?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The central research question in the area of corporate social responsibility (CSR) has been “Why do some businesses act responsibly, while others do not?” To contribute to answering this fundamental question, the study aimed at empirically determining the influence of stakeholders, which is operationalized as stakeholder pressure, on stakeholder-oriented CSR practices. Because of its generic and versatile nature, this link has been posited as being moderated by organizational culture. For doing so, large manufacturing firms in the Amhara region of Ethiopia, with a sample size of 53, were the target units of analysis. Randomly chosen 473 employees rated the current CSR and organizational culture practices of the firms. Because it is mainly felt by managers, internal stakeholders’ pressure has rather been judged by managers (sampled 253). Consequently, the aggregated process produced data at the organizational level. According to analysis using structural equation modeling, (1) internal stakeholders’ pressure and organizational culture have both been identified as potential factors influencing CSR practices and (2) organizational culture has a moderating role in the relationship between internal stakeholders’ pressure and CSR practices. Notwithstanding its limitations, the study has provided useful insights into both the theory and practice of CSR. Similar studies with tailored designs are encouraged for future research.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Examining business and society'srelationships using the corporate social responsibility (CSR) lens has become almost a de facto approach in the field of inquiry. The research field would be elevated to the ladder of public (national/international) issues for businesses affect the lives of every global citizen. The reciprocal effect also demands attention from the viewpoint of business managers. In Ethiopia, as well, businesses continue to impact the quality of life, employment, poverty, government revenue, and so on. Nonetheless, there are concerns about whether or not businesses are indeed discharging the set of ‘responsibilities’ owed to them by society. On the flip side of the inquiry, there are also concerns about whether or not society guarantees legitimacy to businesses. This particular study has found itself in the first line of inquiry: examining the extent to which selected businesses in the country of Ethiopia, particularly in the Amhara region of the country, have been responsible to society (which has been expressed in terms of stakeholders); and indicating the factors attributing to that level of CSR performance. This piece of knowledge would be useful for both the businesses to see their track and to the society to lift up or otherwise its legitimacy. Apart from practical contribution, the study would contribute to the theory of business and society in its insight into multi-stakeholder approach.

1. Introduction

For businesses affect the lives of every global citizen (Sexty, Citation2017), the responsibilities (or obligations) of business to “society” in general (Bowen, Citation1953; Frederick, Citation1960), or to “stakeholders” in particular (E. R. Freeman, Citation1984), has been a concern of academic inquiry and practice for more than a century (Amin-Chaudhry, Citation2016). Because the central theme has been the nature of the relationship that ought to exist between business as an institution and society (Klonoski, Citation1991; Preston, Citation1975), generic nomenclatures suggesting such a relationship and the study of the same have been in place (Wood, Citation2010; Wood & Cochran, Citation1992). Though there exist subtle differences in the notions those nomenclatures would like to stress, leading pioneers of the field (e.g. Buchholz & Rosenthal, Citation1997; Carroll, Citation2015; Lee, Citation2008; Wood, Citation2010) have consistently adopted the nomenclature of “Business and Society” (hereafter B&S), and hence this work proceeds by adopting the same. With the development of the corporate form of business, this link has been primarily approached via the concept of social responsibility (CSR; Carroll, Citation1979, Citation2015).

The works on the B&S field—both the academics and the practice—have targeted, explicitly or implicitly, at answering one or more of the five fundamental inquiry questions of the field of B&S in general and CSR in particular (e.g. Buchholz & Rosenthal, Citation1997; Schwartz & Carroll, Citation2008): (1) What exactly are the responsibilities of business to society? (2) Should businesses engage in social responsibilities at all and the first place? Why? (3) To whom businesses are responsible? (4) How would businesses’ social responsibilities be measured? (5) Why do some businesses act responsibly while others do not?

This particular work has immersed itself in contributing to the fifth fundamental inquiry. A decision to focus on this fundamental question has been as per trend changes, repeated research calls on the same (Aguilera et al., Citation2007; Aguinis & Glavas, Citation2012; Matten & Moon, Citation2008; Smith, Citation2003, p. 55) and as a result of practice in the country, Ethiopia. In turn, answering this fundamental question requires two aspects: (1) evaluating the CSR practice of businesses and (2) searching potential determinants accountable for that level of CSR performance. A delineation of these two aspects is made and discussed next.

Towards the first theme, a systematic literature review that focused on the academic inquiry of the practice of CSR in Ethiopia has been made. The literature analysis has revealed that especially manufacturing businesses call for more inquiry as the businesses are exposed to numerous irresponsible activities. Potluri and Temesgen (Citation2008), for example, have confirmed that about 69% of employees, 71% of customers, and 75% of the public were displeased about the CSR practices of the companies. More recent studies on the same business segment do not convey an improved notion of CSR practices (e.g. Gemechu et al., Citation2020; Mulugeta & Muhammednur, Citation2020). When the works are clustered state (regional state) wise to see where the works have been done, only a handful of papers resided in Amhara Regional State: on manufacturing (Eyasu et al., Citation2020; Hailu & Rao, Citation2016) on Hotels (Fentaw, Citation2016; Hailu & Rao, Citation2016), on Banks (Eshetu, Citation2019), on Merchandise businesses (Uvaneswaran et al., Citation2019). The practice of CSR, however, is not different from the nationwide picture. Because the review has indicated that a focus on “large manufacturing firms” require priority, a decision has been made to focus on the same.

Turning to the second aspect—determinants of CSR practice—, several conceptual and empirical kinds of research have been devoted to finding out determinants and moderating conditions of CSR practice (Aguinis & Glavas, Citation2012). In line with Bowen’s implicit early conceptualization, determinants of CSR practice would be clustered into institutional (macro-level), organizational (Meso level), and individual (micro-level) predictors (Aguinis & Glavas, Citation2012; Wood, Citation2010). This particular study has given attention to the organizational level (Meso level) determinants of CSR practice because “relative importance studies”, also called “variance decomposition” studies (Adner & Helfat, Citation2003; Crossland & Hambrick, Citation2007), have shown that organizational effects attribute to the largest part to CSR practice variability. Prior empirical literature in the field of CSR has reported varying amounts of variation attributable to the firm effect: about 70 % (Ioannou & Serafeim, Citation2012), 52 % (Mazzei et al., Citation2015), and about 75% (Orlitzky et al., Citation2017). In other words, CSR practice would be enhanced in paramount if the organizational level atmosphere is made conducive for the same. It means the investigation of organizational-level variables still warrants much attention of inquiry.

Among several possible organizational level determinants (Aguinis & Glavas, Citation2019; Mattingly, Citation2017), two of them—stakeholder pressure and organizational culture—are picked in this particular work. In modeling CSR practice determinants, the “influencer part” (the “can affect” strand of Freeman’s definition’) has to be emphasized. This influence runs in the literature of CSR with the labeling of “stakeholder pressure” (Fassin, Citation2009; Helmig et al., Citation2016). Restricting the stakeholder groups and types to internal stakeholders (employees and owners), only “internal stakeholders” pressure has been the concern here. Taking this variable is worthy of value for good reason. A complete track of stakeholder theory should embed both sides: the “can affect” and “affected by” sides (E. R. Freeman, Citation1984). Whereas prior literature takes either of the two (rather than both of them), in a single inquiry, here both sides are embedded; stakeholder pressure (independent variable) represents the “can effect” strand, and “stakeholder-oriented” CSR practice highlights the “affected by” side of the function (emphasis added).

Organizational culture has been the second organizational-level variable picked. Because of its versatility (Cameron & Quinn, Citation2011) and suggestions to give attention to it (Orlitzky et al., Citation2017), organizational culture is maintained as an inclusive predicting variable of CSR practice (Athanasopoulou & Selsky, Citation2015; Jamali & Karam, Citation2018). Jamali and Karam (Citation2018, p. 49) have been caught saying “it is also important to consider how the organizational culture [—-] influences CSR adoption in developing countries”. As noticed from the systematic review, the domestic literature is deprived of such empirical evidence (see Tsegaw & Yohannes, Citation2019 for an exception). In the same vein, moderation studies have almost ignored the moderation effect of aggregate organizational culture in most links, giving more emphasis to the moderation effect of particular organizational culture types. Thus, besides its direct predictable power, organizational culture has been also claimed as a potential moderation condition in CSR links (e.g. Chu et al., Citation2018; Ogola & Mària, Citation2020). In response to this gap, it is posited here that organizational culture would moderate internal stakeholders’ pressure-CSR practice link.

