Abstract

Purchasing and shopping habits have been disrupted due to the COVID-19 pandemic mainly because of the lockdown imposed in the society and social distancing due to which new habits are being developed among consumers. New regulations and procedures will likely affect the way consumers purchase products and avail services, even if consumers return to their old habits. Digital Marketing, Technological Advancement, Changing Demographics, and consumers’ innovative ways of coping with the blurring of work, leisure, and education boundaries as all of these will contribute to the emergence of new habits. A conceptual framework is developed and tested as a result, which reveals the impact of marketing mix adjustments and lifestyle adjustments of consumers upon their habits as well as purchasing behavior during COVID-19. The moderating role of gender and generational age has been employed in this study to get a deeper understanding of the changing buying behavior of consumers during this pandemic. Data has been collected online due to restrictions imposed and the results depicted the significant impact of marketing mix adjustments as well as lifestyle adjustments on the habits and purchase behavior. As for moderating effect gender had no effect except for place and delivery adjustments and generational age had a moderating effect on all but promotional adjustments during COVID-19. Government policy-makers and retail managers should take note of these findings. Studying the consequences of a crisis over time or comparing the effects of multiple crises can help us better understand consumers’ adjustment behavior during a crisis such as the one that has currently been faced. During COVID-19, comparative research between developed and developing countries can be undertaken to compare changing buying behavior and habits among customers of different nature.

1. Introduction

The major economic challenge of 2020 is, without the shadow of a doubt the pandemic COVID-19 that has infected millions all over the globe, representing a much more advancing pandemic than the recent territorial pandemics (Development, Citation2020). There are many ways to see the impact of the pandemic, from the lockdown of cities to retail and leisure restrictions, labor restrictions to restricted travel to the most important: a decline in economic activity that results in a decline in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Coccia, Citation2022). Pakistan’s economy has long been in tumult ever since 2016 and the stock exchange of Pakistan crashed terribly due to COVID-19 and lockdown in major cities which further became a serious peril (Sharif, Citation2020). The economy of Pakistan had already been facing high taxation, high-interest rates, import restrictions being imposed with vigor, as well as a major devaluation of the Pakistani Rupee resulting in increased prices of imports that has been terribly been leading to a huge decline in industrial production (Rana et al., Citation2020). The retail industry was already in a state of disruption since a long time, but an unforeseen pandemic of this degree created a vigorous change in the buying behavior of consumers (Akers, Citation2020). This grim scenario did not improve until April 2021, when the country’s effective vaccines became widely available. Even after that, a huge percentage of people failed to heed health advice and get vaccinated (Kitayama et al., Citation2022).

A plethora of new research opportunities have been created as a result of the global lockout and social estrangement, which have an impact on the full spectrum of consumer behavior (from problem awareness to search to information to purchase to delivery to consumption and waste disposal). The buying decision is a topic that hasn’t been studied very much when people are in crises. This may be seen by looking at the paucity of empirical research on consumer behavior in economic crises and the scant amount of literature on how these crises affect consumers’ purchasing intentions (Kaytaz & Gul, Citation2014). It should be noted that research on behaviour in the setting of pandemics is still in its infancy (Ahmed & Ansari, Citation2023). Consumer’s daily lives were affected by COVID-19 from unemployment and recession regarding the spending habits of consumers, mobility, and prosperity (Koos et al., Citation2017). Habits of consumers are their response towards behavioral cues that are developed when consumers experience the same activity again and again (Hagger, Citation2019). This study investigates how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted consumer behavior. Because of the lockdown and social isolation brought on by the worldwide crises, will consumers’ consumption patterns change for good, or will they go back to their previous patterns after the crisis has passed?

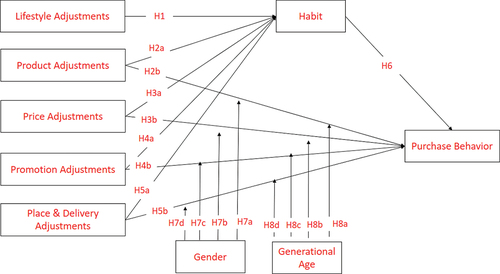

The objective of the study is to find changing consumer behavior and habits and how the consumers did lifestyle adjustments and marketing mix adjustments during COVID-19. Specific objectives of this study includes to identify the effect of Lifestyle Adjustments, Product Adjustments, Price Adjustments, Promotion Adjustments, and Deliver & Place Adjustments on Consumers’ Habit that further lead to influence their Purchase Behavior. Further, specific objectives of the study includes to identify the moderating effect of consumers’ ‘demographics like generational age and gender that were used to further segment the consumers in times of crisis.

Gender is a social construct that influences almost every aspect of human behavior, hence, having a strong association with 4Ps of marketing, i.e. Product, Price, Place, and Promotion. Women’s social roles are becoming more like those of men. Because of the changing roles of men and women in the workplace and at home, there is a greater need to investigate the gender effects during COVID-19. To summarize, gender is important in marketing and retailing because it influences consumer behavior, persuasion effects, and purchasing decisions. Less is known about how social norms differ between men and women, and how this difference affects consumption during the pandemic. Generational differences are determined not by an individual’s age, but rather by the shared influences and experiences of a particular generation (Jones et al., Citation2018). Thus, groups of people born during the same time period and growing up in the same environment will have similar values, attitudes, beliefs, and expectations that remain constant throughout the generation’s lifetime and constitute a generational identity (Schewe & Meredith, Citation2004). This study aims to see how consumption adjustments, and buying behavior affect fashion apparel, and has two goals: first, it investigates the relationship between consumer lifestyle adjustments and habit and purchase behavior during COVID-19. Secondly, it examines the effect of categorical moderators, such as gender and generational age, on marketing mix adjustments and purchase behavior. With the help of moderating variables, a strategy should be developed to help retailers adjust to the changing consumer behavior and therefore increasing their market share and thus profitability.

