?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

There is still no clear agreement between previous studies regarding the association between leadership effectiveness (LE) and emotional intelligence (EI), and the moderating effect of gender. In the current study, we tested the impact of (EI) on (LE) and the moderating role of gender on this relationship. We employed Hierarchical Moderated Multiple Regression analysis (MMR) for our data, which we collected from 141 questionnaires using a non-probabilistic technique from Fast-moving consumer good (FMCG) in Egypt. We found that EI is positively related to LE. The gender variable moderated both the relationship between others’ emotional appraisal and LE and use of emotion and LE. Specifically, others’ emotional appraisal was positively associated with LE for females, but almost unrelated for males; whereas the positive relationship between use of emotion and LE was stronger for males compared to females. The current study highlights the crucial role that human resource development and training would play in augmenting EI skills for both female and male leaders in general, and how each gender needs to better develop understanding on the other gender emotional positions. Our data was collected from a small sample of only two organizations, which hinders our ability in generalizing the findings to other organizations. While conducting future research, these aspects should be kept in mind, which can provide more valuable results. Conducting this study in Egypt contributes to the international learning experience on EI and LE in countries other than Western ones.

1. Introduction

Studies have investigated leadership effectiveness (LE) as a process of influencing others to accomplish shared objectives (Mihalescu & Niculescu, Citation2007). Most studies have been published from a European context, and the question is whether these studies are applicable to other cross-cultural contexts (Hage & Posner, Citation2015; Mousa et al., Citation2019), as terminologies and behaviors may have different meanings and understandings across cultures (Chen et al., 2015). Furthermore, some studies have shown the importance of gender in moderating the relationship of emotional intelligence (EI) and LE (Amagoh, Citation2009; D. B. Rice & Reed, Citation2021; George, Citation2000; Kerr et al., Citation2006), whilst other studies revealed mixed findings between EI, LE and gender of leaders (Burke & Collins, Citation2001; Simon & Nath, Citation2004).

In fact, there is still no clear agreement between previous studies regarding the relationship between EI and LE, and the moderating effect of gender, with limited research investigating the variables in developing countries, such as the Middle East (Kabasakal et al., Citation2012), including Egypt (Sidani & Jamali, Citation2009). Egypt is described as a society in which relationships are more important than rules and regulations; and when precedence is given to group more than individual needs; expressive emotionally; work relationships are attached to individual affiliations; interest and concern for the social standing of others rather than achievements (Cullina, Citation2016). However, the country is experiencing changes in its leadership culture, where Egyptians are more open to being Westernized (G. Rice, Citation2011), and authoritarian leadership style dominates Egyptian organizations (Shahin & Wright, Citation2004).

Most previous studies on EI have been performed in a European context, which makes it difficult to generalize to other cultures (Giorgi, Citation2013). Therefore, the current study gives a unique contribution that has not been explored yet in the Egyptian context and in similar countries. We explored whether women leaders in Egypt are more emotionally intelligent than men and how does (EI) impact (LE). The aim of the current study is to answer the following question: Are Egyptian women more emotionally intelligent than men and how could this impact the effectiveness of their leadership? We collected data from a Fast-Moving Consumer Goods industry (FMCG), as this industry is described to be constantly evolving in Egypt, and has equal gender positions at leadership levels with its dynamic nature which makes it easier to see quick key performance outcomes as a result of leadership decisions.

2. Literature review and hypotheses development

2.1. Leadership and LE

We defined leadership as a social influence process (Erkutlu & Tatoglu, Citation2008) between leaders and followers (Posner, Citation2015) to motivate people to act by non-coercive means (Amagoh, Citation2009) through the charisma, power and persuasion of a leader (Schafer, Citation2010) to achieve transformative change (Manning & Robertson, Citation2011) by leaders’ crucial role of eliminating obstacles for followers (Howard & Irving, Citation2014).

Researchers stress the importance of leadership in managing successful strategic change (Al-Amir et al., Citation2019), and organizations are gradually directing their efforts on evaluating and developing leaders at all levels (Zagorsek et al., Citation2006). Amagoh (Citation2009) argued that institutions who practice effective leadership are more likely to be pioneering and flexible. Furthermore, research suggests that leadership is a key indicator in organization performance (Erkutlu & Tatoglu, Citation2008; Manning & Robertson, Citation2011; McDermott et al., Citation2011) and shapes organizational effectiveness, subordinate behaviour, and both individual and group outputs (Manning & Robertson, Citation2011; Schafer, Citation2010). Michel et al. (Citation2014) argue that the personality characteristics of each person will be the criteria to decide effective from non-effective leaders. However, job performance is still considered by other authors to be a parameter of leadership, by using performance appraisals and managerial ratings in deciding future leaders (Dries et al., Citation2012; Lacey and Groves, 2014; Juhdi et al., Citation2015; Posthumus et al., Citation2016).

On the contrary, performance is not necessarily a feasible reliable indicator of leader potential (Lombardo & Eichinger, Citation2000), and leadership is more than job performance (Miller & Desmarais, Citation2007). Some researchers criticize the reliance on evaluating performance to measure leadership, and they argue that people need different set of skill and wider responsibilities in future leadership roles (Greer & Virick, Citation2008; Lombardo & Eichinger, Citation2000), even though personal performance might be high, this does not necessarily mean that this person is the most appropriate for a leadership role.

According to Chen and Silverthorne (Citation2005), LE is described as the leader’s ability and readiness to apply an appropriate leadership style that meets the needs of the follower. Howard and Irving (Citation2014) see the effective leader as the one who removes obstacles for leading change in an organization. Liu et al. (Citation2002) argued that LE is the extent to which staff think that their managers are effective leaders who possess a transformational style (TL) to influence their followers to achieve goals (Al-Amir et al., Citation2019; Muppidathi & Krishnan, Citation2021; Sivanathan & Cynthia Fekken, Citation2002). Several studies reported positive impact of TL on LE (Al-Amir et al., Citation2019; Judge & Piccolo, Citation2004; O’Shea et al., Citation2009). Moreover, the relationship of EI, TL and LE have been further explored by other researchers who found that managers who are rated more effective leaders by their team members are more likely to possess aspects of EI and TL (Chatterjee & Kulakli, Citation2015; J. Li & Zahran, Citation2014).

