Abstract

The purpose of this study is to investigate whether workplace incivility explains the phenomenon of employee silence behavior in the hospitality sector and how job embeddedness and power distance mediate and moderate this relationship. Data were collected from 359 frontline staff at several hotels and restaurants in Jakarta, Indonesia. The data were analyzed using moderating mediation procedures using the Macro Process. Workplace incivility was negatively related to job embeddedness and positively to employee silence behavior. Job embeddedness was positively associated with employee silence and mediates the relationship between workplace incivility and employee silence. Finally, power distance is directly related to employee silence and moderates the relationship between workplace incivility and employee silence. Hence, the relationship between workplace incivility and employee silence was stronger among employees who perceived higher power distance. The results of this study could be used to guide the management of the hospitality industry. In particular, disrespectful treatment from seniors or supervisors perceived by employees triggers a decrease in job embeddedness and increases silent behavior. Management needs to implement several policies to prevent uncivil actions in the workplace. Moreover, the present study suggests that organizational managers applied special incentives for employees to actively share their information, ideas, and opinions to stimulate employee voice.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The present study adds to the existing knowledge of the consequences of workplace incivility on job embeddedness and employee silence. This study advances our understanding of how workplace incivility results in poor job embeddedness and increases silent behavior among employees. The present study also contributes to the literature by identifying the mediating moderating mechanism of workplace incivility and employee silence via job embeddedness and power distance.

1. Introduction

Employee silence is a universal phenomenon in modern organizations (Morrison, Citation2014), namely when employees are not willing to speak up, withhold important information, and avoid giving advice and opinions (Lam & Xu, Citation2019; Morrison, Citation2014; Tangirala & Ramanujam, Citation2008a; Van Dyne & LePine, Citation1998). The consequences of employee silence lead to the company’s failure to detect threats, reducing the company’s ability to innovate and perform (Brinsfield, Citation2013; Madrid et al., Citation2015; Maqbool et al., Citation2019). At the individual level, employee silence has consequences on burnout, job attitude, engagement, performance, innovative work behavior, and organizational citizenship (Chou & Chang, Citation2021; Hao et al., Citation2022; Jha et al., Citation2019; Nazir et al., Citation2021; Srivastava et al., Citation2019). Researchers agree that employee silence should be reduced and instead promote employee voice to increase organizational effectiveness (Jha et al., Citation2019). Despite having adverse consequences for organizations, the issue of employee silence has received less attention than employee voice (Jha et al., Citation2019; Lam & Xu, Citation2019; Morrison, Citation2014). Thus, we respond to the call to explore the potential factors affecting employee silence.

Previous studies have explored the antecedents of silent behavior, including individual level factors, such as personality traits, low job satisfaction, commitment, emotional intelligence, stress, and trust (Boadi et al., Citation2020; Chou & Chang, Citation2020; Madrid et al., Citation2015; Srivastava et al., Citation2019; Wu et al., Citation2018); and organizational context factors, including norms, culture, policies, politics, and leadership styles (Brinsfield, Citation2013; Hassan et al., Citation2019; Wu et al., Citation2022). More recent studies identified a third situational factor, such as workplace bullying (Rai & Agarwal, Citation2018), abusive supervision (Lam & Xu, Citation2019; Wang et al., Citation2020), workplace ostracism (Yao et al., Citation2022), workplace incivility (Khan et al., Citation2022). Such differing perspectives in previous research provide an opportunity to investigate the antecedents of employee silence using individual, organizational, and situational factors that have attracted much interest from researchers in the last five years.

The present study aims to fill the literature gap by exploring the three perspectives (individual, organizational contextual, and situational) to explain employee silence. We propose workplace incivility (situational), job embeddedness (individual level), and power distance as subculture dimensions representing organizational contextual factors as a combination of antecedents of employee silence in non-western countries. First, existing research has taken various forms of mistreatment in the workplace, including workplace bullying, ostracism, and abusive supervision, as an antecedent of employee silence (Lam & Xu, Citation2019; Rai & Agarwal, Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2020). Recently, Khan et al. (Citation2022) tested the relationship between workplace incivility and employee silence. However, in contrast to Khan et al. (Citation2022), who confirmed the reciprocal relationship between workplace incivility and deviant silence moderated by moral attentiveness, our study proposed power distance as a boundary condition. Thus, we offer a different perspective to studying silent behavior by integrating power distance (Hofstede et al., Citation2005) as a sub-national culture that influences management behavior in a country. Indonesia is a country that scores high on scales of power distance, the defining feature of which is “the existence of a hierarchy, inequality of rights between power holders and non-power holders, inaccessible superiors, directive leaders, management control and delegation” (Hofstede et al., Citation2005). Under these conditions, front-line employees tend not to have the courage to report uncivil incidents to their superiors; thus, is relevant for the current study.

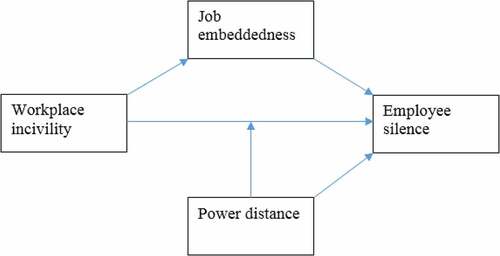

Second, the present study responds to Lam and Xu’s (Citation2019) call to explore the direct relationship between power distance and employee silence. Drawing on the conservation of resources (COR, Hobfoll, Citation2001) theory and approach–inhibition theory of power (Keltner et al., Citation2003), we offer new knowledge to study silent behavior from the perspective of organizational culture (e.g., power distance). Third, taking a step further, we study the relationship between workplace incivility and employee silence via job embeddedness. Our proposed model (see, Figure ) provides preliminary empirical evidence regarding the relationship between workplace incivility and job embeddedness and the link between job embeddedness and employee silence. Prior research has studied the consequences of workplace incivility on employee attitudes and behavior, including work engagement, job performance, turnover intention, and emotional exhaustion (Alola et al., Citation2019; Hur et al., Citation2016; Namin et al., Citation2022; Rhee et al., Citation2017; Tricahyadinata et al., Citation2020; Ugwu et al., Citation2022; Wang & Chen, Citation2020). To the best of our knowledge, no studies specifically examine the relationship between workplace incivility and job embeddedness. Thus, the present study adds significant insight to the job embeddedness literature.

