?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study investigates the impact of ownership structure on firms’ audit report lag. The research sampled 102 Saudi non-financial listed companies’ data from 2012 to 2021. The data was analysed using a generalised method of moments (GMM) framework. The findings significantly suggest that as managerial ownership rises, audit delay may increase. However, family and institutional ownership may enhance the financial reporting timeliness of the firms. Also, the results demonstrate that government ownership appears insignificant in determining the firms’ audit delay. The outcome of this study implies that in the Saudi context, family and institutional monitoring seems to be an effective control mechanism that may force managers to embrace the timely disclosure of financial reports. Policymakers and investors may find the research outcome helpful in understanding additional factors influencing audit report lag. Thus, reducing the financial reporting lag may mitigate information asymmetry, thereby enhancing investors’ confidence.

1. Introduction

One of the major aims of financial reporting is to offer financial information to shareholders to enable them to take various decisions (Bajary et al., Citation2023; Oradi, Citation2021). Financial reporting timeliness is regarded as one of the qualitative characteristics of financial reporting, and it means making information available to the accounting information users when due (Agyei-Mensah, Citation2018; Durand, Citation2019; Musah et al., Citation2023). This information needs to be timely to enable financial statement users to make informed decisions. Also, financial reporting guidelines across the globe have emphasised the significance of timely disclosure in enhancing transparency and accountability in firms’ governance (Aksoy et al., Citation2021; Khlif & Samaha, Citation2014; Yeboah et al., Citation2023). Delaying the release of financial information (Audit report lag) can create information asymmetry among stakeholders, thus creating uncertainties in investment decisions (Ebaid, Citation2022; Singh et al., Citation2022; Waris & Haji Din, Citation2023). Therefore, this high disclosure may raise the quality and relevance of accounting information and secure stock market participants’ confidence. Since investors, regulators, policymakers, and academics have given much attention to financial reporting timeliness, understanding the factors influencing companies’ financial reporting lag remained crucial.

Accordingly, many studies provided evidence that the board governance mechanisms may influence audit report lag (Baatwah et al., Citation2015; Dobija & Puławska, Citation2022; Hassan, Citation2016; Oradi, Citation2021; Oussii & Taktak, Citation2018; Waris & Haji Din, Citation2023). Additionally, many empirical works examined the impact of firm-level attributes on timely corporate disclosure (Abdillah et al., Citation2019; Agyei-Mensah, Citation2018; Chen et al., Citation2022; Ebaid, Citation2022; Singh et al., Citation2022). In sum, these prior works argue that sound internal governance may determine the organisational outcome, thus facilitating timely financial disclosure. Moreover, it is widely believed that corporate ownership is a crucial corporate governance mechanism that can enhance organisational efficiency (Jensen, Citation1993; Kao et al., Citation2019; Le & Nguyen, Citation2023; Short & Keasey, Citation1999). According to this school of thought, extensive monitoring from ownership can remediate firms’ internal control effectiveness and reduces financial misstatement, thereby improving financial reporting quality (Bajaher et al., Citation2021; Bazhair & Alshareef, Citation2022; Hasan et al., Citation2022). However, despite revealing the crucial role of corporate ownership in promoting organisational efficiency, only a few studies evaluate the effect of ownership structure on audit report lag (Aksoy et al., Citation2021; Alfraih, Citation2016; Basuony et al., Citation2016).

More specifically, prior studies mainly concentrate on institutional ownership, neglecting other dimensions of ownership structure (Basuony et al., Citation2016; Ebaid, Citation2022; Patricia, Citation2022). Besides, the bulk of past empirical works on firms’ audit delay determinants wholly employed static estimation methods (such as OLS and fixed effects) and thus ignored financial reporting lag dynamism. In particular, there is an increasing understanding that corporate governance and financial reporting decisions may be dynamic (Bazhair & Alshareef, Citation2022; Duru et al., Citation2016). Also, it may be possible that ownership structure-financial reporting lag may partly be endogenous. Similarly, unobserved firm-specific effects may partially influence financial reporting lag, which static estimators may fail to account for (Bazhair, Citation2023; Habimana, Citation2017; Ozkan, Citation2001). In this way, static estimation techniques may be inconsistent and less efficient when an endogeneity arises. Hence, these gaps in the literature motivate the conduct of this research.

Hence, this study uses a dynamic framework to examine the effect of ownership structure on Saudi companies’ audit report lag. The dynamic analysis reveals that Saudi firms adjust their financial reporting systems to achieve timelier disclosure. Also, the evidence suggests that Saudi companies with higher managerial ownership may be associated with longer audit delays. However, institutional and family ownership may enhance the financial reporting timeliness of the firms. Surprisingly the results demonstrate that government ownership appears insignificant in determining the firms’ audit delay.

Hence, this research contributes to the literature by providing a broader empirical analysis of how different ownership monitoring mechanisms may influence financial reporting timeliness. Secondly, the empirical study broadens the limited empirical literature on financial reporting timeliness in developing countries because corporate disclosure seems to be lesser in emerging markets (Al-Bassam et al., Citation2018; Bajaher et al., Citation2021; Bajary et al., Citation2023). Thirdly, this research provides further insight into the growing literature on the dynamism of financial reporting systems. As such, this study offers more consistent empirical evidence by applying a robust methodology that addresses the endogeneity issue inherent in corporate governance studies. Finally, regulators and policymakers may find this study helpful in designing policies that enhance financial reporting quality from emerging countries’ perspectives with the view to attracting foreign investments.

The rest of this article continues as follows: the second segment focuses on the Saudi institutional background. The following parts include the literature review and hypotheses development, research design, presentation and discussion of empirical results. The last segment concludes the paper.

2. Institutional background

Saudi Arabia is located in the Southwest of the Asian continent. The country practices an Islamic governance system and operates a kingship political system, where the King doubles as the head of state and prime minister (Albassam & Ntim, Citation2017; Sarhan et al., Citation2019). The oil sector is the backbone of the Saudi economy, and it is estimated that the nation contributes about 35% to the world oil market (Alregab, Citation2021). More importantly, it is the largest and the most liquid stock market in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Another unique feature of Saudi is that corporate ownership is concentrated among families and the government (Bajaher et al., Citation2021; Boshnak, Citation2021b). More importantly, the Saudi corporate governance code was officially established in 2006 and amended in 2017 to strengthen internal control mechanisms across firms in the country’s stock market (Al-Ghamdi & Rhodes, Citation2015). Additionally, one of the stock market regulations requires listed companies in the country to submit their financial statements 40 days after the end of their financial year.

Other relevant legislation that guides financial reporting includes the Saudi Organisation for Certified Public Accountants (SOCPA), which was instituted in 1964. This body also emphasised that listed companies should have their annual financial statements audited by external auditors to ensure greater accountability and transparency in firms’ governance (Boshnak, Citation2021a). The SOCPA, in partnership with the Ministry of Commerce and Investment (MCI), ensures that high standards are maintained regarding audit and accounting practices (Alzeban, Citation2020). These agencies also monitor and enforce regulations that guarantee disclosure and strengthen audit quality to boost investors’ confidence. In sum, these legislations significantly regulate the financial reporting behaviour in the Saudi corporate environment.

