Abstract

The migration of talents from one country to another has become a growing concern worldwide. It has been argued that the home country’s economic, political, and social push factors drive the intention to migrate among its talents. This study aims to investigate the direct and indirect effects of home country’s economic (financial difficulties, economic instability), political (political instability, corruption), and social (life dissatisfaction, problems of family well-being) push factors on the intention to migrate among medical doctors in Iraq. The indirect effect involves testing the mediating effect of psychological distress in the proposed relationships. This study uses a cross-sectional research design to gather data from a sample of 460 medical doctors working in private and public hospitals in Iraq. The Partial Least Square (PLS) two-step path modelling was used to test the direct and indirect hypotheses. The findings of this study show that financial difficulties and economic instability has a positive direct effect on the intention to migrate. However, the direct effect of political instability, corruption, life dissatisfaction, and problems of family well-being on the intention to migrate is insignificant. Additionally, the direct positive effect of financial difficulties, economic instability, political instability, and corruption on psychological distress is significant. Likewise, the effect of problem of family well-being on psychological distress is also significant, while the effect of life dissatisfaction on psychological distress is not significant. Further, the direct positive effect of psychological distress on intention to migrate is significant. A full mediation effect of psychological distress was found in the relationship between financial difficulties, economic instability, political instability, corruption, problem of family well-being and intention to migrate. The relationships examined in this study offer new directions in the study of migration among talents, specifically among the medical doctors in Iraq. The findings can be used by human resource managers, government agencies, and policymakers to improve the psychological state of medical professionals in Iraq hospitals.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Currently, the global competition for talent is on the rise. This has resulted in more opportunities for talented people to migrate from their home country, especially those less developed ones, to find a better life and career openings in more developed nations (Dao et al., 2018). In the migration literature, several factors have been identified as to why migrants decide to leave their homelands and move to other countries (Efendic, Citation2016; Qin et al., Citation2018). Migration also known as political migration or economic migration (Schaeffer, Citation2010; Walther & Corbin, Citation2018), where people are forced to abandon their homes to escape war or continuous bloodshed and to seek greener pastures (Castelli, Citation2018; Efendic, Citation2016). In recent decades, the migration of healthcare professionals and physicians, in particular, has become a worldwide phenomenon. The magnitude and impact of this phenomenon is illustrated through its description as mass migration that has created a critical global health workforce crisis (Dywili et al., 2012; Schumann, Citation2021). The direction of this migration generally occurs along the wealth gap, i.e., from less-developed to more-developed countries (Schumann, Citation2021). Globally, the main source countries of physicians were South Africa, Ghana, Pakistan, Colombia, Nigeria, India, Iraq, and the Philippines, while the main destination countries included the UK, the USA, Canada, Australia, and Germany (Costigliola, Citation2011; Kopetsch, Citation2009; Labonté et al., Citation2006; Pang et al., Citation2002). Physicians are continuously moving from one country to another that has a perceived higher living standard in what is described as the medical carousel phenomenon (Ncayiyana, Citation1999).

Iraq is not immune to this worldwide phenomenon, as it witness the growing trend of migration among its medical doctors. Its medical field has been one of the hardest hit due to the immense pressure and lack of readiness. Over the past 40 years, Iraq’s multiple conflicts and internal troubles have naturally impacted the country’s healthcare sector, restricting the country’s ability to deal with such emergencies and severe health challenges (Valenciano & Biondi, Citation2003). According to Al-Shawi et al. (Citation2017), between 2004 and 2007, medical staff were subjected to extraordinary conditions of threatening, kidnapping, and assassination following the end of the Iraq war in 2003. As a result, doctors migrated to more stable and safer nations, resulting in talent scarcity. According to Burnham et al. (Citation2009), Iraq has been plagued by financial and administrative corruption since the 2003 war, hampered the development and rehabilitation of the Iraqi healthcare system while also leaving it underfunded. For example, the government allotted only 2.5 percent of the nation’s $106.5 billion budget to the Health Ministry in 2019, hurting healthcare providers pay and a shortage of equipment and medication (Aboulenein & Levinson, Citation2020). According to the World Health Organization, the ratio of nine doctors for every 10,000 people in Iraq are putting immense strain on healthcare workers, especially in a statewide medical catastrophe.

A handful of studies have been conducted to study intention to migrate among Iraqi doctors in comprehending their antecedents and their personal and psychological experience (Jadoo et al., Citation2015). Several past research on talent migration have focused on intention to migrate among youth (Méndez, Citation2020), nurses (Öncü et al., Citation2021), migrants from Latin America (Chindarkar, Citation2014), and a psychological perspective of rural migration in Iran (Yazdan-Panah & Zobeidi, Citation2017). Another research stream focused on factors influencing final-year nursing/midwifery students’ intentions to migrate following graduation (Deasy et al., Citation2021). In a another study, Brugha et al. (Citation2016) studied the reasons why migrant doctors in Ireland plan to stay, return home or migrate onwards to new destination countries. To date, however, there is no comprehensive study that examines the effects of economic, political, and social factors on intention to migrate in Iraqi context. Grounded with psychological distress perspective, which is defined as ‘to non-specific symptoms of stress, anxiety and depression’ (Viertiö et al., Citation2021, p. 2), this study introduces intention to migrate as an essential contribution to migration literature. This study proposes a context in which psychological distress is identified as a critical component of related migration literature that helps in having a comprehensive understanding of intention to migrate.

Through the prism of this framework, we can understand how past studies have indicated that economic push factors, such as weak financial conditions in the home country can influence individuals to migrate (Dodani & LaPorte, Citation2005; Rapoport & Docquier, 2012; Ullah et al., Citation2019;). Many individuals attempt to move and work in countries with better economic conditions (Fong & Hassan, Citation2017). Specifically, Dugger (Citation2005) argued that highly skilled professionals who desire to protect their families from poverty migrate to countries with greater economic development and the provision of higher wages (Fong & Hassan, Citation2017). The main economic push factors are poverty, lack of job opportunities, social advantages and dissatisfaction with the current condition (Kirkwood, Citation2009; Lasocik, Citation2010; Ullah et al., Citation2019).

From the perspective of political factors, this study considers political instability as having a strong impact on migration. It is also the main drive influencing whether to remain or leave a country. The political instability in Iraq has resulted in the massive migration of its citizens (Al-Tamimi, Citation2006; Lafta & Hussain, Citation2018). Furthermore, factors such as clashes between ethnic groups has led to disharmony among the people (Sabti & Ramalu, Citation2020). This phenomenon contributes to migration to other politically stable countries for a more peaceful life. Moreover, contrasting religious beliefs also lead to injustice and the reluctance to accept the minority (Johnson, Citation2008). Political instability also leads to higher crime rates and security issues (Kamimura et al., 2018), thus causing people to migrate to other countries with better security (Saxenian, Citation2005). Given this, we suggest that political instability is linked to intention to migrate, conceptualised as a preference for migration over staying, regardless of the reason (Carling et al., Citation2015).

The social factors leading to migration among professionals are crime, the drop in educational standards, weak country structure, crises in health institutes, and environmental breakdown (Jadoo et al., Citation2018). Similarly, family influences also significantly affect the decision of professionals to leave their country of origin (Mohamed & Abdul-Talib, Citation2020). Furthermore, when a country fails to fulfill the expectations of its people, they would migrate to other countries to achieve better prospects for themselves and their families. This is the starting point of the migration process (Friebel et al., Citation2018). Comparatively, developed countries provide a very high quality of education to the children of migrants (Freitas, Citation2012).