Another important factor was identified during the literature review, i.e. consumer’s Lifestyle. During COVID-19 pandemic, panic buying issue had at times emerged all over the world and a significant change in household consumption pattern has been identified. During the lockdowns, panic buying got started that led to the changes in consumption patterns (Prentice et al., Citation2020). During COVID −19, lifestyle of the people has been noticed to be totally changed due to restrictions; shopping patterns have changed from conventional buying to virtual/e-commerce (Biilore & Annisimova, Citation2020). In Pakistan E-commerce started in 2000 with only 3% of the population purchasing products online (Bhatti, Citation2018). But during the COVID-19 pandemic the e-commerce in Pakistan soared by 10%, creating an ever-increasing e-commerce trend in Pakistan (Niazi, Citation2020). Also, 52% of consumers were reluctant to visit stores and avoided congested areas (Bhatti et al., Citation2020). Consumers who were cautious to buy products online started buying and encountering a completely new customer journey which might as well continue this behavior. The global lockdown has undoubtedly expedited this online shopping behavior and thus the rapid growth of e-commerce. Considering that this pandemic is a global change for economies all over the world facing a devastating recession, studying consumer behavior under crisis provides important intuition both for marketing academia and economists. Unlike this COVID-19 comparison with other global crises, like the 2008 financial crisis, is not at all possible.

Clothing, shoes, make-up accessories, jewelry, games, and electronics can be counted among the items on which people are spending less of their income (Mehta et al., Citation2020). Most of the closures were caused by fashion retailers during the peak season, which coincided with COVID-19’s sudden lockdown. In terms of sales income, billions were lost, and cash flow issues were compounded as the money of retailers was tied up in unfinished or ongoing ventures (Ali, Citation2020). Due to COVID-19 epidemic the consumer online purchasing or selling habits have been developed (McKinsey, Citation2020) and caused a massive economic impact on consumers (Pak et al., Citation2020), the apparel industry did not adjust to the changing marketing mix (4Ps) resulting in decreased sales and profitability (Hassan, Citation2020). The Kantar report found that strong brands recovered nine times faster from the 2008 financial crisis than weak ones and so the marketers may need to adapt their marketing during the COVID-19 pandemic (Holman, Citation2020).

This study examines how the COVID-19 worldwide pandemic of 2020 may affect customer characteristics, purchasing habits, psychographic behaviors, and other marketing endeavors. The changes in long-term behavioral during COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the changes in consumer behavior that would follow, are then suggested to marketers using these potential implications to develop a conceptual framework. This study can define the target age group of consumers by their purchase behavior during a crisis and will help marketers plan and be prepared for future crises. While generational cohorts concentrate on cataclysmic events that cause a shift in the social value system, generations place more emphasis on the year of birth. These catastrophic occurrences bring about a change in society and provide individuals growing up at the time a new set of ideals (Zwanka & Buff, Citation2021).

The first theory to propose a connection between the environment and behavior was the stimulus-response theory (S-O-R). The S-O-R has dominated the literature on customer behavior and is often used in marketing research (Donovan, Citation1994). The S-O-R model is a very good fit for this study because this model has been commonly used in online user behavior research as well as its simplicity compared to the other theories of consumer behavior (Mehrabian & Russell, Citation1974).

Triandis (Citation1977) developed the Theory of International Behavior (TIB). The three dimensions of behavior are intention, facilitating conditions, and habit. As Triandis (Citation1977) suggests, the habit can have an impact on the emotive component of attitude (affect) (Gagnon et al., Citation2003; Triandis, Citation1977). The Triandi’s model was also chosen because it comprises a more comprehensive model of behavior that considers previous behavior that is habit. Habit as a construct has not been used widely in the study of consumer behavior (Azeema et al., Citation2016) and would add to our knowledge of consumer consumption adjustments in times of COVID-19.

Consumption adjustments refer to the adjustments made by the customers in their consumption patterns, such as changes in household welfare and healthcare consumption (Bayraktaroğlu & AliMen, Citation2011). Several consumer adjustments have been classified under five categories, such as General, Price, Product, Place, and Promotion adjustments. Ang et al. (Citation2000) specifies the five categories of consumption adjustments as general, promotion, product, price, and shopping adjustments as already mentioned above. These adjustments are made by Asian consumers as they are price bargainers as they spend less on shopping during crisis, and evaluate promotional campaigns on rational grounds.

1.1. Hypotheses development

1.1.1. Lifestyle adjustments

The COVID-19 pandemic, has so far been the most dominant global issue influencing people’s lifestyle patterns since 2020 (Scapaticci et al., Citation2022). Social measures like as quarantine and lockdown, fear of COVID-19 sickness, and lifestyle changes have also had significant effects on mental health as a result of the pandemic (Molarius & Persson, Citation2022). Asian consumers have been considered as less wasteful following a very simple lifestyle (Ang et al., Citation2000). Household consumption patterns are adjusted when an individual leaves his parents’ house and get into another house. The adjustment decisions occur when individuals marry, have children, divorce, retire, or make decisions for other lifestyle related changes (Megbolugbe et al., Citation1991). The individual’s living conditions and lifestyle habits, without the shadow of a doubt, have a significant impact on mental health (Lund et al., Citation2018). Shifts in wellness tactics, health management, routine, stressors, and time perception have all been reported as lifestyle changes (Sinko et al., Citation2022). Based on the above mentioned discussion, the following hypotheses are developed:

H1:

There is a significant impact of the consumer’s Lifestyle Adjustments on consumer’s Habits during COVID-19.

1.1.2. Product adjustments

A product is a tangible, physical, or service that could be provided. However, the term has been expanded to include services provided by a service organization (Ling, Citation2007). Product refers to aspects such as its product portfolio, the brand newness, and differentiation between these products and competitors, or their superiority over rivals’ quality products (Limayem et al., Citation2007). It has been noticed that a company’s product should always be evaluated in light of the needs of its customers for obvious reasons (Meldrum & McDonald, Citation2007). Consumers find product appears to be one of the most important differentiators. An effective marketing strategy can be considered to be the design and delivery of a product or service that fully responds to the clients’ needs and wishes or demands (Saif & Aimin, Citation2014). Considering that habits of people seem to buy the same brands of products repeatedly, buy the same quantities in each retail store, and consume similar types of foods throughout a meal. It is known that habits play an extremely crucial role in determining the actions (Werner, Citation1991). Previous research has demonstrated that during a financial crisis, customers cut down on their wasteful expenditure and migrate to less expensive, more local products. In the times of recessions it is absolutely not a good time to introduce new brands; nevertheless, strong businesses have the opportunity to plug gaps in existing product lines to block future competitors (Ang, Citation2001). A company’s ability to adapt and switch into pandemic-related product production reflect its flexibility, innovation, and ability to exploit opportunities (Wang et al., Citation2020). Previous studies have linked marketing mix to consumer behavior, therefore, considering the abovementioned literature, the following hypotheses are developed:

H2a:

There is a significant impact of the Product Adjustments on consumer’s Habit during COVID-19.

