?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

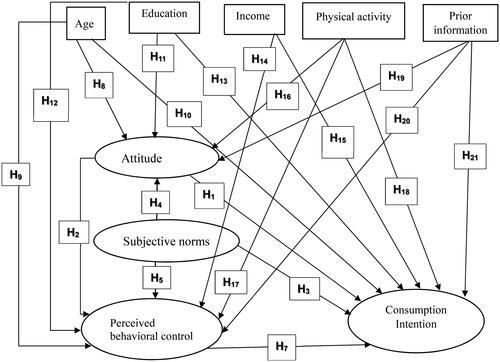

This study aimed to understand the intentions of consumers living in urban areas of Ethiopia to consume Spirulina-fortified bread. Data were collected from a sample of 361 randomly selected respondents. The theory of planned behavior (TPB), with the addition of individual lifestyle characteristics, was applied as a theoretical framework. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM) were employed to test the hypothesized relationships between the variables. The findings revealed that perceived behavioral control and attitude had a significant direct effect on consumption intention, mediating the relationship between subjective norms and consumption intention. Prior information about Spirulina and physical exercise positively influences attitude, perceived behavior, and intention. Age directly and indirectly influences attitude and perceived behavior, respectively. Education directly and indirectly influences perceived behavior and intention, respectively. As this supplement is new to many consumers, promoting Spirulina’s benefits in bread could effectively influence consumer attitudes toward this new supplement.

1. Introduction

Spirulina (Arthrospira platensis) is a microscopic and filamentous cyanobacterium named for the spiral or helical nature of its filaments (Karkos et al., Citation2011). It has a long history of use as food, and there are reports of its utilization dating back to the Aztec civilization (Dillon et al., Citation1995). Spirulina is one of the most nutritious dietary supplements that has come into the spotlight as a sustainable source of protein and vitamin A to improve human nutrition (Wang et al., Citation2021). It is considered safe for consumption due to its beneficial components such as phycocyanin, β-carotene, xanthophyll pigments, α-tocopherol, and phenolic compounds (Hussein et al., Citation2023). Spirulina contains high levels of macronutrients, with approximately 55%–69% proteins, micronutrients, and antioxidants (Campanella et al., Citation1998). It is becoming a popular dietary supplement incorporated into various foods to create functional foods.Footnote1 The use of such alternative resources is important to ensure the sustainable development of food production systems and to meet the growing global protein demand (Röös et al., Citation2017).

In the era of population explosion, dietary transformation, and climate change, promoting optimal nutrition, health, and sustainable food systems is crucial. Spirulina is among the sources that aid in manufacturing, processing, and distributing a broad spectrum of nutrients to enhance human health. This marine alga presents an opportunity to improve food security while benefiting the environment by requiring less soil for protein and energy production compared to livestock. This aligns with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 14, which emphasizes the use of marine resources for sustainable development (Pal & Bose, Citation2022). Spirulina is not only used for consumption but is also increasingly being implemented for sustainable agriculture, contributing to plant growth and yield improvement (Arahou et al., Citation2023). This highlights the broader applicability of Spirulina in sustainable food production systems.

General economic growth is often insufficient to eradicate poverty and hunger. The primary approach to breaking the cycle of poverty and hunger by 2030 requires targeted, cost-effective food sources, such as algae (Olabi et al., Citation2023), particularly microalgae like Spirulina. Addressing hunger-related issues, including underweight, malnutrition, and mortality, especially in children from developing countries, involves focusing on agricultural productivity and nutrition-related treatments. According to Anyanwu et al. (Citation2018), microalgae productivity can be up to 20 times that of traditional oilseed crops on a per-hectare basis, making it a more viable and sustainable alternative. Given the remarkable nutritional benefits of Spirulina, it is recommended for governments to evaluate this microalga as a sustainable food source to provide stability and reduce hunger in economically challenged regions (Olabi et al., Citation2023).

Spirulina can make a significant contribution to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by promoting a healthy lifestyle for future generations. Integrating microalgae, like Spirulina, into SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), can offer at least three key benefits for people: they can cultivate, harvest, and prepare their own food without the need for expensive equipment, fresh water, or complex procedures. Moreover, selling their microalgae products can generate income, presenting a strategic role in reducing hunger and poverty (Olabi et al., Citation2023). Additionally, since Spirulina contains essential nutritional components, providing a balanced diet rich in antioxidants, vitamins, minerals, and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) (Koyande et al., Citation2019), it contributes to achieving SDG 3, promoting good health and well-being. The exploitation and cultivation of algae, such as Spirulina, can also be connected to other SDGs, either directly or indirectly, highlighting the broader significance of such nutrient-dense microalgae.

One of the major factors contributing to the underutilization or complete lack of utilization of Spirulina for human nutrition, which could help alleviate current hunger and poverty situations, is the poor awareness or total lack of awareness of the nutritional content of Spirulina. Countries located within tropical Latin America, the Caribbean, and most of Africa typically ignore seaweeds as a food source, with limited to no cultivation systems reported for any purpose (Radulovich et al., Citation2015). Ethiopia, one of the countries in Africa, has Spirulina present in the Rift Valley lakes (Ravi et al., Citation2010), such as Lake Chitu and Lake Arengwade (green lake), with current usage limited to cattle feeding (Getachew et al., Citation2019). However, Spirulina is not known as a food or food supplement for humans in Ethiopia, although the country is affected by chronic malnutrition. Approximately 45% of the deaths of under-five-year-old children are directly or indirectly attributed to malnutrition, with 8% of these deaths being due to severe acute malnutrition (SAM) (Endalew et al., Citation2015). A shortage of nutritious food alternatives is one of the causes of childhood malnutrition (Landry et al., Citation2019), especially in developing countries like Ethiopia. The cultivation and consumption of Spirulina as a food supplement should be encouraged in developing countries where people are affected by chronic malnutrition (Mishra et al., Citation2013).

Although Spirulina is one of the top algae produced as human nutrition worldwide by companies operating in Japan, the USA, India, China, and Myanmar (Olabi et al., Citation2023), it is completely unknown in Ethiopia as a food supplement. To exploit the health and nutritional benefits of this underutilized protein source for solving undernutrition problems, Spirulina-fortified foods need to be developed, marketed, or provided through nutrition intervention programs. Before developing and marketing Spirulina-fortified foods, research must be conducted to familiarize consumers, local businesses, and the government with the health and nutrition benefits of Spirulina and contribute to solving the undernutrition and poverty problems that the country is facing. Particularly, understanding consumer perceptions, attitudes, and consumption behaviors with respect to functional foods is important (Calado et al., Citation2018; Natarajan et al., Citation2022). In the early development of functional foods, identifying consumer segments and actively engaging consumers would be a strategic approach for food suppliers or bakeries aiming for effective marketing of new products. A market-oriented approach to new product development (NPD) is considered a key to success in competitive and ever-evolving consumer markets, linked to higher profitability and success in developing new products (Repar & Bogue, Citation2023). Being market-oriented involves engaging consumers and generating insights to drive the NPD process. Although this study solely focuses on understanding consumers’ attitudes and intentions towards Spirulina-fortified bread in relation to their socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, it provides initial insights for food manufacturers, specifically bakery businesses, to involve urban Ethiopian consumers in the process of developing Spirulina-fortified bread.

