Abstract

The post-covid-19 era has witnessed the need for mobile-wallet app adoption due to non-physical transactions. Prior researchers have captured consumers’ mobile-wallet adoption by involving facilitators or inhibitors. The detailed effect of facilitators and inhabitations in developing consumers’ intention regarding mobile-wallet apps in a single model remain untapped in the marketing literature. The current study used two lenses: behavioral reasoning theory and gender schema theory, to investigate reasons for and against mobile-wallet adoption in Pakistan. For this purpose, two independent but relevant studies were performed. Study 1 involved respondents from the Punjab province, while study 2 mainly focused on the other three provinces of Pakistan, i.e., Sindh, Baluchistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. PLS was used for SEM and Multigroup analysis. Study 1ʹs results revealed that attitude significantly influences intention. Moreover, “reason for” and “reason against” significantly affect consumers’ attitudes and intentions for mobile-wallet app adoption. Study 2 confirmed the results of study 1 and provided significant differences between males and females regarding mobile-wallet adoption. Such as, males have a more substantial influence on mobile-wallet apps’ adoption than females.

Public Interest Statement

The rapid development of Internet technology in emerging countries such as Pakistan has radically altered the individual’s retail and shopping experiences. In the previous decade, customers have shown a clear preference for using novel mobile-based payment options over more conventional payment methods for the payment of purchased goods. In addition, non-physical transactions in the post-covid-19 era have necessitated using mobile-wallet apps. Several studies have been published on mobile-wallet adoption, but previous researchers have only discussed either facilitators or inhibitors of mobile-wallet adoption. However, the literature lacked a comprehensive model explaining the reason for and against mobile-wallet adoption. Therefore, this study is grounded on behavioral reasoning theory and gender schema theory to explore reasons for and against adopting mobile-wallet in Pakistan. The research has some noteworthy theoretical and practical contributions discussed in the manuscript, which boost mobile-wallet adoption.

1. Introduction

The fast expansion of Internet technology radically alters consumers’ retail and shopping experiences (Lee et al., Citation2022; Lim et al., Citation2021). During the last decade, consumers’ preferences in retail payments have steadily switched from traditional payment methods toward innovative mobile-based payment solutions (Verkijika, Citation2020). Mobile-based payment solutions have been widely used for retail payments as mobile commerce and online shopping has grown. The notion of a mobile wallet emerges as an enhanced method of financial transactions in the scope of mobile-based payments. Mobile-wallet has changed the face of e-commerce and financial services enormously. Mobile-wallet is a digitalized replacement for traditional wallets that use phone storage to hold digital money and cards (B. Shaw & Kesharwani, Citation2019). Faster payments, security, bulk payments, reduced fraud, carrying less cash, efficiency and time-saving, and so on are all advantages of mobile wallets (Sharma et al., Citation2018). However, even though mobile wallets have established a foothold in the retail consumer market for mobile-based payments in the previous decade, they have not yet experienced significant growth (Verkijika, Citation2020).

In the same vein, recent research has revealed that, except for a few early adopters, reaching widespread adoption of mobile-wallet is still a long way, despite delivering various benefits (Leong et al., Citation2020a). The adoption and acceptance of mobile-wallet around the world are quite low. Pasquali (Citation2023) reports that the percentage of merchants embracing mobile-wallet payment solutions rose from 24% to 29% between 2015 and 2018. However, only 39% of all smartphone users worldwide own an m- wallet mobile account. This reflects that the mobile-wallet market is still in its infancy stage, indicating substantial consumer resistance towards mobile-wallet adoption. Therefore, empirical research is needed to identify the significant predictors precisely because the COVID-19 pandemic forced consumers to adopt mobile-wallet for payments because there is a growing concern about handling potentially contaminated cash (Daragmeh et al., Citation2021) .

Most of the existing studies have independently studied the motives or facilitating factors that influence mobile-wallet adoption (Chatterjee & Bolar, Citation2018; Chawla & Joshi, Citation2019, Citation2020a, Citation2020b; B. Shaw & Kesharwani, Citation2019), as well as the inhibitors or barriers that prevent consumers from adopting mobile-wallet (Leong et al., Citation2020a; Sharma et al., Citation2018). Researchers should concentrate on both aspects, including the facilitators (i.e., acceptance) and the inhibitors (i.e., resistance) of any invention, action or behavior (Sahu et al., Citation2020). This is because both factors are quantitatively different, and these factors affect consumer decision-making in diverse ways. To our understanding, no previous empirical research has comprehensively studied both aspects (acceptance/resistance) of mobile-wallet in a single framework. Hence, this research employs a novel consumer behavior model, behavioral reasoning theory (BRT; Westaby, Citation2005b), which allows researchers to test acceptance and resistance factors in a unified framework to understand consumers’ intentions to adopt mobile wallets. Therefore, this study aims to narrow down this gap.

In this study, the second gap indicates that consumers’ attitudes about mobile-wallet may not be gender-specific. Studies on technology acceptance and usage have proven that men and women use technology differently and have differing self-perceptions towards technology (e.g., women are more likely to become technophobes, whereas men are more prone to become technophiles; Sobieraj & Krämer, Citation2020). In addition, gender schema theory (GST) asserts that information is processed and interpreted differently, as gender is a fundamental difference between individuals (Bem, Citation1981). From a theoretical point of view, most of the past research has shown the digital divide between men and women regarding technology-related behavior. From practitioners’ perspective, it is vital to study gender differences because they are considered an important basis for market segmentation. Thus, examining the gender differences in the mobile-wallet context is warranted because gender is often one of the most important variables to consider when developing marketing strategies.

In light of the preceding debate, this study contributes incrementally to the domain in two ways, first, by studying the facilitators and inhibitors in consumers’ decision-making towards mobile-wallet adoption. It assists marketers, policymakers, and other stakeholders understand acceptance and resistance factors towards mobile-wallet adoption. Secondly, this study also considers how genders (i.e., men vs women) respond differently towards mobile-wallet adoption in the studied associations. It provides insights to marketers to design appropriate marketing strategies to enhance mobile-wallet adoption.

Pakistan was selected as the context of the present study because, In Pakistan, demonetization has boosted digital payments and prompted people to go cashless. Through this move, government intends to remove counterfeited money, remove black money, prohibit money laundering to terrorist operations and create a cashless economy. We can unlock $36 billion in digital finance potential through mobile-based payment solutions in Pakistan. A 7% increase in GDP created 4 million jobs with the widespread adoption of digital payments in Pakistan. Despite having one of the fastest-growing internet savvy populations in the world, Pakistan has a low adoption of mobile-based payments. In Pakistan, just 18% of the population uses digital payments. In Pakistan, a single digital transaction is made every year, compared to 5 in India and 7 in Indonesia (Saeedi, Citation2019). Pakistan may outpace its counterparts by accelerating digital payments.

2. Literature review

2.1. Behavioral reasoning theory (BRT)

The existing studies discuss that it is necessary for organizations to understand better whether, when and why individuals will adopt innovative technology (Gupta & Arora, Citation2017a; Pillai & Sivathanu, Citation2020; Sahu et al., Citation2020). Prior research has investigated the consumers’ adoption of innovation from a different theoretical lens, including the theory of reasoned action (TRA), theory of planned behavior (TPB), diffusion of innovation theory (DOI), and technology acceptance model (TAM). However, these theories have been critiqued since they primarily focus on acceptance-related determinants while ignoring the variables that relate to customer resistance (Claudy et al., Citation2015; Gupta & Arora, Citation2017a; Sahu et al., Citation2020). It is crucial to include the barriers to consumption in any theoretical model because it enables the researchers to analyze the various thoughts mechanisms that consumers use to develop their attitudes and intentions (Westaby, Citation2005b).

The past literature has demonstrated that innovative products/services fail significantly due to low concentration on numerous causes of individuals’ resistance to adoption (Antioco & Kleijnen, Citation2010). In the case of mobile-wallet, the situation is similar, as most previous research has concentrated on positive determinants that affect the intentions to use mobile-wallet. Subsequently, the consumers’ willingness to adopt mobile-wallet is limited. Therefore, policymakers are increasingly concerned about the issue to be examined as early as possible. To meet this demand, researchers agree that new behavioral models must be identified, developed and used promptly to provide a complete picture of determinants that drive individuals’ acceptance and resistance to adopting innovative technology (Claudy et al., Citation2015).

