?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The travel restrictions imposed during the Covid-19 pandemic have expedited the adoption of Virtual Reality (VR) technology as a substitute for traditional tourism experiences. This study delves into the impact of personality traits, perceived enjoyment, and anticipated flow state on the inclination to embrace Virtual Reality (VR) technology for tourism purposes in South Africa. Furthermore, this research probes into the moderating role of trust in VR technology within these relationships. Survey data from 361 millennial South African tourists were employed, with structural equation modelling and multi-group analysis as the primary analytical methods. Results highlight curiosity as a key personality trait influencing perceived enjoyment and flow state. Both perceived enjoyment and anticipated flow state significantly affect the intention to adopt VR technology for tourism. Notably, the role tourists’ trust in VR technology is demonstrated as critical in the usage for tourism. This research offers unique insights into drivers of VR technology for tourism and have practical implications for destination marketing and tourism development, especially in culturally diverse emerging markets such as by South Africa.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered long-term shifts in how people consume tourism and leisure offers (Lee & Kim, Citation2021). Subsequently, greater focus has been placed on technological tools such as virtual reality (VR) that allow individuals to experience tourism offerings amidst travel restrictions. As defined by Yung and Khoo-Lattimore (Citation2019, p. 2057), VR is ‘the use of a computer-generated three dimensional (3D) environment, that one can navigate and possibly interact with, resulting in real-time simulation of one of the five senses’. VR therefore includes three main functions: immersion, visualisation, and interactivity (Flavián et al., Citation2021; Lee & Kim, Citation2021). In the context of tourism, VR allows visitors to be immersed in an interactive experience whereby they preview destinations and make more informed decisions (Yung et al., Citation2021) through the stimulation of senses such as vision and hearing (Lee & Kim, Citation2021). VR therefore provides an immersive environment where the tourist is isolated from the real world by wearing a head-mounted display (HMD) which allows for a full 3D experience to be enjoyed (Lee & Kim, Citation2021; Talukdar & Yu, Citation2021).

The adoption of technology in tourism has been widely researched in the current tourism and destination marketing literature, with greater emphasis placed on the adoption of artificial intelligent-based technologies (Flavián et al., Citation2021; Huang et al., Citation2021). Of those that have focused on VR, most studies (Huang et al., Citation2016; Yung & Khoo-Lattimore, Citation2019) have relied on the Self-determination Theory (SDT), Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and deriving theories such as the and Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) (Huang, Citation2023; Sánchez et al., Citation2021). These frameworks, while valuable, often focus on rational and utilitarian aspects of adoption and may not fully capture the intricacies of complex adoption decisions driven by immersive experiences. Technology adoption models such as the TAM and UTAUT are useful in explaining the adoption of intrinsic or hedonic motivation systems (Kim & Hall, Citation2019). However, Lowry et al. (Citation2013) express concern about the models’ ability to explain a state of deep involvement, immersion and temporal dissociation, which amongst other factors, arises through heightened enjoyment (Kim & Hall, Citation2019). Moreover, although Kim and Hall (Citation2019) have relied on the Hedonic Motivation System Adoption Model to explain the impact of VR technology on sport spectators, they suggest that alternative models should be adopted to better examine the drivers of VR technology usage for tourism activities.

Recognising this limitation, the present study integrates the flow theory with personality traits to embrace a more holistic perspective that transcends the traditional technology adoption frameworks. To fully capture tourists’ virtual experiences and the immersive nature of VR, visitors’ flow state can be integrated as a key component of that experience (Chang & Chiang, Citation2022). Flow is a state of hyperfocus that results in complete engagement to the extent that people become deeply immersed in the activity that they lose track of time (An et al., Citation2021; Huang et al., Citation2018). In light of the growing prevalence of technology in our daily lives, there is a heightened interest into the role that electronic devices such as VR technologies play in facilitating flow experiences (Barta et al., Citation2021). In that vein, recent review by da Silva deMatos et al. (Citation2021) acknowledges the seminal work of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi as a catalyst for inquiry to study flow in various contexts, including tourism, sport, psychology and education. While earlier studies around the concept of flow state were more commonly associated with sport and its ability to influence motivation, peak performance and enjoyment in performing an activity (Jackson & Marsh, Citation1996), da Silva deMatos et al. (Citation2021) review underscores the necessity for additional research into the concept of flow within the context of tourism experiences. The integration of flow state fits well within the context of tourism via VR technology as it provides a theoretical background to the hedonic and relaxing experiences and positive emotions, such as happiness, pleasure and excitement that VR technology provides tourists (Kim & Hall, Citation2019; Zeng et al., Citation2022).

Personality traits inherently shape how individuals engage with novel experiences and technologies, which in turn affects their propensity to immerse themselves in flow states during VR interactions for tourism (Srivastava et al., Citation2022; Watjatrakul, Citation2020). Integrating personality traits’ influence and the immersive nature of flow state offers insights into how certain traits might amplify or inhibit the likelihood of users engaging with VR tourism content on a profound level. For example, Kranjčev and Hlupić (Citation2021) demonstrated that the intensity at which people experience flow state significantly varies across the different dimensions of personality traits. Investigating how personality traits viewed as intrinsic psychological predispositions interact with immersive states to influence adoption intention provides a unique perspective on the adoption of VR technology in the travel and tourism industries.

Furthermore, it is imperative to recognize the pivotal role that consumer trust plays in shaping the landscape of technology adoption, as underscored within the existing literature (Belanche et al., Citation2012; Indarsin & Ali, Citation2017). However, a notable scholarly gap emerges, revealing a dearth of comprehensive research on the potential role of moderators in impacting the adoption of VR technology in tourism (Fan et al., Citation2022). Of particular interest is the moderating impact of consumer trust toward adopting VR technology for tourism. Therefore, this study not only probes into the interplay that unfolds between selected personality traits, flow state and the intention to adopt VR technology but also how these relationships may vary among tourists’ levels of trust in VR technology. In doing so, this research provides novel insights into the adoption of VR technology in the travel and tourism industries, offering a unique perspective within an emerging economy context.

Emerging as a dynamic market, South Africa stands out for its profound cultural diversity, historical significance, and unique attractions for tourists (Giampiccoli et al., Citation2015; Mokoena, Citation2020). The country boasts renowned touristic destinations such as the world-famous Kruger National Park, breathtaking mountains such as the Table Mountain in Cape Town, and poignant historical sites including Nelson Mandela’s house and the apartheid museum in Soweto. Consequently, South Africa is recognised as a premier global tourism destination and a preferred choice within the African continent (Mokoena, Citation2020; South African Tourism, Citation2022). This distinction is evidenced by the influx of international tourists, which reached 2.92 million in 2022, resulting in a total foreign direct expenditure of 1.42 billion USD, and reflecting a decrease compared to the pre-COVID-19 pandemic figure of 4 billion USD (South African Tourism, Citation2022). The unique cultural background of South Africa emphasises the need for linking personality traits, flow experiences, trust, and the intent to adopt VR technology in this culturally rich setting. Moreover, the exploration of VR technology adoption for tourism within the South African context becomes particularly compelling due to the country’s relatively modest adoption of such technology. Recent research by Woyo and Nyamandi (Citation2022) highlights the hesitations of South African runners toward using VR technologies during an international marathon in Cape Town. Therefore, examining the adoption of VR technology assumes paramount importance to foster a shift toward technology adoption. Such an endeavour not only enriches the broader theory of technology adoption but also furnishes practical insights for designing culturally attuned VR experiences in the realm of tourism. As South Africa exhibits a unique cultural landscape an in-depth exploration of these facets will offer a holistic perspective that contributes to the scholarly discourse on technology adoption and its real-world applications.

