Abstract

In today’s ever-evolving business landscape, understanding the shifting buying behaviors of consumers has become a formidable challenge for businesses worldwide. To navigate these changes successfully, businesses are increasingly turning to Social Networking Sites (SNS) to attract, connect with, and engage customers profitably. However, analyzing the influence of social networking sites on Impulse Buying Behavior (IBB) among customers is challenging for businesses and significant for their sustainability in the market. The main purpose of the present research work is to analyze the influence of social media on Impulse Buying Behavior (IBB) among customers in Saudi Arabia. The present quantitative study was conducted by sending a survey questionnaire to 342 Saudi Arabian consumers who are also users of social media. Data analysis was done using the PLS-SEM technique using smart PLS 4.0 software. The findings of the study suggested that Social Media Advertising (SMA) significantly influenced Impulse Buying Intention (IBI), but no effect was reported by the Social Media Community (SMC) on Impulse Buying Intention (IBI). However, the overall model explained 50 percent Impulse Buying Intention (IBI) and 33 percent Impulse Buying Behavior (IBB). The study will enable marketers, scholars, and researchers to understand the concept of Impulse buying by offering managerial implications and future research directions.

1. Introduction

Social Networking Sites (SNS) play a significant role in influencing consumers’ purchasing decisions (Wegmann et al., Citation2023; Xiang et al., Citation2022). This influence often leads to spontaneous purchases while casually scrolling through these platforms, which can be termed as impulse buying (Han, Citation2023). The prevalence of social media has contributed to a rise in impulse buying behavior (Johan et al., Citation2023). This phenomenon, known as “Impulse buying,” refers to the sudden and unplanned decision to make a purchase (Amos et al., Citation2014; Stern, Citation1962). The modern culture places a high emphasis on shopping, but it’s crucial to be aware that excessive and uncontrolled buying can lead to undesirable consequences. Social networking sites play a key role in amplifying the tendency toward impulsive buying among their users (Pahlevan Sharif et al., Citation2022; She et al., Citation2021). Since the early 2000s, the use of social networking sites has skyrocketed, and businesses have capitalized on this trend by implementing social commerce strategies, resulting in increased revenue (Xiang et al., Citation2022).

In today’s technological scenario, social media has emerged as the main choice for the recommendation of all brands ’products (Akram et al., Citation2018). Based on previous research, users are clearly familiar with SNS such as YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram (Siriaraya et al., Citation2019). As millions of users are actively using social networking sites, it is a great source of promotion of products and services as per the interests of users. SNS also provide the opportunity to connect users with each other (Aragoncillo & Orus, Citation2018; Shiva & Singh, Citation2019). Through SNS, businesses influence the buying decision of users. Evident from existing studies that consumer buying behavior is highly influenced by Impulse behavior, and Impulse involves factors like consumer psyche, social, economic, and consumer attitude. In other words, we can say that impulse buying is not just unplanned purchasing (Stern, Citation1962). Unintended purchasing happens when a customer has a feeling of influential and insistent but unpredictable wish to buy something promptly due to some emotional connotation (Chen & Wang, Citation2016; Rook, Citation1987). Unintended purchasing can be prompted by inadequate deliberation of the consequences of spending (Zafar et al., Citation2021). Consumers behave impulsively towards a diverse range of products such as automobiles, candy, and fashion (Bansal & Kumar, Citation2018; Sharma et al., Citation2018). Consumer buying behavior is sometimes not a response towards a reasoned action; however, it may be prompted by an added straight and instant stimulus. In precise, impulsive buying involves an unexpected need to buy something without intent or idea (Lee & Yi, Citation2008b). Likewise, Li (Citation2015) defines impulsive behavior as buying instinctively due to physical closeness and emotional attachment to the wanted product resulting in individual fulfillment (Hashmi et al., Citation2019; Li, Citation2015). More than ninety percent of individuals who make unplanned purchases accept that they did not plan to buy initially, and forty percent of overall consumer spending goes to impulse buying (Gaille, Citation2017). The driving forces influencing impulse purchases are sales promotion offers, accounting for 88% of the total impulse purchase (Gaille, Citation2017; Hashmi et al., Citation2019; Li, Citation2015). Similarly, sixty percent of female consumers have recently made an impulse purchase. Demographically, a higher-income young consumer has a higher percentage of impulse purchases (Gaille, Citation2017).

The business environment has transformed due to technical know-how; it has familiarised many newest revolutions, such as social networking sites. Though individuals use these platforms primarily for interacting with others, they also exchange their thoughts, ideas, and involvements about various products and services on social media (Khokhar et al., Citation2019). Moreover, Buying and acquiring knowledge about products or services on virtual platforms have become a universal exercise (Sharma et al., Citation2018). Now, the promotion of products is not just limited to traditional media such as print and electronic media. Businesses are using Social media to promote their products and services (Rehman et al., Citation2014). Because companies can quickly reach customers through emails, content, web-based activities, and display promotions throughout the world, these technologies have proven quite advantageous for online shops (Rehman et al., Citation2014). Facebook and Instagram are the two most popular social networking sites which engage millions of people. Eventually, the favourite for big brands for promotion (Sharma et al., Citation2018). Instagram has 70 percent more engagement than Facebook, especially among the young generation. Showing videos and pictures of the brands with influencers on Instagram drives impulse purchases (Lo et al., Citation2016).

Consumer research has increasingly focused on impulsive buying within the context of social networking sites (Nasir et al., Citation2021; Rahman & Hossain, Citation2023; Rahman et al., Citation2023). Consequently, social commerce has become inherently associated with impulse buying, as consumers often make unplanned product decisions while engaged with social media (Han, Citation2023; Madhu et al., Citation2023). Notably, previous studies have shown that social networking sites encourage consumers to bypass traditional decision-making evaluation steps, frequently leading to impulsive buying behaviors (Djafarova & Bowes, Citation2021; Han, Citation2023; Pellegrino et al., Citation2022; Wu et al., Citation2020; Yi et al., Citation2023). Although impulse buying has been widely discussed in academia from different perspectives, there is a lack of investigation available on the impact Social Media Community (SMC) driving Impulse Buying Behavior (IBB). Zhao et al. (Citation2019) argued that SMC events such as online shopping carnival contributes to driving impulse purchases, resulting in the introduced call to action feature that induced impulse buying on Instagram (Li, Citation2015; Sharma, Citation2019; Sharma et al., Citation2018). It was also argued that celebrity interaction with their followers and their posts drives the audience to purchase the endorsed products impulsively (Handayani et al., Citation2018; Zafar et al., Citation2021; Zhao et al., Citation2019). However, limited research is available with special attention to how the SMC drive impulses purchase. Additionally, dearth of information available on social media driving impulse buying in Saudi Arabia is rare. Therefore, the study tries to fill the gap by addressing various aspects of SMC and Social Media Advertisement (SMA) and further, their impact on Impulse Buying Intention (IBI) in the context of Saudi Arabia consumers to measure the impact of social media on Impulse Buying Behavior (IBB).

The present study is an attempt to measure the impact of social platforms on impulse buying behavior among Saudi Arabian consumers. Therefore, the present research is an effort to fulfil the identified gap in the existing literature and assist businesses in understanding the impulse buying behavior of Saudi consumers. The study has been categorised into six sections. The first section outlines the significance of conducting this study. The second section includes a literature review and starts with the theoretical underpinnings related to the research theme, followed by a literature review on Social Media Community, Social Media Advertisements, and Impulse Buying Behavior. The review of the literature further helps to find the research gap that eventually led to hypothesis development and conceptual modelling. The next section explains in detail the methods and materials adopted in this study to select the sample size, the survey scale adoption to develop the survey questionnaire, and the hypothesis testing procedures. Subsequently, the fourth section explains the results and data analysis. Section fifth includes key discussions of the study followed by sub-sections, namely managerial implications, limitations of present research work, and directions for future research. Lastly, the conclusion summarises this study with concluding remarks on how this study is different from existing studies, followed by references at the end.

