?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Social media platforms have been major channels for consumers to search for product-related information, compare market prices, and consult other experienced buyers. Particularly, social media influencers play a crucial role in consumers’ decision-making process. Scholars have confirmed that information-seeking behavior enhances the efficiency of decision-making. However, a fundamental question arises about what other variables influence the relationship between information-seeking behavior and consumer efficiency. By combining the theory of consumer shopping productivity and para-social interaction, this study proposed a model that explains how information-seeking behavior enhances consumer efficiency through social media influencers and consumer knowledge. The study further extends the theory of consumer shopping productivity to a social commerce setting. This study used representative data from a national survey through face-to-face interviews in Taiwan. The results identified consumer knowledge as the strongest variable in the consumer decision-making process. Furthermore, social media influencer exposure moderately helps consumers to make efficient decisions. Finally, consumer knowledge moderates the relationship between information-seeking behavior and perceived consumer efficiency.

1. Introduction

The rise of social media has empowered individuals to seek, select, and assess information (Cropf, Citation2008), while also reshaping the ways in which purchasing decisions are optimized through features such as subscriptions and interactions with social media influencers and other savvy buyers. Therefore, social media has become a popular source for buying and selling products. Taiwanese users mainly search for information from social media platforms (YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, and forums) (Kemp, Citation2023). The information that Taiwanese users consider most helpful in making purchase decisions is product-comparison, expert’ opinions, online user reviews, and word of mouth (Kemp, Citation2023). While the information is rich, the vast mount of information from different sources can cause users to be overloaded.

User-generated market-related content, social media influencers, social networks, and marketplace information overload transform the way people gain market knowledge and make purchasing decisions (Chen et al., Citation2017; Erkan & Evans, Citation2018). The product information available on social media is from mixed sources. Some are users sharing authentic personal experiences, and others are paid messages disguised as user recommendations. The abundance of product information online might not help the consumer make efficient decisions. Consumer efficiency refers to ‘obtaining the best price and quality of products with the least time and effort’ (Atkins & Kim, Citation2012; Voropanova, Citation2015). With too much information, consumers might spend time and energy processing information and might get confused or overwhelmed. Sufficient information is needed to make a good decision, but excessive information may hinder the decision-making process (Aw et al., Citation2021; Flavián et al., Citation2020).

Studies have mentioned the influence of information seeking, word of mouth, and purchase intention. Specifically, information-seeking behavior affects shopping decisions (Atkins & Kim, Citation2012; Hill & Beatty, Citation2011; Shengli & Fan, Citation2019; Voropanova, Citation2015). In addition, online word of mouth positively influences consumers’ decision-making (Wang et al., Citation2021), and online purchase intention (Davis, Citation2017; Taylor & Levin, Citation2014). However, studies of product information-seeking behavior have lacked consideration of the social networking process. Studies regarding consumer decision-making mainly focused on digital technology, shopping motivation, and information processing, but overlooked the aspect of shopping efficiency (Lăzăroiu et al., Citation2020; Qin et al., Citation2021; Sharma et al., Citation2023). Shopping efficiency studies examined factors in the context of shopping websites and mobile devices, but were not focused on social media (Frick & Matthies, Citation2020; Voropanova, Citation2015; Yilmaz & Temizkan, Citation2020). In addition, consumer knowledge helps people go through the decision-making process when shopping, assisting people as they search for information and evaluate and compare products (Karimi et al., Citation2015). However, the extent to which consumer knowledge interacts with information seeking and social media influencer exposure in influencing shopping efficiency has not been extensively explored.

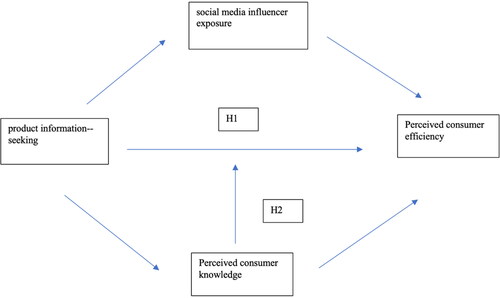

This research gap calls for future investigation of consumer efficiency on social media, incorporating the influence of social media influencer exposure (SMIEX) and consumer knowledge. Therefore, the purpose of this study is twofold. First, I intend to examine whether social commerce-related behaviors contribute to consumer decision-making when there is a surplus of market information on social media. Second, I will explore what increases the efficiency of decision-making and influences how decisions are made. In terms of theoretical contribution, this study identifies three distinct factors—product information-seeking behavior, SMIEX, and consumer knowledge—each helps to explain a specific facet of consumer efficiency. In terms of practical contribution, this study helps improve consumer efficiency on social media by recognizing its factors.

First, I will introduce the concept of consumer efficiency. Then, I will address the constructs of consumer efficiency, as well as its antecedents (product information-seeking), mediators (SMIEX and perceived consumer knowledge), and perceived consumer knowledge as a moderator. Findings from quantitative research combined with parasocial interaction theory and social learning theory will provide rationales for the model. Survey data of 1823 respondents serve to assess the model and hypotheses. Finally, discussion, limitations, and ideas for future research appear.

2. Literature review

2.1. Consumer efficiency

Consumer efficiency, smart shopping, and shopping productivity are similar concepts that refer to the difference between the costs and the benefits of a purchase process (Atkins & Kim, Citation2012; Voropanova, Citation2015). The cost of shopping includes time, effort, and energy spent on researching (searching for product information and price comparisons) before purchase. The benefits involve utilitarian (when obtaining a necessary and quality product) and hedonic benefits (pleasure and satisfaction). Consumers derive consumer efficiency when they obtain the greatest shopping outcome (right purchase, good deal, good quality, and satisfaction, etc.) with the least input (Atkins & Kim, Citation2012; Voropanova, Citation2015).