Theoretical underpinning

The theoretical arguments of this study are underpinned by an integration of the flow theory and selected personality traits.

The flow theory

Flow is as an enjoyable experience created through intense concentration in fulfilling a task (Huang et al., Citation2018). While the idea of flow has existed for hundreds of years, research into the concept of ‘Flow’ originated in 1976 through the work of Csikszentmihalyi (Barta et al., Citation2021; Csikszentmihalyi et al., Citation2017). The theory was constructed on the basis of an observation that enjoyment was expressed by people embarking on work more than leisure activities and investigated the reasons behind it, which consequently, resulted in enjoyment emerging as a central component of Flow (Csikszentmihalyi et al., Citation2017).

Flow has a set of conditions that need to be met in order for it to be experienced (Hamari et al., Citation2016). Firstly, the challenge of the task must match perceived skill. In cases, where the challenge it too easy it may result in boredom or relaxation, however if the task is deemed too difficult it causes weariness and panic which is later followed by anxiety (Csikszentmihalyi et al., Citation2017; Huang et al., Citation2018; Jackman et al., 2021). Other characteristics required for Flow to take place include, a deep sense of concentration or intense focus in the activity that one is engaged in to the extent of being unaware of external stimuli in the environment, alignment of both awareness and action, a feeling of complete control over what is being done and needs to be done, an experience of time moving quicker than usual (Jackman et al., 2021), and performing a task that feels personally rewarding on an intrinsic level (Pelet et al., Citation2017).

Modern technologies, through the use of stimulating graphic interfaces and rich multimedia, allow user experiences to be increasingly engaging and exciting (Lowry et al., Citation2013) creating an environment where an individual’s attitude towards the increased use of technology can change (Whittaker et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, the excitement that accrues from using technology translates into enjoyment, a feeling of control and total immersion (Huotari & Hamari, Citation2017). With specific reference to technology adoption, Flow has been applied in the contexts of online purchasing (Wu et al., Citation2016), compulsive smart-phone use (Chen et al., Citation2017), and gamification of learning environments (Hamari et al., Citation2016). Of specific importance to this study, it has also been applied to testing the participation of users in virtual travel communities (Gao et al., Citation2017), VR worlds for destination marketing (Huang, Citation2023) and purchase intentions for travel through social media (Kim et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, Jamshidi et al. (Citation2018) posited that the state of flow can be a predictor of both attitude and usage; a statement agreed with by van Pinxteren et al.(2019), who stated that flow is an important predictor of technology adoption. This provides validation for the inclusion of this theory within this study.

Personality traits

Personality traits refer to enduring and relatively stable patterns that influence and shape the way individuals think, feel, and behave over time (Jani, Citation2014; McCrae & Costa, Citation1987). These traits serve as underlying tendencies that guide and determine people’s thoughts, emotions, and actions in various situations they encounter throughout their life (Jani, Citation2014). Several studies have provided convincing evidence supporting the link between individual personality characteristics and behavioural outcomes across a wide range of domains, including decision-making processes, interpersonal interactions, goal pursuit, and response to environmental stimuli (Chittaranjan et al., Citation2011; Flavián et al., Citation2022; González-González et al., Citation2021). For example, Jani (Citation2014) established relationships between personality traits and tourists’ behaviour on the Internet, finding that the usage of travel information sought through the Internet varied depending on visitors’ personality traits. Similarly, González-González et al. (Citation2021) reported that the personality traits of frontline employees in the hospitality industry influenced their willingness to suggest and implement changes within their organizations. Flavián et al. (Citation2022) examine how the personality traits of virtual team members impact the efficiency of the team through trust in the leader and team commitment. Personality traits have also been found to significantly influence consumers’ needs when consuming luxury services, such as premium seats in a sports stadium (Chang et al., Citation2019), as well as consumers’ adoption of new technology (Srivastava et al., Citation2022; Watjatrakul, Citation2020).

Within the tourism industry, personality traits play a pivotal role in shaping consumers’ inclinations and viewpoints concerning tourist destinations, activities, and overall experiences. A case in point is illustrated by Tešin et al. (Citation2023), who highlight the considerable influence of tourists’ personality traits on their creation of positive and lasting memories during visits to specific tourist sites. In a similar vein, Fanea-Ivanovic et al. (Citation2023) demonstrates that visitors’ perceived value of a touristic destination is contingent upon their distinct personality traits.

Extant literature proposes various frameworks to describe individuals’ personalities that define behavioural patterns. Among the various frameworks, the five-factor model (FFM) or the Big Five developed by McCrae and Costa (Citation1987) has gained significant recognition and is widely employed in contemporary research (Fanea-Ivanovic et al., Citation2023; Tešin et al., Citation2023). This framework categorise personality into five fundamental traits that shape human behaviour (Watjatrakul, Citation2020). The five dimensions typically included in the Big Five are openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. These personality traits remain relatively stable across time and cultures (Barnett et al., Citation2015), providing a comprehensive framework for understanding individual differences.

On the one hand, personality trait such as openness and extraversion have been constantly reported being more inclined to adoption of new technology (Flavián et al., Citation2022; Srivastava et al., Citation2022; Tešin et al., Citation2023; Watjatrakul, Citation2020). Among the various personality traits, openness to experience has emerged as the most dominant personality traits associated with tourism experience (Tešin et al., Citation2023) and adoption of new technologies (Srivastava et al., Citation2022). Individuals scoring high on this trait exhibit characteristics such as curiosity, innovativeness, imagination, and open-mindedness, making them more inclined to explore and adopt novel technologies. Openness to experience consistently emerges as a positive predictor of technology adoption because open individuals are more receptive to new ideas, adventurous, and enjoy intellectual stimulation (Fanea-Ivanovic et al., Citation2023). They are more likely to embrace novel technologies, explore different features and functionalities, and exhibit higher levels of innovation adoption (Watjatrakul, Citation2020).

Sub-dimensions of openness such as innovativeness and curiosity are characteristics of openness and have been associated with a greater propensity for adopting new technologies (Kim et al., Citation2020; Lowry et al., Citation2013). Innovativeness reflects consumers’ openness to trying new ideas and products, making them more inclined to embrace technological advancements. Curiosity motivates consumers to seek out new experiences, ask questions, and engage in cognitive exploration (Yang et al., Citation2020). This particular subdimension of openness can drive individuals to adopt new technologies as a means of satisfying their desire for stimulation and novelty (Barnett et al., Citation2015).

Furthermore, extraversion has been found to be a positive predictor of technology adoption (Lee & Kim, Citation2021; Shumanov & Johnson, Citation2021). Individuals who score high on extraversion are more likely to engage with social media platforms. Extraverts tend to be more open to social interaction, oriented to action, assertive and are more likely to engage with technology that facilitates social connections, such as social media platforms and online communication tools. They may also exhibit higher levels of engagement (Flavián et al., Citation2022) and frequency of use in technology-mediated social interactions.

