Abstract

Millennial perspectives on work engagement can aid companies in fostering a more dynamic and successful workforce by recognizing that engaged employees tend to be more productive and satisfied. However, recent polls and studies have raised concerns about the lower levels of work engagement reported among millennials compared to previous generations. To address this, we conducted a study to investigate the potential of gamification to enhance workplace engagement among millennials and delve into the intricate dynamics of this relationship by examining the mediating roles of basic need satisfaction and enjoyment. Utilizing a cross-sectional approach with partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM), we found both direct and indirect positive effects of gamification on work engagement. Specifically, gamification positively influenced work engagement, mediated by basic need satisfaction and enjoyment. Remarkably, generational differences were minimal, as revealed in a multigroup analysis. While our findings demonstrate gamification’s potential to boost millennial work engagement, we acknowledge limitations such as data heterogeneity and small sample size; thus, further research in diverse contexts is needed. In summary, our study highlights gamification as a promising strategy to boost work engagement among millennials. It underscores the importance of addressing psychological needs in gamification design and calls for continued investigation to refine our understanding of these dynamics.

1. Introduction

Work engagement has lately been a well-known concept among scientists and practitioners, whereas an engaged workforce is a source of competitive advantage for businesses, as it has several benefits (Hui et al., Citation2021; Hurtienne et al., Citation2021; Men et al., Citation2020; Monje Amor et al., Citation2020). In the notion of improving company performance (Nazir & Islam, Citation2017; Uddin et al., Citation2019), employees are a valuable resource for increasing the company’s performance (Gillet et al., Citation2018). Thus, companies with high employee work engagement are more productive and generate more revenue, while their customers are more satisfied and loyal (Barreiro & Treglown, Citation2020). Consistent with a work engagement meta-analysis (Christian et al., Citation2011), several studies suggest that employees’ work engagement in any industry can predict their job performance consistently and efficiently (Jaillet et al., Citation2022; Li et al., Citation2021; Ojo et al., Citation2021; Park & Gursoy, Citation2012).

Regarding workforce generation, the importance of millennial employees is also a hot topic (Jain & Dutta, Citation2019; Rissanen & Luoma-Aho, Citation2016; Walden et al., Citation2017). Data show that the millennial generation has begun to dominate the workforce in Indonesia by 2020, whereas millennials already make up nearly half of the global workforce. By 2025, that figure is expected to rise to 75 percent (Gabriel et al., Citation2020). According to a Dale Carnegie Indonesia polls conducted in 2017 and supported by the Indonesian central bureau of statistics, known as BPS, the millennial generation was 88 million people in 2018, or 33.75 percent of the Indonesian population, with 25 percent of millennial employees wholly engaged in their work (Larasati et al., Citation2019). Despite the expectation that millennials will soon dominate the workforce, recent studies suggest that millennials’ work engagement is among the lowest compared to prior generations due to their unique experiences with the previous generation, global issues, rapid technological developments, and workplace automation (Florenthal & Awad, Citation2021; Hassan et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, during the pandemic lockdown in 2020, employees in Indonesia reported high-stress levels during the day, rising to around 46 percent in 2021, while individuals who are engaged but not succeeding are 61 percent more likely to suffer from chronic burnout (Gallup, Citation2022).

Because of changing employee expectations, companies have found it difficult to retain top employees (De Clerck et al., Citation2022). It is vital to realize that the contributions of the millennial generation to the development of state-owned enterprises (SOE) should not be disregarded (Gustomo et al., Citation2019), even though these firms have a dual mandate to improve both economic value and public services over time (Uno et al., Citation2021). Companies have discovered that having a motivated workforce gives them an advantage over their competition (Li et al., Citation2019). The proportion of millennial employees in Indonesian state-owned firms who are highly engaged at work stays below 20% (Mulyati et al., Citation2020). A low work engagement figure indicates a lack of staff commitment and drive (Carter et al., Citation2016); one solution is to implement programs that assist the millennial workforce in aligning their missions with the organization’s goals, allowing them to feel purposeful at work and maintaining or even increasing their engagement at work (Mantouka et al., Citation2019). Organizations such as state-owned corporations may use several nongaming circumstances to improve employee performance and efficiency (Gerdenitsch et al., Citation2020).

In early 2021, an infrastructure services SOE launched the Snake Ladder Gamification (SLG) mobile application (shown in Figure ). In the context of gamified systems, SLG emerges as a dynamic platform that extends knowledge and encouragement by strategically deploying motivational affordances, including reward, self-expression, status, competition, and visibility of achievement. By accommodating these affordances and applying practical mechanisms such as points, badges, and leaderboards on a per-user basis, it effectively fosters an environment that promotes intrinsic motivation and the satisfaction of basic psychological needs, namely competence, autonomy, and relatedness. This comprehensive approach demonstrates the utility of SLG as a tool for increasing user engagement and satisfaction within applications and platforms (Benitez et al., Citation2022).

Growing research defines work engagement as a personal investment in job tasks (Sahni, Citation2021; Walden et al., Citation2017; Wood et al., Citation2020). Employee experience intersects with employees’ expectations, surroundings, and the events that shape their journeys (Rispler & Luria, Citation2021). Employees are more likely to contribute and perform better at work if they enjoy the program provided to meet their well-being needs (Hammedi et al., Citation2020). In many life domains and situations, including employment and the workplace, boosting employee experience through fun activities is becoming increasingly popular (Cornelius et al., Citation2022).

This observation is consistent with earlier research, which aims to make work more enjoyable by completing the work process more beneficial (Cardador et al., Citation2017). Incorporating motivational feelings such as rewards and self-expression may increase the satisfaction of the underlying psychological needs that lead to joy and fun experiences (Murawski, Citation2021; Suh et al., Citation2018). As previous studies have shown, game design elements apply more precise game design patterns and motivational affordances to build an environment that allows people to participate in a pleasurable and engaging experience (García-Jurado et al., Citation2019; Nah et al., Citation2019; Suh & Wagner, Citation2017). Even though some findings suggest that game dynamics and interaction characteristics of gamification improve need satisfaction (Golrang & Safari, Citation2021; Xi & Hamari, Citation2018), not to mention their influence on enjoyment, there is a lack of empirical data showing how gamification’s motivational affordance positively improves basic psychological needs satisfaction (Bitrián et al., Citation2021). While numerous studies have shown that enjoyment positively influences engagement (Dewaele & Li, Citation2021; Frondozo et al., Citation2020).

This study examines the relationship between gamification affordance, basic need satisfaction, enjoyment, and work engagement. It explores the factors influencing work engagement, especially among millennials. This research will help develop effective treatments to increase employee engagement by fully understanding these connected characteristics. To what extent do both basic need satisfaction and enjoyment mediate the relationship between gamification affordance and work engagement? How does gamification affordance affect work engagement directly and indirectly through enjoyment and basic need satisfaction?

2. Theoretical background and hypotheses development

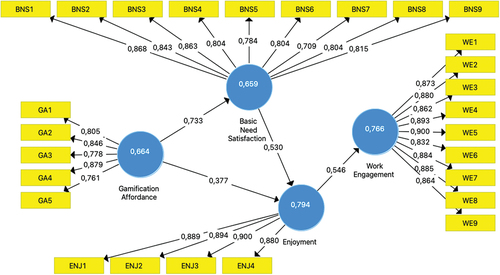

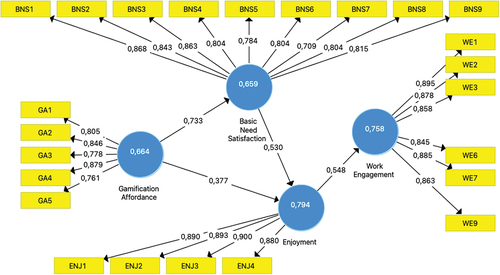

This theoretical framework may aid in comprehending mechanisms that play a crucial role in determining positive effects. Conceptual framework shown in Figure .