2. Literature review

2.1. Theoretical underpinnings

During the 1940s, the concept of “Impulse Buying” first evolved as unsubstantiated actions (Aragoncillo & Orus, Citation2018). Few existing studies defined Impulse buying as an unexpected act that contrasts with intentional buying that is developed lacking thoughtful attention to its continuing concerns. It can be further understood as unreasonable behaviors (Ahn et al., Citation2020; Li & Jing, Citation2012; Moon et al., Citation2017; Pradhan, Citation2016; Zhang et al., Citation2018). In further studies, writers such as Stern (Citation1962), Applebaum (Citation1951), and Kollat and Willett (Citation1969), have drawn out the thought by establishing that unplanned buying developed after the contact to inducement. Applebaum (Citation1951) explained it as an unplanned purchase by customers while shopping in a store and stimulated them to purchase after looking at promotional campaigns in the store. Buying may frequently not function as a logical act but be prompted by a more direct and instant stimulus. Impulsive buying causes an unexpected desire to purchase something lacking a prior plan or disposition. Impulsive behavior has been defined as buying instinctively due to familiarity and sensitive attachment to the anticipated products causing personal fulfilment (Hashmi et al., Citation2019; Lee & Yi, Citation2008b; Li, Citation2015). This concept stimulated various researchers to conduct research studies on it, and subsequently, many faced issues in assessing it (Kollat & Willett, Citation1969). However, numerous authors discussed that outlining impulse buying based on unintended buying is slightly unsophisticated (Kollat & Willett, Citation1969; Rook, Citation1987; Stern, Citation1962) and departed a stage ahead more by disagreeing that all impulsive buying can be deliberated as unintended, not all unintended buying can be deliberated as impulsive buying (Koski, Citation2004). Unintentional buying might happen as consumers are looking to purchase various products not added in the ongoing sales promotions launched by sellers, and during their store visits to stores, the moment they find a better deal, they buy it instantly. However, unintentional buying is not predictably supplemented by a burning desire or a robust encouraging state of mind that is usually connected to a purchasing instinct (Amos et al., Citation2014). Moreover, vis-à-vis the theoretical underpinning of the preceding works of literature, numerous studies implemented Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) as their basic context to examine online unplanned buying behavior. Though online impulse buying fascinated the consideration of researchers and scholars in the field of social commerce, the theoretical foundation of online impulse buying behavior study is presently in its embryonic stage and dispersed. Evolving new concepts in this field of study is deliberated as one of the perplexing concerns for future research related to Information Systems (Busalim & Hussin, Citation2016).

Social media has the potential to impact on Impulse buying nature of consumers. It can play a noteworthy part in stirring impulse buying behavior among consumers. Furthermore, it also influences the shopping behavior of consumers (Xiang et al., Citation2016). Users over social networking sites post a comprehensive range of involvements, oscillating from what they are in the temperament on that day, to enthusiastically assessing goods and services i.e., products they want to use (Anderson et al., Citation2011). This further leads to impact others social media users through writing comments by sharing depictions of their existing procurements and offering helpful commendations to potential buyers. These activities displayed by social media users can fuel unintentional and impulse buying (Xiang et al., Citation2016). Hence, theoretically, and empirically, further research exertions are desirable to examine the reasons for online impulse buying behavior to enhance scholars and researchers’ understandings of impulse buying behavior and the impact of social media on it. Most of the prevailing studies cast off website-related factors as precursors of impulse buying behavior study, and little consideration was given to social media and marketing related factors. Impulse buying has been researched for decades in the field of marketing research; consequently, it is significant to investigate the impact of social media on Impulse buying (Busalim & Hussin, Citation2016).

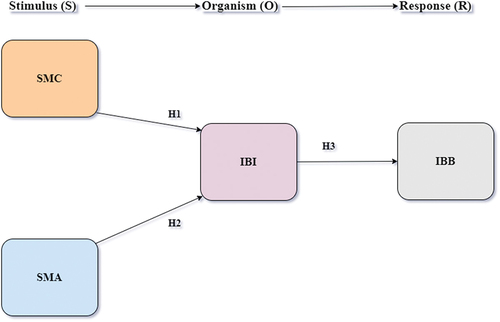

The S-O-R framework was first proposed in 1929 which stands for Stimuli (S), Organisms (O) and Response (R) by Woodworth in his scholarly work (Woodworth, Citation1929). In this model, “Stimulus” defines the environmental factor arousing the organismic and internal states (Song et al., Citation2021). “Organism” indicates to humans’ affective and mental intermediate states that mediate the impact of the stimulus on individual customer’ responses (Wu & Li, Citation2018). “Response” states that consumers’ final purchase decisions and buying behaviors are based on sentimental and mental states (Sherman et al., Citation1997). As stated by Mehrabian and Russell (Citation1974), the retail shopping atmosphere encompasses stimuli (S) that impact organisms (O) & result in methodology or prevention response (R) behaviors concerning the store and in behaviors like store searching, intention to purchase, & repurchase intention. Stimuli is created by retailers using advertisements and marketing communications to ignite the customers’ behavior, and further leads to generate responses by cultivating impulse buying behavior among customers. This S-O-R framework explores the environmental cues (e.g., music, crowding, color, lighting, layout & fragrance) and their associated impacts on customers’ internal states & external responses in retail store ecosystems (e.g., Koo & Ju, Citation2010; Mehrabian & Russell, Citation1974; Richard, Citation2005; Wang et al., Citation2010). The S-O-R is chronological in nature (Kühn & Petzer, Citation2018), in accordance with the stimulus which is the initial stage of customers’ state of organism & ultimate response behavior in a consumption or shopping backdrop. Social media marketing—and impulse buying—concerned aspects are external stimuli that can activate the S-O-R process (Zhang et al., Citation2018). The current study has proposed and developed a conceptual framework based on the S-O-R model (see Figure ).

2.2. Hypothesis development and conceptual modelling

This section explores the underlined factors that influence the impulse buying behavior of consumers in Saudi Arabia. Unfortunately, previous studies did not explain the impulse buying behavior of Saudi Arabia consumers. Hence, present research work attempts to shed light on the relationship between Social Media Community, Social Media Advertisement, Impulse Buying Intention, and Impulse Buying Behavior in Saudi Arabian context.

2.2.1. Social Media Community (SMC) and Impulse Buying Intention (IBI)

The influence of social media on consumers’ purchasing behaviors is significant, particularly when it comes to the emergence of impulsive buying tendencies (Barger et al., Citation2016; Rydell & Kucera, Citation2021). This impact is rooted in the way social media platforms have reshaped consumers’ buying preferences, with the central catalyst being the Social Media Community (SMC) (Rydell & Kucera, Citation2021). Social media platforms have revolutionized the consumer landscape by enabling users to effortlessly create and share content, access valuable information, and tap into the lasting influence of SMCs within their online networks. This phenomenon has played a substantial role in nurturing impulsive buying behaviors among users of social media (Rydell & Kucera, Citation2021).

Online SMCs have evolved into dynamic societal frameworks where participants freely exchange associations and connections, providing a platform for individuals who share similar ideas, values, attitudes, thoughts, and feelings (Nambisan & Watt, Citation2011). As a result, SMCs have fundamentally transformed the traditional approach to seeking product information and recommendations (Olbrich & Holsing, Citation2011; Pagani & Mirabello, Citation2011). With the growing popularity of SMCs, their capacity to disseminate information, share product knowledge, and influence impulsive buying behaviors has become increasingly apparent (Chen et al., Citation2011). This evolution aligns with the rapid expansion of internet users, prompting businesses to adopt information systems that engage and acquire customers through online communities (Lu & Hsiao, Citation2010). The role of online communities within social media platforms has become exceptionally dynamic, offering consumers a space to exchange product reviews and recommendations, thereby shaping their purchasing decisions (Miller et al., Citation2009). As a result, online customers have come to place higher trust in reviews and opinions found on social media platforms compared to information provided by companies, perceiving these reviews as more reliable (Segran, Citation2017).

