Abstract

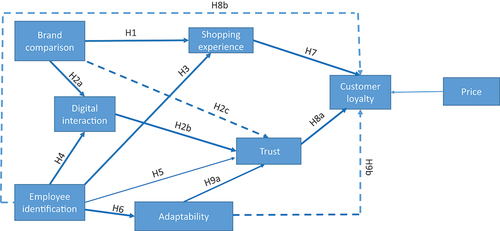

This study investigates Chinese consumers’ interaction with retail employees and the effects on shopping experience, trust, and loyalty. Survey data help articulate brand comparison, digital interactions, and shopping experience as customer-identification change agents. A structural equation model highlights how consumers’ perception of employee identification enhances shopping experience, builds consumer trust, and improves loyalty. The study displays how customer trust mediates the effect of employee identification and retailer adaptability on customer loyalty while digital interaction mediates the effect of brand comparison on customer trust. The theoretical implications of these findings emphasise the importance of consumer-employee interaction in the identification process where the relationships between brand comparison, digital interaction, and shopping experience are highlighted in a retail setting. These results denote that (a) store loyalty is predominantly driven by consumer self-consistence and social conformance and (b) retailer online and offline interaction and coordination influence brand experiences and consumer retention.

1. Introduction

In the e-commerce era, the fusion of brick-and-mortar stores and digital interaction redefines shopping behaviour, requiring retailers to re-focus on consumer/customer loyalty. Digital interactions influence how consumers search, select, purchase, and use products. Consumers use digital devices to browse and compare brands while visiting stores to enhance their overall shopping experiences. Metrics are readily available to retailers to analyse consumer views about product functionality, store image, and brand’s status symbol and value (Teixeira et al., Citation2022).

To attract consumers, retailers use non-systematic strategies like overstocking retail shelves and increasing stock-keeping units (SKUs) instead of interactive personalised approaches (Zani et al., Citation2022). Such strategies increase decision-making complexity, information overload, and confusion—compelling consumers to buy products and brands that they may not want (Walters et al., Citation2020).

Consumer loyalty is the backbone of retailers’ longevity and growth. A small change in loyalty can result in a disproportionately large change in profitability (Agustin & Singh, Citation2005). Consumer loyalty has declined as retailers pursue short-term strategies (e.g. loyalty programmes) instead of winning approaches to retaining consumers (Wolter et al., Citation2017). Most buyers want to improve their knowledge about the products they purchase (Wei Khong & Sim Ong, Citation2014). Shunning close relationships with customers resulted in excessive inventory carrying costs and reduced profits at Best Buy, Nordstrom, Target, and Walmart (Rosenbaum, Citation2022). Loyal consumers search less for brands and retail outlets and provide retailers with economic benefits through feedback, repeat purchases, and referrals (Johnson et al., Citation2006).

Most studies about consumer loyalty focus on its antecedents of the shopping or brand experience or behavioural loyalty via temporal satisfaction in isolation (Argo & Dahl, Citation2020; Moreau, Citation2020). With the widespread adoption of the internet and the growing popularity of online shopping, digital interactions have become increasingly important for retailers to connect with their customers and drive sales. These interactions can occur through various digital channels (including websites, mobile apps, social media, email, and more) and influence shopping behaviours (Argo & Dahl, Citation2020; Liu-Thompkins et al., Citation2022; Moreau, Citation2020; Zani et al., Citation2022). Based on the suggestions of Audrain-Pontevia and Vanhuele (Citation2016), Ruiz-Molina et al. (Citation2021), and Yi et al. (Citation2021), this study reconciles the efforts of digital interaction, shopping experience, and ongoing relationships in customer loyalty rather than treating them in isolation.

Using customer-retailer bonding behaviour to build customer loyalty has been underrated in retail settings (Sirianni et al., Citation2013). We use social identity theory to show that consumer interactions with retailers and their employees can result in positive outcomes (i.e., customer loyalty). Homburg et al. (Citation2009) showed that customer-company identification can lower customer defection. By examining how well retailers utilise the identification process, this study clarifies the effect of shopping behaviour (why and how customers shop and what they look for) and trust as a bonding behaviour on customer loyalty.

We treat brand comparison, digital interaction, and shopping experience as identification agents in the consumer identification process. Acknowledging consumers’ familiarity and high use of digital interactions in consumer identification, we examine its mediating influence in building trust as a bonding behaviour, an essential precursor to customer loyalty (Kupfer et al., Citation2018). Moreover, we show how consumers’ perception of employee identification plays a pivotal role in enhancing shopping experience, building consumer trust, and improving consumer-company adaptability as part of the ongoing relationship. Using the improved adaptability facilitated by e-commerce digital communication gadgets (Zani et al., Citation2022), we investigate the additive effect of retailer adaptability on customer loyalty.

Although customer loyalty can be brand-related, store-related, or a mix, it remains under-researched (Khan & Rahman, Citation2016). Zhang et al. (Citation2017) found the complementary role of store and brand loyalty contributed to customer loyalty. Studies have generally related consumers’ shopping experience to either brand or store loyalty, not both (Liu et al., Citation2012; Liu-Thompkins et al., Citation2022). This study captures the influence of the identification attributes on customer loyalty—a second-order construct comprising brand and store loyalty.

2. Socialidentity shopping behaviour

As part of an individual’s self-concept, social identity is a perceived association with a particular social group that has participation value and emotional significance. Retail employees are influential social groups who are motivated to initiate and nurture social bonding with customers (Bhattacharya & Sen, Citation2003). Such employee-customer interaction involves emotional experiences and personal relationships (Joseph & Unnikrishnan, Citation2016) that are essential for customer loyalty and repeat purchases (Agustin & Singh, Citation2005).

