Abstract

This study proposes an extended Stimulus-Organism-Response framework that investigates perceived seamlessness and product information as drivers of omni-channel shopping satisfaction, as well as the resulting consumer response outcomes. There is a specific focus on consumption and experience-sharing behaviour and on the moderating role of social media attractiveness. An online self-administered questionnaire resulted in 433 responses from South African shoppers. The hypotheses were tested using structural equation modelling and a multi-group CFA approach. Interestingly, information visibility was the strongest predictor of satisfaction. Furthermore, convenience of sharing was confirmed as a mediator, while social media attractiveness acted as moderator in the relationship between satisfaction and experience sharing. The research contributes to the fast-growing trend of omni-channel retailing, especially from a consumer perspective. While research typically focuses on consumption-sharing behaviour, this study adopted a dual-sharing perspective by investigating not only customer influence as a type of consumption behaviour sharing, but also experience sharing behaviour. The applicability of an extended S-O-R framework is confirmed in an emerging market context while providing practical insights for retailers.

Introduction

Social media and other new technologies (e.g., Artificial Intelligence (AI), augmented reality (AR), metaverse, mobile apps, etc.) are changing retailing (Cia and Lo, 2020, Asmare & Zewdie, Citation2022), and omni-channel retailing is an emerging strategy because of these changes (Hickman et al., Citation2020). Given that these new technologies are creating various opportunities in omni-channelling, it is expected to lead retailing in the future (Adhi et al., Citation2021). AI such as chatbots, augmented reality, and machine learning are fuelling the digital revolution (Pillai et al., Citation2020). AI systems can provide personalized experiences based on previous purchases and shopping patterns, leading to increased customer engagement and enhanced consumption experiences (Kaur et al., Citation2020; Pillai et al., Citation2020; Euromonitor, Citation2022). In addition, information collected through omnichannel is immense and serves as input to AI, which can then be leveraged by brands for improved decision-making (Gerea et al., Citation2021). Events such as COVID-19 have also impacted the marketing environment (Chen & Chi, Citation2021). Social media and e-commerce emerged as critical marketing channels during the pandemic (Zhang et al., Citation2018), further accelerating the worldwide expansion of omni-channel retailing (Cattapan & Pongsakornrungsilp, Citation2022).

As a result of the expansion of digital technologies and the increase in new channels (Grewal et al., Citation2016), customers now interact with brands through numerous touchpoints, resulting in more versatile and comprehensive customer shopping journeys (Edelman & Singer, Citation2015). However, to ensure an integrated seamless experience across all touchpoints remains difficult (Huré et al., Citation2017). The newness and unfamiliarity of omni-channel retailing poses a challenge for both established and new brands to be successful in this new channel (Cai & Lo, Citation2020). It is thus important to understand shoppers’ perceptions, experiences, and responses during omni-channel shopping (Verhoef et al., Citation2015).

‘Omni-channelling’ refers to a ‘synergetic management of the numerous available channels and customer touchpoints, in such a way that the customer experience across channels and the performance over channels are optimised to facilitate seamless customer journeys’ (Bijmolt et al., Citation2021). This indicates a movement away from merely providing products and services across multiple channels (multiple-channel retailing management) or cross-channel retailing that offers limited integration among the various touchpoints.

Shoppers and retailers are increasingly using social media as part of omni-channel shopping (De Keyser et al., Citation2020; Shukla, Citation2021) resulting in a more social omni-channel customer experience, and so emphasising the need to understand shoppers’ sharing behaviour (Herhausen et al., Citation2019). Sharing behaviours is a way of harnessing positive shopper responses to the benefit of the shopper, other consumers, and brands alike. Customer-to-customer interactions (e.g., sharing) are evident during the whole omni-channel shopping journey: channels are interconnected, allowing shoppers to easily change between different retail and communication touchpoints (Huré et al., Citation2017). Shoppers sharing their experiences with others on social media is significant, as it has the potential to affect others’ customer experience, whether positively or negatively (Homburg et al., Citation2017). It might not only prompt the relevant unmet needs among potential customers, but could also generate retail traffic (Kalyanam et al., Citation2018). Potential shoppers may also be more influenced by experience input from actual shoppers than by receiving similar communications from the brand or retailer (Herhausen et al., Citation2019). Last, the integration of various channels is a challenge for marketers in allocating their resources (e.g., budget and time) (Court et al., Citation2009). Research shows that brand advertising, in-store communication, and peer-to-peer encounters can be used effectively (Stephen & Galak, Citation2012; Baxendale et al., Citation2015). Yet, given limited budgets and resources, the question of where to spend money makes a favourable case for using ‘free’ or relatively lower-cost third-party own advertising (such as peer-to-peer interaction) not only more, but also more effectively. Hence our focus on third-party communication (customer influence and sharing behaviour) during the omni-channel shopping journey.

Prior omni-channel research generally focuses on a retailer’s perspective (Cai & Lo, Citation2020; İzmirli et al., Citation2021). Studies from a consumer perspective are absent (Verhoef et al., Citation2022) – especially research into shopping behaviour and channel integration perceptions (Cattapan & Pongsakornrungsilp, Citation2022). Given that a seamless experience is central to retaining and engaging omni-channel shoppers (Cai & Lo, Citation2020), delivering an integrated experience for customers is non-negotiable for retailers (Chang & Li, Citation2022). However, research on how seamlessness is evaluated by shoppers, and its impact on significant customer behaviours, remain unmapped (Chang & Li, Citation2022) and not everyone is in agreement that a seamless experience is indeed a fundamental part of an omnichannel (Gasparin et al., Citation2022). Previous research has increased our knowledge of touchpoint usage during omni-channel shopping; however, shopping journeys are yet to be linked to relevant consumer outcomes (Herhausen et al., Citation2019).

In spite of the significance of omni-channels in retailing, limited exploration of the omnichannel customer experience is evident (Gerea et al., Citation2021). It is important to appreciate the effect of customers who share their experiences with others on social media (Verhoef et al., Citation2022), yet research on how a seamless shopping journey affects omni-channel shoppers’ word of mouth on social media (sWOM) remains limited (Li & Chang, Citation2023). Cia and Lo (2020) in their systematic review of omnichannel research found that studies from Africa were almost non-existent. Furthermore, investigating retailing in developing markets are important as spending by consumers in these economies is anticipated to be greater than in developing markets (Joshi et al., Citation2022). Unfortunately, past research in the context of omni-channel retailing, especially in developing markets, has been limited (Asmare & Zewdie, Citation2022; Joshi et al., Citation2022). In addition, the role of social influence in omni-channel retailing needs more exploration (Cia & Lo 2020) as well as the attractiveness of social media pages or sites – for example, in promoting customer engagement such as sharing behaviour – has been largely overlooked, leading to a gap in the literature (Goyal et al., Citation2021).

Therefore, given that omni channel retailing requires more theory-driven research (Asmare & Zewdie, Citation2022), this study takes a consumer perspective in a developing country context to address the identified gaps. The study aims to explore the perceived seamlessness of the shopping journey and available product information as drivers of satisfaction in the omni-channel shopping journey, and the resulting consumer response outcomes (e.g., continued shopping intention), with a specific focus on the sharing aspect (experience sharing, the convenience of sharing, customer involvement) of the journey and on the moderating role of social media attractiveness. We thus consider both the journey and the outcomes, which is important for studying customer–brand relationships (Lemon & Verhoef, Citation2016). The stimulus-organism-response (S-O-R) framework is used as the theoretical underpinning (Mehrabian & Russell, Citation1974).