Moreover, previous studies have mostly linked job embeddedness with employee voice (Tan et al., Citation2019; Zhou et al., Citation2021), while the present study proposes job embeddedness as a negative predictor of employee silence. Incorporating individual, contextual/organizational, and situational can help us better understand the silent employee phenomenon. Since employee silence can reduce organizational effectiveness, understanding it from these three perspectives is an essential insight for human resource practitioners who operate in countries with high power distance characteristics, especially in Asia.

2. Theoretical framework and hypotheses

Our proposed model is based on the conservation of resources (COR, Hobfoll, Citation2001) theory to explain the relationship between workplace incivility, job embeddedness, employee silence, and the role of power distance as a boundary condition. COR assumes that each individual will try to find, obtain, and protect their resources within the organization. In the COR perspective, resources can be in the form of all things related to work, including, in this case, financial resources, personal, favorable conditions, and even energy. Workplace incivility as a situational factor; the results of social interactions within organizations are potential antecedents of personal resources, especially emotions. Using the COR argument, individuals will survive when job resources are available (e.g., treated with respect). Conversely, individuals treated disrespectfully tend to avoid direct interaction with the perpetrator (Peltokorpi, Citation2019), as well as reduce social cohesion (Reisig & Cancino, Citation2004). Similarly, workplace incivility can deplete emotional resources, including emotional exhaustion, anger, dissatisfaction, disengagement, and psychological distress (Chen & Wang, Citation2019; Cortina et al., Citation2001; Hobfoll, Citation2001; Liu et al., Citation2020).

Second, we also use COR theory to explain the relationship between workplace incivility and employee silence. Following the study of Wang et al. (Citation2020), COR is a logical framework to explain how individuals intend to keep silent due to disrespectful treatment from supervisors. Using the COR argument (Hobfoll, Citation2001), employees acting quiet are likely to protect their resources rather than direct retaliation. However, silent behavior can also be a defensive mechanism (Lam & Xu, Citation2019) by holding vital information related to work (Wang et al., Citation2020). In the same vein, employees’ perceived uncivil behavior tends to avoid their voices (Achmadi et al., Citation2022; Madhan et al., Citation2022) and keep silent (Mao et al., Citation2019). Silence behavior is a form of defensive behavior (Lam & Xu, Citation2019) by withholding vital information related to work (Wang et al., Citation2020). In other words, employee silence may be a covert retaliation or avoidance-coping behavior (Wang et al., Citation2020) that employees do to the organization for the disrespectful treatment they receive from coworkers or supervisors.

Next, we use the approach–inhibition theory of power (Keltner et al., Citation2003) to explain the distinguishing factor of organizational culture (power distance) as a boundary condition of workplace incivility and employee silence relationship. The main characteristic of power distance is power imbalance (Hofstede et al., Citation2005), where individuals with higher power have a more incredible opportunity to increase their positive emotions. In contrast, individuals who have lower power focus more on threats and efforts to avoid them, including silent behavior (Lam & Xu, Citation2019). In addition, the status and power differences has become a central issue in explaining uncivil behavior (Cortina & Magley, Citation2009; Cortina et al., Citation2001; Pearson & Porath, Citation2005; C. L. Porath & Pearson, Citation2012) and employee silence (Lam & Xu, Citation2019).

2.1. Workplace incivility, job embeddedness, and employee silence

Job embeddedness as an individual’s strength to survive in the organization; is a combination of individuals’ assessments of their compatibility with the organization (fit), the power of relationships and social interactions (links), and employees’ objective assessments of the resources lost (material and non-material) when they decide to leave the organization. In the job embeddedness context, we postulated that the resource loss arising from workplace incivility might contribute to reducing “links, fit” and increasing “sacrifice” as a major component of job embeddedness (Mitchell et al., Citation2001). Using the COR theory, we postulate that incivility will reduce job embeddedness because employees will reduce links (take distance from perpetrators); they will facilitate direct contact with perpetrators and lose interest in engaging with social relationships at work, as well as reduce social cohesion (Reisig & Cancino, Citation2004) and interaction avoidance (Peltokorpi, Citation2019). In the same vein, individuals who receive inappropriate/disrespectful treatment in their work environment experience disturbances in social relations (Hobfoll, Citation2001). In other words, individuals who experiencing as a victim of uncivil behavior will question whether they are “fit” with the current organizational environment. As a final result, the combination of low link, fit, and high sacrifice as the overall concept of job embeddedness (Mitchell et al., Citation2001) will weaken along with high workplace incivility. Thus, we suspect that workplace incivility is directly and negatively related to job embeddedness. Therefore, the next proposed hypothesis is as follows.

H1. Workplace incivility is negatively related to employee job embeddedness.

