Abstract

Amidst the shifting landscapes of education and economic development, the burgeoning significance of entrepreneurial intention within educational institutions has captured the attention of researchers and policymakers alike. As the nexus between academia and society continues to evolve, understanding the profound impact of entrepreneurial aspirations on graduates’ lives and the broader socioeconomic landscape has become a focal point for scholarly research and policy formulation. The present endeavor is an attempt to check the direct as well as indirect contributing role of proactive personality by taking self-regulation as mediator toward shaping entrepreneurial intention among university graduates. The purpose of this study is to examine the significance of entrepreneurial intention through institutions toward socio-economic development, with its immense influence on graduates’ lives and society in general. Finally, it is contended that proactive personality and self-regulation are both significant personality traits of graduates that infuse feelings of entrepreneurship in their minds. A total of 315 business administration graduates from different public-sector universities in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (a province of Pakistan) were surveyed. Questionnaires, containing scales adopted from the existing literature, were employed as data collection instruments to measure the current study constructs after obtaining Research Ethics Clearance from the Multimedia University. Scale reliability, correlation, mediation, and statistical tools were employed to test the present study’s hypotheses. The results revealed a significant positive association between proactive personality, entrepreneurial intention, and self-regulation. Self-regulation was also found to play a catalytic role in mediating the association between proactive personality and entrepreneurial intention in the current study context. A significant positive link between entrepreneurial intention and proactive personality. validated the common concept that individuals with proactive personality attributes have the capability to alter their environment by initiative and working diligently unless the desired target is achieved.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

In contemporary times, numerous countries have redirected their attention toward fostering innovation-driven growth by promoting start-ups as a key strategy for economic development. This shift is driven by the encouragement of young entrepreneurs to establish new ventures, thereby creating employment opportunities and addressing unemployment challenges (Lee et al., Citation2022). Pakistan, in its race to rise to the ranks of nations with developed economic status, faces numerous challenges, including unemployment, slow growth, and youth bulge (Nawaz, Citation2020). Pakistan is the fifth most populous country in the world, with two-thirds comprising youth. It is quite difficult for the Pakistani government and business community to provide such a huge amount of employment opportunities, which is an alarming situation. Entrepreneurship is the only key to overcoming this situation, as entrepreneurs not only engage in earning activities for themselves but also provide job opportunities to the community and hence share the burden over the economy (Nawaz et al., Citation2020). Entrepreneurship is acknowledged as a basic component of economic growth and prosperous development (Yaqoob, Citation2020). One prominent area of entrepreneurship is the extent of one’s willingness to start a new business; that is, entrepreneurial intention (Nawaz, Citation2020). Entrepreneurial intention is a basic indicator that may reflect the future entrepreneurial behavior of an individual. It may be demarcated as an inclination; a person must start his or her own venture (Krueger et al., Citation2000).

According to Chamola and Jain (Citation2017), individuals with certain personality characteristics are generally more rapidly attracted to entrepreneurship. Henry et al. (Citation2003) found personality traits to be forerunners of entrepreneurial intention by Henry et al. (Citation2003). It is argued that proactive personality also lies within the sphere of personality (Nawaz, Citation2020). A proactive personality is an element in which an individual’s behavioral tendency toward enacting and changing his/her environment is captured. Individuals having proactive personality are unrestrained by environmental forces and even take control for changing environment (Spurk et al., Citation2013). Moreover, proactive individuals may seek new and dynamic opportunities, taking initiative and persevering to bring about fruitful change (Bateman & Crant, Citation1999). Creative ideas may be generated through proactiveness that needs to be linked and expressed to market needs to discover the possibility of customers’ acceptance of these generated ideas in innovative workplaces (Bagis, Citation2022).

Opportunity recognition is a significant aspect that has been widely established by researchers in the field of entrepreneurship, particularly the cognitive process underlying opportunity recognition, which has received extensive attention in the past few years (Tumasjan & Braun, Citation2012). Furthermore, they are of the view that the role of self-regulation in early-stage opportunity recognition cannot be ignored (Tumasjan & Braun, Citation2012).

Self-regulation is a distinctive personality trait in which people pursue control over their thoughts, impulses, emotions, and even their specific task achievements (Baumeister et al., Citation2006). Self-regulation has recently emerged as a theoretical concept in the field of entrepreneurship (Bryant, Citation2007; Nawaz et al., Citation2020; Tumasjan & Braun, Citation2012). Whenever an individual faces an undecided, complex, and uncertain situation, such as choosing entrepreneurship as a career choice, self-regulation may help the individual judge his or her capabilities to ratify his/her inclination and direct their behavior to fulfill the desired task (Pihie & Bagheri, Citation2013).

This study delves into a critical area of interest which is understanding the factors that influence entrepreneurial intention among university graduates, particularly in the context of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Previous studies have revealed that some personality traits like risk aversion, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and need for achievement as important determinants of entrepreneurial intention (e.g. Qazi et al., Citation2022; Wu et al., Citation2019). The effect of proactive personality among the other personality traits should also be noted (Chen, Citation2024). In the field of entrepreneurship and business, numerous studies explored the positive impact of proactive personality on performance, firm-based innovativeness, and self-employment (Mueller et al., Citation2017; Paul & Shrivatava, Citation2016; Wolfe & Patel, Citation2016). Recently, some researchers contended significant positive relationship of proactive personality and entrepreneurial intention among university students in the educational context research (Butz et al., Citation2018; Hossain & Asheq, Citation2020; Kumar & Shukla, Citation2019). However, some researchers have raised questions about the association of proactive personality and entrepreneurial intention (Chipeta & Surujlal, Citation2017; Obschonka et al., Citation2018). For instance, Chipeta and Surujlal, (Citation2017) did not find any positive association of proactive personality with social entrepreneurial intention in their study of 294 South African students. To this end, the predictive role of proactive personality toward entrepreneurial intention has not been clearly established and hence needs further empirical evidence (Chen, Citation2024).

Recently, it was also suggested that more empirical research is required to uncover the potential mediation and/or moderation mechanism through which proactive personality may impact entrepreneurial intention (Hu et al., Citation2018; Zhang et al., Citation2022). Hence, self-regulation is tested as playing the mediating role in the relationship of proactive personality and entrepreneurial intention among university graduates in this study. Although the concept of self-regulation is not new in the field of entrepreneurship research (Amato et al., Citation2017; Bryant, Citation2007; Gielnik et al., Citation2020; Michaelis et al., Citation2020; Winkler et al., Citation2023), however, very little is known about the underlying learning mechanism through which entrepreneurs acquire self-regulation capabilities. By focusing on proactive personality and self-regulation as the key determinants, this study addresses a gap in the literature concerning the pathways through which these personality traits shape entrepreneurial aspirations. Using Baron and Kenny (Citation1986) mediation analysis approach, the study seeks to show that proactive personality predicts entrepreneurial intention, with self-regulation playing a mediating role in this relationship. The findings of this study contribute to the existing literature by offering empirical evidence of the influential role of graduates’ proactive personality traits in shaping their entrepreneurial intentions and behaviors. Moreover, by highlighting the mediating role of self-regulation, the study provides insights into the underlying mechanisms through which proactive personality influences entrepreneurial intention among university graduates. Overall, this research adds valuable knowledge to the field of entrepreneurship and sheds light on the factors that drive individuals to pursue entrepreneurial endeavors as a career choice.