Moreover, BRT is considered a theoretical model which allows practitioners and academicians to determine the impact of reasons, involving “reasons for” and “reasons against”, on individuals’ intentions to adopt innovative technology (Claudy et al., Citation2015; Gupta & Arora, Citation2017a; Westaby, Citation2005b). BRT differs from other acceptance research models since the latter considers the “reasons for” adopting any innovation. Researchers have argued that the “reasons against” inhibiting innovative technology are not always the reverse of the “reasons for” adopting it (Claudy et al., Citation2015; Gupta & Arora, Citation2017b; Pillai & Sivathanu, Citation2020). It indicates that adoption facilitators and inhibitors may not be rational opposites (Westaby et al., Citation2010). However, a complete understanding of consumers’ consumption behavior prompts an evaluation of both “reasons for” and “reasons against”.

In the same vein, BRT not only enables researchers to differentiate between the “reasons for” and “reasons against” but also allows them to test the impact of various cognitive routes (through the reason for and against) on individuals’ intentions and behavior through the use of a unified decision-making model (Claudy et al., Citation2015; Gupta & Arora, Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Pillai & Sivathanu, Citation2020). Subsequently, BRT describes behaviors more thoroughly than other theoretical models by adding context-specific reasons which assist the individuals in rationalizing their behaviors (Tandon et al., Citation2020; Westaby, Citation2005b; Westaby et al., Citation2010).

Besides, BRT establishes the empirical relationship between “values, reasons for, reasons against, attitude, and intentions.” Based on the above reasons, present empirical research has demonstrated that BRT can account for a higher proportion of variation in user intentions than alternative acceptance models (Claudy et al., Citation2015; Gupta & Arora, Citation2017a; Tandon et al., Citation2020). Academics have used BRT to study consumer behavior in a various fields, including food waste (Talwar et al., Citation2021), brand love (Sreen et al., Citation2021), innovation adoption (Chatzidakis & Lee, Citation2013; Claudy et al., Citation2013, Citation2015; Westaby et al., Citation2010) and mobile banking (Gupta & Arora, Citation2017a, Citation2017b). In short, these previous studies indicate that BRT provides a unified and comprehensive framework for determining the consumers’ attitudes, intentions and behavior (Gupta & Arora, Citation2017b; Ryan & Casidy, Citation2018).

2.2. Research model and hypotheses development

2.2.1. Research model

BRT is used as a baseline theory in this study to develop a research model for understanding mobile-wallet behavior. BRT comprises four primary components: values, reasons, attitude and intentions. Behavioral intention refers to the consumers’ predisposition to perform a task or an action (M. J. Kim et al., Citation2018). In contrast, an attitude refers to the degree of evaluation of favorable or unfavorable consequences of behavior. e.g., if a person has a favorable attitude toward a particular behavior, then he or she is more prompt to involve in that behavior. On the other hand, a negative evaluation of the consequences will certainly result in disengagement (Sreen et al., Citation2021; Talwar et al., Citation2021; Westaby et al., Citation2010).

Moreover, BRT asserts that individuals’ cognitive processing behavior is dominated by reasoning (Claudy et al., Citation2015). Based on the theory of reasons and explanation-based decision-making theory, it is argued that reasons are the strongest determinants of attitude that lead to behavioral intention (Westaby, Citation2005b). Consistent with the reasoning theories, individuals have compelling “reasons for” and “reasons against” involved in a particular behavior that enables them to defend their tasks. As a result, additional variables associated with behavioral intention are also activated. In addition, the “reasons” are divided into two distinct sub-categories: “reasons for” and “reasons against,” which in the previous literature have also been identified as adoption (facilitators) and resistance (inhibitors) factors (Gupta & Arora, Citation2017a; Westaby, Citation2005b). However, reasons consist of different context-specific variables that may facilitate to better understand the individuals’ intentions (Claudy et al., Citation2015; Sreen et al., Citation2021; Westaby, Citation2005b).

In addition, values are abstract cognition that gives a complete code of life and is essential in determining an individual’s attitude (Austin & Vancouver, Citation1996; Dreezens et al., Citation2005). Besides, it is considered that values are firmed believes that influence the individual’s behavior. As a result, value is regarded as a primary element in BRT.

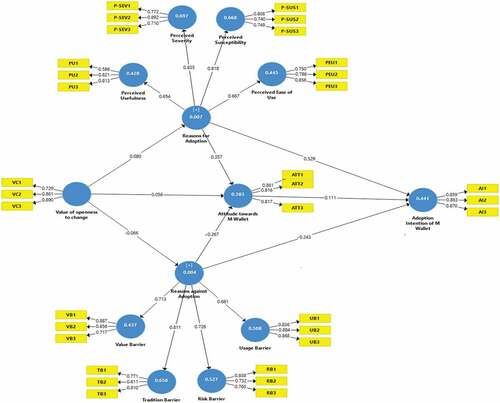

Moreover, based on hypotheses, associations among variables are depicted in the existing theoretical framework (see Figure ). Second-order measures the “reasons for” and “reasons against.” “Perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness” were used to measure the “reason for”, while risk, value, usage and tradition barriers were used to measure the “reason against.” The value (i.e., openness to change), ATT and intentions towards mobile-wallet were determined using single-order.

2.2.2. Hypotheses development

2.2.2.1. Attitude and intentions

Attitude refers to “a psychological tendency that is expressed by evaluating a particular entity (e.g.-innovation) with some degree of favor or disfavor” (Eagly & Chaiken, Citation1998, p. 1). Most behavior models try to predict intention since it is widely regarded as a strong predictor of subsequent behavior. Previous studies argue that a favorable attitude positively and significantly related to individual’s intentions to perform a particular task (Gupta & Arora, Citation2017a; Sreen et al., Citation2021; Talwar et al., Citation2021; Tandon et al., Citation2020). In the contexts of internet banking (Hanafizadeh et al., Citation2014) and mobile banking (Giovanis et al., Citation2019; Gupta & Arora, Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Samat et al., Citation2022; Wessels & Drennan, Citation2010; Zamil et al., Citation2022) it has been found that attitude is considered as one of the significant predictors of new technology adoption.

H1: Attitude towards mobile wallet significantly and positively associated with mobile-wallet adoption intentions.

2.2.2.2. Reason for, attitude and intentions

In the case of specific behavior, “reasons for” were considered facilitators or motivators capable of eliciting positive feelings among customers. This study selected the “reason for” using mobile-wallet to be comprised of “perceived susceptibility to covid-19, perceived severity of covid-19, perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness” because previous studies on mobile wallet have emphasized the significance of these four reasons (Ahadzadeh et al., Citation2015, Citation2017; CC & Prathap, Citation2020; Chawla & Joshi, Citation2020a). Besides, this study also identified similar context-specific reasons based on the reason elicitation process (For details on reasons elicitation see, section 3.1.3)

Individuals’ adoption of mobile payment can be deemed a preventive healthcare practice, as it protects them from becoming infected through direct and face-to-face contact with others during the pandemic. Based on reasons elicitation, it is considered that individuals’ beliefs regarding susceptibility and severity of pandemic disease influence their decision to initiate particular preventative action. Perceived susceptibility to COVID-19 represents “a person’s view of the likelihood of experiencing a potentially harmful condition.” On the other hand, perceived severity represents “how threatening the condition is to the person” (Champion, Citation1984). Previous studies has examined the association between perceived susceptibility, perceived severity and users’ intentions to adopt technology while investigating the intention towards mobile health services (Dou et al., Citation2017; Sun et al., Citation2013; Wei et al., Citation2020; Zhao et al., Citation2018). Moreover, Alaiad et al. (Citation2019) argued that individuals who perceive m-payment as beneficial demonstrate a positive attitude toward using mobile-wallet when considering health risks.

Different theories, including the technology acceptance model, have examined technology-related behavior in various studies involving the internet, computer use and health. Moreover, it is deemed that perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness influence the individuals’ decision towards technology adoption (i.e., mobile wallet). The PEOU and PU are significant predictors of individuals’ attitudes and behavioral intentions towards technology adoption. In the mobile-wallet context, PEOU is defined as the users’ belief that there is the minimum effort required to use and learn mobile wallets. In contrast, PU refers to the belief that using mobile wallets will improve his or her performance. Perceived susceptibility to COVID-19, perceived severity of COVID-19 (Ahadzadeh et al., Citation2015; CC & Prathap, Citation2020), PEOU and PU (Ahadzadeh et al., Citation2018; Chawla & Joshi, Citation2020a; Davis, Citation1989), the four factors make up the cognitive belief component of technology usage, since they determine people’s attitudes toward innovative technology and influencing their usage level.