2.2. EI in the organizational context

Emotions in the workplace have been studied for many years (Downey et al., Citation2006). EI is believed to be the degree to which individuals differ in perceiving, understanding and controlling their own emotions and the emotions of others, and being able to integrate these with their own thoughts and actions (Bardzil & Slaski, Citation2003; Carmeli et al., Citation2009; Giorgi, Citation2013; Moon & Morley, Citation2010; Naderi, Citation2012). More specifically, EI is the capacity of recognizing own feelings and those of others (Bagshaw, Citation2000), and the ability to monitor such emotions to guide one’s thinking and actions (Fatt, 2002) in his or her given environment (Sivanathan & Cynthia Fekken, Citation2002) to reflect emotions into exchangeable tangible outcomes (Landen, Citation2002).

The concept of EI has received significant attention in applied organizational studies showing the ability of individuals to contribute to the success of the organization (Stein and Book, 2003; Bar-On, Citation2004). Other research shows that more than 90% of success is returned to EI (Fatt, 2002; Michinov & Michinov, Citation2022). In addition, EI has been discussed in different theories of leadership to develop positive and productive relations within organizations (Ashkanasy & Daus, Citation2002; Michinov & Michinov, Citation2022), and as a better predictor of management and leadership success in the organizations than IQ (Bardzil & Slaski, Citation2003).

2.3. Conceptual framework (Hypotheses development)

Previous studies have provided a background to hypothesize the positive relationship between EI and LE where higher EI scores are associated with higher LE (Amagoh, Citation2009; D. B. Rice & Reed, Citation2021; Kerr et al., Citation2006; Sivanathan & Cynthia Fekken, Citation2002). For example, EI is seen as a main predictor of leadership and management success in the organizations (Bardzil & Slaski, Citation2003; Schreyer et al., Citation2021) because emotionally intelligent leaders produce high performing organizational business outcomes (Schumacher et al., 2009; D. B. Rice & Reed, Citation2021), and workers with more developed EI possibly have positive insights of the organizational climate, as they communicate ideas, intentions and goals more effectively (Giorgi, Citation2013).

According to Z. Li et al. (Citation2016), the ability to read the emotions of an individual facilitates the self-control of emotions, and leaders who are in a better place to recognize their emotions are more able to manage their emotions and the emotional requirements of followers. In this context, Thory (Citation2013) identifies the use of deployment of attention, cognitive change and modulation of response as main strategies to regulate emotions during situations of interpersonal conflict, interactions, and organizational change. Riggio et al. (Citation2008) argued that the emotions control of a leader is positively related to EL. Studies such as Howard and Irving (Citation2014), McDermott et al. (Citation2011), and Dabke (Citation2016) also found a significant positive correlation between followers’ perception of LE and EI. Accordingly, the first main and sub hypotheses are:

H1:

There is a positive significant relationship between EI and LE.

H1a:

Self-emotion appraisal positively relates to LE.

H1b:

Other’s emotion appraisal positively relates to LE.

H1c:

Use of emotions positively relates to LE.

H1d:

Regulation of emotions positively relates to LE.

Other studies argued that men and women are expressing their emotions differently when linked to LE (George, Citation2000). LE has been always understood in the context of masculinity, when women might react to that by managing their expressiveness (Vecchio, Citation2002). It was concluded that women who are successful in a workplace which is dominated by men do not give a value to emotional expression; however, male leaders are not viewed negatively when they fail to exhibit their emotions (Eagly & Karau, Citation2002), as expectations regarding the use of emotions by male leaders is driven by the differences of the style of communications between males and females (Byron, Citation2008). Leadership and management have always been masculine areas with lower female expressiveness (Hatcher, Citation2003; Kidder & Parks, Citation2001; LaFrance et al., Citation2003). However, the difference between male and female leaders is still a question to be answered (Burke & Collins, Citation2001; Simon & Nath, Citation2004). While others believe that female are more expressive than male leaders (Van Rooy & Viswesvaran, Citation2004; Vecchio, Citation2002).

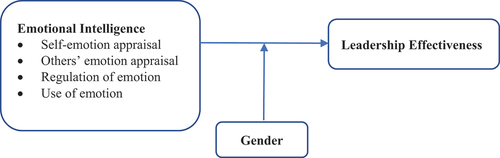

Based on the above, the contribution of our study is based on investigating the impact of EI on LE and how gender might affect this relationship (see Figure ). Accordingly, our second main and sub hypotheses are:

H2:

Gender moderates the relationship between EI and LE.

H2a:

Gender moderates the relationship between self-emotion appraisal and LE.

H2b:

Gender moderates the relationship between others’ emotion appraisals and LE.

H2c:

Gender moderates the relationship between use of emotions and LE.

H2d:

Gender moderates the relationship between regulation of emotions and LE.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data collection and sampling

This current study aims to investigate the impact of EI on LE for employees in a multinational FMCG sector in Egypt. The research involves the administration of structured, closed ended and self-administered questionnaire. Appendix 1 shows the descriptions of all items used to measure each of the variables. The questionnaires have been distributed conveniently by the researchers during the second quarter of 2016 at two largest FMCG providers in Egypt which count more than 3000 employees.

The authors used the convenience sampling method, which is one type of the non-probability technique, and refers to the collection of information from people who are ready to provide it (Sekaran & Bougie, Citation2013). The reason why the authors have used convenience sampling is because it was supported as an effective tool used by previous researchers such as (Sivanathan & Cynthia Fekken, Citation2002) to study the relationship between the same variables of this study.

The respondents included employees from various levels with the exclusion of the managing directors and the unskilled/uneducated staff members. The unskilled staff members include all staff members who work in the production assembly lines or those who do not have any formal educational qualifications. They were excluded from the population due to concerns that they might not have understood the purpose of the current study or might even be illiterate. The sample size of the current study was calculated based on the sample population developed by (Sekaran & Bougie, Citation2013). The authors collected 141 (manually and electronically) fully completed questionnaires which were used for further analysis. This sample size is considered adequate for the current research as it meets and exceeds the thresholds of 10 observations per estimated parameter (Bentler & Chou, Citation1987; Bollen, Citation1989).

