Abstract

The Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) pandemic has caused problems for Indonesian SMEs, in terms of supply chain and changes in their markets’ demand. SMEs cannot survive only by exploiting their existing businesses, but also by trying to explore new opportunities and ways of doing business. SMEs will have better performance if they can balance exploration and exploitation, hereinafter referred to as ambidexterity. Demand for ambidexterity is difficult because SMEs usually have limited resources and capabilities. Based on the literature review, the resource-based view (RBV) is the most frequently used perspective to discuss ambidexterity. This shows that the SMEs only focus on their internal resources so they experience a lack of resources. Based on this gap, the resource dependence theory (RDT) and social network theory are integrated with the RBV to broaden the discussion of ambidexterity in SMEs, to solve their resource-related problems.

Public interest statement

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused SMEs in Indonesia to face problems in terms of supply chains and changes in public demand. In order to be able to deal with these changes, SMEs are required to be able to carry out ambidexterity. Because most SMEs in Indonesia are family companies, ambidexterity will face obstacles related to limited internal resources. This study conducted a literature review to broaden the understanding of strategies for implementing ambidexterity. The results of the analysis show that research on ambidexterity so far has focused more on the RBV perspective. This has resulted in SMEs only relying on limited internal resources, thus experiencing resource problems. To overcome these problems, the discussion of ambidexterity in SMEs requires the perspective of RDT and Social network theory to complement the perspective of RBV. When SMEs establish relationships with external partners and create networks, SMEs will get additional resources to perform ambidexterity.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 Pandemic has caused several problems for SMEs, namely pressure regarding their cash flow, problems in the supply chain, and problems with changes in their markets’ demand (Lu et al., Citation2020; Xie et al., Citation2022). The first problem caused by the COVID-19 pandemic is their cash flow (Lu et al., Citation2020; Papadopoulos et al., Citation2020). This happens because not all SMEs have sufficient supplies or savings to deal with unexpected conditions. During the pandemic, SMEs have difficulty paying their employees’ salaries, debt interest, rent, and other costs. The second problem is related to the supply chain (Farzaneh et al., Citation2022; Lu et al., Citation2020; Papadopoulos et al., Citation2020; Xie & Wang, Citation2021). The distribution of goods and factory production, which has been hampered due to the COVID-19 pandemic, has caused SMEs to experience shortages in the supply of materials. The third problem is changes in the markets’ demand due to social restrictions to prevent the transmission of the COVID-19 virus (Lu et al., Citation2020; Papadopoulos et al., Citation2020; Sitinjak et al., Citation2022).

Current conditions require SMEs to not only survive by exploiting their existing businesses but also by trying to explore new opportunities (Atuahene-Gima et al., Citation2005; Indarti & Postma, Citation2013; Jaidi et al., Citation2022; Kuckertz et al., Citation2020; Papadopoulos et al., Citation2020; Posen & Levinthal, Citation2012). The company will have the ability to find new ideas for innovation, while maintaining existing products, if it has a high ability to balance exploration and exploitation (Gibson & Birkinshaw, Citation2004; March, Citation1991; Rothaermel & Deeds, Citation2004; Seo et al., Citation2022; Wilden et al., Citation2018; Xie et al., Citation2022). Exploitation without exploration causes the company to fail in responding to changing demands and in recognizing the product and the process of improvements that are needed. Conversely, companies that focus too much on exploration will face high costs, the risk of failure, and reduced profits from exploiting the existing products (Kuckertz et al., Citation2020; March, Citation1991). Companies will have better performance if they can balance exploration and exploitation, which is called ambidexterity (García-Hurtado et al., Citation2022; Kahn & Candi, Citation2021; Lavie et al., Citation2011; Rintala et al., Citation2022; Wenke et al., Citation2021; Wilden et al., Citation2018).

Resource issues are a big problem faced by SMEs when trying to implement ambidexterity. Apart from resource problems, implementing ambidexterity for SMEs also faces several other obstacles, namely having limited technical expertise, focusing only on incremental changes or exploitation, problems with the cost of inputs and manufacturing that expensive, bureaucracy and regulations, and developing new markets (Jacob et al., Citation2022; Sahi et al., Citation2020; Senaratne & Wang, Citation2018). Because the application of ambidexterity requires many resources, so far ambidextrous activities are usually carried out by large companies (Bengtsson & Johansson, Citation2014; Carney, Citation2005; Chang & Hughes, Citation2012; Gnyawali et al., Citation2016; Hughes, Citation2018; Lavie & Rosenkopf, Citation2006; March, Citation1991; O’reilly & Tushman, Citation2013). Only a few studies discuss the ambidexterity of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (Gibson & Birkinshaw, Citation2004; Ikhsan et al., Citation2017; Lubatkin et al., Citation2006). This happens because SMEs are usually family-owned companies with limited resources so that it is difficult for them to carry out ambidextrous actions when relying solely on internal resources (Bengtsson & Johansson, Citation2014; Carney, Citation2005; Hughes et al., Citation2017; Hughes, Citation2018; Voss & Voss, Citation2013; Widjaja & Sugiarto, Citation2022).

In Indonesia, the role of SMEs is crucial for Indonesia’s economic growth. The number of SMEs reaches 99% of all business units (Brodjonegoro, Citation2020). The contribution of SMEs to GDP also reaches 60.5%, and to employment is 96.9% of the total national employment absorption (Brodjonegoro, Citation2020). At this time, the impact of COVID-19 is being felt by all business units, both large companies and SMEs. Because in Indonesia, SMEs are a type of company that is more numerous than large companies, the problems experienced by SMEs will have a big impact on the country.

This leads to the research problem: How can Indonesian SMEs obtain additional resources to carry out ambidexterity? Therefore, the question regarding the problem of ambidexterity in SMEs will be the subject of this research. This study aims to answer the problem of resources to carry out ambidexterity in SMEs in Indonesia. Further, a literature review was carried out to analyze the existing literature to address the problem of ambidexterity in SMEs in Indonesia. Various studies on ambidexterity in SMEs will be synthesized into a framework to develop resources and capacity in SMEs to support ambidexterity.

2. Methodology

2.1. Data analysis

There are several stages of a systematic literature review (Tranfield et al., Citation2003). The first stage is developing research objectives and determining the review procedure. Based on previous research, it is known that the limited resources and capacity of SMEs are obstacles to carrying out ambidexterity (Carney, Citation2005; Hughes et al., Citation2017). This study synthesizes the literature on ambidexterity in SMEs to obtain a resource and capacity in SMEs to implement ambidexterity. The references for this study are taken from journal databases such as Google Scholar, JSTOR, Emerald Insights, Science Direct, Wiley, EBSCO, ProQuest, Springer, and Taylor & Francis, with Scopus levels Q1, Q2, Q3 and Q4. A quartile is determined by the Scimago Journal.

It consists of two categories namely conceptual and empirical research. The category is screened as follows: 1) Articles published from 1976–2023. 2) The article is included in the Scopus database starting Q1-Q4. This article filtering utilizes Publish or Perish software with the keywords ambidexterity, social network, exploration and exploitation, resources, Indonesia, and firm performance. To obtain relevant articles, the study also limited the context by entering the keyword small medium enterprise. Table describes the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the articles that will be critically analyzed in this review study. Assuming the article is frequently cited by other researchers, a citation cutoff of more than 50 is utilized with the literature review included in the Scopus database. Based on the initial screening results, 851 articles were obtained from 1976 to 2023.

Table 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The second stage is conducting an article review. This stage involved identifying, selecting, evaluating, and synthesizing pre-existing research. This stage is the initial process for identifying literature titles, abstracts, and keywords of research on ambidexterity between exploitation and exploration. From these criteria, 352 articles were sorted. 352 articles were scrutinized in more detail in terms of contents, hypotheses, constructs or measurement variables, and the theories, which discussed ambidexterity in a small-medium enterprise. These criteria were applied to the articles which were integrated to support the proposed models and propositions. After the analysis was carried out using the theory, 251 articles were selected, consisting of 11 conceptual articles, and 240 empirical research. Approximately 251 articles were read, tabulated, and sorted. The summary of the process is presented in Figure .