The relationship between Social Media Community (SMC) and Impulse Buying Intention (IBI) is a dynamic interplay that significantly influences purchase decisions within the realm of social media. SMCs serve as vibrant digital ecosystems where individuals connect, share, and interact, ultimately fostering a sense of community. Within these communities, the sharing of opinions, product reviews, and recommendations exerts a profound impact on consumers’ IBI (Heinemann, Citation2023; Reynolds et al., Citation2023). As social media users engage with content created by their peers and like-minded individuals within these communities, the allure of spontaneous and unplanned purchases intensifies. Consequently, the manifestation of IBI within SMCs can have substantial consequences on the purchase decisions of social media users. These digital communities not only shape consumer preferences but also play a pivotal role in steering purchase choices, ultimately influencing the products and brands that individuals opt for within the social media marketplace (Daniel et al., Citation2018; Dessart et al., Citation2015).

Considering this extensive review of literature, we have formulated the following hypothesis to better understand the relationship between these variables:

H1:

Social Media Community positively influences Impulse Buying Intention among Saudi Arabian consumers.

2.2.2. Social Media Advertising (SMA) and Impulse Buying Intention (IBI)

The rapid expansion of social media usage and the widespread access to internet-enabled devices have empowered billions of individuals to freely share their past purchasing experiences on social media platforms. This surge in user-generated content has disrupted the landscape of impulse buying (Islam et al., Citation2021; Parsons et al., Citation2014; Prentice et al., Citation2020). Social Media Advertising (SMA) has evolved from simply being a presence on social networking platforms to an indispensable component of contemporary business strategies. In today’s business environment, nearly all companies are striving to establish a digital footprint across various social media platforms. These platforms not only serve as effective tools for promoting products and services but also play a pivotal role in cultivating impulsive buying tendencies among users. Additionally, factors such as age, gender, and socio-economic conditions of consumers have been found to influence the relationship between SMA and IBI (Chawla, Citation2020; Rodgers et al., Citation2014; Varghese & Chitra, Citation2022; Yang et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, SMA, coupled with social media users’ comments and feedback, has a transformative effect on consumer purchasing behavior (Chawla, Citation2020; Yang et al., Citation2021). Marketers often employ engaging content formats, such as memes, images, audio, short videos, and blogs, in SMA efforts to captivate users and influence their impulse buying behavior. SMA’s ability to target individual customers based on their demographic profiles surpasses the capabilities of traditional media (Rodgers et al., Citation2014). SMA serves as a dynamic platform for information sharing, collaboration, and relationship-building for both marketers and users. It has proven to be an innovative tool that provides real-time customer feedback on brands, products, offers, and services (Fauser et al., Citation2011).

The interplay between Social Media Advertising (SMA) and Impulse Buying Intention (IBI) unfolds as a dynamic force shaping purchase decisions within the realm of social media (Volpi & Clark, Citation2019). SMA leverages the vast reach of social media platforms to showcase products and services through captivating content formats, enticing users to make impulsive purchasing decisions (Wegmann et al., Citation2023; Xiang et al., Citation2022). This persuasive advertising strategy not only captures the attention of social media users but also influences their IBI by presenting compelling product narratives and tempting offers (Hazari et al., Citation2023; Lou & Yuan, Citation2019). Consequently, the prevalence of SMA within social media environments has profound consequences on purchase decisions, as users are enticed to act on their impulse buying tendencies (Korkmaz & Seyhan, Citation2021). In essence, SMA serves as a catalyst for IBI, amplifying its influence and driving consumers towards spontaneous purchases on social media platforms (Lavuri & Thaichon, Citation2023; Pahlevan Sharif et al., Citation2022; She et al., Citation2021).

In light of this comprehensive review of literature, we have formulated the following hypothesis to investigate the relationship between these variables:

H2:

Social Media Advertising positively influences Impulse Buying Intention among Saudi Arabian consumers.

2.2.3. Impulse Buying Intention (IBI) and Impulse Buying Behavior (IBB)

Impulse Buying Intention (IBI) and Impulse Buying Behavior (IBB) share an intricate and consequential relationship in the context of consumer behavior, particularly within the dynamic landscape of social media and digital commerce. As consumers navigate the realms of both online and traditional commerce, the term “impulse buying” has become increasingly familiar, transcending the boundaries of these shopping environments. Social media has emerged as a key player in the cultivation of impulse buying behavior among its users (Chawla, Citation2020; Varghese & Chitra, Citation2022; Yang et al., Citation2021). Within this digital space, social media users often find themselves influenced not only by their own experiences but also by the interconnected relationships they form with their peers and the broader online community. These interactions further fuel their Impulse Buying Intention (IBI), creating a continuous cycle of impulse-driven purchasing tendencies (Joseph & Enid, Citation2022). However, it’s noteworthy that recent studies, such as Joseph and Enid (Citation2022), suggest a shift in the landscape, with indications that the era of inducing impulse buying through social media may be transitioning to a new phase marked by more challenging market demands, potentially questioning the obligatory impact of social media on consumers’ IBI. Furthermore, the convenience of online shopping, facilitated by E-Commerce platforms, has encouraged consumers to make purchases impulsively (Al-Zyoud, Citation2018). Impulse buying, characterized by the act of succumbing to immediate and compelling motives, often leads to a complex emotional struggle, with consumers disregarding the consequences of their purchases (Al-Masri, Citation2020). For marketers, comprehending the factors that influence impulsive buying is essential, as it equips them with insights into attracting more consumers to purchase their goods and services (Al-Masri, Citation2020). Additionally, the rise of social media has redefined marketing communication, turning social media users into potential consumers and active participants in marketing strategies (Al-Zyoud, Citation2018). Nevertheless, a research gap remains regarding a comprehensive exploration of how social media influences impulse buying, particularly among Saudi Arabian consumers (Al-Zyoud, Citation2018).

The increasing demand for products adhering to Islamic standards has further motivated researchers to delve into the purchasing behavior of Saudi Arabian consumers, given the country’s prominent role in Islam (Karoui & Khemakhem, Citation2019). This exploration has revealed that religion, specifically Islamic values, plays a substantial role in shaping consumer behavior. In addition to cultural, social, and psychological factors, positive emotional variables such as pleasure, happiness, honor, pride, and self-satisfaction significantly impact purchasing behavior, aligning with hedonic values closely related to impulse buying (Hashmi et al., Citation2019). Moreover, several factors, including hedonic motivation, website quality, trust, and variety-seeking behavior, have been identified as influencers of impulsive buying (Al-Zyoud, Citation2018). The growth of social media in Saudi Arabia, with approximately 25 million active users, calls for a deeper exploration of this phenomenon within the Saudi Arabian context (Al-Zyoud, Citation2018). The advent of the internet and social media has revolutionized consumer-company interactions, enabling seamless networking and transactions.

Social networking sites have created a space for consumers to share a wide range of experiences, including their shopping endeavors, leading to an unexpected surge in impulse buying behavior (Xiang et al., Citation2016). Marketers have recognized the significance of social networking sites in reaching and engaging their target customers, using these platforms to promote products and services effectively (Tanuri, Citation2010). Prior research has highlighted that consumers consistently experience impulsive impulses during their shopping journeys, both online and offline, often unable to resist these urges despite their best efforts (Baumeister, Citation2002; Beatty & Ferrell, Citation1998; Dholakia, Citation2000; Rook, Citation1987). Online marketing, especially through social media, triggers stimuli that simplify impulsive buying (Madhavaram & Laverie, Citation2004). Impulse buying occurs when a consumer experiences an unexpected, intense, and persistent urge to make an immediate purchase (Rook, Citation1987). In the context of online impulse buying, studies have affirmed that the desire to buy impulsively significantly influences impulse buying (Ortiz et al., Citation2017). Therefore, stimulating consumers’ urge to buy impulsively, particularly through social media, is essential in promoting impulse buying behavior. The more stimuli consumers are exposed to, the stronger their urge to buy impulsively becomes, ultimately intensifying impulse buying behavior during online shopping over social media platforms and websites (Huang, Citation2016; Kusmaharani & Halim, Citation2020; Lin et al., Citation2022; Zafar et al., Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2018).

In summary, a clear and intricate relationship exists between Impulse Buying Intention (IBI) and the desire to buy impulsively, forming the foundation for the following hypothesis:

H3:

Impulse Buying Intention positively influences the Impulse Buying Behavior of Saudi Arabian consumers.