Furthermore, the Saudi corporate sector is chosen for this study because enhancing financial reporting quality should be emphasised in the country due to its institutional weakness and ineffective market for corporate control (Al-Bassam et al., Citation2018; Alregab, Citation2021; Habbash, Citation2016). However, specific reforms are being undertaken in the country’s corporate sector to attract foreign investment. The country attached more emphasis on robust corporate governance practices to actualise its vision for 2030. Specifically, one of the vision’s central targets is to increase the country’s GDP (Alregab, Citation2021). Also, the Saudi authorities recognise the need to empower the country’s capital market performance, thereby diversifying the Saudi economy from its dependence on oil revenue. Similarly, the capital market authorities have since mandated all listed companies to migrate to international financial reporting standards (IFRS) effective NaN Invalid Date . These reforms may have an implication on financial reporting quality and disclosure.

3. Theoretical literature review

This section reviews the theoretical literature concerning the nexus between ownership structure and financial reporting lag.

3.1. Agency theory

Agency theory highlights the relevance of corporate ownership in influencing financial reporting timeliness. This framework raised concern about the conflict of interests inherent in modern business organisations due to the separation between management and firms’ ownership (Bazhair, Citation2023; Ha et al., Citation2022; Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). This separation may create information disparity between managers and shareholders, leading to agency conflicts (Alves, Citation2023; Fama & Jensen, Citation1983; Manogna, Citation2021). According to this school of thought, shareholders’ monitoring may compel managers to design better policies to enhance organisational efficiency. Likewise, it is reported that robust supervision from ownership structure may control managerial discretion and earnings misstatements (Le & Nguyen, Citation2023; Shleifer & Vishny, Citation1997; Andrei; Shleifer & Vishny, Citation1986). This stringent monitoring may also influence management to embrace high disclosure and thorough financial statements audit. This framework emphasises that ownership monitoring may strengthen firms’ internal control systems and raise financial reporting quality (Hasan et al., Citation2022). Owners’ involvement in firms’ internal matters may reduce managerial entrenchment because they regularly demand information regarding firm performance to monitor their earnings growth (Hasan et al., Citation2022; Ngo et al., Citation2020). Therefore, it is expected that ownership structure monitoring may minimise financial reporting lag. In sum, agency literature provides a framework for understanding how diverse monitoring skills from corporate ownership may influence organisational efficiency, such as timelier financial reporting.

3.2. Stakeholder theory

On the other hand, the stakeholder theory may also underpin the nexus between ownership structure and financial reporting timeliness. Based on this perspective, a stakeholder is any individual or group who can influence or be affected by achieving a firm’s objective (Freeman, Citation1994; Ledi & Xemalordzo, Citation2023). It is a framework that focuses on business ethics and moral values in organisational management (Aksoy et al., Citation2021; Bouguerra et al., Citation2023; Law, Citation2011). Thus, this theory suggests that firms’ managers should look into the diverse needs of different stakeholders. Accordingly, one of the essential stakeholders this theory recognises is the owners (Elhaj et al., Citation2018; Habbash, Citation2016). Among the crucial needs of shareholders is the timely release of financial statements to enable them to make various investment decisions (Di Vaio et al., Citation2023; Hill & Jones, Citation1992). Disseminating financial reports may reduce information disparity between managers and outsiders, thereby enhancing organisational efficiency. Under the stakeholder framework, ownership structure may negatively influence audit delay (Basuony et al., Citation2016; Ebaid, Citation2022). The owners may demand timely disclosure from management to monitor their earnings growth. Although corporate ownership is of different categories with distinct needs and priorities, timely financial disclosure has been reported to be among the top priorities of corporate owners (Habbash, Citation2016; Law, Citation2011). Overall, the main concern of this perspective is that owners as capital providers are entitled to information from management, which can be achieved through the disclosure of financial reporting.

4. Empirical review and hypotheses development

This section discusses each ownership structure and how it impacts the audit reporting lag. Moreover, based on the literature, the hypotheses were developed for possible examination of the phenomenon.

4.1. Managerial ownership and audit report lag

Managerial ownership is one of the corporate governance mechanisms suggested by the agency theory. This perspective suggests that managerial shareholding may incentivise managers to work diligently for better organisational outcomes (Alabdullah, Citation2018; Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976; Le & Nguyen, Citation2023). In addition, this control mechanism encourages managers to have a sense of belonging in firm management. Thus, this control strategy may prevent them from designing sub-optimal and inefficient investment decisions (Nguyen et al., Citation2021). Also, it is argued that managerial ownership may help align the divergent motives of managers and shareholders, thereby reducing information asymmetry and minimising agency conflicts (Alves, Citation2023; Boateng et al., Citation2017). However, some studies raised concern about the possibility that a high level of managerial ownership may result in managerial entrenchment (Berger et al., Citation1997; Le & Nguyen, Citation2023; Shan, Citation2019). In addition, this high shareholding may give managers an incentive to maximise their compensations at the expense of shareholders’ wealth (Sani, Citation2020). Empirical evidence indicated that firms with a higher managerial or director ownership ratio might be associated with financial reporting lapses and weak internal control systems (Basuony et al., Citation2016). In contrast, Mitra et al. (Citation2012) and Hassan (Citation2016) found a negative association between managerial shareholding and audit delay. In this way, improving internal governance may reduce external audit queries, facilitating timelier financial information disclosure. More importantly, the Saudi corporate sector has less developed institutional frameworks and weak investor protection (Al-Bassam et al., Citation2018; Alregab, Citation2021; Bazhair, Citation2023). Thus, studies perceived that managerial ownership might serve as an important mechanism that can strengthen the corporate governance system in the country (Al-Matari, Citation2022; Albassam & Ntim, Citation2017; Sarhan et al., Citation2019). Based on these arguments, this hypothesis is stated:

H1:

Managerial ownership is associated with audit report lag.

4.2. Family ownership and audit report lag

Family ownership is a powerful corporate control mechanism in emerging and developed countries. The main purpose of this ownership structure is to promote shareholder wealth and to protect family prestige and affiliation (Al-Bassam et al., Citation2018; Manogna, Citation2021). In addition, this ownership structure attached more concern about retaining family control. Thus, family firms usually appoint their relatives to key management positions to monitor managers effectively (Manogna, Citation2021). Therefore, family ownership may promote high financial disclosure to showcase the firms’ integrity to outsiders. However, some studies suggested that family ownership may fuel agency conflicts in companies. For instance, it is argued that family-owned companies may be associated with the high infringement of minority shareholders’ interests (Bataineh & Ntim, Citation2021; Ha et al., Citation2022). These investors greatly influence board appointments in favour of their family members to maximise their control (Omri et al., Citation2014; Setiawan et al., Citation2016).