H2b:

There is a significant impact of the Product Adjustments on consumer’s Purchase Behavior during COVID-19.

1.1.3. Price adjustments

COVID-19 pandemic had a tremendous impact on the income and time restrictions, also on pricing and a drop in demand for some niche and premium food products as people shifted to value-priced and alternatives in light of expected income decreases (Cranfield, Citation2020). Price is the only marketing mix element that generates revenue. Because of this reason, it is important to consider profit margins while making pricing decisions. For example, low prices may not generate enough profit for the organizations (Altay et al., Citation2021) [3]. As the amount of money required for a product is concerned, it depends solely on the consumer’s means, excessive prices can drive consumers away (Kotler & Keller, Citation2012). Pricing is an important marketing element with enormous business potential. It can undoubtedly lead a business to its knees if it is not managed properly (Meldrum & McDonald, Citation2007). Bundling items and services with promotions and discounts is another option for setting prices. In addition, it is also possible to offer customers extra free goods that are quite inexpensive to produce, which makes the company’s prices seem significantly less expensive. It must be willing to adjust rates if necessary to remain competitive, thrive, and perform well in a market that is undergoing rapid changes [39]. The primary determining factor is price, which must be determined based on the target market, product mix, and services being provided, as well as competition being faced by an organization (Prabowo & Sriwidadi, Citation2019). Based on the above mentioned literature review, the following hypotheses are developed:

H3a:

There is a significant impact of the Price Adjustments on consumer’s Habit during COVID-19.

H3b:

There is a significant impact of the Price Adjustments on consumer’s Purchase Behavior during COVID-19.

1.1.4. Promotion adjustments

The primary tactics for promoting goods and services in the digital environment have been taken into account by assessing the financial indicators during this particular pandemic, The financial results of the company have been used to evaluate the effectiveness of the promotion plan (Meshko & Savinova, Citation2020). The epidemic has had a tremendous impact on the marketing techniques of every organization. To begin with, many of the company’s present and potential clients were forced to cease operations. Furthermore, due to financial difficulties, most company executives lowered their budgets for promoting products (Meshko & Savinova, Citation2020). During a crisis, the number of businesses decreases, resulting in less market rivalry and a greater chance for businesses’ promotional messages to be recognized by consumers (Quelch & Jocz, Citation2009). Prior to the quarantine, about 45 percent of advertising campaigns were aimed at a foreign audience; after the quarantine, about 85 percent of advertising campaigns were aimed at the domestic market (Hirachigadzhieva, Citation2020). During and after a huge recession, those who increase or maintain their advertising spend see an increase in sales, income, and market share (Webb et al., Citation2022). Advertising is an investment, not a cost. When the economy improves, advertising’s rewards become apparent. Advertising budget cuts during a recession hurt firms’ performance more than maintaining or increasing their promotional efforts (Rosberg, Citation1979). Based on the literature review, the following hypotheses are developed:

H4a:

There is a significant impact of the Promotion Adjustments on consumer’s Habit during COVID-19.

H4b:

There is a significant impact of the Promotion Adjustments factor on consumer’s Purchase Behavior during COVID-19.

1.1.5. Place and delivery adjustments

The reach of the location or the place must be carefully evaluated; strategic locations provide better prospects for public access, but the cost of the location must also be considered because of easy access to consumers (Sinko et al., Citation2022; Syam et al., Citation2019). Specifically, at the time of crisis importance of place is usually increased to keep the valuables at a safe place (Ang et al., Citation2000). Consumers adjustment patterns can be forecasted considering the extrinsic factors, such as in-store product placement, in-store promotions, catalog positioning, and environmental conditions (Bashir et al., Citation2020). Product placement is linked to delivery networks. The COVID-19 epidemic prompted quarantines to a great number and lockdowns, making online shopping even more difficult. Regrettably, online purchasing has put a strain on the delivery infrastructure. The free shipping choices pushed delivery companies to cut costs even more. Customers seemed more willing to pay extra rates for greater shipping services (Grabara, Citation2021). Based on the above discussion, the following hypotheses are developed:

H5a:

There is a significant impact of the Place and Delivery Adjustments on consumer’s Habit during COVID-19.

H5b:

There is a significant impact of the Place and Delivery Adjustments on consumer’s Purchase Behavior during COVID-19.

1.1.6. Purchase behavior and habit

During the COVID-19 pandemic, political considerations such as during the lockdown and rigorous application of limiting people who are able to go out had an impact on purchasing behavior (Molarius & Persson, Citation2022) Purchase decisions are characterized as a stage in which customers are faced with the decision regarding whether a purchase should be made or not, as measured by indicators of the product stability, the habit of purchasing the product, giving recommendations to others, and making purchases repeatedly (Kotler & Keller, Citation2012). Changes in buying behavior rely on habit forming-a longer-term endeavor (Chan, Citation2020).Once a behavior has become a habit, or has been repeated, it becomes automatic and is performed without conscious thought. Habit, rather than attitude or social norms, has a greater impact on behavioral intentions, according to the researchers. The force of habit also determines several behavioral intentions when people acquire knowledge (Wood & Neal, Citation2009). For consumer behavior, research on habits is important since everyday life is characterized by repetition. Repeated transactions and loyalty are also influenced by habits. Habits become permanent patterns over time. Habit, rather than attitude or social norms, is known to have a greater impact on the behavioral intentions. Habits are formed over long-term repetition and results in purchase behavior so for retailers both these constructs are important that is why they are undertaken as dependent variables. Based on the above discussion, the following hypotheses are developed:

H6:

There is a significant impact of consumer’s Habits on their Purchase Behavior during COVID-19.

