?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Research on consumer food value preferences has typically focused on consumers in the developed economy, with knowledge regarding food value preferences in emerging food markets being a grey spot. This study aims to fill this gap in the literature. Accordingly, the possible existence of consumer clusters in Kenya based on their appreciation of food values is analyzed. The differences in the appreciation of food values were studied considering the socio-demographic traits of 500 random consumers, for which a standardized questionnaire was used. In the empirical analysis, Spearman’s correlation test, two-step cluster analyses and logistic regressions were calculated. The results reveal variations in food value preferences between segments determined by economic and socio-environmental factors. Nutrition was the most preferred value, while environmental impact was the least preferred.

1. Introduction

The decisions consumers make regarding food are far from simple, being shaped by a complex interplay of factors (Wansink & Sobal, Citation2007; Jaeger et al., Citation2011; Vabø & Hansen, Citation2014; M; Martinez-Ruiz & Gomez-Canto, Citation2016; Bogue & Yu, Citation2016). Understanding why people choose one food over another and how these choices can be influenced is an intriguing topic (Carroll & Vallen, Citation2014; Grunert, Citation2002; Lusk & Briggeman, Citation2009; Martinez-Ruiz & Gomez-Canto, Citation2016). While food is undeniably essential for human well-being, its significance varies between individuals, reflecting their unique values and preferences. These values extend beyond personal choices and hold a pivotal place in public policy, marketing strategies and both business and the public sector (Anderson & Wynstra, Citation2005; Lindgreen & Wynstra, Citation2005; Porter & Kramer, Citation2011).

However, recent research has raised questions about the alignment of traditional product-centered values in the food industry with those cherished by consumers (Gallarza et al., Citation2011; Graf & Maas, Citation2008; McFarlane, Citation2013; Sanchez-Fernandez & Iniesta-Bonillo, Citation2007). Notably, Lusk and Briggeman (Citation2009) explored the interplay between food values and broader consumer values. Since 2009, studies have revealed that consumers prioritize different values when making food choices; some emphasize well-being and safety, while others focus on price, appearance, or the environmental impact of their food (see Lusk & Briggeman, Citation2009 on USA; Bazzani et al., Citation2018, on Norway and; Izquierdo-Yusta et al., Citation2019, on Spanish consumers). These values also influence consumer satisfaction, loyalty, and post-purchase behavior across diverse food outlets (Izquierdo-Yusta et al., Citation2020; Pérez-Villarreal et al., Citation2020). Nevertheless, most of this research has concentrated on developed economies, leaving a significant knowledge gap regarding emerging markets and the socio-demographic factors affecting food value preferences (Femi-Oladunni et al., Citation2021).

It is worth noting that while Femi-Oladunni et al. (Citation2023) and Antwi and Matsui (Citation2018) have made notable contributions by delving into food values within the context of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), there are still substantial knowledge gaps to be addressed. These studies, although valuable, primarily focused on identifying the most preferred food values among consumers. The broader socio-environmental factors that may influence individuals’ preferences regarding food values have yet to be thoroughly explored. Additionally, Antwi and Matsui’s (Antwi & Matsui, Citation2018) research had certain limitations, primarily focusing on the local food market, without considering the influence of different types of food markets. Moreover, their study failed to delve into ethnic differences, a critical aspect of consumption and behavior in any region. These limitations leave questions unanswered about the extent to which various socio-environmental factors impact the decision-making process of consumers in SSA. In contrast, Bazzani et al. (Citation2018) took a more comprehensive approach by examining the socio-environmental factors influencing American and Norwegian consumers. Their findings indicated a consistent preference for the safety value across different sociodemographic and environmental factors in these developed economies. However, it remains uncertain whether this preference would hold in the context of an emerging economy like Kenya, where unique sociodemographic and economic dynamics are at play.

Therefore, there is still a substantial gap in understanding how socio-environmental factors influence food value preferences in emerging economies like Nairobi, Kenya, and whether these preferences align with those observed in developed economies. Closing this knowledge gap is crucial for gaining insights into consumer behavior and informing targeted strategies in these emerging markets. To address this gap, our study focuses on the unique economic landscape described by Kenyan Wall Street (Citation2021), showcasing Kenya as one of the fastest-growing economies within sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Despite being categorized as a lower-middle-income country by the World Bank, Kenya serves as a pertinent illustration of a nation grappling with significant income disparities and poverty challenges, representative of the lowest-income populations globally.

What makes Kenya particularly intriguing for our research is its intricate interplay of social and economic factors, which can significantly influence consumer preferences. Notably, over a third of Kenya’s population lives below the international poverty line, underscoring the pervasive income inequality prevalent in the region (World Bank, Citation2018). Disturbingly, statistics from the World Food Programme in 2018 reveal that one in four children in Kenya has stunted growth due to malnutrition. Additionally, a staggering 80% of Kenya’s populace is under the age of 35, and a substantial 35% of working-age Kenyans find themselves unemployed (World Food Programme, Citation2018). Furthermore, according to the World Food Programme’s data, a considerable segment of Kenya’s population, including approximately 500,000 refugees, relied on food aid in the years leading up to 2018. Regrettably, this situation has seen no significant improvement and has possibly worsened, as indicated by the World Food Programme’s (Citation2021) report. Given this challenging backdrop, it becomes increasingly compelling to delve into the sociodemographic factors that play a pivotal role in shaping consumer clusters based on their preferences regarding food values. In a region marked by such complexity and socioeconomic disparities, understanding the dynamics of consumer behavior and their alignment with food values becomes not only academically intriguing but also essential for informing effective strategies that cater to the needs and preferences of this unique market.

This article contributes significantly to the existing body of literature by concentrating on the population of Nairobi, Kenya and the underlying principles guiding their choices in food purchases. Building upon the foundational concept of the food value framework initially established by Lusk and Briggeman in 2009, this study undertakes a comprehensive analysis of the sociodemographic factors characterizing consumers in Nairobi. It seeks to unravel the intricate web of determinants that influence their preferences concerning the values they attach to food.

In line with the methodology employed by Femi-Oladunni et al. in their 2023 study on Nigerian consumers, our approach departs from the conventional taxonomy of food values prevalent in the literature (as exemplified by Antwi & Matsui, Citation2018; Bazzani et al., Citation2018; Izquierdo-Yusta et al., Citation2020; Lister et al., Citation2014; Lusk & Briggeman, Citation2009). This paper, instead, embraces a more nuanced and region-specific identification of these values. Furthermore, it extends beyond mere value identification, delving into the sociodemographic factors that potentially shape consumers’ appreciation of these food values. This article considers variables such as consumers’ estimated monthly income, age, gender, level of education, preferred food market type (e.g., local markets, formal supermarkets, online food markets), and ethnicity.

The outcome of this study offers robust evidence supporting the connection between socioeconomic factors and consumers’ preferences in food values, particularly within the context of an emerging market. This article serves to advance the understanding of the characteristics of food values that hold the most sway over consumer choices in this geographical region, an area hitherto underexplored in academic research (as highlighted by Femi-Oladunni et al., Citation2021). Crucially, the findings lend credence to the hypothesis that sociodemographic and economic factors wield substantial influence over consumers’ decisions in the realm of food choices, aligning with previous research conducted by Fitzgerald et al. (Citation2010).

In practical terms, the insights gleaned from this study hold significant implications for food policymakers, producers, and marketers alike. Our research can serve as a compass, guiding strategic decisions related to product labeling, market positioning, consumer targeting, and the enhancement of consumer satisfaction and loyalty across diverse market segments. For instance, the findings of this article can inform policymakers on the prioritization of key informational labels on food products, enabling food producers and marketers to better understand their standing in the minds of consumers as regards their preferences. This, in turn, can catalyze strategic market targeting efforts, notably through consumer segmentation. To provide a structured presentation of this paper, Section 2 delves into the conceptual framework underpinning the study. Section 3 elaborates on the research methods and procedures, while Section 4 offers an in-depth presentation and discussion of the research findings. Finally, Section 5 encapsulates this article’s key conclusions, bringing the study to a coherent and informative close.