This study makes various important contributions. It advances retailing research, as our proposed framework for omni-channel experience sharing contributes to the literature on omni-channel management and retailing, and provides important applications for retail firms that either are providing an omni-channel experience to their customers or plan to implement an omni-channel strategy. This study extends previous omni-channel research, especially from a consumer perspective in a developing country context, and confirms the applicability of an extended S-O-R framework.

The literature review is next, followed by the methodology, the results, and the discussion. The paper concludes with the limitations and suggestions for future research.

Literature review

Theoretical framework: S-O-R

The S-O-R framework examines consumers’ behaviour by considering how the external environment (stimulus) affects consumers’ internal state (organism), which in return drives various responses (R) (Mehrabian & Russell, Citation1974). As a result, S-O-R has been used in various retail contexts such as consumer shopping (Chen & Chi, Citation2021; Lee, Citation2020), retail environments (Kumar et al., Citation2021; Yen, Citation2023) and online shopping (Kühn & Petzer, Citation2018).

In the S-O-R framework, stimulus (S) refers to marketing and environmental variables, such as retail atmospherics or channel features (Bagozzi, Citation1986; Pantano & Viassone, Citation2015). Organism (O) refers to internal activities (emotional and intellectual states) such as consumers’ perceptions (Bagozzi, Citation1986) and satisfaction (Cho et al., Citation2019). Consumer-specific behaviours such as intentions to use, browse, or purchase are considered as responses (R) (Zhu et al., Citation2020).

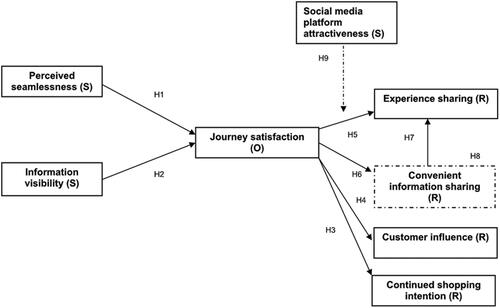

This research considers two characteristics of omni-channel shopping (a seamless experience and information visibility) and the attractiveness of social media platforms as stimuli, while satisfaction is reflected as an organism. Given that previous research has mainly focused on purchase intention (Cattapan & Pongsakornrungsilp, Citation2022), we aim to extend consumer responses, by also including sharing behaviour (in respect of experience and convenience), and customer influence behaviour.

However, the omni-channel shopping experience, the sharing of that experience as a result, and the important role of social media in sharing information are together an example of a complex, multi-faceted, and integrated context, and suggest more complex relationships than the traditional linear and sequential S-O-R framework with only direct relationships. Thus we propose an extended version of the S-O-R framework to investigate not only the traditional direct relationships but also the indirect relationships (mediators and moderators), similar to how Li et al. (Citation2021) expanded the S-O-R framework to include moderators in panic buying.

This study sets out to verify an expanded S-O-R model () by considering the mediating effect of conveniently sharing information and the moderating effect of social media platform attractiveness, in addition to the proposed direct relationships between stimuli, organism, and consumer responses.

Seamless experience (stimulus)

Omni-channel shopping offers a complete purchase experience (Quach et al., Citation2020). Switching between channels and devices is at the heart of shoppers’ omni-channel experience, and brands need to consider this in order to provide a seamless experience as omni-channel shoppers are expecting a seamless experience (Anon, Citation2024). In omni-channelling, perceived seamlessness refers to shoppers’ perception of flexibility and interaction fluency from the (Lin et al., Citation2023). There are various definitions of omni-channel shopping; however, they all point to the importance of integrating touchpoints to allow shoppers to move fluently between channels (Mosquera et al., Citation2017) and to interact seamlessly with brands across various channels. Thus, allowing shoppers a seamless shopping journey is one of the critical goals of omni-channelling (Cai & Lo, Citation2020; Gao & Huang, Citation2023).

As the differences between channels become blurred and channels become interchangeable the question arises for brands and retailers: How could they ensure satisfaction throughout all of the channels? Omni-channel shoppers could, for example, search simultaneously on their mobile devices and in-store for information about special offers (Rapp et al., Citation2015), or search for information online and buy in-store (Verhoef et al., Citation2015). Thus, a satisfactory (e.g., seamless) omni-channel shopping experience is of great importance to shoppers (Mosquera et al., Citation2017) and essential in ensuring that they continue to use omni-channel shopping, resulting in loyalty (Lemon & Verhoef, Citation2016).

Prior research indicates that a superior experience develops and maintains successful customer–brand relationships (Lemke et al., Citation2011) and that the integration of various channels (e.g., seamlessness) is a key driver of satisfaction during their omni-channel experience (Sousa & Voss, Citation2006; Hamouda, Citation2019) and seamlessness affect attitude positively (Gao & Huang, Citation2023). A seamless experience increases brand awareness and customer satisfaction, which may lead increased sales (Asmare & Zewdie, Citation2022; Belvedere et al., Citation2021). Moreover, satisfaction (O) mediates the relationship between the stimulus (seamlessness) and the consumer response outcomes (R) (Chang & Li, Citation2022). Based on this discussion, we hypothesise that:

H1: Perceived seamlessness directly and positively influences omni-channel shoppers’ satisfaction.

Information visibility (stimulus)

Synchronisation, visibility, and integration are key to omni-channel success (Cai & Lo, Citation2020). Both synchronisation and integration are reflected in seamlessness in our study, while visibility and integration are reflected in the construct information visibility. Given the upsurge of digital technologies, new devices, and channels, customers and retailers can interact through countless touchpoints (Grewal et al., Citation2016). So, it is imperative that not only the same information is shared (Mirzabeiki & Saghiri, Citation2020) but also that the information is visible to shoppers in all channels. Given that omni-channel retailing aims to provide visibility across all platforms (Bell et al., Citation2015), integrated information visibility is an important stimulus in the omni-channel shopping journey. Brands need to prioritize products availability and accurate representation to ensure retention and loyalty with omnichannel shoppers (Anon, Citation2024).

Information visibility thus includes the extent to which product and brand information (e.g., product inventory) is visible and accessible across various channels. It highlights the importance of access to information and its visibility to ensure an integrated omni-channel experience (Saghiri et al., Citation2017; Wu & Chang, Citation2016). The study of Huré et al. (Citation2017) revealed visibility to be one of the prominent enablers of providing value during the omni-channel shopping experience. Information integration directly impacts satisfaction in the omni-channel journey (Gao & Yang, Citation2016); similarly, Lee (Citation2020) observed that omni-channel characteristics (e.g., information visibility) affect customer satisfaction. In addition, the consistency of the information provided across channels increases customers’ satisfaction (Ghotbabadi et al., Citation2016). As a result, we argue that:

H2: Information visibility directly and positively influences omni-channel shoppers’ satisfaction.

Journey satisfaction (organism)

The aim of omni-channelling is to offer customers flexibility in shopping to foster satisfaction (Zumstein et al., Citation2022). Omni-channel journey satisfaction measures shoppers’ processing of the stimuli (e.g., seamless experience, information visibility) that are present during the shopping journey, resulting in a complete emotional assessment of the journey (Herhausen et al., Citation2019). Satisfaction has been cited in several studies for its impact on consumer responses such as purchase intention (Lee, Citation2020) and customers’ recommendation or advocacy behaviour. Omni-channelling creates a sense of continuity that consumers value highly, resulting in satisfaction, loyalty behaviours, and the sharing of shopping experiences (Barbosa & Casais, Citation2022; Quach et al., Citation2020).