1.1.7. Gender

Gender identification refers to the recognition of masculine and feminine behaviors between a male and a female. Both men and women are different from each other because of their roles, preferences, and obligations in the society due to which they both react differently towards any stimulus (Fischer & Arnold, Citation1994). Considering the difference between gender related preferences marketers can take advantage and design proper strategy for their apparel brands (Peter et al., Citation1999). Both men and women have different consumption habits for which they make adjustments accordingly (Carpenter et al., Citation2005). Literature suggests that women spent more time in shopping of the products (Darley & Smith, Citation1995), whereas, men shop for specific items and do not spend a lot of time in shopping (Fischer & Arnold, Citation1994). Also, both men and women have different views about shopping, that creates difficulty for the marketers (Dittmar & Drury, Citation2000). Women spend multitude of time in seeking for knowledge about the product and they take interest in the process (Herter et al., Citation2014). Advertising displays of goods, atmosphere, promotions, and sales all have an impact on female consumers’ purchasing intentions (Xuanxiaoqing, Citation2012). Based on this discussion, the following hypotheses is developed in this study:

H7a:

There is a moderating effect Gender between Product Adjustments between consumer’s Purchase Behavior during COVID-19.

H7b:

There is a moderating effect Gender between Price Adjustments between consumer’s Purchase Behavior during COVID-19.

H7c:

There is a moderating effect Gender between Promotion Adjustments between consumer’s Purchase Behavior during COVID-19.

H7d:

There is a moderating effect Gender between Place and Delivery Adjustments between consumer’s Purchase Behavior during COVID-19.

1.1.8. Generational age

Human beings have been categorized into generations, such as Baby Boomers (1945–1964) Gen X (1965–1982), Millennials (1983–2000), and Gen Z(2000 and above). Millennials and Gen Z are the two generations who have seen the techno-logical advancements in this world (Nguyen, Citation2020). The low income and insecurity is the reason why Gen Z delay the purchase transactions (Azmy, Citation2020). Millennials can easily convince their parents to buy the things and they have different purchasing habits. That is the reason marketers often design campaigns for Millennials because there are a lot of potential customers present in this generation. A large spending has been noticed by Millennials on clothes (Taylor & Cosenza, Citation2002). Women belongs to Millennials focuses on style not quality specifically when buying clothes (Bakewell & Mitchell, Citation2006). This generation can prioritize the relationships over materialistic approach specifically in the post-pandemic scenario (Bakhtairi, Citation2020). They want products that are a good fit for their personality and lifestyle. Gen Y’s brand loyalty is erratic, shifting swiftly with fashion, trend, and brand popularity and emphasizing style and quality over price (Reisenwitz & Iyer, Citation2009). Generation X is more proficient and at ease with computer-mediated communication. However, they tend to ignore targeted advertising and reject any form of segmentation and marketing technique (Lissitsa & Kol, Citation2016). This generation is price conscious but not price sensitive (Williams et al., Citation2011). Based on the consumption habits and consumption adjustments made generational age group, the following hypotheses were developed in this study that are depicted in Figure as well:

H8a:

There is a moderating effect Generational Age between Product Adjustments between consumer’s Purchase Behavior during COVID-19.

H8b:

There is a moderating effect Generational Age between Price Adjustments between consumer’s Purchase Behavior during COVID-19.

H8c:

There is a moderating effect Generational Age between Promotion Adjustments between consumer’s Purchase Behavior during COVID-19.

H8d:

There is a moderating effect Generational Age between Place and Delivery Adjustments between consumer’s Purchase Behavior during COVID-19.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data collection

Primary data has been collected using a questionnaire which had been circulated online through online Google Forms platform due to the pandemic and social distancing. Population selected for this study was chosen to be the people of Pakistan who have currently been using fashion apparel brands. Data was particularly collected from the metropolitan cities of Pakistan using the convenience sampling technique. Considering the sample size, 329 responses were retained after removing the invalid/missing data that justifies the minimum criteria of subject-to-variable ratio that suggests 30 responses per variable. Likert scale of five points, with 1 being the least amount of agreement and 5 being the most amount of agreement. To measure the research constructs, 33 items were used. The constructs were adopted from the previous studies with the established reliabilities (i.e. alpha > 0.7). These constructs are Lifestyle Adjust-mint and Price Adjustment (Ang, Citation2000), Product Adjustment, Promotion Adjustments (Bayraktaroğlu & AliMen, Citation2011), Place adjustments (Bidyut Jyoti, Citation2020; Shama, Citation1978). Purchase behavior and Habits (Venkatesh et al., Citation2012). Complete questionnaire is provided in the Appendix. Moderating variable of Generational Age was measured by {1 = Gen Z (18–23); 2 = Gen Y/Millennials (24–39); 3 = Gen (40–54); 4 = Baby Boomers (55–64). Another moderating variable of Gender was measured by (1 = Male, 2 = Female). The demographic profile of the respondents is depicted in Table .

Table 1. Demographic profile

2.2. Data analysis

A structural equation modeling (SEM) approach was followed first to assess reliability, and validity. Secondly, the structural model was evaluated by testing the hypotheses by performing regression and moderation analysis through MGA was done using Smart PLS 3.33.

3. Results

The reliability was established as shown in Table . The AVE of all latent variables was above 0.5 which establishes the convergent validity of the model.

Table 2. Reliability and validity

The correlation between two latent variables can be estimated using this new method. For HTMT, a 0.90 threshold value has been proposed discriminant validity is present when the value is greater than 0.90 (Henseler et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, the HTMT’s confidence interval should not include a value of 1. The HTMT condition was met for this study, so discriminant validity is established (See Table ).

Table 3. Discriminant validity (HTMT)

Before making any conclusions, the structural model must be adequately analyzed in addition to the measurement model. In the structural model, collinearity is a potential concern, and a value of 5 or above on the variance inflation factor (VIF) often indicates such a problem (Hair et al., Citation2012, Citation2017). Table summarizes the results of the collinearity examination which shows the absence of collinearity between the predictor variables is indicated by the fact that all VIF values are less than 5.

Table 4. Significance testing results of the structural model Path Coefficients

Table depicts that all the hypotheses (i.e. H1, H2a, H2b, H3a, H3b, H4a, H4b, H5a, H5b, and H6) are supported in this study because there identified a significant effect of the variables on dependent variables.

