Abstract

Underutilized crops play an important role in sustainable food systems, especially in drought-stricken areas occasioned by climate change. These crops, particularly cassava have become a priority in Siaya County, Kenya. This is because of its adaptive nature in the region and its contribution to sustainable food systems. Therefore, both the government and other development bodies have initiated programs to support the development of the cassava value chain while introducing it to mainstream farming systems. Most of these programs have targeted farm-based groups as entry points. However, there is still weak integration between small-scale cassava farmers and development organizations resulting in low performance of the sector. Therefore, this study aims at understanding the framework in which farmer groups are formed and how they are coordinated to link farmers to development organizations. The study adopted a qualitative approach design whereby key informant interviews and focus group discussions were conducted in Siaya County. Data was recorded, transcribed and analysed using ATLAS.ti. software. The results show that most of the farmer groups are just entities sampled together simply because most development organizations use them as entry points. However, there are minimal investments in these groups in terms of capacity development to spearhead cassava value chain development. Notably, most organizations push their agenda through these groups leading to the failure of the programs initiated. Therefore, there is a need to organize the farmer groups into economic entities, sensitize the members on the importance of groups and engage the county agricultural officers when collaborating with development organizations.

1. Introduction

Small-scale farmers are the major players in agricultural production and linkages to other economic segments in Sub-Saharan Africa. In the case of Kenya, smallholder farmers comprise about 80% of agricultural producers at subsistence level and contribute to rural economic development (Kamara et al., Citation2019). Although smallholder farmers play an important role in addressing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of zero hunger and no poverty, the majority of them still focus on major crops such as maize and beans which are vulnerable to climate change. Therefore, there is a need to increase and diversify agricultural production and consider crops such as Cassava (Manihot Esculenta), a food security crop considered important in the Arid and Semi-arid land (ASAL) areas in Africa (Mwebaze et al., Citation2022; Noort et al., Citation2022; Oyetunde et al., Citation2022).

In Kenya, Cassava is a priority crop identified to stimulate agricultural productivity and food security (Florence et al., Citation2017; Githunguri et al., Citation2014; Ouma & Ngala, Citation2021). The crop can serve as a food reserve contributing to the fight against food insecurity in the region (FAO, Citation2013). Efforts to promote the production of drought-tolerant crops such as cassava, have led to development interventions by the government, companies and development organizations. These organizations are acknowledged to play a critical role in stimulating agricultural growth in rural areas (Shiferaw et al., Citation2011). However, they cannot operate in isolation without collaborating with the other actors along the agricultural value chain.

According to Kaplinsky and Morris (Citation2000), the value chain comprises a range of activities and services required to bring a product or service right from production to the end users. As the product moves from one player in the chain to another, it is assumed to gain value (Hellin & Meijer, Citation2006; Porter, Citation1985). In the context of agriculture, the value chain is a framework for understanding the flow of activities and the players involved right from input supply to marketing of agricultural products. A typical value chain involves activities such as input provision, production, processing, marketing and consumption. Actors along the agricultural value chain can strengthen their interactions and engagements through partnerships. Furthermore, the fight against rural poverty through the promotion of agricultural development requires a collective approach (Fischer & Qaim, Citation2012; Kalra et al., Citation2013).

A multi-stakeholder is one of the increasingly used approaches to transforming agricultural value chains. This approach can take various forms and dimensions including the use of farmer groups. These are individual farmers who pull together to accomplish a common purpose by undertaking a common action (Kimaiyo et al., Citation2017). Farmer groups are some of the pro-poor development approaches that have been used to promote development within the agricultural food systems (Pelimina & Justin, Citation2015). Moreover, they have been very instrumental in enhancing agricultural value chain performance. The formation of farmer groups is particularly a common practice among small-scale farmers in rural areas in Kenya motivated by various incentives (Fischer & Qaim, Citation2012). For instance, some groups are formed to achieve social goals while others are for economic benefits. Importantly, groups are meant to incorporate farmers into the economic mainstream since they provide vital services to farmers as well as offer pathways through which organizations can implement programmes and channel relevant support to smallholder farmers (Shiferaw & Muricho, Citation2011). The existence of farmer groups has promoted ted integration of development organizations into the cassava value chain. While some studies have emphasized the establishment of a farm-based group to promote the development of agricultural value chains (Magreta et al., Citation2010; Mwaura, Citation2014; Pelimina & Justin, Citation2015), many of them have not attempted to establish the role of the groups in integrating development organizations into cassava the value chain. Although we find that, these organizations provide mixed services to rural farmers.

In Kenya, development organizations such as Non-governmental Organizations (NGOs) have provided numerous services to the agricultural sector. Most of them have been committed to promoting agricultural technologies among rural farmers (Goldberger, Citation2007; Ndungu et al., Citation2005). For instance, in Kilifi County, CAST Kenya through the Agricultural Sector Development Support Programme, has reached out to many cassava farmers in promoting appropriate integrated cassava techniques that can enhance productivity. Self Help Africa has collaborated with smallholder farmers from the Coastal, Eastern and Western regions in the development of cassava value chains. The organization has tried to integrate farmers into the cassava value chain through training on value addition, good agricultural practices and climate-smart agriculture. In Siaya County, Red Cross has collaborated with farmers to implement cassava-related programs (Opondo et al., Citation2022). Unfortunately, most of these programs have been unsustainable. A good example is the Siaya case where cassava-processing factories, which were established by the organization in Alego-Usonga and Ugenya sub-counties, are no longer operational. The factories were handed over to farmer groups which are experiencing major challenges such as poor management, lack of cohesion within the farmer groups and attitude of the farmers towards the project.

There are numerous roles that farmer-based groups can play. Groups play vital roles especially in reducing transaction costs, facilitating the exchange of information and adopting technology. Furthermore, they are very instrumental in accessing farm inputs and credit facilities at a low cost. Notably, they are noble vehicles for both the government and other development organizations to implement agricultural development programs (Pelimina & Justin, Citation2015). It is important to understand the rationale behind the formation of farm-based groups and their potential as institutional vehicles to drive the integration between smallholder farmers and development organizations into the cassava value chains. In addition, understanding how groups can be used to ensure maximum benefits for small-scale farmers and development organizations from the cassava value chain is paramount.