On the other hand, there are contrasting views on the impacts of traits such as agreeableness, and conscientiousness are less aligned with the adoption of new technology (Barnett et al., Citation2015; Shumanov & Johnson, Citation2021) and neuroticism that is mostly reported as having a negative influence on technology adoption (González-González et al., Citation2021). Individuals high in neuroticism tend to be more anxious and risk-averse, are less likely to develop creative behaviours, and unable to easily adjust emotionally to the environment which may hinder their adoption of technologies perceived as unfamiliar or risky (Barnett et al., Citation2015; González-González et al., Citation2021). In addition, neurotic individuals generally prefer to remain in familiar environments and routines, seeking stability and predictability (Flavián et al., Citation2022). New technologies such as VR for tourism, by their nature, introduce change and uncertainty, which can trigger anxiety and discomfort for neurotic individuals (Watjatrakul, Citation2020). This may lead them to resist or delay the adoption of such a new technology in favour of maintaining their familiar routines.

Similarly, individuals high in agreeableness, prioritize social relationships, generally inclined to help others and gain their acceptance (Fanea-Ivanovic et al., Citation2023), may be less inclined to adopt technologies that are viewed as socially disruptive or potentially detrimental to relationships. Because agreeableness is primarily reflecting consumers’ tendency to be compassionate, cooperative, and accommodating towards others (Barnett et al., Citation2015), these traits may not directly influence the adoption of technology, which is more closely related to factors such as usefulness, and performance of the technology.

Likewise, conscientiousness is characterised by the ability to be responsible, punctual, practical, self-disciplined (Tešin et al., Citation2023). In the context of technology adoption, conscientious individuals may approach new technologies with caution and thoroughness. xcvz

Therefore, in linking personality traits to the adoption of VR technology for tourism, this study focuses on extraversion, and two subdimensions of openness including curiosity and innovativeness, which have been repeatedly reported as critical for technology adoption.

Hypothesis development

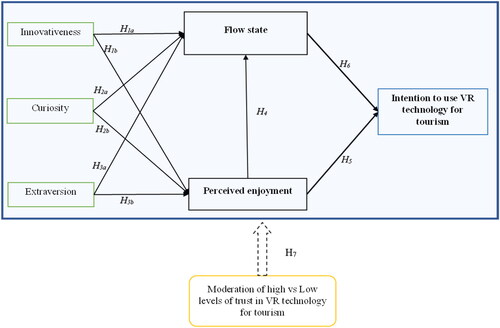

Underpinned by these two theories, the present study proposes a conceptual model depicted in .

Innovativeness and its impact on flow state and enjoyment

Innovativeness refers to individuals’ willingness to adopt or experience a new product or idea and has been used consistently within the realm of technology adoption (Matute-Vallejo & Melero-Polo, Citation2019). Highly innovative consumers are more eager to experiment with novel technology to solve problems (Matute-Vallejo & Melero-Polo, Citation2019) as experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic which promoted the use of technology (Sharma et al., Citation2021). Typically, innovative consumers are more open to new experiences and are more likely to undergo cognitive absorption – a state of deep involvement and engagement –when using technology, so much so that their self-consciousness and acknowledgement of external stimuli are compromised (Matute-Vallejo & Melero-Polo, Citation2019). This level of immersion indicates a correlation between enjoyment and product use, a relationship validated by Lau et al. (Citation2019), who provide empirical evidence to corroborate perceived enjoyment as an antecedent in adopting various technologies.

Furthermore, in a VR adoption study conducted in South Korea, Kim et al. (Citation2020) established that consumers that exhibited high innovativeness are more likely to participate in VR tourism activities. These results are similar to an investigation conducted by Alalwan et al. (Citation2018) on Saudi Arabia consumers in which innovativeness was found to be a significant predictor of customers’ adoption intentions. Additionally, the study supported the notion that highly innovative individuals perceive more hedonic benefits and, subsequently, a higher level of enjoyment from using technology.

Consequently, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1a: Innovativeness has a positive influence on the flow state.

H1b: Innovativeness has a positive influence on perceived enjoyment.

Curiosity and its influence on flow state and perceived enjoyment

Curiosity, as posited by Yang et al. (Citation2020), manifests as an individual’s inherent inclination to seek additional knowledge about a particular subject. This psychological phenomenon has garnered recognition as a pivotal catalyst in shaping human behaviour (Schutte & Malouff, Citation2020). The genesis of curiosity occurs when there is a dissonance between the existing knowledge base and the aspiration to acquire further information (Yang et al., Citation2020). In the context of technological advancements, Yang et al. (Citation2020) assert that novel technologies possess the capability to incite curiosity, subsequently engendering a state of flow. This viewpoint aligns with the observations of Lowry et al. (Citation2013), who, in their exploration of video game engagement, put forth a hedonic-motivation system adoption model where curiosity plays a pivotal role in fostering immersion. While, the influence of curiosity on flow state has not been studied extensively in the context o < f VR technology, Schutte and Malouff’s study (Citation2020) contributes to the analytical framework by./establishing a correlation between heightened levels of curiosity and increased experiences of flow. This empirical connection underscores the nuanced relationship between curiosity and psychological states, highlighting the intricate dynamics that contribute to the motivational and immersive aspects of human engagement. Moreover, it emphasises the need for more extensive investigations in this context.

Interactive virtual reality can trigger an individual’s curiosity for new information, which can evoke pleasant emotions, such as joy and happiness (Israel et al., Citation2019; Schutte & Malouff, Citation2020). The innate desire of curious consumers to acquire knowledge and explore new information drives them to actively seek out novel technological advancements and engage in technology adoption processes. Inasmuch as interactive websites can arouse an individual’s curiosity, adding to the website’s ‘stickiness’ factor and resulting in greater perceived enjoyment (Israel et al., Citation2019; Pelet et al., Citation2017), it is believed that VR technology would achieve the same effect as the contents are more immersive than tourist websites (Vishwakarma et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, Israel et al. (Citation2019) study conducted in Germany provides empirical evidence that curiosity influences perceived enjoyment. Therefore, the following are hypothesised:

H2a: Curiosity has a positive influence on the flow state.

H2b: Curiosity has a positive influence on perceived enjoyment.

Extraversion and its influence on flow state and perceived enjoyment

Extraversion refers to the proclivity to engage with people, be sociable and active, and enjoy interacting and meeting new people (Shumanov & Johnson, Citation2021). This trait manifests in the consumer’s inclination toward novel experiences facilitated by emerging technologies, exemplified by the interest in virtual reality (VR) platforms (Lissitsa & Kol, Citation2021; Shumanov & Johnson, Citation2021). The description of extravert is akin to the profile of innovators and early adopters as they also seek new opportunities (Lissitsa & Kol, Citation2021). Extroverts, who thrive in social settings and seek social stimulation, may be drawn to VR experiences that enable them to connect with others, share their experiences, and engage in virtual social interactions with fellow users or avatars. Therefore, a discernible link emerges between the extraversion nature of consumers and their likelihood to adopt new technology. Evidence from Shumanov and Johnson (Citation2021) substantiates that extroverts have a higher level of engagement in chatbot as they are highly associated with sociability. Similar findings were reported by Lissitsa and Kol (Citation2021) who found a positive relationship between extraversion and m-shopping intention. Moreover, Wang (Citation2010) supports these insights by affirming a positive relationship between extraversion and the desire to experience enjoyment and pleasure when undertaking an activity.

