Abstract

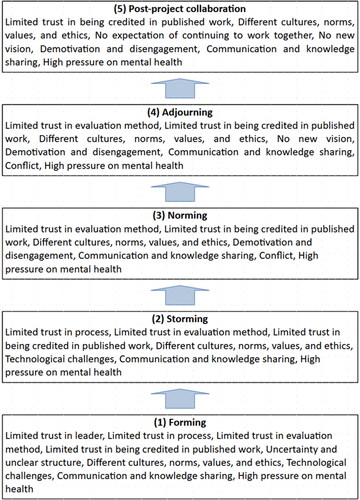

Despite the many benefits for researchers that participate in a project there are several challenges that create a cumulative, negative, effect on their mental health. Existing research focuses on four stages of a project: Forming, Storming, Norming and Adjourning. This research adds a fifth stage, Post-Project Collaboration, as this stage is implicitly or explicitly a part of most research projects. For example, a post-doctoral researcher expects to be credited for their work even if it is published after the end of the project. The specific challenges for each of the five stages are identified. This enables the leader to focus on a manageable number of challenges at each stage. Trust should be built during the first stage to cover four specific topics: Trust in the leader, process, evaluation method and trust in being credited in published work. Conflict does not emerge as a challenge at the initial stages but later.

Introduction

In collaboration, research teams are typically small groups of under 20 people with specific tasks (Gren et al., Citation2020; Haines et al., Citation2018). Researchers are widely utilized in research teams to carry out their primary role, research, but also a breadth of other tasks including teaching and administration. This overwhelmingly positive arrangement, unfortunately, also includes some challenges that can affect the mental health and well-being of researchers (Kismihók et al., Citation2021). Firstly, research, like innovation, involves using new methods and discovering new things. The reliable recipes that exist in other routine collaborations do not necessarily apply. Researchers often face additional challenges such as having to move country to work on a project. They may be working in a foreign country with a different culture and language. It has been shown that trust-building is more challenging in teams from different cultures in an academic setting (Cheng et al., Citation2016). The researcher’s heavy reliance on technology to fulfill tasks may also bring additional challenges that they need to overcome to achieve their goal. They must adopt the organization’s, and the project’s, systems. Other processes such as their yearly evaluation can also be different.

Researchers have highly specialized skills both on their topic, such as information systems or business, and the research methods they are familiar with, such as several qualitative and quantitative methods. This, along with the short nature of most research projects requires them to change organization, even country, regularly. These changes can include colleagues, language, national culture, organizational culture, organization systems, project systems and evaluation method. Each change brings its own distinct challenges, but they also compound other challenges. The researcher only has so many hours in a day, and they can find themselves overwhelmed and ‘defeated’ by the magnitude of the challenge.

The most widely used methods to evaluate collaboration such as co-authorship and co-patenting have many weaknesses such as not accounting for symbolic, non-substantive collaborations (Clark & Llorens, Citation2012) or the researchers mental health. Having researchers with low performance, low engagement, or having a high turnover of researchers, creates negative outcomes and waste (Froese & Mevissen, Citation2020). All forms of waste should be avoided in research (Blaine et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, researchers’ mental health is often at risk and should be supported better by the research leaders. The context the researcher finds themselves in today may be different to before COVID-19 so existing research on this topic should be re-evaluated with empirical evidence. In other forms of collaboration an accurate list of challenges has enabled leaders to make accurate adjustments to mitigate them (Dibble & Gibson, Citation2013). Therefore, the research questions are:

What are the challenges of researchers in projects?

What model of project collaboration can reduce the challenges of researchers in projects?

Research teams can have a specialized project manager, they can be led by a subject expert, or they can be led by a professor. Whether they are a specialized project manager or not, the research leader must be aware of the typical challenges that lie ahead at each stage of the process and preempt them. The research team leader must therefore have an accurate understanding of their research team, and the challenges they face in their specific context.

