Abstract

This study investigates the effect of open innovation on firm performance through different types of innovation, namely, product, service, and process innovation. Set in the context of the small and medium enterprise (SME) sector, the study examines SME capabilities obtained from outbound and inbound knowledge flow to adopt innovation. Several studies have demonstrated that the open innovation variable and the type of innovation are some of the most important factors influencing firm performance. This study uses quantitative methods and a research sample of 107 SMEs in Malang City, East Java Province, Indonesia. The results indicate that open innovation has a positive and significant effect on product, process, and service innovation, but does not have a significant direct effect on firm performance. In addition, product innovation and process innovation do not have a significant effect on firm performance; however, service innovation does have a significant effect on firm performance. Furthermore, service innovation is able to mediate the relationship between open innovation and firm performance. The study results and their theoretical and practical implications are also discussed.

1. Introduction

The paradigm of innovation in firms has shifted from a closed strategy to an open strategy (Park & Kwon, Citation2018). The concept of open innovation was adopted by firms several decades ago (Huizingh, Citation2011; Lichtenthaler, Citation2009). Open innovation refers to the idea of integrating external knowledge and ideas into a firm’s innovation process. This concept has been extensively discussed in the literature (Huizingh, Citation2011), and several theories have been proposed to explain the phenomenon. Further, open innovation implies a knowledge flow, which is essential for accessing and integrating external knowledge into a firm’s innovation process (Fisher & Qualls, Citation2018; Sabando-Vera et al., Citation2022). Knowledge-based theory (KBT) provides a theoretical framework for understanding how knowledge flows can facilitate innovation. KBT suggests that knowledge is created and transferred through a dynamic process of externalization, combination, and internalization, which can be facilitated by knowledge flows (Audretsch & Belitski, Citation2023; Sabando-Vera et al., Citation2022). In the context of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in emerging economies such as Indonesia, knowledge flows can be particularly important for facilitating innovation. SMEs often face resource constraints, including limited access to knowledge, technology, and skilled human capital. Therefore, SMEs can benefit from knowledge flows by accessing external sources of knowledge (i.e., customers, suppliers, universities, and research institutions).

In carrying out open innovation, firms must pay attention to the type of innovation capabilities that can be applied by the firm. The adoption of innovation refers to changes that are new to the organization (Pérez-Luño et al., Citation2011). Each type of innovation provides different outcomes for the firm (Dost et al., Citation2016). Although open innovation has been applied by large firms, this is not the case with SMEs (Brunswicker & Vanhaverbeke, Citation2015; Mokter & Ilkka, Citation2016; Vanhaverbeke, Citation2017). In addition, several studies have highlighted that SMEs have innovation barriers, such as a lack of resources, which result in suboptimal performance and competitive advantage (Iqbal et al., Citation2023; Kilay et al., Citation2022; Latifah et al., Citation2022). Unlike large firms, SMEs are also constrained by insufficient resources and capabilities, which pose internal barriers that have an impact on innovation (Rothwell & Dodgson, Citation1991). Meanwhile, the limited resources and capabilities of SMEs in adopting this type of innovation; actually can be triggered both inbound and outbound to produce outcomes from open innovation (Henfridsson et al., Citation2014; Yoo et al., Citation2010).

Firms that innovate––through their products, processes or methods, and services––will experience accelerated development (Koellinger, Citation2008). Supporting this type of innovation is key in promoting business innovation, and thus firm competitiveness (Chibuzo et al., Citation2017). Numerous studies have confirmed a positive relationship between open innovation and firm performance. For instance, studies by Hung and Chiang (Citation2010) and Reed et al. (Citation2012) confirmed this relationship, using profitability as their performance measure. Chiesa et al. (Citation2008), using research and development (R&D) performance as a measure, found a similar relationship. Moreover, Rohrbeck et al. (Citation2009), who adopted new product success as a performance measure, provided further support for the relationship. However, there are also research findings that suggest otherwise. Laursen and Salter (Citation2006) and Torkkeli et al. (Citation2009) are two important works that found negative effects of open innovation activity on firm performance.

Despite the premise of this study that open innovation is positively related to firm performance, there is no consensus on the direction of this relationship, and various research efforts have reported inconclusive results. The relationship between open innovation and firm performance is not simple; indeed, it is complex. Open innovation has been widely recognized in many studies, but the available evidence seems to focus primarily on the direct effect of open innovation on firm performance (Hung & Chiang, Citation2010; Laursen & Salter, Citation2006; Poot et al., Citation2009). Other studies on open innovation and different types of innovation in SMEs have tended to focus on product innovation or one particular type of innovation (Brunswicker & Vanhaverbeke, Citation2015; De Marco et al., Citation2020; Kapetaniou & Lee, Citation2019; Maes & Sels, Citation2014; Parida et al., Citation2012; Spithoven et al., Citation2013). Consequently, there is no clarity on inbound and outbound open innovation that is centered only on SME product development. Therefore, the various typologies of innovation pursued by SMEs have been largely ignored (Hervas-Oliver et al., Citation2021). In light of this, examining internal and external sources in open innovation activities is necessary because external sources of knowledge for SMEs depend on internal capabilities (Brunswicker & Vanhaverbeke, Citation2015). The literature on open innovation in SMEs has demonstrated that firms succeed in aligning these two sources of knowledge; consequently, the internal capabilities related to business strategy are needed (Brunswicker & Vanhaverbeke, Citation2015; Hervas-Oliver et al., Citation2014) to be able to influence the appropriate type of innovation and have implications for firm performance (Mamun, Citation2018).

Given the research gaps identified in the previous paragraph, the two objectives of this study are to (i) examine whether open innovation affects three different innovation types and (ii) investigate whether open innovation affects firm performance. To address these objectives, the study examines the literature on the outcomes of open innovation and the antecedents of firm performance. The study proposes that the type of innovation (product, process, or service) is a potential mediator between open innovation and firm performance in SMEs. It is posited that the inconsistent relationship between open innovation and firm performance can be overcome by the presence of a mediating variable (Baron & Kenny, Citation1986). In this case, the relationship between open innovation and firm performance is highly dependent on the performance of each type of innovation. Thus, the relationship is not direct, but depends on the type of innovation produced. The higher the open innovation, the higher the performance of each type of innovation produced, and the higher the firm’s performance.

2. Literature review

2.1. Knowledge-based theory

KBT has been widely discussed in the management literature. The theory emphasizes intangible resources and how these are collectively shared and applied, which is a function of the firm’s know-how (Alavi & Leidner, Citation2001; Grant, Citation1996). Unlike in large firms, SMEs can only allocate limited resources, and these are often constrained by tangible resources. KBT is rooted in a resource-based view, which focuses on a firm’s strategic assets (i.e., tangible and intangible) as the main source of competitive advantage (Gök & Peker, Citation2017). KBT emphasizes knowledge-based resources, which are used as the main strategic resources; if these are managed properly, they allow firms to create value by exploiting their production (Crook et al., Citation2011). In the context of SMEs, when properly exploited, knowledge provides different values from various knowledge flows, and these are important for business continuity.

Various studies argue that KBT is difficult to imitate and socially complex; thus, the diverse knowledge base and capabilities of SMEs are the main determinants of sustainable competitive advantage (Alavi & Leidner, Citation2001; Fachrunnisa et al., Citation2020; Fisher & Qualls, Citation2018). To create a sustainable competitive advantage and outperform competitors, a performance dimension may need to coexist with capabilities and innovation. The main point of KBT is the absorption and configuration of appropriate knowledge leads to higher performance (Barney, Citation1991; Grant, Citation1996; Kogut & Zander, Citation1992). Knowledge and capability development are widely discussed in the organizational knowledge management literature (Schütz et al., Citation2020), and are largely rooted in a knowledge-based view.