As a consequence, bringing empirical evidence for the effect of these two huge organizational-level variables would be a lot for ameliorating CSR malpractices. We thus conceived a model testing worthy for both theory and practice. Theoretically, the result provided additional evidence for the theoretical propositions of cultural and stakeholder theories. The practice harvests much more; managers would enhance CSR practice by gearing their attention to improving organization culture and responding to stakeholder pressure.

In summary, the present study has gone for analysis of organizational level determinants of CSR practice. In more specific terms, the study has got three-fold objectives: (1) to find out the effect of internal stakeholders’ pressure on CSR practice, (2) to determine the influence of (aggregate) organizational culture on CSR practice, and (3) to ascertain the moderating role of organizational culture in the relationship between internal stakeholders’ pressure and CSR practice.

The rest of the paper is organized as such. In section 2, the underlying theoretical works are highlighted, hypotheses have been derived and a conceptual framework finally has been crafted. Methods employed in the study are presented in section 3. Results and discussion have become the concern of section 4. Following this, Contributions or implications of the findings have been highlighted in section 5. Section 6 concludes the work by outlining the takeaway findings, cautionary limitations, and future insights for further study.

2. Theory and hypotheses

2.1. Multi-stakeholder theory of CSR

The responsibility-based conceptualization of CSR, which has been there until, at least, E. R. Freeman’s (Citation1984) seminal work, has been later supplanted and highly cemented with stakeholder theory (e.g. Carroll, Citation1991; Clarkson, Citation1995; Wood, Citation2010; Wood & Jones, Citation1995). Even though it seems that the project of integrating stakeholder theory into the conceptualization and measurement of CSR, at least more formally, would be attributed to have been initiated by Carroll (Citation1991), many other notable works have cited stakeholder theory as a safe and comfortable way out for exercising CSR initiative (Clarkson, Citation1995; Sirsly, Citation2009; Wood & Jones, Citation1995). Carroll begins by welcoming the stakeholder approach to the CSR camp: “there is a natural fit between the idea of corporate social responsibility and an organization’s stakeholders” (Carroll, Citation1991, p. 43). Wood and Jones (Citation1995) asserted that “CSP studies must be integrated with stakeholder theory” (p. 229).

Regarding the number of stakeholder groups, a comfortable answer would be obtained from the notion of the “multi-stakeholder approach” (Freeman et al., Citation2007). And exactly to the minimum number, several works quote at least six primary stakeholder groups (customers, employees, communities, suppliers, owners, and natural environment) as constituents (Carroll, Citation2000; El Akremi et al., Citation2018; Freeman et al., Citation2007). Accordingly, CSR is operationalized to mean the various responsibilities (economical, legal ethical, and discretionary) of these six stakeholder groups (Carroll, Citation2000; El Akremi et al., Citation2018; Freeman et al., Citation2007).

2.2. Theoretical frameworks for the independent and control variables

Stakeholder Theory and Stakeholder Pressure. To operationalize the influence of stakeholders on the practice of stakeholder-based CSR, the term “stakeholder pressure” has been in place in the concerned literature (Fassin, Citation2009; Helmig et al., Citation2016; Kassinis & Vafeas, Citation2006). Now, the question becomes how stakeholder pressure would be operationalized and measured. To the point of purpose at hand, a plausible answer comes from the theory of stakeholder identification and salience (TSIS) pioneered by Mitchell and colleagues (Mitchell et al., Citation1997).

Mitchell et al. (Citation1997) have posited that no single stakeholder attribute is sufficient to answer the central question of “who and what really counts” in the management-stakeholder relationship, but rather “relative absence or presence of all or some of the attributes of power, legitimacy, and/or urgency” (p.864) is required. A powerful stakeholder possesses the ability “to bring about the outcomes they desire” by exercising one or more of power sources: coercive power (inherited from force base), utilitarian power (based on material and/or financial rewards and/or restraints) and normative power (characterized by symbolic resources). A legitimate stakeholder is described—based on Suchman’s (Citation1995) legitimacy theory—as one possessing a claim believed to be “desirable, proper, or appropriate” given agreed-upon societal “norms, values, beliefs, and definitions” (Mitchell et al., Citation1997, p. 865). Finally, the urgency of stakeholder claims is judged by “the degree to which stakeholder claims call for immediate attention” (Mitchell et al., Citation1997, p. 867).

Employing these three attributes as dimensions of stakeholder pressure (Agle et al., Citation1999; Mitchell et al., Citation1997) and internal stakeholder groups (employees and owners), internal stakeholders’ pressure (ISP) has been operationally conceived.

Cultural theory and Organizational culture. Athanasopoulou and Selsky (Citation2015) have chosen the cultural perspective at the organizational level—operationalized through organizational culture—as a determinant of the responsible behavior of firms. This has got wide literature support (e.Boesso & Kumar, Citation2016; Jamali & Karam, Citation2018; Jones et al., Citation2007). Accordingly, the study has taken organization culture as both a stand-alone predictor variable and a moderating variable for the work orientation-CSR practice link (M. Lee & Kim, Citation2017; Ogola & Mària, Citation2020). To affirm this, the study eschewed the sociological (specifically, the interpretive strand) view (Cameron & Ettington, Citation1988), Cameron and Quinn’s (Citation2011) operationalization, and the quantitative approach to organizational culture. The prevailing OC profiles/dimensions, rather than the desired ones, have been the analysis issue.

Control Variables (CVs) and CSR Practice. Scrutiny of the literature has suggested that three firm characteristics (firm size, firm age, and firm ownership) have been the primary variables conceived and applied in explaining the CSR behavior of firms (Dong et al., Citation2014; Galbreath, Citation2010; Oh et al., Citation2017). Accordingly, these variables have been set as control variables (CVs) in the present inquiry. A multitude of theories such as agency theory, institutional theory, and slack resources theory become underlying theories for conceiving and applying this range of drivers of CSR behavior at the organizational level (e.g. D’Amato & Falivena, Citation2019; Faller & Zu Knyphausen-Aufseß, Citation2016).

2.3. Hypotheses

2.3.1. Internal stakeholders’ pressure and CSR practice

Conceptually, it is posited that stakeholder pressure potentially affects the socially responsible behavior of organizations; the basic thesis entails that more salient stakeholders tend to exert pressure on organizational behaviors (E. R. Freeman, Citation1984; Kassinis & Vafeas, Citation2006), particularly toward the socially responsible behavior of businesses (e.g. Barnett, Citation2007).

Empirically, a large segment of the studies has brought support to the conceptual proposition: a positive relationship between stakeholder pressure and CSR practices (e.g. Jha & Aggrawal, Citation2020; Kassinis & Vafeas, Citation2006). On the contrary, some studies have revealed either no (e.g. Agle et al., Citation1999; Helmig et al., Citation2016) or negative effects (Bar-Haim & Karassin, Citation2018) on some aspects of CSR. The domestic literature has also carried mixed results (Eyasu et al., Citation2020; Mulugeta & Muhammednur, Citation2020; Tsegaw & Yohannes, Citation2019).

Nonetheless, consistent with the conceptual literature that states the importance of stakeholder pressure on CSR practice and most of the empirical studies that support the direct positive relationship, the first hypothesis of the inquiry is stated as follows.

H1.

Internal stakeholders’ pressure results in a significant positive effect on CSR practices.

2.3.2. Organizational Culture (OC) and CSR practice

Both theoretical (e.g., Athanasopoulou & Selsky, Citation2015; Maon et al., Citation2010) and review works (e.g. Jamali & Karam, Citation2018) consistently present OC as a potential antecedent of responsible social behavior of organizations.