This study proposes that home country (i.e., Iraq) push factors namely economic (financial difficulties and economic instability), political (political instability and corruption), and social factors (life dissatisfaction and problems of family well-being) will influence migration intention among Iraqi doctors, mediated through psychological distress. This study is framed based on Push-Pull Theory of Lee (Citation1966) and Toren (Citation1976). This theory is applied in global migration studies by Bodvarsson and Van den Berg (Citation2009) and De Jong and Fawcett (Citation1981), who concludes that an individual’s environmental background might push them one way and the economic or financial prospects in the developed or destination country can draw them the other way (Van Hear et al., Citation2018). Migration decision could also be influenced by availability of opportunities to venture into business in home and host country (Ruiz-Palomino & Martínez-Cañas, Citation2021). If such opportunities is not available in home country, it can be considered as a one of the push factors that influence decision to migrate and vice verse. Several researchers have draw on Push-Pull Theory (Amit & Muller, Citation1995; Caliendo & Kritikos, Citation2010; Gilad & Levine, Citation1986; Kirkwood, Citation2009; Martínez-Cañas et al., Citation2023; Thurik et al., Citation2008) to argue that push- or pull-related motivations explain how entrepreneurial intention is formed. Various push-pull factors together with perceptual variables, namely, perceived risk and opportunity recognition was associated with entrepreneurship intention in a study conducted by Martínez-Cañas et al. (Citation2023). These studies suggests that Push-Pull Theory generally can be used to study various phenomenon beyond global migration. Additionally, Hobfoll’s (Citation1989) Conservation of Resources (COR) theory provides a valuable insights for understanding the links between workplace stressors, psychological distress, and migration intention.

Our study contributes in three ways to existing literature. First, we offer the study of independent Iraqi doctors who prefer to domicile abroad via a positive perspective and identify psychological distress as a critical migration factor. Secondly, we examine the link between various home country political, economic, and social push factors and intention to migrate. There is sparseness in data-driven research investigating the influence of economic (financial difficulties and economic instability), political (political instability and corruption), and social factors (life dissatisfaction and problems of family well-being) on intention to migrate. Finally, we looked at the role of psychological distress as a mediator concerning political, economic, and social factors and intention to migrate. Whereas the influence of political, economic, and social factors on intention to migrate are widely documented (e.g., Agadjanian & Gorina, Citation2019; Migali & Scipioni, Citation2018; Koczan et al., Citation2021; Wazir et al., Citation2017; Zanabazar et al., Citation2021), researches regarding the interactive effects of psychological distress between political, economic, and social factors and intention to migrate hasn’t been previously investigated.

1.1. Theoretical underpinnings

1.1.1. Push-pull theory

Several theories have been proposed in the past to explain why migration occurs. Migration is viewed as a means of shifting from current poor living situations to better living conditions, which is a natural human tendency for survival. The Dual Labor Market Theory, Neoclassical Migration Theory, Theory of Reasoned Action, and Theory of Planned Behavior are few of the theories often referred in migration studies. Empirical investigations have revealed that comparatively predictable criteria encourage people to leave their home nation and relocate to more developed host countries (Baruch et al., Citation2007). Push and pull influences can coexist, with an individual being pulled both by their environmental background and the economic or financial prospects available in the developed or destination country (Van Hear et al., Citation2018). Push factors have a greater impact on people with professional abilities and work experience (Güngör & Tansel, Citation2008). In present study, the Push-Pull Theory is extended by looking at career, economics, social, and political issues, as well as family and psychological factors in influencing decision to migrate (Laila & Fiaz, Citation2018). Currently, sociological or economic causes dominate migration ideas. Origin-related and intrinsic or intangible migration aspirations are both push factors. The current study interprets the intents of individuals toward migration using the Push-Pull Theory (Toren, Citation1976).

1.1.2. Conservation of resources theory

The Conservation of Resources Theory (COR) is a broad theory that explains why people desire to safeguard, restore, and upgrade their assets and why they feel compelled to do so when they don’t. This theory asserts that humans primarily aim to build, safeguard and nurture their resources to protect themselves and the social bonds that enable such protection. Using the theory, a model is provided for averting the loss of resources, retaining existing resources, and attaining the needed resources that enable proper behavioural engagements including decisions related to migration (Hobfoll, Citation2001). Resource-loss events are likely to cause greater losses, which sometimes occur repetitively. Such events force people to implement resource-conservation strategies, where available resources are used to adapt as efficaciously as possible. Failed coping strategies cause not only material loss, but also psychological distress. Ineffective loss prevention strategies create more resource losses, thus leading to loss spirals (West et al., Citation2018).

2. Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1. Intention to migrate

Intention to migrate refers to a strong manifestation of one’s plan to migrate (Manchin & Orazbayev, Citation2018). Others have defined it as the individual’s desire, plan, and concrete preparation to move abroad (Shariff et al., Citation2018). The intention to migrate reliably indicates the individuals’ expectations of their future in other countries (Ghazali et al., Citation2015). Elangovan (Citation2001) delineated migration intention as an attitudinal orientation or a cognitive manifestation of the behavioral decision to quit. Studies have found that many professionals, particularly doctors migrate from developing countries to work in developed countries. Numerous causes affect the intention to migrate among professionals, including to obtain a higher salary (Ghazali et al., Citation2015). The study of Sabti and Ramalu (Citation2020) examined the effect of home country push factors on professionals’ intention to migrate and concluded that economic, social, and political factors enhance their intention to leave the home country. Meanwhile, the study of Roman et al. (Citation2020) found that the religious beliefs and practices turned out to have a different effect on the motivation of young individuals to migrate. Several researchers have researched employees’ intention to migrate to different contexts, industries, cultures, and countries using other variables. Consequently, the present study is important for all stakeholders namely Iraqi doctors, their host country, and employers. Hence there is a need to further interrogate this stream of thought in the Iraqi doctor’s context.

2.2. Factors contributing to migration among Iraqi doctors

Lack of basic economic prospects, political or religious discrimination, and harmful environmental circumstances are push factors that cause migration (Ninković & Keković, Citation2017). Various researches have concentrated on migration’s political and economic factors (e.g., Efendic, Citation2016; Krasniqi & Williams, Citation2018; Qin et al., Citation2018). Poor social life and political instability are the critical reasons for migration. Generally, push factors like political, social, and environmental instability in the native country cause its people to migrate (Fong & Hassan, Citation2017). Other scholars highlighted migration beyond economic and political motivations and indicated that social and psychological aspects could influence migration decisions (Paparusso & Ambrosetti, Citation2017). These factors have worsened the shortage of healthcare professionals (Lafta & Hussain, Citation2018), and as a result of this has hindered the improvement of the healthcare system in Iraq (Al-Samarrai & Jadoo, Citation2018). The assault on doctors throughout the earlier aggressive regimes in Iraq has caused mental distress among medical professionals (Lafta & Pandya, Citation2006). Likewise, due to the poor security condition, healthcare professionals had no option but to migrate to developed countries (Jadoo et al., Citation2018). All these issues have directed to a declining doctor-patient ratio. A rising rate of hostility in northern and central Iraq made doctors a target of lawsuits (Jadoo et al., Citation2015). In this study, home country push factors that will influence intention to migrate have been grouped into economic (financial difficulties and economic instability), political (political instability and corruption), and social factors (life dissatisfaction and problems of family well-being).

2.2.1. Economic factors

2.2.1.1. Financial difficulties

This study suggests that financial difficulties is a key factor in driving migration intention specifically among the professionals (Cao et al., Citation2016). The authors further argued that when an individual experiences financial difficulties in his/her current country, he/she migrates to another country to secure better financial sources. Similarly, Górecki et al. (Citation2019) also acknowledged that financial difficulties are the main factor of the intent to migrate. Financial difficulty as a push factor causes stress and restlessness (Asakura & Murata, Citation2006). Similarly, Sabti and Ramalu (Citation2020) acknowledged that financial condition as a push factor creates restlessness among employees. Individuals facing financial difficulties are more likely to face chronic and acute stressors such as family and relationship issues, difficulty making monthly payments, physical limitations, and bad neighborhood conditions, to name a few. Such condition will trigger individuals to initiate migration process as part of coping strategies to attain needed resources for survival (Hobfoll, Citation2001).