3.2. Research instruments

We developed an integrated questionnaire by merging scales of the different variables (see Appendix 1). The questionnaire consisted of three parts as follows: EI, LE and demographic questions. Two instruments were used in the current study, which are: Leadership Practice Inventory model (LPI) developed by (Posner & Kouzes, Citation1993) and Wong and Law EI Scale (WLEIS) developed by (Wong & Law, Citation2002). It is to be noted that the authors, when measuring LE, excluded objective measures criteria such as productivity, profitability, turnover rate due to the confidentiality and difficulty of obtaining such figures.

WLEIS questionnaire which was designed for better application in countries in the Far East (Law et al., Citation2004; Wong & Law, Citation2002), as it predicts job performance better than other scales. WLEIS is a 16-item self-report measure with four dimensions: self-emotion appraisal, for example “I really understand what I feel”; others’ emotion appraisal, for example “I always know my friends’ emotions from their behaviour”; regulation of emotion, for example “I am able to control my temper and handle difficulties rationally”; and use of emotion, for example “I always set goals for myself and then try my best to achieve them”; items were answered on a Likert scale ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”. The validity of (WLEIS) was measured by several authors such as Kong (Citation2017) who found that configural, metric and scalar invariance across gender groups were supported, and that latent mean scores on the WLEIS subscales were comparable across gender groups.

The LPI tool was developed and revised over many years (Posner & Kouzes, Citation1993), and has two forms which are LPI-Self and LPI-Other (Sumner et al., Citation2006). In the current study, we used LPI-self questionnaire to measure the self-perceived LE. LPI is a 30-item scale, with five subscales (6 items for each subscale). The five subscales are as follows: modelling the way; inspiring a shared vision; challenging the practice; empowering others to act; and pushing the heart (The Five Practices of Exemplary Leadership).

4. Analysis and results

4.1. Sample characteristics

Table describes the main characteristics of our sample:

Table 1. Sample characteristics (source: Authors’ calculation)

4.2. Measurement model assessment

A Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was run to estimate the quality of the factor structure and loadings. The CFA results suggested the measurement model had an acceptable fit to the data according to Hu and Bentler (Citation1999). Indices for the measurement model were CFI=.977; NFI=.938; TLI=.880; RMSEA=.060, SRMR=.035 and the P value of the model is 0.000. Convergent validity seemed to be established for the factors, as all the factor loadings are more than 0.457 (Hair et al., Citation2010).

4.3. Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics, intercorrelations for the current study variables and reliabilities are presented in Table . All the correlation coefficients (except for the proposed moderator “gender”) were significant, supporting H1 set of hypotheses There was no evidence of multicollinearity among the four predictors (.422 > r > .642). The relationships between the dimensions of EI and the relationship between EI and LE were both significant. All measures demonstrated good levels of reliability since alpha coefficients are sufficiently internally consistent with Cronbach’s alpha for all measures are >.858.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and correlations for all study variables (source: Authors’ calculation)

4.4. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis

To test the two sets of hypotheses of the current study, Hierarchical Moderated Multiple Regression analysis (MMR) was employed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM, SPSS, 22) and PROCESS Macros for SPSS (v3.4) (Hayes, Citation2018). The MMR was carried out in eight steps. In step 1, the independent variables (self-emotion appraisal, others emotional appraisal, use of emotion and regulation of emotions) were entered into the model as predictors and the moderator (gender) was entered as a control variable. These variables are not necessary to be significant predictors of the outcome variable (LE) at this stage to test for an interaction effect at later stages (Bennett, Citation2000). This step allows testing the effects of the independent and control variables as well as identifying the model R Square and significance and therefore testing the H1 set of hypotheses before introducing the effects of moderation (interaction outcomes). Next, the moderation effects of (gender) were introduced to the previous model and further hierarchical moderated multiple regression analysis were performed to detect the four interaction effects of (gender), each at a time, in the next four steps (steps 2 to 5). Then, the interactions were added to the model together, one by one. These further regressions were used to test H2 set of hypotheses and examine whether gender moderates the relationship between LE and the four sub variables representing EI. Each interaction, in steps 6 to 8, was added to the previous model in a separate step to identify the change in R square of the model and check if it was significant. Moderation is considered to occur when the magnitude, direction, or both relation between LE and EI’s four sub-dependent variables are affected by gender. Results of the MMR analysis are presented in . shows the eight models resulted from the eight steps/regressions, their specifications, coefficient estimates and significance.

Table 3. Hierarchical multiple regression results (source: Authors’ calculation)

The first regression analysis was performed in order to test H1 set of hypotheses and examine the relationship between EI and LI. In the first model LE was regressed on the independent variables of EI (self-emotion appraisal, others emotional appraisal, use of emotion and regulation of emotions) and (gender) as a control variable. The results of this regression appear under Model 1 of . According to Model 1 results, self-emotion appraisal, others emotional appraisal, use of emotion and regulation of emotions were strongly and positively associated with LE and this association is significant (P values <.01). The gender was negatively associated with LE but this was only significant at .10 level of confidence. Model 1 was significant at P < .01and Adjusted was .60 and H1 set of hypotheses (H1a, H1b, H1c and H1d) are all accepted.