Even though farmer-based groups, play a crucial role in the development of agricultural value chains, there is no evidence to show how the partnership efforts with development organizations have benefitted smallholder farmers, what inspires the formation of farm-based groups and how they have contributed to an integrated cassava value chain in Siaya County. Cassava is an underutilized crop that is gaining prominence in the wake of climate change, different parties are interested in farmers diversifying into its’ production and commercialization, especially through group networks. In regards to collaborations with development organizations, the existence of these groups has not yielded the desired results in the County since the majority of the projects initiated by the organizations have stalled (Opondo et al., Citation2017). Therefore, the primary objective of this paper was to understand the dynamics behind group formation by cassava farmers in Siaya County, Kenya and how those groups have contributed to integrating smallholder farmers and development organizations into cassava value chains. Specifically, we established the benefits of forming cassava farmer groups and their contribution to enhancing integration between farmers and development organizations into cassava value chains as well as existing policies that promote the integration.

The paper is organized by sub-sections. In section 2, we discuss the concepts related to farmer-based groups. Section 3 presents data collection and analysis methods while in section 4, we discuss the findings of the study, and lastly in section 5 we present conclusion and policy recommendations.

2. Literature review

2.1. Cassava development programmes in Kenya

Climate change is an emerging phenomenon that has contributed to the slow growth of the agricultural sector in Kenya. This is coupled with the increase in population especially among the rural dwellers. According to the Kenya census 2019, the Kenyan population grew from 37.7 Million in 2009 to 47.6 Million in 2019 (KNBS, Citation2019). The increase in figures reveals that food production must be increased to sustain the increased population. Following these developments, the Kenyan government has established strategies aimed at accelerating agricultural growth. Cassava is one of the target crops that has gained prominence because of its tolerance to harsh climatic conditions. Furthermore, the crop has the potential to address food insecurity, which is a major challenge among rural households. Therefore, several development programs have been initiated by different organizations to promote the production and commercialization of cassava crops. For instance, the national government has outlined a roadmap for the development of the cassava sector in the potential counties and sub-counties mainly in ASAL areas. Amongst the strategies highlighted on the roadmap is the development of partnerships with the private sector and other development organizations. This aims at transforming the cassava sector from a subsistence-oriented to a commercially vibrant sector (CUTS Africa Resource Centre, Citation2020). Other highlights on the roadmap include; the establishment of institutions that can regulate the cassava sector both at the county and national levels and the development of County Agricultural Policies.

Notably, the Kenya Agricultural Livestock and Research Organization (KALRO) has partnered with other international organizations in the multiplication of improved cassava varieties with desired characteristics such as early maturity, high yielding, disease and drought tolerant (MOALF, 2019). Organizations such as Alliance for Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) and Farm Concern International (FCI) have launched cassava commercialization promotion in Kilifi. This has been mainly through the Cassava Village Processing Initiative where farmers have been encouraged to undertake value addition and upscale commercialization. Similarly, in Nakuru County, Kenya, the government in partnership with Egerton University has introduced a cassava development initiative aimed at promoting cassava production and commercialization in the region. In 2018, the Kenya Plant Health Inspectorate Service (KEPHIS) launched the promotion of drought-resistant and fast-maturing crops like cassava in Siaya County. Similarly, the Kenya Red Cross Society initiated an integrated food security and livelihood project in the County where farmers received cassava cuttings and training on management practices. Other projects, which have been spearheaded, include the formation of a countywide cassava farmers’ cooperative and the establishment of a few processing plants in Uranga, Boro and Sega wards. In 2017, European Union (EU), funded a programme on strengthening the competitiveness of the cassava value chain in Kenya. This was implemented in seven counties Siaya being one of them. The program aimed to enhance production and strengthen cassava markets. Furthermore, farmers were to build resilience to climate change as they address the challenge of food insecurity. ice (

2.2. Linkages between farmer groups and development organizations

Farmer groups are some of the dimensions of social capital that are also guided by the concept of collective action. This concept is majorly applicable in rural areas where resources tend to be limited and the only way to strengthen and develop agriculture is through unity. Therefore, groups are drivers through which farmers can collectively pool their limited resources, access information through training and extension services as well as access markets for their products. Furthermore, they are institutional arrangements that connect farmers to markets (Gramzow et al., Citation2018). The main incentive for farmers to join hands and establish farmers’ groups is for economic benefits (Hoa et al., Citation2019). Also, farmer groups act as entry points through which most of the development organizations implement programs and integrate into agricultural value chains (Ochieng et al., Citation2018).

Actors outside the value chain such as development organizations offer support to various activities that lie along the value chain. Development organizations include; International, government, Non-government and community-based organizations. These organizations offer support, which includes; capacity development, research and development, and market linkages among others. Researchers confirm that these organizations have increased interest in partnering with farmer groups as vehicles for channelling support through programs. This is because; partnerships between these organizations and the actors can bridge the linkages within the cassava value chain (Mutyaba et al., Citation2016). The sustainability of farmer groups and programs implemented through them depends on the intentional purpose of both parties. Sometimes these groups are established when the need arises while at times they are established as institutions for transforming the livelihoods of farm households through the accomplishment of certain goals. Therefore, it is important to understand how partnerships between development organizations and farmer groups can facilitate growth within the cassava value chain and whether a collaborative advantage can result from the partnerships.

2.3. Conditions and arrangements for partnership between farmer groups and development organizations

Generally, the interest of development organizations is always different from those of the farmers. According to Seidemann (Citation2011), development organizations struggle to balance their special interests and the interests of other actors within the agricultural value chain. Therefore, striking a balance between these diverse expectations can be an uphill task. The study suggests that an appropriate framework must be put in place to regulate the roles played by various actors. In addition, the capacity development of group members or actors to understand their role in the partnership, rights and how to sustain the activities after the exit of the projects is paramount. McKinsey and Drost (Citation2012) identified some of the conditions that should prevail to have a successful partnership and collaboration between development partners and value chain actors. Their study emphasized trust building, sharing of risks, transparency between the partners, clearly defined roles and contributions from both parties, formalized governance structures, shared decision-making processes, involvement of the actors, formalized goal alignment and the embeddedness of the teams. According to Longo (Citation2016), farmer groups should be identified strategically through mapping and profiling. Key elements such as; inclusiveness, governance transparency, sustainability of the projects or programmes at the end of the exit as well as efficiency and effectiveness of the services and products offered should be considered when developing partnerships. IFAD (Citation2015) on the other hand, identified other enabling factors to a successful partnership. These include; farmer ownership of the programmes, capacity building and ensuring a market pull in establishing markets for products. The study emphasized that if partnership conditions are observed, then farmers will be less exposed to risks and there is a likelihood of sustainability and scalability of farming activities. In trying to understand the status of the cassava sector in Kenya regarding the regulatory frameworks, there is no evidence of research work done to establish whether the programmes initiated by development organizations through farmer groups are guided by some policies or conditions.