This research first implemented a workshop that identified that, while most of the challenges are at the start of the project, during the on-boarding process, different challenges emerge at each of the other stages also. Therefore, this research focused on developing a model of research project collaboration that would reduce the challenges. The final model identifies the specific challenges a leader should mitigate across the five stages of (1) Forming, (2) Storming, (3) Norming, (4) Adjourning and (5) Post-project collaboration.

The following section builds the theoretic foundation with the existing literature. This is then followed by the methodology section that explains how mixed methods were applied, using a workshop and a survey. The analysis and the findings are then presented. Finally, the discussion and conclusion highlight how the model can reduce the challenges faced by researchers.

Literature review

The literature review covers existing models of collaboration, the stages those models have, and how the typical challenges of collaboration map onto those stages. The existing literature from collaboration in other contexts is a foundation to guide the qualitative analysis that will, in turn, guide the quantitative analysis.

Models of collaboration

When people collaborate there are challenges that are dependent on the specific context. For this reason, several models have been developed to improve the collaboration process, especially at the start when the participants are getting to know their roles and each other (Project Management Institute, Citation2013). Several aspects of the context such as if the collaboration is online (Cheng et al., Citation2013), if it is multicultural or from one culture, have an effect.

Research on what motivates researchers to collaborate shows that there are two typical reasons: Firstly, there is the practical reason that if their work needs them to collaborate, they will, regardless of the social dynamics of the team. The second is the social reason that if they feel there is a collective responsibility, as opposed to an individual responsibility, they will collaborate (Birnholtz, Citation2007). Collective responsibility is stronger in the later stages of a collaboration, when the team is often referred to as mature (Jetter et al., Citation2016). Therefore, the literature specific to research teams suggests that these have a similar goal of becoming a mature team with collective responsibility.

There are several models with different priorities, that recommend different stages for a collaboration to go through. Despite this variety there is some convergence and strong support for a model with four stages (Tuckman & Jensen, Citation2010). These four stages, with some variations, have been supported in several contexts. A similar model, with five stages, that is widely supported in project management ads an additional stage at the end of the project called ‘project close’ (Project Management Institute, Citation2013). In addition to these models that attempt to have broad comprehensive stages, there are other models that focus on some aspects of the collaboration such as creating a shared vision and how this influences productivity (Froese & Mevissen, Citation2020). The three models discussed in this paragraph are summarized in .

Table 1. Models of collaboration, challenges and remedies.

As the four stages are valid across other contexts, the next step is to adapt them to the context of research teams. The way to do this, is to identify the specific challenges, and actions to resolve them, in each stage related to research teams.

Challenges of research teams

This research focuses on internal challenges of the team, not external challenges such as regulation or economic issues. Risk and uncertainty are usually higher at the start of a collaboration (Project Management Institute, Citation2013). In the early stages some challenges identified are lack of loyalty and trust, concerns over safety, inclusion, unclear structure and leadership, and member dependencies (Wheelan et al., Citation2020). The second phase can bring conflict between the members over the substance of the research. Sharing of necessary information, including personal information can be difficult (Haraldsdottir et al., Citation2018). This can cause delays to the on-boarding process, as the researcher might have different beliefs on what information they should share. Research has identified the importance of managing ethical issues, as these underpin several of the challenges (Müller et al., Citation2017). Another challenge, particularly at the start of a collaboration, that can be exacerbated by ethical issues, is trust (Cheng et al., Citation2016). Some people reduce their effort when working in a team compared to when they work alone. This phenomenon increases as groups get bigger. This social loafing has psycho-sociological causes (Zhu & Wang, Citation2019). The technology a project uses, both to coordinate, and for the specific project tasks, can cause difficulties, particularly to those who have not used it before (Yao et al., Citation2020). allocates the typical challenges identified in the literature across the four stages of collaboration identified in the previous section. The challenges coming from the context, or elsewhere, have been shown to raise issues of trust, privacy, ethics and even safety.

Table 2. Challenges mapped across stages.

Table 3. Demographic information of the participants surveyed.