The rationale for this study is multifaceted. Firstly, entrepreneurship plays a pivotal role in fostering economic growth and development, particularly in regions like Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan where entrepreneurial ventures can significantly contribute to job creation and innovation. Understanding the psychological factors driving entrepreneurial intention is therefore crucial for policymakers, educators, and stakeholders aiming to cultivate an entrepreneurial ecosystem (Al-Qadasi et al., Citation2023).

Secondly, the choice of proactive personality as a focal point is strategic. Individuals with proactive personality are known for their initiative-taking and problem-solving abilities, traits that are inherently linked to entrepreneurial behavior (Sun, Citation2020). By investigating the direct influence of proactive personality on entrepreneurial intention, the study sheds light on the foundational disposition of aspiring entrepreneurs.

Thirdly, the inclusion of self-regulation as a potential mediator adds depth of understanding to the analysis. Self-regulation refers to regulating oneself and also involve managing one’s thinking, feelings and behavior in accordance with some specific desired objectives (Arenius & Brough, Citation2022). Additionally, self-regulation, encompasses aspects such as goal-setting and impulse control, is fundamental in translating proactive tendencies into concrete actions and ventures. By examining self-regulation as a mediator, the study elucidates the mechanism through which proactive personality manifests into entrepreneurial intention, offering valuable insights for intervention and skill development programs.

Furthermore, the study’s focus on business administration graduates is significant as there is a growing trend in the field of entrepreneurship that university students are more likely to be involved in business startups (Jiatong et al., Citation2021; Neneh, Citation2020). Moreover, these individuals represent a key demographic with the potential to drive entrepreneurial initiatives and contribute to economic progress. By examining the relationship between personality traits and entrepreneurial intention within this specific cohort, the study provides targeted insights that can inform educational curricula, career counseling services, and policy initiatives aimed at fostering an entrepreneurial mindset among graduates. In essence, this study will provide insights that is not only useful for academia but also for practical applications in policy formulation, educational interventions, and economic development strategies.

Literature review

Theoretical foundation of the study

Various studies have attempted to explain why some people are attracted to entrepreneurship while others are not. In the field of entrepreneurship, a large body of knowledge focuses on psychological and social factors. Currently, psychological and social perspectives are dominated by trait theory, social cognitive theory, and the theory of planned behavior. Supporters such as Reynolds et al. (Citation1994), Herron and Robinson (Citation1993), and Cunningham and Lischeron (Citation1991) of the trait model assert that people with particular sociological, demographic, and personality attributes are attracted to entrepreneurship phenomena. Nevertheless, several academics have criticized the trait model, arguing that since entrepreneurship is the process of creating a new business, it should be researched through individual activities (Van de Ven & Drazin, Citation1984). As a result, the emphasis has changed to cognitive theories, such as the idea that entrepreneurship is planned (Krueger et al., Citation2000), and as a result, entrepreneurial decision adoption is centralized. Intention-based models have been created to understand why people act in an entrepreneurial manner (Ajzen, Citation1991; Bird, Citation1988; Shapero & Sokol, Citation1982). People will need to focus on their cognitive processes in order to take advantage of a chance that will affect how they see their own capacity, control, and intentions, according to supporters of this line of research.

Proactive personality and entrepreneurial intention

Proactive personality, defined by a propensity for proactive behavior, is indicative of a comparatively steady tendency to recognize, assess, and seize opportunities that can impact one’s own socioeconomic circumstances, independent of situational limitations (Crant, Citation1996). According to earlier empirical studies (Cai et al., Citation2021; Jiatong et al., Citation2021; Murad et al., Citation2021), personality factors have a major influence on university students’ aspirations to pursue entrepreneurship. People that possess a proactive personality are more likely to be inclined toward entrepreneurship, which is a positive personality feature. Previous studies (Paul & Shrivatava, Citation2016; Zareieshamsabadi et al., Citation2010) have demonstrated the significant and favorable impact that proactive personalities have on individuals’ aspirations to pursue entrepreneurship. The proactive nature of university students has a major impact on their entrepreneurial goals, according to studies conducted in the field of educational research (Hossain & Asheq, Citation2020; Zeb et al., Citation2019). Proactive personality positively influenced entrepreneurial goals, according to research conducted by Basar (Citation2017) using college students in Istanbul as their subjects. In a similar vein, a different study (Li et al., Citation2020a) on Chinese college students found that proactive personalities improved their intentions to become entrepreneurs as well as efficiently converted them into actions. These results imply a correlation between more business intention and a proactive personality. The researchers therefore postulate that:

H1: Proactive personality is positively associated to entrepreneurial intention among university graduates.

Proactive personality and self-regulation

Self-regulation is a personality trait that allows people to control and modify their actions and to change themselves to fit social norms. Humans have a much stronger ability to self-regulate than other animals, but they are still far below the ideal level, which is why people face personal and societal problems due to their self-regulation failure (Baumeister et al., Citation1994). According to Muraven and Baumeister (Citation2000), self-regulation works in the same way as a person’s limited ability to change and control their behavior.

A person’s capacity to alter or influence behavior to assure compliance with ideal social, moral, legal, and other norms is viewed as essential to success in life as well as one of the most significant and distinctive aspects of human nature. One could argue that the only important quality that provides someone with the capacity to overcome other personality qualities is their level of self-regulation. It is also true that if a person has sufficient self-regulation, he or she will always act in an adaptive and proper manner, regardless of any neuroses, tendencies, or prior experiences. Abdullah (Citation2023) revealed in his study, by taking a sample of university students, a significant positive association of proactive personality with self-regulation which indicates that the students having high scores in proactive personality also having high level of self-regulation. Self-regulation is a form of personality strength (Baumeister et al., Citation2006). Since proactivity is a trait that may be categorized as personality, it is hypothesized that:

H2: Proactive personality and self-regulation are positively related among university graduates.