A few studies have pointed out the relevance of establishing conditions or guidelines to operationalize activities between group members and organizations as well as other actors within the agricultural value chain. For instance, Shiferaw and Muricho (Citation2011) debated that farmers should be able to defend their interests as well as voice out their opinions in any engagement. They further suggested that group members should have some rights. In that case, there should be some regulatory and legal frameworks to safeguard their rights. In addition, transparency, equality, good leadership and minimal interference from the government should prevail. IFAD (Citation2016) supports the importance of farmer groups in the social and economic empowerment of rural farm households. They argue that the existence of conditions enables other partners to recognize groups as relevant partners, not just beneficiaries. Other studies related to the role of farmer groups in promoting agricultural development in Kenya include (Fischer & Qaim, Citation2012; Kimaiyo et al., Citation2017, Laibuni et al., Citation2016; Mwaura, Citation2014). There are, however, limited studies regarding the cassava value chain, which touches on the modalities of linking farmer groups to development organizations.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study area

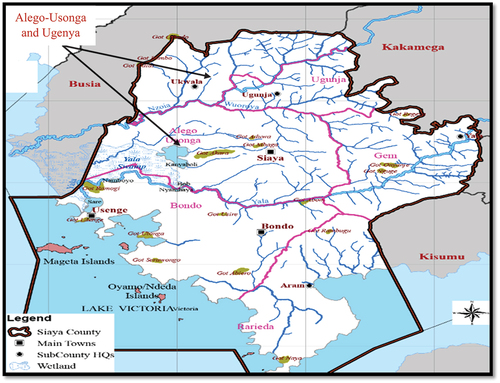

This study was conducted in Alego-Usonga and Ugenya sub-counties in Siaya County, Kenya (Figure ). Siaya County lies between latitude 0° 26’ South to 0° 18’ North and longitude 33° 58’ and 34° 33’. Alego-Usonga and Ugenya sub-counties cover 599 km2 and 324 km2, respectively, 36.48% of Siaya County. Alego-Usonga and Ugenya are inhabited by 224,343 and 134,354 persons, respectively, 36.11% of the Siaya County population (KNBS, Citation2019). Ecologically the two sub-counties spread across diverse agroecological zones including Upper midland (UM1) and low midlands (LM1–5) (Jaetzold & Schmidt, Citation1982).

The altitude lies between 1140 and 1500 meters above sea level. According to Jaetzold and Schmidt (Citation1982), the region has long-term annual temperatures and rainfall ranging from 20.9 to 22.3 0C and 800-2000 mm. Long rains are experienced from March to June and short rains fall from September to December each year, corresponding to a bimodal distribution of rainfall. As a result, there are two full crop seasons every year. Crop and livestock farming are the two sub-counties primary sources of revenue. However, the rainfalls are highly erratic and unpredictable, leading to crop-livestock losses and food insecurity. The main climatic hazards in the study area include dry spells, flooding and heat stress. Most of the smallholder farmers in the area grow orphan crops such as cassava (Manihot esculenta), millet (Panicum miliaceum), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), cowpea (Vigna unguiculata), chickpea (Cicer arietinum) and groundnut (Arachis hypogea). They also grow food crops such as common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) and maize (Zea mays). The predominant livestock reared include goats, sheep, cattle and poultry. Fishing is a joint economic activity in the study area (Musafiri et al., Citation2022)

3.2. Study design and data collection

The study applied a qualitative data collection method. A qualitative method was considered more suitable than a quantitative one as it allowed in-depth scrutiny of the research phenomenon rather than focusing on statistics. Key informant interviews and group discussion techniques were applied in data collection. Key informants were selected using a purposeful sampling technique. The process was limited to agricultural officers, cassava farmers, traders and consumers. A key informant assisted in identifying and recruiting the participants. The participants who were identified had an experience of more than three years in the cassava sector. The concept of data saturation is used to determine the sample size for qualitative data collection projects such as grounded theory, phenomenology, ethnography, and multiple case studies (Strang, Citation2015). Until no new concepts are revealed by the outcomes, the participants are selected dynamically. Although 10 is frequently adopted as the standard for qualitative data collection size, the generally acceptable sample size for qualitative data collection studies ranges from 1 to 20 (Strang, Citation2015). Similarly, Guest et al. (Citation2017) found that more than 80% of all themes were discoverable within two to three focus group discussions. Therefore, in our study, ten and twelve participants represented Alego-usonga and Ugenya sub-respectively as the respondents. While two sub-county agricultural officers were engaged in a group discussion (See Table ). At the beginning of the interviews and discussions, the interviewer explained the objective of the study and shed more light on the importance of full participation in the study and the relevance of the study to the areas. For ethical considerations, the participants were requested to sign a consent form. This was done after seeking consent from the participants and just before the interviews. An interview guide was used to direct the interviews. A tape recorder was used to record the interviews and discussions. Additionally, a research assistant also took notes during the interviews.

Table 1. Summary of distribution of study participants

3.3. Data analysis

The audio transcripts recorded during the interviews were transcribed verbatim by the researchers. The researchers checked the transcripts for quality against the original recordings and against the field notes for accuracy. These transcripts were then uploaded on ATLAS. ti 8.1 for Windows software for analysis. The ATLAS.ti software is a graphical tool that can create networks between codes and themes and shows the interconnectivity between them, as well as identifying the source (what stakeholders, and when) of the themes (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The graphical illustration through the network of linkages enables different kinds of exploration, such as the relationships between themes, codes and quotations and research questions. The network platform in ATLAS. ti facilitates visualization and the exploration of answers to the set research questions in creative and systematic ways (Friese, Citation2019). Using a coding process, both deductive and inductive, thematic areas were identified and guided by the interview questions and objectives of the study. Content analysis was performed and a list of codes and quotations were generated. This method makes it possible to recognise patterns, discover connections, and organise the data into coherent categories (Sekaran & Bougie, Citation2016). Thereafter, we generated a report that guided the review and write-up. Data was presented in tables, charts, networks and cloud forms. Select verbatim quotations have been included in the text as exemplars of subthemes.