2.1. Work engagement

Engagement suggests something extraordinary—something out of the ordinary, if not exceptional (Davies et al., Citation2018); “a positive, fulfilling, and work-related state of mind characterized by vigor, dedication, and total absorption” (Schaufeli & Bakker, Citation2003), as a follow-up to worker engagement, “can be characterized as a psychological state” (Schaufeli et al., Citation2002). Energetic (vigor), emotional (dedication), and cognitive (absorption) make up the central psychological aspect of work engagement (Schaufeli et al., Citation2006). The term “vigor” refers to a collection of interconnected affective states that people experience at work, including physical toughness, emotional vitality, and cognitive liveliness (Bakker et al., Citation2011). The conservation of resources theory-based hypotheses for potential predictors of vigour at work are presented, along with a review of the conceptual framework for fitness and an analysis of prior research on stamina (Eldor, Citation2016). When someone says they feel energized, they mean they have a positive energy balance and a happy or contented mood (Weer & Greenhaus, Citation2017).

Organizations are concerned about employee work engagement because it has the potential to significantly increase corporate profitability (Kwon & Park, Citation2019). Over the last decade, organizations have witnessed massive changes in the labour market, such as increased competition and disruptive innovation, resulting in new work opportunities and occupational hazards (Kniffin et al., Citation2021; Van den Heuvel et al., Citation2020). Whether for business or personal reasons, resources aid employees in remaining engaged while also meeting demands; they can be either a constraining weight or a motivating challenge (Petelczyc et al., Citation2018; Saks, Citation2019). Achieving a delicate balance transcending the resource-demand dichotomy is critical for increasing engagement in demanding activities like innovation (Kwon & Kim, Citation2020).

Work engagement refers to any work challenge that a person faces, whether in a company or as an individual; it demonstrates how a person can have problem-solving abilities, solid innovation, and interpersonal networking skills (Rahmadani & Schaufeli, Citation2022). Fostering a high-engagement culture ensures that everything runs smoothly, according to the organization’s implementation, and that employees respond appropriately to all applicable rules, procedures, and consequences (Gupta & Singh, Citation2021). Work engagement creates a link between the company and individual values; as a result, companies can bring matters to the employee while being responsive to the values conveyed by the employee (Bakker & Leiter, Citation2010; Kang, Citation2018).

2.2. Gamification affordance

Gamification, often defined as “the use of game design elements in nongaming contexts” (Deterding et al., Citation2011), presents a unique challenge due to its subjective nature, as individuals experience gamefulness differently. Therefore, effective gamification frameworks must be adaptable and widely applicable (Deterding, Citation2019). To delve deeper into the concept, we can define gamification as a method of enhancing service by incorporating elements that promote gameful experiences, ultimately enhancing overall user value (Huotari & Hamari, Citation2017).

In gamification, affordance theory proposes that technological capabilities are not inherent to technology but rather emerge from the relationship between users and technological artefacts within a given domain (Treem & Leonardi, Citation2013; Waizenegger et al., Citation2020). Users exhibit various behaviours when interacting with technology; for example, some may seek points and rewards, whereas others may find satisfaction in comparing their progress with co-workers using the same gamification system (Spanellis et al., Citation2020). Additionally, the significance of various gamification levels varies among individual players (Jain & Dutta, Citation2019). Therefore, when designing an effective learning environment within a nongaming context, it is essential to effectively convey the potential actions that the technology affords (Warmelink et al., Citation2020). Gamification affordance is an action that a user perceives as possible when using a gamified system (Suh & Wagner, Citation2017). When applied to game design, the five motivational affordances—reward (REW), self-expression (SEL), status (STA), competition (COM), and visibility of achievement (VIS)—play a pivotal role in encouraging user participation (Suh et al., Citation2017).

The most common system design artefacts used to induce gamification affordances are points, levels, badges, and leaderboards (Saxena & Mishra, Citation2021). Points, the most granular units of measurement in gamification, allow the system to keep track of the user’s actions as they relate to the desired behaviours (Nasirzadeh & Fathian, Citation2020). Levels function as a game mechanic to drive user motivation by presenting users with increasingly complex tasks to complete (Zhang et al., Citation2022). At the same time, leaderboards supplement points and badges with a social, potentially collaborative, or competitive element (Toda et al., Citation2019). When points are delivered in specified and timely amounts, users in a gamified system are more likely to interact dynamically in pursuit of short-term benefits, which boosts prize value (Gündüz & Akkoyunlu, Citation2020), and much more likely to become immersed in the activity for receiving immediate feedback and being able to see the big picture (Rapp et al., Citation2019); thus when talking about Snake-Ladder (SL), rewards affordance refers to how much of a user feels like they can expect to get something in return for doing something (Feng et al., Citation2018). Self-expression affordance enables gamified SL users to distinguish themselves by sticking out from the crowd. Competition and visibility of achievement let users track their levels, leaderboards, and awards (Silic et al., Citation2020).

It is crucial to recognize that technology materiality and user perceptions can shape distinct affordances for different users. Thus, understanding how users perceive motivating affordances is essential when assessing and enhancing engagement within gamified systems.

2.3. Basic need satisfaction

A person’s basic needs are met when they experience a sense of autonomy, or the freedom to act per one’s interests and values, competence, or the belief that one’s actions have the desired effect, and relatedness, or a feeling of belonging to a community (Baard et al., Citation2004; Van den Broeck et al., Citation2010). Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction (BPNS) is a psychological theory of human motivation and personality (Deci & Ryan, Citation1980); it contributes to an individual’s capacity and causes them to interact with their surroundings (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020). Just as in motivation theory, a lack of basic need satisfaction can lead to reduced levels of autonomous motivation, and a lack of BPNS in experiential enjoyment theory can lead to a lack of enjoyment or disinterest in one’s surroundings (Ryan et al., Citation1997). Each of the three fundamental psychological needs—autonomy, relatedness, and competence—is measured by the 9-item Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction Scale (Deci et al., Citation2001; Van den Broeck et al., Citation2008).

In BPNS, autonomy refers to a person’s ability to choose whether or not to perform a task (Adie et al., Citation2008). When a person is exposed to opportunities to learn new abilities, is sufficiently challenged, and receives supportive feedback, their sense of competence grows (Slemp et al., Citation2021). BPNS states that relatedness is discovering psychological needs contributing to motivation and well-being (Chen et al., Citation2014). When people feel linked to others, they experience relatedness (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000).

Research on internal versus extrinsic motivation aimed to separate the concept of motivation, which is unitary in many theories and differs only in quantity but not type (Coxen et al., Citation2021). Intrinsic motivation—doing something because you want to—is the paradigm of autonomy and the growth tendency (Soon et al., Citation2022); while extrinsic motivation, on the other hand, refers to the idea that a behaviour is motivated by something other than its satisfaction (Vansteenkiste et al., Citation2020).

2.4. Enjoyment

People are more likely to use technology meaningfully if they perceive an activity requiring technology would be fun (Gerdenitsch et al., Citation2020). Enjoyment is “the degree to which one believes they are getting pleasure from using it as a factor in whether or not they intend to do so often” (Vallerand, Citation2000). The term refers to how individuals have a joyful experience when interacting with gamification’s dynamic and immersive nature (Dapica et al., Citation2022; Warmelink et al., Citation2020).

Researchers discovered that “the fun, pleasure, amusement, or playfulness received from using a technology” significantly impacted consumers’ adoption of technology (Nardini et al., Citation2019). In general, individuals will undertake tasks if they enjoy solving them. Solvers may be motivated by wanting to take up new or exciting lessons. Crowdsourced tasks can arouse interest and curiosity to explore new fields. The more enjoyment they perceive, the more likely they will participate in future crowdsourcing (Ye, Citation2017). Positive emotions encourage adaptable and innovative thinking, which helps increase work engagement, boost self-efficacy, and overcome adversity (Rodrigues et al., Citation2020).