The same steps were taken for articles that only discussed ambidexterity in Indonesian SMEs. The criteria to consider in selecting literature are the terms such as ambidexterity, social network, exploration, exploitation, resources, Indonesia, and firm performance. To obtain relevant articles, the study also limited the context by entering the keyword Indonesian SMEs. Table describes the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the articles that will be critically analyzed in this review study. Based on the initial screening results, 117 articles were obtained from 1976 to 2023. The second stage is conducting an article review. This stage involved identifying, selecting, evaluating, and synthesizing pre-existing research. This stage is the initial process for identifying literature titles, abstracts, and keywords of research on ambidexterity between exploitation and exploration in Indonesian SMEs. From these criteria, 23 articles were sorted. 23 articles were scrutinized in more detail in terms of contents, hypotheses, constructs or measurement variables, and the theories, which discussed ambidexterity in Indonesian SMEs. These criteria were applied to the articles which were integrated to support the proposed models and propositions. After the analysis was carried out using the theory, 9 articles were selected, and approximately 9 articles were read, tabulated, and sorted.

Table 2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Ambidexterity in Indonesian SMEs

Due to the limited number of articles regarding ambidexterity in Indonesia, the researcher conducted two stages of literature analysis to obtain a more complete picture. In the first analysis, articles relating to the discussion of ambidexterity in Indonesian SMEs are merged into one with articles on ambidexterity in SMEs from other countries. In the second analysis, articles regarding the condition of ambidexterity in Indonesian SMEs, are analyzed separately.

The third stage is mapping and making reports on the results and themes of journal articles to propose a research model. This paper uses a bibliometric analysis approach to quantitatively analyze the performance of publications. Furthermore, the bibliometric analysis consists of three questions as follows: What research has been done in the field of ambidexterity in the context of SMEs, in terms of definitions, theories, and methodologies? What keywords are often used in ambidexterity research? What is the future research agenda in the ambidexterity research?

2.2. Result and discussion

The mapping results are shown in Figures , Figures , and Figure . Figure provides annual trends in the number of published articles from 1973 to 2023. The number of publications on ambidexterity has increased sharply since 1999. This highlights the fact that ambidexterity has gained increasing attention from the academic community. Ambidexterity to balance exploration and exploitation has been widely discussed in journals covering the fields of business and management. The main resource of publications was Organization Science, Strategic Management, Academy of Management Journal, Journal of Business Research, Journal of Business Venturing, and Journal of Knowledge Management. Figure is the distribution of journals which published the research in more than 2 papers.

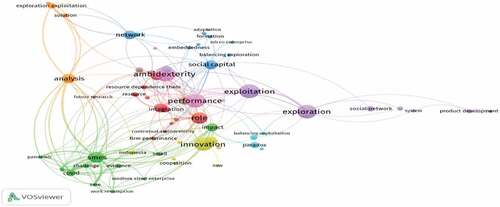

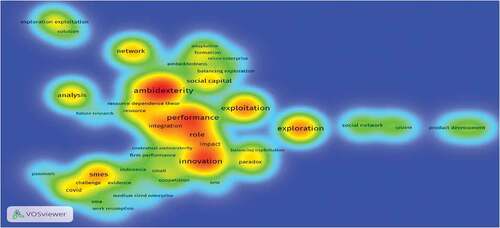

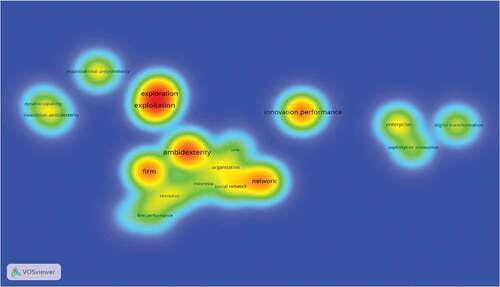

A keyword analysis is used to map words most frequently associated with ambidexterity. A large number indicates that the dimension has been frequently studied. The VOS viewer can classify keywords into different clusters. Extracting from the title and abstract fields, the minimum number of occurrences was set to 3. After the extraction, 851 terms and 95 items met the threshold, so that 9 groups were formed. Some keywords showed more prominent issues in the research on ambidexterity.

Figure is a graphic illustration of keywords which are quoted in many empirical articles on ambidexterity. The level of theme density is seen in Figure . Red and yellow clusters indicate a high level of density, which means that the theme has been widely studied. The more blurred colors in Figure indicate that the theme is still very rarely investigated empirically. Basically Figure confirms the results of the analysis in Figure , which shows that the theme of ambidexterity, innovation, and performance are most often cited as a keyword, followed by exploration and exploitation. Figure also indicates research opportunities which were conducted by researchers related to the theme. Social networks, resource, networks, resource dependence theory, and SMEs are rare areas to be studied in the research on ambidexterity. These areas can be potential research opportunities in future research in ambidexterity.

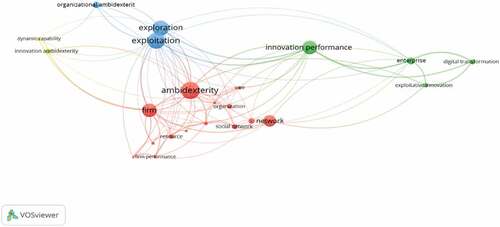

Figure shows research on ambidexterity in Indonesian SMEs that has only shown an increase starting in 2020. The list of journals that publish articles on ambidexterity in Indonesian SMEs is shown in Figure . The results of the analysis are based on the keyword which is quoted in empirical articles on ambidexterity in Indonesian SMEs, more and less show the same as the analysis of literature reviews regarding ambidexterity in various countries. Figure is a graphic illustration of keywords which are quoted in many empirical articles on ambidexterity. The level of theme density is seen in Figure . Red and yellow clusters indicate a high level of density, which means that the theme has been widely studied. The more blurred colors in Figure indicate that the theme is still very rarely investigated empirically. Figure confirms the results of the analysis in Figure , which shows that the theme of ambidexterity, innovation, exploration, exploitation, and innovation performance are most often cited as a keyword. Figure also indicates research opportunities which were conducted by researchers related to the theme. Social networks, resources, and SMEs are rare areas to be studied in the research on ambidexterity. These areas can be potential research opportunities in future research in ambidexterity. Table shows the analysis of potential concepts in ambidexterity research emerging from the 9 groups of keywords.

Table 3. Analysis of the Potential Concepts Emerging from the Subgroups

2.3. Various theories related to ambidexterity in selected literature

Many studies have explored theories and factors that influence ambidexterity. The literature review of 251 articles showed that the theories and perspectives used in ambidexterity studies are rooted in three categories, namely behavioral theory, social theory, and organization theory. Behavioral theory observes and measures human behavior. The behavioral theories used in ambidexterity research are leadership theory and learning theory. In leadership theory, ambidexterity can be achieved if managers have the ability to handle a lot of information and options for decisions, as well as deal with conflict and ambiguity (Cao et al., Citation2009; Lubatkin et al., Citation2006; Raisch & Birkinshaw, Citation2008; Tushman & O’reilly, Citation1996). The second theory in this category, namely learning theory, assumes that ambidexterity is the capacity of an organization to coordinate two opposing tasks simultaneously, which necessitates similar but distinct skills (Brix, Citation2019; Cao et al., Citation2009; Gupta et al., Citation2006; Ibidunni et al., Citation2020; Levinthal & March, Citation1993; March, Citation1991; Raisch & Birkinshaw, Citation2008; Simsek, Citation2009).

The second category is sociological theory. The sociological theory used in ambidexterity research is social network theory. According to social network theory, businesses must seek out the best network partner configuration in order to obtain the necessary resources (Bae & Gargiulo, Citation2004; Beckman et al., Citation2004; Expósito-Langa & Molina-Morales, Citation2010; Hoffmann, Citation2007; Indarti & Postma, Citation2013; Majid et al., Citation2020; Rothaermel & Deeds, Citation2004; Russo & Vurro, Citation2010; Shiri et al., Citation2015; Tiwana, Citation2008). The theories used in ambidexterity research are mostly in the third category, namely organizational theory. These categories include theories of dynamic capacity, innovation management, resource dependence theory, resource-based views, mechanistic and organic perspectives, absorptive capacity theories, strategic management, organizational design, resource orchestration theory, and contingency theory. Table shows the theories in the selected literature in this study.

Table 4. Used Theories in Ambidexterity Literature

2.4. Dimensions of exploration and exploitation

Ambidexterity is a dynamic capability that a company has (March, Citation1991; O’reilly & Tushman, Citation2013). Birkinshaw and Gupta (Citation2013) state that ambidexterity is an organization’s capability to manage contradictions and various pressures in the present and the future, achieve efficiency and effectiveness, optimize its existing assets, and make innovations. In addition, ambidexterity is also considered to be the dynamic capability to simultaneously explore and exploit resources (Birkinshaw & Gupta, Citation2013; March, Citation1991; O’reilly & Tushman, Citation2013; Priyanka et al., Citation2022; Teece et al., Citation2016; Teece, Citation2017). Capability, from a resource-based view, is the source of a company’s sustainable competitive advantage (Barney, Citation1991; Warnerfelt, Citation1984).