2. Conceptual framework

2.1. Kenya’s geographical and socio-economic context of food choice behavior

As highlighted by Kimenyi and Kibe (Citation2014), Kenya’s economy serves as a linchpin within the Eastern African Communities (EAC), comprising nations such as Burundi, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda. Kenya’s economic prowess is instrumental in advancing the goals of continental integration, a commitment underscored by the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). In this context, every sector of a nation’s economy assumes a pivotal role, but none more than the agro-food sector. The agro-food sector stands out as a paramount driver of Kenya’s economy, a fact substantiated by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP, Citation2015) in 2015. In this regard, any novel insights that contribute to the ability of local and multinational players within the food industry to identify and create strategic niches while fostering inclusive growth with consumers hold immense value. Such knowledge can potentially catalyze the expansion and prosperity of this sector, a proposition underscored by the research of Binswanger-Mkhize and McCalla (Citation2010). In essence, understanding the dynamics and nuances of Kenya’s agro-food sector is not just an economic imperative but also a strategic necessity in the pursuit of sustainable growth and harmonious integration within the broader African economic landscape.

To foster inclusive growth, it is imperative for both local and multinational food producers to gain a deep understanding of the factors influencing consumer behavior, as emphasized by Pearson et al. (Citation2011). In this context, there is a growing consensus in the behavioral literature on the significance of sociodemographic factors in shaping consumer food choices (Bogue & Yu, Citation2016; Chen & Antonelli, Citation2020; Grunert, Citation2011). Income, for instance, emerges as a pivotal economic factor capable of predicting food choice patterns. This is because individuals with higher income levels possess greater purchasing power, enabling them to make choices that prioritize healthier foods and involve fewer trade-offs (Pechey et al., Citation2013; van Lenthe et al., Citation2015). Income also provides an intriguing dimension to the subject of this study, particularly in the context of Kenya, whose population represents a segment of the global population classified as low-income earners, according to the World Bank (Citation2021) data. However, within Kenya’s income strata, there exists a notable disparity between those at the upper echelons of the income pyramid and those at the base. It is reasonable to expect behavioral patterns to exhibit significant variation among these distinct income groups. Therefore, comprehending how income and other sociodemographic factors intersect with consumer food choices in Kenya is not only a matter of academic interest, but holds practical relevance for food producers seeking to tailor their offerings to diverse consumer segments and promote more inclusive growth within the country’s food industry.

Additionally, factors such as age, gender, educational attainment, and ethnicity hold significant importance as they are commonly used in the analysis of consumer attitudes and behaviors, particularly in studies of dietary knowledge and habits (e.g., Arganini et al., Citation2012; Ogundijo et al., Citation2021; Stran & Knol, Citation2013). These variables, in particular, play a pivotal role in understanding consumer food choices. For instance, existing research has demonstrated that the interplay between socioeconomic status and factors like gender, age, and educational level can exert a notable influence on the choices individuals make regarding healthy foods (Bihan et al., Citation2010; Kell et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, traditional dietary practices and cultural taboos in specific societies have been shown to significantly impact certain segments of the population, shaping their preferences for traditional foods (Chakona & Shackleton, Citation2019; Meyer-Rochow, Citation2009). Social factors and cultural practices are also influential determinants of dietary preferences. Individuals who belong to distinct ethnic clusters have typically grown up with unique cultural norms and practices that profoundly shape their perspectives and attitudes toward food choices (Ngugi et al., Citation2018; Wessel & Brien, Citation2010). In Kenya, a country characterized by the coexistence of approximately 70 ethnic groups, three major ethnic groups, namely the Kalenjin, Kikuyu, and Luhya, have particularly significant cultural influences on dietary preferences and habits. Understanding these complex intersections of age, gender, education, and ethnicity is crucial for gaining insights into the multifaceted landscape of consumer food choices in Kenya.

Moreover, the choice of food market that consumers most frequently patronize, be it a local food market, a formal supermarket, or an online market, is a significant factor influencing purchase decisions due to their distinct characteristics (Soukup, Citation2011; Veflen, Citation2012). In emerging markets, consumers often prefer local markets because these venues allow for the purchase of smaller quantities, price negotiation, and even credit opportunities (Figuié & Moustier, Citation2009). In contrast, formal markets, commonly referred to as supermarkets and increasingly common in Sub-Saharan Africa, tend to offer foods with higher processing levels (Popkin, Citation2017). They differ from local markets in terms of product variety, pricing structures, and the overall shopping experience (Hawkes, Citation2008).

Additionally, with the widespread global adoption of the Internet in recent years, the online retail food market is gaining traction, particularly among higher-income consumers. This digital marketplace introduces its own set of distinctive characteristics, setting it apart from both local and formal markets (Ogbo et al., Citation2019). Understanding how these different market types influence food purchase decisions is crucial for comprehending the diverse landscape of consumer choices in Kenya. While economic and social factors have been extensively studied to understand consumer behavior in terms of purchase decisions, it remains uncertain whether these factors significantly shape the appreciation of food values. Exploring the possibility of the existence of consumer clusters in Kenya based on their food value preferences is essential, as it can shed light on the idea that “we are most likely what we eat.” This research seeks to uncover patterns and associations between socioeconomic factors and the importance placed on various food values among Kenyan consumers.

2.2. Lifestyle and food values

Since the introduction of lifestyle concepts in consumer research in the mid-1960s (Bauer et al., Citation2012), understanding how consumers appreciate the value of their food lifestyles has provided producers and marketers with an edge. Food-related lifestyle (FRL) models (Grunert, Citation1993) of desired higher-order product qualities refer to characteristics that may apply to food values (Izquierdo-Yusta et al., Citation2019) a concept pioneered by Lusk and Briggeman (Citation2009) to explain food preferences in a stable set.

The comprehensive list of food values introduced by Lusk and Bridgeman in 2009 encompassed various dimensions, including appearance (the visual appeal of food), convenience (the ease of preparation and consumption), environmental impact (the ecological footprint of food production), fairness (equitable benefits for all involved parties), naturalness (minimal use of modern technologies in production), nutrition (nutritional content), origin (the source of agricultural products), price (cost), safety (freedom from health risks), taste (sensory appeal), and tradition (preservation of customary consumption patterns). Subsequent research has extended this list. For example, Bazzani and colleagues in 2018 introduced values related to animal welfare (the well-being of farm animals) and novelty (the appeal of trying something new), while omitting traditional values due to perceived consumer volatility.

Furthermore, in 2019, Izquierdo-Yusta and colleagues drew connections between Lusk and Bridgeman’s food values and Grunert et al.‘s food-related lifestyle (FRL) concept from 1993. Their work led to the categorization of consumers into three distinct clusters: the first cluster emphasizes price, while considering appearance and taste; the second prioritizes taste and convenience; and the third values health, environmental concerns, and social responsibility. In a similar vein, Femi-Oladunni et al. (Citation2023) developed a tailored classification of food values suited to an SSA country like Nigeria. Their classification drew on an extensive list of food values found in the literature, which served as the foundation for this study (see Table ).

Table 1. Description of food values used in this study

2.3. Theoritical underpinning and hypothesis development

The extensive body of research on food consumer behavior and marketing underscores the notion that consumers can be stratified into discrete groups based on their behavioral inclinations when it comes to purchasing and consuming food products. For instance, the work by Maehle et al. (Citation2015) pinpointed a cohort of consumers characterized by their hedonistic tendencies—these individuals exhibit strong preferences for the sensory attributes of food, especially taste, aligning with a hedonic perspective (Maehle et al., Citation2015). Conversely, some scholars argue that certain consumers tend to adopt a more pragmatic and rational approach, prioritizing the utilitarian aspects of food consumption, often leading to price-conscious decision-making (Firmansyah et al., Citation2022; Maehle et al., Citation2015).

