Abstract

Literature is prolific on how several crises have affected tourism and hospitality. However, those studies are primarily concerned with the impacts at the destination level and less with tourism businesses’ resilience and recovery. However, recently, some studies have addressed tourism resilience in a broader range, primarily because of how tourism and hospitality has been affected by COVID-19. The pandemic had completely different characteristics from other disasters that affected tourism businesses previously—namely, its global range and long duration. When studying business recovery, it is relevant to investigate how managerial models and perceptions affected how T&H firms responded to the consequences of the pandemic. The purpose is to study how T&H firms’ entrepreneurial orientation and managers’ perception of the external environment, namely market recovery, relate to the actions taken during the pandemic. We conducted a cluster analysis to test our propositions considering two clustering variables: EO (Entrepreneurial Orientation) and MRP (Market Recovery Perception). Results suggest three types of T&H firms exist and that these opted for different recovery actions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, our work presents a set of important theoretical and practical implications that can be useful to several stakeholders, namely academics and professionals.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic affected several economic activities and impacted businesses globally (Su et al., Citation2021). Tourism and hospitality (T&H) were among the most affected activities (Islam et al., Citation2021). As highlighted by Costa et al. (Citation2021), literature is prolific on how other types of disasters have affected tourism activities in the past. Those studies are mainly focused on localised events in space and time, such as terrorist attacks (e.g. Tingbani et al., Citation2019), earthquakes and tsunamis (e.g. Orchiston & Higham, Citation2016) or typhoons, storms, and floods (Ghaderi et al., Citation2015). However, these are studies mostly concerned with the impacts at the destination level and less with tourism businesses’ resilience and recovery. Resilience refers to an organisation’s ability to recover from a crisis (Duchek, Citation2020).

Recently, some studies have addressed tourism resilience in a broader range. For example, Alebaki and Ioannides (Citation2017) studied the resilience of Greece’s wine tourism sector from multiple stakeholders’ perspectives. Sheppard and Williams (Citation2016) found that individual factors such as well-being and cognitive and behavioural competencies are an essential part of the resilience framework. Watson and Deller (Citation2022) focus on the dependency of a region from T&H as a factor that results in lower resilience. However, they note that even within each region, there are pockets where the opposite is true, ‘where greater dependency enhanced economic resiliency’ (p. 1210).

However, the COVID-19 pandemic had completely different characteristics from other disasters that affected tourism previously—namely, its global range and long duration. No other crisis that affected T&H this century (e.g. terrorist attacks, epidemics, natural disasters) had a global range or lasted as long as the COVID-19 pandemic. It is, therefore, relevant to investigate how managerial models and perceptions affect how T&H firms responded to the consequences of the pandemic.

Managerial models might be entrepreneurial or traditional (Stevenson & Jarillo, Citation2007). Traditional management models can be suitable in routine and predictable environments but inadequate in adverse environments and crises (Gibson & Tarrant, Citation2010), especially in situations like the COVID-19 pandemic. Extant literature has shown that entrepreneurial resources are crucial to mitigating the COVID-19 crisis’s adverse effects on business firms (Scheidgen et al., Citation2021). Firms with higher entrepreneurial orientation (EO) may quickly adapt to unpredictable environmental changes (Laskovaia et al., Citation2019) and, tend to be more proactive in seeking new opportunities and are more able to adapt to changing market conditions (Rauch et al., Citation2009). Literature also shows that entrepreneurial activities can be an effective strategy for managing a crisis’s challenges (Boers & Henschel, Citation2022; Laskovaia et al., Citation2019; Zighan et al., Citation2022). For instance, Laskovaia et al. (Citation2019) have found the relevant role of entrepreneurial management in economic crisis, and Zighan et al. (Citation2022) the role of EO in SMS resilience. Boers and Henschel (Citation2022) studied the EO of family firms during the pandemic. However, despite its potential for T&H, EO has surprisingly provoked little interest from T&H researchers. Fu et al. (Citation2019, p. 2) suggest that future research should be focused on subfields of entrepreneurship literature applied to T&H.

In the case of other crises, previous studies have shown that firms respond through organisational actions to adapt to shifting environmental pressures (Chattopadhyay et al., Citation2001). However, managers act on perceptions (Collier et al., Citation2004, p. 76), and ‘…even if their perceptions are totally inconsistent with reality, they are likely to act as if they were true’. Therefore, managers’ perceptions of the external environment, including their market recovery perception (MRP) after a crisis, can influence their decision-making and strategic planning. However, Morrish and Jones (Citation2020) claim that there is a relevant gap in the literature concerning recovery strategies those smaller firms employ. Kusa et al. (Citation2022) concur that there are still many questions related to how managers cope with the challenges caused by crises, namely changes in market conditions that require further research and analysis.

Although recent papers have addressed COVID-19 from a business recovery standpoint (e.g. Caballero-Morales, Citation2021; Fabeil et al., Citation2020; Katare et al., Citation2021), including the case of T&H firms (e.g. Sobaih et al., Citation2021; Yeh, Citation2021), few studies explore how T&H firms’ EO and MRP relate to the recovery actions taken during the pandemic. As Dias et al. (Citation2022), who found entrepreneurship-related indicators relevant to selecting recovery strategies, pointed out, future research should focus on understanding how entrepreneurs may pursue specific strategies.

These gaps are especially relevant due to the large scale of this crisis, making it dissimilar to other global shocks in terms of its impact on the macro and micro environments of T&H firms. To answer them, we strive to advance knowledge on entrepreneurship in T&H by answering the following research questions: ‘How do T&H firms differ in terms of entrepreneurial orientation and managers’ market recovery perception in the COVID-19 pandemic context?’ ‘How different were those types of firms’ responses to the pandemic?’