Often due to their limited resources and capabilities, SMEs have difficulties in balancing exploration and exploitation. To discuss the resource constraints problems faced by SMEs, this article will first analyze the meaning of exploration and exploitation from the selected literature in this study. There are several definitions of exploration and exploitation based on various pieces of literature. From these definitions, this study formulates several dimensions of exploration and exploitation. Table shows the dimensions of exploration and exploitation taken from the various definitions of exploration and exploitation. The first dimension is knowledge, in which exploration is defined as the act of finding new knowledge, while exploitation as the act of managing existing knowledge (Bengtsson & Johansson, Citation2014; Gibson & Birkinshaw, Citation2004; March, Citation1991; Nofiani et al., Citation2021). The second dimension is strategy, in which exploration is defined as creating something new, whereas exploitation is developing what already exists (He & Wong, Citation2004; Hughes et al., Citation2017; Voss & Voss, Citation2013; Yuan et al., Citation2021).

Table 5. Dimension of Exploration and Exploitation

Innovation is the third dimension, in which exploration is the process of creating radical innovations, while exploitation is the process of improvement (Amankwah-Amoah & Adomako, Citation2021; Birkinshaw & Gupta, Citation2013; Cho et al., Citation2019; Fu et al., Citation2021; Gnyawali et al., Citation2016; He & Wong, Citation2004; Jansen et al., Citation2012; Lubatkin et al., Citation2006; March, Citation1991; Senaratne & Wang, Citation2018). The fourth dimension is learning, in which exploration is defined as the act of learning through new alternative experiments, while exploitation is the act of learning through improving existing competencies (Gupta et al., Citation2006; Lubatkin et al., Citation2006). Customers is the fifth dimension, in which exploration is defined as attracting new customers and entering new markets, whereas exploitation is seen as increasing income from current customers and markets (He & Wong, Citation2004; Voss & Voss, Citation2013). The sixth dimension to understanding exploration and exploitation is a partnership. Exploration is when an organization adds new partners and relationships to its network, while exploitation is the act of strengthening the relationships with existing partners (Beckman et al., Citation2004; Hoffmann, Citation2007; Indarti & Postma, Citation2013; Kauppila, Citation2010; Lavie & Rosenkopf, Citation2006; Lavie et al., Citation2011; Lubatkin et al., Citation2006; Shiri et al., Citation2015; Stadler et al., Citation2014; Sun & Lo, Citation2014; Wilden et al., Citation2018).

Most articles in selected literature, discuss ambidexterity from the perspective of the RBV (Bengtsson & Johansson, Citation2014; Birkinshaw & Gupta, Citation2013; Cho et al., Citation2019; Gnyawali et al., Citation2016; He & Wong, Citation2004; Hughes et al., Citation2017; Ikhsan et al., Citation2017; Jansen et al., Citation2012; Lin et al., Citation2012; Lubatkin et al., Citation2006; March, Citation1991; Senaratne & Wang, Citation2018). Only a small number of the literature discusses exploration and exploitation as having relationships with partners in social networks (Beckman et al., Citation2004; Hoffmann, Citation2007; Indarti & Postma, Citation2013; Kauppila, Citation2010; Lavie & Rosenkopf, Citation2006; Lavie et al., Citation2011; Lubatkin et al., Citation2006; Shiri et al., Citation2015; Stadler et al., Citation2014; Sun & Lo, Citation2014; Wilden et al., Citation2018). In general, the RBV states that the source of a firm’s competitive advantage is a resource that is valuable, scarce, inimitable, non-substitutable, heterogeneous, and imperfectly mobile (Barley et al., Citation2018; Warnerfelt, Citation1984). This causes the company to only focus on internal resources and capabilities of the company, causing it to be a closed organization which emphasizes competition rather than cooperation (Lavie & Rosenkopf, Citation2006). When ambidexterity in SMEs is seen only from a resource-based view (RBV), the SMEs will experience a shortage of resources so ambidexterity becomes difficult to implement (Lavie, Citation2006; Voss & Voss, Citation2013). This suggests that ambidexterity in SMEs requires another perspective to complement RBV.

2.5. Mapping the ambidexterity strategy

From the analysis in Figures , it can be said that the implementation of social networks is an opportunity that can be done if SMEs want to obtain additional resources. In large companies, which have large resources, the implementation of ambidexterity uses a structural strategy, with separate divisions to deal with exploration and exploitation strategies (Hughes, Citation2018; Knight & Harvey, Citation2015; Randall et al., Citation2017). This will be difficult to do in small companies because they usually have limited resources (Hughes et al., Citation2017; Senaratne & Wang, Citation2018). In small companies, the usual strategy is contextual ambidexterity and relationship ambidexterity. Contextual ambidexterity suggests that ambidexterity can be managed well if the organization creates a context in which the individuals in it carry out exploration and exploitation simultaneously (Gibson & Birkinshaw, Citation2004; Tushman & O’reilly, Citation1996). Relationship strategy is the application of ambidexterity by collaborating with external parties, so it shows that building a social network is one of the strategies for SMEs to do ambidexterity (Gibson & Birkinshaw, Citation2004; Tushman & O’reilly, Citation1996).

Figure shows various strategies for implementing ambidexterity from the continuum/orthogonal perspectives and corporate size. There are two perspectives regarding the implementation of ambidexterity, namely the continuum perspective and the orthogonal perspective (He & Wong, Citation2004; Hughes, Citation2018). The first perspective is a view that considers exploration and exploitation to be at different angles of a continuum (Hughes, Citation2018; March, Citation1991). Both of them are trade-offs so that they cannot be carried out to the maximum extent, simultaneously (Hughes et al., Citation2017; Hughes, Citation2018; Knight & Harvey, Citation2015; March, Citation1991; Randall et al., Citation2017). From the continuum perspective, the integration of exploration and exploitation is carried out by focusing on the balance between exploration and exploitation (Raisch & Birkinshaw, Citation2008; Raisch et al., Citation2009).

Figure 10. Mapping the Ambidexterity Strategy.

The second perspective is the orthogonal perspective. This perspective focuses on the concept of complementarity between exploration and exploitation (Aliasghar & Haar, Citation2021; Cao et al., Citation2009; Gupta et al., Citation2006). The orthogonal perspective assumes that exploration and exploitation are not at two different ends of the continuum, so they are not trade-offs. Exploration and exploitation are simultaneously and equally strong (Hughes et al., Citation2017; Hughes, Citation2018). Companies only can carry out equally powerful exploration and exploitation activities simultaneously if they have large amounts of resources or have access to partner resources in a network (Cao et al., Citation2009; Lavie & Rosenkopf, Citation2006; Simsek, Citation2009).

From the continuum perspective, the ambidextrous strategies that should be used are structural ambidexterity (Gupta et al., Citation2006; March, Citation1991) and temporary ambidexterity (Sun & Lo, Citation2014). With structural ambidexterity, the organization forms different structures for exploration and exploitation, then both structures perform simultaneously in the organization (Gupta et al., Citation2006; March, Citation1991). In addition to being carried out structurally, ambidexterity from the continuum perspective is carried out by temporarily alternating between exploration and exploitation (Benner & Tushman, Citation2003; Lavie et al., Citation2011; Sun & Lo, Citation2014). In the implementation of the ambidextrous strategy of temporarily alternating between exploration and exploitation, the problem that occurs is managing the change of strategy so that it runs smoothly and does not create confusion among the employees (Benner & Tushman, Citation2003; García-Hurtado et al., Citation2022; Hughes, Citation2018; Sun & Lo, Citation2014).

The ambidextrous strategies from the orthogonal perspective are contextual ambidexterity (Hughes, Citation2018; Ikhsan et al., Citation2017) and relationship ambidexterity (Jansen et al., Citation2012; Simsek, Citation2009). Contextual ambidexterity suggests that trade-offs can be managed well if the organization creates a context in which the individuals in it carry out exploration and exploitation simultaneously (Gibson & Birkinshaw, Citation2004; Tushman & O’reilly, Citation1996). In addition to being managed contextually, based on the orthogonal perspective, ambidexterity can be undertaken in a synchronized manner (Ali et al., Citation2022; Gulati & Sytch, Citation2007; Gunsel et al., Citation2017; Gupta et al., Citation2006; He & Wong, Citation2004; Kauppila, Citation2010; Lavie & Rosenkopf, Citation2006; Lavie et al., Citation2011; Russo & Vurro, Citation2010; Stadler et al., Citation2014).