In 2011, Fuljahn and Moosmayer introduced an intriguing perspective, suggesting that consumers may exclusively categorize products as either hedonic or utilitarian, a concept that resonates with aspects of Social Identity Theory (SIT). This theory delves into how individuals align themselves with specific groups based on shared attitudes and behaviors (Fuljahn & Moosmayer, Citation2011; Hodson & Earle, Citation2020; Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979). In contrast, Izquierdo-Yusta et al. (Citation2019) introduced another layer of complexity by exploring significant differences between clusters of consumers predicated on their food value preferences. They included a novel category known as the “ethical group,” comprising consumers that prioritize social justice considerations related to food production. This group includes concerns about the environmental impact of the food they consume. This expanded viewpoint offers a more nuanced comprehension of consumer behavior and preferences within the realm of food products, aligning harmoniously with Consumer Segmentation and Targeting Theory, which underscores the significance of identifying and tailoring marketing strategies for specific consumer segments (Dibb & Simkin, Citation2009; Izquierdo-Yusta et al., Citation2019).

The identification of distinct consumer groups within any economy or society holds substantial value for producers and marketers. It equips them with the capacity to precisely target and cater to diverse consumer needs and preferences (Aljukhadar & Senecal, Citation2022; Parvin et al., Citation2016). This alignment with the principles of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) is noteworthy. TPB, posited by Ajzen in 1985, underscores the importance of comprehending attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control in predicting and influencing consumer behavior (Ajzen, Citation1985, Citation2011). Expanding upon prior research and taking cues from the consumer cluster discoveries made by Izquierdo-Yusta et al. (Citation2019), as well as the food value categorization framework established by Femi-Oladunni et al. (Citation2023) (illustrated in Table ), we propose that within the demographic we are investigating, there are discernible consumer clusters. Consequently, we present the following hypotheses:

H1: The preferences for the food values of price, safety, environmental impact, nutrition, and weight and measures will conform three consumer clusters, namely, utilitarian, hedonic and ethical.

Building upon the literature discussed in Section 2.1, which suggests that sociodemographic variables can impact consumers’ food purchase decisions, this study seeks to examine whether the preferences for food values among consumer clusters are influenced by a range of sociodemographic factors. These factors encompass income, age, gender, marital status, education level, the type of food market predominantly frequented, and the ethnicity of consumers. Consequently, our hypothesis posits that discernible variations in the appreciation of food values among consumer clusters can be observed based on the specific sociodemographic context unique to each consumer. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

H2: There are significant differences between food value clusters according to the sociodemographic variables of the consumers.

Among the sociodemographic factors linked to economic and social contexts, the role of income in shaping food preferences stands out. Numerous studies have underscored that individuals with higher incomes tend to prioritize healthier, organic, and premium food options (ethics-rooted ethics), while those with lower incomes often gravitate towards cost-effective and processed foods (hedonic or utilitarian-rooted products), leading to a discernible income-based disparity in food choices (Darmon & Drewnowski, Citation2015; Hough & Sosa, Citation2015). Thus, it is crucial to investigate whether these income-based differences extend to food value clusters, hence we propose that:

H2a: There are significant differences between food value clusters according to the estimated monthly income of the consumers.

Moreover, the selection of the shopping venue significantly influences consumers’ food choices. For instance, Dudziak et al. (Citation2023) discovered that both men and women residing in areas with varying population densities predominantly shop for food in super and hypermarkets. Notable exceptions to this trend, as noted by Dudziak et al. (Citation2023), are men residing in small towns, who reported a preference for online shopping and large cash and carry wholesalers. Nonetheless, some consumers are less inclined to patronize super or hypermarkets due to the distance to the nearest super and hypermarkets, leading them to opt for traditional markets (Debela et al., Citation2020). Therefore, we intend to explore whether these shopping venue preferences have a significant impact on the formation of food value clusters. Thus, we propose that:

H2b: There are significant differences between food value clusters according to the food market type patronized by the consumers.

Furthermore, consumer ethnicity constitutes another critical sociodemographic factor affecting food choice preferences. Several studies have established that individuals from diverse ethnic backgrounds often adhere to specific dietary traditions and preferences. For instance, according to Barrena et al. (Citation2015), Arab couscous consumers place greater emphasis on factors such as the geographic origin of the product, cultural identity, and fulfilling family obligations when purchasing the food. However, Barrena et al. (Citation2015) found that Spanish couscous consumers claim that their food choices reflect the latest trends and the most cosmopolitan and successful image of their environment (hedonist or utilitarian rooted). Given this reasoning, cultural and ethnic influences may contribute to the formation of food value clusters, and we therefore propose that:

H2c: There are significant differences between food value clusters according to the ethnic identity of the consumers.

Regarding sociodemographic variables related to individual characteristics, age emerges as another crucial factor that may significantly impact on consumers’ food choices. Research indicates that millennials tend to prioritize food items that align with their mood, offering stress relief, happiness, good taste, appealing texture, and value for money (Shipman, Citation2020). Conversely, Chambers et al. (Citation2008) note that older participants (aged 60 and above) are more likely to base their food choices on health considerations, while those aged 18 to 30 tend to focus on factors related to food preparation, price, and convenience. Therefore, we seek to explore whether these age-related differences also manifest in the formation of food value clusters. Thus, we posit that:

H2d: There are significant differences between food value clusters according to the age of consumers.

Gender-based disparities in food choices are also well-documented. For example, Basfirinci & Cilingir (Citation2017) suggest that women tend to opt for health-conscious options, while men often favor indulgent and calorie-dense foods. The preference for ”natural” food attributes has also been observed to be associated with various factors, such as women being less likely to be in a formal relationship or have children, and men having lower to moderate income levels and an education attainment lower than college level (Bellows et al., Citation2010). In light of these gender-based findings, we believe that these disparities may extend to the formation of food value clusters. Thus:

H2e: There are significant differences between food value clusters according to the gender of the consumers.

Marital status is another sociodemographic factor that may also have to do with food choices. Research suggests that marital status is associated with dietary behavior, with married individuals often adopting healthier dietary patterns, while previously married men may make poorer dietary choices (Kroshus, Citation2008). This aligns with findings indicating that married participants tend to adhere to healthy eating patterns (Yannakoulia et al., Citation2008). Thus, based on the marital status of consumers, we believe that the formation of food value clusters may vary. Thus, we propose that:

H2f: There are significant differences between food value clusters according to the marital status of the consumers.

Finally, educational attainment is a critical sociodemographic factor that shapes food choices. Research by Darmon & Drewnowski (Citation2015) suggests that individuals with higher educational attainment tend to favor more nutritious, whole, and organic foods, while those with lower educational levels may be more inclined to opt for more affordable but less healthy options (Le et al., Citation2023). Given the significance of education in shaping food choices, educational attainment may play a role in the formation of food value preference clusters. Thus, we propose that:

H2g: There are significant differences between food value preference clusters according to level of educational attainment of the consumers.

3. Methods and procedure

3.1. Sample, procedure, and instruments

The data used in this study were collected through a structured questionnaire, which was administered as part of a field survey. This survey was made possible through a collaborative effort between the authors and Datastat Research and Training Centre, an organization with extensive experience in conducting field research in our study area. Nairobi County was chosen as the study location due to its diverse population, which represents all Kenyan ethnicities, totaling over 70 ethnic groups according to the World Population Review (Citation2023). The county, located in the south-central part of Kenya, is the most populous in the country, with an estimated population of over four million people, as reported by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS, Citation2020). Notably, the major ethnic groups in Nairobi County are the Kalenjin, Kikuyu, and Luhya. Moreover, the characteristics of Nairobi County’s urbanization have led to significant shifts in spatial dynamics, impacting both agriculture and private food production. Unlike residents in rural areas of Kenya, who may engage in private food production, Nairobi County’s residents often rely on purchasing food, making it an ideal location for studying consumer purchasing behavior and testing our research hypotheses. The data collection process took place over a six-week period in 2020, specifically from June 8th to July 17th. The survey respondents included individuals aged 18 and above who were residents of Nairobi. A total of 500 respondents were randomly selected to participate in the survey (see Table for details). It is worth underlining that random selection was chosen to ensure the representativeness of the sample.