Voropanova (Citation2015) mentioned four dimensions of the conceptualization of consumer shopping productivity: right purchase, pleasure, time/effort saving, and money saving. Similarly, Ingene (Citation1984) mentioned information obtained and time invested during shopping process are elements of shopping productivity. Combining Voropanova (Citation2015) and Ingene (Citation1984)’s idea of consumer shopping productivity, several factors were identified: Interactive information communication technology, the value of information, and shopping time (Ingene, Citation1984; Voropanova, Citation2015). Social media influencers influence followers by generating content about brands, products, and market knowledge. Interactions with experienced buyers create para-social relationships that offer a social learning in users’ purchase decisions (Sokolova & Kefi, Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2021), followers gain the knowledge from social media influncers and thus enhance their consumer efficiency. Therefore, by combining the conceptulization of consumer shopping productivity and para-social interaction, this study further examined the influence of SMIEX and consumer knowledge on the relationship between information-seeking and consumer efficiency.

Interactive information communication technology increases consumer efficiency as ICTs provide easy access to product information, minimizing the cost of information searching (Aw et al., Citation2021; Kim & LaRose, Citation2006). Consumers collect product information, reviews, and prices to determine the best fit and assess risks resulting from purchasing mistakes. Interactive communication technology helps users collect useful information (Park & Park, Citation2009). Sufficient, useful, and easy-access product-related information can help consumers make good decisions quickly (Aw et al., Citation2021; Voropanova, Citation2015).

On social media, interactive communication includes interaction with social media influencers. People learn what is acceptable and how to avoid risks from observing and imitating the social media influencers’ behavior (Lorenzo et al., Citation2012). Consumers tend to search word-of-mouth reviews online to manage purchase and product risks. Word-of-mouth learning enhances consumers’ search, evaluation, and purchasing efficiency (Wang et al., Citation2021). Opinions from experts and experienced buyers assist in selecting helpful information from an abundance of brands and unhelpful messages (Sokolova & Kefi, Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2021). Product reviews help consumers evaluate the quality efficiently (Wulandari & Rauf, Citation2022). Social learning increases decision efficiency, especially when (1) consumers have a utilitarian motivation or strong motivation; (2) when consumers need to save time and energy on shopping (Wang et al., Citation2021). Previous studies (Azzara et al., Citation2023; Moretti, Citation2011; Voropanova, Citation2015; Wang et al., Citation2021) have extensively looked into how social learning and information-seeking behavior improve consumer efficiency. However, whether information searching behavior and social media influencers help consumers make decisions efficiently in a social media context full of excessive information has been overlooked in shopping productivity and social commerce literature.

2.2. The relationship between product information-seeking behavior and perceived consumer efficiency

In social commerce, consumers are inclined to search user comments online to minimize risk when buying a new product (Bansal & Voyer, Citation2000; Wang et al., Citation2021). Information-seeking behavior positively influences consumer efficiency (Hill & Beatty, Citation2011; Park & Park, Citation2009; Sproles et al., Citation1978). Sproles and colleagues found that sufficient information increases consumer efficiency (Sproles et al., Citation1978). Information about a product brand and price level is helpful for product evaluation and consumers’ efficiency in decision-making increases as they are provided with an increasing amount of information. Information-seeking behavior plays a crucial role in acquiring enough information. The results of Sproles’ study showed a significant difference in the ability to make the right purchase (the ability to purchase good quality products) between those with more information and those with less information (Sproles et al., Citation1978).

Recently, scholars have shifted focus to information found on social media and have similar findings. Wang et al. (Citation2021) found that Electronic Word of Mouth (EWOM) positively influences the decision efficiency of the online shopping process. The information about other consumers’ experiences and comments is informative and comprehensive, which saves consumers’ time and energy when making purchasing decisions. Wang and colleagues also discovered that EWOM reinforces shoppers’ intrinsic motivation (e.g. the curiosity to try a specific product because of personal experience), increasing consumer efficiency. Similarly, Shengli and Fan (Citation2019) found that online reviews and product ratings from users are more persuasive than advertisers in downloading software, suggesting that information searching behavior helps consumers make decisions based on more credible information than advertising (Shengli & Fan, Citation2019). In addition, Adolescents with information-searching skills can also make the right purchase. They have a relative influence on household purchase decision-making, suggesting that adolescents with better information-searching skills than their parents are knowledgeable about market information and help parents make more efficient purchasing decisions (Hill & Beatty, Citation2011).

As a result, information-searching behavior is positively associated with consumer efficiency. The following hypothesis is posited:

H1 Product information-seeking behavior on social media is positively related to consumer efficiency.

2.3. The mediation role of social media influencer exposure (SMIEX)

Horton and Wohl (Citation1956) introduced the theory of parasocial interaction, suggesting that a viewer could be subconsciously influenced by a performer due to the perceived intimacy in their relationship, which resembles that of genuine interpersonal connections (Dibble et al., Citation2016; Kelman, Citation1958). Parasocial interaction theory explains why influencers are influential in endorsing brands. Followers feel connected to brands and positively influence purchase intention through interaction with social media influencers (Sokolova & Kefi, Citation2020; Sokolova & Perez, Citation2021). Based on this theory, through reading posts, watching videos, commenting, and sharing messages from social media influencers, followers are influenced unconsciously by the perceived values of product brand perceptions. Interaction with social media influencers enhances their purchase intention (Lee & Watkins, Citation2016; Sokolova & Kefi, Citation2020).

Sokolova’s and Lee & Watkins’ arguments suggest a mediation relationship between product information-seeking behavior and consumer efficiency through SMIEX as a mediator (Lee & Watkins, Citation2016; Sokolova & Kefi, Citation2020; Sokolova & Perez, Citation2021). Product information-seeking behavior on social media may be positively associated with consumer efficiency (Erkan & Evans, Citation2018; Park & Park, Citation2009). However, in the current media environment full of mixed product information, information-seeking behavior alone is insufficient to deal with the overload. Social media influencers’ opinion is what many users consult before making purchasing decisions (Beer, Citation2018; Harrigan et al., Citation2021).