Synchronization strategy can be chosen because SMEs with limited resources will find it difficult to use structural or temporary strategies (Agyapong et al., Citation2018; Borgatti & Halgin, Citation2011; Gnyawali & Park, Citation2009, Citation2011; Gnyawali et al., Citation2016; Hameed et al., Citation2021; Ioanid et al., Citation2018; Sun & Lo, Citation2014). In this strategy, SMEs synchronization exploration and exploitation across function, level, and organization. Synchronization strategy also allows SMEs to work with other organizations to implementation ambidexterity (Cao et al., Citation2009; Lavie & Rosenkopf, Citation2006; Lavie et al., Citation2011; Lavie, Citation2006; Simsek, Citation2009). This shows the fact that every organization is interdependent on each other (Jansen et al., Citation2006, Citation2012; Simsek, Citation2009).

3. Direction for future research

The results of the mapping of ambidexterity in terms of exploration and exploitation show that most of the literature only uses the RBV perspective when discussing ambidexterity to balance exploration and exploitation (Bengtsson & Johansson, Citation2014; Birkinshaw & Gupta, Citation2013; Burvill et al., Citation2018; Cho et al., Citation2019; Gnyawali et al., Citation2016). The RBV perspective will result in SMEs only relying on limited internal resources so that ambidexterity is difficult to do (Bengtsson & Johansson, Citation2014; Hilman et al., Citation2009; Hughes, Citation2018). To overcome the lack of internal resources, SMEs need to get resources from external parties and establish relationships with them (Agyapong et al., Citation2018; Hilman et al., Citation2009; Ioanid et al., Citation2018; Tehseen & Sajilan, Citation2016). The results of the literature analysis show that exploration and exploitation capabilities can be obtained by establishing relationships with external parties and forming social networks (Hughes, Citation2018; Kauppila, Citation2010; Lavie et al., Citation2011; Lavie, Citation2006; Wilden et al., Citation2018).

In Figures , from the literature review, it can be seen that the research topic regarding the relationship between ambidexterity and social networks is a rarely-researched topic which provides a wide range of opportunities for future research. This is supported by the results of strategy mapping conducted by researchers. One strategy to perform ambidexterity is the synchronization strategy (Lavie & Rosenkopf, Citation2006; Lavie et al., Citation2011; Simsek, Citation2009). The strategy states that SMEs need to cooperate with other organizations and form networks to obtain external resources (Hughes, Citation2018; Lavie et al., Citation2011).

Based on the analysis of the literature, this study uses two perspectives to complement the RBV to address resource-related issues in the implementation of ambidexterity in SMEs. They are resource dependence theory (RDT) and social network theory (Hilman et al., Citation2009; Pfeffer & Salancik, Citation2003; Tehseen & Sajilan, Citation2016). Resource dependence theory is deeply rooted in sociology and political science (Pfeffer & Salancik, Citation2003; Tehseen & Sajilan, Citation2016). In this perspective, a successful organization is an organization that can maximize organizational power by controlling critical resources (Tehseen & Sajilan, Citation2016). Organizations are seen as partnerships that change structures and patterns of behavior to obtain and maintain needed external resources (Bae & Gargiulo, Citation2004; Chiu, Citation2008; Zhang et al., Citation2018).

The resource dependence perspective is based on three assumptions (Hilman et al., Citation2009; Tehseen & Sajilan, Citation2016). The first assumption, the organization consists of internal and external cooperation. Cooperation arises from social exchanges that are formed to influence and control the behavior of the parties involved. Second, the environment is considered to have rare and important valuable resources for the survival of the organization. Third, the organization is considered to be working towards two objectives related to the environment, namely, a) obtaining control over resources that minimizes its dependence on other organizations and b) obtaining control over resources that maximizes the dependence of other organizations on the organization (Hilman et al., Citation2009).

In contrast to RBV that focuses solely on internal resources, RDT considers organizations as open systems, thus assuming that the external environment can provide the essential resources needed by the organization (Hilman et al., Citation2009; Pfeffer & Salancik, Citation2003; Shymko & Diaz, Citation2012; Tehseen & Sajilan, Citation2016; Zhang et al., Citation2018). To get additional resources, an organization needs to have a strategy to build relationships with external parties (Hilman et al., Citation2009; Ioanid et al., Citation2018). Currently, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused major changes in the environment, so that SMEs cannot rely solely on their internal resources to deal with it (Hillman et al., Citation2009; Papadopoulos et al., Citation2020). According to the assumptions in the RDT, organizations respond to environmental uncertainty by managing relationships between organizations to acquire resources (Gaffney et al., Citation2013; Ioanid et al., Citation2018; Kamboj et al., Citation2017; Pfeffer & Salancik, Citation2003). Table shows the research supporting RDT in the literature selected for this study.

Table 6. Prior Studies that Supported Resource Dependence Theory

The other perspective is social networking. In social networking, a network is a structure of actors or “nodes” referred to as individuals, departments, groups, ora company. Actors are connected and often referred to as ties or connections (Datta, Citation2011; Liu et al., Citation2017). The number of reasons for connecting with other actors may include friendship, common interest, interdependency, or other benefits. Actors can be managed by another actor in a one-directional effect when advising another individual. Also, actors can have an indirect effect based on physical proximity to other actors. Actors can have dichotomous connections with other actors whether they are present or absent or whether they have a friendship or not (Bengtsson & Johansson, Citation2014; Liu et al., Citation2017). One way to establish good relations between actor (individuals, departments, groups, ora company) with external parties is by creating social networks so that they can access and obtain resources from each other (Ahuja, Citation2000; Hilman et al., Citation2009; Majid et al., Citation2020; Sherer & Lee, Citation2002; Tehseen & Sajilan, Citation2016). Table shows the research supporting social network theory in the literature selected for this study. Research on ambidexterity in SMEs in the future, should broaden the perspective of resources not only using internal resources but also being able to utilize resources from external partners from social networks (Ibidunni et al., Citation2020; Ioanid et al., Citation2018; Majid et al., Citation2020; Rogan & Mors, Citation2015; Shiri et al., Citation2015; Tehseen & Sajilan, Citation2016). Figure shows the framework of these recommendations.

Table 7. Prior Studies that Supported Social Network Theory

4. Proposition

4.1. Components in social network and ambidexterity in SMEs

Borgatti and Halgin (Citation2011) state that social networks have components, namely the diversity of the members of the network and the ties that connect them. External resources can be obtained by managing the diversity of external partners and the ties that exist with external partners (Agyapong et al., Citation2018; Burvill et al., Citation2018).

4.2. Diversity of ties

Diversity of ties shows the company’s relationship with outsiders who can provide resources that are not redundant (Parida et al., Citation2015). Shiri et al. (Citation2015) states that the diversity of ties shows the company’s ties with heterogeneous partners. Heterogeneous partners can contribute to providing various resources, information, and knowledge for ambidexterity to balance exploration and exploitation in SMEs (Datta, Citation2011; Indarti & Postma, Citation2013; Rogan & Mors, Citation2015; Shiri et al., Citation2015). Various external parties can bond with SMEs, namely competitors, suppliers, consumers, consultants, business associations, religious associations, universities, and government agencies (De Leeuw et al., Citation2014; Indarti & Postma, Citation2013; Van Beers & Zand, Citation2013).

The more diverse the ties with SMEs’ external partners, the more diverse the knowledge and information that SMEs can obtain (Expósito-Langa & Molina-Morales, Citation2010; Indarti & Postma, Citation2013; Shiri et al., Citation2015). Diverse knowledge and resources allow companies to explore, creating new combinations of technology, producing new experiments, inventions, and product variations (Lazer & Friedman, Citation2007; McEvily & Zaheer, Citation1999; Rodan & Galunic, Citation2004; Shiri et al., Citation2015; Wang & Rafig, Citation2014). Conversely, less diverse ties with partners will cause SMEs to exploit, by strengthening and expanding existing knowledge, increasing efficiency, increasing production, and improving current products (March, Citation1991; Rodan & Galunic, Citation2004; Rogan & Mors, Citation2015).

High diversity has a positive effect on performance if SMEs can do ambidexterity. The higher the diversity of partners, the more available new knowledge to complement existing knowledge (Simsek, Citation2009). In addition, high diversity causes SMEs not only to exploit existing businesses but also to explore, resulting in ambidexterity between exploration and exploitation (Lavie & Rosenkopf, Citation2006; Lin et al., Citation2012). SMEs will have the opportunity to discover new markets, innovations, and new customers, so they don’t just exploit existing customers. The ambidexterity of exploration and exploitation will enable SMEs to innovate and at the same time maintain existing businesses (Lavie & Rosenkopf, Citation2006; Lavie et al., Citation2011; Lin et al., Citation2012; Wilden et al., Citation2018).