Table 2. Technical details of the research

To assess the appreciation of food values among the respondents, we employed a scale adapted from the work by Izquierdo-Yusta et al. (Citation2019, Citation2020), which itself was derived from the scale developed by Lusk and Briggeman (Citation2009). The respondents were instructed to rate their level of appreciation for each food value using a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5. In this scale, a rating of 1 corresponded to the least appreciated response choice, while a rating of 5 indicated the highest level of appreciation when making food purchase decisions. Before providing ratings for their appreciation of food values, respondents were first required to furnish socio-demographic information, including their estimated monthly income, age, gender, and level of educational attainment. Additionally, they were asked to specify the type of food market they most frequently patronized and to indicate their ethnic group affiliation.

Table provides an overview of the survey’s descriptive statistics. Notably, a majority of our respondents reported earning incomes above the minimum wage, which stood at 13,500 Kes at the time of data collection (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics KNBS, Citation2020). In terms of gender distribution, 43.2% of respondents identified as male and 56.80% as female. The average age of the respondents was approximately 45.42 years. Regarding food shopping preferences, a significant portion of the respondents favored local markets (57.8%), followed by those who preferred formal retail stores (32.8%). Interestingly, only 9.4% of respondents indicated a preference for online food markets. This data suggests that a substantial number of respondents favored the tangible experience of purchasing food products in physical stores rather than making online purchases. Furthermore, the respondents represented a diverse range of ethnic backgrounds, with 52.80% from the Kikuyu group, 23.80% from the Luhya ethnic group, 16.80% from the Kalenjin group, and 6.60% belonging to other ethnicities.

Table 3. Distribution of sample responses

3.2. Data analysis

IBM SPSS v. 28 was used to analyze the data and test the hypotheses. Specifically, Spearman’s Correlation Analysis, two-step cluster analysis, and multivariate logistic regression analysis (MLRA) were used to fulfil the objectives of this research. Spearman’s correlation analysis was performed to determine the extent to which rated food values varied. Thus, this analysis was expected to reveal the extent to which food values increase or decrease simultaneously. The implication of this is that a negative correlation indicates the range in which the food value increases as the other value decreases and vice versa.

A two-step cluster analysis was used to organize consumers into clusters based on how closely related they were, while the latter analysis (MLRA) was adopted because, from the two-step cluster analysis, two unique cluster groups with good cohesion were identified. Hence, it was indicative of utilizing a binary dependent variable, and MLRA best helped predict the probabilities of different possible outcomes of the dependent variable. EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) represents the multivariate logistic regression specifications:

where log (p/1-p) is the response variable (the cluster group of an individual), β0 is the intercept and coefficients β1 … β7 represent sociodemographic variables, namely, estimated monthly income, age, gender, marital status, level of educational attainment, and ethnicity. The predictor variables were β1= estimated monthly income; β2= age; β3 = gender; β4 = marital status; β5= educational attainment; β6 = market type; β7 = ethnicity; and α is error term (gender, marital status, educational attainment, market type, and ethnicity are categorical variables).

The interpretation of this model indicates that when there is a one-unit change in a predictor variable, the likelihood of a change in the logit of the response variable, compared to the reference group, can be predicted based on the respective parameter estimate. This prediction assumes that all other variables in the model remain constant. It is worth noting that the parameters in this model are defined relative to specific reference groups for each variable. This means that when we talk about the predicted probability, we are essentially discussing the likelihood of belonging to one of the consumer food value cluster groups. For instance, when analyzing gender, we consider “female” as the baseline group for comparison. Similarly, when examining marital status, the reference group is “single.” In the context of ethnicity, we use the “Luo” group as the reference, primarily because they are not so prevalently represented in the Kenyan population as other ethnic groups. Lastly, when studying the most frequently chosen food market, we designate “online market” as the reference group, and when evaluating educational attainment, “postgraduate” is the reference category. These reference groups are essential to understand and interpret the probabilities associated with membership in specific consumer food value cluster groups.

4. Results

4.1. Overall results

Assessing the variations in the consumers’ ratings of food value preferences, the results showed a correlation between the food value preferences. Regarding the findings from the cluster analysis, two distinct consumer clusters were revealed at an average silhouette measure of cohesion and separation of 0.6, indicating a good clustering analysis (Dudek, Citation2020). The two unique consumer clusters identified in this study are ethical and utilitarian, and H1 was thus partially supported. A multivariate logistic regression model was estimated from these clusters, and the results revealed that Hypotheses H2a, H2c, H2d, H2e, H2f, and H2g could be accepted because there were significant differences in the appreciation of food values in consumer clusters depending on income, gender, marital status, level of educational attainment, food market type patronized, and ethnicity. However, H2b could not be accepted, as there were no significant differences depending on the age of consumers. Hence, there is a discernible relationship between income, gender, marital status, level of educational attainment, market type most often patronized, ethnic group, and consumer food value clusters. However, it should be noted that age does not exhibit a significant association with these consumer food value clusters.

4.2. Discussion

4.2.1. Spearman’s correlation

Table presents the results of a Spearman correlation analysis examining the relationships between respondents’ food value preferences. The findings reveal several patterns of correlation between these preferences. Firstly, there is a positive correlation between the following pairs of food values: environmental impact and nutrition, environmental impact and safety, and nutrition and safety. In simple terms, when one of the values in these pairs is considered important by respondents, the other value tends to be seen as important as well. This positive correlation suggests that individuals who prioritize environmental impact as a food value are also more likely to emphasize the importance of nutrition and safety. Likewise, those who value nutrition are more inclined to consider safety important in their food choices.

Table 4. Spearman’s correlation analysis among food values

Conversely, some pairs of values show a negative correlation: environmental impact and price, environmental impact and weight and measures (WM); nutrition and price, nutrition and WM, price and safety, and safety and WM. This negative correlation implies that when respondents regard environmental impact as a crucial factor in their food purchasing decisions, they are less likely to prioritize price and WM. Similarly, those who prioritize nutrition in their food choices are less likely to attach importance to price and WM. Lastly, individuals who consider safety a significant factor in food purchasing decisions are less likely to deem price and WM to be important criteria.

4.2.2. Cluster analysis

Cluster analysis is a method that groups items or individuals together based on how closely related they are. There are various ways to perform cluster analysis, including k-means, hierarchical, and two-step methods. In this study, we used a two-step cluster analysis approach, given its ability to handle both categorical and continuous data simultaneously, which is particularly relevant to our research (Rundle-Thiele et al., Citation2015; Tkaczynski, Citation2017).

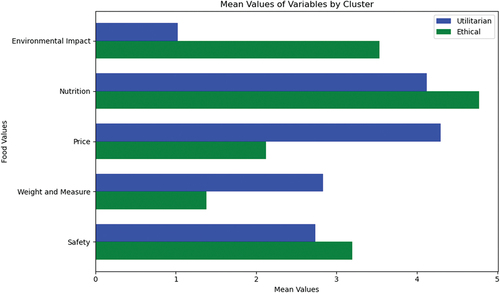

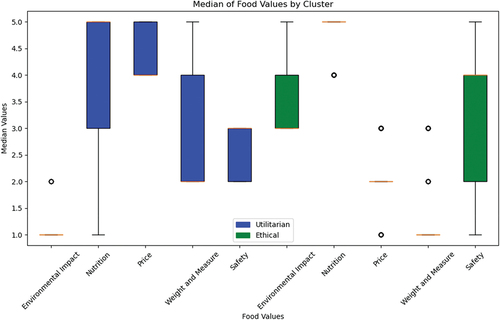

To evaluate the quality of the clusters created by the two-step cluster analysis, we considered the silhouette measure of cohesion and separation. Our data indicated that at cluster level 2, there was an average silhouette measure of cohesion and separation of 0.6 (see Table ). This value suggests that the clustering performed well (Dudek, Citation2020). As a result, this study identified two distinct and internally consistent consumer segments concerning the food values under examination, which we called utilitarian and ethical. The interquartile range, as depicted in Figure , indicates that within the utilitarian cluster, there exists a higher degree of variability compared to the ethical cluster. This observation suggests that profiling individuals within the ethical group might be a relatively more straightforward task than the profiling of utilitarian consumers. Consequently, this could empower marketers to devise more precise and effective targeting campaigns tailored to capture the attention of ethical consumers.