Our study makes several contributions. First, we contribute to entrepreneurship studies in T&H by showing that these firms may be categorised into three types according to the interaction between EO and MRP. One type of firm presents high levels of both EO and MRP; another type is characterised by low EO and moderate MRP, and the third type shows high EO and Low MRP. Second, we spotlight how that interaction is related to the actions taken by firms to respond to the consequences of the pandemic. Third, concerning practical implications, our work lists firms’ main actions to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, which may serve as a benchmark for T&H managers. Finally, we call on T&H managers and entrepreneurs to assess the level of EO in the face of potential future crises and be conscious of the role of their own perception on managerial decisions.

Our paper is organised as follows. The next two sections address how COVID-19 affected T&H and how EO and MRP have been studied in the literature. The method, findings, and discussion sections follow. The paper concludes by presenting theoretical and practical implications, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

The consequences of COVID-19 for tourism and hospitality

Tourism is one of the most relevant social and economic activities and certainly one of the most promising for the future (Fletcher et al., Citation2017). Before the COVID-19 pandemic, T&H contributed to more than 10% of the world’s GDP and provided more than three hundred million jobs worldwide (UNWTO, Citation2022). With its multifaceted consequences, tourism is vital to stimulate many other economic activities (Okafor & Yan, Citation2022). During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was an entire stoppage in the tourist system; hotels, restaurants, entertainment establishments, and several tourist attractions were left without activity (Gössling et al., Citation2020; Niewiadomski, Citation2020). The pandemic caused a severe collapse in tourism (Sigala & Utkarsh, Citation2021), from which some countries have not yet totally recovered. Many T&H firms closed, and many others significantly reduced their activities, with consequences on profits (Okafor & Yan, Citation2022).

By its very definition, tourism is about movement. According to the United Nations World Tourism Organization, ‘Tourism is a social, cultural and economic phenomenon involving the movement of people to countries or places outside their usual environment for personal or business/professional purposes’ (UNWTO, Citation2022). Some travellers consider the tourism movement pleasurable, which is sometimes the main reason for travelling. For others, tourism movement is the price you pay to reach your desired destination. However, for both groups, it means an accepted risk of contagion, considering the lessons learned from other episodes of health crisis and more so from COVID-19 (Nazneen et al., Citation2022), as well as other risks.

Especially after the ‘episode of 9/11’, travellers had to familiarise themselves with security threats; security checkpoints at airports—the same at some ports and railway stations—have become routine and even expected (Spalding, Citation2016). However, the magnitude of COVID-19 raised another primary concern: health security, both at the terminals and in the various means of transportation. Travelling became a decision that involved some reflection and private internal negotiation about the level of risk the traveller accepted (Valencia & Crouch, Citation2008).

Now, in most destinations, life has returned to its pre-COVID-19 context. Indeed, most people were eager to ‘get their lives back’, which often implied their right to travel and be a tourist (Zhang et al., Citation2021). In some cases, it meant the so-called revenge tourism. However, for some people who avoid all kinds of risks—usually older adults, but not just these—the management of health-related risks is, in many cases, still a critical factor in their travelling decisions (Fotiadis et al., Citation2021)—visiting one place and not another, accepting or avoiding high season, among others.

Therefore, tourism after COVID-19 is still a mystery to be solved (Deep et al., Citation2021). Despite the sector’s apparent recovery, some questions remain open. Will both sides of the tourism system, demand and supply, return to the old methods and practices for the products and destinations already known (following the idea that a successful model must not be changed)? Alternatively, will they tend to take this opportunity to reinforce some new solutions, for example, related to sustainability and sound environmental practices, or accessibility for all (Wee et al., Citation2021), or to an increased use of technology to facilitate contactless interactions and a focus on health and safety measures (Rahimizhian & Irani, Citation2020)?

In this study, we focus on the side of supply and how managerial models and perceptions may be relevant to studying how T&H firms responded to COVID-19, hopefully shedding some light on preparing for future crises.

The external environment and entrepreneurial orientation

EO refers to a tendency to engage in innovation, proactiveness, and risk-taking (Wang et al., Citation2020). It relates to processes, practices, and decision-making activities that lead to new products, services, technological innovations, markets, or business model innovations (Covin & Wales, Citation2019). EO is essential for firms where innovation is an important source of differentiation and a determinant of competitiveness. Developing products, processes, and organisational innovations supported by new technologies requires an entrepreneurial orientation. Therefore, these developments are essential indicators of EO (Jiang et al., Citation2018).

The study of EO emerged within the research on strategic orientation. According to Matsuno et al. (Citation2002), ‘the literature reveals several different terms, such as entrepreneurial proclivity (e.g. Pellissier & Van Buer, Citation2011), entrepreneurial orientation (e.g. Lumpkin & Dess, Citation1996), and entrepreneurial management (e.g. Stevenson & Jarillo, Citation2007), that are used interchangeably to describe the equivalent generalised concept’ (p. 19). EO conceptualisation has been evolving, and its study has increased recently (Freixanet et al., Citation2021; Wales et al., Citation2021). Despite all this interest, there is still no consensus in the literature about the EO construct. Seminal studies measured EO using three dimensions: innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking (Miller, Citation1983). Later, two more dimensions were introduced: autonomy and competitive aggressiveness (Lumpkin & Dess, Citation1996). Literature reviews show that some authors use only three dimensions (e.g. Amin, Citation2015; Chenuos & Maru, Citation2015), while others use five (e.g. Zehir et al., Citation2015).

Notwithstanding, several studies have examined the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation (EO) and performance. Although some contradictory empirical results exist, Rauch et al. (Citation2009), in their meta-analysis, found that EO was positively related to performance. Other studies show that internal and external moderators affect the EO-performance relationship (Freixanet et al., Citation2021). Some of these moderators are the environment (Escribá-Esteve et al., Citation2008), national culture (Brettel et al., Citation2015), networking (Su et al., Citation2015), and open innovation (Freixanet et al., Citation2021), to name a few.