Employing Cameron and Quinn’s (Citation2011) organizational culture model, the empirical studies failed to cement generalizations. Both positive and no links are evident in the literature. In one family of empirical studies—the influence of aggregate OC (cultural type) on aggregate- (Karassin & Bar-Haim, Citation2016), decomposed- or specific stakeholder-based CSR (González-Rodríguez et al., Citation2019; Karassin & Bar-Haim, Citation2019)—, it has been reported that aggregate OC (cultural type) brings enhancement of socially responsible behavior of organizations; in another set, studies have revealed no link. Bar-Haim and Karassin (Citation2018), for example, have found no link between OC and aggregate CSR and employee-oriented CSR.

Relying on this literature, both conceptual and empirical that report a positive relationship, it is here posited that the prevailing dominant cultural type potentially contributes to the enhancement of socially responsible behavior. Accordingly, the second hypothesis of the inquiry is stated as:

H2.

Organizational culture exhibits a significant positive effect on CSR practices.

2.3.3. Organizational culture as a moderator

Besides the direct effect, it would put on CSR practice, the inclusive and pervasiveness nature of organizational culture would lead to playing, also, moderating effect. Organizational culture literature provides support for this proposition (O’Reilly et al., Citation1991; Ravasi & Schulz, Citation2006). The moderating effect of organizational culture would also explain the inconclusive findings about the direct effect of stakeholder pressure on CSR practice (Baron & Kenny, Citation1986, p. 1178).

In the CSR empirical literature, however, organizational culture has shown mixed results (positive, negative, and no) concerning its moderation effect (Chu et al., Citation2018; Dai et al., Citation2018). Studies that have employed the OCAI of Cameron and Quinn (Citation2011) to determine the moderation effect of each of the four cultural types in CSR inquiry (e.g. M. Lee & Kim, Citation2017), too, have carried out inconclusive findings. Nonetheless, moderation studies have almost ignored the moderation effect of aggregate OC in most links, giving emphasis rather to the more particular type of OC types.

Drawing on the conceptual propositions and empirical results on particular OC types, here it is posited that the dominant OC manifested in organizations moderates the relationship between internal stakeholders’ pressure and CSR practices. Thus, the moderated-based hypothesis is formulated as such.

H3.

The more established organizational culture exists, the weaker the relationship between internal stakeholders’ pressure and CSR practice will be.

2.3.4. Control Variables (CVs) and CSR practice

Scrutiny of the literature has suggested that three firm characteristics (firm size, firm age, and firm ownership) have been the primary variables conceived and applied in explaining the CSR behavior of firms (e.g. Dong et al., Citation2014; Galbreath, Citation2010; Oh et al., Citation2017). Accordingly, these variables have been set as control variables (CVs) in the present inquiry. A multitude of theories such as agency theory, institutional theory, and slack resources theory become underlying theories for conceiving and applying this range of drivers of CSR behavior at the organizational level (e.g. D’Amato & Falivena, Citation2019; Faller & Zu Knyphausen-Aufseß, Citation2016).

Formulating and maintaining a separate hypothesis for the relationship between CVs and the dependent variable is due to the related literature on CVs (Becker et al., Citation2016). Hence, the accompanying hypothesis has been forwarded.

H4.

Each of the organizational level characteristics (large size, old age, and public ownership) exerts a significant positive effect on CSR practice.

2.4. The conceptual framework of the study

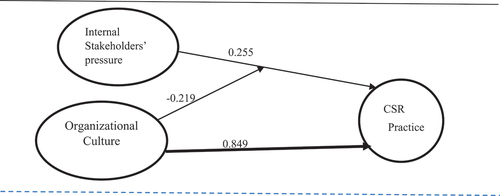

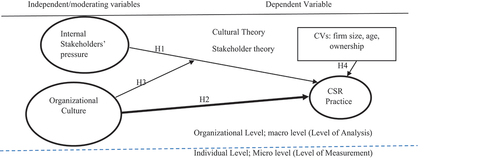

Grounded on the underlying theories, conceptual arguments, empirical reviews, and the hypotheses developed, the following conceptual framework (Figure ) has been developed.

Figure 1. The conceptual framework which shows the study variables and the research hypotheses.

3. Methods

3.1. Variables and measurement instruments

Four types of variables (focal predictor or independent variable, moderating variable, dependent variable, and Control variables) all situated at the organizational level have been operationalized. Primary data have been collected from September to December 2021. In each of the 53 firms, the first author has had the in-person drop-and-pick technique of administering the questionnaires. Secondary data on the nature of firms in the region had been rather obtained in September 2021 at the time of proposal craft. We have appended the self-administered questionnaire employed for the survey (Supplementary Material 1) and the list of companies that participated in the study (Supplementary Material 2).

3.1.1. Internal Stakeholders’ Pressure (ISP)

Operationally, it is meant the level of exertion by employees and/or shareholders in their quest to meet their expectations and demands and it is perceived by businesses as possessing one or more of the attributes of legitimacy, power, and urgency (Mitchell et al., Citation1997). Both groups of stakeholders pressure were measured by three items representing three stakeholder attributes: power, legitimacy, and urgency (Agle et al., Citation1999; Mishra & Suar, Citation2010). Managers were asked to rate the level of pressure the stakeholder group exerts on the company’s policies, decisions, and plans, with these anchors: 5= very strong pressure; 4 = strong pressure; 3= medium pressure; 2= low pressure; 1= very low pressure. The overall reliability coefficient has been 0.94.

3.1.2. Organizational Culture (OC)

It is meant to mean the taken-for-granted values, underlying assumptions, expectations, and definitions that characterize organizations and their members (Cameron & Quinn, Citation2011). By adopting the 24-item organizational culture assessment instrument (OCAI), employees have rated the current organizational culture of their employing organization with the nominations of 5=strongly agree, 4=moderately agree, 3=slightly agree/disagree, 2=moderately disagree, and 1=strongly disagree. The measurement scale read a coefficient alpha value of 0.96.

3.1.3. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Practice

CSR has been operationalized as “the various economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary responsibilities that businesses owe towards the six stakeholder groups of employees, customers, suppliers, local community, natural environment and owners” (Carroll, Citation1991, Citation2000; El Akremi et al., Citation2018). For its measurement, no consensus is observed in the literature; a category of five measurement schemes is evident: content analysis, reputation ratings, social auditing databases, proxy measures, and surveys (Orlitzky et al., Citation2003; Q. Wang et al., Citation2015). The first four schemes were found infeasible for various reasons. Thus, the residual method—survey— better served the inquiring agenda of this particular study. By taking employees as a representative stakeholder group, they were asked to rate the extent to which each stakeholder issue explained organizational current CSR practices, with anchors of 5 “To a great extent”, 4 “to moderately large extent”, 3 “to some extent”, 2 “a little extent”, and 1 “Not at all”. As to the reliability, the coefficient alpha has been so high (0.95) that the scale achieved remarkable reliability.

3.1.4. Control Variables (CVs)

The selected organizational level CVs were firm size, firm age, and firm ownership, which were operationalized as the number of employees (size); Private or public (ownership); the number of years the firm has been in operation since its operation, excluding the project period (age). Data have been fetched from Secondary sources.

3.2. Sampling

3.2.1. Target Population

The inquiry has targeted large manufacturing firms in Amhara Regional state, Ethiopia. As per the updated database provided by the Investment and Industry Bureau of the region (2021), this group of firms numbered 198. This number constituted the population size at the organizational level. Employees and managers of the target large manufacturing firms composed the target population at the individual level.

3.2.2. Sample size

Sample sizes are determined separately at the organizational and individual levels. At the organizational level, Hair et al. (Citation2009) have argued that if some conditions are met, or found “ideal conditions”, “sample sizes as small as 50” provide “valid and stable results” (p.636). Accordingly, the sample size of 53 organizations met the minimum sample size requirement for the proposed model. Furthermore, several works suggest that groups (organizations) as small as 50 would achieve reasonably good statistical results (Bell et al., Citation2008; Hox et al., Citation2010).