Social media influencers influence followers’ attitudes toward and perceptions of a product in two ways. The first is credibility. Social media influencers are market mavens because of their product knowledge and proficiency (Aljukhadar et al., Citation2019). Market mavens are more credible and persuasive than advertising (Lou & Yuan, Citation2019; McGuire, Citation2001; Venciute et al., Citation2023). Relying on credible products makes the purchase decision-making process efficient. The second way that social media influencers affect their followers is through para-social interaction. Social media influencers build their influence by socializing with followers (Aljukhadar et al., Citation2019; Fan et al., Citation2024; Kiani & Laroche, Citation2019). For example, through socializing with influencers, followers gain more affection for a product and internalize the influencers’ experiences and attitudes towards a product, which, in turn, enhances the followers’ purchase intention (Sokolova & Kefi, Citation2020). Consumer efficiency results from socialization as users share and discuss product information and personal experiences (Hill & Beatty, Citation2011). According to social learning theory which indicates that individuals’ learning process is dependent on social interactions (Bandura, Citation1977). People make satisfying choices by observing others’ behavior (Wang et al., Citation2021). In other words, the knowledge followers learn from social media influencers helps followers make efficient purchas decisions (Jiménez-Castillo & Sánchez-Fernández, Citation2019). Thus, social media influencer exposure might directly increase consumer efficiency.

2.4. The influence of consumer knowledge on consumer efficiency

Social commerce gives users easy access to excessive product-related information. However, the abundance of product information may be a double-edged sword in purchasing. The abundance of information is not always helpful for making purchase decisions because not all information online fits consumers’ needs (Marsden et al., Citation2006; Phillips-Wren & Adya, Citation2020). Users spend more time and energy processing the information and may need more consistent information, thus rendering decision-making harder and inefficient (Jiang et al., Citation2022). Research has explored how consumer knowledge increases consumer efficiency. Consumer knowledge refers to familiarity with market information, prices, stores and brands (Clark et al., Citation2001). Consumer knowledge is helpful for product evaluation and reducing perceived risk (Nepomuceno et al., Citation2014; Sproles et al., Citation1978). The cost and energy of information searching can also be decreased through consumer knowledge (Park & Kim, Citation2008). Social media influencers may help individuals make purchasing decisions, and consumer knowledge serves as a moderator in the relationship between product information seeking and perceived consumer efficiency.

Social commerce includes two behaviors related to consumer knowledge: Network expansion and knowledge creation. Network expansion refers to the idea that users subscribe to channels, follow brands’ social media accounts, join forums and fan pages, and interact with other users for rich information (Aljukhadar et al., Citation2019). Consumer knowledge is generated from network expansion. Product reviews and shopping experiences users share help consumers better understand marketplaces. Social media users create and disseminate consumer knowledge on social media platforms and thus help users have maven-like behaviors (Aljukhadar et al., Citation2019), suggesting that through social learning from social networks, individuals gain knowledge and make efficient purchase decisions.

2.5. Consumer knowledge as a moderator

Cervi and Brei (Citation2022) has shown that consumer efficiency depends on the level of consumer knowledge. On social media full of mixed product information, including paid advertising and authentic information, people who can find helpful information make purchase decisions quickly, but those less knowledgeable about the product might get lost in the overflow of information (Jiang et al., Citation2022). For example, consumers with low levels of knowledge had more difficulties making decisions than those with higher levels of knowledge (Cervi & Brei, Citation2022). Thus, the relationship between product information-seeking behavior and consumer efficiency may be contingent on the level of consumer knowledge.

Voropanova (Citation2015) examined how different amounts of market knowledge impact shopping efficiency in the context of mobile phone usage. The results showed that individuals keen to search for more information are better than those who search for less information regarding the amount of product knowledge, the depth of analysis, and the evaluation of the purchase outcome. Therefore, individuals with more knowledge make more efficient purchase decisions than those without knowledge (Voropanova, Citation2015). Karimi et al. (Citation2015) found that compared to consumers with a higher level of knowledge, those with a lower level have more alternatives and spend more time making decisions. In other words, consumers with less knowledge cannot decide as efficiently as those with more knowledge (Karimi et al., Citation2015). The findings indicate that information-searching behavior can help an individual make purchase decisions efficiently, but the efficiency level depends on consumer knowledge. Therefore, the following hypothesis is posited:

H2 Consumer knowledge moderates the relationship between product information-seeking behavior and consumer efficiency.

The conceptual framework of consumer efficiency is proposed in .

3. Method

The study used representative data from the Taiwan Communication Survey (TCS), a national survey done through a face-to-face interview conducted by Academia Sinica, a national academy of Taiwan. TCS is an annual nationwide survey that focuses on how new communication technology benefits people’s daily lives.

The population was Taiwanese residents over 18 years of age. With Stratified Multi-Stage Probability Proportional to Size Sampling, the Taiwan area was divided into seven primary levels and 19 sublevels to ensure the sample’s representativeness. For the first three stages, we used systematic sampling to sample cities and counties, then to sample townships and villages, and in the third step, we sampled households. In each household we sampled, we randomly selected one member within each household to interview. The response rate was 30.05%, and the refusal rate was 12.2%. The total valid sample size was 2109.

3.1. Sample

This study weight data based on census data released from The Ministry of the Interior (responsible for national interior affairs such as population and land, etc.) under Executive Yuan of Republic of China. The study used raking ratio estimation to weight the data. Raking formula:

wfin: final weights

Wsel: unequal probabilities of selection, sampling weights

N: The number of the population

n: The number of the valid sample

Ni: The number of the population of each variable

ni: The number of the valid sample of each variable

Chi-Square Goodness of Fit Test was used to examine if the sample matches the population. After weighting, the sample matches the population in terms of gender, age, and education. See .

Table 1. A comparison of the sample and population by gender, age, and education after raking.