As opposed to employee voice which is an employee’s proactive action to convey ideas and opinions (Lam & Xu, Citation2019; Van Dyne & LePine, Citation1998), employee silence refers to employees’ reluctance to speak their minds to the organization (Elizabeth W Morrison et al., Citation2015). Silent behavior is a form of defensive behavior (Lam & Xu, Citation2019) by withholding information related to work (Wang et al., Citation2020). Employee silence is one of the most common deviant behaviors in organizational behavior literature (Khan et al., Citation2022). Drawing COR argument (Hobfoll, Citation2001), employees act quietly to preserve their resources rather than direct retaliation. Employees who experience being victims of uncivil from senior coworkers or supervisors depleted their emotional resources (e.g., anger, exhaustion). Thus, silent behavior can be an avoidance-oriented coping strategy (Lam & Xu, Citation2019) by distancing themselves from uncivil actors to maintain their emotional resources. Empirical support has been documented on the relationship between workplace incivility and employee silence. Using samples in various industries in the United States, Khan et al. (Citation2022) found that workplace incivility had a reciprocal relationship with deviance silence. Using a different context, namely abusive supervision, impolite behavior received by employees from their supervisors triggers higher silent behavior (Lam & Xu, Citation2019; C.-C. Wang et al., Citation2020). Moreover, Brinsfield (Citation2013) identified two incidents that most often cause employees to remain silent: when they are mistreated and receive unethical treatment. On the other hand, Achmadi et al. (Citation2022) found that a civility climate can increase proactive employee actions through voice. Thus, our proposed hypothesis:

H2. Workplace incivility is positively related to employee silence.

Employee silence is a deliberate action by employees to withhold meaningful information, issues, and problems that occur in the workplace; including the low interest of employees to provide ideas, suggestions, and questions (Brinsfield, Citation2013; Elizabeth Wolfe Morrison et al., Citation2011; Khalid & Ahmed, Citation2016; Tangirala & Ramanujam, Citation2008a, Citation2008b; Van Dyne et al., Citation2003).In the context of silence, employees do not have communication barriers but intend to hold back their voices. Therefore, the researchers divided the determinants of employee silence: individual level, including motives and personality (e.g., self-esteem, self-efficacy), and the other factors were situational/contextual factors within the organization (policies, norms, climate, and culture). Although the relationship between job embeddedness and employee silence has never been done, in the voice literature, several studies have proven the relationship between the two. For example, Zhou et al. (Citation2021) found a positive relationship between job embeddedness and nurses’ voice behavior using a sample of nurses in China. In the same vein, Tan et al. (Citation2019) partially support the relationship between job embeddedness and voice behavior, especially toward the organization, but not the work unit. In other words, employees with high job embeddedness have a high level of “link” and “fit” with their organization, and consequently, they tend to show more proactive (voice behaviors) by providing various suggestions, ideas, and information for the advancement of their organization. Hence, since job embeddedness has previously been documented to be positively related to employee voice, it is logical to propose negatively associating job embeddedness with employee silence. Thus, we propose the hypothesis is:

H3. Job embeddedness is negatively related to employee silence.

Despite the significance of employee silence for organizations, researchers have paid more attention to silent behavior in the last ten years. However, rather than the concept of voice, studies on the determinants and effects of employee silence still require more empirical evidence (Elizabeth Wolfe Morrison et al., Citation2011; Lam & Xu, Citation2019). As a result, researchers have developed various models to provide a more accurate explanation of the determinants of employee silence. For example, Hassan et al. (Citation2019) examine the indirect relationship of empowering leadership with employee silence through trust, control over work, and organizational identification. Using Self-Determination Theory as a framework, Ju et al. (Citation2019) propose the a process model of empowering leadership, intrinsic motivation, and employee silence. Another study by Srivastava et al. (Citation2019) reported that the relationship between job burnout and employee silence was mediated by emotional intelligence. Rai and Agarwal (Citation2018) found that psychological contract violations mediate the link between workplace bullying and silent employee behavior. A more recent study (Hamstra et al., Citation2021) provides empirical support for the process model, where the manager trait narcissism can influence employee silence through trustworthiness perceptions. Using our previous argument that workplace incivility is a source of stressor that can reduce job embeddedness, low embeddedness can increase the potential for employees to behave in silence. Thus, we propose job embeddedness as an explanatory mechanism to explain the relationship between workplace incivility and employee voice.

H4. Job embeddedness mediates the association of workplace incivility with employee silence.

2.2. The role of organizational power distance

Power distance is a company characteristic that comes from national culture (Hofstede et al., Citation2005). Power distance describes how employees acknowledge the existence of status and power inequality. Therefore, organizations with a high power distance tend to apply more secure communication, where decisions are made based on authority and position; accordingly, employees at the bottom of hierarchies will refrain from speaking out (Lam & Xu, Citation2019). Organizations with high power distance focus more on stability so that voices against authority will be heard less frequently, and therefore, silence and power distance characteristics are interrelated (Elizabeth W Morrison et al., Citation2015). Moreover, in response to Lam and Xu’s (Citation2019) suggestion to explore the direct relationship between power distance and employee silence, we propose a high level of power distance has a positive relationship with employee voice.

H5. Power distance is positively related to employee silence

In addition to the direct effects, we propose the moderating impact of power distance on the relationship between workplace incivility and employee voice. Previous studies have been proved to link power distance to workplace incivility, and employee silence (Cortina & Magley, Citation2009; Cortina et al., Citation2001; Lam & Xu, Citation2019; Pearson & Porath, Citation2005; Porath & Pearson, Citation2012) and more recently several researchers are exploring its role as a boundary condition. For example, Lam and Xu (Citation2019) examined the interaction between power distance and abusive supervisors in influencing employee silence. In other words, the uncivil behavior that employees get from seniors or supervisors will reduce their interactions (Park & Haun, Citation2018; Yue et al., Citation2021); reducing their voice. Using the COR argument, as such, because uncivil’s behavior is senior/supervisor, employees may be silent to avoid confrontation. This defensive silence behavior is because lower-level employees are powerless, primarily in organizations that recognize the unequally distributed power. Thus, workplace incivility can increase employee silence, which is more potent when the power distance belief is high.