2.5. Millennials toward the previous generation

Talent management requires engaged employees from the younger generation, such as millennials, to boost a company’s image and competitiveness, which is critical for growth and productivity (Cattermole, Citation2018; Gabriel et al., Citation2020; Hetland et al., Citation2018; O’Connor & Crowley-Henry, Citation2019). A study comparing the attitudes and behaviours of millennials and the previous generation (also known as Generation X) concerning work engagement found that they were significant across the board (Hassan et al., Citation2021; Park & Gursoy, Citation2012).

Competent workers from Millennials seek workplace freedom and flexibility (Hurtienne et al., Citation2021). They expect more from organizations, such as higher pay, perks, and opportunities (Sahni, Citation2021). Employers in organizations now have a diverse workforce that includes employees of various generations (King et al., Citation2017; Wood et al., Citation2020). Generation X has established itself within organizations, gaining higher-level positions and becoming a part of the organization (Çelik et al., Citation2021). However, millennials, who are still deciding on a professional route and lack a guaranteed career trajectory, will quickly join a firm with better potential and channels since they can afford to take the risk (Jung et al., Citation2021; Rissanen & Luoma-Aho, Citation2016).

2.6. Developing hypotheses

Work engagement, gamification affordance, basic need satisfaction, and enjoyment are all linked and can affect each other (da Silva et al., Citation2019; Suh & Wagner, Citation2017; Suh et al., Citation2017, Citation2018). This study explores the nature of these relationships and how they may affect employees in the workplace (Larson, Citation2019).

2.6.1. Relation of gamification affordance to basic need satisfaction, enjoyment, and work engagement

Motivational affordance in gamification refers to how a game or activity is designed to motivate players to engage (Perryer et al., Citation2016), which includes rewards, challenges, and a sense of progress or accomplishment (Zainuddin et al., Citation2019). The relationship between motivational affordance and basic psychological needs satisfaction is complex, as different people may find other things motivating and satisfying (Mitchell et al., Citation2020). However, giving participants a sense of autonomy, competence, and relatedness through a game or activity might satisfy their basic psychological requirements (Wee & Choong, Citation2019).

Gamification components like incentives, challenges, and feedback can motivate and engage people (Koivisto & Hamari, Citation2019). Enjoyment is the positive emotional response that a user experiences when participating in a task or activity (Hassan & Hamari, Citation2020). When gamification is implemented effectively, it can increase the motivational affordance of a task or activity, leading to increased enjoyment for the user (Liu et al., Citation2017). In other words, gamification can enhance the enjoyment of a task or activity by providing the user with engaging and motivating elements that encourage participation and engagement.

Gamification components like prizes, challenges, and progress tracking can drive people to participate and satisfy their basic needs for achievement, social connectivity, and autonomy, which makes the activity more enjoyable and satisfying (Suh et al., Citation2018). Competence, positive emotion, autonomy, self-regulated learning, and intrinsic motivation to learn all have a connection (Holzer et al., Citation2021). Gamification can change people’s attitudes and behaviours by satisfying their intrinsic needs (Treiblmaier & Putz, Citation2020; Van Roy & Zaman, Citation2019).

H1:

Gamification affordance has a positive effect on basic need satisfaction

H2:

Gamification affordance has a positive effect on enjoyment

H3:

Gamification affordance positively affects enjoyment through basic need satisfaction

2.6.2. Relation of basic need satisfaction to enjoyment and work engagement

When individuals feel that their basic needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence are being met, they are more likely to experience positive emotions and enjoy their work activities (Halvari et al., Citation2021). Managers play an essential role in assisting and promoting basic need satisfaction, which leads to greater quality motivation and performance. When workers believe their managers have their backs, they are more likely to be enthusiastic about their work, loyal to the company, and generally invested in its success. Employees are encouraged to “self-initiate” instead of being told what to do, and it is more important to listen to them than to try to control them.

Previous research has shown that satisfying one’s basic psychological needs is directly related to increased enjoyment in the workplace (Good et al., Citation2016). When individuals can fulfil their basic needs and experience enjoyment in their work, they are more likely to be motivated, engaged, and committed to their tasks, leading to higher levels of work engagement (Olafsen et al., Citation2021).

H4:

Basic need satisfaction has a positive effect on enjoyment

H5:

Basic need satisfaction positively affects work engagement through enjoyment

2.6.3. Relation of enjoyment to work engagement

When workers are invested in their jobs, they are more likely to develop innovative solutions to problems, take the initiative, and enjoy their work (Lai et al., Citation2020). Research shows that employee experience has the greatest impact on work engagement (Bartzik et al., Citation2021; Lemon, Citation2020). Employee experience is a potentially important pathway to practical and theoretical gains in people management (Cornelius et al., Citation2022). As mediated by employee experience, enjoyment is vital to work engagement (Rispler & Luria, Citation2021).

H6:

Enjoyment has a positive effect on work engagement

2.6.4. Relation of gamification affordance toward work engagement

Gamification affordance is the ability of a gamified system or activity to give a meaningful and engaging experience (Chanana & Sangeeta, Citation2020). Gamification affordance can satisfy basic psychological demands like autonomy, competence, and relatedness, which are vital for work engagement and enjoyment, another important aspect (Savignac, Citation2016).

Motivational affordances show that users’ interactions with gamification in online gamified communities are tied to their intrinsic needs. Immersion-related gamification alone satisfied autonomy demand, while achievement-related components predicted autonomy and competence (Xi & Hamari, Citation2019). Game artifacts as technological elements allow employees to experience game-like dynamics that make system usage fun, fascinating, and playful, leading to increased engagement (Bravo et al., Citation2021).

H7:

Gamification affordance positively affects work engagement through basic need satisfaction and enjoyment

H8:

Gamification affordance positively affects work engagement through enjoyment

3. Methodology

This research utilized scales derived from relevant literature reviews. Before distributing questionnaires, back translations of English literature reviews are performed. After examining potential translation issues, the Indonesian version was modified. Moderation eliminates significant back-translation disputes. Three individuals evaluate words and phrases based on responses, high content validity, and comprehension. Finally, a 30-person pilot test evaluates item dependability. All constructs have high Cronbach’s alpha coefficients.

3.1. Data samples

This study employs JM Co. as its research context; its core concept is to develop programs that engage employees with company programs and goals to prepare millennials to fill the company’s next leadership role. We exceeded De Vaus’s (Citation2014) sample size requirement of 114 samples for 800 application users among an 8,000 workforce population with 133 responses (Saunders et al., Citation2019).

The shortened work engagement scale (UWES-9) is altered from Schaufeli et al. (Citation2006). Gamification affordance scales by Suh et al. (Citation2017) cover each motivational affordance. Items for the basic psychological need satisfaction scale (BPNSS) are adapted from Van den Broeck et al. (Citation2010). Kim et al. (Citation2013) provided items for the enjoyment scale. All items are scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

3.2. Outliers testing

We then use IBM SPSS Statistics 26 to investigate univariate and multivariate descriptive statistics to identify outliers using Z-score and Mahalanobis distance. Statistics study uses Mahalanobis distances for multivariate outliers testing, requires a highly conservative outlier probability estimate, p = 0.001 for chi-square value, and potential outliers have standard Z-scores greater than 3.29 (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2019). ID119, ID125, and ID126 had Z-score values of −3.61, −5.02, and −3.58. Therefore, remove univariate outliers. ID tag 130 has a Mahalanobis distance of 22.81 and p = 0.0001, which is less than 0.001. Table summarizes demographic statistics with the remaining 129 respondents.