Empirical evidence by Waris and Haji Din (Citation2023) indicated a negative link between family ownership and audit report lag. This finding implies that monitoring from family shareholders may strengthen the internal control system and financial reporting quality. Hence, external auditors may require less time to scrutinise family-owned companies’ financial records, leading to lower audit report lag. The Saudi corporate sector is associated with high family ownership (Al Duais et al., Citation2021; Bazhair, Citation2023; Boshnak, Citation2021b). Thus, this type of corporate ownership may determine organisational outcomes because of their unique interest in maximising their wealth. In particular, studies suggested that the prevalence of family shareholding may influence managerial attitude, boards’ decisions quality and corporate disclosure in the country (Bajaher et al., Citation2021; Ebaid, Citation2022). Based on these discussions, this article formulated the following prediction:

H2:

Family ownership is associated with audit report lag.

4.3. Government ownership and audit report lag

Government shareholding may be essential in influencing organisational outcomes because it gives firms the resources and political connections they need for growth and development (Habbash, Citation2016; Le & Nguyen, Citation2023; Shao, Citation2019). Many studies argued that government ownership is associated with sound corporate governance practices due to the active monitoring of government forces in such organisations (Munisi et al., Citation2014; Wang et al., Citation2011). In addition, some studies emphasised that firms with concentrated state shareholding embrace high disclosure to signal their governance quality to the public (Ang & Ding, Citation2006; Le & Nguyen, Citation2023; Trong & Thuy, 2021). Hence, government monitoring may induce timely completion of the financial reporting process, leading to a shorter reporting lag. In contrast, some studies explained that government usually fail to exercise effective control over its investment, particularly in developing nations where control of corruption and enforcement of the law is relatively weaker (Bajaher et al., Citation2021; Habbash, Citation2016; Waris & Haji Din, Citation2023). Hence, substantial government ownership may erode sound corporate governance, and this practice may undermine financial information disclosure. In this regard, Alfraih (Citation2016) found that higher government ownership increases audit report lag. In this scenario, external auditors have to employ additional efforts in evaluating the effectiveness of internal control in such firms. Government ownership in private and public corporations is also high in Saudi (Al-Bassam et al., Citation2018; Alregab, Citation2021; Bazhair & Alshareef, Citation2022). Therefore, government shareholding may assist the firms in drawing valuable support, and its monitoring strategies may enhance financial reporting disclosure. Given these arguments, this research formulated the following hypothesis:2

H3:

There is an association between government ownership and audit report lag.

4.4. Institutional ownership and audit report lag

Several studies argued that institutional investors’ monitoring might shape organisational outcomes because of their technical knowledge and management expertise (Gillan & Starks, Citation2000; Jensen, Citation1993; Ledi & Xemalordzo, Citation2023). Examples of institutional investors include insurance firms, pension organisations, banks, and mutual funds. These investors have diverse monitoring strategies that can mitigate the entrenchment motive of managers to maximise their investment value (Bataineh & Ntim, Citation2021; Omran & Tahat, Citation2020; Patricia, Citation2022). In addition, studies reported that institutional investors’ diligent supervision might mitigate earnings management practices, and reduce agency costs, thereby minimising information disparity between shareholders and managers (Alvarez et al., Citation2018; Le & Nguyen, Citation2023; Ma, Citation2019). In this context, Mitra et al. (Citation2012) and Aksoy et al. (Citation2021)argued that as institutional shareholding rises, the probability of remediating internal control lapses will be greater. This evidence implies that these investors may offer valuable suggestions to managers on enhancing the effectiveness of internal audit functions and minimising audit risk. This effort may raise the external auditors’ confidence, reduce audit queries, and lower reporting lag. More importantly, empirical evidence indicated that firms might likely release their financial information timely due to these shareholders’ valuable advice and monitoring (Alfraih, Citation2016; Basuony et al., Citation2016; Patricia, Citation2022). Similarly, a Saudi study by Ebaid (Citation2022) found a negative relationship between audit report lag and institutional ownership. Additionally, it is reported that the Saudi corporate sector has a very low institutional shareholding (Alregab, Citation2021; Bazhair, Citation2023). This circumstance may weaken shareholder activism and thus affecting corporate disclosure in the country. Therefore, deducting from these arguments, the following hypothesis is predicted:

H4:

Institutional ownership is associated with audit report lag.

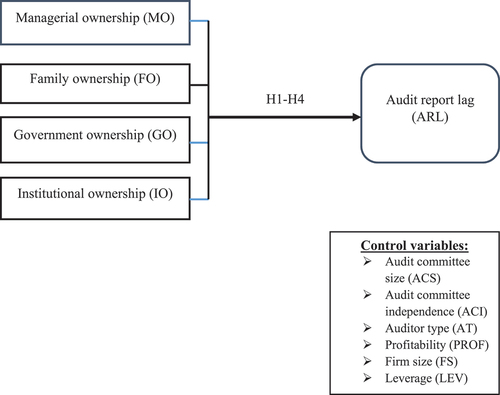

Consequently, based on the reviewed literature, this research designed the framework in Figure . According to this framework, managerial ownership is the independent variable and has four proxies. The dependent variable is audit report lag, while six variables were employed as control variables to make the model more robust and minimise specification bias.

5. Research design

5.1. Sampling and data source

The population of this research covers 198 Saudi-listed companies as of 31 December 2021. The research data spanned from the year 2012 to 2021. The Saudi stock market experienced several transformations that may impact financial disclosure, such as adopting international financial reporting and capital market reforms (Alregab, Citation2021; Ebaid, Citation2022). These exciting developments form the basis for choosing the study time frame. The sample selection procedure is shown in Table .

Table 1. Sample selection procedure

Moreover, as shown in Table , this paper focuses on the non-financial listed firms, and the study sample was constructed in the following manner. Firstly, financial firms were excluded from the study because of their peculiar financial reporting systems and regulations (Ebaid, Citation2022; Rajan & Zingales, Citation1995). Given that, a total of 42 Banks and insurance firms were dropped. Further, 22 companies with substantial missing data were step-downed from the study sample. Similarly, companies listed after 2012 and those that merged within the study period were not considered, leading to the exclusion of other 32 firms from the sample. Accordingly, Table displays the sample distribution across the firms from 2012 to 2021. Overall, the final sample comprised the data of 102 Saudi non-financial companies from 15 sectors. More importantly, the data for this research was gathered from three sources. Specifically, the firm-level data were obtained from the Saudi stock exchange website and the Eikon data stream. In addition, the corporate governance-related data were generated from the firms’ annual reports.

Table 2. Sample distribution

5.2. Study variables

5.2.1. Dependent variable

The dependent variable is audit report lag (ARL). Following existing literature, this paper measured ARL as the number of days between the accounting year end of a firm and the external auditors’ report date (Agyei-Mensah, Citation2018; Ebaid, Citation2022). Companies should have a shorter financial reporting lag because timeliness appears to be an essential determinant of firms’ governance quality (Singh et al., Citation2022).