H6. Power distance moderates the association of workplace incivility with employee silence

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants and procedure

The study was carried out in two phases, with each stage conducted at different times. The first phase of this study was completed from November to December 2021 in six hotels in Jakarta. After obtaining permits from management, as many as 244 respondents at six hotels filled out a pencil-paper questionnaire, and 127 respondents from two restaurants used an online questionnaire. In Phase 1, respondents were asked to answer biographies, workplace incivility, and sense of power questions. Phase 2 of the study was carried out four weeks after phase 1; respondents were invited back to answer questions on silence behavior and job embeddedness. After discarding 12 incomplete questionnaires, 359 were used in this study.

The respondents included 172 males (47.91 percent) and 187 females (52.09 percent). The average age of the respondents was 26 years, with minimum and maximum periods of 20 and 49 years, respectively. The educational background of the respondents was as follows: 171 had a senior high school (47.63 percent), 88 had diplomas (24.51 percent), and bachelor’s degrees (25.63 percent). Furthermore, 85.71 percent of respondents (156 respondents) had an employment tenure of under one year, 42.06 percent had worked between 1–3 years, and 30.92 percent had worked more than three years. Finally, 67.69 percent of respondents were single, while 32.31 percent were married.

3.2. Measurement

The questions measuring the variables used in this study were based on well-established measurements from previous research. Respondents were asked to give a rating on a 5-Likert-type scale (1 = never to 5 = very often). Workplace incivility was measured using seven items from the workplace incivility scale (Cortina et al., Citation2001). The statement item begins with the sentences “during the past year … … … .your senior coworker/supervisor put you down or was condescending to you” and “your senior/supervisor made a demeaning or derogatory remark about you.” In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was .86.

We use a 5-item scale developed by Tangirala and Ramanujam (Citation2008a). This scale was also used by Wang et al. (Citation2020) to measure employee silence. Example item “although you had ideas for improving patient safety in your [workgroup], you did not speak up.” The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.77, lower than the study of Wang et al. (Citation2020) of .95. To measure job embeddedness, we adapted a seven-item scale from the global job embeddedness scale (Crossley et al., Citation2007). An example of a specific item was “I feel attached to this organization.” The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .91.

Power distance was measured using the five-item Hofstede’s culture sub-scale (Yoo et al., Citation2011). Some typical examples of items included “People in higher positions should not ask for the opinions of people in lower positions too frequently” and “People in higher positions should avoid social interaction with people in lower positions.” The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .89.

3.3. Control variables and common method bias

Since workplace incivility, employee silence, and job embeddedness are related to biographic characteristics (Cahyadi et al., Citation2021; Cortina et al., Citation2001; Marasi et al., Citation2016; Ng & Feldman, Citation2010), we controlled for age, tenure, education, marital status, and gender. Thus, the biographic was included in the model as a control variable. Furthermore, because the data was obtained from one source (employees), we took several steps to minimize the common method variance (CMV). First, the questionnaire was designed anonymously and voluntarily to maximize the objectivity of respondents’ answers. Second, we used a full collinearity technique with PLS-SEM to detect CMV (Kock, Citation2017). Table shows that none of the items has a variance inflation factor (VIF) > 3.3, as recommended by Kock (Citation2017); thus, we can be sure that CMV is not a severe problem in the data we use. Moreover, construct validity and reliability, as shown in Table , indicates that all constructs meet the convergent validity requirements (CR > .70 and AVE > .50) according to the recommendations of Hair et al. (Citation2017). Table .

Table 1. Respondent characteristics

Table 2. Measurement model evaluation

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive statistics

Table shows the means, standard deviation, and correlation between variables in this study. In general, the average rating by respondents is at a moderate level (greater than the median score of 2.5). Workplace incivility had a negative correlation with job embeddedness (r = −.28, p < .01) and a positive correlation with employee silence (r = .32, p < .01). Moreover, job embeddedness has a negative relationship with employee silence (r = −.23, p < .01).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics and correlation

4.2. Hypothesis testing

In this study, we employed a hierarchical regression analysis (HRA) using macro PROCESS version 4.0 for SPSS (Model 5) developed by Hayes (Citation2017) to test the hypotheses. As shown in Table , all five control variables are not significantly related to job embeddedness and employee silence. Hypothesis 1 states that workplace incivility is negatively related to job embeddedness, and this hypothesis is supported. As shown in Table , workplace incivility significantly affected job embeddedness (b = −.26, SE = .05, p < .01), supporting H1. Workplace incivility was also positively and significantly associated with employee silence (b = .25, p < .01), supporting H2. The results of testing hypothesis 3 show that job embeddedness is negatively and significantly related to employee silence (b = −.15, p < .01), thus, H3 was supported. Furthermore, we find that power distance affects employee silence positively (β = .13, p < .01), thus, H4 was supported.

Table 4. Regression results

Mediation hypothesis. Hypothesis 5 examines the mediating role of job embeddedness on the relationship between workplace incivility and employee silence. Table shows that the indirect effects model is supported (b = .04, LLCI = .01, ULCI = .07). Based on bootstrapping estimation show that proves the significance of the indirect effect. Therefore, H5 was supported.

