Abstract

This is a qualitative study, which aims at developing a framework for entrepreneurship ecosystem for Ghana and other developing countries through the lens or with the application of institutional theory. In all, 61 owner managers were sampled for the study. In addition, 19 institutions were selected for the study. These were institutions that the researchers identified as having activities that were geared towards entrepreneurship capacity building and were willing to participate in the study. The sampling technique adopted was purposive, and the data collection methods were face-to-face interview with respondents and focus groups. The study revealed that there is a need for continuous building of the capacities of owner managers as a way of encouraging them to continuously push for innovative ideas that can be translated into acceptable products. The capacity-building responsibility is not the exclusive preserve of the government but all other institutions that have a stake in entrepreneurship development. However, governments of the developing world need to play a leading role in coordinating and regulating the activities of other stakeholders or institutions that operate at intertwined layers of regulative, normative, and cognitive pillars of an ecosystem.

1. Introduction

The importance of entrepreneurship to the development of economies of both developed and developing countries has widely been recognised by practitioners and researchers (Kayanula & Quartey, Citation2000). It has been argued that the development of entrepreneurship and small businesses has contributed to the assumption of economic leadership of most countries in a wide range of industries (Stokes, Citation1995). Entrepreneurial capitalism is seen as a central mechanism in promoting efficiency, productivity, economic development, and international competitiveness of enterprises (Acquaah, Citation2005). Entrepreneurial stakeholders have recognised the importance of entrepreneurship in contributing to the employment and gross domestic product (GDP) of countries, and developing countries in particular. The United Bank for Africa (UBA) Growing Business Programme studies shows that about 90% of all businesses in Africa fall under the SME sector, and the sector’s contribution to GDP and employment in most African countries is estimated to be about 40% and 70%. Small-scale enterprises make significant contributions to income and employment and have the potential for self-sustaining growth.

Thus, the developmental agenda of developing countries hinges, to a very large extent, on the effective development of entrepreneurship and/or the small business sector. Many studies have considered the role of entrepreneurship in the development of developing economies. Besides, some studies, particularly that of Cao and Shi (Citation2021), on entrepreneurship ecosystem concentrated on some differences between developed and developing economies using factors such as resource scarcities, structural gaps, and institutional voids and was done at the systematic literature review level. However, little attention has been paid to the empirical development of a framework for the entrepreneurship ecosystem for developing countries. It must be emphasized that there are other relevant parties that affect entrepreneurial success (Isenberg 201). However, in developing this framework, the current study empirically focuses on the contributions of four major enterprise-support institutions of higher educational institutions, international organisations, financial institutions, and government institutions. This is explained by the fact that, they feature prominently in the entrepreneurial development process. The role of entrepreneurs and owner managers was also explored in empirically developing the framework for the entrepreneurship ecosystem. This study is further uniquely underpinned by the application of institutional theory.

2. Literature review

Institutional theory has become popular with writers and researchers as they are increasingly utilising the theory as the lens for many areas of research including entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurial firms and small businesses in developing countries face rapid and dramatic shifts in the institutional environment. These shifts present owner managers with challenges as they seek to grow and develop their ventures (Bruton et al., Citation2010). The introduction of institutional theory in this study is very important because it provides an overarching theoretical lens through which organisational strategies (Scott, Citation1994) of enterprise-support institutions and organisational responses of entrepreneurial firms can be illuminated. Thus, institutional theory serves as a guide for explaining the behaviour of small businesses as well as enterprise-support organisations of the government, financial institutions, higher educational institutions, and international organisations in the developing world.

2.1. Institutions defined

It is important to define the fundamental constituents of the theory. This section thus explores the meaning of “institutions” with reference to institutional theory. This understanding will help in finding out the underpinning elements of institutional theory. There is a debate in the literature with regard to the distinction between institutions and organisations. It has been established that there is not a single universally acceptable or agreed definition of the concept of “institution” (Scott, Citation2002). In other words, the term institutions may mean different things in different contexts, and therefore, it is very difficult to pin it down to one unarguable definition. It is therefore, not uncommon to have different definitions and interpretations of the term “institutions” (Hoffman, Citation1999; Japperson, Citation1991; Scott, Citation2002).

Institutions have been defined as “rules, norms, and beliefs that describe reality for organisations, explaining what is and is not, what can be acted upon and what cannot” (Hoffman, Citation1999, p. 351). They are taken-for granted, culturally understandings, which specify and justify social arrangements and behaviours, both formal and informal. Therefore, institutions can be viewed as performance scripts, which provide “stable design for chronically repeated activity sequences,” deviations from which sanctions are imposed (Japperson, Citation1991, p. 145).

According to the key premises of institutional theory, institutions are social structures that have attained a high degree of resilience and they include cultural-cognitive, normative, and regulative components (Scott, Citation2007). These elements together with related activities and other resources bring about stability and make social life meaningful. Even though this definition emphasises stability, some researchers believe that institutions are subject to change processes, both incremental and discontinuous (Scott, Citation2002).

Broadly speaking, the term has been used to refer to the formal set of rules, ex-ante agreements, less formal shared interaction sequences, and taken-for-granted assumptions, which organisations as well as individuals are supposed to follow (Bonckeck & Shepsle, Citation1996; Scott, Citation2007). These take their root from rules, such as regulatory structures, government agencies, laws, courts, professions, scripts, and practices in the societal and cultural domains that exert conformance pressure (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1991). Thus, North (Citation1991) argues that institutions are humanly devised constraints that structure political, economic, and social interaction. They comprise both informal constraints, such as values, norms, sanctions, taboos, customs, traditions, and codes of conduct and formal rules, such as constitutions, laws, economic rules, property rights, and contracts. Examples of informal constraints in the developing world with respect to entrepreneurship development are customs and traditions. The customs and traditions require the entrepreneur or the owner manager to employ extended family members first, even if their skills and/or competences are not enough to perform the job. As an example of formal constraints, the realisation is that the laws, economic rules, property rights, and contracts favour large businesses at the expense of small businesses.

Given this emphasis on regulative and normative aspects within the extant literature, other researchers have looked at “institutions” from another perspective. For example, DiMaggio and Powell (Citation1991) bring their neo-institutionalism to bear on the explanation of institutions. The new institutionalism organisational theory rejects the rational-actor model and is interested in institutions as independent variables, a turn toward cognitive and cultural explanations.

The discussion above of institutions from different perspectives suggests that they create expectations that determine the appropriate actions for organisations and also form the reasons by which laws, rules, and taken-for-granted behavioural expectations appear natural and abiding. Therefore, institutions define in an objective sense what is the appropriate behaviour of organisations and thus any behaviour that is contrary to what has been defined by these institutions is considered inappropriate or unacceptable. It has thus been argued that the institutions set the rules of the game and/or define the way the game is played, whereas the organisations are the players that must play in accordance with the set rules (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983; Scott, Citation2007).