Therefore, it is hypothesised that:

H3a: Extraversion has a positive influence on the flow state.

H3b: Extraversion has a positive influence on perceived enjoyment.

Perceived enjoyment and its impact on perceived flow state and the intention to use VR technology for tourism

When individuals perform passionate activities, their enjoyment or excitement results in them becoming so engrossed and absorbed in the action that it can lead to a flow state (Matute-Vallejo & Melero-Polo, Citation2019). This can be experienced in real and virtual environments (Huang et al., Citation2018), where the fun and enjoyment experienced allows an individual to attain high levels of concentration effortlessly in fulfilling a task (Barta et al., Citation2021; Mahfouz et al., Citation2020). This deep sense of engagement (i.e., flow) depends on an individual engaging in enjoyable and challenging activities (Pelet et al., Citation2017). The enjoyment of completing a difficult task can positively affect one’s mood and enhances engagement and interest, the latter of which is a core element of flow (Mahfouz et al., Citation2020). Previous studies have proven that enjoyment influences the flow state of mobile social media users (Kim et al., Citation2017) and VR gamers (Lowry et al., Citation2013) and online shopping on e-commerce platforms (Barta et al., Citation2021). Consequently, the following hypothesis is stipulated:

H4: Perceived enjoyment has a positive influence on the flow state.

H5: Perceived enjoyment has a positive influence on the intention to use VR technology for tourism.

Perceived flow state and its impact on the intention to use VR technology for tourism

Behavioural intention is identified as a prerequisite of the individual’s actual behaviour (Alalwan et al., Citation2018). The intention symbolises a person’s interest in taking action manifested by a motivation, force, or pattern to participate in a behaviour (Indarsin & Ali, Citation2017). Following the flow theory and aligned with VR adoption for tourism, this motivation is dependent on the various technical and informational attributes of VR technology which act as stimuli in evoking an individual’s internal psychological processing (affective state) and subsequent behavioural response (e.g., intention to use, positive word of mouth, intention to revisit) (An et al., Citation2021; Manis & Choi, Citation2019). While being in a state of flow after engaging in leisure activities often results in higher levels of enjoyment and satisfaction, flow can also evoke negative feelings and emotions, particularly when an individual regret the time and money spent doing an activity (e.g., playing video games, or gambling). However, these outcomes are contextual, and with travel and tourism activities generally associated with fun and enjoyment, it is believed that flow is expected to result in a positive evaluation of the VR experience (An et al., Citation2021). A previous study conducted by An et al. (Citation2021) which focused on the virtual travel experience and destination marketing, investigated the effect of flow on visitor intention and found that flow within virtual travel led to increased satisfaction and visit intention. This influence of flow state on the intention to adopt technology for tourism is supported and validated by Kim and Hall (Citation2019), Fan et al. (Citation2022) and Zhou (Citation2012) in various contexts. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H6: Flow state has a positive influence on the intention to use VR Technology for tourism.

Moderating effect of trust

Trust is defined as one party’s belief in another having a high level of ability, integrity, and benevolence (Zhou et al., Citation2018). It is recognised as a central component in consumers’ decision to adopt new technology (Belanche et al., Citation2012) by reducing uncertainties and perceived risk (Zhou et al., Citation2018) and, in turn, strengthening relationships between two parties (Issock Issock et al., Citation2020). While Zhou et al. (Citation2018) recognise trust as a predictor of online purchase and repurchase intention, Alsaad et al. (Citation2017) express that conditional or contextual variables are more relevant as moderating factors. Therefore, incorporating variables such as trust as a moderator is appropriate given that its role as a behavioural motivator is not well established (Alsaad et al., Citation2017). This is especially true with studies evaluating the adoption of VR technology in tourism. Moreover, although trust is critical to virtual interactions, the paucity of literature on its role as a moderator in VR technology adoption studies warrants further enquiry.

Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H7: The level of trust moderates the intention to use VR technology for tourism.

Research methodology

Research context and sampling design

This study follows a quantitative method using a cross-sectional design to test the proposed conceptual model and validate the hypotheses developed in this study. The target population consisted of millennial travellers residing in South Africa who have some touristic experience as they have travelled locally (inbound) or internationally (outbound) for tourism purposes in the past three years. The choice of millennials for this study is based on their proclivity to be early adopters and are, therefore, likely to disrupt the tourism industry through the adoption of new technologies such as VR (da Silva deMatos et al., Citation2021).

In the absence of an exhaustive sampling frame encompassing all millennial travellers, this study employed purposive sampling, a non-probability technique. To ensure the rigorous selection of participants, the study confined the sample to respondents born between 1981 and 1997, who have experienced touristic activities in the past three years. Screening questions were integrated to ascertain the participants’ travel history, both domestically and internationally.

Prior to completion, informed written consent was obtained from all participants in the study. The fieldwork was executed by trained personnel from a reputable South African-based data collection agency. An online questionnaire was designed on Survey Monkey. The questionnaire link was disseminated to suitable panel members within the company’s database, with fieldworkers overseeing the process to guarantee that only eligible respondents completed the survey. Given the relatively limited familiarity with VR technology in South Africa (Woyo & Nyamandi, Citation2022), extra measures were taken to ensure respondents’ comprehension of VR and its applications in tourism. As such, the online questionnaire featured visual aids, including images illustrating the utilization of VR technology for tourist experiences. For instance, these visual aids portrayed tourists donning head-mounted displays while immersing themselves in various tourist attractions. Following these visual cues, a detailed description of how VR technology enhances tourism experiences was provided.

A total of 400 questionnaires were completed during data collection. After rigorous data screening and cleaning procedures, including the exclusion of participants lacking recent tourism experiences and those with inadequately completed questionnaires, 361 valid responses remained for subsequent data analysis. This sample size adheres to the recommended measurement item-to-sample size ratio of 10 as advocated by Hair et al. (Citation2019).

The sample consisted mostly of female respondents (66%). Most respondents (81%) were aged between 25 and 34 years old and had a degree (63%). A high proportion (46%) of respondents earn between 11700 EURO and 23600 EURO annually. More than half of the sample reported being single (unmarried). Ethical clearance was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee (Non-Medical) at the University of one of the authors in line with the ethical requirements. The ethical clearance number for the study is H21/06/33.

Measurement and data analysis

In this study, we employed a set of thirty measurement items to assess the eight constructs outlined in the proposed model. To ensure the reliability and validity of the scale, the statements used for measuring these constructs were adapted from well-established studies (Kim et al., Citation2020; Kim & Hall, Citation2019; Lee & Kim, Citation2021; Lowry et al., Citation2013; Slade et al., Citation2015). A comprehensive breakdown of how these measurement items were phrased to assess each construct, along with the relevant sources, are presented in . All constructs were evaluated using five-point Likert scales, where respondents could express their agreement on a scale ranging from ‘Strongly Disagree’ (1) to ‘Strongly Agree’ (5).

Table 1. Assessment of the reliability and convergent validity.