Self-regulation and entrepreneurial intention

Previous studies have widely used the concept of self-efficacy to predict individuals’ motivation to perform various challenging roles, even though to predict graduates’ intention to become entrepreneurs in the future and to establish their own businesses (e.g. Chen et al., Citation1998; Tyszka et al., Citation2011) however, self-regulation has recently been incorporated in studies relevant to business, education, and entrepreneurship (McMullen & Shepherd, Citation2002; Tumasjan & Braun, Citation2012).

The self-regulation concept refers to the process in which an individual must direct his or her behavior toward achieving a set target despite having plenty of difficulties and complexity. Here, self-regulation may be connected to entrepreneurial intention with the view that, although for establishing a new venture, an individual will have to face different challenges and obstacles at the beginning, he or she will have to focus on his or her objective and will have to direct his or her behavior to the way through which he or she can achieve the objective of establishing a new venture (Bryant, Citation2007). The existing literature supports the concept that self-regulation plays a vital role in entrepreneurial process (Baron et al., Citation2016; Gu et al., Citation2018; Molino et al., Citation2018). In instance, Kour and Sharma (Citation2020) revealed that a significant positive association of self-regulation with entrepreneurial intention among undergraduate, graduate and post-graduate students of rural areas from Udampur district, in their study. Tewal and Sholihah (Citation2020) contended that they found a significant positive association of self-regulation and entrepreneurial intention in their study. They revealed that individuals having strong self-regulation may have a strong intention to establish their own ventures by having the ability to overcome the obstacles such as doubt and fear, which they may have to face while establishing their own businesses. Molino et al. (Citation2018) reported in their study that entrepreneurs obtain high self-regulation scores than non-entrepreneurs. Hence, having self-regulation trait, individuals may align their actions to the future goals more meaningful to them (Dzomonda & Neneh, Citation2023). It is also posited that self-regulation may help the university graduates to remain committed and focused to their entrepreneurial intention goals. Based on this foundation it is hypothesized that:

H3: Self-regulation is positively associated with entrepreneurial intention among university graduates.

Self-regulation as a mediator

Self-regulation is the concept that people attempt to control their emotions, ideas, zeal, and demands, as well as their personal and professional acts (Baumeister et al., Citation2006). The available literature on the connection between self-regulation and motivation from personality traits is expanding in the context of performance (e.g. Kanfer, Citation1990).

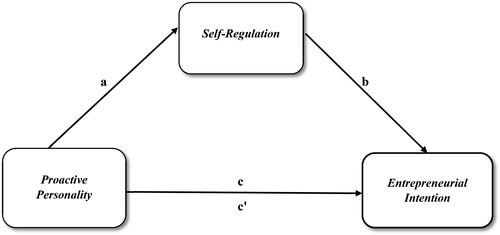

According to Sarason et al. (Citation1995), assessing anxiety and researching the acquisition of complex cognitive skills, self-regulation may be the reason for poor outcomes if attention is distracted from the targeted activities. On the other hand, it might be an effective and efficient effort tool in opposing circumstances. Self-regulation flairs are regarded as a crucial stage in the development of personality. Matthews et al. (Citation2000) discussed broader personality traits such as neuroticism as a self-regulatory attribute of behavior, whereas the current study focuses on a narrow personality trait, proactive personality. Matthews et al. (Citation2000) wanted more evidence about the predictive role of proactive personality toward various behavioral outcomes, that is, intentions ().

According to the correlations between proactive personality and entrepreneurial intention outlined above, both proactive personality and self-regulation are effective predictors of entrepreneurial intention. Furthermore, self-regulation is a salient catalytic element for predicting entrepreneurial process (Baron et al., Citation2016; Dzomonda & Neneh, Citation2023; Gu et al., Citation2018). This study aimed to determine whether self-regulation can act as a catalyst in the relationship between proactive personality and entrepreneurial intention among university graduates. Although proactive personality has been proven to be significantly associated with entrepreneurial intention, this study hypothesizes that self-regulation can play a substantial role as a mediator in this relationship. Therefore, it is proposed that:

H4: The association between proactive personality and entrepreneurial intention is mediated by self-regulation among university graduates.

Methods and procedures

Research design

Ethical approval for the study (Ref: No. EA0342022) was obtained from the Multimedia University Ethics Committee, ensuring that the research was conducted in accordance with established ethical guidelines and standards. Written informed consent was obtained from all the respondents well before the commencement of data collection. The current study has adopted a quantitative research approach, which is commonly employed for collecting and analyzing numerical data. This method involves the use of statistical techniques to uncover patterns, trends, and relationships within the data. By analyzing averages and making predictions, researchers can draw conclusions about causal connections and make inferences that may be generalized to the broader population.

Population and sample

Written informed consent was obtained from all the respondents well before the commencement of data collection. The target population was made up of business administration final year graduates enrolled in public sector universities of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. The prime motive for selecting this specific target population was that they were about to complete their academic career and were prepared to transition into practical life by selecting a career option. Probability and a simple random sampling procedure are used because of the homogeneous population set. This method works well in populations that are homogenous, meaning that every respondent is similar to every other respondent. As a data gathering tool, a questionnaire with Likert type options is used. The concerned departments provided information regarding the number of enrolled business graduates in their final academic year at different public-sector universities of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. At the time of data collection, 2038 graduates were enrolled overall. 335 sample size was determined using Yamane’s (Citation1967) formula for sample size. A total of 350 questionnaire sets were given out to respondents, and 315 completed questionnaires were returned for further analysis.

Measurement

The measurement scales employed in the study were adopted from established research in the field. The Bateman and Crant (Citation1999) proactive personality scale, comprising 17 items, was utilized to gauge the proactive personality trait of students among university graduates, providing insights into their proactive tendencies. Additionally, the self-regulation scale developed by Grant and Higgins (Citation2003), consisting of 11 items, was employed to evaluate the emotional responses of the target sample concerning self-regulatory behaviors. Furthermore, the entrepreneurial intention scale devised by Liñán and Chen (Citation2009), comprising 6 items, was utilized to assess the inclination of university graduates toward entrepreneurship, shedding light on their aspirations to embark on entrepreneurial ventures in the future.