Table 5. Sociodemographic profile of utilitarian and ethical consumer clusters

4.2.2.1. Utilitarian consumers (cluster 1)

The larger cluster in our analysis consisted of 289 individuals (see Table ). On average, individuals in this cluster have a monthly income of Kes 47,415.22, which is lower than the income level of those in the other cluster. This cluster is predominantly composed of male consumers from the Gen X generation, with a significant portion having only a primary level of education. The majority of consumers in this cluster prefer to shop at local markets and primarily belong to the Kikuyu ethnic group. We categorize this cluster as the “utilitarian” cluster because the values preferred by its members, in descending order, are price, nutrition, weight and measures, safety, and environmental impact. Notably, this cluster stands out from the others, particularly in terms of the importance placed on price and weight and measure values, as depicted in Figures . This distinction aligns with the classification made by (Izquierdo-Yusta et al., Citation2019).

From Figure , we can draw several conclusions regarding the preferences of consumers within this particular cluster. It is evident that these consumers exhibit a high degree of homogeneity in their preference for price as a crucial factor. However, when we examine the variables of weight and measures and nutrition, we observe a notably higher level of heterogeneity in terms of the importance levels assigned by individuals within this cluster. Of these variables, nutrition stands out as the one with the most significant degree of heterogeneity. In contrast, the safety value indicates that consumers in this cluster tend to align more closely in giving less preference to this particular aspect. Lastly, when considering the environmental impact value, we find the highest level of homogeneity among the analyzed values. This suggests that utilitarian consumers within this cluster generally do not prioritize environmental concerns when making food purchases.

4.2.2.2. Ethical consumers (cluster 2)

The second cluster in our analysis was smaller, comprising 211 individuals (see Table ). On average, individuals in this cluster have a higher mean estimated monthly income of Kes 135,763, which is more than 50% higher than that of individuals in Cluster 1. This cluster is primarily made up of Gen X consumers, with a significant majority being females (64.45%). A majority of these have attained higher levels of education beyond primary and secondary education. Interestingly, none of the individuals in this cluster prefer local markets, tending to patronize formal retail stores or online food stores. The two dominant ethnic groups in this cluster are Luhya and Kikuyu, accounting for 44.08% and 31.75%, respectively. We classify this cluster as the “ethical” cluster because the values preferred by its members, in descending order, are nutrition, environmental impact, safety, price, and weight and measures (WM). Figures illustrate that they assign a much higher importance to environmental impact compared to the other clusters, which is considered a significant ethical aspect of food choices (Della Corte et al., Citation2018). Additionally, they place a greater emphasis on safety and nutrition, aligning with ethical considerations, as noted in previous research (Della Corte et al., Citation2018).

Based on Figure , it becomes evident that consumers within this cluster exhibit a greater degree of uniformity in their prioritization of the food values analyzed. In this scenario, consumers predominantly converge in their preferences, placing a notably high emphasis on nutrition, a low emphasis on price, and an even lower emphasis on weight and measures. However, within this same cluster, we also observe a higher level of variability when it comes to the importance assigned to environmental impact and safety values. Interestingly, while the preference levels for these two food values are higher than those in the utilitarian cluster, there remains a notable degree of heterogeneity among consumers within this cluster regarding their importance.

4.2.2.3. Overall findings from clustering

Consumers in the utilitarian cluster prioritize values like price and weight and measures when making food choices. Conversely, the ethical cluster places a higher emphasis on environmental impact, safety, and nutrition as important characteristics. As demonstrated in Table , there is a negative correlation between environmental impact, safety, and nutrition on one hand, and price, weight, and measures on the other hand. This negative correlation supports the validity of this classification and suggests that the two consumer clusters are inversely related to each other in terms of their value preferences.

4.2.3. Multivariate logistic regression

The multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that age, sex, level of education, ethnicity, and income had significant effects on the food value group clusters, as indicated by χ2(4) = 38.168, p < .0005 (see Table ). This model accounted for 47% of the variability in the food value group clusters, measured by Nagelkerke R2. Furthermore, it correctly classified 75% of the cases, which aligns with findings in the existing literature (Menard, Citation2002).

Table 6. Multivariate logistic regression for food values cluster group

Table provides the multivariate logistic regression findings, wherein the dependent variable is the consumer food value cluster group encompassing utilitarian and ethical categories. Given the dichotomous nature of the dependent variable, the analysis focuses on the predicted probability of belonging to the ethical cluster, while other predictor variables are held constant. Positive coefficients within the model indicate a heightened likelihood of individuals aligning with the ethical cluster. To elaborate, firstly, an increment of one unit in estimated monthly income (β1 = 0.151, p < 0.1) corresponds to a 1.1-fold greater likelihood of individuals being part of the ethical cluster. Secondly, female consumers (β3 = 0.948, p < 0.01) exhibit a 2.58-fold higher probability of belonging to the ethical clusters. Consumers with marital statuses other than single, married, divorced, or widowed (β4; x1 = −3.396, p < 0.01; x2 = −2.977, p < 0.05; x3 = −3.705, p < 0.01) are more likely to align with the utilitarian cluster. Additionally, the results indicate that consumers with primary and undergraduate educational backgrounds (β5; x1 = −1.641, p < 0.01; x3 = −1.403, p < 0.01) are more likely to be associated with the utilitarian cluster, whereas postgraduate consumers tend to align with the ethical consumer group.

Finally, consumers from the Kalenjin and Luhya ethnic groups (β7; x1 = 2.160, p < 0.01; x3 = 2.724, p < 0.01) were more likely to be in the ethical consumer cluster. While Kalenjin are 8.67 times more likely to be in this food cluster, the likelihood of Luhya being in the cluster is almost twice— 15.25 times—as great as Kalenjin consumers. By contrast, those from the Luo ethnic group were more likely to belong to the utilitarian cluster. Notably, the most frequently patronized food market in the logistic regression model was not included because of the perfect prediction between the consumers’ food value cluster groups. For instance, all consumers in the utilitarian cluster patronize the local food market most often, whereas none of the consumers in the ethical cluster do so.

5. Overall Discussion and Conclusion

The position of Nairobi (Kenya) in the EAC makes it an important cog in the economic development and regional integration of the African tale. In addition, it is an attractive economy for fast-moving consumer goods. The objective of this study was to analyze the possible existence of consumer clusters in this country, depending on their appreciation of food values.

To fulfil this objective, a field study was conducted by a data-collection organization (“Datastat Research”) in the local community of Nairobi, whose skill in gathering information in the field was leveraged. The respondents (n = 500) were randomly selected inhabitants of Nairobi County, Kenya, and Spearman’s correlation, and 2-step cluster analysis and regression logistic analysis were adopted.

Spearman’s correlation analysis revealed that consumers who believe that the environmental impact is important are more likely to believe that nutritional and safety values are important, and those who believe that the nutritional value is important are more likely to believe that the safety value is important. Additionally, consumers who believe that environmental impact is an important factor in food purchase decisions are less likely to believe that the values of price and weight and measures are important, whereas those who believe that safety is important are less likely to believe that price and weight and measures are important. Thus, as mentioned, we can conclude that consumers who can be classified as ethical are less likely to make decisions on a utilitarian basis and vice versa.