Studies that focused more on the project tasks rather than the psycho-social dimension often refer to low efficiency, low effectiveness and low team maturity in the early stages (Ramírez-Mora et al., Citation2020). Despite the focus on the deliverables these issues encompass many of the psycho-social issues identified above.

Methodology

Workshop

The workshop brought together academics from a large European country, Germany, and a small one, Cyprus to discuss the challenges in research projects. Evaluating projects and leadership in two countries, with different characteristics, to achieve a more holistic understanding, is a beneficial approach (Zaman et al., Citation2020). All the participants had experience working on research projects. The participants had either been research associates, had supervised researchers or both. Three participants came from a small EU country and had worked as a researcher in a large European country, and two had supervised researchers from small EU countries. Therefore, the group of five, an ideal size for a workshop (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994), were knowledgeable on the issues discussed. The primary investigator took notes, and no recording was made to respect the participants’ privacy. The workshop had four periods of approximately 15–20 minutes. The workshop findings were analyzed by identifying central themes, and linking the related comments to them, so that a deeper understanding of the issues is achieved (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994).

Survey

Once the model with five stages and the list of challenges within those stages were compiled, a survey was implemented to test the model. Each challenge was tested to see if it has a significant relationship with the stage it belongs to in the model. The data was analyzed using Partial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) with the SmartPLS software.

The data collection was in Europe. The participants had to have experience as researchers on projects in universities. Due to this requirement the data collection took two months until enough surveys were completed. The survey had five sections, one covering each stage of the research project. Several checks were made to remove invalid survey responses. These included removing the responces that were incomplete, gave the same answer to all the questions or were completed too quickly. The 331 participants came from the following European countries: Germany (81), Ireland (39), Poland (35), Cyprus (34), Romania (28), Austria (24), Netherlands (22), France (21), Greece (14), Hungary (9), Belgium (9), Spain (8) and Italy (7). Participants were given a gift voucher of 5 euro.

Findings

The findings cover the workshop, the model proposed, and the evaluation of the model with a survey.

Workshop

The workshop had four periods of approximately 15–20 minutes: First (1) the group discussed their experiences on these issues. The next stage attempted to clarify (2) if it is a different experience for researchers from different countries and cultures. The following two related points covered were (3) the challenges for researchers associates, and the challenges of those supervising them. The focus then moved on to (4) how can this research support a better outcome for research projects their leaders.

Several challenges were identified, and it was believed that some exist throughout the project while others only apply to certain stages. Technology plays an important role in research, and the participants believed that it raises some challenges across the whole project. Researchers have very diverse academic backgrounds. This results in some researchers that are very strong in adopting and using technology, know how to troubleshoot and solve problems, and have coding experience. Other researchers may be far weaker on the practical aspects of using technology and have strengths in other areas such as psychology and consumer behavior. An example was given of having to understand an encryption method just to be able to read an email informing a researcher of where a meeting was. If they were not a researcher on a short project, they may have not been expected to be able to do this without training.

Many challenges mentioned were related to money and bureaucracy. These had many direct and indirect effects. The small amount of money available leads to short contracts on low wages. Researchers have less resources to adapt and may end up with accommodation, and living conditions, that are less than ideal. Finding accommodation is often very time consuming, taking up to three months. This challenge may not be specific to researchers, as many people in Europe face difficulties finding accommodation. The challenges caused by bureaucracy are exacerbated by having to communicate in a foreign language and having a dependence on technology. Researchers from small countries are less likely to find positions in their country, or in their language, so they may face these issues more often. The way they were evaluated was also not ideal as they are often expected to target the highest-ranking journals, which take a long time to get published, often beyond the period of the contract. Therefore, even if they are successful in achieving a publication in a high-ranking journal, this may come after they are evaluated as researchers. Furthermore, the project they worked on may carry on after they leave, and they may not get credit for their work.