4. Results and discussion

This section presents and discusses the findings of the study. The findings were categorised into four themes identified during the analysis. These themes include the rationale behind the formation of cassava farmers-based groups, the rights of members in the operation of farming activities, the contribution of farmer groups to integrating smallholder farmers and development organizations into cassava value chains, and policies that can promote integration between farmer groups and development organizations.

4.1. The rationale behind the formation of cassava farmers-based groups

The interviews and discussions touched on the formation of farmer-based groups, and how farmers organize themselves into groups. It is evident from the study that farmers have realized that they cannot undertake agricultural commercialization individually not unless they operate as a group. Alene et al. (Citation2013) reported that social capital, mostly in the form of groups, especially in rural areas, is used for mutual aid around the globe. Most farmers are proactive in wanting to form groups without being driven by other demands. However, this is yet to be realized as most of the groups formed, are pegged on programs that are being implemented by development organizations and they want farmers to benefit as groups. One of the respondents cited an example of a program on “njaa marufuku” Which is all about ending poverty through a community participatory approach. The program targeted farmers who are organized in groups since it was meant to empower groups to engage in agricultural development initiatives. Therefore, most farmers came together, registered groups and presented their papers to benefit from the initiative. It is in this vein that most cassava-based farmer groups are formed. The formation of such groups does not have a proper foundation. Such groups are not entities that can spearhead development since most of them are formed as institutions for short-term benefits. This is something that was observed among the cassava farmers within Ugenya and Alego-Usonga sub-counties. One of the agricultural officers echoed the following:

There must be a need to educate farmers on group formation even before they embark on the enterprise that lies ahead. Ambushing farmers and directing them towards an idea is a serious weakness of group formation.

Another farmer participant from Ugenya acknowledged the importance of organizing cassava farmers in groups. The respondent argued that farmers can voice their concerns when they are united in a group. This is consistent with the findings of Omondi et al. (Citation2023) who recommended affirmative action and the establishment of a support system such as farmer groups, to increase the farmer’s voice in the cassava value chain. Furthermore, working together strengthens the group’s marketing capability and bargaining power. The findings of this study are similar to those of Adong et al. (Citation2012), who noted that farmer groups aim to give farmers access to market and finance information as well as other crucial agricultural information. Additionally, by selling what they produce in quantity, organizations enable farmers to benefit from economies of scale. The farmers, however, reiterated that during group formation, members should agree on a shared vision and objectives of the group and the responsibilities of the members. These views were further confirmed by a statement made by an agricultural officer who echoed that “Group members must understand why they come together. The entry point is to invest a lot in organizing the farmers to understand what it means to form a group since it is not just about coming together but they should be sensitized on group operations” The officer pointed out that in Siaya County, most of the farmer groups are just entities which are sampled together because many development organizations like to work with groups as entry points to development activities. In addition, organizations feel that when they work with farmer groups, the activities are most likely to be sustainable unlike when they deal with individual farmers. It is, however, important that at the formation stage, farmers should be guided by field agents or promoters to get the groups started. Capacity building and strengthening are some of the activities that should be undertaken to support the proper management of farmer groups. Therefore, the motivation behind the formation of farmer groups should be communicated to the members as well as organizations willing to partner with farmer groups. The finding is consistent with a study conducted by Magreta et al. (Citation2010) which recommended that farmer groups should articulate the need for group establishment and the benefits offered by the groups as prerequisite conditions to group formation. Agricultural officers feel that there is more to be done in the development of sustainable groups as quoted by one of the officers “Forming a group is not like saying I want cassava farmers; how many are willing? Give me your names and then you finally form a group of cassava farmers. No … it starts from serious sensitization over whatever enterprise you plan to engage in. You must talk about what cassava is all about, how it can give money and what you must be prepared to do as a farmer to commercialize activities”

Therefore, farmers must clearly understand from the onset the specific value chain enterprises they are dealing with and the goals that they desire to achieve as a group. In this way, group members can find solutions to the challenges hindering operations of activities along the cassava value chain.

4.2. Rights of cassava farmers-based group members in the operation of farming activities

The discussion touched on the context in which the groups are formed including the rights of members in the commitment to group responsibilities. It emerged from the interviews that the rights of the group members are never a priority during the establishment of farmer groups. Ideally, rights should be spelt out in the rules and regulations of the groups. This is never the case as most groups are formed informally without detailed information on the operationalization of the groups. Thompson et al. (Citation2009) identified seven habits of highly effective farmer groups and organizations including clarity of mission, sound governance, strong responsive and accountable leadership, social inclusion and rising of voice, demand-driven and focused service delivery, high technical and managerial capacity and effective engagement with external actors. These habits describe some of the essentials of success in high-performing farmer groups and organizations in Africa and form part of the rules and regulations for their functionality. The rules and governance systems of the group play a key role in shaping the expectation of members about the overall feasibility and gains from collective action (Shiferaw et al., Citation2011). Tallam (Citation2018) notes that the success of collective action is a function of individual members’ motivation to contribute to the maintenance and abiding by the rules and regulations of the farmer group. Similarly, Mwambi et al. (Citation2020), highlighted that group members’ participation in decision-making promotes accountability and improves the performance of the farmer group.

Subsequently, drawing from the human rights framework, development organizations should consult members of the farmer groups while lobbying for partnerships. Farmers should be able to defend their interests and the binding agreements must be well-articulated especially when the development organizations approach the groups and front their interests. Similarly, there should be a representation of the group members’ interests. One of the participants quoted a scenario that has dampened their spirits to partner with development organizations and companies.

Sometimes back there were some people who came from Kisumu to train farmers on cassava farming and they even brought the cuttings and trained farmers on how to plant them. They further promised farmers that once the yields are ready, they will tell them when to harvest and then collect the harvests from farmers for marketing. When the cassava was ready, they were nowhere to be seen again and farmers who showed interest and planted cassava later on lacked a ready market and this demoralized them.

