Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced employees to telecommute. Telecommuting has resulted in a work overload in secret places. This has eroded the line between personal and professional life, increasing the risk of conflict. This article reviews the existing research on work-life balance and examines the impact of telecommuting on work-life balance. The study found that work-life interaction and workplace factors influence employee engagement and exhaustion. Work-related expectations, such as emotional and time demands, must be addressed to decrease work-family conflict and create a good work-life balance. This review adds to the body of knowledge by establishing the importance of work-life balance for telecommuting. This review produced two scholarly contributions to work-life balance. Beginning with an overview of existing research topics and organized work-life balance concepts, second, it identified crucial study areas to understand distant work-life balance better. Implications for practice and future research directions are discussed as well.

1. Introduction

Work-life balance is the relationship between a person’s work and life and the point at which the demands of their employment and personal life are equal (Korkmaz & Erdogan, Citation2014; Lockwood, Citation2003). Work-life balance influences the level of work dedication of an employee (Korkmaz & Erdogan, Citation2014).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, it has been observed that the working environment and conditions for workers were becoming more demanding in terms of increasing workload, working under pressure, exposure to violence, and accommodating the wishes of bosses and administration (Ayar et al., Citation2022; Geldart, Citation2022; Yuncu & Yılan, Citation2020). During the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous factors, including irregular working hours, shift working system, role ambiguity, role conflict, lack of occupational safety, excessive or low workload, inadequate wages, and the physical factors arising from the work environment had adverse effects on professionals (Althobaiti et al., Citation2020; Ayar et al., Citation2022; Enli-Tuncay et al., Citation2020). The interrelationship between work and home regarding positive and negative effects is a significant issue for research (Bulińska-Stangrecka et al., Citation2021; Geldart, Citation2022; Lourel et al., Citation2009).

About a decade ago, most employers would have balked at employees regularly working from home. One primary concern most employers had for working remotely was a loss of productivity. According to a pre-COVID-19 pandemic survey by Deloitte, 77% of professionals in the USA have experienced workplace burnout at their current jobs. How far has this number jumped during prolonged lockdowns? However, the COVID-19 pandemic showed that employees could work on their own. Prodoscore, for example, reported that telecommuters’ productivity increased 47% during the lockdown in March and April of 2020, finding that communication activities such as emailing (up 57%), telephoning (up 230%), and chat messaging (up 9%) all climbed.

Other recent studies indicate that telecommuting options increase job satisfaction. Buffer’s 2023 State of Remote Work report found that 91% of survey respondents enjoyed working remotely, with flexibility listed as the most significant benefit. In 2022, McKinsey surveyed 25,000 workers across various industries about their remote work experience. According to the study, seeking out flexible work environments is the third reason people search for new jobs (better pay/hours and career opportunities are the others). Remote work is a significant priority for workers, and 87% of the respondents said they would take it when offered the chance to work remotely.

Two perspectives on work-life balance define this research. The first relates to enhancing personal life, while the second relates to reducing the professional role (Gifford, Citation2022; Sirgy & Lee, Citation2018). The conceptual analysis in this paper focuses on establishing work engagement and minimizing work exhaustion due to role conflict that emerges from telecommuting. As a result, a perspective has been established for this analysis, assuming the necessity of minimizing work-life conflict while providing satisfaction and optimizing the management of resources (Fisher et al., Citation2009).

2. Theoretical review

Several explanations have been presented to explain this phenomenon over the history of the work-life balance discipline. A summary of the theories and models of work-life literature has been summarised in Table . The established studies on work-life balance idea have focused on positive and negative spillover (Zedeck, Citation1992). The Spillover Model proposed by Wilensky (Citation1960); Parker (Citation1971) proposed the Conflict Theory; Boundary Theory based on Nippert’s (Citation1996a) sociological studies on how people reconcile work and home life. Powell and Greenhaus (Citation2006) developed Enrichment Theory to understand how job and family enrich each other. Voydanoff (Citation2004) proposed the Facilitation Theory; Segmentation-Integration Continuum Theory is a paradigm with high role integration and high role segmentation as poles (Guest, Citation2002). Mathew and Natarajan (Citation2014) put forward the Compensation Theory, where they believe that individuals seek compensation in another sphere when they are unfulfilled in one. Based on the idea of scarcity, Resource Drain Theory asserts a negative association between labor and life. The Congruence Theory suggests a similarity between work and family, mediated by genetic, psychological, or sociocultural factors (Zedeck, Citation1992). The Ecological Systems Theory describes work-life balance by looking at the worker’s ecosystem (Pocock et al., Citation2009). According to Bird (Citation2006), the Ladder Theory posits two sides to work-life balance: the individual and the organization. Other approaches, such as Human Capital Theory, Social Identity Theory, and Role Theory, can be gleaned from the literature.

Table 1. Summary of work-life theories/models

We conducted an all-inclusive literature review on work-life balance for this paper. Despite our extensive literature assessment, we narrow our attention to telecommuting and its effect on work-life balance. We have been able to identify significant areas in which further empirical study is needed in the field of telecommuting and WLB. Main arguments and contributions include identifying important areas contributing to better work-life balance among telecommuting employees and examination of vital topics requiring a future study on the issues of personal and professional life balance in telecommuting. Worldwide telecommuting and epidemiological limits need the development of guidelines on how best to sustain a work-life equilibrium when telecommuting from home.

Some articles are “theoretically informed, empirically grounded” in this journal. They talk about how technology has influenced employees in every part, from their jobs to families. As technology has progressed, ideas about “new” have changed. It is essential to encompass a broad opinion of novel innovations. However, at the same time, it is essential to recognize that the ramifications of these inventions are all because of individual actions. To figure out how the current labor process and research on work/jobs have shown these changes over time, we need to look at how these changes have been shown in the past literature. Remembering Marx’s early thoughts is important: “The worker feels himself only when he is not working; when he is working, he does not feel himself. He is at home when he is not working and not at home when he is working.”

This review gives a quick overview of some most important debates going on for a long time that should be looked at again in the modern world. Without wearing rose-tinted glasses and reminiscing, it is vital to be reflective and take a factually and academically informed stance on how technologies will affect the COVID-19 pandemic and the world in the long run. People who know about these things will better understand the current changes as they acclimate to their surroundings.

In the context of the theoretical premises discussed above, it appears important to recognize the changes in organizations’ development processes because of COVID-19 concerning their work-life balance. In a wider sense, there are no facts on definite domains that maintain work-life balance satisfaction for employees telecommuting during COVID-19. Therefore, it is imperative to analyze the broad literature to identify conceptual clusters and recognize which domains need to be improved to provide valued insights on telecommuting.

The sections presented below are an attempt to fill this research gap. A lack of study on the impacts of telecommuting on WLB is addressed in this paper, which proposes a scientific investigation into this matter. This study was motivated by the following research questions:

RQ1.

Does telecommuting affect the work engagement ability of employees in managing their work-life balance?

RQ2.

What are the ramifications of telecommuting on work-related exhaustion?

The article is structured as follows: Section 2 proposes the conceptual background against which this literature was established. Sections 4 and 5 depict the study design and the methodology applied in this research. Section 6 reports the work-life interface. Section 7 analytically discusses the literature findings and expands on this research’s main theoretical and applied significance. The last section presents the conclusions of this study and the directions for further research.

3. Conceptual background

The COVID-19 pandemic and stay-home directives created an unfamiliar terrain for remote work, where many workers had to convert to a new form of work with limited preparation (Bin et al., Citation2021; Geldart, Citation2022). The situation was compounded further by the fact that many workers concurrently had to conduct care obligations (Geldart, Citation2022; Vaziri et al., Citation2020).

Telecommuting is generally adopted from home to ensure consistent delivery of services, adhering to social distance standards provided by national and international health organizations to avert the transmission of this pandemic (Ayar et al., Citation2022; Belzunegui-Eraso & Erro-Garces, Citation2020; Geldart, Citation2022; Palumbo, Citation2020). Besides that, traditional methods that work remotely to address extraordinary challenges create opportunities for many issues that researchers and practitioners still need to recognize.