Previous studies recommended that “reasons for” were a crucial measure in influencing consumer behavior in a different context (Claudy et al., Citation2015; Sahu et al., Citation2020; Tandon et al., Citation2020; Westaby et al., Citation2010). For instance, “reason for” using a mobile wallet has a significant and positive association with consumer attitudes and intentions (CC & Prathap, Citation2020; Gupta & Arora, Citation2017a, Citation2017b). Consequently, the “reason for” are related to positive attitude and intentions towards using mobile-wallet. Based on the above discussion, researchers develop the following hypotheses:

H2: “Reasons for” significantly and positively associated with attitude towards mobile-wallet adoption.

H3: “Reasons for” significantly and positively associated with intentions towards mobile-wallet adoption.

2.2.2.3. Reasons against, attitude and intentions

The “reasons against” are jointly deemed as inhibitors, as they can develop unfavorable attitudes towards involving in a particular behavior (Sreen et al., Citation2021). The previous studies adopted extensive use of the widely accepted psychological theory of innovation resistance (IRT) to investigate “reason against” factors of the BRT research model (Kaur et al., Citation2020; Ram & Sheth, Citation1989; Talwar et al., Citation2020). IRT proposed five “reasons against” or inhibitors/barriers to involvement in a particular behavior: risk, value, usage, image and tradition (Ram & Sheth, Citation1989). The reason elicitation process revealed that the image barrier was not a barrier in this community (For details on reasons elicitation, see, section 3.1.3.) Due to this, the existing study examined the four barriers or inhibitors: risk, value, usage and tradition barrier.

However, the risk barrier refers to the degree of uncertainty and unpredictability involved with innovation (P. T. Chen & Kuo, Citation2017). Besides, it addresses the resistance that arises due to the uncertainties that are an intrinsic element of any invention (Kaur et al., Citation2020). For instance, in the context of mobile-wallet, individuals perceive risk associated with making errors during electronic transactions because they may be unfamiliar with these procedures (Kaur et al., Citation2020). Such barriers are significantly and negatively associated with individuals’ intentions towards mobile-wallet adoption (Gupta & Arora, Citation2017b; Kaur et al., Citation2020; Marett et al., Citation2015; Sivathanu, Citation2018c).

In our framework, the value barrier is perceived as the most crucial determinant of “reason against.” Value barriers are defined as resistance caused by discrepancies with the established value system, most notably in balancing the expense of utilizing and learning the innovation against the delivered benefits (Morar, Citation2013). Thus, the likelihood of mobile-wallet adoption would rise in proportion to its relative benefits (Kaur et al., Citation2020). The value barrier is significantly related to the perceived monetary benefits individuals receive (Talwar et al., Citation2020). Previous studies confirmed that the value barrier significantly and negatively associated with consumers’ intentions towards mobile-wallet adoption (Leong et al., Citation2020b; Sivathanu, Citation2018c; Talwar et al., Citation2020).

Usage barriers arise when innovation is incompatible with existing practices, workflows, or habits, and it is the primary source of consumer resistance to adopting innovation (Laukkanen et al., Citation2007). In the context of mobile-wallet, the usage barrier determines the resistance created by the efforts needed to learn the app’s functionality (Talwar et al., Citation2020). Previous studies have found a significant negative association between usage barriers and individuals’ intentions to adopt mobile-wallet (Kaur et al., Citation2020; Moorthy et al., Citation2017; Talwar et al., Citation2020).

Tradition barriers are defined as obstacles created by innovation when it disrupts a user’s culture, current routine, or behavior (El Badrawy et al., Citation2012). In mobile-wallet, tradition barriers exist when consumers come to perform banking transactions. They may prefer to use traditional banks instead of mobile-wallet since they are more familiar with the former (Laukkanen, Citation2016; Park & Kim, Citation2016). Additionally, a tradition barrier inhibits individuals from adopting mobile-wallet (Dasgupta et al., Citation2011; Lian & Yen, Citation2013). Previous literature indicates that tradition barriers significantly negatively impact individuals’ adoption intentions towards mobile-wallet (Antioco & Kleijnen, Citation2010).

Prior empirical research has found a negative association between “reasons against” and customer attitudes and intentions (Dhir et al., Citation2021; Sreen et al., Citation2021; Westaby et al., Citation2010). For example, “reason against” using mobile-wallet negatively affects consumers’ attitudes and intentions (Gupta & Arora, Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Kaur et al., Citation2020; Leong et al., Citation2020b). As a result, a similar negative relationship with mobile-wallet is likely to be perceived. Based on the above discussion, the researchers hypothesize that:

H4: “Reasons Against” significantly and negatively associated with attitude towards mobile-wallet adoption.

H5: “Reasons Against” significantly and negatively associated with intentions towards mobile-wallet adoption.

2.2.2.4. Value and attitude

Schwartz (Citation2012) defined values as “Values are critical motivators of behaviors and attitudes.” The current study used openness to change towards mobile-wallet as consumer value of the BRT model. Schwartz (Citation1992) proposed the value (i.e., openness to change) that “motivates people to follow their intellectual and emotional interest in unpredictable and uncertain directions.” It consists of two key components: 1) stimulation: it indicates the need for excitement, variety, and novelty 2) self-direction: it represents the need for autonomy and independence. Besides, consumers with a high level of “openness to change” are more likely to engage in online purchasing and are willing to try new technologies (Raajpoot & Sharma, Citation2006; Wu et al., Citation2009). Moreover, researchers argued that values and beliefs might directly influence attitude as, in certain instances, reasons may not have been completely triggered, and users may depend upon intuitive motives (Westaby, Citation2005b). Similarly, consumers may develop attitudes toward certain objects without defending their intended behavior. Additionally, the previous studies in the domain of consumer behavior confirm the significance of values in buying decision-making (Gupta & Arora, Citation2017a; Kahle et al., Citation1986; Rokeach, Citation1973). Previous studies have found that values significantly influence individuals’ attitudes towards adopting technology/innovation (Claudy et al., Citation2015; Schwartz, Citation2012; Westaby, Citation2005a, Citation2005b).

H6: Value (Openness to change) is significantly and positively associated with attitude towards mobile-wallet adoption.

2.2.2.5. Values and reasons

“Values are one important, an especially central component of our self and personality, distinct from attitudes, beliefs, norms, and traits” (Schwartz, Citation2012). S. Schwartz (Citation2006) defined values as motivational constructs that allow individuals to pursue and achieve their desired goals. However, values direct an individual in examining and selecting different behavior. Based on the theory of explanation-based decision-making proposed by Pennington and Hastie (Citation1988), the reasons theory explained by (Westaby, Citation2005a) and BRT postulates that deep-rooted values significantly influence reasoning (Westaby, Citation2005b). Previous research has confirmed the association between value (i.e., openness to change), and the reason for and against (Gupta & Arora, Citation2017a; Sivathanu, Citation2018c). As stated above, “reasons for” positively and “reasons against” are negatively related to attitude (Claudy et al., Citation2015; Gupta & Arora, Citation2017b, Citation2017a). While referencing previous research on innovation, consumers adopt innovations if it aligns with their personal beliefs (Claudy et al., Citation2013). Thus, researchers formulated the hypothesis:

H7: Value (openness to change) is significantly and positively associated with the “reason for” towards mobile-wallet adoption.

H8: Value (openness to change) is significantly and negatively associated with “reason against” towards mobile-wallet adoption.

3. Study 1

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participant and procedure

Study 1 was conducted in Punjab, a province of Pakistan, using a self-structured questionnaire. The questionnaire has been distributed among mall shoppers using the mall intercept survey method in two leading shopping malls (i.e., Emporium Shopping Mall and Packages Shopping Mall) in Lahore (i.e., capital of Punjab). The mall intercept technique is commonly employed in marketing research (Leong et al., Citation2020b; Yani-de-Soriano et al., Citation2019) and applied in similar studies (Leong et al., Citation2020b). Interceptions were conducted at mall entrances and exits to avoid sample bias and obtain a diverse set of respondents, as suggested by Khong and Ong (Citation2014). Moreover, the survey method is appropriate for our aims as it allows the researchers to assess and confirm the eligibility of target responders and solicit clarification when necessary (Soriano et al., Citation2019).