Data analysis tools

The statistical tools utilized in this study were chosen based on their appropriateness for addressing the research objectives and hypotheses. Scale reliability and validity were assessed using a measurement model, through Smart-PLS as applied and recommended by Saif et al. (Citation2024) to ensure the robustness and accuracy of the measurement instruments. This approach is consistent with best practices in psychometric testing and ensures that the constructs being studied are accurately captured by the chosen measurement scales. Correlation analysis, as recommended by Naseeb et al. (Citation2019), Rehman et al. (Citation2013), and Saif et al. (Citation2024) was employed to explore the relationships between variables and to identify potential patterns or associations in the data. The use of correlation analysis allows for a comprehensive examination of the interrelationships among key variables, providing valuable insights into their connections. Additionally, simple mediation analysis, as described by Shah et al. (Citation2022) and using Model 4 from the PROCESS macros developed by Hayes (Citation2013), was employed to investigate the mediating role of self-regulation in the relationships under study. This approach enables a nuanced understanding of the underlying mechanisms driving the observed associations, thereby enhancing the depth of analysis and interpretation. Overall, the selected statistical tools were deemed appropriate for addressing the research questions and hypotheses, ensuring the rigor and validity of the study findings.

Measurement model

The internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of the model given by Hair et al. (Citation2017) are examined in order to quantify the measurement model of the current study variables.

Convergent validity

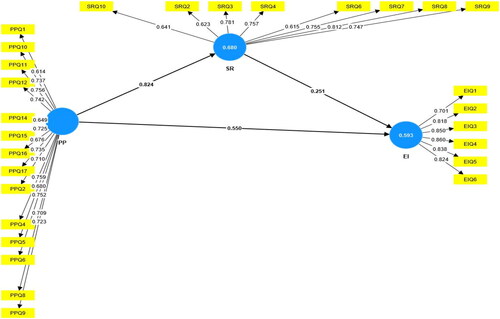

Results for confirming convergent validity of current study constructs are presented in .

Table 1. Measurement model.

displays the composite reliability (CR) values, which represents scale internal consistency as well as reliability, and which ranges from 0.895 to 0.935 for all the three present study constructs, above the minimum acceptable value of 0.60 (Khan et al., Citation2018). Factor loading (FL) and average variance extracted (AVE), both of which must be more than 0.70 and 0.50, can be used to evaluate convergent validity (Hair et al., Citation2014). The factor loading values of all the items and the average variance extracted (AVE) in this instance both meet the minimal requirements for acceptable validity, indicating that convergent validity is good. The item loading on each latent construct is shown in .

shows the graphical results for the relevant extracted values. The number above each path from the latent variable to the item indicates the values of item loading.

Discriminant validity

To determine the scale employed, discriminant validity generally uses three approaches presented by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981), the cross-loading approach by Hsu and Lin (Citation2016), and the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) by Henseler et al. (Citation2015). As per the first approach, the researcher calculated and contrasted the correlation coefficient values of the study variables with their square root values for the assessment of discriminant validity.

As the AVE square root values exceeded the corresponding correlation values of the components used in the current study, demonstrates strong discriminant validity.

Table 2. Discriminant validity - Fornell-Larcker criterion.

Due to the fact that all three constructs’ HTMT values are below the cutoff value of 0.850, showed that the scales used to measure the current study’s constructs are also verified by this method (Henseler et al., Citation2015).

Table 3. HTMT.

Common method variance

For checking common method bias in the data, the most commonly used Harman’s one factor test was conducted using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) via SPSS (Fuller et al., Citation2016). The results from this test indicate that one factor with only 43.68% variance (which is less than 50%) in the presence of six factors with eigenvalue of more than 1 was extracted which indicate that there is common method bias is not a concern (Fuller et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, the influence of common latent factor was also checked where no common method bias was found in the data.

Correlation analysis

A correlation analysis was conducted to test the relationship-related hypotheses developed for the current study constructs. A correlation analysis was conducted to test the strength and direction of the association between the variables (Nawaz, Citation2020). Empirical results obtained from the correlation analysis are presented in the following .

Table 4. Summary of correlation coefficients.

The results in show a significant positive relationship between proactive personality and entrepreneurial intention (β = 0.754, p = 0.000) and self-regulation (β = 0.822, p = 0.000) in the present study context. The results also revealed a significant positive relationship between self-regulation and entrepreneurial intention (β = 0.688, p = 0.000) among university graduates. Hence, hypotheses H1–H3 are accepted.

Table 5. Summary of mediation analysis.

Mediation analysis

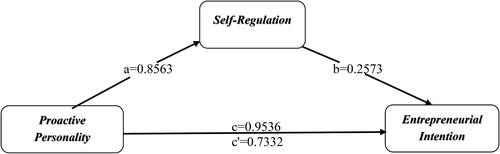

Self-regulation is considered a mediating construct in the association between proactive personality to entrepreneurial intention among university graduates. The PROCESS macros proposed by Hayes (Citation2013) were employed to test the mediation-related hypothesis developed for the present study. Hayes (Citation2013) suggested 76 different models for testing the direct and indirect effects of predictors on criterion variables through various mediators and moderators. In the present study, a single mediator i.e. self-regulation is involved; hence, the Model 4 as proposed by Hayes (Citation2013) is therefore adopted for this study as shown in .

The above model considers self-regulation as a mediating variable in the relationship between entrepreneurial intention and proactive personality.

According to the findings in , the overall model for predicting entrepreneurial intention through proactive personality is significant (F = 655.470, p = 0.0000), and it also significantly explains the variation in entrepreneurial intention (R2 =0.6768). Proactive personality with self-regulation (a = 0.8563, p = 0.0000), and entrepreneurial intention (c = 0.9536, p = 0.0000) were also found significantly positively associated according to the empirical results obtained from mediation analysis. Self-regulation has also been found to be strongly positively associated with entrepreneurial intention (b = 0.2573, p = 0.001).

Table 6. Research hypotheses and major findings.

After incorporating the mediating influence of self-regulation as a mediator, the association between proactive personality and entrepreneurial intention was still significantly positive (c’ = 7332, p = 0.000). Moreover, the results also revealed the total effect of the predictor on criterion, that is, 0.9536 with 95% CIs [0.8616, 1.0456], the direct effect (0.7223 with 95% CIs [5739, .8926], and indirect effect, 0.2204 with 95% CIs [0.0454, 0.3803]. The presence of mediating role-playing by mediator in the relationship between predictor and criterion may be confirmed by looking at the 95% lower level and upper-level confidence intervals that should not cross zero. In the present case, as all the 95% confidence intervals lower levels and upper levels of all the effects (i.e. total, direct, and indirect) also not crossing zero hence self-regulation mediates the association of predictors with criterion variables in the present study context. However, the fact that both the c (c = 0.9536, p = 0.000) and c’ (c’ = 0.7332, p = 0.000) paths are significant which indicates partial nature mediating role of self-regulation in the present study context.