2.2.4. Conceptual model

Conceptual model as shown in Figure was built on the contributions received from S-O-R model. The model was proposed by Woodworth in 1929. The model is an advancement of Pavlov (Citation2010) classical theory of stimulus-Response model. The S-O-R model helps in understanding what causes individuals’ behavior and can therefore be used to address human behavior issues.

In general, the S-O-R model is used to inspect the relationship between stimulus and response, as well as how organisms affect those relations. Therefore, the present study adopted the S-O-R model to determine various stimulus and their impact on consumer behavior. We have used social media advertisement (SMA) and social media community (SMC) as marketing stimuli, that leads to Impulse buying intention (IBI) representing Organism (O), that finally lead to response (R) in terms of Impulse buying or using the products and services unplanned.

3. Methods and materials

3.1. Data collection instrument

A close-ended questionnaire was developed and floated among Saudi Arabian consumers. The questionnaire consists of two parts; the first part was focuses on the respondents’ general information, such as their age, sex, and shopping frequency, and the second focuses on the specific questions related to the variables under investigation. Questions were asked on the five-point Likert scale from strongly agree to disagree strongly, where 1= strongly disagree, and 5= strongly agree. An online survey was conducted to collect the primary data. The questionnaire items were adopted from the work of Verplanken and Herabadi (Citation2001); Sharma et al. (Citation2018), the similar studies which were published in Indian context. This ensures the validity and the reliability of the instrument.

3.2. Pilot survey and data collection

Before executing the final survey, a pilot study was conducted on 43 respondents to check the instrument reliability and content validity. Additionally, the questionnaire was also checked and verified by professors and industry professionals to ensure the content validity of the questionnaire. During the pilot survey, those items showing low Cronbach alpha values (<0.70) were removed from the further analysis. Finally, the survey was executed to a large sample for data collection. A survey link from google Forms was emailed to approximately 2549 respondents. These are mostly the students and social media connections such as followers and those who follows the authors from Saudi Arabia. Out of 2549 respondents, we received 342 responses within six months of conducting the survey. Incomplete filled responses were removed during scrutiny, which was approximately 83. So, the final sample selected for the study was 259 respondents. These responses were sufficient to conduct further analysis. The description of the sample is described in Table .

Table 1. Description of the sample selected for the study

3.3. Sample size justification

The study adopted the thumb rule proposed by Hair et al. (Citation2019) to select the sample size. The sample size should preferably be five to ten times as large as the number of variables in the study, according to the thumb rule that has been used to determine sample size in multivariate research (including multiple regression analyses). The questionnaire contained 25, thus 250 people would have to complete the survey to undertake the minimum sample size necessary for the multivariate analysis. As a result, the sample size was suitable for carrying out the statistical analysis.

The demographic details of the respondents are shown in Table . As demonstrated, a mixed bag of samples was selected for the study. The sample comprised 69.1 percent male and 30.9 percent of female respondents. Similarly, 40 percent of respondents belong to the age group of 27 to 35. Followed by 25.1 percent and 23.6 percent of 36 to 44 and 18 to 26 years of age. Only 11.2 percent of respondents were above 45 or above. All respondents had at least one social media account; most used Instagram as their preferred social media channel. Most respondents (62.2 percent) were light to medium social media users (19.3 percent used 6 to 9 hours daily). Approximately 60 percent preferred social media for online shopping and were mostly interested in purchasing books, followed by fashion accessories and mobile and other electronic devices from social media.

3.4. Data analysis and hypothesis testing

The collected data were analyzed using the PLS-SEM method with the help of Smart PLS 4.0 software. The description of the sample collected through an online survey is shown in Table . For hypothesis testing, the study adopted a cross-sectional research design to measure the constructs such as social media community, social media advertisement, impulse buying intention and impulse buying Behavior; the study adopted a previously validated scale recommended by researchers and academicians (Verplanken & Herabadi, Citation2001).

Table 2. Construct reliability and validity

4. Hypothesis testing

The study employs covariance-based structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to test the hypothesis and fitness of the model by using smart PLS 4.0 version software. Most researchers recommend PLS-SEM to analyze the data due to its various benefits over other software; in contrast to CB-SEM, PLS-SEM does not take into account normal distribution and has the highest potential for concurrently evaluating the connections of all included factors, even in small sample sizes (Hair et al., Citation2016).

4.1. Common method bias

The same respondents’ data was obtained for both dependent and independent conceptions using a single instrument, resulting in Common method bias (CMB) or common method variation. We used the latent factor test and Harman’s one-factor test were all used to evaluate the CMB. The test findings showed that all of the items were properly loaded into their respective constructs and that there was no preponderance of a single factor that accounted for most of the variation. The latent factor test results also show no difference of more than 0.2 in the factor loading of the items on their underlying latent construct (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003).

4.2. Measurement model

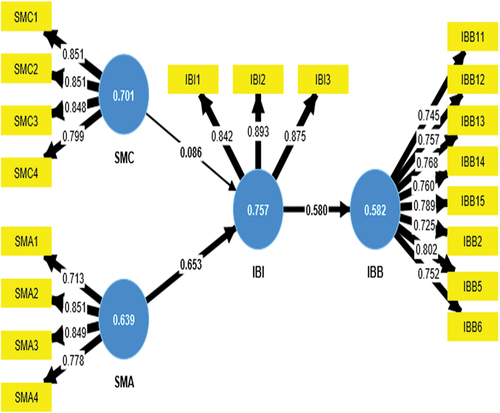

Testing the measurement model’s validity and reliability was done in this study (Hair et al., Citation2016). Table ‘s results showed that Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability, and factor loadings were all over the threshold of 0.70. Average variance extracted (AVE) values for all reflective constructs exceeded the criterion of 0.50. These findings line up with earlier research (Hair et al., Citation2016). Table presents comprehensive findings.

Table 3. Constructs with factor loadings

Additionally, the Fornell and Larcker criteria and the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) correlation ratio were used to evaluate discriminant validity (DV). All square root of AVE values in the Fornell and Larcker criteria were greater than the correlation values of the constructs (Refer Table ).

Table 4. Discriminant validity: Fornell-Larcker criterion

Every HTMT reading fell below the threshold of 0.85. (Refer Table ). These findings demonstrate that DV is not problematic for this study (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981).

Table 5. Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) – matrix

4.3. Structural model

Table illustrates the outcome of the structural model. According to that, the value of R2 that indicates the total variance of the dependent variable explained by the independent variable is 0.500 for impulse buying intention and 0.336 for impulse buying Behavior. These values exceed the recommended value of 0.1. Additionally, it was discovered that, with the exception of the H1, the majority of the factors’ standardized regression path weights were greater than 0.2, and the effect size (f2) values, which assess whether independent variables have a sizable impact on dependent variables, were significant (f2 > 0.02). H2 and H3 were accepted out of three hypotheses, but H1 was rejected. Finally, the SRMR (Standardised Root Mean-square Residual) score of 0.045 indicated that the model had a satisfactory fit. This measurement compares the difference between the actual correlation and the projected correlation as an adjustment assessment for the model.

Table 6. Hypothesis testing results

The model results indicated in Figure states that the social media community does not significantly affect impulse buying intention and impulse buying Behavior. Whereas social media advertisement significantly affects impulse buying intention and impulse buying Behavior. The results also concluded that impulse buying intention significantly affects impulse buying Behavior. Therefore, increasing social media advertisements leads to increased positive impulse intentions, which further leads to increased consumer impulse behavior. The study results indicate a significant positive effect of social media advertisements on impulse purchase intention. However, the social media community doesn’t significantly impact impulse buying intention. Therefore, it can be said that effective advertising on social media with a sound customer engagement strategy can influence impulse buying.

In contrast, the social media community doesn’t consider it an important tool to influence impulse buying. Both SMC and SMA significantly covariate and explain 59.3% variance of each other. Therefore, it can be interpreted that effective advertising on social media can influence community opinion towards companies’ products and services which may drive the consumer’s impulse Behavior.