The consumer-retailer identification process occurs through consumer purchasing behaviour and self-expression triggered as an extension of one’s self-concept. Consumers look for brands consistent with their self-concept (Chattaraman et al., Citation2010) and identify themselves to others through brands (Schembri et al., Citation2010). As identification occurs via perceptions, feelings, and evaluations, retailers create a shopping experience to arouse such identification reactions (Rubio et al., Citation2015).

Chinese consumers’ social identity has changed in recent years. Historically, hedonic consumption was viewed as indulgence and wasteful in China. The ethos has its roots in Confucian collectivism that emphasizes social cohesion and group welfare over individual priorities. As incomes have risen and new products and services entered the market, Chinese younger generation have drifted from collectivism. They now associate themselves with Western culture and share the same hedonic shopping traits as conspicuous consumption and variety seeking have become symbols of one’s social status (Xu-Priour & Cliquet, Citation2013).

Being among the world’s most digital nations, China accounts for 50 percent of global e-commerce. China’s consumers continue to use online retail channels for daily necessities such as food and toiletries. The country’s advanced digital and fulfillment infrastructure enable retailers to successfully provide quality service to meet increased consumer demand for online shopping and digital services (International Trade Administration: China – Country Commercial Guide, Citation2021).

Trust and adaptability are two critical attributes in the bonding mechanism (Moorman et al., Citation1992), whose joint influence on customer loyalty has not been explored in retail environments. Trust is the confidence and willingness to rely on exchange partners’ abilities, integrity, and benevolence over self-interest (Moorman et al., Citation1992). Consumer trust in the company leads to positive product perception and evaluation (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, Citation2001). Trust in exchange for partners’ reliability and integrity enhances relationships and influences brand loyalty (Harris & Goode, Citation2004).

Adaptability is the adjustment in one’s behaviour to respond to uncertainty, new information, and circumstances (Martin et al., Citation2013). To solidify relationships with their customers, organisations must be sensitive and adaptable to changing consumer needs (Zhang et al., Citation2005).

A shopping experience includes how consumers sense, feel, and think about the store and its brands (Lemon & Verhoef, Citation2016), whereas bonding occurs when a customer feels appreciated and valued by the organisation and engages in personal relationships with employees. The accrued emotional experience imbues trust and enhances customer relationship, retention, and loyalty (Yi et al., Citation2021).

Past studies have related consumer-shopping experience to either brand or store loyalty (Liu et al., Citation2012). These studies are less relevant in today’s digital shopping environment where consumers use omni-channel communication and store access to improve their shopping and bonding behaviours (Teixeira et al., Citation2022).

3. Hypotheses

3.1. Brand comparison and shopping experience

Consumers typically participate in shopping experience activities like finding brands and visiting retail stores before deciding on purchasing. As these experiences can occur anytime during brand identification, retailers must provide memorable shopping experiences at every touchpoint (Brakus et al., Citation2009). Applying and testing cosmetics in a retail store are opportunities for consumers to interact with brands, store attendants, and other consumers to form preferences (Homburg et al., Citation2009). Such social interaction can influence consumers’ thoughts, feelings, and behaviours (Argo & Dahl, Citation2020).

As the shopping experience varies for each consumer, it provides retailers with opportunities to influence and customise the consumer experience. A retailer provides brand stimulus through brand identity, store atmospherics, packaging, and other associative cues to stimulate brand differences. To be effective, such stimuli should be recognised and felt by consumers (Roggeveen et al., Citation2021). Using brand comparison, consumers can discern the degree of superiority among brands (Sivakumar, Citation2004). The retailer can create assortments of product-service features to match consumer behaviour of variety-seeking and/or confirming repeat selections while encouraging brand comparison (Raju, Citation1980). This form of brand identification reflects one’s self-concept and image and contributes to the shopping experience—forming part of the identification process (Liu et al., Citation2012).

H1:

Consumer-brand comparison is positively related to consumer-shopping experience.

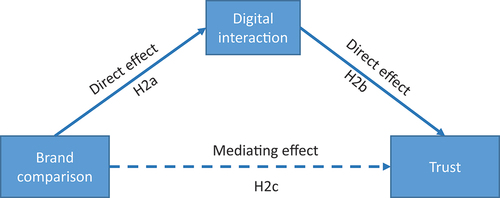

3.2. Brand comparison, digital interaction, and store trust

How brands differ from one another creates a meaningful dialogue among consumers. The availability of real-time information is important and incumbent upon the efficient use of digital communication tools. When consumers anthropomorphise and trust the brand, using social-media communication is positively associated with this consumer-brand relationship (Roggeveen et al., Citation2021).

Retailers increasingly use digital marketing to improve consumers’ joy and efficiency in retrieving information and participating in social interactions (Roggeveen et al., Citation2021). Digital communication provides retailers with opportunities to become consumer-centric by boosting capabilities to serve consumers in stores and through digital channels. Understanding how consumers can identify with the retailer using digital tools is essential for building customer loyalty—an integral part of the identification process (Kupfer et al., Citation2018).

H2a:

Brand comparison is positively related to consumer digital interaction.

Willingness to rely on brand information and performance improves trust in the brand (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, Citation2001). Consumer participation in brand-related messaging and consumptive discussions, using electronic communication tools, while consuming the brand improves brand identification (Kupfer et al., Citation2018).

H2b:

Consumer digital interaction is positively related to consumer trust in retailers.

Digital interaction technologies allow consumers to evaluate and share their experiences and feelings about product usage moments and trust the brand in real time (Mascarenhas et al., Citation2006). Such experiences provide retailers with the opportunity to influence consumers’ decisions and identification by bringing reliable, relevant, and timely information about the stores and brands (Schau et al., Citation2009). Many consumers are receptive to advice and personalised information from retailers that support their feelings (Roggeveen et al., Citation2021).

H2c:

Consumer digital interaction positively mediates the relationship between brand comparison and trust.