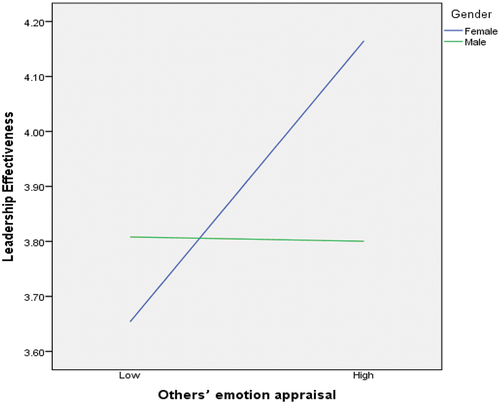

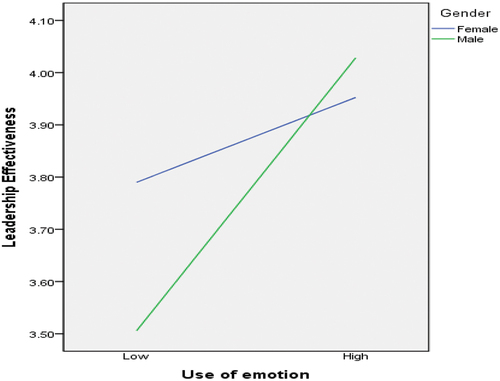

In Table , from the second to the eighth, models, the moderation effects of (gender) on the relationships among the four dimensions of EI and LE were examined. The results indicated that two of the four interaction terms were significant or approached significance as the interaction of others’ emotion appraisal and gender was significantly associated with LE (B = .14, P < 0.05) according to model 3, (B = .23, P < 0.05) according to model 6, (B = .24, P < 0.01) according to model 7, and (B = .26, P < 0.01) according to model 8, suggesting a significant moderation effect (∆=.0187, P < .05) as seen in model 6. The interaction of use of emotion and gender was significantly associated with LE only at .10 level (B = .10 in model 4 and B = .18 in model 7) suggesting another moderation effect of gender (∆

=.0075, P < .10) as seen in model 7. More specifically, gender turned out to moderate the relationship between others’ emotion appraisal and LE and the relationship between use of emotion and LE as Model 8 was significant and suggested that the two significant interactions and EI predictors explained 80% of the variability of LE. Accordingly, only H2b is accepted and H2c is retained (see Models 2 to 8 in Table ). For a summary of the outcome of the hypothesis test, see Table .

Table 4. Hypotheses outcomes (source: the Authors)

The two significant/approaching significance interactions were retained for further analyses. These interactions are graphically represented in . Values for the moderator were chosen 1 S.D. below and above the mean. Entering these values in the regression equation generated simple regression lines showing the regression slops for males and females. The lines in show the influence of others’emotion appraisal on LE have decreasing and increasing functions varying according to gender. Although the relationship between others’ emotion appraisal and LE seemed weak or unrelated for male participants, the higher levels of others’ emotion appraisal have a small negative influence on LE by the decreasing slope. Oppositely, slope reverses the direction of the line for females implying that the positive level of influence that others’ emotion appraisal has on LE increases for females.

Figure 2. MMR slopes; a moderation effect of gender on the relationship between others’emotion appraisal and LE (Authors’ calculation).

Figure 3. MMR slopes; a moderation effect of gender on the relationship between use of emotion and LE (Authors’ calculation).

The moderation effects in Figure indicated a similar pattern for males and females, showing that the level of use of emotion had a positive effect on the level of LE. Specifically, when males and females have high levels of use of emotion, they tended to have higher levels of LE. However, males showed higher LE levels when they have a higher level of use of emotion compared to females. The finding implies that EI is positively associated with LE, however, gender plays a role in moderating this association as different levels of males’ and females’ EI affect the strength of this association suggesting that some measures of EI are strongly associated with higher levels of females’ LE but other EI measures are strongly associated with higher levels of males’ LE.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical implications

The current study showed that EI has a strong relationship with LE from the perspective of Egyptian employees which goes with the results of previous studies in the field (Boyatzis et al., Citation2017; Kerr et al., Citation2006; Riggio et al., Citation2008; Sivanathan & Cynthia Fekken, Citation2002). EI contributes to the capacity of people to effectively work in groups, control stress, and lead others (Rosete & Ciarrochi, Citation2005). In addition, EI helps in improving leadership and performance, thus affects LE (Leary et al., Citation2009). The current study concluded that EI is an indicator of LE, and that other’s emotion appraisal was the most EI factor impacting LE. Regulation of emotions was found to be difficult to manage, but it is a factor influencing LE.

The findings further showed that although gender was not a significant predictor of LE in the Egyptian context, it played a key role in moderating the relationship between others’ emotions appraisal and LE and between use of emotion and LE but did not moderate the relationship of the other two measurements (i.e. self-emotion appraisal and regulation of emotion). The relationship between others’ emotion appraisal and LE was weak or unrelated for male participants but others’ emotion appraisal strongly and positively influenced LE for females suggesting others’ emotion appraisal is a key skill for women’s LE. Moreover, although the use of emotion had a positive effect on the level of LE for men and women, men showed higher LE levels when they have higher levels of use of emotion compared to females. The current study concluded that EI is positively influence LE, however, gender plays a role in moderating this relationship as different levels of males’ and females’ EI affect the strength of their LE differently. Accordingly, some measures of EI (others’ emotions appraisal) strongly and positively affect females’ LE but other EI measures (use of emotion) have stronger positive effects on the levels of males’ LE compared to those of females.

The moderation effect of gender on the relationship between others’ emotions appraisal and LE could be explained in the light of prior literature which argues that leaders’ ability to appraise others’ emotions differ from male to female and that female’s ability to appraise and understand others’ emotions better than males, this could enable them to be more effective leaders than males (George, Citation2000; Hatcher, Citation2003; Martínez-Marín et al., Citation2021; Ramachandaran et al., Citation2017; Van Rooy & Viswesvaran, Citation2004; Vecchio, Citation2002).

As shown earlier, little attention had been drawn towards the topic of EI and LE in the (MENA) region; studies were either conducted by Western or local management scholars. Such a controversial topic puts a heavy weight on cultural factors making it even much more important to examine results in different cultures. Accordingly, in his study, Moon and Morley (Citation2010) states that EI is dependent on knowledge with a specific context that could not be applicable to the others cultures. Therefore, the current study gives a unique perspective that has not been explored yet in the Egyptian context and the context of similar countries and will thus add significant value as the results confirm the EI, LE relationship in the Egyptian context as suggested by prior research in other western cultures (Boyatzis et al., Citation2017; Kerr et al., Citation2006; Leary et al., Citation2009; Riggio et al., Citation2008; Rosete & Ciarrochi, Citation2005; Sivanathan & Cynthia Fekken, Citation2002). The currentstudy also shows a good internal consistency and validity consistent with the Wong and Law EI Scale (WLEIS) which was developed for the use in organizations in the Far East (Wong & Law, Citation2002). Although earlier studies found clear differences between males’ and females’ levels of EI and LE (George, Citation2000; Hatcher, Citation2003; Shaaban, Citation2018; Van Rooy & Viswesvaran, Citation2004; Vecchio, Citation2002).