Although home-based telecommuting has been considered more uncommon in the public sector (Palumbo, Citation2020), the COVID-19 pandemic has made it a common practice for public entities around the globe (ILO, Citation2020). Since research has emphasized that telecommuting activities are emerging among public sectors as well (Langa & Conradie, Citation2003), recent research (De Vries et al., Citation2019; Gifford, Citation2022; Lonska et al., Citation2021; Peters et al., Citation2022; Shirmohammadi et al., Citation2022) asserted that technical alienation and low organizational engagement had eroded the advantages of telecommuting in the public sector. Two significant aspects delineate telecommuting. First, individuals work in addition to their regular work environment; next, a link between office and home exists.

Literature needs to be more consistent when exploring the ramifications of telecommuting on work-life equilibrium. It is believed that remote working, as an adaptable administration of work, improves command over the workplace of representatives, which expands the productivity of operational activities (Breaugh & Farabee, Citation2012). In light of this strong cognition of the dedication to work and the opportunities to work in an accustomed and comfortable environment, people who work away from home face more productive and fewer working life conflicts (Lonska et al., Citation2021; Mas-Machuca et al., Citation2016). In addition, as an employee-based human resource exercise, it is widely recognized that home-based telecommuting can limit the feeling of strain between private life and employment and thereby enhance the equilibrium between lives and work (Beauregard & Henry, Citation2009; Belzunegui-Eraso & Erro-Garces, Citation2020; Lonska et al., Citation2021; Mas-Machuca et al., Citation2016). Subsequently, this equilibrium has immediate and circuitous beneficial outcomes for organizations, including enhanced social trading initiatives, less turnover, and expanded profitability (Beauregard & Henry, Citation2009; Lonska et al., Citation2021; Palumbo, Citation2020). An alternate view is that telecommuting is an institution-based HR exercise that reduces operating expenses. Instead of giving employees better command over the interface of work and life, work from home incorporates increasing work intensity (Kelliher & Anderson, Citation2010) and expands managers’ technical control over telecommuters (Bathini & Kandathil, Citation2020; Palumbo, Citation2020; Uqba & Bhat, Citation2020).

Telecommuting also determines disengagement between telecommuters and traditional office workers, creating a negative inclination towards personal work errands (Collins et al., Citation2016). This is particularly relevant when telecommuting is embraced in response to unpredictable and catastrophic events, such as unforeseen and disaster situations (Ayar et al., Citation2022; Mas-Machuca et al., Citation2016, Palumbo, Citation2020; Weale et al., Citation2019). To argue, telecommuting is expected to have some detrimental effects on telecommuters’ working conditions, which can adversely impact their work-life balance (Belzunegui-Eraso & Erro-Garces, Citation2020; Lonska et al., Citation2021; Troup & Rose, Citation2012) needs to be evaluated. Another disadvantage of telecommuting is acclimating people to the organization’s culture and socializing and control procedures (Popovici & Popovici, Citation2020).

Furthermore, will working remotely decide work expansions and the overlap between work obligations and personal life (Hyman & Baldry, Citation2011)? Can this cause more disruption between personal lives and work, which, rather than avoidance, will prompt clashes in work and life (Mas-Machuca et al., Citation2016)? Will the likelihood of working from home enhance workers’ independence and their inherent drive (Mas-Machuca et al., Citation2016), while telecommuters might have an increased devotion and react with “extra” work commitment? There needs to be more uniformity in the research when analyzing the influence of telecommuting on work-life equilibrium (D’Andrea, Citation2022; Palumbo, Citation2020). Examining the detrimental effects of telecommuting on work-life balance reveals empirical evidence that it reduces job engagement . Telecommuting can disrupt the work-life balance by lengthening actual work hours and overlapping personal and professional responsibilities (Hyman & Baldry, Citation2011). Additionally, it may result in intense friction amid work and non-work responsibilities, detrimental to work-life balance (D’Andrea, Citation2022; Fonner & Stache, 2012; Geldart, Citation2022; Palumbo, Citation2020). Given that research indicates that telecommuting has a detrimental effect on work-life equilibrium (Felstead & Henseke, 2017), it becomes essential to ascertain the elements which impact work-life balance.

There is a dearth of evidence on specific domains of workers who telecommute during COVID-19 in maintaining satisfying work-life stability. Therefore, to put up an argument, it is critical to conduct a literature review to determine theoretical clusters and determine which areas require further development to provide valuable recommendations on telecommuting.

4. Methodology

This article does bibliometric analysis utilizing VOS viewer and the Scopus database tools. Recent advances in bibliometric software and scientific databases like Scopus and Web of Science and cross-disciplinary pollination of the bibliometric methodology from information science to business research have increased the popularity of bibliometric analysis in business research (Donthu et al., Citation2020).

Bibliometric analysis is still relatively new in business research, and its application must often catch up to its full potential. This happens when bibliometric studies use a limited selection of data and procedures to create a fragmented knowledge of the area (Brown et al., Citation2020). Unauthoritative guides to bibliometric analysis in business research must be improved, posing a substantial obstacle to business researchers seeking to learn more about bibliometric methodology and its use for business research. Although authoritative instructions on systematic literature review exist (Palmatier et al., Citation2018; Snyder, Citation2019), they need bibliometric technique breadth and depth. This is because reviews commonly present the performance of different constituents of research (e.g., countries, institutions, authors, and journals) in the field, which is similar to the profile or background of participants in empirical research but more analytical.

The scope of the study should be substantial enough to support bibliometric analysis (Ramos-Rodrigue & Ruz-Navarro, Citation2004). Scholars might assess the number of papers available in the targeted research field to establish the study’s breadth. Bibliometric analysis can be used if a research field has hundreds (500 or more) or thousands of papers. The search for peer-reviewed publications was conducted on 13 January 2022 in Elsevier Science Scopus. The Scopus database provides a wide-ranging, high-quality list containing social-sciences information for this analysis. As per Elsevier, Scopus is the largest database of quotations and summaries from peer-reviewed research literature. The bibliometric review described in this article is primarily based on the database of Scopus and a randomly chosen sample of articles that contain the key phrase “Work-life balance.” The category “Business, Management, and Accounting” was chosen to include articles on work-life balance solely. 1026 papers were exported and used for further research from 2010 to 2020. The bibliometric analysis employed the following techniques: the co-occurrence of words and cluster analysis and the mind-mapping approach. The VOS viewer, XMind, and data-analysis tools accessible in the Scopus database were also utilized. The primary search yielded the identification of 1026 sources in our literature evaluation.

5. Results

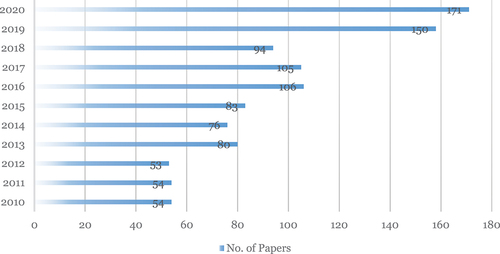

This part summarizes the findings of a review of the identified papers during our search for “work-life balance.” The motivation to research work-life balance studies continues to grow year after year. Figure depicts the annual number of publications released between 2010 and 2020. As of 2010, there were only 50 publications on this subject, increasing to 106 in 2016 and 171 in 2020. The growing research in WLB results from an increased focus on the employee’s demands in the organization and when telecommuting from home.

Figure 1. Number of publications from 2010–2020 on work-life balance..

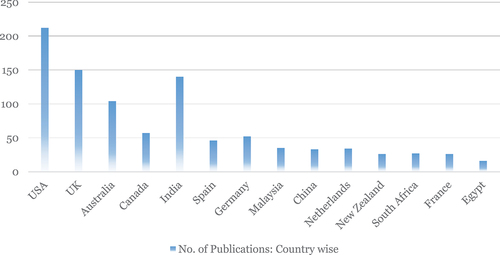

Geographically, research in the examined area was diverse. As illustrated in the following figure (Figure ), this subject received the most attention from scholars in the USA, UK, Australia, Egypt, and India. Two hundred and twelve articles were published in the USA. Canada, Spain, and Germany are among the countries where approximately 50 papers have been published. Figure depicts country-wise publications between 2010 and 2020. WLB is a subject taken up by researchers from 51 countries.