In the context of open innovation, KBT suggests that firms can benefit from accessing and integrating external knowledge into their existing knowledge base. KBT proposes that firms should leverage their existing knowledge and capabilities to absorb, integrate, and apply external knowledge to their innovation process (Curado et al., Citation2018). In addition, KBT highlights the importance of knowledge transfer mechanisms, such as knowledge spillovers, interorganizational networks, and collaborative partnerships (Fachrunnisa et al., Citation2020. These mechanisms can facilitate the exchange and integration of external knowledge into a firm’s innovation process, enhancing innovation performance (Heenkenda et al., Citation2022; Wang et al., Citation2022).

Overall, KBT provides a theoretical framework for understanding how knowledge is created, shared, and applied in the context of open innovation. It emphasizes the importance of knowledge as a critical resource for firms to innovate and compete in today’s dynamic and complex business environment. Based on the literature, open innovation highlights the importance of knowledge flows in facilitating innovation (Ham et al., Citation2017; Kilay et al., Citation2022; Prabowo et al., Citation2020). The concept of knowledge flows refers to the movement of knowledge (Hughes et al., Citation2022) between individuals, firms, and other entities. This can occur through various channels, such as collaborations, networks, or knowledge spillovers. KBT provides a theoretical framework for understanding how knowledge flows can be aligned with a firm’s absorptive capacity to enable effective innovation. In the context of SMEs in emerging economies, knowledge flows can be particularly important for accessing external knowledge and resources, which can support innovation and competitiveness.

2.2. Open innovation

Innovation is a key determinant of a firm’s success (Ramadani et al., Citation2019; Tse et al., Citation2015). Firms that do not innovate will decline in terms of performance or may even go bankrupt (Ratten, Citation2016; Wilkinson & Thomas, Citation2014). Adopting innovation refers to the “successful exploitation of new ideas”. This combines (i) new ideas: involving new products or processes or services; (ii) exploitation: the application of ideas; and (iii) success: innovation is adopted by the market from the point of view of the target firm regarding increasing profitability (Rivard, Citation2000). According to the open innovation paradigm introduced by Chesbrough (Citation2003), firms are becoming increasingly aware of the need to interact with a broad knowledge landscape. This forms the basis for integrating the firm’s internal R&D and highlights the importance of managing outbound flows for knowledge and technology. Further, Chesbrough and Bogers (Citation2014) state that open innovation is a distributed innovation process that involves managing the flow of knowledge across organizational boundaries. From this perspective, internal R&D is just as important as gathering external knowledge from other sources. However, this approach plays a limited role in shaping the innovation strategies of most firms. In contrast, Fu et al. (Citation2019) approach open innovation as a corporate strategy that uses external innovation resources as well as internal innovation resources, and internal and external channels to the market to increase innovation capabilities. In some industries, large firms conduct open innovation activities through collaboration with other organizations with the aim of developing their technology (Chen et al., Citation2011).

A firm whose internal innovation involves external organizations can include some knowledge, competencies, and technology, or it can actively collaborate (Greco et al., Citation2016). When moving to an inbound open innovation strategy, a firm tries to look beyond the bounds of a skill, competency, or technology it does not have; to implement it internally would require too much cost, effort, and time. This reinforces the perception that a given inbound open innovation strategy is effective in increasing firm innovation. Therefore, it is important for firms to carry out innovation strategies through the inbound and outbound aspects of open innovation.

2.3. Types of innovation

Innovation can take several forms, depending on the basis used to distinguish it. Rodríguez and Pérez (Citation2004) classify it as external or internal. According to the impact of innovation based on the theory of evolution (Buitelaar, Citation1988), it is classified as either incremental or radical and disruptive. Further, innovation can be divided into product innovation, process innovation, or service innovation (Banbury & Mitchell, Citation1995). Based on these classifications, to be identified as such, innovation must be introduced into the market, just like product innovation, or it must be applied in the firm’s operations as is the case for process innovation, methods and levels of service improvement (both to suppliers and marketing customers), thus service innovation is required (OECD, Citation2007). In this study, the latter classification is used, namely, that process innovation, product innovation, and service innovation are classic types of innovation that are widely studied in the literature on different innovation typologies.

2.3.1. Product innovation

Product innovation, as explained by Schumpeter (Citation1934), is the introduction of a completely new product or new product quality to customers who are not familiar with it. Product innovation is realized by providing new goods or services, or a significant increase in technical capabilities, their use or other functions (Porter, Citation2003). This improvement is achieved by means of knowledge or technology, by upgrading materials or components, or by integrated computing. To be considered innovative, a product must display certain characteristics and performance that differentiates it from existing products, including improvements in service. Thus, product innovation refers to the introduction of new products or services, or to changes in products and services. Process innovation is related to how to carry out production or service operations; it changes or improves the way organizations work. Product innovation aims to present new or better products or services to customers, who note the impact of these innovations on the products or services they receive.

Product innovation leverages new knowledge or technology or a combination of existing knowledge or technology. The term “product” refers to both goods and services. Product innovation is a difficult process driven by technological advances, changing customer needs, shortened product life cycles, and increasing global competition. Process innovation is a method of production or delivery that is new or significantly improved, introduced for the added benefit of the customer or to meet market needs. This includes significant changes in technique, equipment and/or software. Process innovation is intended to lower unit production or delivery costs, improve quality, or produce or deliver a new or significantly improved product. Product innovation can be used to strategically differentiate an organization’s product offerings in the marketplace, thereby meeting market demand, building customer loyalty, and improving firm performance. Process innovation reflects the process of renewal in organizations (Huang & Rice, Citation2012).

2.3.2. Process innovation

According to Schumpeter (Citation1934), process innovation refers to new production methods and/or new ways of commercially managing commodities. Process innovation stems from internal production goals, and that includes reducing production costs and increasing the quantity and quality of output. Process innovation, a concept applied to both the production and distribution sector, is achieved through significant changes in the techniques, materials and/or computer programs used by a firm. These aim to reduce production or distribution costs, improve quality, or produce or distribute new or significantly improved products. Process innovation also includes new or significantly improved techniques, equipment, and computer programs that are used in additional support activities, such as purchasing, accounting, or maintenance. Process innovation intends to increase the efficiency and/or quality of basic supporting activities. Thus process innovation can be reflected in the introduction of new tools, methods, or knowledge to create products or services. Therefore, process innovation focuses on increasing efficiency or reducing costs so that the price of a product attracts customers and encourages them to buy it (Cheng & Huizingh, Citation2014). This process is necessary to provide goods or services that are not specifically paid for by consumers. Therefore, system innovation is an innovative shift in the manufacturing or distribution goods that allows the value provided to stakeholders to substantially increase (Deloitte, Citation2017; Veugelers & Wang, Citation2019).

2.3.3. Service innovation

Service innovation focuses on creating new value through service design and delivery methods (Toivonen & Tuominen, Citation2009). Therefore, service innovation reflects a firm’s willingness and capacity to satisfy customers through a dynamic combination of service elements (Den Hertog et al., Citation2010; Kunttu & Torkkeli, Citation2015). A firm’s service innovation varies with its ability to understand customer needs and technology choice, to conceptualize (customer reaction to service innovation), to combine capabilities (new configurations of existing elements), and to co-produce and organize (rapid service innovation). A firm’s service innovation capacity varies with its ability to understand customer needs and technology choices to conceptualize (customer reaction to service innovation), combine capabilities (new configurations of existing elements), co-produce and organize (service innovation across borders), measure and expand, and ultimately, and learn and adapt (Den Hertog et al., Citation2010). Service innovation enables firms to gain a competitive advantage by offering professional services. According to Flikkema (Citation2008), service innovation is a multidisciplinary process in designing, realizing, and marketing combinations of existing and/or new services and products that are tested to create value for the customer.