3.3. Employee identification, shopping experience, retailer trust, and adaptability

Consumers’ cognitive and emotive responses to evaluate and purchase a brand can occur at any point during the shopping experience. Hence, the retailer may benefit by nurturing the identification process throughout the shopping journey (Hughes et al., Citation2019; Moreau, Citation2020). For beauty-product retailers, these opportunities arise when consumers and retail employees jointly perform several value-added shopping tasks during the product examination (e.g. in-store trials), evaluation, and purchase.

Employee identification motivates employees to recognise consumer needs and share their expertise and personal insight with consumers, which are superior forms of communication where consumers require careful deliberation about beauty products (Hughes et al., Citation2019). Employees are intrinsically motivated to espouse positive thoughts and actions through identification with retail organisations (Manzoor et al., Citation2021). Such social bonding during service encounters involves emotional experiences that emphasise friendship-based customer relationships (Joseph & Unnikrishnan, Citation2016 Vredenburg & Bell, Citation2014).

Although employees’ product/store knowledge and skills are important in identification processes, how they work towards oneness with retail organisations while serving customers takes precedence. Simple employee—customer interactions do not summon employees’ energy as does their sense of belonging and identification with the organisation (Homburg et al., Citation2009). Testing different products, absorbing cues from the store’s ambiance, and examining one’s needs are common consumer-shopping behaviours for cosmetic products; employees can eagerly participate in this process to improve shopping experience. Employee authenticity and consumer believability in employee’s brand-aligned behaviour enhances brand experience (Sirianni et al., Citation2013).

H3:

Employee identification is positively related to consumer shopping experience.

Although shoppers visit stores to view, touch, and try products, they also interact with sales staff to understand brand functionality and value. Employee-customer identification encourages real-time chat using the convenience of the digital environment (Hughes et al., Citation2019). Rational and emotional employee-customer bonding experiences enable consumers to realise the tangible and intangible benefits of a product, its application, convenience of use, and return policies (Yi et al., Citation2021).

H4:

Employee identification is positively related to consumer digital interaction.

Employee identification positively influences consumers’ trust in companies (Bhattacharya & Sen, Citation2003; Chaudhuri & Holbrook, Citation2001). Employees who believe in retailers’ business philosophies and practices share their beliefs, knowledge, and personal experiences with consumers; they convey evidence-based insights about products and their usage to build trusting relationships with the consumer (Keh & Xie, Citation2009).

Service interactions from examining the virtue of a product and its use to sharing rational and emotional interactions require consumers’ and retail employees’ undivided attention (Grewal & Roggeveen, Citation2020; Hughes et al., Citation2019). Employee-consumer interactions contribute to this bonding when the consumer finds out that the employee is knowledgeable and caring. To earn their trust, consumers expect store employees to listen to their feedback, protect their information, and resolve issues.

H5:

Employee identification is positively related to consumer trust.

Although consumer bonding comes from personal relationships with service providers, the types of bonding experiences that may entice loyalty require clarification. Adaptable retailers offer the most suitable products at optimal times and in right places to please consumers (Sunikka & Bragge, Citation2012). Adaptable service and communication methods can foster loyalty when shopping for beauty products.

Reciprocally, retail employees and consumers need to be adaptable in listening to each other’s expertise and experiences about the product performance on different skin textures during the trial and consultation process. Palmatier et al. (Citation2009) found that consumers express gratitude if the retail employees adapt to the consumers’ needs for the incentives they offer (i.e. gifts and tokens). Service adaptability encourages consumer participation, creates critical bonding with employees, and leads to customer loyalty (Henao Colorado & Tavera Mesías, Citation2022).

H6:

Employee identification is positively related to retailer adaptability.

3.4. Shopping experience and customer loyalty

Creating a distinctive and memorable shopping experience entices customers to return and interact with brands and stores. Customer loyalty is strengthened by shopping experiences that solidify powerful psychological connections—not by frequency points or rewards programmes (McPartlin & D’Alessandro, Citation2012). Therefore, delivering the right shopping experience through product quality and aesthetics, ease of access, use of offerings, and service support can enhance customer identity and connection with others and have a lasting effect on customer loyalty. These sensory stimuli enable consumers to emotionally identify with the experience, escape from their routine, and motivate them to use the store (online and offline) as a place to socialise, discuss new ideas, and share information. These stimuli can trigger loyal consumption (Homburg et al., Citation2009).

Consumers who identify with a retailer are intrinsically motivated to generate and share their insights and emotions about their experience with the retailer. Brands’ quality, elegance, innovativeness, expert service, and personal touch are topics of discussion. When buying beauty products, consumers prefer the human touch that comes with the in-store experience over e-commerce, with 67% preferring to buy beauty products in stores (Cohen, Citation2020). Store layout of brands and how they are positioned within the store motivate shoppers’ efforts while making brand decisions (Grewal & Roggeveen, Citation2020). Additionally, retailers’ personalised approaches can create unique experiences that enhance customers’ self-concept and motivate them in identifying and expressing loyalty to the retailer (Audrain-Pontevia & Vanhuele, Citation2016).

H7:

Shopping experience is positively related to consumer loyalty.

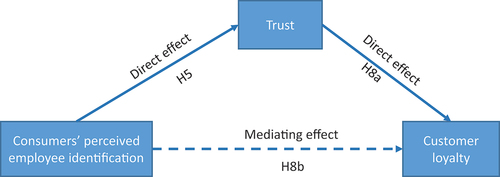

3.4.1. Trust and loyalty

Trusting a brand and its retailer is an integral part of customer loyalty. Consumers’ perceived trustworthiness of an organisation contributes to a positive evaluation of products and influences loyalty (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, Citation2001). Additionally, trust mediates the effect of consumer-employee identification and customer loyalty (Ashforth et al., Citation2008). Any trustworthy brand information or a positive retail experience perceived by consumers may cogently improve customer loyalty (Kupfer et al., Citation2018). He et al. (Citation2012) determined that brand identification had direct and indirect effects on brand trust and indirect effects on brand loyalty for skincare products in Taiwan.