Figure 2. Country-wise no. of publications on work-life balance.

The top 8 journals that have the most articles in them are shown in this order: Personnel Review (31-publications), International Journal of Human Resource Management (42-publications), Human Resource Management (23-publications), Work Employment and Society (27-publications), Gender Work and Organization (22-publications), Employee Relations (21-publications), and Gender in Management (22-publications) are the top eight journals with the most publications (See Table ). Every one of the 1026 papers analyzed is a scientific article.

Table 2. List of journals that published research on work-life balance 2010 – 2020

The next phase in the literature analysis process was to create a plot of the co-occurrence grid. The preliminary procedure of text data analysis in VOS reader created 20,324 cumulative terms, comprising the title, keywords, and abstract text. All words with fewer than 10 talks were then eliminated. Just 811 circumstances met this criterion. Based on the VOS viewer’s hit ratings, we devised computations for the degree to which a cut-off date is specific, valuable, vague, and non-useful (Van Eck et al., Citation2013). The results scoring in the top 50% of relevance ratings were chosen, lowering the total items to 463. The results were then manually reviewed to eliminate any references to the research process (e.g., keywords, article, date, author, Scopus) or nations like India, Germany, Egypt, or the United Kingdom. After eliminating such broad terms, we were left with 242 results.

6. Work-life interface

The work-life interface is the meeting point for non-work and work spheres. Numerous, at times contradictory, notions of work-life interaction have been employed in prior studies (Guest, Citation2002; McMillan et al., Citation2011). For instance, work and life equilibrium, coordination, interaction, etc., are all notions about work-life interaction. These ideas are frequently used reciprocally. McMillan et al. (Citation2011) state that they must be appropriately elucidated and inferred before they can be employed efficiently to improve the management of human resources. Due to the need for more generally accepted explanations for work-life interface-related ideas, numerous attempts have enumerated its various factors. While work-life conflict measures have typically been engaged to review the work and live interaction, some scholars have noted that the two concepts are distinct (Ayar et al., Citation2022; D’Andrea, Citation2022; Geldart, Citation2022; Gifford, Citation2022; Lonska et al., Citation2021; McMillan et al., Citation2011; Peters et al., Citation2022; Shirmohammadi et al., Citation2022; Uqba & Bhat, Citation2020).

McMillan et al. (Citation2011) presented a helpful outline for understanding the links between the factors affecting work-life interaction. They maintained that work-life conflict and enrichment affect work-life harmony (as they coined the term). Thus, work-family conflict is not an antonym for work-life equilibrium in their concept; instead, it adds to work-life fit. We used the term “work-life balance” interchangeably with “work-life harmony” as defined in the McMillan et al. (Citation2011) model. Two measures of the work-life interface were used in this study: work-family conflict (WFC) and work-life balance (WLB).

Work-family conflict (WFC) is a word that refers to a situation in which the overall demands of the job, the time commitment required, and the strain generated by the employment intermingle with personal life (Frone et al., Citation1992). Work-family conflict quantifies how much the work harms an employee’s life outside of the job, and an increased work-family conflict is often connected with unfavorable results (Allen et al., Citation2012). Most research on the effect of work-family conflict on worker performance has focused on regular employees and has discovered that long working periods are associated with high levels of work-family conflict, which can harm health (Ahmed et al., Citation2013; Mas-Machuca et al., Citation2016). Additionally, research has examined associations between job satisfaction and work-family conflict (Ahmed et al., Citation2013; Bruck et al., Citation2002) and associations between work-family conflict and turnover intentions (Bruck et al., Citation2002).

Work-life balance (WLB) is defined in this study as a comprehensive assessment of an employee’s perceived ability to handle several life spheres—e.g., non-work and work spheres—in such a way that they complement rather than compete, regardless of the resources or time allotted to each (Guest, Citation2002; Timms et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, it encourages telecommuters’ work-related passion, commitment, and enthusiasm, owing to greater control in managing individual working environments. Work-life balance is one aspect of the general work-life fit aspect. Poor WLB, or the inability of personal and professional domains to coexist together, is a persistent issue in workplaces throughout the globe. Work-life balance issues persist—notwithstanding recent revisions in employment rules granting certain employees the right to flexible work environments and leave—and are especially problematic for working mothers and caregivers (Ayar et al., Citation2022; Shirmohammadi et al., Citation2022; Skinner et al., Citation2014). Despite alterations in the workforce structure and an increased female labor force participation, diverse patterns of work and caregiving persist—males are viewed as wage earners, while women are viewed as caregivers. Due to this gendered model, women experience bad work-life outcomes at a higher rate than their counterparts, irrespective of the number of hours they have worked (D’Andrea, Citation2022; Geldart, Citation2022; Skinner et al., Citation2014). There is a considerable dispute concerning the term “balancing” (Timms et al., Citation2015; McMillan et al., Citation2011; Guest, Citation2002) and whether it is desirable or attainable to balance work and non-work realms. Certain employees may be content with their work and life equilibrium; they may devote more energy to one of the spheres than the other at different phases of their lives. The work-life imbalance has been linked to various undesirable outcomes, including job burnout and decreased job satisfaction (Greenhaus et al., Citation2003; Guest, Citation2002).

A healthy work-life balance is crucial for sustaining job engagement; it may even lengthen professional life and postpone superannuation (Atkinson & Sandiford, Citation2016). According to Skinner et al. (Citation2014), various practices and policies are required to promote employee engagement and participation across the life course. Hence, the focus should be on practices and policies that facilitate the effective interplay of personal and professional realms. On the contrary, researchers concluded that the proof for an association between employee engagement and WLB is mixed, implying that other organizational aspects, such as career advancement prospects or succession planning policies, may have a more significant impact on employee engagement and turnover intentions than work-life fit (Parkes & Langford, Citation2008).

Organizations must implement such programs and policies to handle work-life interaction to increase the interface between professional and personal areas. According to Zheng et al. (Citation2015), employees’ usage of such initiatives and policies coexists with their tactics for juggling competing areas of their life. A better understanding of the work-life interface enables the management to affect individual and organizational outcomes in ways that traditional workplace-centric approaches do not and is an important subject that warrants additional study. Additionally, research has concentrated on the issues of telecommuting as an employee-selected mode of work. However, more attention must be paid to telecommuting due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which requires employees and employers to adapt to new working methods.

The majority of studies on Work-life balance and telecommuting have been quantitative. These studies include statistical data analysis from extensive international surveys (Germany, the USA, and the UK) or the European Working Conditions Survey. Despite their publication year of 2020, the surveys analyze statistical data from 2015 to 2016, omitting the distant working conditions induced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Studies examining the impact of life work on work-life balance have also documented the disadvantages of such work arrangements. These findings indicate that telecommuting harms employees’ work-life balance (Palumbo, Citation2020). Additionally, they believe that telecommuting makes it much more difficult for employees to unplug and take breaks, undermining work-life balance in the long run (Burke & El‐Kot, Citation2010; El-Kot et al., Citation2021; Felstead & Henseke, 2017; Leat & El-Kot, Citation2022). Moreover, research posits a risk of exacerbating the role conflict due to familial and professional responsibilities (Eddleston & Mulki, Citation2017; Lonska et al., Citation2021; Peters et al., Citation2022; Thulin et al., Citation2020). The findings of this research underscore the importance of developing clear employee policies to accommodate remote workers (Burke & El‐Kot, Citation2010; El-Kot et al., Citation2021; McDowall & Kinman, Citation2017).

To conclude, research on the connection between telecommuting and work-life balance must demonstrate organizations’ difficulties in providing an adequate support structure for employees. The work intensification, increased time spent in front of the laptop, more significant role conflict, and the consecutive burden of technological overwork are all real issues related to telecommuting. As a result, it is critical to discover potential solutions to these difficulties through suitable management techniques in firms.