2.2.1.2. Economic instability

Another variable of economics factors is economy instability. Since anticipated income is the central aspect in employment decision, work prospects and labor market factors at home and abroad could significantly contribute to the expectations of qualified individuals with economic opportunity. The economics factors can decide the relative work prospects and may decrease or raise the projected income of a person accordingly (Hao et al., Citation2016). Dovlo (Citation2003) stated that in the native country, economic instability as one of push factors could force professionals to leave. Low economic stability would drive professionals and academics to leave (Kiang et al., Citation2014). Many descriptive data on key economic indicators indicates that economic performance does influence immigration attitudes, especially in countries that were the most affected by the crisis (Isaksen, Citation2019).

2.2.2. Political factors

2.2.2.1. Political instability

One of the variables of political push factors are political instability. Most studies on politically-driven migration focus on the concept of forced migration i.e., due to deadly circumstances, including war and ethnic cleansing. Political instability is a crucial driver of increased youth migration intention (Elbahnasawy et al., Citation2016). Political instability has become a global phenomenon. Dywili et al. (Citation2012) investigated the factors that influence international nursing migration and discovered that it is linked to political instability. Sabti and Ramalu (Citation2020) investigated the effects of political push factors on professional migration intentions. According to the study, political instability has a significant impact on migration intention. Barra and Ruggiero (Citation2023) emphasized the role of domestic institutions as a push factor of emigration, suggesting that the quality of governance is a key factor in explaining emigrations from poor to rich countries.

2.2.2.2. Corruption

Corruption is defined as behavior which deviates from the normal duties of a public role because of private-regarding (family, close private clique), pecuniary or status gains; or violates rules against the exercise of certain types of private-regarding influence (Bicchieri & Ganegonda, Citation2017). Cooray and Schneider (Citation2016) used the Transparency International Index (TII) and the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) corruption index to measure corruption. It was found that corruption increases in tandem with the increase in the migration rate of highly-skilled workers. Corruption has recently been identified as a major driver of migration, acting on the aspiration of people to migrate to other countries and areas. In particular, it plays a major role in driving highly-educated people away.

2.2.3. Social factors

2.2.3.1. Life dissatisfaction

One of the variables of social factors is life dissatisfaction. Life satisfaction is an aspect of subjective well-being (Busseri, Citation2018; Schimmack et al., Citation2002) and psychological stability (Roberts et al., Citation2002). It predicts negative health consequences (Koivumaa-Honkanen et al., Citation2000), signs of depression (Koivumaa-Honkanen et al., Citation2004), and suicide (Koivumaa-Honkanen et al., Citation2004). The study of Migali and Scipioni (Citation2018) examined the effect of life dissatisfaction on intention to migrate. Their finding indicated a non-linear relationship between migration preparation and individual income. They also reported in their study that dissatisfaction with one’s current standard of living drive the intention to migrate.

2.2.3.2. Problems of family well-being

Problems of family well-being is included in this study to demonstrate how the freedom to attain a better life via migration is fundamental for the venture-making character. Individuals transients themselves, particularly in their basic position as individuals who can move towards migration as a type of use as opposed to the direction of creation ascribed to most other streams of migration (De Haas, 2011). Moen et al. (Citation2016) examined the relationship between family well-being, parents’ psychological state, and children’s behavior. Following socio-demographic and ethnicity adjustments, parents with high well-being scores showed lower risks of psychological distress and had children who are more sociable and less difficult behaviourally compared to those with low well-being scores. Problems of family well-being as a push factor forces people to leave their home country to achieve family welfare and comfort elsewhere (Sunarti et al., Citation2021).

2.3. Psychological distress as a mediating variable

Psychological distress is a negative emotional condition that resembles mental damage, threat, and the loss of a significant aim. Negative emotions are linked to being hostile, annoying, short-tempered, worried, and tense (Mclean et al., Citation2007). General disappointment and discontent with one’s current employment are examples of common psychological anguish. Both types of distress impact a person’s mental health (Gundelach & Henry, Citation2016; Islam & Chughtai, Citation2019; Williams et al., Citation2013). Professionals all around the world are dealing with anxiety and sadness as a result of their jobs. More than half of the medical workforce in Iran’s healthcare industry is stressed to a moderate degree (Joules et al., Citation2014). In this study, psychological distress is expected to act as a mediating mechanism in the relationship between the economic (financial difficulties and economic instability), political (political instability and corruption), social factors (life dissatisfaction and problems of family well-being) and intention to migrate. Economic, social, and political issues have all been linked to migration intentions in past studies (Agadjanian & Gorina, Citation2019). While it has been stated that economic and political instability is among the causes of migration intentions in developing countries (Etling et al., Citation2020), it has also been noted that those experiencing financial difficulties reported higher levels of psychological anguish (Aruta et al., Citation2021; Kimhi et al., Citation2020).

2.3.1. The present study

To our knowledge, no research has comprehensively studied the nature of relationship between home country economic (financial difficulties and economic instability), political (political instability and corruption), social factors (life dissatisfaction and problems of family well-being) and migration intention among Iraqi doctors. Hence, the impact of economic, political, and social issues on Iraqi doctors intention to migrate was examined in this study. The Push-Pull Theory asserts that an individual may be pushed by their environmental background in home country and pulled by economic or financial opportunities in the developed or destination country (Van Hear et al., Citation2018). Similarly, the Conservation of Resources Theory asserts that migrants’ primary goal is to build, safeguard, and nurture their resources to protect themselves and the social bonds that enable such protection (Van Hear et al., Citation2018), hence effects their decision related to migration. We hypothesise that psychological anguish in the form of psychological distress, as an individual-level component, may mediate the relationship between economic, political, and social factors and the inclination of Iraqi doctors to migrate.

2.4. Theoretical framework

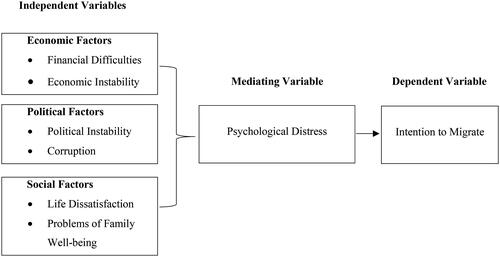

The primary goal of this study is to examine the relationship between various home country push factors and migration intentions, as well as the role of psychological distress in mediating the relationship. Accordingly, the theoretical framework is developed to achieve this goal, as shown in . The dependent variable of this study is intention to migrate, while the independent variables are home country push factors, namely political (political instability and corruption), economic (financial difficulties and economic instability), and social issues (life dissatisfaction and problems of family well-being). Psychological distress is proposed as a mediating component in the association between the independent and dependent variables.

2.5. Hypothesis development

This study aims to examine the influence of the home country political, social, and economic push factors on the intention to migrate among Iraqi doctors, with the presence of psychological distress as the mediating factor. Hence, the following hypotheses have been developed to test the proposed model of the study.