H8a:

Consumer trust and loyalty are positively related.

H8b:

Consumer trust positively mediates the relationship between employee identification and customer loyalty.

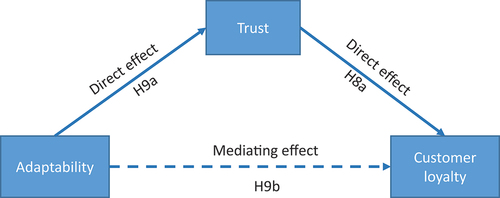

3.4.2. Adaptability and loyalty

Consumers display adaptability in viewing, sharing, and communicating their experiences when they tag someone else’s social-media content to formulate their social posts about products and services. Further, retailers create adaptive digital settings and apps to encourage such practices among consumers (Zani et al., Citation2022).

We propose that retailers and consumers may practice adaptability via product and service differentiation strategies while focusing on loyalty. The goal is to make shoppers feel unique, special, and emotionally connected while trusting to improve their shopping experience.

H9a:

Retailer adaptability is positively related to consumer trust.

H9b:

The relationship between retailer adaptability and customer loyalty is mediated by consumer trust.

4. Methodology

To test the stated hypotheses of consumer interaction with retail employees and their impact on shopping experience, trust, and loyalty, the study uses a quantitative methodology based on survey research. It focuses on collecting, testing and measuring study participants’ responses to survey questions as detailed below.

4.1. Data collection

Survey respondents were female students at a large public university in China. University students represent an important market segment as they espouse exploratory behaviours for shopping goods and branded products (Liu et al., Citation2012). Women generally interact within a small group of cohorts to enhance their decision-making prowess. They identify with retailers that communicate with them within their comfort zone to provide simplified and correct product information to reduce consumptive risk (Audrain-Pontevia & Vanhuele, Citation2016).

In China, cosmetic products are predominantly consumed by women, who spend 3.8 hours, versus 2.2 hours for men, per week on personal grooming. Younger women seem to consume more cosmetics as 36% of sales are attributed to the 20–29 age group, compared to 26% for the 30–39 age cohort (Daxue Consulting, Citation2020). The rising purchasing power of younger Chinese consumers has encouraged popular international cosmetics retailers like Sephora and Barcelona to enhance their presence in major shopping malls and attract young female consumers. Thus, our student-based sample’s characteristics match the purpose of this study.

Students were approached in university classrooms, cafeterias, and libraries. Before administrating the survey, they were qualified as regular users of beauty products (non-medicinal products). While focusing on their preferred cosmetics retailer irrespective of where they purchase (i.e. the retailer’s website or other e-commerce platforms), they were asked to complete the survey. Using this convenience sampling method, 150 completed responses were obtained.

4.2. Measurement instrument

Each questionnaire item was measured on a five-point Likert-type agree/disagree scale. Four brand comparison items among the several brand-switching items in Raju (Citation1980) that were relevant to our investigation were selected. We removed a question—“I enjoy trying different brands of beauty products for the sake of comparison”—whose bivariate correlation with the other three items was low. Moreover, the item displayed a very low correlation with other associated constructs of shopping experience and digital interaction. Four items were adopted from the “engagement and interactivity” scales that reflect consumers’ digital interaction with other consumers (Boateng & Narteh, Citation2016). Three items that specifically focus on employee identification were selected from Kumar and Pansari (Citation2014).

As the benevolence and credible trust items cross-loaded (Katsikeas et al., Citation2009), they were combined after deleting the following items: “This retailer is knowledgeable regarding their products”, “This retailer is not open in dealing with me”, “This retailer cares for me”, and “This retailer sides with me”. These items may not contribute to the employee identification process for cosmetic products as the retailer’s knowledge may not reflect the employee’s knowledge of the product, its applications, and its benefits. The adaptability scale was adopted from business-to-business purchasing (Noordewier et al., Citation1990). Brand loyalty items were adopted from Chaudhuri and Holbrook (Citation2001). The three-item scale of store loyalty was adopted from Kongarchapatara and Shannon (Citation2016).

To reduce common method biases, precautions were taken while designing the questionnaire. An introductory statement ensured the anonymity of participants and their responses. The dependent and independent items were counterbalanced throughout the questionnaire, which may rule out the ease of predicting the model for the study. Using varimax principal component analysis on the six independent variable items, six factors emerged, explaining 67.3% of the variance with the cumulative percentage changing from 13.6 to 25.4, 37.1, 47.6, 57.5, and 67.3 percent respectively. No single factor emerged as dominant, which suggests that common methods bias was not an issue (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003).

Table displays the loadings, t- and p-values, and fit indices of the measurement model. Each scale’s composite reliability is deemed acceptable (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation1988). The average variance extracted for each construct is greater than the square of its correlation with each of the other constructs. Moreover, the 95% confidence interval of the error terms around the correlation estimates between any pair of the eight constructs does not include 1.0, establishing discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Convergent validity is acceptable as the items loaded significantly on their respective constructs with their t-values being greater than 2.0 and p < .05 (Bollen, Citation1989). The results indicate that the models’ χ2 values are significant and acceptable (Katsikeas et al., Citation2009).

Table 1. Measurement model for first-order constructs

4.3. Second-order measurement model

For each first-order construct of brand and store loyalty, the unstandardised starting value was set to 1 (Kline, Citation2016). Table displays the loadings, t- and p-values, and fit indices of the second-order factor models. The second-order standardised loadings for store and brand loyalty may be low but acceptable. Additionally, the measurement model was run as a bi-factor loyalty model to check if one of the domains, brand loyalty, explained the model over and above its general factor, customer loyalty.