6.1. The ramifications of telecommuting on work-life balance (WLB)

The ramifications of telecommuting on the balance of life and work are being examined in the literature, contending that telecommuting probably increases the versatility of working operations, which enhances the balance of work and life (El-Kot et al., Citation2021; Sullivan, Citation2012). However, it is stressed that the merits of working from home are questionable since they solely rely on social and economic factors (Aguilera et al., Citation2016; Bloom et al., Citation2015). Telecommuting can prompt a few drawbacks, which concerns both disabled administrative exposure because of a de-contextualization of working practices (Gifford, Citation2022; Lonska et al., Citation2021; Maruyama & Tietze, Citation2012; Mas-Machuca et al., Citation2016; Uqba & Bhat, Citation2020) and an imbalance between personal matters daily and work responsibilities (Allen et al., Citation2012).

The capacity of telecommuters to explore the work-life interface is adversely affected by tainting between work and life. Home-based telecommuting, on the one hand, can trigger an “illusion of time flexibility” in other members of the family, who might perceive that time expended at home can be utilized for family output without deviating from the duration of paid labor (Ayar et al., Citation2022; D’Andrea, Citation2022; Palumbo, Citation2020; Weale et al., Citation2019). The collocation of personal affairs and job-related obligations creates tension and time distribution, which sabotages the benefits of telecommuting in terms of life and work equilibrium and fosters contradictions between life and work (Wheatley, Citation2012).

On the other hand, home-based telecommuting involves both an imposed and a deliberate work escalation. In particular, the work intensity is achieved with the consent of telecommuters, which exchanges greater task versatility with more outstanding work commitment (Kelliher & Anderson, Citation2010). Speeding up efforts can lead to work-life conflicts when combined with an impaired capacity to turn off work as it perpetuates the onslaught of work-related issues in daily life (Felstead & Henseke, 2017; Palumbo, Citation2020). In short, home-based telecommuting has a few detrimental impacts on employees’ capacity to successfully manage work-life interaction, leading to stress on work-life equilibrium.

6.2. Telecommuting and work engagement

Home-based telecommuting eliminates the tension induced by overlapping work and family requirements (Palumbo, Citation2020) and increases the equilibrium in telecommuters’ lives, entailing lower psychological and physical discomfort levels. Work-related passion, dedication, and enthusiasm enhance job contentment (Karatepe & Demir, Citation2014; Mas-Machuca et al., Citation2016) and augment employees’ optimistic self-assessment, which in turn increases the thrill of the individual’s capacity to handle the interrelationships between life and work (Lu et al., Citation2016). Work engagement is of great interest among researchers studying work-life balance. The study covers the employee’s work-life balance activities, which will assist the individual in continuing with the organization through career advancement opportunities and training (Peters et al., Citation2022; Sheehan et al., Citation2019; Shirmohammadi et al., Citation2022). The analysis focused primarily on the effect of work-life balance on employee engagement, which resulted in enhanced job outcomes (Ayar et al., Citation2022; D’Andrea, Citation2022; Dilmaghani, Citation2020; Hutagalung et al., Citation2020; Lonska et al., Citation2021), organizational commitment (Oyewobi et al., Citation2020), and supervisor support (Rahim et al., Citation2020). To build a better work-life balance, home telecommuting is the latest working method that enables workers to harmonize family and work-related commitments’ (Morgan, Citation2004). Therefore, home-based telecommuting is supposed to positively impact work commitments (Uqba & Bhat, Citation2020). Work commitment is generally a healthy, stable, and satisfying state of mind linked to work marked by vitality, commitment, and immersion (Mas-Machuca et al., Citation2016; Palumbo, Citation2020). Although scholars are skeptical about the potential benefits of home-based telecommuting related to work commitment (Liao et al., Citation2019), it has been upheld that at the end of the day, telecommuting can mitigate the sense of fatigue (Ayar et al., Citation2022; Mas-Machuca et al., Citation2016; Peters et al., Citation2022; Shirmohammadi et al., Citation2022; Uqba & Bhat, Citation2020; Weale et al., Citation2019). The perception of work-life clashes caused by the corrosion of job-related activities and domestic responsibilities is expected to be minimized by increased work participation (Ayar et al., Citation2022; Gifford, Citation2022; Palumbo, Citation2020; Van der Lippe & Lippenyi, Citation2020).

6.3. Telecommuting and work-related exhaustion

The studies suggest that home-based telecommuting can reduce work-related exhaustion by eliminating daily commuting (Anderson et al., Citation2001; Ayar et al., Citation2022; D’Andrea, Citation2022; Lonska et al., Citation2021). As it considers work obligations in the day-to-day setting, working from home can prompt an inadvertent convergence of work-related obligations and family exercises, escalating the feeling of weariness among employees working remotely (S.-N. Kim et al., Citation2015; Mas-Machuca et al., Citation2016). Telecommuting induces expansion and intensification of work, which contributes to maximizing the work-related endeavors of telecommuters (Heiden et al., Citation2018), henceforth leading to more exhaustion. This impedes the benefits of telecommuting in terms of greater versatility in organizing work (Palumbo, Citation2020; Vesala & Tuomivaara, Citation2015; Weale et al., Citation2019).

The higher the commitment of telecommuters to work, the better their perspective toward the job (Zheng et al., Citation2015). Subsequently, they will understand work-related exhaustion less (S. Kim et al., Citation2018; Palumbo, Citation2020; Uqba & Bhat, Citation2020). To wit, work-related passion, determination, and enthusiasm increase workers’ ability to recuperate from exhaustion and increase the employee’s ability to enhance work-life fit by job redesigning (Lu et al., Citation2014). A substantial opportunity to incorporate nonworking and working exercises conversely allows recuperation from work-related exhaustion (Ayar et al., Citation2022).

Perceived exhaustion undermines the capacity of workers to effectively handle work-life interactions, jeopardizing the equilibrium of life and work. Home-based telecommuting may increase the urge to work during irregular hours, like evenings or day-offs (Ayar et al., Citation2022;; Geldart, Citation2022; Lonska et al., Citation2021; Weale et al., Citation2019). Indeed, this can adversely affect the telecommuters’ work-life equilibrium (Weale et al., Citation2019). As previously expected, work participation requires greater fatigue tolerance and greater work demands, decreasing the detrimental impacts of exhaustion on the apparent work-life balance (Garcıa-Sierra et al., 2016; Palumbo, Citation2020).

7. Discussion

The review above of the literature made scientific contributions to the work-life balance idea. First, it summarized existing study domains and structured work-life balance conceptualizations and conducted a literature review to determine theoretical clusters and which areas require further development. It became essential to ascertain the elements which impact work-life balance. This study also established that telecommuters might have an increased devotion and react with “extra” work commitment. Working remotely can decide work expansions and the overlap between work obligations and personal life. It also suggested critical areas for more research to better understand work-life balance in remote work situations. Additionally, it included a collection of prescribed endorsements for additional development and work-life balance research.

As many scholars have argued, the shifts in work, work, and non-work patterns during this time have affected employees’ work-life balance, which, in turn, impacted employees’ adaptation to and satisfaction with remote work and their work performance (Ayar et al., Citation2022; Burk et al., Citation2021; Carillo et al., Citation2021; D’Andrea, Citation2022; Geldart, Citation2022; Gifford, Citation2022; Lonska et al., Citation2021; Peters et al., Citation2022; Shirmohammadi et al., Citation2022). Telecommuting has an adverse influence on employees’ work-life balance. While remote working has been widely viewed as a means of attaining a more balanced WLB through increased flexibility in work arrangements, the intersecting of work obligations and personal concerns that results from telecommuting have a detrimental effect on employees’ ability to maintain a healthy balance amid professional and personal life (Crosbie & Moore, Citation2004; Felstead et al., Citation2002). This is particularly factual for employees exposed to familial responsibilities, like old parents and caregivers for aged ones (Wheatley, Citation2012). Telecommuting facilitates both work-life and life-work clashes, jeopardizing employees’ ability to manage the interaction of job and life (Visser & Williams, Citation2006). This demonstrates the inherent inconsistencies of remote work, which may jeopardize instead of improving employee WLB (Johnson et al., Citation2007).