In this study, the institutions are the major enterprise-support organisations, mainly the government agencies, financial institutions, higher educational institutions, and international organisations. These institutions determine the regulative, normative, and cognitive infrastructures for small businesses in developing countries. These institutions set rules for small businesses and small businesses are thus expected to play according to their rules. The building of entrepreneurship capacity is thus dependent on the conformance of small businesses to the rules of these institutions. The conformance is also dependent on how flexible these rules are and the readiness of the entrepreneurs to comply. This calls for collaborative efforts on the part of the institutions and entrepreneurs. At the cognitive level, the development and growth of small businesses, and hence the capacity for entrepreneurship is highly linked to the training and education offerings of these enterprises support institutions. The three pillars of institutional theory and how they apply to the current research are discussed further.

2.2. The pillars of institutional theory and their application in entrepreneurship ecosystem

Institutional theory acknowledges the importance of economic forces and technical imperatives in shaping social and organizational systems. It also seeks to examine the behaviours and preferences of organisations, individuals, and other outside forces (Bruton et al., Citation2010; Dacin et al., Citation2007; Delmar & Shane, Citation2004; Tolbert et al., Citation2011). Institutional theory focuses on the regulatory, social, and cultural influences that bring about survival and legitimacy of an organisation rather than concentrating solely on efficiency seeking behaviour (Scott, Citation2002). The theory emphasizes the environmental factors experienced by an organisation, such as the norms of society, rules, and requirements, which organisations are expected to conform to. This helps in creating legitimacy and support for such organizations (Bruton et al., Citation2010; Carney and Scott, Citation2001; Tolbert et al., Citation2011; Dacin et al., Citation2007).

Institutional theory depends to a very large extent on social constructs to help in defining the structure and processes of organizations. The distinctive and the most basic characteristic of institutional theory is conformity. This conformity is what is used in determining the legitimacy of organizations. The concept of conformity seeks the establishment of “rational myths” in which it is just “rational” that there is the incorporation of certain norms of society, rules, and requirements into missions and goals of organizations (Manolova et al., Citation2008; Welter, Citation2011).

These debates bring to the fore the important role that entrepreneurs and small businesses need to play in developing societies. The Ghanaian society, for example, requires entrepreneurs to contribute, among other things, to the creation of employment for thousands of unemployed people and thus reduce unemployment and poverty. This is very useful in creating legitimacy and support for small businesses. However, small businesses cannot gain the full support of society if their contribution to the growth and development of the economy is infinitesimal. There is a need for building entrepreneurship capacities to propel entrepreneurs and/or owner managers to contribute more to national development. This is what the current study seeks to investigate and to recommend a framework for the building of entrepreneurship capacity with the application of institutional theory.

2.3. The regulative pillar

The regulative pillar takes its roots from the studies in economics and thus represents a rational actor model of behaviour, based on sanctions and conformity. By means of the rules of the game, monitoring and enforcement, institutions guide the behaviour (North, Citation1990; Scott, Citation2001; Tolbert et al., Citation2011; Dacin et al., Citation2007). Thus, Scott (Citation1994) argues that the regulatory dimension of the institutional profile consists of laws, regulations, rules, and government policies in a particular national environment, which promote certain types of behaviour and restrict others. In other words, the regulatory pillar of an institutional system works to give support, incentive, and sanction to organizations and individuals from authoritative bodies, such as a government, which regulates the actions of individuals and organizations (Brandl & Bullinger, Citation2009; Hinnings & Tolbert, Citation2008).

The regulative processes consist of rule-setting, monitoring, and sanctioning activities. The regulative processes involve the capacity to establish rules, inspect, or review others’ conformity to them, and as necessary, manipulate sanctions-reward and punishments-in an attempt to influence future behaviour. These rules and regulations stem primarily from legislation by government and industrial agreements and standards. These legislative instruments provide guidelines for entrepreneurial organisations, particularly new ones. This more often than not results in organisations and individuals complying with laws or may require a reaction if there is a lack of regulation in the region of the entrepreneurial firm (Bruton et al., Citation2010; North, Citation1990).

As stated earlier, the study investigates four major enterprise-support institutions. The institutions identified are governmental institutions, financial institutions, higher educational institutions, and international organisations. These institutions come up with policies and rules that control the activities of small businesses in developing countries. These policies and rules are important in entrepreneurship research because they serve as a guide for the behaviour of entrepreneurs and small businesses (Brandl & Bullinger, Citation2009; Hinnings & Tolbert, Citation2008). In order to ensure effective entrepreneurship capacity building, therefore, small businesses and entrepreneurs should comply with the laws of government agencies as well as the rules and regulations of the other key enterprise-support organisations (Bruton et al., Citation2010). It must be, however, stated that these rules and regulations sometimes not easily complied with as some of them are made without taking into account the needs and the capacity of these small businesses to comply. In other words, policies, rules, and regulations are not necessarily situated in the current reality of small businesses. Some of these rules and regulations are made by these institutions with reference to global business circumstance (Abor & Biekpe, Citation2007; Kayanula & Quartey, Citation2000). Therefore, this study offers a useful contribution to knowledge through an in-depth exploration of the needs of small businesses as well as offerings of enterprise-support institutions in portraying a holistic understanding of the macro-level dimensions of capacity-building activities for enterprise development in Ghana.

2.4. The normative pillar

The normative pillar represents models of organisational and individual behaviour based on obligatory dimensions of social, professional, and organisational interaction. By defining what is appropriate and/or expected in various social and commercial situations, institutions guide behaviour (Bruton et al., Citation2010). Normative systems are typically comprised of values and norms that further establish consciously followed ground rules, which people must conform to. It is also often called culture. Normative systems define goals or objectives and also designate the appropriate ways to pursue them (Scott, Citation2007). Thus, normative institutions exert strong influence because of their social obligation to comply, rooted in social necessity or what organisations and individuals should be doing (March & Olsen, Citation1989). It has also been argued that some societies have norms that are geared toward the facilitation and financing of entrepreneurship, while some other societies do not encourage it by making it difficult, often unwittingly (Baumol et al., Citation2009).

The relevance of this pillar to the current study is that entrepreneurs in the developing world, in seeking to build their capacity for growth and development, must take into consideration the societal and/or cultural implications of their actions. The goals and objectives of these entrepreneurs must be cultural and societal driven (Scott, Citation2007). It is only by doing this that the norms of the society will be geared towards encouraging and facilitating entrepreneurship (Baumol et al., Citation2009). Wealth generation and employment provision, particularly in certain localities, are considered to be legitimate socio-economic functions of new enterprises and small businesses in developing countries. Therefore, normative considerations include the attitudes, norms, and cultural values towards entrepreneurship, which underpin the philosophy and approach behind setting up enterprise-support programmes by such institutions, such as government agencies, financial institutions, higher education institutions, and international institutions.