Table 2. Consumer loyalty as second-order construct

For every bi-factor model, there should be an equivalent full second-order factor model. Other second-order factors are reduced versions of the full second-order model. Consequently, these reduced versions are more parsimonious than the bi-factor model (Chen et al., Citation2006). Initially, factors of customer loyalty (store and brand loyalty) were placed as bi-factors with their items connected to the general factor: customer loyalty. This measurement model was non-positive. After removing store loyalty as a domain while keeping its items in the general factor, the model was re-run, and an acceptable solution was obtained. However, after comparing the original second-order model with this brand loyalty bi-factor model, the results pointed to accepting the less restrictive second-order model (χ2 = 3.03; df = 4; χ2 = 2.65; df = 2). The chi-square value difference between the two models is non-significant.

5. Results

The structural paths in Figure were analysed after controlling for price as college students are generally price conscious. Several respondents noted that they used retail stores for brand comparison and social conversations, and then shopped around using their mobile apps for the best price. Price consciousness was measured via the questionnaire item, “I purchase beauty products through an e-commerce website because of the lowest pricing.” Further, as the price is correlated with customer-brand comparison and employee-company identification, covariance paths were drawn between them before testing the model.

Table indicates that the structural model of Figure provides good-fit measures. All hypotheses were confirmed with t-values >1.96 except for the link between employee identification and trust (t = 1.88), which is marginally supported. Further, the addition of the path from brand comparison to trust did not improve the model fit; therefore, the positive mediating effect between brand comparison and trust, H2c, prevailed (t > 1.96). Adding direct paths from brand comparison, employee identification, and adaptability to customer loyalty one at a time did not improve the model fit either. Thus, trust seems to be mediating the effect of employee identification and adaptability on customer loyalty, supporting H8b and H9b (Figures , and ).

Table 3. Structural equation model parameter standardized estimates

6. Discussion

The findings indicate that brand and store loyalty should be treated in combination to explain customer loyalty for retailers; neither store loyalty nor brand loyalty as a bi-factor explained customer loyalty over the generalised path model. Retailers and the brands they carry compete for each other’s loyalty share (Zhang et al., Citation2017). This issue may be more prevalent in e-commerce platforms because consumers have additional attributes like convenient search engines, push-button ordering, and logistical convenience to compare and switch brands (Hashimoto et al., Citation2021). Additionally, finding a positive effect from the shopping experience and retailer trust to customer loyalty supports the second-order model.

Another plausible explanation for the second-order effect is that China’s economy comprises a market economy with an authoritarian political system that influences the general population’s belief in utilitarian consumption (Jung & Mittal, Citation2020). However, these consumers are willing to pay for better quality and value by spending time exploring product variations (Atsmon et al., Citation2010).

6.1. Theoretical implications

Theoretically, this study contributes to the literature of consumer social identification in a retail environment by elaborating on the effect of brand comparison, digital interaction, and shopping experience on customer loyalty. It emphasises the importance of consumer-employee interaction in the identification process (Bhattacharya & Sen, Citation2003; Hughes et al., Citation2019). Moreover, findings show that digital interaction is important for retailers as it mediates the effect of brand comparison and employee identification on consumer trust. Additionally, trust mediates the effect of adaptability on customer loyalty. These results advance the following findings: (a) store loyalty is predominantly driven by consumer self-consistence and social conformance in China (He & Mukherjee, Citation2007), and (b) retailer online and offline interaction and coordination influence brand experiences and consumer retention (Ruiz-Molina et al., Citation2021).

Theorists need to pay close attention to the relationship between brand comparison, digital interaction, and shopping experience, which explains the consumer identification process in a retail setting. The results corroborate those of Kupfer et al. (Citation2018)—that the social-media power (e.g. the number of authentic, persuasive, and exclusive product-related posts) of a partner’s popular brand boosts trust in the brand and enhance sales. Our findings align with Flacandji and Vlad (Citation2022): interactive emerging technology like micro-cloud computing and personalised digital coupons improve retailer and consumer real-time interaction.

Understanding and reacting to the consumer-shopping journey are important (Grewal & Roggeveen, Citation2020). Most shopping experience studies focus on the underlying utilitarian and hedonic value to explain consumption habits (e.g. impulsive, compulsive, and browsing), shopping criteria (Ruiz-Molina et al., Citation2021), brand cannibalisation, and competitive effects (González-Benito & Martos-Partal, Citation2012). Our findings suggest that brand managers should encourage seamless shopping experiences to allow shoppers to compare and interact with brands at every touchpoint and improve their identification with the retailer. Homburg et al. (Citation2009) found employee identification to support customer orientation and consumer identification—positive customer orientation enhances consumer identification. Cai and Shannon (Citation2012) showed that self-enhancement shopping features improve Chinese consumer attitudes toward the time and money spent on shopping and shopping frequency. Our research adds to the social identity literature by specifying employee—customer identification to improve the overall consumer identification process and its impact on the shopping experience and customer loyalty.

6.2. Managerial implications

Our study indicates that multiple brands and SKUs can be effective retail strategies if they enhance consumers’ shopping experiences and emotional bonds with retailers toward consumer loyalty. Retailers should continue to offer shopping atmospherics where consumers can relate to brands. They should proactively pursue consumer interaction via in-store brand trials and free samples to test new SKUs.

Results indicate that employee identification positively affects consumers’ shopping experience and trust with retailers, and adaptability mediates in building trust. By sharing employee-customer experiences with their audience, retailers can enhance trust, brand loyalty, and store loyalty to broaden managerial implications.

Using the logistical convenience of omni-channels, adaptability can be an additional bonding tool besides trust to enhance customer loyalty (Flacandji & Vlad, Citation2022; Wei Khong & Sim Ong, Citation2014). Customer participation may improve consumer social bonding in the service delivery process (Yi et al., Citation2021).