Previous research has shown that firms with higher entrepreneurial orientation have been more innovative and effective when dealing with crises and emergencies (Soininen et al., Citation2012). More proactive and innovative firms have greater chances to survive economic crises. In the T&H literature, the role of entrepreneurial orientation in dealing with the uncertainty of the tourism sector has been highlighted in previous research (Tang et al., Citation2020). Despite the different perspectives on the contribution of the various dimensions of EO to performance, some authors (e.g. Hjalager, Citation2010; Tajeddini, Citation2011) conclude that innovative activities significantly and positively affect performance in the hotel industry. More recently, Tajeddini et al. (Citation2020) confirmed EO as a predictor of performance in T&H.

The external environment is also an essential factor influencing firms’ performance. During the last decade, researchers have maintained their interest in exploring relationships between the environment and EO or between EO and performance as affected by the external environment (Martins & Rialp, Citation2013; Tajeddini et al., Citation2020). For these authors, EO emerges as a resource or a vital catalyst for entrepreneurs to operate successfully in competitive, uncertain, and dynamic environments. Entrepreneurial orientation has been shown to improve firm performance in shifting and changing environments (Rosenbusch et al., Citation2013). More recently, Zighan et al. (Citation2022) showed how SMEs’ EO helped in understanding and developing mitigation actions against the hardships of the pandemic.

In T&H literature, some studies have identified specific factors in the external environment that may impact EO. For example, Tajeddini et al. (Citation2020) found the role of environmental dynamism. Similarly, Taheri et al. (Citation2019) studied EO in market turbulence, and Fadda and Sørensen (Citation2017) studied how destination attractiveness and EO influence firm performance. Also, in their studies of SMEs, Martins and Rialp (Citation2013) conclude that EO’s impact on profitability is higher when there is an EO-external environment fit.

Managers’ perception of market recovery and entrepreneurial orientation

Market recovery has been a concern of academics in many previous disasters that affected tourism (e.g. Bujosa et al., Citation2015; Carlsen & Hughes, Citation2008; Carlsen & Liburd, Citation2008; Mair et al., Citation2016; Walters & Mair, Citation2012). Despite the large body of research on tourism marketing recovery strategies after crises or disasters, mainly concerning disasters such as earthquakes, tsunamis, and influenza, market recovery in tourism has become a top priority during the pandemic when how to develop effective recovery strategies has become an urgent issue (Luo et al., Citation2021).

The strategic management literature stresses the role of managerial perception in decision-making and strategy formulation (Özleblebici & Çetin, Citation2015). On the other hand, the managerial cognition literature suggests that because of bounded rationality, top managers develop subjective representations of the environment that guide their strategic decisions and firm action (Fiol & O’Connor, Citation2003). More specifically, it is accepted by many scholars that the way managers perceive the environment is more important than the actual environment (Freel, Citation2005).

This happened with COVID-19 since, to some extent, T&H managers could not objectively predict how the external environment would evolve in many of its components (e.g. the number of COVID-19 cases, regulatory decisions on travel restrictions, and consumer behaviour). Therefore, managers develop individual perceptions of uncertainty, including those related to market recovery (MRP).

On the other hand, some firms engage in more entrepreneurial activities than others. One of the reasons for this may be in managerial perceptions of the competitive environment, based on the view that these perceptions influence how managers frame the issues facing their firm and its actions (Simsek et al., Citation2007). Firms with higher EO are more proactive in seeking new opportunities and can better adapt to changing market conditions (Rauch et al., Citation2009). There is also evidence to suggest that firms with high levels of EO may be more resilient during times of market downturn. For instance, Covin and Slevin (Citation1991) propose that EO is positively related to a firm’s effort to predict market trends and is more positively associated with firm performance among firms that emphasise predicting trends. Due to their innovative and proactive approach to business, these firms may better weather the storm and emerge stronger on the other side. In T&H literature, there are also studies on how managers’ perceptions of the environment influence their strategic decisions (Jogaratnam & Wong, Citation2009), including entrepreneurial activities (Jogaratnam, Citation2002) and its influence on firm performance (Köseoglu et al., Citation2013). Finally, for López-Gamero et al. (Citation2010), proactive environmental management influences financial performance, and financial performance impacts proactive environmental management.

Overall, the general literature suggests that EO can positively impact firms’ performance during environmental uncertainty and that managerial perceptions can influence their engagement in EO behaviours. In T&H literature, results point in the same direction. T&H firms have had to take recovery actions to adapt to the changing market conditions and mitigate the pandemic’s adverse effects. One expects those actions to vary according to each firm’s interaction between its EO and MRP. Therefore, based on the review of the literature, we developed the following propositions to be tested:

P1—T&H firms may be organised into different types according to the combination of the level of EO with the level of MRP.

P2—Recovery actions differ across the resulting types of T&H firms, as the combination of each company’s level of EO and MRP will translate, in practice, into specific choices of recovery actions.

Methods

The study follows a deductive research approach. A quantitative research strategy and a descriptive research design were used. Data was collected through a survey of T&H managers.

Research instrument and variables

The questionnaire measured entrepreneurial orientation (EO) and market recovery perception (MRP). The questionnaire included a list of potential recovery actions. Three characterisation variables were included: sector, firm size, and firm age.

Entrepreneurial orientation/proclivity

This study used Matsuno et al. (Citation2002) 3-dimensional scale. Although the authors prefer the term ‘entrepreneurial proclivity,’ they define it as ‘the organisation’s predisposition to accept entrepreneurial processes, practices, and decision making, characterised by its preference for innovativeness, risk taking, and proactiveness’ (Matsuno et al., Citation2002, p. 19). Respondents rated their firm’s EO using a 5-point Likert-type scale. One item had to be removed from the EP scale in our sample due to non-significant factor loadings. After the removal of that item, the scale presented adjustment indexes within the critical values: comparative fit index (CFI) = .924 (>0.9), and Bentler-Bonett Normed Fit Index (NFI) = .904 (>0.9).

