?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study investigates the mediating effect of strategic management accounting (SMA) practices on the relationship between intellectual capital (IC) and investment efficiency (IE). Using secondary data and primary data through the questionnaire survey from 127 Vietnamese listed companies, this work applies the PLS-SEM approach to examine the mediating role of SMA practices in the relationship between IC and IE. The empirical results show a direct connection between structural capital (a measurement of IC) and IE because firms will likely use structural capital representing a well-organized structure to facilitate efficient capital allocation. Moreover, the research findings also indicate a direct correlation between IC components and SMA practices. Regarding the mediating role of SMA in the relationship between IC and IE, SMA fully or partially mediates the positive influence of IC components over the performance of IE. This research contributes to existing resources management literature on the Resources (i.e. IC) – Practices (i.e. SMA practices) – Productivity (i.e. IE) connectedness. Thereby, it provides undiscovered empirical evidence of the role of employees (human capital (HC)) and well-organized structure (structural capital (SC)) such as procedures or processes to facilitate the efficient allocation of capital.

1. Introduction

This study aims to investigate the association between IC and IE, along with the mediating role of SMA practice in the relationship mentioned above. The authors intend to use the data of Vietnamese listed companies to answer three main research questions: (1) Does the level of IC directly influence the firm’s IE?; (2) Is there a direct relationship between the magnitude of IC and SMA practices in the Vietnamese context?; (3) What kinds of mediation that SMA practices play in the association between IC and IE?

Organizations in today’s knowledge-based economy do not only initially devote themselves to physical assets but to intangibles, as these are today’s value drivers (Mehralian et al., Citation2013). Amongst intangible assets, IC plays a key role owing to these being strategic assets to enhance sustainable competitive advantages (Riahi-Belkaoui, Citation2003), the foremost determinant of company success (Alum & Drucker, Citation1986). From a managerial perspective, SMA is a form of management accounting which emphasizes information related to key strategic decisions (CIMA, Citation2014). Simultaneously, following resource-based theory, IC is the asset used for strategic purposes. SMA would, therefore, theoretically appear to play a potential role in IC management.

The IC literature from the accounting perspective is diverse though it primarily addresses external reporting or the measurement of IC components. Research in the accounting area related to IC indicates several correlations between IC and various firm outcome factors, such as firm performance (Ahangar, Citation2011; Kengatharan, Citation2019), organization’s productivity (Alhassan & Asare, Citation2016; D. T. Nguyen et al., Citation2023; T. D. Q. Le et al., Citation2020), and bankruptcy (Cenciarelli et al., Citation2018). Meanwhile, one of the most significant current discussions in IC literature is about the relationship between the components of IC and corporate performance. Besides common proxies to measure corporate performance used by prior studies, such as ROA, ROE, ROS, etc. (Khuong & Anh, Citation2022b; Khuong, Anh, et al., Citation2022; H. T. Nguyen et al., Citation2022; Thuy, Khuong, Anh, et al., Citation2022), another indicator also has attracted a great deal of attention that is IE (Tan et al., Citation2018). Firms spend efficiently in ideal financial markets if they carry out all projects with positive net present value (NPV) and reject those with negative NPV. However, an earlier study (Bertrand & Mullainathan, Citation2003) refutes this notion, as the world is not without friction. As a result, market inefficiencies, information asymmetries, and agency conflicts may lead to approving projects with negative NPV (overinvestment) and rejecting initiatives with positive NPV (underinvestment). Following previous work of Biddle et al. (Citation2009), H. Chen et al. (Citation2011) and Cheng et al. (Citation2013), IE is defined as the expected level of investment, which is quantified as forecasted investment level based on sales growth potential. A positive departure from the intended level (i.e. investment more than expected level) is termed overinvestment, whereas a negative divergence from the desired level (i.e. investment less than anticipated level) is considered underinvestment. In contrast, both (overinvestment and underinvestment) are inefficient investments (Majeed et al., Citation2018). While research about IC is a growing field, publications on the relationship between IC and IE seem missing to date. Therefore, this research gap motivates the authors to investigate the direct relationship between IC and IE in the research context of Vietnam.

In addition to studies on IC and IE, academia and businesses have paid great attention to SMA practices throughout the past decade (Abdullah et al., Citation2022). SMA is the process of supplying and analysing management accounting data regarding a company’s product on the market, its cost structure, and its rivals’ expenses, as well as monitoring the firm’s and its competitors’ strategic market positions over time. SMA techniques can offer several benefits to firms. These techniques include competition and customer accounting, strategic pricing, strategic planning, control and performance management, and strategic decision-making. The authors of a recent review study on SMA Abdullah et al. (Citation2022) document that, despite the enormous potential of SMA for decision-making, there are still implementation issues and a lack of knowledge regarding the strategic use of SMA to achieve corporate objectives.

Adopting SMA practices in organizations can be viewed from various perspectives, including country, type of business, and the most critical techniques used. According to previous research, SMA practices include strategies that enable an organization to have an effective management team capable of making strategic choices (Cadez & Guilding, Citation2008, 2012; Cinquini & Tenucci, Citation2010). Numerous studies on the practice of SMA have been conducted (Abdullah et al., Citation2022; Cadez & Guilding, Citation2012; Guilding et al., Citation2000; Ojra et al., Citation2021; Phornlaphatrachakorn, Citation2019; R. A. Pires & Alves, Citation2011; R. A. R. Pires et al., Citation2019; Tillmann & Goddard, Citation2008; Tomkins & Carr, Citation1996). Regarding the antecedents that can influence the use and the extent of investment into SMA, most related research indicates that the usage of SMA practice is impacted by various factors, such as corporate governance, CEO characteristics, external environment and network (Abdullah et al., Citation2022; Doktoralina & Apollo, Citation2019; Ojra et al., Citation2021; Phornlaphatrachakorn, Citation2019; R. A. Pires & Alves, Citation2011; R. A. R. Pires et al., Citation2019). Results from earlier studies demonstrate a vital and consistent role of SMA practices in helping firms develop their strategies (Abdullah et al., Citation2022). Besides, prior studies have discussed the benefits deriving from SMA practices, and most of these studies support the argument that SMA practices are positively related to a firm’s performance (Kengatharan, Citation2019; Ojra et al., Citation2021; Phornlaphatrachakorn, Citation2019). However, although there are many reports in the literature on the factors that can impact SMA practices and the outcome of SMA practice, most are restricted to the context of developed countries. In recent years, there has been a slight increase in the number of studies about SMA in developing countries such as Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia (Amanollah Nejad Kalkhouran et al., Citation2017; Doktoralina & Apollo, Citation2019; Phornlaphatrachakorn, Citation2019); however, these existing studies have the same limitation in terms of the research sample. The sample of these studies lacks diversity in terms of industry; for instance, Doktoralina and Apollo (Citation2019) explore the relationship between SMA practice and firm outcome by utilizing a sample of 220 logistics companies in Malaysia. Similarly, Amanollah Nejad Kalkhouran et al. (Citation2017) explore the indirect impact of SMA in the association between CEO characteristics and company value through the sample of 121 service small and medium-sized enterprises. Conducting the study in the context of Thailand, Phornlaphatrachakorn (Citation2019) restricted the study’s sample to 194 information and communication technology businesses. As a result, the authors conduct this study to fulfil this research gap and contribute to the existing literature about SMA practices in developing countries.

While most of the models follow the indirect path between strategy and performance through the mediator of management practices (Prajogo & Sohal, Citation2006; Spencer et al., Citation2009; Teeratansirikool et al., Citation2013), a few studies have systematically examined the mediating function of management practices in fostering the correlation between resources and productivity. Therefore, little is known about the differences in the effects of IC (resources) on IE (productivity) via the mediating role of SMA practices (management practices). In this study, the authors argue that SMA can mediate the relationship between IC and IE for the following reasons. Firstly, organizations with solid levels of IC will have the assets as the necessary concrete to develop an SMA system to support the organizational efforts in identifying, measuring, and communicating the value drivers (Tayles et al., Citation2007). This suggests that organizations with a strong level of IC should have evolved management accounting with strategic directions. Secondly, once the traditional management accounting system has become more strategic, it will address the issues accounting for IC promotes, enhancing IE. Better SMA practices may improve IE by allowing managers to make better investment decisions by identifying optimal projects and more truthful accounting numbers for internal decision-makers.