To improve customer interactions and win trust, retailers should treat consumers as internal assets and use digital technology to engage them (Schau et al., Citation2009). Employees may be trained to interface using digital channels such as company/brand websites, mobile apps, chatbots, augmented and virtual realities (AR, VR), and any other channels where the customer touchpoints are virtual. Store atmospherics may be digitally enhanced to match brand attributes for different consumption situations. Retailers may also allow contact employees to use their network and digital platforms for direct and unobtrusive communication with consumers within the store setting (Grewal & Roggeveen, Citation2020). Retailers have been venturing toward the metaverse aided with virtual goods, services, and personalisation to enhance end-to-end customer experience (search, purchase, post-purchase) including in-store shopping (Stephens, Citation2021).

Motivationally, contact employees should be empowered to use adaptability besides trust in their interactions with customers to enhance loyalty. Palmatier et al. (Citation2009) found that authorising employees to give gifts and samples to their customers as a token of their appreciation could generate customer gratitude to return the favour through additional store visits, product inquiries, and repeat purchases.

6.3. Limitations and future research directions

Given the sampling frame and procedure, sample size, and research setting, the generalisability of the results is limited to female college students from a regional university in China. All the hypothesised relations were significant except for the relationship between employee identification and consumer trust. A plausible explanation could be that most service encounters between store employees and customers were remote (digital) than face-to-face (physical) and may need verification and justification. (Ruiz-Molina et al., Citation2021; Zani et al., Citation2022). Generally, users of such products are familiar with face-to-face communication with the service provider and notice non-verbal cues and body language (Liu-Thompkins et al., Citation2022), which can provide opportunities for psychological bonding and building trust.

Additionally, variables such as race, cross-cultural values, and interpersonal skills were not measured. The brand comparison items were assumed to capture the health and safety concerns of consumers. The high correlations between brand comparison, employee-consumer identification, and price may also limit the generalisability of this study to spendthrift college students only. Future research may benefit from different demographic profiles like age, working professionals, and socio-economic status to shed light on potential market segments and growth strategies.

The questionnaire items were adopted from B2B and B2C studies; consequently, items were eliminated or combined to form global scales for constructs like trust. The validity of the instrument may be improved by examining and incorporating the consumer role and type of digital interactions at different stages of the buying process.

7. Concluding remarks

This study used survey data to investigate consumer interaction with retail employees and its effects on shopping experience, trust, and loyalty. It highlighted the importance of employee identification with customers and the role of retailers digital interactions in enhancing customer trust and loyalty. Despite its importance to omni-channel retailing, customer loyalty remains under-researched in today’s competitive retail environment. The findings from this study shed light on customer loyalty in retail setting where shopping takes place both online and in physical stores. The study showed that consumer interactions with retailers and their employees can result in positive shopping experience and loyalty.

The theoretical and managerial implications of the study offer valuable insights for researchers and managers. Theoretically, this study contributes to the literature of consumer social identification in a retail environment by elaborating the effect of brand comparison, digital interaction, and shopping experience on customer loyalty. It emphasises the importance of consumer-employee interaction in the identification process. The study findings offer managerial implications for retailers to train and motivate employees to interact with customers and establish positive emotional bonding, affecting shopping experience and trust. Retailer adaptability such as giving gifts, samples, and specials can be additional bonding tools to enhance customer trust and loyalty.

The generalisability of research findings is limited to the sample size, frame, and sampling procedure as well as the measurement instrument used in this study. Future research can provide additional insights using different demographic and socio-economic profiles to replicate the study findings across customer groups and product categories.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Harash Sachdev

Harash Sachdev (Ph.D. in Marketing, Georgia State University) is a Professor of Marketing and Supply Chain Management at Eastern Michigan University. His research interests include writing cases and research papers in the areas of supply chain management and marketing management. He teaches in the areas of marketing strategy and supply chain management. He has received several best paper awards in marketing and supply chain conferences.

Matthew H. Sauber

Matthew Sauber (Ph.D. in Marketing from University of Texas, Austin) is a marketing professor in the College of Business at Eastern Michigan University (EMU). He specializes in integrated marketing communications (IMC), global business and online teaching and learning. Matt’s research interests include consumer sentiment, omnichannel shopping trends, global value chains and data flows. He has authored many cases in sport and sponsorship marketing as part of the case-writing team at the National Sports Forum (NSF).

References

- Agustin, C., & Singh, J. (2005). Curvilinear effects of consumer loyalty determinants in relational exchanges. Journal of Marketing Research, 42(1), 96–17. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.42.1.96.56961

- Argo, J. J., & Dahl, D. W. (2020). Social influence in the retail context: A contemporary review of the literature. Journal of Retailing, 96(1), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2019.12.005

- Ashforth, B. E., Harrison, S. H., & Corley, K. G. (2008). Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. Journal of Management, 34(3), 325–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308316059

- Atsmon, Y., Dixit, V., Magni, M., & St-Maurice, I. (2010). China’s new pragmatic consumers. The McKinsey Quarterly, 4, 1–13. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/growth-marketing-and-sales/our-insights/chinas-new-pragmatic-consumers

- Audrain-Pontevia, A., & Vanhuele, M. (2016). Where do customer loyalties really lie, and why? Gender differences in store loyalty. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 44(8), 799–813. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-01-2016-0002

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Sciences, 16(1), 74–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02723327

- Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2003). Consumer–company identification: A framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. Journal of Marketing, 67(2), 76–88. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.67.2.76.18609

- Boateng, S. L., & Narteh, B. (2016). Online relationship marketing and affective customer commitment – the mediating role of trust. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 21(2), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1057/fsm.2016.5

- Bollen, K. A. (1989). A new incremental fit index for general structural equation models. Sociological Methods and Research, 17(3), 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124189017003004

- Brakus, J. J., Schmitt, B. H., & Zarantonello, L. (2009). Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 73(3), 52–68. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.73.3.052

- Cai, Y., & Shannon, R. (2012). Personal values and mall shopping behavior: The mediating role of attitude and intention among Chinese and Thai consumers. Australasian Marketing Journal, 20(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2011.10.013

- Chattaraman, V., Lennon, S., & Rudd, N. (2010). Social identity salience: Effects on identity-based brand choices of Hispanic consumers. Psychology & Marketing, 27(3), 263–284. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20331

- Chaudhuri, A., & Holbrook, M. B. (2001). The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing, 65(2), 81–93. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.65.2.81.18255

- Chen, F. F., West, S. G., & Sousa, K. H. (2006). A comparison of bifactor and second-order models of quality of life. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 41(2), 189–225. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr4102_5

- Cohen, A. (2020), “Why only 10% of beauty sales are online, and how to fix the consumer ‘trust gap’”, RockWater, 31 July, available at: https://wearerockwater.com/how-beauty-brands-can-close-the-digital-sales-gap/ Retrieved December 23, 2022).