Market recovery perception

According to Wernerfelt and Karnani (Citation1987), perceived environmental uncertainty can be measured based on four dimensions: demand, supply, the intensity of competition, and external factors. In this paper, we decided to focus on the uncertainty of market recovery, which depends on external factors (to the industry), one of those four dimensions. Therefore, respondents were asked how they agreed with the following statement: ‘Firm’s managers consider that, in 6 months, the sector will register demand levels at least equal to 2019,’ using a 5-point Likert-type scale.

Recovery actions

Respondents were asked to choose from a list of 13 possible actions, the three most relevant the firm had taken to recover business during the pandemic’s peak. Respondents could also answer ‘none’ or add new actions not considered in the list. The list of actions provided was based on Costa et al. (Citation2021).

Firm size

Firm size was measured in five ranks: (1) from 10 to 14 employees; (2) from 15 to 29 employees; (3) from 30 to 49 employees; (4) from 50 to 249 employees; and (5) 250 or more employees. Firm size was included in our study because smaller companies were more affected by COVID-19 due to their limited resources when compared with large companies (Pedauga et al., Citation2021).

Firm age

Firm age corresponds to the difference between 2021 and the year of the firm’s foundation. This variable was included because as firms age, they tend to be less entrepreneurial (Gürbüz & Aykol, Citation2009).

Sample

We chose to study T&H firms in Portugal due to the country’s increasing relevance as a tourism destination. Portugal ranked 16th globally in the Travel & Tourism Development Index (World Economic Forum, Citation2022) in 2021; it was named the Leading Destination in Europe for four consecutive years (2017–2020) and again in 2022 and 2023 at the World Travel Awards.Footnote1

To arrive at our sample, we used the Portuguese Tourism National Registry (PTNR),Footnote2 which includes different T&H sectors. Two emails were sent inviting to participate in the study, the first in July 2021 and the second in September 2021. A total of 69 firms with 10+ employees participated in the study. These are firms from the accommodation sector (69.6%), travel agencies/tour operators (5.8%) and amusement and recreation activities (8.7%). 11 firms confirmed to belong to T&H but did not indicate the subsector. The mean age of firms is 26 years. 25% of firms are less than 9.5 years of age, and 25% have more than 38 years. Approximately 50% of firms are very small (10 to 29 employees), 21.7% have 30 to 49 employees, and 18.8% are medium-sized. Five are large firms (7.2%) with 250 or more employees.

We chose to rely on single key informants for our data collection, following Huber and Power (Citation1985) guidelines for obtaining quality data from single informants. We targeted senior managers since they are the most knowledgeable regarding their firm’s strategies, namely its entrepreneurial orientation (Covin & Wales, Citation2019).

Findings and discussion

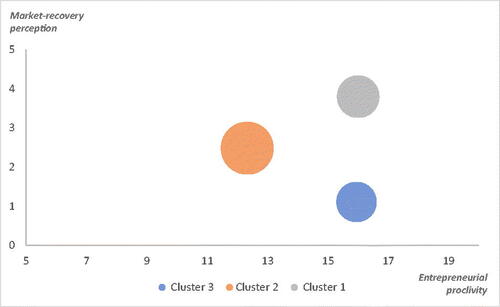

We conducted a cluster analysis to test our propositions considering two clustering variables: EO and MRP. Three clusters emerged according to different combinations of the level of EO with the level of MRP (). Therefore, evidence from results allows the validation of P1—T&H firms may be organised into different types according to the combination of the level of EO with the level of MRP. The confirmed clusters correspond to firms with High EO + High MRP (cluster 1; 20 firms), Low EO + Moderate MRP (cluster 2; 31 firms), and High EO + Low MRP (Cluster 3; 18 firms).

When investigating which variables distinguish between the different types of firms, we found that these included the two clustering variables - EO (sig. < 0.001) and MRP (sig. < 0.001). These results are consistent with other authors, considering that EO depends on the external environment (Martins & Rialp, Citation2013; Tajeddini et al., Citation2020) and how managers perceive it (Simsek et al., Citation2007).

Firm size (sig. = 0.456) and firm age (sig. = 0.305) are not significantly different between clusters. Concerning firm size, this result might be related to the characteristics of the sample in this study, where the majority is small. Regarding firm age, our results do not reveal differences in EO according to age; cluster 2 (Low EO) is not significantly different from clusters 1 and 3 (High EO) regarding firm age. This result is contrary to what would be expected according to the literature (Gürbüz & Aykol, Citation2009).

To test our second proposition, we compared the actions taken by the firms in each cluster. presents the actions taken by each cluster and the totality of the sample. In , the actions taken by more than 50% of each cluster’s members are highlighted.

Table 1. Actions taken by firms in each cluster—in percentage.

When looking at the results for the whole sample (last column, to the right), one may observe that the most common actions adopted by most T&H firms were sanitation measures, marketing communication actions, and product/service changes. We should notice that, in Portugal, many sanitation measures were mandatory. However, many firms took additional sanitation measures to obtain the Clean & Safe badge from Turismo de Portugal (the Portuguese National Tourism Board), a badge given to firms that complied with the suggested measures. Regarding marketing communication actions and product/service changes, results are congruent with Mair et al. (Citation2016), who found in their literature review that marketing strategies should be a primary focus in the disaster recovery phase.