2.5.1. Relationship between financial difficulties and intention to migrate

The study of Goštautaitė et al. (Citation2018) investigated the impact of financial difficulties on the intention to migrate among physicians in Lithuania. The study concluded that migration decisions are linked to financial factors. Meanwhile, McAuliffe and Ruhs (Citation2017) in their study in Turkey discovered that, due to economic fragility, the high-risk behavior of crossing the sea had become the only viable option. Further, many people believe that crossing the sea is less perilous than remaining in Turkey, yet many choose to remain in Turkey because they lack the financial means to cross the border. According to the traditional Neoclassical Migration theory, people migrate when the advantages outweigh the costs (Harris & Todaro, Citation1970). On the other hand, financial limitations may hinder someone from migrating even if there is a net benefit from relocation. Studies examining the relationship between financial restrictions and migration from the standpoint of income shocks are an exception (Bazzi & Blattman, Citation2014). Despite a huge income difference, financially disadvantaged individuals and households frequently cannot migrate. Few research found that migration is a risk-diversification technique for insuring against income shocks, which places financial limitations in a prominent position in migration research (De Haas, Citation2010; Stark & Bloom, Citation1985). Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1: Financial difficulties are positively associated with intention to migrate

2.5.2. Relationship between economic instability and intention to migrate

Economic instability is linked to the decision of migrants to remain overseas for a certain amount of time because of government policy, income allocation, and more stable economic conditions in foreign countries (Ghazali et al., Citation2015). Economic instability, poor management and leadership, heavy workload, and discrimination are among the push factors to migrate (Kingma, Citation2018). The condition of the labour market and employment opportunities abroad and at home significantly affect the insights into economic opportunities by skilled professionals (Güngör & Tansel, Citation2008). Low economic stability would drive professionals and academics to leave (Kiang et al., Citation2014). In the literature on migration, wage differences are frequently stated as the key factor for the migration of skilled workers (Güngör & Tansel, Citation2014). We, therefore, proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Economic instability is positively associated with the intention to migrate

2.5.3. Relationship between political instability and intention to migrate

The political situation in Iraq has been unpredictable for many years, which has fuelled the desire to flee (Al-Tamimi, Citation2006). Iraq has a diverse ethnic population, which creates discord among the population (Bobbitt-Zeher, Citation2011), leading to a desire to relocate to more politically stable countries in search of peace. People of various religious beliefs are less inclined to coexist with the minority (Johnson, Citation2008). Political instability has been identified as a primary factor of youth migration intentions (Elbahnasawy et al., Citation2016), and has become a global phenomenon. According to Carmignani (Citation2003) and Elbahnasawy et al. (Citation2016), political instability creates uncertainty about future approaches, which demoralises speculation and causes human capital to go. It also harms the amount and quality of work that outstanding human capital can perform. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Political instability is positively related to the intention to migrate

2.5.4. Relationship between corruption and intention to migrate

Ariu and Squicciarini (Citation2013) studied the migration movements of working professionals in 123 nations. They revealed that severe corruption in the home country causes high worker outflows. Dimant et al. (Citation2013) studied a panel of 111 nations between 1985 and 2000 and confirmed that corruption positively affects professional workers’ migration but not average workers. Cooray and Dzhumashev (Citation2018) indicated that forced migration could be linked to corruption in the labor market. Corruption could also incentivize people to leave their home country (Dzhumashev, Citation2016). Auer et al. (Citation2020) used a global survey data of 280,000 respondents from 67 countries from 2010 to 2014 and discovered that corruption significantly drives migration intention. Based on above discussion, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4: Corruption is positively related to the intention to migrate

2.5.5. Relationship between life dissatisfaction and intention to migrate

The study of Otrachshenko and Popova (Citation2014) revealed that individuals who are highly dissatisfied with their current life have a higher intention to migrate, indirectly caused by socioeconomic variables and macroeconomic conditions. Similarly, the individual characteristics drive migration intentions further. This indicates that individual life satisfaction strongly predicts one’s intention to migrate and mediates migration intention via individual socioeconomic variables and macroeconomic conditions. The study of Migali and Scipioni (Citation2018) examined the effect of life dissatisfaction on intention to migrate. Their finding indicated a non-linear relationship between migration preparation and individual income. Their study also stated that dissatisfaction with one’s current standard of living drive the intention to migrate. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 5: Life dissatisfaction is positively related to the intention to migrate

2.5.6. Relationship between problems of family well-being and intention to migrate

Family well-being is driven by the family members’ subjective well-being. The study of Cai et al. (Citation2014) examined the effect of subjective well-being (SWB) on the intention to migrate. The study found that people with greater SWB have a lesser intention to migrate internationally. Individually, the effect of SWB on migration is more robust than the effect of income on migration. Malla and Rosenbaum (Citation2017) examined the migration of Nepalese to Gulf countries for employment. They discovered that although there are risks for doing so, they continue to migrate anyway as there are very few prospects for them and their family in their home country instead of the destination country. The study also found that the effect of positive family well-being on migration is significant. Pressure to act against problems of family well-being as a push factor drives people to migrate and seek for better family welfare and comfort elsewhere (Sunarti et al., Citation2021). Hugo (Citation1995) argued that problems of family well-being influences labour movements. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 6: Problems of family well-being is positively related to the intention to migrate

2.5.7. Relationship between psychological distress and intention to migrate

The study by Asakura and Murata (Citation2006) revealed a positive link between psychological distress and intention to migrate. In a related study, Virupaksha et al. (2014) examined the effect of psychological distress and mental stress on the intention to migrate and found a positive relationship between the variables. The study by De Castro et al. (Citation2015) found that poor mental health and social stress trigger the intention to migrate among nurses. Anxiety, irritability, and tension may trigger intention to migrate. Irritability has been linked to avoidance and withdrawal behavior (Smits & Boeck, Citation2006), whereby people with high irritability scores have been shown to have higher intentions to migrate. Meanwhile, Sabti and Ramalu (Citation2020) found that self-depreciated and social disengagement behaviour leads to increased intention to migrate. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 7: Psychological distress is positively related to the intention to migrate

2.5.8. The mediating effect of psychological distress in the relationship between political, economic, social factors and intention to migrate

Studies have found home country political, economic and social push factors can cause psychological distress. For example, the study of Tsuchiya et al. (Citation2020) found that financial stressors have an adverse effect on severe psychological distress with a positive association between them. On the same note, the study of Thapa and Hauff (Citation2005) examined the effect of the lack of salaried jobs and recent negative life events on psychological distress and found a positive relationship between the variables. According to Asakura and Murata (Citation2006), financial difficulty as a push factor causes stress and restlessness whilst low wages lead to psychological stress. Likewise, there is also evidence of direct relationship between various home country push factors and intention to migrate. For example, Górecki et al. (Citation2019) acknowledged that financial difficulties are the main factor of the intention to migrate. Another study revealed that economic instability in the home country pushes nurses to migrate, whilst better wages, living and working conditions, and educational and career prospects in developed countries pull them to migrate there. Hence, it is imperative to assess the role of psychological as the possible mediating factor. Thus, the present study explores the role of psychological distress in mediating the link between various home country push factors and migration intention. Montani et al. (Citation2020) discovered that psychological distress plays a mediating role in the relationship between negative economic instability appraisal and withdrawal behaviour among employees. Hence, the following hypotheses is proposed to test the mediation role of psychological distress:

Hypothesis 8: Psychological distress mediates the relationship between financial difficulties and the intention to migrate

Hypothesis 9: Psychological distress mediates the relationship between economic instability and the intention to migrate

Hypothesis 10: Psychological distress mediates the relationship between political instability and the intention to migrate

Hypothesis 11: Psychological distress mediates the relationship between corruption and the intention to migrate

Hypothesis 12: Psychological distress mediates the relationship between life dissatisfaction and the intention to migrate

Hypothesis 13: Psychological distress mediates the relationship between problems of family well-being and the intention to migrate