From the discussion above, the current paper seeks to contribute to the existing literature. First, this is the first study conducted to explore the relationship between IC and IE in the Vietnamese context. Vietnam has unique attributes that differ from the countries in studies (Amanollah Nejad Kalkhouran et al., Citation2017; Doktoralina & Apollo, Citation2019; Phornlaphatrachakorn, Citation2019). Vietnam is a developing country with a socialist-oriented market economy; despite having a concentrated ownership environment, the Vietnamese economy is also under the regulation of the Government, and state-owned firms play an essential role in the economy (Khuong, Anh, et al., Citation2022, Citation2022). Besides, in 2022, Vietnam commences the phase of voluntary IFRS application in 2025, which means that Vietnam is still in the progress of IFRS adoption and convergence. In other words, the lack of strict regulation in protecting investors and the delays in adopting IFRS can increase the asymmetric information issue and reduce the transparency of the stock market (Khuong, Abdul Rahman, et al., Citation2022; Khuong, Anh, et al., Citation2022; L. H. T. Anh & Khuong, Citation2022). According to the agency theory, an inefficient investment may result from the moral hazard and adverse selection attributed to agency conflicts which emerge due to information asymmetry (Ullah et al., Citation2021). Therefore, this study can significantly contribute to the existing literature on IE by exploring how IC influences IE and whether IC can alleviate information asymmetry problems to help firms efficiently invest. Second, this is also the first study that thoroughly documents the mediating role of SMA practices on the IC-IE relationship. This study fulfils the research gap when little is known about the differences in the effects of IC (resources) on IE (productivity) via the mediating role of SMA practices (management practices). While most extant literature on SMA is restricted to developed countries, this study could answer the question of to what extent SMA practices are adopted in developing countries. In addition, understanding the role of SMA practices in the association between IC and IE also provides valuable recommendations for firms to develop appropriate SMA and allocate their limited resources effectively.

The remaining of this study is presented as the following. While section 2 describes the context of Vietnam, the theoretical framework of this study is presented in section 3. Then, section 4 review related studies and develop hypotheses. The research methodology and empirical results are described in section 5 and section 6, respectively. Finally, section 7 provides the author’s conclusion and suggests some implications from the research findings.

2. Research background

Vietnam is unique among the developing Asian nations in several ways. Corporate governance in Vietnamese publicly traded companies is poorly established. Vietnam’s investor protection and disclosure, and transparency rules are deficient. In fact, Vietnam has the lowest corporate governance score (50.9%) of all Asian nations, including Indonesia (60%), Malaysia (77.3%), and Thailand (72.7%). Just 11 of the 21 components of corporate governance standards examined by the World Bank were observed in Vietnam, indicating that while the legal and regulatory framework corresponds with OECD norms, their implementation and enforcement may differ in this country. In 2012, for instance, the corporate governance law was revised, and a transparency provision was introduced. In addition, a revised Vietnamese Enterprise Law was enacted in 2014, entered into effect in July 2015, and aims to preserve the autonomy of the board of directors. All of these laws and changes may contribute to the elimination of conflicts of interest, the improvement of accountability, and Vietnam’s success in its pursuit of high levels of transparency and sustainable commercial growth. Yet, governance problems continue and are exacerbated by inadequate processes of openness and accountability. No matter how much the corporate governance code is improved, it will continue to be challenging to modify laws and regulations to catch up with reality rapidly.

In Vietnam, however, the State Securities Commission and the two stock exchange channels—the Ho Chi Minh City Stock Exchange and the Hanoi Stock Exchange—collaboratively develop the corporate governance code. This indicates that there is substantial regulatory pressure to implement the code. Moreover, Vietnam has become a battlefield for corporate governance models as many international corporations have relocated sections of their operations there. In essence, there are loopholes in the legislative standards for openness, and monitoring agencies lack independence. Vietnam has the most work to do to achieve the corporate governance principles that were initially issued in 2007 based on the OECD Principles of Corporate Governance 2004: the Vietnamese Businesses Law (2014) and the Vietnamese Securities Law (2010).

State and foreign ownership are among the components of corporate governance in Vietnam that the writers will introduce. Regarding the amount of State Ownership, the circumstance is also quite unique. The move to a socialist-oriented market economy in Vietnam was termed equitization’ rather than privatization’ since State-owned businesses (SOEs) were still required to preserve the State’s assets in order to achieve government goals. This equitization has undergone substantial changes in terms of quantity: the number of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) has reduced dramatically from over 12,000 in 1991 to over 500 in 2017. However, the equitization of SOEs is incomplete due to the fact that the Vietnamese government still holds a large percentage (above 50%) of ownership in the listed SOEs of strategic industries or key sectors, such as electricity production, telecommunications, mineral exploration, oil, gas, and water supply. Thus, the State is the controlling shareholder in a substantial number of Vietnamese businesses. The government retains a majority stake in them and continues to implement strategic and policy actions. Due to the absence of a framework enabling cooperation amongst state authorities in exercising ownership rights, the State’s oversight over enterprise managers is irregular and ineffective. Consequently, financial information can be easily manipulated by management, and traders who are well-informed have reduced information costs and can use advance information to their advantage. Thus, they encounter several conflicts of interest when regulating and enforcing laws.

Foreign investor participation has increased significantly during the Vietnamese equitization process. In the mid-2000s, Vietnam’s first stock market, the Ho Chi Minh Stock Exchange (HSX), was founded in Ho Chi Minh City. The Hanoi Stock Exchange (HNX), a second stock market, was founded in Hanoi’s northern sector in 2005. Both the HSX and the HNX have over 800 businesses listed at the end of 2017. Additionally, Vietnam has become one of the Asian countries with the fastest economic growth rates. For all of these reasons, Vietnam has emerged as an appealing investment destination with several chances and prospects, as well as the country with the greatest foreign direct investment. However, the government also adopted regulations to control and monitor foreign investor participation in No 60/2015/N-CP and No 58/2012/N-CP. The allowable percentage of foreign ownership in listed Vietnamese enterprises, according to these laws, varies by industry or sector, ranging from a maximum of 49% for non-financial firms to 30% for finance and allied firms. Furthermore, there is a conflict between article 10 of the law on foreign investment, which states that foreign owners will bear all risks and losses as a percentage of their capital share, and article 11 of the decree 24/2000/ND-CP, which states that “each joint-venture party shall bear liability within the limit of its capital contributed to the legal capital of its enterprise.” As a result, foreign investors’ rights are not explicitly and effectively enforced in practice, and owners are not treated equitably in joint ventures.

Aiming to generate significant interest from foreign investors for earlier SOEs’ divestments in 2020, when more than 400 SOEs still exist, Vietnam has attempted to produce stock market transparency despite efforts to monitor and protect shareholders in the Vietnamese market through market regulations, the legal framework, and corporate governance. Market laws, the legal system, and corporate governance are all used to oversee and protect shareholders in the Vietnamese market.

From the characteristics of the corporate governance mechanisms and the types of common ownership structures in Vietnam mentioned above, the authors will help to understand the impact of corporate governance mechanisms on the firm outcome, IE. In particular, the mediating role of internal governance mechanisms like SMA to the relationship between IC (can also be considered an internal mechanism through) and IE in the context of Vietnam. From this perspective, this study will fill the research gap related to SMA and IC literature when investigating the relationship between IC and IE and the mediating role of SMA practice through a unique research context like Vietnam.