Continued shopping intention (response)

The numerous touchpoints in the omni-channel shopping experience present shoppers with many alternatives when designing their own shopping journey. They also give retailers ample opportunities to lose their customers to rivals along the journey. Consequently, it is important to ensure a shopping experience that leads to sales and enhances loyalty (Homburg et al., Citation2017). In the context of this study loyalty is defined similarly to Herhausen et al. (Citation2019), as a shopper’s intention to re-engage in omni-channel shopping. Satisfaction enhances purchase intention (Lee, Citation2020); and customers’ continued shopping intention is especially viewed as a pertinent relational outcome of an enhanced customer experience (e.g., satisfaction) (Lemke et al., Citation2011). Moreover, satisfaction has been found to play a positive role in continued purchase intent in livestream shopping (Chen, Citation2019) and in online shopping (Pebriani et al., Citation2018). Therefore,

H3: Shopper journey satisfaction directly and positively influences shoppers’ continued shopping intentions.

Customer influence behaviour (response)

Sharing is an essential part of any shopping experience, it is much more than general word-of-mouth, as shoppers are actively and strategically choosing to influence the perceptions, choices, and behaviours of other shoppers (Lee et al., Citation2018). Customer influence behaviour implies that customers share opinions, comments, and reviews about a retailer on social media (Kumar & Pansari, Citation2016). Customer influence is thus a type of engagement behaviour about a brand or retailer’s omni-channel offering (Kumar & Nayak, Citation2019)), such as providing brand reviews or product ratings. As omni-channel shoppers use social media extensively during their shopping journey (Shukla, Citation2021), comments about a specific brand can reach a large audience (Hogan & Quan-Haase, Citation2010). Customer influence behaviour is thus a critical outcome of satisfaction, and helps to reinforce customer–brand relationships in the omni-channel (Kumar & Nayak, Citation2019). In addition, Quach et al. (Citation2020) claim that the omni-channel experience motivates shoppers to undertake recommendation behaviours, while Kumar & Nayak, Citation2019)argue that satisfaction leads to customer engagement behaviours while a seamless satisfying omni-channel experience positively affects sWOM (Li & Chang, Citation2023). Therefore, and in line with the S-O-R framework, we propose that:

H4: Shopper journey satisfaction directly and positively impacts customer influence behaviours.

Shopping experience sharing (response)

Often research focuses on shoppers’ consumption-experience sharing (for example, sharing about product or service use) rather than on their shopping-experience sharing (Michaud-Trevinal & Stenger, Citation2014). The latter is even more important in an omni-channel shopping journey, as omni-channel shoppers are concerned about the collective experience across various channels throughout the entire shopping journey from need awareness, purchase, use and beyond (Zhang et al., Citation2024). Sharing experiences with other shoppers not only validates shoppers’ own experiences but also makes them more confident to share (Chen et al., Citation2018).

Generally, if shoppers have a satisfactory shopping experience, they are more likely to share the experience (Constant et al., Citation1994; Leppäniemi et al., Citation2017). A positive shopping experience thus motivates shoppers to recommend and share this experience with other customers (Gao & Su, Citation2017; Kalyanam et al., Citation2018). Given the S-O-R framework, and the fact that shopper satisfaction is considered an antecedent of recommendation intention (Leppäniemi et al., Citation2017), we hypothesise:

H5: Shopper journey satisfaction directly and positively influences shoppers’ experience sharing.

Convenience of sharing information, and its mediating role in the relationship between journey satisfaction and experience sharing

Convenience is a significant aspect of consumers’ online experience (Duarte et al., Citation2018), and the convenience of sharing information is a very important dimension in the omni-channel shopping journey (Cai & Lo, Citation2020). The rise of information and new technologies, particularly social media platforms, has greatly facilitated the convenience of sharing information. The convenience of sharing information in an omni-channel context relates to the degree to which shoppers can share effortlessly when moving between different channels (Lee et al., Citation2018; Chang & Li, Citation2022). This is reminiscent of perceived ease of use (PEU) in the technology acceptance model (TAM) and perceived behavioural control in the theory of planned behaviour (TPB). Perceived ease of use denotes a consumer’s belief that using a specific technology or process is effortless (Davis, Citation1989) – for example, that it is convenient to use; while perceived behaviour control refers to a consumer’s perception of the ease (i.e., convenience) or difficulty carrying out a specific behaviour is (Ajzen Citation1988; Bandura, Citation1986). Both operate on the premise that, if a behaviour is easy to perform, it is more likely that the behaviour will indeed occur.

Satisfied shoppers are more likely to find it convenient and worthwhile to share information about their purchases with others. They perceive value in their shopping experiences, and are more likely to believe that the information they share will be valuable to others. Satisfied shoppers may thus find it convenient to post on social media or provide feedback quickly because it is perceived as a simple and efficient process. Therefore:

H6: Journey satisfaction directly and positively influences the convenience of sharing information.

H7: Convenience of information sharing directly and positively influences shoppers’ experience-sharing behaviour.

H8: Information sharing mediates the relationship between journey satisfaction and shoppers’ experience-sharing behaviour.

Moderating role of social media platform attractiveness

Site attractiveness is the result of matching consumers’ needs with the design features of a platform or website (Sutcliffe, Citation2002), while Wirtz et al. (Citation2013) define it as the perceived preference to use certain social media pages or sites. Others such as Park and Kim (Citation2016) use a different approach: they do not theorise about the attractiveness, but rather concentrate on consumers’ perceptions of the attractiveness of the alternatives.

Considering these definitions, we investigate shoppers’ perceptions of how attractive it is for them to engage with a brand and with other shoppers on a brand’s social media platforms. Under the construct of attractiveness, we also subsume the degree to which shoppers perceive the brand’s social media page as more attractive than those of other brands/retailers. Given that omni-channel shopping is an integrated experience in which various stimuli are continually at play – and not necessarily in a linear fashion, as with traditional online or offline shopping – we propose that a stimulus may well have more than just a direct effect on the organism (satisfaction): it may also indirectly affect the relationship between an organism (satisfaction) and response (experience sharing), as the omni-channel shopping journey overlaps with the social media sharing journey.

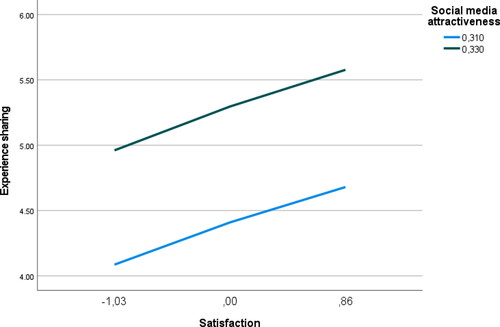

Site attractiveness also positively affects advocacy behaviours (Wirtz et al., Citation2020), while research shows that social media platform attractiveness, for example, mediates the relationship between gratification (e.g., satisfaction) and engagement behaviour (e.g., posting reviews or sharing experiences) (Chuah et al., Citation2020). Consumers tend to respond more favourably to an attractive site, and are also more committed to it (King & Youngblood, Citation2016). When a brand’s social media pages are seen as attractive, customers’ engagement increases (Chuah et al., Citation2020); and satisfied customers become more engaged when they express their feelings by sharing content and generating positive comments (Sashi, Citation2012). Previous studies have also reported the negative effect of the attractiveness of alternatives on customers’ satisfaction and loyalty behaviours and on the causal relationship between them (Chuah et al., Citation2017; Yim et al., Citation2007). Alternative attractiveness as moderator in the satisfaction-loyalty relationship has also been established (Wu, Citation2011).

