 50(1), 113–129. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20404

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement errors. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Ganesh, S., & Ganesh, M. P. (2014). Effects of masculinity-femininity on quality of work life: Understanding the moderating roles of gender and social support. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 29(4), 229–253. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-07-2013-0085

- Gilbert, J. A., & Tang, T. L. (1998). An examination of organizational trust antecedents. Public Personnel Management, 27(3), 321–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/009102609802700303

- Gill, M. J., & Sypher, B. D. (2010). Workplace incivility and organizational trust. In P. Lutgen-Sandvik & B. D. Sypher (Eds.), Destructive Organizational Communication: Processes, consequences, and constructive ways of organizing (pp. 69–90). Taylor & Francis Group.

- GOB. (2019). Bangladesh Economic Review 2019. Finance Division, Ministry of Finance, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. http://www.mof.gov.bd/economic/index.php

- GOB. 2021. National Tourism Human Capital Development Strategy for Bangladesh: 2021-2030. Bangladesh Tourism Board, Ministry of Civil Aviation and Tourism, Government of the People‘s Republic of Bangladesh.

- Gordon, S., Tang, C. H., Day, J., & Adler, H. (2019). Supervisor support and turnover in hotels: Does subjective well-being mediate the relationship? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(1), 496–512. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2016-0565

- Greasley, K., Bryman, A., Dainty, A., Price, A., Naismith, N., & Soetanto, R. (2008). Understanding empowerment from an employee perspective: What does it mean and do they want it? Team Performance Management: An International Journal, 14(1/2), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1108/13527590810860195

- Greasley, K., Bryman, A., Dainty, A., Price, A., Soetanto, R., & King, N. (2005). Employee perceptions of empowerment. Employee Relations, 27(4), 354–368. https://doi.org/10.1108/01425450510605697

- Gupta, B., & Hyde, A. M. (2013). Demographical study on quality of work life in nationalized banks. Vision, 17(3), 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972262913496727

- Guzzo, R. F., Wang, X., Madera, J. M., & Abbott, J. (2021). Organizational trust in times of COVID-19: Hospitality employees’ affective responses to managers’ communication. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 93, 102778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102778

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage publications Inc.

- Hannif, Z., Cox, A., & Almeida, S. (2014). The impact of ICT, workplace relationships and management styles on the quality of work life: Insights from the call centre front line. Labour & Industry: a Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of Work, 24(1), 69–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/10301763.2013.877120

- Haq, M. A., Usman, M., & Khalid, S. (2018). Employee empowerment, trust, and innovative behavior: Testing a path model. Journal on Innovation and Sustainability, 9(2), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.24212/2179-3565.2018v9i2p3-11

- Hayes, B. E. (1994). How to measure empowerment. Quality Progress, 27, 41–46.

- Hayes, N. (2000). Doing Psychological Research: Gathering and analyzing data. Open University Press.

- Heischman, R. M., Nagy, M. S., & Settler, K. J. (2019). Before you send that: Comparing the outcomes of face-to-face and cyber incivility. The Psychologist-Manager Journal, 22(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1037/mgr0000081

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Howe, E. E. (2014). Empowering certified nurse’s aides to improve quality of work life through a team communication program. Geriatric Nursing, 35(2), 132–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2013.11.004

- Huff, L., & Kelley, L. (2003). Levels of organizational trust in individualist versus collectivist societies: A seven-nation study. Organization Science, 14(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.14.1.81.12807

- Hughes, M., Rigtering, J. C., Covin, J. G., Bouncken, R. B., & Kraus, S. (2018). Innovative behaviour, trust and perceived workplace performance. British Journal of Management, 29(4), 750–768. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12305

- Jiang, Z., Gollan, P. J., & Brooks, G. (2015). Moderation of Doing and mastery orientations in relationships among justice, commitment, and trust: A cross-cultural perspective. Cross Cultural Management, 22(1), 42–67. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCM-02-2014-0021

- Jiang, H., & Luo, Y. (2018). Crafting employee trust: From authenticity, transparency to engagement. Journal of Communication Management, 22(2), 138–160. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-07-2016-0055

- Jiang, L., & Probst, T. M. (2015). Do your employees (collectively) trust you? The importance of trust climate beyond individual trust. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 31(4), 526–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2015.09.003

- Khan, H. U. R., Ali, M., Olya, H. G., Zulqarnain, M., & Khan, Z. R. (2018). Transformational leadership, corporate social responsibility, organizational innovation, and organizational performance: Symmetrical and asymmetrical analytical approaches. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 25(6), 1270–1283. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1637

- Korunka, C., & Hoonakker, P. (2014). The impact of ICT on quality of working life. Springer.