3. Theoretical framework

3.1. Definition of intellectual capital

The IC idea was first mentioned in a significant body of writing and has grown in three stages. The first stage started in the 1990s and helped people understand why IC was critical, its advantages, and how to define it (Mehralian et al., Citation2013). The second phase, which began in 2000, will look at measurement, modelling, international case studies, and other levels of analysis (Mehralian et al., Citation2013). So, a lot of research in many countries backs up the link between IC and corporate performance. This research uses a variety of research methods. The third stage of IC research, which started in 2004, is trying to figure out how to put IC on products and services so that customers and other stakeholders can see it (J. Dumay et al., Citation2013). There is a lack of consensus on the IC definition; however, most prior authors appear consistent in that IC is a multi-dimensional concept, including knowledge capital that can create competitive advantage or business values. IC is a source of intangible assets often not presented on the statement of financial position. As for the IC components, there is broad unanimity about the presence of three core interrelated non-financial factors, HC, SC and RC (Edvinsson & Sullivan, Citation1996). Moreover, this study characterizes SC as incorporating innovation and organizational means, following the investigations of (Campbell & Abdul Rahman, Citation2010; Nazari et al., Citation2007).

According to McGregor et al. (Citation2004), HC is a broader term than human resource because it includes operating capital that is in the minds of employees but not owned by the organization (Bontis & Fitz-Enz, Citation2002; Vithana et al., Citation2019), such as “knowledge, skills, attitude, and intellectual agility.” (Edvinsson & Sullivan, Citation1996). SC is the most complicated since it comprises many kinds of capital. Even while HC is a part of the management structure and affects SC, SC is not the same as HC. For example, the organization owns patents that were made by HC. This study changes Bontis (Citation2001)’s definition and Campbell and Abdul Rahman (Citation2010)’s definition such that their meanings do not overlap. So, the aspects of SC in this research include innovation and architectural features, such as organizational culture, process, creativity, and management philosophy. RC is a good phrase for an organization’s relationships with consumers, networks with suppliers, distributors, advocacy groups, and other outside stakeholders. RC improves human and SC to encourage wealth innovation (Bontis & Fitz-Enz, Citation2002; Helm Stevens, Citation2011; Levy, Citation2009; Mouritsen et al., Citation2004).

3.2. Determinants of strategic management accounting practices

Several additional scholars conducted and defined the SMA idea in the 1990s, including (Bromwich, Citation1990; Dixon & Smith, Citation1993; Foster & Gupta, Citation1994; Guilding et al., Citation2000; Ward, Citation1992). While their definitions and descriptions of SMA differ significantly, three common aspects of SMA may be gleaned from their research:

- A greater emphasis on the outside world.

- A long-term perspective and a forward-thinking attitude.

- A method of generating financial and non-financial data for strategic decision-making.

Guilding et al. (Citation2000) advocated the first original work of SMA techniques. The 12 SMA approaches were identified in this study. Cravens and Guilding (Citation2001) presented three more strategies in subsequent research, totaling 15 techniques: activity-based costing, integrated performance assessment, and benchmarking. The third research on the customer accounting viewpoint by Guilding and McManus (Citation2002) incorporated three new SMA approaches connected to customers: profitability analysis, lifetime customer analysis, and customer group value. Table shows how 18 strategies classified as SMA practice have been classified into four groups. According to Cravens and Guilding (Citation2001), the three key underlying aspects of SMA practices are as follows. These include “strategic cost management” (6 approaches), “competitor accounting” (5 techniques), and “strategic accounting” (4 courses). In addition to Cravens and Guilding (Citation2001) research, this study covers three customer-focused methodologies that may be referred to as the fourth dimension, “customer accounting,” based on Guilding and McManus (Citation2002).

Table 1. The techniques of SMA practices

3.3. Definition of investment efficiency

Many academics have claimed that if the market is efficient, investors will place a higher value on enterprises with higher IE (F. Chen et al., Citation2011; Ming-Chin et al., Citation2005). The corporation should invest until the marginal benefit equals the marginal cost of financing to maximize shareholder value. However, due to information asymmetry between management and shareholders, the management may deviate from their optimal investment levels, resulting in underinvestment (less investment than expected) or overinvestment (more investment than expected) (Cutillas Gomariz & Sánchez Ballesta, Citation2014). In other words, in ideal financial markets, all positive net present value initiatives should be funded and implemented to increase company value. Nonetheless, market inefficiencies, information asymmetries, and agency costs may result in the execution of harmful net present value initiatives (overinvestment) and the rejection of positive net current value projects (underinvestment) (Healy & Palepu, Citation2001; Hubbard, Citation1997). According to agency theory, the availability of asymmetric knowledge among stakeholders can explain both overinvestment and underinvestment. As a result, IE is regarded as an indicator for assessing productivity performance in internal management operations.

3.4. Resource-based theory

According to resource-based theory, intangible resources are essential for firm performance (Barney, Citation1991). The core argument is that using tangible and intangible assets should give modern organizations a competitive advantage. In other words, the firm’s resource-based view contends that differences in profitability across companies may be explained by differences in their resource portfolio and how these resources are expressed (Wernerfelt, Citation1984). According to Barney (Citation1991), the resource-based approach acknowledges intangible assets as essential variables in building the long-term competitive advantage required for outstanding corporate performance. Global markets have seen an industrial change from capital-intensive to knowledge-based. Traditional performance metrics, which focus almost entirely on the financial elements of businesses, fail to assess and monitor different dimensions of performance (Amaratunga et al., Citation2001). As a result, new approaches for measuring the value of intangibles and their influence on company performance are required. From these discussion about resource-based theory, following previous studies, Nadeem et al. (Citation2017, Citation2018), Rehman et al. (Citation2022), Ullah et al. (Citation2021), and Yahya and Ibrahim (Citation2021), this research applies resource-based theory to investigate the relationship between IC and IE along with the mediating role of SMA practice.

4. Empirical literature review and hypotheses development

4.1. Research trends on intellectual capital in the accounting discipline

IC is investigated from four perspectives: economic, strategic, managerial, and accounting (Alcaniz et al., Citation2019). For instance, from a financial standpoint, IC is tied to the success of nations with advanced technology, educated labour forces, etc (Stewart & Ruckdeschel, Citation1998). From a strategic standpoint, achieving a company’s goal is no longer crucially dependent on its tangible resources but on its intangibles. The build-up of IC is also designed as a result of a two-way relationship between resources and the system (Brooking, Citation1996). Physical, financial, and IC combine to shape an organization’s help from the management standpoint. As such, they must be adequately recognized and maintained as the value foundations of an organization (Bontis, Citation1999). However, this research focuses on many perspectives on accounting for IC-related issues. As demonstrated in J. Dumay et al. (Citation2013)’s work analysing 423 journal articles about IC from 2000 to 2009, the primary focus of IC accounting research in the accounting discipline is management control, performance assessment, and external reporting. Still, literature on accountability, governance, and auditing is lacking. In a contemporary study, Troise et al. (Citation2022) analyse the function of signalling performed by the IC of entrepreneurial enterprises towards crowd funders in the Italian research setting. The success of equity crowdfunding campaigns may be attributed to the beneficial impact of RC on the investment decisions of equity crowd funders. HC and SC positively affect investment decisions to a limited extent. In addition, Kweh et al. (Citation2021) utilized a sample of 24 Taiwanese banks to indicate a substantial positive relationship between IC and banks’ overall resource usage and IE.

The relationship between IC and business performance, in particular, has been extensively researched. Numerous studies conducted in several countries and using diverse research approaches confirm this association. In general, these studies find a positive relationship between IC (or some of its components) and corporate success, while the exact nature of this relationship varies. The majority of studies that have used Pulic (Citation2000) Value Added Intellectual Coefficient model (VAIC) as a measure of IC components have resulted from a combination of outcomes from various nations, industries, and years. Ming-Chin et al. (Citation2005), for example, discover that IC drives corporate value and financial performance. According to Shiu (Citation2006), the relationship between VAIC and performance is only weak. Furthermore, Clarke et al. (Citation2011) demonstrated that SC efficiency rarely has a substantial correlation with performance. A slew of contradictory research does not support a strong conclusion about the relationship between IC and company performance. The majority of the world’s IC research is conducted in Western countries. Many countries have conducted empirical studies on IC, including but not limited to North America (Bontis, Citation1998; Riahi-Belkaoui, Citation2003), Germany (Bollen et al., Citation2005), South Africa (Firer & Mitchell-Williams, Citation2003), Australia (J. C. Dumay, Citation2009), Bangladesh, China (Saengchan, Citation2008).