Despite these concerns, telecommuting from home had a beneficial effect on the job engagement of telecommuters. Individuals who worked from home demonstrated increased concentration levels, devotion, and vitality (Palumbo, Citation2020). Their perceived organizational support facilitates telecommuters’ greater work engagement, often connected with work arrangement flexibility (Jin & McDonald, Citation2017). Additionally, job engagement occurs due to a good match between individual requirements and organizational standards, improving individual commitment (Zafari et al., Citation2019).

Work engagement alleviates the sense of conflict and inconsistency among job-related obligations and daily life (Bakker & Leiter, Citation2010). It is considered to mitigate the perceived severity of life-work and work-life conflicts and promote organizational commitment from this vantage point (Al Mehrzi et al., Citation2016). In other words, work engagement mitigates the detrimental effects of remote working on WLB by sustaining the self-reported ability of employees to handle conflicts (Ayar et al., Citation2022).

It is worthwhile to note that telecommuting entailed broadening and deepening work. Home-based telecommuting is frequently associated with an overworked culture (Walsh, Citation2005), which fosters increased workload and increases work-related fatigue (Tremblay, Citation2002). On the other hand, work-related fatigue suggests a diminished capacity of an individual to handle workload due to severe time constraints, undermining his WLB (Nilsson et al., Citation2017). According to these views, work exhaustion has a detrimental effect on the interaction between remote working and WLB, resulting in more conflicts amid personal and work responsibilities (Kossek et al., Citation2013).

Work involvement entails a more favorable view of work among those who telecommute, facilitated by a more outstanding commitment to work-related responsibilities (Muller & Niessen, Citation2019). By enhancing personal views of job self-efficacy, job engagement can lower perceived work-related weariness and mitigate the emotional and physical exhaustion associated with remote working from home (Fujimoto et al., Citation2016). Work engagement and work-related weariness were discovered to be mediators of the effects of serial telecommuting on WLB, reducing perceptions of life-work and work-life conflicts induced by the overlap of work-related tasks and daily routines (Palumbo, Citation2020). As Bierema (Citation2020) argues, the disruptions brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic offer a unique opportunity for HRD scholars and practitioners to redesign organizational, developmental, and leadership solutions and articulate remote employees’ concerns and demands. Scholars have asked for more inclusive studies highlighting the problems and experiences that impact remote employees’ work-life balance, well-being, and job results (Bolino et al., Citation2021).

Regarding workplace engagement in remote working conditions, the literature study results corroborate actual studies on people telecommuting during COVID-19, suggesting that telecommuting—particularly at the start—considerably boosts job satisfaction (Hashim et al., Citation2020). Another significant difficulty is keeping employees engaged during remote work hours (Pattnaik & Jena, Citation2020). Given that engagement is one of the work-related outcomes of work-life balance, an additional study should examine processes that reinforce work-life balance to develop engaged remote workers.

Technology is critical in promoting work-life balance in remote working environments. As the empirical studies on telecommuting have demonstrated, technology can improve communication with co-workers and allow supervisors to watch work closely (McDowall & Kinman, Citation2017; Popovici & Popovici, Citation2020). Assuring employee socialization through the appropriate use of technology is critical for improving the work-life balance for remote workers (Ayar et al., Citation2022; Dolot, Citation2020). This is especially important given that study indicates that workers felt isolated and depersonalized during COVID-19 (Almonacid-Nieto et al., Citation2020). Employee engagement is critical to work-life balance research, significantly impacting productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic.

We set out to study work-life balance and its relationship with engagement and fatigue and learned these new things that contribute to this field. This review establishes the critical nature of the work-life interaction, more precisely, work-life balance and work-family conflict, for telecommuters. It is critical to developing comprehensive models that conceptualize the links between non-work and work elements and consequences to properly comprehend how places of work might affect work engagement, job satisfaction, and fatigue.

7.1. Implications for practice

Work design is critical to increasing performance, employee engagement, and job satisfaction among employees. Historically, job design has placed a premium on job qualities like autonomy and relevance of work activities.

However, this review demonstrated the critical role of work-life interaction and workplace characteristics in determining employee engagement. Work engagement may be increased by minimizing workplace stressors and aiding employees in achieving a satisfying fit among non-work and work realms. Researchers observed that both the availability and utilization of organizational initiatives that aid employees in managing work-life balance aid employees in minimizing their stress levels (Zheng et al., Citation2015). Specific work practices, such as giving employees more discretion over when they work and how many hours they work, have been demonstrated to enhance work-life balance, resulting in beneficial outcomes for employers and employees (Ayar et al., Citation2022; Shirmohammadi et al., Citation2022; Weale et al., Citation2019).

Achieving a healthy work-life balance requires dealing with work-related expectations, such as emotional and time pressures, which can help reduce work-family conflict and promote a healthy balance of work and life. HR managers should leverage this in their employment strategies and continue fostering practices and policies that support a healthy work-life balance, such as allowing more employees in different roles to utilize flexible time schedules, such as resident and shift changes. Additionally, augmenting the number of employees in a facility may improve shift liability. However, it should not be possible owing to the associated expenses or difficulties in hiring rightly skilled personnel for specific tasks. Another strategy to facilitate a robust work-life balance is practices and policies that foster an accommodating work environment. To assist staff in coping with emotional demands associated with remote work, consideration should be given by recognizing the difficulties inherent in this line of work and executing such policies which warrant employees to refrain from requiring outside help for demands related to work. This is another way to enhance work-life balance.

8. Conclusion

Work mobility allows for greater flexibility in managing work and personal responsibilities, resulting in a better work-life balance for employees. This balance benefits both the organization and its employees. Past reviews have given us a good look at how the literature has changed eventually (Baldry, Citation2011). This review could have been more wide-ranging. Instead, it has focused on improvements in technology and employment concerning this COVID-19 pandemic. This review has then explained how these issues affect people working from home. We are still determining if there will be substantial modifications to how work will be organized and managed or if it will remain the same. The fact is that whether people work in physical places or at home, papers in this journal can help with this critical question. There have been more debates recently about what the future of work will look like and how artificial intelligence will change jobs.

However, we do not have to limit ourselves by how we think now. Another way is possible. In the wake of the COVID-19 crisis, there is a chance to look at the future of work differently. We can look at talent and work value differently (Martinez et al., Citation2020; D’Andrea, Citation2022; Lonska et al., Citation2021; Peters et al., Citation2022). As per Winton and Howcroft (Citation2020), “In light of the current crisis, a radical re-think of how labor is valued—both socially and financially—is needed, leading to policies which ensure that key workers are paid and protected in a way that reflects their critical contribution to society.”

This review emphasizes from a philosophical point of view that telecommuting can restrict the ability of employees to manage their interaction between life and work. Telecommuting nurtures role uncertainty by blurring the limits between work obligations and private exercises, furthering work and life conflicts. This convergence of work and life can make remote workers feel fatigued as it creates intensification and expansion of work and non-work endeavors. Notably, people who are deeply committed to work might be unconscious of the infringement of work in their daily lives.

From a realistic perspective, the structure of resilient work practices which allow employees to telecommute requires a detailed analysis of the interaction between life and work. Tailored steps need to be taken to prevent working life issues into daily life practices from the greater autonomy of workers over the spatial-temporal sense of work. This is particularly true for certain types of individuals that show a greater sense of concentration, vigor, and commitment associated with work. In reality, workers with a strong job commitment are likely to ignore the work-life one-sidedness created by telecommuting, making them vulnerable to work overload and fatigue.

This review also indicates that telecommuting will intensify the employee’s sensation of work-related exhaustion by adopting a managerial angle. Currently, at irregular periods, it requires a significant eagerness to work, which can be the tacit consequence of the failure of telecommuters to handle the interface of work and life. Explicit HRM strategies adapted to the exigency of telecommuters should be developed to cope with this situation, understanding the unique challenges that impact the activities and outcomes of individuals operating remotely from home.