- Kotze, M. (2005). The nature and development of the construct quality of work life. Acta Academia, 37(2), 96–122. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC15322

- Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447003000308

- Krog, C. L., & Govender, K. (2015). The relationship between servant leadership and employee empowerment, commitment, trust and innovative behaviour: A project management perspective. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 13(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v13i1.712

- Kumar, B. (2012). A Theory of Planned Behaviour Approach to Understand the Purchasing Behaviour for Environmentally Sustainable Products. IIMA. India, Research and Publications, 12(8), 1–43. http://hdl.handle.net/11718/11429

- Kwahar, N., & Iyortsuun, A. S. (2018). Determining the underlying dimensions of quality of work life (QWL) in the Nigerian Hotel Industry. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 6(1), 53–70. https://doi.org/10.15678/EBER.2018.060103

- Langfred, C. W. (2004). Too much of a good thing? Negative effects of high trust and individual autonomy in self-managing teams. Academy of Management Journal, 47(3), 385–399. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159588

- Laschinger, H. K. S., Finegan, J., Hughes, M., Rigtering, J. P. C., Covin, J. G., Bouncken, R. B., & Kraus, S. (2005). Empowering nurses for work engagement and health in hospital settings. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 35(10), 439–449. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005110-200510000-00005

- Laschinger, H. K. S., Leiter, M. P., Day, A., Gilin-Oore, D., & Mackinnon, S. P. (2012). Building empowering work environments that foster civility and organizational trust. Nursing Research, 61(5), 316–325. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNR.0b013e318265a58d

- Laschinger, H. S., & Read, E. (2017). Workplace empowerment and employee health and wellbeing. In C. L. Cooper & M. P. Leiter (Eds.), The Routledge companion to wellbeing at work (pp. 182–196). Taylor & Francis Group.

- Lee, J. J., Ok, C. M., & Hwang, J. (2016). An emotional labor perspective on the relationship between customer orientation and job satisfaction. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 54, 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.01.008

- Lin, H.-C., Dang, T. T. H., & Liu, Y.-S. (2016). CEO transformational leadership and firm performance: A moderated mediation model of TMT trust climate and environmental dynamism. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 33(4), 981–1008. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-016-9468-x

- Majchrzak, A., Malhotra, A., & John, R. (2005). Perceived individual collaboration know-how development through information technology–enabled contextualization: Evidence from distributed teams. Information Systems Research, 16(1), 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1050.0044

- Matthew, O. A., Ede, C., Osabohien, R., Ejemeyovwi, J., Ayanda, T., & Okunbor, J. (2021). Interaction effect of tourism and foreign exchange earnings on economic growth in Nigeria. Global Business Review, 22(1), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150918812985

- Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734. https://doi.org/10.2307/258792

- Mone, E., Eisinger, C., Guggenheim, K., Price, B., & Stine, C. (2011). Performance management at the wheel: Driving employee engagement in organizations. Journal of Business and Psychology, 26(2), 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-011-9222-9

- Morelos-Gómez, J., & Posso-Martínez, R. A. (2018). Evaluation and relevance of the information and communication technologies in small and medium-sized enterprises in the export sector in Cartagena-Colombia. Entramado, 14(2), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.18041/1900-3803/entramado.2.4727

- Mosadeghrad, A. M., Ferlie, E., & Rosenberg, D. (2011). A study of relationship between job stress, quality of working life and turnover intention among hospital employees. Health Services Management Research, 24(4), 170–181. https://doi.org/10.1258/hsmr.2011.011009

- Moye, M. J., & Henkin, A. B. (2006). Exploring associations between employee empowerment and interpersonal trust in managers. Journal of Management Development, 25(2), 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710610645108

- Nayak, T., Sahoo, C. K., & Mohanty, P. K. (2018). Workplace empowerment, quality of work life and employee commitment: A study on Indian healthcare sector. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 12(2), 117–136. https://doi.org/10.1108/JABS-03-2016-0045

- Nevado-Peña, D., López-Ruiz, V.-R., & Alfaro-Navarro, J.-L. (2019). Improving quality of life perception with ICT use and technological capacity in Europe. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 148, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.119734

- Nursalam, N., Fibriansari, R. D., Yuwono, S. R., Hadi, M., Efendi, F., & Bushy, A. (2018). Development of an empowerment model for burnout syndrome and quality of nursing work life in Indonesia. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 5(4), 390–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2018.05.001

- Oh, S. Y. (2022). Effect of ethical climate in hotel companies on organizational trust and organizational citizenship behavior. Sustainability, 14(13), 7886. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137886

- Ozturk, A., & Karatepe, O. M. (2019). Frontline hotel employees’ psychological capital, trust in organization, and their effects on nonattendance intentions, absenteeism, and creative performance. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 28(2), 217–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2018.1509250

- Pasmore, W. A. (1988). Designing effective organizations: The sociotechnical systems perspective (Vol. 6). Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Persico, J., & McLean, G. N. (1994). The evolving merger of socio-technical systems and quality improvement theories. Human Systems Management, 13(1), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.3233/HSM-1994-13103

- Peterson, N. A., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2004). Beyond the individual: Toward a nomological network of organizational empowerment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 34(1–2), 129–145. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:AJCP.0000040151.77047.58

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Qiu, S., Alizadeh, A., Dooley, L. M., & Zhang, R. (2019). The effects of authentic leadership on trust in leaders, organizational citizenship behavior, and service quality in the Chinese hospitality industry. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 40, 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.06.004

- Rahman, M. K., & Hassan, A. (2021). Tourist Experience and Technology Application in Bangladesh. In Hassan, A (Ed.), Technology Application in the Tourism and Hospitality Industry of Bangladesh (pp. 319–332). Springer.