In so doing, both parties are likely to fully participate in the initiated activities and take ownership. This can further contribute to the sustainability of the programs even after the exit of the program initiators. This is consistent with literature that suggests that the functionality of groups is conditioned by the existence of group and member rights that guides the operationalization of group activities (Retnowati & Subarjo, Citation2018). However, farmer participants indicated that in most groups, there is very little or no participation of group members in the partnership negotiations and discussions. They are only approached for convenience purposes as echoed by one of the officers “When developing partners most organizations want to avoid stress. Therefore, they approach agricultural officers who then call whichever group leaders are available to discuss the initiatives. If you ask us, we know many of those entities who have recruited during the many projects we have worked on. We have those namings of groups already available on the desktop. We simply pull out a file and say that there is group one here, group two there … which one do you want?

The aforementioned statement shows that there is poor engagement of development organizations in identifying the groups of interest to partner with. The approach of engaging the farmers has always been wrong since the identification of the groups is done in an ad-hoc manner. Most of the groups engaged are not genuine and cannot push any serious development agenda. Agricultural officers play a critical role in deciding the groups that should benefit from the initiatives. The study also revealed that farmer-based organizations are sometimes misused by development organizations because they lack proper institutions that can guide their operations. Furthermore, members lack the commitment to the enforcement of the existing informal institutions. These are part of the challenges cited as barriers to integrating farmers and development organizations into the cassava value chain.

4.3. Contribution of farmer groups to integrating smallholder farmers and development organizations into cassava value chains

Farmer groups are known to contribute immensely to strengthening agricultural value chains, especially among smallholder farmers. They provide a space through which farmers can interact with interested parties with development programs (Nalere et al., Citation2015). According to Rahmadanih et al. (Citation2018), the groups play a critical role in establishing collaborations with development organizations and implementing programs that can stimulate agricultural growth. Development organizations may not have a positive influence on strengthening agricultural value chains especially when they try to impose their agenda without involving farmers (Mitlin et al., Citation2007). Therefore, their success relies on the involvement of farmers through farmer groups. From the study, it is revealed that a few organizations have previously visited the county and engaged farmers in promoting cassava production. Most of these organizations worked with cassava farmer groups while others partnered with the local agricultural offices. Some of them provided cassava cuttings while others trained farmers on good agricultural practices. Others have also trained farmers on cassava value-addition opportunities. That being the case, the respondents agreed that when they combine their efforts with development organizations such as NGOs, they can strengthen the cassava value chain further improving the livelihood of cassava farmers within Siaya County. Kalra et al. (Citation2013) stated that participation through farmer groups is a vital strategy to connect with other organizations. They however cautioned farmer groups not to wait to be approached by development organizations. Instead, they should be proactive and adopt a demand-driven model. This means that the groups should respond to the needs of their members by developing contacts and links with development organizations.

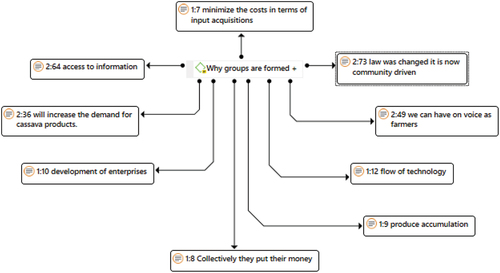

Participants from the Ugenya sub-county highlighted the contributions of farmer groups to the development of the cassava value chain as summarized in Figure . The responses indicate that the benefits include; access to information, market access, flow of technology, minimization of transaction and input costs, development of enterprises, and production accumulation to meet the market demand and to collectively voice their concerns. The respondents acknowledged the importance of partnering with development organizations in the commitment to enjoy these benefits. Their services are essential for improving cassava value chain operations. This was echoed in a statement made by one of the respondents.

As cassava farmers if we can work closely with organizations that can provide us with cassava cuttings, then many of us will embrace cassava farming here in Siaya County.

The findings are in line with those of Acheampong et al. (Citation2022) who confirmed the significance of group membership in determining the adoption and impact of cassava variety. Group membership engenders information flow and thus encourages farmers to join can reduce information barriers in cassava value chains.

Although farmers are aware of the benefits highlighted in Figure , most cassava farmer groups play a minimal role in the enjoyment of the aforementioned benefits. Instead, we find that there are negative outcomes arising from the groups. For instance, in the Ugenya sub-county, the respondents stated that most of the groups have political orientations and are driven by a few individuals with vested interests. Furthermore, the founding members feel that they have ownership of the groups and are therefore entitled to most of the benefits and decision-making processes. The study also established that some of the group officials act as brokers between development organizations and farmer groups. This implies that members are in most cases never consulted before engaging in partnerships with the development organizations. Leastwise, only a section of the members who are close to the officials are involved in decision-making while the rest are mobilized to participate in the programs or projects at a later stage. These challenges inhibit the successful delivery of services offered by development organizations as mentioned by one of the farmers.

The core problem we have here as a community which has resulted into the failure of key development of projects amongst farmer groups as a whole is political negativity towards development by the farmers and some group leaders.

Previously, some organizations could channel their assistance through local administrative offices such as chiefs ’offices. Seemingly, some of the support did not trickle down to farmers who were in dire need of support. For instance, in the Ugenya sub-county, an NGO supplied cassava cuttings to the chief’s camp to be distributed among farmers. The cuttings ended up drying at the chief’s camp and farmers never benefitted from them as intended by the organization. In cases where the cuttings were distributed, only a few selected farmers received the planting materials.

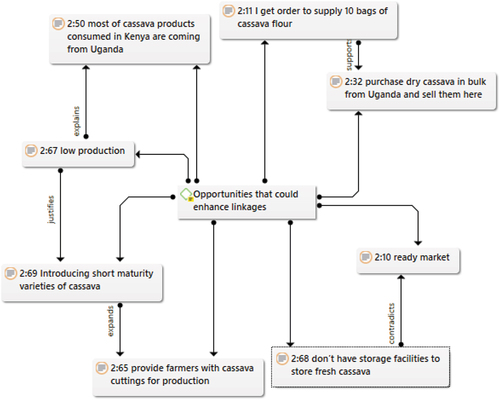

From the interviews, it emerged that there are limitless opportunities that could lead to integration as shown in Figure . One major area that stood out is promoting the use of new cassava varieties as echoed in the statement “Lack of quality cassava cuttings is the major problem that most of us are facing. Most farmers are nowadays trying to plant cassava using the locally available cuttings which does not improve productivity”.