8.1. Contributions

First, it comprehensively reviews the links between work-life balance variables. The study of these constructs is novel, as no prior work has sufficiently considered these interactions. We broaden our perspective on WLB’s effects by evaluating whether employees’ WLB promotes work engagement and work-related exhaustion. Second, the review has practical implications for businesses considering work-life policies. Flexible working hours, employee sovereignty in decision-making, employee engagement, and supervisor support also increases employee WLB. Lastly, it suggested critical areas for more research to enrich the knowledge of work-life balance in remote work situations (See Table ).

Table 3. Key insights of the study

8.2. Limitations and future research directions

Acknowledging the potential limitations of pre-pandemic data is crucial when examining the lessons that can be learned from pandemic telecommuting. The distinct nature of pandemic telecommuting, compared to telecommuting before or following the COVID-19 pandemic, demands a comprehensive understanding of its unique challenges and implications. During lockdowns, many employees were abruptly forced to transition to remote work, facing unprecedented difficulties. One significant aspect to consider is the psychological and physical distress experienced by individuals during the pandemic telecommuting. The sudden shift to remote work, often without adequate preparation or suitable workspaces, resulted in heightened stress levels, isolation, and burnout. The blurred boundaries between work and personal life further exacerbated these challenges. Exploring the long-term effects of such psychological and physical distress on employees’ well-being is essential for developing strategies to mitigate these negative consequences.

Furthermore, illness, whether due to COVID-19 or other health issues, played a central role in shaping employees’ experiences during the pandemic. Research should investigate the impact of illness on productivity, work-life balance, and overall job satisfaction. Understanding individuals’ strategies to navigate these challenges and identifying effective support systems will contribute to future telecommuting policies and practices. Caregiving responsibilities emerged as a significant burden during the pandemic, telecommuting, with many employees simultaneously juggling work and caregiving duties. The closure of schools and childcare facilities placed additional strain on parents, particularly mothers, who faced increased demands on their time and energy. Examining the challenges caregivers face during the pandemic and identifying ways to facilitate a better balance between work and caregiving responsibilities will be crucial for promoting gender equality and fostering inclusive work environments.

While the insights gained from the pandemic can inform our understanding of telecommuting, it is important to recognize that these findings may not exclusively apply to pandemic telecommuting alone. Future research should track the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on employment patterns and work arrangements. This includes studying the sustainability and scalability of telecommuting models, the potential impact on job opportunities and income disparities, and the implications for urban planning and transportation infrastructure. Moreover, investigating worker safety and health in telecommuting is essential. It understands the ergonomic challenges of remote work setups, evaluates the effectiveness of digital tools and communication platforms in promoting collaboration and well-being, and identifies best practices for maintaining a healthy work environment at home that warrants further exploration. Future research should delve into the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on employment patterns, work arrangements, and workers’ safety, health, and well-being.

By addressing the limitations of pre-pandemic data and considering the unique challenges faced during pandemic telecommuting, we can gain valuable insights to inform policies, practices, and support systems for remote work in the post-pandemic era.

Highlights

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted an individual’s day-to-day life while working from home.

Individuals compromised both on official as well as on social/personal fronts.

This study explores the ramifications caused due to work from home and its impact on the work-life balance.

An extensive but precise review of the adverse effects of work-from-home given this COVID-19 pandemic situation is discussed in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data sharing does not apply to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zahid Hussain Bhat

Zahid Hussain Bhat ([email protected]) is an Assistant Professor in the Higher Education Department with expertise in Human Resource Management and Organizational Behaviour. Presently stationed at AAA Memorial Degree College, Cluster University Srinagar, he is instrumental in shaping the minds of postgraduate students through his captivating teaching of these subjects. With a profound passion for Industrial/Organizational Psychology and Human Resource Management, Dr. Bhat’s research prowess lies in Training Evaluation and Strategic Public Policy. His diligent contributions have led to the publication of numerous influential papers in distinguished journals, including the Global Business Review, Industrial and Commercial Training, and Human Resource Development International. In addition to his journal publications, Dr. Bhat has made significant contributions to the academic community through the authorship of book chapters in renowned publishing houses. Furthermore, he has actively participated in collaborative working papers, fostering a culture of knowledge exchange and cooperation.

Uqba Yousuf

Uqba Yousuf ([email protected]) is an Assistant Professor at the Higher Education Department, Govt. of J&K. Presently posted in Cluster University Srinagar. She teaches courses like Human Resource Development and Industrial Relations to postgraduate students. Her research area is Human Resource Management. The author has got one publication to her credit.

Nuzhat Saba

Nuzhat Saba ([email protected]) completed her Masters in Sociology from the University of Kashmir. She also served as Protection Officer Institutional Care in JK Integrated Child Protection Scheme.

References

- Aguilera, A., Lethiais, V., Rallet, A., & Proulhac, L. (2016). Home-based telework in France: Characteristics, barriers, and perspectives. Transportation Research Part A: Policy & Practice, 92(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2016.06.021

- Ahmed, I., Riaz, T., Shaukat, M. Z., & Butt, H. A. (2013). Social exchange relations at work: A knowledge sharing and learning perspective. World Journal of Management and Behavioral Studies, 1(1), 33–35.

- Allen, T. D., Cho, E., & Meier, L. L. (2014). Work–family boundary dynamics. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology & Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 99–121. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091330

- Allen, T. D., Golden, T. D., & Shockley, K. M. (2012). How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 16(2), 40–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100615593273

- Al Mehrzi, N., Kumar, S., Singh, K., Burgess, T. F., & John Heap, S. (2016). Competing through employee engagement: A proposed framework. International Journal of Productivity & Performance Management, 65(6), 831–843. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-02-2016-0037

- Almonacid-Nieto, J. M., Calderón-Espinal, M. A., & Vicente-Ramos, W. (2020). Teleworking effect on job burnout of higher education administrative personnel in the Junín region, Peru. International Journal of Data & Network Science, 4(4), 373–380. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.ijdns.2020.9.001

- Althobaiti, S., Alharthi, S., & AlZahrani, A. M. (2020). Medical systems’ quality evaluated by perceptions of nursing care: Facing COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal for Quality Research, 14(3), 895–912. https://doi.org/10.24874/IJQR14.03-16

- Anderson, J., Bricout, J. C., & West, M. D. (2001). Telecommuting: Meeting the needs of businesses and employees with disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 16(2), 97–104.

- Ashforth, B. E., Kreiner, G. E., & Fugate, M. (2000). All in a day’s work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. Academy of Management Review, 25(3), 472. https://doi.org/10.2307/259305

- Atkinson, C., & Sandiford, P. (2016). An exploration of older workers’ flexible working arrangements in smaller firms. Human Resource Management Journal, 26(1), 12–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12074

- Attridge, M. (2009). Measuring and managing employee work engagement: A research and business literature review. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 24(4), 383–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/15555240903188398

- Ayar, D., Karaman, M. A., & Karaman, R. (2022). Work-life balance and mental health needs of health professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(1), 639–655. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00717-6

- Bakker, A. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2010). Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research. Psychology Press.

- Bathini, D. R., & Kandathil, G. M. (2020). Bother me only if the client complains: Control and resistance in home-based telework in India. Employee Relations, 42(1), 90–106. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-09-2018-0241

- Beauregard, T. A., & Henry, L. C. (2009). Making the link between work-life balance practices and organizational performance. Human Resource Management Review, 19(1), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2008.09.001

- Belzunegui-Eraso, A., & Erro-Garces, A. (2020). Teleworking in the context of the COVID-19 crisis. Sustainability, 12(9), 36–62. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093662

- Bierema, L. L. (2020). HRD research and practice after ‘the great COVID-19 pause’: The time is now for bold, critical, research. Human Resource Development International, 23(4), 347–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2020.1779912

- Bin, W., Liu, Y., Qian, J., & Parker, S. K. (2021). Achieving effective remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A work design perspective. Applied Psychology, 70(1), 16–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12290

- Bird, J. (2006). Work-life balance: Doing it right and avoiding the pitfalls. Employment Relations Today, 33(3), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/ert.20114

- Bloom, N., Liang, J., Roberts, J., & Ying, Z. J. (2015). Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(1), 165–218.