Discussion

Entrepreneurship plays a vital role in economic growth and hence in economic development (Dzomonda & Neneh, Citation2023). Entrepreneurial intention is the pre-requisite for entrepreneurship process and hence considered as salient originator for new venture creation process (Uysal et al., Citation2022). This concept has inspired researchers’ interest to identify the determinants of entrepreneurial intention (Uysal et al., Citation2022). The current study was also conducted with the motive to investigate the direct influence of proactive personality on university graduates’ entrepreneurial intentions, as well as the indirect effects of self-regulation acting as a mediator in the connection. To accomplish this, a survey of 315 business administration graduates studying in their final year at public sector universities in KP, Pakistan, was conducted. The results showed a significant positive association of proactive personality with entrepreneurial intention in the current study context. These results are consistent with the findings of Hu et al. (Citation2018) and Prieto (Citation2010), who examined the association between proactive personality and social entrepreneurial intention among American, African, and Hispanic undergraduates and found a significant positive relationship. Through their research, they concluded that graduates who take initiative and are proactive are extremely motivated to start their own businesses. Proactive personality was also found to be positively associated with self-regulation among university graduates. These findings are in line with the findings obtained by Abdullah (Citation2023) who revealed a significant positive association of proactive personality and self-regulation by taking a sample from university students and concluded that students with high proactive personality score also have high score level of self-regulation. Results also revealed a significant positive association of self-regulation and entrepreneurial intention among university graduates. These results are consistent with the results presented by Tewal and Sholihah (Citation2020) who contended in their study a significant positive association of self-regulation and entrepreneurial intention with the view that individuals having high level of self-regulation also possess high intention to start their own venture by having the ability to handle all the challenges like doubt, fear of failure etc. which they may have to face while establishing their own businesses. Additionally, it has been discovered that self-regulation plays a mediating role in the relationship between proactive personality and entrepreneurial intention among university graduates. These findings confirm the arguments made by previous researchers (e.g. Barba-Sánchez et al., Citation2022; Hussain & Imran Malik, Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2016; Zhao et al., Citation2005) about the fact that when individuals have more control over their behavior, they have a more proactive attitude and, in turn, reinforce their entrepreneurial intention. Based on these findings, it is inferred that graduates’ self-regulation and proactive personality, are both, significant personality traits that encourage entrepreneurial behavior.

Conclusion and study implications

By drawing on already established theories of personality, self-regulation and entrepreneurship, current research presents a solid theoretical framework for understanding the association of proactive personality, self-regulation and entrepreneurial intention. Upon existing literature, hypotheses were formulated and hence was guided to empirical research. Through surveying 315 final year business graduates from various public sector universities of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, this study provides empirical evidence in the support of its theoretical assertions. By quantifying measuring constructs such as proactive personality, self-regulation and entrepreneurial intention, empirical validity to theoretical concepts were demonstrated by this study’s findings, strengthening the understanding of how these elements interact in the real world. By demonstrating significant association of proactive personality, self-regulation and entrepreneurial intention among university graduates, it is contended that proactive personality as well as self-regulation are both important personality traits of graduates, which sparks feelings of entrepreneurship among them, and hence, they will seriously think about starting their own businesses instead of becoming job seekers and will impact not only their own lives positively but also their societies. Overall, this study offers a comprehensive understanding of the relationships that exist among proactive personality, self-regulation and entrepreneurial intention, providing valuable guidance for both theoretical and practical applications in education as well as economic development contexts.

Theoretical implications of the study

Some important repercussions follow the findings of this study. First, findings from the study confirm previous findings, that is, Miao (Citation2015) found a significant positive link between entrepreneurial intention and proactive personality. These findings validate the common concept that individuals with proactive personality attributes can alter their environment by initiative and work diligently unless the desired target is achieved. This is also true of entrepreneurs, who are considered to be more risk-tolerant and search for opportunities in their surroundings by availing that they can bring positive change not only in their own lives but also in their surroundings (Fuller & Marler, Citation2009; Stewart & Roth, Citation2004). Second, in this study, self-regulation was incorporated as a mediating construct in the association between proactive personality and entrepreneurial intention among university graduates. One of the key components of success in life is self-regulation, which is the capability of an individual to modify responses to align them with ideal norms. As a result, the ability to regulate one’s own behavior is among the most important factors, because it allows one to adequately govern other personality traits. Therefore, regardless of neuroses or prior experiences, a person must always act in an adaptive or moral manner if their capacity for self-regulation is sufficiently strong.

Practical implications of the study

By demonstrating significant positive association of proactive personality, self-regulation and entrepreneurial intention, present study offers some practical implications for economic development, policymakers and education. First, entrepreneurship plays a vital role in driving economic growth and creating employment opportunities. By empirically examining the significance of entrepreneurial intention through educational institutions, current study underlines the importance of assimilating the entrepreneurship education into academic curriculum. Graduates equipped with entrepreneurial intention and skills are more likely attracted toward initiating innovative businesses, contributing to economic development and address societal issues through entrepreneurial solutions. Second, the findings of current endeavor may be used by policymakers for policy formulation aimed at promoting entrepreneurship and innovation within educational institutions and beyond. Policymakers can consider present study findings to design such policies which support entrepreneurship education, providing resources for aspiring entrepreneurs and to create an enabling environment for startups. By nurturing entrepreneurial culture, societies can capitalize on potential of entrepreneurial ventures to drive job creation, economic growth and societal progress. Third, university employees and professors have a significant impact on graduates’ personal and personality development. They aid in the growth of children’s sense of adventure, leadership, and invention. According to Lee et al. (Citation2022), who found that personal entrepreneurial characteristics can be learned and exercised through interactions with the environment and participating in entrepreneurial-related activities, universities are recommended to involve graduates in entrepreneurial-related activities from an early age to promote entrepreneurship. Universities are encouraged to conduct different types of events to encourage graduates to establish their businesses. Different types of seminars, workshops, business plans competition, establishing small businesses at campuses may be the tools of enhancing their personality attributes and may lead graduates to divert their intentions from job seeking approach toward establishing their own businesses (Ismail et al., Citation2009).

Limitations and suggestions for future research

Although current study has achieved its objectives, it has some limitations to address. Firstly, final year business graduates from public universities in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan were chosen as target population which may pose a limitation of in terms of the lack of results generalizability. Future studies may test the current model by adding students from other disciplines too, like, economics, engineering and commerce. Similarly, more generalized results may be obtained by adding higher educational institutions from other provinces of the country as well as considering private sector universities in the data collection. Second, the present study was a cross-sectional study that focused on predicting entrepreneurial intention, not on the realization of this intention. Before entrepreneurial intention is converted into real venture creation, a series of complex activities are involved in the process according to theory and empirical evidence (Miao, Citation2015). Therefore, it is suggested that future researchers perform longitudinal studies to test the links among intention, opportunity searching behavior, and consequent venture creation to understand these complex activities within the new venture creation process. Similarly, by realizing the importance of proactive personality in shaping entrepreneurial intention among university graduates, future research should examine the possibility of how university graduates may be more proactive. The organizational climate, training sessions, and other relevant factors may contribute to making an individual more or less proactive. Third, self-regulation is tested as mediating the association of proactive personality and entrepreneurial intention among university graduates. The same model may be extended by adding some additional mediators and moderators to elucidate the mechanism underlying the relationship of personality traits with entrepreneurial intention. Future researchers can explore the role of other psychological factors like hope, risk taking propensity, resilience, cognizance or creativity in mediating or moderating the effecting association of proactive personality and entrepreneurial outcomes.