2.4. Firm performance

Firm performance can be characterized as the firm’s ability to create acceptable results and achieve its goals (Gharakhani & Mousakhani, Citation2012). Ho (Citation2008) defines organizational performance as the manner in which organizations achieve their goals. According to Schütz et al. (Citation2020), performance refers to how an organization achieves its goals through the quality and quantity of good work achieved by individuals and groups.

2.5. Relationship between open innovation and firm performance

Open innovation has been recognized as an important approach to the systematic internal and external implementation of key technology management tasks (Hung & Chou, Citation2013; Lichtenthaler, Citation2009). It can be divided into two types: inbound and outbound (Bianchi et al., Citation2016; Chesbrough & Crowther, Citation2006; Hao-Chen et al., Citation2015). Inbound innovation refers to the extent to which firms access technology or external resources available to complement existing resources. This type of innovation increases the options for new product development input and advances effective new product processes, both of which facilitate corporate performance (Bravo et al., Citation2017; Van de Vrande et al., Citation2009). Outbound innovation or the exploitation of external technology refers to the commercialization of firms or the transfer of external technology outside for profit (Camerani et al., Citation2016; Olk et al., Citation2017). This type of innovation highlights the firm’s goal of commercializing ideas and technology by channeling them to external markets. Such an approach can help firms build industry standards (Lichtenthaler, Citation2009) and earn revenue from annual licenses (Chesbrough & Crowther, Citation2006). The strategy literature points to both external knowledge acquisition and exploitation as central to firm competitive advantage. In this study, we focus on open innovation that is both inbound and outbound.

In an empirical analysis of the South Korean SME manufacturing sector, Yun et al. (Citation2018) revealed that open innovation improves firm performance. The study indicated that SME R&D investment has a significant effect on performance in the short term as well as on open innovation activities. However, in the medium and long term, this effect is significantly reduced. Focusing on SMEs in the health care IT sector, Kim and Kim (Citation2018) report that firms need to have innovative technology and must be able to commercialize technology for sustainable growth. Some SMEs cooperate with other firms in the production process, as an open innovation system. However, this is sometimes difficult and comes with certain risks. Therefore, SMEs develop high-quality patents and collaborative strategies with external firms to improve their innovation performance. Hernandez-Vivanco et al. (Citation2018) examined 220 Spanish firms and the role of open innovation and innovation management systems in their pursuit of innovation.

The relationship between innovation and firm performance has been studied from the point of view of innovative sales productivity. Andres et al. (Citation2017) analyzed data from 48 specialized SMEs involved in supercar manufacturing. The authors point out that the adoption of open innovation models and practices enhances corporate innovation and improves SME performance. Hao-Chen et al. (Citation2013) analyzed 141 manufacturing SMEs in Taiwan and assessed how open innovation practices influence the likelihood of change if organizational turbulence occurs, as well as how they can generate new business models. Further, based on a survey of Malaysian high-tech SMEs, Hameed and Naveed (Citation2019) revealed that competition increases a firm’s open innovation performance. Ferdinand and Meyer (Citation2017) analyzed the dynamic relationship between openness and firm performance, showing that openness will have an impact on firm performance. Ahn et al. (Citation2018) emphasized that the positive effect of openness on firm performance can continue in the long term. Indeed, increased transparency increases a firm’s dynamic capabilities and resilience.

Increased collaboration with other firms has a strong effect on turnover recovery, as collaboration with new partners increases the ability to change and increases the acquisition of new knowledge. Mauro et al. (Citation2016) studied the relationship between corporate openness and innovation and financial performance. The authors found that the ratio between R&D productivity and revenue from patents decreased with high disclosure, while patent growth was not influenced by the implementation of open innovation activities. Further, sales growth showed a positive trend with respect to openness, while operating profit and turnover decreased with the implementation of open innovation. However, researchers such as Belderbos et al. (Citation2009) highlight the possible negative effects of this practice on financial performance. Indeed, although collaborative R&D activities can reduce risks and technical costs, engaging in R&D collaboration with external partners may pose relational risks and increase coordination costs (Das & Teng, Citation1998). To reduce these risks, firms need time-consuming contract negotiations or the implementation of expensive monitoring mechanisms. In addition, because of cultural and organizational differences among different partners, it may be necessary to make relational investments to facilitate coordination.

From these studies, it can be concluded that openness is an important prerequisite for innovation. However, the relationship between open innovation and firm performance is not always direct and is context dependent. The main focus of the open innovation literature is when and how an open innovation strategy improves firm performance. The model developed in this study uses a mediating factor in the type of innovation performance in both products, processes, and services. Consequently, we posit that open innovation does not have a direct effect on firm performance and propose the following hypothesis:

H1

Open innovation has no direct effect on firm performance.

2.6. Relationship between open innovation and type of innovation

Prior research has shown that a firm can advance its innovation performance by interacting with different partners, including suppliers, customers, competitors, and research organizations (Hung & Chiang, Citation2010; Laursen & Salter, Citation2006). For example, some scholars confirm that collaboration with suppliers is beneficial for firm innovation because of the combination of complementary capabilities and shared goals between firms and suppliers (Hwang & Lee, Citation2010; Laursen & Salter, Citation2006). These studies have found that innovation performance increases with the breadth and depth of external searches, namely, the diversity of external information sources searched for by firms, such as suppliers and customers, and the intensity of their use. In addition, some scholars have found that collaboration with research institutions and universities has a positive effect on product innovation performance (Hung & Chiang, Citation2010; Tsai, Citation2009). Research institutions have systems and mechanisms that facilitate access to new and complex knowledge.

Along with the positive influence of inbound open innovation on corporate innovation, many studies suggest that the role of external knowledge acquisition may have a negative effect on firm innovation output (Inauen & Schenker‐Wicki, Citation2012). Reasons behind this negative relationship include insufficient absorptive capacity (Cohen & Levinthal, Citation1990) of firms to integrate emerging knowledge and technology from other industries, or the drainage of resources created by external knowledge acquisition. Therefore, we formulate the following hypotheses:

H2:

Open innovation has a significant effect on product innovation.

H3:

Open innovation has a significant effect on process innovation.

H4:

Open innovation has a significant effect on service innovation.

2.7. Relationship between type of innovation and firm performance

Product and service innovation is a key success driver, providing opportunities to expand into new markets and sectors (González-Blanco et al., Citation2019; Salunke et al., Citation2019). This form of innovation also helps businesses to explore opportunities to make significant profits (Koloniari et al., Citation2018). It is imperative for service firms to continually update their operating systems, business models, and value propositions in response to dynamic changes in a customer-centric culture and an increasingly technology-driven economy. Firms should also consider pursuing ongoing comprehensive product or service transformations, legacy structures, and business processes to accelerate sales growth, ensure financial stability, enhance customer experience, and fend off increasing competition (Ramadani et al., Citation2019). Prior research has examined the relationship between the type of innovation and firm performance. Mothe and Thi (Citation2010) state that both revolutionary and incremental innovation can contribute to firm results, while Guisado-González et al. (Citation2016) show that creativity has a positive effect on business success. Therefore, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H5:

Product innovation has a positive effect on firm performance

In relation to process innovation and firm performance, a study conducted by Horvat et al. (Citation2019) in various industrial sectors in Malaysia revealed that both product and process innovation are positively related to firm performance, although the former has a more significant effect. Process innovation maintains product features, but reduces the percentage of stable production costs (Kuo et al., Citation2017). Progress in process innovation results in lower costs and product prices, which in turn puts pressure on profitability and increases product attractiveness (Rosli & Sidek, Citation2013). Process innovation results in extra productivity growth at every level. Moreover, technology-based product quality make it easier for businesses to achieve superior results in innovation. Therefore, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H6:

Process innovation has a positive effect on firm performance.