As this study explores consumer behavior on social media, it is relevant to understand the respondents’ usage patterns. The respondents use social media frequently. The result showed that 1823 respondents use social media. They spent 5.9 days a week on Facebook (M = 5.93, Mdn = 7, SD = 1.99), 4.9 days a week on Instagram (M = 4.9, Mdn = 7, SD = 2.5), and five days a week on Youtube (M = 5.05, Mdn = 7, SD = 2.30).

3.2. Measurement

3.2.1. Product information-seeking behavior

The measurement is self-developed based on the concept and measurements of consumer information seeking behavior from previous studies (Chaturvedi et al., Citation2016; Kiel & Layton, Citation1981). Product information-seeking behavior measures the frequency of searching for product reviews and comments from social media influencers and online users before buying a product. On a 4-point scale from 1 (never) to 4 (always), the respondents were asked (1) how often do you search online for product information (product introduction, reviews, and comments) from social influencers and (2) how often do you search online for product information (product introduction, reviews, and comments) from online users (M = 2.15, SD = 1.13).

3.2.2. Perceived consumer knowledge

Adapted from the idea of product knowledge, market knowledge, and market maven (Aljukhadar et al., Citation2019; Cacciolatti et al., Citation2015; Clark et al., Citation2001), consumer knowledge includes familiarity with product information and the ability to evaluate the quality of a product. On a 5-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), consumer knowledge was measured by (1) I am more knowledgeable about a product because of the product information from social media influencers and online users I found online (M = 4.03, SD = .62), (2) I have the ability to evaluate the quality of a product because of product information from social media influencers and online users I found online (M = 3.67, SD = .79). The responses were summed and averaged into an index with acceptable reliability (M = 3.85, SD = .62, Cronbach alpha = .70) (DeVellis, Citation2003; Kline, Citation2005).

3.2.3. Social media influencer exposure

This study adopts the measurement of Social Media Influencer from Pan et al. (Citation2022) and the measurement of exposure to influencers’ social media from Chae (Citation2018); both measurements used a Likert scale to measure the frequency of social media influencers exposure. Respondents were asked how often they encounter influencer-generated content on social media, from 1(never) to 4 (always). (M = 2.45, SD = 1.18).

3.2.4. Perceived consumer efficiency

Consumer efficiency refers to making the right purchase and purchasing a product while spending less time, money, and energy (Atkins & Kim, Citation2012; Voropanova, Citation2015). Respondents were asked to evaluate how social media influencers and online users helped them. On a 5-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), Respondents evaluated the likeliness of three different statements (a, b, & c): The product information from social media influencers and online users I found online helps me (a) save more time when deciding which product to buy (M = 3.79, SD=.81), (b) save more money on purchasing a product (M = 3.58, SD = .84), and (c) purchase the product I need. (M = 3.63, SD = 0.79). These responses were averaged into an index with acceptable reliability (M = 3.67, SD = 0.68, Cronbach’s α = .80).

4. Results

Overall, age is negatively significantly related to social media influencer exposure (SMIEX)(r = -.55, p < .05), consumer knowledge (r = -.16, p < .05), and consumer efficiency (r = -.20, p < .05), suggesting that younger individuals are more likely than older individuals to search for product information from social media influencers and online users, to be exposed to information shared by social media influencers, have higher consumer knowledge, and shop more efficiently online. Consumer knowledge (r = .33, p < .05), income (r = .1, p < .05), and consumer efficiency (r = .38, p < .05) and SMIEX (r = .56, p < .05) are positively associated with product-information searching, suggesting that individuals who search product-information online have higher market-knowledge, income, consumer efficiency and being exposed to information shared by social media influencers than those who do not search product-information from social media influencers and online users.

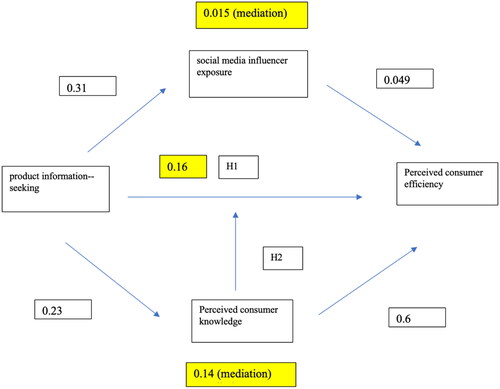

H1 hypothesized that product information-seeking behavior on social media is positively related to consumer efficiency. The result showed that product information-seeking behavior is positively related to consumer efficiency (β = .17, p < .001). H1 is supported. Hierarchical multiple regression was conducted to examine the degree to which product information-seeking, consumer knowledge, and social media influencer exposure predict consumer efficiency. Consumer knowledge (β = .53, p < .001) was the strongest predictor and uniquely accounted for 25% (sr = .5) of the variance in consumer efficiency. Product information-seeking behavior (β = .17, p < .001) was the second strongest predictor and uniquely accounted for 2.3% (sr = .15) of the variance in consumer efficiency. Social media use and influencer exposure were not associated with consumer efficiency ().

Table 2. Hierarchical OLS regression of predictors for perceived consumer efficiency.

4.1. Mediation model analysis

To explore how product information-seeking behavior increases consumer efficiency, I used the PROCESS macro for SPSS to conduct mediation analysis. The PROCESS procedure for model 6 was used to evaluate direct and indirect effects (Hayes & Little, Citation2018). Both direct and indirect effects were found, and based on 5,000 bootstrap samples, these effects had 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (Hayes & Little, Citation2018).

Social Media Influencer Exposure mediates the relationship between product information-seeking behavior and consumer efficiency. Relative to those who seek product information online less frequently, those who seek product information online are more frequently exposed to social media influencers (as a1 is positive), which in turn was associated with the increase in consumer knowledge, and this increase translated into a greater consumer efficiency (because b2 is positive). Overall, consumer knowledge is the strongest predictor of consumer efficiency.