Therefore, institutions such as farmer groups can be platforms through which research institutions and other agricultural organizations can distribute the desired cassava varieties hence improving production. Other opportunities include; the availability of cassava markets both at the local and international markets, lack of storage facilities necessitating the need for value addition and demand for value-added cassava products.

4.4. Policies that can promote integration between farmer groups and development organizations

Trust between group members and partner organizations was found to be an important driving force in partnership. The participants highlighted that interaction between the farmer groups and development organizations should be governed by trust. Some of the farmers have been hesitant to be part of the programs unveiled by these organizations since they do not trust the organizations. There are cases whereby farmers have been engaged in cassava production and during the harvest period the promises are never honoured by the partner organizations. Since most of the linkages and partnerships in joint programs are normally characterized by informal relationships, both parties rely mostly on trust and reciprocal exchange of information and favours. Occasionally, they document some of the agreements for future reference but this mostly happens in cases where the group officials are organized. Generally, the interactions involve informal contacts as opposed to formal relationships. While Shiferaw and Muricho (Citation2011) argue that there is a need for enabling frameworks and institutions such as trust for proper interactions and governance of partnerships between farmer groups and development partners. Gyau et al. (Citation2012) recognize that a well-structured farmer group should at least be registered with the local authorities and if possible, should have some legal status. This recognition is consistent with literature from other studies including (IFAD, Citation2018; Shiferaw & Muricho, Citation2011). Therefore, cassava farmers and agricultural officers from Siaya County need to work around establishing solid frameworks for connecting with interested development parties in transforming the cassava value chain. A participant agricultural officer had the following suggestion regarding proper structuring of the groups” Groups must be reorganized to become functional entities guided by some regulations. The group leaders can organize meetings at the sub-location where they can constitute a basic framework for managing groups and developing linkages with development partners. The Department of Agriculture is mandated to oversee the process of group formation as well as being the custodian of the binding documents”.

In the above statement, we realize that agricultural officers should be at the forefront to reinforce the integration and interaction between farmer groups and development organizations. They should ensure that partnering organizations must have proper exit strategies in cases where the programs/projects are short-term. The officers should make follow-ups to ensure the sustainability of the initiatives. Additionally, they should create transparency and accountability platforms that can enable the participation of group members and development partners. Such platforms could enhance cohesiveness between the partners further strengthening their relationship. The findings suggest that at the moment, there are no clearly defined policies at the agricultural county and sub-county offices that could promote linkages between farmer groups and development partners. It is, however, important to note that while developing policies that could strengthen integration between farmers’ groups and development organizations, emphasis should be placed on a win-win institutional arrangement. This is because some farmers claim that most development organizations are “exploiters”. Such an attitude has dampened the spirit of most cassava farmers in partnering with development organizations.

5. Conclusion and policy recommendations

Cassava farmers continue to face numerous challenges in their day-to-day operational activities in Siaya County. Cassava is a drought-tolerant crop, and can produce a safety net during times of food scarcity. Numerous challenges inhibit the growth of cassava value chains including; access to improved cassava cuttings, minimal value addition activities access to markets and extension services. This has stimulated the need for farmers through their groups to establish strong linkages with development partners. Therefore, these gaps provide entry points for organizations to partner with cassava farmers in the development and strengthening of cassava value chains. The qualitative study sought to provide an understanding of the framework in which cassava farmer groups are formed and how farmer groups have contributed to integrating smallholder farmers and development organizations into cassava value chains

The results of this study reveal that the formation of most cassava farmer groups farmers do not have a proper foundation since most of them lack proper rules and regulations that can guide their operations. Furthermore, most of the groups are not entities that can spearhead development since they are formed for short-term benefits. There are cases where farmer groups have been misused by development organizations because they lack proper institutions that can guide their operations. Notably, there is minimal linkage between cassava farmer groups and development organizations within Siaya County. This is evidenced by the stalled projects that were initiated by partnerships between farmer groups and development organizations. For instance, in Alego-Usonga, Red Cross Kenya established a cassava processing plant for value addition. Similarly, in Sega and Boro, there are stalled projects on cassava value addition which were initiated by development organizations. Hence, most of the partnerships between cassava farmer groups and development organizations are short-lived and lack sound structures and policies in place could frustrate efforts to integrate farmer groups and development organizations. Thus, development organizations need to undertake an in-depth examination of how farmer groups are formed, led, organized, run, interact, and how they spread technology. To improve the welfare of farmers, promoters of farmer organizations should focus their efforts on ensuring that the approach for increasing production is effective. Failure to implement such a measure could lead farmers to have a negative perception of the collective approach. A negative view of the group approach will not only deter further farmers from joining but will also result in a decline in membership.

Farmers have also shown little willingness to partner with organizations such as NGOs in developing agricultural value chains. This attitude has been developed due to mistrust and a lack of transparency and accountability. Farmers are aware of the benefits that accrue from partnering with development organizations. However, they feel that sometimes such collaborations only benefit a few farmers and the organizations’ interests. They feel that for the lineages to be sustained, groups should be managed by visionary leaders who have a long-term focus mindset, are transparent in their decisions and are accountable. Group leaders should be proactive in developing partnerships and linkages with other organizations instead of waiting to be approached. Further, we contend that measures encouraging the equal involvement of all members of farmer groups may have wider positive effects on the organization and the participants. We recommend, in light of this, that decision-makers in farmer groups may, wherever feasible, pay attention to the needs and interests of those farmers who might not be able to participate effectively.

From the discussion with farmers, it was clear that agricultural officers have a role to play in the process of group formation and establishing possible linkages between the groups and development organizations. The officers should offer guidance and training to farmers on how to form groups, sustain the activities and link up with potential supporters such as development organizations. Furthermore, they should promote the integration of farmer groups and development organizations with projects in Siaya County by being the custodian of documentation and watchdog to minimize the exploitation of farmer groups by development partners.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Florence Achieng Opondo

Dr. Florence Achieng Opondo holds a PhD in Agribusiness Management from Egerton University, Kenya and is a Lecturer at Laikipia University, Kenya. She was previously a Postdoctoral Fellow with the University of Pretoria’s Future Africa Institute. She has undertaken research work in value chain analysis of food systems, promoting entrepreneurship in agriculture and enterprise development for economic development in Africa.

Poti Owili Abaja

Dr. Poti Owili Abaja is Senior Lecturer at Laikipia University, Kenya. He holds a PhD in Statistics, from Kabarak University, Kenya.