When a model’s Q2 value is greater than zero it shows excellent predictive relevance (Chin, Citation1998). This model has excellent predictive relevance as shown in Table . The five constructs appear to be able to explain 69% of the variation in purchase intention and 48% of the variation in habit. Both the R2 values are significant and moderate respectively. The next step was to look at the moderating effects of the two demographic variables: age and gender. Multiple-group analysis (MGA) was recommended as both moderators in this study were categorical. Table depicts the results of Multi-Group Analysis.

Table 5. Results of coefficient of determination (R2) and predictive relevance (Q2)

Table 6. Results of hypotheses testing and differences among Male and female samples

There was a significant difference between male and females when Path analyses were done separately for both gender samples but after conducting Henseler’s MGA there were no moderating effect of product adjustments, price adjustments, and promotion adjustments on purchase behavior thereby not supporting H7a, H7b, and H7c respectively. For place and delivery adjustments, there was a moderating effect for place and delivery adjustments towards purchase behavior between males and females during COVID-19 and therefore H7d was supported. Both the genders had no significant difference on marketing mix except Place and delivery as during pandemic and imposed lockdown was being practiced, both the genders were focusing on the necessities due to the unknown time period of COVID-19, were price conscious and product durability as well consideration for local products as compared to imported ones.

Between the Millennials and Gen X samples, Henseler’s MGA revealed significant differences in the effect of product adjustments, price adjustments, and place and delivery adjustments on purchase behavior thereby supporting H8a, H8b, and H8d respectively (See Table ). For promotion adjustments, there was no moderating effect for promotion adjustments towards purchase behavior between Millennials and Gen X during COVID-19 and therefore H8c was not supported. Consumers compensate for product, promotion, distribution, and price judgments by relying more on product features, prices, and convenient retail locations and less on advertising imagery. This means that during COVID-19 both the Millennials and Gen X were not affected by promotional activities, and the retailers should focus more of price reduction. Although Gen X do not consider advertising claims, but Millennials also were not affected by promotional activities during COVID-19. We can say that during crisis consumers want price reductions and for them the placement of the product was most important. Due to COVID-19 unprecedented nature online purchase behavior was on rise but according to this study the response for online and offline shopping behavior was half and half considering the product was fashion clothing.

Table 7. Results of hypotheses testing and differences among Millennials and Gen X Samples

4. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic aftershocks can be felt for years to come but unfortunately, this pandemic is here to stay for some time and might become the normal for consumers as well as retailers. Lifestyle adjustments of the consumers during COVID-19 has had a significant impact on the habits which supports the previous study conducted by Ang (Citation2000), where 67.3 % of respondents said their consumption habits and tastes have altered as a result of the Asian crisis as well as almost 66% indicated they need to put in more effort to preserve their current lifestyle and 42% are frustrated because of crisis (Ang, Citation2001). Habits have a significant impact on purchase behavior and the relationship was supported in this study. The findings are aligned with the previous finding (Yilmaz et al., Citation2020) where they found that as respondents consumptions and purchasing have been altered due to COVID-19. AlTarrah et al. (Citation2021) in their study also observed the effect of COVID-19 on consumer food purchasing and eating behavior and observed a significant changes in the purchasing and eating phenomenon. According to Ellison et al. (Citation2021), a change in shopping behavior was observed as the pandemic evolved.

When a multitude of consumers are specialists who know what they’re buying it turns out to be accurate and entirely acceptable. In this scenario, pricing disparities can be trusted to reflect quality differences as determined by very qualified experts. A commodity sold at a lower price than rival commodities will be more appealing to the consumer due to its lower cost and less appealing due to its suspected inferior quality (Scitovszky, Citation1944). Therefore, price adjustments is known to have a negative impact on the habits during COVID-19 and is supported in this study as consumers are more careful with their apparel shopping it might not seem important as compared to everyday essential items with the lockdown imposed and uncertainty during COVID-19. Similarly, during economic downturns, general apparel spending falls. This implies not only a higher level of interest in pricing but also a higher level of value. Fashionable apparel is an example of conspicuous consumerism, and research shows that some customers reduce their consumption during recessions. The pandemic has created lifestyle adjustments with less involvement in social events and more time spent at home with family and friends (Zurawicki & Braidot, Citation2005). Product adjustments had a significant impact on habit during COVID-19 as consumers focus more on durability and on purchasing necessities rather than luxuries which are supported (Ang, Citation2001). Promotion adjustments had a significant impact on habit as well as consumers wanted more information regarding the apparel’s durability and longevity rather than the imagery that is shown in advertisements. Place and delivery adjustments had a significant impact on habit because of lockdown imposed by the government in sporadic intervals mostly delivery and became more of a habit and convenience for consumers (Limayem et al., Citation2007).

5. Conclusions

While demand for services that require face-to-face interaction, such as dining out and entertainment, dropped dramatically, online consumption of products and services, such as shopping, increased dramatically. Customers migrate to lower-cost brands which assure customers of good quality at a lesser price and only purchase necessities when shopping. When it comes to wastefulness, in a weak economy, buyers place a premium on quality and durability; as a result, they waste less (Shama, Citation1978). Because consumers are more inclined to devote more time and attention to informational advertising regarding product attributes and costs, marketing campaigns should emphasize rational objectives such as safety, reliability, and durability above image and status (Ramish et al., Citation2019).

5.1. Theoretical implications

This study emphasizes the importance of the role of marketing mix and its significant influence on consumers’ Purchase Behavior using the mediating role of consumers’ Habits. The conceptual framework developed in the study was based on stimulus-organism-response (SOR) model. In the context of variables referring to the Product, Price, Place, and Promotion, this study supports and extends the theoretical dimensions of Stimulus-Organism-Response model in the marketing research. This study validates the effect of marketing mix elements in shaping the consumers purchase behavior during the COVID-19. It is observed that people begin to order or make purchases that were more than their usual usage, stockpiling them for emergencies. If the consumer observes that commodities supplies are scarce, even though the likelihood of this happening is extremely low, risk aversion drives this behavior. As it is consistent with human nature, this action cannot be totally characterized as irrational. This study establishes the role of consumer habits in shaping the consumer purchase behavior in response to change in the marketing mix elements.