Author contributions

Tufail Nawaz: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization and design, Methodology, Data analysis, Writing – review & editing. Gerald Goh: Supervision, Conceptualization and design, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Ong Jeen Wei: Supervision, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Yasri, Ahmad Ali and Dwi Eko Waluyo – Data analysis, Writing – review & editing. Tufail Nawaz and Gerald Goh contributed to the final version of the manuscript and approved the work for submission.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tufail Nawaz

Dr. Tufail Nawaz is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Business Administration, Gomal University, Pakistan. His areas of research interests are entrepreneurship, human resource management, green banking practices, environmental sustainability and employee performance. He is currently the Internal Controller of Exams as well as the member of Research Supervisory Committee in the Department of Business Administration, Gomal University, Pakistan.

Gerald Guan Gan Goh

Dr. Gerald Goh Guan Gan is a Professor in the Faculty of Business, Multimedia University, Malaysia. His research interests are in knowledge management, information systems, environmental sustainability, business management, heritage tourism and mass communication. He is currently the Director of Strategy and Quality Assurance at Multimedia University and is a member of the Centre of e-Services, Entrepreneurship and Marketing at the Faculty of Business.

Jeen Wei Ong

Dr. Jeen Wei Ong is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Management, Multimedia University. His research interests include the areas of small and medium enterprises, entrepreneurship, strategic management, agriculture technology adoption among and sustainable issues in management. He is currently the Director of Alumni Engagement, Career and Entrepreneurship Development at Multimedia University.

Yasri Yasri

Dr. Yasri Yasri is a Professor in the Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Negeri Padang, Indonesia. His research interests are in Marketing Management, Strategic Management, Small and Medium Enterprises, Entrepreneurship, Business Management and Green Marketing. He is currently the Vice Rector for External Affairs at Universitas Negeri Padang.

Ahmad Ali

Dr. Ahmad Ali is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Business Administration, Gomal University, Pakistan. His research areas include human resource management practices, organisational culture and entrepreneurship. He is currently the co-ordinator of the undergraduate program in the Department of Business Administration, Gomal University, Pakistan.

Dwi Eko Waluyo

Dr. Dwi Eko Waluyo is an Assistant Professor in the Post Graduate Program at the Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Dian Nuswantoro, Semarang, Indonesia. His research interests are in knowledge management especially in financial technology literacy among small medium enterprises, computational finance and data analytics. He is currently the Director of Cooperation and International Affairs at Universitas Dian Nuswantoro, Semarang, Indonesia.

References

- Abdullah, A. J. (2023). A proactive personality and its relationship to self-regulation of postgraduate students. Ishraqat Tanmawia, 8(34), 852–900.

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Al-Qadasi, N., Zhang, G., Al-Awlaqi, M. A., Alshebami, A. S., & Aamer, A. (2023). Factors influencing entrepreneurial intention of university students in Yemen: The mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1111934. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1111934

- Amato, C., Baron, R. A., Barbieri, B., Bélanger, J. J., & Pierro, A. (2017). Regulatory modes and entrepreneurship: The mediational role of alertness in small business success. Journal of Small Business Management, 55(S1), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12255

- Arenius, P., & Brough, A. (2022). Self-managing on the entrepreneurial rollercoaster: Exploring cycles of self-regulation depletion and recovery. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 17, e00318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2022.e00318

- Bagis, A. A. (2022). Building students’ entrepreneurial orientation through entrepreneurial intention and workplace spirituality. Heliyon, 8(11), e11310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11310

- Barba-Sánchez, V., Mitre-Aranda, M., & del Brío-González, J. (2022). The entrepreneurial intention of university students: An environmental perspective. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 28(2), 100184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2021.100184

- Baron, R. A., Mueller, B. A., & Wolfe, M. T. (2016). Self-efficacy and entrepreneurs’ adoption of unattainable goals: The restraining effects of self-control. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(1), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2015.08.002

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Basar, P. (2017). Proactivity as an antecedent of entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Economic & Management Perspective, 11(4), 285–295.

- Bateman, T. S., & Crant, J. M. (1999). Proactive behavior: Meanings, impact, and recommendations. Business Horizons, 42(3), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0007-6813(99)80023-8

- Baumeister, R. F., Stillwell, A. M., & Heatherton, T. F. (1994). Guilt: An interpersonal approach. Psychological Bulletin, 115(2), 243–267.

- Baumeister, R. F., Gailliot, M., DeWall, C. N., & Oaten, M. (2006). Self-regulation and personality: How interventions increase regulatory success, and how depletion moderates the effects of traits on behavior. Journal of Personality, 74(6), 1773–1801. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00428.x

- Bird, B. (1988). Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intention. The Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 442–453. https://doi.org/10.2307/258091

- Bryant, P. (2007). Self-regulation and decision heuristics in entrepreneurial opportunity evaluation and exploitation. Management Decision, 45(4), 732–748. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740710746006

- Butz, N. T., Hanson, S., Schultz, P. L., & Warzynski, M. M. (2018). Beyond the Big Five: Does grit influence the entrepreneurial intent of university students in the US? Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 8(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-018-0100-z

- Cai, L., Murad, M., Ashraf, S. F., & Naz, S. (2021). Impact of dark tetrad personality traits on nascent entrepreneurial behavior: The mediating role of entrepreneurial intention. Frontiers of Business Research in China, 15(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11782-021-00103-y

- Chamola, P., & Jain, V. (2017). Towards Nurturing Entrepreneurial Intention from Emotional intelligence. SIBM Pune Research Journal, XIII, 26–34.

- Chen, C., Greene, P., & Crick, A. (1998). Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? Journal of Business Venturing, 13(4), 295–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(97)00029-3

- Chen, H. X. (2024). Exploring the influence of proactive personality on entrepreneurial intention: The mediating role of entrepreneurial attitude and moderating effect of perceived educational support among university students. SAGE Open, 14(1), 21582440241233379. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241233379

- Chipeta, E. M., & Surujlal, J. (2017). Influence of attitude, risk taking propensity and proactive personality on social entrepreneurship intentions. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 15(2), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.17512/pjms.2017.15.2.03

- Crant, J. M. (1996). The proactive personality scale as a predictor of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Small Business Management, 34(3), 42–49.