Shoppers were recruited using a non-probability sampling technique (i.e., purposive sampling) to ensure that the sample provided relevant information while minimizing sampling error (Saunders & Lewis, Citation2017). The survey was undertaken during various times of the day (i.e., morning, afternoon and evening) for a week over two months between December 2020 and February 2021. J. Hair et al. (Citation2010) proposed that the 1:5 ratio of sample size criterion should be maintained in consumer studies. The current study’s questionnaire has 33 items (i.e., 33*5 = 165). Additionally, Nulty (Citation2008) proposed that the ideal response rate for a research questionnaire in a consumer study ranges between 40% and 60%. A total of 327 valid responses were attained among 600 approached shoppers, yielding a response rate of 54.5%. Moreover, a sample size of 327 is perceived as sufficient, surpassing the minimum required sample size. The demographic information of respondents is given in Table .

Table 1. Demographic information of respondents (study 1)

3.1.2. Ethical considerations

Ethical concerns are one of the most crucial aspects of the research. Ethical considerations are usually considered necessary when considering the human element in the study. During participation, the researcher or data collection team must uphold the respondents’ rights (i.e., human rights), such as autonomy, confidentiality, and anonymity (Neuman, Citation2003). This study complied with ethical guidelines to enhance its effectiveness, as Polonsky (Citation1998) recommended. The purpose of the study was presented to the respondents before data collection. In addition, respondents were told that the data acquired would be utilized exclusively for academic purposes. Respondents were invited to respond willingly and were free to leave the study anytime. The respondents were informed that there were no “right” or “wrong” answers and that their anonymity would ensure that their responses would be kept confidential and analyzed only in the aggregate. The ethical consideration for data collection is followed in both study 1 and study 2.

3.1.3. Measures

This study employed a quantitative technique and acquired responses from mall shoppers via a questionnaire survey. All of the items were adapted from previous studies. The value scale (i.e., openness to change) was assessed with three borrowed items (Gupta & Arora, Citation2017a). The scale for perceived susceptibility to covid-19 (three items), and perceived severity of covid-19 (three items) were adapted from (J. Kim & Park, Citation2012; Saleeby, Citation2000), whereas perceived ease of use scale (three items), and perceived usefulness scale (three items) were borrowed from (Bhattacherjee, Citation2001; Davis, Citation1989; Garay et al., Citation2019). Similarly, a three-item scale was employed to measure the risk barrier scale (three items), value barrier scale (three items), usage barrier scale (three items), and tradition barrier scale (three items), which were adopted from (Laukkanen, Citation2016). On the other hand, the attitude scale (three items) and Intentions (three items) scale were borrowed from (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1975; Wong et al., Citation2012). The variables were measured using a seven-point Likert scale. This scale is used to strengthen the reliability and validity of the instrument (Bearden & Netemeyer, Citation1999; Foddy, Citation1994). This scale has more discriminatory power and a wide score distribution (Allen & Rao, Citation2000).

3.1.4. Reason elicitation

This section of the study intends to elicit the reasons towards mobile-wallet adoption. It was decided to perform a qualitative study to determine RF and RA in the context of mobile-wallet. Extant research on BRT has employed the reason elicitation process to determine the reasons (Gupta & Arora, Citation2017b; Pillai & Sivathanu, Citation2020; Sivathanu, Citation2018a; Westaby, Citation2005a, Citation2005b; Westaby et al., Citation2010). Before finalizing the list of reasons, it was discussed with experts in this field, such as top officials from Pakistan’s banking sector, including top managers from Askari bank, Allied bank, Bank Alfalah, Habib Bank, Meezan Bank, and Professors, having PhD degrees and comprehensive experience in research, from the Institute of banking and finance from Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan Pakistan and Hailey college of commerce from Punjab University, Lahore Pakistan.

Twenty bank customers, including men and women in similar numbers, were approached in semi-structured face-to-face interviews to examine the RF adoption of mobile-wallet. Participants of various ages were included in this sample. To elicit the reasons, the process used by Westaby et al. (Citation2010), Claudy et al. (Citation2013, Citation2015), and Chatzidakis and Lee (Citation2013) was adopted. The participants were asked to answer a list of reasons: why I will adopt a mobile wallet. On a scale of 0 to 3 (i.e., a four-point scale), participants were asked to assess how likely each following statement was to be the reason for mobile-wallet adoption. According to Westaby (Citation2005a) and Oh and Teo (Citation2010), the scale was calibrated with 0 representing “not a reason,” 1 representing “a somewhat influential reason,” 2 representing “influential reason,” and 3 representing “very influential reason.” The following are the top four reasons for mobile-wallet adoption: perceived susceptibility to covid-19, perceived severity of covid-19, perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness.

A similar method was used to ascertain “reasons against” adopting mobile-wallet. A list of reasons for responding was offered to the participants: why I will not adopt mobile-wallet. As suggested by Westaby (Citation2005a) and Oh and Teo (Citation2010), the scale was calibrated with a value of 0 representing “not a reason,” 1 representing “a somewhat influential reason,” 2 representing “influential reason,” and 3 representing “very influential reason.” As a result, four barriers to mobile-wallet adoption were identified: risk barrier, value barrier, usage barrier and tradition barrier.

3.2. Data analysis and results

This study examined the theoretical framework using partial least square structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM). Osborne (Citation2010) argued that statistical data mostly has normality concerns in social science studies. PLS-SEM is most frequently used in social science research to examine the measurement and structural model. It has more predictive power in analyzing complex theoretical frameworks with small and large sample sizes and non-normal data (Ali et al., Citation2018; J. F. J. Hair et al., Citation2017). The measurement model tests the instrument’s reliability and validity, while the structured model examines the structured relationships. The bootstrapping approach used over 5000 re-samples to examine the path-coefficient, t-values and significance level as recommended by (Hair et al., Citation2011).

3.2.1. Common method variance (CMV) bias

A cross-sectional survey was used to collect the data. A common method variance can bias the results. Harman’s single-factor test was used to evaluate the concerns regarding CMV biases (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Citation2003). The CMV bias may become a concern if a single factor explains more than 50% of the total variance (Harman, Citation1976). Results revealed that a single factor demonstrated less than 50% of the total variance. Therefore, CMV bias was not a complicated issue.

3.2.2. Measurement model

The measuring model is evaluated by examining the constructs’ reliability and validity. The composite reliability (CR) test assessed the constructs’ reliability. However, Table indicates that CR values range from 0.777 to 0.898, suggesting that all constructs are more than 0.7 (DeVellis, Citation2016). The convergent validity of constructs is examined using factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE). The factor loadings and AVE must exceed 0.7 and 0.5, respectively, for each construct to achieve adequate convergent validity (Hair et al., Citation2016). The findings demonstrate that all constructs surpassed the acceptable value limits (see Table and Figure ). Moreover, hetrotrait-monotrait ratios (HTMT) were used to determine the discriminant validity of all measures. The HTMT scores were less than 0.9 and significantly distinct from 1, indicating that constructs have discriminant validity (J. F. J. Hair et al., Citation2017; Henseler et al., Citation2014; see Table ). Additionally, variance inflation factor (VIF) values were determined to identify the multi-collinearity concerns among variables. Results revealed that VIF values for all constructs are less than 3.3, indicating no multicollinearity issue (Kock & Lynn, Citation2012).

Table 2. Measurement model (study 1)

Table 3. Discriminant validity hetrotrait-monotrait (HTMT) criterion (study 1)

3.2.3. Structural model

Researchers examined the goodness of fit using Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) before determining the hypothesized relationships. The result shows that the SRMR value is 0.061, which is lower than the suggested value of 0.08 (Hu & Bentler Citation1998), indicating an acceptable fit.