Even though international interdisciplinary accounting research conferences provided many opportunities for IC accounting researchers in the 2010s and beyond, overseas researchers conducted the majority of papers presented at international conferences held in Vietnam in the context of foreign countries. Nonetheless, empirical cross-sectional studies on the performance implications of intangible investments or IC in Vietnam are scarce owing to two significant challenges. For starters, intangible assets are frequently undervalued in Vietnamese businesses. The majority of this category’s expenditures are expensed rather than capitalized. The disclosure of these expenses is also woefully inadequate. Second, because Vietnamese managers have not recognized the crucial role of IC in their management processes, a business climate no longer concerned with IC may not stimulate the wave of IC research in Vietnam. As proof, some studies in Vietnam have been done to study the influence of IC on the profitability of organizations (D. T. Nguyen et al., Citation2023; T. D. Q. Le et al., Citation2020). However, this research is limited to the financial business, and financial enterprises have distinct features from service or manufacturing firms. As a result, more research is needed to study the relationship between IC and IE in the Vietnamese setting using a sample of non-financial firms.

4.2. Related literature about strategic management accounting

The SMA study remains focused on four themes: (1) how to define the idea of SMA, (2) what types of SMA approaches are used in various industries and nations, (3) the effects of strategy options on SMA changes, and (4) the SMA process. Most of the empirical research published in the previous 30 years has consisted of questionnaire surveys to determine the extent to which specific SMA strategies have been adopted (Langfield-Smith & Parker, Citation2008).

Prior research on SMA, such as Tomkins and Carr (Citation1996), examined data from 44 German and UK organizations and discovered that management styles and cultures substantially influenced the choice of strategic investment techniques such as strategic costing methodologies. Meanwhile, a study by Al-Mawali (Citation2015) focused on dependent variables on SMA practices in Jordanian firms. It revealed that perceived environmental unpredictability and market orientation substantially affected the amount of SMA technique utilization. Cuganesan et al. (Citation2012) conducted a long-term study of public-sector organizations in Australia. They discovered that SMA practices appear to play a function in creating strategy and identifying particular ways management accounting is significant in strategizing through distinct organizational practices.

According to an archival study Arunruangsirilert and Chonglerttham (Citation2017), corporate governance features substantially impact SMA involvement and utilization. Thus, this study, which used secondary data from Thai firms registered on the Thai Stock Exchange, discovered that an independent chairman and board size hurt both participation and use of SMA procedures. Turner et al. (Citation2017) argued that following SMA techniques will improve the competitiveness and performance of hotel properties by designing and executing internal rules and procedures. Thus, SMA practices represent their business strategy’s stability, evolving competitive needs, and profitability.

Amanollah Nejad Kalkhouran et al. (Citation2017) studied the impact of CEO qualities and network participation on SMA practices. The information was gathered from 121 Malaysian service SMEs. According to the research, CEO education and network engagement significantly influence SMA usage, which in turn reflects on the firm’s success. Thus, previous and new research indicates that various factors, including corporate governance, management, the CEO, the external environment, and networking, may impact SMA practices. These studies also demonstrated the significance of SMA practices in creating strategies. However, empirical research that links SMA practices and organizational skills is needed.

Many studies have used contingency theory to investigate the link between strategy, SMA practices, and organizational performance. In other words, previous research has concentrated on the acceptance and advantages of SMA approaches. The work of Chenhall and Langfield-Smith (Citation1998) in the study focus on Australian organizations served as the starting point for empirical research on the association between SMA practices and performance. Chenhall and Langfield-Smith (Citation1998) revealed that various SMA practices and routines have good relationships under different strategic orientations. Similarly, Al-Mawali and Al-Shammari (Citation2013) discovered that the amount of SMA usage favourably improves organizational performance in 296 Jordan enterprises, with perceived environmental uncertainty as a mediator (Al-Mawali & Al-Shammari, Citation2013). In general, the correlation between SMA practices and corporate performance has been conducted in a range of countries, such as Australia (Chenhall & Langfield-Smith, Citation1998), the UK (Ma & Tayles, Citation2009), Malaysian (Hassan et al., Citation2011), Croatia (Ramljak & Rogošić, Citation2012), Slovenian (Cadez & Guilding, Citation2012), Jordan (Al-Mawali & Al-Shammari, Citation2013) and the exact nature of this positive correlation is consistent in all of the studies. Many studies have been carried out in affluent nations. However, the number of similar studies in underdeveloped countries is relatively low. However, recent research has revealed a surge in SMA studies in emerging nations such as Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia (Abdullah et al., Citation2022; Amanollah Nejad Kalkhouran et al., Citation2017; Doktoralina & Apollo, Citation2019; Nik Abdullah, Citation2020; Phornlaphatrachakorn, Citation2019).

For example, Phornlaphatrachakorn (Citation2019) investigates how SMA impacts the profitability of Thai enterprises that manufacture or sell information and communication technology products. According to this report, 194 Thai enterprises employ information and communication technologies. According to the study’s findings, SMA approaches give information richness related to organizational excellence, goal attainment, and company profitability. Meanwhile, Nik Abdullah (Citation2020) claims that using SMA methodologies will create value in Malaysian GLCs by improving industry competitiveness, expanding financial position, and providing opportunities for profitability, company sustainability, and long-term performance. As a result, SMA is a significant source of both competitive advantage and high performance.

Despite the relevance of SMA, as underlined in several previous academic research, there is a lack of information on how SMA-inspired approaches and procedures are disseminated into an organization’s general practices (Kohli & Jaworski, Citation1990). The study evaluated previous empirical articles on SMA and found no strong evidence that SMA procedures have been widely implemented, even though components of SMA have affected corporate thinking and language. Meanwhile, according to a few polls on SMA practices, competitor accounting and strategic pricing are the most often employed strategies. At the same time, some argue that SMA is underutilized in businesses because its significance is not always evident to management (Cravens & Guilding, Citation2001; Guilding et al., Citation2000; Tomkins & Carr, Citation1996). Lord (Citation1996) proposed that SMA methods and traits may be found in many businesses, which is validated by research. Due to its multiple flaws and a highly suspicious perspective of SMA, the investigation determined that it is a “figment of academic imagination.” According to studies and other data, many firms have embraced SMA practices over time. This demonstrates that the strategies have been widely employed in businesses.

Economic transformation has been a fundamental driver of economic and commercial development in Vietnam. Vietnamese firms have steadily implemented modern accounting procedures by market mechanisms as they progressed in their integration with worldwide accounting. Management accounting in Vietnam has gone through several stages in the last decade since it was legally acknowledged in the Accounting Law 2003 and Circular 53/2006/TT-BTC, even though it first existed in the world a long time before. The early 1990s saw the start of research on the Vietnamese management accounting system. Overall, Vietnam’s economic, political, and social environments vastly differ from those of Western or Asian countries. Since Vietnam implemented an open-door policy, the degree of competition in the economy has increased dramatically for most Vietnamese firms, owing to the establishment of many privates, joint ventures, and foreign-owned enterprises in Vietnam during the previous two decades (D. N. P. Anh, Citation2010). As a result, international organizations introduce Vietnamese practitioners and researchers to a practical understanding of SMA. As a result, SMA has been explored in Vietnam since the 2010s; nevertheless, there has been little systematic recording and analysis of current initiatives to utilize SMA methods in Vietnamese firms. According to specific research in Vietnam, such as Loi (Citation2014); Que and Thien (Citation2014), small and medium-sized firms use traditional management accounting, whereas medium-to-large enterprises prioritize applying SMA to gather important information for decision-making. Although this is a joint study topic explored in many other countries, no empirical research has been discovered to evaluate the influence of SMA practices on the performance of Vietnamese firms.