In the context of Egypt, the culture is described to be more masculine (Hofstede et al., Citation2010), and managers in Egypt are moderately possessing an autonomous leadership style (Graen, Citation2006; Shi & Wang, Citation2011), with a high level of personal attachment (Elsaid & Elsaid, Citation2012). Context of similar cultural differences on emotions, leadership, and gender perspectives was found by other researchers (Abalkhail & Allan, Citation2015; Cho et al., Citation2020; Claus et al., Citation2013; J. Li et al., Citation2020). Mousa et al. Citation2020, a&b found that Egyptian females respond to diversity leadership and management practices and protocols more positively than their male colleagues. Shaaban (Citation2018) found that Egyptian female employees have high levels of TL style behavior comparing to male managers, and that Egyptian males’ leadership style is more oriented to the style of transactional leadership, and females were found scoring higher than male in EI and emotional repair. Similarly, Metwally (Citation2014) asserted that TL has a gender bias in Egypt, where women leaders are predisposed of traits more conducive to TL comparing to men, and when such type of leadership requires an emotional attachment between leader and follower.

Overall, the current study provides a significant contribution in this area as it clarifies the gender’s role in moderating the relationship between some dimensions of the EI and LE as the results suggest some measures of EI (others’ emotions appraisal) strongly and positively affect females’ LE but other EI measures (use of emotion) have stronger positive effects on the levels of males’ LE compared to those of females. Whether these latest results are unique to the Egyptian culture is an issue to be investigated by future researchers.

5.2. Practical implications

Organizations could use the information resulted from the current study to improve or develop their leaders’ EI and increase their effectiveness. In general, the findings of the current study have two practical implications. First, given the results, it is now known that self-emotion appraisal, use of emotions, others emotion appraisal and regulation of emotions, all impact LE. This calls for greater involvement in guiding managers to develop their EI to enhance their LE. Second, as the gender does not necessarily affect the relationship between EI and LE, this will provide companies with a useful supporting decision tool when recruiting managers by excluding the gender factor and rather considering EI of individuals, whether males or females.

Despite that D’Annunzio-Green and Francis (Citation2005) questioned the potential of human resource development interventions in this context, Clarke (Citation2006) proposed that emotional abilities can be developed using workplace learning methods where competences in EI are likely to be learned and understood within the context of the workplace. Similarly, Zea et al. (Citation2020) provide evidence that training and interventions on EI could help, enhance, and control the person’s ability to control stress in complex environments such as military. Stead (Citation2014) argues that women’s perceptions of gendered power relations in action learning confirm the reality of dominance of male leaders, and the principles of trust of action learning could help avoiding difference between males and females.

The current study produces opportunities for future developments, as organizations in Egypt and similar countries could use the findings to improve and/or develop EI and trainings to create future effective leaders. The current study also highlights the importance in augmenting EI skills for both females and males’ leaders in general, and how each gender needs to better develop understanding on the other gender emotional positions.

5.3. Limitations

The variables of the current study were self-reported at single time point using only self-reported EI measure (WLEIS) tool which could increase concerns around common method variance, and may include bias (Clarke, Citation2010; Libbrecht et al., Citation2010). For example, such EI measures could have the concern of measuring participants’ self-efficacy or confidence more than they are measuring actual EI (e.g., there could be participants who are actually low in EI but who think they are highly emotionally intelligence; these participants with low EI will score high on a self-report EI measure). Bru-Luna et al. (Citation2021) reported that most of the self-reported instruments are grouped under three main conceptual models (ability, trait and mixed), and each model has a number of advantages and disadvantages. In the ability model, it is not possible to adulterate the results by strategic responses and they tend to be more attractive tests. The trait-based model, on the other hand, employs measures that have no right or wrong answers, so they result in emotional profiles that are more advantageous in some contexts than others, and they tend to have very good psychometric properties. However, they are susceptible to falsification and social desirability.

The data of the current study was collected from a relatively small sample of only two organizations, which hinders our ability in generalizing the findings to other organizations. However, we conducted the study in Egypt, with the Egyptian culture and its impact on females and male leaders, which is important, and could be the basis for further research. While conducting future research, these aspects should be kept in mind, and used as a basis for framing and conducting further research in the Egyptian context.

6. Conclusion

The current study paves the way towards research around strategies and programs of developing EI. Also, multiple case studies could be done to compare different multinational FMCGs on how EI impacts LE. A longitudinal study would be beneficial to study how the variables change over time. Finally, replication of the current study is important, as to help gaining a better understanding on how different cultures may play a role in this relationship between EI on LE. Therefore, the current study emphasized a need for in-depth research on the differences between the practices of human resources management across cultures and countries (Brewster, Citation2004; Browaeys & Price, Citation2011). Understanding culture differences is the key in customizing human resource development research and practice around the world (J. Li, Citation2015).

Availability of data statement

The authors will provide data used in this manuscript upon request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Yasmine Nabih

Yasmine Nabih, Assistant Lecturer, Arab Academy for Science and Technology, Egypt.

Hiba K. Massoud

Hiba K. Massoud, Senior Lecturer, Cardiff Metropolitan University, UK.

Rami M. Ayoubi

Rami M. Ayoubi, Associate Professor, Coventry University and Editor in Chief for Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, UK, Corresponding author), email [email protected]

Megan Crawford

Megan Crawford, Theme Lead and Professor for Educational Leadership and Policy Coventry University, Global Learning Centre, UK.