After evaluating the model fit, proposed hypothesized associations were examined in the structural model. Table revealed the path-coefficient (β) estimates, their corresponding t-value, p-value, coefficient of determination (R2), model’s predictive relevance (Q2) and effect size (f2). The associations between latent and observed variables are examined using one-tailed t-test criteria with a 95% confidence interval (t > 1.645 and p = 0.05). The results for the study 1 dataset reveal that all hypotheses are significant except for Value (i.e., openness to change) (H6: β = 0.056, t = 0.811 < 1.64, and P > 0.05) on RF, Value (H7: β = 0.080, t = 1.448 < 1.64, and P > 0.05) on RA and Value (H8: β = −0.066, t = 1.205 < 1.64, and P > 0.05) on attitude (see, Figure ).

Table 4. Hypotheses testing (study 1)

The next step is to determine the predictive power of the research model. As shown in Table , the coefficient determination (R2) for consumers’ intentions towards using mobile-wallet is 0.441, demonstrating that the model has weak predictive power (Hair et al., Citation2011). Similarly, the Q2 value for the research model is significantly above zero (0.311), indicating the model’s predictive relevance (Chin, Citation2010; Hair et al., Citation2016). Moreover, Cohen (Citation1988) proposed that f2 scores between 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 be deemed to have small, medium, and large effect sizes. The f2 values for the research model indicate that the effect size ranges between small and medium.

3.3. Discussion

The popularity of the mobile-wallet app has grown over the last decade, but the covid-19 urged consumers to adopt mobile-wallet apps for contactless transactions. For this purpose, the researchers used the BRT theory to assess the consumers’ intentions to adopt mobile-wallet apps. The developed framework provides the association of value, reasons (for and against), and attitude for adopting mobile-wallet apps. The relationship between reasons for and reason against and using intentions is also tested. This study used the PLS-SEM approach to test the hypotheses of the theoretical model. The empirical results found that “reasons for” strongly influence consumers’ attitudes and intention to use mobile-wallet apps in Punjab. Moreover, reasons against have an adverse effect on consumers’ attitudes and intentions.

The results reveal that [H1], which determines the positive association of attitude and intention towards mobile-wallet adoption, is supported. The results agree with previous research on mobile wallet apps (Chawla & Joshi, Citation2020a; Deb & Lomo-David, Citation2014; Lin, Citation2011). The findings suggested that a positive attitude towards mobile-wallet apps leads to the consumers’ behavioural intention.

In addition, [H2] and [H3] determined the positive relationship between reasons for attitude and intentions, supported by findings. The findings are consistent with the previous researchers (Claudy et al., Citation2015; Tandon et al., Citation2020). Similarly, it is found that context-specific RF mobile-wallet adoption is as given: PU (Kapoor et al., Citation2022; Ly et al., Citation2022; Zamil et al., Citation2022), PEOU (Yang et al., Citation2023; Zamil et al., Citation2022), PSUS, and PSEV (Chai et al., Citation2022; Singh & Sharma, Citation2022) are significantly associated with consumers’ attitudes and intentions. Mobile-wallet apps are considered advantageous over traditional transactions due to their health issues and the usefulness of this digital mode. However, the second-order path coefficients for RF suggested that PSUS (B = 0.818) has the highest impact among other RF factors, which is a critical factor for the adoption of mobile-wallet apps. The possible reason for the results is that consumers typically change their behaviour due to their perceived susceptibility to a specific disease. In the covid-19 pandemic, everyone is threatened by interacting with each other, which may drive consumers to adopt mobile-wallet as a coping strategy to deal with potential threats (Covid-19). That is why mobile-wallet app users stood at 62.7 million as of December 2020 end, which was 46.1 million accounts in December 2019. This rapid 36% annual growth was observed during the pandemic, representing the consumers’ primary motive behind using the mobile-wallet app. Moreover, mobile-wallet apps help consumers to manage their cash transactions with one click to buy from e-commerce websites or apps. Its perceived useability and easiness in online transactions motivate consumers to use mobile-wallet apps in this pandemic.

Moreover, [H4] and [H5] determine the negative relationship between RA, and attitude; RA and Intention. The results supported both hypotheses. The results agree with previous researchers who suggested that RA negatively influences consumers’ attitudes and intentions (Claudy et al., Citation2015; Gupta & Arora, Citation2017a). The context-specific RA are risk barrier, value barrier, usage barrier and tradition barrier (Chen et al., Citation2022). These factors act as resistance in adopting innovative products or services like mobile-wallet adoption in Pakistan. Consumers in Pakistan are very strict with their routines and habits. Non-familiarity with the cashless payments systems, less knowledge, fraud and safety risk counter consumers’ positive intentions towards mobile-wallet adoption; however, among these factors, the tradition barrier (B = 0.811) has the strongest influence on the consumers’ attitudes and intentions. Consumers feel difficulty changing their behaviour, traditions and habits as consumers are used to paying in cash. One of the main reasons for this result is that Pakistani consumers are very strict with their daily life routines, culture and habits. They do not usually change their norms and habits. Moreover, the security issue, complex usability, and perceived uncertainty can also resist consumers from adopting the mobile-wallet app (Hopalı et al., Citation2022).

[H6], [H7], and [H8] examined the association of values (openness to change) with attitude, RF and RA. The empirical results of these hypotheses were found to be insignificant. Concerning hypothesis [H6], the results are consistent with previous researchers (Claudy et al., Citation2015; Gupta & Arora, Citation2017a), suggesting that value (openness to change) has an insignificant impact on consumers’ attitudes toward mobile-wallet adoption. [H7] hypothesize the positive association between openness to change and context-specific reasons for mobile-wallet adoption. The results align with the previous studies, suggesting that openness to change does not influence the RF (Pillai & Sivathanu, Citation2020). however contradicts with the findings of (Gupta & Arora, Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Sivathanu, Citation2018a, Citation2018b). [H8] assumes the negative relationship between value and RA, which was also insignificant in the results. The result aligns with the study (Pillai & Sivathanu, Citation2020). The possible reason can be that the selected value (openness to change) is culturally specific, which may not be influential in the Pakistani context. Previous researchers have adopted different values concerning context and found diverse results. BRT is a context-specific theory, and its relationships among variables vary in various contexts (Dhir et al., Citation2021). Secondly, Uncertainty avoidance is high among Pakistani consumers, which may reduce their openness to change or new technology/app acceptance.

4. Study 2

4.1. Design and method

In addition to Study 1, Study 2 has two main objectives. First, this study intends to validate and verify Study 1ʹs findings by testing hypotheses [H1] to [H8] using newly collected data from Pakistani mall shoppers residing in the other three provinces. Second, study 2 investigates whether a shopper’s gender moderates all the associations of the study’s primary research model [H9a] to [H9h].

4.1.1. Literature review

4.1.1.1. The moderating role of gender

Academics and practitioners have begun to pay more attention to the impact of gender inequalities on adopting new technologies. Gender schema theory (GST) is a psychological theory that defines how gender (i.e., men and women) observe and respond in different manners (Bem, Citation1981). Schema has been suggested to guide individuals’ information processing, retrieval, and storage since individuals usually act according to their cognition and past knowledge (Bem, Citation1981). Gender disparities originate because men and women perceive information using distinct processing styles, as proposed in GST. Additionally, Sun and Zhang (Citation2006) research extended GST theory by identifying three significant characteristics that influence gender deformation in decision-making: 1) men are more realistic; 2) women experience greater anxiety when confronted with different processes, and 3) women’s decision-making is affected by their immediate environment.

Moreover, the literature demonstrates that men’s behavior is usually driven by cognition, but women’s behavior is frequently affected by emotion (Smith & Leaper, Citation2006). Meyers-Levy’s (Citation1991) study has also demonstrated similar findings, which indicated that women perceive information holistically, whereas men process information specifically. Additionally, Morahan-Martin and Schumacher (Citation2007) claimed that women tend to be technophobes, associated with a lack of technological expertise and discomfort when interacting with technology. In contrast, men tend to be technophiles with a high level of technical knowledge. In the same vein, Selwyn (Citation2007) discovered that various technologies are viewed as more feminine or masculine; Email, graphics and e-learning are considered feminine technologies, whereas online banking, digital cameras, laptop and digital music are considered masculine.