- Daxue Consulting. (2020), “Selling makeup in China: Analysis of the cosmetics market in China”, 3 January, available at: https://www.daxueconsulting.com/selling-cosmetics-in-china-beauty-and-personal-care-market/ Retrieved December 23, 2022).

- Flacandji, M., & Vlad, M. (2022). The relationship between retailer app use, perceived shopping value and loyalty: The moderating role of deal-proneness. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 50(8–9), 981–995. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-10-2021-0484

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- González-Benito, O., & Martos-Partal, M. (2012). Role of retailer positioning and product category on the relationship between store brand consumption and store loyalty. Journal of Retailing, 88(2), 236–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2011.05.003

- Grewal, D., & Roggeveen, A. L. (2020). Understanding retail experiences and customer journey management. Journal of Retailing, 96(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2020.02.002

- Harris, L. C., & Goode, M. (2004). The four levels of loyalty and the pivotal role of trust: A study of online service dynamics. Journal of Retailing, 80(2), 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2004.04.002

- Hashimoto, N., Katsurai, M., & Goto, R. (2021), “A visualization interface for exploring similar brands on a fashion e-commerce platform”, 2021 IEEE International Conference on Web Services (ICWS), Chicago, IL, USA, pp. 642–644. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICWS53863.2021.00086

- He, H., Li, Y., & Harris, L. (2012). Social identity perspective on brand loyalty. Journal of Business Research, 65(5), 648–657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.03.007

- He, H., & Mukherjee, A. (2007). I am, ergo I shop: Does store image congruity explain shopping behaviour of Chinese consumers? Journal of Marketing Management, 23(5–6), 443–460. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725707X212766

- Henao Colorado, L. C., & Tavera Mesías, J. F. (2022). Understanding antecedents of consumer loyalty toward an emerging country’s telecommunications companies. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 34(3), 270–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/08961530.2021.1951917

- Homburg, C., Wieseke, J., & Hoyer, W. D. (2009). Social identity and the service–profit chain. Journal of Marketing, 73(2), 38–54. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.73.2.38

- Hughes, D. E., Richards, K. A., Calantone, R., Baldus, B., & Spreng, R. A. (2019). Driving in-role and extra-role brand performance among retail frontline salespeople: Antecedents and the moderating role of customer orientation. Journal of Retailing, 95(2), 130–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2019.03.003

- International Trade Administration: China – Country Commercial Guide, 2021. https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/china-ecommerce

- Johnson, M. D., Herrmann, A., & Huber, F. (2006). The evolution of loyalty intentions. Journal of Marketing, 70(2), 122–132. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.70.2.122

- Joseph, M. S., & Unnikrishnan, A. (2016), “Relationship bonding strategies and customer retention: A study in business-to-business context”, IOSR Journal of Business and Management, International Conference on Emerging Trends in Engineering & Management (ICETEM-2016), Kochi, Kerala, India (Vol.1, pp. 38–44).

- Jung, J., & Mittal, V. (2020). Political identity and the consumer journey: A research review. Journal of Retailing, 96(1), 55–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2019.09.003

- Katsikeas, C. S., Skarmeas, D., & Bello, D. C. (2009). Developing successful trust-based international exchange relationships. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(1), 132–155. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400401

- Keh, H. T., & Xie, Y. (2009). Corporate reputation and customer behavioral intentions: The roles of trust, identification, and commitment. Industrial Marketing Management, 38(7), 732–742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2008.02.005

- Khan, I., & Rahman, Z. (2016). E-tail brand experience’s influence on e-brand trust and e-brand loyalty: The moderating role of gender. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 44(6), 588–606. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-09-2015-0143

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Kongarchapatara, B., & Shannon, R. (2016). The effect of time stress on store loyalty: A case of food and grocery shopping in Thailand. Australasian Marketing Journal, 24(4), 267–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2016.10.002

- Kumar, V., & Pansari, A. (2014). The construct, measurement, and impact of employee engagement: A marketing perspective. Customer Needs and Solutions, 1(1), 52–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40547-013-0006-4

- Kupfer, A., Holte, P., Vor der Holte, N., Kübler, R. V., & Hennig-Thurau, T. (2018). The role of the partner brand’s social media power in brand alliances. Journal of Marketing, 82(3), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.15.0536

- Lemon, K. N., & Verhoef, P. C. (2016). Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. Journal of Marketing, 80(6), 69–96. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.15.0420

- Liu, F., Li, J., Mizerski, D., Soh, H., & Abimbola, T. (2012). Self-congruity, brand attitude, and brand loyalty: A study on luxury brands. European Journal of Marketing, 46(7/8), 922–937. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561211230098

- Liu-Thompkins, Y., Khoshghadam, L., Shoushtari, A. A., & Zal, S. (2022). What drives retailer loyalty? A meta-analysis of the role of cognitive, affective, and social factors across five decades. Journal of Retailing, 98(1), 92–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2022.02.005

- Manzoor, F., Wei, L., & Asif, M. (2021). Intrinsic rewards and employee’s performance with the mediating mechanism of employee’s motivation. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.563070

- Martin, A. J., Nejad, H. G., Colmar, S., & Liem, G. A. D. (2013). Adaptability: How students’ responses to uncertainty and novelty predict their academic and non-academic outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 728–746. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032794

- Mascarenhas, O. A., Kesavan, R., & Bernacchi, M. (2006). Lasting customer loyalty: A total customer experience approach. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 23(7), 397–405. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760610712939

- McPartlin, S., & D’Alessandro, P., (2012), “The key to customer loyalty: The total shopping experience”, Forbes, 6 January, available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesleadershipforum/2012/01/06/the-key-to-customer-loyalty-the-total-shopping-experience/?sh=74aaf0d1d22b (Retrieved December 23, 2022).