Two different consumer clusters were identified using two-step cluster analysis. The clusters are labeled as (i) utilitarian consumers and (ii) ethical consumers. The logistic regression model showed that estimated monthly income plays a significant role, because as income increases, consumers are more likely to be ethical, and as income decreases, consumers are more likely to be utilitarian consumers. Along the same lines, other factors, such as gender, marital status, level of education, and ethnic identity, were also influential sociodemographic factors that predicted consumers’ food value clustering. As mentioned before, being female (vs. male), single (vs. being in a larger family), and highly educated (vs. lowly educated) was positively associated with preferring ethical values (environmental impact, safety, and nutrition) in making a purchase decision regarding food.

5.1 Theoritical contributions

The findings of this study coincide with prior studies in the field. Specifically, our observations regarding the impact of income on food value preferences are consistent with existing literature that delves into consumer behavior shaped by income levels (e.g., Izquierdo-Yusta et al., Citation2019; Maehle et al., Citation2015; Peñaloza et al., Citation2017). This concurrence underscores the significance of income as a determining factor in comprehending consumers' behavioral inclinations within specific market segments. Furthermore, our findings lend support to the conclusions drawn by Ni et al. (Citation2013) and Parvin et al. (Citation2016), who highlighted that low-income households, more inclined towards utilitarian preferences, tend to exhibit heightened sensitivity to price fluctuations compared to their high-income counterparts, all of which underscores the importance of income levels in shaping consumers' responses to price dynamics. In fact, the income levels of the ethnicities evaluated here could explain why the Luhya and Kalenji ethnic groups are more oriented toward ethical than utilitarian values when buying food. As explained, a higher income level appears to be positively correlated with an ethical perspective on food purchase decisions, hence, given that the Luhya ethnicity has a higher mean estimated income than the Kalenji ethnic group, and both report a higher mean income than Luo and Kikuyu, it is of no surprise that the Luhya and Kalenji ethnic groups appear to be more positively associated with the ethical cluster.

With regards to our gender findings, the behavioral divergence between genders we noted, with females exhibiting a greater inclination toward ethical consumerism, suggests that female consumers tend to adhere more strongly to deontological and ethical principles compared to their male counterparts, in line with previous studies (Ruiz-Palomino et al., Citation2019a, Citation2019b, Citation2020, Citation2021). This finding also aligns with studies such as those by Friesdorf et al. (Citation2015) and Dalton & Ortegren (Citation2011), which have consistently demonstrated that males are more inclined to adopt utilitarian perspectives in their decision-making processes. As such, these insights shed light on the gender-based variations in ethical and utilitarian consumer behaviors and underscore the importance of considering gender a key determinant in understanding consumer preferences and choices.

Regarding the impact of marital status of consumers in conforming one or another cluster of consumers, a nuanced interpretation of the impact of marital status reveals parallels with the concept of a dependency ratio or family size. When considering other variables held constant, our results indeed suggest that single individuals are more likely to align with ethical consumer values, which implies that as family size increases, consumers may lean more toward utilitarian considerations in their food consumption choices. This interpretation aligns with the findings of Koschate-Fischer et al. (Citation2018), who highlighted that consumers tend to become more price-conscious during significant life-changing events, such as the birth of a child, retirement, and marriage. Thus, our study reveals that marriage and potentially larger family sizes likely lead to greater emphasis on utilitarian aspects (e.g., price considerations) in food purchase decisions.

Finally, the explanation behind the positive role of the level of education in conforming the ethical cluster of consumers is likely to rely on the consumer’s level of income, as with a higher level of education, the income of consumers is likely to be higher, and so will be their orientation toward ethical values when purchasing food. Indeed, our statistical analysis showed that higher-income consumers are more likely to be ethical consumers, which is in line with previous theory (Maslow, Citation1943) that suggests that the aspirations of individuals that have already lower order needs totally met thanks to their high estimated monthly income (e.g., safety, physiological needs) are more likely to be related to meeting those needs that are involved at the upper positions in the Maslow’s pyramid of needs (e.g., self-realization, prestige, Maslow, Citation1943; transcendence or spiritual needs, Maslow, Citation1996; Melé, Citation2009), which would confirm our findings that a higher level of education is more associated with the ethical than the utilitarian cluster of consumers. Anyway, our findings are in line with previous research that indicates that the level of education is positively associated with making ethical decisions or behaving in a manner that reflects a focus on satisfying others’ needs (Elche et al., Citation2020; Ruiz-Palomino et al., Citation2023a) –which has clearly ethical connotations (Ruiz-Palomino et al., Citation2021, Citation2023a)– and lead us to conclude that those food consumers who possess higher levels of education may be less fond of utilitarian values but more sticked to ethical values when making food purchase decisions.

5.2. Practical implications

As practical implications, some interesting insights appear to emerge. For example, because consumers' most and least preferred values in the Nairobi County’s (and likely extendable to Kenya’s) food market are nutrition and environmental impact, respectively, our findings have important implications for food producers, marketers, and policymakers in this or other cultural related areas in the world. Indeed, with this information, food producers and marketers can emphasize the nutritional benefits of manufactured and marketed foods when branding products. Furthermore, they can position themselves in the market by using the nutritional benefits of their products, which could be a good strategic tool for gaining an advantage over their competitors. In addition, although the impact of food production on the environment is generally the least preferred value among the consumers who participated in our study, there is a preference (found in our analysis) for this value among high-income earning consumers compared with low-income earning consumers. Hence, the environmental benefits of the food production process could be a tool for the strategic labeling of high-end products, especially in those with greater purchasing power.

In addition to the above-described interesting implications, our findings can be utilized by food producers and marketers to develop marketing strategies that appeal to both ethical and utilitarian consumer groups. For instance, these agents can create marketing campaigns that focus on the ethical values of their products for female consumers while focusing on utilitarian values for male consumers. They can also use pricing strategies that appeal to low-income individuals or households by offering discounts or promotions to make the products affordable. In summary, food marketing campaigns could target ethical and utilitarian consumers based on their income level, marital status, educational attainment, market type, and ethnicity of potential consumers.

As important implications for food policymakers, there is a clear need for food security policies to make nutritious food accessible to everyone, irrespective of the incomes class. This is useful, considering that there is a segment of the population that, according to our findings, only appreciates the utilitarian aspect, which is probably because they face problems of food accessibility. Simultaneously, despite our findings revealing that the environmental impact value is the least preferred among the majority of the population we surveyed, there is a clear segment of the population that is fond of food ethical values (including the environmental impact and the safety issue) when making food purchase decisions. As such, policymakers in Kenya should also work to ensuring that food insecurity does not increase and that consumers have also sufficient access to food that is sustainably distributed and manufactured, which would mean developing policies that provide incentives for food producers who use sustainable and food safety practices.

5.3. Limitations and future research lines

This work, like many others, has also limitations. A prominent limitation is that it was an experimental cross-sectional study that failed to provide a complete portrayal of the populace of Nairobi County. This study relied on the use of field rather than online surveys to collect data, which resulted in the obtaining of data of 500 respondents in an economy of over four million people. Thus, a more complete study could intend to cover a higher percentage of this populace and even be extendable to other African countries. Another related limitation of this study is our focus on only one African country, and therefore the inability to compare our findings with those obtained from other more developed countries. The Hofstede Center (Citation1967-2023) suggests that countries differ in certain values that are related to the ones we analyzed here, which could make decisions in life and in the specific area of food purchase decisions vary across countries.

The theoretical implications of this study encompass a holistic understanding of consumer behavior in the context of food values and market environments, at least in a SSA country like Kenya. Notably, however, the significant influence of market type on consumer cluster membership (e.g., all utilitarian consumers patronize the local market but none of the ethical consumers do so in this type of market) suggests the need for in-depth exploration of how various retail settings, such as local markets and online platforms, shape consumer preferences and choices. Furthermore, this study calls for a re-evaluation of existing consumer behavior theories to accommodate the coexistence of ethical and utilitarian food values, encouraging the development of novel theoretical models that elucidate the intricate interplay between these values and other psychological and sociodemographic factors.