2.4.1. The cognitive pillar

The last pillar is the cognitive pillar. It is derived from the recent cognitive turn in social science (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1991). It represents models of individual behaviour based on subjective and constructed rules and meanings that place limits on appropriate beliefs and actions. The cognitive elements of institutions are the rules that constitute the nature of reality and the frames through which meaning is made. Cognitive structures affect the cognitive programs, i.e., schemata, frames, and inferential sets, which people use when selecting and interpreting information (Markus & Zajonc, Citation1985). Cognitive pillars often operate more at the individual level in terms of culture and language and other taken-for-grantedness and preconscious behaviour that people rarely think about (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1991; Scott, Citation2007). The importance of this pillar to entrepreneurship research is explained in terms of how societies accept entrepreneurs, inculcate values, and even create a cultural environment whereby entrepreneurship is accepted and encouraged (Harrison, Citation2008). This is very closely linked to normative pillars, but the emphasis is more on the knowledge base and learning of entrepreneurs and owner managers and making sense of such knowledge for synthesising it for effective enterprise development.

On the basis of the above discussion, the research questions guiding the current study are as follows: 1. What are the principal actors in the entrepreneurship development agenda in the developing world? 2. What is the strategic role of government in the entrepreneurship programme of developing countries? How do stakeholders on the entrepreneurial development agenda operate at intertwined layers of regulative, normative, and cognitive pillars of an ecosystem?

3. Research methods

The study aims at developing a framework for entrepreneurship ecosystem for developing countries with the application of institutional theory. Ghana is chosen as the study area. The two major cities of Accra and Kumasi were the focus areas of the study. These two cities were selected by reason of the fact that they are the two major cities of Ghana and majority of owner managers are located there. Besides, Accra and Kumasi represent the southern and northern sectors of Ghana, respectively, thus eliciting responses across the country.

The population consisted of owner managers of all registered small businesses in these two cities that fell within the definition of small businesses provided by the National Board for Small Scale Industries in Ghana (NBSSI). The selection was further based on whether the owner managers had had any dealings with any enterprise-support institution in Ghana. In addition, four major enterprise-support institutions were selected for the study. They include higher educational institutions, government agencies, international organisations, and financial institutions. These institutions were selected because of their pivotal role in entrepreneurship development. Thus, the sampling technique adopted in the study was purposive sampling (Patton, Citation2002). In all, 61 small business owners were selected for the study. In addition, 19 institutions were selected for the study. These were institutions that the researchers identified as having activities that were geared towards entrepreneurship capacity building and were willing to participate in the study. They included four higher educational institutions, five government agencies, four banking institutions, five microfinance companies, and one international organisation.

The study is mainly qualitative. The analysis process started with the transcription of the interviews. The transcription was done by listening to the audiotape and making reference to the notes, which were taken alongside to make sure that all relevant data were captured. The transcription was done in word document in a structured form according to the order of the questions on the interview guide. This was done for each interview guide. With this structured data, the researcher took advantage of NVivo’s auto-coding features and imported them into NVivo software. The software then automatically developed the codes for analysis.

After the transcription of the interviews and the importation into the NVivo software, the researcher identified those words and/or statements that featured prominently under each node for the purpose of analysis. With the help of the NVivo software, the researchers grouped the segments into categories that reflect the various aspects of the subject under investigation. There was thus the identification of common and relevant themes and meaning created out of them (Leedy & Ormrod, Citation2005; Malhotra, Citation2007; Zikmund et al., Citation2010).

The final result was, therefore, a general description of the subject under study as described by the respondents. The focus again was on common themes in the responses, even though there were divergent views on some issues raised during the interviews on both sides of the participant divide.

4. Results and discussion

This section seeks to discuss the results of the study, which have culminated in the development of a framework for entrepreneurship ecosystems in developing countries with the application of institutional theory. Thus, the three pillars of institutional theory feature prominently in the discussion of the components of the framework. The discussion of the components of the framework also takes into consideration the invaluable role the major enterprise institutions are playing as well as the general attitude of entrepreneurs or owner managers with regard to their relationship with these institutions.

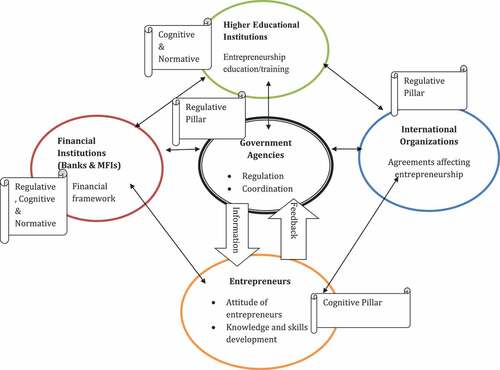

Figure shows a framework for the development of entrepreneurship in developing countries. It is made up of government agencies at the centre, regulating and coordinating the activities of the other enterprise-support institutions of higher educational institutions, financial institutions (banks and microfinance companies), international institutions, and entrepreneurs. The framework also shows the underpinning pillars of institutional theory. The components of the framework are discussed below.

Figure 1. Framework for entrepreneurship development in developing countries.

4.1. The government: regulating and coordinating functions: the regulative -man

In developing countries, such as Ghana, the government has a central role to play in regulating and coordinating the activities of other enterprise-support institutions and entrepreneurial firms (Michael & Pearce, Citation2009; Tambunan, Citation2008). Figure shows the central role of regulating and coordinating the activities of the enterprise-support institutions and entrepreneurs. This is done through the government agencies or one main agency responsible for regulating and coordinating the activities of enterprise-support organisations and the activities of entrepreneurs. Multiplicity of agencies performing almost the same functions of regulating and coordinating the activities of these institutions andsmall businesses is not helpful. This is because, as the study revealed, some functions overlap. For example, some activities and/or functions of the National Board for Small Scale Industries (NBSSI), Rural Enterprises Project (REP), and Micro Finance and Small Loans Centre (MASLOC) do overlap. Even though the various agencies of government seem to be focusing on different types of entrepreneurs, there is no clear-cut distinction of functions and focus. This can result in confusion among entrepreneurs.

The need to regulate the activities of the enterprise-support institutions and small businesses is to ensure that there is sanity in the system for entrepreneurship growth and development. Some enterprises support institutions that are profit oriented and will therefore support entrepreneurship development in a way that will help them achieve their parochial objectives. For example, the study revealed that the prevailing criteria for accessing support (training and financial) from the financial institutions are not favourable at all to small businesses and entrepreneurship development for that matter. Some of these institutions will not offer any support to small businesses or entrepreneurs that are not their customers. This point is buttressed by the response of one bank official in this way:

We invite our customers to hear their challenges and offer pieces of advice we believe will help them. The advice borders on current issues which we believe have the potential of increasing the productivity of the businesses of our clients.

Even for those that are their customers, the criteria for qualifying for support are so stringent that the majority of the entrepreneurs are alienated. In addition, these financial institutions do set their lending rates arbitrarily to the disadvantage of the entrepreneur so that it becomes almost impossible to borrow for investment. Besides, almost all the higher educational institutions are commercializing their support in the form of training to small businesses to the extent that some of them do charge entrepreneurs huge sums of money before they can access their training programmes. In addition, the charges are in dollars instead of Ghanaian cedis. A participant from one of the universities in Ghana stated that

We do charge for our services mainly because we need to maintain the secretariat. They pay in dollars or dollar equivalent. As to how much they pay now, I cannot tell.