5. Discussions

The result of the analysis stated that Social Media Community (SMC) does not significantly impact the Impulse Buying Intention (IBI) with a path coefficient value (Beta) of 0.086 at 5 percent significance level. Therefore, the first hypothesis, H1: Social Media Community positively influences the Impulse Buying Intention among Saudi Arabian consumers, was not accepted. The results pointed out that there is no positive impact of the Social Media Community on Saudi Arabian consumers’ impulse buying intentions despite the increasing trend of social platforms and virtual communities in Saudi Arabia. Despite many literature suggested the massive adoption of social media in Saudi Arabia due to various advantages such as easy access and share information and knowledge (Chen et al., Citation2011), Managing social relations and sharing information with others, online communities, and Social Networking Sites (SNSs) have become effective web technology (Lu & Hsiao, Citation2010), create and share valued knowledge with other users (Füller et al., Citation2009), sharing ideas, thoughts, and knowledge in a fraction of a second (Molly McLure & Samer, Citation2005) and better customer engagement (Ridings & Gefen, Citation2004). Still, due to high uncertainty avoidance index of Saudi Arabia consumer, avoidance of uncertainty and risk is very high. They may only show trust and readiness for any new technology if they have enough information about the product to avoid uncertainty (Asiri, Citation2020; Sheikh et al., Citation2017). This could be the potential reason for non-acceptance of the H1.

The impact of SMC on IBI Social media marketing manages customer relations, public relations, promoting products, etc (Stephen & Galak, Citation2010; Tanuri, Citation2010). Social Media Platforms that include social media communities, online discussion forums, and blogs impact the marketing performance of companies (Stephen & Galak, Citation2010). Hence, there is a need to understand the reasons why SMC has no positive influence on Saudi Arabian consumers.

In contrast to H1, Social Media Advertisements (SMA) significantly influence Impulse Buying Intention (IBI) as the value of the path coefficient is 0.653 at 0.01 significant level. Additionally, 55.8 percent variance in IBI is explained by SMA (f2). Therefore, the second hypothesis, H2: Social Media Advertisement positively influences Impulse Buying Intention among Saudi Arabian consumers, was accepted. The results support that SMA positively influences Saudi Arabian consumers’ impulse buying intentions. Moreover, Saudi Arabians, on average, spend more than 2 hours and 30 minutes on social media a day across different devices such as a laptop or smartphones. Among Saudi Arabian users, using social media as a platform for shopping, primarily through Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook, is very common (Asiri, Citation2020). In the context of E-Commerce or shopping through social media in Saudi Arabia, it includes factors such as quality of information, system, service, trust, relationship, and knowledge sharing (Alkenani, Citation2019). Consumers begin to actively participate in social e-commerce after ensuring that the information from the platform is of good quality and necessary and appropriate information is available on the said platform (ALNefaie et al., Citation2019). While purchasing from social media, service elements such as quality of service, assurance, empathy, convenience, and reliability impact consumers’ impulsive buying behavior. These factors contribute to the trust and relationship established on the platform; trust is one of the core elements that encourage Saudi Arabian consumers to purchase from social media platforms like Instagram (Asiri, Citation2020). Lastly, Saudi Arabia consumers are motivated to join social media commerce because of knowledge sharing, which is the foundation for commercial activities that consumers participate in (Alkenani, Citation2019).

Social Media Marketing positively influenced impulse buying behavior among Jordanian consumers, especially women. Moreover, the various products and services offered through social networking sites attract shoppers’ impulsive purchasing behavior. Hence, companies might consider emphasising more on SMA to attract and retain consumers profitably, in the long run, more efficiently. Similarly, Impulse Buying Intention (IBI) significantly predicts the actual Impulse Buying Behavior (IBB) with a path coefficient value of 0.580 at 0.01 significance level. Also, 50.6 percent variance in IBB explained by IBI (f2) further validates the claim. Therefore, the third hypothesis, H3: Impulse Buying Intention positively influences the Impulse Buying Behavior of Saudi Arabian consumers, was accepted. The results indicate that Saudi Arabian consumers are shifting towards impulse buying with a transformation in their buying Behavior due to the positive influence of impulse buying intention. A similar study also confirms the influence of impulse buying in which key factors affecting Impulse buying in Saudi Arabia were identified. These key factors include lower perceived risks such as rewards and discounts, product ratings from other consumers, and the perceived proximity of the product to reality, like zoomable pictures or real-like representations of the products (Moser et al., Citation2019). Additionally, in another study by Karoui and Khemakhem (Citation2019), it is suggested that Saudi Arabian consumer buying behavior was influenced by hedonic variables such as pleasure and happiness. These factors also affect the impulse buying behavior of Saudi Arabian customers (Hashmi et al., Citation2019; Karoui & Khemakhem, Citation2019).

In general, dimensions of impulse buying include hedonic inspiration, variety seeking, website quality and belief (Al-Zyoud, Citation2018). Due to external stimuli, consumers experience an instant desire to purchase without any prior planning. This unexpected and frequent wish to purchase is termed Impulse buying, is hedonically difficult and may boost responsive engagement. Besides, impulse buying is inclined to ensue with moderated concern for its significance on consumer buying (Rook, Citation1987). A connection between the hedonic values of Saudi Arabia consumers and impulse buying has been drawn, and the factors affecting the success of social media in Saudi Arabia are reported. Still, the research gap on how social media influences impulse purchasing in Saudi Arabia calls for further studies on the topic (Alkenani, Citation2019; Hashmi et al., Citation2019; Karoui & Khemakhem, Citation2019). Presently customers are managing social interactions and relations through online forums and communities that directly impact customers’ impulsive buying behavior. Hence, companies and marketers in Saudi Arabia might consider investigating the disruptive behavioral changes in the impulse buying nature of Saudi Arabian consumers.

5.1. Managerial implications

The present research proposes a few administrative recommendations for advertisers. To inspire and increase the tendency of impulse buying amongst consumers, companies should develop an environment wherein consumers can positively respond to impulse buying. To improve the attitude of Saudi customers, businesses can strain reasoned action purchasing and some attractive non-monetary promotion efforts (Rook & Fisher, Citation1995). The present study reveals that impulse buying behaviors of Saudi Arabian consumers are influenced by Social Media Advertising. Hence, it is recommended that advertisers and marketers should expand their social media marketing to enhance the tendency of impulsive buying among consumers. In the present global business scenario, the impulse buying trend is growing and consistent with previous studies, Saudi Arabian consumers show a positive response towards social media advertisements (Winters, Citation1986). Further, it is recommended to the companies that they should create a very good corporate image through social media advertisements and connect their corporate website with social media platforms so that customers can further authenticate the information shared by the companies. Additionally, it will enhance the confidence and belief of their customers. Social media advertisement should be planned so that it can create a long-lasting and unforgettable imprint in the mind of consumers (Baek et al., Citation2014).

5.2. Limitations of the study and future research directions

However, despite its involvement, this study also has some restrictions. First, the study is grounded on one geographic location, and as an outcome of this, consequences are not completely extrapolated and might be evident to be effective only in this background. Consequently, it is endorsed that future studies can be conducted in cross-cultural environments to enhance generalizability. Second, the collected sample size is only 259 respondents, and further studies should be conducted with a larger sample. Furthermore, upcoming studies can identify the role of gender-related transformations along with the varied culture of various countries across the globe. For future studies, scholars can examine the impact of social media advertising on the buying behavior of customers with respect to various types of products or services. Additionally, researchers might discover other variables which can also moderate the path between social media advertising and behavioral intention. These variables, which have not been addressed in the present study, such as product, place, price, promotion, firm-related factors, customer mood, demographics, available time, money and further its impact on impulse buying, can be addressed in future research. Therefore, upcoming studies may possibly consider cultural modifications to assess the roles of gender-related mental and behavioral modifications.

6. Conclusion

The research aimed to measure the impulse buying tendency and investigate the influence of social media on impulse buying intention of customers in the context of Saudi Arabia. The sample considered for the study was social media users. The key findings of this research contradict the preceding study conducted by Chen et al. (Citation2011). Despite so many advantages of the Social Media Community, they identify the product information and recommend it to others (Olbrich & Holsing, Citation2011; Pagani & Mirabello, Citation2011). The flexibility of getting the data can be easily shared with community members sharing product knowledge doesn’t induce impulsive tendencies among social media users (Chen et al., Citation2011). The hypothesis results also conclude that social media advertisements are significantly influencing impulse buying intention. Businesses use attractive content to grab the target market’s attention through memes, images, audio, videos, and blogs for SMA and try to influence consumers to stimulate impulse buying behavior. Bansal and Kumar (Citation2018) suggested that apart from Social Media Advertisement, trust, website quality, and hedonic motivation when used together, will have a substantial impact on impulse buying intention.