References

- Abalkhail, J. M., & Allan, B. (2015). Women’s career advancement: Mentoring and networking in Saudi Arabia and the UK. Human Resource Development International, 18(2), 153–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2015.1026548

- Al-Amir, I., Ayoubi, R. M., Massoud, H., & Al-Hallak, L. (2019). Transformational leadership, organisational justice and organisational outcomes: A study from the Higher Education sector in Syria? Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 40(7), 749–763. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-01-2019-0033

- Amagoh, F. (2009). Leadership development and leadership effectiveness. Management Decision, 47(6), 989–999. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740910966695

- Ashkanasy, N., & Daus, C. (2002). Emotion in the workplace: The new challenge for managers. Academy of Management Executive, 16(1), 76–86. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2002.6640191

- Bagshaw, M. (2000). Emotional intelligence – training people to be affective so they can be effective. Industrial and Commercial Training, 32(2), 61–65. https://doi.org/10.1108/00197850010320699

- Bardzil, P., & Slaski, M. (2003). Emotional intelligence: Fundamental competencies for enhanced service provision. Managing Service Quality, 13(2), 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604520310466789

- Bar-On, R. (2004). The Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i): Rationale, description and summary of psychometric properties. In G. Geher (Ed.), Measuring emotional intelligence: Common ground and controversy (pp. 115–145). Nova Science Publishers.

- Bennett, J. (2000). Focus on research methods mediator and moderator variables in nursing research: Conceptual and statistical differences. Research in Nursing & Health, 23(5), 415–420.

- Bentler, P. M., & Chou, C. H. (1987). Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological Methods & Research, 16(1), 78–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124187016001004

- Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural Equations with Latent Variables. John Wiley.

- Boyatzis, R., Rochford, K., & Cavanagh, K. (2017). Emotional intelligence competencies in engineer’s effectiveness and engagement. Career Development International, 22(1), 70–86. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-08-2016-0136

- Brewster, C. (2004). European perspectives on human resource management. Human Resource Management Review, 14(4), 365–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2004.10.001

- Browaeys, M. J., & Price, R. (2011). Understanding Cross-Cultural Management (2nd ed.). Financial Times-Prentice Hall.

- Bru-Luna, L. M., Martí-Vilar, M., Merino-Soto, C., & Cervera-Santiago, J. (2021). Emotional intelligence measures: A systematic review. Healthcare, 9(12), 1696. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9121696

- Burke, S., & Collins, K. (2001). Gender differences in leadership styles and management skills. Women in Management Review, 16(5), 244–257. https://doi.org/10.1108/09649420110395728

- Byron, K. (2008). Differential effects of male and female managers’ non‐verbal emotional skills on employees’ ratings. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(2), 118–134. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940810850772

- Carmeli, A., Yitzhak‐halevy, M., & Weisberg, J. (2009). The relationship between emotional intelligence and psychological wellbeing. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 24(1), 66–78. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940910922546

- Chatterjee, A., & Kulakli, A. (2015). An empirical investigation of the relationship between emotional intelligence, transactional and transformational leadership styles in banking sector. Procedia - Social & Behavioral Sciences, 210, 291–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.369

- Chen, J., & Silverthorne, C. (2005). Leadership effectiveness, leadership style and employee readiness. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 26(4), 280–288. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730510600652

- Cho, Y., Li, J., & Chaudhuri, S. (2020). Women entrepreneurs in Asia: Eight country studies/Editorial. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 22(2), 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422320907042

- Clarke, N. (2006). Developing emotional intelligence through workplace learning: Findings from a case study in healthcare. Human Resource Development International, 9(4), 447–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678860601032585

- Clarke, N. (2010). Developing emotional intelligence abilities through team-based learning. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 21(2), 119–137. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.20036

- Claus, V. A., Callahan, J., & Sandlin, J. R. (2013). Culture and leadership: Women in nonprofit and for-profit leadership positions within the European Union. Human Resource Development International, 16(3), 330–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2013.792489

- Cullina, H. T. (2016). Leadership Development in Egypt: How Indigenous Managers Construe Western Leadership Theories. Heriot-Watt University.

- Dabke, D. (2016). Impact of leader’s emotional intelligence and transformational behavior on perceived leadership effectiveness: A multiple source view. Business Perspective and Research, 4(1), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/2278533715605433

- D’Annunzio-Green, N., & Francis, H. (2005). Human resource development and the psychological contract: Great expectations or false hopes? Human Resource Development International, 8(3), 327–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678860500199725

- Downey, L., Papageorgiou, V., & Stough, C. (2006). Examining the relationship between leadership, emotional intelligence and intuition in senior female managers. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 27(4), 250–264. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730610666019

- Dries, N., Vantilborgh, T., & Pepermans, R. (2012). The role of learning agility and career variety in the identification and development of high potential employees. Personnel Review, 41(3), 340–358. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483481211212977

- Eagly, A., & Karau, S. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.109.3.573

- Elsaid, A., & Elsaid, E. (2012). Culture and leadership: Comparing Egypt to the GLOBE study of 62 societies. Business and Management Research, 1(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5430/bmr.v1n2p1

- Erkutlu, H., & Tatoglu, E. (2008). The impact of transformational leadership on organizational and leadership effectiveness. Journal of Management Development, 27(7), 708–726. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710810883616

- George, J. (2000). Emotions and leadership: The role of emotional intelligence. Human Relations, 53(8), 1027–1055. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726700538001

- Giorgi, G. (2013). Organizational emotional intelligence: Development of a model. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 21(1), 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/19348831311322506

- Graen, G. B. (2006). In the eye of the beholder: Cross-cultural lesson in leadership from project GLOBE: A response viewed from the third culture bonding (TCB) model of cross-cultural leadership. Academy of Management Perspectives, 20(4), 95–101. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2006.23270309

- Greer, C., & Virick, M. (2008). Diverse succession planning: Lessons from the industry leaders. Human Resource Management, 47(2), 351–367. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20216

- Hage, J., & Posner, B. (2015). Religion, religiosity, and leadership practices: An examination in the Lebanese workplace. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 36(4), 396–412. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-07-2013-0096

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective. Pearson Publishing.