This has a tendency to turn away a lot of entrepreneurs to the detriment of entrepreneurship growth and development and the economy for that matter. The government comes in to ensure that the activities of the enterprise-support institutions; particularly the financial institutions are properly regulated to ensure effective growth and development of entrepreneurship in the developing countries (Sacerdoti, Citation2005). For example, the lending rates to small businesses can be decided by the government, and the financial institutions are supposed to abide by them.

Coordinating functions are equally important since having regulations in place without effective coordination of the activities of the enterprise-support institutions and small businesses will not augur well for entrepreneurship development. Coordination in this context means ensuring that all the activities of the stakeholders for entrepreneurship development in the country (the government, financial institutions, international organisations, higher educational institutions, and entrepreneurs) are well organised. This can be achieved by the government having a credible database of the activities of enterprise-support institutions and other entrepreneurial opportunities (domestic and abroad) and making them available to the owner managers. These owner managers must have access to this information at no cost to them. In addition, entrepreneurs must provide the government agencies with feedback on their activities and the challenges they face on a regular basis. This will ensure that pragmatic measures are put in place to address the challenges faced by entrepreneurs holistically.

4.2. Entrepreneurship education and training: the role of higher educational institutions: interface of cognitive and normative pillars

Entrepreneurship growth and development in developing countries thrive on entrepreneurial education and training. In other words, there cannot be any meaningful economic development through entrepreneurship and small business development without entrepreneurial education and training (Cope, Citation2005). Entrepreneurs need to build capacity through the acquisition of knowledge. This is pivotal to the growth and development of their ventures as their knowledge will be brought to bear on the effective and efficient management of their ventures for higher performance. Thus, there is the recognition that there is a positive correlation between the level of knowledge and/or expertise of entrepreneurs and the level of development of their ventures (Sinha, Citation2004).

Many enterprises support institutions are in the business of providing education and training to entrepreneurs. This ascribes to the cognitive pillar. The cognitive pillar recognises the importance of knowledge and skills to the development of entrepreneurship (Dacin et al., Citation2007; Scott, Citation2007; Tolbert et al., Citation2011). Moreover, these institutions are raising awareness about entrepreneurship, which also connects to the normative pillar of institutional theory. One such enterprise-support organisations in Ghana and other developing countries is higher educational institutions, which have an even more important role to play in providing education and training, as well as creating awareness about entrepreneurship. The reason is that education and training are core functions of higher educational institutions unlike the others, such as the financial institutions and government agencies (Bolden et al., Citation2008). The coordinator of the entrepreneurship programme at one of the public universities in Ghana indicated that

The fact is that many of these entrepreneurs and small businesses owners are ignorant of good business practices and therefore there is the need for the creation of awareness. For example, some of them combine their personal and business accounts and others do not keep proper records. Basically, we are there to help them to grow their businesses

The findings of the study further suggest that there are two pathways by which higher educational institutions can contribute meaningfully to the growth and development of entrepreneurship in developing countries. The first is entrepreneurship community service. Universities and polytechnics are providing services to the community in general as part of the roles they play in society. Entrepreneurship education and training thus become an integral part of their community service. This can even be used in rating these institutions and also serve as important input for promoting staff of the universities and polytechnics. In an attempt to get better ratings, the institutions will ensure that they do not relent in contributing to the success of small businesses in their countries. Members of staff are also going to lend their support because they know that will be integral to their promotion and/or professional advancement.

Again, the findings suggest that the current level of support for entrepreneurs in the developing world by higher educational institutions is not to the level that can revamp the activities of small businesses or build their capacities for growth and development. Thus, the entrepreneurship community service pathway is very important in ensuring the continuous improvement and/or sustainability of the current support programmes, which the higher educational institutions are providing for entrepreneurs. It also has the positive effect of reducing the current commercialisation of education and training support for entrepreneurs by the higher educational institutions in Ghana and other developing countries.

The other pathway is graduate entrepreneurship. The aforementioned pathway is for existing entrepreneurs or owner managers. The graduate entrepreneurship pathway focuses on students in the polytechnics and universities in developing countries. Entrepreneurship education has become very popular in all countries and even in developed countries. This is as a result of the current recognition of the importance of entrepreneurship education to economic growth and development (Mafela, Citation2009). Thus, entrepreneurship education and training should be an integral part of the curricula of all departments and schools in the universities and polytechnics, spearheaded by business and management schools. In other words, before any student leaves a particular university or polytechnic, that student must have had education and training in entrepreneurship.

This will ensure that students do not come out of schools only to seek employment, which has characterised many a developing country but to seek self-employment. This is one of the surest ways to sustainable economic development through entrepreneurship growth and development. Inculcating entrepreneurship spirit in students and making them understand the importance of having their own business are of prime importance. This has the potential of raising entrepreneurship awareness among graduates and reducing unemployment, which has become the bane of developing countries to the extent that currently we have Unemployed Graduates’ Association in Ghana (Graphic Business, 2009).

4.3. Streamlining financial accessibility for entrepreneurs: the role of the financial institutions: interface of regulative, cognitive pillars, and normative pillars

Financial institutions have been playing a pivotal role in the growth and development of entrepreneurship in developed as well as the developing world (Klapper et al., Citation2002). In the context of this study, references are being made to banks and microfinance companies in Ghana and developing countries for that matter. As the study revealed, a lot of small businesses in Ghana face problems relating to finance. This has stagnated the growth of many a small business in the developing world (Abor & Biekpe, Citation2007; Kayanula & Quartey, Citation2000). Some owner managers had these to say:

“The banks ask for collateral which sometimes is not easy to come by. Also the high interest rate charged by the banks makes it unattractive.” “There is high interest rate and the banks demand collateral. It also takes a long time before accessing loans or before your application is processed.” “The challenges we have in getting funds from the banks are that they charge too high interest rate, and they demand collateral which discourages me to go forward to apply for loans.”

Thus, one main area entrepreneurs need to build capacity is that of finance. This will help the small businesses in employing modern methods of doing business so that small businesses can be competitive. This will also open up opportunities for potential entrepreneurs. This is connected to the regulative pillar of institutional theory, which among other things argues that the setting up of an effective financial framework and the encouragement of business setup are vital for entrepreneurship and economic development (Greenwood & Suddaby, Citation2006; North, Citation1990; Scott, Citation2007; Tolbert et al., Citation2011).

In streamlining financial accessibility for small businesses in the developing world, the financial institutions need to have bespoken financial facilities for small businesses, which should be different from large businesses. If small businesses and large businesses are borrowing at the same rate, it will be difficult for small businesses to stay competitive. This is explained by the fact that their level of development does not allow them to enjoy economies of scale. Thus, their cost of production is high which more often than not results in high prices for consumers. This has the effect of compounding their current financial challenges and thus hinders their growth and development (Ebben & Johnson, Citation2006; Winborg & Landstrom, Citation2000).