5.2.2. Proxies for the independent variable

The independent variable is ownership structure and is measured using four proxies. These proxies include managerial ownership (MO), family ownership (FO), government ownership (GO), and institutional ownership (IO). This study focuses on these proxies because they are the most commonly used variables when examining the effect of corporate ownership on organisational outcomes (Bataineh & Ntim, Citation2021; Manogna, Citation2021; Nguyen et al., Citation2021; Sani, Citation2020). In particular, the agency theory suggests that ownership structure is an important control mechanism that can oversee managerial actions (Gillan & Starks, Citation2000; Hasan et al., Citation2022; Jensen, Citation1989). Thus, ownership structure may explain firms’ audit delay. The measurement of these proxies is contained in Table .

Table 3. Measurement of the variables

5.2.3. Control variables

Finally, this paper employs audit committee size (ACS), audit committee independence (ACI), auditor type (AT), profitability (ROA), firm size (FS) and leverage (LEV) as control variables. The justification for incorporating these variables is to minimise specification bias because prior studies indicated that these variables might influence audit report lag (Basuony et al., Citation2016; Chen et al., Citation2022; Ebaid, Citation2022). Regarding audit committee size, some studies stated that a smaller committee size is more suitable for ensuring the timely release of financial reports (Boshnak, Citation2021a; Hassan, Citation2016). It is argued that a larger audit committee may be associated with conflicts and a lack of cohesion among members because of communication differences (Lajmi & Yab, Citation2022). This constraint may affect the committee’s effectiveness in scrutinising financial reports, thereby widening the scope of the external auditors’ work and delaying the release of financial information. Hence, this paper expects a positive relationship between ACS and audit report lag.

Audit committee independence may also determine financial reporting timeliness. Accordingly, it is stated that independent directors monitor managers’ decisions and provide an essential advisory role to firms (Oussii & Taktak, Citation2018). Hence, many studies emphasised that the presence of these directors in the audit committee may assist firms in designing better policies to remedy their financial reporting weaknesses (Hasan et al., Citation2022; Lajmi & Yab, Citation2022). Strengthening the financial reporting system may enrich firms’ internal audit functions, leading to lesser audit queries. Thus, an effective internal audit in firms may minimise external auditors’ scope of work, leading to the timely release of financial statements. In this way, this research anticipates a negative association between ACI and audit report delay.

Concerning auditor type and financial reporting timeliness, studies reported that companies audited by the Big 4 are more likely to have shorter audit lag because of the efficiency and expertise of these audit firms (Alfraih, Citation2016; Chen et al., Citation2022). These audit firms are more experienced, employ more staff, and have better access to resources and audit technology than their counterparts (Al-Ahdal & Hashim, Citation2022; Basuony et al., Citation2016). So, they are more likely to complete their work faster and thus reducing audit report lag. Therefore, this study expects a negative link between AT and audit report lag.

In addition, several studies argued that profitable companies have timelier financial reporting because disclosing higher profitability is good news to the public (Baatwah et al., Citation2015; Ebaid, Citation2022). In this way, this paper supports a positive relationship between ROA and financial reporting timeliness. It is also stated that larger companies may possess more robust internal control systems because of their track records that external auditors may rely upon, resulting in quicker financial information disclosure (Alfraih, Citation2016; Oussii & Taktak, Citation2018). Thus, a negative association between FS and audit report lag is anticipated. Lastly, leverage may equally influence audit report lag. In this regard, studies reported that creditors pressure firms to embrace high disclosure levels for monitoring (Basuony et al., Citation2016; Ebaid, Citation2022). Thus, high leverage may constrain companies to release their financial position timelier to boost creditors’ confidence in their ability to repay such debts. Consequently, this research expects a negative association between LEV and audit report lag. Hence, Table presents the measurements of these variables as used by prior studies.

5.3. Econometric model and specification

The panel structure of the data at hand makes it imperative for this study to employ the panel data method. Panel data involves an examination of the behaviour of cross-sectional units over many periods (Pesaran, Citation2015; Wooldridge, Citation2002). This methodology is associated with some advantages of generating more data points, reducing multicollinearity, and improving the efficiency of the econometric estimations (Hsiao, Citation1985). The widely used panel data methods include Pooled OLS, fixed and random effects. However, this paper employs a generalised method of moments (GMM) approach, which is relatively stronger than OLS and fixed effects regression methods (Florackis & Ozkan, Citation2009; Habimana, Citation2017). In particular, OLS may yield an inconsistent estimate because the estimator ignores firm-specific effects (Wooldridge, Citation2002). Thus, it may be associated with omitted variable bias. Likewise, the within-group estimator (fixed effects) may be asymptotically biased in the presence of unobserved cross-sectional differences across firms (Bun & Windmeijer, Citation2010).

Importantly, GMM is a dynamic panel data estimator that addresses causality effects and controls unobserved heterogeneity bias using an efficient instrumental variable approach (Arellano & Bover, Citation1995; Ozkan, Citation2001). Also, this regression procedure uses the lag-dependent variable as an instrument and dramatically enhances the consistency of the econometric estimates (Roodman, Citation2009). It is a dynamic approach because the regression method assumes that a dependent variable’s lag value is an important explanatory variable in determining its present behaviour (Habimana, Citation2017). More importantly, many studies argue that corporate governance and financial reporting decisions may be dynamic. OLS and within estimators may be inefficient in a dynamic framework due to the lagged dependent variable and firm-specific effects (Bun & Windmeijer, Citation2010; Ozkan, Citation2000). Thus, it is generally believed that the GMM technique is more suitable for estimating a dynamic relationship between variables over static estimators. Moreover, the panel data set for this research has a short period (T = 10) and larger firm units (N = 102), thereby satisfying the underlying condition for the effectiveness of the GMM estimator.

Furthermore, this research applies the system GMM estimator because it is asymptotically more robust due to employing more efficient instruments. Specifically, this study used the two-step system GMM framework because the estimator utilises the first-step errors to construct more reliable standard errors. Accordingly, the general form of a dynamic model regression is given as:

Where represents the dependent variable in the model for firm i in t time,

is the lagged dependent variable, δ is the adjustment parameter, which is a coefficient value that lies between 0 and 1, the speed of adjustment is given as (1-

),

is the vector of independent variables in the model,

is the firm-specific effect,

is the time effects, and the error term is denoted as

.

Furthermore, by applying the study variables into equation (1), the following model is specified:

6. Results and discussion

The analysis conducted in this study is classified into descriptive analysis, correlation, and regression estimates. Firstly, the descriptive analysis is presented in Table , while the correlation results are demonstrated in Table . Further, Table exhibits the main regression results using the GMM technique, whereas Table displays robustness analysis.