Proposition 1:

Ambidexterity mediates the effect of diversity of ties on firm performance.

4.3. The strength of bonds

The second component of the social network is the bonds between partners in the network. The strength of the bonds between partners can affect the flow of resources and information in the network. The strength of bonds shows the amount of interaction time (frequency), emotional intensity, relationship intimacy, and mutually beneficial relationships that can provide resources for ambidexterity in balancing exploration and exploitation (Expósito-Langa & Molina-Morales, Citation2010). The more interaction time between partners, the more possibilities there are for sharing and accessing knowledge from other parties (Granovetter, Citation1985, Citation2005; Indarti & Postma, Citation2013; Molina-Morales & Martínez-Fernández, Citation2010). When the bond becomes more intensive, the quality of knowledge exchange increases, so that the bond becomes stronger (Granovetter, Citation1977, Citation1983).

Strong bonds between individuals facilitate the flow of information and knowledge, but they will lead to redundant information and knowledge (Gedajlovic et al., Citation2013; Granovetter, Citation2005). This will increase the accumulation of existing knowledge or lead to the exploitation of existing knowledge and information. Conversely, a weak bond will provide more diverse information, giving rise to exploration for the discovery of new ideas (Granovetter, Citation1977, Citation1983, Citation1985). The weaker the intensity of the bonds that SMEs make with partners, the greater the opportunities for exploratory learning and acquiring new knowledge (Burt, Citation1992; Gedajlovic et al., Citation2013; Granovetter, Citation2005).

March (Citation1991) states that exploitation without exploration causes SMEs to be unable to respond to changes in demand and fail to recognize the needed product and process improvements. Conversely, SMEs that focus too much on exploration will face large costs, risk of failure, and reduced profits from exploiting the products they currently have (Lavie & Rosenkopf, Citation2006; Lavie et al., Citation2011; Wilden et al., Citation2018). Therefore, a combination of ambidexterity between exploration and exploitation is needed, thereby reducing excessive dependence on exploration or exploitation by companies (Lavie & Rosenkopf, Citation2006; Lin et al., Citation2012).

Company performance will increase when SMEs can do ambidexterity and not only exploit the existing business (Lavie & Rosenkopf, Citation2006; Lavie, Citation2006). The intensity of SMEs’ bonds with partners in the network will improve performance if SMEs can combine exploration and exploitation (Lavie & Rosenkopf, Citation2006; Wilden et al., Citation2018). Exploitation will strengthen existing businesses, while exploration will enable SMEs to take on new opportunities in business (Lavie et al., Citation2011; Lavie, Citation2006; Lin et al., Citation2012; Wilden et al., Citation2018).

Proposition 2:

Ambidexterity mediates the effect of the strength of bonds on firm performance.

4.4. Multiple types of ties

The third characteristic of social networks is their multiple ties (Brown & Konrad, Citation2001; Hoffmann, Citation2007; Indarti & Postma, Citation2013; Kenis & Knoke, Citation2002; Rothaermel & Deeds, Citation2004; Rowley et al., Citation2000). Multiple ties refer to the various types of ties between SMEs and external partners, namely transaction ties, friendship ties, and advice or suggestions (Claro et al., Citation2012; Kapucu & Hu, Citation2014; Tuli et al., Citation2010). Multiple ties result in various kinds of simultaneous messages to establish bonds between the company and its external partners, which happens because there are various roles played by SMEs in the complexity of the ties (Claro et al., Citation2012; Kapucu & Hu, Citation2014). For example, the relationship between SMEs and suppliers will be called multiplex if apart from being a buyer of the supplier, the company is also good friends with the supplier, resulting in transaction and friendship relationships, thereby creating mutual trust and mutual support (Claro et al., Citation2012; Ross & Robertson, Citation2007; Tuli et al., Citation2010).

The bond of multiple types of ties causes SMEs to absorb various kinds of information and knowledge that can affect ambidexterity in balancing exploration and exploitation (Claro et al., Citation2012; Indarti & Postma, Citation2013; Tuli et al., Citation2010). The complexity of the relationship provides the exchange of knowledge, various types of bonds between partners in the network, and the depth and diversity of knowledge that can be absorbed by organizations from various external parties (Indarti & Postma, Citation2013; Kapucu & Hu, Citation2014; Sosa, Citation2011). The more multiple roles there are in the relationship between one member and another in the network, the higher the multiple types of ties will be (Kapucu & Hu, Citation2014; Tichy et al., Citation1979). The high multiple types of ties create opportunities to explore various areas of knowledge from partners in-depth, thus encouraging innovation. In contrast, the low multiple types of ties only strengthen existing knowledge and information, thus leading to the development and improvement of current products and services (Datta, Citation2011; Rothaermel & Deeds, Citation2004; Tuli et al., Citation2010).

When there are many multiplex relationships between companies in a network, more knowledge will emerge (Ross & Robertson, Citation2007; Tuli et al., Citation2010). This is because collaboration with different partners influences the amount and variety of knowledge and increases exploration (Ross & Robertson, Citation2007). SMEs that can manage the multiplex relationship, will gain exploration capabilities. To improve performance, SMEs need to explore to complement the exploitation of their current business (Datta, Citation2011). The ability to carry out exploration and exploitation ambitions will enable SMEs to create new opportunities and knowledge that can complement the current business and knowledge of SMEs. The ability to innovate and new opportunities while maintaining existing businesses will improve SMEs’ innovation performance (March, Citation1991; Tuli et al., Citation2010; Wilden et al., Citation2018).

Proposition 3:

Ambidexterity mediates the effect of multiple types of ties on firm performance.

5. Implications and limitation

The results of the literature analysis provide a theoretical contribution to the discussion regarding ambidexterity in SMEs. RBV’s perspective is not enough to discuss ambidexterity in SMEs, because RBV only emphasizes internal resources. This perspective will make SMEs closed so that they only rely on limited internal resources. Limited resources are one of the obstacles to implementing ambiguity in SMEs. In this article, there are two perspectives used to complement the RBV perspective, namely the RDT perspective and the social network perspective. Both perspectives use an outside-in view, thus complementing the RBV perspective, which uses an inside-out view when discussing ambiguity.

Apart from theoretical implications, the results of this literature review also have practical implications. To deal with the impact of COVID-19, SMEs need to collaborate with external parties and form networks (Bengtsson & Johansson, Citation2014). Such networks can overcome shortages and uncertainties in terms of resources (Pfeffer & Salancik, Citation2003; Tehseen & Sajilan, Citation2016). SMEs that have social networks will have partners who can be invited to work together to exchange resources and knowledge so that the need for external resources and knowledge can be met (Ahuja, Citation2000; Hoffmann, Citation2007; Rothaermel & Deeds, Citation2004).

This study has certain limitations. There are only a few studies on ambidexterity in Indonesia and there are only some articles on the topic. The author has tried to overcome these problems by conducting two stages of literature review. In the first stage, the authors analyze the ambidexterity of SMEs in various countries, including Indonesia. While in the second stage, the authors analyze ambidexterity only in the context of SMEs in Indonesia based on a few articles that meet the criteria. The results of the analysis using bibliometrics do produce more or less the same conclusions. However, if there are quite many research articles on ambidexterity in Indonesia, it is better to do a more in-depth re-analysis specifically on the literature on ambidexterity in Indonesian SMEs to obtain a more specific picture of ambidexterity. In Indonesian SMEs.

6. Conclusion

This article shows the gap between the literature and the application of ambidexterity in Indonesian SMEs. Based on the literature review, two things can be concluded. First, the discussion of ambidexterity has a lot to do with innovation performance, but only a few studies have discussed the relationship between ambidexterity and the resources required to do so. Second, the results of keyword mapping using VOSviewer show that research linking ambidexterity with resource dependence theory (RDT) and social networks is rare. This result is the same as the result of the theory mapping that underlies the ambidexterity concept to balance exploration and exploitation, which is dominated by RBV theory so that it only focuses on internal resources and competition among companies.