Table 5. Mediation and moderation analysis

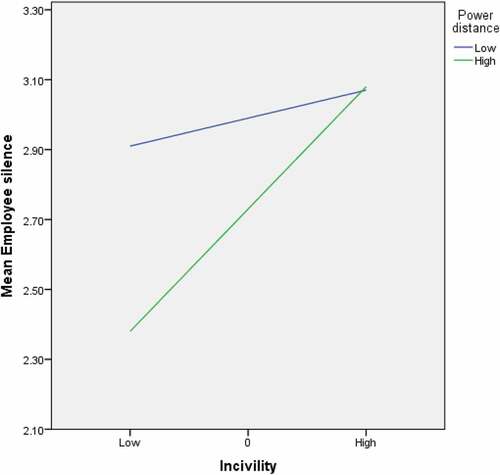

Moderation hypothesis. The results of the analysis showed that the interaction of workplace incivility x power distance was statistically significant with a positive direction (b = .17, p < .01). The significance of the interaction variables indicates that power distance plays a moderating role in the relationship between workplace incivility and employee silence. The conditional effect of workplace incivility on employee silence is also supported by bootstrap analysis. As shown in Table , the impact of workplace incivility is only significant when the power distance is at the average and high levels and not at the low level.

Moreover, Table and Figure illustrates the effect of workplace incivility on employee silence based on the value of power distance orientation. The impact of workplace incivility on employee silence rises from .25 to .41 when power distance increases from low to high. In contrast to interaction analysis, this comparative result indicates that higher power distance orientation increases the effect of workplace incivility on employee silence.

5. Discussion

This study examines the moderation and mediation model of workplace incivility, job embeddedness, and employee silence through the lens of power distance. In general, present studies confirm that workplace incivility is negatively related to job embeddedness and positively related to employee silence. Power distance as a sub-national culture (Hofstede et al., Citation2005) moderates the relationship between workplace incivility and employee silence. Moreover, the indirect effect of workplace incivility on employee silence has been confirmed mediated by job embeddedness. Our study supports the COR theory to explain the relationship between workplace incivility and employee silence. Moreover, we also support the approach–inhibition theory of power (Keltner et al., Citation2003) to explain the distinguishing factor of organizational culture (power distance) as a boundary condition of workplace incivility and employee silence relationship.

5.1. Theoretical implications

The present study provides a theoretical contribution to the literature on employee silence behavior and job embeddedness. First, consistent with previous studies (Khan et al., Citation2022; Lam & Xu, Citation2019; Wang et al., Citation2020), our results also found a positive effect of workplace incivility on employee silence. However, in contrast to Lam and Xu (Citation2019) and Wang et al. (Citation2020), who puts uncivil behavior in the form of abusive supervisor as an antecedent of employee silence, our study examine the uncivil behavior in a broader context (senior coworker and supervisor) as the cause of employees tending to behave quietly at work. Our findings show that employees with uncivil experiences from senior coworkers/supervisors tend to be more silent at work than their non-uncivil counterparts. Employees’ perceived uncivil behavior at a high level causes them to avoid their voices in the form of constructive suggestions (Achmadi et al., Citation2022; Madhan et al., Citation2022) and keep silent (Mao et al., Citation2019). Moreover, we also support the COR argument (Hobfoll, Citation2001) that employees act quietly to preserve their resources rather than direct retaliation. Silent behavior is a form of defensive behavior (Lam & Xu, Citation2019) by withholding vital information related to work (Wang et al., Citation2020).

Second, the present study is among the few to advance understanding the antecedents of job embeddedness regarding perceived incivility from senior coworkers/supervisors. While prior research links workplace incivility to various employee attitudes and behaviors, including work engagement (Tricahyadinata et al., Citation2020; Ugwu et al., Citation2022; Wang & Chen, Citation2020), job performance (Rhee et al., Citation2017; Wang & Chen, Citation2020), turnover intention (Namin et al., Citation2022; Tricahyadinata et al., Citation2020), and emotional exhaustion (Alola et al., Citation2019; Hur et al., Citation2015), our study extends this works by testing workplace incivility as antecedents of job embeddedness.

Third, our study fulfills Lam and Xu’s (Citation2019) call to investigate silence behavior using a cultural perspective, namely power distance. The present study strengthens and expands Lam and Xu (Citation2019) work, which explores the interaction of power distance and uncivil behavior in different contexts (abusive supervisors) in influencing employee silence. Moreover, our study also offers a different perspective from Khan et al. (Citation2022), who proved the moderating effect of moral attentiveness on the relationship between workplace incivility and employee silence. Thus, for employees who work in organizations that have cultural characteristics with high power distance, such as companies in Asia in general (Hofstede et al., Citation2005), the tendency to provide suggestions and input to the organization will tend to be low. Since high power distance are always related to power imbalance (Hofstede et al., Citation2005; Lam & Xu, Citation2019; Elizabeth W Elizabeth W Morrison et al., Citation2015), the employees at low levels do not have the power to change the situation; accordingly, they will avoid being actively involved in constructive voice. Next, our results suggest that power distance plays a vital role in the silence behavior phenomenon. Moderation test results demonstrate that the higher experiences of uncivil behavior have consequences on higher intention to silence, especially in a high power distance environment. The present study explains how power distance may exacerbate the effect of workplace incivility on employee silence in the hospitality sector.

Finally, we believe that our study contributes to the complex relationship model between workplace incivility and employee voice. Although existing studies have paid attention to the issue of power imbalance and power distance to study the impact of various forms of uncivil behaviors, including rudeness and abusive supervision (Cortina & Magley, Citation2009; Cortina et al., Citation2001; Hershcovis et al., Citation2017; Lam & Xu, Citation2019; Pearson & Porath, Citation2005; Porath & Pearson, Citation2012), our results show that job embeddedness partially mediates the relationship between workplace incivility and employees’ silence behavior. This mediation model supports the idea of using job embeddedness to explain how perceived rudeness in the workplace is related to employee silence. In other words, employees who receive disrespectful treatment from senior coworkers/supervisors will reduce their interactions by avoiding them (Park & Haun, Citation2018; Yue et al., Citation2021); which in turn can reduce their involvement to be actively involved in providing information and advice related to work-related issues. Although existing studies have documented the relationship between job embeddedness and voice behavior (Tan et al., Citation2019; Zhou et al., Citation2021), our finding extends previous research by identifying job embeddedness as an essential mechanism in determining the continued effect of workplace incivility on employee voice.