3. Methods

3.1. Research design and data analysis procedure

This study uses a quantitative approach to examine the nature of relationships between the proposed variables of the study. Prior to data analysis, the researcher coded the questionnaires and keyed-in the data into the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 27. The data were then screened to assess the missing values, detect outliers, and assess the normality of the data. Subsequently, descriptive statistics were performed to compare and describe the demographics profile of the respondents. To test the hypotheses, the present study used Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM), the second generation Structural Equation Modelling (SEM). The SEM is suitable to examine the cause-and-effect relationship between the latent constructs (Hair et al., Citation2011, Citation2017). Furthermore, PLS-SEM eliminates small sample size issues and has less stringent normality and error term assumptions (Reinartz et al., Citation2009). PLS-SEM can test both the measurement and structural models at the same time (Gefen et al., Citation2011; Ringle et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, PLS-SEM can work with models with a hierarchical structure and a large number of indicators, components, and relationships (Hair et al., Citation2011; Reinartz et al., Citation2009). The structural model investigated thirteen hypotheses and their interactions in this study. The model included 55 measurement items and a 460-person sample. Because there are so many measuring items, this would necessitate a considerably bigger sample size, which was unavailable for this investigation. Furthermore, sophisticated model aspects, such as the mediating role of psychological distress, were added to this study’s model. As a result, it estimates path models with many constructs, structural path links, and indicators per construct, therefore, in the current investigation, the PLS-SEM technique was appropriate to achieve accurate predictions. Validity and reliability were assessed in the first stage using convergent validity, discriminant validity, and Cronbach’s alpha. The effect of different variables on the dependent variable was investigated in the second stage using bootstrapping analysis.

3.2. Measures

The current study adapted 4-items Intention to Migrate Scale developed by Shariff et al. (Citation2018). The Cronbach’s alpha of this scale was 0.839 (Shariff et al., Citation2018). The economic instability was measured using five-items adapted from Fong and Hassan (Citation2017) and Chikanda (Citation2005). Financial difficulties was measured using scale developed by Hense (Citation2016). The scale has five items with a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.759. The instrument to measure political instability was adapted from scale developed by Fong and Hassan (Citation2017) and Chikanda (Citation2005). The scale has five items with Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.95. Corruption measured with four items adapted from scale developed by Tan et al. (Citation2016) and Chikanda (Citation2005). Life dissatisfaction was measured with scale developed by Diener et al. (Citation1985). The scale has five items and was reported to have reliability value ranges from 0.61 to 0.84. Problems of family well-being was measured using scale adapted from Ho et al. (Citation2016). The scale has four items with Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.74. Measure for psychological distress was adapted from scale developed by Drapeau et al. (2012) and Massé et al. (Citation1998). The scale has 23 items and the Cronbach’s alpha value ranges from 0.67 to 0.79. All the items for this study were measured on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

3.3. Population and data collection procedure

The study’s population consist of 8,293 doctors working in 95 private and government hospitals in Baghdad (Iraqi Ministry of Health, Citation2017). Krejcie and Morgan (Citation1970) suggested that a sample size of 368 is appropriate for above population size. However, the researcher distributed 460 questionnaires to the selected respondents in anticipation of a low response rate (Saleh & Bista, Citation2017). The data were collected using self-administered online questionnaire which was emailed to the respondents. The questionnaire had 55 items excluding the demographics items. Three hundred and seven questionnaires were returned. However, of these, seven were unusable, yielding in 300 usable questionnaires. The data collection lasted for five months i.e., from June 2020 to October 2020. Data collection was initiated upon approval from the Iraqi Ministry of Health and the related hospitals. This study collected responses using the virtual snowball sampling technique whereby existing subjects provide referrals for the needed sample recruitment (Baltar & Brunet, Citation2012). This enables unbiased response collection. It is especially beneficial in instances when it is difficult to find participants. Furthermore, it helps to access ‘hard-to-reach’ populations, expands the sample size and study scope, and reduces cost and time (Benfield & Szlemko, Citation2006; Bhardwaj, Citation2019).

4. Results

4.1. Demographic profile

As depicted in , 70% of the respondents were male. This is not surprising since male have a dominant position over their female counterparts in Iraq. As for the age distribution, 37% of the respondents are 35 years and below, 48% are between 36 and 45, and another 15% are between 46 and 60. In terms of marital status, 84% of the respondents are married while the remaining 16% are single.

Table 1. Demographic profile of the respondents.

With regards to work experience, 34% of the respondents have been working for five years and below, 48% have been working for about 6–10 years, and 16% have been working for about 11–15 years, while the remaining 2% have been working for more than 16 years. In terms of income, 44% of the respondents are earning between 1,000,000 and 1,500,000 dinar, 50% are earning between 1,500,001 and 2,000,000 dinar, and the remaining 6% are earning more than 2,000,001 dinar. As for the highest education level, 27% of the respondents have a fellowship degree, and 73% have an M.B. Ch.B. degree.

4.2. Data screening and preliminary analysis

The data screening process was carried out to determine the data’s suitability for multivariate data analysis. Data screening is critical process in data analysis, especially in quantitative research, because it lays a firm foundation for getting significant results. According to Hair et al. (Citation2010), the quality of the analysis must be based on the quality of preliminary data screening. Univariate outliers in the sample were identified using standardised values with a 3.29 (p. 001) criterion, following the recommendation of Tabachnick and Fidell (Citation2007). Based on the obtained values, no univariate outliers were found. The Mahanalobis distance (D2) was also calculated. The Mahanalobis distance (D2) was determined for 50 examples using the specified chi-square threshold of 97.039 (p = 0.001), with none of the observations being identified as outliers. Because the missing values in this study were less than 5% and happened at random, they were replaced using a series mean, a procedure suggested by Tabachnick and Fidell (Citation2007).

Similarly, the outcome of Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilks Statistics were analysed, and the results reveal that all 50 metrics of the dataset are significant at 0.001, suggesting that normality norms were broken, and 5 items out of 55 were eliminated. As a result, it is wise to conclude that this study’s dataset is not normally distributed, providing yet another reason to adopt PLS-SEM for path analysis. In addition, the current study used Harman’s single-factor test for Common Method Variance (CMV), as recommended by Podsakoff and Organ (Citation1986). The variation in the study’s exogenous variables is calculated using this method. According to Eichhorn (Citation2014), the total variance should be no more than 50%. Following the instructions, all 50 items were subjected to principal component factor analysis, resulting in a total variance of 35%, most lower than the acceptable criterion. In addition, the test revealed that no single factor accounted for most of the covariance among the study’s exogenous variables, hence there is no CMV problem in this study.

4.3. Descriptive analysis of the latent construct

The descriptive statistics in terms of mean and standard deviation were computed in this study as shown in . Each latent variable were rated on a five-point scale, with 1 indicating significant disagreement and 5 indicating strong agreement. According to Sassenberg et al. (Citation2011), the scores can be classified as low, moderate, or high. A score of 2 or less is considered low, a score of 3 is considered moderate, and a score of 4 or more is considered high. Mean values of the study variables ranged from 3.4223 to 3.9993, with standard deviations ranging from 0.72739 to 1.02852 in the descriptive analysis. As a result, most respondents had a moderate opinion of the study’s variables.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