Service innovation focuses on creating new value through service design and delivery methods (Toivonen & Tuominen, Citation2009). According to Den Hertog et al. (Citation2010), a firm’s service innovation capacity varies with its ability to understand customer needs and technology choices, to conceptualize customer reactions to service innovation, to combine capabilities, to create new configurations of existing elements, and to co-produce and organize rapid innovation service. Service innovation gives firms the opportunity to gain a competitive advantage by offering products and services combined with the right solutions. In the context of banking, firms used service innovation to improve services and efficiency of operations (Ibrahim & Yusheng, Citation2020).

According to Flikkema (Citation2008), service innovation is a multidisciplinary process of designing, realizing, and marketing combinations of existing and/or new services and products that are tested to create customer experience value. The link between the type of innovation and firm performance in the service sector shows a positive relationship. In research on hotel service innovation in Taiwan, it was found that the relationship between customer focus and service innovation led to successful innovation (Distanont et al., Citation2019; Makri et al., Citation2017). The findings also indicate that product innovation has a fully mediating impact on performance outcomes. Further, the reliability, features, and novelty of firms’ competitors can also result in product innovation, rather than increasing the efficiency of the firm as a whole to improve the quality of new goods or services. Similarly, Miles et al. (Citation2017) examined banking sector innovations and found that product innovation increases productivity, whereas process innovation increases both productivity and effectiveness. Therefore, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H7:

.Service innovation has a positive effect on firm performance

2.8. Mediating role of the type of innovation

The mediation model for this study was developed in accordance with prior research (Benner & Tushman, Citation2003). The effect of open innovation on the degree of innovation type has been comprehensively examined in prior empirical studies (see Outer Model). This study also emphasizes the influence of the type of innovation on firm performance (see Structural Model). Other studies have found a mediating effect of innovation on the relationship between strategic orientation and firm performance (Nurlina, Citation2014). The study of Mamun (Citation2018) examines the mediating effect of innovation on the relationship between persuasion, strategic orientation, firm characteristics, and the performance of manufacturing SMEs in Peninsular Malaysia. The study reveals that innovation adoption mediates the relationship between persuasion, innovation, and SME performance. It also demonstrates that the adoption of innovation significantly affects the relationship between strategic orientation and the performance of SMEs. Based on the findings of study on Mamun, we formulate the following hypotheses:

H8:

Product innovation mediates the relationship between open innovation and firm performance.

H9:

Process innovation mediates the relationship between open innovation and firm performance.

H10:

Service innovation mediates the relationship between open innovation and firm performance.

3. Method

3.1. Sample and data collection

This study uses quantitative research methods and explanatory research to collect information from SMEs in Malang City, East Java Province, Indonesia. The quantitative method is used to test objective theory by considering the relationships between variables (Creswell, Citation2009). The study sample was obtained from the Malang City Office of Cooperatives, Industry, and Trade database. The sample calculation in this study was obtained using the Slovin formula, with 107 SMEs selected out of a total population of 457. Further, in determining sample size, this study used an online sample size solution that determines the number for a minimum sample size, namely, n = 107 (www.qualtrics.com). Thus, this questionnaire was designed and distributed to 107 owners or top managers of SMEs in Malang City. We also followed Huber and Power (Citation1985) regarding the determination of respondents to minimize possible sources of error in construction measurement. Therefore, this study identified and arranged contact personnel who could be contacted at the managerial level, or by browsing websites and social media. The selection of these SMEs was a deliberate choice as it was expected that they would have the necessary information, knowledge, and experience––based on their position in the business––with regard to management strategy (marketing, finance, and production) and SME resources. After identifying the sample, the distribution of the questionnaires could be carried out directly (offline).

3.2. Measurement

The questionnaire was designed with reference to prior studies conducted in the same context (See Appendix). Open innovation was measured using nine items developed by Hung and Chou (Citation2013). Each type of innovation (product, process, and service) was measured by three items adopted from Mamun (Citation2018). The firm performance variable was measured using four items developed by Hanaysha (Citation2020). All items used were measured on a Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” The results of these measurements are shown in Table .

3.3. Data analysis

In this study, using statistical analysis as a means of inquiry, Smart-PLS was used to provide descriptive and inferential statistic. According to Hair et al. (Citation2017), Smart-PLS is a non-parametric multivariate approach used to estimate pathway models with latent variables. Smart-PLS is a powerful statistical tool because it can be applied to all data scales, does not require many assumptions, and confirms the relationship without a solid theoretical foundation (Avkiran, Citation2018; Hair et al., Citation2014). In Smart-PLS, the analysis includes the simultaneous assessment of measurement models and structural models. The model measurements were assessed to determine internal consistency reliability (composite reliability), convergent validity (loading factor and average variance), and discriminant validity (Hair et al., Citation2017). Using Smart-PLS provides a stronger estimate of the structural model compared with other approaches, especially when assumptions are violated (Hair et al., Citation2014). Another advantage is that the sample size does not have to be large. Table shows the results of the construct measurements in this study, which were analyzed using Smart-PLS.

4. Results and analysis

4.1. Description of respondents

Based on the descriptive analysis, it was possible to determine the profile of the respondents (see Table )

Table 1. Respondents’ profile

The SMEs were characterized based on Law Number 20 (Citation2008), which classifies SMEs based on several criteria, as shown in Table .

Table 2. Classification of SMEs in Indonesia

4.2. Outer model

Table shows the results of the construct measurements in this study which were analyzed using Smart-PLS. From the results of the outer loading of all items, it can be concluded that all items are valid because all are above 0.50 and reliability is above 0.70 (Hair et al., Citation2014). Moreover, all variables are reliable, in line with Cronbach’s α, composite reliability was above 0.70, and average variance extracted was above 0.50.

Table 3. Reliability and validity analysis

4.3. Discriminant validity

To validate the measurement model, this study assessed the discriminant validity of constructs. Discriminant validity is assessed by comparing the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) values with the latent variable correlations (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Hair et al., Citation2014). As shown in Table below, the square root of AVE for each construct is greater than the correlations with other constructs in this study. Thus, the constructs assessed in this study have demonstrated strong validity values, and the discriminant validity scores for each construct were higher than the correlations with other constructs in the model.

Table 4. Discriminant validity

4.4. Structural model

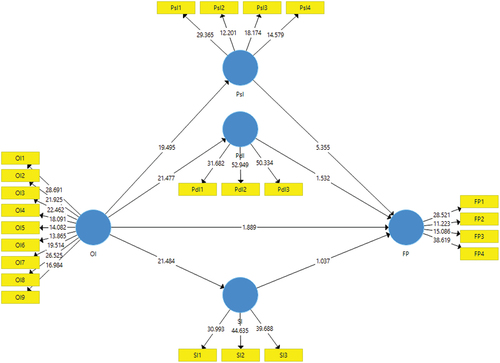

This study also presents statistical analysis results of the hypothesis testing, either directly and indirectly, between open innovation and firm performance. Furthermore, Smart-PLS determines the model-fit and path coefficient as individual magnitudes, used to determine the overall relationship (Hair et al., Citation2019), As illustrated in Figure , the output of the research model in this study is observed. In the partial model, Smart-PLS results in coefficient determination (R2) of product innovation (0.727), process innovation (0.744), service innovation (0.737), and firm performance (0.820). Table shows the statistical results of directly testing the hypotheses, while Table shows the indirect effect.