4.2. Moderation analysis

A hierarchical multiple regression was conducted to examine H2, consumer knowledge moderates the relationship between product information-seeking behavior and consumer efficiency. There was a statistically significant moderator effect of consumer knowledge, as evidenced by adding the interaction term explaining an additional 0.5% of the total variance, p < .01. A GLM test revealed the difference in consumer efficiency between high and low consumer-knowledge individuals. Those with high consumer knowledge had a predicted consumer efficiency of 3.84, while the score was 3.3 for those with low consumer knowledge. The difference in consumer efficiency for low consumer knowledge individuals (M = 3.302, SE = .034) and high consumer knowledge individuals (M = 3.85, SE = .021) was .55, 95% CI [.469, .625], p < .001. The results are shown in :

5. Discussion

While previous researchers examined information-seeking behavior (Bennett & Mandell, Citation1969; Case, Citation2010; Chaturvedi et al., Citation2016) in the process of consumer decision-making and the influence of social media influencers on consumers’ buying behaviour, the current study links these two variables with perceived consumer knowledge. This study examines how engaging in social media activities, such as seeking product information and exposure to social media influencers, relates to consumer knowledge and efficiency. The main research question focuses on how product information-seeking behavior and social media influencer exposure enhance consumer efficiency and to what degree. The result confirms existing research that information-seeking behavior and consumer knowledge facilitate the consumer decsisions-making process (Hill & Beatty, Citation2011; Karimi et al., Citation2015; Park & Kim, Citation2008; Park & Park, Citation2009). At the same time, this study identifies consumer knowledge as a major variable associated with perceived consumer efficiency. Additionally, the results echo previous studies that social media influencers help consumers make decisions (Jiménez-Castillo & Sánchez-Fernández, Citation2019; Venciute et al., Citation2023), but the benefit of social media influencer exposure is limited. SMIEX has only an indirect effect on consumer efficiency. Overall, the findings suggest that the major factor in increasing consumer efficiency lies in individuals’ information-seeking behavior and knowledge. Dependency on social media influencers without one’s knowledge proves ineffectual in facilitating efficient decision-making processes. The following findings merit notice.

5.1. Knowledge is power

The wealth of product information on social media can either help or retard consumers’ decision-making, depending on consumers’ knowledge. The results aligned with a previous study that showed that users with high consumer knowledge make efficient decisions (Cervi & Brei, Citation2022). In contrast, those with low consumer knowledge make inefficient decisions, as evidenced by a moderation model indicating that consumer knowledge moderates the relationship between product information-seeking behavior and consumer efficiency.

The findings reveal that exposure to an abundant information environment is insufficient for making efficient decisions because excessive product information online contains brand messages, misleading and useful information, thus making people overloaded (Al-Youzbaky et al., Citation2022; Singh et al., Citation2023). Particularly, social media is full of personal experiences, opinions, and product reviews shared by ordinary users and mavens. Exposed to an information-rich environment where professional opinion, paid brand message, and personal comments are mixed, consumers have to be able to evaluate what information is suitable and what is not. This study suggests that those who perceive themselves as possessing high consumer knowledge can avoid unhelpful information and get useful information that helps make decisions.

However, for those with insufficient consumer knowledge, the abundance of product information undermines their efficiency. Being unfamiliar with a product, they spend more time and energy locating useful information and processing it. In addition, users make poor decisions when overwhelmed by excessive information (Huang & Zhou, Citation2019; Huseynov et al., Citation2016; Zhang et al., Citation2018).

This finding explains information avoidance phenomenon where information-seekers ignore the excessive amount of information to avoid information overload, which results in poor decision-making and confusion (Marsden et al., Citation2006; Sweeny et al., Citation2010). In contrast, other information seekers who strive for adequate information are able to process much more information (Voropanova, Citation2015). The difference between those who can process extensive information and those who are not lies in the amount of knowledge they possess.

5.2. SMIEX moderately increases perceived consumer knowledge

Given the significant role of perceived consumer knowledge in the social commerce shopping process, the current study found two variables that enhance perceived consumer knowledge. The first one is product information-seeking behavior. The result showed a positive relationship between product information-seeking behavior and consumer knowledge, suggesting that consumers increase their knowledge by obtaining knowledge from the product information on social media. In addition, the results showed that those who seek product information on social media usually have higher consumer knowledge than those who do not. In the context of social commerce, consumers with sufficient knowledge also have rich information sources and know where to collect information. The positive relationship between information-seeking and consumer knowledge is dynamic and reciprocal. Though a causal relationship cannot be asserted, a positive relationship is confirmed.

Seeking product information online increases social media influencer exposure, suggesting that the sharing of product information by social media influencers turns users who search for product information into their viewers. This finding proves that consumers treat social media influencers as information channels for seeking product information. Exposure to social media influencers moderately enhances perceived consumer knowledge. In other words, individuals who encounter information from social media influencers occasionally gain consumer knowledge. The reason might be that only some of the content from social media influencers is product-information-related but can increase knowledge on a small scale. As Wasike’s study showed, social media influencer exposure helps users gain knowledge, but mildly (Wasike, Citation2023).

5.3. Social media influencers slightly increase perceived consumer efficiency

The current study answered the question: Does exposure to social media influencers increase consumer efficiency? The finding revealed that social media influencers increase consumer efficiency, but mildly. Among predictors of consumer efficiency, product information seeking, perceived consumer knowledge, and social media influencer exposure, the effect of SMIEX on consumer efficiency is the weakest (b1 = .0049).

The study investigated the role of SMIEX in the relationship between product information-seeking behavior and perceived consumer efficiency. The result showed that SMIEX mediates the relationship between product information-seeking behavior and consumer efficiency. To be specific, opinion leaders who filter and decode brand messages for followers help a consumer make efficient decisions in an environment of information overload. Although not all the content generated by social media influencers is product-related, consumers observe their actions and adapt their behaviors based on social learning theory. Followers unconsciously form their perceptions, attitudes, and knowledge from social media influencers by accessing the general content they share (Aljukhadar et al., Citation2019). In addition to content created by social media influencers, discussions with other followers have also influenced consumers’ perceptions. Followers gain knowledge from socializing with other social media users, and word of mouth improves purchase decision efficiency (Aljukhadar et al., Citation2019; Wang et al., Citation2021).