The study examined the effects of age and gender on impulse buying intention. It was also observed that age and gender don’t have a significant impact on impulse buying intention. Impulse buying intention decreases with an increase in respondents’ age when shopping on social platforms. However, there is no evidence to accept the impact of gender on impulse buying intention. Hence the respondents cannot be differentiated based on gender. Finally, the study concluded that Saudi Arabian consumers are not impulsive buyers and social media has a limited or nominal impact on their impulse buying behavior. Saudi Arabian consumers carefully plan their purchases in advance and only buy the products and services they think they need, and those products and services have some utility for them. Social media helps to find like-minded people that eventually form an online Social Media Community (Rydell & Kucera, Citation2021; Segran, Citation2017). It has been found that the SMC doesn’t significantly affect Impulse buying intention. Concurrently, Social media users are also exposed to flooded advertisements on social media pages of various companies offering products and related information, which certify the power of social media on consumers’ buying behavior. Therefore, the impact of the SMC and SMA on IBB further needs to be investigated in more detail in varied geographical and sectoral settings so that contemporary businesses may get a cutting edge by developing competitive advantages and surviving in their respective markets for a longer period.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Editors and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive guidance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data is available.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Prakash Singh

Dr. Prakash Singh, an Assistant Professor in the E-Commerce department at the College of Administrative and Financial Sciences, Saudi Electronic University, Saudi Arabia. He holds a Ph.D. in Marketing Management from Savitribai Phule Pune University. With over nine years of experience, he has authored 11 research papers in prestigious journals indexed in Scopus, ABDC, and Web of Science. His research interests span Digital Entrepreneurship, Consumer Behavior, E-Learning, Social Commerce, Mobile Commerce, Customer Engagement, and the Metaverse. He is a blogger, E-content developer, case study developer, and researcher. Dr. Prakash Singh’s teaching approach, which uses Gamification, Learning By Doing (LBD), and a Case-based teaching approach, is highly effective in helping his students learn and succeed. He ensures his students acquire practical skills relevant to the industry.

Bhuvanesh Kumar Sharma

Dr. Bhuvanesh Kumar Sharma PhD., currently holds the position of Assistant Professor with a specialization in Marketing. His primary focus areas encompass Sales and Distribution, Consumer Behavior, and Marketing Research. Dr. Sharma has made significant contributions to his field, with an extensive portfolio of 28 research papers published in reputable National and International journals. Many of his publications have earned recognition by being indexed in prestigious databases including Scopus, ABDC, and UGC. His research interests span a wide spectrum, including but not limited to Social Commerce, Online Buying Behavior, and the intricate dynamics of Social Networking Sites.

Lokesh Arora

Dr. Lokesh Arora is a dedicated educator and seasoned researcher, amassing over 15 years of comprehensive experience spanning both industry and academia. Dr. Arora has made notable contributions to the field, boasting an extensive portfolio of more than 15 research papers published in esteemed National and International journals. Several of these publications have garnered recognition through indexing in prestigious databases like Scopus, ABDC, and UGC. Dr. Arora’s primary areas of research expertise encompass Consumer Behavior, Customer Engagement, Electronic Word of Mouth (eWOM), Social Customer Relationship Management (SCRM), Social Media, and Online Shopping Behavior.

Vimal Bhatt

Dr. Vimal Bhatt PhD., is currently an esteemed Associate Professor with a dedicated focus on Marketing, specializing in Consumer Behavior and Brand Management. His notable accomplishments include the publication of 42 research papers in prestigious National and International journals, a substantial number of which are indexed in renowned databases such as Scopus, ABDC, and UGC. In addition to his research prowess, Dr. Bhatt is actively engaged in the innovative application of Artificial Neural Networks and Deep Learning to predict consumer behavior, showcasing his commitment to advancing the field.

References

- Ahn, J., Lee, S., & Kwon, J. (2020). Impulsive buying in hospitality and tourism journals. Annals of Tourism Research, 82(1), 102764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102764

- Akram, U., Hui, P., Khan, M. K., Yan, C., & Akram, Z. (2018). Factors affecting online impulse buying: Evidence from Chinese social commerce environment. Sustainability, 10(2), 352. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020352

- Alkenani, A. A. N. (2019, March). Factors influencing social e-commerce success in Saudi Arabia-a review. Proceedings of the 2019 6th International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development (INDIACom), 13-15 March 2019, New Delhi, India (pp. 1331–21). IEEE

- Al-Masri, A. R. I. (2020). Impulsive buying behavior and its relation to the emotional balance. International Journal of Psychological and Brain Sciences, 5(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijpbs.20200501.12

- ALNefaie, M., Khan, S., & Muthaly, S. (2019). Consumers’ electronic word of mouth-seeking intentions on social media sites concerning Saudi bloggers’ YouTube fashion channels: An eclectic approach. International Journal of Business Forecasting and Marketing Intelligence, 5(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBFMI.2019.099000

- Al-Zyoud, M. F. (2018). Does social media marketing enhance impulse purchasing among female customers case study of Jordanian female shoppers. Journal of Business & Retail Management Research, 13(2). https://doi.org/10.24052/JBRMR/V13IS02/ART-13

- Amos, C., Holmes, G. R., & Keneson, W. C. (2014). A meta-analysis of consumer impulse buying. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 21(2), 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2013.11.004

- Anderson, M., Sims, J., Price, J., & Brusa, J. (2011). Turning “like” to “buy” social media emerges as a commerce channel. Booz & Company Inc, 2(1), 102–128.

- Applebaum, W. (1951). Studying customer behavior in retail stores. Journal of Marketing, 16(2), 172–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224295101600204

- Aragoncillo, L., & Orus, C. (2018). Impulse buying behavior: An online-offline comparative and the impact of social media. Spanish Journal of Marketing-ESIC, 22(1), 42–62. https://doi.org/10.1108/SJME-03-2018-007

- Asiri, G. (2020). Buyer Behavior toward Instagram based businesses in Saudi Arabia ( Doctoral dissertation). http://hdl.handle.net/10222/79626

- Baek, Y., Ko, R., & Marsh, T., (Eds.). (2014). Trends and applications of serious gaming and social media. Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-4560-26-9

- Bansal, M., & Kumar, S. (2018). Impact of social media marketing on online impulse buying behavior. Journal of Advances and Scholarly Researches in Allied Education, 15(5), 136–139. https://doi.org/10.29070/15/57560

- Barger, V., Peltier, J. W., & Schultz, D. E. (2016). Social media and consumer engagement: A review and research agenda. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 10(4), 268–287. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-06-2016-0065

- Baumeister, R. F. (2002). Yielding to temptation: Self-control failure, impulsive purchasing, and consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(4), 670–676. https://doi.org/10.1086/338209

- Beatty, S. E., & Ferrell, M. E. (1998). Impulse buying: Modeling its precursors. Journal of Retailing, 74(2), 169–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(99)80092-X

- Busalim, A. H., & Hussin, A. R. C. (2016). Understanding social commerce: A systematic literature review and directions for further research. International Journal of Information Management, 36(6), 1075–1088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2016.06.005

- Chawla, A. (2020). Role of Facebook Video advertisements in influencing the impulsive buying behavior of consumers. Journal of Content, Community and Communication Amity School of Communication, 11, 231–246. https://doi.org/10.31620/JCCC.06.20/17

- Chen, Y. F., & Wang, R. Y. (2016). Are humans rational? Exploring factors influencing impulse buying intention and continuous impulse buying intention. Journal of Consumer Behavior, 15(2), 186–197. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1563

- Chen, J., Xu, H., & Whinston, A. B. (2011). Moderated online communities and quality of user-generated content. Journal of Management Information Systems, 28(2), 237–268. https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222280209

- Daniel, E. S., Jr., Crawford Jackson, E. C., & Westerman, D. K. (2018). The influence of social media influencers: Understanding online vaping communities and parasocial interaction through the lens of Taylor’s six-segment strategy wheel. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 18(2), 96–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2018.1488637