To analyse the profile of respondents and central tendency measures of constructs, descriptive statistical analyses such as frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation were calculated on IBM SPSS version 28. The proposed model was tested through structural equation modelling (SEM) using a covariance-based package, IBM AMOS version 28. These proprietary research instruments were obtained through a copyright license. The SEM is deemed appropriate to test a model with multiple dependent variables because it combines robust multivariate data analysis techniques such as factor analysis, correlation, and regression (Hair et al., Citation2019). Moreover, the moderation of trust is analysed through the multi-group analysis using an invariant test on AMOS version 28.

Results and findings

Before testing the measurement and structural models, the common method variance was assessed given that the data was retrieved from a single source, respondents were requested to rate the scale at once, and it was a self-reported survey. Following (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003) recommendation, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted. Therefore, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) including all the item measures in the model was performed on SPSS version 28. The single factor (EFA) results revealed that all the factors explained only 39.4% of the variance of the single factor, which is below the 50% cut-off (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). There is therefore no issue of common method bias. Moreover, to confirm normalcy, by examining the skewness and kurtosis values presented in . The values are within the recommended limits of | 2 | (George & Mallery, Citation2010) for all variables, indicating that the data does not alarmingly deviate from normality.

Measurement model assessment

The measurement model was assessed using a covariance-based approach on IBM AMOS version 28, and the results are presented in . All model fit indices meet the required threshold (Hair et al., Citation2019). To assess the reliability of the constructs, internal consistency measures such as Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) are presented in . These measures demonstrate that all constructs are reliable, as their values exceed 0.7 (Hair et al., Citation2019). Convergent validity of the constructs is confirmed by examining factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE), both shown in . All factor loadings and AVE values are above the cut-off of 0.5, providing evidence of convergent validity.

presents the inter-construct correlation matrix, providing evidence of discriminant validity. Following Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981), the square root of the AVEs is higher than the inter-construct correlation coefficients, supporting discriminant validity. Therefore, the measurement model demonstrates both convergent and discriminant validity, ensuring the robustness of the scales used in this study.

Table 2. Assessment of discriminant validity.

Structural model

The structural model’s key fit indices, as presented in , align well within the established thresholds. The outcomes of the analysis reveal that perceived enjoyment is significantly influenced by innovativeness (β = 0.216; p < 0.001) and curiosity (β = 0.664; p < 0.001), while no significant impact is observed from extraversion (p > 0.05). Regarding the flow state, while innovativeness shows no notable influence (p > 0.05), the results underscore the dominant role of perceived enjoyment (β = 0.534; p < 0.001). Additionally, curiosity exhibits a moderate impact (β = 0.317; p < 0.01), whereas extraversion demonstrates a negative yet significant influence (β= -0.200; p < 0.01). The structural model effectively accounts for approximately 59% of the variance in the intention to adopt VR technology, primarily driven by the robust impact of perceived enjoyment (β = 0.617; p < 0.001) and the moderate effect of the flow state (β = 0.183; p < 0.05). Consequently, this analysis substantiates the acceptance of hypotheses H1b, H2b, H2a, H3a, H4a, H5, H6, and H7, while hypotheses H1a, H3a, H3b, H4b, are refuted.

Table 3. Structural model estimates.

Moderating effect of trust using a multi-group analysis

The structural invariance test using a metric invariance test, the chi-square test of difference, was applied to test the moderating effect of consumer trust on the structural paths. First, the sample was divided into two sub-samples of respondents with high levels of trust (n1 =222; 61.5%) and low levels of trust (n2= 139; 38.5%) by employing a median split procedure (Kautish et al., Citation2019). The median of trust being equal to 4, respondents with a trust score equal to or below the median were considered low, while respondents with a trust score above the median were deemed high.

Fully constrained and unconstrained models were compared across the two sub-samples of high and low trust to ascertain the invariance. Using the function multi-group analysis on AMOS version 28, the model was not significantly different across the two groups (X2= 58.1; DF= 201; p = 1.00 > 0.05; ΔTLI= -0.006; ΔNFI= -0.010). This means that the overall model does not differ across the samples with low and high levels of trust. However, a close look at the regression estimates between the two samples indicate that there are some paths that significantly differ across the level of trust as describe in . Therefore, to understand the moderating effect of trust on each structural path in the model, the paths were sequentially constrained and compared across the two sub-samples.

Table 4. Moderating effect of trust on each structural path.

The path by path presented in revealed that consumer trust significantly moderates three relationships in the model: (1) the impact of curiosity on perceived enjoyment which is positive and significant for consumer with high level of trust (β = 0.749; p < 0.001) and non-significant for those with low trust (p > 0.05); (2) The influence of perceived enjoyment on flow state is statistically significant for consumer with high level of trust (β = 0.799; p < 0.05) while those with low trust had a non-significant relationship (p > 0.05). (3) Similar results are reported for the path between perceived enjoyment and intention where the relationship is significant for consumers with high level of trust (β = 0.729; p < 0.001) while being non-significant for the those with low level of trust (p > 0.05).

General discussion

The conceptual framework underpinning our study offers insightful findings on the dynamics around the adoption of VR technology for tourism. The model reveals the multifaceted influence of various factors, shedding light on the nuanced interplay among perceived enjoyment, flow state, personality traits, and the moderating role of trust.

The findings underscore that perceived enjoyment, a critical facet of the consumer experience, is positively influenced by both innovativeness and curiosity. Remarkably, curiosity emerges as the dominant predictor, aligning with Israel et al. (Citation2019) earlier research that highlighted how satisfying curiosity through novel technology leads to enhanced enjoyment. In contrast, the impact of extraversion on perceived enjoyment which result is inconsistent with previous studies by Wang (Citation2010) and Manis and Choi (Citation2019). This finding therefore suggests that tourists’ enjoyment of VR technology has nothing to do with their proclivity to extraversion.

Delving deeper, the examination of the flow state unveils its determinants. Curiosity and perceived enjoyment exert positive influences, with perceived enjoyment exhibiting a notably stronger impact. This substantial influence of perceived enjoyment aligns with the nature of the flow state as an embodiment of pleasurable experiences when engaging with VR technology for tourism (Mahfouz et al., Citation2020). Our results harmoniously echo Yang et al. (Citation2020) findings that novel technology triggers curiosity and thereby cultivates the flow experience. Intriguingly, the findings introduce an unexpected dimension, showcasing the role of technology costs in shaping the flow state—an insight congruent with Pelet et al. (Citation2017) observations of flow experiences within new technology contexts. Unexpectedly, the extroverted nature of consumers emerges as a possible hindrance to the flow state. This intriguing result diverges from the conclusions drawn by Moon et al. (Citation2014), where extroversion facilitated the flow state. Moreover, the non-significance of the impact of innovativeness on the flow state, contrary to prior research by Zhou (Citation2012), adds further layers to the understanding of how personality traits interact with flow experiences in the context of VR adoption for tourism.

Transitioning to the influences of intention to adopt VR technology for tourism, the results highlight the pivotal roles of perceived enjoyment and the flow state. This finding echoes similar observations by Vishwakarma et al. (Citation2020), Lee and Kim (Citation2021), and Fan et al. (Citation2022), who affirm the transformative influence of heightened flow state and perceived enjoyment on consumer intentions towards VR technology adoption for tourism. Notably, perceived enjoyment emerges as a dominant force, its impact exceeding that of the flow state, and thus affirming the centrality of enjoyable experiences in stimulating the intention to adopt VR technology for tourism.