Implementing ambidexterity by small and medium-sized enterprises cannot rely solely on their internal resources and the use of RBV alone. This happens because SMEs are usually family-owned companies with limited resources (Carney, Citation2005; Lavie & Rosenkopf, Citation2006). SMEs need to build social networks to get opportunities to access and obtain external resources from partners in their networks (Gnyawali & Park, Citation2009, Citation2011; Gnyawali et al., Citation2016). This can be done if the owners or managers of SMEs use the RDT perspective so that they view the organization as an open system. The RDT perspective assumes that the external environment can provide the essential resources needed by the organization (Hilman et al., Citation2009; Pfeffer & Salancik, Citation2003; Tehseen & Sajilan, Citation2016; Zhang et al., Citation2018).

One way to establish good relations with external parties is by creating social networks with them to access and obtain resources from each other (Ahuja, Citation2000; Hilman et al., Citation2009; Sherer & Lee, Citation2002; Tehseen & Sajilan, Citation2016). Social networks emphasize an external (outside-in) perspective to complement an internal (inside-out) perspective in a resource-based view (Datta, Citation2011; Tichy et al., Citation1979). This paper contributes to clarifying the gap between the RBV perspectives to underlie ambidexterity in Indonesian SMEs. In future research, RBV needs to be complemented by RDT and social networks to address resource-related problems faced by SMEs.

In addition to including components in social networks, future ambidexterity research should also consider cross-organizational ambidexterity (Hughes, Citation2018; Lavie et al., Citation2011; Wilden et al., Citation2018). Using a synchronization strategy, organizations can perform ambidexterity across organizational boundaries. Birkinshaw and Gupta (Citation2013), Jansen et al. (Citation2012), and Simsek (Citation2009) state that ambidexterity is a concept that can cross various levels, functions, and boundaries between organizations. This can happen when organizations form networks and depend on each other for resources (Jansen et al., Citation2012; Simsek, Citation2009). The organization’s ability to carry out ambidexterity can be achieved by developing the organization’s internal specialization and synchronizing with external partners who have different specializations (Gupta et al., Citation2006; He & Wong, Citation2004; Kauppila, Citation2010; Lavie & Rosenkopf, Citation2006; Lavie et al., Citation2011; Stadler et al., Citation2014).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Universitas Gadjah Mada under the Directorate of Research Program, Final Project Recognition Program (Rekognisi Tugas Akhir).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maria Pampa Kumalaningrum

Maria Pampa Kumalaningrum is a doctoral student in Department of Management, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Gadjah Mada. She is also a Lecturer in Department of Management, STIE YKPN. Her research interest includes innovation and operations, entrepreneurship, strategic management, and ambidexterity. Maria Pampa Kumalaningrum is the corresponding author and can be contacted at: [email protected] or [email protected].

Wakhid Slamet Ciptono

Wakhid Slamet Ciptono is an Associate Professor and Full-time Senior Lecturer in Department of Management, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Gadjah Mada. He holds a Ph.D degree from the University of Malaya, Malaysia. His research interest includes strategic management, innovation and operations, entrepreneurship, and supply-demand chain management.

Nurul Indarti

Nurul Indarti is a Professor and Full-time Senior Lecturer in Department of Management, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia. She holds a Ph.D degree from the Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Groningen, The Netherlands. Her research interest includes innovation and knowledge management, entrepreneurship, small and medium-sized business.

Boyke Rudy Purnomo

Boyke Rudy Purnomo is an Assistant Professor and Full-time Senior Lecturer in Department of Management, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Gadjah Mada. He holds a Ph.D degree from the University of Agder, Norwegian. His research interest includes entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial finance, business assessment, project management, and risk management.

References

- Agyapong, A., Mensah, H. K., & Ayuuni, A. M. (2018). The moderating role of social network on the relationship between innovative capability and performance in the hotel industry. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 13(5), 801–36. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJoEM-11-2016-0293

- Ahuja, G. (2000). The duality of collaboration: Inducements and opportunities in the formation of interfirm linkages. Strategic Management Journal, 21, 317–343. https://doi.org/10.1002/SICI1097-026620000321:3<317:AID-SMJ90>3.0.CO;2-B

- Aliasghar, O., & Haar, J. (2021). Open innovation: Are absorptive and desorptive capabilities complementary? International Business Review, 32(2), 101865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2021.101865

- Ali, M., Shujahat, M., Ali, Z., Kianto, A., Wang, M., & Bontis, N. (2022). The neglected role of knowledge assets interplay in the pursuit of organisational ambidexterity. Technovation, 114, 102452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2021.102452

- Amankwah-Amoah, J., & Adomako, S. (2021). The effects of knowledge integration and contextual ambidexterity on innovation in entrepreneurial ventures. Journal of Business Research, 127, 312–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.01.050

- Amit, R., & Schoemaker, P. J. H. (1993). Strategic assets and organizational rent: Strategic assets. Strategic Management Journal, 14(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250140105

- Andrade, J., Franco, M., & Mendes, L. (2022). Facilitating and inhibiting effects of organisational ambidexterity in SME: An analysis centred on SME characteristics. Journal of the Knowledge Economy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-021-00831-9

- Andriopoulos, C., & Lewis, M. W. (2009). Exploitation-exploration tensions and organizational ambidexterity: Managing paradoxes of innovation. Organization Science, 20(4), 696–717. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1080.0406

- Arnold, T. J., Fang, E., & Palmatier, R. W. (2011). The effects of customer acquisition and retention orientations on a firm’s radical and incremental innovation performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(2), 234–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-010-0203-8

- Atuahene-Gima, K., Slater, S. F., & Olson, E. M. (2005). The contingent value of responsive and proactive market orientations for new product program performance. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 22(6), 464–482. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5885.2005.00144.x

- Bae, J., & Gargiulo, M. (2004). Partner substitutability, alliance network structure, and firm profitability in the telecommunications industry. Academy of Management Journal, 47(6), 843–859. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159626

- Barley, W. C., Treem, J. W., & Kuhn, T. (2018). Valuing multiple trajectories of knowledge: A critical review and agenda for knowledge management research. The Academy of Management Annals, 12(1), 278–317. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2016.0041

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

- Beckman, C. M., Philips, D. J., & Haunschild, P. R. (2004). Friends or strangers? Firm-Specific Uncertainty, Market Uncertainty, and Network Partner Selection: Organization Science, 15(3), 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1040.0065

- Bengtsson, M., & Johansson, M. (2014). Managing coopetition to create opportunities for small firms. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 32(4), 401–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242612461288

- Benner, M. J., & Tushman, M. L. (2003). Exploration, exploitation, and process management: The productivity dilemma revisited. Academy of Management Review, 28(2), 238–256. https://doi.org/10.2307/30040711

- Benner, M. J., & Tushman, M. L. (2015). Reflections on the 2013 decade award—“Exploitation, exploration, and process management: The productivity dilemma revisited” ten years later. Academy of Management Review, 40(4), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2015.0042

- Birkinshaw, J., & Gupta, K. (2013). Clarifying the distinctive contribution of ambidexterity to the field of organization studies. Academy of Management Perspectives, 27(4), 287–298. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2012.0167

- Borgatti, S. P., & Halgin, D. S. (2011). On network theory. Organization Science, 22(5), 1168–1181. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0641

- Brix, J. (2019). Ambidexterity and organizational learning: Revisiting and reconnecting the literatures. The Learning Organization, 26(4), 337–351. https://doi.org/10.1108/TLO-02-2019-0034

- Brodjonegoro, B. (2020, September 4). Riset dan Inovasi Menuju Tatanan Kenormalan Baru. RISTEK-BRIN.

- Brown, D. W., & Konrad, A. M. (2001). Granovetter was right. The importance of weak ties to a contemporary job search. Group & Organization Management, 26(4), 434–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601101264003

- Burt, R. S. (1992). Structural holes: The social structure of competition. Harvard University Press.