- Hatcher, C. (2003). Refashioning a passionate manager: Gender at work. Gender, Work, & Organization, 10(4), 391–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0432.00203

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A regression-Based Approach (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Howard, S., & Irving, A. (2014). The impact of obstacles defined by developmental antecedents on resilience in leadership formation. Management Research Review, 37(5), 466–478. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-03-2013-0072

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Judge, T., & Piccolo, R. (2004). Transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analytic test of their relative validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(5), 755–768. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.755

- Juhdi, N., Pa’wan, F., & Hansaram, R. (2015). Employers’ experience in managing high potential employees in Malaysia. Journal of Management Development, 34(2), 187–201. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-01-2013-0003

- Kabasakal, H., Dastmalchian, A., Karacay, G., & Bayraktar, S. (2012). Leadership and culture in the MENA region: An analysis of the GLOBE project. Journal of World Business, 47(4), 519–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2012.01.005

- Kerr, R., Garvin, J., Heaton, N., & Boyle, E. (2006). Emotional intelligence and leadership effectiveness. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 27(4), 265–279. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730610666028

- Kidder, D., & Parks, J. (2001). The good soldier: Who is s(he)? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(8), 939–959. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.119

- Kong, F. (2017). The validity of the Wong and Law emotional intelligence scale in a Chinese sample: Tests of measurement invariance and latent mean differences across gender and age. Personality & Individual Differences, 116, 29–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.025

- LaFrance, M., Hecht, M., & Paluck, E. (2003). The contingent smile: A meta-analysis of sex differences in smiling. Psychological Bulletin, 129(2), 305–334. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.305

- Landen, M. (2002). Emotion management: Dabbling in mystery - white witchcraft or black art? Human Resource Development International, 5(4), 507–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678860110057665

- Law, K. S., Wong, C. S., & Song, L. J. (2004). The construct and criterion validity of emotional intelligence and its potential utility for management studies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(3), 483–496. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.3.483

- Leary, M., Reilly, M., & Brown, F. (2009). A study of personality preferences and emotional intelligence. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 30(5), 421–434. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730910968697

- Li, J. (2015). Connecting the dots: Understanding culture differences is the key in customizing HRD research and practice around the world/Editorial. Human Resource Development International, 18(2), 113–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2015.1026551

- Libbrecht, N., Lievens, F., & Schollaert, E. (2010). Measurement equivalence of the Wong and Law emotional intelligence scale across self and other ratings. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 70(6), 1007–1020. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164410378090

- Li, Z., Gupta, B., Loon, M., & Casimir, G. (2016). Combinative aspects of leadership style and emotional intelligence. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 37(1), 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-04-2014-0082

- Li, J., Sun, J. Y., Wang, L., & Ke, J. (2020). Second-generation women entrepreneurs in Chinese family-owned businesses: Motivations, challenges, and opportunities. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 22(2), 124–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422320907043

- Liu, C., Yu, Z., & Tjosvold, D. (2002). Production and people values: Their impact on relationships and leader effectiveness in China. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 23(3), 134–144. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730210424075

- Li, J., & Zahran, M. (2014). Influences of emotional intelligence on transformational leadership and leader-member exchange in Kuwait. International Journal of Human Resources Development and Management, 14(1–3), 74–96. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJHRDM.2014.068084

- Lombardo, M., & Eichinger, R. (2000). High potentials as high learners. Human Resource Management, 39(4), 321–329. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-050X(200024)39:4<321::AID-HRM4>3.0.CO;2-1

- Manning, T., & Robertson, B. (2011). The dynamic leader revisited: 360‐degree assessments of leadership behaviours in different leadership situations. Industrial and Commercial Training, 43(2), 88–97. https://doi.org/10.1108/00197851111108917

- Martínez-Marín, M. D., Martínez, C., & Paterna, C. (2021). Gendered self-concept and gender as predictors of emotional intelligence: A comparison through of age. Current Psychology, 40(9), 4205–4218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00904-z

- McDermott, A., Kidney, R., & Flood, P. (2011). Understanding leader development: Learning from leaders. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 32(4), 358–378. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437731111134643

- Metwally, D. (2014). Transformational leadership and satisfaction of Egyptian academics: The influence of gender. Proceedings of the First Middle East Conference on Global Business, Economics, Finance and Banking in Dubai, UAE, Dubai, D4116, 1–21.

- Michel, S., Pichler, J., & Newness, K. (2014). Integrating leader affect, leader work-family spillover, and leadership. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 35(5), 410–428. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-06-12-0074

- Michinov, E., & Michinov, N. (2022). When emotional intelligence predicts team performance: Further validation of the short version of the Workgroup Emotional Intelligence Profile. Current Psychology, 41(3), 1323–1336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00659-7

- Mihalescu, M., & Niculescu, C. (2007). An extension of the Hermite-Hadamard inequality through subharmonic functions. Glasgow Mathematical Journal, 49(3), 509–514. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0017089507003837

- Miller, D., & Desmarais, S. (2007). Developing your talent to the next level: Five best practices for leadership development. Organization Development Journal, 25(3), 37–43.

- Moon, T., & Morley, M. J. (2010). Emotional intelligence correlates of the four‐factor model of cultural intelligence. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(8), 876–898. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941011089134

- Mousa, M., Massoud, H. K., & Ayoubi, R. M. (2019). Organizational learning, authentic leadership and individual-level resistance to change: A study of Egyptian academics. Management Research, 18(1), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRJIAM-05-2019-0921

- Mousa, M., Massoud, H. K., Ayoubi, R. M., & Puhakka, V. (2020). Barriers of Organizational inclusion: A study among academics in Egyptian public business schools. Human Systems Management, 39(2), 251–263. https://doi.org/10.3233/HSM-190574

- Muppidathi, P., & Krishnan, V. R. (2021). Transformational Leadership and Follower’s Perceived Group Cohesiveness: Mediating Role of Follower’s Karma-yoga. Business Perspectives and Research, 9(2), 269–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/2278533720966065

- Naderi, A. N. (2012). Teachers: Emotional intelligence, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Journal of Workplace Learning, 24(4), 256–269. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665621211223379

- O’Shea, G. P., Foti, R., Hauenstein, N., & Bycio, P. (2009). Are the best leaders both transformational and transactional? A pattern-oriented analysis. Leadership, 5(2), 237–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715009102937

- Posner, B. (2015). An investigation into the leadership practices of volunteer leaders. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 36(7), 885–898. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-03-2014-0061