Although the indirect effect of social media influencer exposure on product information-seeking behavior and perceived consumer efficiency is modest, the effect is confirmed. This result is supported by other studies indicating that influencers’ experiences have an impact on their followers’ purchasing behaviors (Sokolova & Kefi, Citation2020; Venciute et al., Citation2023). Specifically, role models such as entertainers and athletes positively influence the market knowledge of teenagers because role models are credible and provide essential market information (Clark et al., Citation2001). The study discovered that social media influencers not only influence their followers’ perceptions but also consumer efficiency.

Combining the theories of consumer’ shopping productivity and parasocial interaction (Horton & Wohl, Citation1956), this study proposed a model that explains how information-searching behavior enhances consumer efficiency through social media influencers and consumer knowledge. Based on parasocial interaction theory, influencers can impact followers’ brand perceptions and purchasing intentions (Lee & Watkins, Citation2016; Sokolova & Kefi, Citation2020; Sokolova & Perez, Citation2021). This study further found that influencers moderately increase followers’ consumer knowledge and thus enhance their consumer efficiency. This study further extends the theory of consumers’ shopping productivity to the social commerce setting by incorporating the SMIEX, and also discovers that consumer knowledge moderates the relationship between information-seeking behavior and perceived consumer efficiency.

Although the evidence found in this study has provided some important insights, some questions remain. This study measures users’ perception of consumer efficiency instead of an objective measurement of consumer knowledge and efficiency. This study can only identify how users perceive themselves. This study could be improved by finding a more specific way to distinguish between the consumer knowledge levels of users and their efficiency. In addition, the influence of social media influencer exposure this study examined included general content generated by social media influencers, which fails to distinguish the exclusive effect of branded content created by social media influencers. Future studies are encouraged to measure ‘branded messaging from social media influencers’ alone to better assess the impact of product information provided by social media influencers on consumer efficiency.

6. Conclusion

As social media has become a primary source consumers turn to before making purchase decision, the research aimed to examine what makes consumer decision-making efficient within the abudance of information on social media. In addition to product information-seeking behavior, the study incorporates SMIEX and consumer knowledge to investigate the factors of consumer efficiency. The results confirm previous findings that product information-seeking behavior and consumer knowledge are both significant factors in enhancing consumer efficiency (Hill & Beatty, Citation2011; Karimi et al., Citation2015; Park & Kim, Citation2008; Park & Park, Citation2009). However, this study reveals that information-seeking behavior alone is not enough to make an efficient decision. The influence of consumer knowledge is stronger than product information-seeking behavior, suggesting that those with high consumer knowledge are capable of product-information seeking and thus making efficient decisions.

Regardless of the positive influences of social media influencers on brand endorsement and followers’ purchase intention (Sokolova & Kefi, Citation2020; Sokolova & Perez, Citation2021), the current finding showed that the effect of social media influencers in enhancing consumer knowledge and consumer efficiency is not as strong as expected. Social media influencers’ mildely increase perceived consumer knowledge and efficiency. Overall, the findings highlight the significance of consumer knowledge in enhancing consumer efficiency. Individuals with high consumer knowledge are proficient in recognizing useful information among the information flood on social media.

By identifying consumer knowledge as the strongest variable in the consumer decision-making process, and further revealing the moderate effect of SMIEX on consumer knowledge, the theoretical implication of this study demonstrates a holistic picture explaining the moderation role of consumer knowledge in the relationship between product information seeking behavior and consumer efficiency. The practical implication suggests that social media influencers might not be the best source for gaining consumer knowledge. Future studies are recommended to explore causal relationship between information-searching ability and consumer efficiency. Therefore, the research contributes to a better understanding of factors enhancing consumer knowledge and consumer efficiency in decision-making process.

Author contributions

The author confirms sole responsibility for the following: study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation of results; the drafting of the paper, revising it critically for intellectual content; and the final approval of the version to be published.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in [OSF] at https://osf.io/tj7z4/.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Victoria Y. Chen

Victoria Y. Chen is an Associate Professor in the Department of Communication & Graduate Institute of Telecommunications, National Chung Cheng University in Taiwan. Her research focuses on news consumption behavior, digital journalism, misinformation and information process. Her research has been published in referred journals such as Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, Mass Communication and Society, Journalism Practice, Journal of Information Technology & Politics, Atlantic Journal of Communication, The Agenda Setting Journal. She was awarded two research awards in 2022: The Selection of Innovative Research and Development Results by Young Scholars Award and Promising Young Scholar Research Award. She has published several articles about media literacy for high school students. Before receiving her Ph.D. from The University of Texas at Austin, she was a TV show director at a national TV network in Taiwan. Before that, she was a journalist in a community media in Los Angles in the U.S.

References

- Aljukhadar, M., Senecal, S., & Bériault Poirier, A. (2019). Social media mavenism: Toward an action-based metric for knowledge dissemination on social networks. Journal of Marketing Communications, 26(6), 636–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2019.1590856

- Al-Youzbaky, B. A., Hanna, R. D., & Najeeb, S. H. (2022). The effect of information overload, and social media fatigue on online consumers purchasing decisions: the mediating role of technostress and information anxiety. Journal of System and Management Sciences, 12(2), 1–16.

- Atkins, K. G., & Kim, Y. K. (2012). Smart shopping: Conceptualization and measurement. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 40(5), 360–375. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590551211222349

- Aw, E. C. X., Basha, N. K., Ng, S. I., & Ho, J. A. (2021). Searching online and buying offline: Understanding the role of channel-, consumer-, and product-related factors in determining webrooming intention. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 58, 102328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102328

- Azzara, R. C., Simanjuntak, M., Retnaningsih, R., & Yandri, Y. (2023). The influence of self-sufficiency, information seeking, and knowledge towards smart purchasing behavior in indonesia. Jurnal Aplikasi Bisnis Dan Manajemen, 9(1), 12–12. https://doi.org/10.17358/jabm.9.1.12

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs.