- Moorman, C., Zaltman, G., & Deshpande, R. (1992). Relationships between providers and users of market research: The dynamics of trust within and between organizations. Journal of Marketing Research, 29(3), 314–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379202900303

- Moreau, C. P. (2020). Brand building on the doorstep: The importance of the first (physical) impression. Journal of Retailing, 96(1), 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2019.12.003

- Noordewier, T. G., John, G., & Nevin, J. R. (1990). Performance outcomes of purchasing arrangements in industrial buyer-vendor relationships. Journal of Marketing, 54(4), 80–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299005400407

- Palmatier, R. W., Jarvis, C. B., Bechkoff, J. R., & Kardes, F. R. (2009). The role of customer gratitude in relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 73(5), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.73.5.1

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Raju, P. S. (1980). Optimum stimulation level: Its relationship to personality, demographics and exploratory behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 7(3), 272–282. https://doi.org/10.1086/208815

- Roggeveen, A. L., Grewal, D., Karsberg, J., Noble, S. M., Nordfält, J., Patrick, V. M., Schweiger, E., Soysal, G., Dillard, A., Cooper, N., & Olson, R. (2021). Forging meaningful consumer-brand relationships through creative merchandise offerings and innovative merchandising strategies. Journal of Retailing, 97(1), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2020.11.006

- Rosenbaum, E. (2022), “The lesson for Main Street from the Walmart, target inventory failures”, CNBC, 6 August, available at: https://www.cnbc.com/2022/08/06/the-walmart-target-inventory-misses-include-a-message-for-main-street.html (Retrieved December 23, 2022).

- Rubio, N., Villaseñor, N., & Oubiña, J. (2015). Consumer identification with store brands: Differences between consumers according to their brand loyalty. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 18(2), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brq.2014.03.004

- Ruiz-Molina, M. E., Gómez-Borja, M. A., & Mollá-Descals, A. (2021). Can offline–online congruence explain online loyalty in electronic commerce? International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 49(9), 1271–1294. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-02-2020-0060

- Schau, H. J., Muñiz, A. M., & Arnould, E. J. (2009). How brand community practices create value. Journal of Marketing, 73(5), 30–51. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.73.5.30

- Schembri, S., Merrilees, B., & Kristiansen, S. (2010). Brand consumption and narrative of the self. Psychology & Marketing, 27(6), 623–637. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20348

- Sirianni, N. J., Bitner, M. J., Brown, S. W., & Mandel, N. (2013). Branded service encounters: Strategically aligning employee behavior with the brand positioning. Journal of Marketing, 77(6), 108–123. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.11.0485

- Sivakumar, K. (2004). Manifestations and measurement of asymmetric brand competition. Journal of Business Research, 57(8), 813–820. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(02)00463-0

- Stephens, D. (2021), “The metaverse will radically change retail”, The Business of Fashion, June 7, available at: https://www.businessoffashion.com/opinions/retail/the-metaverse-will-radically-change-retail/ (Retrieved December 23, 2022).

- Sunikka, A., & Bragge, J. (2012). Applying text-mining to personalization and customization research literature – who, what and where? Expert Systems with Applications, 39(11), 10049–10058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2012.02.042

- Teixeira, R., Duarte, A. L. D. C. M., Macau, F. R., & de Oliveira, F. M. (2022). Assessing the moderating effect of brick-and-mortar store on omnichannel retailing. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 50(10), 1259–1280. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-03-2021-0139

- Vredenburg, J., & Bell, S. (2014). Variability in health care services: The role of service employee flexibility. Australian Marketing Journal, 22(3), 168–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2014.08.001

- Walters, D. J., Hershfield, H. E., Jeffrey Inman, J., & Ratner, R. K. (2020). Consumers make different inferences and choices when product uncertainty is attributed to forgetting rather than ignorance. Journal of Consumer Research, 47(1), 56–78. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucz053

- Wei Khong, K., & Sim Ong, F. (2014). Shopper perception and loyalty: A stochastic approach to modelling shopping mall behavior. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 42(7), 626–642. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-11-2012-0100

- Wolter, J. S., Bock, D., Smith, J. S., & Cronin, J. J., Jr. (2017). Creating ultimate customer loyalty through loyalty conviction and customer-company identification. Journal of Retailing, 93(4), 458–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2017.08.004

- Xu-Priour, D. L., & Cliquet, G. (2013). In-store shopping experience in China and France: The impact of habituation in an emerging country. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 41(9), 706–732. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-05-2013-0108

- Yi, H. T., Yeo, C. K., Amenuvor, F. E., & Boateng, H. (2021). Examining the relationship between customer bonding, customer participation, and customer satisfaction. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 62, 102598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102598

- Zani, N., Mouri, N., & Ahmed, T. (2022). The role of mobile value and trust as drivers of purchase intentions in m-servicescape. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 68, 103060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103060

- Zhang, Q., Vonderembse, M. A., & Lim, J. (2005). Logistics flexibility and its impact on customer satisfaction. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 16(1), 71–95. https://doi.org/10.1108/09574090510617367

- Zhang, C., Zhuang, G., Yang, Z., & Zhang, Y. (2017). Brand loyalty versus store loyalty: Consumers’ role in determining dependence structure of supplier–retailer dyads. Journal of Business-To-Business Marketing, 24(2), 139–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/1051712X.2017.1314127