4.3. Hypotheses development

Some studies examine that human, structural and relational reciprocally circulate and cooperate in generating synergy (Edvinsson & Sullivan, Citation1996; Hsu & Fang, Citation2009). Stewart and Ruckdeschel (Citation1998) also note that IC will be most effective only when these dimensions support each other. For example, employee abilities (HC) also impact a firm’s process efficiency (SC). High-quality employees (HC) will attract loyal customers and good business partners (RC) (Vithana et al., Citation2019). On the other hand, RC also positively affects SC (Hsu & Fang, Citation2009). For instance, a firm retaining a better affiliation with its stakeholders (RC) enables its employees to manage daily operations and business processes effectively (SC). All inspire this study to develop the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a:

Human capital positively impacts relational capital.

Hypothesis 1b:

Human capital positively impacts structural capital.

Hypothesis 1c:

Relational capital positively impacts structural capital.

The strategic positioning literature shows that HC is a driving force influencing the opted corporate-level strategy, which thereby impacts the design of management accounting (Ananthram et al., Citation2013; R. A. Pires & Alves, Citation2011; R. A. R. Pires et al., Citation2019). According to Widener (Citation2004)’s study, a firm with a lower reliance on HC (i.e. the strategy of HC is centered only on key employees) will design a management accounting system that will depend more on traditional, aggregate financial result controls. On the other hand, a firm with a higher reliance on HC (i.e., strategic HC is diffused throughout the organization) will rely more on non-traditional, non-financial result controls and leverage the staff’s contributions to strategic decision-making. Firms that rely more on HC will likely consider non-financial measures like staff loyalty, staff turnover, and competence development index as leading indicators that provide information to make strategic decisions. Another example is high HC firms will rely more on all the employees’ participation in budgeting that prefers more frequent forecasting and separate targeted settings. As a result, these firms change conventional budgeting over the approach of rolling budgeting of SMA practices (Ananthram et al., Citation2013; R. A. Pires & Alves, Citation2011; R. A. R. Pires et al., Citation2019). This leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2a:

Human capital is positively associated with the practices of SMA.

SC includes a firm’s overall process, organizational structure design, information system structure and even corporate culture. Corporate culture, one element of structural means, may also play a crucial role in changing and developing a firm’s accounting system (Hsu & Fang, Citation2009). For example, a firm with a role culture relies on formalized rules and procedures to guide decision-making (CIMA, Citation2014) and, thus, tends to be controlled at the center. Traditional management accounting practices, such as imposed budgeting, responsibility accounting, and financial result controls are deployed. By contrast, a firm with a task culture is more likely to employ non-financial measures, and participative budgeting, which encourages creativity and job satisfaction (CIMA, Citation2014). According to Cleary (Citation2015), firms with customer-focused and market-driven orientations want to develop efficient organizational routines and processes (including SMA) created by the input resources, i.e. IC, to cater to informational demands. For instance, focusing SC on establishing a customer databank will improve SMA practices in customer accounting to reduce the cost of decision-making due to resistance of insufficient information (R. A. Pires & Alves, Citation2011; R. A. R. Pires et al., Citation2019). Based on the discussion above, this paper offers the hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 2b:

Structural capital is positively associated with the practices of SMA.

Tsai (Citation2001) recognizes that employees with better communication skills and connections with externals have more opportunities to access different resources. This connectedness may enhance the practices of SMA to some degree. Better links allow business partners to share information and professional technology. Accordingly, RC may increase a firm’s capability of external information development. RC brings a more robust external focus—especially regarding the behaviour of competitors, customers, and suppliers (R. A. Pires & Alves, Citation2011; R. A. R. Pires et al., Citation2019). This information will be vital to allow the business to understand the market it is operating in, which is a fundamental input of SMA usage. Firms, therefore, understand and satisfy stakeholder needs to achieve innovation and economic success. Strategic management accountants use basic information from external relationships to produce data that will help the business in several ways, including effective strategic planning, business performance control, and better decision-making (R. A. Pires & Alves, Citation2011; R. A. R. Pires et al., Citation2019). Therefore, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2c:

Relational capital is positively associated with the practices of SMA.

The resource-based approach may be further examined to determine that organizational assets can be divided into three categories: tangible, intangible, and organizational capabilities (Bierly & Chakrabarti, Citation1996). Production facilities, raw materials, financial resources, real estate, and computers are substantial assets, whereas brand names and a company’s reputation are examples of intangible assets. But they frequently play a crucial role in forging a competitive edge (Grant, Citation1996). Organizational capabilities are the abilities and methods of integrating resources, people, and procedures that a business utilizes to turn inputs into outputs; they are not particular “inputs” like tangible or intangible assets (Galbreath & Galvin, Citation2004). As IC comprises two-thirds of a company’s assets and consists of organizational capabilities and intangible assets, it is assumed that IC is a strategic resource under the resource-based theory definition and capable of creating value when correctly managed (Grant, Citation1996).

Following the concept of strategic assets of the resource-based theory, the key characteristics of IC as strategic assets are “their rarity, inimitability, non-substitutability and their unobservability” (Riahi-Belkaoui, Citation2003). Based on the above criteria, IC components are considered strategic assets (Hall, Citation1992). For example, RC is a valuable intangible asset. It is considered distinctive amongst companies and not similarly reproduced by competitors because they are only generated during business operations. Holland (Citation2003) identifies human and SC plays the central role of firm value creation. The views of Alum and Drucker (Citation1986) also recommend that in a turbulent and competitive environment, an enterprise’s SC is the key to raising its value. As such, IC in the view of strategic assets available only to a unique firm is its primary driver of competitive advantages and growth, determining how these assets are deployed to generate new competitive products or services (Amit & Schoemaker, Citation1993) with the aim of superior financial performance. The relationships between IC and each of these economic indicators (such as return on assets, return on equity or Tobin q), except for IE, were explored in many prior studies. Here, this study develops the correlation between IC components and IE, that little is known in the previous studies. The role of employees and well-organized structure, such as processes or procedures, is to facilitate the efficient allocation of capital (A. T. Le & Tran, Citation2022; Cao & Rees, Citation2020; Feng & Kim, Citation2021; Kong et al., Citation2018; Liu et al., Citation2023; Yang et al., Citation2022). It can be explained for two reasons. A well-organized infrastructure, i.e., a better internal control system, makes managers more accountable by allowing better monitoring; thereby, it can alleviate both under- and overinvestment problems. Besides, the well-standardized processes or procedures could also improve IE by enabling managers to make better investment decisions through better identification of adequate projects based on more truthful accounting information for internal decision-makers (A. T. Le & Tran, Citation2022; Bushman & Smith, Citation2001; Cao & Rees, Citation2020; Feng & Kim, Citation2021; Kong et al., Citation2018; Liu et al., Citation2023; Yang et al., Citation2022). Based on this discussion, this study examines that higher IC helps underinvestment companies to make more investments and overinvestment companies to decrease their investment level to gain the state of sustainable IE. The following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 3a:

There is a positive association between human capital and IE.

Hypothesis 3b:

There is a positive association between structural capital and IE.

Hypothesis 3c:

There is a positive association between relational capital and IE.