- Bolino, M. C., Kelemen, T. K., & Matthews, S. H. (2021). Working 9-to-5? A review of research on nonstandard work schedules. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 42(2), 188–211. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2440

- Breaugh, J. A., & Farabee, A. M. (2012). Telecommuting and flexible work hours: Alternative work arrangements that can improve the quality of work life. (Reilly, N., Sirgy, M. & Gorman, C., Eds). Work and Quality of Life, Springer.

- Brown, T., Park, A., & Pitt, L. (2020). A 60-year bibliographic review of the journal of advertising research: Perspectives on trends in authorship, influences, and research impact. Journal of Advertising Research, 60(4), 353–360. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-2020-028

- Bruck, C. S., Allen, T. D., & Spector, P. E. (2002). The relation between work–family conflict and job satisfaction: A finer-grained analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60(3), 336–353.

- Bulińska-Stangrecka, H., Bagieńska, A., & Iddagoda, A. (2021). Work-life balance during COVID-19 pandemic and remote work: A systematic literature review. In B. Akkaya, K. Jermsittiparsert, M. A. Malik, & Y. Kocyigit (Eds.), Emerging trends in and strategies for industry 4.0 during and beyond COVID-19. science, 2021 (pp. 19–59). https://doi.org/10.2478/9788366675391-009

- Burke, R. J., & El‐Kot, G. (2010). Correlates of work‐family conflicts among managers in Egypt. International Journal of Islamic & Middle Eastern Finance & Management, 3(2), 113–131. https://doi.org/10.1108/17538391011054363

- Burk, B. N., Pechenik Mausolf, A., & Oakleaf, L. (2021). Pandemic motherhood and the academy: A critical examination of the leisure-work dichotomy. Leisure Sciences, 43(1–2), 225–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1774006

- Carillo, K., Cachat-Rosset, G., Marsan, J., Saba, T., & Klarsfeld, A. (2021). Adjusting to epidemic-induced telework: Empirical insights from teleworkers in France. European Journal of Information Systems, 30(1), 69–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2020.1829512

- Collins, A. M., Hislop, D., & Cartwright, S. (2016). Social support in the workplace between teleworkers, office-based colleagues and supervisors. New Technology, Work and Employment, 31(2), 161–175.

- Crosbie, T., & Moore, J. (2004). Work–life balance and working from home. Social Policy & Society, 3(3), 223–233.

- D’Andrea, S. Implementing the work-life balance directive in times of COVID-19: New prospects for post-pandemic workplaces in the European Union?. (2022). ERA Forum, 23(1), 7–18. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12027-022-00703-y

- De Vries, H., Tummers, L., & Bekkers, V. (2019). The benefits of teleworking in the public sector: Reality or rhetoric? Review of Public Personnel Administration, 39(4), 570–593. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X18760124

- Dilmaghani, M. (2020). There is a time and a place for work: Comparative evaluation of flexible work arrangements in Canada. International Journal of Manpower, 42(1), 167–192. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-12-2019-0555

- Dolot, A. (2020). The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on remote work – an employee perspective. E-Mentor, 1(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.15219/em83.1456

- Donthu, N., Kumar, S., & Pattnaik, D. (2020). Forty-five years of Journal of Business Research: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.10.039

- Eddleston, K. A., & Mulki, J. (2017). Toward understanding remote workers’ management of work-family boundaries: The complexity of workplace embeddedness. Group & Organization Management, 42(3), 346–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601115619548

- El-Kot, G., Leat, M., & Fahmy, S. (2021). The nexus between work-life balance and gender role in Egypt. Work-life interface: Non-Western perspectives, 185–213. https://www.palgrave.com/gb/book/9783030666477#

- Enli-Tuncay, F., Koyuncu, E., & Ozel, S. (2020). A review of protective and risk factors affecting psychosocial health of healthcare workers in pandemics. Ankara Medical Journal, 20(2), 488–504. https://doi.org/10.5505/amj.2020.02418

- Felstead, A., Jewson, N., Phizacklea, A., & Walters, S. (2002). Opportunities to work at home in the context of work-life balance. Human Resource Management Journal, 12(1), 54–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2002.tb00057.x

- Fisher, G. G., Bulger, C. A., & Smith, C. S. (2009). Beyond work and family: A measure of work/nonwork interference and enhancement. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14(4), 441–456. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016737

- Frone, M. R. (2003). Work-family balance. In J. C. Quick & L. E. Tetrick (Eds.), Handbook of occupational health psychology (pp. 143–162). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10474-007

- Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. L. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: Testing a model of the work-family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.77.1.65

- Fujimoto, Y., Ferdous, A. S., Sekiguchi, T., & Sugianto, L.-F. (2016). The effect of mobile technology usage on work engagement and emotional exhaustion in Japan. Journal of Business Research, 69(9), 3315–3323.

- Geldart, S. (2022). Remote work in a changing world: A nod to personal space, self-regulation and other health and wellness strategies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8), 4873. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084873

- Gifford, J. (2022). Remote working: Unprecedented increase and a developing research agenda. Human Resource Development International, 25(2), 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2022.2049108

- Greenhaus, J. H., Collins, K. M., & Shaw, J. D. (2003). The relation between work-family balance and quality of life. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 63(3), 510–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00042-8

- Guest, D. E. (2002). Perspectives on the Study of Work-life Balance. Social Science Information, 41(2), 255–279.

- Hashim, R., Bakar, A., Noh, I., & Mahyudin, H. A. (2020). Employees’ job satisfaction and performance through working from home during the pandemic lockdown. Environment-Behaviour Proceedings Journal, 5(15), 461–467. https://doi.org/10.21834/ebpj.v5i15.2515

- Heiden, M., Richardsson, L., Wiitavaara, B., & Boman, E. (2018). Telecommuting in academia – associations with staff’s health and well-being. Advances in Intelligent Systems & Computing, 826(1), 308–312.

- Hutagalung, I., Soelton, M., & Octaviani, A. (2020). The role of work-life balance for organizational commitment. Management Science Letters, 10(15), 3693–3700. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2020.6.024

- Hyman, J., & Baldry, C. (2011). The pressures of commitment: taking software home. In S. Kaiser, M. J. Ringlstetter, D. R. Eikhof, & M. P. E. Cunha (Eds.), Creating Balance? International Perspectives on the Work-Life Integration of Professionals (pp. 253–268). Berlin: Springer.

- ILO. (2020). Teleworking during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond a practical guide. International Labour Organisation.

- Jin, M. H., & McDonald, B. (2017). Understanding employee engagement in the public sector: The role of immediate supervisor, perceived organizational support, and learning opportunities. The American Review of Public Administration, 47(8), 881–897.

- Johnson, L. C., Andrey, J., & Shaw, S. M. (2007). Mr. Dithers comes to dinner: Telework and the merging of women's work and home domains in Canada. Gender, Place & Culture, 14(2), 141–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/09663690701213701

- Karatepe, O. M., & Demir, E. (2014). Linking core self-evaluations and work engagement to workfamily facilitation: A study in the hotel industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 26(2), 307–323.

- Kelliher, C., & Anderson, D. (2010). Doing more with less? Flexible working practices and the intensification of work. Human Relations, 63(1), 83–106.

- Kim, S.-N., Choo, S., & Mokhtarian, P. L. (2015). Home-based telecommuting and intra-household interactions in work and non-work travel: A seemingly unrelated censored regression approach. Transportation Research Part A: Policy & Practice, 80(1), 197–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2015.07.018

- Kim, S., Park, Y., & Headrick, L. (2018). Daily micro-breaks and job performance: General work engagement as a cross-level moderator. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(7), 772–786. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000308

- Korkmaz, O., & Erdogan, E. (2014). The effect of work-life balance on employee satisfaction and organizational commitment. Ege Academic Review, 14(4), 541–557.

- Kossek, E. E., Valcour, M., & Lirio, P. (2013). Organizational strategies for promoting work–life balance and wellbeing. Work and wellbeing, 3, 295–319.