- Cunningham, J. B., & Lischeron, J. (1991). Defining entrepreneurship. Journal of Small Business Management, 29(1), 45–61.

- Dzomonda, O., & Neneh, B. N. (2023). How attitude, need for achievement and self control personality shape entrepreneurial intention in students. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 26(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v26i1.4927

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388.

- Fuller, B., Jr., & Marler, L. E. (2009). Change driven by nature: A meta-analytic review of the proactive personality literature. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75(3), 329–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.05.008

- Fuller, C. M., Simmering, M. J., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y., & Babin, B. J. (2016). Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3192–3198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.008

- Gielnik, M. M., Bledow, R., & Stark, M. S. (2020). A dynamic account of self-efficacy in entrepreneurship. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(5), 487–505. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000451

- Grant, H., & Higgins, E. T. (2003). Optimism, promotion pride, and prevention pride as predictors of quality of life. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(12), 1521–1532. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203256919

- Gu, J., Hu, L., Wu, J., & Lado, A. A. (2018). Risk propensity, self-regulation, and entrepreneurial intention: Empirical evidence from China. Current Psychology, 37(3), 648–660. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9547-7

- Hair, J. F., Gabriel, M., & Patel, V. (2014). AMOS covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM): Guidelines on its application as a marketing research tool. Brazilian Journal of Marketing, 13(2), 44–45.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., & Thiele, K. O. (2017). Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(5), 616–632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0517-x

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. The Guilford Press.

- Henry, C., Hill, F., & Leitch, C. (2003). Entrepreneurship education and training. Ashgate, Aldershot, 47(3), 158–169. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910510592211

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Herron, L., & Robinson, R. B. (1993). A structural model of the effects of entrepreneurial characteristics on venture performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 8(3), 281–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(93)90032-Z

- Hossain, M. U., & Asheq, A. A. (2020). Do leadership orientation and proactive personality influence social entrepreneurial intention? International Journal of Management and Enterprise Development, 19(2), 109–125. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMED.2020.107396

- Hsu, C. L., & Lin, J. C. C. (2016). Effect of perceived value and social influences on mobile app stickiness and in-app purchase intention. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 108, 42–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.04.012

- Hu, R., Wang, L., Zhang, W., & Bin, P. (2018). Creativity, proactive personality, and entrepreneurial intention: The role of entrepreneurial alertness. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 951. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00951

- Hussain, S., & Imran Malik, M. (2018). Towards nurturing the entrepreneurial intentions of neglected female business students of Pakistan through proactive personality, self-efficacy and university support factors. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 12(3), 363–378. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-03-2018-0015

- Ismail, M., Khalid, S. A., Othman, M., Jusoff, H., Rahman, N. A., Kassim, K. M., & Zain, R. S. (2009). Entrepreneurial intention among Malaysian undergraduates. International Journal of Business and Management, 4(10), 54–60. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v4n10p54

- Jiatong, W., Murad, M., Bajun, F., Tufail, M. S., Mirza, F., & Rafiq, M. (2021). Impact of entrepreneurial education, mindset, and creativity on entrepreneurial intention: Mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 724440. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.724440

- Jiatong, W., Murad, M., Li, C., Gill, S. A., & Ashraf, S. F. (2021). Linking cognitive flexibility to entrepreneurial alertness and entrepreneurial intention among medical students with the moderating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy: A second-order moderated mediation model. PLoS One, 16(9), e0256420. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256420

- Kanfer, R. (1990). Motivation theory, industrial, and organizations. In: M. D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (2nd ed., Vol. 1, pp. 75–130). Consulting Psychologist Press.

- Khan, I. U., Hameed, Z., Yu, Y., Islam, T., Sheikh, Z., & Khan, S. U. (2018). Predicting the acceptance of MOOCs in developing country: Application of task-technology fit model, social motivation ans self-determination theory. Telematics and Informatics, 35(4), 964–978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.09.009

- Kour, S., & Sharma, M. (2020). Impact of self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intentions: Role of self-regulation and education. In: H. Chahal, V. Pereira, & J. Jyoti, (Eds.), Sustainable business practices for rural development: The role of intellectual capital (pp. 169–189).

- Krueger, N. F., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5–6), 411–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(98)00033-0

- Kumar, R., & Shukla, S. (2019). Creativity, proactive personality and entrepreneurial intentions: Examining the mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Global Business Review, 23(1), 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150919844395

- Lee, S., Kang, M. J., & Kim, B. K. (2022). Factors influencing entrepreneurial intention: Focusing on individuals’ knowledge exploration and exploitation activities. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 8(3), 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8030165

- Li, C., Ashraf, S. F., Shahzad, F., Bashir, I., Murad, M., Syed, N., & Riaz, M. (2020a). Influence of knowledge management practices on entrepreneurial and organizational performance: A mediated-moderation model. Frontier in Psychology, 11, 577106.

- Liñán, F., & Chen, Y. W. (2009). Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 33(3), 593–617.

- Matthews, H. U. G. H., Taylor, M. A. R. K., Percy-Smith, B., & Limb, M. (2000). The unacceptable flaneur the shopping mall as a teenage hangout. Childhood, 7(3), 279–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568200007003003

- McMullen, J. S., & Shepherd, D. A. (2002). Regulatory focus and entrepreneurial intention: Action bias in the recognition and evaluation of opportunities. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 22(2), 61–72.

- Miao, M. (2015). Individual traits and entrepreneurial intentions: The mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and need for cognition [Unpublished thesis]. Virginia Commonwealth University.

- Michaelis, T. L., Carr, J. C., Scheaf, D. J., & Pollack, J. M. (2020). The frugal entrepreneur: A self-regulatory perspective of resourceful entrepreneurial behavior. Journal of Business Venturing, 35(4), 105969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2019.105969

- Molino, M., Dolce, V., Cortese, C. G., & Ghislieri, C. (2018). Personality and social support as determinants of entrepreneurial intention. Gender differences in Italy. PLoS One, 13(6), e0199924. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0199924

- Mueller, B. A., Wolfe, M. T., & Syed, I. (2017). Passion and grit: An exploration of the pathways leading to venture success. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(3), 260–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2017.02.001

- Murad, M., Li, C., Ashraf, S. F., & Arora, S. (2021). The influence of entrepreneurial passion in the relationship between creativity and entrepreneurial intention. International Journal of Global Business and Competitiveness, 16(1), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-177736/v1

- Muraven, M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychological Bulletin, 126(2), 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.247

- Naseeb, S., Saif, N., Khan, M. S., Khan, I. U., & Afaq, Q. (2019). Impact of performance appraisal politics on work outcome: Multidimensional role of intrinsic motivation and job satisfaction. Journal of Management and Research, 6(1), 1–37.