Table 1. Profile respondents

3.3. Testing assumptions

Many multivariate processes depend on assumptions (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2019); the fit between the data set and assumptions is evaluated using statistical and graphical measurements from SPSS software. The data is not regularly distributed since the unstandardized residual score is below 0.05. Most residuals above the zero line on a plot at projected values indicate nonlinearity. The remainder below the threshold at other projected values matched the linearity assumptions. Heteroscedasticity is linked to normalcy because variable interactions are homoscedastic when multivariate normality is satisfied, implying that the conditions are unmet. In the correlation matrix, multicollinearity and singularity are more likely when variables have a high correlation; however, if the correlation is 0.90 or higher, the assumptions are met. Thus, analyze the data nonparametrically.

3.4. Data analysis

The suggested framework’s validity and hypotheses are tested using partial least squares (PLS) structural equation modelling (SEM). PLS aids in assessing the reliability and validity of the construct measures employed in the investigation and determining the nature of the connections hypothesized in the study (Hair et al., Citation2018). PLS-SEM has been widely employed in various fields, including management, marketing, and social sciences (Hair et al., Citation2019). The current study aims to explore, forecast, and develop a new theory rather than test an already established hypothesis. PLS-SEM is a causal modelling technique that aims to maximize the variance explained by the dependent factors (Hair, Citation2020).

It outperforms CB-SEM regarding statistical power and is useful for predicting a target construct (Dash & Paul, Citation2021). To test for predictive relevance, PLS-SEM is employed as a dialogue between the investigator and the machine (Rick & Jasny, Citation2018). Gamification is a novel technology, and this study aims to investigate its impact on the workplace environment. The PLS-SEM technique was found to be appropriate and suited for data analysis.

4. Results and discussion

After a descriptive study, this part examines its composition and representativeness. Then, examine direct-effect components and intervening influences.

4.1. Descriptive analysis

The findings of the cleansing data collection, which were then processed, yielded an average value that may be used to offer an overview of the data acquired. The standard deviation, in combination with the mean, is a beneficial tool (Sekaran & Bougie, Citation2016).

The indicator with the highest mean in the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9) is WE6, equivalent to 4.605; this leads to the conclusion that employees said, “I feel happy when I am working intensely”, showing dedication to the company. Furthermore, the indicator with the lowest mean is WE3, which equals 4.426, that employees substantially dedicated by saying, “I am enthusiastic about my job”. The findings show that all respondents felt participating in a gamified HR system would eventually make them more vigorous, dedicated, and absorbed with the company program. Indicator GA4 has a mean value of 4.403; “compete with others” in the gamification platform could portray an employee’s status affordance. GA5 has the lowest mean of 4.171, while GA4 has the highest. It implies that the motivational affordance of achievement visibility in the forum could be improved. In the Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction Scale (BPNSS), the indicator with the highest mean is item BNS6, which equals 4.155. It concludes that the employees in the enterprise are expected to be independent, meaning that “I feel free to express my ideas and opinions”. In addition, the indicator with the lowest mean is item BNS9, which equals 3.597. It finds that employees need to relate, and when they apply gamification, they feel compelled to care about others. The indicator with the highest value, ENJ4, and the item with the lowest value, ENJ2, have respective values of 4.178 and 3.969, respectively. Indicator ENJ4 shows that respondents found it “interesting”, and ENJ2 shows that “exciting”. Although respondents experienced activities within the SLG system, the overall results show that the variable has respondents’ clarity of the questions.

4.2. Assessing outer model

The quality of the concept is examined in this study for measurement model based on the assessment of the testing assumptions is not fulfilled, continuing with a nonparametric test using SmartPLS 3 software.

Formative measurements and reflecting measurement model evaluations require understanding loadings. Analyzing a reflective measuring model begins with indicator loadings (Hair et al., Citation2017). Loadings greater than 0.708 are recommended since they signal that the construct explains more than half of the variation in the indicator (Hair et al., Citation2019), assuring good item dependability, as illustrated in Figure .

Statistical analyses of the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) indicate multicollinearity (Fornell & Bookstein, Citation1982). If the outer VIF score is less than 5, multicollinearity is not a significant problem (Hair et al., Citation2021). The phenomenon that arises when more than two indicators are involved is called multicollinearity (Khan et al., Citation2019). Before continuing to examine the outer model, any indication of outer VIF value above the threshold will be eliminated, which is fulfilled by the remaining indicators after removing several items (WE4, WE5, and WE8), as shown in Figure .

4.2.1. Construct reliability and validity

Cronbach’s Alpha and Composite Reliability (CR) establish internal consistency reliability. Composite dependability has the same cutoff as Cronbach’s alpha. Chin (Citation1998) recommends a CR of 0.70 or above for exploratory research (Henseler et al., Citation2016). Cronbach’s alpha tests convergent validity and dependability of latent variable indicators. More than 0.80 is a grand scale, while 0.70 is reasonable (Hair et al., Citation2019). Thus, construct reliability is established. Average Variance Extracted (AVE) measures how effectively the concept explains element variation. AVE can be used to measure the convergent validity of a notion. The notion accounts for at least half of its elements’ variation; hence, its AVE is 0.50 or above (Hair et al., Citation2017). When AVE exceeds 0.5, indicators converge to measure underlying variables (Henseler et al., Citation2015), establishing convergent validity as presented in Table .

Table 2. Construct validity and reliability

4.2.2. Discriminant validity

Construct’s discriminant validity measures how different it is from other constructs in the structural model in real life. Traditional metrics proposed by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) that the AVE of each construct be compared to the squared inter-construct correlation of the same build and all other reflectively measured constructs in the structural model. All model constructs’ combined variance should not exceed their AVEs, as shown in Table . Hence providing strong support for the establishment of discriminant validity. Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) is based on estimating the correlation between the constructs, as shown in Table . However, the threshold for HTMT has been debated in the existing literature. Henseler et al. (Citation2015) suggest a cutoff value of 0.90 or below for structural models with conceptually comparable variables (Hair et al., Citation2021). It is possible to determine whether or not a component of one build is overly dependent on its parent component by cross-loadings. It shows that all the items are higher on the underlying construct to which they belong than the other.

Table 3. Discriminant validity – Fornell & Larcker criterion

Table 4. Discriminant validity—HTMT

4.2.3. Model fit

With a low-correlation factor model, even though overall goodness-of-fit and approximation fit indicate whether data favour a factor model, they do not validate measurement quality. In this case, a factor model is unlikely to be rejected because the empirical and model-implied correlation matrices are consistent. The model fit was assessed using Standardized RMSR (Root Mean Square Residuals). The value of SRMR shown as 0.07 is depicted in the assessment, below the required value up to 0.08 (Dash & Paul, Citation2021), indicating a good model fit.

4.3. Common method bias

In the PLS-SEM context, common technique bias refers to a phenomenon induced by the measurement method utilized in SEM research rather than by the network of causes and effects in the model under investigation (Kock, Citation2015). For instance, the instructions at the beginning of a survey may steer responses from different respondents in the same direction, leading to overlapping indicators. Implicit social desirability linked with responding to questions in a specific way in a questionnaire is another potential cause of common method bias, leading the indicators to have similar variances.

Kock and Lynn (Citation2012) presented the complete collinearity test as a comprehensive method for assessing vertical and lateral collinearity. Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) are generated for all latent variables in a model, which is entirely automated by the PLS-SEM algorithm. This debate identifies a rise in the overall level of collinearity in a model as common method bias, which is equivalent to an increase in the whole collinearity VIFs for the latent variables in the model; thus, a VIF greater than 3.3 is recommended as a sign of pathological collinearity, as well as indicating a model may be tainted by common technique bias (Kock & Lynn, Citation2012). The comprehensive collinearity test identified common technique bias when a confirmation factor analysis failed, which is unsurprising. As a result, if all VIFs from a comprehensive collinearity test are equal to or less than 3.3, as shown in this study, WE = 1.49, GA = 2.09, BNS = 2.19, and ENJ = 2.31 thus, the model is free of common method bias.