Table 4. Descriptive analysis

Table 5. Correlation results

Table 6. Main regression results (2-step system GMM)

Table 7. Regression results for robustness check (2-step system GMM)

6.1. Descriptive analysis

Table presents the descriptive analysis of the variables under examination. The statistics reveal that the audit report lag (ARL) has an average of 55 days. Also, the ARL has a minimum and maximum of 55 days and 126 days, respectively. The managerial ownership (MO) exhibits a mean of only 2% in the period under review. This result demonstrates that managers’ shareholding among the sampled companies is relatively low. Family ownership (FO) and government ownership (GO) record a mean of 13% and 11%, respectively. Institutional ownership (IO) registers an average of 8% across the firms. The preceding evidence suggests that family and government shareholding dominate the Saudi firms’ ownership structure. The audit committee size indicates an average of four (4) directors in the firms’ audit committees approximately, with a minimum of three (3) and a maximum of five (5) directors. This is consistent with the Saudi corporate governance code, which requires a moderate audit committee size for effective monitoring. According to the statistics, 53% of the firms’ audit committee members are independent directors.

Further, the variable auditor type (AT) shows a mean of 55%. This evidence indicates that Big Four audit firms audit 55% of the Saudi firms, while the non-Big Four audited about 45% within the period under analysis. The companies’ profitability ratio measured by ROA reveals an average of 6% with a maximum ratio of 75%. The variable firm size (FS) has a minimum and maximum percentage of 7.29 and 14.04, respectively. Finally, leverage (LEV) suggests a mean of 0.22 on average, implying that 22% of the firms’ capital represents debt financing.

6.2. Correlation analysis

The correlation results are presented in Table . This analysis was conducted to ascertain the link between the explanatory variables, testing whether a multicollinearity problem exists in the model specification. According to Gujarati and Porter (Citation2010), multicollinearity arises when the correlation between explanatory variables is above 80%. Accordingly, the evidence from Table illustrates that the variables in the specified model are not highly associated with each other. The results show that the highest correlation among the explanatory variables is 58.7% between firm size (FS) and government ownership (GO). Hence, the outcome suggests that multicollinearity is absent in the specified model.

6.3. Regression results

Table presents the 2-step system GMM estimates of the relationship between ownership structure and audit report lag. Notably, the results have satisfied the underlying assumptions for the reliability and validity of GMM estimates. These tests include the Sargan/Hansen statistics and AR (2). The null hypothesis (H0) of the Hansen/Sargan test is that the instruments set are exogenous. Hence, the (H0) can be rejected when the P-value of this statistic is insignificant (Arellano & Bond, Citation1991). Therefore, based on the results in Table , the Sargan statistics appear insignificant and thus, indicating that the GMM instruments used are valid and robust. Also, the second-order test AR (2) condition is there should be no correlation in the disturbance term. Therefore, if the P-value of AR (2) is significant, it shows that the assumption of uncorrelated error terms in AR (2) is violated (Hansen, Citation1982). Thus, a significant p-value indicates some degree of misspecification, demonstrating that the GMM estimate suffers from the second-order serial correlation. Accordingly, the AR (2) p-value in the presented results looks insignificant, implying the specified GMM model does not suffer from the second-order serial correlation. In sum, the GMM results presented in this study appear consistent and efficient.

Furthermore, the model specification shows that the lagged dependent variable (ARLi, t-1) coefficient is positive and significant at the 1% level. This significant result suggests that the specified model is dynamic and confirms that the firms adjust their financial reporting processes to achieve a timelier disclosure (Bazhair & Alshareef, Citation2022; Duru et al., Citation2016). Therefore, the finding confirms the dynamism of corporate financial disclosure in an attempt to comply with financial reporting standards. Turning to the main results, the coefficient of managerial ownership looks positive and significant at the 1% level. The evidence indicates that as managerial ownership rises, the firms’ audit report lag increases. The result is consistent with the argument that high managerial ownership may enhance managerial entrenchment and undermine firms’ internal control systems (Basuony et al., Citation2016; Le & Nguyen, Citation2023; Shan, Citation2019). In this scenario, a weaker internal control may lessen the reliability of external auditors on financial statements of companies with high managerial shareholding. Thus, the evidence implies that external auditors may require greater scrutiny in Saudi firms with high managerial shareholding, leading to high audit report lag.

However, the family ownership coefficient appears negative and significant. The outcome implies that the firms’ financial reporting timeliness may enhance as family ownership increases. This supports agency and stakeholder hypotheses that ownership is an important control mechanism that can improve organisational efficiency (Hasan et al., Citation2022; Manogna, Citation2021; Shleifer & Vishny, Citation1997). The result agrees with the finding that family-controlled firms embrace sound corporate governance to signal the firms’ integrity to outsiders (Al-Bassam et al., Citation2018; Manogna, Citation2021; Waris & Haji Din, Citation2023). In this way, external auditors may require a shorter time to scrutinise the financial records of Saudi family-owned companies, leading to lower audit report lag. In contrast, government ownership is insignificant in influencing Saudi firms’ financial reporting timeliness, thus rejecting H3. The result lends little support to the literature segment, which emphasises that active monitoring of government ownership tends to enhance timelier corporate disclosure (Le & Nguyen, Citation2023; Munisi et al., Citation2014; Wang et al., Citation2011).

On the other hand, the institutional ownership coefficient appears negative. This finding disagrees with Ebaid (Citation2022), who found an insignificant relationship between institutional ownership and Saudi firms’ audit reporting lag. The outcome confirms the agency theory argument that these investors may shape firms’ internal governance because of their sophisticated financial expertise (Bataineh, 2021; Patricia, Citation2022). Also, the result concurs with Basuony et al. (Citation2016) and Alfraih (Citation2016), who reported that careful monitoring from institutional investors might reduce audit report lag significantly. Notably, the finding suggests that institutional ownership may be a robust mechanism that can strengthen the Saudi firms’ internal control systems, and reduce audit queries, leading to quicker release of financial reports.

Regarding the control variables, the regression results strongly reveal that audit committee size and audit report lag are positively related. This finding validates prior studies that argue that smaller audit committees may be more effective in discharging their oversight duties (Boshnak, Citation2021a; Hassan, Citation2016). Therefore, the finding suggests that a smaller audit committee monitoring may be more entrenched in strengthening internal control for a lower audit report lag in the Saudi context. As expected, the audit committee independence coefficient is negative and significant. Hence, the outcome is consistent with studies that found that independent directors in the audit committee may assist firms in designing better policies to remedy their financial reporting weaknesses (Hasan et al., Citation2022; Lajmi & Yab, Citation2022). The evidence implies that as the ratio of independent directors in Saudi firms’ audit committees rises, internal audit functions may improve, resulting in fewer audit queries and lower audit report delays. Concerning auditor type, this study significantly found that Saudi firms audited by the Big Four are more likely to have shorter audit lag. The evidence supports the conclusion that Big Four audit firms are relatively more efficient, employ more staff, and have better access to resources and audit technology than their counterparts (Al-Ahdal & Hashim, Citation2022; Basuony et al., Citation2016). The regression results also reveal that profitable firms have timelier financial reporting because disclosing higher profitability is good news to the public (Baatwah et al., Citation2015; Ebaid, Citation2022). However, the finding in this research insignificantly indicates that firm size and audit report lag are positively associated. This evidence suggests lesser support for the proposition that larger companies may possess more robust internal control systems that external auditors may rely upon, resulting in quicker financial information disclosure (Alfraih, Citation2016; Oussii & Taktak, Citation2018). Finally, this research found a strong positive relationship between leverage and audit report lag. This finding implies that high gearing may prevent Saudi companies from timelier financial reporting. The result contradicts Basuony et al. (Citation2016), and Ebaid (Citation2022), who emphasise that high leverage may pressure companies to release their financial statements timely to boost creditors’ confidence regarding their ability to repay such debts.