Concerning information management, Foster and Gupta (Citation1994) argue that if an organization’s strategic information processing does not adequately satisfy its needs, flawed or late decisions will result in suboptimal performance. Therefore, a condition correlation is assumed that better information facilitates more effective managerial decisions, enhancing corporate performance, including productivity, profitability and marketable value (Chenhall, Citation2003). SMA provides much vital information on customers, competitors, and cost management. As a result, that information facilitates the development and implementation of business strategies. It is not denied that the role of SMA in the strategic planning process is to promote the activities in terms of formulating strategy, communicating strategy, developing tactics for implementing strategy, monitoring and controlling performance (Shank & Govindarajan, Citation1993) as a tool to support the organization’s strategic intent. According to the strategic management theory, when business strategies are designed and managed more adequately, the organization’s performance will improve (Clancy & Collins, Citation2014). Many prior studies also investigated the relationship between SMA practices and corporate performance. For example, Cadez and Guilding (Citation2008) examine the impact of strategic choices, market orientation and firm size on SMA and the mediating effect of SMA on organizational performance. The case study research of Buhovac and Slapnicar (Citation2007) presents that organizations may not achieve high performance unless they use both financial and non-financial information provided by the SMA system that is well aligned with the business strategy. In this study, the author also recognizes the impact of SMA practices on IE. IE means undertaking all those projects with a positive net present value to maximize shareholders’ value (F. Chen et al., Citation2011). In other words, better SMA practices may improve IE by allowing managers to make better investment decisions by better identifying optimal projects and more truthful accounting numbers for internal decision-makers (Clancy & Collins, Citation2014). This relationship is motivated to be examined as follows:

Hypothesis 4:

SMA practices are positively associated with IE.

This study expects that a firm with strong IC in availability will make an effective usage of SMA practices, which in turn enhance productivity performance i.e., IE. A little research investigates that IC has an indirect relationship to IE. While most of the models follow the concept of classical organization economic paradigm (environment → strategy → performance), (e.g. Venkatraman (Citation1989)), or the concept of structural paradigm (strategy → practices → performance), (e.g. (Prajogo & Sohal, Citation2006; Spencer et al., Citation2009; Teeratansirikool et al., Citation2013)), this study uses a model of “resources → practices → productivity” relationship based on the resource-based theory. To strongly support this paper’s hypothesis, research evidence of Cadez and Guilding (Citation2008), using path analysis, found to indicate the link between strategy, accountants’ capability, SMA usage and productivity in the stages of these relationships. Here, Cadez and Guilding (Citation2008) study that highly professional accountants’ involvement, as the source of HC, in strategic decision making will appreciate of justifiability and maintenance of SMA system in order to add value to strategic decision-making process which leads to an enhanced positive result likelihood. Another research evidence is the study of Bangchokdee and Mia (Citation2016) indicating that the use of non-financial measures fully mediates the correlation between decision-making decentralization structure, as being SC of IC, and productivity performance in Thailand hotels. Even though the mediator between IC and productivity performance in Bangchokdee and Mia (Citation2016)’s paper is only one of SMA techniques (i.e. non-financial performance measures), this study’s outcome also confirms the mediating role of SMA practices in the correlation between a firm’s resource usage and productivity performance which is measured by one of the financial indicator, specified by IE. Although there is inconclusive evidence of the relationships among IC, SMA practices and IE, especially in the Vietnamese context, in this study, the author hypothesizes that:

Hypothesis 5a:

SMA practices mediate the positive relationship between human capital and IE.

Hypothesis 5b:

SMA practices mediate the positive relationship between structural capital and IE.

Hypothesis 5c:

SMA practices mediate the positive relationship between relational capital and IE.

5. Research design

5.1. Research model

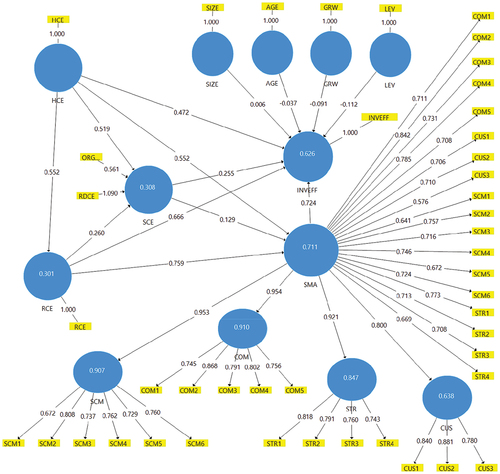

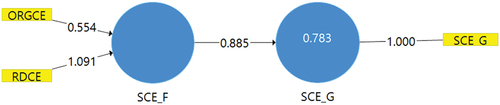

Based on the studies of Al-Mawali and Al-Shammari (Citation2013); Clancy and Collins (Citation2014); Clarke et al. (Citation2011); Chenhall (Citation2003); Kong et al. (Citation2018); Kweh et al. (Citation2021); Liu et al. (Citation2023); Ming-Chin et al. (Citation2005); Shiu (Citation2006), this paper developed a theoretical framework as shown in Figure to confirm the existence of the mediating role of SMA in the correlation between IC and IE. It indicates three IC dimensions affecting each other and affecting SMA practices. On the one hand, the research model also examines the direct effects of such three dimensions on IE (Kong et al., Citation2018). It also investigates whether IC affects IE via the mediating role of SMA practices to affirm the first and the second stage of the value-creating process by IC and SMA. The first stage points out a firm’s success starting with a firm’s capability not only to create IC with internal and external resources but also a firm’s capability to utilize the concrete of IC components stimulating the implementation of a better organizational system, such as the SMA approach. Afterwards, the added-value performance stage designates that IC’s efficiency has been contributing to enhancing a firm’s productivity (efficient investment). Previous studies only emphasize the relationship between IC and corporate performance; however, the entire process should include SMA practices. Without the SMA practices of a firm, IC cannot achieve better performance or productivity.

5.2. Independent variable - intellectual capital measurements

The primary method used to obtain data from archival sources that would allow IC constructs measurement is the “Value Added Intellectual Coefficient model” developed by Pulic (Citation2000). This study opted the VAIC model to measure IC because, Firer and Mitchell-Williams (Citation2003) point two advantages of VAIC, which are that (1) VAIC provide an easy-to-calculate, standardized and consistent basis of measurement to enable effectively comparative analysis across the firms; (2) data used to calculate VAIC are based on financial statement, which are usually audited by professional public accountants. Figure describes an overall picture of variables before starting to calculate the constructs of IC.

5.2.1. Human capital

The model starts with a company’s ability to create value added (VA). Consistent with Riahi-Belkaoui (Citation2003), Value added (VA) is defined as the gross value created by firm during the years can be expressed as Equation (5.1):

According to Pulic (Citation2000), human capital efficiency (HCE) is measured by how many dollars of value added an organization is able to generate for each dollar invested in its HC. HCE is calculated as follows:

Where:

HCE: HC efficiency

VA: Value added

HC: Human capital (total salaries and wages of a firm)

5.2.2. Structural capital and relational capital

Both SC and RC (SRC) are calculated as follows:

According to Nazari et al. (Citation2007), SC and RCE are dependent on HC, and greater HC translates into improved internal structures and external relationships. Therefore, if the efficiency measures for both HC, SC and RC efficiency are calculated with VA as the numerator, the logical inconsistency will remain (Pulic, Citation2000). When VA used in the numerator of SC and RC efficiency (SRCE), it does mean that every dollar of added value generated from HC may contribute into the improvement of internal structures and external relationships. Therefore, Pulic (Citation2000) calculates SRCE as:

SC and RC efficiency (SRCE) is the dollar of SRC within a firm, for each dollar of value added, and as HCE increases, SRCE increases. Alternatively:

Where:

SRCE: SC and RC efficiency

SCE: SC efficiency (SC is divided by VA)

RCE: RC efficiency (RC is divided by VA)

Moving to the lower level, SC is composed of innovation capital (RDC) and organizational capital (ORGC) (Nazari, Citation2010). SC is calculated based on its components as:

Equation of SCE can be re-arranged as equation (5.7), based on equation (5.6):

Or:

While:

RDCE: Innovation capital efficiency

OGRCE: Organizational capital efficiency

Research and development expenditure (R&D) has been used extensively in the literature as a proxy for innovation capacity (Bosworth & Rogers, Citation2001). The efficiency of innovation is calculated in the following manner:

This study measures cumulative R&D investment by lump sum value of the carrying amount of the prior years’ R&D investments. Therefore, an amortization rate is needed to measure cumulative R&D investment over multiple years. Following Lev and Sougiannis (Citation1996); Shangguan (Citation2005), this study accepts that R&D investment roughly is straightly depreciated within a 3-year economic life. The author is unable to apply a long duration of the depreciation in case the author may not collect enough data in a young Vietnamese stock exchange market where information has been fully available since 2010. On the basis of 3-year economic life, the cumulative R&D investment (RDC) in the year t is:

Where:

RDCi,t: Cumulative level of R&D investment in the year t

RDi,t: Level of R&D investment in the year t

RDi,t-1: Level of R&D investment in the year t − 1

RDi,t-2: Level of R&D investment in the year t − 2

Organizational capital appears to be essentially the accumulated knowledge used to combine human skills and physical capital into system for producing and delivering want-satisfying product (Shangguan, Citation2005). Following Equation (5.7), the efficiency of organizational capital is calculated in the following manner:

Firms rarely disclose expenditures on organizational capital in their financial statements. The measure of organizational capital involves the capitalization of selling, general administrative (SGA) spending, which is similar to the capitalization of research and development spending in Lev and Sougiannis (Citation1996). Although selling, general administrative spending is immediately expensed under Vietnamese accounting standard, it incorporates the spending on most organizational capital such as those in human resource, information technology, workplace practices, and marketing. Thus, the notion underlying the capitalization of R&D spending also applies to selling, general administrative spending. Additional arguments and evidence that SGA spending is a capital investment property are provided by Amir and Lev (Citation1996); Lev (Citation2001); Lev and Radhakrishnan (Citation2003). Here, SGA spending is applied to calculate organizational capital excluding employees’ salaries and wages because employees’ salaries and wages are reflected by the calculation of HC.

Firstly, this study conducts the following firm-level estimation by industry:

Where:

Log(Ei,t): Logarithm of annual earnings before depreciation, R&D, and SGA expenses in year t

Log(PPEi,t-1): Logarithm of book value of plant, property, and equipment in year t-1, representing the firm’s physical capital

Log(RDCi,t-1): Logarithm of accumulative level of R&D investment in the year t − 1, RDC is estimated in the model 4.10

Log(SGAi,t): Logarithm of selling, general administrative spending (excluding employees’ wages and salaries) in the year t

Log(SGAi,t-1): Logarithm of selling, general administrative spending (excluding employees’ wages and salaries) in the year t − 1

Log(SGAi,t-2): Logarithm of selling, general administrative spending (excluding employees’ wages and salaries) in the year t − 2

The rationale underlying EquationEquation 5.12(5.16)

(5.16) is, because SGA expenditures incorporate most organizational capital, they should generate future earnings for the firm. In other words, past SGA expenditures should affect current earnings. The amount of effect depends on the rates of organizational capital, that are represented by γ3, γ4, γ5 in EquationEquation 5.12

(5.16)

(5.16) As can be seen in EquationEquation 5.12

(5.16)

(5.16) , this study uses a maximum of 3 years of past SGA expenditures to influence current earnings so that the duration of R&D and SGA contributions on earnings are the same.

On the other hand, the empirical results from the simple correlations and multivariate regressions do not control for the potential endogeneity of SGAi,t and Ei,t (Shangguan, Citation2005). To control potential simultaneity bias, instrumental variables are identified as the exogenous component of SGA expenditures variable in 2-step regression approach. SGA expenditures might be joint endogenous variables driven by some underlying exogenous variables such as total assets and profitability. A firm’s SGA expenditure is expected to be consistent with its corresponding firm expenditure level, total assets (a proxy for firm size, TAi,t-1), and profitability in the previous year (ROAi,t-1). As procedures in the 2-step regression approach, in the first stage, SGAi,t is regressed against profitability and firm size to have estimates applied in the general model of the relationship between SGAi,t and log(Ei,t). This study adopts the following model in the first stage:

Where:

SGAi,t: Logarithm of selling, general administrative spending (excluding employees’ wages and salaries) in the year t

TAi,t-1: The natural logarithm of total assets in the year t − 1

ROAi,t-1: Profitability is the ratio of net profit to total assets in the year t − 1

After conducting the 2-step regression with Equation (5.13 and 5.12), the value of δ1, δ2, δ3 in Equation (5.12) are estimated by industry. This study’s measurement of organizational capital for firm-specific is based on the SGA amortization rates estimated by industry. Unlike measurement of R&D investment in Equation (5.10), where all current R&D spending is considered as capital investment, this study only capitalizes the unamortized SGA expenditure, while the amortized part is considered as operating expenses for the current period (Shangguan, Citation2005). After determining the value of δ1, δ2, δ3 in Equation (5.12) by industries, thus, δ1, δ2, δ3, if significant, represents the contribution of SGA expenditure in year t, t-1, t-2 to current earnings, ∑(δ1, δ2, δ3) represents the total earnings in year t contributed by SGA expenditures over t, t-1, t-2 years, while ω1 = δ1/∑(δ1, δ2, δ3); ω2 = δ2/∑(δ1, δ2, δ3); ω3 = δ3/∑(δ1, δ2, δ3) are the amortization rate of SGA expenditures in year t, t-1, t-2, respectively. After determining the value of ω1, ω2, ω3, the firm-specific level of organizational capital is measured by Equation (5.14).

Where:

SGAi,t: Selling, general administrative spending (excluding employees’ wages and salaries) divided by net revenue in the year t

SGAi,t-1: Selling, general administrative spending (excluding employees’ wages and salaries) divided by net revenue in the year t − 1

ORGC: Organizational capital

RC is a company’s ability to interact successfully with its external stakeholders in order to develop the potential of value creation. RC efficiency (RCE) is measured by the RC divided by value added. RCE means that the dollar of RC within a firm is generated from each dollar of value added. However, it is difficult to directly measure RC in financial term. Therefore, RCE is indirectly measured as the residual of IC efficiency after subtracting HC and SC efficiency. RC efficiency is simply equal to structural and RC efficiency minus SC efficiency. From Equation (5.5):

Hence,

5.3. Mediating variable - Strategic management accounting practices

SMA practices with 18 techniques are categorized into four groups: strategic cost management, competitor accounting, strategic accounting and customer accounting (Table ). To measure each construct related to the group of SMA techniques, variables are anchored by a 5-point Likert scale. The extent to which the various SMA techniques are calculated via the questions developed by (Cravens & Guilding, Citation2001; Guilding & McManus, Citation2002). The degree of usage is measured by posing the question, “To what extent does your organization use the following techniques?” Immediately following the questions, the 18 SMA techniques are listed together with a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (to a great extent). A response of 1 indicates the lowest usage, while a response of 5 indicates the most significant amount of using such an SMA technique being questioned.

Table 2. Evaluation of indicators and latent variables

5.4. Dependent variable - Investment efficiency

Conceptually, IE (INVEFF) means undertaking all projects with positive net present value. Biddle et al. (Citation2009) use a model that predicts investment in terms of growth opportunities. Specifically, IE will exist when there is no deviation from the expected level of investment. However, those companies that invest above their optimal (positive deviations from expected investment) over-invest, while those that do not carry out all profitable projects (negative deviations from expected investment) under-invest. Following Biddle et al. (Citation2009), in order to estimate the expected level of investment for firm i in year t, this study specifies a model that predicts the level of investment based on growth opportunities (measured by sales growth). Deviations from the model, as reflected in the error term of the investment model, represent the investment inefficiency. The residuals from the regression model below are used as a firm-specific proxy for investment inefficiency. A positive residual means that the firm is making investments at a higher rate than expected according to the sales growth, so it will over-invest. In contrast, a negative residual assumes that real investment is less than that expected, so it will represent an under-investment scenario. The dependent variable of IE (INVEFF) will be the absolute value of the residuals multiplied by −1, so a higher value means higher efficiency. This approach is used to measure IE in some pieces of research such as Biddle et al. (Citation2009), F. Chen et al. (Citation2011), Cutillas Gomariz & Sánchez Ballesta, (Citation2014).

where:

INVEST: Total investment of firm i in year t, defined as the net increase in total assets and scaled by the previous year’s total assets

PSALEG: The rate of change in sales of firm i from t − 2 to t − 1.