At the individual level, technical considerations (number of parameters to be estimated, power of the test, estimation models, number of latent and measured variables, possible missing data, normality; Hair et al., Citation2009) have been all taken into account. The study, for example, involves three latent variables (two exogenous and one endogenous variable) with three control variables. Hair et al. (Citation2009) quote that for more complex models (models with more than seven constructs), a minimum sample size ought to be 500. As to the sample size of employees, considering all these, a sample size of 500 (i.e., the minimum sample size, which is 500, for complex SEM models; Hair et al., Citation2009) employees has been set. Another 100 has been reserved for contingencies for possible omissions, missing, reluctance, and so on. A proportional sample size, then, is allotted for each of the sample companies. Taking an optimal span of management, a sample of 6 managers presumed in each firm, which yielded a sample of 318 managers. This time, a contingency of 50 has been set.

On the net, 253 managers and 473 employees residing in 53 firms participated in the inquiry. The survey has achieved a response rate of about 69 percent (253/368) and 79 percent (473/600), respectively, for the manager and employee samples.

Sampling Technique. A multistage sample has been employed. Large manufacturing firms were selected first. Second, it has been followed by at least 5 years of operation’ criteria (Godfrey & Hatch, Citation2007; Mattingly, Citation2017; Orlitzky et al., Citation2017), which yielded the sample companies (53). As a third stage, a simple random sampling has been applied to select target respondent managers and employees in each of the sample companies. A proportional sample has been allotted for each of the companies for both manager and employee samples.

3.3. Data quality and management methods

We employed several data management methods taking from the best-practice suggestions of the relevant literature: pre-testing Procedures (Campanelli, Citation2008), expectation maximization (EM) missing data technique (Enders, Citation2003, p. 335), subset-item-parcel (Bandalos, Citation2002; J. Wang & Wang, Citation2012), aggregation test (LeBreton & Senter, Citation2008), outlier detection techniques (Aguinis et al., Citation2013), Common Method bias (CMB; Podsakoff et al., Citation2003), grand mean centering (Enders & Tofighi, Citation2007, p. 135), and licensed Mplus software (Mplus 8.8), with a license number of STBC80008122, and SPSS v. 26. The set of parcels used and their labeling is depicted on Table .

Table 1. Parcels, latent variables, and constituent items for the measurement models

3.4. Analytical procedure adopted

Concerning the specific (single-level) statistical analysis package, structural Equation Modeling (SEM) is the chosen general analytical tool for the basic reason that the three constructs involved are all latent constructs (Hair et al., Citation2009). SEM is known for treating two models: the measurement model (for validation of measurement variables) and the structural model (for testing the structural relationship of constructs). We have got both of these models and the results are presented in the next section (section 4). Nonetheless, three aspects of the proposed models call for justifications: aggregation of the individual-level data, “the small sample size”, and the structural analysis by the “moderated regression” technique.

3.4.1. Justification for Aggregation Procedure

The hypotheses stated here correspond to Snijders and Bosker’s (Citation2012, p. 29) “macro-level propositions” type of multilevel models. There is “nothing wrong” in using aggregation procedure and group means in cases where the interest is on “macro level propositions” (Snijders & Bosker, Citation2012, p. 35) or “when a researcher has both a dependent and independent variable consisting of higher-level variance” with “sufficient evidence to support the aggregation” (Hofmann, Citation2002, p. 262). Besides this set of justifications, the data set has been subject to a statistical aggregation test.

Having justified the procedure, organizational level data has been set up for each of the three variables of the study: organizational level CSR practice has been the mean of 34 items (or six parcels), organizational culture formed with the mean of 24 items (or 4 Parcels) and internal stakeholders’ pressure established with the mean of 6 items (or 3 parcels). Data aggregation and merging have been handled with SPSS v26.

3.4.2. SEM with small samples

Of those methods for handling SEM with a small sample size (Smid & Rosseel, Citation2020; Van de Schoot & Mulugeta & Muhammednur, Citation2020; Veen & Egberts, Citation2020), Factor Score Regression (FSR) has been picked for it (1) provides similar results with other common method, two-step modeling (Smid & Rosseel, Citation2020), (2) and it is, perhaps, one of the common moderation analysis technique.

Factor Score Regression (FSR) modeling calls for running three distinct steps. In step 1, a measurement model is fitted (Gemechu et al., Citation2020, p. 230) and this yields Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). Whereas in step 2, factor scores are determined for each of the latent variables, step 3 involves estimating the structural part of the model (Gemechu et al., Citation2020, p. 231). When taken together, the measurement model (Confirmatory Factor Analysis) and the structural model (Moderated Hierarchical Multiple Regression) constitute the SEM procedure.

3.4.3. Moderated Hierarchical Multiple Regression (MHMR)

This analytical strategy has been found more appropriate for these reasons: (1) it allows for predictor variables (control variables, independent variables, and moderating variables) to be entered in a “pre-specified sequence” to easily depict the incremental change in R2 associated with the variable entered at that particular step (Cohen et al., Citation2003, p. 158), (2) specifically for moderation, “it [hierarchical regression] is necessary to know the increment in R2 due to the interaction” (Dawson, Citation2014, p. 13), and (3) it has become an almost standard tool in moderation studies in management research in general and CSR studies in particular (e.g. Chu et al., Citation2018; Dai et al., Citation2018).

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Descriptive analysis

Descriptive statistics and correlations are captured in Table . We followed mean interpretation and cut-off values stipulated by Pornel et al. (Citation2011), and Pornel and Saldaña (Citation2013). The correlation results read consistent with the theoretical propositions with the two variables, respectively, having correlation coefficients r = 0.89 (p < 0.01) and r = 0.28 (p < 0.05)—see Table . Organizational culture and internal stakeholders’ pressure have not established a significant correlation between themselves (see Table ). The correlations connote that nomological validity has been verified. All the control variables have formed a very negligible correlation with the study variables (see Table ).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and correlations for the study variables

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

In this part of the analysis, three aspects of the measurement model (model fit, validity and reliability, and assumptions) are dealt with. The analysis corresponds to step 1 of the FSR analytical procedure. Validity and reliability statistics are summarized in Table and Figure .

Table 3. Validity and reliability measures for the measurement model

Model fit and Re specifications. The measurement model resulted goodness-of-fit figures of X2 = 74.695 with p = 0.08, RMSEA = 0.07, CFI = 0.979, TLI = 0.972, and SRMR = 0.041 (Hair et al., Citation2009; Hu & Bentler, Citation1999).

Model Assumptions. The observed variables (parcels) have demonstrated kurtosis values that range from −0.323 to 1.032, which are near zero. Hence, univariate normality has been met. “The little difference” between the model fit values done using the ML and MLM estimators provided great confidence for the observance of multivariate normality (Byrne, Citation2012, p. 101). Regression—curve estimation test (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2013, p. 689) has revealed that linearity would be a more plausible relationship. There has been no concern about multi-collinearity in the relationship between the two predictor variables.

Validity and Reliability Tests. All the measures agreed and ensured convergent validity with loadings that range from 0.851 to 0.975 (all being statistically significant), communalities from 0.724 to 0.951, and AVE values of 0.759 (CSR), 0.863 for OC and 0.849 for ISP (See Table ). Using Fornell and Larcker’s (Citation1981) criterion, there exists no issue of discriminant validity on the relationship between CSR and ISP and OC and ISP (See Table ). By adopting the procedures of El Akremi et al. (Citation2018) and Tracey and Tews (Citation2005), although CSR and OC are highly related (r = 0.889; Table ), we discovered distinct constructs. The corresponding CR values—0.949, 0.963, and 0.944 (See Table )—respectively, for the constructs of CSR, OC, and ISP are all very far from the threshold value of a least 0.60/070 (Hair et al., Citation2009). The coefficient alpha value also reads a very close figure to the respective CR value of the construct (See Table ).