7. Additional analysis

Table provides additional regression analysis using logarithms of audit report lag (LOGARL) as a robustness check. This measurement may control outlier and nonlinearity effects, if any, in a specified model (Baatwah et al., Citation2015). The analysis was similarly conducted using the 2-step system GMM.

According to this additional evidence, managerial ownership maintained its positive and significant coefficient, similar to the results in Table . On the other hand, family and institutional ownership remained negative and significantly related to audit report lag, as earlier found. However, government ownership maintained its insignificant effect. Additionally, the control variable demonstrated a similar outcome consistent with earlier regression results. In sum, this research confirms that ownership structure appears to be a significant determinant of Saudi firms’ audit delay using different measures.

8. Conclusion

It is widely believed that corporate ownership is a crucial corporate governance mechanism that can enhance organisational efficiency. However, despite revealing the vital role of corporate ownership in promoting organisational outcomes, only a few studies evaluate the effect of ownership structure on audit report lag. Besides, the bulk of past empirical works on firms’ audit delay determinants wholly employed static estimation and thus ignored the dynamic of financial reporting. The Saudi corporate environment is chosen for this study because enhancing financial reporting quality should be given much attention in the country due to its institutional weakness and absence of an effective market for corporate control. Also, the country’s corporate environment is associated with high government and family ownership and low institutional shareholding. However, some reforms are being undertaken in the country’s corporate sector regarding ownership structure to attract foreign investment. Therefore, this research provided an empirical analysis of the relationship between ownership structure and audit report lag. Using a dynamic framework, the paper sampled 102 Saudi non-financial listed companies from 2012–2021. The dynamic analysis reveals that Saudi firms adjust their financial reporting systems to achieve timelier disclosure. Also, the evidence suggests that Saudi companies with higher managerial ownership may be associated with longer audit delays. However, institutional and family ownership may enhance the financial reporting timeliness of the firms. Moreover, it was found that audit committee size and independence explained Saudi companies’ financial reporting timeliness. Also, the study supports the view that auditor type and profitability may reduce audit report lag. Overall, the results confirm the agency and stakeholder predictions of the relationship between ownership structure and financial reporting timeliness.

This research contributes to the literature by providing a broader empirical analysis of how different ownership monitoring mechanisms may influence financial reporting timeliness. Most importantly, this research provides further insight into the growing literature on the dynamism of financial reporting systems. As such, this study offers more consistent empirical evidence by applying a robust methodology that addresses the endogeneity issue inherent in corporate governance studies.

Moreover, the research findings have some implications for enhancing financial reporting quality. The outcome of this study suggests that in the Saudi context, family and institutional monitoring seems to be an effective control mechanism that may force managers to embrace the timely disclosure of financial reports. Thus, reducing the audit report lag may mitigate information asymmetry, thereby enhancing investors’ confidence. Similarly, regulators and policymakers may find the research outcome helpful in understanding the factors influencing audit report lag. Also, the findings may help regulators redesign corporate governance codes and other stock market regulations for better investment decisions. Finally, as it applies to many studies, this study has some limitations. This study focuses on financial firms. As such, future studies should focus on financial companies to validate the research findings. Even though this research controls for some variables that the literature suggests may influence financial reporting lag, several other factors have not been considered in this study. Therefore, upcoming studies should include other factors influencing audit report lag which have not been included in this study, such as audit fees, audit tenure and board attributes etc. Likewise, similar studies need to be conducted in other emerging economies to investigate factors determining audit delay in a dynamic setting to confirm the findings of this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdillah, M. R., Mardijuwono, A. W., & Habiburrochman, H. (2019). The effect of company characteristics and auditor characteristics to audit report lag. Asian Journal of Accounting Research, 4(1), 129–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJAR-05-2019-0042

- Agyei-Mensah, B. K. (2018). Impact of corporate governance attributes and financial reporting lag on corporate financial performance. African Journal of Economics and Management Studies, 9(3), 349–366. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJEMS-08-2017-0205

- Aksoy, M., Yilmaz, M. K., Topcu, N., & Uysal, Ö. (2021). The impact of ownership structure, board attributes and XBRL mandate on timeliness of financial reporting: Evidence from Turkey. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 22(4), 706–731. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAAR-07-2020-0127

- Alabdullah, T. T. Y. (2018). The relationship between ownership structure and firm financial performance: Evidence from Jordan. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 25(1), 319–333. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-04-2016-0051

- Al-Ahdal, W. M., & Hashim, H. A. (2022). Impact of audit committee characteristics and external audit quality on firm performance: Evidence from India. Corporate Governance (Bingley), 22(2), 424–445. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-09-2020-0420

- Albassam, W. M., & Ntim, C. G. (2017). The effect of Islamic values on voluntary corporate governance disclosure: The case of Saudi-listed firms. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, 8(2), 182–202. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIABR-09-2015-0046

- Al-Bassam, W. M., Ntim, C. G., Opong, K. K., & Downs, Y. (2018). Corporate boards and ownership structure as antecedents of corporate governance disclosure in Saudi Arabian publicly listed corporations. Business and Society, 57(2), 335–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650315610611

- Al Duais, S. D., Qasem, A., Wan-Hussin, W. N., Bamahros, H. M., Thomran, M., & Alquhaif, A. (2021). Ceo characteristics, family ownership and corporate social responsibility reporting: The case of Saudi Arabia. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(21), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112237

- Alfraih, M. M. (2016). Corporate governance mechanisms and audit delay in a joint audit regulation. Journal of Financial Regulation & Compliance, 24(3), 292–316. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRC-09-2015-0054

- Al-Ghamdi, M., & Rhodes, M. (2015). Family ownership, corporate governance and performance: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 7(2), 78–89. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v7n2p78

- Al-Matari, Y. A. (2022). Do the characteristics of the board chairman have an effect on corporate performance? Empirical evidence from Saudi Arabia. Heliyon, 8(4), e09286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09286

- Alregab, H. (2021). The role of corporate governance in attracting foreign investment: An empirical investigation of Saudi-listed firms in liht of vision 2030. International Journal of Finance and Economics, 28(1), 284–294. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.2420