Table 5. Hypotheses testing of direct effect

The direct effect of open innovation on firm performance (β = 0.194; p-value >0.05) shows insignificant results; thus H1 is accepted. Based on the results of the above analysis, the direct effect of open innovation on product innovation (β = 0.853; p-value <0.05), process innovation (β = 0.863; p-value <0.05), and service innovation (β = 0.859; p-value <0.05) is a positive and significant effect; thus, H2, H3, and H4 are accepted. The effect of product innovation on firm performance (β = 0.133; p-value >0.05) and the effect of service innovation on firm performance (β = 0.097; p-value >0.05) is positive but not significant; thus, H5 and H6 are rejected. Finally, the effect of process innovation on firm performance (β = 0.518; p-value <0.05) has a positive and significant effect; thus, H7 is accepted. Based on the results of the direct relationship analysis, when SMEs exploration of knowledge can be utilized to improve internal capabilities, thereby affecting their ability to innovate (e.g., product, process, and service) (Bianchi et al., Citation2016; Chesbrough & Bogers, Citation2014). However, the effectiveness and efficiency of innovation output cannot directly affect firm performance. In contrast, process innovation does influence firm performance, but products and services are not necessarily accepted by the market (Park & Kwon, Citation2018).

In the statistical analysis testing the indirect relationship, the three variables (i.e., product innovation, service innovation, process innovation) were the intervening variables between open innovation and firm performance (See Table ). Based on these results, product innovation (β = 0.114; p-value >0.05) and service innovation (β = 0.083; p-value >0.05) mediate positively but not significantly between open innovation and firm performance; thus, H8 and H10 are rejected. However, process innovation (β = 0.447; p-value <0.05) positively and significantly influences open innovation and firm performance; thus, H9 is accepted. This study emphasizes that open innovation cannot have a direct effect on firm performance, which leads to the resultant innovation output. Hence, in influencing firm performance, open innovation is mediated by the type of innovation produced. Thus, open innovation and the type of innovation are predictors of firm performance. Further, Iqbal et al. (Citation2023) revealed that the ability of SMEs to pursue certain performance thresholds is an important capability that will improve performance. This is especially the case for SMEs in developing countries, which still have a product or service orientation. In other words, both product and service are mediators of the relationship between open innovation and firm performance; however, the effect is not significant, as confirmed by Iqbal et al. (Citation2023). In addition, process innovation significantly mediates the effect of open innovation and firm performance, enabling SMEs to make cost efficiencies with a significant impact on the firm’s financial performance.

Table 6. Hypotheses testing of indirect Effect

5. Discussion and implications

5.1. Discussion

In recent years, open innovation has attracted attention in relation to innovation management in SMEs. This study uses variables that have been investigated in previous studies (Hannigan et al., Citation2018), and demonstrates that open innovation is related to the type of innovation adopted by SMEs. Thus, the study investigates the role of open innovation on different types of innovation (e.g., product, process, and service innovation). The results indicate that open innovation has a positive and significant relationship with product innovation. In carrying out open innovation, SMEs require both inbound and outbound knowledge (Bianchi et al., Citation2016; Chesbrough, Citation2003; Chesbrough & Crowther, Citation2006; Popa et al., Citation2017). The influence of open innovation encourages SMEs to adopt different types of innovation, for example, in terms of products. This knowledge will provide access to existing resources to develop product innovations, replacing products that have been used previously (Chesbrough, Citation2003). This study also demonstrates that open innovation has a positive and significant effect on service innovation. In line with research by Mina et al. (Citation2014), the results reveal that open innovation has a positive and significant relationship with service innovation. The success of this innovation effect stems from the effectiveness of the combination of knowledge from inbound and outbound flows (Carroll & Helfert, Citation2015).

The study also demonstrates the influence of knowledge management on the firm, which is able to create service innovation (De Zubielqui et al., Citation2019). Further, service innovation creates new value through service design and delivery methods to customers (Toivonen & Tuominen, Citation2009). Therefore, it can also lead to customer relationship management and customer retention (Kunttu & Torkkeli, Citation2015). Process innovation is the most crucial for SMEs to achieve competitiveness through the resultant innovation. The study results reveal that open innovation has a positive and significant effect on process innovation. This finding is confirmed by Tsinopoulos et al. (Citation2017). Open innovation assists firms to collaborate with other organizations and increase resources, making it easier to access resources that are not owned by the firm (Luo et al., Citation2004; Srivastava & Gnyawali, Citation2011). However, firms can also gain knowledge from external factors, which can increase process innovation (Un & Asakawa, Citation2015). An example is when suppliers provide technology, investment, and know-how for firms (Potter & Lawson, Citation2013) to advance development projects.

Further, Laursen and Salter (Citation2006) investigated the effect of open innovation on firm performance. However, the results of this study are consistent with Koellinger (Citation2008), who states that firms that carry out open innovation may not necessarily improve firm performance or increase profits. The present study highlights this point, namely, that open innovation does not directly affect firm performance, but rather, this occurs through the influence of the mediating variable of the type of innovation. Open innovation allows knowledge and innovation resources to flow from inbound and outbound innovation, and has become the dominant approach to revitalizing corporate innovation (Chesbrough, Citation2003; Garriga et al., Citation2013). In fact, several studies have examined the influence of open innovation on firm performance by highlighting strategic orientation (Cheng & Huizingh, Citation2014), innovation outcomes (Zhang et al., Citation2019), social networks (Sisodiya et al., Citation2013), and environmental turbulence (Hung & Chou, Citation2013).

Resource-Based View maintains that firms seek to further develop and strengthen competitive advantage (Barney, Citation1991). Therefore, open innovation requires firms to effectively manage knowledge into intangible resources and use these to achieve competitive advantage. This refers to the extent to which a firm is able to acquire knowledge and transform it into intangible resources (Sears & Hoetker, Citation2014). However, some studies highlight the ability to manage information and knowledge, which is referred to as a firm’s knowledge management capability (Hung & Chou, Citation2013). Thus, corporate strategy plays a central role in dealing with problems, both in terms of competition and in business processes. Hung and Chou (Citation2013) confirm the importance of knowledge management capability, which can affect firm performance.

In terms of the direct relationship between different types of innovation (product, process, and service) and their effect on firm performance, as well as their mediating role, only process innovation has a positive and significant influence, while product and service innovation do not. This study is based on the findings of Sharma and Lacey (Citation2004), which show that product innovation does not necessarily have a significant effect on firm performance. This is because it is impossible for product innovation to benefit the firm in a short period of time; as stated by Srinivasan et al. (Citation2009), this depends on market identification and brand value. Product innovation is an important factor for SMEs; it positively affects the target market, thereby reducing the possibility of bankruptcy (Banbury & Mitchell, Citation1995). Product innovation in SMEs mostly focuses on improving efficiency or reducing costs to increase customers’ willingness to pay for products. This is especially in the Indonesian market, where consumers tend to buy products that are cheaper and according to the value they can afford. For SMEs, product innovation also increases their ability to survive with shorter product life cycles, demand volatility, and rapid technological changes (Godener & Söderquist, Citation2004; Mamun, Citation2018). Further, when product innovation is successfully created, consideration must also be given to launching products as well as marketing and branding strategies (Kotler et al., Citation2019).