Furthermore, there has been considerable disagreement over whether the gender differences in technology usage are diminishing (Van Deursen & van Dijk, Citation2014) because some researchers have found no such distinction (L. H. Shaw & Gant, Citation2002). On the contrary, different studies, such as Cooper (Citation2006) demonstrated that there is still a digital gap between men and women regarding technology-related behavior. A recent meta-analysis has supported the main finding that men have more favorable opinions about technology than women (Cai et al., Citation2017), implying that women and men perceive technology. These discrepancies must be studied regularly to determine whether the gender gap is declining. Extent studies have examined gender differences in the adoption of technology, including smartphone adoption (Ameen et al., Citation2020), social media sites (Lai et al., Citation2019), and mobile app adoption (Douglas, Citation2019). Moreover, systematic research on gender differences in adopting innovative mobile apps (i.e., mobile-wallet) is still lacking. As a result, we believe that these different gender roles indicate significant variations in the use of m-violet. Therefore, the researchers hypothesize that:

H9: The impact of a) attitude on intention, b) RF on attitude, c) RF on intention, d) RA on attitude, e) RA on intentions, f) value (i.e., openness to change) on attitude, g) value on RF, h) value on RA towards adoption of mobile-wallet will be moderated by gender.

4.1.2. Participants and measures

A completely new dataset was obtained from 322 Pakistani mall shoppers living in three other Pakistan provinces for validating and generalizing the findings of Study 1 over nationally representative samples of Pakistan. We selected respondents from Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan (almost 100 respondents from every province). These three provinces symbolize Pakistan’s north, east, and south-west zones, respectively, thus eliminating geographical bias in the current study. The data was collected from leading shopping malls in each province’s capital using the same approach as in study 1.

4.1.3. Measures

All of the items used in Study 1 were the same (i.e., Value, RF, RA, ATT, and Intention). Similarly, to satisfy Study 2ʹs second purpose, we operationalized gender into two categories, such as 1 = “male” and 2 = “female”, as suggested by (Gilal et al., Citation2018; Moon, Citation2021; Saleki et al., Citation2020). The demographics of study 2 are presented in Table .

Table 5. Demographic information of respondents (study 2)

4.2. Results

In Study 2, PLS-SEM was used to examine the research model as in study 1 (See above the result section of study 1). The findings indicated that one factor explained 39.929% of the total variance. Thus, CMV bias was not a concern to resolve.

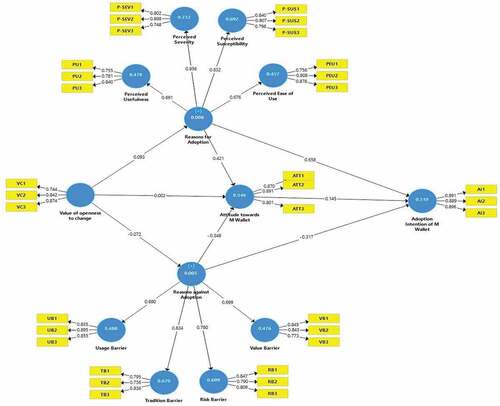

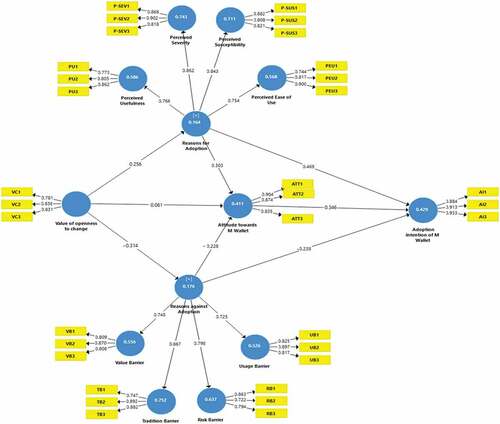

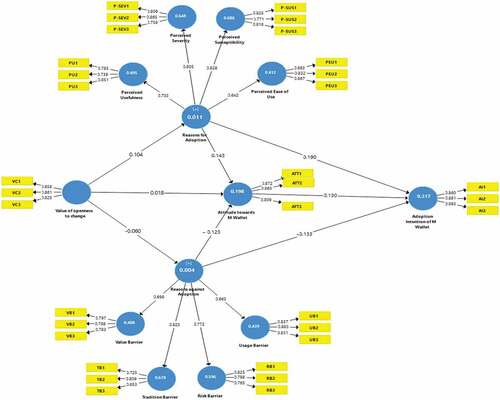

4.2.1. Validation for measurement model

As in study 1, The measurement model for study 2 was validated by examining the variables’ reliability and convergent validity. The results demonstrated that composite reliability (CR) scores for all measures are above the 0.70 (DeVellis, Citation2016), factor loadings for all items are more than 0.7 and AVE for each variable surpassed the threshold value of 0.5 (Hair et al., Citation2016; See Table and Figure ). Thus, the complete and split data sets (for males and females) were reliable and valid. Additionally, the HTMT values were below 0.9, showing that discriminant validity is established for complete and split data sets (J. F. J. Hair et al., Citation2017; Henseler et al., Citation2014; See Table ). Further, VIF values for all constructs are less than 3.3, indicating no multicollinearity concern (Kock & Lynn, Citation2012).

Table 6. Measurement model (study 2)

Table 7. Discriminant validity hetrotrait-monotrait (HTMT) criterion (study 2)

4.2.2. Structural model

The hypothesized associations were tested for a complete and split dataset using the bootstrapping approach with 5000 re-samples. The results of path-coefficient (β) estimate, their related t-value, p-value, coefficient of determination (R2), model’s predictive relevance (Q2) and effect size (f2) for complete and split datasets (see Tables ). The results for the complete dataset show that all of the hypotheses are significant, except for Value (H6: β = 0.002, t = 0.047 < 1.64, and P > 0.05) on attitude, Value (H7: β = 0.093, t = 1.441 < 1.64, and P > 0.05) on RF and (H8: β = −0.072, t = 0.049 < 1.64, and P > 0.05) RA (see Table ). Similarly, all hypotheses are significant for men except Value (H6: β = 0.061, t = 1.325 < 1.64, and P > 0.05) on attitude (see Table and ). The results for the female dataset reveal that all hypotheses are significant except the associations between Value (H6: β = 0.018, t = 0.311 < 1.64, and P > 0.05) and attitude; Value (H7: β = 0.104, t = 1.274 < 1.64, and P > 0.05) and RF; Value (H8: β = −0.060, t = 1.005 < 1.64, and P > 0.05) and RA (see )

Table 8. Hypotheses testing (study 2)

Table 9. Assessment of multigroup analysis

Before conducting multiple group analysis (MGA), an invariance test was undertaken using Assessment of the Measurement Invariance of Composite Models (MICOM) to ascertain whether measurements of constructs were similarly interpreted across both men’s and women’s groups (Henseler, Ringle et al., Citation2016). Consequently, the MICOM procedure established the partial measurement invariance, providing a basis for comparing and analyzing the MGA group-specific discrepancies in the PLS-SEM findings (Henseler, Hubona et al., Citation2016).

4.2.3. Multi-group analysis

This study examines whether the gender of the shoppers moderates all the links in the focal model of the study. PLS multigroup analyses were undertaken to investigate the moderating effect of gender at the 0.05 level, as per recommended by (Henseler, Ringle et al., Citation2016), to examine whether the effects of ATT on intention [H9a], RF on ATT [H9b], RF on intention [H9c], RA on ATT [H9d], RA on intention [H9e], Values on ATT [H9f], Values on RF [H9g], Values on RA [H9h] and respectively, vary according to gender. The study’s findings did not support a significant difference between males and females regarding the effect of value on ATT [H9f]. Table summarizes the results of the multigroup findings derived using the Henseler MGA and permutation test, indicating significant/non significances differences between males and females.

5. Discussion study 2

Study 2 mirrors study 1, as both studies found that reasons (for and reasons against) influence individuals’ intentions. Likewise, study 2 verified these results from the more diverse respondents from different provinces as “reasons for” are more important than reasons against Pakistani consumers. This seems an importance of reason for boosting consumers’ intention regarding mobile-wallet. However, the results suggested that out of eight hypotheses, five are accepted [H1], [H2], [H3], [H4], [H5].