In a country where microalgae, specifically Spirulina, is not known as a food or food supplement, investigating consumers’ consumption intentions for such a supplement in relation to their behavior and socioeconomic context is crucial. Therefore, this study chose bread to be enriched with spirulina. Since bread is widely consumed and familiar in Ethiopia, its popularity as a common food may facilitate the acceptance of Spirulina-fortified bread and make it easy to reach a wider population in a short period of time. The purpose of this study is to make three contributions to the body of literature on supplemental Spirulina in Ethiopia. Firstly, the study addresses a theoretical gap related to Ethiopian customers’ behavior towards a novel food, Spirulina-fortified bread. To the best of our knowledge, no specific theoretical framework has been applied explicitly to address the factors influencing consumers’ intentions to adopt Spirulina-fortified foods in Ethiopia. One of the theoretical frameworks widely applied to consumer behavior is the TPB. TPB has been applied to predict and explain many behaviors (Conradie et al., Citation2023; Savari et al., Citation2023; Teng et al., Citation2023; Vrhovec et al., Citation2023). Although the application of TPB in the study of consumers’ acceptance behaviors of functional foods is limited, a few recent studies (Le & Nguyen, Citation2022; Natarajan et al., Citation2022; Nystrand & Olsen, Citation2020; Salmani et al., Citation2020) have investigated consumers’ behavior towards functional foods using the TPB framework. This study applied and tested an extended version of the TPB (Nystrand & Olsen, Citation2020; Sadiq et al., Citation2021; Khanna et al., Citation2022) by incorporating the individual characteristics of urban Ethiopian consumers (Huang et al., Citation2020; Liu et al., Citation2021; Saxena, Citation2023) into the extended model. Additionally, this study goes beyond examining the individual effects of the three TPB constructs—attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control—on intention. It delves into understanding their interconnections and mutual influence, an aspect often overlooked in many consumer behavior studies, within the specific cultural and social context of Ethiopia.

Secondly, there is no empirical research conducted to address the unique socioeconomic, cultural, and contextual factors influencing urban Ethiopian consumers’ intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread. This study aims to examine how the behavioral, social, economic, and demographic characteristics of urban Ethiopian consumers influence their intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread. Thirdly, methodologically, this study utilized a survey method by providing respondents with prior information about the health and nutritional benefits of Spirulina, intending to nudge them towards developing a favorable intention. This is an effective way of informing people about new dietary supplements to encourage them to take the desired action, although their decision depends on their behavioral, social, economic, and demographic characteristics. In general, this study is the first to explore consumer attitudes and intentions towards consuming Spirulina-fortified food in Ethiopia.

Therefore, this study aimed to achieve the following specific objectives:

To examine the effect of the behavior of urban Ethiopian consumers on their intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread.

To examine the effect of the economic, social, and demographic characteristics of consumers on their intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread.

To identify mediation between behavioral and socioeconomic characteristics in influencing the intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread.

2. Theoretical framework

A sociopsychological theory called TPB is used to predict behavior and connect beliefs to actions. The theory proposes that the intention to engage in a desired action is influenced by three constructs: attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation2011). The theory assumes that the above behavioral constructs influence behavior intention that predicts actual behavior; that is, the greater the intention, the greater the likelihood of the individual undertaking the desired action (Ajzen, Citation1991). The TPB has been successfully implemented in studies that focus on explaining individual intentions and behaviors in a parsimonious structure of attitudes, norms, and control constructs across various domains of behavior (Gao et al., Citation2017). However, only a limited number of studies have applied TPB to study consumer behavior towards the consumption of functional foods. Nystrand and Olsen (Citation2020) investigated Norwegian consumers’ attitudes and intentions towards consuming functional foods. Another study by O’Connor and White (Citation2010) investigated Australian non-users’ willingness to try functional foods.

Several extended versions of the TPB have been proposed to increase its prediction ability, including background factors such as personality, values, demographics, and adaptation to contextual environments or unconscious habits (Ajzen, Citation2011; Conner, Citation2015). This study applied the TPB, which incorporates constructs such as attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control as predictors of consumption intention and individual characteristics of consumers, such as age, education, income, physical activity, and prior information on Spirulina as a food supplement.

2.1. Attitude

In the basic theory of reasoned action, proposed by Ajzen and Fishbein (Citation1980), a person’s intention to engage in a behavior results from the belief that performing the behavior will lead to a specific outcome. Similarly, in the TPB, intentions are the outcome of one’s attitude towards a particular activity. The more positive one feels about a behavior, the more intently one engages in that behavior (Amaro & Duarte, Citation2015). Consumers’ attitudes affect their intentions to consume functional foods (Nystrand & Olsen, Citation2020; O’Connor & White, Citation2010; Sandve & Øgaard, Citation2014). Attitude towards healthy eating is a well-established predictor of the intention to consume functional foods, organic foods, and healthy eating (Ferreira & Pereira, Citation2023; Moodi et al., Citation2021; Sobuj et al., Citation2021). A study by Maehle and Skjeret (Citation2022) revealed that attitude towards innovation in food significantly impact the willingness to pay for microalgae-based food among Norwegian consumers. In addition, attitude and perceived behavioral control were positively correlated, as evidenced in a study by Wongsaichia et al. (Citation2022). Therefore, it is anticipated that if consumers’ appraisal of consuming bread fortified with Spirulina is favorable, their intention to consume will rise. Accordingly, the following hypotheses were developed:

A positive attitude towards Spirulina-fortified bread positively affects intention.

A positive attitude towards Spirulina-fortified bread positively affects perceived behavioral control to eat Spirulina-fortified bread.

2.2. Subjective norms

The encouragement a consumer receives to eat healthy foods from friends, family, and coworkers is referred to as the subjective norm (Kim et al., Citation2013). Subjective norm has been identified as a construct that is frequently applied as a pre-decision factor (Sandve & Øgaard, Citation2014). People are more likely to act if their role models believe they ought to act (Schepers & Wetzels, Citation2007). Consumers are more likely to consume novel foods or food supplements if they perceive that their peers support them (Peña-García et al., Citation2020). Based on a study by Wongsaichia et al. (Citation2022), subjective norms have a significant impact on eco-friendly eating behavior. Norwegian consumers’ willingness to pay for microalgae-based food is highly and significantly influenced by subjective norms (Maehle & Skjeret, Citation2022). Several studies on sustainable food consumption have shown a significant positive relationship between subjective norms and consumers’ intention to make a purchase (Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation1980; Kumar et al., Citation2023). This demonstrates the inherent subjectivity of customer perceptions, which are influenced by their context and cultural background. The literature reveals that subjective norms directly influence attitudes towards food consumption and perceived behavioral control (Wongsaichia et al., Citation2022). Subjective norms have an indirect influence on intention to consume organic food through influencing attitudes, as demonstrated in previous studies (Al-Swidi et al., Citation2014; Tarkiainen & Sundqvist, Citation2005). Accordingly, the following hypotheses were developed:

Positive subjective norms for Spirulina-fortified bread positively affects intention.

Positive subjective norms regarding Spirulina-fortified bread positively affects attitudes.

Positive subjective norms regarding Spirulina-fortified bread positively affects perceived behavioral control.

Attitudes mediate the effect of subjective norms on intention.

2.3. Perceived behavioral control

The construct of perceived behavioral control refers to ‘people’s perception of the ease or difficulty of performing the behavior of interest’ (Ajzen, Citation1991). When choosing and consuming foods containing low-fat fruits and vegetables, consumers may experience a certain amount of control over external influences (Amaro & Duarte, Citation2015; Povey et al., Citation2000). Perceived behavioral control has a significant influence on healthy eating intentions (Gallagher et al., Citation2022; Ma et al., Citation2023; Nong et al., Citation2022). Hoyos-Vallejo et al. (Citation2023), Kabir (Citation2023), Khan et al. (Citation2023), Huo et al. (Citation2023), Dangaiso (Citation2023), Chiew et al. (Citation2023), and Loera et al. (Citation2022) found that perceived behavioral control influences the purchase intention of consumers towards organic products. Specific to the socio-cultural context of Ethiopia, perceived behavioral control could also play a mediating role in the relationship between attitude and intention, as well as subjective norms and intention. To determine whether perceived behavioral control affects urban consumers’ intention to eat Spirulina-fortified bread, this element of TPB must be thoroughly explored. Therefore, the following hypotheses were developed:

High perceived behavioral control in Spirulina positively affects intention.