In relation to product innovation, product efficiency is associated with process innovation. The inefficiency of product innovation has implications for firm performance, which is influenced by process innovation, which, in turn, increases production costs (Mamun, Citation2018). However, it could be the other way around; when process innovation has reduced costs, it can improve firm performance. Therefore, these results show that there is also a relationship between process innovation and firm performance, which has a positive and significant effect. Process innovation refers to new production methods or managing commodities commercially (Schumpeter, Citation1934), which results in competitive advantage, sustainability, and firm performance (Rowley et al., Citation2011).

Further, the service innovation results in this study revealed an insignificant effect on firm performance. Several studies explain that service innovation focuses on creating new value through service design (Gunday et al., Citation2011; Karabulut, Citation2015; Toivonen & Tuominen, Citation2009). Therefore, it tends to reflect a firm’s willingness and ability to satisfy customers through a dynamic combination of service elements. In fact, the findings of McDermott and Prajogo (Citation2012) state that the exploration and exploitation of service innovation must be more aligned than competing, and it must also be synergized to contribute to firm performance. Astuti et al. (Citation2020) have demonstrated that the adoption of innovation has a positive and significant effect on firm performance; they also emphasize how SMEs in Indonesia adapt to innovation, which can improve firm performance. Therefore, in this study, it is possible that open innovation activities are still not measurable enough to produce innovation output that can affect firm performance. This may depend on the knowledge management capability and innovation capability of a firm, allowing it to produce innovation output that affects firm performance.

5.2. Implications

This study has two objectives that make a theoretical and practical contribution to the discussion of SMEs. First, the findings provide evidence of a significant relationship between open innovation and different types of innovation (i.e., product, service, and process). The extent to which open innovation affects product, service, and process innovation; SMEs need to consider the knowledge flow to provide capabilities that lead to firm performance. Further, open innovation is a strong predictor of innovation adoption, particularly in the context of SMEs in developing countries, as highlighted in prior research (Mina et al., Citation2014; Prabowo et al., Citation2020; Tsinopoulos et al., Citation2017). The study has examined open innovation in SMEs as part of increasing capabilities that utilize the flow of knowledge (i.e., outbound and inbound) to improve firm performance through innovation adoption. The study demonstrates that open innovation, in influencing firm performance, does not directly have to go through a specific type of innovation. The findings also indicate that intangible assets are a resource that can be exploited by SMEs, and play a significant role in determining firm performance.

Second, this study also makes a practical contribution to open innovation for SMEs in Indonesia. The research will be useful for policy making in Indonesia for entities such as the Ministry for Cooperatives as well as SMEs, by assisting SMEs to increase capabilities by adopting innovation. In addition, this study highlights Indonesia’s innovation ecosystem based on an assessment of the Global Innovation Index (2019). The index shows that this ecosystem is still small. The study also provides an overview of open innovation in SMEs in Indonesia, thereby assisting policy makers to pay more attention to this aspect. For owners and managers of SMEs, it is important to explore and exploit knowledge as a resource to increase their ability to adopt innovation. In response to the ever-changing environment and intense competition, the findings of this study provide possible strategic steps to achieve competitive advantage and sustainable firm performance. However, when adopting innovation, it is also necessary to consider the cost of innovation activities to ensure that innovation output is effective and efficient.

6. Conclusion and limitation

This study considered open innovation, focusing on different types of innovation, and their mediating role. This was examined in relation to firm performance in the context of SMEs in Indonesia. The study results reveal that open innovation has a direct, positive, and significant effect on product, process and service innovation, although this effect is not significant for firm performance. This is consistent with the hypothesis of this study, which posits that open innovation does not directly and significantly affect firm performance. Second, this study reveals that of the different types of innovation––both direct and as a mediation of firm performance––only process innovation has a positive and significant effect. These findings emphasize that the type of innovation can affect firm performance, depending on the knowledge management capability and innovation capability of the firm. However, the findings of this study cannot be generalized regarding open innovation in SMEs and general assumptions should be avoided. This is because in other regions in Indonesia, or even in other developing countries, the results may be different. Finally, although open innovation has shown extraordinary results in Western countries, it should be highlighted that there are differences in innovation capability in non-Western contexts. In addition, future research in the context of open innovation will continue to be an interesting and relevant topic for business development. Therefore, regarding the findings of this study aimed at promoting open innovation within firms, key variables at the top management level, such as CEO servant leadership are identified as having the potential to influence the firm’s open innovation. Furthermore, leaders wield significant influence through mechanisms (e.g., behaviors, procedures, practices) that instill beliefs and values into employees’ “thinking, behavior, and emotions”, fostering creative (Ruiz-Palomino & Zoghbi-Manrique de Lara, Citation2020) and innovativeness (Ruiz-Palomino et al., Citation2021). Moreover, in fostering creativity and innovation among employees, CEO servant leadership can also cultivate an innovation culture within the organization, as evidenced by previous studies on the impact of CEO servant leadership (Ruiz-Palomino et al., Citation2021).Thus, future research could evaluate the implications of leadership factors in facilitating open innovation and enhancing firm performance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahn, J. M., Mortara, L., & Minshall, T. (2018). Dynamic capabilities and economic crises: Has openness enhanced a firm’s performance in an economic downturn? Industrial and Corporate Change, 27(1), 49–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtx048

- Alavi, M., & Leidner, D. E. (2001). Knowledge management and knowledge management systems: Conceptual foundations and research issues. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 25(1), 107–136. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250961

- Andres, R.-P., Enrico, C., & Terrence, B. (2017). Open innovation in specialized SMEs: The case of supercars. Business Process Management Journal, 23(6), 1167–1195. https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-10-2016-0211

- Astuti, E. S., Sanawiri, B., & Iqbal, M. (2020). Attributes of innovation, digital technology and their impact on SME performance in Indonesia. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 24(1), 1–14.

- Audretsch, B. D., & Belitski, M. (2023). The limits to open innovation and its impact on innovation performance. Technovation 119, 102519. Article 102519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2022.102519

- Avkiran, N. K. (2018). An in-depth discussion and illustration of partial least squares structural equation modeling in health care. Health Care Management Science, 21(3), 401–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10729-017-9393-7

- Banbury, C. M., & Mitchell, W. (1995). The effect of introducing important incremental innovations on market share and business survival. Strategic Management Journal, 16(S1), 161–182. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250160922

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Belderbos, R., Faems, D., Leten, B., & van Looy, B. (2009, January). Technological activities and their impact on the financial performance of the firm: Exploitation and exploration within and between firms faculty of business and economics technological activities and their impact on the financial performance of the firm. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1–34. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1537029

- Benner, M. J., & Tushman, M. L. (2003). Exploitation, exploration, and process management: The productivity dilemma revisited. Academy of Management Review, 28(2), 238–256. https://doi.org/10.2307/30040711

- Bianchi, M., Croce, A., Dell’era, C., DiBenedetto, C. A., & Frattini, F. (2016). Organizing for inbound open innovation: How external consultants and a dedicated R&D unit influence product innovation performance. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 33(4), 492–510. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12302

- Bravo, M. I. R., Montes, L., & Moreno, R. (2017). Open innovation and quality management: The moderating role of interorganisational IT infrastructure and complementary learning styles. Production Planning & Control, 28(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2017.1306895

- Brunswicker, S., & Vanhaverbeke, W. (2015). Open innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): External knowledge sourcing strategies and internal organizational facilitators. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(4), 1241–1263. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12120

- Buitelaar, W. (1988). Technology and work: Labour studies in England, Germany, and the Netherlands. Gower Publishing Company.