- Alvarez, R., Jara, M., & Pombo, C. (2018). Do institutional blockholders influence corporate investment? Evidence from emerging markets. Journal of Corporate Finance, 53, 38–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2018.09.003

- Alves, S. (2023). The impact of managerial ownership on audit fees: Evidence from Portugal and Spain. Cogent Economics & Finance, 11(1), 2163078. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2022.2163078

- Alzeban, A. (2020). The relationship between the audit committee, internal audit and firm performance. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 21(3), 437–454. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAAR-03-2019-0054

- Ang, J. S., & Ding, D. K. (2006). Government ownership and the performance of government-linked companies: The case of Singapore. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 16(1), 64–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mulfin.2005.04.010

- Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297968

- Arellano, M., & Bover, O. (1995). Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics, 68(1), 29–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-40769401642-D

- Baatwah, S. R., Salleh, Z., & Ahmad, N. (2015). CEO characteristics and audit report timeliness: Do CEO tenure and financial expertise matter? Managerial Auditing Journal, 30(8–9), 998–1022. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-09-2014-1097

- Bajaher, M., Habbash, M., & Alborr, A. (2021). Board governance, ownership structure and foreign investment in the Saudi capital market. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 2(2), 261–278. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRA-11-2020-0329

- Bajary, A. R., Shafie, R., & Ali, A. (2023). COVID-19 pandemic, internal audit function and audit report lag: Evidence from emerging economy. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 2178360. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2178360

- Basuony, M. A. K., Mohamed, E. K. A., Hussain, M. M., & Marie, O. K. (2016). Board characteristics, ownership structure and audit report lag in the middle East. International Journal of Corporate Governance, 7(2), 180–205. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJCG.2016.078388

- Bataineh, H., & Ntim, C. G. (2021). The impact of ownership structure on dividend policy of listed firms in Jordan. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1863175. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1863175

- Bazhair, A. H. (2023). Board governance mechanisms and capital structure of Saudi non-financial listed firms: A dynamic panel analysis. SAGE Open, 13(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231172959

- Bazhair, A. H., & Alshareef, M. N. (2022). Dynamic relationship between ownership structure and financial performance: A Saudi experience. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2098636

- Berger, P. G., Eli, O., & Yermack, D. L. (1997). Managerial entrenchment and capital structure decisions. The Journal of Finance, 52(4), 1411–1438. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1997.tb01115.x

- Boateng, A., Bi, X. G., & Brahma, S. (2017). The impact of firm ownership, board monitoring on operating performance of Chinese mergers and acquisitions. Review of Quantitative Finance & Accounting, 49(4), 925–948. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-016-0612-y

- Boshnak, H. A. (2021a). The impact of audit committee characteristics on audit quality: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. International Review of Management and Marketing, 11(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.32479/irmm.11437

- Boshnak, H. A. (2021b). The impact of board composition and ownership structure on dividend payout policy: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Emerging Markets. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-05-2021-0791

- Bouguerra, A., Hughes, M., Cakir, M. S., & Tatoglu, E. (2023). Linking entrepreneurial orientation to environmental collaboration: A stakeholder theory and evidence from multinational companies in an emerging market. British Journal of Management, 34(1), 487–511. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12590

- Bun, M. J. G., & Windmeijer, F. (2010). The weak instrument problem of the system GMM estimator in dynamic panel data models. The Econometrics Journal, 13(1), 95–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1368-423X.2009.00299.x

- Chen, C., Jia, H., Xu, Y., & Ziebart, D. (2022). The effect of audit firm attributes on audit delay in the presence of financial reporting complexity. Managerial Auditing Journal, 37(2), 283–302. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-12-2020-2969

- Di Vaio, A., Varriale, L., Lekakou, M., & Pozzoli, M. (2023). Sdgs disclosure: Evidence from cruise corporations’ sustainability reporting. Corporate Governance (Bingley), 23(4), 845–866. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-04-2022-0174

- Dobija, D., & Puławska, K. (2022). The influence of board members with foreign experience on the timely delivery of financial reports. Journal of Management & Governance, 26(1), 287–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-020-09559-1

- Durand, G. (2019). The determinants of audit report lag: A meta-analysis. Managerial Auditing Journal, 34(1), 44–75. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-06-2017-1572

- Duru, A., Iyengar, R. J., & Zampelli, E. M. (2016). The dynamic relationship between CEO duality and firm performance: The moderating role of board independence. Journal of Business Research, 69(10), 4269–4277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.001

- Ebaid, I. E. (2022). Nexus between corporate characteristics and financial reporting timelines: Evidence from the Saudi stock exchange. Journal of Money and Business, 2(1), 43–56. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMB-08-2021-0033

- Elhaj, M. A., Muhamed, N. A., & Ramli, N. M. (2018). The effects of board attributes on Sukuk rating. International Journal of Islamic & Middle Eastern Finance & Management, 11(2), 312–330. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMEFM-03-2017-0057

- Fama, E. F., & Jensen, M. C. (1983). Separation of ownership and control. The Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2), 301–325. https://doi.org/10.1086/467037

- Florackis, C., & Ozkan, A. (2009). Managerial incentives and corporate leverage: Evidence from the United Kingdom. Accounting and Finance, 49(3), 531–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-629X.2009.00296.x

- Freeman, R. E. (1994). The politics of stakeholder theory: Some future directions. Business Ethics Quarterly, 4(4), 409–421. https://doi.org/10.2307/3857340

- Gillan, S. L., & Starks, L. T. (2000). Corporate governance proposals and shareholder activism: The role of institutional investors. Journal of Financial Economics, 57(2), 275–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-405X0000058-1

- Gujarati, D. N., & Porter, D. C. (2010). Essentials of econometrics (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

- Habbash, M. (2016). Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosure: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Social Responsibility Journal, 12(4), 740–754. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-07-2015-0088

- Habimana, O. (2017). Do flexible exchange rates facilitate external adjustment? A dynamic approach with time-varying and asymmetric volatility. International Economics & Economic Policy, 14(4), 625–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-016-0341-7

- Ha, N. M., Do, B. N., & Ngo, T. T. (2022). The impact of family ownership on firm performance: A study on Vietnam. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1), 2038417. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2022.2038417

- Hansen, L. P. (1982). Large sample properties of generalised method of moments estimators. Journal of Econometric Society, 50(4), 1029–1054. https://doi.org/10.2307/1912775

- Hasan, A., Aly, D., & Hussainey, K. (2022). Corporate governance and financial reporting quality: A comparative study. Corporate Governance, 5(3), 114–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-08-2021-0298

- Hassan, Y. M. (2016). Determinants of audit report lag: Evidence from Palestine. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 6(1), 13–32. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAEE-05-2013-0024

- Hill, C. W. L., & Jones, T. M. (1992). Stakeholder-agency theory. Journal of Management Studies, 29(2), 132–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1992.tb00657.x