- Posner, B., & Kouzes, J. (1993). Psychometric properties of the leadership practices inventory-updated. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 53(1), 191–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164493053001021

- Posthumus, J., Bozer, G., & Santora, J. (2016). Implicit assumptions in high potentials recruitment. European Journal of Training & Development, 40(6), 430–445. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-01-2016-0002

- Ramachandaran, S., Krauss, S., Hamzah, A., & Idris, K. (2017). Effectiveness of the use of spiritual intelligence in women academic leadership practice. International Journal of Educational Management, 31(2), 160–178. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-09-2015-0123

- Rice, G. (2011). Leadership Development in Egypt. In D. A. Metcalfe & F. Minoumi (Eds.), Leadership Development in the Middle East (pp. 254–274). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Rice, D. B., & Reed, N. (2021). Supervisor emotional exhaustion and goal-focused leader behavior: The roles of supervisor bottom-line mentality and conscientiousness. Current Psychology, 41(12), 8758–8773. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01349-8

- Riggio, R., Reichard, R., & Brotheridge, C. M. (2008). The emotional and social intelligences of effective leadership. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(2), 169–185. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940810850808

- Rosete, D., & Ciarrochi, J. (2005). Emotional intelligence and its relationship to workplace performance outcomes of leadership effectiveness. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 26(5), 388–399. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730510607871

- Schafer, J. (2010). Effective leaders and leadership in policing: Traits, assessment, development, and expansion. Policing, 33(4), 644–663. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639511011085060

- Schreyer, H., Plouffe, R. A., Wilson, C. A., & Saklofske, D. H. (2021). What makes a leader? Trait emotional intelligence and Dark Tetrad traits predict transformational leadership beyond HEXACO personality factors. Current Psychology, 42 (3), 2077–2086. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01571-4

- Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2013). Research Methods for Business. Wiley.

- Shaaban, S. (2018). The impact of emotional intelligence on effective leadership in the military production factories (MPF) in Egypt. Journal of Business & Retail Management Research, 12(4), 226–239. https://doi.org/10.24052/JBRMR/V12IS04/ART-23

- Shahin, A., & Wright, P. L. (2004). Leadership in the context of culture: An Egyptian perspective. The Leadership and Organizational Journal, 25(6), 499–511. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730410556743

- Shi, X., & Wang, J. (2011). Interpreting Hofstede model and GLOBE model: Which way to go for cross-cultural research? International Journal of Business & Management, 6(5), 93–99. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v6n5p93

- Sidani, Y., & Jamali, D. (2009). The Egyptian worker: Work beliefs and attitudes. Journal of Business Ethics, 92(3), 433–450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0166-1

- Simon, R., & Nath, L. (2004). Gender and emotion in the United States: Do men and women differ in self reports of feelings and expressive behavior? The American Journal of Sociology, 109(5), 1137–1176. https://doi.org/10.1086/382111

- Sivanathan, N., & Cynthia Fekken, G. (2002). Emotional intelligence, moral reasoning and transformational leadership. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 23(4), 198–204. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730210429061

- Stead, V. (2014). The gendered power relations of action learning: A critical analysis of women’s reflections on a leadership development programme. Human Resource Development International, 17(4), 416–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2014.928137

- Sumner, M., Bock, D., & Giamartino, G. (2006). Exploring the linkage between the characteristics of project leaders and project success. Information Systems Management, 23(4), 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1201/1078.10580530/46352.23.4.20060901/95112.6

- Thory, K. (2013). Teaching managers to regulate their emotions better: Insights from emotional intelligence training and work-based application. Human Resource Development International, 16(1), 4–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2012.738473

- Van Rooy, D., & Viswesvaran, C. (2004). Emotional intelligence: A meta-analytic investigation of predictive validity and nomological net. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65(1), 71–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(03)00076-9

- Vecchio, R. (2002). Leadership and gender advantage. The Leadership Quarterly, 13(6), 643–671. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00156-X

- Wong, C. S., & Law, K. S. (2002). The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: An exploratory study. The Leadership Quarterly, 13(3), 243–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00099-1

- Zagorsek, H., Stough, S., & Jaklic, M. (2006). Analysis of the reliability of the leadership practices inventory in the item response theory framework. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 14(2), 180–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2389.2006.00343.x

- Zea, D. G., Sankar, S., & Isna, N. (2020). The impact of emotional intelligence in the military workplace. Human Resource Development International. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2019.1708157

Appendix

Leadership Effectiveness

I am contagiously enthusiastic and positive about future possibilities.

I set a personal example of what I expect of others.

I spend time and energy on making certain that the people I work with adhere to the principles and standards that we have agreed upon.

I follow through on the promises and commitments I make.

I make progress towards goals one step at a time.

I take initiative to overcome obstacles even when outcomes are uncertain.

I am clear about my philosophy of leadership.

I develop cooperative relationships among the people I work with.

I actively listen to diverse points of view.

I treat others with dignity and respect.

I support the decisions people make on their own.

I give people a great deal of freedom and choice in deciding how to do their work.

I ensure that people grow in their jobs by learning new skills and developing themselves.

I praise people for a job well done.

I make a point to let people know about my confidence in their abilities.

I make sure that people are creatively rewarded for their contributions to the success of our projects.

I publicly recognize people who exemplify commitment to shared values.

I find ways to celebrate accomplishments.

I give members of the team lots of appreciation and support for their contributions.

I talk about future trends that will influence how our work gets done.

I describe a compelling image of what our future could be like.

I appeal to others to share an exciting dream of the future.

I show others how their long-term interests can be realized by enlisting in a common vision.

I am contagiously enthusiastic and positive about future possibilities.

I speak with genuine conviction about the higher meaning and purpose of our work.

I seek out challenging opportunities that test my own skills and abilities

I challenge people to try out new and innovative approaches to their work.

I search outside the formal boundaries of my organization for innovative ways to improve what we do.

I ask “what can we learn?” when things do no go as expected.

I make certain we set achievable goals, make concrete plans, and establish measurable milestones for projects and programs we work on.

I experiment and take risks even when there is a chance of failure.