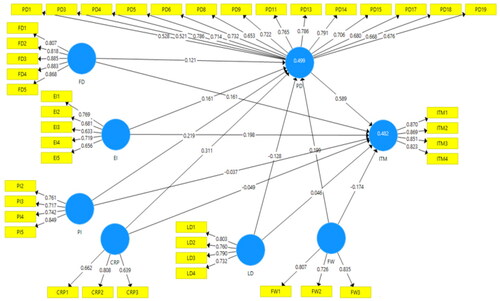

4.4. Assessment of the measurement model

The assessment of the suitability of the measurement (outer) model can be analyzed by observing: (1) the construct reliability and composite reliability (CR), which is used to analyze the internal consistency reliability; (2) the average variance extracted (AVE) which is used for determining the convergent validity of the indicators with individual constructs; and (3) the Fornell-Larcker criterion and the indicator’s outer loadings used for discriminant validity. To measure internal consistency, the traditional criterion is Cronbach’s alpha, which is based on the inter-correlations of the observed indicator variables that provide the construct’s reliability (Hair et al., 2016). The study of Hair et al. (Citation2017) stated that the values of CR vary between 0 and 1. Values less than 0.60 should not be considered, values between 0.60 and 0.70 represent the average internal consistency reliability, values above 0.70 are considered as satisfactory, and values between 0.70 and 0.95 are considered adequate. Values above 0.95 are not desirable because they indicate that all the indicators of constructs are measuring the same phenomenon and thus are not a valid measure of the construct. The Cronbach’s alpha values are relatively lower than the CR values (Hair et al., 2016). Therefore, in the current study, all the constructs’ Cronbach’s alpha and CR values were observed. In the present study, all the Cronbach’s alpha values are between 0.725 and 0.918, and all the CR values are between 0.748 and 0.93, indicating that the reliability of the measurement (outer) model is adequate. The details are shown in .

Table 3. Internal consistency reliability.

The next step is to examine the convergent validity, which explains the level of positive correlation among the measures or indicators of the same variable or constructs (Hair et al., 2016). The threshold value of AVE is 0.50 and above, which indicates adequate convergent validity; in other words, half of the variance of the indicators is explained by the latent construct (Hair et al., Citation2017). Conversely, an AVE value less than 0.50 means that more variance remains in the error of the items than in the variance explained by the construct (Hair et al., 2016). Hence, convergent validity is assessed in the present study by examining the AVE values and outer loadings. Items with AVE values less than 0.5 in the outer loading would be deleted, as shown in . Four items were deleted after the pilot study for psychological distress given the large number of items it has. In the main study, some items with AVE values less than 0.5 were deleted. The final results reveal that all the AVE values for all the constructs are higher than 0.50, and the outer loadings are also higher than 0.521, as shown in . Hence, convergent validity is established. The final items descriptions is shown in Table A1 in Appendix A.

The final step is assessment of the discriminant validity. Discriminant validity refers to how distinct a construct is from the others regarding empirical evidence (Hair et al., Citation2017). The Fornell–Larcker criterion is the most popular method to determine discriminant validity. This method compares the square root of the AVE values to the latent variable’s correlations (Hair et al., 2016). As a result, the square root of the construct’s AVE value should be greater than its correlation with any other construct in the model (Hair et al., 2016; Henseler et al., Citation2009). The square root of the AVE value of the construct is bigger than the highest association with any other construct in the current study based on the Fornell–Larcker criterion. As a result, discriminant validity has been established. The square root of the AVE value for corruption is 0.707; for economic instability it is 0.694; for financial difficulties it is 0.853; for problems of family well-being it is 0.803; for intention to migrate it is 0.853; for life dissatisfaction it is 0.772; for psychological distress it is 0.700; and for political instability it is 0.769 (refer to ).

Table 4. Discriminant validity.

The second approach entails examining the indicators’ cross-loadings or the construct’s outer loadings, which should be higher than the other constructs’ outer loadings (Hair et al., 2017). Cross loadings higher than the indicators of the outer loading revealed that discriminant validity is a problem. In the current study, the results indicate that discriminant validity is established because the cross loadings of the other constructs were not higher than the indicators of the outer loading of the construct.

4.5. Assessment of the structural model

Once the measurement model has been validated, the structural model is subsequently assessed using the PLS path modeling. The hypothesized relationships are tested in this step. It was proposed that the structural model be tested in two stages i.e., assessment of the direct relationships, and inclusion of the indirect (mediating) test (Hair et al., 2014; Hair et al., 2016).

The relevance of the structural model’s route coefficients is assessed using the conventional bootstrapping approach using 5,000 bootstrap samples and 300 examples (Hair et al., 2016). To compare PLS-SEM results with a variable number of exogenous structures and/or different sample sizes, R-square adjusted is employed (Hair et al., 2016). The modified R-square value generally reduces the R-square value by the number of explaining constructs and sample size. The modified R-square value is fairly near to the R-square value, indicating that no major differences exist between the original dataset and the extended or other datasets. Although the R-square value and modified R-square varied somewhat, no major changes occurred; thus, other datasets are predicted to provide the same results regarding these correlations.

The R-square value of intention to migrate in this study is 0.482, with an adjusted R-square of 0.470. Similarly, psychological distress has an R-square of 0.499 and an Adjusted R-square of 0.489. Using the blindfolding process, the Stone test Geisser’s was performed to assess the research model’s predictive relevance (Geisser, Citation1974). The test assesses the goodness-of-fit of the PLS structural equation modeling (Duarte & Raposo, 2010). Sattler et al. (Citation2010) proposed using the blindfolding process on the study’s endogenous variable(s) to determine the reflective models’ predictive significance. As a result, the cross-validated redundancy metric (Q2) was used in this study to establish the predictive relevance (Geisser, Citation1974; Hair et al., Citation2014; Ringle et al., Citation2012). According to Henseler et al. (Citation2009), a (Q2) result greater than zero suggests that the research model is sufficiently predictive. As such, higher (Q2) statistics indicates a higher predictive relevance. In the current study, Q2 shows a value of 0.262 for intention to migrate and 0.183 for psychological distress. Hair et al. (2016) argued that a Q2 value above zero indicates predictive relevance.

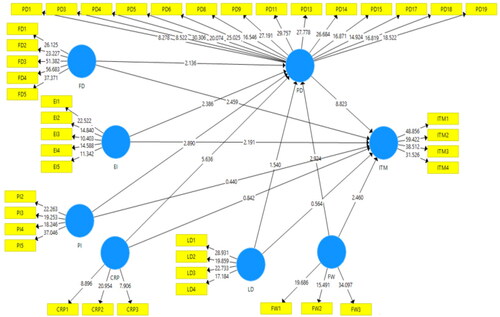

4.6. Direct relationship

displays the path coefficient values, p values, t values, and standard error. Based on these standard values, the hypothesis was accepted or rejected. The original number of cases in the model were 300 cases with 5000 bootstrapping samples (Hair et al., 2016, Citation2017; Henseler et al., Citation2016). This study assessed six hypotheses with direct associations with the intention to migrate. Of the six, two hypotheses were proven to be supported and four were not. Moreover, six hypotheses which have direct associations with psychological distress were assessed. Out of the six, five hypotheses were proven to be supported and one was not supported. Similarly, hypothesis testing the relationship between psychological distress and intention to migrate was supported. based on the PLS Algorithm shows the hypothesized relationships (path coefficient) among all the constructs in the model. The result of hypotheses testing for direct relationships is summarized in .

Table 5. Direct relationship.

Hypothesis 1 predicted that financial difficulty positively relates to the intention to migrate. The result demonstrates a significant and positive relationship between financial difficulty and intention to migrate (β = 0.161, t = 2.459, p = 0.015) thus supports hypothesis 1. Hypothesis 2 predicted that economic instability positively relates to the intention to migrate. The result demonstrates a significant and positive relationship between economic instability and the intention to migrate (β = 0.198, t = 2.191, p = 0.026) thus supporting hypothesis 2. Hypothesis 3 predicted that political instability is positively related to the intention to migrate. As shown in , a non-significant relationship between political instability and intention to migrate was found (β= −0.037, t = 0.440, p = 0.658), thus rejects hypothesis 3. Hypothesis 4 predicted that corruption is positively related to the intention to migrate. The result demonstrates a non-significant relationship between corruption and intention to migrate (β= −0.049, t = 0.842, p = 0.393) thus rejecting hypothesis 4. Hypothesis 5 predicted that life dissatisfaction is positively related to the intention to migrate. The result demonstrates a non-significant relationship between life dissatisfaction and intention to migrate (β = 0.049, t = 0.564, p = 0.576) thus rejecting hypothesis 5. Hypothesis 6 predicted that problems of family well-being is positively related to the intention to migrate. demonstrates a significant and negative relationship between problems of family well-being and intention to migrate (β= −0.174, t = 2.450, p = 0.013), thus rejected hypothesis 6. Hypothesis 7 predicted that psychological distress positively relates to the intention to migrate. The result demonstrates a significant and positive relationship between psychological distress and intention to migrate (β = 0.589, t = 8.823, p = 0.000), thus supporting hypothesis 7.