Given social media’s central role in facilitating experience sharing (Arica et al., Citation2022; Mondahl & Razmerita, Citation2014), one could expect that a more attractive social media platform would increase the likelihood and frequency of experience sharing among satisfied shoppers. Therefore:

H9: Social media platform attractiveness moderates the relationship between journey satisfaction and experience sharing.

Methodology

Sample and data collection

South Africa is an ideal developing country to use for data collection, as recent growth in e-commerce has highlighted untapped opportunities for omni-channel retailing in the country (E-commerce Citation2022). Convenience sampling (non-probability) was employed to collect data from adult (18 years and older) omni-channel shoppers (no particular age group was targeted) via an online self-completion Qualtrics survey, resulting in 433 responses. Approval for the project was obtained from the researchers’ home faculty (protocol number: EMS135/22) before data collection began, and informed consent was then obtained from the respondents. A pilot study among 50 omni-channel shoppers revealed no major problems.

Questionnaire and measures

The questionnaire consisted of screening questions (e.g., confirming omni-channel shoppers and social media users), scale questions to measure the suggested constructs, and demographics (e.g., gender, education). Constructs were measured with seven-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 (Strongly agree), except for the construct of experience sharing, where the scale reflected frequency, ranging from 1 (Never) to 7 (Always). The following three-item scales were used: perceived seamlessness (Huré et al., Citation2017); information visibility and convenience of sharing (Chang & Li, Citation2022); and experience sharing (Chen et al., Citation2018; Akareem et al., Citation2022). Customer influences (Kumar & Pansari, Citation2016), continued shopping intention (Bhattacherjee, Citation2001), satisfaction (Oliver, Citation1980), and social media attractiveness (Wirtz et al., Citation2020) were all four-item scales.

Data analyses

The data were analysed descriptively with SPSS (version 28), after which the model was tested using covariance-based structural equation modelling (SEM) in Amos version 28. CB-SEM (AMOS) was used as it is a better technique for theory-driven research, hypotheses testing, normally distributed data, reflective latent variables, obtaining the highest accuracy numerical models and statistically significant results – all aspects applicable to our research and given that we did not have a small sample or an extensive number of items per construct that is some of the reasons for using SMART PLS, CB-SEM was deemed appropriate (Afthanorhan et al., Citation2020). After running the measurement model, reliability and validity were assessed. The latter aspects were assessed as follows (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Henseler et al., Citation2015; Hair et al., Citation2014): convergent validity via Cronbach’s alpha (α) and composite reliability (CR) (both must exceed 0.7), and average variance extracted (AVE) greater than 0.5. Discriminant validity was explored to determine whether the correlations between constructs were less than the square root of the AVE. SEM was conducted once reliability and validity had been confirmed. Model fit was evaluated using a combination of incremental and absolute fit indices (Hair et al., Citation2014; Van de Schoot et al., Citation2012), namely RMSEA < 0.08 CFI and TLI > 0.9; and CMIN/DF < 3.

Results

Demographic profile

A total of 433 responses were obtained; the average age of the respondents was 33 years, indicative of a more youthful sample with 38% being classified as Gen Z (18-27 years), 46% as Millennials (28-43 years); 14% as Gen X (44-59 years), and 2% as Boomers (60+ years). The sample was skewed towards males (61%), and 73% of the respondents had some sort of post-school qualification (e.g., a diploma or a degree). Shopping has been strongly associated with females (Sohail, Citation2015), and the typical offline shopper in South Africa is often female (City Press, Citation2022); however, a different trend is emerging in online shopping. The archetypal online shopper is predominantly male, with men tending to perform more product searches online than women and comparing products on social networks more often before purchasing (Solutionists, Citation2021).

Measurement model

The CFA showed acceptable model fit: RMSEA = 0.043; CFI = 0.976; TLI = 0.970; CMIN/DF = 1.788. Convergent validity was established, as all of the Cronbach’s α, CR, and AVE values exceeded the recommended cut-offs (). Caution should be taken with high Cronbach alpha values to avoid indicator redundancy, which would compromise content validity but as evident in , continued intention (0.933) and satisfaction (0.932)’s values are below the acceptable maximum of 0.95 (Hair et al., Citation2019). Information visibility’s AVE was slightly below the 0.5 cut-off; but given the acceptable CR and Cronbach’s α values of 0.7, the convergent validity of the construct was adequate (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Nunnally, Citation1978).

Table 1. Means, reliability, and validity.

Discriminant validity was investigated in using the criterion of Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981), in which the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) should be greater than all the correlations between each pair of constructs. As the rule-of-thumb criteria of Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) do not consider sampling errors, constructs that showed weak discriminant validity, were hence subjected to further scrutiny by investigating the Heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT). The acceptable levels of discriminant validity (< 0.90) were evident in all three instances (Info visibility and satisfaction: HTMT = 0.681; Info visibility and continued shopping intention: HTMT = 0.683; info visibility and convenience of sharing = 0.691) (Henseler et al., Citation2015). Consequently, confirming discriminant validity for all constructs.

Table 2. Discriminant validity of constructs (AVE correlations).

Structural model and hypotheses testing

The structural model showed acceptable fit: RMSEA = 0.065, [LO90 = 0.059; HI90 = 0.071]); CFI = 0.939; TLI = 0.931, and the normed chi-square (CMIN/DF = 2842) was below 3. The results indicated that all seven relational hypotheses were supported. Both perceived seamlessness (p < 0.001; Beta = 0.245) and information visibility (p < 0.001; Beta = 0.563) significantly and positively predicted satisfaction, thus supporting H1 and H2. Similarly, H3, H4, H5, and H6 were supported, as satisfaction significantly and positively predicted continued shopping intention (p < 0.001; Beta = 0.889), customer influence (p < 0.001; Beta = 0.298), experience sharing (p < 0.001; Beta = 0.259), and convenience of sharing (p < 0.001; Beta = 0.534). In addition, convenience of sharing (p < 0.001; Beta = 0.234) significantly and positively predicted experience sharing, thus supporting H7. It is evident that the strongest predictor of satisfaction was information visibility and that the strongest relational outcome was continued shopping intention.

A bootstrap test of the indirect effect was conducted (Zhao et al., Citation2010) to test for mediation. A statistically significant indirect effect (indirect effect = 0.125; CI = 0.038–0.0.213; p = 0.009) for convenience of sharing, hypothesised as a mediator in the relationship between satisfaction and experience sharing, was found. The results showed that convenience of sharing partially mediated the relationship between satisfaction and experience sharing, as the direct effect was statistically significant (direct effect = 0.259; CI= 0.087–0.421; p = 0.013), thus supporting H8.

Moderation was tested using a multi-group CFA approach. The results showed that social media attractiveness (SMA) moderated the relationship between satisfaction and experience sharing, thus supporting H9, as the difference between the constrained and unconstrained models for both high and low social media attractiveness (chi-square differences: low SMA = 81.7; high SMA = 36.6) exceeded 3.84 (Awang, Citation2014). An investigation of the slopes (low SMA = 0.310; high SMA = 0.330), as shown in , suggested a difference in the rate of increase for low and high SMA, thereby indicating a slightly stronger positive relationship in the higher values of SMA.

Conclusions and implications

Consumers are increasingly using a variety of channels in their shopping journeys. As a result, retailers must provide shoppers with an integrated omni-channel experience, allowing them to shop effortlessly across channels (Cattapan & Pongsakornrungsilp, Citation2022). The findings of this study enhance retailers’ insights into the drivers of shoppers’ omni-channel experience and customer response outcomes.