Moreover, study 2 provides additional worth mentioning findings. The study used GST to test the moderating effect of gender on m- wallet adoption and indicate significant differences in male and female behaviour (see Table ). Concerning gender differences, the impact of attitude on intention is much more substantial for males than females, supporting hypothesis H9a. Similarly, the association of RF on attitude and intention are much stronger for male than female, which confirmed hypotheses [H9b] and [H9c]. In addition, the results also demonstrated that the relationship of RA and attitude and intention is higher for men than females, respectively, which supports [H9d] and [H9e]. Moreover, males also have a higher score than females on the relationship of value (openness to change) and RF and RA, respectively, confirming H9f and H9g. However, H9h was not supported because there is no significant difference between males and females in the association of value and attitude. The results align with the marketing literature, which found differences among males and females in their attitudes, intentions and behavior for different product categories (Lim et al., Citation2021; Quoquab et al., Citation2020; Sobieraj & Krämer, Citation2020).

The possible reason for the result is that males and females differ in their cognition structure, values, processing, retrieving, socializing among peers, and decision-making styles. However, this is also dependent on the social system of the culture and society. Culture with male or female dominant roles also characterized the use of technologies (Sobieraj & Krämer, Citation2020). For instance, some technology such as email, e-learning, and socializing apps are considered feminine, and more complex technologies such as digital banking, web development and e-commerce are considered masculine. Pakistan is a masculine country, representing the expected results as males have a strong attitude and RF using mobile-wallet apps than females. Secondly, it is found that male is technophile while females are technophobe. Women are less comfortable as well as less expert in technology. They found it difficult to process information and learn new technologies, while males’ cognition process is higher, and they are likely to understand new technologies. The current study results are also yielded in the same way as males are more open to the mobile-wallet app. They perceived it as valuable and easy compared to women, who are less likely to change their behavior towards adopting mobile-wallet apps. Thirdly, Covid-19 has affected consumers’ behavior significantly overall. Still, the results found that males are more likely to adopt mobile-wallet apps due to perceived susceptibility and severity. At the same time, females are more risk-averse and resist adopting mobile-wallet apps compared to men, who are risk-takers and more adaptive towards new technologies.

5.1. Theoretical contribution

In the field of the mobile-wallet adoption application, the study has specific notable theoretical contributions. The study has three theoretical implications. First, the current study results offer a comprehensive knowledge of the relative effect of facilitators and inhibitors (i.e., reasons for and against) affecting attitudes and intention towards mobile-wallet app adoption. Studying these factors was necessary because most of the studies focused either on facilitators or mobile-wallet adoption inhibitors but simultaneously ignored these factors’ relative effects. The study gives academics a better understanding of phenomena by including context-specific reasons for and against adopting the mobile-wallet app in a unique model.

Secondly, the current study has extended the theoretical foundations of the mobile-wallet app’s adoption based on two main reasons; (a) this is the first empirical research to utilize behavior reasoning theory (BRT) to study mobile-wallet adoption (b) the current research has taken a two-study approach to validate the first study results and, most importantly, apply gender schema theory to adopt the mobile-wallet apps. Previous research has explained the role of gender in consumerism and branding, but very few efforts have been made in the context of mobile-wallet applications (Chawla & Joshi, Citation2020a). In this regard, GST has been explored in Pakistan, and significant differences between male and female consumers have been observed. The study reinforces technological consumer literature by incorporating the diverse technological roles of gender. The study found, for example, that Pakistani men are more technology-driven, complex app adopters such as mobile-wallet apps, whereas women are reluctant.

Third, by studying different factors in Covid-19 situations, this present study opens new insights into the literature. For example, susceptibility to covid-19 is the highest influencing factor of mobile-wallet app adoption in Pakistan. However, Covid-19 affected consumer decisions and purchasing practices due to health concerns. The fear of infected disease due to face-to-face interaction and physical transactions motivates consumers to move towards digital mode.

5.2. Practical contributions

The study has substantial implications for marketers and practitioners. The study found the RF and RA mobile-wallet app adoption, which can be used for developing the marketing strategy. For instance, marketers need to highlight the importance of cashless transactions in this pandemic. The Health Benefits of using mobile-wallet apps can motivate consumers to adopt digital transaction mode as disease-preventing action. The results suggested that consumers adopt the mobile-wallet app if they find it valuable and easy to use. So, mobile-wallet app developers need to focus on convenience, easily downloadable, usable, and compatibility with daily life. Moreover, companies should provide promo videos and tutorials to avoid any difficulty in app usage. However, celebrity endorsement and awareness messages should be communicated to the consumers about app security, advanced lifestyle and a new era to mitigate risk associated with these apps. In this regard, consumers’ habit of using paper currency can be modified gradually.

Additionally, marketers can use this study to apply different marketing strategies concerning gender. It is found that RF and RA have a strong influence on males than females, i.e., males are more likely to use mobile-wallet apps if they find apps beneficial for health, helpful, and easy to use. So marketers should explain different benefits of the app in the advertisement, such as paying bills, transferring money and online shopping with one click without any human interaction. Moreover, the health benefits of mobile-wallet apps should also be communicated to consumers through doctors to prevent the spreading of covid-19. However, the customer base can be increased by providing training, tutorials, first login benefits, referral logins, and special discounts to encourage female consumers to use these financial apps. Additionally, social media platforms should be used to share reviews of existing female consumers about the app’s easiness, useability, security, privacy and advanced features to mitigate risks associated with apps.

5.3. Limitations and future directions

Although the study has some substantial implications, this is still not without limitations. So, future studies may take this study forward by addressing the following limitations. First, the current study collected data through a cross-sectional technique. Empirical studies following cross-sectional design often suffer from potential bias in data collection. So future research should focus on experimental design or longitudinal data collection to overcome this issue. Second, we mainly focused only on the Pakistani context. However, covid-19 affected consumers’ perceptions and behaviour globally. So future research should focus on cross-national or cross-culture studies to increase generalizability by comparing developed and developing countries. Third, the study used BRT to understand the phenomena based on the reasons for and reasons against consumers’ attitudes and intentions. However, many consumers vary in their decision-making by considering the cognitive or affective attitude approach. So future researchers should use a bi-dimensional attitude approach for a better understanding of the decision-making process of the consumers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ahmad S. Ajina

Ahmad S. Ajina is an Associate Professor in Marketing, College of Business Administration, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia. He holds a head of the marketing department and dean of college of business administration at Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University. His research fields include services marketing, consumer behaviour and E-Marketing.

Hafiz Muhammad Usama Javed

Hafiz Muhammad Usama Javed is a research assistant at COMSATS University Islamabad, Sahiwal Campus, Pakistan and pursuing PhD in Management Sciences with specialization Marketing from Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Pakistan. His area of research includes green marketing, sustainable consumption, social media marketing, retail management and consumer behavior.

Saqib Ali

Saqib Ali is an Assistant Professor of Marketing at the Department of Management Sciences, COMSATS University Islamabad Sahiwal Campus. He holds PhD from University Utara Malaysia in Marketing. His research interests lie primarily in Sustainable Consumption, Green Marketing, Political Marketing, Retailing, Consumer Behavior, Brand Management and Social Media Marketing.

Ahmad M. A. Zamil

Ahmad M. A. Zamil is a Professor in Marketing, College of Business Administration, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia. He has published a number of papers in national and international journals and several books on various topics in marketing. His research fields include Marketing management, E-Marketing, E-Retailer, Wom Marketing and Consumer Behavior.

References

- Ahadzadeh, A. S., Pahlevan Sharif, S., Ong, F. S., & Khong, K. W. (2015). Integrating health belief model and technology acceptance model: An investigation of health-related internet use. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(2), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3564

- Ahadzadeh, A. S., Pahlevan Sharif, S., & Sim Ong, F. (2018). Online health information seeking among women: The moderating role of health consciousness. Online Information Review, 42(1), 58–72. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-02-2016-0066

- Alaiad, A., Alsharo, M., & Alnsour, Y. (2019). The determinants of M-health adoption in developing countries: An empirical investigation. Applied Clinical Informatics, 10(5), 820–840. https://doi.org/10.1055/S-0039-1697906

- Ali, F., Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Ryu, K. (2018). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in hospitality research. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(1), 514–538. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2016-0568

- Allen, D. R., & Rao, T. R. (2000). Analysis of customer satisfaction data: A comprehensive guide to multivariate statistical analysis in customer satisfaction, loyalty, and service quality research. Asq Press.