5.2. Practical implications

Consumers are affected by the economic crisis on both a financial and psychological level; consumer despair is associated with the economic recession from a psychological standpoint, because consumers are fearful of losing their employment, their assets, or both because of the uncertain situation of the pandemic. Stress and worry cause a loss of control, causing people to engage in well-learned or habitual actions. Given the importance of the danger perception in crises, retailers may be less likely to see crises as sources of opportunities.

Retailers cannot modify customer attitudes but can offer good value for money as consumers become more frugal and price-conscious and rather than focusing on sporadic discounts, they should offer value for money. During the pandemic, loyal customers explored purchasing goods from competitors as well as looking for reduced prices. Retailers should not reduce marketing campaigns both physical and online as continue to attract and retain consumers. Apparel retailers should create loyalty programs and give discounts to members of loyalty programs motivating consumers to buy from their stores only. Fashion retailers must be aware of their customers’ insecurities, specific needs, reasonable response times, and potential health dangers during the in-store shopping experience, and they must not underestimate the impact of retail service on their customers’ sense of well-being. Retailers should make it obvious that their top priority is to safeguard their customers’ safety and well-being, not profit, while still providing them with the goods they require on time.

5.3. Limitations & future research directions

This study does have some limitations, which must be recognized. Sample was taken from the metropolitan city of Pakistan where people live belonging to different sects, creed, and cast. However, rural areas are ignored in this research. To get a better generalization of the findings, future research should include a larger variety of respondents in terms of both rural and urban areas. The instrument used in this research can be tested in different cultures and countries with varying economic levels, too. Our understanding of this subject could also be enhanced by future research that focuses on cross-cultural comparisons. Studying the effects of a crisis over time or comparing the effects of different crises will help us better understand consumers’ adjustment behavior during a crisis. Further research into gender segmentation towards buying options whether they prefer buying online or through physical outlets would help retailers target them through relevant channels.

Author contributions

“Conceptualization, SQ, JA, and MAB.; methodology, SQ, and MAB.; software, ZW.; validation, MAB and MR; data curation, SQ, JA, MABS.; writing—original draft preparation, SQ.; writing—review and editing, MAB, SA, and JA.; supervision, MA.; project administration, MR and ZW;.

Institutional review board statement

Not applicable because this study is not based on any experimental design considering humans or animals as subjects

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmed, A., & Ansari, J. (2023). The role of Social Commerce towards purchase intention of fast food amongst karachiites in post-COVID-19: A moderating effect of SERVQUAL. Human Nature Journal of Social Sciences, 4(2), 672–18.

- Akers, R. (2020). Consumer behavior: Now and post pandemic. Total Retail. https://www.mytotalretail.com/article/consumer-behavior-now-and-post-coronavirus-pandemic/

- Ali, K. (2020). COVID-19 and innovation in retail. Pakistan’s Growth Story.

- AlTarrah, D., AlShami, E., AlHamad, N., AlBesher, F., & Devarajan, S. (2021). The impact of coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic on food purchasing, eating behavior, and perception of food safety in Kuwait. Sustainability, 13(16), 8987. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168987

- Altay, B. C., Okumuş, A., & Adıgüzel Mercangöz, B. (2021). An intelligent approach for analyzing the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on marketing mix elements (7Ps) of the on-demand grocery delivery service. Complex & Intelligent Systems, 8(1), 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40747-021-00358-1

- Ang, S. H. (2000). Personality influences on consumption: Insights from the Asian economic crisis. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 13(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1300/J046v13n01_02

- Ang, S. H. (2001). Crisis marketing: A comparison across economic scenarios. International Business Review, 10(3), 263–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0969-5931(01)00016-6

- Ang, S. H., Leong, S. M., & Kotler, P. (2000). The Asian Apocalypse: Crisis marketing for consumers and businesses. Long Range Planning, 33(1), 97–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-6301(99)00100-4

- Azeema, N., Jayaraman, K., & Kiumarsi, S. (2016). Factors influencing the purchase decision of perfumes with habit as a mediating variable: An empirical study in Malaysia. Indian Journal of Marketing, 46(7), 7. https://doi.org/10.17010/ijom/2016/v46/i7/97124

- Azmy. (2020). How the pandemic is changing consumer behavior. DAC.

- Bakewell, C., & Mitchell, V.-W. (2006). Male versus female consumer decision making styles. Journal of Business Research, 59(12), 1297–1300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.09.008

- Bakhtairi, K. (2020). How {Will} {The} {Pandemic} {Change} {Consumer} {Behavior}.

- Bashir, M. A., Ali, N. A., & Jalees, T. (2020). Impact of brand community participation on brand equity dimension in luxury apparel industry-A structural equation modeling approach. South Asian Journal of Management, 14(2), 263–276.

- Bayraktaroğlu, G., & AliMen, N. (2011). Consumption adjustments of Turkish consumers during the global financial crisis. Ege Akademik Bakis (Ege Academic Review), 11(2), 193. https://doi.org/10.21121/eab.2011219564

- Bhatti, A. (2018). Consumer purchase intention effect on online shopping behavior with the moderating role of attitude. International Journal of Academic Management Science Research, 2(7), 7.

- Bhatti, A., Akram, H., Basit, H. M., Khan, A. U., Raza, S. M., & Bilal, M. (2020). E-commerce trends during COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Future Generation Communication and Networking, 13(2), 5.

- Bidyut Jyoti, G. (2020). Changing consumer behavior: Segmenting consumers to understand them better. International Journal of Management, 11(Issue 5), 10.

- Billore, S., & Anisimova, T. (2021). Panic buying research: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(4), 777–804. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12669

- Carpenter, C. M., Wayne, G. F., & Connolly, G. N. (2005). Designing cigarettes for women: New findings from the tobacco industry documents. Addiction, 100(6), 837–851.

- Chan, J. (2020). How to Adapt Your Strategy During the Coronavirus Lockdown – and What to Anticipate After the Crisis is Over | WARC. http://origin.warc.com/newsandopinion/opinion/how-to-adapt-your-strategy-during-the-coronavirus-lockdown–and-what-to-anticipate-after-the-crisis-is-over/3409

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern methods for business research (pp. 295–335). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Coccia, M. (2022). Preparedness of countries to face COVID-19 pandemic crisis: Strategic positioning and factors supporting effective strategies of prevention of pandemic threats. Environmental Research, 203, 111678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.111678

- Cranfield, J. A. L. (2020). Framing consumer food demand responses in a viral pandemic. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics/Revue Canadienne D’agroeconomie, 68(2), 151–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/cjag.12246

- Darley, W. K., & Smith, R. E. (1995). Gender differences in information processing strategies: An empirical test of the selectivity model in advertising response. Journal of Advertising, 24(1), 41–56.