- Nawaz, T. (2020). Proactive perssonality and emotional intelligence as determinants of entrepreneurial intention with mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and self-regulation among univesity students . A case of Kp public sector universities [An unpublished PhD thesis]. Gomal University.

- Nawaz, T., Rehman, K., Javed, A., & Hamayun, M. (2020). Mediating role of self-regulation between emotional intelligence and entrepreneurial intention: evidence from management students. City University Research Journal, 9(4), 648–664.

- Neneh, B. N. (2020). Entrepreneurial passion and entrepreneurial intention: The role of social support and entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Studies in Higher Education, 47(3), 587–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1770716

- Obschonka, M., Hahn, E., & Bajwa, N. (2018). Personal agency in newly arrived refugees: The role of personality, entrepreneurial cognitions and intentions, and career adaptability. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 105, 173–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.01.003

- Paul, J., & Shrivatava, A. (2016). Do young managers in a developing country have stronger entrepreneurial intentions? Theory and debate. International Business Review, 25(6), 1197–1210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2016.03.003

- Pihie, Z., & Bagheri, A. (2013). Self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention: The mediation effect of self-regulation. Vocations and Learning, 6(3), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-013-9101-9

- Prieto, L. C. (2010). The influence of proactive personality on social entrepreneurial intentions among African American and Hispanic undergraduate students: The moderating role of hope [Unpublished PhD thesis]. Lousiana State University.

- Qazi, Z., Qazi, W., Raza, S. A., & Yousufi, S. Q. (2022). Investigating women’s entrepreneurial intention: The moderating role of family support. ASR: CMU Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 9(1), e2022003.

- Rehman, K., Rehman, Z., Saif, N., Khan, A. S., Nawaz, A., & Rehman, S. (2013). Impacts of job satisfaction on organizational commitment: A theoretical model for academicians in HEI of developing countries like Pakistan. International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting, Finance and Management Sciences, 3(1), 80–89.

- Reynolds, P., Storey, D. J., & Westhead, P. (1994). Cross-national comparisons of the variation in new firm formation rates. Regional Studies, 28(4), 443–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343409412331348386

- Saif, N., Khan, S. U., Shaheen, I., ALotaibi, F. A., Alnfiai, M. M., & Arif, M. (2024). Chat-GPT; validating Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) in education sector via ubiquitous learning mechanism. Computers in Human Behavior, 154, 108097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.108097

- Sarason, I., Sarason, B., & Pierce, G. (1995). Social and personal relationships: Current issues, future direction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 12(4), 613–619. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407595124019

- Shah, T., Saif, N., Shaheen, I., & Ullah, N. (2022). Does librarian job satisfaction mediate the relationship between librarian leadership styles, library culture and employees commitment? Library Philosophy & Practice, 2022, 1–29.

- Shapero, A., & Sokol, L. (1982). The social dimensions of entrepreneurship. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership Historical Research Reference in Entrepreneurship.

- Spurk, D., Volmer, J., Hagmaier, T., & Kauffeld, S. (2013). Why are proactive people more successful in their careers? The role of career adaptability in explaining multiple career success criteria. In: Crossman Elizabeth E. (Ed.), Personality traits: Causes, conceptualizations, and consequences (pp. 27–48).

- Stewart, W. H., & Roth, P. L. (2004). Data-quality affects meta-analytic conclusions: A response to Miner and Raju (2004) concerning entrepreneurial risk propensity. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(1), 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.1.14

- Sun, D. (2020). Entrepreneurship education promotes individual entrepreneurial intention: Does proactive personality work? Open Access Library Journal, 7(10), 1.

- Tewal, E. H. P., & Sholihah, Z. (2020). Self-regulation toward entrepreneurship intention: Mediated by self-efficacy in the digital age. In 5th ASEAN Conference on Psychology, Counselling, and Humanities (ACPCH 2019) (pp. 91–93). Atlantis Press.

- Tumasjan, A., & Braun, R. (2012). In the eye of the beholder: How regulatory focus and self-efficacy interact in influencing opportunity recognition. Journal of Business Venturing, 27(6), 622–636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2011.08.001

- Tyszka, T., Cieślik, J., Domurat, A., & Macko, A. (2011). Motivation, self-efficacy, and risk attitudes among entrepreneurs during transition to a market economy. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 40(2), 124–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2011.01.011

- Uysal, Ş. K., Karadağ, H., Tuncer, B., & Şahin, F. (2022). Locus of control, need for achievement, and entrepreneurial intention: A moderated mediation model. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(2), 100560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100560

- Van de Ven, A. H., & Drazin, R. (1984). The concept of fit in contingency theory. Minnesota University Strategic Management Research Center.

- Wang, J. H., Chang, C. C., Yao, S. N., & Liang, C. (2016). The contribution of self efficacy to the relationship between personality traits and entrepreneurial intention. Higher Education, 72(2), 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9946-y

- Winkler, C., Fust, A., & Jenert, T. (2023). From entrepreneurial experience to expertise: A self-regulated learning perspective. Journal of Small Business Management, 61(4), 2071–2096. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2021.1883041

- Wolfe, M. T., & Patel, P. C. (2016). Grit and self-employment: A multi-country study. Small Business Economics, 47(4), 853–874. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9737-6

- Wu, W., Wang, H., Zheng, C., & Wu, Y. J. (2019). Effect of narcissism, psychopathy, and machiavellianism on entrepreneurial intention-the mediating of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Frontier in Psychology, 10, 360.

- Yamane, T. (1967). Statistics: An Introductory Analysis (2nd ed.). New York: Harper and Row.

- Yaqoob, S. (2020). The Emerging trend Women entrepreneurship in Pakistan. Journal of Arts & Social Sciences, 7(2), 217–230.

- Zareieshamsabadi, F., Nouri, A., & Molavi, H. (2010). The relationship of proactive personalities with entrepreneurship intentions and career success in the personnel of Isfahan University of medical sciences. Health Information Management, 7, 206–215.

- Zeb, N., ASajid, M., & Iqbal, Z. (2019). Impact of individual factors on women entrepreneurial intentions: With mediating role of innovation and interactive effect of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan, 56(2), 89.

- Zhang, L., Fan, W., & Li, M. (2022). Proactive personality and entrepreneurial intention: Social class’ moderating effect among college students. The Career Development Quarterly, 70(4), 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12308

- Zhao, H., Seibert, S. E., & Hills, G. E. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1265–1272. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1265