This study, however, reveals that small businesses and large ones in Ghana and other developing countries are treated the same way by financial institutions. As stated earlier, the small businesses and large ones are currently borrowing at the same rate. In addition, the majority of these financial institutions, particularly the banks, prefer doing business with the large businesses to that of the small businesses. This is because they are considered more effective when it comes to repayment of loans and are thus more profitable than small businesses. This attitude of financial institutions has the negative effect of still restricting access of entrepreneurs to credit. This does not augur well for entrepreneurship development in Ghana and the developing world. Entrepreneurship growth and development thrive on building the financial capacities of entrepreneurs and owner managers.

Recently, however, a study has revealed that almost all the banks have now begun finding ways of providing bespoke financial services to small businesses. Banks and other financial institutions, as the study revealed, have come to the recognition that the small business sector has much to offer them in terms of business and that the earlier they gave them the attention the better. In other words, the banks have recognised that the large businesses of today were once small businesses. Moreover, the aggregation of the businesses of entrepreneurs to the banks can compare favourably with that of the large businesses. For example, a participant from one of the financial institutions said that

“There is the springing up of SMEs in Ghana and there is the need to penetrate the market for mutual benefits. These SMEs grow into large corporations; help them grow and all will benefit. The SMEs sector is the engine of growth”.

The efforts of financial institutions can be supported by other enterprise-support institutions, particularly the government agencies. The government, through its agencies, can come up with financial policies that will allow financial institutions to effectively support small businesses. The explanation is that the study has revealed that the banks in Ghana do charge high interest rates because their rate is based on the prime rate of the Bank of Ghana. Thus, the banks are not prepared to reduce their lending rates. In streamlining financial accessibility for entrepreneurs in Ghana and other developing countries, a special fund can be set up by the government (through the central bank), and the small businesses can access it through the banks with low interest rates.

The cognitive pillar of institutional theory recognises that the attitude, beliefs, and actions of entrepreneurs determine their legitimacy (Bosma et al., Citation2009; Harrison, Citation2008). In order to streamline financial accessibility for entrepreneurs, they need to have an honest attitude to the financial institutions by honouring their financial obligations. This is because the study has indicated that some entrepreneurs do not honour their financial obligations, leading to financial institutions becoming sceptical about lending to small businesses. This was revealed by the responses of some bank officials:

“Default is high and this affects future lending to SMEs.” “We also have problem with default on the part of entrepreneurs and small businesses particularly the group loan customers.” “Some virtually run away with the money.” “Our main challenge is default on the part of entrepreneurs.”

The solution to the problem may be the readiness of the government to serve as guarantor for the entrepreneurs. This may also have its own challenges, such as entrepreneurs taking advantage of the system knowing very well that in default the government will be held responsible. Thus, there is the need for effective collaborations for the development of a workable and effective financial framework for entrepreneurship development in Ghana and the rest of the developing world.

It is important to mention at this point that entrepreneurship development does not hinge on financial accessibility alone. In other words, the creation of financial accessibility for entrepreneurs does not necessarily result in entrepreneurship development. It has to be complemented by good management practice on the part of the entrepreneurs. Good management practice is embedded in the acquisition of knowledge and skills (Rae, Citation2000). Thus, entrepreneurs need to acquire and/or enhance their managerial skills to be able to put their finances to good use for higher productivity. One of the most cited reasons for the failure of small businesses in Ghana and other developing countries is mismanagement; particularly financial mismanagement (Lighthelm & Cant, Citation2002).

To this end, financial institutions in Ghana, in addition to streamlining financial accessibility, have put measures in place to provide business support programmes for entrepreneurs as a way of helping them to effectively manage their ventures. The responses of some bank officials as stated below support the argument:

We provide training programmes for entrepreneurs. These programmes are organised in conjunction with Empretec Foundation (a non-governmental organisation in Ghana) for some selected entrepreneurs. The actual organisation of the programme is done by Empretec and we finance it.

Depending on the needs of members of our entrepreneurship club and availability of resource persons; the club meets once a month. During such meetings members are taken through courses such as basic book keeping, management skills, business plan preparation, etc.

These business support programs are geared toward helping entrepreneurs acquire more knowledge and skills in modern management practices. This is important not only for the entrepreneurs but also for the financial institutions. The effective management of their ventures will ensure higher productivity and profitability, which are necessary for entrepreneurs to honour their financial obligations to the financial institutions. The national economy also stands to benefit more as these entrepreneurs expand their businesses to employ more people and pay more taxes for the development of the economy. This is linked to the normative pillar of institutional theory, which indicates among other things that the level and nature of the knowledge and skills of entrepreneurs are vitally important for entrepreneurship development. It also emphasises the streamlining of the contents and formats of business support programmes for entrepreneurship development (Greenwood & Suddaby, Citation2006; Scott, Citation2007; Tolbert et al., Citation2011).

4.3.1. international agreements affecting entrepreneurs and SMEs: Regulative pillar

International institutions have been contributing effectively to entrepreneurship and small business development in developing countries. This is as result of the recognition of the international community that entrepreneurship is the bedrock for economic development in countries of the developing world. The activities of international institutions in the developing world have complemented the activities of indigenous enterprise-support institutions and the government in particular. This is essential in promoting entrepreneurship in the developing world in order to alleviate poverty. The International Finance Corporation (IFC) reports that globally, income distribution is highly skewed. Plotted on a graph, it looks more like a pyramid with a base made of two-thirds of the world’s population who are poor and live on less than $8 dollars a day. These people, the majority of whom are in the developing world, have limited economic power and limited economic opportunities.

It has been argued that governments of developing countries alone cannot effectively support the development of entrepreneurship in their countries. Even though the governments of the developing world are doing what they can to support entrepreneurship, international support is inevitable. This is as a result of the fact these governments have limited resources that must be equitably distributed to the various sectors of the economy. Thus, the governments are left with very little to support entrepreneurs fully (Michael & Pearce, Citation2009; Tambunan, Citation2008). For example, the current study found that the government of Ghana has not been able to adequately resource its agencies such as the National Board for Small Scale Industries (NBSSI). An official of NBSSI clearly indicated that their budgetary allocation from the government has been limited to 70% with the explanation that the government does not have enough. This is in agreement with the regulative pillar of institutional theory, which emphasizes that governments enter into agreements with international organisations for entrepreneurship development (Dacin et al., Citation2007; David & Bitektine, Citation2009; Scott, Citation2007).

Part of the current study focused more on agreement and/or collaboration between the government of Ghana and the UNDP. The study revealed that the government of Ghana and the UNDP have partnered for the development of the economy through entrepreneurship growth and development. Under the agreement, the UNDP through its MSMEs project in Ghana provides a range of programmes and facilities for the micro and small business sectors. The project provides business development services support. This has to do with the provision of training for entrepreneurs in areas, such as entrepreneurship development, marketing, book keeping, change management, among others. This project has positively impacted the activities of some small business owners in Ghana. These small business owners have incorporated the knowledge received into the running of their ventures and are currently performing better than before. This high performance ultimately translates into financial capacity, so that the overdependence of small businesses on financial institutions is reduced (Ebben & Johnson, Citation2006; Winborg & Landstrom, Citation2000). It must be stated, however, that not many of the small businesses have benefited from these collaborations between the government and the UNDP. This is as a result of the poor attitude of some owner managers. Some of them have the attitude of receiving the training but not putting them into practice. Moreover, the UNDP is not able to cover more of these entrepreneurs because of resource constraints. This then suggests that entrepreneurship development in Ghana and other developing countries needs the support of more organisations and institutions. An official at the office of the UNDP in Ghana in describing some of their challenges in dealing with owner managers had this to say:

The amount of money that comes is not enough considering the number of entrepreneur who needs financial assistance. Moreover, literacy level of the entrepreneurs was appalling hence the training was sometimes organized in Twi. There is also the evidence that they do not apply the knowledge received at training from us.