Additionally, it would be interesting that future research designs be of a longitudinal nature to unveil the evolving dynamics of consumer food values over time and unveil the impact of external factors like economic factors and cultural change. Also, as we described earlier, extending the investigation to cross-cultural comparisons can illuminate the cultural variations in food value preferences, enabling the creation of more culturally sensitive marketing strategies tailored to diverse consumer contexts. In future research, it would also be interesting to test and hypothesize the food value preferences of utilitarian consumers against those of ethical consumers when considering factors such as those considered by Clements & Si (Citation2018) such as the diet diversity and the quality of the food. Finally, another interesting research question could be the analysis of whether food consumers will switch brands or remain loyal if their income level remains constant and food inflation continues to increase.

Ethical compliance

All procedures were performed in accordance with the University’s ethical standards.

Acknowledgments

A previous version of this paper was published as a Working Paper of “DOCFRADIS COLECCION DE DOCUMENTOS DE TRABAJO CATEDRA FUNDACION RAMON ARECES DE DISTRIBUCION COMERCIAL” Spain. Doc 06/2023.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckman (Eds.), Action-control: From cognition to behavior (pp. 11–23). Springer.1124I. Ajzen.

- Ajzen, I. (2011). The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychology & Health, 26(9), 1113–1127. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2011.613995

- Aljukhadar, M., & Senecal, S. (2022). Targeting the very important buyers VIB: A cluster analysis approach. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2088458. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2088458

- Anderson, J. C., & Wynstra, F. (2005). The adoption of the total cost of ownership for sourcing decisions––a structural equations analysis. Accounting, Organizations & Society, 30(2), 167–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2004.03.002

- Antwi, A. O., & Matsui, K. (2018). Consumers’ food value attributes on Ghana’s local market; case study of Berekum Municipality. International Journal of Environment, Agriculture and Biotechnology, 3(3), 834–838. https://doi.org/10.22161/ijeab/3.3.18

- Arganini, C., Saba, A., Comitato, R., Virgili, F., & Turrini, A. (2012). Gender differences in food choice and dietary intake in modern Western societies. Public Health-Social and Behavioral Health, 4, 83–102. Available at: http://www.intechopen.com/books/public-health-social-and-behavioralhealth/gender-differences-in-foodchoice-and-dietary-intake-inmodern-western-societies

- Barrena, R., García, T., & Sánchez, M. (2015). Analysis of personal and cultural values as key determinants of novel food acceptance: Application to an ethnic product. Appetite, 87, 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.12.210

- Basfirinci, C., & Cilingir Uk, Z. (2017). Gender-based food stereotypes among Turkish university students. Young Consumers, 18(3), 223–244. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-12-2016-00653

- Bauer, M., Auer‐Srnka, K. J., & Wooliscroft, B. (2012). The life cycle concept in marketing research. Journal of Historical Research in Marketing, 4(1), 68–96. https://doi.org/10.1108/17557501211195073

- Bazzani, C., Gustavsen, G. W., Nayga, R. M., & Rickertsen, K. (2018). A comparative study of food values between the United States and Norway. European Review of Agricultural Economics, 45(2), 239–272. https://doi.org/10.1093/erae/jbx033

- Bellows, A. C., Alcaraz, G., & Hallman, W. K. (2010). Gender and food, a study of attitudes in the USA towards organic, local, US grown, and GM-free foods. Appetite, 55(3), 540–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2010.09.002

- Bihan, H., Castetbon, K., Mejean, C., Peneau, S., Pelabon, L., Jellouli, F., Le Clesiau, H., & Hercberg, S. (2010). Sociodemographic factors and attitudes toward food affordability and Health are associated with fruit and vegetable consumption in a low-income French population. The Journal of Nutrition, 140(4), 823–830. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.109.118273

- Binswanger-Mkhize, H., & McCalla, A. F. (2010). The changing context and prospects for agricultural and rural development in Africa. Handbook of Agricultural Economics, 4, 3571–3712. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0072(09)04070-5

- Bogue, J., & Yu, H. (2016). The influence of sociodemographic and lifestyle factors on consumers’ healthy cereal food choices. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 22(3), 398–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/10454446.2014.949985

- Carroll, R., & Vallen, B. (2014). Compromise and attraction effects in food choice. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 38(6), 636–641. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12135

- Hofstede Center (1967-2023). Geert Hofstede Cultural Dimensions. Retrieved November 18, 2023, from https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison-tool

- Chakona, G., & Shackleton, C. (2019). Food taboos and cultural Beliefs influence food choice and dietary preferences among pregnant women in the eastern cape. South Africa Nutrients, 11(11), 2668. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11112668

- Chambers, S., Lobb, A., Butler, L. T. & Traill, W. B.(2008). The influence of age and gender on food choice: A focus group exploration. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 32(4), 356–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2007.00642.x

- Chen, P.-J., & Antonelli, M. (2020). Conceptual models of food choice: Influential factors related to foods, individual differences, and Society. Foods, 9(12), 1898. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9121898

- Clements, K. W., & Si, J. (2018). Engel’s law, diet diversity, and the quality of food consumption. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 100(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aax053

- Dalton, D., & Ortegren, M. (2011). Gender differences in Ethics research: The importance of controlling for the Social desirability response bias. Journal of Business Ethics, 103(1), 73–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0843-8

- Darmon, N., & Drewnowski, A. (2015). Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: A systematic review and analysis. Nutrition Reviews, 73(10), 643–660. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuv027

- Debela, B. L. Demmler, K. M. Klasen, S. & Qaim, M.(2020). Supermarket food purchases and child nutrition in Kenya. Global Food Security, 25, 100341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2019.100341

- Della Corte, V., Del Gaudio, G., & Sepe, F. (2018). Ethical food and the kosher certification: A literature review. British Food Journal, 120(10), 2270–2288. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-09-2017-0538

- Dibb, S., & Simkin, L. (2009). Bridging the segmentation theory/practice divide. Journal of Marketing Management, 25(3–4), 219–225. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725709X429728

- Dudek, A. (2020). Silhouette index as clustering evaluation tool. In K. Jajuga, J. Batóg, & M. Walesiak (Eds.), Classification and data analysis. SKAD 2019. Studies in classification, data analysis, and knowledge organization. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52348-0_2

- Dudziak, A., Stoma, M., & Osmólska, E. (2023). Analysis of consumer behaviour in the context of the Place of Purchasing Food Products with particular emphasis on local Products. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2413. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032413

- Elche, D., Ruiz-Palomino, P., & Linuesa-Langreo, J. (2020). Servant leadership and organizational citizenship behaviour. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(6), 2035–2053. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijchm-05-2019-0501

- Femi-Oladunni, O. A., Martínez-Ruiz, M. P., Ruiz-Palomino, P., & Muro-Rodríguez, A. I. (2023). Food values influencing consumers’ decisions in a sub-Saharan African country. British Food Journal, 125(5), 1805–1823. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-02-2022-0144

- Femi-Oladunni, O. A., Ruiz-Palomino, P., Martínez-Ruiz, M. P., & Muro-Rodríguez, A. I. (2021). A Review of the literature on food values and their potential implications for consumers’ food decision processes. Sustainability, 14(1), 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010271

- Figuié, M., & Moustier, P. (2009). Market appeal in an emerging economy: Supermarkets and poor consumers in Vietnam. Food Policy, 34(2), 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2008.10.012

- Firmansyah, F., Lubis, T. A., & Ningsih, M. (2022). Hedonic and utilitarian value in the food truck business: A qualitative perspective. Journal of Business Studies and Management Review (JBSMR), 5(2), 221–225. https://doi.org/10.22437/jbsmr.v5i2.18640

- Fitzgerald, A., Heary, C., Nixon, E., & Kelly, C. (2010). Factors influencing the food choices of Irish children and adolescents: A qualitative investigation. Health Promotion International, 25(3), 289–298. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daq021

- Friesdorf, R., Conway, P., & Gawronski, B. (2015). Gender differences in responses to moral dilemmas: A process dissociation analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(5), 696–713. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167215575731

- Fuljahn, A., & Moosmayer, D. C. (2011). The myth of guilt: A replication study on the suitability of hedonic and utilitarian products for cause-related marketing campaigns in Germany. International Journal of Business Research, 85–92.