INVEFF: IE, the absolute value of residuals multiplied by −1

5.5. Control variables

Based on the previous studies of Anifowose et al. (Citation2018); Nadeem et al. (Citation2018); Rehman et al. (Citation2022); Titova and Sloka (Citation2022); Yahya and Ibrahim (Citation2021), this research controls some variables that can have impact of IE. Firm size (SIZE) is calculated by the natural logarithm of total assets, Firm age (AGE) is estimated by the number of listed years. Firm growth (GRW), which is measured using the change of firm’s revenue yearly and the final one is leverage (LEV), proxied by the ratio of debt over equity.

5.6. Selection of an appropriate regression approach

The structural equation modelling (SEM) approach deals with many mediators required to estimate complete causal networks simultaneously. There are two types of SEM. Firstly, covariance-based SEM is mainly used to confirm or reject a tested theoretical relationship by determining how well a proposed model can estimate the covariance matrix of a sample dataset (Hair & Hult, Citation2016). Secondly, partial least squares SEM (PLS-SEM) are primarily used to develop theories in exploratory research by concentrating on explaining the variance in the dependent variables in testing the model (Hair & Hult, Citation2016). The author decides to apply PLS-SEM because PLS-SEM handles a complex model (Hair & Hult, Citation2016). Barrett (Citation2007) suggests PLS-SEM has no identification issue with a small sample size. PLS-SEM generally does not assume the data distributions (Hair & Hult, Citation2016). PLS-SEM can easily handle reflective and formative measurement models (Hair & Hult, Citation2016). Examining measurement scales via the PLS-SEM approach enables researchers to evaluate the construct measures’ reliability and validity.

5.7. Research sample collection and data source

This study also applies both primary data and secondary data.

In terms of secondary data, this study uses financial data from 2022 annual or financial statement reports to extract sufficient data to calculate IC, IE and control variables. To collect financial data more conveniently, the observed business organizations are publicly traded enterprises listed on the Vietnamese Stock Exchange. Table describes the sample selection process.

Table 3. Sample selection process

For primary data, the data for the main study is collected through a questionnaire survey to investigate SMA practices applied in business organizations. The research survey is sent to SMA practitioners of publicly traded enterprises whose financial data are used to measure IC and IE. This study collects research data through two phases. The first phase is to send a survey via SurveyMonkey to the management of the public enterprises to collect information about SMA practices. The second phase is to collect the 2022 financial information about IC and the financial performance of the public companies where respondents work. To ensure that the informants are genuinely knowledgeable about the research topics, especially in the field of SMA, the key informants opt for the senior managers or members of the top management teams with knowledge about accounting, planning or finance and at least 2 years of working experience in the current organizations. It is because, according to Alavi and Leidner (Citation2001), it is difficult for an employee to have enough time to thoroughly understand the operational process, organizational structure and culture of such an organization within one-year of participation.

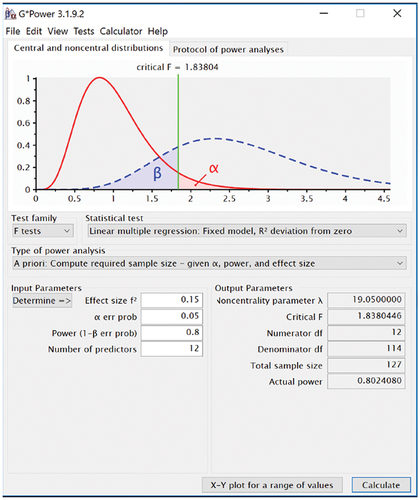

Faul et al. (Citation2007) suggest determining the necessary sample size for PLS-SEM based on the statistical power represented by the effect size (f2), the number of predictors and the significant level (α). As can be seen in Figure , the sample size of the research model is 127, respectively. Therefore, the minimum sample size applied consistently for the two research models will need 127 observations to achieve a statistical power of 80% for detecting R2 values of at least 0.25 (with a 5% probability error). In summary, the target sample size is expected to be at least 127 observations investigated in Vietnam research site, an Asian developing country.

Figure 3. Calculation of sample size of the research model.

The emails with survey link were sent to 250 potential informants, but only 192 completed responses of the corresponding number of listed companies were received. After eliminating 18 inappropriate responses, the sample consists of 174 satisfactory observations.

6. Empirical results and discussion

6.1. Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix

Under Pearson’s correlation, the correlation coefficients are not of high magnitude between any two independent variables to cause concern about multicollinearity problems. The relationships of HCE-SMA (0.551); SCE-SMA (0.514); RCE-SMA (0.829) are significantly positive, roughly supporting the second hypothesis that each of IC components is positively associated with the practices of SMA.

The correlation analyses show that, under Pearson’s correlation, all IC components are positively related to all the corporate performance indicators at a significant level. The results for IC components demonstrate that increased value creation efficiency will improve operational efficiency. This supports the third hypothesis that there are significant positive associations between IC components and IE. The relationship of SMA-INVEFF (0.776) is significantly positive, roughly supporting the fourth hypothesis that firms with more SMA practices positively affect IE.

According to the results in Table , VIF values all are uniformly below the threshold value of 2, except for the SMA variable under the weight of 5. It is concluded, therefore, that collinearity does not reach critical levels in any of the constructs and is not an issue for estimating the PLS path models.

Table 4. Collinearity statistics—inner VIF values

Regarding the research sample, the dominant industry is the manufacturing sector (35.63% of the total sample), followed by real estate and construction (18.39%), then mining and energy (12.64%). The model consists of 174 selected firms, representing 20% of 743 publicly traded companies in Vietnam’s Hochiminh and Hanoi Stock Exchange. In addition, like in many other countries, public enterprises are an essential component of the Vietnamese economy since the market capitalization value of listed companies consists of 26.8% of the Vietnamese GDP in 2018 (Trading Economics, Citation2018). According to General Statistics of Vietnam (GSO), in 2018, as regards the 2018 economic structure, the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector made up 16.32%; the industry and construction sectors accounted for 32.72%; the service sector was 40.92%. The data structure implies that the results of the data analyses may be more generalizable to manufacturing and construction firms than to service and agriculture firms.

There are 18 SMA techniques investigated, each assessed at a maximum of 5. Thus, the maximum value of SMA practices is 18 × 5 = 90. The author chooses 45 as the threshold to divide the sample into two groups. The group of high SMA practices takes the value of the SMA variable higher than 45, otherwise the lower-level group. As seen in Table , 70.11% of the sampled organizations are categorized into high-level SMA practices. 92.62% of the large enterprises have a higher level of SMA implementation. To check the appropriateness of an investigating organization in terms of having SMA implementation, the author used the tested questions extracted from the definition of SMA as follows: “Does your organization analyze management accounting data about a business and your competitors and your customers for use in developing and monitoring the business strategy?”. Some responses are eliminated if the informants opt for the “No” answer. By that, as it may, the appropriateness of the sampled organizations related to SMA practices was achieved to investigate the correlations between SMA practices and IC.

Table 5. The number of respondents by Organization size and SMA practices type

A respondent representing each organization to answer the questions in the survey are the executive using information obtained from the finance or accounting department and those directly interact with finance or accounting department. The respondents come from a variety of sectors (commercial finance, cost management, budgeting, accounting, planning and procurement). In the survey, the author used the testing question “What is your current highest position in your company?” with the three options related to top management, middle management and non-management staff so as to check the appropriateness of the respondents before continuing with the following questions. However, the author categorises into 7 groups (see Table ). Statistical results of the sample by position and working years in the current position show that the informants are finance managers (27.01%), followed by reporting managers (20.11%), then by the head of the department (14.36%) and general managers (14.36%). All respondents are from senior managers or members of top management team with knowledge about accounting, planning or finance and at least 2 years of working experience in the current organizations.

Table 6. Number of Respondents by Positions type and Working Years type in the current organization

6.2. Measurement scales assessment