- Dessart, L., Veloutsou, C., & Morgan-Thomas, A. (2015). Consumer engagement in online brand communities: A social media perspective. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 24(1), 28–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-06-2014-0635

- Dholakia, U. M. (2000). Temptation and resistance: An integrated model of consumption impulse formation and enactment. Psychology & Marketing, 17(11), 955–982. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6793(200011)17:11<955:AID-MAR3>3.0.CO;2-J

- Djafarova, E., & Bowes, T. (2021). ‘Instagram made me buy it’: Generation Z impulse purchases in fashion industry. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 59, 102345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102345

- Fauser, S. G., Wiedenhofer, J., & Lorenz, M. (2011). Touchpoint social web”: An explorative study about using the social web for influencing high involvement purchase decisions. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 9(1), 39–45.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Füller, J., Mühlbacher, H., Matzler, K., & Jawecki, G. (2009). Consumer empowerment through internet-based co-creation. Journal of Management Information Systems, 26(3), 71–102. https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222260303

- Gaille, B. (2017). 19 dramatic impulse buying statistics. Retrieved March 22, 2017. from https://brandongaille.com/18-dramatic-impulse-buying-statistics/

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Sarstedt, M., Matthews, L. M., & Ringle, C. M. (2016). Identifying and treating unobserved heterogeneity with FIMIX-PLS: Part I–method. European Business Review, 28(1), 63–76. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-09-2015-0094

- Han, M. C. (2023). Checkout button and online consumer impulse-buying behavior in social commerce: A trust transfer perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 74, 103431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103431

- Handayani, R. C., Purwandari, B., Solichah, I., & Prima, P. (2018). The impact of Instagram “call-to-action” buttons on customers’ impulse buying. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, 50–56. https://doi.org/10.1145/3278252.3278276

- Hashmi, H., Attiq, S., & Rasheed, F. (2019). Factors affecting online impulsive buying behavior: A stimulus organism response model approach. Market Forces, 14(1), 19–42.

- Hazari, S., Talpade, S., & Brown, C. O. M. (2023). Do brand influencers matter on TikTok? A social influence theory perspective. Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.2023.2217488

- Heinemann, G. (2023). Meta-targeting and Business ideas in online Retailing. In The new online trade: Business models, business systems and benchmarks in e-commerce(pp. 1–63). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-40757-5_1

- Huang, L. T. (2016). Flow and social capital theory in online impulse buying. Journal of Business Research, 69(6), 2277–2283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.042

- Islam, T., Pitafi, A. H., Arya, V., Wang, Y., Akhtar, N., Mubarik, S., & Xiaobei, L. (2021). Panic buying in the COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-country examination. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 59(March), 102357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102357

- Johan, A., Prayoga, R., Putra, A. P., Fauzi, I. R., & Pangestu, D. (2023). Heavy social media use and hedonic lifestyle, dan hedonic shopping terhadap online compulsive buying. Resmilitaris, 13(1), 2783–2797.

- Joseph, K. G., & Enid, A. (2022). Social media usage and impulse buying tendency in Uganda: The mediating effect of brand community. International Journal of Social Science and Humanities Research, 10(1), 91–97.

- Karoui, S., & Khemakhem, R. (2019). Factors affecting the Islamic purchasing behavior–a qualitative study. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 10(4), 1104–1127. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-12-2017-0145

- Khokhar, A. A., Baker Qureshi, P. A., Murtaza, F., & Kazi, A. G. (2019). The impact of social media on impulse buying behavior in Hyderabad Sindh Pakistan. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Research, 2(2), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.31580/ijer.v2i2.907

- Kollat, D. T., & Willett, R. P. (1969). Is impulse purchasing really a useful concept for marketing decisions? Journal of Marketing, 33(1), 79–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224296903300113

- Koo, D. M., & Ju, S. H. (2010). The interactional effects of atmospherics and perceptual curiosity on emotions and online shopping intention. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(3), 377–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.11.009

- Korkmaz, S., & Seyhan, F. (2021). The effect of social media on impulse buying behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Health Management and Tourism, 6(3), 621–646. https://doi.org/10.31201/ijhmt.994064

- Koski, N. (2004). Impulse buying on the internet: Encouraging and discouraging. Frontiers of E-Business Research.

- Kühn, S. W., & Petzer, D. J. (2018). Fostering purchase intentions toward online retailer websites in an emerging market: An SOR perspective. Journal of Internet Commerce, 17(3), 255–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332861.2018.1463799

- Kusmaharani, A. S., & Halim, R. E. (2020). Social influence and online impulse buying of Indonesian indie cosmetic products. MIX: Jurnal Ilmiah Manajemen, 10(2), 237–248. https://doi.org/10.22441/mix.2020.v10i2.007

- Lavuri, R., & Thaichon, P. (2023). Do extrinsic factors encourage shoppers’ compulsive buying? Store environment and product characteristics. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 41(6), 722–740. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-03-2023-0097

- Lee, G. Y., & Yi, Y. (2008b). The effect of shopping emotions and perceived risk on impulsive buying: The moderating role of buying impulsiveness trait. Seoul Journal of Business, 14(2), 67–92. https://doi.org/10.35152/snusjb.2008.14.2.004

- Li, Y. (2015). Impact of impulsive buying behavior on post impulsive buying satisfaction. Social Behavior and Personality, 43(2), 339–352. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2015.43.2.339

- Li, Y. L., & Jing, F. J. (2012). Post-impulsive buying behavior satisfaction based on the analysis of impulsive buying predisposing factors. Chinese Journal of Management, 9(3), 437–445.

- Lin, S. C., Tseng, H. T., Shirazi, F., Hajli, N., & Tsai, P. T. (2022). Exploring factors influencing impulse buying in live streaming shopping: A stimulus-organism-response (SOR) perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing & Logistics, 35(6), 1383–1403. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-12-2021-0903

- Lo, L. Y. S., Lin, S. W., & Hsu, L. Y. (2016). Motivation for online impulse buying: A two-factor theory perspective. International Journal of Information Management, 36(5), 759–772. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJINFOMGT.2016.04.012

- Lou, C., & Yuan, S. (2019). Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 19(1), 58–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2018.1533501

- Lu, H. P., & Hsiao, K. L. (2010). The influence of extro/introversion on the intention to pay for social networking sites. Information & Management, 47(3), 150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2010.01.003

- Madhavaram, S. R., & Laverie, D. A. (2004). Exploring impulse purchasing on the internet. Advances in Consumer Research, 31, 59–66. http://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/8849/volumes/v31/NA-31

- Madhu, S., Soundararajan, V., & Parayitam, S. (2023). Online promotions and hedonic motives as moderators in the relationship between e-impulsive buying tendency and customer satisfaction: Evidence from India. Journal of Internet Commerce, 22(3), 395–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332861.2022.2088035

- Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). An approach to environmental psychology Cambridge. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Miller, K. D., Fabian, F., & Lin, S. J. (2009). Strategies for online communities. Strategic Management Journal, 30(3), 305–322. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.735

- Molly McLure, W., & Samer, F. (2005). Why should I share? Examining social capital and knowledge contribution in electronic networks of practice. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 35–57. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148667

- Moon, M. A., Farooq, A., & Kiran, M. (2017). Social shopping motivations of impulsive and compulsive buying behaviors. UW Journal of Management Sciences, 1(1), 15–27. https://uwjms.org.pk/downloads/v1/issue1/010102.pdf

- Moser, C., Schoene Beck, S. Y., & Resnick, P. (2019, May). Impulse buying: Design practices and consumer needs. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300472

- Nambisan, P., & Watt, J. H. (2011). Managing customer experiences in online product communities. Journal of Business Research, 64(8), 889–895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2010.09.006

- Nasir, V. A., Keserel, A. C., Surgit, O. E., & Nalbant, M. (2021). Segmenting consumers based on social media advertising perceptions: How does purchase intention differ across segments? Telematics and Informatics, 64, 101687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2021.101687

- Olbrich, R., & Holsing, C. (2011). Modeling consumer purchasing behavior in social shopping communities with clickstream data. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 16(2), 15–40. https://doi.org/10.2753/JEC1086-4415160202