Differences can be observed between clusters regarding the chosen recovery actions, giving support to P2—Recovery actions differ across the resulting types of T&H firms, as the combination of each company’s level of EO and MRP will translate, in practice, into specific choices of recovery actions. One of those differences concerns product/service changes, where a lower percentage of firms from cluster 2 (Low EO + Moderate MRP) took that measure. The percentage of firms with high EO that changed their products/services was higher than that of firms with low EO that took it. This result is consistent with Seetharaman (Citation2020), who argues that the COVID-19 economic crisis posed challenges and provided marketing innovation, including launching competitive products to survive the crisis.

Other differences concern changes in staff profile, partnership development, and remodelling/construction work. A smaller percentage of firms in cluster 2 changed staff profile compared to clusters 1(High EO + High MRP) and 3 (High EO + Low MRP). A lower percentage of firms in Clusters 2 and 3 opted to develop partnerships or to have remodelling/construction work compared to those from Cluster 1 that took those actions.

Additionally, different actions were taken depending on firms’ levels of EO and MRP. Firms with higher levels of EO and MRP (cluster 1) developed a higher number of recovery actions (five), including partnership development, product/service changes, sanitation measures, changes in staff size, and marketing communication actions. Firms with a higher level of EO but a lower level of MRP develop a smaller number of measures (three), product/service changes, sanitation measures, and marketing communication actions. Finally, firms with a lower level of EO and a moderate level of MRP develop even fewer measures (two), sanitation measures and marketing communication actions. The fact that firms in cluster 1 took more recovery actions is coherent with the literature postulating that certain firms with high levels of EO are more likely to succeed during market recovery (Covin & Slevin, Citation1991). Others also conclude that these types of firms (high levels of EO) tend to be more proactive and more able to explore new opportunities and adapt to changing market conditions (Rauch et al., Citation2009). Results are also consistent with the T&H literature. T&H firms with higher EO develop specific actions that affect their performance (Hjalager, Citation2010; Tajeddini, Citation2011; Tajeddini et al., Citation2020). The differences in the actions taken by firms in Cluster 1 (high MRP), when compared to Clusters 2 (moderate MRP) and 3 (low MRP), are also consistent with Jogaratnam (Citation2002). This author found that firms tend to be more conservative when the environment becomes more hostile (or is perceived that way, we add).

In summary, our results suggest that high EO translates into more recovery actions when firms have a positive outlook on environmental uncertainty (High MRP). On the one hand, firms with a more optimistic MRP were likelier to develop partnerships. On the other hand, firms with a higher EO were more likely to engage in innovation, launching new products/services and, probably as a consequence, changing the profile of employees, often by providing training to employees and/or letting go of lower performant employees.

Conclusions

This study addresses a gap in the literature on how T&H firms’ entrepreneurial orientation and managers’ perception of the external environment, namely market recovery perception, relate to the recovery actions taken during the pandemic. This gap is especially relevant due to the large scale of this crisis, making it dissimilar to other global shocks in terms of its impact on T&H firms.

Therefore, in this study, we aimed to study how T&H firms differ regarding entrepreneurial orientation and managers’ market recovery perception in the COVID-19 pandemic context and how different those types of firms’ responses to the pandemic were. Results suggest that there are three different types of T&H firms, according to their levels of EO and MRP - High EO + High MRP (cluster 1), Low EO + Moderate MRP (cluster 2), and High EO + Low MRP (cluster 3). We also concluded that these three different types of firms opted for diverse recovery actions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our work has important theoretical and practical implications that we describe below.

Theoretical implications

COVID-19 highly impacted T&H firms in a dissimilar way to other shocks, and, in the future, the sector will not be exempted from other global and prolonged crises, namely other pandemics. Regarding business recovery from external crises, EO and MRP might be relevant constructs to study, but few studies in T&H have addressed them. Therefore, this paper adds to the knowledge by reducing the gap on how T&H firms’ EO and MRP relate to the recovery actions taken during the pandemic.

Results suggest that firms may be categorised into three different types according to the levels of EO and MRP. This has significant implications for studying future crises in T&H. Our results suggest that high EO translates into more recovery actions when firms have a positive outlook on environmental uncertainty.

Second, we spotlight how that interaction is related to the actions taken by firms to respond to the consequences of the pandemic. For instance, our results reveal that firms with a more optimistic view of the external environment were likelier to engage in partnership development. Firms with higher entrepreneurial orientation were likelier to innovate, launch new products/services, and develop employees’ skills.

Practical implications

Concerning practical implications, our work lists the most common actions T&H firms took to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, which may serve as a benchmark for T&H managers. The most common actions adopted by most T&H firms were sanitation measures, marketing communication actions, and product/service changes. Secondly, by identifying different levels of entrepreneurial orientation in the industry, we call on T&H managers to assess their firm’s level of entrepreneurial orientation and how it may be hindering/fostering the firm’s resilience for future crises that might affect T&H. This is relevant for firms because EO has been found to relate to performance positively. Finally, clusters with different levels of MRP highlight the role of managerial perceptions. Therefore, managers must be more self-aware, considering how their subjective representations of the environment drive their strategic decisions and firm actions.

This study also offers significant implications for entrepreneurs as the results suggest that high EO increases the potential for recovery and performance during a crisis. Moreover, entrepreneurs should be aware of how they perceive crises and the environment and how this perception may impact entrepreneurial activities. Finally, entrepreneurs must be prepared for environmental uncertainty and understand the threats and opportunities that may emerge during crises. Being prepared implies more innovativeness, proactiveness and capacity to take risks and implement successful contingency plans.

Limitations and future research

One of the limitations of this study is related to the sample size. The sample is also not very diversified in sectors, with most firms from the accommodation sector. Another limitation is that the sample mainly included small-sized firms.