- Gallarza, M. G., Gil-Saura, I., & Holbrook, M. B. (2011). Value of value: Further excursions on the meaning and role of consumer value. Journal of Consumer Behavior, 10(4), 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.328

- Graf, A., & Maas, P. (2008). Customer value from a customer perspective: A comprehensive Review. Journal für Betriebswirtschaft, 58(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-008-0032-8

- Grunert, K. G. (1993). Toward the concept of food-related lifestyles. Appetite, 21(2), 151–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/0195-6663(93)90007-7

- Grunert, K. G. (2002). Current issues in understanding consumer food choices. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 13(8), 275–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0924-2244(02)00137-1

- Grunert, K. G. (2011). Sustainability in the food sector: A consumer behavior perspective. International Journal of Food System Dynamics, 2(3), 207–218. https://doi.org/10.18461/ijfsd.v2i3.232

- Hawkes, C. (2008). Dietary implications of supermarket development: A global perspective. Development Policy Review, 26(6), 657–692. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2008.00428.x

- Hodson, G., & Earle, M. (2020). Social identity theory (SIT). In V. Zeigler-Hill & T. K. Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24612-3_1185

- Hough, G., & Sosa, M. (2015). Food choice in low-income populations–A review. Food Quality and Preference, 40, 334–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2014.05.003

- Izquierdo-Yusta, A., Gómez-Cantó, C. M., Martínez-Ruiz, M. P., & Pérez-Villarreal, H. H. (2020). Influence of food value on post-purchase variables in food establishments. British Food Journal, 122(7), 2061–2076. https://doi.org/10.1108/bfj-06-2019-0420

- Izquierdo-Yusta, A., Gómez-Cantó, C. M., Pelegrin-Borondo, J., & Martínez-Ruiz, M. P. (2019). Consumer behavior in fast-food restaurants: A food value perspective from Spain. British Food Journal, 121(2), 386–399. https://doi.org/10.1108/bfj-01-2018-0059

- Jaeger, S. R., Bava, C. M., Worch, T., Dawson, J., & Marshall, D. W. (2011). Food-choice kaleidoscope. Framework for the structured description of products, places, and people as sources of variation in food choices. Appetite, 56(2), 412–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2011.01.012

- Kell, K. P., Judd, S. E., Pearson, K. E., Shikany, J. M., & Fernández, J. R. (2015). Association between socioeconomic status and dietary patterns in American black and white adults. British Journal of Nutrition, 113(11), 1792–1799. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114515000938

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS). (2020). Available at: https://knoema.com/atlas/sources/KNBS

- Kenyan Wall Street. (2021). Kenya’s economy to grow fastest in Africa in 2021. Available at https://kenyanwallstreet.com/kenyas-economy-to-grow-fastest-in-africa-in-2021-world-bank/

- Kimenyi, M. S., & Kibe, J. (2014). Africa’s Powerhouse. Retrieved August 3, 2022, from https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/africas-powerhouse/

- Koschate-Fischer, N., Hoyer, W. D., Stokburger-Sauer, N. E., & Engling, J. (2018). Do life events always lead to purchase changes? Mediating role of change in consumer innovativeness, variety-seeking tendencies, and price consciousness. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46(3), 516–536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0548-3

- Kroshus, E. (2008). Gender, marital status, and commercially prepared food expenditure. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 40(6), 355–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2008.05.012

- Le, T. T., Jin, R., Mazenda, A., Sari, N. P. W. P., Tristiana, D., Nguyen, M. H., & Vuong, Q. H. (2023). How educational attainment and custom-based food choice affect health considerations in food consumption. OSF. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/drx76

- Lindgreen, A., & Wynstra, F. (2005). Value in business markets: What do we know? Where are we going? Industrial Marketing Management, 34(7), 732–748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2005.01.001

- Lister, G., Tonsor, G., Brix, M., Schroeder, T., & Yang, C. (2014). Food value applied to livestock products. Working Paper, available at https://www.agmanager.info/livestock/marketing/WorkingPapers/WP1_FoodValues-LivestockProducts.pdf.

- Lusk, J. L., & Briggeman, B. C. (2009). Food values. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 91(1), 184–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8276.2008.01175.x

- Maehle, N., Iversen, N., Hem, L., & Otnes, C. (2015). Exploring consumer preferences for hedonic and utilitarian food attributes. British Food Journal, 117(12), 3039–3063. https://doi.org/10.1108/bfj-04-2015-0148

- Martinez-Ruiz, M. P., & Gomez-Canto, C. (2016). Key external influences affecting consumers’ decisions regarding food. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1618. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01618

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50 (4), 370–96.

- Maslow, A. H. (1996). Critique of self-actualization theory. In Hoffman, E. (Ed.). Future visions: The unpublished papers of Abraham Maslow (pp. 26–32). Sage.

- McFarlane, D. A. (2013). The strategic importance of customer value. Atlantic Marketing Journal, 2(1), 5. https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/amj/vol2/iss1/5

- Melé, D. (2009). Business Ethics in Action. Seeking Human Excellence in Organizations. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Menard, S. (2002). Applied logistic regression analysis (no. 106). Sage.

- Meyer-Rochow, V. B. (2009). Food taboos: Origin and purpose. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-5-18

- Ngugi, R. W., Mwangi, W., & Apollos, M. F. (2018). Role of sociocultural factors in food choices among households in Kiambaa sub-County, Kenya. International Journal of Research in Education and Social Sciences (IJRESS), 1(1), 64–81.

- Ni, M. C., Eyles, H., Schilling, C., Yang, Q., Kaye-Blake, W., Genç, M., Blakely, T., & Zhang, H. (2013). Food prices and consumer demand: Differences across income levels and ethnic groups. PLoS ONE, 8(10), e75934. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0075934

- Ogbo, A., Ugwu, C. C., Enemuo, J., & Ukpere, W. I. (2019). E-commerce is a strategy for sustainable value creation among selected traditional open market retailers in Enugu state, Nigeria. Sustainability, 11(16), 4360. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164360

- Ogundijo, D. A., Tas, A. A., & Onarinde, B. A. (2021). Exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the eating and purchasing behaviors of people living in England. Nutrients, 13(5), 1499. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13051499

- Parvin, S., Wang, P., Uddin, J., & Wright, L. T. (2016). Using best-worst scaling method to examine consumers’ value preferences: A multidimensional perspective. Cogent Business & Management, 3(1), 1199110. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2016.1199110

- Pearson, D., Henryks, J., Trott, A., Jones, P., Parker, G., Dumaresq, D., & Dyball, R. (2011). Local food: Understanding consumer motivations in innovative retail formats. British Food Journal, 113(7), 886–899. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070701111148414

- Pechey, R., Jebb, S. A., Kelly, M. P., Almiron-Roig, E., Conde, S., Nakamura, R., Shemilt, I., Suhrcke, M., & Marteau, T. M. (2013). Socioeconomic differences in purchases of more versus less healthy foods and beverages: Analysis of over 25,000 British households in 2010. Social Science & Medicine, 92, 22–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.05.012

- Peñaloza, V., Lopes Ferreira de Souza, L., Gerhard, F., & Denegri, M. (2017). Exploring utilitarian and hedonic aspects of consumption at the bottom of pyramid. Revista Brasileira de Marketing, 16(3), 268–280. https://doi.org/10.5585/remark.v16i3.3517