- Ortiz, J., Chiu, T. S., Wen-Hai, C., & Hsu, C. W. (2017). Perceived justice, emotions, and behavioral intentions in the Taiwanese food and beverage industry. International Journal of Conflict Management, 28(4), 437–463. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCMA-10-2016-0084

- Pagani, M., & Mirabello, A. (2011). The influence of personal and social-interactive engagement in social TV web sites. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 16(2), 41–68. https://doi.org/10.2753/JEC1086-4415160203

- Pahlevan Sharif, S., She, L., Yeoh, K. K., & Naghavi, N. (2022). Heavy social networking and online compulsive buying: The mediating role of financial social comparison and materialism. Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice, 30(2), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.2021.1909425

- Parsons, A. G., Ballantine, P. W., Ali, A., & Grey, H. (2014). Deal is on! Why people buy from daily deal websites. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 21(1), 37–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2013.07.003

- Pavlov, P. I. (2010). Conditioned reflexes: An investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex. Annals of Neurosciences, 17(3), 136. https://doi.org/10.5214/ans.0972-7531.1017309

- Pellegrino, A., Abe, M., & Shannon, R. (2022). The dark side of social media: Content effects on the relationship between materialism and consumption behaviors. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 870614. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.870614

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Pradhan, V. (2016). Study on impulsive buying behavior among consumers in supermarket in Kathmandu Valley. Journal of Business and Social Sciences Research, 1(2), 215–233. https://doi.org/10.3126/jbssr.v1i2.20926

- Prentice, C., Chen, J., & Stantic, B. (2020). Timed intervention in COVID-19 and panic buying. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 57(November), 102203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102203

- Rahman, M. S., Bag, S., Hossain, M. A., Fattah, F. A. M. A., Gani, M. O., & Rana, N. P. (2023). The new wave of AI-powered luxury brands online shopping experience: The role of digital multisensory cues and customers’ engagement. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 72, 103273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103273

- Rahman, M. F., & Hossain, M. S. (2023). The impact of website quality on online compulsive buying behavior: Evidence from online shopping organizations. South Asian Journal of Marketing, 4(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAJM-03-2021-0038

- Rehman, F., Ilyas, M., Nawaz, T., & Hyder, S. (2014). How Facebook advertising affects buying behavior of young consumers: The moderating role of gender. Undefined, 5(4), 395–404.

- Reynolds, L., Doering, H., Koenig-Lewis, N., & Peattie, K. (2023). Engagement and estrangement: A “tale of two cities” for Bristol’s green branding. European Journal of Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-08-2021-0602

- Richard, M. O. (2005). Modeling the impact of internet atmospherics on surfer behavior. Journal of Business Research, 58(12), 1632–1642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2004.07.009

- Ridings, C. M., & Gefen, D. (2004). Virtual community attraction: Why people hang out online. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 10(1). JCMC10110. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2004.tb00229.x

- Rodgers, S., Thorson, E., & Jin, Y. (2014). Social science theories of traditional and internet advertising. An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research, 212–234.

- Rook, D. W. (1987). The buying impulse. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(2), 189–199. https://doi.org/10.1086/209105

- Rook, D. W., & Fisher, R. J. (1995). Normative influences on impulsive buying behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 22(3), 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1086/209452

- Rydell, L., & Kucera, J. (2021). Cognitive attitudes, behavioral choices, and purchasing habits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics, 9(4), 35–47. https://doi.org/10.22381/jsme9420213

- Segran, E. (2017). Why hasn’t Zara paid Istanbul workers in over a year? Angry customers want to know. Fast Company Online.

- Sharma, B. K. (2019). Impact of social media on consumer buying behavior with reference to e retailing companies. Jiwaji University. https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in:8080/jspui/bitstream/10603/232122/8/chapter5.pdf

- Sharma, B. K., Mishra, S., & Arora, L. (2018). Does social medium influence impulse buying of Indian buyers? Journal of Management Research, 18(1), 27–36.

- Sheikh, Z., Islam, T., Rana, S., Hameed, Z., & Saeed, U. (2017). Acceptance of social commerce framework in Saudi Arabia. Telematics and Informatics, 34(8), 1693–1708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.08.003

- She, L., Rasiah, R., Waheed, H., & Pahlevan Sharif, S. (2021). Excessive use of social networking sites and financial well-being among young adults: The mediating role of online compulsive buying. Young Consumers, 22(2), 272–289. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-11-2020-1252

- Sherman, E., Mathur, A., & Smith, R. B. (1997). Store environment and consumer purchase behavior: Mediating role of consumer emotions. Psychology & Marketing, 14(4), 361–378. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(199707)14:4<361:AID-MAR4>3.0.CO;2-7

- Shiva, A., & Singh, M. (2019). Stock hunting or blue chip investments? investors’ preferences for stocks in virtual geographies of social networks. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 12(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRFM-11-2018-0120

- Siriaraya, P., Zhang, Y., Wang, Y., Kawai, Y., Mittal, M., Jeszenszky, P., & Jatowt, A. (2019, November). Witnessing crime through tweets: A crime investigation tool based on social media. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGSPATIAL International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems, 568–571. https://doi.org/10.1145/3347146.3359082

- Song, S., Yao, X., & Wen, N. (2021). What motivates Chinese consumers to avoid information about the COVID-19 pandemic?: The perspective of the stimulus-organism-response model. Information Processing & Management, 58(1), 102407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2020.102407

- Stephen, A. T., & Galak, J. (2010). The complementary roles of traditional and social media publicity in driving marketing performance. Fontainebleau: INSEAD working paper collection, 1–40.

- Stern, H. (1962). The significance of impulse buying today. Journal of Marketing, 26(2), 59–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224296202600212

- Tanuri, I. (2010). A literature review: Role of social media in contemporary marketing. Retrieved from: http://www.slideshare.net/groovygenie/role-ofsocial-media-incontemporary-marketing

- Varghese, B. A., & Chitra, S. (2022). The role of social media on impulse buying behavior of customers in Kottarakara Taluk Kerala. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 6(3), 7921–7929.

- Verplanken, B., & Herabadi, A. (2001). Individual differences in impulse buying tendency: Feeling and no thinking. European Journal of Personality, 15(1_suppl), S71–S83. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.423

- Volpi, F., & Clark, J. A. (2019). Activism in the middle East and North Africa in times of upheaval: Social networks’ actions and interactions. Social Movement Studies, 18(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2018.1538876

- Wang, Y. J., Hernandez, M. D., & Minor, M. S. (2010). Web aesthetics effects on perceived online service quality and satisfaction in an e-tail environment: The moderating role of purchase task. Journal of Business Research, 63(9–10), 935–942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.01.016

- Wegmann, E., Müller, S. M., Kessling, A., Joshi, M., Ihle, E., Wolf, O. T., & Müller, A. (2023). Online compulsive buying-shopping disorder and social networks-use disorder: More similarities than differences? Comprehensive Psychiatry, 124, 152392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2023.152392

- Winters, L. C. (1986). The effect of brand advertising on company image-implications for corporate advertising. Journal of Advertising Research, 26(2), 54–59.

- Woodworth, R. S. (1929). Psychology. Henry Holt & Co. Department of Psychology University of Vermont Burlington, Vermont.

- Wu, L., Chiu, M. L., & Chen, K. W. (2020). Defining the determinants of online impulse buying through a shopping process of integrating perceived risk, expectation-confirmation model, and flow theory issues. International Journal of Information Management, 52, 102099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102099

- Wu, Y. L., & Li, E. Y. (2018). Marketing mix, customer value, and customer loyalty in social commerce: A stimulus-organism-response perspective. Internet Research, 28(1), 74–104. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-08-2016-0250

- Xiang, H., Chau, K. Y., Iqbal, W., Irfan, M., & Dagar, V. (2022). Determinants of social commerce usage and online impulse purchase: Implications for business and digital revolution. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 837042. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.837042

- Xiang, L., Zheng, X., Lee, M. K., & Zhao, D. (2016). Exploring consumers’ impulse buying behavior on social commerce platform: The role of para social interaction. International Journal of Information Management, 36(3), 333–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2015.11.002