5.2. Practical implications

Apart from having important theoretical contributions to workplace incivility and employee voice literature, the results of our study also provide several implications for management, particularly in the hospitality sector. Our findings show that workplace incivility results in decreased job embeddedness, which will impair employees’ silence. This finding suggests that organizational managers should take various ways to prevent all forms of workplace incivility. First, management must be more sensitive about multiple forms of uncivil behavior, including discourteous, unfair, and disrespectful behavior for others (Pearson et al., Citation2001) that originates from the work environment (senior coworkers and supervisors). Thus, monitoring efforts need to be carried out to prevent incivility from developing and becoming a culture in the organization. In other words, organizations need to reformulate organizational cultural values and socialize them through official ethical standards. Especially for supervisors involved in uncivil behavior, the management needs to provide leadership training by promoting more effective communication skills and reducing their hostile behavior.

Second, organizations must provide procedures for reporting mistreatment in the workplace. However, this can only successfully reduce uncivil behavior if a company has explicitly disseminated formal rules to all employees regarding ethical standards of conduct, including the prohibition of specific forms of behavior categorized as workplace mistreatment. Therefore, it is essential to disseminate and maintain of workplace mistreatment (Porath et al., Citation2012) to prevent further adverse effects. We also strongly argue that Indonesia is a country that inherently prioritizes politeness in all interactions (including at work) so that all employees are treated equally and fairly in the workplace.

Finally, our findings also show that workplace incivility can increase employee silence in the workplace. This suggests to managers in the hospitality sector that it is essential for them to maintain an employee voice as a strategy to understand various problems in the work environment. As efforts to encourage employee voice are hindered by power distance, companies must create a civility climate more likely to allow employees to voice their voices freely. For example, managers can allow employees to raise complaints and listen to employees’ voices through non-formal channels (e.g., in a lunch meeting). Moreover, HR management can design special incentives for employees who want to share their information and opinions in the organization to stimulate employee voice.

5.3. Limitations

The present study has several limitations that should be noted for future studies. First, the data we collect comes from Jakarta’s hospitality industry (hotels and restaurants); hence, these findings may not be generalized to other sectors. We highly recommend future researchers expand the study area to several different industries and cultures to broaden the scope of generalization. Second, although the sampling design uses a time-lag approach for testing the mediating effect (Law et al., Citation2016), causality inferences still cannot be made. Thus, future research can replicate this study using a longitudinal design to allow for more robust causal inferences. Third, the incivility studied in this study is sourced from senior coworkers and supervisors and ignores customer incivility, which is also dominantly studied in the hospitality sector (Boukis et al., Citation2020; Ugwu et al., Citation2022; Wang & Chen, Citation2020). We invite future studies to replicate this study by considering customer incivility as an antecedent of job embeddedness and employee voice. Moreover, the handling of common method bias has been carried out through a statistical approach (full collinearity technique, Kock, Citation2017); however, several other controls can be considered by future researchers. In line with the recommendations of several authors (Kock, Citation2017; Podsakoff, Citation2012), control over the procedure can be considered, for example, by mixing Likert 5 and Likert 7 in the questionnaire.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Achmadi, A., Hendryadi, H., Siregar, A. O., & Hadmar, A. S. (2022). How can a leader’s humility enhance civility climate and employee voice in a competitive environment? Journal of Management Development, 41(4), 257–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-11-2021-0297

- Alola, U. V., Olugbade, O. A., Avci, T., & Öztüren, A. (2019). Customer incivility and employees’ outcomes in the hotel: Testing the mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Tourism Management Perspectives, 29, 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2018.10.004

- Boadi, E. A., He, Z., Boadi, E. K., Antwi, S., & Say, J. (2020). Customer value co-creation and employee silence: Emotional intelligence as explanatory mechanism. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 91, 102646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102646

- Boukis, A., Koritos, C., Daunt, K. L., & Papastathopoulos, A. (2020). Effects of customer incivility on frontline employees and the moderating role of supervisor leadership style. Tourism Management, 77, 103997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.103997

- Brinsfield, C. T. (2013). Employee silence motives: Investigation of dimensionality and development of measures. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(5), 671–697. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1829

- Cahyadi, A., Hendryadi, H., & Mappadang, A. (2021). Workplace and classroom incivility and learning engagement: The moderating role of locus of control. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 17(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-021-00071-z

- Chen, H.-T., & Wang, C.-H. (2019). Incivility, satisfaction and turnover intention of tourist hotel chefs. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(5), 2034–2053. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-02-2018-0164

- Chou, S. Y., & Chang, T. (2020). Employee silence and silence antecedents: A theoretical classification. International Journal of Business Communication, 57(3), 401–426. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488417703301

- Chou, S. Y., & Chang, T. (2021). Feeling capable and worthy? Impact of employee silence on self-concept: Mediating role of organizational citizenship behaviors. Psychological Reports, 124(1), 266–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294120901845

- Cortina, L., & Magley, V. (2009). Patterns and profiles of response to incivility in the workplace. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14(3), 272–288. Educational Publishing Foundation. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014934

- Cortina, L. M., Magley, V. J., Williams, J. H., & Langhout, R. D. (2001). Incivility in the workplace: Incidence and impact. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 6(1), 64–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.6.1.64