4.7. Indirect relationship

In this study, six (6) indirect effects are examined through the mediating variable hypotheses. These six hypotheses are shown in . Additionally, presents the structural model assessment with the model’s indirect paths relationship, t-value, and p-value.

Table 6. Indirect relationship.

shows the coefficients of the six indirect hypotheses and their t values and p values, which are used to determine whether or not the hypothesised associations are statistically significant. Hypothesis 8 predicts the significant mediating effect of psychological distress in the relationship between financial difficulties and the intention to migrate. The result shows that psychological distress mediates the relationship between financial difficulties and intention to migrate, and it is significant (β = 0.071, t = 2.054, p = 0.04). Therefore, hypothesis 8 is accepted. Hypothesis 9 predicts the significant mediating effect of psychological distress in the relationship between economic instability and intention to migrate. The result shows that psychological distress mediates the relationship between economic instability and intention to migrate, and the mediation is significant (β = 0.097, t = 2.258, p = 0.024). Therefore, hypothesis 9 is accepted. Hypothesis 10 predicts the significant mediating effect of psychological distress in the relationship between political instability and intention to migrate. shows that psychological distress mediates the relationship between political instability and intention to migrate (β = 0.129, t = 2.749, p = 0.006). Therefore, hypothesis 10 is accepted. Hypothesis 11 predicts the significant mediating effect of psychological distress in the relationship between corruption and intention to migrate. The result shows that psychological distress mediates the relationship between corruption and intention to migrate, and it is significant (β = 0.182, t = 4.632, p = 0.000). Therefore, hypothesis 11 is accepted. Hypothesis 12 predicts the significant mediating effect of psychological distress in the relationship between life dissatisfaction and intention to migrate. The result shows that the mediating effect of psychological distress in the relationship between life dissatisfaction and intention to migrate is not significant (β= −0.075, t = 1.481, p = 0.139). Therefore, hypothesis 12 is rejected. Hypothesis 13 predicts the significant mediating effect of psychological distress in the relationship between problems of family well-being and intention to migrate. The result shows that the mediating effect of psychological distress in the relationship between problems of family well-being and intention to migrate is significant (β = 0.116, t = 2.755, p = 0.006). Therefore, hypothesis 13 is accepted. summarizes hypothesis testing decision.

4.8. Summary of hypothesis testing

Table 7. Hypothesis testing summary.

5. Discussion of the study findings

This study examined the direct and indirect effects of home country economic, political, and social factors on migration intentions, as mediated by psychological distress. Hypothesis 1 has been empirically validated, and the findings suggest that migration intentions significantly and positively influenced by financial difficulties. This research has confirmed the need for financial security among physicians as a motivation to migrate. This indicates that the migration of Iraqi doctors has become a growing global phenomenon and is constantly evolving in response to the country’s ongoing economic and social changes. The result of this study is congruent with the Push-Pull Theory and with those findings of past studies (Hajian et al., Citation2020). Hypothesis 2 was accepted because economic instability in Iraq seems to contribute equally to intention to migrate among Iraqi doctors. These considerations could explain why, in most cases, the positive effects of unemployment on intention to migrate persist, as they did in this study. This suggests that Iraqi medical practitioners may be enticed to go abroad in search of higher pay, a better standard of life, as well as prospects for career progression not accessible in impoverished developing countries. Home country push factors related to ‘economy of need’ in the form of financial difficulties and economic instability could be the major reason that motivate individuals start business in host country once they migrate (Martínez-Cañas et al., Citation2023). Ability to recognize business opportunities coupled with support of someone in social networks who owns a venture especially if this person belongs to the potential entrepreneur’s family-based network could help individuals to set up business (Ruiz-Palomino & Martínez-Cañas, Citation2021). In the case of medical doctors, they might consider to open up their own clinic or hospital in host country with the support of their social networks.

Contrary to the prediction, hypothesis 3 was rejected because Iraqi medical doctors believe they are not necessarily disturbed by the amount of political instability. The present study findings confirm previous findings in similar cases about the relationship between political instability, corruption, and migration intentions (Holmes & De Piñeres, Citation2011; Zetter et al., Citation2013; Balcells & Steele, Citation2016). This study’s findings are comparable to those of Ozaltin et al. (Citation2020), which found that just around half of all respondents with violent experiences desire to leave Baghdad. Hypothesis 4 was also rejected because Iraqi medical doctors believe that their intention to migrate is not necessarily influenced by corruption. This finding suggests that corruption has no impact on the intention to migrate in Iraqi context. In other words, corruption does not constitute a factor that compels Iraqi doctors to migrate outside the country.

The assumption of hypothesis 5, which implies a positive link between life dissatisfaction and the desire to relocate among Iraqi doctors, was similarly not supported in this study. The study’s findings demonstrated that discontent with one’s life had no bearing on one’s desire to relocate. In this study, Iraqi doctors are of the view that factors, which may compel them to migrate to another country are not due to life dissatisfaction or family problems. As for the hypothesis 6, problems of family well-being negatively affect the intention to migrate. However, the direction of relationship is not as hypothesized; therefore, the hypothesis is rejected. Although the hypothesis was not supported, the negative significant relationship found between problems of family well-being and intention to migrate is quite interesting. The negative relationship between problems of family well-being and intention to migrate suggest that the greater the concern for problems of family well-being, lower the intention to migrate. The desire to improve family well-being by venturing into business could be the important home country push factor that motivate individuals to remain in the home country (Dawson & Henley, Citation2012). In other words, intention to become entrepreneur could be negatively related to intention to migrate. Cai et al. (Citation2014) discussed the effect of subjective well-being on the intention to migrate internationally i.e., a clear inclination to migrate, and asserted that people with higher subjective well-being have less intention to migrate.

In regard to the hypothesis 7, the study’s empirical findings reveal that psychological distress has a considerable and favourable impact on migration intentions. This finding is consistent with notion of Push-Pull Theory by indicating that Iraqi doctors experiencing psychological anguish are more likely to develop desire to leave their homeland. Furthermore, this data shows that psychological distress is more likely to occur in a high-stress and high-frustration workplace. Similarly, it was discovered that higher workplace stress and lower job satisfaction were connected to considering migrating and moving work centers among Iraqi doctors; this also agrees with the results, since psychological stress is regarded a type of job-related stress factor.

As for the mediating effect of psychological distress in the relationship between various economic, political, and social factors and intention to migrate, the present study found that psychological distress mediates the relationship between financial difficulties, political instability, corruption, life dissatisfaction, problems of family well-being and intention to migrate, hence supports H8, H9, H10, H11 and H13. These results suggest that Iraqi medical doctors with higher levels of psychological stress due to financial difficulties, economic instability, political instability, corruption, and problems of family well-being are more likely develop intention to migrate. This result is similar to the result from the previous research (Mirza et al., Citation2019; Vuorinen et al., Citation2021). Finally, the results disclaim the prediction of Hypothesis 12, which assumes the mediating effect of psychological distress on the relationship between life dissatisfaction and intention to migrate. This is similar to the result where psychological distress couldn’t perform a mediating function (Khamis, Citation2016). The plausible reason for the rejected hypothesis is partly due to insignificant relationship found between life dissatisfaction on intention to migrate among Iraqi doctors.