- Development, C. (2020). The Imf and COVID-19 (Coronavirus) Fostering Inclusion in Mexico. IMF.Org.

- Dittmar, H., & Drury, J. (2000). Self-image – is it in the bag? A qualitative comparison between “ordinary” and “excessive” consumers. Journal of Economic Psychology, 21(2), 109–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-4870(99)00039-2

- Donovan, R. (1994). Store atmosphere and purchasing behavior. Journal of Retailing, 70(3), 283–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4359(94)90037-X

- Ellison, B., McFadden, B., Rickard, B. J., & Wilson, N. L. (2021). Examining food purchase behavior and food values during the COVID-19 pandemic. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 43(1), 58–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/aepp.13118

- Fischer, E., & Arnold, S. J. (1994). Sex, gender identity, gender role attitudes, and consumer behavior. Psychology & Marketing, 11(2), 163–182. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.4220110206

- Gagnon, M.-P., Godin, G., Gagné, C., Fortin, J.-P., Lamothe, L., Reinharz, D., & Cloutier, A. (2003). An adaptation of the theory of interpersonal behaviour to the study of telemedicine adoption by physicians. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 71(2–3), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1386-5056(03)00094-7

- Grabara, D. (2021). iPhone 11 premium mobile device offers on e-commerce auction platform in the context of marketing mix framework and COVID-19 pandemic. Procedia Computer Science, 192, 1720–1729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2021.08.177

- Hagger, M. S. (2019). Habit and physical activity: Theoretical advances, practical implications, and agenda for future research. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 42, 118–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.12.007

- Hair, J. F. K., Jr., Hult, G. T. M. H., Ringle, C. M., & Sarsedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 414–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6

- Hassan, A. (2020). Economic impact of Coronavirus and revival measures. 9.

- Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(1), 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382

- Herter, M. M., dos Santos, C. P., & Pinto, D. C. (2014). “Man, I shop like a woman!” the effects of gender and emotions on consumer shopping behaviour outcomes. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 42(9), 780–804.

- Hirachigadzhieva, M. M. (2020). Marketing Strategies for Crisis Management. Complex of Anti Crisis Measures in the Field of Marketing. Nauchniy Almanach, 2-1(64), 78–82.

- Holman, N. (2020). Kantar covid-19 barometer reveals shifts in consumer attitudes, expectations of brands. Media Village. https://www.mediavillage.com/article/kantar-covid-19-barometer-reveals-shifts-in-consumer-attitudes-expectations-of-brands/

- Jones, J. S., Murray, S. R., & Tapp, S. R. (2018). Generational differences in the workplace. The Journal of Business Diversity; West Palm Beach, 18(2), 88–97.

- Kaytaz, M., & Gul, M. C. (2014). Consumer response to economic crisis and lessons for marketers: The Turkish experience. Journal of Business Research, 67(1), 2701–2706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.03.019

- Kitayama, S., Camp, N., & Salvador, C. (2022). Culture and the COVID-19 pandemic: Multiple mechanisms and Policy implications. Social Issues and Policy Review, 16(1), 164–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12080

- Koos, S., Vihalemm, T., & Keller, M. (2017). Coping with crises: Consumption and social resilience on markets. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 41(4), 363–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12374

- Kotler, P., & Keller, L. K. (2012). A framework for marketing management (5th ed.). Pearson.

- Limayem, M., Hirt, S. G., & Cheung, C. M. (2007). How habit limits the predictive power of intention: The case of information Systems continuance. MIS Quarterly, 31(4), 705–737. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148817

- Ling, A. P. A. (2007). The impact of marketing mix on customer satisfaction: A case study deriving consensus rankings from benchmarking. NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF MALAYSIA.

- Lissitsa, S., & Kol, O. (2016). Generation X vs. Generation Y – a decade of online shopping. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 31, 304–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.04.015

- Lund, C., Brooke-Sumner, C., Baingana, F., Baron, E. C., Breuer, E., Chandra, P., Haushofer, J., Herrman, H., Jordans, M., Kieling, C., Medina-Mora, M. E., Morgan, E., Omigbodun, O., Tol, W., Patel, V., & Saxena, S. (2018). Social determinants of mental disorders and the sustainable development goals: A systematic review of reviews. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5(4), 357–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30060-9

- McKinsey. (2020). Consumer sentiment and behavior continue to reflect the uncertainty of the {COVID}-19 crisis. McKinsey. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/growth-marketing-and-sales/our-insights/a-global-view-of-how-consumer-behavior-is-changing-amid-covid-19

- Megbolugbe, I., Marks, A., & Schwartz, M. (1991). The economic theory of housing demand: A critical review. Journal of Real Estate Research, 6(3), 381–393.

- Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). The basic emotional impact of environments. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 38(1), 283–301. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1974.38.1.283

- Mehta, S., Saxena, T., & Purohit, N. (2020). The new consumer behaviour paradigm amid COVID-19: Permanent or transient? Journal of Health Management, 22(2), 291–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972063420940834

- Meldrum, M., & McDonald, M. (2007). Marketing in a nutshell: Key concepts for non-specialists. Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Meshko, N., & Savinova, A. (2020). Digital marketing strategy: Companies experience during pandemic. VUZF Review, 5(4), 41–49. https://doi.org/10.38188/2534-9228.20.4.05

- Molarius, A., & Persson, C. (2022). Living conditions, lifestyle habits and health among adults before and after the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak in Sweden - results from a cross-sectional population-based study. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 171. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12315-1

- Nguyen, A. (2020). Social media and influencer marketing towards consumers’ buying behavior: The emerging role of millennials in Ho Chi Minh city.