- Crossley, C. D., Bennett, R. J., Jex, S. M., & Burnfield, J. L. (2007). Development of a global measure of job embeddedness and integration into a traditional model of voluntary turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 1031–1042. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.1031

- Hair, J., Hollingsworth, C. L., Randolph, A. B., & Chong, A. Y. L. (2017). An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 117(3), 442–458. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-04-2016-0130

- Hamstra, M. R. W., Schreurs, B., Jawahar, I. M. (Jim), Laurijssen, L. M., & Hünermund, P. (2021). Manager narcissism and employee silence: A socio‐analytic theory perspective. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 94(1), 29–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12337

- Hao, L., Zhu, H., He, Y., Duan, J., Zhao, T., & Meng, H. (2022). When is silence golden? A meta-analysis on antecedents and outcomes of employee silence. Journal of Business and Psychology, 37(5), 1039–1063. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-021-09788-7

- Hassan, S., DeHart‐Davis, L., & Jiang, Z. (2019). How empowering leadership reduces employee silence in public organizations. Public Administration, 97(1), 116–131. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12571

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approac. Guilford publications.

- Hershcovis, M. S., Ogunfowora, B., Reich, T. C., & Christie, A. M. (2017). Targeted workplace incivility: The roles of belongingness, embarrassment, and power. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(7), 1057–1075. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2183

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2005). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (2nd) ed.). Mcgraw-hill.

- Hur, W.-M., Kim, B.-S., & Park, S.-J. (2015). The relationship between coworker incivility, emotional exhaustion, and organizational outcomes: the mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing & Service Industries, 25(6), 701–712. https://doi.org/10.1002/hfm.20587

- Hur, W.-M., Moon, T., & Jun, J.-K. (2016). The effect of workplace incivility on service employee creativity: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion and intrinsic motivation. Journal of Services Marketing, 30(3), 302–315. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-10-2014-0342

- Jha, N., Potnuru, R. K. G., Sareen, P., & Shaju, S. (2019). Employee voice, engagement and organizational effectiveness: A mediated model. European Journal of Training and Development, 43(7/8), 699–718. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-10-2018-0097

- Ju, D., Ma, L., Ren, R., & Zhang, Y. (2019). Empowered to break the silence: Applying self-determination theory to employee silence. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00485

- Keltner, D., Gruenfeld, D. H., & Anderson, C. (2003). Power, approach, and inhibition. Psychological review. Psychological Review, 110(2), 265–284. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-295X.110.2.265

- Khalid, J., & Ahmed, J. (2016). Perceived organizational politics and employee silence: Supervisor trust as a moderator. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 21(2), 174–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2015.1092279

- Khan, R., Murtaza, G., Neveu, J. P., & Newman, A. (2022). Reciprocal relationship between workplace incivility and deviant silence—The moderating role of moral attentiveness. Applied Psychology, 71(1), 174–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12316

- Kock, N. (2017). Common method bias: A full collinearity assessment method for PLS-SEM BT - partial least squares path modeling: Basic concepts, methodological issues and applications. In H. Latan & R. Noonan (Eds.), Partial Least Squares Path Modeling (pp. 245–257). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64069-3_11

- Lam, L. W., & Xu, A. J. (2019). Power imbalance and employee silence: The role of abusive leadership, power distance orientation, and perceived organisational politics. Applied Psychology, 68(3), 513–546. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12170

- Law, K. S., Wong, C.-S., Yan, M., & Huang, G. (2016). Asian researchers should be more critical: The example of testing mediators using time-lagged data. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 33(2), 319–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-015-9453-9

- Liu, P., Xiao, C., He, J., Wang, X., & Li, A. (2020). Experienced workplace incivility, anger, guilt, and family satisfaction: The double-edged effect of narcissism. Personality and Individual Differences, 154, 109642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109642

- Madhan, K., Shagirbasha, S., & Iqbal, J. (2022). Does incivility in quick service restaurants suppress the voice of employee? A moderated mediation model. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 103, 103204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2022.103204

- Madrid, H. P., Patterson, M. G., & Leiva, P. I. (2015). Negative core affect and employee silence: How differences in activation, cognitive rumination, and problem-solving demands matter. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(6), 1887–1898. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039380

- Mao, C., Chang, C.-H., Johnson, R. E., & Sun, J. (2019). Incivility and employee performance, citizenship, and counterproductive behaviors: Implications of the social context. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24(2), 213–227. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000108

- Maqbool, S., Černe, M., & Bortoluzzi, G. (2019). Micro-foundations of innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 22(1), 125–145. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-01-2018-0013

- Marasi, S., Cox, S. S., & Bennett, R. J. (2016). Job embeddedness: Is it always a good thing? Journal of Managerial Psychology, 31(1), 141–153. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-05-2013-0150

- Mitchell, T. R., Holtom, B. C., Lee, T. W., Sablynski, C. J., & Erez, M. (2001). Why people stay: Using job embeddedness to predict voluntary turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 44(6), 1102–1121. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069391

- Morrison, E. W. (2014). Employee voice and silence. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 173–197. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091328

- Morrison, E. W., See, K. E., & Pan, C. (2015). An approach-inhibition model of employee silence: The joint effects of personal sense of power and target openness. Personnel Psychology, 68(3), 547–580. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12087

- Morrison, E. W., Wheeler-Smith, S. L., & Kamdar, D. (2011). Speaking up in groups: A cross-level study of group voice climate and voice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(1), 183–191. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020744

- Namin, B. H., Øgaard, T., & Røislien, J. (2022). Workplace incivility and turnover intention in organizations: A meta-analytic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010025