Diving deeper into the moderating role, our exploration reveals some interesting insights. In the context of VR technology adoption for tourism, consumer trust takes on heightened significance, particularly resonating within the emerging landscape of South African tourism where the adoption of VR is still burgeoning (Woyo & Nyamandi, Citation2022). Our findings demonstrate that trust moderates some of the relationships in the model. Specifically, the influence of curiosity on perceived enjoyment, along with the impact of perceived enjoyment on both the flow state and intention to adopt VR significantly vary across consumers that have high and low levels of trust. This observation emphasises that trust in VR technology acts as an amplifier, intensifying positive emotional responses and ultimately experiencing a more gratifying engagement.

Implications and conclusion

Theoretical implications

Our study advances the understanding of VR technology adoption for tourism by integrating personality traits, flow theory, and the moderating role of trust. Departing from predominant technology adoption frameworks such as the TAM, our conceptual framework offers a unique lens to decipher the mechanism driving consumers’ intention to adopt VR technology for tourism. Our proposed model provides empirical evidence on the impact of combined internal stimuli (personality traits) on intermediary affective states (perceived enjoyment and flow state) and how these states affect the intention to adopt VR for tourism. Identifying curiosity as a pivotal trait in VR technology adoption resonates with Israel et al. (Citation2019) insights and further highlights the context-specific importance of this trait in the tourism domain. Moreover, in response to the call by da Silva deMatos et al. (Citation2021) for more exploration of flow experiences within the realm of technology adoption for tourism, our research extends the theoretical discussion surrounding flow experiences. Our findings revealed that central to adopting VR technology for tourism is the desire to be immersed in a flow state and, more importantly, enjoy the experience. These two affective states proved to be impactful in forming consumers’ intention to use VR technology for tourism.

The present study has taken a step toward understanding the importance of enjoyment when consumers engage in touristic activities through VR technology. Our findings demonstrate that perceived enjoyment has a positive and the strongest impact on flow state and intention. Moreover, by adding the flow state to the proposed model, this study captured consumers’ mental state when completely immersed in the VR environment (Kim & Ko, Citation2019). This research adds to the current literature on VR technology by combining two relevant intermediary affective states that particularly echo expected experiences when engaging in touristic activities (Ying et al., Citation2022).

Furthermore, as VR technology is progressively gaining currency in the tourism industry, investigating the role of trust sheds important light on the process leading to consumers’ adoption of technology for tourism. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the literature on VR technology for tourism has paid little attention to the moderating role of trust. Our findings point to the fact that trust may certainly be an important moderator in strengthening the impact of perceived enjoyment on flow state and intention to adopt VR technology for tourism.

Practical implications

From a practical standpoint, this study offers destination marketers a valuable resource by presenting empirical insights into the activation of specific personality traits and intermediary affective states that influence consumers’ intention to adopt VR technology for tourism. For a strategic touristic destination such as South Africa, renowned in the African continent for its exotic attractions such as Table Mountain and the Kruger National Park (Giampiccoli et al., Citation2015; Mokoena, Citation2020), this study’s findings hold relevance. Considering the potential limitations of travel for some individuals, VR technology becomes a powerful tool for bringing these attractions closer to a wider audience. Through the enhancement of users’ experiences, destination marketers can cultivate satisfied and loyal customers, thereby enhancing the overall reputation.

This study provides a deeper understanding of the diverse range of personality traits that influence VR technology adoption for tourism. This knowledge can be harnessed to craft highly targeted and personalized marketing strategies. By tailoring messages and experiences to align with specific personality traits, marketers can effectively resonate with individual preferences, ultimately driving higher engagement and adoption rates. Allocating resources to create seamless, captivating, and immersive VR experiences that align with users’ personality and affective states can significantly enhance visitor satisfaction and positive word-of-mouth.

Moreover, the present study sheds light on the centrality of enjoyment and the need to provide travellers with a VR platform where they will be completely absorbed by the experience and be in a flow state. Consumers are willing to engage in touristic activities through VR only if they experience these sensations of immersion in activities and loss of their sense of time (An et al., Citation2021). Effective deployment of VR technology in the tourism sector involves crafting multisensory experiences, including high-quality audio, authentic visuals, enticing scents, and enhanced tactile sensations, creating an environment that transcends the physical surroundings. In addition, destination marketers and touristic agencies should focus their communication about VR technology on the consumers’ desire to satiate their curiosity, extraversion, and thirst for innovation through new VR technology. The marketing messages should also emphasise the benefits of lower transactional costs when using VR for tourism.

Another contribution to practice would be related to tourism education. The results of this study can be used by tourism academic institutions and schools or destination marketing agencies in developing VR tourism training programmes for employees or students studying tourism-related qualifications. VR can assist in overcoming the intangibility aspect of tourism (Lee & Kim, Citation2021), developing virtual tourism experiences for employees and students that result in enjoyment and a state of flow. All these benefits can provide training institutions with more satisfied customers/students and a distinct competitive advantage. In addition, destination marketing agencies can benefit by having knowledgeable employees on tourism destinations and experiences.

Limitations and avenues for future research

This study acknowledges several limitations that warrant consideration for future research. Firstly, the survey primarily investigated behavioural intention rather than the actual adoption of VR technology. Given that South Africa’s VR technology adoption is still in its nascent stages compared to more developed countries (Woyo & Nyamandi, Citation2022), future investigations should target the few existing VR technology users to gauge the true adoption rate for tourism purposes. In such cases, the model could be expanded to encompass experiential constructs such as customer engagement, customer satisfaction, or customer experience, providing a more comprehensive understanding. Furthermore, future studies could focus on additional affective states derived from VR technology such as happiness, pleasure, and excitement. Secondly, this study relies on self-reported data, which may introduce potential biases. To mitigate this, future research could explore more direct research strategies, such as experimental designs or observational methods, to complement self-reported findings and enhance its robustness. Lastly, the study’s scope is confined to South African tourists engaged in either local or international tourism. Future studies should broaden the horizons by encompassing tourists from diverse countries to offer a more nuanced perspective. By transcending geographical boundaries, researchers can generate a more comprehensive understanding of how VR technology adoption manifests in diverse cultural contexts.

Author contribution

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows:

Study conception and design – Paul Blaise Issock Issock, Abby Jacobs

Data collection – Abby Jacobs

Data Analysis – Paul Blaise Issock Issock, Abby Jacobs

Writing of the manuscript – Paul Blaise Issock Issock, Abby Jacobs, Aaron Koopman

Revision of the manuscript - Paul Blaise Issock Issock, Aaron Koopman

Final approval of the manuscript – Paul Blaise Issock Issock, Aaron Koopman

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s)

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [AK], upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Paul Blaise Issock Issock

Paul Blaise Issock Issock (PhD) is a Senior researcher at the University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. His research interests include transformative consumer research, sustainable tourism, social marketing, corporate social responsibility and sustainable marketing.

Abby Jacobs

Abby Jacobs is the Acting Head of North Europe Hub (Netherlands, Belgium, Sweden) at South African Tourism. She is also a researcher and a DBA candidate affiliated with the University of the Witwatersrand. Her research interests include destination marketing, technology usage and tourism.