The effect of attitude on the intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread is mediated by perceived behavioral control.

The effect of subjective norms on the intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread is mediated by perceived behavioral control.

2.4. Individual characteristics

Various studies incorporate individual characteristics to investigate their influence on behavioral intention, as well as their influence on other TPB constructs. These factors could have an indirect effect on intention to eat Spirulina-fortified bread by influencing attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. For example, Budhathoki and Pandey (Citation2021) found that socio-demographic and lifestyle characteristics indirectly impact behavioral intention through their effects on attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, knowledge, and environmental concern. Saxena (Citation2023) showed that age has a negative effect on behavior and intention. The finding of a study by Fantechi et al. (Citation2023) conducted in Italy revealed that young consumers under 40 years of age are interested in Spirulina-enriched pasta and are willing to pay a premium. Other studies, such as Kamenidou et al. (Citation2011), Lafarga et al. (Citation2021) and Lucas et al. (Citation2023) demonstrated that young age had already been a driver in consuming microalgae incorporated novel foods. As explained in Barrena et al. (Citation2015) and Gonera et al. (Citation2021), it may be due to the fact that older people are more conservative, while younger people are more open to novelties, including in food choices. This study hypothesizes that younger consumers are more inclined to consume Spirulina-fortified bread.

Being a young consumer positively affects their attitude towards Spirulina-fortified bread.

Being a young consumer positively affects perceived behavioral control when consuming Spirulina-fortified bread.

Being a young consumer positively affects their intention to consume Spirulina-fortified breads.

The effect of age on the intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread is mediated by the attitude.

The effect of age on perceived behavioral control is mediated by attitude towards Spirulina-fortified bread.

The effect of age on intention consuming Spirulina-fortified bread is mediated by perceived behavioral control.

Education plays a significant role in influencing attitudes, perceived behavioral control, and intentions. According to previous studies, education improves perceived behavioral control and intention behavior of adolescents and adults in eco-label food purchase behavior (Hajivandi et al., Citation2021), fruit and vegetable consumption behavior (Berning & Hogan, Citation2014; Lawal et al., Citation2021; Taghdis et al., Citation2016), and intention to consume fish (Verbeke & Vackier, Citation2005), indicating the role of education in behavioral intentions. On acceptance of Spirulina-enriched foods, Kamenidou et al. (Citation2011), Rzymski and Jaśkiewicz (Citation2017), Lafarga et al. (Citation2021), and Fantechi et al. (Citation2023) found that Education has shown to be a distinguishing characteristic of consumers choosing Spirulina pasta. These studies revealed that consumers having higher education are ready to choose Spirulina-fortified foods. The rationale is having higher education is associated with greater openness to change (Cattaneo et al., Citation2019; Vidigal et al., Citation2015). Since knowledge is one of the results of education, a study by Iannuzzi et al. (Citation2019) found that knowledge on innovative products increases the willingness to consume insect-based foods among Italian consumers. Therefore, the following hypotheses were developed:

: Education significantly affects attitude towards consuming Spirulina-fortified bread.

: Education significantly affects perceived behavioral control in consuming Spirulina-fortified bread.

: Education significantly affects the intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread.

The effect of education on intention is mediated by attitude towards Spirulina-fortified bread.

The effect of education on perceived behavioral control is mediated by the attitude towards Spirulina-fortified bread.

The effect of education on the intention consuming of Spirulina-fortified bread is mediated by attitude.

Income significantly affects the perceived behavioral control to consume Spirulina-fortified bread.

: Income significantly affects the intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread.

: The effect of income on the intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread is mediated by perceived behavioral control.

Physical activity positively affects attitude towards Spirulina-fortified bread.

: Physical activity positively affects perceived behavioral control in consuming Spirulina-fortified bread.

: Physical activity positively affects the intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread.

The effect of physical activity on the intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread is mediated by attitude.

The effect of physical activity on intention of Spirulina-fortified bread is mediated by perceived behavioral control.

: The effect of physical activity on perceived behavioral control is mediated by attitude towards the fortified bread.

Previous knowledge and information, and familiarity with Spirulina as a food supplement could influence the intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread. For example, Ateş (Citation2021) found that knowledge and information positively influence eco-label food purchase behaviors. Consumers’ intention to consume minimally processed vegetables is positively and significantly influenced by knowledge (Lawal et al., Citation2021; Stranieri et al., Citation2017). Familiarity with food has a favorable influence on the consumption of organic foods (Aungatichart et al., Citation2020). For example, knowledge on innovative food products is associated with higher willingness to consume insect-based foods (Iannuzzi et al., Citation2019). Other studies, such as Kamenidou et al. (Citation2011), Grahl et al. (Citation2018), Lafarga et al. (Citation2021), Lucas et al. (Citation2023), and Fantechi et al. (Citation2023) emphasize the importance of familiarity with functional foods, and they found that prior knowledge and use of these kinds of foods is crucial in the consumption of different functional foods. Accordingly, the following hypotheses were developed:

: Prior information about Spirulina positively affects attitude towards Spirulina-fortified bread.

: Prior information about Spirulina positively affects perceived behavioral control.

: Prior information about Spirulina positively affects the intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread.

The effect of prior information on intention is mediated by attitudes towards Spirulina-fortified bread.

: The effect of prior information on perceived behavioral control is mediated by attitude towards Spirulina-fortified bread.

: The effect of prior information on intention of Spirulina-fortified bread is mediated by perceived behavioral control.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Data collection and questionnaire

The target population of this study was urban dwellers in Addis Ababa and major cities in Northern Ethiopia, specifically cities in the Amhara regional state, which is the second-largest region with alarming malnutrition among the nine regions in Ethiopia (Menalu et al., Citation2021). A cross-sectional online survey of 361 randomly selected respondents was administered between April and May 2023. Respondents were required to be ≥18 years old, live in urban areas, have a mobile phone or computer, and have access to the internet. A software service (SaaS) company (Typeform) that specializes in online surveys was used to conduct consumer panel discussions and administer the survey. The survey was conducted in Addis Ababa and other regional cities in northern Ethiopia. The survey was conducted after receiving ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board for Human Research of SOKA University (number-2022-063). Consent to participate was obtained in written form for this study. Participants were presented with a consent statement immediately before the survey questions. This statement detailed the study’s objectives, procedures, and the rights of the participants. Participants were required to read the consent statement and indicate their consent by proceeding to answer the survey questions. The questionnaire was presented to participants in Amharic and English.

The first part of the questionnaire was about individual characteristics such as gender, age, education, income, physical activity, prior information on Spirulina as a food supplement, as well as weekly bread consumption frequency of respondents. Respondents were asked to respond to these questions at the beginning of the survey ().

Table 1. Description of individual characteristics.

Following the individual characteristics questions, we provided brief, basic information on the health and nutritional benefits of Spirulina. We adopted the three categories of information about Spirulina provided to participants in a study by Lucas et al. (Citation2023) after modifying the last statement in the ‘sensory properties category’ and adding one additional statement in the ‘health benefits’ category so that it can be matched with the current study objectives. The information provided to the participants is presented in .

Table 2. Basic information presented to the participants about the benefits of Spirulina: adapted from Lucas et al. (Citation2023) with little modification.