- Bansal, H. S., & Voyer, P. A. (2000). Word-of-mouth processes within a services purchase decision context. Journal of Service Research, 3(2), 166–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/109467050032005

- Beer, C. (2018). Social Browsers Engage with Brands. Global Web Index. https://blog.gwi.com/chart-of-the-day/social-browsers-brand/

- Bennett, P. D., & Mandell, R. M. (1969). Prepurchase information-seeking behavior of new car purchasers: The learning hypothesis. Journal of Marketing Research, 6(4), 430. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150076

- Cacciolatti, L. A., Garcia, C. C., & Kalantzakis, M. (2015). Traditional food products: The effect of consumers’ characteristics, product knowledge, and perceived value on actual purchase. Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing, 27(3), 155–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/08974438.2013.807416

- Case, D. O. (2010). A model of the information seeking and decision making of online coin buyers. Information Research, 15(4), 14–15.

- Cervi, C., & Brei, V. A. (2022). Choice deferral: The interaction effects of visual boundaries and consumer knowledge. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 68, 103058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103058

- Chae, J. (2018). Explaining females’ envy toward social media influencers. Media Psychology, 21(2), 246–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2017.1328312

- Chaturvedi, S., Gupta, S., & Hada, D. S. (2016). Perceived risk, trust and information seeking behavior as antecedents of online apparel buying behavior in India: An exploratory study in context of Rajasthan. International Review of Management and Marketing, 6(4), 935–943.

- Chen, A., Lu, Y., & Wang, B. (2017). Customers’ purchase decision-making process in social commerce: A social learning perspective. International Journal of Information Management, 37(6), 627–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2017.05.001

- Clark, P. W., Martin, C. A., & Bush, A. J. (2001). The effect of role model influence on adolescents’ materialism and marketplace knowledge. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 9(4), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.2001.11501901

- Cropf, R. A. (2008). Benkler, Y.(2006). The wealth of networks: how social production transforms markets and freedom. Yale University Press. 528 pp. $40.00 (papercloth). Social Science Computer Review, 26(2), 259–261.

- Davis, K. M. (2017). Social media, celebrity endorsers and effect on purchasing intentions of young adults. West Virginia University.

- DeVellis, R. F. (2003). Scale development: Theory and applications. Sage.

- Dibble, J. L., Hartmann, T., & Rosaen, S. F. (2016). Parasocial interaction and parasocial relationship: Conceptual clarification and a critical assessment of measures. Human Communication Research, 42(1), 21–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/hcre.12063

- Erkan, I., & Evans, C. (2018). Social media or shopping websites? The influence of eWOM on consumers’ online purchase intentions. Journal of Marketing Communications, 24(6), 617–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2016.1184706

- Fan, L., Wang, Y., & Mou, J. (2024). Enjoy to read and enjoy to shop: An investigation on the impact of product information presentation on purchase intention in digital content marketing. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 76, 103594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103594

- Flavián, C., Gurrea, R., & Orús, C. (2020). Combining channels to make smart purchases: The role of webrooming and showrooming. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 52, 101923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101923

- Frick, V., & Matthies, E. (2020). Everything is just a click away. Online shopping efficiency and consumption levels in three consumption domains. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 23, 212–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2020.05.002

- Harrigan, P., Daly, T. M., Coussement, K., Lee, J. A., Soutar, G. N., & Evers, U. (2021). Identifying influencers on social media. International Journal of Information Management, 56(June 2020), 102246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102246

- Hayes, A. F., & Little, T. D. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis : A regression-based approach. A Division of Gilford Publications, INC. https://www.guilford.com/books/Introduction-to-Mediation-Moderation-and-Conditional-Process-Analysis/Andrew-Hayes/9781462534654

- Hill, W. W., & Beatty, S. E. (2011). A model of adolescents’ online consumer self-efficacy (OCSE). Journal of Business Research, 64(10), 1025–1033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2010.11.008

- Horton, D., & Wohl, R. R. (1956). Mass communication and para-social interaction: Observations on intimacy at a distance. Psychiatry, 19(3), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1956.11023049

- Huang, J., & Zhou, L. (2019). The dual roles of web personalization on consumer decision quality in online shopping: The perspective of information load. Internet Research, 29(6), 1280–1300. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-11-2017-0421

- Huseynov, F., Huseynov, S. Y., & Özkan, S. (2016). The influence of knowledge-based e-commerce product recommender agents on online consumer decision-making. Information Development, 32(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266666914528929

- Ingene, C. A. (1984). Productivity and functional shifting in spatial retailing-private and social perspectives. Journal of Retailing, 60(3), 15–36.

- Jiang, S., Ng, A. Y. K., & Ngien, A. (2022). The effects of social media information discussion, perceived information overload and patient empowerment in influencing HPV knowledge. Journal of Health Communication, 27(6), 407–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2022.2115591

- Jiménez-Castillo, D., & Sánchez-Fernández, R. (2019). The role of digital influencers in brand recommendation: Examining their impact on engagement, expected value and purchase intention. International Journal of Information Management, 49(February), 366–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.07.009

- Karimi, S., Papamichail, K. N., & Holland, C. P. (2015). The effect of prior knowledge and decision-making style on the online purchase decision-making process: A typology of consumer shopping behaviour. Decision Support Systems, 77, 137–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2015.06.004

- Kelman, H. C. (1958). Compliance, identification, and internalization three processes of attitude change. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2(1), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/002200275800200106

- Kemp, S. (2023). Digital 2023: Taiwan. DataReportal. Retreived from https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-taiwan

- Kiani, I., & Laroche, M. (2019). From desire to help to taking action: Effects of personal traits and social media on market mavens’ diffusion of information. Psychology & Marketing, 36(12), 1147–1161. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21263

- Kiel, G. C., & Layton, R. A. (1981). Dimensions of consumer information seeking behavior. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(2), 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800210

- Kim, J., & LaRose, R. (2006). Interactive e-commerce: Promoting consumer efficiency or impulsivity? In Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2004.tb00234.x

- Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guildford.