4.3. Hypothesis tests and discussion

This part of the analysis corresponds to steps 2 and 3 of the FSR analytical procedure. Having estimated mean scores for the latent variables (step 2), at step 3, moderated hierarchical multiple regression (MHMR; Cortina, Citation1993) best handled the purpose at hand. For moderation analysis, the research follows the guidelines laid down by the relevant literature (Aiken & West, Citation1991; Baron & Kenny, Citation1986; Cohen et al., Citation2003; Dawson, Citation2014; Jose, Citation2013). Particularly, the best-practice recommendations sketched by Dawson (Citation2014) have been heavily adopted.

4.3.1. Order of entrance and Models

Concerning the order of entrance of the variables, control variables (CVs) have been entered first for they have been justified to be “theoretically meaningful CVs” (Carlson & Wu, Citation2012, p. 432), and they are regarded as candidates to be first entrants (Cohen et al., Citation2003; Petrocelli, Citation2003). Hence, the analysis has been based on three models: the independent variable model (model 1), moderating variable model (model 2), and the moderation/interaction model, or full model, (model 3). The mathematical expression of the models is provided next.

Model 1

Model 2

Model 3

Where

CSRg= Corporate Social Responsibility practice of a certain group (organization), g; Bo= grand mean value of CSR practice; intercept; B1=regression coefficient showing a main effect of internal stakeholders’ pressure; B2= regression coefficient showing a main effect of (aggregate) organizational culture; B3= regression coefficient showing interaction/moderation effect of (aggregate) OC; ISP= Internal stakeholders’ pressure; OC= Organizational culture; and = interaction term formed by the product of grand mean centered ISP and (aggregate) OC.

4.3.2. Hypothesis testing techniques

For both the main and interaction effects, three test procedures have been applied: (1) Null Hypothesis significance test (NHST) for regression coefficients (Dawson, Citation2014; Kline, Citation2004), (2) significance test of incremental R2, ΔR2 (Dawson, Citation2014), and (3) effect size (ES) measure of Chen’s (Cohen, Citation1988; Ellis, Citation2010; Kline, Citation2004). Chen’s

is computed as

, wherein

represents ‘proportion of variance of that source [variable], and

“proportion of variance” associated with error (Cohen, Citation1988, p. 410). For the interaction term, however, it is calculated as

, wherein

denotes “variance explained by the model including the interaction term, and

the variance explained by the model excluding the interaction term” (Dawson, Citation2014, p. 14). Then, the test results are summarized on Table and Figure .

Table 4. Moderated regression estimations

4.3.3. Effect of control variables

The inclusion of CVs at step 1 (Carlson & Wu, Citation2012, p. 432; Cohen et al., Citation2003; Petrocelli, Citation2003) assured that none of the variables have been a potential predictor of CSR practice (result not included). For the final analysis, therefore, CVs have been dropped. Furthermore, Becker (Citation2005, p. 286) eschews the omission of CVs when results with and without CVs do not differ, which has been the real case in this inquiry. All in all, hypotheses relating CVs and CSR practice (H4) lacked empirical evidence.

4.3.4. Main effects of internal stakeholders’ pressure-CSR practice link

The independent variable (internal stakeholders’ pressure; B = 0.255, t = 2.07, SE = 0.124, p < 0.05; see Table ) has established a significant positive relationship with CSR practice. Model 1 has achieved good model fit (F = 4.268, p < 0.05; see Table ). Regarding the effect of bringing this variable into the model, entering internal stakeholders’ pressure has brought an incremental R2 of 7.7% (model 1), which tells us that internal stakeholders’ pressure alone accounts for a 7.7% variation in CSR practice. The incremental change (ΔR2) further achieved significant F values (ΔF = 4.27, with p < 0.05; see Table ). Applying Cohen’s formula, medium ES of 0.08 has been obtained (Cohen, Citation1988). All tests have brought support for the hypothesis stating the significant positive effect of internal stakeholders’ pressure on CSR practice; thus, H1 has enjoyed sufficient empirical support. This result has been found consistent with theoretical propositions and prior empirical literature.

The influence of stakeholders on organizational achievement, now, on the practice of stakeholder-based CSR, has been operationalized by the tripartite stakeholder attributes of power, legitimacy, and urgency (Agle et al., Citation1999; Laplume et al., Citation2008; Mitchell et al., Citation1997; Wood et al., Citation2018) proposing that stakeholder group possessing two or more of these dimensions exert medium to strong “pressure” on organizational practices. By taking two internal primary stakeholder groups (employees and owners) and the three stakeholder attributes (power, legitimacy, and urgency) for both stakeholder groups, the result coincides with the theory and brings another empirical support for the theory.

The prior empirical literature has gone for a similar link, though substantial difference exists in the conceptualization and measurement of the two constructs. Based on the measure of stakeholder pressure and CSR applied, though both negative (Bar-Haim & Karassin, Citation2018) and zero (Agle et al., Citation1999; Chu et al., Citation2018; Helmig et al., Citation2016; Hernández-Arzaba et al., Citation2022) relationships have been reported in the prior literature, the result is consistent with the segment of literature that have taken aggregate CSR measure and reported positive link for the relationship between the variables (e.g. Adomako & Tran, Citation2022; Jha & Aggrawal, Citation2020; Mzembe & Meaton, Citation2014; H. Tian & Tian, Citation2021; Q. Tian et al., Citation2015; Valiente et al., Citation2012; Ying et al., Citation2022; Yu & Choi, Citation2016). Besides consistency with the global literature, the result also provides support for the domestic empirical literature (Eyasu et al., Citation2020; Mulugeta & Muhammednur, Citation2020).

4.3.5. Main effects of organizational culture-CSR practice link

As it can be read from Table , the test results on OC-CSR practice link (overall model fit: R2 = 0.821, F = 115.040, p < 0.05; incremental R2 = 0.744, ΔF = 208.45, p < 0.05; B = 0.849, t = 14.44, SE = 0.059, p < 0.05; Cohen’s

have revealed that OC indeed exerts a significant positive effect on the CSR practice of organizations. Thus, H2 has been fully supported by empirical evidence. With no surprise, the result overlaps with both the theoretical and prior empirical literature.

Theoretical works (e.g., Athanasopoulou & Selsky, Citation2015; Maon et al., Citation2010; Swanson, Citation1999) posit that OC has great potential to determine the social behavior of organizations. The study indicates that, as posited in the theoretical works, as organizational culture becomes “stakeholder culture” (Jones et al., Citation2007), tends to be “cultural embedment” (Maon et al., Citation2010), cultivates “engagement/integration” (Slavova, Citation2015), CSR practice would become better. The result witnesses this by yielding a significant positive (unstandardized) regression coefficient (B = 0.849, p < 0.05; see Table ), significant large correlation coefficient (r = 0.889, p < 0.01; Table ), and large effect size (2.91; Cohen, Citation1988; see Table ).

The result also matches with prior empirical literature that went for the link of aggregate OC-CSR behavior (González-Rodríguez et al., Citation2019; Karassin & Bar-Haim, Citation2019; Shanak et al., Citation2020; Wan et al., Citation2020). Using the OCAI measurement scheme, prior works have found that aggregate OC established a significant positive relationship with either aggregate CSR (Karassin & Bar-Haim, Citation2016) or CSR geared towards a specific stakeholder group (customer-, employee-, and local community-oriented CSR: González-Rodríguez et al., Citation2019; environment-oriented CSR:; González-Rodríguez et al., Citation2019; Karassin & Bar-Haim, Citation2019; CSR customers, CSR employees, CSR environment, and CSR local community:; Siyal et al., Citation2022). Shanak et al. (Citation2020) have brought other empirical evidence for the significant positive relationship between aggregate OC and aggregate CSR, this time, employing Denison’s model (Denison & Mishra, Citation1995).

Another set of empirical literature that has been using the rather tailored concept of “stakeholder culture” (Jones et al., Citation2007), and its variants, have also carried out supportive empirical evidence for this link (Kowalczyk, Citation2019; Wan et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, case studies, on their part, have provided another witness for the positive effect (e.g. Culler, Citation2010; D’Aprile et al., Citation2012). However, there has been a paucity of the empirical literature on the link in the domestic literature; to mention one notable study, Tsegaw and Yohannes (Citation2019) have found this: “the level of CSR practice […] is directly influenced by organizational culture” (p. 24).