Immediately after the information, we asked the respondents each indicator of the four constructs of TPB: attitude towards Spirulina-fortified bread (six items), subjective norms (five items), perceived behavioral control (five items), and intention to consume the supplemented bread (five items), which were prepared using a 5-point hedonic scale (from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Since we developed the scales based on previous studies conducted in the same or related areas and reshaped them to match our objectives, there is no single reference for each construct or item. As a benchmark to develop the scales, attitude scales (Pienwisetkaew et al., Citation2022; Weickert et al., Citation2021; Xin & Seo, Citation2020), subjective norms (Natarajan et al., Citation2022; Pienwisetkaew et al., Citation2022; Rezai et al., Citation2017; Xin & Seo, Citation2020), perceived behavioral control (Natarajan et al., Citation2022; Pienwisetkaew et al., Citation2022; Sumaedi & Sumardjo, Citation2020; Xin & Seo, Citation2020), and intention to purchase (Chang et al., Citation2020; Natarajan et al., Citation2022; Pienwisetkaew et al., Citation2022; Shamal & Mohan, Citation2017; Xin & Seo, Citation2020) were used as a benchmark to develop the items of the TPB constructs. Based on the information provided, respondents were asked to respond to questions that incorporated the four TPB constructs ().

Table 3. Description of TPB constructs and items.

3.2. Analytical procedures

We analyzed the data using STATA (version 14.2) with the appropriate copyright license for the software. A two-stage procedure was used for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM) (Anderson & Gerbing, Citation1988). In Step 1, CFA was performed to measure each indicator’s relationship and its constructs, whether valid or reliable. In this step, goodness of fit (GOF), convergent validity, and discriminant validity of the measures were assessed. To check for GOF and convergent validity, the estimated results were compared to the threshold levels of root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08, comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.95, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) > 0.90, standardized root mean square residuals (SRMR) < 0.05, and average variance explained (AVE) > 0.50 (Ajzen, Citation1991). The traditional chi-square goodness-of-fit test was omitted because of sample size dependency issues (Marsh & Hocevar, Citation1985). Additionally, we used a threshold for construct reliability (CR) > 0.7 (Hair et al., Citation2014). Finally, the study considers the issues of multicollinearity by comparing the square root of AVE with the correlations of the variables (Nystrand & Olsen, Citation2020) and by estimating the variable inflation factor (VIF).

First, all latent and individual characteristic variables were tested. Based on the standardized factor loading, we decided to drop the first item of subjective norms (People who are important to me believe I should consume this bread) and the second item of perceived behavioral control (Consuming this new bread is entirely under my control) that had a loading value of 0.39 and 0.32, respectively, which is below the recommended value (0.5) to be retained (Knekta et al., Citation2019). Then, after evaluating the statistical significance of the association between intention and its predictors, we decided to drop those regressors that were not significant, namely gender and residence city. This improves the accuracy of the regressor effect estimates.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive analysis of respondent’s characteristics

The descriptive statistics results revealed that the proportion of respondents was higher for male (approximately 70%) than for female (30%) respondents, with a higher proportion of respondents aged 30 years, accounting for approximately 66% of the respondents. Most respondents were first-degree holders (about 54%), followed by MSc or above (about 30%), and diplomas or below (about 16%; ). Most respondents had a monthly disposable income of

3000 Ethiopian Birr (ETB), which is equivalent to 55.55 USD, accounting for approximately 47% (). Among the respondents, 71% had prior information about Spirulina as a food supplement, and the remaining 29% did not. Regarding engagement in regular physical activity, 51% engaged in regular physical exercise and 49% did not. In terms of residence, 62% of the respondents were living in regional cities and 38% were living in Addis Ababa (). Respondents were asked about their frequency of bread consumption on a weekly basis, which is crucial as we were focusing on enriching bread with Spirulina. Accordingly, most of the respondents (58%) consumed bread more than three times a week. The remaining 24% and 18% reported consuming bread two times a week or exactly three times a week, respectively (). No respondents chose the option ‘I’m not consuming bread at all’.

Table 4. Percentage distribution of respondents’ characteristics.

4.2. Mean and standard deviation of TPB constructs and items

The item means and the construct means of the TPB framework are presented in . The average response of all the indicators of attitude towards eating Spirulina-fortified bread was above 3.62, with a construct mean of 3.68, indicating that the respondents agreed on the statement indicating attitude towards consuming Spirulina-fortified bread (). This indicates that, other than remaining constant, the respondents had a positive attitude towards consuming Spirulina-fortified bread. Except for ‘I will eat if my peers think I should eat Spirulina-fortified bread’, which has a mean of 3.44, all the indicators of subjective norms have an average score of 3.56 and above, with a construct mean of 3.56. Perceived behavioral control and consumption intention had mean scores of 3.49 and 3.46, respectively ().

Table 5. Mean and standard deviation of the behavioral factor constructs and items.

4.3. Test of the measurement model

4.3.1. Factor loadings, reliability, and validity of the measurement model

For all the constructs, the composite reliability was above 0.8, which is above the cut-off value of 0.7 (), indicating good internal consistency of the model (Nunnally, Citation1987). The AVE value is above 0.5 (), indicating that the latent variables are valid (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). The value of the VIF ranged from 1.78 (perceived behavioral control) to 2.31 for attitude towards eating Spirulina-fortified bread (VIF < 5 was considered not to have multicollinearity) (Bowerman & O’Connell, Citation1994). This indicates the absence of an over-correlation between the constructs and has no impact on the estimation results of the model. The standardized factor loadings are above 0.5 for all constructs and significant at the 1% level of significance (), indicating a strong relationship between an item and a construct (Knekta et al., Citation2019).

Table 6. Standardized loadings, reliability, and validity of the CFA model.

4.3.2. Pearson’s correlation coefficient and discriminant validity

In CFA, discriminant validity measures the degree to which two or more theoretically similar constructs must be different. If the square root of the AVE of each construct is greater than the inter-construct correlation coefficient, the construct has adequate discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Furthermore, the construct is said to have adequate discriminant validity if the inter-construct correlation coefficient is <0.8 (Brown, Citation2015). The square root of AVE (presented on the diagonal) was higher than the off-diagonal correlation coefficients, and all correlation coefficients were below 0.8 (). Based on the test, all constructs theoretically measure the different constructs, indicating that the constructs are valid. In conclusion, the TPB model proposed in this study had adequate validity (convergent and discriminant) and reliability.

Table 7. Pearson’s correlation coefficient and discriminant validity.

4.3.3. Overall goodness of fit of the measurement model

While conducting structural equation modeling (SEM), Kline (Citation2015) suggested that, as a requirement, reporting the following indices. These are RMSEA, CFI, and SRMR. The TLI and CFI should both be >0.90, and the RMSEA value should be <0.08 to assess whether the model reasonably fits the data (Haagen et al., Citation2015). The RMSEA (0.046), CFI (0.958), TLI (0.947), and SRMR (0.038) values were within the acceptable threshold levels (<0.08, >0.95, >0.90, and <0.05, respectively) (). The reliability, validity, and diagnostic tests showed that all the indicators were good predictors of the constructs, allowing us to conduct further analyses.

Table 8. Overall goodness of fit of the measurement model.

4.4. Tests of the structural equation modeling

4.4.1. Structural relationship among TPB constructs

The results of the overall goodness-of-fit of the hypothesized structural model demonstrated adequate fit to the data (RMSEA = 0.046, CFI = 0.957, TLI = 0.947, and SRMR = 0.046). This section presents the structural relationship between the study variables and the test status of the postulated hypotheses. The decision to accept or reject the postulated hypotheses was made based on the direct and mediating effect of the explanatory variables on dependent variables based on the standardized path coefficients. The SEM analysis results presented below show that attitude and perceived behavioral control have a positive and significant direct effect on the intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread, supporting hypotheses and

, respectively (). Perceived behavioral control had a significant positive influence on the intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread (

= 0.75, p < 0.01). This indicates that personal ability to purchase and consume bread can directly influence consumption intention. Perceived behavioral control was positively and significantly influenced by attitude (

= 0.44, p < 0.01) and SUN (

= 0.32, p < 0.01), thus supporting

and

, respectively. This positive relationship indicates that those who have a more positive attitude towards the benefits of Spirulina and high subjective norms have a high perceived behavioral control to eat Spirulina-fortified bread. Attitude had direct (

= 0.14, p < 0.030) and indirect (

= 0.33, p < 0.001) positive effects on intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread. Subjective norms also had a direct positive and significant influence on attitude (

= 0.69, p < 0.01), thus supporting . This indicates that the more positive the subjective norms, the more positive the attitude towards consuming Spirulina-fortified bread.