- Langa, G. Z., & Conradie, D. P. (2003). Perceptions and attitudes with regard to teleworking among public sector officials in Pretoria: Applying the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). Communicatio, 29(1/2), 280–296.

- Leat, M., & El-Kot, G. (2022). The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on teleworking and the logistics of work in Egypt. International Business Logistics, 2(1), 24–40. https://doi.org/10.21622/ibl.2022.02.1.024

- Liao, E. Y., Lau, V. P., Hui, R. T., & Kong, K. H. (2019). A resource-based perspective on work–family conflict: Meta-analytical findings. Career Development International, 24(1), 37–73. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-12-2017-0236

- Lockwood, N. R. (2003). Work/Life balance. Challenges and Solutions, SHRM Research, USA, 2(10).

- Lonska, J., Mietule, I., Litavniece, L., Arbidane, I., Vanadzins, I., Matisane, L., & Paegle, L. (2021). Work–life balance of the employed population during the emergency situation of COVID-19 in Latvia. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.682459

- Lourel, M., Ford, M. T., Edey Gamassou, C., Guéguen, N., & Hartmann, A. (2009). Negative and positive spillover between work and home: Relationship to perceived stress and job satisfaction. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 24(5), 438–449. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940910959762

- Lu, L., Lu, A. C. C., Gursoy, D., & Neale, N. R. (2016). Work engagement, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions: A comparison between supervisors and line-level employees. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(4), 737–761. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-07-2014-0360

- Lu, C., Wang, H., Lu, J. D. D., & Bakker, A. B. (2014). Does work engagement increase person–job fit? The role of job crafting and job insecurity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 84(2), 142–152.

- Martinez Lucio, M., & McBride, J. (2020). Recognising the Value and Significance of Cleaning Work in a Context of Crisis. Policy@Manchester Blogs. http://blog.policy.manchester.ac.uk/posts/2020/06/recognising‐the‐value‐and‐significance‐of‐cleaning‐work‐in‐a‐context‐of‐crisis/

- Maruyama, T., & Tietze, S. (2012). From anxiety to assurance: Concerns and outcomes of telework. Personnel Review, 41(4), 450–469. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483481211229375

- Mas-Machuca, M., Berbegal-Mirabent, J., & Alegre, I. (2016). Work-life balance and its relationship with organizational pride and job satisfaction. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 31(2), 586–602. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-09-2014-0272

- Mathew, R. V., & Natarajan, P. (2014). Work-life balance: A short review of the theoretical and contemporary concepts. https://doi.org/10.5707/cjsocsci.2014.7.1.1.24

- McDowall, A., & Kinman, G. (2017). The new nowhere land? A research and practice agenda for the “always-on” culture. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness, 4(3), 256–266. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-05-2017-0045

- McMillan, H. S., Morris, M. L., & Atchley, E. K. (2011). Constructs of the work/life interface: A synthesis of the literature and introduction of the concept of work/life harmony. Human Resource Development Review, 10, 6–25.

- Morgan, R. E. (2004). Teleworking: An assessment of the benefits and challenges. European Business Review, 16(4), 344–357.

- Morris, M. L., & Madsen, S. R. (2007). Advancing work—life integration in individuals, organizations, and communities. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 9(4), 439–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422307305486

- Muller, T., & Niessen, C. (2019). Self-leadership in the context of part-time teleworking. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(8), 883–898. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2371

- Nilsson, M., Blomqvist, K., & Andersson, I. (2017). Salutogenic resources in relation to teachers’ work-life balance. Work, 56(4), 591–602. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-172528

- Nippert-Eng, C. (1996a). Home and work: Negotiating boundaries through everyday life. University of Chicago Press.

- Oyewobi, L. O., Oke, A. E., Adeneye, T. D., Jimoh, R. A., & Windapo, A. O. (2022). Impact of work–life policies on organizational commitment of construction professionals: Role of work–life balance. International Journal of Construction Management, 22(10), 1795–1805.

- Palmatier, R. W., Houston, M. B., & Hulland, J. (2018). Review articles: Purpose, process, and structure. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46, 1–5.

- Palumbo, R. (2020). Let me go to the office! An investigation into the side effects of working from home on work-life balance. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 33(6/7), 771–790. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-06-2020-0150

- Parker, S. R. (1971). Future of work and leisure (p. 160). Praeger.

- Parkes, L. P., & Langford, P. H. (2008). Work-life balance or work-life alignment? A test of the importance of work-life balance for employee engagement and intention to stay in organizations. Journal of Management & Organization, 14(3), 267–284. https://doi.org/10.5172/jmo.837.14.3.267

- Pattnaik, L., & Jena, L. K. (2020). Mindfulness, remote engagement and employee morale: Conceptual analysis to address the “new normal”. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 29(4), 873–890.

- Peters, S. E., Dennerlein, J. T., Wagner, G. R., & Sorensen, G. (2022). Work and worker health in the post-pandemic world: A public health perspective. The Lancet Public Health, 7(2), e188–e194. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00259-0

- Pocock, B., Skinner, N., & Ichii, R. (2009). Work, life and workplace flexibility: The Australian work and life index 2009. Centre for Work +Life, University of South Australia.

- Popovici, V., & Popovici, A. L. (2020). Remote work revolution: Current opportunities and challenges for organizations. Ovidius University Annals, Economic Sciences Series, 20, 468–472.

- Powell, G., & Greenhaus, J. (2006). Is the opposite of positive negative? Untangling the complex relationship between work-family enrichment and conflict. Career Development International, 11(7), 650–659. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430610713508

- Rahim, N. B., Osman, I., & Arumugam, P. V. (2020). Linking work-life balance and employee well-being: Do supervisor support and family support moderate the relationship? International Journal of Business and Society, 21(2), 588–606. https://doi.org/10.33736/ijbs.3273.2020

- Ramos-Rodrígue, A. R., & Ruíz-Navarro, J. (2004). Changes in the intellectual structure of strategic management research: A bibliometric study of the Strategic Management Journal, 1980–2000. Strategic Management Journal, 25(10), 981–1004.

- Sheehan, C., Tham, T. L., Holland, P., & Cooper, B. (2019). Psychological contract fulfilment, engagement and nurse professional turnover intention. International Journal of Manpower, 40(1), 2–16.

- Shirmohammadi, M., Au, W. C., & Beigi, M. (2022). Remote work and work-life balance: Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic and suggestions for HRD practitioners. Human Resource Development International, 25(2), 163–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2022.2047380

- Sirgy, M. J., & Lee, D.-J. (2018). Work-life balance: An integrative review. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 13(1), 229–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-017-9509-8

- Skinner, N., Elton, J., Auer, J., & Pocock, B. (2014). Understanding and managing work-life interaction across the life course: A qualitative study. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 52(1), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12013

- Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104(July), 333–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

- Sullivan, C. (2012). Remote working and work-life balance. In N. Reilly, M. Sirgy, & C. Gorman (Eds.), Work and quality of life: International handbooks of quality-of-life (pp. 275–290). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4059-4_15

- Thulin, E., Vilhelmson, B., & Johansson, M. (2020). New telework, time pressure, and time use control in everyday life. Sustainability, 11(11), 3067. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113067

- Timms, C., Brough, P., O’Driscoll, M., Kalliath, T., Siu, O. L., Sit, C., & Lo, D. (2015). Flexible work arrangements, work engagement, turnover intentions, and psychological health. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 53(1), 83–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12030

- Tremblay, D. (2002). Balancing work and family with telework? Organizational issues and challenges for women and managers. Women in Management Review, 17(3/4), 157–170.

- Troup, C., & Rose, J. (2012). Working from home: Do formal or informal telework arrangements provide better work-family outcomes? Community, Work & Family, 15(4), 471–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2012.724220

- Uqba, Y., & Bhat, Z. H. (2020). The ramifications of telecommuting on work-life balance in COVID-19 pandemic. In T. Wani & A. Anwar (Eds.), Contemporary business trends: Pre and post-COVID scenario (pp. 201–213). Bloomsbury Publishing, India.