4.4. Assessing inner model

The next stage in reviewing the structural model, PLS-SEM data, examines the structural model to see if the measurement model assessment is adequate. The coefficient of determination (R2), the blindfolding-based cross-validated redundancy measure Q2, and the statistical significance and relevance of the path coefficients should all be considered when evaluating the results, as shown in Figure .

The R2 value for the dependent variable determines the strength of each structural path; R2 should be equal to or greater than 0.1, with guidelines of 0.75 and 0.5 considered substantial and moderate, respectively, and 0.25 considered weak (Henseler, Citation2017). The results are in Table ; R2 values are over 0.25. Hence, the predictive capability is established. Researchers can also examine how removing a specific predictor construct impacts the R2 value of an endogenous construct. Foster Q2 establishes the predictive relevance of the endogenous constructs. Whereas Q2 above 0, the model has predictive relevance (Hair et al., Citation2019).

Table 5. R-square and Q-square

A careful examination of collinearity is necessary to ensure that the regression findings are not influenced. The inner VIF values are calculated using the latent variable scores of the predictor constructs in a partial regression. This approach is comparable to analyzing measurement models. Collinearity difficulties can emerge even with VIF values as low as 3–5 (Hair et al., Citation2019), which are symptomatic of possible concerns with predictor variable collinearity. As a rule of thumb, the inner VIF values should be no more than 3, as shown in Table .

Table 6. Inner VIF, F-square, and path coefficient

The results show significance in predicting the constructs by measuring the f2 effect size, which is slightly redundant to the path coefficient size. In the structural model, the rank order of the predictor constructs’ importance in explaining a dependent construct is frequently the same (Henseler et al., Citation2015). Both F Square values for GA toward BNS and BNS toward ENJ, having 1.432 and 0.431, respectively, show a large effect size in light of explaining partial mediation among millennials. In comparison, the other variable relationships show a medium effect size. According to Cohen (Citation1988), the f2 effect sizes of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 represent small, medium, and large effects (Sawilowsky, Citation2009). Removing the indicator from the model is significant (Gignac & Szodorai, Citation2016); the f2 effect size could explain the presence of mediation.

4.5. Multigroup analysis

SmartPLS 3 software was used for the multigroup analysis (MGA), which enabled the estimation of the coefficients of the two groups. As a result, they were used to find significant differences in the path linkages between millennials and generation-x (5000 subsamples, 2-tailed test, significant threshold of 0.05). As demonstrated in Table , there were no significant disparities for millennials toward generation-x in all variable direct and indirect correlations. Consistent with the parametric test, the Welch Satterthwaite results show insignificant path differences between variables.

Table 7. Multigroup test results

4.6. Hypothesis testing and discussion

The hypothesis testing results are shown in Table , which includes the effects, coefficient, standard deviation, t-statistics, p-values, and followed by the conclusion. Path Coefficient will characterize the contribution or impact between construct variables, as determined via bootstrapping. The bootstrapping of 5,000 samples method estimates the accuracy of nonparametric analysis for the outer and inner models. The statistical t-test value gives the significance value with a confidence level of 95%, greater than 1.96 for the t-test, with a p-value below 0.05.

Table 8. Hypothesis testing results

4.6.1. The effect of gamification affordance on basic need satisfaction

The results revealed that GA significantly impacts BNS (β = 0.767; t = 18.269; p = 0.000). Hence, H1 was supported. It shows that when gamification affordance increases, basic need satisfaction will increase by 76.7% for the millennials, whilst Gen-X had 72.4%. Higher t-values indicate large differences between sample sets. Smaller t-values indicate more sample set similarity. It also implies that employees use the program because they want to be seen in a gamified SL and compete with others. A recent study found various game design and interface features that improve basic psychological needs (Xi & Hamari, Citation2019). The identified game design features were beneficial in addressing need satisfaction (Bitrián et al., Citation2021). Gamification—the use of game design elements in nongaming environments—aims to improve task performance and need satisfaction, according to a study (Sailer et al., Citation2017).

4.6.2. The effect of gamification affordance on enjoyment

The results revealed that GA significantly impacts ENJ (β = 0.331; t = 3.099; p = 0.002). Hence, H2 was supported. It shows that enjoyment will increase by 33.1% when gamification affordance increases. Despite having the lowest mean in both variables, it is brave to assert that the question materials in gamified SL based on learning needs exhibiting the importance of engaging in customizing corresponds with millennials’ imaginations. Gamification has shown promising potential to increase individuals’ internally driven behaviours and positively impact their attitudes and behaviours. Few studies exist that empirically test the effectiveness of gamification applications in a controlled experimental setting (Treiblmaier & Putz, Citation2020), showing a result of a more substantial influence of perceived from within, as measured by enjoyment and curiosity, on attitude and behavioural intention (Zhang et al., Citation2020).

4.6.3. The effect of gamification affordance on enjoyment through basic need satisfaction

The results revealed that GA significantly indirectly affects ENJ (β = 0.428; t = 4.939; p = 0.000). Hence, H3 was supported. It shows partial mediation when both direct and indirect effects are significant. Also, the direct impact is substantial in that the p-value is below 0.05. Hence, a portion of the impact of gamification affordance on enjoyment is mediated by basic need satisfaction. Gamification affordance pleasures basic needs. Gamified SLs make e-learning entertaining when responders are satisfied. Well-designed rankings may help. This study indicates that several game design elements promote real need fulfilment in the experimental situation (Sailer et al., Citation2017; Wee & Choong, Citation2019).

4.6.4. The effect of basic need satisfaction on enjoyment

The findings demonstrated that BNS substantially influences ENJ (β = 0.558; t = 5.049; p = 0.000). Hence, H4 was supported. It indicates that an increase in basic need satisfaction would, in turn, result in a 55.8% rise in enjoyment. When participants are free to play a nongame learning context in the gamified system, it gives them the idea that the e-learning system atmosphere is fun. The empirical findings show that need satisfaction had a positive effect on enjoyment. Despite the widespread use of gamification in the workplace, little is known about the contextual aspects that influence its effectiveness (Mitchell et al., Citation2020). The activities implemented in the company produce varied motivational affordances such as rewards, competitiveness, and self-expression. Management could be depicted in how extrinsic incentives, such as social pressure or internalized guilt, affect employees’ needs satisfaction (Hussein et al., Citation2021).

4.6.5. The effect of basic need satisfaction on work engagement through enjoyment

The results revealed that BNS significantly indirectly affects WE (β = 0.278; t = 3.498; p = 0.000). Hence, H5 was supported. The essential need satisfaction increases engagement in the content on tourism and hospitality review sites; thus, when the study looked into what motivates people to post on these networks, it was discovered that enjoyment could positively moderate that phenomenon (Bravo et al., Citation2021). Enjoyment mediates need fulfilment and employee engagement, while e-learning systems encourage creativity, and psychological need satisfaction influences autonomy motivation, which predicts exercise participation (Rhodes et al., Citation2021).

4.6.6. The effect of enjoyment on work engagement

The results revealed that ENJ significantly impacts WE (β = 0.499; t = 4.548; p = 0.000). Hence, H6 was supported. It shows that work engagement will increase by 49.9% when enjoyment increases. When employment in the JM Click system piques the interest of each respondent while they are at work, they will concentrate an incredible amount of attention on their task. As few studies cover research gaps concerning the antecedents and effects of enjoyment toward engagement (Dewaele & Li, Citation2021; Mouatt et al., Citation2020), employers can use employee experience to improve employee behaviour.

4.6.7. The effect of gamification affordance on work engagement through basic need satisfaction and enjoyment

The results revealed that GA significantly indirectly affects WE (β = 0.214; t = 3.396; p = 0.001). Hence, H7 was supported. A theoretical model draws on cognitive evaluation theory to describe the impacts of enjoyment on user engagement and evaluate it using data gathered from users of a gamified information system. Gamification should do more than just provide pleasure and fun; it should produce varied game dynamics and motivational affordances (Lee, Citation2019). Worker satisfaction and enjoyment mediate gamification’s impact on engagement. As gamified SL rewards participation with points, skill, and work attention may counteract these traits.