Given the effort and resources needed for channel integration, retailers often wonder if it indeed pays off (Herhausen et al., Citation2015). Our study offers important empirical evidence about shoppers’ positive responses because of channel integration (seamless experience and information visibility) and provides retailers with more confidence to implement channel integration to reap the benefits, such as continued shopping intentions and information- and experience-sharing behaviour from satisfied shoppers.

The results have not only verified an expanded S-O-R framework in considering the mediating effect of conveniently sharing information and the moderating effect of social media platform attractiveness but have also confirmed the suitability of the framework in an omni-channel developing market.

Our results also confirm that a seamless experience is a driver of satisfaction, as proposed by Hamouda (Citation2019). However, it seems that a seamless experience may not be the most important aspect for retailers to consider to ensure that shoppers are satisfied. The role of information visibility – even more than that of a seamless experience – as a major driver in ensuring a satisfactory customer shopping experience is underscored by the findings, and is in line with research that highlights visibility and integration as important constructs in omni-channelling (Melacini et al., Citation2018). In a way similar to livestream shopping (Chen, Citation2019), the results confirm that shopper satisfaction results in the continued intention to use omni-channel shopping. Our results concur with those of previous findings, that customers’ influencing behaviour is indeed an important outcome of satisfaction (Kumar & Nayak, Citation2019)), in addition to influencing omni-channels shopping intent (Sugiat et al., Citation2023).

The findings confirm that shoppers’ experience could also be related to brand-related information sharing (Gvili & Levy, Citation2021) and to the mediating role of perceived behaviour control in sharing behaviour relationships, as suggested by Hau and Kang (Citation2016). The convenience of sharing acting as a mediator explains how journey satisfaction translates into experience-sharing behaviour. When a brand’s social media pages are deemed attractive by customers, their customer engagement increases (Chuah et al., Citation2020). This is true in an omni-channel context, given that social media platform attractiveness moderates the relationship between journey satisfaction and the experience-sharing behaviour of shoppers.

Practical implications

From a managerial perspective, the results have several implications for practitioners. Retailers, especially those in a developing market, need to embrace omni-channel retailing as shoppers that are connected and integrated with their brands, is the key to survival and growth (Joshi et al., Citation2022). A seamless experience is almost expected by shoppers, and even more so is having information available at their fingertips throughout the experience. Viewing a brand’s products and related information, checking product inventory status, and keeping track of a transaction through different channels play a more important role in ensuring satisfaction than seamlessly moving from one channel to another. This signals that shoppers expect more from retailers during their omni-channel shopping journey than merely a seamless experience. Metaverse technologies combine the virtual and physical realms, permitting shoppers to interact with products and brands in immersive virtual environments, contributing to a unified experience while AI can help to streamline shoppers’ experience and enhance cross-channel communication. For example, uniform branding and promotions throughout the various channels, and ensuring that online platforms are optimised on mobile devices, could enhance seamlessness, while AI chatbots can be used to ensure consistent and accurate information across channels.

Additional features such as ‘click-and-collect’ or ‘ship-to-store’ buttons with the option to collect or return via a retailer’s physical store or online could further enhance the ease of moving between the channels. Real-time inventory management systems are essential to ensure consistent information. Information about product availability and transaction history should also be a ‘click’ away online with easy-to-navigate instructions. Retailers can use Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) that allows tracking and identification of products. By tagging products with RFID chips, brands gain real-time insights into inventory levels, ensuring that products are available and accurately represented across various channels, reducing out-of-stock situations, thereby enhancing customer satisfaction.

Satisfaction results in the continued intention to use omni-channel shopping. This could be further enhanced by using cross-channel promotions and reward campaigns – for example, a discount on future purchases to use online or to redeem in-store. Personalised messages leveraging customer data and aligning with shoppers’ past channel preferences (e.g., machine learning) could also be beneficial. AI-powered sentiment analyses for example could provide valuable insights into how shoppers perceive a brand’s products and social media (positive or negative), enabling brands to proactively respond, resulting in improved satisfaction.

Retailers should capitalise on customers sharing their opinions and comments about the brand on social media, especially as one could assume that satisfied shoppers will make positive comments about the retailer. Encouraging this type of engagement behaviour is not only more credible than information from the brand but also a ‘free’ form of advertising. Potential customers may be more receptive to information from existing customers than to the same communication from a brand. Brands could consider social sharing incentives (e.g., discounts or exclusive offers), customer referral programmes, and encouraging satisfied shoppers to tag their sites and use branded hashtags.

Given that omni-channel shoppers are more social (Lemon & Verhoef, Citation2016), encouraging social sharing is imperative. Satisfied shoppers may be more easily persuaded to share their experiences on social media, especially if it is easy and convenient to do so, which in turn may prompt potential new customers to take action (Herhausen et al., Citation2019). Brands should simplify sharing options by ensuring multiple easy-to-share options across channels – for example, by including social-sharing buttons in their apps or providing designated areas in-store for sharing, such as a selfie wall or a photo booth. Using personalised social sharing prompts, investing in technology to ensure a ‘one-click’ sharing option, and creating brand hashtags could ensure a convenient way to share – and encourage experience-sharing behaviour. In addition, providing virtual try-ons for example not only helps shoppers to visualise how products look in their environment but allows for engaging and sharable experiences.

Consequently, brands and retailers have two ways to enhance sharing behaviour: convenience and social media platform attractiveness. Brands thus need to ensure that their social media pages are not only more attractive than those of other brands, but that they also appeal to shoppers to interact, connect, and set up networks with the brand and other users of the brand’s or retailer’s social media pages. Consistent branding, exclusive offers and deals, engaging content, collaborations with influencers, and interactive features are just some of the strategies that brands could use to improve their social media platform attractiveness, in addition to ensuring a convenient sharing experience. By leveraging AI-tools retailers can for example identify influences who align with their target shoppers and brand values.

Theoretical contributions

This study makes several theoretical contributions. First, insights into shoppers’ responses in an omni-channel context is offered. Consumer response is used to evaluate the effectiveness and importance of strategic decisions. Our theory-driven research found empirical evidence confirming relationships between seamless experience and information visibility (channel integration), shopper satisfaction, and continued shopping intention and experience and information sharing. The findings highlight the critical role of channel integration in producing positive consumer outcomes – but even more, the vital role of information visibility to drive satisfaction. Merely providing a seamless experience will not be enough in the future to ensure satisfied omni-channel shoppers. While research typically focuses on consumption sharing behaviour, this study has adopted a dual sharing perspective by investigating not only customer influence as a type of consumption behaviour sharing, but also experience-sharing behaviour, which is important for customer engagement theory.

Second, it contributes to our knowledge of an innovative and fast-growing trend that is still under-researched, especially from a consumer perspective. So, it not only contributes to the consumer behaviour and retail literature but also provides practical insights for retailers to capitalise on this new retail channel.

Third, this study extends the application of the SOR framework to omni-channel retailing and, more specifically, to developing markets that will see exponential growth in omni-channel retailing, but that are still relatively under-researched (Joshi et al., Citation2022; Asmare & Zewdie, Citation2022).