The challenges for the supervisors of research associates were also related to money and bureaucracy in many cases. Professors that have larger teams, including a dedicated administrator and IT expert, are in a far better position to navigate the process of hiring and managing researchers. In addition to limited funds, other resources such as office space and laptops may be in short supply. Supervisors emphasized the variability in the cost reward ratio, as strong researchers were a blessing while weaker researchers consumed more time and resources than their contribution would make up for. In many cases the supervisors spent far more time than they should have to, supporting researchers. The role was described as unorthodox due to the breadth of support usually needed. It was also described as an abstract uncharted challenge. The supervisors also emphasized the many different tasks they had and how the multitasking was challenging. The positives were also emphasized, and the publications the stronger researchers offer are very beneficial to the professor’s career and help them attract funding.

Challenges related to different cultural expectations, knowledge sharing and the lack of a new vision towards the end of the project were identified. It was acknowledged by the participants that the researcher’s mental health is often at risk due to the challenges, especially the uncertainty, risk and lack of trust and that this was more serious at the start and the end. The participants did not find one, or a small number of factors, causing the challenges to mental health but believed it was the cumulative effect of many factors that caused it.

Recommended model

Based on the literature and the workshop, a model for reducing the challenges for researchers in projects is proposed, as illustrated in . This model is explored further and validated by the quantitative analysis. The proposed model identifies the specific challenges a leader should mitigate across the five stages of (1) Forming, (2) Storming, (3) Norming, (4) Adjourning and (5) Post-project collaboration. The first four stages are supported extensively across a variety of projects. The fifth stage was added because of the particular nature of research projects. Researchers participate in projects for several reasons, including the network of contacts that can be made, and the opportunity to collaborate in the future. Therefore, the final stage ‘closeout’ (Project Management Institute, Citation2013), needs to be adapted for a research team as the fifth stage is not always the end of the team members collaboration and work continues beyond the end of the project.

Table 4. Recommended model of the challenges of research projects mapped across stages.

Evaluation of the model

The quantitative analysis first evaluated the measurement model and then the structural model. The measurement model measures how well the observed items represent the latent variable. The structural mode measures the relationship between the latent variables. As this research is validating the five steps, and not the relationship between them, the five steps were evaluated separately.

Measurement model

The reflective measurement model was measured using the factor loading, Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and Fornell-Larcker Criterion as illustrated in , (Hair et al., Citation2021).

Table 5. Results of the measurement model analysis for the Forming stage.

Table 6. Results of the measurement model analysis for the Storming stage.

Table 7. Results of the measurement model analysis for the Norming stage.

Table 8. Results of the measurement model analysis for the Adjourning stage.

Table 9. Results of the measurement model analysis for the Post-Project Collaboration stage.

Table 10. Results of the structural model for Forming.

Table 11. Results of the structural model for Storming.

Table 12. Results of the structural model for Norming.

Table 13. Results of the structural model of Adjourning.

Table 14. Results of the structural model for post-project collaboration.

Stage 1: The factor loadings of the items are all above the required level of 0.7 with the lowest being 0.884. The Composite Reliability for the latent variables are all above 0.7 with the lowest being 0.918. The Average Variance Extracted also surpasses the required threshold. For AVE it is 0.5 and the lowest value is 0.769. The Fornell-Larcker Criterion showes a satisfactory discriminant validity, as the observed variables have a stronger correlation with their latent variable, than with any other latent variable.

Stage 2: The factor loadings of the items are all above 0.7, with the lowest being 0.871. The Composite Reliability for the latent variables are all above 0.7, with the lowest being 0.909. The Average Variance Extracted also surpasses the required threshold of 0.5, with the lowest value is 0.769. The Fornell-Larcker Criterion shows a satisfactory discriminant validity.

Stage 3: The factor loadings of the items are all above 0.7, with the lowest being 0.820. The Composite Reliability for the latent variables are all above 0.7, with the lowest being 0.912. The Average Variance Extracted also surpassed the required threshold of 0.5, as the lowest value is 0.775. The Fornell-Larcker Criterion shows a satisfactory discriminant validity.

Stage 4: The factor loadings of the items are all above 0.7, with the lowest being 0.851. The Composite Reliability for the latent variables are all above 0.7, with the lowest being 0.836. The Average Variance Extracted surpasses the required threshold of 0.5, as the lowest value is 0.629. The Fornell-Larcker Criterion shows a satisfactory discriminant validity.