Table 9. Structural relationship between the TPB constructs and hypotheses status.

4.4.2. Relationship between TPB constructs and individual characteristics

Attitude, perceived behavioral control, and intention were influenced by individual characteristics (). The age of the respondent had significant positive influence on attitude towards consuming Spirulina-fortified bread ( = 0.14, p < 0.1), indicating that younger consumers have a more positive attitude towards consuming Spirulina-fortified bread (). More favorable attitudes towards consuming Spirulina-fortified bread were found for consumers who were engaging in physical activity (

= 0.14, p < 0.05) and had prior information on Spirulina as a food supplement (

= 0.14, p < 0.1) supporting

and

, respectively (). Age had an indirect positive and significant influence on perceived behavioral control (

= 0.06, p < 0.1), indicating that younger consumers have a higher perceived behavioral control to eat Spirulina-fortified bread (). Regarding education, consumers with a diploma or lower education level have a lower perceived behavioral control to eat Spirulina-fortified bread, which was confirmed by a negative direct (

= -0.02, p < 0.05) and indirect (

= -0.08, p < 0.1) significant effect of education (≤diploma dummy) on perceived behavioral control, supporting

.

Table 10. Structural relationship between individual characteristics and constructs of the TPB.

Urban consumers who are engaged in physical activity have a greater perceived behavioral control to eat Spirulina-fortified bread, as confirmed by a positive direct ( = 0.16, p < 0.01) and indirect (

= 0.06, p < 0.05) significant effect of physical activity on perceived behavioral control (). Similarly, prior information has a direct (

= 0.11, p < 0.1) marginally significant positive effect on perceived behavioral control, indicating that consumers who have prior information about Spirulina as a food or nutritional supplement have a higher perceived behavioral control to eat Spirulina-fortified bread (). Regarding the effect of education on the intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread, education (≤diploma dummy) had an indirect (

= -0.25, p < 0.05) negative significant influence on the intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread, indicating that consumers with diploma and lower education levels have a lower positive intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread (). Prior information also has an indirect effect (

= 0.15, p < 0.05) on intention, indicating that those who have prior information on Spirulina have a more positive intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread, keeping all other things constant.

4.4.3. Results of the mediation analysis

The mediation analysis results showed that perceived behavioral control had a significant mediating role in the relationship between attitude and intention (RIT = 0.71; RID = 2.4) and between subjective norms and intention (RIT = 1.11; RID = 9.8), supporting and

, respectively (). This means that about 71% of the effect of attitude on intention was mediated by perceived behavioral control, and the mediated effect was about 2.4 times the effect of attitude on intention. Moreover, about 111% of the effect of subjective norms on intention was mediated by perceived behavioral control, and the mediated effect was about 9.8 times the effect of subjective norms on intention. Attitude also plays a complete mediating role in the relationship between subjective norms and intention (RIT = 1.36; RID = 3.8), supporting

(), which means that approximately 136% of the effect of subjective norms on intention is mediated by attitude, and the mediated effect is approximately 3.8 times as large as the direct effect of subjective norm on intention (). Education also significantly mediated the relationship between perceived behavior and intention (RIT = 2.12; RID = 1.89), supporting hypotheses

, respectively (). The effect of education on the intention to fortify Spirulina bread was mediated by perceived behavioral control (RIT = 2.12; RID = 1.89), supporting .

Table 11. Mediation effects.

Physical activity had a significant indirect positive effect on the intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread, indicating that consumers who engage in physical activity have a more positive intention to eat Spirulina-fortified bread (). This effect was mediated by attitude (RIT = 0.28; RID = 0.39) and perceived behavioral control (RIT = 0.71; RID = 2.54), supporting and

, respectively (), and this indicates that consumers who engage in regular physical activity have a more positive attitude towards Spirulina-fortified bread, resulting in a more positive intention to consume it.

5. Discussion

The main findings of this study revealed that attitude and perceived behavioural control constructs have a direct and significant influence on the consumption intention of Spirulina-fortified bread. Although attitude had a positive influence on intention, the strength of the effect was lower than that of the perceived behavioural control construct, which might be due to Ethiopian consumers’ unfamiliarity with this supplement. As revealed by the findings of previous studies, attitude plays a significant role in explaining intention behaviour among the TPB constructs. For example, a study by Nystrand and Olsen (Citation2020) found that attitude was the main determinant of consumption intention of functional foods among Norwegian consumers. On consumer’s intention to purchase functional non-dairy milk, Pienwisetkaew et al. (Citation2022) found that attitude has a significantly positive effect on purchase intention among Thai consumers. Similarly, in a study on consumers’ purchase intention for imported soy-based dietary supplements, Chung et al. (Citation2012) discovered that attitude has a significantly positive impact on purchase intention towards soy-based dietary supplements among Chinese consumers. Norwegian consumers’ attitudes toward innovation in food have a strong and significant effect on their willingness to pay for microalgae-based foods (Maehle & Skjeret, Citation2022). Consumer attitudes play a crucial role in their intention to consume functional foods (Nystrand & Olsen, Citation2020; O’Connor & White, Citation2010; Sandve & Øgaard, Citation2014). Attitudes toward healthy eating are well-established predictors of the intention to consume functional foods, organic foods, and maintain a healthy diet (Ferreira & Pereira, Citation2023; Haubenstricker et al., Citation2023; Huo et al., Citation2023; Kumar & Basu, Citation2023; Moodi et al., Citation2021; Nystrand & Olsen, Citation2020; Sobuj et al., Citation2021). A positive attitude towards foods and dietary supplements is a fundamental aspect of consumer behaviour in the consumption of functional foods. While positive attitudes toward functional foods, such as Spirulina-enriched foods, are becoming familiar in countries like Japan, the USA, China, India, and European countries, the attitude towards such foods in developing countries like Ethiopia is new. It may be challenging to alter the conservative attitude of the people towards such foods, which necessitates promotional and educational interventions to change their perceptions.

Consumers who have a greater degree of control over their perceived behaviour have a better intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread. This finding is consistent with that of a study by Nystrand and Olsen (Citation2020) on consumers’ intentions to consume functional foods in Norway, in which attitude and perceived behavioural control were the main determinants of consumption intention. In addition, Chung et al. (Citation2012) found that perceived behavioural control has a significant influence on Chinese consumers’ purchase intentions towards imported soy-based dietary supplements. Consumers’ perceived behavioural control was a strong predictor of consumers’ purchase intention of buckwheat functional foods in China (Nong et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, a study by Sumaedi and Sumardjo (Citation2020) found that perceived behavioural control has a significant effect on traditional functional food consumption behaviour. Perceived behavioural control explains women bodybuilders’ behaviors towards using dietary supplements (Haubenstricker et al., Citation2023). Other studies have shown the predictive role of perceived behavioural control on consumers purchase intentions of functional foods, organic foods, and seafood (Chiew et al., Citation2023; Ding et al., Citation2022; Huo et al., Citation2023; Kumar & Basu, Citation2023; Qi et al., Citation2023; Sobaih et al., Citation2023). Perceived behavioural control is a crucial factor influencing consumption intention, necessitating marketing strategies to enhance consumer education and promote the adoption of healthier food choices.