Aaron Koopman

Aaron Koopman is a lecturer and emerging researcher in the Marketing Department within the School of Business Sciences at the University of the Witwatersrand. He is currently pursuing his PhD in Marketing at the University of the Witwatersrand within the broad field of brand management. Aaron’s other research interests include consumer behaviour, marketing communications, and contemporary issues in marketing.

References

- Alalwan, A. A., Baabdullah, A. M., Rana, N. P., Tamilmani, K., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2018). Examining adoption of mobile internet in Saudi Arabia: Extending TAM with perceived enjoyment, innovativeness and trust. Technology in Society, 55(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2018.06.007

- Alsaad, A., Mohamad, R., & Ismail, N. A. (2017). The moderating role of trust in business to business electronic commerce (B2B EC) adoption. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 157–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.040

- An, S., Choi, Y., & Lee, C.-K. (2021). Virtual travel experience and destination marketing: Effects of sense and information quality on flow and visit intention. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100492

- Barnett, T., Pearson, A. W., Pearson, R., & Kellermanns, F. W. (2015). Five-factor model personality traits as predictors of perceived and actual usage of technology. European Journal of Information Systems, 24(4), 374–390. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2014.10

- Barta, S., Flavián, C., & Gurrea, R. (2021). Managing consumer experience and online flow: Differences in handheld devices vs PCs. Technology in Society, 64, 101525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101525

- Belanche, D., Casaló, L. V., & Flavián, C. (2012). Integrating trust and personal values into the, Technology Acceptance Model: The case of e-government services adoption. Cuadernos de Economía y Dirección de la Empresa, 15(4), 192–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cede.2012.04.004

- Chang, H. H., & Chiang, C. C. (2022). Is virtual reality technology an effective tool for tourism destination marketing? A flow perspective. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 13(3), 427–440. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-03-2021-0076

- Chang, Y., Ko, Y. J., & Jang, W. (. (2019). Personality determinants of consumption of premium seats in sports stadiums. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(8), 3395–3414. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2018-0759

- Chen, C., Zhang, K. Z., Gong, X., Zhao, S. J., Lee, M. K., & Liang, L. (2017). Understanding compulsive smartphone use: An empirical test of a flow-based model. International Journal of Information Management, 37(5), 438–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2017.04.009

- Chittaranjan, G., Blom, J., & Gatica-Perez, D. (2011). Who’s who with big-five: Analyzing and classifying personality traits with smartphones. In 2011 15th Annual international symposium on wearable computers, 29–36.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., Latter, P., & Weinkauff Duranso, C. (2017). Running flow. Human Kinetics.

- da Silva deMatos, N. M., de Sa, E. S., & de Oliveira Duarte, P. A. (2021). A review and extension of the flow experience concept. Insights and directions for Tourism research. Tourism Management Perspectives, 38, 100802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100802

- Fan, X., Jiang, X., & Deng, N. (2022). Immersive technology: A meta-analysis of augmented/virtual reality applications and their impact on tourism experience. Tourism Management, 91, 104534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104534

- Fanea-Ivanovici, M., Baber, H., Salem, I. E., & Pana, M. C. (2023). What do you value based on who you are? Big five personality traits, destination value and electronic word-of-mouth intentions. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 2023, 14673584231191317. https://doi.org/10.1177/14673584231191317

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Flavián, C., Guinalíu, M., & Jordán, P. (2022). Virtual teams are here to stay: How personality traits, virtuality and leader gender impact trust in the leader and team commitment. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 28(2), 100193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2021.100193

- Flavián, C., Ibáñez-Sánchez, S., & Orús, C. (2021). Impacts of technological embodiment through virtual reality on potential guests’ emotions and engagement. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 30(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2020.1770146

- Gao, L., Bai, X., & Park, A. (2017). Understanding sustained participation in virtual travel communities from the perspectives of is success model and flow theory. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 41(4), 475–509. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348014563397

- George, D., & Mallery, M. (2010). SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 17.0 update. (10a ed.) Pearson.

- Giampiccoli, A., Lee, S. S., & Nauright, J. (2015). Destination South Africa: Comparing global sports mega-events and recurring localised sports events in South Africa for tourism and economic development. Current Issues in Tourism, 18(3), 229–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.787050

- González-González, T., García-Almeida, D. J., & Viseu, J. (2021). Frontline employee-driven change in hospitality firms: An analysis of receptionists’ personality on implemented suggestions. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(12), 4439–4459. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2021-0645

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis. Cengage Learning.

- Hamari, J., Shernoff, D. J., Rowe, E., Coller, B., Asbell-Clarke, J., & Edwards, T. (2016). Challenging games help students learn: An empirical study on engagement, flow and immersion in game-based learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 170–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.045

- Han, D. D., Tom Dieck, M. C., & Jung, T. (2019). Augmented Reality Smart Glasses (ARSG) visitor adoption in cultural tourism. Leisure Studies, 38(5), 618–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2019.1604790

- Huang, Y. C. (2023). Integrated concepts of the UTAUT and TPB in virtual reality behavioral intention. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 70, 103127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103127

- Huang, Y. C., Backman, K. F., Backman, S. J., & Chang, L. L. (2016). Exploring the implications of virtual reality technology in tourism marketing: An integrated research framework. International Journal of Tourism Research, 18(2), 116–128. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2038

- Huang, A., Chao, Y., de la Mora Velasco, E., Bilgihan, A., & Wei, W. (2021). When artificial intelligence meets the hospitality and tourism industry: an assessment framework to inform theory and management. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 5(5), 1080–1100. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-01-2021-0021

- Huang, H.-C., Pham, T. T. L., Wong, M.-K., Chiu, H.-Y., Yang, Y.-H., & Teng, C.-I. (2018). How to create flow experience in exergames? Perspective of flow theory. Telematics and Informatics, 35(5), 1288–1296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2018.03.001

- Huotari, K., & Hamari, J. (2017). A definition for gamification: anchoring gamification in the service marketing literature. Electronic Markets, 27(1), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-015-0212-z

- Indarsin, T., & Ali, H. (2017). Attitude toward using m-commerce: The analysis of perceived usefulness perceived ease of use, and perceived trust: Case study in Ikens Wholesale Trade, Jakarta–Indonesia. Saudi Journal of Business and Management Studies, 2(11), 995–1007.

- Israel, K., Zerres, C., & Tscheulin, D. K. (2019). Presenting hotels in virtual reality: Does it influence the booking intention? Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 10(3), 443–463. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-03-2018-0020

- Issock Issock, P. B., Roberts-Lombard, M., & Mpinganjira, M. (2020). The importance of customer trust for social marketing interventions: a case of energy-efficiency consumption. Journal of Social Marketing, 10(2), 265–286. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSOCM-05-2019-0071

- Jackson, S. A., & Marsh, H. W. (1996). Development and validation of a scale to measure optimal experience: The Flow State Scale. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 18(1), 17–35. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.18.1.17

- Jamshidi, D., Keshavarz, Y., Kazemi, F., & Mohammadian, M. (2018). Mobile banking behavior and flow experience: An integration of utilitarian features, hedonic features and trust. International Journal of Social Economics, 45(1), 57–81. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-10-2016-0283

- Jani, D. (2014). Relating travel personality to Big Five Factors of personality. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 62(4), 347–359.