- Ameen, N., Tarhini, A., Hussain Shah, M., & Madichie, N. O. (2020). Employees’ behavioural intention to smartphone security: A gender-based, cross-national study. Computers in Human Behavior, 104(March2020), 106184. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561011079846

- Antioco, M., & Kleijnen, M. (2010). Consumer adoption of technological innovations: Effects of psychological and functional barriers in a lack of content versus a presence of content situation. European Journal of Marketing, 44(11), 1700–1724. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561011079846

- Austin, J. T., & Vancouver, J. B. (1996). Goal constructs in psychology: Structure, process, and content. Psychological Bulletin, 120(3), 338–375. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.120.3.338

- Bearden, W., & Netemeyer, R. (1999). Handbook of marketing scales: Multi-item measures for marketing and consumer behavior research. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Bem, S. (1981). Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychological Review, 88(4), 354–364. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1981-25685-001

- Bhattacherjee, A. (2001). An empirical analysis of the antecedents of electronic commerce service continuance. Decision Support Systems, 32(2), 201–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-9236(01)00111-7

- Cai, Z., Fan, X., & Du, J. (2017). Gender and attitudes toward technology use: A meta-analysis. Computers & Education, 105(February201), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COMPEDU.2016.11.003

- CC, S., & Prathap, S. K. (2020). Continuance adoption of mobile-based payments in Covid-19 context: An integrated framework of health belief model and expectation confirmation model. International Journal of Pervasive Computing and Communications, 16(4), 351–369. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPCC-06-2020-0069

- Chai, L., Xu, J., & Li, S. (2022). Investigating the intention to adopt telecommuting during COVID-19 outbreak: An integration of TAM and TPB with risk perception. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2022.2098906

- Champion, V. (1984). Instrument development for health belief model constructs. Advances in Nursing Science, 6(3), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1097/00012272-198404000-00011

- Chatterjee, D., & Bolar, K. (2018). Determinants of mobile wallet intentions to use: The mental cost perspective. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 35(10), 859–869. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2018.1505697

- Chatzidakis, A., & Lee, M. S. W. (2013). Anti-consumption as the study of reasons against. Journal of Macromarketing, 33(3), 190–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146712462892

- Chawla, D., & Joshi, H. (2019). Consumer attitude and intention to adopt mobile wallet in India – an empirical study. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 37(7), 1590–1618. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-09-2018-0256

- Chawla, D., & Joshi, H. (2020a). The moderating role of gender and age in the adoption of mobile wallet. Foresight, 22(4), 483–504. https://doi.org/10.1108/FS-11-2019-0094

- Chawla, D., & Joshi, H. (2020b). Role of mediator in examining the influence of antecedents of mobile wallet adoption on attitude and intention. Global Business Review, 0972150920924506. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150920924506

- Chen, C. C., Chang, C. H., & Hsiao, K. L. (2022). Exploring the factors of using mobile ticketing applications: Perspectives from innovation resistance theory. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 67, 102974. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JRETCONSER.2022.102974

- Chen, P. T., & Kuo, S. C. (2017). Innovation resistance and strategic implications of enterprise social media websites in Taiwan through knowledge sharing perspective. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 118(May2017), 55–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TECHFORE.2017.02.002

- Claudy, M. C., Garcia, R., & O’Driscoll, A. (2015). Consumer resistance to innovation—a behavioral reasoning perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(4), 528–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0399-0

- Claudy, M. C., Peterson, M., & O’Driscoll, A. (2013). Understanding the attitude-behavior gap for renewable energy systems using behavioral reasoning theory. Journal of Macromarketing, 33(4), 273–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146713481605

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.

- Cooper, J. (2006). The digital divide: The special case of gender. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 22(5), 320–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2006.00185.x

- Daragmeh, A., Sági, J., & Zéman, Z. (2021). Continuous intention to use E-wallet in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: Integrating the Health Belief Model (HBM) and Technology Continuous Theory (TCT). Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(2), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/JOITMC7020132

- Dasgupta, S., Paul, R., & Fuloria, S. (2011). Factors affecting behavioral intentions towards mobile banking usage: Empirical evidence from India. Romanian Journal of Marketing, 6(1), 6–117. https://www.proquest.com/openview/478d497b0b39856146b1d1e233a0a1d5/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=54303

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–339. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

- Deb, M., & Lomo-David, E. (2014). An empirical examination of customers’ adoption of m-banking in India. Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 32(4), 475–494. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-07-2013-0119

- DeVellis, R. F. (2016). Scale development: Theory and applications. SAGE Publications.

- Dhir, A., Koshta, N., Kumar, R., & Sakashita, M. (2021). Behavioral reasoning theory (BRT) perspectives on E-waste recycling and management. Journal of Cleaner Production, 280, 124269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124269

- Douglas, A. (2019). Mobile business travel application usage: Are South African men really from mars and women from venus? Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 10(3), 300–316. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-01-2018-0002

- Dou, K., Yu, P., Deng, N., Liu, F., Guan, Y., Li, Z., Ji, Y., Du, N., Lu, X., & Duan, H. (2017). Patients’ acceptance of smartphone health technology for chronic disease management: A theoretical model and empirical test. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, 5(12), e7886. https://doi.org/10.2196/MHEALTH.7886

- Dreezens, E., Martijn, C., Tenbült, P., Kok, G., & De Vries, N. (2005). Food and values: An examination of values underlying attitudes toward genetically modified-and organically grown food products. Appetite, 44(1), 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2004.07.003

- Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1998). Attitude structure and function (D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey, eds.). Handbook of social Psycholigy.

- El Badrawy, R., El Aziz, R. A., & Hamza, M. (2012). Towards an Egyptian mobile banking era. Computer Technology and Application, 3(11), 765–773. https://www.academia.edu/download/61672622/16_Journal_Rehab_and_Meer_201220200103-477-fxjcm.pdf

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research - philarchive. Addison-Wesley. https://philarchive.org/rec/FISBAI?all_versions=1

- Foddy, W. (1994). Constructing questions for interviews and questionnaires: Theory and practice in social research. Cambridge university press.

- Garay, L., Font, X., & Corrons, A. (2019). Sustainability-oriented innovation in tourism: An analysis based on the decomposed theory of planned behavior. Journal of Travel Research, 58(4), 622–636. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287518771215

- Gilal, F. G., Zhang, J., Gilal, R. G., & Gilal, N. G. (2018). Linking motivational regulation to brand passion in a moderated model of customer gender and age: An organismic integration theory perspective. Review of Managerial Science, 14(1), 87–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-018-0287-y

- Giovanis, A., Athanasopoulou, P., Assimakopoulos, C., & Sarmaniotis, C. (2019). Adoption of mobile banking services: A comparative analysis of four competing theoretical models. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 37(5), 1165–1189. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-08-2018-0200

- Gupta, A., & Arora, N. (2017a). Consumer adoption of m-banking: A behavioral reasoning theory perspective. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 35(4), 733–747. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-11-2016-0162

- Gupta, A., & Arora, N. (2017b). Understanding determinants and barriers of mobile shopping adoption using behavioral reasoning theory. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 36(December2016), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.12.012

- Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., Anderson, R., & Tatham, R. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7thed). Pearson Education.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Hair, J. F. J., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

- Hanafizadeh, P., Keating, B. W., & Khedmatgozar, H. R. (2014). A systematic review of internet banking adoption. Telematics and Informatics, 31(3), 492–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2013.04.003

- Harman, H. (1976). Modern factor analysis. University of Chicago Press.

- Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management and Data Systems, 116(1), 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. International Marketing Review, 33(3), 405–431. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-09-2014-0304

- Hopalı, E., Vayvay, Ö., Kalender, Z. T., Turhan, D., & Aysuna, C. (2022). How do mobile wallets improve sustainability in payment services? A comprehensive literature review. Sustainability, 14(24), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416541

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit Indices in Covariance Structure Modeling: Sensitivity to Underparameterized Model Misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424–453. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424

- Kahle, L. R., Beatty, S. E., & Pamela, H. (1986). Alternative measurement approaches to consumer values: The List of Values (LOV) and Values and Life Style (VALS). Journal of Consumer Research, 13, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1086/209079

- Kapoor, A., Sindwani, R., Goel, M., & Shankar, A. (2022). Mobile wallet adoption intention amid COVID-19 pandemic outbreak: A novel conceptual framework. Computers and Industrial Engineering, 172, 108646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2022.108646

- Kaur, P., Dhir, A., Singh, N., Sahu, G., & Almotairi, M. (2020). An innovation resistance theory perspective on mobile payment solutions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 55, 102059. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JRETCONSER.2020.102059