Subjective norms also influence attitudes towards consuming Spirulina-fortified bread, indicating that more positive subjective norms positively influence attitudes towards consuming Spirulina-fortified bread. This result is consistent with the findings of Singh and Verma (Citation2017) and Aertsens et al. (Citation2011) who found that subjective norms influence consumer attitudes towards consuming organic food products. Additionally, the effect of subjective norms on intention through influencing attitude was significant, indicating an indirect effect of social norms on the consumption intention of Spirulina-fortified bread by influencing the consumer’s attitude towards the supplemented bread. Although the study was focused on entrepreneurial intention, Nguyen et al. (Citation2023) found that entrepreneurial attitude significantly mediates subjective norms’ effect on entrepreneurial intention. However, other studies, such as that by Rezai et al. (Citation2017) tested and found that attitude does not have a mediation effect on subjective norms for Malaysian consumers to form their intention to purchase natural functional foods. Although it was established that subjective norms are a direct predictor of the intention of consumers to purchase and consume functional and organic products (Haubenstricker et al., Citation2023; Huo et al., Citation2023; Kumar & Basu, Citation2023; Moodi et al., Citation2021; Natarajan et al., Citation2022; Nong et al., Citation2022; Sumaedi & Sumardjo, Citation2020), in this study, subjective norms indirectly influence the intention of urban Ethiopian consumers towards consuming Spirulina-fortified bread by influencing their attitude and perceived behaviour control. These findings highlight how social norms are shaping Ethiopian consumers attitudes towards and confidence in their ability to consume new foods or dietary supplements.

Urban Ethiopian consumers with a more positive attitude towards the supplement have more perceived behavioural control that increases their ability to consume Spirulina-fortified bread. A study by Chung et al. (Citation2012) showed that perceived behavioural control also plays an important role in the formation of attitudes among Chinese consumers’ purchase intentions for imported soy-based dietary supplements. This result is also consistent with the finding of Pienwisetkaew et al. (Citation2022) which revealed that perceived behavioural control has a strong positive and significant influence on attitudes towards consuming functional non-dairy milk among Thai consumers. Another study by Ding et al. (Citation2022) revealed a mediating role of perceived behavioural control in the relationship between attitude and purchase intention for seafood. Although the study focused on two behaviours (exercising and reducing energy consumption), La Barbera and Ajzen (Citation2021) found that an increase in the score of perceived behavioural control increased the strength of the association between attitude and intention.

The findings of this study also revealed that a higher degree of positive social norms influences perceived behavioural control, which in turn influences the intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread. In other words, perceived behavioural control has a significant mediating role in the relationship between subjective norms and intentions. This indicates that the intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread is strongly influenced by social pressures exerted by others’ consumption of bread and recommendations to eat the bread. Also, more social norms strongly and positively influence perceived behavioural control over purchasing functional non-dairy milk among consumers in Thailand (Pienwisetkaew et al., Citation2022). Specific to urban Ethiopian consumers, as revealed in the results of this study, the effect of subjective norms on intention via influencing perceived behavioural control is strong. This result is somewhat opposite to the finding of the study by La Barbera and Ajzen (Citation2021), which found that an increase in the score of perceived behavioural control decreased the strength of the association between subjective norms and intention in exercising and reducing energy consumption behaviours. Other studies have demonstrated a significant direct positive effect of subjective norms on the intention to consume functional (Chung et al., Citation2012; Nystrand & Olsen, Citation2020; Rezai et al., Citation2017) and sustainable food (Shen et al., Citation2022). Although the role of social norms in food consumption varies, some studies (Oliver et al., Citation2023; Rezai et al., Citation2017; Savari et al., Citation2023; Verbeke & Vackier, Citation2005) have found a strong effect on intention, whereas others (Conner, Citation2015) have found a weak or no effect.

Regarding the socioeconomic and lifestyle characteristics of consumers, this study found that younger consumers have a more positive attitude towards consuming Spirulina-fortified bread, as demonstrated by the significant positive effect of age on attitude. In addition, younger consumers have higher perceived behavioural control to consume Spirulina-fortified bread. This result is consistent with that of Mamun et al. (Citation2020) who found that young Malaysian adults have a positive attitude towards healthy foods, which in turn positively influences consumption intention. A study on the acceptance of Spirulina-enriched pasta in Italy conducted by Fantechi et al. (Citation2023) revealed that consumers under 40 years of age show a keen interest in Spirulina-enriched pasta and are willing to pay a premium. Other studies have also indicated that a younger age is a driving force for the consumption of novel foods incorporating microalgae (Kamenidou et al., Citation2011; Lafarga et al., Citation2021; Lucas et al., Citation2023). This inclination may be attributed to the fact that older individuals tend to be more conservative, whereas younger individuals are more open to novelties, particularly in their food choices (Barrena et al., Citation2015; Gonera et al., Citation2021). While Spirulina supplements are equally beneficial for all age groups, focusing on designing marketing or nutrition intervention strategies that target the younger demographic would be effective for the swift implementation of such supplements among the Ethiopian population. Functional foods, including Spirulina-fortified ones, are also crucial for aging populations (Bogue et al., Citation2017), as global population aging poses a significant societal and economic challenge, though not an issue in Ethiopia, where around 50% of the population is under the age of 19.

In terms of education, consumers with a diploma or lower education level perceive less behavioral control to eat Spirulina-fortified bread. This was confirmed by a negative direct and indirect significant effect of education (≤ diploma dummy) on perceived behavioral control. Similarly, consumers with diplomas and lower education levels have a lower positive intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread. The education status of consumers has proven to be a distinguishing characteristic in their choice of Spirulina-enriched foods (Fantechi et al., Citation2023; Kamenidou et al., Citation2011; Lafarga et al., Citation2021; Rzymski & Jaśkiewicz, Citation2017). This is underpinned by the observation that higher education levels are associated with greater openness to change (Cattaneo et al., Citation2019; Vidigal et al., Citation2015). Knowledge, an outcome of education, regarding innovative products has been shown to increase the willingness of Italian consumers to adopt insect-based foods (Iannuzzi et al., Citation2019). These studies indicate that consumers with higher education levels have better control over their behavior and an increased ability to incorporate healthy foods, such as Spirulina-enriched foods, into their diets. Therefore, educational interventions are crucial to instruct and encourage consumers to choose foods designed to contribute to people’s health. It is evidenced that educational intervention programs improve people’s ability to consume and their intention to consume eco-label food products (Hajivandi et al., Citation2021) and their intention to consume fish (Verbeke & Vackier, Citation2005).

The effect of physical activity on intention was also significantly mediated by attitudes and perceived behavioural control. Similarly, a more favourable attitude towards consuming Spirulina-fortified bread was significant for consumers engaged in physical exercise. This positively influenced the intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread. According to Fantechi et al. (Citation2023), physically active individuals constitute an intriguing segment, given the potential benefits of increased protein intake during and after workouts. Spirulina could serve as a valuable natural supplement for those who engage in regular exercise. An intervention study by Daryabeygi-Khotbehsara et al. (Citation2021) found that a physical activity intervention improved perceived behavioral control in healthy eating. Additionally, a study by Fantechi et al. (Citation2023) revealed that individuals involved in sports are more likely to consume Spirulina-enriched pasta than those who are not engaged in physical exercise. Other studies conducted by Moons et al. (Citation2018) have found that sporting individuals’ functional food consumption is only partly driven by health motives; they are also motivated to take in nutrients that help them to compete in their sports or shape their bodies. The potential health benefits of Spirulina appeal to those seeking to enhance fitness and well-being. Therefore, awareness creation through educational campaigns that highlight the nutritional content of Spirulina, collaborating with fitness influencers, product placement in fitness centres, and collaborating with sports nutrition brands would be the best strategy to familiarize people with this nutritional supplement.