- Nazir, S., Shafi, A., Asadullah, M. A., Qun, W., & Khadim, S. (2021). Linking paternalistic leadership to follower’s innovative work behavior: The influence of leader–member exchange and employee voice. European Journal of Innovation Management, 24(4), 1354–1378. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-01-2020-0005

- Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2010). The impact of job embeddedness on innovation-related behaviors. Human Resource Management, 49(6), 1067–1087. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20390

- Park, Y., & Haun, V. C. (2018). The long arm of email incivility: Transmitted stress to the partner and partner work withdrawal. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(10), 1268–1282. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2289

- Pearson, C. M., Andersson, L. M., & Wegner, J. W. (2001). When workers flout convention: A study of workplace incivility. Human Relations, 54(11), 1387–1419. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267015411001

- Pearson, C. M., & Porath, C. L. (2005). On the nature, consequences and remedies of workplace incivility: no time for “nice”? Think again. Academy of Management Perspectives, 19(1), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2005.15841946

- Peltokorpi, V. (2019). Abusive supervision and emotional exhaustion: The moderating role of power distance orientation and the mediating role of interaction avoidance. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 57(3), 251–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12188

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

- Porath, C. L., & Pearson, C. M. (2012). Emotional and behavioral responses to workplace incivility and the impact of hierarchical status. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(S1), E326–E357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.01020.x

- Porath, C., Spreitzer, G., Gibson, C., & Garnett, F. G. (2012). Thriving at work: Toward its measurement, construct validation, and theoretical refinement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(2), 250–275. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.756

- Rai, A., & Agarwal, U. A. (2018). Workplace bullying and employee silence. Personnel Review, 47(1), 226–256. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-03-2017-0071

- Reisig, M. D., & Cancino, J. M. (2004). Incivilities in nonmetropolitan communities: The effects of structural constraints, social conditions, and crime. Journal of Criminal Justice, 32(1), 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2003.10.002

- Rhee, S.-Y., Hur, W.-M., & Kim, M. (2017). The relationship of coworker incivility to job performance and the moderating role of self-efficacy and compassion at work: The job demands-resources (jd-r) approach. Journal of Business and Psychology, 32(6), 711–726. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-016-9469-2

- Srivastava, S., Jain, A. K., & Sullivan, S. (2019). Employee silence and burnout in India: The mediating role of emotional intelligence. Personnel Review, 48(4), 1045–1060. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-03-2018-0104

- Tangirala, S., & Ramanujam, R. (2008a). Employee silence on critical work issues: The cross level effects of procedural justice climate. Personnel Psychology, 61(1), 37–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.00105.x

- Tangirala, S., & Ramanujam, R. (2008b). Exploring nonlinearity in employee voice: The effects of personal control and organizational identification. Academy of Management Journal, 51(6), 1189–1203. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2008.35732719

- Tan, A. J. M., Loi, R., Lam, L. W., & Zhang, L. L. (2019). Do embedded employees voice more? Personnel Review, 48(3), 824–838. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-05-2017-0150

- Tricahyadinata, I., Hendryadi, S., Zainurossalamia, Z. A., Riadi, S. S., & Riadi, S. S. (2020). Workplace incivility, work engagement, and turnover intentions: Multi-group analysis. Cogent Psychology, 7(1), 1743627. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2020.1743627

- Ugwu, F. O., Onyishi, E. I., Anozie, O. O., & Ugwu, L. E. (2022). Customer incivility and employee work engagement in the hospitality industry: Roles of supervisor positive gossip and workplace friendship prevalence. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 5(3), 515–534. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-06-2020-0113

- Van Dyne, L., Ang, S., & Botero, I. C. (2003). Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs*. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1359–1392. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00384

- Van Dyne, L., & LePine, J. A. (1998). Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Academy of Management Journal, 41(1), 108–119. https://doi.org/10.5465/256902

- Wang, C.-H., & Chen, H.-T. (2020). Relationships among workplace incivility, work engagement and job performance. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 3(4), 415–429. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-09-2019-0105

- Wang, -C.-C., Hsieh, -H.-H., & Wang, Y.-D. (2020). Abusive supervision and employee engagement and satisfaction: The mediating role of employee silence. Personnel Review, 49(9), 1845–1858. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-04-2019-0147

- Wu, M., Peng, Z., & Estay, C. (2018). How role stress mediates the relationship between destructive leadership and employee silence: The moderating role of job complexity. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 12, e19. https://doi.org/10.1017/prp.2018.7

- Wu, M., Wang, R., Estay, C., & Shen, W. (2022). Curvilinear relationship between ambidextrous leadership and employee silence: Mediating effects of role stress and relational energy. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 37(8), 746–764. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-07-2021-0418

- Yao, L., Ayub, A., Ishaq, M., Arif, S., Fatima, T., & Sohail, H. M. (2022). Workplace ostracism and employee silence in service organizations: The moderating role of negative reciprocity beliefs. International Journal of Manpower, 43(6), 1378–1404. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-04-2021-0261

- Yoo, B., Donthu, N., & Lenartowicz, T. (2011). Measuring hofstede’s five dimensions of cultural values at the individual level: Development and validation of CVSCALE. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 23(3–4), 193–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/08961530.2011.578059

- Yue, Y., Nguyen, H., Groth, M., Johnson, A., & Frenkel, S. (2021). When heroes and villains are victims: how different withdrawal strategies moderate the depleting effects of customer incivility on frontline employees. Journal of Service Research, 24(3), 435–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520967994

- Zhou, X., Wu, Z., Liang, D., Jia, R., Wang, M., Chen, C., & Lu, G. (2021). Nurses’ voice behaviour: The influence of humble leadership, affective commitment and job embeddedness in China. Journal of Nursing Management, 29(6), 1603–1612. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13306