Entrepreneurs in Ghana are still faced with the problem of financial accessibility, which has affected a lot of the small businesses and even led to the demise of many small businesses (Sunter, Citation2000). Facilitating accessibility to finance is thus a pre-requisite for entrepreneurship development in developing countries. To this end, the UNDP project again helps in building the capacities of microfinance institutions (MFIs) so as to enhance access to financial services or facilities by medium, small, and micro enterprises (MSMEs). The UNDP undertakes this project by training MFIs in the best practices for microfinance delivery. Furthermore, the project provides matching funds (grants) to the MFIs specifically for lending to the MSMEs. Again, the MFIs are provided with information and telecommunication technology facilities to enhance efficient tracking of loan portfolio to ensure good portfolio quality and sustainability. The challenge with this facilitation function is what the researchers refer to as “selective support” on the part of the MFIs. Some of these MFIs expect small businesses to have done business with them for a specified period of time before accessing credit from them. Thus, not all entrepreneurs who are into direct business relationships with these MFIs are denied access. This does not help in building entrepreneurship capacity comprehensively. A participant from one MFI stated that:

“How much we give to the group members depend to a large extent on how the group has operated its account with us for at least three months. Also the enterprises of the group members will be evaluated by our officials. After the three months, the total savings of the group is multiplied by two and given as a loan facility to the members of the group. All the group members are held responsible for the repayment of the loan.

Apart from the UNDP, as the study revealed, other international organizations have partnered with the government of Ghana for the building of entrepreneurship capacity for growth and development. Some international organisations are the Japan International Co-operation Agency (JICA), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and United Nations Industrial Development Organisation (UNIDO). These international organisations embark on a lot of activities that are geared towards the building of entrepreneurship capacity in Ghana. One of such programmes was organised by the UNDP under the theme “Capacity building for medium, small and micro-enterprises.” The overarching objective of the project was to increase the productivity of small businesses to enhance their opportunity for growth and expansion and their capacity for absorbing more labour leading to poverty alleviation. Such programmes have been successful because of the effective collaboration between the international institutions and the government of Ghana.

The international organisation again provides financial assistance to entrepreneurs or small business owners since their access to credit is limited (Le et al., Citation2006). To this end, JICA and the UNDP set up a project with a seed money of US$245,927.00 to assist entrepreneurs, particularly women in the Northern Region of Ghana; which is considered one of the poorest. In addition, the organisations provide training programmes in many areas to both current and potential entrepreneurs. JICA, for example, sponsored eight young Ghanaians for a training programme in Japan on the promotion of small and medium enterprises. The aim of the programme was to provide the young entrepreneurs with the opportunity to develop their specialities through experience and learning technologies and skills in Japan.

The activities of international organisations have complemented the role of the government and other indigenous enterprise-support institutions. Their role in entrepreneurship capacity building has improved the management skills and financial capacity of entrepreneurs. Without these entrepreneurship building capacity activities of international organisations, many small business owners may have gone out of business. Their training programmes for entrepreneurs, which are most of the time free of charge, have been of immense help to small businesses. the activities of the entrepreneurs have contributed to employment generation thereby solving one of the greatest problems of Ghana-unemployment (Kayanula & Quartey, Citation2000).

It must, however, be stated that, for these collaborations and agreements between the international organisations and the government of Ghana and other developing countries to contribute significantly to entrepreneurship development and for it to be sustainable, there is the need for some stringent measures to be put in place. First, successive government of the developing world should commit themselves to existing agreements between international organisations and the government. This is important in the sense that in some developing countries, such as Ghana, successive governments do not want to continue the “good works” of the preceding government (Graphic business 2009). This is because such programmes go to the credit of the government that started them which can help them gain political advantage. This attitude can affect international agreements to the detriment of entrepreneurs.

Moreover, international institutions must commit themselves to the agreements and/or memorandum of understanding they sign with government agencies. The study found out that some international organisations after signing a memorandum of understanding with government agencies, renege on their duties. For example, the amount of money promised to these institutions is not provided. Even those that are provided do not come as scheduled. This has a tendency to put the programmes and activities of government agencies aimed at supporting small businesses in disarray.

The specificity of support on the part of some international institutions does not augur well for comprehensive entrepreneurship capacity building. The study further revealed that some international institutions specify areas in the small business sector that they are prepared to support. The UNDP, for example, has stringent requirements with regard to which entrepreneurs can attend their programmes and access their financial facilities from the MFIs.

As another example, JICA and UNDP set up a project with seed money of US$245,927.00 to assist entrepreneurs, particularly women in the Northern Region of Ghana (Ghana News Agency, 2013). This is very significant for entrepreneurship development in Ghana. The question, however, is, what about their male counterpart? Entrepreneurship development programmes must be broad-based in order to have a stronger impact on entrepreneurship capacity building.

4.4. The growth and development of entrepreneurship: the attitude of entrepreneurs: the cognitive pillar

One of the important stakeholders in the building of capacity for entrepreneurship growth and development in developing countries is entrepreneurs themselves. In other words, the growth and development of entrepreneurship in developing countries depends to a very large extent on the entrepreneurs themselves. The cognitive pillar emphasises entrepreneurs’ attitude, beliefs, and actions, as well as acquisition of knowledge and skills, which are vitally important for entrepreneurship development. The cognitive pillar again recognises that subjective rules and meanings in the entrepreneurial environment define appropriate behaviour or actions of entrepreneurs (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983; Scott, Citation2007). The importance of the appropriate actions of entrepreneurs to entrepreneurship development is underscored by the fact that the activities of entrepreneurs contribute significantly to economic development (Minniti & Naude, Citation2010; Peng, Citation2001; Tamvada, Citation2010).

Research has suggested that there are several ways through which entrepreneurs contribute to economic development. Thus, policymakers have increasingly become interested in matters that border on entrepreneurship and have recognised the importance of small businesses to economic development. Entrepreneurs contribute to economic development through the creation of employment (Hochberg, Citation2002; Mohanty, Citation2009). In addition, they play a critical role in maintaining and developing the economic order (Wong et al., Citation2005). In Ghana, for example, the small business sector has been recognised as the engine of growth of the national economy (Graphic Business, 2009).

Thus, the actions and for that matter inactions of entrepreneurs can go a long way to affect entrepreneurship development and for that matter economic development in developing countries. If they relent in their roles as key stakeholders, entrepreneurship development in developing countries will suffer. Apart from the government, international organisations and other enterprise-support institutions, the entrepreneurs need to play their roles very well at the individual level (Meyer & Rowan, Citation1991; Scott, Citation2007) in order to ensure effective growth and development of the national economies of developing countries.