- Niazi, A. (2020). The pandemic is e-commerce’s time to shine. {But} will it last? Profit by Pakistan Today, 6–11. https://profit.pakistantoday.com.pk/2020/05/04/the-pandemic-is-e-commerces-time-to-shine-but-will-it-last/

- Pak, A., Adegboye, O. A., Adekunle, A. I., Rahman, K. M., McBryde, E. S., & Eisen, D. P. (2020). Economic consequences of the COVID-19 outbreak: The need for epidemic preparedness. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 241. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00241

- Peter, J. P., Olson, J. C., & Grunert, K. G. (1999). Consumer {Behaviour} and {Marketing} {Strategy}. McGraw-Hill.

- Prabowo, H., & Sriwidadi, T. (2019). The effect of marketing mix toward brand equity at higher education institutions: A case study in BINUS online learning Jakarta. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities, 27(3), 1609–1616.

- Prentice, C., Chen, J., & Stantic, B. (2020). Timed intervention in COVID-19 and panic buying. Journal of Retailing & Consumer Services, 57, 102203.

- Quelch, J., & Jocz, K. E. (2009). How to market in a Downturn. Harvard Business Review, 2009(53), 37–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/ltl.340

- Ramish, M. S., Jalees, T., & Bashir, A. (2019). Visual Appeal of Stock Photographs Affecting the Consumers’ Attitide towards Advertising. Global Management Journal for Academic & Corporate Studies, 9(1), 1–7.

- Rana, W., Mukhtar, S., & Mukhtar, S. (2020). COVID-19 in Pakistan: Current Status and challenges. Journal of Clinical Medicine of Kazakhstan, 3(57), 48–52. https://doi.org/10.23950/1812-2892-JCMK-00766

- Reisenwitz, T. H., & Iyer, R. (2009). Differences in generation Xand generation Y: Implications for the organization and marketers. The Marketing Management Journal, 19(2), 91–103.

- Rosberg, J. W. (1979). Is a recession on the way? {It}’s no time to cut ad budgets. Industrial Marketing Management, 1(64), 64–70.

- Saif, N. M., & Aimin, W. (2014). Exploring the value and process of marketing strategy: Review of literature. International Journal of Management Science and Business Administration, 2(2), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.18775/ijmsba.1849-5664-5419.2014.22.1001

- Scapaticci, S., Neri, C. R., Marseglia, G. L., Staiano, A., Chiarelli, F., & Verduci, E. (2022). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on lifestyle behaviors in children and adolescents: An international overview. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 48(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-022-01211-y

- Schewe, C. D., & Meredith, G. (2004). Segmenting global markets by generational cohorts: Determining motivations by age. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 4(1), 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.157

- Scitovszky, T. (1944). Some consequences of the habit of judging quality by price. The Review of Economic Studies, 12(2), 100. https://doi.org/10.2307/2296093

- Shama, A. (1978). Management & consumers in an era of stagflation. Journal of Marketing, 10(3), 43. https://doi.org/10.2307/1250533

- Sharif, S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic: Government relief package and the likely mis-allocation of loans in Pakistan. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3572718

- Sinko, L., Rajabi, S., Sinko, A., & Merchant, R. (2022). Capturing lifestyle changes and emotional experiences while having a compromised immune system during the COVID-19 pandemic: A photo-elicitation study. Journal of Community Psychology, 50(5), 2411–2430. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22784

- Syam, M., Sembiring, B. K. F., Maas, L. T., & Pranajaya, A. (2019). The analysis of marketing mix strategy effect on students decision to Choose Faculty Economics and Business of Universitas Dharmawangsa Medan. International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding, 6(6), 71. https://doi.org/10.18415/ijmmu.v6i6.1173

- Taylor, S. L., & Cosenza, R. M. (2002). Profiling later aged female teens: Mall shopping behavior and clothing choice. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 19(5), 393–408. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760210437623

- Triandis, H. C. (1977). Theoretical framework for evaluation of cross-cultural training effectiveness. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 1(4), 19–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(77)90030-X

- Venkatesh, Thong, & Xu. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly, 36(1), 157. https://doi.org/10.2307/41410412

- Wang, Y., Hong, A., Li, X., & Gao, J. (2020). Marketing innovations during a global crisis: A study of China firms’ response to COVID-19. Journal of Business Research, 116, 214–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.029

- Webb, D., Soutar, G. N., Gagné, M., Mazzarol, T., & Boeing, A. (2022). Saving energy at home: Exploring the role of behavior regulation and habit. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 46(2), 621–635. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12716

- Werner, L. R. (1991). Marketing strategies for the recession. Management Review, 80(8), 29–30.

- Williams, K. C., Page, R. A., He, J., Fell, R., Bombardier, J. P., Joo, C.-G., Lentz, M. R., Kim, W.-K., Burdo, T. H., Autissier, P., Annamalai, L., Curran, E., O’Neil, S. P., Westmoreland, S. V., Williams, K. C., Masliah, E., & Gilberto González, R. (2011). Marketing to the generations. Journal of Medical Primatology, 40(5), 300–309. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0684.2011.00475.x

- Wood, W., & Neal, D. T. (2009). The habitual consumer. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 19(4), 579–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2009.08.003

- Xuanxiaoqing, F. (2012). A study of the factors that affect the impulsive cosmetics buying of female consumers in Kaohsiung. African Journal of Business Management, 6(2), 6(2. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM11.2187

- Yilmaz, H. Ö., Aslan, R., & Unal, C. (2020). Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on eating habits and food purchasing behaviors of university students. Kesmas: Jurnal Kesehatan Masyarakat Nasional (National Public Health Journal), 15(3), 15(3. https://doi.org/10.21109/kesmas.v15i3.3897

- Zurawicki, L., & Braidot, N. (2005). Consumers during crisis: Responses from the middle class in Argentina. Journal of Business Research, 58(8), 1100–1109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2004.03.005

- Zwanka, R. J., & Buff, C. (2021). COVID-19 generation: A conceptual framework of the consumer behavioral shifts to be caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 33(1), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/08961530.2020.1771646

Appendix

I am an MPhil student at IoBM, and I am doing this research on fashion apparel shopping on “Impact of Consumer Consumption Adjustments on Habits and Purchase Behavior during Covid-19: A Study of Fashion Industry in Pakistan.”

Table

Please consider that 1 = Least level of agreement and 5 = Highest Level of agreement