Future research might focus on replicating the study with a more stratified sample by sector and firm size. The replication of this study in other countries is also relevant for future research. The same approach may also be used to study other crises affecting T&H, namely of different types (e.g. financial, political instability, and natural disasters), to compare the relevance of entrepreneurial management and managerial perceptions beyond COVID-19. Future research should also study whether the clusters have performance and structural differences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maria de Lurdes Calisto

Maria de Lurdes Calisto holds a PhD in management. She is an assistant professor at ESHTE and a researcher at CiTUR and CEFAGE. She has experience as PI and co-PI in competitive research projects. Her research interests include innovation, entrepreneurship and strategy. Her research has been published in several international journals.

Teresa Costa

Teresa Costa holds a PhD in management and a Post-doctorate from USP. She is a coordinator professor at IPSetúbal. She is a researcher at CiTUR and an invited professor at several international universities where she collaborates in master’s and doctoral programs. Her research has been published in several international journals.

Jorge Umbelino

Jorge Umbelino holds a PhD in geography and is a full professor at ESHTE. He is a researcher at CiTUR and CEG/ULisboa-IGOT. His scientific interests are tourism planning and accessible tourism. He was President of the Institute for Tourism Training, Board Member of the Tourism National Authority and deputy director for Tourism.

Notes

2 Available at https://registos.turismodeportugal.pt/.

References

- Alebaki, M., & Ioannides, D. (2017). Threats and obstacles to resilience: Insights from Greece’s wine tourism. In Tourism, resilience, and sustainability: Adapting to social, political and economic change (pp. 1–13) Routledge.

- Amin, M. (2015). The effect of entrepreneurship orientation and learning orientation on SMEs’ performance: An SEM-PLS approach. J. for International Business and Entrepreneurship Development, 8(3), 215–230. https://doi.org/10.1504/JIBED.2015.070797

- Boers, B., & Henschel, T. (2022). The role of entrepreneurial orientation in crisis management: Evidence from family firms in enterprising communities. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 16(5), 756–780. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-12-2020-0210

- Brettel, M., Chomik, C., & Flatten, T. C. (2015). How organisational culture influences innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking: Fostering entrepreneurial orientation in SMEs. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(4), 868–885. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12108

- Bujosa, A., Riera, A., & Torres, C. M. (2015). Valuing tourism demand attributes to guide climate change adaptation measures efficiently: The case of the Spanish domestic travel market. Tourism Management, 47, 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.09.023

- Caballero-Morales, S. O. (2021). Innovation as recovery strategy for SMEs in emerging economies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Research in International Business and Finance, 57, 101396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2021.101396

- Carlsen, J. C., & Hughes, M. (2008). Tourism market recovery in the Maldives after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 23(2–4), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v23n02_11

- Carlsen, J. C., & Liburd, J. J. (2008). Developing a research agenda for tourism crisis management, market recovery and communications. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 23(2–4), 265–276. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v23n02_20

- Chattopadhyay, P., Glick, W., & Huber, G. (2001). Organisational actions in response to threats and opportunities. Academy of Management Journal, 44(5), 937–955. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069439

- Chenuos, N. K., & Maru, C. L. (2015). Learning orientation and innovativeness of small and micro enterprises. International Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship Research, 3(5), 1–10.

- Collier, N., Fishwick, F., & Floyd, S. W. (2004). Managerial involvement and perceptions of strategy process. Long Range Planning, 37(1), 67–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2003.11.012

- Costa, T. G., Calisto, M. L., & Umbelino, J. (2021). COVID-19 and the resilience of tourism businesses in Portugal. In Costa, T. G., I. Lisboa, and N. M. Teixeira (Eds.), Handbook of research on reinventing economies and organisations following a global health crisis (pp. 1–15). IGI Global.

- Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (1991). A conceptual model of entrepreneurship as firm behavior. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 16(1), 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879101600102

- Covin, J. G., & Wales, W. J. (2019). Crafting high-impact entrepreneurial orientation research: Some suggested guidelines. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 43(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258718773181

- Deep, G., Thomas, A., & Paul, J. (2021). Reviving tourism industry post-COVID-19: A resilience-based framework. Tourism Management Perspectives, 37, 100786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100786

- Dias, Á. L., Silva, R., Patuleia, M., Estêvão, J., & González-Rodríguez, M. R. (2022). Selecting lifestyle entrepreneurship recovery strategies: A response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 22(1), 115–121.

- Duchek, S. (2020). Organisational resilience: A capability-based conceptualisation. Business Research, 13(1), 215–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40685-019-0085-7

- Escribá-Esteve, A., Sánchez-Peinado, L., & Sánchez-Peinado, E. (2008). Moderating influences on the firm’s strategic orientation-performance relationship. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 26(4), 463–489. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242608091174

- Fabeil, N. F., Pazim, K. H., & Langgat, J, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Malaysia. (2020). The impact of covid-19 pandemic crisis on micro-enterprises: Entrepreneurs’ perspective on business continuity and recovery strategy. Journal of Economics and Business, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.31014/aior.1992.03.02.241

- Fadda, N., & Sørensen, J. F. L. (2017). The importance of destination attractiveness and entrepreneurial orientation in explaining firm performance in the Sardinian accommodation sector. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(6), 1684–1702. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2015-0546

- Fiol, C. M., & O’Connor, E. J. (2003). Waking up! Mindfulness in the face of bandwagons. Academy of Management Review, 28(1), 54–70. https://doi.org/10.2307/30040689

- Fletcher, J., Fyall, A., Gilbert, D., & Wanhill, S. (2017). Tourism: Principles and practice (6th ed.). Person.