Kevin Okoth Ouko

Dr. Kevin Okoth Ouko is a Research Associate Consultant at WorldFish. He recently completed a PhD in Food Security and Sustainable Agriculture from Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Kenya. He also holds an MSc in Agricultural and Applied Economics from Egerton University, Kenya and the University of Pretoria, South Africa. His research expertise includes food systems, food security, climate change, aquaculture value chains and gender and social inclusions.

References

- Acheampong, P. P., Addison, M., & Wongnaa, C. A. (2022). Assessment of the impact of the adoption of improved cassava varieties on yields in Ghana: An endogenous switching approach. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1), 2008587. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2021.2008587

- Adong, A., Mwaura, F., & Okoboi, G. (2012). What factors determine membership to farmer groups in Uganda? Evidence from the Uganda census of agriculture 2008/9. No. 677-2016-46623. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.148950

- Alene, A., Khonje, M., Mwalughali, J., Chafuwa, C., Longwe, A., Khataza, R., & Chikoye, D. (2013). Baseline characterization of production and markets, technologies and preferences, and livelihoods of smallholder farmers and communities affected by HIV/AIDS in Mozambique. The International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) Southern Africa. https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/80839/U13BkAleneBaselineCharacterizationNothomNodev.pdf

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–16. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- CUTS Africa Resource Centre. (2020). Catalysing Private Sector Investment in Kenya’s Cassava Value Chain. In Review of Catalysing Private Sector Investment in Kenya’s Cassava Value Chain (pp. 1–9). CUTS Africa Resource Centre. https://cuts-nairobi.org/pdf/catalysing-private-sector-investment-in-kenya-cassava-value-chain.pdf

- FAO. (2013). Save and grow cassava: A guide to sustainable production intensification. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

- Fischer, E., & Qaim, M. (2012). Linking smallholders to markets: Determinants and impacts of farmer collective action in Kenya. World Development, 40(6), 1255–1268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.11.018

- Florence, A. O., Peter, D., & Maximilian, W. (2017). Characterization of the levels of cassava commercialization among smallholder farmers in Kenya: A multinomial regression approach. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 12(41), 3024–3036. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR2017.12634

- Friese, S. (2019). Qualitative data analysis with ATLAS. ti. Qualitative Data Analysis with ATLAS, 1–344. https://www.torrossa.com/en/resources/an/5018383

- Githunguri, C. M., Amata, R., Lung’ahi, E. G., & Musili, R. (2014). Cassava: A promising food security crop in Mutomo, a semi-arid food deficit district in Kitui County of Kenya. International Journal of Agricultural Resources, Governance and Ecology, 10(3), 311–323. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJARGE.2014.064002

- Goldberger, J. R. (2007). Non-governmental organizations, strategic bridge building, and the “conscientization” of organic agriculture in Kenya. Agriculture and Human Values, 25(2), 271–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-007-9098-5

- Gramzow, A., Batt, P. J., Afari-Sefa, V., Petrick, M., & Roothaert, R. (2018). Linking smallholder vegetable producers to the markets-A comparison of a vegetable producer group and a contract-farming arrangement in the Lushoto District of Tanzania. Journal of Rural Studies, 63, 168–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.07.011

- Guest, G., Namey, E., & McKenna, K. (2017). How many focus groups are enough? Building an evidence base for nonprobability sample sizes. Field Methods, 29(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X16639015

- Gyau, A. Takoutsing, B. & Franzel, S.(2012). Producers' Perception of Collective Action Initiatives in the production and marketing of Kola in Cameroon. The Journal of Agricultural Science, 4(4), 117. https://doi.org/10.5539/jas.v4n4p117

- Hellin, J., & Meijer, M. (2006). Guidelines for value chain analysis. In Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). http://www.spiencambodia.com/filelibrary/Value_Chain_Research_Methodology.pdf

- Hoa, A. X., Techato, K., Dong, L. K., Vuong, V. T., & Sopin, J. (2019). Advancing smallholders’sustainable livelihood through linkages among stakeholders in the cassava (manihot esculenta crantz) value chain: the case of dak lak province, vietnam. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research, 17(2). https://aloki.hu/pdf/1702_51935217.pdf

- IFAD. (2015) . Brokering development - enabling factors for public-private-producer partnerships in agricultural value chains. Institute of Development Studies.

- IFAD. (2018). Farmers organizations in Africa Programme (SFOAP)- main phase 2013- 2018. International Fund for Agricultural Development.

- Jaetzold, R., & Schmidt, H. (1982). Farm management handbook of Kenya (no. 630.96762 JAE v. 2. CIMMYT). Ministry of Agriculture, Kenya, in Cooperation with the German Agricultural Team (GAT) of the German Agency for Technical Cooperation (GTZ). https://edepot.wur.nl/487562

- Kalra, R. K. (2013). Self-help groups in Indian Agriculture: A case study of farmer groups in Punjab, Northern India. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems, 37(5), 509–530. https://doi.org/10.1080/10440046.2012.719853

- Kamara, A., Conteh, A., Rhodes, E. R., & Cooke, R. A. (2019). The relevance of smallholder farming to African agricultural growth and development. African Journal of Food Agriculture Nutrition & Development, 19(1), 14043–14065. https://doi.org/10.18697/ajfand.84.BLFB1010

- Kaplinsky, R., & Morris, M. (2000). A handbook for value chain research (Vol. 113). University of Sussex, Institute of Development Studies.

- Kimaiyo, J. C., Bourne, M. S., Tanui, J. K., Oeba, V. O., & Mowo, J. J. (2017). Fostering collective action amongst smallholder farmers in East Africa: Are women members adequately participating? African Journal of Gender and Women Studies ISSN, 2(5), 111–123.