Stage 5: The factor loadings of the items are all above the required 0.7, with the lowest being 0.812. The Composite Reliability for the latent variables are all above 0.7, with the lowest being 0.812. The Average Variance Extracted also surpasses the required threshold of 0.5 as the lowest value is 0.695. The Fornell-Larcker Criterion shows a satisfactory discriminant validity.

Structural model

Stage 1-Forming: The structural model evaluated the relationship between the nine variables representing different challenges and the Forming variable. The Bootstrapping method was used to find the p-values of each relationship. The structural model for the forming stage showed that all the values meet the criteria of being below 0.05, apart from Conflict (FCON) that has a p-value of 0.058 (Hair et al., Citation2021). Therefore, Conflict is not considered to be one of the challenges of this stage.

Stage 2-Storming: The structural model for the second stage, Storming, showed that all the values meet the criteria of being below 0.05, apart from Conflict (SCON) that has a p-value of 0.081 (Hair et al., Citation2021). Therefore, conflict is not considered to be one of the challenges of this stage.

Stage 3-Norming: The structural model of the third stage, Norming, showed that all the values meet the criteria of being below 0.05, apart from Technological Challenges (NTC) that has a p-value of 0.100 (Hair et al., Citation2021). Therefore, the technological challenges are not considered to be one of the main challenges of this stage.

Stage 4-Adjourning: The structural model for the fourth stage, Adjourning, showed that all the values meet the criteria of being below 0.05, apart from Technological Challenges (ATC) that has a p-value of 0.790 (Hair et al., Citation2021). Therefore, the technological challenges are not considered to be one of the main challenges of this stage.

Stage 5-Post-Project Collaboration: The structural model for the fifth stage, Post-Project Collaboration, showed that all the values meet the criteria of being below 0.05, apart from Technological Challenges (PTC) that has a p-value of 0.295 and Conflict (PCON) that has a p-value of 0.074 (Hair et al., Citation2021). Therefore, the technological challenges are not considered to be one of the main challenges of this stage.

Discussion and conclusion

In other forms of collaboration an accurate list of challenges has enabled leaders to make precise adjustments to mitigate them (Dibble & Gibson, Citation2013). This research compiles an accurate list of challenges in research projects and provides a model mapping them across five stages of collaboration. There are both theoretic and practical contributions.

Theoretic contribution

This research extended models of projects to the special circumstances of research teams. This is necessary for three main reasons (1) firstly many research teams do not apply existing project management processes because they either do not know them or do not find them relevant, (2) existing models do not capture the challenges of research teams, (3) mental health is not explicitly identified in existing models as a priority. While many leaders see pressure as a positive thing that encourages team members to be productive, this pressure is not always positive. When it comes from issues not related to the project goals, such as accommodation and no job security, this pressure is counterproductive and should be reduced.

This research also answers the call for more research on leadership and projects with a temporal dimension (Hemshorn de Sanchez et al., Citation2022). Some challenges exist in only one stage of the process, while other challenges are across several stages. It is notable that there is no conflict at the start, but trust is a challenge at the start. This suggests that low trust at the start causes problems later. Therefore, there is a delayed reaction, and once the conflict happens it might be too late, as the trust should have been built earlier. Therefore these findings support and extend research in projects in other contexts that identify the risk of conflict being higher at the end of the project rather than the start (Project Management Institute, Citation2013; Wheelan et al., Citation2020). It may be too challenging for the leader to resolve conflict and built trust at the same time. Trust is important in several collaboration settings, particularly at the start, until participants familiarize themselves with each other and the project team matures. In research teams, due to the long period of time until the research is published, often over three years, there is an additional, long-term cause for risk and distrust that is only resolved once the research is published.

While the role of technology, in online, face-to-face or blended team collaborations is increasing, the most important role is still played by the social and psychological aspects of the team (Haines et al., Citation2018). Mental health was a challenge across the four traditional stages of the project and the post-project collaboration. The pressure on mental health is caused by a combination of the many challenges.