- Burvill, S. M., Jones-Evans, D., & Rowlands, H. (2018). Reconceptualising the principles of Penrose’s (1959) theory and the resource based view of the firm: The generation of a new conceptual framework. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 25(6), 930–959. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-11-2017-0361

- Cao, Q., Gedajlovic, E., & Zhang, H. (2009). Unpacking organizational ambidexterity: Dimensions, contingencies, and synergistic effects. Organization Science, 20(4), 781–796. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0426

- Carney, M. (2005). Corporate governance and competitive advantage in family–controlled firms. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 29(3), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00081.x

- Chang, Y. Y., & Hughes, M. (2012). Drivers of innovation ambidexterity in small- to medium-sized firms. European Management Journal, 30(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2011.08.003

- Chesbrough, H. W., & Appleyard, M. M. (2007). Open innovation and strategy. California Management Review, 50(1), 56–77. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166416

- Chiu, Y. T. H. (2008). How network competence and network location influence innovation performance. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 24(1), 46–55. https://doi.org/10.1108/08858620910923694

- Chiu, Y. T. H. (2009). How network competence and network location influence innovation performance. The Journal of Business, 24(1), 10

- Cho, M., Bonn, M. A., & Han, S. J. (2019). Innovation ambidexterity: Balancing exploitation and exploration for startup and established restaurants and impacts upon performance. Industry and Innovation, 27(4), 340–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2019.1633280

- Chu, Y., Chi, M., Wang, W., & Luo, B. (2019). The impact of information technology capabilities of manufacturing enterprises on innovation performance: Evidences from SEM and fsQCA. Sustainability, 11(21), 5946. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215946

- Claro, D. P., Gonzalez, G. R., & Claro, P. B. O. (2012). Network centrality and multiplexity: A study of sales performance. Journal on Chain and Network Science, 12(1), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.3920/JCNS2012.x208

- Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393553

- Datta, A. (2011). Review and extension on ambidexterity: A theoretical model integrating networks and absorptive capacity. Journal of Management and Strategy, 2(1), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.5430/jms.v2n1p2

- De Leeuw, T., Lokshin, B., & Duysters, G. (2014). Returns to alliance portfolio diversity: The relative effects of partner diversity on firm’s innovative performance and productivity. Journal of Business Research, 67(9), 1839–1849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.12.005

- Expósito-Langa, M., & Molina-Morales, F. X. (2010). How relational dimensions affect knowledge redundancy in industrial clusters. European Planning Studies, 18(12), 1975–1992. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2010.515817

- Farzaneh, M., Wilden, R., Afshari, L., & Mehralian, G. (2022). Dynamic capabilities and innovation ambidexterity: The roles of intellectual capital and innovation orientation. Journal of Business Research, 148, 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.04.030

- Fu, X., Luan, R., Wu, H. -H., Zhu, W., & Pang, J. (2021). Ambidextrous balance and channel innovation ability in Chinese business circles: The mediating effect of knowledge inertia and guanxi inertia. Industrial Marketing Management, 93, 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.11.005

- Gaffney, N., Kedia, B., & Clampit, J. (2013). A resource dependence perspective of EMNE FDI strategy. International Business Review, 22(6), 1092–1100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2013.02.010

- García-Hurtado, D., Devece, C., Zegarra-Saldaña, P. E., & Crisanto-Pantoja, M. (2022). Ambidexterity in entrepreneurial universities and performance measurement systems. A literature review. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-022-00795-5

- Gedajlovic, E., Honig, B., Moore, C. B., Payne, G. T., & Wright, M. (2013). Social capital and entrepreneurship: A schema and research agenda. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 37(3), 455–478. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12042

- Gibson, C. B., & Birkinshaw, J. (2004). The antecedents, consequences and mediating role of organizational ambidexterity. Academy of Management Journal, 47(2), 209–226. https://doi.org/10.5465/20159573

- Gnyawali, D. R., Madhavan, R., He, J., & Bengtsson, M. (2016). The competition–cooperation paradox in inter-firm relationships: A conceptual framework. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.11.014

- Gnyawali, D. R., & Park, B. Y. R. (2009). Coopetition and technological innovation in small and medium sized enterprises: A multilevel conceptual model. Journal of Small Business Management, 47(3), 308–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2009.00273.x

- Gnyawali, D. R., & Park, B. Y. R. (2011). Coopetition between giants: Collaboration with competitiors for technological innovation. Research Policy, 40(5), 650–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.01.009

- Granovetter, M. S. (1977). The strength of weak ties. In Social Networks (pp. 347–367). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-442450-0.50025-0

- Granovetter, M. S. (1983). The strength of weak ties: A network theory revisited. Sociological Theory, 1, 201–233. https://doi.org/10.2307/202051

- Granovetter, M. S. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. The American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510. https://doi.org/10.1086/228311

- Granovetter, M. S. (2005). The impact of social structure on economic outcomes. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(1), 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1257/0895330053147958

- Gulati, R., & Sytch, M. (2007). Dependence asymmetry and joint dependence in interorganizational relationships: Effects of embeddedness on a manufacturer’s performance in procurement relationships. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(1), 32–69. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.52.1.32

- Gunsel, A., Altindag, E., Keceli, S. K., Kitapci, H., & Hiziroglu, M. (2017). Antecedents and consequences of organizational ambidexterity: The moderating role of networking. Emerald Publishing Limited, 0368–492X: https://doi.org/10.1108/K-02-2017-0057

- Gupta, A. K., Smith, K. G., & Shalley, C. E. (2006). The interplay between exploration and exploitation. Academy of Management Journal, 49(4), 693–706. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.22083026

- Hameed, W. U., Nisar, Q. A., & Wu, H. -C. (2021). Relationships between external knowledge, internal innovation, firms’ open innovation performance, service innovation and business performance in the Pakistani hotel industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 92, 102745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102745

- He, Z. L., & Wong, P. K. (2004). Exploration vs. exploitation: An empirical test of the ambidexterity hypothesis. Organization Science, 15(4), 481–494. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1040.0078

- Hillman, A. J., Withers, M. C., & Collins, B. J. (2009). Resource dependence theory: A review. Journal of Management, 35(6), 1404–1427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309343469/

- Hilman, A. J., Withers, M. C., & Collins, B. J. (2009). Resource dependence theory: A review. Journal of Management, 35(6), 1404–1427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309343469

- Hoffmann, W. H. (2007). Strategies for managing a portfolio of alliances. Strategic Management Journal, 28(8), 827–856. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.607

- Huang, S., Chen, J., & Liang, L. (2018). How open innovation performance responds to partner heterogeneity in China. Management Decision, 56(1), 26–46. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-04-2017-0452

- Hughes, M. (2018). Organisational ambidexterity and firm performance: burning research questions for marketing scholars. Journal of Marketing Management, 34(1–2), 178–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2018.1441175

- Hughes, M., Filser, M., Harms, R., Kraus, S., Chang, M. -L., & Cheng, C. -F. (2017). Family firm configurations for high performance: The role of entrepreneurship and ambidexterity: Family firm configurations. British Journal of Management, 29(4), 595–612. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12263

- Ibidunni, A. S., Kolawole, A. I., Olokundun, M. A., & Ogbari, M. E. (2020). Knowledge transfer and innovation performance of small and medium enterprises (SMEs): An informal economy analysis. Heliyon, 6(8), e04740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04740

- Iborra, M., Safón, V., & Dolz, C. (2022). Does ambidexterity consistency benefit small and medium-sized enterprises’ resilience? Journal of Small Business Management, 60(5), 1122–1165. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2021.2014508

- Ikhsan, K., Almahendra, R., & Budiarto, T. (2017). Contextual ambidexterity in SMEs in Indonesia: A study on how it mediates organizational culture and firm performance and how market dynamism influences its role on firm performance. International Journal of Business and Society, 181), 369–390.

- Indarti, N., & Postma, T. (2013). Effect of networks on product innovation: Empirical evidence from Indonesian SMEs. Journal of Innovation Management, 1(2), 140–158. https://doi.org/10.24840/2183-0606_001.002_0010

- Ioanid, A., Deselnicu, D. C., & Militaru, G. (2018). The impact of social networks on SMEs’ innovation potential. Procedia Manufacturing, 22, 936–941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2018.03.133

- Jacob, J., Mei, M. -Q., Gunawan, T., & Duysters, G. (2022). Ambidexterity and innovation in cluster SMEs: Evidence from Indonesian manufacturing. Industry and Innovation, 29(8), 948–968. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2022.2072712

- Jaidi, N., Siswantoyo, Liu, J., Sholikhah, Z., & Andhini, M. M. (2022). Ambidexterity behavior of creative SMEs for disruptive flows of innovation: A comparative Study of Indonesia and Taiwan. Journal of Open Innovation, Technology, Market, and Complexity, 8(3), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8030141

- Jansen, J. J. P., Simsek, Z., & Cao, Q. (2012). Ambidexterity and performance in multiunit contexts: Cross-level moderating effects of structural and resource attributes. Strategic Management Journal, 33(11), 1286–1303. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.1977

- Jansen, J. J. P., Van Den Bosch, F. A. J., & Volberda, H. W. (2006). Exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, and performance: Effects of organizational antecedents and environmental moderators. Management Science, 52(11), 1661–1674. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1060.0576

- Kahn, K. B., & Candi, M. (2021). Investigating the relationship between innovation strategy and performance. Journal of Business Research, 132, 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.009

- Kamboj, S., Kumar, V., & Rahman, Z. (2017). Social media usage and firm performance: The mediating role of social capital. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 7(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-017-0468-8