- KNBS. (2019). Kenya population and housing census volume I: Population by County and sub-County. I(2019). https://www.knbs.or.ke/2019-kenya-population-and-housing-census-results/

- Laibuni, N. M. Neubert, S. Bokelmann, W. Gevorgyan, E. & Losenge, T.(2016). Characterizing organisational linkages in the African indigenous vegetable value chains in Kenya. No. 310-2016-5493. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.249345

- Longo, R. (2016). Engaging with farmers’ organizations for more effective smallholder development. International fund for agricultural development (IFAD). http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12018/3027

- Magreta, R. M., Tennyson, & Zingore, S. (2010). When the Weak win: Role of farmer groups in influencing agricultural policy outcome; a case of nkhate irrigation scheme in Malawi. https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/97043/

- McKinsey, & Drost, S. (2012). Key conditions for successful value chain partnerships: A multiple case study in Ethiopia. Netherlands Partnership Resource Centre. http://hdl.handle.net/1765/77626

- Mitlin, D., Hickey, S., & Bebbington, A. (2007). Reclaiming development? NGOs and the challenge of alternatives. World Development, 35(10), 1699–1720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2006.11.005

- Musafiri, C. M., Kiboi, M., Macharia, J., Ng’etich, O. K., Kosgei, D. K., Mulianga, B., Okoti, M., & Ngetich, F. K. (2022). Adoption of climate-smart agricultural practices among smallholder farmers in Western Kenya: Do socioeconomic, institutional, and biophysical factors matter? Heliyon, 8(1), e08677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08677

- Mutyaba, C., Lubinga, M. H., Ogwal, R. O., & Tumwesigye, S. (2016). The role of institutions as actors influencing Uganda’s cassava sector. Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in the Tropics and Subtropics (JARTS), 117(1), 113–123. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:hebis:34-2016020149824

- Mwambi, M., Bijman, J., & Mshenga, P. (2020). Which type of producer organization is (more) inclusive? Dynamics of farmers’ membership and participation in the decision‐making process. Annals of Public & Cooperative Economics, 91(2), 213–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/apce.12269

- Mwaura, F. (2014). Effect of farmer group membership on agricultural Technology adoption and crop productivity in Uganda. African Crop Science Journal, 22(4), 917–927. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/acsj/article/view/108510

- Mwebaze, P., Macfadyen, S., De Barro, P., Bua, A., Kalyebi, A., Tairo, F., & Colvin, J. (2022). Impacts of cassava whitefly pests on the productivity of east and Central African smallholder farmers.

- Nalere, P., Yogo, M. A., & Kenny, O. (2015). The contribution of rural institutions to rural development: Study of smallholder farmer groups and NGOs in Uganda. International NGO Journal, 10(4), 37–51. https://doi.org/10.5897/INGOJ2015.0299

- Ndungu, J. (2005). Non-governmental organizations and agricultural development in the coastal region of Kenya. Eastern Africa Journal of Rural Development, 21(1), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.4314/eajrd.v21i1.28372

- Noort, M. W., Renzetti, S., Linderhof, V., du Rand, G. E., Marx-Pienaar, N. J., de Kock, H. L., Magano, N., & Taylor, J. R. (2022). Towards sustainable shifts to healthy diets and food security in sub-Saharan Africa with climate-resilient crops in bread-type products: A food System analysis. Foods, 11(2), 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11020135

- Ochieng, J., Knerr, B., Owuor, G., & Ouma, E. (2018). Strengthening collective action to improve marketing performance: Evidence from farmer groups in Central Africa. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 24(2), 169–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2018.1432493

- Omondi, S. W., Tana, P., Lutomia, C., Makini, F., & Wasilwa, L. (2023). Exploring inclusiveness of vulnerable and marginalized people in the cassava value chain in the Lake region, Kenya. Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in the Tropics and Subtropics, 124(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.17170/kobra-202302217527

- Opondo, F., Mshenga, P. & Louw, A.(2022). Analysis of Marketing Margins for Cassava Farmers and traders in Siaya County, Kenya. Laikipia University Journal of Social Sciences, Education and Humanities, 1(2).

- Ouma, J. O., & Ngala, S. (2021). Contribution of cassava and cassava-based products to food and nutrition security in Migori County, Kenya. African Journal of Food Agriculture Nutrition & Development, 21(1), 17379–17414. https://doi.org/10.18697/ajfand.96.19975

- Oyetunde, A. K., Kolombia, Y. A., Adewuyi, O., Afolami, S. O., & Coyne, D. (2022). The first report of Meloidogyne enterolobii infecting cassava (Manihot esculenta) resulted in root galling damage in Africa. Plant Disease, 106(5), 1533. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-08-21-1777-PDN

- Pelimina, B. M., & Justin, K. U. (2015). The contribution of farmers organizations to smallholder farmers well-being: A case study of Kasulu district, Tanzania. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 10(23), 2343–2349.

- Porter, M. E. (1985). Technology and competitive advantage. Journal of Business Strategy, 5(3), 60–78. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb039075

- Rahmadanih, B. S., Arsyad, M., Amrullah, A., & Viantika, N. M. (2018). Role of farmer group institutions in increasing farm production and household food security. Proceedings of the Conference series earth and environmental science, 24–25 October 2017, Sulawesi Selatan, Indonesia, 157(1), 012062. IOP Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/157/1/012062

- Retnowati, D., & Subarjo, A. H. (2018). Enhancing the effectiveness of agriculture groups in supporting government programs to increase food security. Journal of Physics Conference Series, 1022, 012040. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1022/1/012040

- Seidemann, S. B. (2011). Actual and potential roles of local NGOs in agricultural development in sub-Saharan Africa. Quarterly Journal of International Agriculture, 50(1), 65–78. https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/155491/

- Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2016). Research methods for business: A skill building approach. John Wiley & Sons.

- Shiferaw, B., Hellin, J., & Muricho, G. (2011). Improving market access and agricultural productivity growth in Africa: What role for producer organizations and collective action institutions? Food Security, 3(4), 475–489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-011-0153-0

- Shiferaw, A. B., & Muricho, G. (2011). Farmer organizations and collective action institutions for improving market access and Technology adoption in sub- Saharan Africa: Review of experiences and implications for policy. Nairobi, International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

- Strang, K. D. (2015). Selecting research techniques for a method and strategy. In The Palgrave handbook of research design in business and management (pp. 63–79). Palgrave Macmillan US. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137484956_5

- Tallam, S. J. (2018). What factors influence the performance of farmer groups? A review of literature on parameters that measure group performance. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 13(23), 1163–1169. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR2017.12205

- Thompson, J., Teshome, A., Hughes, D., Chirwa, E., & Omiti, J. (2009). Farmers’ organisations in Africa: Lessons from Ethiopia, Kenya and Malawi. Ethiopian Economics Association (EEA), 91. https://eea-et.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/7TH_vol-III.pdf#page=100