- Camerani, R., Corrocher, N., & Fontana, R. (2016). Drivers of diffusion of consumer products: Empirical evidence from the digital audio player market. Economics of Innovation & New Technology, 25(7), 731–745. https://doi.org/10.1080/10438599.2016.1142125

- Carroll, N., & Helfert, M. (2015). Service capabilities within open innovation—revisiting the applicability of capability maturity models. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 28(2), 275–303. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-10-2013-0078

- Chen, J., Chen, Y., & Vanhaverbeke, W. (2011). The influence of scope, depth, and orientation of external technology sources on the innovative performance of Chinese firms. Technovation, 31(8), 362–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2011.03.002

- Cheng, C. C. J., & Huizingh, E. K. R. E. (2014). When is open innovation beneficial? The role of strategic orientation. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 31(6), 1235–1253. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12148

- Chesbrough, H. W. (2003). Open innovation: The new imperative for creating and profiting from technology. Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315276670-9

- Chesbrough, H., & Bogers, M. (2014). Explicating open innovation: Clarifying an emerging paradigm for understanding innovation. In H. Chesbrough, W. Vanhaverbeke, & J. West (Eds.), New frontiers in open innovation (pp. 3–28). Oxford University Press.

- Chesbrough, H., & Crowther, A. K. (2006). Beyond high tech: Early adopters of open innovation in other industries. R&D Management, 36(3), 229–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.2006.00428.x

- Chibuzo, E. V., Onuoha, P. B. C., & Nwede, I. G. N. (2017). Globalization and performance of manufacturing in Port Harcourt. International Journal of Advanced Academic Research | Social & Management Sciences, 3(11), 1–27.

- Chiesa, V., Frattini, F., Lazzarotti, V., & Manzini, R. (2008). Designing a performance measurement system for the research activities: A reference framework and an empirical study. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 25(3), 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jengtecman.2008.07.002

- Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128–152. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393553

- Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). SAGE.

- Crook, T., Todd, S., Combs, J., Woehr, D., & Ketchen, D. (2011). Does human capital matter? A meta-analysis of the relationship between human capital and firm performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(3), 443–456. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022147

- Curado, C., Muñoz-Pascual, L., & Galende, J. (2018). Antecedents to innovation performance in SMEs: A mixed methods approach. Journal of Business Research, 89, 206–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.12.056

- Das, T. K., & Teng, B.-S. (1998). Between trust and control: Developing confidence in partner cooperation in alliances. The Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 491–512. https://doi.org/10.2307/259291

- Deloitte. (2017). A new future for R & D? Measuring the return from pharmaceutical innovation 2017 contents. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/life-sciences-health-care/deloitte-uk-measuring-roi-pharma.pdf

- De Marco, C. E., Martelli, I., & DiMinin, A. (2020). European SMEs’ engagement in open innovation when the important thing is to win and not just to participate, what should innovation policy do? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 152, 119843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.119843

- Den Hertog, P., van der Wietze, A., & de Jong, M. W. (2010). Capabilities for managing service innovation: Towards a conceptual framework. Journal of Service Management, 21(4), 490–514. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564231011066123

- De Zubielqui, G. C., Lindsay, N., Lindsay, W., & Jones, J. (2019). Knowledge quality, innovation and firm performance: A study of knowledge transfer in SMEs. Small Business Economics, 53(1), 145–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0046-0

- Distanont, A., Khongmalai, O., & Distanont, S. (2019). Innovations in a social enterprise in Thailand. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences, 40, 411–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kjss.2017.08.005

- Dost, M., Badir, Y. F., Ali, Z., & Tariq, A. (2016). The impact of intellectual capital on innovation generation and adoption. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 17(4), 675–695. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-04-2016-0047

- Fachrunnisa, O., Adhiatma, A., & Tjahjono, H. K. (2020). Cognitive collective engagement: Relating knowledge-based practices and innovation performance. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 11(2), 743–765. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-018-0572-7

- Ferdinand, J., & Meyer, U. (2017). The social dynamics of heterogeneous innovation ecosystems: Effects of openness on community–firm relations. International Journal of Engineering Business Management, 9, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1847979017721617

- Fisher, G. J., & Qualls, W. J. (2018). A framework of interfirm open innovation: Relationship and knowledge based perspectives. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 33(2), 240–250. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-11-2016-0276

- Flikkema, M. J. (2008). Service development and new service performance: A conceptual essay and a project-level study into the relationship between HRM practices and the performance of new services [ PhD thesis]. Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. VU Research Portal. https://research.vu.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/42178597/complete+dissertation.pdf

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Fu, L., Liu, Z., & Zhou, Z. (2019). Can open innovation improve firm performance? An investigation of financial information in the biopharmaceutical industry. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 31(7), 776–790. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2018.1554205

- Garriga, H., von Krogh, G., & Spaeth, S. (2013). How constraints and knowledge impact open innovation. Strategic Management Journal, 34(9), 1134–1144. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2049

- Gharakhani, D., & Mousakhani, M. (2012). Knowledge management capabilities and SMEs’ organizational performance. Journal of Chinese Entrepreneurship, 4(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1108/17561391211200920

- Godener, A., & Söderquist, K. E. (2004). Use and impact of performance measurement results in R&D and NPD: An exploratory study. R&D Management, 34(2), 191–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.2004.00333.x

- Gök, O., & Peker, S. (2017). Understanding the links among innovation performance, market performance and financial performance. Review of Managerial Science, 11(3), 605–631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-016-0198-8

- González-Blanco, J., Coca-Pérez, J. L., & Guisado-González, M. (2019). Relations between technological and non-technological innovations in the service sector. The Service Industries Journal, 39(2), 134–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2018.1474876

- Grant, R. M. (1996). Toward a knowledge‐based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17(S2), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250171110

- Greco, M., Grimaldi, M., & Cricelli, L. (2016). An analysis of the open innovation effect on firm performance. European Management Journal, 34(5), 501–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2016.02.008

- Guisado-González, M., Guisado-Tato, M., & Ferro-Soto, C. (2016). The interaction of technological innovation and increases in productive capacity: Multiplication of loaves and fishes? South African Journal of Business Management, 47(2), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajbm.v47i2.59

- Gunday, G., Ulusoy, G., Kilic, K., & Alpkan, L. (2011). Effects of innovation types on firm performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 133(2), 662–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2011.05.014

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis. Pearson. https://doi.org/10.1038/259433b0

- Hair, J., Hult, G., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Ham, J., Choi, B., & Lee, J.-N. (2017). Open and closed knowledge sourcing: Their effect on innovation performance in small and medium enterprises. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 117(6), 1166–1184. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-08-2016-0338

- Hameed, W. U., & Naveed, F. (2019). Coopetition-based open-innovation and innovation performance: Role of trust coopetition-based open-innovation and innovation performance: Role of trust and dependency evidence from Malaysian high-tech SMEs. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences, 13(1), 209–230. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/196194

- Hanaysha, J. R. (2020). Innovation capabilities and authentic leadership: Do they really matter to firm performance? Journal of Asia-Pacific Business, 21(4), 271–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/10599231.2020.1824523

- Hannigan, T. R., Seidel, V. P., & Yakis-Douglas, B. (2018). Product innovation rumors as forms of open innovation. Research Policy, 47(5), 953–964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.02.018

- Hao-Chen, H., Mei-Chi, L., Lee-Hsuan, L., & Chien-Tsai, C. (2013). Overcoming organizational inertia to strengthen business model innovation: An open innovation perspective. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 26(6), 977–1002. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-04-2012-0047

- Hao-Chen, H., Mei-Chi, L., & Wei-Wei, H. (2015). Resource complementarity, transformative capacity, and inbound open innovation. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 30(7), 842–854. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-09-2013-0191

- Heenkenda, H. M. J. C. B., Xu, F., Kulathunga, K. M. M. C. B., & Senevirathne, W. A. R. (2022). The role of innovation capability in enhancing sustainability in SMEs: An emerging economy perspective. Sustainability, 14(17), 10832. Article 10832. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710832