Limitations and directions for future research

Despite this study’s significant contributions, it has some limitations. Convenience sampling was used, and this might affect the ability to generalise the findings. However, it should be noted that, despite the sample’s contextual delimitations (i.e., South Africa), the concepts and relationships were founded in theory and the literature. Future studies could investigate other developing contexts or conduct cross-country studies as well as consider the geographical location of shoppers (rural vs. urban for example). As omni-channel retailing gains momentum, especially in developing markets, the drivers of journey satisfaction may change: shoppers might expect a seamless experience, as was apparent in our study, and new and more powerful drivers might come into play. The importance of experience sharing for shoppers, for other customers, and for brands is undeniable, making it of utmost importance to gain a deeper understanding of omni-channel shoppers’ sharing behaviour, and to reveal the relational intricacies of this behaviour and of other possible constructs including the possible role of social-demographical factors. As this study explored the role of social media in omni-channeling, future research opportunities exist to examine the role of other technologies such as AI, machine learning, AR, metaverse, or RFID technology and consumers’ reactions to this new technology.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Melanie Wiese

Melanie Wiese has a PhD in Marketing and is a Professor in the field of Marketing Management (University of Pretoria, South Africa). Her research interests focus on consumer behavior and her research has appeared in a range of international journals including Journal of Consumer Marketing, Journal of Business Research and Journal of Marketing Management, among others.

References

- Adhi, P., Hazan, E., Kohli, S., & Robinson, K. (2021). “Omnichannel shopping in 2030. McKinsey insights”. Ahead-of-print. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/marketing-and-sales/our-insights/omnichannel-shopping-in-2030/ (Accessed February 14, 2024).

- Afthanorhan, A., Awang, Z., & Aimran, N. (2020). Five common mistakes for using partial least squares path modeling (PLS-PM) in management research. Contemporary Management Research, 16(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.7903/cmr.20247

- Ajzen, I. (1988). Attitudes, personality, and behavior. Dorsey Press.

- Akareem, H. S., Wiese, M., & Hammedi, W. (2022). Patients’ experience sharing with online social media communities: A bottom-of-the-pyramid perspective. Journal of Services Marketing, 36(2), 168–184. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-12-2020-0512

- Anon. (2024). Winning with the omnichannel shopper in the face of disruption. Available at: https://www.8451.com/omnichannel-white-paper-2023/ (Accessed February 16, 2024)

- Arica, R., Cobanoglu, C., Cakir, O., Corbaci, A., Hsu, M.-J., & Della Corte, V. (2022). Travel experience sharing on social media: Effects of the importance attached to content sharing and what factors inhibit and facilitate it. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(4), 1566–1586. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-01-2021-0046

- Asmare, A., & Zewdie, S. (2022). Omnichannel retailing strategy: A systematic review. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 32(1), 59–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2021.2024447

- Awang, Z. (2014). Analyzing the effect of a moderator in a model: The multi-group CFA procedure in SEM. Proceedings of the Academic Colloquium for Academicians & Postgraduates, Kuala Terengganu, Malaysia, November, 128–154.

- Bagozzi, R. P. (1986). Attitude formation under the theory of reasoned action and a purposeful behaviour reformulation. British Journal of Social Psychology, 25(2), 95–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.1986.tb00708.x

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

- Barbosa, J., & Casais, B. (2022). The transformative and evolutionary approach of omnichannel in retail companies: Insights from multi-case studies in Portugal. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 50(7), 799–815. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-12-2020-0498

- Baxendale, S., MacDonald, E. K., & Wilson, H. N. (2015). The impact of different touchpoints on brand consideration. Journal of Retailing, 91(2), 235–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2014.12.008

- Bell, D., Gallino, S., & Moreno, A. (2015). Showrooms and information provision in omni-channel retail. Production and Operations Management, 24(3), 360–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.12258_2

- Belvedere, V., Martinelli, E. M., & Tunisini, A. (2021). Getting the most from E-commerce in the context of omnichannel strategies. Italian Journal of Marketing, 2021(4), 331–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43039-021-00037-6

- Bijmolt, T. H., Broekhuis, M., de Leeuw, S., Hirche, C., Rooderkerk, R. P., Sousa, R., & Zhu, S. X. (2021). Challenges at the marketing–operations interface in omni-channel retail environments. Journal of Business Research, 122, 864–874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.034

- Bhattacherjee, A. (2001). Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. MIS Quarterly, 25(3), 351–370. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250921

- Cai, Y.-J., & Lo, C. K. Y. (2020). Omni-channel management in the new retailing era: A systematic review and future research agenda. International Journal of Production Economics, 229, 107729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2020.107729

- Cattapan, T., & Pongsakornrungsilp, S. (2022). Impact of omnichannel integration on Millennials’ purchase intention for fashion retailer. Cogent Business and Management, 9(1), 2087460. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2087460

- Chang, Y. P., & Li, J. (2022). Seamless experience in the context of omnichannel shopping: scale development and empirical validation. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 64, 102800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102800

- Chen, L. Y. (2019). The effects of livestream shopping on customer satisfaction and continuous purchase intention. International Journal of Advanced Studies in Computers, Science and Engineering, 8(4), 1–9.

- Chen, T., Drennan, J., Andrews, L., & Hollebeek, L. D. (2018). User experience sharing: Understanding customer initiation of value co-creation in online communities. European Journal of Marketing, 52(5/6), 1154–1184. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-05-2016-0298

- Chen, Y., & Chi, T. (2021). How does channel integration affect consumers’ selection of omni-channel shopping methods? An empirical study of US consumers. Sustainability, 13(16), 8983. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168983

- Cho, W.-C., Lee, K. Y., & Yang, S.-B. (2019). What makes you feel attached to smartwatches? The stimulus–organism–response (S–O–R) perspectives. Information Technology & People, 32(2), 319–343. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-05-2017-0152

- Chu, S.-C., Chen, H.-T., & Sung, Y. (2016). Following brands on Twitter: An extension of theory of planned behavior. International Journal of Advertising, 35(3), 421–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2015.1037708

- Chuah, S. H.-W., Aw, E. C.-X., & Tseng, M.-L. (2020). The missing link in the promotion of customer engagement: The roles of brand fan page attractiveness and agility. Internet Research, 31(2), 587–612. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-01-2020-0025

- Chuah, S. H.-W., Marimuthu, M., Kandampully, J., & Bilgihan, A. (2017). What drives Gen Y loyalty? Understanding the mediated moderating roles of switching costs and alternative attractiveness in the value-satisfaction-loyalty chain. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 36, 124–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.01.010

- Chung, N., Han, H., & Joun, Y. (2015). Tourists’ intention to visit a destination: The role of augmented reality (AR) application for a heritage site. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 588–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.02.068

- City Press. (2022). “Are women better shoppers than men? Well, maybe – study shows.” City Press. Available at: https://www.news24.com/citypress/news/are-women-better-shoppers-than-men-well-maybe-study-shows-20220826 (Accessed October 16, 2023).

- Constant, D., Kiesler, S., & Sproull, L. (1994). What’s mine is ours, or is it? A study of attitudes about information sharing. Information Systems Research, 5(4), 400–421. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.5.4.400

- Court, D., Elzinga, D., Mulder, S., & Vetvik, O. J. (2009). The consumer decision journey. McKinsey Quarterly, 3(3), 1–11.

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

- De Keyser, A., Verleye, K., Lemon, K. N., Keiningham, T. L., & Klaus, P. (2020). Moving the customer experience field forward: Introducing the touchpoints, context, qualities (TCQ) nomenclature. Journal of Service Research, 23(4), 433–455. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520928390

- De Oliveira, S., Ladeira, F. W., Pinto, D. C., Herter, M. M., Sampaio, C. H., & Babin, B. J. (2020). Customer engagement in social media: A framework and meta-analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(6), 1211–1228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-020-00731-5

- Duarte, P., Costa e Silva, S., & Ferreira, M. B. (2018). How convenient is it? Delivering online shopping convenience to enhance customer satisfaction and encourage e-WOM. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 44, 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.06.007

- Ecommerce. Ecommerce. (2022). “10 trends and projections for online shopping in SA.” Available at: https://www.ecommerce.co.za/infocentrearticle.aspx?s=165&c=629&a=7570&p=41&title=Landscape#title (Accessed October 16, 2022).