The study has revealed that for entrepreneurs to play their roles well and make any meaningful impact on the economy of developing countries, one of the areas they need to build capacity is that of education and training. This is consistent with the cognitive pillar of institutional theory, which subscribes to the acquisition of knowledge and skills by entrepreneurs as pre-requisite for growth and development of their ventures and the economy (Meyer & Rowan, Citation1991; Scott, Citation2007)

The enterprise-support organisations and the government of Ghana through its agencies are putting the necessary measures in place in order to help entrepreneurs to acquire knowledge and skill in the management of their ventures. This is as a result of the recognition of the government and other enterprise-support institutions of the small business sector as the hub of the economy of Ghana (Business & Financial Times, 2013). The enterprise-support institutions provide training to owner managers in the area of business managements such as proper book keeping, good employee relations, customer service, computer skills, effective pricing, among others. In addition, entrepreneurs are provided with business-related advice and/or information by the enterprise-support organisations, which are relevant for the building of entrepreneurship capacity both in the short and long terms. The following comments from some enterprise support

enterprise-support institutions corroborate this assertion:

We run short courses for entrepreneurs and small business owners and provide opportunities for them to meet at regular intervals to discuss issues affecting them. We invite resource persons at seminars on a wide range of topics such as total quality management, professionalism, customer care, modern techniques and others.

We provide Business Development Services Support (BDSS). By this BDSS we give them training in entrepreneurship development, marketing change management, etc. We also help in building MFIs institutions to enhance access to financial services by MSMES. To this end we give them training is best practices in micro finance delivery. We provide IT facility to enhance efficient tracking of loan portfolio to ensure good portfolio quality and sustainability. We again provide matching funds (grants) for on- lending to MSMES.

It has been acknowledged that entrepreneurship growth and development thrives on education and training. Entrepreneurship learning and experience are very important in building entrepreneurship capacity for growth and development (Cope, Citation2005; Rae, Citation2000); particularly in the developing world where policymakers are leaving no stone unturned to ensure sustainable development. Thus, entrepreneurship development in Ghana and other developing countries’ demands that entrepreneurs’ attitude to education and training is positive.

The study revealed that some entrepreneurs have availed themselves for education and training provided by the enterprise-support institutions. This has helped in building their capacity for effective management of their businesses. For example, some of them have now realised the need to separate personal finance from the finances of the business. Moreover, others have begun keeping proper books of accounts and employing some other management tools as a way of revamping their businesses. This is important; however, there is the need for these activities of the entrepreneurs to be sustained through continuous push for education and training, which demands a positive attitude from the entrepreneurs (Cope, Citation2005; Sinha, Citation2004). This is explained by the fact that the business world is volatile. New information and new ways of doing business are always evolving. For entrepreneurs to make significant contributions to the economy of developing countries, they must stay current in the business world by committing themselves to continuous acquisition of knowledge and skills and this is consistent with the cognitive pillar of institutional theory (Scott, Citation2007).

The activities of these entrepreneurs will be given legitimacy if their attitude to the acquisition of knowledge and skill is positive and are thus able to translate them into effective and efficient running of their ventures for the benefit of society (Bosma et al., Citation2009; Harrison, Citation2008). Policy makers and other enterprise-support institutions and the general society in Ghana and other developing countries will support the activities of small business if owner managers apply modern methods of doing business and come out with competitive products. For example, the situation where some small businesses find it difficult to sell their products will be a thing of the past. There is bound to be a paradigm shift from preference for foreign products and products of large businesses to that of small businesses.

Thus, the time has come for entrepreneurs in developing countries to think outside the box and avail themselves for knowledge acquisition and skills development. These are necessary ingredients for building entrepreneurship capacity for growth and development. There should also be an inordinate desire on the part of entrepreneurs for information. There should be the exploitation of all avenues with the view to obtaining accurate and timely information relevant for the growth and development of their ventures. Information is relevant for effective business decision-making and for the identification of the relevant entrepreneurial opportunities (Rae & Carswell, Citation2000).

There is a need for comprehensive entrepreneurial attitudinal change in Ghana and other developing countries. The study further revealed that whereas some entrepreneurs have done their best in accessing training and education programmes by enterprise-support institutions, some have woefully ignored them. Even those who acquire the needed knowledge; there is evidence to suggest that some of them do not apply the best practices that they have learnt and stick to the status-quo. This attitude on the part of the entrepreneurs does not augur well for entrepreneurship and economic development.

5. Conclusion

The importance of entrepreneurship development to the national economies of the developing world cannot be overemphasised. Entrepreneurs or owner managers have contributed immensely to the socio-economic well-being of developing countries and Ghana, for that matter, as the entrepreneurship ecosystem in Ghana bears some semblance to those of other developing countries. Thus, there is the need for the building of the capacities of owner managers as a way of encouraging them to continuously push for innovative ideas that can be translated into acceptable products. Most of the time, governments of the developing world have invariably been charged with the sole responsibility of building entrepreneurship capacity. The realisation from the current study, however, is that, the capacity-building responsibility does not rest on only one institution. Five major institutions have been identified as being collectively responsible for entrepreneurship capacity building. These are government agencies, financial institutions, higher educational institutions, international institutions, and entrepreneurs or owner managers. All these stakeholders have their respective roles to play in ensuring the growth and development of entrepreneurship in developing countries. Though entrepreneurship development does not depend on the government alone, the fact still remains that, for effective results, governments of the developing world need to play a leading role in coordinating and regulating the activities of the other stakeholders or institutions that operate at intertwined layers of regulative, normative, and cognitive pillars of an ecosystem.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Bylon Abeeku Bamfo

Bylon Abeeku Bamfo is an Associate Professor of Marketing and Entrepreneurship in the Department of Marketing and Corporate strategy of KNUST School of Business, Kumasi, Ghana. His research areas include advertising, consumer behaviour, social marketing, entrepreneurship, and small business management, among others.

References

- Abor, J., & Biekpe, N. (2007). Small business reliance on bank financing in Ghana. Emerging Market Finance and Trade, 43(4), 93–19. https://doi.org/10.2753/REE1540-496X430405

- Acquaah, M. (2005). Enterprise ownership, market competition and manufacturing priorities in a Sub-Saharan African emerging economy: Evidence from Ghana. Journal of Management & Governance, 9(3–4), 205–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-005-7418-y

- Baumol, W. J., Litan, R. E., & Schramm, C. J. (2009). Good capitalism, bad capitalism and the economics of growth and prosperity. Yale University Press.

- Bolden, R., Petrov, G., & Gosling, J. (2008). Tensions in higher education leadership: Towards a multi-level model of leadership practice. Higher Education Quarterly, 62(4), 358–376. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.2008.00398.x

- Bonckeck, M. A., & Shepsle, K. A. (1996). Analysing politics: Rationality, behaviour and institutions. W.W. North & Co.