- Lăzăroiu, G., Neguriţă, O., Grecu, I., Grecu, G., & Mitran, P. C. (2020). Consumers’ decision-making process on social commerce platforms: Online trust, perceived risk, and purchase intentions. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 890. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00890

- Lee, J. E., & Watkins, B. (2016). YouTube vloggers’ influence on consumer luxury brand perceptions and intentions. Journal of Business Research, 69(12), 5753–5760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.171

- Lorenzo, O., Kawalek, P., & Ramdani, B. (2012). Enterprise applications diffusion within organizations: A social learning perspective. Informationi & Manaagement, 49(1), 47–57.

- Lou, C., & Yuan, S. (2019). Influencer Marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 19(1), 58–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2018.1533501

- Marsden, J. R., Pakath, R., & Wibowo, K. (2006). Decision making under time pressure with different information sources and performance-based financial incentives: Part 3. Decision Support Systems, 42(1), 186–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2004.09.013

- McGuire, W. J. (2001). Input and output variables currently promising for constructing persuasive communication. In R. E. Rice & C. K. Atkin (Eds.), Pubic communication campaign (3rd ed., pp. 22–48). Sage.

- Moretti, E. (2011). Social learning and peer effects in consumption: Evidence from movie sales. The Review of Economic Studies, 78(1), 356–393. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdq014

- Nepomuceno, M. V., Laroche, M., & Richard, M. O. (2014). How to reduce perceived risk when buying online: The interactions between intangibility, product knowledge, brand familiarity, privacy and security concerns. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 21(4), 619–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2013.11.006

- Pan, W., Mu, Z., & Tang, Z. (2022). Social media influencer viewing and intentions to change appearance: a large scale cross-sectional survey on female social media users in China. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 846390. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.846390

- Park, D. H., & Kim, S. (2008). The effects of consumer knowledge on message processing of electronic word-of-mouth via online consumer reviews. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 7(4), 399–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2007.12.001

- Park, M., & Park, J. (2009). Exploring the influences of perceived interactivity on consumers’ e-shopping effectiveness. Journal of Customer Behaviour, 8(4), 361–379. https://doi.org/10.1362/147539209X480990

- Phillips-Wren, G., & Adya, M. (2020). Decision making under stress: The role of information overload, time pressure, complexity, and uncertainty. Journal of Decision Systems, 29(sup1), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/12460125.2020.1768680

- Qin, H., Peak, D. A., & Prybutok, V. (2021). A virtual market in your pocket: How does mobile augmented reality (MAR) influence consumer decision making? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 58, 102337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102337

- Sharma, P., Ueno, A., Dennis, C., & Turan, C. P. (2023). Emerging digital technologies and consumer decision-making in retail sector: Towards an integrative conceptual framework. Computers in Human Behavior, 148, 107913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107913

- Shengli, L., & Fan, L. (2019). The interaction effects of online reviews and free samples on consumers’ downloads: An empirical analysis. Information Processing & Management, 56(6), 102071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2019.102071

- Singh, P., Sharma, B. K., Arora, L., & Bhatt, V. (2023). Measuring social media impact on impulse buying behavior. Cogent Business & Management, 10(3), 2262371. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2262371

- Sokolova, K., & Kefi, H. (2020). Instagram and YouTube bloggers promote it, why should I buy? How credibility and parasocial interaction influence purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 53, 101742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.01.011

- Sokolova, K., & Perez, C. (2021). You follow fitness influencers on youtube. But do you actually exercise? How parasocial relationships, and watching fitness influencers, relate to intentions to exercise. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 58(1), 102276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102276

- Sproles, G., Geistfeld, L., & Suzanne, B. (1978). Informational inputs as influences on efficient consumer decision-making. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 12(1), 88–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.1978.tb00635.x

- Sweeny, K., Melnyk, D., Miller, W., & Shepperd, J. A. (2010). Information avoidance: Who, what, when, and why. Review of General Psychology, 14(4), 340–353. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021288

- Taylor, D. G., & Levin, M. (2014). Predicting mobile app usage for purchasing and information-sharing. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 42(8), 759–774. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-11-2012-0108

- Venciute, D., Mackeviciene, I., Kuslys, M., & Correia, R. F. (2023). The role of influencer–follower congruence in the relationship between influencer marketing and purchase behaviour. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 75, 103506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103506

- Voropanova, E. (2015). Conceptualizing smart shopping with a smartphone: implications of the use of mobile devices for shopping productivity and value. International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 25(5), 529–550. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2015.1089304

- Wang, F., Wang, M., Wan, Y., Jin, J., & Pan, Y. (2021). The power of social learning: How do observational and word-of-mouth learning influence online consumer decision processes? Information Processing & Management, 58(5), 102632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2021.102632

- Wasike, B. (2023). The influencer sent me! Examining how social media influencers affect social media engagement, social self-efficacy, knowledge acquisition, and social interaction. Telematics and Informatics Reports, 10, 100056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.teler.2023.100056

- Wulandari, I., & Rauf, A. (2022). Analysis of social media marketing and product review on the marketplace shopee on purchase decisions. Review of Integrative Business and Economics Research, 11(1), 274.

- Yilmaz, K., & Temizkan, V. (2020). Smart shopping experience of customers using mobile applications: A field research in Karabuk/Turkey. Gaziantep University Journal of Social Sciences, 19(3), 1237–1254. https://doi.org/10.21547/jss.653689

- Zhang, H., Zhao, L., & Gupta, S. (2018). The role of online product recommendations on customer decision making and loyalty in social shopping communities. International Journal of Information Management, 38(1), 150–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2017.07.006