- Kautish, P., Paul, J., & Sharma, R. (2019). The moderating influence of environmental consciousness and recycling intentions on green purchase behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production, 228, 1425–1436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.389

- Kim, D., & Ko, Y. J. (2019). The impact of virtual reality (VR) technology on sport spectators’ flow experience and satisfaction. Computers in Human Behavior, 93, 346–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.12.040

- Kim, M. J., & Hall, C. M. (2019). A hedonic model in virtual reality tourism: comparing visitors and non-visitors. International Journal of Information Management, 46, 236–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.11.016

- Kim, M. J., Lee, C. K., & Bonn, M. (2017). Obtaining a better understanding about travel-related purchase intentions among senior users of mobile social network sites. International Journal of Information Management, 37(5), 484–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2017.04.006

- Kim, M. J., Lee, C.-K., & Preis, M. W. (2020). The impact of innovation and gratification on authentic experience, subjective well-being, and behavioral intention in tourism virtual reality: The moderating role of technology readiness. Telematics and Informatics, 49, 101349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2020.101349

- Kranjčev, M., & Hlupić, T. V. (2021). Personality, anxiety, and cognitive failures as predictors of flow proneness. Personality and Individual Differences, 179, 110888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110888

- Lau, C. K., Chui, C. F. R., & Au, N. (2019). Examination of the adoption of augmented reality: a VAM approach. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 24(10), 1005–1020. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2019.1655076

- Lee, W., & Kim, Y. H. (2021). Does VR tourism enhance users’ experience? Sustainability, 13(2), 806. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020806

- Lissitsa, S., & Kol, O. (2021). Four generational cohorts and hedonic m-shopping: Association between personality traits and purchase intention. Electronic Commerce Research, 21(2), 545–570. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-019-09381-4

- Lowry, P. B., Gaskin, J., Twyman, N., Hammer, B., & Roberts, T. (2013). Taking ‘fun and games’ seriously: Proposing the hedonic-motivation system adoption model (HMSAM). Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 14(11), 617–671. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00347

- Mahfouz, A. Y., Joonas, K., & Opara, E. U. (2020). An overview of and factor analytic approach to flow theory in online contexts. Technology in Society, 61, 101228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101228

- Manis, K. T., & Choi, D. (2019). The virtual reality hardware acceptance model (VR-HAM): Extending and individuating the technology acceptance model (TAM) for virtual reality hardware. Journal of Business Research, 100, 503–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.10.021

- Matute-Vallejo, J., & Melero-Polo, I. (2019). Understanding online business simulation games: The role of flow experience, perceived enjoyment and personal innovativeness. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 35(3), 71–85. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.3862

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1987). Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81

- Mokoena, L. G. (2020). Cultural tourism: Cultural presentation at the Basotho cultural village, Free State, South Africa. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 18(4), 470–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2019.1609488

- Moon, Y. J., Kim, W. G., & Armstrong, D. J. (2014). Exploring neuroticism and extraversion in flow and user generated content consumption. Information & Management, 51(3), 347–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2014.02.004

- Pelet, J.-É., Ettis, S., & Cowart, K. (2017). Optimal experience of flow enhanced by telepresence: Evidence from social media use. Information & Management, 54(1), 115–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2016.05.001

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Sánchez, M. R., Palos-Sánchez, P. R., & Velicia-Martin, F. (2021). Eco-friendly performance as a determining factor of the Adoption of Virtual Reality Applications in National Parks. The Science of the Total Environment, 798, 148990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148990

- Schutte, N. S., & Malouff, J. M. (2020). Connections between curiosity, flow and creativity. Personality and Individual Differences, 152, 109555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109555

- Sharma, G. D., Thomas, A., & Paul, J. (2021). Reviving tourism industry post-COVID-19: A resilience-based framework. Tourism Management Perspectives, 37, 100786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100786

- Shumanov, M., & Johnson, L. (2021). Making conversations with chatbots more personalised. Computers in Human Behavior, 117, 106627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106627

- Slade, E. L., Dwivedi, Y. K., Piercy, N. C., & Williams, M. D. (2015). Modeling consumers’ adoption intentions of remote mobile payments in the United Kingdom: extending UTAUT with innovativeness, risk, and trust. Psychology & Marketing, 32(8), 860–873. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20823

- South African Tourism. (2022). South African Tourism Annual Report. Retrieved from https://nationalgovernment.co.za/entity_annual/3210/2022-south-african-tourism-annual-report.pdf

- Srivastava, D. K., Kumar, V., Ekren, B. Y., Upadhyay, A., Tyagi, M., & Kumari, A. (2022). Adopting Industry 4.0 by leveraging organisational factors. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 176, 121439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121439

- Talukdar, N., & Yu, S. (2021). Breaking the psychological distance: the effect of immersive virtual reality on perceived novelty and user satisfaction. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2021.1967428

- Tešin, A., Kovačić, S., & Obradović, S. (2023). The experience I will remember: The role of tourist personality, motivation, and destination personality. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 135676672311647. https://doi.org/10.1177/13567667231164768

- Vishwakarma, P., Mukherjee, S., & Datta, B. (2020). Travelers’ intention to adopt virtual reality: A consumer value perspective. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 17, 100456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100456

- Wang, W. (2010). How personality affects continuance intention: An empirical investigation of instant messaging.

- Watjatrakul, B. (2020). Intention to adopt online learning: The effects of perceived value and moderating roles of personality traits. The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 37(1/2), 46–65. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-03-2019-0040

- Whittaker, L., Mulcahy, R., & Russell-Bennett, R. (2021). Go with the flow’for gamification and sustainability marketing. International Journal of Information Management, 61, 102305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102305

- Woyo, E., & Nyamandi, C. (2022). Application of virtual reality technologies in the comrades’ marathon as a response to COVID-19 pandemic. Development Southern Africa, 39(1), 20–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2021.1911788

- Wu, L., Chen, K. W., & Chiu, M. L. (2016). Defining key drivers of online impulse purchasing: A perspective of both impulse shoppers and system users. International Journal of Information Management, 36(3), 284–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2015.11.015

- Yang, S., Carlson, J. R., & Chen, S. (2020). How augmented reality affects advertising effectiveness: The mediating effects of curiosity and attention toward the ad. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 54, 102020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.102020

- Ying, T., Tang, J., Ye, S., Tan, X., & Wei, W. (2022). Virtual reality in destination marketing: telepresence, social presence, and tourists’ visit intentions. Journal of Travel Research, 61(8), 1738–1756. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875211047273

- Yung, R., & Khoo-Lattimore, C. (2019). New realities: A systematic literature review on virtual reality and augmented reality in tourism research. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(17), 2056–2081. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1417359

- Yung, R., Khoo-Lattimore, C., & Potter, L. E. (2021). VR the world: Experimenting with emotion and presence for tourism marketing. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 46, 160–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.11.009

- Zeng, Y., Liu, L., & Xu, R. (2022). The effects of a virtual reality tourism experience on tourist’s cultural dissemination behavior. Tourism and Hospitality, 3(1), 314–329. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3010021

- Zhou, T. (2012). Examining mobile banking user adoption from the perspectives of trust and flow experience. Information Technology and Management, 13(1), 27–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10799-011-0111-8

- Zhou, W., Tsiga, Z., Li, B., Zheng, S., & Jiang, S. (2018). What influence users’ e-finance continuance intention? The moderating role of trust. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 118(8), 1647–1670. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-12-2017-0602