6. Implications of the study

This study offers a number of theoretical and practical implications. The theoretical implications are discussed in the first section while the practical implications in the next section.

6.1. Theoretical implication

The following are some of the study’s theoretical implications. The current study addressed the flaws of Push-Pull Theory by analysing the mediating influence of psychological distress in the relationship between the various home country push factors and migration intention. The push factors may not directly influence intention to migrate, but rather induce the desire to migrate through psychological suffering. As a result, the current work has revealed the underlying mechanism (i.e., psychological distress) that is responsible for the effect of push factors on intention to migrate. The study has contributed to a conceptual understanding of the effect of various home country push factors such as economic instability, financial difficulties, corruption, political instability, life dissatisfaction, and problems of family well-being in creating psychological distress, which would eventually boost the intention to migrate. As a result, the findings have pushed for a extension of Toren’s Push-Pull Theory by including explanations for why unfavorable social, political, and economic factor led to migration intention. Additionally, the current study has provided a rather different theoretical approach, implying that political issues may have little effect on migration intentions. This intriguing line of inquiry calls into doubt Toren’s Push-Pull Theory’s conventional claims; it opens new avenues for understanding political factors, whether positive, negative, or neutral. Another theoretical contribution is the confirmation of Conservation of Resources Theory in predicting intention to migrate, which states that people use time, cognitive and physical resources to complete various tasks but would eventually need to replenish those resources to prevent stress. Hence, this theory explains the relationship between home country push factors and psychological distress, which will have cross over effect on intention to migrate.

6.2. Practical implications

The practical implications of this study are specifically focused on the healthcare sector in Iraq. The findings provided new insight into the antecedents of migration intention and how it can be addressed. The present study offers a framework for evaluating the role of economic, political, and social factors that could influence the intention to migrate among doctors in private and public hospitals in Iraq. The study results show that the lack of social and economic factors can generate psychological distress among doctors, ultimately forcing them to migrate to developed countries in particular. The study suggest the top management of the hospitals, policymakers, and government administration should focus on improving the social and economic factors which can help to counter the worsening situation in Iraq that is unbearable for the doctors. For example, Iraqi government should consider improve the existing salary schemes and provide attractive benefits to their medical doctors. However, the political factor is the only factor doctors could not consider for migration. The findings show that political instability is not a reason for the doctors to leave the country. Findings from the present study helped identify the potential factors of psychological distress, increasing the intention to migrate among healthcare professionals. Based on the findings, healthcare professionals who are experiencing greater psychological distress are more likely will consider to migrate. Organizations in the country are suggested to mitigate the negative impacts of these factors through appropriate human resource interventions.

7. Limitations and recommendations for future research

The present study has a number of limitations that provide avenues for future research. Firstly, the data was taken from only one city i.e. Baghdad. Due to the prevailing pandemic, the researcher could not visit the whole country. Although the different population characteristics were taken, they are not enough to represent the entire population. Hence, data should be taken from the whole country to enable a strong representation of the entire population for further study. Secondly, in the midst of the epidemic, the virtual snowball sampling technique (non-probability sampling) was employed. It entailed the referrals of related persons to give the needed data online. Such measure might create biasness (Bhardwaj, Citation2019). In post-pandemic, future researchers could change the sampling technique and visit the hospitals personally to collect the data by using the probability sampling technique to reduce biasness. Thirdly, the age factor could have contributed to greater migration intentions. The respondents’ age showed a low mean, suggesting that the results are not useful for making general policies. Specific policies may also not be useful in the long-term and subsequent interventions may create disapproval. Hence, such strategies could help formulate general policies in the future. Age could be used to moderate the relationship between psychological distress and intention to migrate. Fourthly, the study did not include the information about types of jobs taken up by the individuals who are planning to migrate. Starting up own business at host country could be one of the most considered options for professionals in global economy, hence future research should include this aspect for a better understanding about migration phenomenon. For this, future research can assess the availability of support from social network who owns a venture especially family-based network which can facilitate the start-up process (Edelman et al., Citation2016; Hansen, Citation1995; Ruiz-Palomino & Martínez-Cañas, Citation2021). Fifthly, future research could also examine the effect of home country push factors (e.g., financial difficulty, economic instability, problems of family well-being) on intention to venture into business (Kirkwood, Citation2009), hence a negative relationship between intention to become an entrepreneur and intention to migrate can be confirmed. Finally, the current study’s research design entails a survey questionnaire and is cross-sectional in nature; data collection was carried out at one point in time for the purpose of hypotheses testing. Future studies could employ longitudinal studies and panel data to achieve clearer findings.

8. Conclusion

The current study has provided empirical evidence for the importance of various home country push factors related to economic, social, and political in influencing migration intentions, with the presence of psychological distress as the mediating variable. In a summary, the findings lent credence to major theoretical premises and provided appropriate answers to the study’s research questions. The findings have also contributed to the body of knowledge in the realm of Toren’s Push-Pull theory and other supporting theories such as the Hobfoll’s (Citation1989) Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, confirming the interplay of economic, social, and political elements in influencing migration intentions. Current studies that focus on understanding the determinants of migration agree on the promotion of protective factors that emanate from the individual to the surrounding environment. It is also important to recognize that successful determinants of migration may vary from one person to the next based on multiple factors such as personality, specific challenges, available resources, and the environmental context. In this particular study, however, a significant factor that can boost the propensity to migrate among Iraqi doctors is evidently found within equipping and eradicating challenges within their migration experience. Also, the predictive power of psychological distress as a mediating variable, particularly regarding stress, is highlighted, which should be incorporated into policy design and communication and further investigated. Finally, Iraq as a country shown to have typical determinants of emigration but, tentatively, it seems that those that have suffered war or are extremely rich are shown to be atypical in that the effects of socio-demographics are weakened or even reversed in these situations. The extent to which this relationship can be validated by looking at other rich countries in the Arab world and elsewhere should be investigated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Yousif Mousa Sabti

Dr. Yousif Mousa Sabti teaches organizational behaviour and human resource management. Dr. Yousif holds an international trainer certificate from the German International Academy for Qualification, Development, Training, Consultation and Sustainable Development. He has held various administrative positions at the private Universities. Dr. Yousif’s research interest includes, organizational behaviour and human resource management. To date, he has published more than 30 articles in both local and international journals.

Subramaniam Sri Ramalu

Dr. Subramaniam Sri Ramalu, is an Associate Professor of Organizational Behavior and Leadership. Dr Subramaniam is a Certified Professional Trainer of Malaysian Institute of Management and Human Resources Development Fund. He has held various administrative positions at the University. Dr. Subramaniam’s research interest includes leadership, organizational behaviour and human resource management. He has successfully supervised 20 doctoral students and more than 30 Master students. To date, he has completed 16 research projects and published more than 60 articles in both local and international journals.

References

- Aboulenein, A., & Levinson, R. (2020). The medical crisis that’s aggravating Iraq’s unrest. A Reuters Special.

- Agadjanian, V., & Gorina, E. (2019). Economic swings, political instability and migration in Kyrgyzstan. Revue Europeenne de Demographie [European Journal of Population], 35(2), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-018-9482-4

- Al-Samarrai, M. A. M., & Jadoo, S. A. A. (2018). Iraqi medical students are still planning to leave after graduation. Journal of Ideas in Health, 1(1), 23–28. https://doi.org/10.47108/jidhealth.Vol1.Iss1.5