4.6.8. The effect of gamification affordance on work engagement through enjoyment

The results revealed that GA significantly indirectly affects WE (β = 0.165; t = 2.275; p = 0.023). Hence, H8 was supported. Given that gamification has no direct effects, the influence on work engagement must be mediated via enjoyment. Using the nongame learning context system as a fun activity is rewarded with points in gamification, which encourages the participants to engage while having fun. Thus, nongame context activities in the workplace help HR promote gamified designs with satisfaction and enjoyment, which boosts employee engagement. It also shows how employee performance and experience affect job happiness (Aydınlıyurt et al., Citation2021). Nonetheless, some data suggests that gamification has undeniably adverse effects (Hammedi et al., Citation2020).

5. Conclusion

Work engagement is defined as being completely absorbed and enthusiastic about one’s work; research has shown that work engagement improves job performance, job satisfaction, and organizational success (Busque-Carrier et al., Citation2021; Carter et al., Citation2016).

Several inferences can be reached based on the findings provided. Firstly, affordances in gamification, such as rewards, self-expression, status, competition, and visibility of achievement, can be practical tools for enhancing work engagement. Secondly, the effect of gamification affordance on work engagement is likely to be mediated by the satisfaction of basic psychological needs, such as autonomy, competence, and relatedness; thus, incorporating elements that support these needs can help create a more enjoyable and engaging work environment. Thirdly, the multigroup analysis results from findings indicate no significant differences in the effects of gamification on work engagement between millennials and previous generations; thus, gamification affordance can be an effective tool for enhancing work engagement among workforces of different ages and generations.

Millennials value work-life balance, career advancement opportunities, and a sense of purpose in their work (Good et al., Citation2016); as they are expected to make up most of the workforce in the coming years. Thus, understanding their attitudes toward work engagement can assist businesses in developing a more engaged and productive workforce. Finally, these findings highlight the potential value of gamification as a tool for improving work engagement, implying that it is valuable for addressing the low levels of work engagement.

5.1. Theoretical contribution

Despite their unique viewpoints and expectations, millennials hope to be treated with more deference in the workplace. As previous studies in the context of a holistic approach have shown (Schöbel et al., Citation2020), gamification can be an effective tool for engaging and motivating employees, particularly younger employees who may be more accustomed to and receptive to game-like elements in the workplace. Gamification can be a helpful tool for improving work engagement and productivity in a state-owned enterprise, a type of organization that may face challenges in terms of employee engagement and motivation. Gamification can create a more fulfilling and engaging work environment by satisfying basic psychological needs such as autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Rahmadani et al., Citation2019). By incorporating a gamified system environment (Riar et al., Citation2022), a dynamic and engaging work environment boosts employee enjoyment and work engagement.

5.2. Managerial implication

Human resource directors must finally acknowledge the hurdles of building an effective employee engagement plan for this much-maligned cohort of employees (Cattermole, Citation2018). Simultaneously, we know that managers frequently describe difficulties in engaging these young professionals in a way that channels their enthusiasm into effective organizational development. Regarding the employee’s actual work output, it might help if managers gave out more regular rewards, sought employee feedback, and laid out specific objectives (Iqbal et al., Citation2019; Ismail et al., Citation2019; Liu et al., Citation2018).

Gamification can be an effective method for increasing millennial employee engagement and productivity (Bizzi, Citation2023). Managers can create a more dynamic and engaging workplace by introducing game-like features and mechanics (Patricio et al., Citation2022). Managers should address basic psychological needs and incorporate elements that promote autonomy, competence, and relatedness to enhance enjoyment and interest in job activities.

5.3. Limitations and future research

In addressing the scope and objectives of this study, it is crucial to acknowledge the limitations posed by the data’s homogeneity and the sample’s specificity. Despite the relatively small sample size and inherent limitations, it is essential to emphasise that our primary objective is to investigate the context of a specific company. Thus, we hope to provide unique and valuable insights that can serve as a basis for future research in similar organisational settings.

This study serves as a beginning point for understanding the possible benefits of workplace gamification. However, much is still to be learned about how gamification affects employee work engagement and other outcomes. Factors such as sample size and the exact metrics and methodologies employed to analyse the effects of gamification on work engagement hampered the study. Thus, future research could investigate the effects of gamification on other outcomes, such as job satisfaction or organizational loyalty, as well as on workers of various ages and generations.

Author.docx

Download MS Word (26.3 KB)Supplementary.docx

Download MS Word (42.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2287586

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gunawan Wibisono

Gunawan Wibisono is a doctoral student at Brawijaya University in Indonesia. Currently working as a full-time airline captain, experienced trainer, and active member of an education foundation serving remote Indonesian communities. His research interests include gamification, employee engagement, and supply chain management.

Yuli Setiawan

Yuli Setiawan is in his first year of a doctoral program in research management at Bina Nusantara University in Jakarta, Indonesia.

Budi Aprianda

Budi Aprianda teaches at Pamulang University in Tangerang, Indonesia. Marketing and human capital development are his most important research areas.

Wiputra Cendana

Wiputra Cendana is an independent researcher and lecturer at Pelita Harapan University in Karawaci, Indonesia.

References

- Adie, J. W., Duda, J. L., & Ntoumanis, N. (2008). Autonomy support, basic need satisfaction and the optimal functioning of adult male and female sport participants: A test of basic needs theory. Motivation and Emotion, 32(3), 189–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-008-9095-z

- Aydınlıyurt, E. T., Taşkın, N., Scahill, S., & Toker, A. (2021). Continuance intention in gamified mobile applications: A study of behavioral inhibition and activation systems. International Journal of Information Management, 61(102414), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102414

- Baard, P. P., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2004). Intrinsic need satisfaction: A motivational basis of performance and weil-being in two work settings 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(10), 2045–2068. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02690.x

- Bakker, A. B., Albrecht, S. L., & Leiter, M. P. (2011). Key questions regarding work engagement. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 20(1), 4–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2010.485352

- Bakker, A. B., & Leiter, M. P. (Eds.). (2010). Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research (1st ed.). Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203853047

- Barreiro, C. A., & Treglown, L. (2020). What makes an engaged employee? A facet-level approach to trait emotional intelligence as a predictor of employee engagement. Personality and Individual Differences, 159(109892), 109892–109898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.109892

- Bartzik, M., Bentrup, A., Hill, S., Bley, M., von Hirschhausen, E., Krause, G., Ahaus, P., Dahl-Dichmann, A., & Peifer, C. (2021). Care for joy: Evaluation of a humor intervention and its effects on stress, flow experience, work enjoyment, and meaningfulness of work. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.667821

- Benitez, J., Ruiz, L., & Popovic, A. (2022). Impact of mobile technology-enabled HR gamification on employee performance: An empirical investigation. Information & Management, 59(4), 103647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2022.103647

- Bitrián, P., Buil, I., & Catalán, S. (2021, July). Enhancing user engagement: The role of gamification in mobile apps. Journal of Business Research, 132, 170–185. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.028

- Bizzi, L. (2023). Why to gamify performance management? Consequences of user engagement in gamification. Information & Management, 60(3), 103762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2023.103762

- Bravo, R., Catalán, S., & Pina, J. M. (2021). Gamification in tourism and hospitality review platforms: How to R.A.M.P. up users’ motivation to create content. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 99(103064), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.103064

- Busque-Carrier, M., Ratelle, C. F., & Le Corff, Y. (2021). Work values and job satisfaction: The mediating role of basic psychological needs at work. Journal of Career Development, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/08948453211043878

- Cardador, M. T., Northcraft, G. B., & Whicker, J. (2017). A theory of work gamification: Something old, something new, something borrowed, something cool? Human Resource Management Review, 27(2), 353–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2016.09.014

- Carter, W. R., Nesbit, P. L., Badham, R. J., Parker, S. K., & Sung, L.-K. (2016). The effects of employee engagement and self-efficacy on job performance: A longitudinal field study. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(17), 2483–2502. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1244096

- Cattermole, G. (2018). Creating an employee engagement strategy for millennials. Strategic HR Review, 17(6), 290–294. https://doi.org/10.1108/SHR-07-2018-0059

- Çelik, A. A., Kılıç, M., Altındağ, E., Öngel, V., & Günsel, A. (2021). Does the Reflection of Foci of commitment in job performance weaken as generations get younger? A comparison between Gen X and Gen Y employees. Sustainability, 13(16), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169271

- Chanana, N., & Sangeeta S. (2020). Employee engagement practices during COVID‐19 lockdown. Journal of Public Affairs, 21(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2508

- Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E. L., Van der Kaap-Deeder, J., Duriez, B., Lens, W., Matos, L., Mouratidis, A., Ryan, R. M., Sheldon, K. M., Soenens, B., Van Petegem, S., & Verstuyf, J. (2014). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and Emotion, 39(2), 216–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-014-9450-1

- Chin, W. W. (1998). Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Quarterly, 22(1), vii–xvi.