4.3.6. Interaction/Moderation effect of organizational culture

The moderation analysis of organizational culture has indicated that it plays a significant negative moderating effect in the ISP-CSR practice link (overall model fit: R2 = 0.84, F = 85.91, p < 0.05; incremental R2 = 0.019, ΔF = 5.76, p < 0.05; B= −0.219,t = −2.40, SE = 0.091, p < 0.05; Cohen’s See Table ). The test statistics in general present strong empirical evidence in favor of H3. For further inquiry, simple slope plots and their corresponding significance tests (see Figure ) have been held, as per the suggestions and template of Dawson (Citation2014).

Figure 4. The moderating effect of organizational culture on stakeholder pressure-CSR practice relationship.

The moderation thesis was built on theoretical works that strongly posit its moderation role, both in management research and in particular CSR links (Ogola & Mària, Citation2020). And this set of theoretical propositions has obtained empirical support. The empirical literature, however, has geared towards the moderation effect of OC dimensions, rather than the aggregate one (e.g., Chu et al., Citation2018; M. Lee & Kim, Citation2017).

The negative moderation of OC in the link would be better explained by the “CSR development” model of Maon et al. (Citation2010), the synonymous concepts of “stakeholder culture” (Boesso & Kumar, Citation2016; Jones et al., Citation2007; Wan et al., Citation2020; Yu & Choi, Citation2016), the presence/absence of distinct organizational culture (Cameron & Ettington, Citation1988; Jaakson et al., Citation2012), “managing for stakeholders” notion of Freeman (R. E. Freeman et al., Citation2010).

A low organizational culture would mean all these: (1) as per Maon et al. (Citation2010), a culture characterized as “cultural reluctance”, in which CSR is taken as a constraint, and thus, stakeholders exert pressure to ensure their interests; (2) an organizational culture deprived of “Stakeholder culture” (Jones et al., Citation2007) that invites much stakeholder questions; (3) there exists no clearly established “cultural type” within the organization (Jaakson et al., Citation2012); and (4) a culture less considerate of “creating value for stakeholders” (R. E. Freeman et al., Citation2010). In these instances (when organization culture is “low”), stakeholder pressure takes the initiating role for CSR practice, suggesting that the ISP-CSR link becomes stronger, i.e., Organizational culture plays a significant positive moderation role in such organizational situations.

On the contrary, high organizational culture would be interpreted as an organizational culture characterized by “cultural embedment” (Maon et al., Citation2010), “CSR-Oriented Culture” (Yu & Choi, Citation2016), the culture of distinct type (Jaakson et al., Citation2012), and considerate stakeholder values (R. E. Freeman et al., Citation2010). When an organization achieves those features of OC (when an organizational culture is “high”), Organizational culture itself embeds stakeholder notion, so pressure from owners/employees would not be demanding. In a nutshell, as an organizational culture becomes embedding, stakeholder-oriented, distinctly identified, and considerate of stakeholder values, the influence of stakeholder pressure diminishes. In such an organizational arena, organizational culture plays the role of initiating CSR practices; thus, it shifts from the role of moderation to direct effect.

5. Implications of the findings

5.1. Theoretical implications

First, it has brought additional evidence for the construct validity (content validity, discriminant validity, convergent validity, and nomological validities) for the constructs of stakeholder-based CSR, stakeholder pressure, and organizational culture. Second, the study contributes to the long-waited project of employing a stakeholder approach to CSR conceptualization and operationalization (Carroll, Citation1991; Clarkson, Citation1995; Wood & Jones, Citation1995). More tied to the above contribution, the study strengthens the argument that direct recipients—stakeholders—of the responsibilities be given the chance to evaluate CSR performance (Wood & Jones, Citation1995). Fourth, this work contributes to existing knowledge of CSR practices by providing moderation analysis, especially sought in developing countries (Jamali & Karam, Citation2018). Fifth, the principal theoretical implication of this study is that the proposition of both stakeholder identification and salience (SIS) theory and the sociological view of organizational culture have got huge empirical support. Taking two of the stakeholder groups (employees and owners), the SIS theory has been supported: the presence of the attributes leads to an improvement in CSR practice. Regarding the influence of organizational culture, the results of this research support the idea that organizational culture is a huge determinant and strong moderator of CSR practices.

About theory pruning (Aguinis & Glavas, Citation2012), this contribution is worthy of mentioning. CSR research has been accused of being a place for mainly institutional and stakeholder theories (Frynas & Yamahaki, Citation2016). As a response to calls for going salient theories, this work has provided some insight into the explaining power and application of two theories (stakeholder theory and cultural theory) in CSR practice.

5.2. Practical implications

The findings of this study have some important implications for future practice. For CSR practice to be improved, organizational managers are supposed to (1) monitor and address employees’ and owners’ interests, desires, and questions (internal stakeholders’ pressure), (2) cultivate and shape organizational culture, by its inclusive nature, it potentially erodes and enhances organizational practices related to CSR, and (3) aware that organizational culture plays the dual role of direct effect by itself and interaction effect thereof with stakeholder pressure.

6. Conclusions, limitations, and future research

6.1. Conclusions

The main goal of the current study was to determine the effect of two selected organizational-level variables (internal stakeholders’ pressure and organizational culture) on CSR practices, relying on stakeholder and cultural theories. More specifically, the study aimed to (1) ascertain the effect of internal stakeholders’ pressures (employees’ and owners’ pressures) on CSR practice, (2) find out the influence of organizational culture on CSR practice, and (3) determine the moderating role of organizational culture in internal stakeholders’ pressure-CSR practice link.

The results of this investigation show that, first, both internal stakeholders’ pressure and organizational culture emerged as reliable determinants of CSR practices; the more pressure felt from employees and owners, and the more organizational culture installed, the better CSR practices would be. The second major finding was that organizational culture, besides direct effect, plays a moderation role in the stakeholder pressure-CSR practice link. Low organizational culture (absence or less of an established organizational culture), unlike high organizational culture, is a significant conduit for stakeholder pressure to impact change on CSR practices. By doing so, the study has been fully successful in meeting its aims. The study supported the proposition that organizational-level variables remain potential enabling factors for the improvement of CSR practice. Theoretically, stakeholder and cultural theories have obtained other empirical support.

6.2. Limitations of the study

Despite its valuable contributions, the study involves some limitations that call for cautious attention. First, the scope of this study was limited to large manufacturing firms in a region (Amhara) of Ethiopia. As the study confined its scope to “Large manufacturing businesses”, caution should be there in generalizing the findings to other sectors of business and sizes of manufacturing firms. The second limitation relates to the nature of the data; longitudinal data are relevant and highly recommended in the literature (e.g. Aguinis & Glavas, Citation2012; Jamali & Karam, Citation2018), such data set could not be used because these data were both non-available and required repeated measures, which, in this case, had been impractical, given numerous constraints. Thirdly, calls have been made to go for a mixed research approach (e.g. Lockett et al., Citation2006). But because the study is geared towards establishing “effects”, it has delimited itself to an exclusively quantitative research approach.

6.3. Recommendations for future research

This research has thrown up some inquiry points in need of further investigation. First, a natural progression of this work would be to replicate the study in different settings and design options. Second, another future inquiry point pertains to CSR principles and processes (Wood, Citation1991). CSR, as used here, is confined to the performance dimension of the corporate social performance (CSP) model (Culler, Citation2010; Wood, Citation1991). Thus, because the principles and process dimensions of the CSP model were out of the scope of the inquiry, future research would turn attention to the analysis of principles and processes of CSR. The third fruitful area for further work would be to see the effect of the same variables of this study on specific stakeholder-oriented CSR practices. For example, a future study would target the effect of employees’ pressure or owners’ pressure, each taken solely, on each of employees-oriented CSR, Customer-oriented CSR, or community oriented CSR. A similar design would be though about the effect of organizational cultural on specific stakeholder-oriented CSR practice.

As a way to further improvement of the research objectives, replica and/or new studies with some design modifications and specific-stakeholder operationalization of CSR would be pursued in future inquiries. The study would be replicated in different and similar contexts.