- Bosma, N., Acs, Z. J., Autio, E., Coduras, A., & Levie, J. (2009), Global entrepreneurship monitor: 2008 executive report, Global Entrepreneurship Research Consortium.

- Brandl, J., & Bullinger, B. (2009). Reflections on the societal conditions for the pervasiveness of entrepreneurial behaviour in Western societies. Journal of Management Inquiry, 18(2), 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492608329400

- Bruton, G. D., Ahlstrom, D., & Li, L. Institutional theory and entrepreneurship: Where are we now and where do we need to move in future?. (2010). Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 34(3), 421–440. Special Issue. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00390.x

- Cao, Z., & Shi, X. (2021). A systematic literature review of entrepreneurial ecosystems in advanced and emerging economies. Small Business Economics, 57(1), 75–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00326-y

- Cope, J. (2005). Towards a dynamic learning perspective of entereprenerhsip. Entrepreneurhsip Theory and Practice, 29(4), 373–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00090.x

- Dacin, M. T., Oliver, C., & Roy, J. (2007). The legitimacy of strategic alliances: An institutional perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 28(2), 169–187. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.577

- David, R. J., & Bitektine, A. B. (2009). The institutionalization of institutional theory? Exploring divergent agendas in institutional research. In D. Buchanan & A. Bryman (Eds.), The sage handbook of organizational research methods (pp. 160–175). Sage.

- Delmar, F., & Shane, S. (2004). Legitimating first: Organizing activities and the survival of new ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(3), 385–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00037-5

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1991). The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. University of Chicago Press.

- Ebben, J., & Johnson, A. (2006). Bootstrapping in small firms: An empirical analysis of change over time. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(6), 851–865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.06.007

- Greenwood, R., & Suddaby, R. (2006). Institutional entrepreneurship in mature fields: The big five accounting firms. Academy of Management Journal, 49(1), 27.48. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.20785498

- Harrison, L. E. (2008). The central liberal truth: How politics can change a culture and save it from itself. Oxford University Press.

- Hinnings, C. R., & Tolbert, P. S. (2008). Organisational institutionalism and sociology: A reflection. The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism.

- Hochberg, F. P. (2002), American capitalism’s other side,

- Hoffman, A. J. (1999). Institutional evolution and change: Environmentalism and the U.S. chemical industry. Academy of Management Journal, 42(4), 351–371. https://doi.org/10.2307/257008

- Japperson, R. (1991). Institutions, institutional effects and institutionalism. In W. W. Powell & P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organisational analysis (pp. 143–163). University of Chicago Press.

- Kayanula, D., & Quartey, P. (2000), The policy environment for promoting small and medium-sized enterprises in Ghana and Malawi, IDPM finance and development research programme working paper series 15.

- Klapper, L. F., Sarria-Allende, V., & Sulla, V. (2002), Small-and medium-size enterprise financing in Eastern Europe, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 2933.

- Leedy, P. D., & Ormrod, J. E. (2005). Practical research: Planning and design (8thed. ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Le, T. B. N., Venkatesh, S., & Nguyen, V. T. (2006). Getting bank financing: Study of Vietnamese private firms. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 23(2), 209–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-006-7167-8

- Lighthelm, A. A., & Cant, M. C. (2002). Business success factors of SMEs in Gauteng. University of South Africa.

- Mafela, L. (2009). Entrepreneruship education and community outreach at the University of Botswana. Eastern Africa Social Science Research Review, 25(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1353/eas.0.0011

- Malhotra, N. K. (2007). Marketing research: An applied orientation (5th ed ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Manolova, T. S., Eunni, R. V., & Gyoshev, B. S. (2008). Institutional environments for entrepreneurship: Evidence from emerging economies in Eastern Europe. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 32(1), 203–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2007.00222.x

- March, J. G., & Olsen, J. P. (1989). Rediscovering institutions: The organizational basis of politics. Free Press.

- Markus, H., & Zajonc, R. (1985). The cognitive perspective in social psychology. In E. Lindzey. & E. Aronson (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (3rd ed., pp. 137–230). Random House.

- Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1991). Institutionalized organisations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. In W. W. Powell & P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organisational analysis (pp. 41–62). University of Chicago Press.

- Michael, S. C., & Pearce, J. A. (2009). The need for innovation as a rationale for government in entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 21(3), 285–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620802279999

- Minniti, M., & Naude, W. A. (2010). What do we know about the patterns and determinants of female entrepreneurship across countries? European Journal of Development Research, 22(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2010.17

- Mohanty, S. K. (2009). Fundamentals of entrepreneurship. PHI Learning.

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions: Institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press.

- North, D. C. (1991). Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.5.1.97

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Sage Publication.

- Peng, M. (2001). How entrepreneurs create wealth in transition economies. Academy of Management Executive, 15(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2001.4251397

- Rae, D. (2000). Understanding entrepreneurial learning: A question of how?. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 6(3), 145–159. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552550010346497

- Rae, D., & Carswell, M. (2000). Using a life-story approach in researching entrepreneurial learning: The development of a conceptual model and its implications in the design of learning experiences. Education and Training, 42(4/5), 220–227. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910010373660

- Sacerdoti, E. (2005), Access to bank credit in Sub-Saharan Africa: Key issues and reform strategies, monetary and financial systems department, IMF Working Paper.

- Scott, W. R. (1994), Institutions and organizations: Towards a theoretical synthesis, IN, W. R. Scott. & J. W. Meyer (Eds.), Institutional environments and organisations: Essays and studies, pp. 55–80, Sage.

- Scott, W. R. (2002). Institutions and organisations. Sage Publications.

- Scott, W. R. (2007). Institutions and organisations: Ideas and interest. Sage Publications.

- Sinha, P. (2004). Impact of training on first generation entrepreneurs in Tripura. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 39(40), 4.

- Stokes, D. (1995). Small business management. Letts.

- Sunter, C. (2000). The entrepreneurs fieldbook. Prentice Hall.

- Tambunan, T. SME development, economic growth, and government intervention in a developing country: The Indonesian story. (2008). Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 6(4), 147–167. Online. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-008-0025-7

- Tamvada, P. (2010). Entrepreneurship and welfare. Small Business Economics, 34(1), 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9195-5

- Tolbert, P., David, R., & Sine, W. (2011). Studying choice and change: The intersection of institutional theory and entrepreneurship research. Organization Science, 22(5), 1332–1344. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0601

- Welter, F. (2011). Contextualizing Entrepreneurship-conceptual challenges and ways forward. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 35(1), 165–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00427.x

- Winborg, J., & Landstrom, H. (2000). Financial bootstrapping in small businesses: Examining small business managers’ resource acquisition behaviours. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(3), 235–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(99)00055-5

- Wong, P. K., Ho, Y. P., & Autio, E. (2005). Entrepreneurship, innovation and economic growth: Evidence from GEM data. Small Business Economics, 24, 335–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-005-2000-1

- Zikmund, W. G., Babin, B. J., Carr, C. C., & Griffin, M. (2010). Business research methods (8th ed. ed.). South-Western, Cengage Learning.