- Christian, M. S., Garza, A. S., & Slaughter, J. E. (2011). Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Personnel Psychology, 64(1), 89–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01203.x

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

- Cornelius, N., Ozturk, M. B., & Pezet, E. (2022). Editorial: The experience of work and experiential workers: Mainline and critical perspectives on employee experience. Personnel Review, 51(2), 433–443. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-03-2022-887

- Coxen, L., van der Vaart, L., Van den Broeck, A., & Rothmann, S. (2021). Basic psychological needs in the work context: A systematic literature review of diary studies. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(October), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.698526

- Dapica, R., Hernández, A., & Peinado, F. (2022). Who trains the trainers? Gamification of flight instructor learning in evidence-based training scenarios. Entertainment Computing, 43(June), 100510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.entcom.2022.100510

- Dash, G., & Paul, J. (2021). CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173(August), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121092

- da Silva, L. F. S., Verschoore, J. R., Bortolaso, I. V., & Brambilla, F. R. (2019). The effectiveness of game dynamics in cooperation networks. European Business Review, 31(6), 870–884. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-06-2018-0118

- Davies, G., Mete, M., & Whelan, S. (2018). When employer brand image aids employee satisfaction and engagement. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People & Performance, 5(1), 64–80. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-03-2017-0028

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1980). Self-determination theory: When mind mediates Behavior. The Journal of Mind and Behavior, 1(1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.2307/43852807

- Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Gagné, M., Leone, D. R., Usunov, J., & Kornazheva, B. P. (2001). Need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in the work organizations of a former eastern bloc country: A cross-cultural study of self-determination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(8), 930–942. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167201278002

- De Clerck, T., Willem, A., De Cocker, K., & Haerens, L. (2022). Toward a refined insight into the importance of volunteers’ motivations for need-based experiences, job satisfaction, work effort, and turnover intentions in nonprofit sports clubs: A person-centered approach. Voluntas, International Society for Third-Sector Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-021-00444-5

- Deterding, S. (2019). Gamification in Management: Between choice architecture and humanistic design. Journal of Management Inquiry, 28(2), 131–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492618790912

- Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011). From game design elements to Gamefulness: Defining “gamification.” Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference on Envisioning Future Media Environments - MindTrek, (Vol. 11, pp. 9–15). https://doi.org/10.1145/2181037.2181040

- De Vaus, D.(2014). Surveys in social research (6th ed.). Routledge.

- Dewaele, J.-M., & Li, C. (2021). Teacher enthusiasm and students’ social-behavioral learning engagement: The mediating role of student enjoyment and boredom in Chinese EFL classes. Language Teaching Research, 25(6), 922–945. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211014538

- Eldor, L. (2016). Work engagement: Toward a general theoretical enriching model. Human Resource Development Review, 15(3), 317–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484316655666

- Feng, Y., Jonathan Ye, H., Yu, Y., Yang, C., & Cui, T. (2018). Gamification artifacts and crowdsourcing participation: Examining the mediating role of intrinsic motivations. Computers in Human Behavior, 81, 124–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.12.018

- Florenthal, B., & Awad, M. (2021). A cross-cultural comparison of millennials’ engagement with and donation to nonprofits: A hybrid U&G and TAM framework. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 18(4), 629–657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-021-00292-5

- Fornell, C., & Bookstein, F. L. (1982). Two structural equation models: LISREL and PLS applied to consumer exit-voice theory. Journal of Marketing Research, 19(4), 440–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378201900406

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

- Frondozo, C. E., King, R. B., Nalipay, M. J. N., & Mordeno, I. G. (2020). Mindsets matter for teachers, too: Growth mindset about teaching ability predicts teachers’ enjoyment and engagement. Current Psychology, 41(8), 5030–5033. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01008-4

- Gabriel, A. G., Alcantara, G. M., & Alvarez, J. D. G. (2020). How do millennial Managers lead older employees? The Philippine workplace experience. SAGE Open, 10(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020914651

- Gallup. (2022). State of the global workplace 2022 report: The voice of the world’s employees. Employee Engagement Insights for Business Leaders Worldwide. https://www.gallup.com/workplace/349484/state-of-the-global-workplace.aspx

- García-Jurado, A., Castro-González, P., Torres-Jiménez, M., & Leal-Rodríguez, A. L. (2019). Evaluating the role of gamification and flow in e-consumers: Millennials versus generation X. Kybernetes, 48(6), 1278–1300. https://doi.org/10.1108/K-07-2018-0350

- Gerdenitsch, C., Sellitsch, D., Besser, M., Burger, S., Stegmann, C., Tscheligi, M., & Kriglstein, S. (2020). Work gamification: Effects on enjoyment, productivity and the role of leadership. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 43(July), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2020.100994

- Gignac, G. E., & Szodorai, E. T. (2016). Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 74–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.069

- Gillet, N., Fouquereau, E., Vallerand, R. J., Abraham, J., & Colombat, P. (2018). The role of workers’ motivational profiles in affective and Organizational factors. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(4), 1151–1174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9867-9

- Golrang, H., & Safari, E. (2021). Applying gamification design to a donation-based crowdfunding platform for improving user engagement. Entertainment Computing, 38(March), 100425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.entcom.2021.100425

- Good, D. J., Lyddy, C. J., Glomb, T. M., Bono, J. E., Brown, K. W., Duffy, M. K., Baer, R. A., Brewer, J. A., & Lazar, S. W. (2016). Contemplating mindfulness at work. Journal of Management, 42(1), 114–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315617003

- Gündüz, A. Y., & Akkoyunlu, B. (2020). Effectiveness of gamification in flipped learning. SAGE Open, 10(4), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020979837

- Gupta, A., & Singh, P. (2021). Job crafting, workplace civility and work outcomes: The mediating role of work engagement. Global Knowledge, Memory & Communication, 70(6/7), 637–654. https://doi.org/10.1108/GKMC-09-2020-0140

- Gustomo, A., Febriansyah, H., Ginting, H., & Santoso, I. M. (2019). Understanding narrative effects. Journal of Workplace Learning, 31(2), 166–191. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWL-07-2018-0088

- Hair, J. F., Jr. (2020). Next-generation prediction metrics for composite-based PLS-SEM. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 121(1), 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-08-2020-0505

- Hair, J., Hollingsworth, C. L., Randolph, A. B., & Chong, A. Y. L. (2017). An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 117(3), 442–458. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-04-2016-0130

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R. In Springer. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2018). Rethinking some of the rethinking of partial least squares. European Journal of Marketing, 53(4), 566–584. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-10-2018-0665

- Halvari, A. E. M., Ivarsson, A., Halvari, H., Olafsen, A. H., Solstad, B., Niemiec, C. P., Deci, E. L., & Williams, G. (2021). A prospective study of knowledge sharing at work based on self-determination theory. Scandinavian Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 6(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.16993/sjwop.140