To delineate potential scope, it would be fruitful to focus further inquiries on selected themes. First, instead of applying the menu-like alternative B&S concepts, we suggest further inquiry to consistently use the concept of CSR (Carroll, Citation2015). This firm stand would potentially alleviate confusion (Godfrey & Hatch, Citation2007) and variegation views (De Bakker et al., Citation2005). Second, further studies shall gear attention to multilevel empirical studies (Ogola & Mària, Citation2020). By dropping the endless debates on normative notions (Wood, Citation2010), future CSR inquiry shall dig at contextual factors attributing to promote CSR performance. Fourth, we strongly suggest that the conceptualization and measurement of CSR ought to be matched to stakeholder theory.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adner, R., & Helfat, C. E. (2003). Corporate effects and dynamic managerial capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 24(10), 1011–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.331

- Adomako, S., & Tran, M. D. (2022). Stakeholder management, CSR commitment, corporate social performance: The moderating role of uncertainty in CSR regulation. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 29(5), 1414–1423. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2278

- Agle, B. R., Mitchell, R. K., & Sonnenfeld, J. (1999). Who matters to CEOs? An investigation of stakeholder attributes and salience, corporate performance, and CEO values. Academy of Management Journal, 42(5), 507–525. https://doi.org/10.2307/256973

- Aguilera, R. V., Rupp, D. E., Williams, C. A., & Ganapathi, J. (2007). Putting the s back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. The Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 836–863. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.25275678

- Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2012). What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research Agenda. Journal of Management, 38(4), 932–968. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311436079

- Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2019). On corporate social responsibility, sensemaking, and the search for meaningfulness through work. Journal of Management, 45(3), 1057–1086. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317691575

- Aguinis, H., Gottfredson, R. K., & Joo, H. (2013). Best-practice recommendations for defining, identifying, and handling outliers. Organizational Research Methods, 16(2), 270–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112470848

- Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications.

- Amin-Chaudhry, A. (2016). Corporate social responsibility-from a mere concept to an expected business practice. Social Responsibility Journal, 12(1), 190–207. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-02-2015-0033

- Athanasopoulou, A., & Selsky, J. W. (2015). The social context of corporate social responsibility: Enriching research with multiple perspectives and multiple levels. Business and Society, 54(3), 322–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650312449260

- Bandalos, D. L. (2002). The effects of item parceling on goodness-of-fit and parameter estimate bias in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(1), 78–102. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0901_5

- Bar-Haim, A., & Karassin, O. (2018). A multilevel model of responsibility towards employees as a dimension of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Management and Sustainability, 8(3), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.5539/jms.v8n3p1

- Barnett, M. L. (2007). Stakeholder influence capacity and the variability of financial returns to corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 794–816. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.25275520

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The Moderator-Mediator variable distinction in social psychological research conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Becker, T. E. (2005). Potential problems in the statistical control of variables in organizational research: A qualitative analysis with recommendations. Organizational Research Methods, 8(3), 274–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428105278021

- Becker, T. E., Atinc, G., Breaugh, J. A., Carlson, K. D., Edwards, J. R., & Spector, P. E. (2016). Statistical control in correlational studies: 10 essential recommendations for organizational researchers. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(2), 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2053

- Bell, B. A., Ferron, J. M., & Kromrey, J. D. (2008). Cluster size in multilevel models: The impact of sparse data structures on point and interval estimates in two-level models. Section on Survey Research Methods – JSM proceedings (pp. 1122–1129).

- Boesso, G., & Kumar, K. (2016). Examining the association between stakeholder culture, stakeholder salience, and stakeholder engagement activities: An empirical study. Management Decision, 54(4), 815–831. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-06-2015-0245

- Bowen, H. R. (1953). Social responsibilities of the businessman. University of Iowa Press, Iowa city, USA.

- Buchholz, R. A., & Rosenthal, S. B. (1997). Business and society: What’s in a name. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 5(2), 180–201. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb028867

- Byrne, B. M. (2012). Structural equation modeling with Mplus. Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203807644

- Cameron, K. S., & Ettington, D. R. (1988). The conceptual foundation of organizational culture. Working Paper #544. Divsion of Research, School of Business Administration, University of Michigan foundation of organizational culture. (544)

- Cameron, K. S., & Quinn, R. E. (2011). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture. based on the competing values framework. (3rd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Campanelli, P. (2008). Testing Survey questions. In E. de Leeuw, J. Hox, & D. Dillman (Eds.), Internatonal Handbook of Survey Methodology (pp. 176–200). New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Carlson, K. D., & Wu, J. (2012). The illusion of statistical control: control variable practice in management research. Organizational Research Methods, 15(3), 413–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428111428817

- Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. The Academy of Management Review, 4(4), 497–505. https://doi.org/10.2307/257850

- Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons, 34(4), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/0007-68139190005-G

- Carroll, A. B. (2000). A commentary and an overview of key questions on corporate social performance measurement. Business & Society, 39(4), 466–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/000765030003900406

- Carroll, A. B. (2015). Corporate social responsibility: The centerpiece of competing and complementary frameworks. Organizational Dynamics, 44(2), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2015.02.002

- Chu, Z., Wang, L., & Lai, F. (2018). Customer pressure and green innovations at third party logistics providers in China: The moderation effect of organizational culture. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 30(1), 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-11-2017-0294

- Clarkson, M. E. (1995). A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 92–117. https://doi.org/10.2307/258888

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. second). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S., & Aiken, L. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Cortina, J. M. (1993). Interaction, nonlinearity, and multicollinearity: Implications for multiple regression. Journal of Management, 19(4), 915–922. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639301900411

- Crossland, C., & Hambrick, D. C. (2007). How national systems differ in their constraints on corporate executives: A study of CEO effects in three countries. Strategic Management Journal, 28(8), 767–789. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.610

- Culler, C. (2010). Good works: Assessing the relationship between organizational culture, corporate social responsibility programs, and weberian theory. International Journal of Arts & Sciences, 3(13), 357–374.

- Dai, J., Chan, H. K., & Yee, R. W. Y. (2018). Examining moderating effect of organizational culture on the relationship between market pressure and corporate environmental strategy. Industrial Marketing Management, 74, 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2018.05.003

- D’Amato, A., & Falivena, C. (2019). Corporate social responsibility and firm value: Do firm size and age matter? Empirical evidence from European listed companies. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(2), 909–924. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1855

- D’Aprile, G., Mannarini, T., & Robinson, S. (2012). Corporate social responsibility: A psychosocial multidimensional construct. Journal of Global Responsibility, 3(1), 48–65. https://doi.org/10.1108/20412561211219283

- Dawson, J. F. (2014). Moderation in management research: What, why, when, and how. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9308-7

- De Bakker, F. G. A., Groenewegen, P., & Den Hond, F. (2005). A bibliometric analysis of 30 years of research and theory on corporate social responsibility and corporate social performance. Business and Society, 44(3), 283–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650305278086

- Denison, D. R., & Mishra, A. K. (1995). Toward a theory of organizational culture and effectiveness. Organization Science, 6(2), 204–223. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.6.2.204

- Dong, S., Burritt, R., & Qian, W. (2014). Salient stakeholders in corporate social responsibility reporting by Chinese mining and minerals companies. Journal of Cleaner Production, 84(1), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.01.012

- El Akremi, A., Gond, J. P., Swaen, V., De Roeck, K., & Igalens, J. (2018). How do employees perceive corporate responsibility? Development and validation of a multidimensional corporate stakeholder responsibility scale. Journal of Management, 44(2), 619–657. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315569311

- Ellis, P. D. (2010). The essential guide to effect sizes: Statistical power, meta-analysis, and the interpretation of research results. Cambridge University Press.

- Enders, C. K. (2003). Using the expectation maximization algorithm to estimate coefficient alpha for scales with item-level missing data. Psychological Methods, 8(3), 322–337. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.8.3.322

- Enders, C. K., & Tofighi, D. (2007). Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods, 12(2), 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121

- Eshetu, O. M. (2019). The role of corporate social responsibility on employees organizational commitment ; with a mediating affect of organizational justice: A case of Gondar City, bank sector, Ethiopia. Research Journal of Commerce & Behavioural Science, 8(6), 8–17.