The model put forward takes the traditional, proven four stages of collaboration and ads a fifth, the collaboration beyond the project. For universities and researchers creating long term sustainable networks it is important (Damrich et al., Citation2022). The sums of money spent on research are often spent in the hope that beyond the immediate goals being achieved by the project, a network or ecosystem will be triggered. Therefore, this fifth stage is important in the context of research.

Practical contribution: How research project leaders can support better outcomes

Researchers are often different to other professionals working in teams, as they usually expect individual recognition for their work. In addition to recognition, the researcher should be able to pursue the project’s deliverables without jeopardizing their health.

This research supports a better outcome by identifying the challenges across five stages. The model for reducing the challenges for researchers in projects, presented in , enables the leader to focus on specific challenges at each of the five stages of the project. For example, trust should be built during the first stage to cover four specific topics, even if there is no conflict at that point. Another example is how a new vision needs to be communicated effectively (Nathues et al., Citation2021) in the final two stages as the original vision stops resonating after the Norming stage.

The leader should be ambidextrous, in the sense of focusing on the project deliverables on the one hand, and the social and psychological aspects of the teamwork on the other. This research enables more focused leadership tactics across the five stages of the research team development. Previous research has attempted this in other contexts, such as software development or innovation (Gren et al., Citation2020; Super, Citation2020). For the challenges that cannot be solved outright, the leader must show an awareness (Project Management Institute, Citation2013).

The audience of this research is primarily research project leaders, but others may find it useful such as researchers themselves, university management, and those in government involved in higher education. Beyond the immediate leaders of the research team, governments can provide more effective platforms that support the whole process and reduce the burden on researchers. Specific training can also be made available as this has been shown to have benefits (Gren et al., Citation2020). The benefit is not only through the knowledge gained, but also by convincing people of the value of leading research team in a way that puts mental health first.

Limitations and future research

The findings of this research should be seen alongside of some typical limitations: Firstly, the sample was collected from the Europe. While research teams around the world use similar practices the model should be validated in other parts of the world. Secondly, the model of the steps of research teams put forward in this research, balances team performance and researchers’ mental health. Other contexts require a different balance of priorities. For example, in other contexts physical safety is a higher priority. Therefore, the model applies best to this specific context.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alex Zarifis

Dr Alex Zarifis is a lecturer at the University of Southampton. He has taught and carried out research at several universities including the University of Manchester and the University of Cambridge. He has over 40 publications in the areas of project management, leadership, online collaboration, privacy and trust. He has worked on large EU and UK funded research projects at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) and Loughborough University. He obtained his PhD from the University of Manchester.

Xusen Cheng

Professor Xusen Cheng is a Professor at Renmin University of China in Beijing. He obtained his PhD degree from the University of Manchester, UK. His research is in the areas of information systems and management particularly focusing on online collaboration, global teams, the sharing economy, e-commerce and e-learning.

References

- Birnholtz, J. P. (2007). When do researchers collaborate? Toward a model of collaboration propensity. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(14), 2226–2239. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20684

- Blaine, C., Brunnhuber, K., & Lund, H. (2021). Against Research Waste – How the Evidence-Based Research paradigm promotes more ethical and innovative research. In LSE Blog. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2021/02/04/against-research-waste-how-the-evidence-based-research-paradigm-promotes-more-ethical-and-innovative-research/.