- Edelman, D. C., & Singer, M. (2015). Competing on customer journeys. Harvard Business Review, 93(11), 88–100.

- Euromonitor. (2022). “Voice of the industry: digital survey”. Accessed February 16, 2024. available at: https://www.euromonitor.com/voice-of-the-industry-digital-survey/report

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2010). Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. Psychology Press.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Gao, M., & Huang, L. (2023). The mediating role of perceived enjoyment and attitude consistency in omni-channel retailing. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 36(3), 599–621. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-01-2023-0079

- Gao, R., & Yang, Y.-X. (2016). Consumers’ decision: Fashion omni-channel retailing. Journal of Information Hiding and Multimedia Signal Processing, 7(2), 325–342.

- Gao, F., & Su, X. (2017). Omnichannel retail operations with buy-online-and-pick-up-in-store. Management Science, 63(8), 2478–2492. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2016.2473

- Gasparin, I., Panina, E., Becker, L., Yrjölä, M., Jaakkola, E., & Pizzutti, C. (2022). “Challenging the “integration imperative”: A customer perspective on omnichannel journeys. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 64, 102829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102829

- Gerea, C., Gonzalez-Lopez, F., & Herskovic, V. (2021). Omnichannel customer experience and management: an integrative review and research agenda. Sustainability, 13(5), 2824. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052824

- Ghotbabadi, A. R., Feiz, S., & Baharun, R. (2016). The relationship of customer perceived risk and customer satisfaction. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 7(1), 161. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2016.v7n1s1p161

- Goyal, S., Hu, C., Chauhan, S., Gupta, P., Bhardwaj, A. K., & Mahindroo, A. (2021). Social commerce: A bibliometric analysis and future research directions. Journal of Global Information Management, 29(6), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.4018/JGIM.293291

- Grewal, D., Roggeveen, A. L., & Nordfält, J. (2016). Roles of retailer tactics and customer-specific factors in shopper marketing: Substantive, methodological, and conceptual issues. Journal of Business Research, 69(3), 1009–1013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.08.012

- Gvili, Y., & Levy, S. (2021). Consumer engagement in sharing brand-related information on social commerce: The roles of culture and experience. Journal of Marketing Communications, 27(1), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2019.1633552

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., & Babin, B. J. (2014). Multivariate data analysis. Pearson Education Limited.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hamouda, M. (2019). Omni-channel banking integration quality and perceived value as drivers of consumers’ satisfaction and loyalty. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 32(4), 608–625. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-12-2018-0279

- Hau, Y. S., & Kang, M. (2016). Extending lead user theory to users’ innovation-related knowledge sharing in the online user community: The mediating roles of social capital and perceived behavioral control. International Journal of Information Management, 36(4), 520–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2016.02.008

- Hau, Y.-S., & Kim, Y.-G. (2011). Why would online gamers share their innovation-conducive knowledge in the online game user community? Integrating individual motivations and social capital perspectives. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(2), 956–970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.11.022

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Herhausen, D., Jochen Binder, J., Schoegel, M., & Herrmann, A. (2015). Integrating bricks with clicks: Retailer-level and channel-level outcomes of online–offline channel integration. Journal of Retailing, 91(2), 309–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2014.12.009

- Herhausen, D., Kleinlercher, K., Verhoef, P. C., Emrich, O., & Rudolph, T. (2019). Loyalty formation for different customer journey segments. Journal of Retailing, 95(3), 9–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2019.05.001

- Hickman, E., Kharouf, H., & Sekhon, H. (2020). An omnichannel approach to retailing: Demystifying and identifying the factors influencing an omnichannel experience. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 30(3), 266–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2019.1694562

- Hogan, B., & Quan-Haase, A. (2010). Persistence and change in social media. Bulletin of Science, Technology and Society, 30(5), 309–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467610380012

- Homburg, C., Jozić, D., & Kuehnl, C. (2017). Customer experience management: Toward implementing an evolving marketing concept. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(3), 377–401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-015-0460-7

- Hossain, T. M., Akter, T. S., Kattiyapornpong, U., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2019). Multichannel integration quality: A systematic review and agenda for future research. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 49, 154–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.03.019

- Huré, E., Picot-Coupey, K., & Ackermann, C.-L. (2017). Understanding omni-channel shopping value: A mixed-method study. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 39(6), 314–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.08.011

- İzmirli, D., Ekren, B. Y., Kumar, V., & Pongsakornrungsilp, S. (2021). Omni-channel network design towards circular economy under inventory share policies. Sustainability, 13(5), 2875. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052875

- Joshi, S., Sharma, M., & Chatterjee, P. (2022). Omni-channel retailing enhancing unified experience amidst pandemic: An emerging market perspective. Decision Making: Applications in Management and Engineering, 6(1), 449–473.

- Kalyanam, K., McAteer, J., Marek, J., Hodges, J., & Lin, L. (2018). Cross channel effects of search engine advertising on brick-and-mortar retail sales: Meta analysis of large-scale field experiments on Google.com. Quantitative Marketing and Economics, 16(1), 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11129-017-9188-7

- Kaur, V., Khullar, V., & Verma, N. (2020). Review of artificial intelligence with retailing sector. Journal of Computer Science Research, 2(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.30564/jcsr.v2i1.1591

- King, B. A., & Youngblood, N. E. (2016). E-government in Alabama: An analysis of county voting and election website content, usability, accessibility, and mobile readiness. Government Information Quarterly, 33(4), 715–726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2016.09.001

- Kühn, S. W., & Petzer, D. J. (2018). Fostering purchase intentions toward online retailer websites in an emerging market: An SOR perspective. Journal of Internet Commerce, 17(3), 255–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332861.2018.1463799

- Kumar, V., & Pansari, A. (2016). Competitive advantage through engagement. Journal of Marketing Research, 53(4), 497–514. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.15.0044

- Kumar, J., & Nayak, J. K. (2019). Consumer psychological motivations to customer brand engagement: A case of brand community. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 36(1), 168–177. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-01-2018-2519

- Kumar, S., Jain, A., & Hsieh, J.-K. (2021). Impact of apps aesthetics on revisit intentions of food delivery apps: The mediating role of pleasure and arousal. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 63, 102686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102686

- Pillai, R., Sivathanu, B., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2020). Shopping intention at AI-powered automated retail stores (AIPARS). Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 57(1), 102207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102207

- Lee, L., Inman, J. J., Argo, J. J., Böttger, T., Dholakia, U., Gilbride, T., van Ittersum, K., Kahn, B., Kalra, A., Lehmann, D. R., McAlister, L. M., Shankar, V., & Tsai, C. I. (2018). From browsing to buying and beyond: The needs-adaptive shopper journey model. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 3(3), 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1086/698414

- Lee, W.-J. (2020). Unravelling consumer responses to omni-channel approach. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 15(3), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-18762020000300104

- Lemke, F., Clark, M., & Wilson, H. (2011). Customer experience quality: An exploration in business and consumer contexts using repertory grid technique. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(6), 846–869. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-010-0219-0

- Lemon, K. N., & Verhoef, P. C. (2016). Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. Journal of Marketing, 80(6), 69–96. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.15.0420

- Leppäniemi, M., Karjaluoto, H., & Saarijärvi, H. (2017). Customer perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty: The role of willingness to share information. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 27(2), 164–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2016.1251482

- Li, J., & Chang, Y. (2023). The influence of seamless shopping experience on customers’ word of mouth on social media. Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-04-2023-0135

- Li, X., Zhou, Y., Wong, Y. D., Wang, X., & Yuen, K. F. (2021). What influences panic buying behaviour? A model based on dual-system theory and stimulus–organism–response framework. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 64, 102484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102484

- Lin, S.-W., Huang, E. Y., & Cheng, K.-T. (2023). A binding tie: why do customers stick to omnichannel retailers? Information Technology & People, 36(3), 1126–1159. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-01-2021-0063

- Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). An approach to environmental psychology. MIT Press.