- Fotiadis, A., Polyzos, S., & Huan, T. T. C. (2021). The good, the bad and the ugly on COVID-19 tourism recovery. Annals of Tourism Research, 87, 103117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103117

- Freel, M. S. (2005). Perceived environmental uncertainty and innovation in small firms. Small Business Economics, 25(1), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-005-4257-9

- Freixanet, J., Braojos, J., Rialp-Criado, A., & Rialp-Criado, J. (2021). Does international entrepreneurial orientation foster innovation performance? The mediating role of social media and open innovation. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 22(1), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465750320922320

- Fu, H., Okumus, F., Wu, K., & Köseoglu, M. A. (2019). The entrepreneurship research in hospitality and tourism. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 78, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.10.005

- Ghaderi, Z., Mat Som, A. P., & Henderson, J. C. (2015). When disaster strikes: The Thai floods of 2011 and tourism industry response and resilience. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 20(4), 399–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2014.889726

- Gibson, C. A., & Tarrant, M. (2010). A ‘conceptual models’ approach to organisational resilience. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 25(2), 6–12.

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2020). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

- Gürbüz, G., & Aykol, S. (2009). Entrepreneurial management, entrepreneurial orientation and Turkish small firm growth. Management Research News, 32(4), 321–336. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409170910944281

- Hjalager, A. M. (2010). A review of innovation research in tourism. Tourism Management, 31(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.08.012

- Huber, G. P., & Power, D. J. (1985). Retrospective reports of strategic-level managers: Guidelines for increasing their accuracy. Strategic Management Journal, 6(2), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250060206

- Islam, T., Pitafi, A. H., Arya, V., Wang, Y., Akhtar, N., Mubarik, S., & Xiaobei, L. (2021). Panic buying in the COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-country examination. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 59, 102357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102357

- Jiang, W., Chai, H., Shao, J., & Feng, T. (2018). Green entrepreneurial orientation for enhancing firm performance: A dynamic capability perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, 198, 1311–1323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.104

- Jogaratnam, G. (2002). Entrepreneurial orientation and environmental hostility: An assessment of small, independent restaurant businesses. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 26(3), 258–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348002026003004

- Jogaratnam, G., & Wong, K. K. (2009). Environmental uncertainty and scanning behavior: An assessment of top-level hotel executives. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 10(1), 44–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480802557275

- Katare, B., Marshall, M. I., & Valdivia, C. B. (2021). Bend or break? Small business survival and strategies during the COVID-19 shock. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction: IJDRR, 61, 102332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102332

- Köseoglu, M. A., Topaloglu, C., Parnell, J. A., & Lester, D. L. (2013). Linkages among business strategy, uncertainty and performance in the hospitality industry: Evidence from an emerging economy. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 34, 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.03.001

- Kusa, R., Duda, J., & Suder, M. (2022). How to sustain company growth in times of crisis: The mitigating role of entrepreneurial management. Journal of Business Research, 142, 377–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.12.081

- Laskovaia, A., Marino, L., Shirokova, G., & Wales, W. (2019). Expect the unexpected: Examining the shaping role of entrepreneurial orientation on causal and effectual decision-making logic during economic crisis. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 31(5-6), 456–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2018.1541593

- López-Gamero, M. D., Molina-Azorín, J. F., & Claver-Cortés, E. (2010). The potential of environmental regulation to change managerial perception, environmental management, competitiveness and financial performance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 18(10-11), 963–974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2010.02.015

- Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. The Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 135–172. https://doi.org/10.2307/258632

- Luo, Y., Li, Y., Wang, G., & Ye, Q. (2021). Agent-based modeling and simulation of tourism market recovery strategy after COVID-19 in Yunnan, China. Sustainability, 13(21), 11750. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111750

- Mair, J., Ritchie, B. W., & Walters, G. (2016). Towards a research agenda for post-disaster and post-crisis recovery strategies for tourist destinations: A narrative review. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2014.932758

- Martins, I., & Rialp, A. (2013). Orientación emprendedora, hostilidad del entorno y la rentabilidad de la Pyme: Una propuesta de contingencias. Cuadernos de Gestión, 13(2), 67–88. https://doi.org/10.5295/cdg.110297iz

- Matsuno, K., Mentzer, J. T., & Özsomer, A. (2002). The effects of entrepreneurial proclivity and market orientation on business performance. Journal of Marketing, 66(3), 18–32. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.66.3.18.18507

- Miller, D. (1983). The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Management Science, 29(7), 770–791. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.29.7.770

- Morrish, S. C., & Jones, R. (2020). Post-disaster business recovery: An entrepreneurial marketing perspective. Journal of Business Research, 113, 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.03.041

- Nazneen, S., Xu, H., Din, N. U., & Karim, R. (2022). Perceived COVID-19 impacts and travel avoidance: Application of protection motivation theory. Tourism Review, 77(2), 471–483. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-03-2021-0165

- Niewiadomski, P. (2020). Covid-19: From temporary de-globalisation to a re-discovery of tourism? Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 651–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1757749

- Okafor, L., & Yan, E. (2022). Covid-19 vaccines, rules, deaths, and tourism recovery. Annals of Tourism Research, 95, 103424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2022.103424

- Orchiston, C., & Higham, J. E. S. (2016). Knowledge management and tourism recovery (de) marketing: The Christchurch earthquakes 2010–2011. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(1), 64–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2014.990424

- Özleblebici, Z., & Çetin, Ş. (2015). The role of managerial perception within strategic management: An exploratory overview of the literature. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 207, 296–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.10.099

- Pedauga, L., Sáez, F., & Delgado-Márquez, B. L. (2021). Macroeconomic lockdown and SMEs: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Small Business Economics, 58(2), 665–688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00476-7

- Pellissier, J. M., & Van Buer, M. G. (2011). Entrepreneurial proclivity and the interpretation of subjective probability phrases. Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR), 12(4), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.19030/jabr.v12i4.5789

- Rahimizhian, S., & Irani, F. (2020). Contactless hospitality in a post-Covid-19 world. International Hospitality Review, 35(2), 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1108/IHR-08-2020-0041

- Rauch, A., Wiklund, J., Lumpkin, G. T., & Frese, M. (2009). Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: An assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 761–787. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00308.x