- Cheng, X., Fu, S., Sun, J., Han, Y., Shen, J., & Zarifis, A. (2016). Investigating individual trust in semi-virtual collaboration of multicultural and unicultural teams. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.093

- Cheng, X., Macaulay, L., & Zarifis, A. (2013). Modeling individual trust development in computer mediated collaboration: A comparison of approaches. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1733–1741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.018

- Clark, B. Y., & Llorens, J. J. (2012). Investments in scientific research: Examining the funding threshold effects on scientific collaboration and variation by academic discipline. Policy Studies Journal, 40(4), 698–729. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2012.00470.x

- Damrich, S., Kealey, T., & Ricketts, M. (2022). Crowding in and crowding out within a contribution good model of research. Research Policy, 51(1), 104400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2021.104400

- Dibble, R., & Gibson, C. (2013). Collaboration for the common good: An examination of challenges and adjustment processes in multicultural collaborations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(6), 764–790. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1872

- Froese, A., & Mevissen, N. (2020). Failure through success: Co-construction processes of imaginaries (of participation) and group development. Science Technology and Human Values, 45(3), 455–487. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243919864711

- Gren, L., Goldman, A., & Jacobsson, C. (2020). Group- development psychology training the perceived effects. IEEE Software, 37(3), 63–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496408328703.64

- Haines, R., Scamell, R. W., & Shah, J. R. (2018). The impact of technology availability and structural guidance on group development in workgroups using computer-mediated communication. Information Systems Management, 35(4), 348–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/10580530.2018.1503805

- Hair, J., Hult, T., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) (3rd ed.). Sage Publishing.

- Haraldsdottir, R. K., Gunnlaugsdottir, J., Hvannberg, E. T., & Holdt Christensen, P. (2018). Registration, access and use of personal knowledge in organizations. International Journal of Information Management, 40, 8–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.01.004

- Hemshorn de Sanchez, C. S., Gerpott, F. H., & Lehmann-Willenbrock, N. (2022). A review and future agenda for behavioral research on leader–follower interactions at different temporal scopes. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 43(2), 342–368. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2583

- Jetter, A., Albar, F., & Sperry, R. C. (2016). The practice of project management in product development: Insights from the literature and cases in high-tech. PMI Sponsored Research.

- Kismihók, G., Cahill, B., Gauttier, S., Metcalfe, J., Mol, S., McCashin, D., Lasser, J., Günes, M., Schroijen, M., Grund, M., Levecque, K., Guthrie, S., Wac, K., Dahlgaard, J., Adi, M., & Kling, C. (2021). Researcher Mental Health and Well-being Manifesto. October https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5559805

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis. Sage Publications.

- Müller, R., Turner, J. R., Andersen, E. S., Shao, J., & Kvalnes, Ø. (2017). Governance and ethics in temporary organizations: The mediating role of corporate governance. Project Management Journal, 47(6), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/875697281604700602

- Nathues, E., van Vuuren, M., & Cooren, F. (2021). Speaking about vision, talking in the name of so much more: A methodological framework for ventriloquial analyses in organization studies. Organization Studies, 42(9), 1457–1476. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840620934063

- Project Management Institute. (2013). A guide to the project management body of knowledge (PMBOK guide) (5th ed.). Project Management Institute Inc.

- Ramírez-Mora, S. L., Oktaba, H., & Patlán Pérez, J. (2020). Group maturity, team efficiency, and team effectiveness in software development: A case study in a CMMI-DEV Level 5 organization. Journal of Software, 32(4), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/smr.2232

- Super, J. F. (2020). Building innovative teams: Leadership strategies across the various stages of team development. Business Horizons, 63(4), 553–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2020.04.001

- Tuckman, B. W., & Jensen, M. A. C. (2010). Stages of small-group development revisited group facilitation. Group Facilitation: A Research and Applications Journal, 10, 43–48.

- Wheelan, S. A., Akerlund, M., & Jacobsson, C. (2020). Creating effective team: A guide for members and leaders (6th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Yao, X., Zhang, C., Qu, Z., & Tan, B. C. Y. (2020). Global village or virtual balkans? evolution and performance of scientific collaboration in the information age. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 71(4), 395–408. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24251

- Zaman, U., Nadeem, R. D., & Nawaz, S. (2020). Cross-country evidence on project portfolio success in the Asia-Pacific region: Role of CEO transformational leadership, portfolio governance and strategic innovation orientation. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1727681. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1727681

- Zhu, M., & Wang, H. (2019). Social loafing and group development. International Journal of Services, Economics and Management, 10(1), 55–67. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSEM.2019.098937