- Hammedi, W., Leclercq, T., Poncin, I., & Alkire, L. (Née Nasr). (2020). Uncovering the dark side of gamification at work: Impacts on engagement and well-being. Journal of Business Research, 122(August), 256–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.08.032

- Hassan, L., & Hamari, J. (2020). Gameful civic engagement: A review of the literature on gamification of e-participation. Government Information Quarterly, 37(3), 101461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2020.101461

- Hassan, M. M., Jambulingam, M., Narayan, E. A., Islam, S. N., & Zaman, A. U. (2021). Retention approaches of millennial at Private sector: Mediating role of Job Embeddedness. Global Business Review, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150920932288

- Henseler, J. (2017). Bridging design and behavioral research with variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of Advertising, 46(1), 178–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2017.1281780

- Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(1), 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hetland, J., Hetland, H., Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2018). Daily transformational leadership and employee job crafting: The role of promotion focus. European Management Journal, 36(6), 746–756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2018.01.002

- Holzer, J., Lüftenegger, M., Korlat, S., Pelikan, E., Salmela-Aro, K., Spiel, C., & Schober, B. (2021). Higher Education in times of COVID-19: University students’ basic need satisfaction, self-regulated learning, and well-being. AERA Open, 7(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/23328584211003164

- Hui, L., Qun, W., Nazir, S., Mengyu, Z., Asadullah, M. A., & Khadim, S. (2021). Organizational identification perceptions and millennials’ creativity: Testing the mediating role of work engagement and the moderating role of work values. European Journal of Innovation Management, 24(5), 1653–1678. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-04-2020-0165

- Huotari, K., & Hamari, J. (2017). A definition for gamification: Anchoring gamification in the service marketing literature. Electronic Markets, 27(1), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-015-0212-z

- Hurtienne, M. W., Hurtienne, L. E., & Kempen, M. (2021). Employee engagement: Emerging insight of the millennial manufacturing workforce. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 33(2), 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21453

- Hussein, R. S., Mohamed, H., & Kais, A. (2021). Antecedents of level of social media use: Exploring the mediating effect of usefulness, attitude and satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Communications, 28(7), 703–724. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2021.1936125

- Iqbal, A., Latif, F., Marimon, F., Sahibzada, U. F., & Hussain, S. (2019). From knowledge management to organizational performance. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 32(1), 36–59. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-04-2018-0083

- Ismail, H. N., Iqbal, A., & Nasr, L. (2019). Employee engagement and job performance in Lebanon: The mediating role of creativity. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 68(3), 506–523. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-02-2018-0052

- Jaillet, P., Loke, G. G., & Sim, M. (2022). Strategic workforce planning under uncertainty. Operations Research, 70(2), 1042–1065. https://doi.org/10.1287/opre.2021.2183

- Jain, A., & Dutta, D. (2019). Millennials and gamification: Guerilla tactics for making learning fun. South Asian Journal of Human Resources Management, 6(1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/2322093718796303

- Jung, H. S., Jung, Y. S., & Yoon, H. H. (2021). COVID-19: The effects of job insecurity on the job engagement and turnover intent of deluxe hotel employees and the moderating role of generational characteristics. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 92(June), 102703–102709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102703

- Kang, H. J. (Annette), & Busser, J. A. (2018, May). Impact of service climate and psychological capital on employee engagement: The role of organizational hierarchy. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 75, 1–9. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.03.003

- Khan, G. F., Sarstedt, M., Shiau, W.-L., Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Fritze, M. P. (2019). Methodological research on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Internet Research, 29(3), 407–429. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-12-2017-0509

- Kim, H., Suh, K. S., & Lee, U. K. (2013). Effects of collaborative online shopping on shopping experience through social and relational perspectives. Information & Management, 50(4), 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2013.02.003

- King, C., Murillo, E., & Lee, H. (2017). The effects of generational work values on employee brand attitude and behavior: A multi-group analysis. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 66, 92–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.07.006

- Kniffin, K. M., Narayanan, J., Anseel, F., Antonakis, J., Ashford, S. P., Bakker, A. B., Bamberger, P., Bapuji, H., Bhave, D. P., Choi, V. K., Creary, S. J., Demerouti, E., Flynn, F. J., Gelfand, M. J., Greer, L. L., Johns, G., Kesebir, S., Klein, P. G., Lee, S. Y., & van Vugt, M. (2021). COVID-19 and the workplace: Implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. The American Psychologist, 76(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000716

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM. International Journal of E-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101

- Kock, N., & Lynn, G. (2012). Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 13(7), 546–580. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00302

- Koivisto, J., & Hamari, J. (2019). The rise of motivational information systems: A review of gamification research. International Journal of Information Management, 45(June), 191–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.10.013

- Kwon, K., & Kim, T. (2020). An integrative literature review of employee engagement and innovative behavior: Revisiting the JD-R model. Human Resource Management Review, 30(2), 100704–100718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.100704

- Kwon, K., & Park, J. (2019). The life cycle of employee engagement theory in HRD research. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 21(3), 352–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422319851443

- Lai, F.-Y., Tang, H.-C., Lu, S.-C., Lee, Y.-C., & Lin, C.-C. (2020). Transformational leadership and job performance: The mediating role of work engagement. SAGE Open, 10(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019899085

- Larasati, D. P., Hasanati, N., & Istiqomah. (2019). The effects of work-life balance towards employee engagement in millennial generation. Proceedings of the 4th ASEAN Conference on Psychology, Counselling, and Humanities (ACPCH 2018), 304, 390–394. (Acpch 2018). https://doi.org/10.2991/acpch-18.2019.93

- Larson, K. (2019). Serious Games and gamification in the corporate training environment: A literature Review. TECHTRENDS TECH TRENDS, 64(2), 319–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-019-00446-7

- Lee, B. C. (2019). The effect of gamification on psychological and behavioral outcomes: Implications for cruise tourism destinations. Sustainability, 11(11), 3002–3015. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113002

- Lemon, L. L. (2020). The employee experience: How employees make meaning of employee engagement. Journal of Public Relations Research, 31(5–6), 176–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/1062726X.2019.1704288

- Li, Y., Liu, Z., Lan, J., Ji, M., Li, Y., Yang, S., & You, X. (2021). The influence of self-efficacy on human error in airline pilots: The mediating effect of work engagement and the moderating effect of flight experience. Current Psychology, 40(1), 81–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9996-2

- Li, C., Naz, S., Khan, M. A. S., Kusi, B., & Murad, M. (2019). An empirical investigation on the relationship between a high-performance work system and employee performance: Measuring a mediation model through partial least squares–structural equation modeling. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 12, 397–416. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S195533

- Liu, M., Huang, Y., & Zhang, D. (2018). Gamification’s impact on manufacturing: Enhancing job motivation, satisfaction and operational performance with smartphone-based gamified job design. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing, 28(1), 38–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/hfm.20723

- Liu, D., Santhanam, R., & Webster, J. (2017). Toward meaningful engagement: A framework for design and research of gamified Information Systems. MIS Quarterly, 41(4), 1011–1034. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2017/41.4.01

- Mantouka, E. G., Barmpounakis, E. N., Milioti, C. P., & Vlahogianni, E. I. (2019). Gamification in mobile applications: The case of airports. Journal of Intelligent Transportation Systems: Technology, Planning, and Operations, 23(5), 417–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/15472450.2018.1473157

- Men, L. R., O’Neil, J., & Ewing, M. (2020). Examining the effects of internal social media usage on employee engagement. Public Relations Review, 46(2), 101880–101889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2020.101880

- Mitchell, R., Schuster, L., & Jin, H. S. (2020). Gamification and the impact of extrinsic motivation on needs satisfaction: Making work fun? Journal of Business Research, 106(November), 323–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.11.022