- Henfridsson, O., Mathiassen, L., & Svahn, F. (2014). Managing technological change in the digital age: The role of architectural frames. Journal of Information Technology, 29(1), 27–43. https://doi.org/10.1057/jit.2013.30

- Hernandez-Vivanco, A., Cruz-Cázares, C., & Bernardo, M. (2018). Openness and management systems integration: Pursuing innovation benefits. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 49, 76–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jengtecman.2018.07.001

- Hervas-Oliver, J. L., Sempere-Ripoll, F., & Boronat-Moll, C. (2014). Process innovation strategy in SMEs, organizational innovation and performance: A misleading debate?. Small Business Economics, 43, 873–886. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9567-3

- Hervas-Oliver, J. L., Sempere-Ripoll, F., & Boronat-Moll, C. (2021). Technological innovation typologies and open innovation in SMEs: Beyond internal and external sources of knowledge. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 162, 120338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120338

- Ho, L. (2008). What affects organizational performance? The linking of learning and knowledge management. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 108(9), 1234–1254. https://doi.org/10.1108/02635570810914919

- Horvat, A., Behdani, B., Fogliano, V., & Luning, P. A. (2019). A systems approach to dynamic performance assessment in new food product development. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 91, 330–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2019.07.036

- Huang, F., & Rice, J. (2012). Openness in product and process innovation. International Journal of Innovation Management, 16(4), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1363919612003812

- Huber, G. P., & Power, D. J. (1985). Retrospective reports of strategic‐level managers: Guidelines for increasing their accuracy. Strategic Management Journal, 6(2), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250060206

- Hughes, M., Hughes, P., Hodgkinson, I., Chang, Y. Y., & Chang, C. Y. (2022). Knowledge‐based theory, entrepreneurial orientation, stakeholder engagement, and firm performance. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 16(3), 633–665. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1409

- Huizingh, E. K. R. E. (2011). Open innovation: State of the art and future perspectives. Technovation, 31(1), 2–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2010.10.002

- Hung, K.-P., & Chiang, Y.-H. (2010). Open innovation proclivity, entrepreneurial orientation, and perceived firm performance. International Journal of Technology Management, 52(3/4), 257–274. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.2010.035976

- Hung, K.-P., & Chou, C. (2013). The impact of open innovation on firm performance: The moderating effects of internal R&D and environmental turbulence. Technovation, 33(10–11), 368–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2013.06.006

- Hwang, J., & Lee, Y. (2010). External knowledge search, innovative performance and productivity in the Korean ICT sector. Telecommunications Policy, 34(10), 562–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2010.04.004

- Ibrahim, M., & Yusheng, K. (2020). Service innovation and organisational performance: Mediating role of customer satisfaction. International Journal of Management & Entrepreneurship Research, 2(3), 97–108. https://doi.org/10.51594/ijmer.v2i3.142

- Inauen, M., & Schenker‐Wicki, A. (2012). Fostering radical innovations with open innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 15(2), 212–231. https://doi.org/10.1108/14601061211220986

- Iqbal, M., Mawardi, M. K., Sanawiri, B., Alfisyahr, R., & Syarifah, I. (2023). Strategic orientation and its role in linking human capital with the performance of small and medium enterprises in Indonesia. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, 25(1). Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRME-11-2021-0150.

- Kapetaniou, C., & Lee, S. H. (2019). Geographical proximity and open innovation of SMEs in Cyprus. Small Business Economics, 52(1), 261–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0023-7

- Karabulut, A. T. (2015). Effects of innovation strategy on firm performance: A study conducted on manufacturing firms in Turkey. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 195, 1338–1347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.06.314

- Kilay, A. L., Simamora, B. H., & Putra, D. P. (2022). The influence of e-payment and e-commerce services on supply chain performance: Implications of open innovation and solutions for the digitalization of micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in Indonesia. Journal of Open Innovation, 8(3), 119. Article 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8030119

- Kim, H., & Kim, E. (2018). How an open innovation strategy for commercialization affects the firm performance of Korean healthcare IT SMEs. Sustainability, 10(7), 2476. Article 2476. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072476

- Koellinger, P. (2008). The relationship between technology, innovation, and firm performance: Empirical evidence from e-business in Europe. Research Policy, 37(8), 1317–1328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2008.04.024

- Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Organization Science, 3(3), 383–397. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.3.3.383

- Koloniari, M., Vraimaki, E., & Fassoulis, K. (2018). Fostering innovation in academic libraries through knowledge creation. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 44(6), 793–804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2018.09.016

- Kotler, P., Kartajaya, H., & Setiawan, I. (2019). Marketing 3.0: From products to customers to the human spirit. In K. Kompella (Ed.), Marketing wisdom (pp. 139–156). Springer Singapore.

- Kunttu, A., & Torkkeli, L. (2015). Service innovation and internationalization in SMEs: Implications for growth and performance. Management Revue, 26(2), 83–100. https://doi.org/10.5771/0935-9915-2015-2-83

- Kuo, C. M., Chen, L. C., & Tseng, C. Y. (2017). Investigating an innovative service with hospitality robots. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(5), 1305–1321. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-08-2015-0414

- Latifah, L., Setiawan, D., Aryani, Y. A., Sadalia, I., & Al Arif, M. N. R. (2022). Human capital and open innovation: Do social media networking and knowledge sharing matter? Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 8(3), 116. Article 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8030116

- Laursen, K., & Salter, A. (2006). Open for innovation: The role of openness in explaining innovation performance among U.K. manufacturing firms. Strategic Management Journal, 27(2), 131–150. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.507

- Law Number 20. (2008). Micro small and medium enterprises

- Lichtenthaler, U. (2009). Outbound open innovation and its effect on firm performance: Examining environmental influences. R&D Management, 39(4), 317–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.2009.00561.x

- Luo, X., Griffith, D. A., Liu, S. S., & Shi, Y.-Z. (2004). The effects of customer relationships and social capital on firm performance: A Chinese business illustration. Journal of International Marketing, 12(4), 25–45. https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.12.4.25.53216

- Maes, J., & Sels, L. (2014). SMEs’ radical product innovation: The role of internally and externally oriented knowledge capabilities. Journal of Small Business Management, 52(1), 141–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12037

- Makri, K., Theodosiou, M., & Katsikea, E. (2017). An empirical investigation of the antecedents and performance outcomes of export innovativeness. International Business Review, 26(4), 628–639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2016.12.004

- Mamun, A. A. (2018). Diffusion of innovation among Malaysian manufacturing SMEs. European Journal of Innovation Management, 21(1), 113–141. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-02-2017-0017

- Mauro, C., Emilia, L., Antonello, C., & Francesca, M. (2016). Exploring the impact of open innovation on firm performances. Management Decision, 54(7), 1788–1812. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-02-2015-0052

- McDermott, C. M., & Prajogo, D. I. (2012). Service innovation and performance in SMEs. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 32(2), 216–237. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443571211208632

- Miles, I., Belousova, V., & Chichkanov, N. (2017). Innovation configurations in knowledge-intensive business services. Foresight and STI Governance, 11(3), 94–102. https://doi.org/10.17323/2500-2597.2017.3.94.102

- Mina, A., Bascavusoglu-Moreau, E., & Hughes, A. (2014). Open service innovation and the firm’s search for external knowledge. Research Policy, 43(5), 853–866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.07.004

- Mokter, H., & Ilkka, K. (2016). Open innovation in SMEs: A systematic literature review. Journal of Strategy and Management, 9(1), 58–73. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSMA-08-2014-0072