Prior information about Spirulina as a food/nutritional supplement significantly affects perceived behavioural control, indicating that consumers with prior information about Spirulina as a food or nutritional supplement have high perceived behavioural control to eat Spirulina-fortified bread. Previous studies revealed that information on the health benefits of Spirulina improves consumers’ perceived behaviour (Grahl et al., Citation2018) and informs consumers about the health benefits of Spirulina to prefer the Spirulina-colored product (Rosenau et al., Citation2023). Knowledge and information about healthy eating and organic foods have a significant positive influence on attitudes towards healthy eating and food purchases, as demonstrated by Mamun et al. (Citation2020) and Chiew et al. (Citation2023). Prior information also had an indirect effect on intention, indicating that those who had prior information on Spirulina had a more positive intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread. Similar results were reported by Weinrich and Elshiewy (Citation2019), García-Segovia et al. (Citation2020), and Lafarga et al. (Citation2021), who reported that consumers’ purchases, willingness to pay, and consumption of Spirulina-fortified products are affected by their knowledge and information on the health benefits of Spirulina. Additionally, according to Iannuzzi et al. (Citation2019), a higher willingness to consume insect-based foods is influenced by consumers’ knowledge of innovative food products. Familiarity with functional foods and prior knowledge and usage of such products are crucial in explaining the consumption of various functional foods (Fantechi et al., Citation2023; Grahl et al., Citation2018; Lucas et al., Citation2023). Chiew et al. (Citation2023) also found that knowledge of organic food is a significant predictor of both organic food purchase intention and behaviour. These findings underscore the importance of raising awareness to facilitate the effective implementation of nutrition interventions and promote Spirulina-fortified functional foods. To introduce this supplement widely to the public, especially consumers, implementing a large-scale promotion and advertisement campaign is crucial. This aims not only to familiarize consumers with the nutritional benefits of spirulina but also to provide information on its pricing and availability.

6. Conclusions

The findings of this study revealed that TPB constructs, such as perceived behavioural control and attitude, were significant predictors of intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread while mediating the relationship between subjective norms and consumption intention. The effect of subjective norms on intention is mediated by attitudes and perceived behavioural control. Previous information on Spirulina and engagement in regular physical activity positively influenced attitude, perceived behaviour, and intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread. Age, education, and income also played direct or indirect roles in influencing TPB constructs.

Since this supplement is new for most consumers, awareness of the health and nutritional benefits of this supplement could be used as the best strategy to improve consumers’ attitude towards this Spirulina-incorporated bread. The findings of this study will help those who are going to develop and market Spirulina-fortified bakery products, as well as government bodies that work on providing nutritional foods to improve the health of citizens. Scientifically, the findings of this study will contribute to the existing literature by analysing the relationships among TPB constructs and between TPB constructs and consumer characteristics in explaining the intention to consume Spirulina-fortified foods.

7. Practical implications and future research directions

The findings of this study on the behavioral, socioeconomic, and demographic effects on urban Ethiopian consumers’ intention to consume Spirulina-fortified bread have significant implications for the Ethiopian government, food producer businesses, and researchers and academicians. To enhance the nutrition and health status of the Ethiopian people, the government, particularly specific bodies such as the Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute (EBI), Ethiopian Ministry of Innovation and Technology (MiNT), Ethiopian Ministry of Health (MoH), Ethiopian Food and Drug Authority (EFDA), and Quality and Standard Authority of Ethiopia (QSAE), should collaborate as pioneer stakeholders. Their joint efforts can identify and exploit nutrient-dense resources like Spirulina to develop functional foods and algae-driven drugs, fostering entrepreneurship and innovation given the local availability of Spirulina. The study provides valuable insights for policymakers, enabling the development of evidence-based nutrition intervention policies to maximize the utilization of this supplement.

The results of this study are instrumental in helping food producers design more effective marketing strategies for incorporating the supplement into their products. This is particularly beneficial for reaching consumers with a positive attitude towards consuming such fortified foods, as well as early adopters like athletes and sporting individuals. Additionally, the study is valuable for consumers actively seeking functional foods of this nature. For food producers, including bakeries, flour producers, and spice suppliers, this study offers insights that can guide their decisions. They can consider either importing Spirulina from other countries such as Japan, the USA, China, and India or use the locally available Spirulina to incorporate it into their food production systems. The findings may inspire them to plan for the production of Spirulina powder from Ethiopian lakes in the long run.

Finally, as this supplement is relatively new in the realm of food and food supplements, this study can serve as a benchmark for researchers and academicians. It can guide further research on how to introduce the supplement to the local market and explore ways to deliver this dietary supplement to malnourished populations. In general, this study can be eye-opening for government stakeholders, businesses, and researchers. It provides insights on how to efficiently utilize not only this untapped resource but also other plants to develop functional foods. This, in turn, can contribute significantly to addressing the malnutrition problem in Ethiopia.

Although this study can have both theoretical and practical implications, it solely focuses on consumers’ perceptions and attitudes toward the supplement, which may not be sufficient for businesses aiming to develop and provide this bread. Further studies on sensory acceptability and willingness to pay for the product need to be conducted by engaging sufficient consumers, leaving this avenue open for future research.

Author contributions

Adino Andaregie: Conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software, writing the original draft. Hirohisa Shimura: Conceptualization, questionnaire development, methodology, writing-review & editing. Mitsuko Chikasada: Conceptualization, questionnaire development, writing-review & editing. Satoshi Sasaki: Writing, reviewing, and editing. Shinjiro Sato: Project Administration, Writing, Review, and Editing. Solomon Addisu: writing, reviewing, and editing. Tessema Astatkie: writing, reviewing, and editing. Isao Takagi: Project administration, validation, and data curation. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our gratitude to Mr. Yoshiyuki Hirata, the coordinator of the SATREPS-EARTH project, for his invaluable efforts in coordinating and facilitating the necessary inputs that contributed to the successful completion of this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data will be made available upon request from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Adino Andaregie

Adino Andaregie is a PhD candidate at the Graduate School of Economics, SOKA University in Tokyo, Japan. He obtained a BA degree in economics from Addis Ababa University in Ethiopia. His research areas include microeconomics, macroeconomics, economic policy, financial economics, development economics, agricultural economics, health economics, and behavioural economics, with a specific focus on growth and development, production, efficiency, finance, investment, innovation, marketing, consumer behaviour, business growth, dietary choices, nutrition intervention, food policy and regulation, and nudging behavioural interventions. He has published more than 15 papers in Scopus-indexed journals in collaboration with other researchers.

Hirohisa Shimura

Hirohisa Shimura is a Professor in the Faculty of Business Administration at Soka University in Tokyo, Japan. He obtained his PhD in pharmaceutical science from the University of Tokyo, Japan. His research fields include economic policy, business administration, medical management, medical sociology, hygiene and public health (both laboratory and non-laboratory approaches), and statistical sciences.

Mitsuko Chikasada

Mitsuko Chikasada is a Professor in the Faculty of Economics at Soka University, Tokyo, Japan. She obtained her PhD in Agricultural, Environmental, Regional Economics, and Demography from Pennsylvania State University, USA. Her research areas include agricultural and food economics, environmental economics, and population studies.

Satoshi Sasaki

Satoshi Sasaki is a Professor in the Faculty of Nursing at Soka University in Tokyo, Japan. He obtained his PhD in epidemiology from the Graduate School, Division of Medicine, at the University of Leuven. His research areas include health and public health (both laboratory and non-laboratory), healthcare management, and medical sociology, with a specific interest in nutritional epidemiology.

Shinjiro Sato

Professor Shinjiro Sato is a PhD holder in soil science obtained from the University of Florida, USA, in 2003. Currently, he is a professor in the Department of Science and Engineering for Sustainable Innovation of the Faculty of Science and Engineering at Soka University, Tokyo, Japan. His research topics are soil science, biochar, sustainable agriculture, anaerobic digestion, and waste treatment.