- Hsiao, C. (1985). Benefits and limitations of panel data. Econometric Reviews, 4(1), 121–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/07474938508800078

- Jensen, M. C. (1989). Active investors, LBOs, and the privatisation of bankruptcy. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 2(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6622.1989.tb00551.x

- Jensen, M. C. (1993). The modern industrial revolution, exit, and the failure of internal control systems. The Journal of Finance, 48(3), 831–880. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1993.tb04022.x

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X7690026-X

- Kao, M.-F., Hodgkinson, L., & Jaafar, A. (2019). Ownership structure, board of directors and firm performance: Evidence from Taiwan. Corporate Governance (Bingley), 19(1), 189–216. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-04-2018-0144

- Khlif, H., & Samaha, K. (2014). Internal control quality, Egyptian standards on auditing and external audit delays: Evidence from the Egyptian stock exchange. International Journal of Auditing, 18(2), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijau.12018

- Lajmi, A., & Yab, M. (2022). The impact of internal corporate governance mechanisms on audit report lag: Evidence from Tunisian listed companies. EuroMed Journal of Business, 17(4), 619–633. https://doi.org/10.1108/EMJB-05-2021-0070

- Law, P. (2011). Audit regulatory reform with a refined stakeholder model to enhance corporate governance: Hong Kong evidence. Corporate Governance the International Journal of Business in Society, 11(2), 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1108/14720701111121001

- Ledi, K. K., & Xemalordzo, E. A. (2023). Rippling effect of corporate governance and corporate social responsibility synergy on firm performance: The mediating role of corporate image. Cogent Business & Management, 10(2), 2210353. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2210353

- Le, Q. L., & Nguyen, H. A. (2023). The impact of board characteristics and ownership structure on earnings management: Evidence from a frontier market. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 2159748. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2159748

- Ma, L. (2019). The effect of institutional ownership on M&A performance: Evidence from China. Applied Economics Letters, 27(2), 140–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2019.1610701

- Manogna, R. L. (2021). Ownership structure and corporate social responsibility in India: Empirical investigation of an emerging market. Review of International Business & Strategy, 32(4), 540–555. https://doi.org/10.1108/RIBS-07-2020-0077

- Mitra, S., Hossain, M., & Marks, B. R. (2012). Corporate ownership characteristics and timeliness of remediation of internal control weaknesses. Managerial Auditing Journal, 34(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-06-2017-1572

- Munisi, G., Hermes, N., & Randoy, T. (2014). Corporate boards and ownership structure: Evidence from Sub-saharan Africa. International Business Review, 23(4), 785–796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2013.12.001

- Musah, A., Okyere, B., & Osei-Bonsu, I. (2023). The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on audit fees and audit report timeliness of listed firms in Ghana. Cogent Business & Management, 10(2), 2217571. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2217571

- Ngo, A., Duong, H., Nguyen, T., & Nguyen, L. (2020). The effects of ownership structure on dividend policy: Evidence from seasoned equity offerings (SEOs). Global Finance Journal, 44, 100440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfj.2018.06.002

- Nguyen, H. A., Lien Le, Q., Anh Vu, T. K., & Ntim, C. G. (2021). Ownership structure and earnings management: Empirical evidence from Vietnam. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1908006. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1908006

- Omran, M., & Tahat, Y. A. (2020). Does institutional ownership affects the value relevance of accounting information? International Journal of Accounting & Information Management, 28(2), 323–342. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJAIM-03-2019-0038

- Omri, W., Becuwe, A., & Mathe, J.-C. (2014). Ownership structure and innovative behavior. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 4(2), 220–239. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAEE-07-2012-0033

- Oradi, J. (2021). CEO succession origin, audit report lag, and audit fees: Evidence from Iran. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing & Taxation, 45, 100414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2021.100414

- Oussii, A. A., & Taktak, N. B. (2018). Audit committee effectiveness and financial reporting timeliness: The case of Tunisian listed companies. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 9(1), 34–55. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJEMS-11-2016-0163

- Ozkan, A. (2000). An empirical analysis of corporate debt maturity structure. European Financial Management, 6(2), 197–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-036X.00120

- Ozkan, A. (2001). Determinants of capital structure and adjustment to long run target: Evidence from UK company panel data. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 28(2), 175–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5957.00370

- Patricia, C. (2022). Ownership structure and audit report lag in Nigerian manufacturing companies. Journal of Social Science Research, 1(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4665/4123

- Pesaran, M. H. (2015). Time series and panel data econometrics (1st ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Rajan, R. G., & Zingales, L. (1995). What do we know about capital structure? some evidence from international data. The Journal of Finance, 50(5), 1421–1460. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1995.tb05184.x

- Roodman, D. (2009). How to do xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. The Stata Journal, 9(1), 86–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0900900106

- Sani, A. (2020). Managerial ownership and financial performance of the Nigerian listed firms: The moderating role of board independence. International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting, Finance and Management Sciences, 10(3), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARAFMS/v10-i3/7821

- Sarhan, A. A., Ntim, C. G., & Al-Najjar, B. (2019). Antecedents of audit quality in MENA countries: The effect of firm- and country-level governance quality. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing & Taxation, 35, 85–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2019.05.003

- Setiawan, D., Bandi, B., Kee Phua, L., & Trinugroho, I. (2016). Ownership structure and dividend policy in Indonesia. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 10(3), 230–252. https://doi.org/10.1108/JABS-05-2015-0053

- Shan, Y. G. (2019). Managerial ownership, board independence and firm performance. Accounting Research Journal, 32(2), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARJ-09-2017-0149

- Shao, L. (2019). Dynamic study of corporate governance structure and firm performance in China: Evidence from 2001-2015. Chinese Management Studies, 13(2), 299–317. https://doi.org/10.1108/CMS-08-2017-0217

- Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1986). Large shareholders and corporate control. Journal of Political Economy, 94(31), 461–488. https://doi.org/10.1086/261385

- Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1997). A survey of corporate governance. The Journal of Finance, 52(2), 737–783. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1997.tb04820.x

- Short, H., & Keasey, K. (1999). Managerial ownership and the performance of firms: Evidence from the UK. Journal of Corporate Finance, 5(1), 79–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0929-1199(98)00016-9

- Singh, H., Sultana, N., Islam, A., & Singh, A. (2022). Busy auditors, financial reporting timeliness and quality. The British Accounting Review, 54(3), 101080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2022.101080

- Wang, X., Manry, D., & Wandler, S. (2011). The impact of government ownership on dividend policy in China. Advances in Accounting, 27(2), 366–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adiac.2011.08.003

- Waris, M., & Haji Din, B. (2023). Impact of corporate governance and ownership concentrations on timelines of financial reporting in Pakistan. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 2164995. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2164995

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT Press.

- Yeboah, E. N., Addai, B., & Appiah, K. O. (2023). Audit pricing puzzle: Do audit firm industry specialisation and audit report lag matter? Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 2172013. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2172013