- Kapucu, N., & Hu, Q. (2014). Understanding multiplexity of collaborative emergency management networks. The American Review of Public Administration, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074014555645

- Kauppila, O. P. (2010). Creating ambidexterity by integrating and balancing structurally separate interorganizational partnerships. Strategic Organization, 8(4), 283–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127010387409

- Kenis, P., & Knoke, D. (2002). How organizational field networks shape interorganizational tie-formation rates. Academy of Management Review, 27(2), 275. https://doi.org/10.2307/4134355

- Knight, E., & Harvey, W. (2015). Managing exploration and exploitation paradoxes in creative organisations. Management Decision, 53(4), 809–827. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-03-2014-0124

- Kuckertz, A., Br€andle, L., Gaudig, A., Hinderer, S., Arturo Morales Reyes, C., Prochotta, A., Steinbrink, K. M., & Berger, E. S. C. (2020). Startups in times of crisis – a rapid response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 13, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2020.e00169

- Kuratko, D. F., & Hoskinson, S. (Eds.). (2018). The challenges of corporate entrepreneurship in the disruptive age (Vol. 28). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1048-4736201828

- Lavie, D. (2006). The competitive advantage of interconnected firms: An extension of the resource-based view. Academy of Management Review, 31(3), 638–658. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.21318922

- Lavie, D., Kang, J., & Rosenkopf, L. (2011). Balance within and across domains: the performance implications of exploration and exploitation in alliances. Organization Science, 22(6), 1517–1538. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0596

- Lavie, D., & Rosenkopf, L. (2006). Balancing exploration and exploitation in alliance formation. Academy of Management Journal, 49(4), 797–818. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.22083085

- Lazer, D., & Friedman, A. (2007). The network structure of exploration and exploitation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(4), 667–694. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.059

- Lee, I. H., & Lévesque, M. (2023). Do resource-constrained early-stage firms balance their internal resources across business activities? If so, should they? Journal of Business Research, 159, 113410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.113410

- Levinthal, D., & March, J. G. (1993). The Myopia of learning. Strategic Management Journal, 14(Winter Special Issue), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250141009

- Lin, H. -E., & McDonough, E. F., III. (2014). Cognitive frames, learning mechanisms, and innovation ambidexterity. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 31(S1), 170–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12199

- Lin, H. -E., McDonough, E. F., Lin, S. -J., & Lin, C. -Y. -Y. (2012). Managing the exploitation/exploration paradox: The role of a learning capability and innovation ambidexterity: Managing the exploitation/exploration paradox. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30(2), 262–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5885.2012.00998.x

- Liu, W., Sidhu, A., Beacom, A. M., & Valente, T. W. (2017). Social Network Theory. In P. Rössler, C. A. Hoffner, & L. van Zoonen (Eds.), The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects (pp. 1–12). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118783764.wbieme0092

- Lubatkin, M. H., Simsek, Z., Ling, Y., & Veiga, J. F. (2006). Ambidexterity and performance in small-to medium-sized firms: the pivotal role of top management team behavioral integration. Journal of Management, 32(5), 646–672. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206306290712

- Lu, Y., Wu, J., Peng, J., & Lu, L. (2020). The perceived impact of the Covid-19 epidemic: Evidence from a sample of 4807 SMEs in Sichuan Province, China. Environmental Hazards, 19(4), 323–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/17477891.2020.1763902

- Majid, A., Yousaf, M., Yasir, Z., & Yousaf, Z. (2020). Network capability and strategic performance in SMEs: The role of strategic flexibility and organizational ambidexterity. Eurasian Business Review, 11(4), 24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-020-00165-7

- March, J. G. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2(1), 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2.1.71

- McEvily, B., & Zaheer, A. (1999). Bridging ties: A source of firm heterogeneity in competitive capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 20(12), 1133–1156. https://doi.org/10.1002/SICI1097-026619991220:12<1133:AID-SMJ74>3.0.CO;2-7

- Molina-Morales, F. X., & Martínez-Fernández, M. T. (2010). Social Networks: Effects of Social Capital on Firm Innovation. Journal of Small Business Management, 48(2), 258–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2010.00294.x

- Ngammoh, N., Mumi, A., Popaitoon, S., & Issarapaibool, A. (2023). Enabling social media as a strategic capability for SMEs through organizational ambidexterity. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 35(2), 197–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2021.1980682

- Nofiani, D., Indarti, N., Lukito-Budi, A. S., & Manik, H. F. G. G. (2021). The dynamics between balanced and combined ambidextrous strategies: A paradoxical affair about the effect of entrepreneurial orientation on SMEs’ performance. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 13(5), 1262–1286. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-09-2020-0331

- O’reilly, C. A., & Tushman, M. L. (2008). Ambidexterity as a dynamic capability: Resolving the innovator’s dilemma. Research in Organizational Behavior, 28, 185–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2008.06.002

- O’reilly, C. A., & Tushman, M. L. (2013). Organizational Ambidexterity: Past, present, and future. Academy of Management Perspectives, 27(4), 324–338. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2013.0025

- Papadopoulos, T., Baltas, K. N., & Balta, M. E. (2020). The use of digital technologies by small and medium enterprises during COVID-19: Implications for theory and practice. International Journal of Information Management, 55, 102192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102192

- Parida, V., Patel, P. C., Wincent, J., & Kohtamaki, M. (2015). Network Partner Diversity, Network Capability, and Sales Growth in Small Firms. Journal of Business Research, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.017

- Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. R. (2003). The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. Stanford University Press.

- Posen, H. E., & Levinthal, D. (2012). Chasing a Moving Target: Exploitation and Exploration in Dynamic Environments. Management Science, 58(3), 587–601. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1110.1420

- Priyanka, Jain, M., & Dhir, S. (2022). Antecedents of organization ambidexterity: A comparative study of public and private sector organizations. Technology in Society, 70, 102046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2022.102046

- Raisch, S., & Birkinshaw, J. (2008). Organizational Ambidexterity: Antecedents, Outcomes, and Moderators. Journal of Management, 34(3), 375–409. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308316058

- Raisch, S., Birkinshaw, J., Probst, G., & Tushman, M. L. (2009). Organizational Ambidexterity: Balancing Exploitation and Exploration for Sustained Performance. Organization Science, 20(4), 685–695. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0428

- Randall, C., Edelman, L., & Galliers, R. (2017). Ambidexterity Lost? Compromising Innovation and the Exploration/Exploitation Plan. Journal of High Technology Management Research, 28(1), 1047–8310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hitech.2017.04.001

- Rintala, O., Laari, S., Solakivi, T., Töyli, J., Nikulainen, R., & Ojala, L. (2022). Revisiting the relationship between environmental and financial performance: The moderating role of ambidexterity in logistics. International Journal of Production Economics, 248, 108479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2022.108479

- Rodan, S., & Galunic, C. (2004). More Than Network Structure: How Knowledge Heterogeneity Influences Managerial Performance and Innovativeness. Strategic Management Journal, 25(6), 541–562. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.398

- Rogan, M., & Mors, M. L. (2015). A Network Perspective on Individual-Level Ambidexterity in Organizations. Organization Science, 25(6), 1860–1877. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2014.0901

- Ross, W., & Robertson, D. (2007). Compound Relationships Between Firms. Journal of Marketing, 71(3), 108–123. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.71.3.108

- Rothaermel, F. T., & Deeds, D. L. (2004). Exploration and exploitation alliances in biotechnology: A system of new product development. Strategic Management Journal, 25(3), 201–221. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.376

- Rowley, T., Behrens, D., & Krackhardt, D. (2000). Redundant Governance Structures: An Analysis of Structural and Relational Embeddedness in the Steel and Semiconductor Industries. Strategic Management Journal, 21, 369–386. https://doi.org/10.1002/SICI1097-026620000321:3<369:AID-SMJ93>3.0.CO;2-M

- Russo, A., & Vurro, C. (2010). Cross-Boundary Ambidexterity: Balancing Exploration and Exploitation in the Fuel Cell Industry. European Management Review, 7(1), 30–45. https://doi.org/10.1057/emr.2010.2

- Sahi, G. K., Gupta, M. C., & Cheng, T. C. E. (2020). The effects of strategic orientation on operational ambidexterity: A study of Indian SMEs in the industry 4.0 era. International Journal of Production Economics, 220, 107395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2019.05.014

- Saratchandra, M., Shrestha, A., & Murray, P. A. (2022). Building knowledge ambidexterity using cloud computing: Longitudinal case studies of SMEs experiences. International Journal of Information Management, 67, 102551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2022.102551