Solomon Addisu

Solomon Addisu is an Associate Professor of Environmental Sciences in the College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences at Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia. He completed his PhD studies in the field of environmental sciences, specializing in climate change and agriculture, at Andhra University, India. He is actively engaged in research and outreach programs related to the environment and climate change, having published over 40 peer reviewed articles and book chapters.

Tessema Astatkie

Tessema Astatkie is a Professor of Statistics at the Faculty of Agriculture at Dalhousie University, Canada. He conducts collaborative research in various agriculture related areas with researchers from over 35 countries. His work has resulted in several papers published in over 100 journals indexed in Scopus.

Isao Takagi

Isao Takagi is a Professor in the Faculty of Economics, Department of Economics, at Soka University in Tokyo, Japan. He completed his PhD in Global Economics Studies at Soka University. His research areas include economic policy, humanities and social sciences, with specific interests in human needs, capability, human well being, economic development, ASEAN community formation, and Asian economies.

Notes

The term ‘functional food’ was coined in Japan in the early 1980s. It’s defined as dietary items that, besides providing nutrients and energy, beneficially modulate one or more targeted functions in the body by enhancing a certain physiological response and/or by reducing the risk of disease (Nicoletti, Citation2012).

References

- Aertsens, J., Mondelaers, K., Verbeke, W., Buysse, J., & Van Huylenbroeck, G. (2011). The influence of subjective and objective knowledge on attitude, motivation, and consumption of organic food. British Food Journal, 113(11), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070701111179988

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen, I. (2011). The theory of planned behaviour: reactions and reflections. Psychology & Health, 26(9), 1113–1127. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2011.613995

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice-Hall.

- Alberto de Morais Watanabe, E., Alfinito, S., Castelo Branco, T. V., Felix Raposo, C., & Athayde Barros, M. (2023). The consumption of fresh organic food: premium pricing and the predictors of willingness to pay. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 29(2-3), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10454446.2023.2185118

- Al-Swidi, A., Mohammed Rafiul Huque, S., Haroon Hafeez, M., & Noor Mohd Shariff, M. (2014). The role of subjective norms in theory of planned behavior in the context of organic food consumption. British Food Journal, 116(10), 1561–1580. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-05-2013-0105

- Amaro, S., & Duarte, P. (2015). An integrative model of consumers’ intentions to purchase travel online. Tourism Management, 46, 64–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.06.006

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Anyanwu, R., Rodriguez, C., Durrant, A., & Olabi, A. G. (2018). Micro-macroalgae properties and applications. Reference module in materials science and materials engineering. Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-803581-8.09259-6

- Arahou, F., Lijassi, I., Wahby, A., Rhazi, L., Arahou, M., & Wahby, I. (2023). Spirulina-based biostimulants for sustainable agriculture: Yield improvement and market trends. BioEnergy Research, 16(3), 1401–1416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12155-022-10537-8

- Arnautovska, U., Fleig, L., O’Callaghan, F., & Hamilton, K. (2019). Older adults’ physical activity: The integration of autonomous motivation and theory of planned behaviour constructs. Australian Psychologist, 54(1), 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12346

- Ateş, H. (2021). Understanding students’ and science educators’ eco-labeled food purchase behaviors: Extension of theory of planned behavior with self-identity, personal norm, willingness to pay, and eco-label knowledge. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 60(4), 454–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/03670244.2020.1865339

- Aung, M. T. T., Dürr, J., Borgemeister, C., & Börner, J. (2023). Factors affecting consumption of edible insects as food: Entomophagy in Myanmar. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed, 9(6), 721–739. https://doi.org/10.3920/JIFF2022.0151

- Aungatichart, N., Fukushige, A., & Aryupong, M. (2020). Mediating role of consumer identity between factors influencing purchase intention and actual behavior in organic food consumption in Thailand. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences, 14(2), 424–449.

- Barrena, R., García, T., & Camarena, D. (2015). An analysis of the decision structure for food innovation on the basis of consumer age. The International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 18(3), 149–170.

- Berning, J., & Hogan, J. J. (2014). Estimating the impact of education on household fruit and vegetable purchases. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 36(3), 460–478. https://doi.org/10.1093/aepp/ppu006

- Bogue, J., Collins, O., & Troy, A. J. (2017). Chapter 2: Market analysis and concept development of functional foods A2: Bagchi, Debasis. Developing New Functional Food and Nutraceutical Products, 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-802780-6.00002-X

- Bowerman, B. L., & O’Connell, R. T. (1994). Linear statistical models: An applied approach (2nd ed.). Duxbury Press.

- Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Budhathoki, M., & Pandey, S. (2021). Intake of animal-based foods and consumer behaviour towards organic food: The case of Nepal. Sustainability, 13(22), 12795. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212795

- Cai, J., & Leung, P. (2022). Unlocking the potential of aquatic foods in global food security and nutrition: A missing piece under the lens of seafood liking index. Global Food Security, 33, 100641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2022.100641

- Calado, R., Leal, M. C., Gaspar, H., Santos, S., Marques, A., Nunes, M. L., & Vieira, H. (2018). How to succeed in marketing marine natural products for nutraceutical, pharmaceutical and cosmeceutical markets. In P. Rampelotto & A. Trincone (Eds.), Grand challenges in biology and biotechnology (pp. 317–403). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69075-9_9

- Campanella, L., Crescentini, G., Avino, P., & Moauro, A. (1998). Determination of macrominerals and trace elements in the alga Spirulina platensis. Analusis, 26(5), 210–214. https://doi.org/10.1051/analusis:1998136

- Cattaneo, C., Lavelli, V., Proserpio, C., Laureati, M., & Pagliarini, E. (2019). Consumers’ attitude towards food by-products: The influence of food technology neophobia, education and information. International Journal of Food Science & Technology, 54(3), 679–687. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijfs.13978

- Chang, H. P., Ma, C. C., & Chen, H. S. (2020). The impacts of young consumers’ health values on functional beverages purchase intentions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103479

- Chetioui, Y., Butt, I., Lebdaoui, H., Neville, M. G., & El Bouzidi, L. (2023). Exploring consumers’ attitude and intent to purchase organic food in an emerging market context: A pre- and post-COVID-19 pandemic analysis. British Food Journal, 125(11), 3979–4001. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-12-2022-1070

- Chiew, D. K. Y., Zainal, D., & Sultana, S. (2023). Understanding organic food purchase behaviour: using the extended theory of planned behaviour. International Journal of Business Innovation and Research, 31(2), 268–294. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBIR.2023.131433

- Chung, J. E., Stoel, L., Xu, Y., & Ren, J. (2012). Predicting Chinese consumers’ purchase intentions for imported soy-based dietary supplements. British Food Journal, 114(1), 143–161. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070701211197419

- Conner, M. (2015). Extending and not retiring the theory of planned behaviour: A commentary on Sniehotta, Presseau and Araújo-Soares. Health Psychology Review, 9(2), 141–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2014.899060

- Conradie, P., Van Hove, S., Pelka, S., Karaliopoulos, M., Anagnostopoulos, F., Brugger, H., & Ponnet, K. (2023). Why do people turn down the heat? Applying behavioural theories to assess reductions in space heating and energy consumption in Europe. Energy Research & Social Science, 100, 103059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2023.103059

- Dangaiso, P. (2023). Extending the theory of planned behavior to predict organic food adoption behavior and perceived consumer longevity in subsistence markets: A post-peak COVID-19 perspective. Cogent Psychology, 10(1), 2258677. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2023.2258677

- Daryabeygi-Khotbehsara, R., White, K. M., Djafarian, K., Shariful Islam, S. M., Catrledge, S., Ghaffari, M. P., & Keshavarz, S. A. (2021). Short-term effectiveness of a theory-based intervention to promote diabetes management behaviours among adults with type 2 diabetes in Iran: A randomised control trial. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 75(5), e13994. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.13994