- Rosenbusch, N., Rauch, A., & Bausch, A. (2013). The mediating role of entrepreneurial orientation in the task environment–performance relationship: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management, 39(3), 633–659. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311425612

- Scheidgen, K., Gümüsay, A. A., Günzel-Jensen, F., Krlev, G., & Wolf, M. (2021). Crises and entrepreneurial opportunities: Digital social innovation in response to physical distancing. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 15, e00222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2020.e00222

- Seetharaman, P. (2020). Business models shifts: Impact of Covid-19. International Journal of Information Management, 54, 102173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102173

- Sheppard, V. A., & Williams, P. W. (2016). Factors that strengthen tourism resort resilience. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 28, 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2016.04.006

- Sigala, Marianna & Utkarsh, 2021, "Bibliometric review of research on COVID-19 and tourism: Reflections for moving forward". Tourism Management Perspectives, 40, 100912 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100912

- Simsek, Z., Veiga, J. F., & Lubatkin, M. H. (2007). The impact of managerial environmental perceptions on corporate entrepreneurship: Towards understanding discretionary slack’s pivotal role. Journal of Management Studies, 44(8), 1398–1424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00714.x

- Sobaih, A. E. E., Elshaer, I., Hasanein, A. M., & Abdelaziz, A. S. (2021). Responses to COVID-19: The role of performance in the relationship between small hospitality enterprises’ resilience and sustainable tourism development. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102824

- Soininen, J., Puumalainen, K., Sjögrén, H., & Syrjä, P. (2012). The impact of global economic crisis on SMEs: Does entrepreneurial orientation matter? Management Research Review, 35(10), 927–944. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409171211272660

- Spalding, S. J. (2016). Airport outings: The coalitional possibilities of affective rupture. Women’s Studies in Communication, 39(4), 460–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/07491409.2016.1227415

- Stevenson, H. H., & Jarillo, J. C. (2007). A paradigm of entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurial management. In Entrepreneurship: Concepts, theory and perspective (pp. 155–170). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Su, Z., McDonnell, D., Cheshmehzangi, A., Abbas, J., Li, X., & Cai, Y. (2021). The promise and perils of Unit 731 data to advance COVID-19 research. BMJ Global Health, 6(5), e004772. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004772

- Su, Z., Xie, E., & Wang, D. (2015). Entrepreneurial orientation, managerial networking, and new venture performance in China. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(1), 228–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12069

- Taheri, B., Bititci, U., Gannon, M. J., & Cordina, R. (2019). Investigating the influence of performance measurement on learning, entrepreneurial orientation and performance in turbulent markets. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(3), 1224–1246. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-11-2017-0744

- Tajeddini, K. (2011). Strategic orientation in small-sized service retailers. International Journal of Strategic Change Management, 3(1/2), 90–98. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSCM.2011.040634

- Tajeddini, K., Martin, E., & Ali, A. (2020). Enhancing hospitality business performance: The role of entrepreneurial orientation and networking ties in a dynamic environment. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 90, 102605. 102605 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102605

- Tang, T. W., Zhang, P., Lu, Y., Wang, T. C., & Tsai, C. L. (2020). The effect of tourism core competence on entrepreneurial orientation and service innovation performance in tourism small and medium enterprises. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 25(2), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2019.1674346

- Tingbani, I., Okafor, G., Tauringana, V., & Zalata, A. M. (2019). Terrorism and country-level global business failure. Journal of Business Research, 98, 430–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.08.037

- United Nations World Tourism Organization—UNWTO. (2022). Data is available at https://www.unwto.org/. Accessed on January 8th, 2023

- Valencia, J., & Crouch, G. I. (2008). Travel behavior in troubled times: The role of consumer self-confidence. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 25(1), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548400802164871

- Wales, W. J., Kraus, S., Filser, M., Stöckmann, C., & Covin, J. G. (2021). The status quo of research on entrepreneurial orientation: Conversational landmarks and theoretical scaffolding. Journal of Business Research, 128, 564–577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.10.046

- Walters, G., & Mair, J. (2012). The effectiveness of post-disaster recovery marketing messages: The case of the 2009 Australian bushfires. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 29(1), 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2012.638565

- Wang, X., Dass, M., Arnett, D. B., & Yu, X. (2020). Understanding firms’ relative strategic emphases: An entrepreneurial orientation explanation. Industrial Marketing Management, 84, 151–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.06.009

- Watson, P., & Deller, S. (2022). Tourism and economic resilience. Tourism Economics, 28(5), 1193–1215. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816621990943

- Wee, B., Van, & F., Witlox. (2021). COVID-19 and its long-term effects on activity participation and travel behaviour: A multiperspective view. Journal of Transport Geography, 95, 103144. 103144 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2021.103144

- Wernerfelt, B., & Karnani, A. (1987). Competitive strategy under uncertainty. Strategic Management Journal, 8(2), 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250080209

- World Economic Forum. (2022). "The travel & tourism development index 2021—Rebuilding for a sustainable and resilient future - insight report (May 2022). Available at https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Travel_Tourism_Development_2021.pdf. Accessed January 8th, 2023

- Yeh, S. S. (2021). Tourism recovery strategy against COVID-19 pandemic. Tourism Recreation Research, 46(2), 188–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2020.1805933

- Zehir, C., Can, E., & Karaboga, T. (2015). Linking entrepreneurial orientation to firm performance: The role of differentiation strategy and innovation performance. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 210, 358–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.381

- Zhang, H., Song, H., Wen, L., & Liu, C. (2021). Forecasting tourism recovery amid COVID-19. Annals of Tourism Research, 87, 103149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103149

- Zighan, S., Abualqumboz, M., Dwaikat, N., & Alkalha, Z. (2022). The role of entrepreneurial orientation in developing SMEs resilience capabilities throughout COVID-19. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 23(4), 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/14657503211046849