- Rahman, M., Islam, R., Husain, W. R. W., & Ahmad, K. (2019). Developing a hierarchical model to enhance business excellence in hotel industry of Bangladesh. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(4), 1836–1856. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-02-2018-0110

- Rubel, M. R. B., Kee, D. M. H., & Rimi, N. N. (2021). High commitment human resource management practices and hotel employees’ work outcomes in Bangladesh. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 40(5), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.22089

- Saban, D., Basalamah, S., Gani, A., & Rahman, Z. (2020). Impact of Islamic work ethics, competencies, compensation, work culture on job satisfaction and employee performance: The case of four-star hotels. European Journal of Business and Management Research, 5(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.24018/ejbmr.2020.5.1.181

- Sahoo, R., & Sahoo, C. K. (2019). Organizational justice, conflict management and employee relations: The mediating role of climate of trust. International Journal of Manpower, 40(4), 783–799. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-12-2017-0342

- Saleem, F., Salim, N., Altalhi, A. H., Ullah, Z., Ghamdi, A. L., & Khan, Z. M. (2017). Assessing the effects of information and communication technologies on organizational development: Business values perspectives. Information Technology for Development, 26(1), 54–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2017.1335279

- Sari, N. P. R., Bendesa, I. K. G., & Antara, M. (2019). The influence of quality of work life on employees’ performance with job satisfaction and work motivation as intervening variables in star-rated hotels in Ubud tourism area of Bali. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, 7(1), 74–83. https://doi.org/10.15640/jthm.v7n1a8

- Schulte, M., Cohen, N. A., & Klein, K. J. (2012). The coevolution of network ties and perceptions of team psychological safety. Organization Science, 23(2), 564–581. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0582

- Sekaran, U. (2003). Research methods for business: A skill-building approach. John Wiley & Sons.

- Shaw, W. H. (2005). Business ethics. Thomson Wadsworth.

- Sheehan, M., Grant, K., & Garavan, T. (2018). Strategic talent management: A macro and micro analysis of current issues in hospitality and tourism. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 10(1), 28–41. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-10-2017-0062

- Shih, H. A., Chiang, Y. H., & Chen, T. J. (2012). Transformational leadership, trusting climate, and knowledge exchange behaviors in Taiwan. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23, 1057–1073. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.639546

- Simsek, H. (2020). The relationship between organizational commitment and organizational cynicism levels of accounting employees in hotel enterprises: The case of kemer. Global Journal of Management and Business Research, 20(9), 10–22. https://journalofbusiness.org/index.php/GJMBR/article/view/3124

- Sirgy, M. J., Efraty, D., Siegel, P., & Lee, D. J. (2001). A new measure of quality of work life (QWL) based on need satisfaction and spillover theory. Social Indicators Research, 55(3), 241–302. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010986923468

- Tan, H. H., & Tan, C. S. F. (2000). Toward the differentiation of trust in supervisor and trust in organization. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 126(2), 241–260. https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/lkcsb_research/2678

- Tripura, K., & Avi, M. A. R. (2021). Application of Innovative Technologies in the Tourism and Hospitality Industry of Bangladesh: Role Analysis of the Public and Private Institutions. In A. Hassan (Ed.), Technology Application in the Tourism and Hospitality Industry of Bangladesh (pp. 215–226). Springer.

- Trist, E. L., & Bamforth, K. W. (1951). Some social and psychological consequences of the longwall method of coal-getting: An examination of the psychological situation and defences of a work group in relation to the social structure and technological content of the work system. Human Relations, 4(1), 3–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675100400101

- Vanhala, M., & Ahteela, R. (2011). The effect of HRM practices on impersonal organizational trust. Management Research Review, 34(8), 869–888. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409171111152493

- Walton, R. E. (1973). Quality of working life: What is it? Sloan Management Review, 15(1), 11–21.

- Walton, R. E. (1975). Improving the quality of work life. Harvard Business Review, 52(3), 12–16.

- Yousuf, A. S. M. (1996). Evaluating the quality of work life. Management and Labour Studies, 21(1), 5–15.

- Zimmerman, M. (2000). Empowerment theory: Psychological, organizational and community level analysis. In J. Rappaport & E. Seidman (Eds.), Handbook of community psychology (pp. 43–63). Plenum.

Appendix A.

Common Method Variance

Total Variance Explained

Appendix B.

Convergent and discriminant validity: Outer loadings and cross-loadings