- Eyasu, A. M., Endale, M., & Ntim, C. G. (2020). Corporate social responsibility in agro-processing and garment industry: Evidence from Ethiopia. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1720945

- Faller, C. M., & Zu Knyphausen-Aufseß, D. (2016). Does equity ownership matter for corporate social responsibility? A literature review of theories and recent empirical findings. Journal of Business Ethics, 150(1), 15–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3122-x

- Fassin, Y. (2009). The stakeholder model refined. Journal of Business Ethics, 84(1), 113–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9677-4

- Fentaw, T. (2016). Environmental social responsible practices of hospitality industry: The case of first level hotels and lodges in Gondar city, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Environmental Studies and Management, 9(2), 235–244. https://doi.org/10.4314/ejesm.v9i2.11

- Fornell, C. F., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Frederick, W. C. (1960). Business responsibility. Califonia Management Review, 2(4), 54–61. https://doi.org/10.2307/41165405

- Freeman, E. R. (1984). Strategic management. A stakeholder approach. Pitman Publishing Inc.

- Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., & Wicks, A. C. (2007). Managing for Stakeholders. Survival, Reputation, and Success. Yale University Press.

- Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., Wicks, A. C., Parmar, B., & de Colle, S. (2010). Stakeholder theory: The state of the art. Cambridge University Press.

- Frynas, J. G., & Yamahaki, C. (2016). Corporate social responsibility: Review and roadmap of theoretical perspectives. Business Ethics: A European Review, 25(3), 258–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12115

- Galbreath, J. (2010). Drivers of corporate social responsibility: The role of formal strategic planning and firm culture. British Journal of Management, 21(2), 511–525. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2009.00633.x

- Gemechu, S., Fiseha, S., & Yirga, M. (2020). Assessment of corporate social responsibility: The case of manufacturing companies in gurage zone, Ethiopia. Current Journal of Applied Science and Technology, 39(16), 154–162. https://doi.org/10.9734/cjast/2020/v39i1630780

- Godfrey, P. C., & Hatch, N. W. (2007). Researching corporate social responsibility: An Agenda for the 21st century. Journal of Business Ethics, 70(1), 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9080-y

- González-Rodríguez, M. R., Martín-Samper, R. C., Köseoglu, M. A., & Okumus, F. (2019). Hotels’ corporate social responsibility practices, organizational culture, firm reputation, and performance. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(3), 398–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1585441

- Hailu, F. K., & Rao, K. R. M. (2016). Perception of local community on corporate social responsibility of brewery firms in Ethiopia. International Journal of Science and Research, 5(3), 316–322. https://doi.org/10.21275/v5i3.nov161816

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Andersen, R. E. (2009). Multivariate data analysis.

- Helmig, B., Spraul, K., & Ingenhoff, D. (2016). Under positive pressure: how stakeholder pressure affects corporate social responsibility implementation. Business and Society, 55(2), 151–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650313477841

- Hernández-Arzaba, J. C., Nazir, S., Leyva-Hernández, S. N., & Muhyaddin, S. (2022). Stakeholder Pressure engaged with circular economy principles and economic and environmental performance. Sustainability, 14(23), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316302

- Hofmann, D. A. (2002). Issues in multilevel research: Theory development, measurement, and analysis. In S. G. Rogelberg (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 247–274). Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Hox, J. J., Maas, C. J. M., & Brinkhuis, M. J. S. (2010). The effect of estimation method and sample size in multilevel structural equation modeling. Statistica Neerlandica, 64(2), 157–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9574.2009.00445.x

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2012). What drives corporate social performance? the role of nation-level institutions. Journal of International Business Studies, 43(9), 834–864. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2012.26

- Jaakson, K., Reino, A., & Mõtsmees, P. (2012). Is there a coherence between organizational culture and changes in corporate social responsibility in an economic downturn? Baltic Journal of Management, 7(2), 202–216. https://doi.org/10.1108/17465261211219813

- Jamali, D., & Karam, C. (2018). Corporate social responsibility in developing countries as an emerging field of study. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20(1), 32–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12112

- Jha, A., & Aggrawal, V. S. (2020). Institutional pressures for corporate social responsibility implementation: A study of Indian executives. Social Responsibility Journal, 16(4), 555–577. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-11-2018-0311

- Jones, T. M., Felps, W., & Bigley, G. A. (2007). Ethical theory and stakeholder related decisions: The role of stakeholder culture. Academy of Management Review, 32(1), 137–155. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.23463924

- Jose, P. E. (2013). Doing statistical mediation & moderation. The Guilford Press.

- Karassin, O., & Bar-Haim, A. (2016). Explaining corporate social performance through multilevel analysis. In L. Rayman-Bacchus & P. R. Walsh (Eds.), Corporate responsibility and sustainable development: Exploring the nexus of private and public interests (pp. 119–148). Routledge.

- Karassin, O., & Bar-Haim, A. (2019). How regulation effects corporate social responsibility: Corporate environmental performance under different regulatory scenarios. World Political Science, 15(1), 25–53. https://doi.org/10.1515/wps-2019-0005

- Kassinis, G., & Vafeas, N. (2006). Stakeholder pressures and environmental performance. Academy of Management Journal, 49(1), 145–159. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.20785799

- Kline, R. B. (2004). Beyond significance testing reforming data analysis methods in behavioral research. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10693-000

- Klonoski, R. J. (1991). Foundational considerations in the corporate social responsibility debate. Business Horizons, 34(4), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/0007-68139190002-D

- Kowalczyk, R. (2019). Relationships between stakeholder pressure, culture, and CSR practices in the context of project management in the construction industry in Poland. Proceedings of the 33rd International Business Information Management Association Conference, IBIMA 2019: Education Excellence and Innovation Management through Vision 2020, Granada, Spain (pp. 5663–5671).

- Laplume, A. O., Sonpar, K., & Litz, R. A. (2008). Stakeholder theory: Reviewing a theory that moves us. Journal of Management, 34(6). https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308324322

- LeBreton, J. M., & Senter, J. L. (2008). Answers to 20 questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organizational Research Methods, 11(4), 815–852. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428106296642

- Lee, M. D. P. (2008). A review of the theories of corporate social responsibility: Its evolutionary path and the road ahead. International Journal of Management Reviews, 10(1), 53–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2007.00226.x

- Lee, M., & Kim, H. (2017). Exploring the organizational culture’s moderating role of effects of corporate social responsibility (CSR) on firm performance: Focused on corporate contributions in Korea. Sustainability, 9(10), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101883

- Lockett, A., Moon, J., & Visser, W. (2006). Corporate social responsibility in management research: Focus, nature, salience and sources of influence. Journal of Management Studies, 43(1), 115–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00585.x

- Maon, F., Lindgreen, A., & Swaen, V. (2010). Organizational stages and cultural phases: A critical review and a consolidative model of corporate social responsibility development. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(1), 20–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2009.00278.x

- Matten, D., & Moon, J. (2008). “Implicit” and “Explicit” CSR: A conceptual framework for a comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 33(2), 404–424. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2008.31193458

- Mattingly, J. E. (2017). Corporate social performance: A review of empirical research examining the corporation–society relationship using Kinder, Lydenberg, Domini social ratings data. Business and Society, 56(6), 796–839. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650315585761

- Mazzei, M. J., Gangloff, A. K., & Shook, C. L. (2015). Examining multi-level effects on corporate social responsibility and irresponsibility Matthew. Management & Marketing Challenges for the Knowledge Society, 10(3), 163–184. https://doi.org/10.1515/mmcks-2015-0013

- Mishra, S., & Suar, D. (2010). Does corporate social responsibility influence firm performance of Indian companies? Journal of Business Ethics, 95(4), 571–601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0441-1

- Mitchell, R. K., Agle, B. R., & Wood, D. J. (1997). Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. The Academy of Management Review, 22(4), 853–886. https://doi.org/10.2307/259247