- Melacini, M., Perotti, S., Rasini, M., & Tappia, E. (2018). E-fulfilment and distribution in omni-channel retailing: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 48(4), 391–414. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-02-2017-0101

- Michaud-Trevinal, A., & Stenger, T. (2014). Toward a conceptualization of the online shopping experience. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 21(3), 314–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2014.02.009

- Mirzabeiki, V., & Saghiri, S. S. (2020). From ambition to action: How to achieve integration in omni-channel? Journal of Business Research, 110, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.12.028

- Mondahl, M., & Razmerita, L. (2014). Social media, collaboration and social learning: A case-study of foreign language learning. Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 12(4), 339–352.

- Mosquera, A., Pascual, C. O., & Ayensa, E. J. (2017). Understanding the customer experience in the age of omni-channel shopping. Revista ICONO14 Revista Científica de Comunicación y Tecnologías Emergentes, 15(2), 92–114. https://doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v15i2.1070

- Nunnally, J. C. (1978). An overview of psychological measurement. In: Wolman, B.B. (Ed) Clinical Diagnosis of Mental Disorders. Springer.

- Oliver, R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17(4), 460–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378001700405

- Pantano, E., & Viassone, M. (2015). Engaging consumers on new integrated multichannel retail settings: Challenges for retailers. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 25, 106–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.04.003

- Park, J.-H., & Kim, M.-K. (2016). Factors influencing the low usage of smart TV services by the terminal buyers in Korea. Telematics and Informatics, 33(4), 1130–1140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2016.01.001

- Pebriani, W. V., Sumarwan, U., & Simanjuntak, M. (2018). The effect of lifestyle, perception, satisfaction, and preference on the online re-purchase intention. Independent Journal of Management & Production, 9(2), 545–561. https://doi.org/10.14807/ijmp.v9i2.690

- Quach, S., Barari, M., Moudrý, D. V., & Quach, K. (2020). Service integration in omnichannel retailing and its impact on customer experience. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 65, 102267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102267

- Rapp, A., Baker, T. L., Bachrach, D. G., Ogilvie, J., & Beitelspacher, L. S. (2015). Perceived customer showrooming behavior and the effect on retail salesperson self-efficacy and performance. Journal of Retailing, 91(2), 358–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2014.12.007

- Saghiri, S., Wilding, R., Mena, C., & Bourlakis, M. (2017). Toward a three-dimensional framework for omni-channel. Journal of Business Research, 77, 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.03.025

- Sashi, C. M. (2012). Customer engagement, buyer‐seller relationships, and social media. Management Decision, 50(2), 253–272. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251741211203551

- Shukla, M. (2021). What is omnichannel retail? A guide to the latest trends in omni-channel customer experience. Available at: https://delighted.com/blog/omnichannel-retail-consumer-trends. (Accessed February, 14, 2024).

- Sohail, M. S. (2015). Gender differences in mall shopping: A study of shopping behaviour of an emerging nation. Journal of Marketing and Consumer Behaviour in Emerging Markets, 1(1), 36–46.

- Solutionists. (2021). “Men vs women: online shopping behaviour. Who runs the online shopping world?” Solutionists. Available at: https://www.solutionists.co.nz/blog/ecommerce/men-vs-women-online-shopping-behaviour (Accessed January 21, 2023),

- Sousa, R., & Voss, C. A. (2006). Service quality in multichannel services employing virtual channels. Journal of Service Research, 8(4), 356–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670506286324

- Stephen, A. T., & Galak, J. (2012). The effects of traditional and social earned media on sales: A study of a microlending marketplace. Journal of Marketing Research, 49(5), 624–639. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.09.0401

- Sutcliffe, A. (2002). “Assessing the reliability of heuristic evaluation for web site attractiveness and usability.”. Proceedings of the 35th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Big Island, Hawaii, USA, January: 1838–1847. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2002.994098

- Sugiat, M., Saabira, N., & Witarsyah, D. (2023). Omni-Channel Service Analysis of Purchase Intention. International Journal on Informatics Visualization, 7(4), 2543–2549. https://doi.org/10.30630/joiv.7.4.02442

- Van de Schoot, R., Lugtig, P., & Hox, J. (2012). A checklist for testing measurement invariance. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9(4), 486–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2012.686740

- Verhoef, P. C., van Ittersum, K., Kannan, P. K., & Inman, J. (2022). Omnichannel retailing: A consumer perspective. In Lynn R. Kahle, Tina M. Lowrey, and Joel Huber,(Eds), APA handbook of consumer psychology. 649–672. American Psychological Association.

- Verhoef, P. C., Kannan, P. K., & Inman, J. (2015). From multi-channel retailing to omni-channel retailing: Introduction to the special issue on multi-channel retailing. Journal of Retailing, 91(2), 174–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2015.02.005

- Wirtz, B. W., Piehler, R., & Sebastian Ullrich, S. (2013). Determinants of social media website attractiveness. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 14(1), 11.

- Wirtz, B. W., Göttel, V., Langer, P. F., & Thomas, M.-J. (2020). Antecedents and consequences of public administration’s social media website attractiveness. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 86(1), 38–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852318762310

- Wu, J.-F., & Chang, Y. P. (2016). Multichannel integration quality, online perceived value and online purchase intention: A perspective of land-based retailers. Internet Research, 26(5), 1228–1248. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-04-2014-0111

- Wu, L.-W. (2011). Satisfaction, inertia, and customer loyalty in the varying levels of the zone of tolerance and alternative attractiveness. Journal of Services Marketing, 25(5), 310–322. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876041111149676

- Yim, C. K. B., Chan, K. W., & Hung, K. (2007). Multiple reference effects in service evaluations: Roles of alternative attractiveness and self-image congruity. Journal of Retailing, 83(1), 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2006.10.011

- Yen, Y.-S. (2023). Channel integration affects usage intention in food delivery platform services: the mediating effect of perceived value. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 35(1), 54–73. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-05-2021-0372

- Zhang, X., Park, Y., & Park, J. (2024). The effect of personal innovativeness on customer journey experience and reuse intention in omni-channel context. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 36(2), 480–495. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-12-2022-1013

- Zhang, M., Ren, C., Wang, G. A., & He, Z. (2018). The impact of channel integration on consumer responses in omni-channel retailing: The mediating effect of consumer empowerment. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 28, 181–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2018.02.002

- Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197–206. https://doi.org/10.1086/651257

- Zhu, L., Li, H., Wang, F.-K., He, W., & Tian, Z. (2020). How online reviews affect purchase intention: A new model based on the stimulus–organism–response (SOR) framework. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 72(4), 463–488. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-11-2019-0308

- Zumstein, D., Oswald, C., & Brauer, C. (2022). “Online retailer survey 2022: Success factors and omnichannel services in digital commerce.” Digital collection. https://digitalcollection.zhaw.ch/bitstream/11475/25919/3/2022_Zumstein-Oswald-Brauer_Online-Retailer-Survey.pdf (Accessed July 24, 2023).